Résumés

Abstract

This paper examines the role of translation awards in strengthening the literary capital of source languages. Focusing on three Swedish translation awards between 1970 and 2015, and comparing the awarded source languages to 1) the most central and influential literary languages in world literature and 2) Swedish publishing statistics 1970–2015, the aim is to position translation awards as an area of research within Translation Studies, as well as to investigate translation awards as a means of consecrating source languages in the target culture. Furthermore, we ask how these translation awards transfer different forms of symbolic capital back to the awarding institutions. The results from the comparisons show both similarities and differences, indicating that in the Swedish literary field, there are slight variations to the general global hierarchy of languages. The awarding patterns from the three translation awards studied are also in line with the profiles of the different awarding institutions. As could be expected, English is the most awarded language, although its dominance is strikingly small when compared to publishing statistics. This indicates that the literary capital of English is not unlimited; semi-central or even peripheral languages can transfer other sorts of values to the awarding institutions.

Keywords:

- translation awards,

- global literary language hierarchies,

- literary translation,

- literary capital,

- consecration

Résumé

Cet article examine le rôle des prix de traduction littéraire dans le renforcement du capital littéraire des langues sources. Nous y étudions trois prix suédois de traduction littéraire, entre 1970 et 2015, et nous y mettons en parallèle les langues sources des prix décernés dans 1) les langues les plus majoritaires et influentes dans la littérature mondiale et 2) les statistiques de l’édition en Suède entre 1970 et 2015. Les objectifs du présent article sont de démontrer que l’étude des prix de traduction littéraire constitue un domaine de recherche en traductologie, et d’aborder les prix de traduction littéraire comme des moyens de consécration des langues sources dans des cultures cibles. Nous y examinons également les différentes formes de transfert de capital symbolique suivant les institutions qui décernent lesdits prix de traduction. Cette comparaison expose à la fois des similarités et des disparités, ce qui révèle que de légères variations par rapport à la hiérarchie mondiale des langues sont observables dans le monde littéraire suédois. Les schémas d’attribution des trois prix de traduction étudiés sont conformes aux profils des institutions qui les décernent. Sans surprise, l’anglais est la langue la plus récompensée, bien que sa dominance ne s’avère pas écrasante, une fois remise en perspective grâce aux statistiques de l’édition. Ceci nous indique que le capital littéraire de l’anglais n’est pas illimité et que des langues semi-centrales ou même périphériques peuvent transférer des valeurs différentes aux institutions décernant les prix.

Mots-clés :

- prix de traduction,

- hiérarchies mondiales des langues littéraires,

- traduction littéraire,

- capital littéraire,

- consécration

Resumen

Este artículo examina el papel de los premios de traducción literaria en el fortalecimiento del capital literario de los idiomas de partida. Estudiamos tres premios suecos de traducción literaria, entre 1970 y 2015, y comparamos los idiomas de origen de los premios otorgados en 1) los idiomas más dominantes e influyentes en la literatura mundial y 2) las estadísticas de publicación en Suecia entre 1970 y 2015. Los objetivos de este artículo son demostrar que el estudio de los precios de la traducción literaria constituye un área de investigación en traductología, y abordar los premios de traducción literaria como medio de consagración de los idiomas de partida en culturas metas. También examinamos las diferentes formas de transferencia de capital simbólico según las instituciones que otorgan estos precios de traducción. Esta comparación revela similitudes y disparidades, lo que demuestra que se pueden observar ligeras variaciones de la jerarquía general de idiomas en el mundo literario sueco. Los esquemas de asignación para los tres premios de traducción estudiados se ajustan a los perfiles de las instituciones que los otorgan. Como era de esperar, el inglés es el idioma más premiado, aunque su dominio no es abrumador, cuando se pone en perspectiva gracias a las estadísticas de publicación. Esto nos dice que el capital literario del inglés no es ilimitado y que los idiomas semicentrales o incluso periféricos pueden transferir diferentes valores a las instituciones adjudicadoras.

Palabras clave:

- premios de traducción,

- jerarquías mundiales de lenguaje literario,

- traducción literaria,

- capital literario,

- consagración

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Translation awards are on the rise, and new awards are regularly created, such as the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation (established in 2017) or the Man Booker International Award (established in 2005). These awards have nevertheless attracted only limited attention within Translation Studies (see, however, Lindqvist 2006; 2021). In countries like Sweden, with around 10 million residents and a traditionally high portion of translated literature (for example, Lindqvist 2012), translation awards likely serve an important function as a structuring force in the literary translation field.

The aim of this article is twofold. Firstly, it aims to position translation awards as a specific sort of consecration mechanism. While several scholars have emphasized the role of translation awards in the consecration of individual literary translators (for example, Lindqvist 2006; Svahn 2020), a broader perspective on translation awards as a research area for Translation Studies is still missing. Secondly, and more specifically, we aim to investigate translation awards as a means of consecrating source languages in the target culture.

In the present study, the focus is on three translation awards: The Letterstedt Award for Translation, The Swedish Academy Translation Award and The Nine Society Translation Award. To meet the aims stated above, we propose the following research questions:

What languages are consecrated through translation awards in the Swedish target culture in relation to a) internationally prestigious source languages, and b) publishing statistics for translated fiction in Swedish between 1970 and 2015?

How can awards associated with different source languages transfer symbolic capital to the awarding institutions?

The article begins with an outline of our theoretical framework, which concerns the hierarchical system of languages and literary capital, as well as the functions of literary awards. This is followed by a description of our methodological approach. In the subsequent section, we first present some general observations on translation awards in Sweden, after which we present the results according to the three translation awards studied. We thereafter discuss our findings in relation to the three awarding institutions. The literariness of source languages in Sweden and the awarding institutions as consecrators of source languages are then discussed in the fifth section. The article ends with some concluding remarks.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 The hierarchical system of languages and literary capital

Languages and their function within the global literary market have been the cornerstone of the branch of translation sociology concerned with translations as products, commonly referred to as the sociology of translations (see Chesterman 2006). Using a Bourdieusian framework, Casanova (Casanova 2004; Casanova and Jones 2013), and Heilbron (1999) and Sapiro (Sapiro 2010; Heilbron and Sapiro 2016) have contributed to the understanding of the global field of translation.

Heilbron (1999: 430) asserts that “[c]onsidered from a sociological perspective, translations are a function of the social relations between language groups and their transformations over time.” Drawing on De Swaan (1993), he proposes grouping languages into four levels: hyper-central languages, central languages, semi-peripheral languages, and peripheral languages (Heilbron 1999: 434). His calculation to determine this hierarchy of languages is based on UNESCO’s Index Translationum (Heilbron 1999: 432, 434), and a language’s position is determined by its share of the total number of translated books on an international scale (Heilbron 1999: 433). The distribution of translations between these groups is highly uneven, with English being a hyper-central language; in 1980, more than 40% of all translated books worldwide were translated from English (Heilbron 1999: 434). The structuring of the language hierarchy in this global system of translations reflects geopolitical and economic relations. However, languages with a very large number of speakers, such as Chinese and Arabic, are still peripheral in the international translation system. Thus, the language hierarchy on a global scale is not solely defined by economic relations.

