Résumés

Abstract

The study of Inuit-European contact in Labrador has often divided the coast into north and south, creating a dichotomy that ignores Inuit mobility and emphasizes the arrival and placement of Europeans along the coast. This has caused some researchers to focus too heavily on missionary trade involvement in the north while ignoring merchant activity in the south, and vice versa. This paper seeks to provide further evidence in support of Inuit entrepreneurs as catalysts for the abundance and diversity of European-made trade goods along the coast, rather than the missionaries or merchants themselves. This study presents an analysis of four Inuit dwellings dating from the mid-18th through early 19th centuries, both pre- and post- missionary arrival, from two distinct regions: Nain and Hamilton Inlet. The results show no significant difference in the quantity of trade goods between the two regions, either before or after the arrival of Moravian missionaries. There may have been another factor at work: influential Inuit traders who were a key component of the trade network, who likely rose to entrepreneurial status prior to the arrival of missionaries, and who continued to move items along the coast thereafter. Thus, the increasing European presence did not largely affect the trade network that had emerged by the early 18th century, aside from providing the Inuit population with access to additional resources and more options.

Résumé

Dans l’étude des contacts entre Inuit et Européens au Labrador, la côte a souvent été divisée entre ses parties nord et sud, et cette dichotomie rendait aveugle à la mobilité des Inuit tout en conférant plus d’importance à l’arrivée et à l’implantation des Européens le long de la côte. Cette situation a fait en sorte que certains chercheurs ont trop mis l’accent sur l’implication des missionnaires dans la traite dans le nord tout en ignorant les activités commerciales dans le sud, et inversement. Cet article cherche à fournir de nouvelles données pour appuyer l’idée que ce sont les entrepreneurs inuit qui ont été les catalyseurs, le long de la côte, de l’abondance et de la diversité des marchandises fabriquées en Europe, plutôt que les missionnaires ou les commerçants eux-mêmes. Cet article présente l’analyse de quatre habitations inuit datant du milieu du XVIIIe siècle jusqu’au début du XIXe siècle, soit antérieures et postérieures à l’arrivée des missionnaires, dans deux régions distinctes, Nain et Hamilton Inlet. Les résultats montrent qu’il n’existe aucune différence significative dans la quantité des marchandises de traite entre les deux régions, que ce soit avant ou après l’arrivée des missionnaires moraves. Cela indique qu’il y avait un autre facteur à l’oeuvre, corroborant l’idée que les traiteurs inuit influents ont été un élément clé des réseaux commerciaux car il est probable qu’ils avaient atteint le statut d’entrepreneurs avant l’arrivée des missionnaires et qu’ils ont continué à transporter des marchandises le long de la côte après cela. Par conséquent, le réseau commercial apparu au début du XVIIIe siècle n’a pas souffert, semble-t-il, de l’accroissement de la présence européenne, celle-ci donnant en outre à la population inuit un accès à des ressources supplémentaires et à davantage d’options.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

The nature of Inuit-European contact in Labrador has come under close scrutiny as researchers have sought to gain a better understanding of cultural interactions along the coast. Seminal works by Kaplan (1983), Taylor (1968), and Woollett (2003) laid the groundwork for this important time period in Labrador history, and more recently the research focus has shifted to detailed regional analyses. Until quite recently, the prevailing idea was that the Inuit of Labrador did not venture south of Hamilton Inlet (Fitzhugh 1977). We now know this to be untrue. The Labrador Inuit had permanent settlements that spanned the coast from the 16th century onward (Rankin 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013; Stopp 2002, 2012). Despite strong evidence to suggest that the Labrador Inuit were a highly mobile group (Kleivan 1966; Taylor 1972, 1984), this distinction between north and south remains. Thus, much of the research in Labrador has approached Inuit-European contact from site-specific analyses framed within the north-south dichotomy. While much detail has emerged about the specific households under study, these analyses ignore a key component of Inuit-European contact: Inuit mobility. The challenge now is to make sense of these regional studies along the coast to fully understand the contact experience in light of Inuit mobility and the various European groups the Inuit encountered along the way.

It has been argued that the permanent settlement of the Moravian missionaries in 1771 disrupted the Inuit social system by providing easier access to European-made trade goods and potentially undermined wealth accumulation for the male head of household (Arendt 2011; Taylor 1974). Furthermore, Jurakic (2008: 114) has suggested that Inuit residing away from missionary influence had greater autonomy in their incorporation of European goods than those residing close to mission stations and facing colonial pressures. This paper will explore these ideas by investigating whether there was a noticeable difference in the trade goods and wealth accumulation between Inuit dwellings near Moravian mission stations and those beyond direct Moravian influence. If mobility was as prominent as I believe, there should be little to no difference in assemblages along the coast, as trade would have occurred with both Moravian missionaries and merchants. There should instead be evidence that prominent trading families travelled along the coast and acted as intermediaries for families unable or unwilling to make the long journey. To explore this idea I have selected four sites dating from the early-mid 18th to early 19th centuries along the coast: two near a Moravian mission station; and two in what could be described as prime merchant territory: Hamilton Inlet.

Historical background

While a European presence had been developing along the coast since the 16th century, it was not until the 18th century that Europeans began to permanently settle along the Labrador coast. Much of the European experience in Labrador was dictated by political and social forces outside Labrador. The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 facilitated French occupation of coastal Labrador, this occupation taking the form of land concessions where grant holders were expected to participate in cod and seal fisheries while trading with Aboriginal groups (Hiller 2009; Kaplan 1985; Stopp 2008). Later, in 1763, the Treaty of Paris saw control switch from French to British. This change of power created a more restricted economic regime that banned Newfoundland and New England residents from fishing in Labrador waters and proscribed land-ownership and year-round fishing and trading rights (Stopp 2008: 14). In 1765, Governor Hugh Palliser visited southern Labrador to establish and sign a peace treaty in the hopes of promoting peaceful relations between the British and the Inuit. Later, his restrictive regime relaxed and in 1770 Captain George Cartwright became one of the first of many British merchants to permanently settle the southern coast to engage in cod and seal fisheries, while establishing friendly trade relations with the Aboriginal peoples of Labrador.

