Résumés

Abstract

In the 1960s and 70s, a new interest in the prehistory of fantastic literature found its paperback and digest magazine form in projects of textual recovery like the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, Forgotten Fantasy Magazine, and the Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy series. This article describes how the material form of these books speaks to their intended audience of fans of science fiction and fantasy, and compares the processes of editing and disseminating Victorian fantasy to the social practices of SF fandom. In the colourful covers and facsimile reprints of these reprints the exigencies of cheap dissemination and the desire to make the works accessible to a modern audience result in eclectic, modern paratexts under the guidance of editors such as Doug Menville, Robert Reginald, and Lin Carter, themselves active readers who form, collect, and print their own personalized bodies of essential fantasy literature, blurring the arbitrary boundaries between author, reader, editor, publisher, and fan.

Résumé

Dans les années 1960 et 1970, on commence à redécouvrir des oeuvres antérieures appartenant au genre du fantasy et à les diffuser par l’entremise de collections telles que Ballantine Adult Fantasy et Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy, et de Forgotten Fantasy Magazine. L’article s’attarde à l’objet livre lui-même et à la mise en marché de cette littérature auprès d’un lectorat cible, à savoir les amateurs de fantasy et de science-fiction. On souhaite rendre celle-ci accessible, esthétiquement et économiquement, à un auditoire contemporain : la facture paratextuelle se veut donc résolument moderne et éclectique, sous la direction des Doug Menville, Robert Reginald et Lin Carter et autres. Parce qu’eux-mêmes sont à la fois d’avides lecteurs, anthologistes et éditeurs de fantasy, ils incarnent un exemple probant de l’impossibilité, parfois, de distinguer la posture d’auteur de celle de lecteur, de directeur de publication, d’éditeur ou d’amateur.

Corps de l’article

By the early 1970s, in the wake of J. R. R. Tolkien’s massive success on college campuses and communes, fantastic literature was an acknowledged part of the publishing landscape. And yet, like science fiction, fantasy was still a literary genre in search of respect. It is at least in part in response to this self-consciousness about the legitimacy of fantastic literature that publishers and editors of speculative fiction set about selecting representative nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century writers such as William Morris, James Branch Cabell, and Lord Dunsany for reprinting in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, in the digest Forgotten Fantasy Magazine, and in the Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy Library series that followed it. The editors, in their introductions and in their personal reminiscences, describe these recovery projects as a labour of love, the work of enthusiasts. Promising little more than a good read and declaring always that their choices were largely a matter of personal taste, the editors of the various series nonetheless set about establishing between them a corpus of the essential works of fantastic literature before Tolkien, with its own lineal descents and clans, down to the present day. The reprint series represented something more than an attempt to create a canon of fantastic literature: they aimed to imbue speculative fiction (SF) with an atmosphere of longevity and thus legitimacy, but still wanted to reassure their readers that archaists like Morris might be more comfortingly familiar than might appear on first glance. They also promised a kind of backward-looking novelty, offering wider access to works that had hitherto been fairly rare. And yet in spite of the inclusion of impenetrable philosophical fantasies like E. R. Eddison’s Zimiamvian Trilogy, there is little of the highbrow about these series; their editors maintain a breezy, enthusiastic tone in the introductions, and the disjunction between the colourful covers and the occasionally antique diction and remote style of these nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century reprints is one of their most striking features. For in spite of their perilously dated choice of texts to sell to the novelty-seeking SF community, the fantasy reprint editors in the 1970s were motivated not only by the profit motive, the completism of the bibliographer, and the enthusiasm of the book collector, but by the same impulse that motivated much of SF’s fanbase at the time: a desire to access and to connect with communities of like-minded readers. In the case of the fantasy reprint series, this kind of connectivity was to be harnessed in aid of textual recovery; it thus marks a moment where some SF fans briefly abandoned their search for novelty in order to look backward and to create an historical canon of fantastic literature, in the process becoming editors and small-scale publishers themselves.

It was the paperback form above all that enabled the publication of SF reprint series by and for such small groups of enthusiasts, and which enabled those enthusiasts in turn to become among the most dedicated of book-buyers and -collectors. Materially, these reprint series were almost universally paperbacks (the Arno reprint series of early SF during the same period was in hardcover, leading to some complaints about the price). Photo-offset printing allowed the editors to engage in a minimum of textual decision-making and proofreading (and, indeed, to maintain a kind of fidelity to earlier, more old-fashioned typographical states of the text); in the case of the magazine, photo-offset printing also meant that public domain decorations from the Art Nouveau and earlier periods could be used freely. Without the paperback and digest magazine form to keep the cost down, small-time publishers like Newcastle’s Saunders brothers could not have made the enterprise viable.