Casanova uses the term literariness to designate “literary credit that attaches to a language independently of its strictly linguistic capital” (Casanova 2004: 135). This concept, she argues, “makes it possible to consider the translation of dominated authors as an act of consecration that gives them access to literary visibility and existence. Writers from languages that are not recognized […] as literary are not immediately eligible for consecration.” Source languages are, thus, bearers of literary capital, which determines the possibility for authors to become consecrated on a global scale. Moreover, the literariness of a source language determines the position of the title in the target culture. In a later paper, Casanova and Jones (2013) return to the role of translation and the importance of prestige. They argue that one language—which they refer to as a “dominant language”—tends to be associated with more prestige than other contemporary languages (Casanova and Jones 2013: 379). In the early 19th century, this position was held by the French language; today, this position is held by English. Languages, then, are “‘endowed’ with different levels of capital, and thus unequal standing” (Casanova and Jones 2013: 396). This may be termed literary capital:

In other words, languages may (or may not) benefit from a sort of multiplicative coefficient in the literary market. This coefficient can be called literary because it is determined […] by the literary value of the works produced in this language; it is also, however, determined by the number, which is to say the volume, and implicitly, the age of the literary productions in that same language.

Casanova and Jones 2013: 386

As Casanova and Jones suggest, languages’ literary capital includes their literary tradition as well as the number of speakers they have.

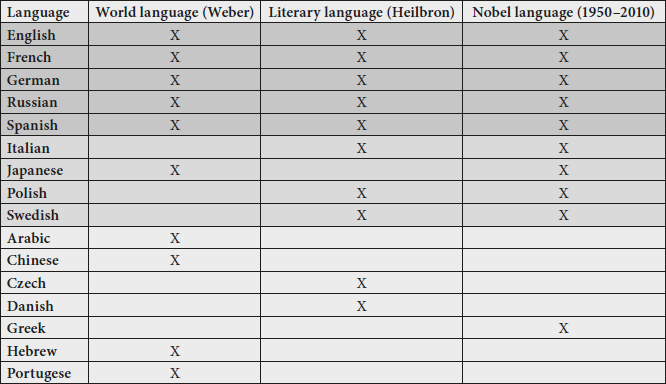

More practical approaches have also been taken to make sense of the present literary hierarchy of languages. The literary sociologist Malin Nauwerck, building on unpublished work by literary sociologist Anna Gunder, presents different approaches to determine a language’s literary significance by comparing the works of Weber (1997) and Heilbron (1999) with the most common languages of the Nobel Prize laureates in literature between 1950 and 2010. Weber (1997) estimates the world’s most influential languages based on the number of primary speakers, the number of secondary speakers, the number and size of the population using the language, the number of significant fields in which the language is used internationally, the economic power of the countries using the language and the socio-literary prestige attached to it. Heilbron (1999), on the other hand, looks specifically at the international flow of book translations based on international translation statistics as described above. The third perspective discussed by Nauwerck relates to the Nobel Prize. Referred to by Casanova (2004: 147) as “the greatest proof of literary consecration, bordering on the definition of literary art itself,” the prize is highly influential in structuring the field of world literature. Gunder has listed the languages with the most Nobel laureates during the years 1950–2010 and combined the list with Heilbron’s and Weber’s findings, establishing a ranking of what she defines as the world’s sixteen most important literary languages. In Nauwerck’s (2018: 28) words, the list “combines a consideration of the languages’ linguistic power (number of speakers) with its literary prestige and standing as source-language [sic] for translations of literature,” which is in line with Casanova’s understanding of the relationship between literariness and the language’s literary tradition and the numbers of speakers. It should be noted that Heilbron’s (1999) classification is based on books, which is naturally a vast category. The list is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

The sixteen most important literary languages (Gunder, replicated in Nauwerck 2018: 29)

Table 1 shows that five languages are noted by Weber and Heilbron as well as the Nobel list, while four languages are indicated by two of these, and seven languages by one of them. Using Heilbron’s (1999) terms for designating a global literary hierarchy, English, French, German, Russian and Spanish can be considered central languages, with English occupying a hyper-central position. Italian, Japanese, Polish, and Swedish would be regarded as semi-peripheral languages, while Arabic, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Greek, Hebrew and Portuguese could be called peripheral languages. However, Heilbron (1999: 434) also states that “all languages with a share of less than one percent of the world market occupy a peripheral position in the international translation system.” The seven languages listed at the bottom of Table 1 obviously have a much more central position than most of the world’s peripheral languages, having made it to Gunder’s “16-list,” but since only a small number of languages are present in the global translation system, the label is still relevant.

This brief overview aims at showing how language hierarchies and literariness—conceived as a language’s literary capital—have been theorized and researched within contemporary sociological-induced literary and Translation Studies. While the scope of these studies is often general and global, we intend to use this framework to study a specific phenomenon in a national setting, namely how languages which are associated with different levels of literariness affect the distribution of translation awards in the target culture of Sweden. More specifically, we ask how the distribution of translation awards reflects the literary capital attached to source languages in Sweden.

Before we proceed to our discussion on the function of literary awards, it is important to discuss yet another factor, namely the arbitrariness attached to prestige: “The ‘prestigious’ language will (in a completely arbitrary way, through the simple fact of its ‘prestige’) exert its power and domination over other languages” (Casanova and Jones 2013: 379). This power is solely based on the perception that there is indeed a difference in prestige between languages (Casanova and Jones 2013: 380). The arbitrary nature of prestige, we argue, fits well into the materialization of another arbitrary consecration mechanism, that of cultural awards, to which we will turn in the next section.

2.2 The functions of literary awards

English (2005) gives a broad picture of the rise of cultural awards in the past hundred years, focusing on global awards, well-known national awards in Western countries, and some more marginal awards in the U.S. Taking his departure from Bourdieu’s concepts of capital and field, he finds that there has been a formidable explosion of cultural awards since the Second World War. Using the word capital “to designate anything that registers as an asset, and can be put profitably to work” (English 2005: 9), English sees cultural awards as a tool for exchanging economic, cultural and journalistic capital within the literary field. He underlines that the different types of capital are intertwined: “Every type of capital everywhere is ‘impure’ because it is at least partly fungible, and every holder of capital is continually putting his or her capital to work in an effort to defend or modify the ratios of that impurity” (English 2005: 10). His thorough overview is highly suggestive and rich in interpretation of the broad phenomenon of cultural awards, although it does not explicitly mention translation awards.