By the 18th century, an extensive coastal trade-network had developed where European goods from the south were being traded by Inuit entrepreneurs for baleen, skins, and furs from Inuit in the north (Kaplan 1980, 1985; Kennedy 2009). The restrictive policy established by the British in 1763 included the aim of containing the Inuit in the north, in order to prevent them from interfering with the fishery in the south. At the same time, Moravian missionaries were interested in establishing a mission among the Labrador Inuit. To do so, they agreed to work with the British Government towards limiting Inuit activities in the south, in exchange for land to set up their mission stations (Hiller 1971; Kaplan 1985). In 1771, the Moravians established their first mission station in Nain with the main goal of converting the Inuit population to Christianity, thus becoming the first European group to visit Labrador with specific intentions to alter the Inuit way of life (Kaplan 1985: 64). The Moravians continued their expansion during the 18th century, both to the north and to the south, at Okak (1776) and Hopedale (1782). During the 19th century the Moravians began to experience trade competition with the Hudson’s Bay Company and independent traders willing to venture into the north. This additional European presence was merely one of many reasons prompting the Moravians to establish more mission stations at Hebron (1830), Zoar (1865), Ramah (1871), Makkovik (1896), and Killinek (1904), so that by the late 19th century the entire Labrador coast had an established European presence.

Moravians and trade

With their land grant secured, the Moravian missionaries became the first Europeans to settle north of Hamilton Inlet, and their main concern was the spread of Christianity. Although mission leaders had initially avoided mixing mission work and trade, they quickly realized that engaging in trade was required if they were going to maintain their operations (Hiller 1971; Kleivan 1966; Rollmann 2002, 2011). Through trade the missionaries could form close relationships with the Inuit and finance mission activities, while at the same time shielding their potential converts from the negative influences of southern traders (Hiller 1971; Rollmann 2002; Taylor 1984). Thus the Conference of Moravian Elders advised the missionaries to trade with the Inuit at fair rates and made it clear that they were not to supply any liquor or firearms (Rollmann 2011; Whiteley 1964: 44). A detailed account of the first mission goods used for trade has not been fully analyzed, although Kleivan (1966: 48) suspected that fishhooks, lines, needles, and knives would have been among the first trade goods. Eventually the Moravians were pressured to supply a greater variety of trade items, including firearms and ammunition, in order to compete with non-Moravian traders (Hiller 1971; Rollmann 2011).

A closer examination of trade records from Hopedale was undertaken by Arendt (2011) for her doctoral research. She analyzed both trade lists (goods requested for sale from 1788 to 1804 at the trade store) and Moravian missionaries’ lists (goods imported to the mission from 1782 to 1813). Arendt (2011: 153) makes it clear that the trade lists are not shipping probate lists, but rather requests, which may or may not have been honoured. The results of her analysis show no obvious increase in diversity of trade goods over time; instead, there were great yearly fluctuations, which may correspond to Inuit demand and perhaps even stockpiling at the trade store or development of specific industries like the seal blubber and cod fishery (Arendt 2011). Comparing a sample of these trade lists with a sample from British merchant George Cartwright, we see that both missionaries and merchants attempted to bring in goods that the Inuit would find desirable (Table 1). If missionaries and merchants eventually brought in the same goods for trade, then all areas along the coast would have had access to relatively similar items. When we factor in Inuit mobility, even if something they wanted were unavailable at the mission store, most members of Inuit society knew how to acquire it (either by making the journey themselves or by trading with an entrepreneur who made the trip).

Table 1

Sample of potential trade items from missionaries and merchants

Cartwright adds “I will get patterns made here and give them to you when we meet in town” (in Stopp 2008: 75, Figure 13).

Archaeological evidence

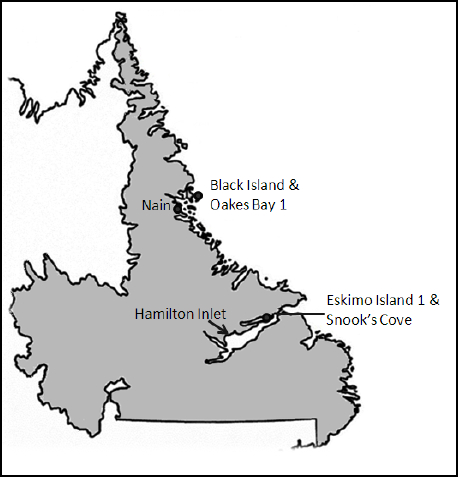

Four dwellings were selected for this study: two from the Nain area—one pre-Moravian arrival and the other post-arrival—and two with parallel date ranges from the Hamilton Inlet region (Figure 1; see Table 2 for site chronology). The dates were determined from previous published accounts and by analysis of diagnostic artifacts that have finite date ranges (e.g., ceramics and marked clay pipes). The sites were selected if they had received substantial archaeological testing, if not full excavation, to determine date of occupation from the artifact assemblage. Another selection criterion was access to the collections, which were either accessible to one of the principal investigators or already in the public domain (museum collections). It was important not only to view the artifacts, but also to examine the catalogue databases and any associated reports or publications to garner a better understanding of the sites themselves. Excavation and cataloguing techniques varied greatly among the four sites, and valuable information on stratigraphy and potential occupation levels was not always available. To standardize the data, I used the entire house assemblages, understanding that some of the artifacts could have been deposited through later occupations or disturbances.

Figure 1

Map of Labrador showing site locations

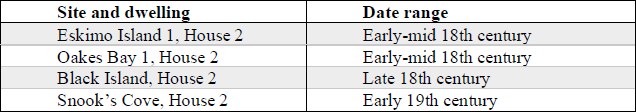

Table 2

Site chronology

Eskimo Island 1 (GaBp-1)

In 1968, William Fitzhugh surveyed Eskimo Island, a small island off the western coast of the larger Henrietta Island in a region known as the Narrows of Hamilton Inlet. Here he discovered three distinct clusters of houses, which he called Eskimo Island 1, 2, and 3. He tested the middens surrounding the dwellings and found typical historic Inuit assemblages. The sites were revisited by Richard Jordan in 1972, 1973, and 1975 (Jordan 1974, 1978; Kaplan 1983: 410). Eskimo Island 1 and 2 are less than 30 m apart, and while considered discrete sites in terms of their Borden numbers, the house numbering for Eskimo Island 2 is presented as a continuation from Eskimo Island 1 (Figure 2). Woollett (2003: 258) attributes this proximity to the island’s topography, i.e., the sites are sheltered from the winds and close to the edge of the fast ice and open water. In addition to prime access to traditional resources, the sites are also well-situated for occupants to engage in direct trade with Europeans. Eskimo Island 1 (GaBp-1) House 2 was selected for this study, as a significant portion of the dwelling had been excavated. On the basis of its artifact assemblage, it can be dated to the 18th century.