Such small-scale publishing was nothing new to the independent SF community; SF fans are notoriously among the most active, self-aware, creative, and critical readerships, and have been so since long before the Internet. As rich brown and Bernadette Bosky have described, since the 1940s amateur press associations (“apas”) had provided a forum for SF fans to share their thoughts on writers, books, the genre, and the scene in general. Usually this would be accomplished by each participant mailing his or her work to a single editor, who would then disseminate all the responses back to the group (Bosky 181), but there were various ways for amateurs to contribute to the scene. Between this kind of reflective letter-writing and the small publishing companies described by Robert Weinberg in his article on “The Fan Presses” was a whole gamut of what rich brown calls “CRAP”—the “Carbon-Reproduced Amateur Press” (the SF fan’s love of technical-sounding acronyms and straight-faced silliness shines through here). Maintaining running feedback and commentary on each other’s critical and creative work was an integral part of the apa process, and of CRAP in general for SF readers. This was a highly participatory model of readership that reinforced the fan’s position in the writer/reader/publisher cycle, building loyalty and encouraging him or her to build an encyclopaedic body of knowledge surrounding SF authors, themes, titles, and texts. It is not surprising, therefore, that SF began to get its first bibliographers, editors, and reprint series in the age of the fan presses.

As an early reader of this article rightly remarked, “Fluidity among author and reader is not unique to fantastic literature”, and as Janice Radway argues in her influential study Reading the Romance, “many romance writers were romance readers before they set pen to paper” (69). Although plenty of SF authors began their careers as avid readers, commentators, and fans (and indeed, more than one fantasy trilogy has had its origin in the still more fluid and collaborative fan-environment of the roleplaying game), the textual recovery projects of the 1970s further illustrate a startling fluidity among author, reader and editor. Lin Carter and Robert Reginald, for instance, have acted in all three roles. What is significant about the recovery of Victorian fantasy was that it marked a moment where the fan could become, not only a reader or author of SF, but an archivist-explorer, creating genealogies for his/her favourite genre, digging up old literary treasures to display, and most important of all exploiting the cheapness of new printing technologies to disseminate those texts. This is a whole different category of nerd.

The choices made by editors such Lin Carter (the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series) and Robert Reginald and Doug Menville (Forgotten Fantasy Magazine and the Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy paperback series) helped to shape the canon of classic fantasy, and the tactics these editors adopted were in many ways common to the reprint series of the earliest days of mass print culture. In his article “From Aldine to Everyman,” Richard Altick identifies the “series concept” as an essential method of gaining readerly loyalty for publishers of reprint series in the late nineteenth century:

The practices adopted in producing and marketing the cheap classic series often throw interesting light upon contemporary publishing theory and bookbuying habits. The “library” idea -- selling a frequently miscellaneous list of books under a generic title—reflects three familiar merchandising premises, now known as “package psychology,” “brand name psychology,” and “snob appeal” respectively. The first assumes that when a buyer owns a few volumes in a given series (the “package”), he is likely to want to acquire the rest. The second assumes that a reader who is already pleased with one or two books belonging to such-and-such a “library” will regard the name of that series as a guarantee of excellence. The third depends on the connotation of “library,” a term which in the nineteenth century was frequently preceded by “gentleman’s.” Possession of a shelf or two of books prominently labeled “library” gave a man a pleasant feeling of added status, however humble his actual circumstances.

11-12

The relevance of the first two items on Altick’s list requires little discussion: the series is still a staple even of new fantasy publishing precisely because its readers are collectors and completists; the recent rumblings of discontent among George R. R. Martin’s fans may have as much to do with the physical incompleteness of the sequence of Song of Fire and Ice books on their bookshelves as they do with the fans’ natural desire to read the rest of the epic. The third item on Altick’s list, “snob appeal,” is hardest to apply and quantify. In a way, the appeal to the Victorian past is inherently snobbish and yet, as will be seen, the paratexts of the books—sexy covers, boyishly enthusiastic introductions—bespeak a relatively light-hearted approach to publishing and advertising, both on the part of the well-funded Ballantine series and of the much smaller Newcastle Publishing Company. It is evident from letters by the passionate readers of Forgotten Fantasy Magazine, and from the reminiscences of the editors themselves, that the project of reprinting Victorian fantasy in the 1970s was far more of a grass-roots phenomenon than either the mass reprint series of the nineteenth century or the concerted attempt by Ace in the 1960s and -80s to market SF as a highbrow product. Partly this was because “forgotten fantasy” was a specialized taste; but the project of textual recovery was distinguished in particular by the do-it-yourself spirit of the era and the independent creativity of the fan community itself.

By way of contrast, Sarah Brouillette has described how, in 1967-71 and later in the early 1980s, Ace Books launched the Ace Science Fiction Special series in order to reach a more highbrow reading audience than had previously existed for SF. The outward presentation and physical form of such paperbacks was a crucial part of their marketing strategy. In common with the romance publishers described by Radway, though with a very different target market, Ace had spent time and money developing a sophisticated sense of how the external features of its books could be made to appeal to prospective readers:

Marketing what Carr hoped to present as a less popular, more artistically viable sort of fiction could only mean choosing an alternate set of paratexts—paratexts that were simultaneously deployed by many commercial publishers seeking higher sales to those consumers who did not tend to purchase books marked by their status as mass culture.