Following English, Määttä (2010) surveys literary awards in Sweden 1786–2009. He focuses only on awards for Swedish original fiction for adults, explicitly excluding translation awards from the study, as well as awards for children’s literature and non-fiction. Looking at factors like the age, prize money and publicity, Määttä lists the 30 most important literary awards in Sweden. He sees a number of motives for creating a literary award, ranging from the honest intent of praising important works, writers or genres and/or helping less commercial writers finance their work, to drawing attention to the awarding institution itself or creating a memorial to a wealthy donator, “a form of long-term effective money laundering that with each passing year transforms a bit more economic capital to cultural capital” (Määttä 2010: 252, our translation; see English 2005: 199, 11, 64). Choosing a recipient is, then, a question of creating and defending the strong position of the award and/or the awarding institution in the cultural awards market. As English (2005: 153) puts it, “[t]heir immediate concerns are neither aesthetic nor commercial but are directed toward maximizing the visibility and reputation of their particular prize among all the prizes in the field” (see also English 2005: 52-54).

Neither English nor Määttä brings translation explicitly into the picture; Määttä focuses entirely on the national Swedish literary field, while English brings up examples of global cultural awards, without discussing translation. On the other hand, Casanova (2004: 133) defines translation per se as “the major prize and weapon in international literary competition.” Based on English’s findings on the important and complex ways that cultural awards transfer symbolic capital, it is fair to assume that national awards for translation, such as those studied in this article, can be an important arena of competition between foreign languages, as well as for the cultural competition between awarding institutions. Thus, an institution which awards a translator working with a specific language not only consecrates that language, but also consecrates the institution itself.

3. Methodology

To investigate the role of translation awards in the consecration process of source languages in the Swedish literary system, we mapped out all Swedish translation awards that are presented in the Swedish Encyclopedia of Translators (2020), an online encyclopedia on the history of translators and translation in Sweden. These awards—eighteen in total—are presented in Table 2 in the Appendix. However, many of them only ran for a short period of time. Furthermore, there are awards on the list that are not exclusively given to translators, but also to writers. To arrive at more comparable material, we have focused on the three translation awards that were continuously given out during the period 1970–2015 and given by a royal academy or cultural institution: The Letterstedt Award, The Swedish Academy Translation Award and The Nine Society Translation Award. The Elsa Thulin Award was also regularly given out during this period, but is excluded from the study, mainly because it is more complicated to connect that award to a specific language; many of its recipients had translated from a number of different languages, and the Elsa Thulin Award is explicitly aimed at a translator’s entire lifetime body of work (Swedish Writers’ Union 2020).

Our main reason for stopping in 2015 was that both of us have been publishing our own literary translations since the early 2010s, meaning that there was a risk of bias. Up until 2015, however, it would have been highly unlikely that either of us would have received a translation award[1]. Having said this, our insider perspective was a contributing factor in forming the research questions and helped us interpret the data on a basic level, although we did try to apply the perspective of researchers rather than practitioners in the analysis.

The next step was to link each award to a source language. This proved to be a greater challenge than we had imagined. Of the three chosen awards, only one is given to a specific work, The Letterstedt Award. It is awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and the awarded works can be either scientific or literary. In that case, it was evident which language was consecrated, but not in all cases. The other two awarding institutions, the Swedish Academy and the Nine Society, award individual translators and rarely provide any motivation, making it impossible to connect the award to a specific work.

To secure the reliability of the study, we could not simply consider every source language with which the awarded translator in question had ever worked as equally consecrated. Some languages were represented to a significantly higher degree than others in these translators’ bibliographies. Furthermore, a vast number of translators specializing in a more peripheral source language had occasionally translated from English as well, or, in some cases, from German or French. This was not surprising, given the hyper-central position of English as a source language in Sweden, as elsewhere. However, our sense was that the awards were often given out for translations from one or two languages in which the translator in question specialized, rather than their bread-and-butter translations from a dominant language. At the same time, we wanted to avoid basing the decision as to which language/s should be considered consecrated with each award on unfounded speculation on our part.

To gain a fair and representative view of which languages are consecrated through the two awards that are not connected to a specific work, we decided to look at the most recent book translation that each recipient had translated at the point of receiving the award. Our pragmatic solution was, thus, to go through the works translated by a specific translator the year before or the same year as the award. In a small number of cases, we had to search further back in time to find a translated work. Non-literary translations were excluded since the awards are explicitly given to literary translators. In some cases, a translator had worked with up to three languages the previous year, but most often, the result was limited to one language per translator. As a consequence of this procedure, translators that appear more than once in the material can be associated with different source languages. The bibliographical source we used was the Swedish National Library Catalogue (LIBRIS). Following the categorization in the Swedish National Library Catalogue, we used the term Serbo-Croatian, even though we were aware that this term is problematic in terms of language politics. (Around 2000, the National Library started to routinely treat these as two different languages.) The term Norwegian includes both written forms of the Norwegian language (Bokmål and Nynorsk). The Icelandic category presumably includes both (Western) Old Norse and Modern Icelandic.

The next step was to compare the awarded languages to statistics for source languages in Swedish translated literature. We found these statistics in the annually published Swedish National Bibliography (Svensk bokförteckning) (1970-2004) for the years 1970–2004. The statistics from the Swedish National Bibliography 2005–2015, however, were not published, but we did obtain them by e-mail from the National Library. Like the Swedish National Library Catalogue, the Swedish National Bibliography is produced by the National Library of Sweden. It shows statistics for source languages of works translated into Swedish in four categories: a) literary non-fiction in translation, b) fiction and poetry in translation, c) children’s literature in translation, plus d) the total number for a, b and c. Table 3 in the Appendix, focusing on category b, presents the figures for the 24 source languages that at least once between 1970 and 2015 is among the ten most translated languages into Swedish.

4. Translation awards in Sweden

4.1 General observations on translation awards in Sweden

A survey of all the eighteen Swedish translation awards is provided in Table 2 in the Appendix. Awards for translation from Swedish into foreign languages are not included. As the table shows, translation awards have existed in Sweden since 1862; however, all but one of these awards was instituted after the Second World War. This is in line with the general tendency of cultural awards described by English (2005: 74) as well as the Swedish literary awards described by Määttä (2010: 248). Five awards were instituted in the early 1970s, and since then many more have been established, although five are no longer active. A new wave of translation awards can be seen in the 2010s when four awards were established. Four of the eighteen prizes award a specific work; the rest of them award the translator’s work in general. The awarding institutions in our material can be divided into six categories, presented in Table 4.