Figure 2

Eskimo Island sites

Eskimo Island 1 is in the middle of the group of sites and consists of three large semi-subterranean, semi-rectangular sod houses (Woollett 2003: 258). House 2 is the largest of the houses on the island, and it shares walls with both Houses 1 and 3. Woollett (2003: 259) speculates that Houses 1 and 3 may in fact be older structures that were truncated by House 2’s construction. The floor was paved with stones and covered with a 45-cm-thick deposit rich with cultural material. In the southwest corner of the house, a second layer of floor pavements was revealed, suggesting multiple occupations. Large areas of the floor deposit, and the soils beneath, were saturated with fat, and the stacked rock lampstands had thick charred fat residue (Woollett 2003: 260). Raised sleeping platforms made from compacted peaty soil ran along all three walls, and the presence of wood timbers suggested a wooden-framed roof structure.

Most artifacts from House 2 were European-made, and the diagnostic artifacts were largely of French origin dating to the 18th century. Many of these European-made goods had been used as raw materials for traditional implements: spikes and nails hammered into harpoon endblades, arrowheads, knife blades, and ulu blades (Jordan and Kaplan 1980; Woollett 2003). The assemblage also included nearly 9,000 glass beads, an unusually large quantity that presents some methodological issues for quantitative comparative analysis (see Methodology, below). It is quite likely that the high representation of French artifacts relates to the time of occupation. Thus, House 2 may have been occupied pre-1763.

Oakes Bay 1 (HeCg-08)

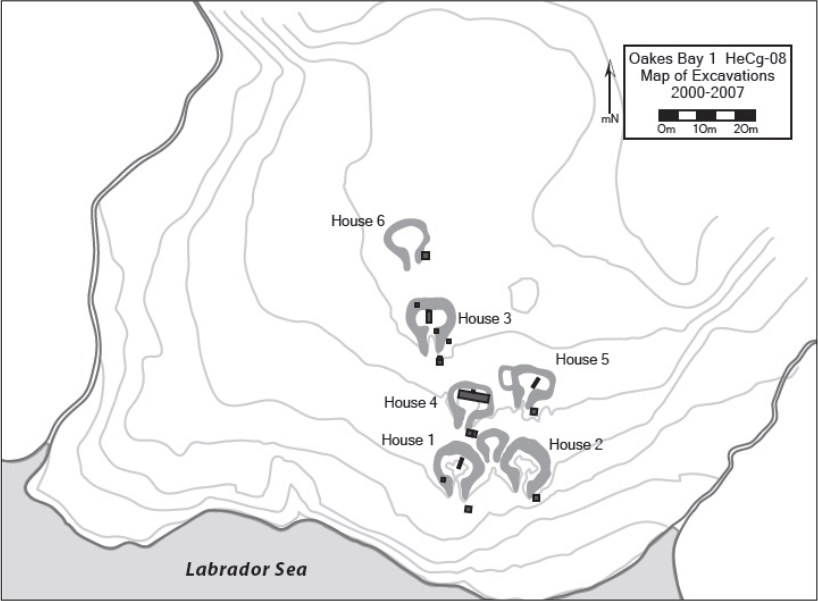

The Oakes Bay 1 site is on Dog Island in the Nain area and consists of six dwellings, three of which are large communal houses. The site was first recorded by J. Garth Taylor in 1966 during his large-scale survey from Nain to Okak and was revisited by crews from the Smithsonian Institution in 1974 and 1980, although no excavation took place during these later surveys (Kaplan 1983). Susan Kaplan and James Woollett returned to Dog Island between 2002 and 2007 to investigate several sites within the region, including Oakes Bay 1. Their main goal was to reconstruct terrestrial and marine landscape histories and land use through a multi-disciplinary framework that combined various archaeological specialties (zooarchaeology, archaeobotany, and archaeoentomology) with paleoecology, geomorphology, and dendrochronology studies (Woollett 2010: 248). They test-excavated the interiors of four houses and six middens, and substantial paleoenvironmental surveys were conducted both on and off the site (Figure 3).

Houses 1, 2, and 3 are the larger rectangular communal house structures, and numerous European-made trade goods were recovered from these dwellings and associated middens to support an 18th century occupation. This time period is further supported in the Nain mission diary for the winter of 1771-1772, when the newly arrived Moravian missionaries recorded occupation at a single dwelling from the site, this being the only year the occupation was mentioned (Woollett 2010). Woollett concludes that one of Houses 1, 2, or 3 would have been the dwelling mentioned in the 1771-1772 census. Houses 4, 5, and 6 are considerably smaller and had minor artifact assemblages that suggested an earlier occupation date, possibly mid-17th century.

Figure 3

Map of Oakes Bay 1 showing excavated areas up to 2007

House 2’s complete excavation was undertaken during the summers of 2010, 2011, and 2012 by Lindsay Swinarton of Université Laval for her doctoral dissertation. Soapstone and whalebone artifacts far outnumber other artifact categories, and iron and copper represent the bulk of the European materials (Swinarton 2012). Although the site was abandoned just as the Moravians arrived in Nain, the long-distance trade network was already in full-force, and the Inuit in that area (and further north) had access to a diverse range of European materials. Based on the relative lack of diagnostic European-made goods, it seems reasonable to suggest that the dwelling was occupied in the earlier part of the 18th century. Perhaps the Inuit at Oakes Bay had little interest in dealing with non-Inuit people or acquiring trade goods, or maybe trade goods were difficult to acquire during the transition from French to British occupation in Labrador in the mid-18th century.