Table 4

Presentation of categories of awarding institutions and translation awards

In some cases, the prize is sponsored by third parties. A large part of the funding for The International Award of the Stockholm House of Culture & City Theatre comes from publishing houses, and funding for Translation of the Year was provided by individual donors until 2019, when a foundation linked to one of the largest publishing houses in Sweden, Natur & Kultur, became a donor and partner. The Swedish Authors’ Fund is here considered a public agency, since it is completely funded by payments from the Public Lending Rights program; however, it is administrated by the Swedish Writers’ Union in collaboration with The Swedish Union of Journalists and The Association of Swedish Illustrators and Graphic Designers.

4.2 Consecration of source languages through three specific translation awards in Sweden

The three awards considered in the present study, shown in Table 5, are the only awards that were given out exclusively to translators during the years 1970–2015. Two of them are awarded by royal academies, and one by the Nine Society, a cultural association that often presents itself as an academy. The Royal Swedish Academy of Science was founded in 1739 under the influence of ideas from the Enlightenment; the Letterstedt Award is the oldest translation award in Sweden, established in 1862 (see Table 2). The Swedish Academy was founded in 1786 by King Gustaf III with the aim of advancing the Swedish language and literature (Svenska Akademien 2021). The translation award was established in 1953. The Nine Society is younger and has a somewhat less conservative profile than the other two. Ever since its founding in 1913, The Nine Society presents itself as a more modern alternative to the Swedish Academy, most strikingly by reserving half of the seats for women and half for men, while the chair’s seat alternates between men and women. After the #metoo scandal, which caused a deep crisis for the Swedish Academy, the Nine Society started to use the slogan “the equal academy” (“den jämställda akademin”) on their website (Samfundet De Nio 2020).

These three independent institutions are all financially stable, culturally prestigious and have long traditions. Their awards are generally given to experienced and already renowned translators taking further steps on the consecration scale by being awarded by these established institutions (see Lindqvist 2006; 2021). In the following, we will present the three chosen translation awards and the source languages they awarded in more detail.

Table 5

Presentation of the translation awards The Letterstedt Award for Translation, The Swedish Academy Translation Award, and The Nine Society Translation Award 1970–2015

The Nine Society Translation Award was not given out every year, but when attributed, it was often to more than one translator (in 2009, as many as seven translators were awarded). The Letterstedt Award was not given out in 1971, 1976 or 2004, and the Swedish Academy Translation Award was shared in 2010. Hence, the number of awards differ. In sum, these three translation awards were given out a total of 152 times to a total of 104 individual translators, associated with 25 source languages, during the period 1970–2015.

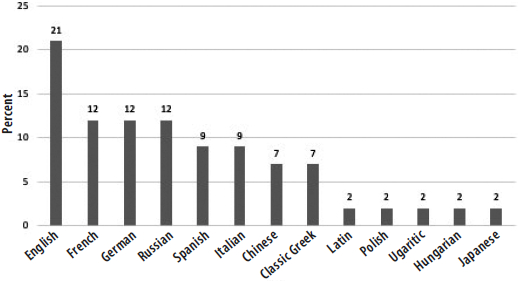

The Letterstedt Award for Translation was awarded 43 times between 1970 and 2015. A total of 41 translators received the award, and 13 languages have been connected with this award. Two translators—Göran Malmqvist and Ulla Roseen—received the award twice during this period. The percentage of Letterstedt Awards given to each language is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Languages awarded through the Letterstedt Award for Translation 1970–2015

As can be seen in the figure, English is the most frequent source language, covering a total of 21% of the awards. The second position is shared between French, German and Russian, all covering 12% of the awards, respectively. Then follows, in descending order, Spanish and Italian (9%, respectively); Chinese and Classical Greek (7%, respectively); and Latin, Polish, Ugaritic, Hungarian and Japanese (2%, respectively). It is noteworthy that the table includes three dead languages (Classical Greek, Latin and Ugaritic); Classical Greek is even associated with 7% of the awards. The two Asian languages on Gunder’s 16-list, Chinese and Japanese, are present here as well. Furthermore, the Letterstedt Translation Award shows a more even distribution between the different languages as compared with the other translation awards in this study.

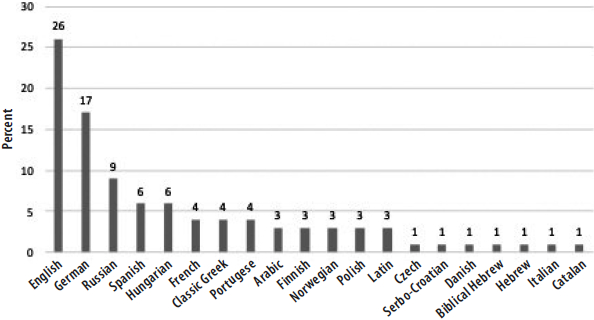

The number of Swedish Academy Translation Awards given between 1970 and 2015 amounts to 47. In 2010, both Gunnar D. Hansson and Ildiko Markó were awarded the prize; being a married couple, they had translated several works from Hungarian. Hence, it is safe to assume that it is a shared prize and that the awarded language is Hungarian, although Hansson has translated from several other languages too. The Swedish Academy Translation Award was awarded to 14 languages, and the proportion of awards given to these languages between 1970 and 2015 is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Languages awarded through the Swedish Academy Translation Award 1970–2015

A total of 25% of the Swedish Academy Translation Awards were given out to translators that had worked with English, followed by German (17%), French (11%), Spanish (9%) and Italian (8%). Portuguese, Hungarian and Norwegian each account for 6%, and Russian for 4%. Danish, Old Norse, Latin, Chinese and Romanian account for 2% each. One distinguishable feature of this award is the relatively high percentage of awards connected to Portuguese and Hungarian. The source languages also include the dead languages Latin and, when scrutinizing the Icelandic category more closely, Old Norse. The only non-European language awarded by the Swedish Academy is Chinese.

In contrast with the other two awards, The Nine Society Award is not awarded annually. It is, however, commonly given to several translators at the same time. This explains the high number of translators being recognized by the Nine Society. In total, the award was announced on 26 occasions during these 46 years, with 59 recipients. Ulrika Wallenström (translating from German) received the award three times during this period; Jan Stolpe (translating from several languages) received it twice. The Nine Society Translation Award displays a greater variety of source languages with a total of 20 different source languages, as presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Languages awarded through the Nine Society Translation Award 1970–2015

Although the variety of source languages is greater than for the other awards, the percentage of awards connected to English is higher: 26%. Again, German holds the second position, with 17% of the awards. After Russian (9%) and Spanish and Hungarian (6%), French shares the sixth position with Classical Greek and Portuguese (4% each), followed by Arabic, Finnish, Norwegian, Polish and Latin (3%); and Czech, Serbo-Croatian, Danish, Biblical Hebrew, Italian, and Catalan (1%).

The first conclusion that can be drawn from the results is that English is by far the most frequently awarded source language: its share ranges from 21% for the Letterstedt Award to 26% for the Nine Society Award. However, although it is by far the most awarded source language, its position in our findings is not as overwhelming as the dominant position it holds (75%) in the statistics on translated literature in Sweden during the same period (see Table 3 in the Appendix). That German is the second most awarded language is perhaps also somewhat surprising, given its relatively lower position in the overall publishing statistics (3.1%). Conversely, the position of French, which has long occupied the second position in the overall publishing statistics (5.6%) and has only been surpassed by Norwegian in recent years (see Table 3), is rather low, especially in the case of the Nine Society Award. The major focus on European languages is also striking; apart from German and French, Spanish, Italian, Russian, Hungarian and Latin were awarded by all three institutions, and Portuguese, Polish, Danish and Norwegian by two of them. Chinese and Japanese are the only Asian languages present in the material and their figures are generally very low, except for the Letterstedt Awards’ connection to Chinese, which amount to 7%. Furthermore, it is notable that languages that are geographically and/or historically close to Swedish, such as Norwegian, Finnish, Icelandic and Dutch, have a rather strong position in the publishing statistics (Table 3), but are rarely or only to a small degree consecrated through translation awards. Norwegian has, since the late 1990s, been the second most translated source language in Sweden (see Table 3), but has only received 0%, 3% and 3%, respectively, of the awards.

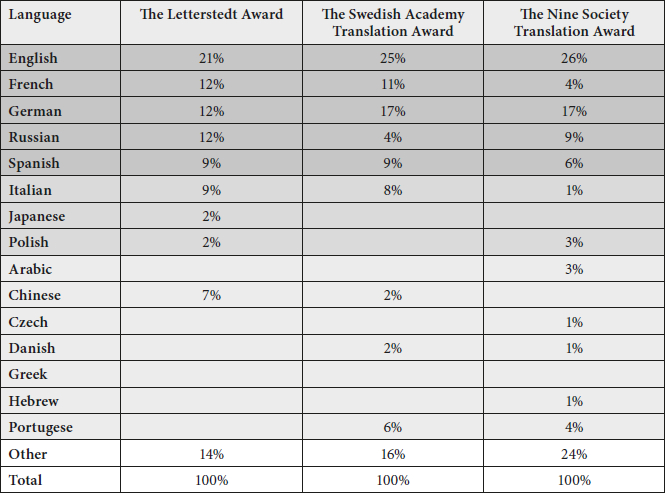

Interestingly, eight languages have been consecrated by all three awards: English, German, French, Russian, Spanish, Italian, Hungarian and Latin. To examine how the different awarding institutions award these languages, the assembled proportion of awards for these languages is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4

The eight languages awarded by all three translation awards

Most languages presented here are either hyper-central (English), central (German, French, Russian and Spanish), or semi-peripheral (Italian), according to Heilbron’s (1999) terminology. The languages that stand out are Hungarian and Latin. Hungarian has been awarded by all three institutions. This is intriguing, since Hungarian is not included on the list of the sixteen most literary languages (see Table 1), and it implies that Hungarian has a higher degree of literariness in the Swedish literary system than in the international translation system. The presence of Latin, on the other hand, shows how a historical literariness attached to a language can linger on into the present. Although the proportion of translated works from Latin into Swedish is only 0.1% during the years 1970–2015; for several centuries, it used to be the dominant language. Furthermore, there are some notable tendencies regarding the different awards. It is interesting to compare the Swedish Academy Translation Award and the Nine Society Award, since their awarding institutions have a similar profile as long-lived keepers of literary prestige. While their shares for English, German, Spanish, and Hungarian are similar or equal, there are some striking differences concerning some of the other languages. For example, 11% of the Swedish Academy’s awards consecrated French, while only 4% of the Nine Society’s awards consecrated French. There is a similar tendency regarding Italian: 8% of the Swedish Academy’s awards are associated with Italian, but only 1% of the awards from the Nine Society. Conversely, 9% of the awards given by the Nine Society were awarded to Russian, while the number for the Swedish Academy is 4%. The Nine Society has, in fact, consecrated Hungarian to a larger degree than they have French or Italian.

5. Discussion

This article set out to explore translation awards and the consecration of source languages in Sweden through two research questions. In the following discussion, we will answer these two questions and relate them to each other.

5.1 The literariness of source languages in Sweden 1970–2015

The first research question concerns the source languages that are consecrated, that is, connected with literariness, in the Swedish literary system. We have approached this question through a comparison of translation award data with 1) literary capital associated with languages on a global scale, and 2) Swedish publishing statistics 1970–2015.

To discuss the findings from our study in relation to the literary capital associated with languages, we have made use of Gunders’s work, replicated in Nauwerck (2018: 27), on the world’s sixteen most literary languages (see Table 1). In our modified version of the table below, Swedish has been excluded from the list, being the target language. We have also added a line entitled “Other” in order to show what percentages of the awards were given to languages outside of the scheme.

Table 6

Percentage of awards to the world’s most important literary languages according to Gunder/Nauwerck

From the results shown in Table 6, it is safe to conclude that the source languages consecrated through translation awards during the studied time period are mainly languages that can be characterized as either hyper-central or central (marked in dark grey); indeed, all three translation awards have awarded these five languages. The percentages for the individual languages within this group, however, vary heavily: from 26% for English (the Nine Society Translation Award) to 4% for Russian (the Swedish Academy Translation Award).

The semi-peripheral languages Italian, Japanese and Polish are marked in a lighter shade of grey. The Letterstedt Award is the only award that has awarded all three semi-peripheral languages, and Italian is the only language within this group that has been awarded by all three awarding institutions. For the Swedish Academy Award, Italian is the only awarded language in the semi-peripheral group, whereas the Nine Society awarded both Italian and Polish. Regarding the peripheral languages, the awards display highly uneven awarding patterns. The Letterstedt Award only awarded one peripheral language during the studied time frame: Chinese, which also received a fairly high percentage (7%). The Swedish Academy, for their part, awarded three of the peripheral languages: Chinese (2%), Danish (2%) and Portuguese (6%). The Nine Society awarded all the peripheral languages apart from Chinese and Greek, and the percentages for these awarded languages is rather low, ranging from 1% for Czech, Danish and Hebrew, to 4% for Portuguese. The “Other” category, which shows the percentage of awards to languages outside of the 16-list, reveals interesting findings. The Nine Society Award has the largest proportion of awards in the “Other” category, 24%. The others give 14% and 16%, respectively, of their awards to languages in the “Other” category. One of the languages in this category is, of course, Hungarian, which, as we have seen, has a relatively large general share of the awards. Although it stands out in relation to the 16-list, Hungarian did make the top 20 list of source languages in the US in 2008 (Sapiro 2010: 429) and is also fairly well-represented in France (Sapiro 2010: 431), which makes its high visibility in Sweden less surprising. That Latin has been awarded—although on a small scale ranging from 1% to 3%—by all three institutions may be indicative of, on the one hand, the historical prestige attached to the language, and, on the other, the institutions’ highbrow profile. It is also interesting to note which languages have not been given any translation awards during this almost fifty-year time period; that is, which languages have not been considered literary enough to yield a translation award. Dutch, for instance, may not be considered an important literary language from a global perspective, but is still a Western European language with comparatively close ties to Sweden. Still, it is not present in our material at all.