Black Island (HeCi-15)

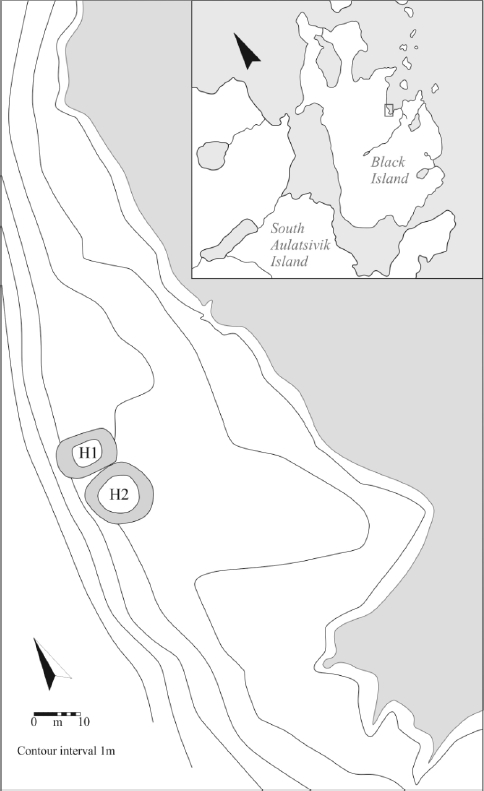

This Black Island site was first located by J. Garth Taylor during his survey from Nain to Okak in the 1960s. There are only two sod dwellings on the island, which was nonetheless occupied by earlier cultural groups and is still in use today. Taylor placed test trenches in both dwellings and described House 2 as having evidence of more traditional Inuit items, but his time was limited and he quickly moved on to continue his large-scale survey. I returned to the site in 2010 for my doctoral research at Memorial University, and I also did test excavations in both dwellings, while avoiding Taylor’s earlier diggings. Based on my 2010 test excavations, and details from Taylor’s 1966 report, House 1 appears to have been modified and used during the 19th century, as its construction is more similar to these later settler-style cabins than a communal or single-family sod dwelling. Although both dwellings are mentioned in the 1776 Beck census, it seems that House 1 was occupied much longer and underwent great structural changes. The two dwellings may have been joined at one point during their occupation. Following House 2’s abandonment, the occupants of House 1 might have borrowed structural materials for the re-construction (Fay 2011; Taylor 1966).

Figure 4

Black Island (HeCi-15)

I returned to the site in 2011 to focus on the excavation of House 2 (Figure 4). It lacked many distinguishing structural features typical of Inuit sod dwellings, for example no evidence of lamp stands, but there was a defined cold trap and entrance tunnel feature. A raised platform of compact sandy soil was present along three walls, although on the north wall the platform was bisected by what appears to be a connection to House 1 or an alternate entrance. The stratigraphy in this area was highly disturbed and more complicated than the rest of the dwelling, supporting the notion that changes were made to House 2, perhaps in order to enhance House 1 at a later date. The artifact assemblage from House 2 is dominated by 18th century European-made items, and suggests that the occupants wholly embraced European trade objects. The lack of a substantial midden suggests that House 2 was occupied for one to two winters, and the documentary record offers no additional information on the potential for House 1’s continued occupation.

Snook’s Cove (GaBp-7)

Snook’s Cove was first examined by Richard Jordan during his excavations in central Labrador from 1972 to 1975. The faunal remains were further studied in the 1990s by James Woollett (1999; 2003; 2007), but the site was not revisited until 2009 by Brian Pritchard for his doctoral dissertation, and Eliza Brandy formed part of the crew, as the faunal material was to be used for her M.A. thesis. Both students came from Memorial University. The site is near present-day Rigolet, and consists of two sod houses, a trading post, and evidence of modern salmon fishing activities. Jordan (1974: 85) originally thought the dwellings were built when Hunt and Henley’s trading post was established in the 1860s, although other traders were in the region before the establishment of the Hunt and Henley post. Jordan tested House 1 and excavated most of House 2, and the results were re-analyzed and presented in Kaplan’s (1983) doctoral dissertation. After studying the artifacts recovered, Kaplan (1983: 428-431) suggested that both houses were contemporaneously occupied during the 19th century.

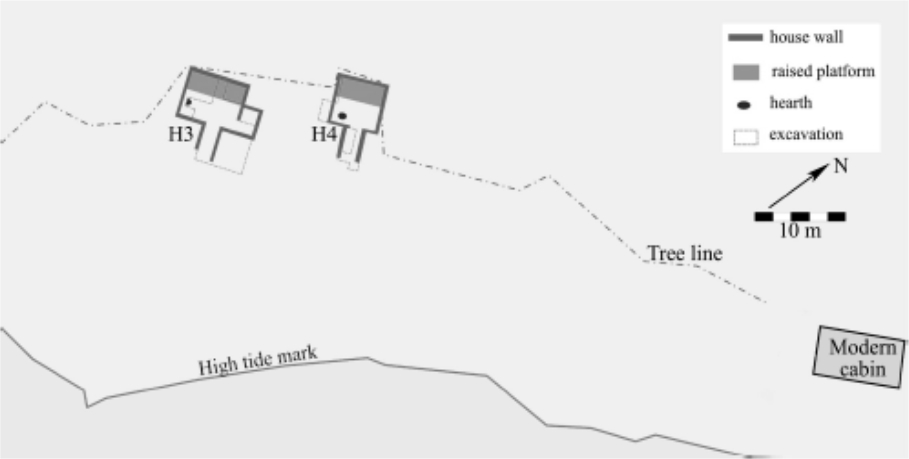

Pritchard’s return to the site in 2009 began with a survey. Two sod house foundations were clearly visible between the shore and the tree line, and evidence of the foundation of the old trading post could be seen underneath a modern cabin foundation (Brandy 2013: 35; Figure 5). Referring to the order of possible structures surveyed on the property, Pritchard called the dwellings House 3 and House 4. It was later realized that these were the same dwellings Jordan had previously investigated and called Houses 1 and 2 (Brandy 2013: 35). To remain consistent with Jordan’s original data and later work (see Kaplan 1983) I will call them Houses 1 and 2, knowing that they correspond to Pritchard’s Houses 3 and 4 respectively.