To sum up, the translation awards in the present study follow fairly well the established perspective of the literary capital connected to source languages on a global scale. However, there are also apparent differences as to which languages the different institutions choose to award. Publishing statistics of languages translated into Swedish 1970–2015 (Table 3 in the Appendix) show both similarities and differences compared to the languages consecrated by translation awards (Figures 1–4, Table 6). In 1970, 581 works of fiction were published in translation from English into Swedish, which is 75% of a total of 771 works of fiction in translation published that year. In 2015, the corresponding numbers were 754 out of 1,155, that is, 65% of published translations. For most of the years in between, the proportion of works of fiction translated from English remains between 65% and 75%, varying from year to year rather than in a straight line downwards. Compared to the statistics for translation awards, it is obvious that even if English dominates that scene as well, it is much more prevalent in the publishing statistics. In fact, considering that many translators specializing in other languages also translate from English in order to make a living, in which case English was sometimes associated with the award in our study (see above), the dominance of English in translation awards could be expected to be much greater. On the other hand, this can be understood in the light of previous research by Sapiro (2010), which shows that while English is globally dominant at the pole of large-scale circulation, it is under-represented at the aesthetically sensitive pole of small-scale circulation.

If we extend our view of the publishing statistics to the top five languages, we see that the same five languages dominate almost every year: English, German, French, Norwegian and Danish. A small number of other languages hit the top five only occasionally: Russian (8 times), Spanish (5 times) Finnish (twice), Italian and Icelandic (once each). Up until the mid-nineties, French was almost always the second most translated language, followed by German, Danish and Norwegian, in that order. During the 46 years covered by the present study, however, the Scandinavian languages take a stronger position at the expense of German and French, and, during the last 15 years, Norwegian and French alternated on the position of the second and third most translated languages, while German and Danish occupied most often the fourth or fifth position in the statistics. The publishing statistics thus give the picture of English as extremely central, with French, German, Norwegian and Danish as relatively stable source languages with a consistent number of translations each year. With this in mind, it is striking that Danish and Norwegian both have such a weak position when it comes to translation awards, with only 11 prizes in total given to Danish, and 10 to Norwegian. Among the awards, German and French have a strong position; statistically, the chance of receiving an award is a lot higher for translators with these two languages as source languages than for translators with English, Danish or Norwegian as source languages. Their strongest competitors, however, are Russian, Spanish, Italian and Hungarian. Tracing these languages in the publishing statistics, we see that Russian, Spanish and Italian are very often on the top 10 list. So are, however, Finnish, Polish, Icelandic and Dutch, out of which only the latter did not receive a single award and the others only received awards from one institution, respectively. There are also trends in the publishing statistics that do not seem to be reflected in the awards, for instance the growing proportion of translated works from Norwegian and the decreasing number of French translations. In conclusion, translation awards often consecrate languages that have a strong position in publishing statistics, but favor languages like French, German, Russian, Spanish and Hungarian over Scandinavian languages, Polish and Dutch, regarding the total number of translated works for the award committees to choose from.

5.2 Prized languages as consecrators of the awarding institutions

The second research question concerns the impact of the award on the awarding institution. Both English and Määttä emphasize that cultural prizes play an important role in a cultural world where the struggle for prestige and publicity has hardened. According to English (2005: 76), “[w]hat has transformed society since the 1970s is not the rise of a new class per se but the rise of a formidable institutional system of credentialing and consecrating which has increasingly monopolized the production and distribution of symbolic capital.” Since translators are highly invisible in the media, they can be expected to transfer less symbolic capital to the awarding institution than writers receiving a literary award. Määttä (2010: 252) does bring up benevolence as a factor involved in literary awards given to writers, and this factor may be stronger when it comes to translation awards, considering that literary translators in Sweden are often described, by critics, scholars and by their own organizations, as a pitiable group, performing culturally important work while having a hard time earning a living and receiving very little public recognition (see for example, Hjelm-Milczyn 2006; Greve 2013a; 2013b). The attitudes of Swedish translators themselves align with this view (Svahn 2020). It could be argued that their connection to prestigious foreign languages makes them valuable for awarding institutions interested in gathering literary capital, although the need to highlight source languages can, paradoxically, be seen as a way of reinforcing translators’ invisibility. As English (2005: 153) points out, the main concern of the awarding institutions is to maximize the visibility and recognition of their award. In comparison to many other cultural awards that use the status of the recipient’s persona to strengthen the symbolic capital of the awarding institution, it could be argued that translation awards have to take additional advantage of the source languages’ cultural status, which in turn contributes to downplaying the role of the individual translators.

Choosing a recipient for a translation award can, from the Bourdieusian perspective adopted by English and Määttä, be seen as a question of finding a translator whose literary capital is not only strong, but also of the right kind, fitting the demands of the awarding institution. In the crowded market of cultural awards, awarding institutions have to present themselves and/or their awards as different from the others in order to gain publicity and prestige. Awarding translators working with, or works translated from, the five source languages that are the most prominent in the field of literary translations (English, German, French, Norwegian and Danish; see Table 3 in the Appendix) could thus transfer values like authority, trustworthiness and relevance to the awarding institution, while a translator working with semi-peripheral or peripheral languages like Italian, Portuguese or Finnish transfer values like originality, innovation and avant-gardism, making the institution and/or award in question stand out in comparison with other translation awards. Using different strategies, each award can secure their own position. Määttä quotes Peurell, arguing that “[b]efore an author can be a possible recipient of a literary award, s/he must have a certain reputation, which is then further reinforced by the formal recognition that the award implies” (Peurell 1998: 196, our translation). The same could be said about languages. Awarding a language with lower socio-literary prestige is hazardous business. There may, however, be circumstances where such affairs are profitable. Määttä notes that awarding less known authors, preferably literary debutants, can be an important way of gaining publicity, either because the unpredicted choice creates a “scandal”—which, according to Määttä and English, is one of the most important ways of creating publicity for literary awards—or because previous, at the time unknown, recipients of the award in question later achieved further consecration (English 2005: 187-216; Määttä 2010: 255, 266). It is probably harder to create any real scandal by awarding a less prestigious language, but unexpected languages could probably be valued as exciting and notable choices for an award, especially if they have achieved at least some consecration in other ways.