Due to time constraints House 1 was only partially excavated but House 2 was almost completely excavated (Brandy 2013: 37). Brandy (2013: 39) describes House 2 as having a noticeably sunken interior and slumped walls. This is undoubtedly because Jordan had previously excavated the dwelling save for a small area in its northwest corner (Kaplan 1983: 428). Given that House 2 had been extensively investigated by Jordan, it is likely that the 2009 excavations consisted of disturbed backfill matrix, and the abundance of artifacts recovered could have originated with House 1’s occupation. Fortunately, Houses 1 and 2 appear to have been occupied contemporaneously. Thus, for the purposes of this paper, the assemblage may reflect the late-contact period in the Hamilton Inlet region.

Figure 5

Snook’s Cove

Kaplan’s (1983: 426-431) dissertation describes a number of European-made artifacts from both Houses 1 and 2 that suggest a 19th century occupation. While some of the ceramic types and bead varieties emerged during the late 18th century, these may have been curated over time. The presence of kerosene lamp fragments (which post-date 1860), and a distinct cartridge casing, indicated to Kaplan that these houses were likely a late 19th century occupation, well in line with the arrival of the Hunt and Henley trading post (Kaplan 1983: 431). Pritchard tentatively dated House 2 from 1800-1860, a good 60 years of occupation before the trading post was established (Pritchard and Brandy 2010: 113). After his 2010 season, the dates were further refined, and House 2 appeared to date to the 1790s (Pritchard 2011). Considering both Jordan’s (as interpreted by Kaplan) and Pritchard’s work (as interpreted by Brandy), a 19th century occupation seems more probable, perhaps beginning in the early years of that century and definitely persisting until its end, if not the early 20th century.

Methodology

The Eskimo Island 1 and Jordan’s Snook’s Cove assemblages were examined at The Rooms Provincial Museum in conjunction with the original artifact catalogue sheets, which I transcribed onto an Excel spreadsheet. Unfortunately the catalogue sheets had missing entries and, in a few cases, artifacts were missing as well (e.g., some jars for beads were empty). Being unable to access the original field notes, I relied heavily on published works (Jordan 1974, 1978; Jordan and Kaplan 1980) and unpublished dissertations (Kaplan 1983; Woollett 2003) to make sense of any shorthand present on the catalogue sheets, to supplement my artifact counts, and to piece together the excavation strategy. Pritchard’s Snook’s Cove assemblage, and my Black Island assemblage were examined at Memorial University along with their digital catalogues. I also examined a portion of the collection from Oakes Bay 1 at Université Laval, and Swinarton provided a detailed artifact database for my analysis.

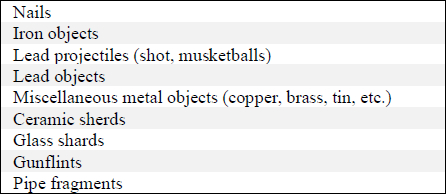

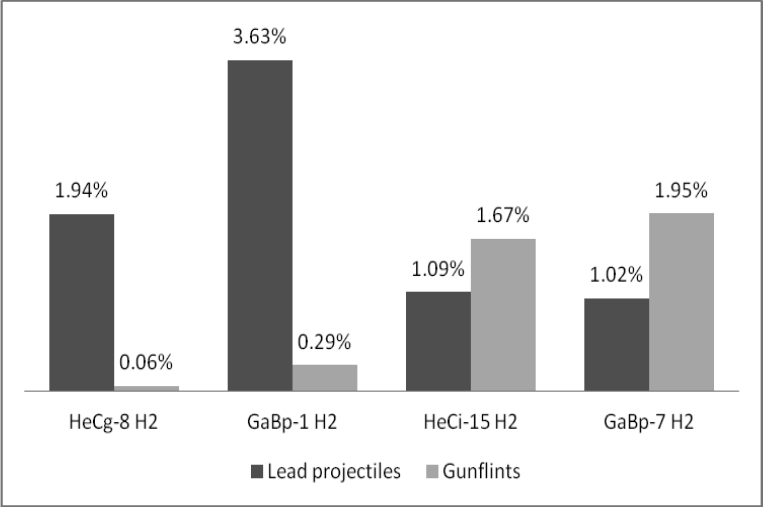

To make the collections comparable, I created a list of common European-made trade goods based on abundant artifacts that tend to preserve well (Table 3). While glass trade beads preserve well and are a great indicator of formalized trade, recovery was inconsistent across all sites due to different field methodologies, and such inconsistency can affect quantitative results and obscure trends and patterns (Pyszczyk 2015). In some cases an abundance of beads may represent a single incident (for example, a container of beads abandoned or spilled) or may result from certain excavation methods (e.g., wet- versus dry-screening, sieve size, etc.) (Burley et al. 1996: 114; Kidd 1987: 89). To see how the amount of glass trade beads relates to these assemblages, I first included the beads in the total artifact assemblage counts (Table 4) and then removed them altogether (Table 5).

Table 3

List of trade good categories

I included unidentifiable/undetermined artifacts, as they make up a large part of the assemblages, in part due to various taphonomic processes that can render objects unrecognizable, and in part due to inexperience with these objects by the cataloguers. Even if their function cannot be determined, their presence is important, as they were obviously something tangible at some point in time and were considered valuable or useful. Thus the iron objects category includes formal tools (e.g., files) along with the scraps that are usually omitted from analysis. I present the raw counts to show how many artifacts were recovered from each house and, more importantly, the relative frequencies to provide better comparisons and information on what percentage of the total artifact assemblage each category represents (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4 presents the data using the entire artifact assemblage, including glass beads but excluding any faunal remains, soil samples, and pre-Inuit lithics. Eskimo Island 1 (GaBp-1) House 2 has a total of 10,015 artifacts, 8,968 of which are glass beads. Their inclusion in the total count diminishes the importance of the other sampled categories, many of which are quite comparable to the other sites included in this study. Table 5 presents the same categories but with the glass beads excluded from the total artifact assemblage, and this adjustment seems to equalize the data across the four sites. Thus the remaining quantitative analysis uses the data from Table 5 to compare the sites selected for this study.