The different awarding institutions in this study clearly have different awarding patterns. Perhaps most striking is the contrast between the awarding patterns of the Swedish Academy and the Nine Society, that is, two institutions with many similarities. The Swedish Academy mainly awarded Western European literary languages with a long history atop the literary scale—the hyper-central and central languages English, German, French, Spanish and Italian being at the top. The Nine Society awarded a total of twenty languages, which allows for a more diversified selection. They demonstrated a higher percentage of awards to languages within the peripheral category of the world’s most literary languages, or even outside it, such as Czech, Serbo-Croatian, Catalan, Arabic and Polish. Furthermore, it is notable that French, the second-largest source language in Sweden during the studied time period, only received 4% of the awards from the Nine Society, while for the other awarding institutions 9–12% of their awards have French as the source language. As discussed previously, the Nine Society has a less conservative profile than the other two academies, and their consecration of less central languages accord well with their self-identified role in the literary establishment. While the Swedish Academy is concerned with maintaining their position as a classical, trustworthy and relevant institution, the relevance and reputation of the Nine Society depends on it holding on to its position as somewhat outside the mainstream of cultural academies, while sharing many traits with them (such as wealth, its own building in the upper-class part of central Stockholm, etc.).

Finally, like the Swedish Academy Translation Award, the Letterstedt Award for Translation is awarded by a Royal Academy founded in the 18th century. The top five languages consecrated by the Letterstedt Award corresponds exactly to the five most central languages according to Nauwerck’s survey (see Table 6 above). Except for Chinese, they only consecrate hyper-central, central and semi-peripheral languages. It is not surprising that a traditional, conservative institution prefers to consecrate—and be consecrated by—literature and languages with a stable, strong position in the field of world literature. However, the Letterstedt Award also stands out for the comparatively even distribution of awards to different languages.

6. Concluding remarks

This paper has demonstrated that translation awards represent a fruitful consecration mechanism to investigate within Translation Studies. Our study has shown that source languages are, to use Casanova and Jones’ words (2013: 396), “endowed” with different levels of literary capital and that their degree of literariness is a relevant factor when specific institutions give awards to specific translators, thereby connecting global hierarchies of languages to specific circumstances in a target culture. We have used translation awards to study literariness in connection with source languages, but we hope that this study has shown that translation awards can contribute to a deeper understanding of literary consecration processes more broadly construed. Another fruitful line of investigation is, for example, to approach translation awards from the point of the view of the translating agents, as in the work of Sela-Sheffy (for example, 2009) and Lindqvist (2006; 2021), where the consecration of individual literary translators takes center stage. In this respect, Lindqvist (2021) has very recently shown that it is possible to construct an autonomous field of Swedish “star” translators translating Spanish Caribbean literature with a point of departure in, among other things, the translation awards they have garnered. These different but closely related studies should make it clear that there are many potential avenues of further research into translation awards.

The results from this study call for a closer examination of English and its hyper-central position. There is a notable difference between publishing statistics and award statistics with regard to the English language. Can this gap be understood as an expression of a partial symbolic inflation? The economic value and dominance of English could make it seem less interesting for award committees investing in symbolic capital. Another possible explanation, as Sapiro (2010) has shown in the context of France and the US, is that the Swedish literary field imports different literatures from different language areas: more commercial books from the Anglo-American and Scandinavian literary fields, and more culturally prestigious books from, most strikingly, the German, French, Russian, Spanish and Hungarian fields. In that case, the system of consecration is self-reinforcing.

Our results show that the awarding patterns from the three translation awards seem to be clearly in line with the awarding institutions’ profiles: more conservative institutions consecrate highly central languages, while more modern or progressive institutions are more likely to award and consecrate semi-peripheral or peripheral languages. Acting on the market of symbolic capital, the awarding institutions are not interested in translations or translators per se, but rather those translations or translators that are culturally prestigious. While the study of translation awards can clearly be linked to the status of individual literary translators, such as in the case of Lindqvist discussed above, its focus on prestige and symbolic capital can paradoxically also reinforce translators’ invisibility.

Comparing the most awarded languages to previous research on the most important literary languages in the global translation system, the results also indicate that the Swedish literary system differs from the global system in certain ways, favoring Hungarian and, to some extent, Chinese. Also notable from the comparison between awarded languages and publishing statistics is the low number of awards associated with geographically close languages like Norwegian, Finnish and Icelandic, which are translated quite often but rarely consecrated through translation awards. Yet, we also recognize the limits of our study, which is based only on three translation awards. A more comprehensive examination would allow us to detect how the literariness of source languages has changed over time. For example, several studies have pointed to the decline of Russian in publishing statistics after the fall of the Soviet Union (for example, Sapiro 2010: 423). How do these kinds of (political, economic, cultural) world events affect the perceived literariness of source languages? Future research in this area should adopt such a perspective, which would complement the results from this study and, ultimately, help us advance our understanding of translation awards in specific target cultures as a reflection of the hierarchy of languages globally.

Parties annexes

Appendix

Table 2

Translation Awards in Sweden

[i] The last time the « Sveriges Författarfonds premium till personer för belöning av litterär förtjänst » was given to a translator was, to our knowledge, in 1986.

[ii] Jacques Outin is a French writer who instigated an award in his own name which awarded Swedish translators of prestigious French literature, approximately every other year. In total, five translators were awarded between 2007 and 2016.

Table 3

Languages that occur on the top ten list of most translated source languages into Swedish between 1970 and 2015. (English, French, Norwegian, German, Danish, Russian, Spanish, Finnish, Italian, Icelandic, Dutch, Portuguese, Polish, Greek (classical and modern), Czech, Chinese, Arabic, Hungarian, Turkish, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian, Latin, Yiddish, and Estonian. The “Other” column includes translations of multilingual works.)

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible through financial support from the Helge Ax:son Johnson Foundation.

Note

-

[1]

It should perhaps be noted that in 2019, one of us did receive an award, if not specifically a translation award, from one of the awarding institutions studied here.

Bibliography

- Casanova, Pascale (2004): The World Republic of Letters. (Translated from French by Malcolm Debevoise) Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press.

- Casanova, Pascale and Jones, Marlon (2013): What is a Dominant Language? Giacomo Leopardi: Theoretician of Linguistic Inequality. New Literary History. 44(3):379-399.

- Chesterman, Andrew (2006): Questions in the Sociology of Translation. In: João FerreiraDuarte, Alexandra AssisRosa and Teresa Sureya, eds. Translation Studies at the Interface of Disciplines. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 9-27.

- De Swaan, Abram (1993): The Emergent World Language System: An Introduction. International Political Science Review. 14(3):219-226.

- English, James D. (2005): The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value. Cambridge/London: Harvard University Press.

- Greve, Victoria (2013a): Gäller att se till att översättarna uppvärderas [We Have to Make Sure that the Value of Translators is Upgraded]. Sveriges radio [Swedish Radio]. March 12, 2013. Consulted on March 25, 2020, http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programmeid=478&artikel=5722876.

- Greve, Victoria (2013b): Förlagen om värdet på en översättning [Publishers on the Value of a Translation]. Sveriges radio [Swedish Radio]. April 12, 2013. Consulted on March 25, 2020, http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programmeid=478&artikel=5723489.

- Heilbron, Johan (1999): Towards a Sociology of Translation. Book Translations as a Cultural World-System. European Journal of Social Theory. 2(4):429-444.

- Heilbron, Johan and Sapiro, Gisèle (2016): Translation: Economic and Sociological Perspectives. In: Victor Ginsburgh and Shlomo Weber, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Economics and Languages. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 373-402.

- Hjelm-Milczyn, Greta (1996): Gud nåde alla fattiga översättare. Glimtar ur svensk skönlitterär översättningshistoria fram till år 1900 [God have Mercy on all Poor Translators. Glimpses from Swedish Literary Translation History until the Year 1900]. Stockholm: Carlsson.

- Lindqvist, Yvonne (2006): Consecration Mechanisms. The Reconstruction of the Swedish Field of High Prestige Literary Translation during the 1980s and 1990s. In: Michaela Wolf, ed. Übersetzen—Translating—Traduire: Towards a “Social Turn”? Vienna/Berlin: Lit Verlag, 61-71.

- Lindqvist, Yvonne (2012): Det globala översättningsfältet och den svenska översättningsmarknaden: Förutsättningar för litterära periferiers möte [The Global Translation Field and the Swedish Translation Market: Conditions for the Meeting of Literary Peripheries]. In: Ulla Carlsson and Jenny Johannisson, eds. Läsarnas marknad, marknadens läsare – en forskningsantologi. Göteborg: Nordicom, 219-231.

- Lindqvist, Yvonne (2021): Det svenska översättningsfältet och det skönlitterära översättarkapitalet. 15 översättares arbete med spanskkaribisk litteratur som exempel [The Swedish Translation Field and the Literary Translator Capital. 15 Translators’ Work with Spanish Caribbean Literature as a Case in Point]. Finsk tidskrift. 2:7-35.

- Määttä, Jerry (2010): Pengar, prestige, publicitet. Litterära priser och utmärkelser i Sverige 1786–2009. [Money, Prestige, Publicity. Literary Awards and Distinctions in Sweden 1786–2009]. Samlaren. Tidskrift för svensk litteraturvetenskaplig forskning. 131:232-329.

- Nauwerck, Malin (2018): A World of Myths. World Literature and Storytelling in Canongate’s Myths Series. Doctoral dissertation. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Peurell, Erik (1998): En författares väg. Jan Fridegård i det litterära fältet [A Writer’s Way. Jan Fridegård in the Literary Field]. Doctoral dissertation. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Samfundet De Nio (2020): Samfundet De Nio | Den jämställda akademin [The Nine Society | The Equal Academy]. Samfundet De Nio [The Nine Society]. Consulted on May 21, 2020, http://samfundetdenio.se.

- Sapiro, Gisèle (2010): Globalization and Cultural Diversity in the Book Market: The Case of Literary Translations in the US and in France. Poetics. 38:419-439.

- Sela-Sheffy, Rakefet (2008): The Translators’ Personae: Marketing Translatorial Images as Pursuit of Capital. Meta. 53(3):609-622.

- Svahn, Elin (2020): The Dynamics of Extratextual Translatorship in Contemporary Sweden. A Mixed Methods Approach. Doctoral dissertation. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Svenska Akademien (2021): The Academy. Svenska Akademien. Consulted on April 14, 2021, https://www.svenskaakademien.se/en/the-academy.

- The Swedish National Library Catalogue Compiled at the Royal Library in Stockholm [Svensk bokförteckning redigerad vid kungl. biblioteket i Stockholm] (1970–2004): Stockholm: Tidningsaktiebolaget Svensk bokhandel.

- Swedish National Library Catalogue (Libris) (2020): LIBRIS. National Library of Sweden. Consulted on April 9, 2020, https://libris.kb.se.

- Swedish Encyclopedia Of Translators (Svenskt Översättarlexikon) (2020): Svenskt översättarlexikon [Swedish Encyclopedia of Translators]. Litteraturbanken [The Swedish Literature Bank]. Consulted on April 9, 2020, https://litteraturbanken.se/översättarlexikon.

- Swedish Writers’ Union (2020): Elsa Thulin-priset [Elsa Thulin award]. Sveriges Författarförbund. Consulted on June 5, 2020, https://forfattarforbundet.se/om-oss/sektioner/oversattarsektionen/elsa-thulin-priset/.

- Weber, George (1997): The World’s 10 Most Influential Languages. Language Today. 1(3):22-28.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Languages awarded through the Letterstedt Award for Translation 1970–2015

Figure 2

Languages awarded through the Swedish Academy Translation Award 1970–2015

Figure 3

Languages awarded through the Nine Society Translation Award 1970–2015

Figure 4

The eight languages awarded by all three translation awards

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

The sixteen most important literary languages (Gunder, replicated in Nauwerck 2018: 29)

Table 4

Presentation of categories of awarding institutions and translation awards

Table 5

Presentation of the translation awards The Letterstedt Award for Translation, The Swedish Academy Translation Award, and The Nine Society Translation Award 1970–2015

Table 6

Percentage of awards to the world’s most important literary languages according to Gunder/Nauwerck

Table 2

Translation Awards in Sweden

[i] The last time the « Sveriges Författarfonds premium till personer för belöning av litterär förtjänst » was given to a translator was, to our knowledge, in 1986.

[ii] Jacques Outin is a French writer who instigated an award in his own name which awarded Swedish translators of prestigious French literature, approximately every other year. In total, five translators were awarded between 2007 and 2016.

Table 3

Languages that occur on the top ten list of most translated source languages into Swedish between 1970 and 2015. (English, French, Norwegian, German, Danish, Russian, Spanish, Finnish, Italian, Icelandic, Dutch, Portuguese, Polish, Greek (classical and modern), Czech, Chinese, Arabic, Hungarian, Turkish, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian, Latin, Yiddish, and Estonian. The “Other” column includes translations of multilingual works.)

10.7202/019242ar

10.7202/019242ar