Table 4

Sampled Artifacts from Oakes Bay 1 (HeCg-8), Eskimo Island 1 (GaBp-1), Black Island (HeCi-15), and Snook’s Cove (GaBp-7)

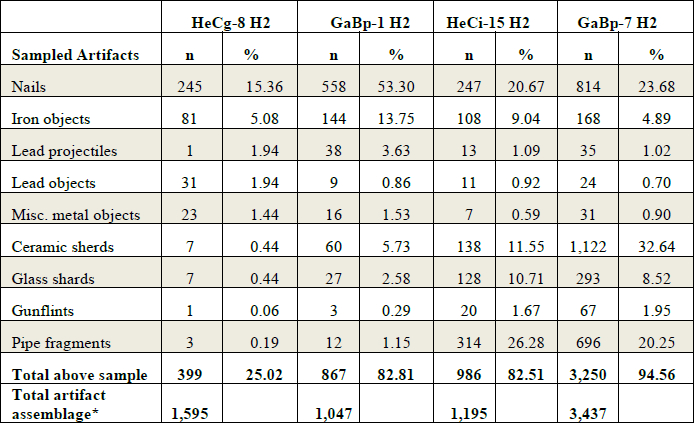

Table 5 shows that these sampled trade good categories make up over 80% of the total artifact assemblage from three of the sites, with HeCg-8 lagging behind considerably. Examining some of the categories more closely, we see no huge discrepancies in abundance between pre- and post-Moravian occupation, nor any patterns suggesting a significant increase in quantity of goods over time. This fits nicely with Arendt’s (2011) observation of fluctuating trade goods over time, perhaps due to changing preferences or demand. Looking at the nails and iron objects categories, we find that GaBp-1 had either more access to these materials or a preference for them (Figure 6), while the figures for lead objects and miscellaneous metals were slightly higher at the two earlier sites of HeCg-8 and GaBp-1 (Figure 7).

Table 5

Sampled artifacts without glass beads

Figure 6

Percentage of nails and iron objects from each site

Figure 7

Percentage of lead objects and miscellaneous metal objects from each site

Gunflints present a very slight and gradual increase over time, which might reflect the increased presence of firearms along the coast (Rollmann 2011), but the same trend is not observed with lead projectiles (Figure 8). The discrepancies with lead shot could be due to differences in artifact recovery or preservation because lead shot tends to be small and, in some soils, becomes quite powdery. Ceramic sherds and glass shards also seem to increase slightly over time (Figure 9). While looking at simple artifact counts as a measure of relative abundance is appealing, this measure ignores one fact: counts are influenced by the degree of fragmentation (Byrd and Owens 1997: 316). For example, Sussman (2000) has proven that one cannot use ceramic sherds for statistical comparison, as one sherd does not equate to one object or vessel, and the same can be said for clay pipe fragments and glass shards. For the purposes of this paper, I assumed that there would be even-breakage patterns in these similar dwellings for things like ceramics, glass, and clay pipes. While these categories are not ideal, their removal from the analysis would greatly reduce the already small sample size.

Despite the small sample size, some statistical tests can be used to determine whether any differences between these sites are significant or not. I used paired t-tests to compare the sites temporally and regionally, and ran the statistics using the percentages presented in Table 5. Using a paired t-test to compare the two earlier sites (t16= -1.57, p= 0.15), I determined that the percentage of European trade goods at HeCg-8 (M= 2.8%, SD= 5.0) does not significantly differ from the same percentage at GaBp-1 (M= 9.2%, SD= 17.0). Running the same test for the two later sites (t16= -0.51, p= 0.62), I also found no significant difference in trade good percentage between HeCi-15 (M= 9.2%, SD= 9.3) and GaBp-7 (M= 10.5%, SD= 12.0). Both pre- and post-Moravian occupation, it seems that Inuit families had equal access to European trade goods in the Hamilton Inlet and Nain areas. Since there was not a consistent European presence in the Nain area pre-Moravian arrival in 1771, Inuit in that region were travelling south for trade goods, or these goods were brought into their region by trade intermediaries.

Figure 8

Percentage of lead projectiles and gunflints from each site

Figure 9

Percentage of ceramic sherds and glass shards from each site

Closer comparison of the two sites in each region still shows no significant difference in percentage of European trade goods. Again using the paired t-test (t16= -2.23, p= 0.056), the percentage of trade goods does not significantly differ between HeCg-8 (M= 2.8%, SD= 5.0) and HeCi-15 (M= 9.2%, SD= 9.3), nor is there significance in a separate t-test (t16= 0.24, p= 0.81) for GaBp-1 (M= 9.2%. SD= 17.0) and GaBp-7 (M= 10.5%, SD= 12.0). Thus both temporal and regional tests support my hypothesis that access to European trade goods did not depend on Moravian arrival or proximity to mission stations. Instead, a much stronger factor seems to have been Inuit mobility and perhaps the mobility of specific “entrepreneurs.”

Inuit entrepreneurs

Prior to Moravian arrival, access to European goods was predominantly through a single entry point: the areas south of Hamilton Inlet, which had numerous European visitors capitalizing on the whales and fish of the Labrador Sea from the 16th century onward. Access to these goods would have required substantial travel by Inuit families through dangerous waters and territory. Influential traders emerged during this early-contact period as they filtered the movement of European goods up the coast for those Inuit unwilling or unable to make the long journey. Richling (1993) referred to these traders as “big men,” and while an uncritical examination of the documentary records—coupled with a bias in interpretation—supported this notion, there is evidence that the role of influential trader was not restricted to men (Fay 2014). Kaplan’s use of the term “entrepreneur” is adopted here, as it better reflects the coastal trade system, where certain individuals possessed entrepreneurial skills that set them apart and created a hierarchy within Inuit society (Fay 2014; Kaplan 1983). Indeed, it has been suggested that some of them would have charged their northern “customers” double the price they paid to merchants in the south (Kaplan 1980: 355; Rollmann 2011).

Wealthy traders are frequently mentioned in the documentary record, although we really have no way of knowing how their trade negotiations with fellow Inuit went. We know that the distribution of European goods was not an egalitarian process, as certain individuals definitely possessed more wealth than others, but it does not follow that access was completely restricted or limited. The convenience of having access to one of these entrepreneurs likely outweighed the cost, as one would require a seaworthy boat and a large family unit to make the long, dangerous journey. Individuals might have been more willing to pay a premium for these goods and thus keep themselves and their families out of harm’s way. These entrepreneurs likely knew what goods their northern customers desired and thus were similar to the merchants or later Moravians who likewise brought whatever items would be needed and wanted.

Conclusion

Travelling great distances for resources was not that unusual for the Labrador Inuit, whose traditional seasonal round took them back and forth between outer islands and inland rivers, but a journey down the coast for European goods would have been a daunting one. The rise of the entrepreneur meant that the goods could still find their way to the far reaches of the north coast long before permanent European settlement. From analysis of four sites, it appears that goods were more or less equally available between regions along the coast and between the periods pre- and post-Moravian arrival. Proximity to Europeans, whether merchants or missionaries, apparently had little effect on the abundance or types of goods acquired along the Labrador coast. The argument that the arrival of Moravian missionaries enhanced access to goods and changed their distribution seems to be false, as there is little difference between the analysed assemblages in this sample. It seems that the Moravians merely provided another avenue for trade goods to enter Inuit communities, and that some members of Inuit society were willing to travel to acquire certain goods that could not be acquired through trade with the missionaries.

A clearer understanding of the contact period in Labrador Inuit history is slowly emerging as the focus of recent scholarship has shifted from site-specific studies to multi-site analyses along the coast. The body of comparative data will grow as more Inuit sites are excavated, and this archaeological material will help fill in the gaps from the documentary record on this important period of Inuit history. Although this study presents a small sample from four sites along the coast, it highlights the importance of Inuit mobility and influential traders. It seems likely that the diversity and abundance of trade goods found along the coast are more closely linked with Inuit entrepreneurs than with the Europeans who brought them to Labrador.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) and the J.R. Smallwood Foundation for Newfoundland and Labrador Studies of Memorial University of Newfoundland, the Provincial Archaeology Office of Newfoundland and Labrador, and through the guidance and encouragement of many, including my supervisor Lisa Rankin, James Woollett, and Lindsay Swinarton. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editor for providing feedback that greatly improved this paper and, subsequently, my dissertation.

Archival source

- MORAVIAN CHURCH, 1788 Goods wanted in Hopedale, St. John’s, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Centre for Newfoundland Studies, microfilm 511, reel 25: 037237-037238.

References

- ARENDT, Beatrix, 2011 Gods, goods and big game: The archaeology of Labrador Inuit choices in an eighteenth- and nineteenth-century mission context, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

- BRANDY, Eliza, 2013 Inuit animal use and shifting identities in 19th century Labrador: The zooarchaeology of Snook’s Cove, M.A. thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s.

- BURLEY, David V., Scott HAMILTON and Knut R. FLADMARK, 1996 Prophecy of the Swan, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press.

- FAY, Amelia, 2011 Excavations on Black Island, Labrador, in Stephen Hull (ed.), Provincial Archaeology Office 2010 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archaeology Office Archaeology Review, 9: 34-36.

- FAY, Amelia, 2014 Big Men, Big Women, or Both? Examining the Coastal Trading System of the 18th Century Labrador Inuit, in John Kennedy (ed.), History and Renewal of Labrador’s Inuit-Métis, St. John’s, Memorial University of Newfoundland, ISER Books: 75-93.

- FITZHUGH, William W., 1977 Indian and Eskimo/Inuit Settlement History in Labrador: An Archaeological View, in Our Footprints are Everywhere: Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in Labrador, Nain, Labrador Inuit Association: 1-41.

- HILLER, James, 1971 Early Patrons of the Labrador Eskimos: The Moravian Mission in Labrador, 1764-1805, in Robert Paine (ed.), Patrons and Brokers in the East Arctic, St. John’s, Memorial University of Newfoundland, ISER, Newfoundland Social and Economic Papers, 2: 74-97.

- HILLER, James, 2009 Eighteenth-Century Labrador: The European Perspective, in Hans Rollmann (ed.), Moravian Beginnings in Labrador: Papers from a Symposium held in Makkovik and Hopedale, St. John’s, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Faculty of Arts Publication, Occasional Publication of Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 2: 37-52.

- JORDAN, Richard H., 1974 Preliminary Report on Archaeological Investigations of the Labrador Eskimo in Hamilton Inlet in 1973, Man in the Northeast, 8: 77-88.

- JORDAN, Richard H., 1978 Archaeological investigations of the Hamilton Inlet Labrador Eskimo: Social and economic responses to European contact, Arctic Anthropology, 15(2): 175-185.

- JORDAN, Richard H. and Susan A. KAPLAN, 1980 An archaeological view of the Inuit/European contact period in central Labrador, Études/Inuit/Studies, 4(1-2): 35-45.

- JURAKIC, Irena, 2008 Up North: European ceramics and tobacco pipes at the nineteenth-century contact period Inuit winter village site of Kongu (IgCv-7), Nachvak Fiord, Northern Labrador, M.A. thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s.

- KAPLAN, Susan A., 1980 Neo-Eskimo occupations of the northern Labrador coast, Arctic, 33(3): 646-666.

- KAPLAN, Susan A., 1983 Economic and social change in Labrador Neo-Eskimo culture, Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr.

- KAPLAN, Susan A., 1985 European Goods and Socio-Economic Change in Early Labrador Inuit Society, in W.W. Fitzhugh (ed.), Cultures in Contact: The European Impact on Native Cultural Institutions in Eastern North America, A.D. 1000-1800, Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press: 45-69.

- KIDD, Robert S., 1987 Archaeological Excavations at the Probable Site of the First Fort Edmonton or Fort Augustus, 1795 to Early 1800s, Edmonton, Provincial Museum of Alberta, Occasional Paper, 3.

- KLEIVAN, Helge, 1966 The Eskimos of Northeast Labrador: A History of Eskimo-White Relations 1771-1955, Oslo, Norsk Polarinstitutt, Norsk Polarinstitutt Skrifter, 139.

- PRITCHARD, Brian, 2011 Snook’s Cove Archaeology Project: Report on Field Season 2, Stephen Hull and Delphina Mercer (eds), Provincial Archaeology Office 2010 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 9: 124-125.

- PRITCHARD, Brian and Eliza BRANDY, 2010 Snook’s Cove Archaeology Project: Report on Field Season 1, Stephen Hull and Delphina Mercer (eds), Provincial Archaeology Office 2009 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archaeology Office Archaeology Review, 8: 112-118.

- PYSZCZYK, Heinz W., 2015 Trends in the Colour of Glass Trade Beads, Western Canada, paper presented at the 47th Canadian Archaeological Association annual meeting, St. John’s, April 29-May 2, 2015.

- RANKIN, Lisa K., 2010 Indian Harbour, Labrador, in Stephen Hull and Delphina Mercer (eds), Provincial Archaeology Office 2009 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archaeology Office Archaeology Review, 8: 119-120.

- RANKIN, Lisa K., 2011 Indian Harbour, Labrador, in Stephen Hull and Delphina Mercer (eds), Provincial Archaeology Office 2010 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archaeology Office Archaeology Review, 9: 126-129.

- RANKIN, Lisa K., 2012 Indian Harbour, Labrador, in Stephen Hull (ed.), Provincial Archaeology Office 2011 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archaeology Office Archaeology Review, 10: 126-129.

- RANKIN, Lisa K., 2013 The Role of the Inuit in European Settlement of Sandwich Bay, Labrador, in P. Pope and S. Lewis-Simpson (eds), Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Transience and Permanence in New Found Lands, New York, Boydell and Brewer: 310-319.

- RICHLING, Barnett, 1993 Labrador’s “Communal House Phase” reconsidered, Arctic Anthropology, 30(1): 6-78.

- ROLLMANN, Hans, 2002 Labrador Through Moravian Eyes: 250 Years of Art, Photographs and Records, St. John’s, Special Celebrations Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador, Inc.

- ROLLMANN, Hans, 2011 “So fond of the pleasure to shoot”: The Sale of Firearms to Inuit on Labrador’s NorthCoast in the Late Eighteenth Century, Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 26(1): 6-24.

- ROLLMANN, Hans, 2013 Hopedale: Inuit Gateway to the South and Moravian Settlement, Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 28(2): 153-192.

- STOPP, Marianne P., 2002 Reconsidering Inuit presence in southern Labrador, Études/Inuit/Studies, 26(2): 71-106.

- STOPP, Marianne P., 2012 The 2011 Field Season at North Island-1 (FeAx-3), in Stephen Hull (ed.), Provincial Archaeology Office 2011 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archaeology Office Archaeology Review, 10: 166-168.

- STOPP, Marianne P. (ed.), 2008 The New Labrador Papers of Captain George Cartwright, Montreal and Kingston, McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- SUSSMAN, Lynne, 2000 Objects vs. Sherds: A Statistical Evaluation, in Karlis Karklins (ed.), Studies in Material Culture Research, Tucson, The Society for Historical Archaeology: 96-103.

- SWINARTON, Lindsay, 2012 Dog Island, Labrador: The 2011 Field Season, Provincial Archaeology Office 2011 Archaeology Review, St. John’s, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archaeology Office Archaeology Review, 10: 169-171.

- TAYLOR, J. Garth, 1966 Field Notes: Site Survey in the Nain-Okak Area, Northern Labrador. Report on Activities Carried Out During the Summer of 1966, submitted to the National Museum of Canada, manuscript on file at the Canadian Museum of History, Gatineau.

- TAYLOR, J. Garth, 1968 An analysis of the size of Eskimo settlements on the coast of Labrador during the early contact period, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto.

- TAYLOR, J. Garth, 1972 Eskimo Answers to an Eighteenth Century Questionnaire, Ethnohistory, 9(2): 135-145.

- TAYLOR, J. Garth, 1974 Labrador Eskimo Settlements of the Early Contact Period, Ottawa, National Museum of Man, Publications in Ethnology, 9.

- TAYLOR, J. Garth, 1984 The Two Worlds of Mikak, part II, The Beaver, 31(4): 18-25.

- WHITELEY, William H., 1964 The Establishment of the Moravian Mission in Labrador and British Policy, 1763-83, The Canadian Historical Review, 45(1): 29-50.

- WOOLLETT, James, 1999 Living in the Narrows: Subsistence Economy and Culture Change in Labrador Inuit Society during the Contact Period, World Archaeology, 30(3): 370-387.

- WOOLLETT, James, 2003 An Historical Ecology of Labrador Inuit Culture Change, Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, New York.

- WOOLLETT, James, 2007 Labrador Inuit Subsistence in the Context of Environmental Change: An Initial Landscape History Perspective, American Anthropologist, 109(1): 69-84.

- WOOLLETT, James, 2010 Oakes Bay 1: A Preliminary Reconstruction of a Labrador Inuit Seal Hunting Economy in the Context of Climate Change, Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography, 110(2): 245-259.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Map of Labrador showing site locations

Figure 2

Eskimo Island sites

Figure 3

Map of Oakes Bay 1 showing excavated areas up to 2007

Figure 4

Black Island (HeCi-15)

Figure 5

Snook’s Cove

Figure 6

Percentage of nails and iron objects from each site

Figure 7

Percentage of lead objects and miscellaneous metal objects from each site

Figure 8

Percentage of lead projectiles and gunflints from each site

Figure 9

Percentage of ceramic sherds and glass shards from each site

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Sample of potential trade items from missionaries and merchants

Table 2

Site chronology

Table 3

List of trade good categories

Table 4

Sampled Artifacts from Oakes Bay 1 (HeCg-8), Eskimo Island 1 (GaBp-1), Black Island (HeCi-15), and Snook’s Cove (GaBp-7)

Table 5

Sampled artifacts without glass beads

10.7202/007646ar

10.7202/007646ar