200

Although this is not precisely the same “snob appeal” that Altick identifies, it shares with Altick’s article a strong sense of the way in which the physical appearance of the book is intended to shape assumptions about the cultural legitimacy of the text. It also marks a moment when SF began to recognize that it could claim to carry some intellectual weight.

This quest for literary recognition informed the recovery of nineteenth-century fantastic literature as well, but the reprint series faced a slightly different set of difficulties in positioning the works between their covers. The blurbs on the back suggest that many of these works were being re-introduced into a marketplace that was at least partly aware of their literary and historical worth. However, this was not the case with all the authors in the canon, many of whom had faded into relative obscurity in the intervening decades. Since part of the point of the project was also to create a beachhead for readers of dated Victorian fantasy among the mercurial, novelty-seeking hordes of SF readers in the early 1970s, something had to make up for the lack of brand recognition commanded at the time by writers such as Edith Nesbit, George MacDonald, and even Arthur Machen; likewise, the loyalty inspired by the Ballantine Adult Fantasy and Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy Library imprints could only go so far. Without many big names to draw upon, publishers needed to have some immediate way of capturing their readers’ imaginations. Word of mouth was one method (and indeed it was the preferred way of reaching SF fans), but it would have been slow to catch on in spite of the rapid circulation of information among SF’s various fanbases. Introductions by known or unknown editors were easy to write and to include (and were useful in claiming the reprints’ literary value), but could only go so far in convincing buyers. Lavish advertising campaigns were of course out of the question, and it was a niche market anyway.

So, in true pulp fashion, they went for an eye-catching display on the newsstand rack. The covers of science fiction and fantasy digests and comics, eye-catching glossy wrappers binding industrial-stapled bundles of pages, are perhaps their defining feature, designed to capture the attention of the potential buyer browsing the newsstand. Entire websites and a lot of bandwidth have been devoted to preserving these memorable covers in digital form (in the very thorough bibliographies and image banks of Galactic Central, for instance, or in the more anarchic, tongue-in-cheek archives of superdickery.com). In reading science fiction written in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, there is a sense of a circular model of influence, as writers seem to have been composing tales to fit the current fashion in cover matter even more than the artists were aiming to illustrate the actual contents of the magazine.

It must have been difficult to work up an accurate and appealing cover for reprinted Victorian fantasy. For one thing, it was a matter of clashing historiographies: the future as it had been envisioned in 1890 was not the future as it was envisioned in 1950 or in 1970. The same was true for the distant past, or for alternative universes. Anachronism and textual infidelity were inevitable. Although most of the covers of the Newcastle and Ballantine books were commissioned specifically for the works they mediate, in every case they serve to reposition the text for a new generation of readers. In doing so, as will be evident, they were not always accurate in previewing the book’s actual contents. If, as Nicole Mathews remarks in her introduction to Judging a Book by its Cover, the covers of books mark the first point of mediation between the text and the intended reader of a book, then the sometimes-startling disjunction between the covers, introductions, and contents of these books and magazines suggests that the experiences of prospective readers were variously imagined by the publishers, editors, and illustrators of the Ballantine and Newcastle reprints. The diversity of reader responses to the magazine’s cover has a lot in common with the diversity of their responses to the magazine’s textual and paratextual contents. That is, although the cover is a point of conflict as well as a point of mediation, the disjunction between cover and content is not as dismaying as it might seem, particularly because the SF community, as I describe it above, was diverse and liable to cheerful squabbling anyway. The important thing was to capture the reader’s imagination. Those readers who knew the writers in question would be drawn to the names; those who were not already dimly aware of pre-Tolkien fantasy were expected to be drawn in by the paratexts and then to stay for the text itself.

The most recognizable of the fantasy reprint series, the one still most commonly met with in used bookstores, and the one with the largest publishing muscle behind it, was the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series. Under the editorship of Lin Carter, the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series published 65 books all told, from May 1969 to April 1974, selling for 95 cents or, later, a dollar and a quarter (earlier editions of works by Tolkien and E. R. Eddison are not part of the series proper and are thus not counted among this number, but they are relevant and would push the total a bit higher). Most of the works that Ballantine published under the Adult Fantasy imprint were by writers from the Edwardian or interwar period, such as Fletcher Pratt, James Branch Cabell, Hope Mirrlees, and others. A couple looked back ambitiously to the late eighteenth century (Beckford’s Vathek) and even, in what was probably a case of overreach, to Renaissance romance (a new prose translation of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, of which they only published one of a promised two volumes). But the backbone of the series was its resurrection of fantastic literature from the mid- and late-Victorian period, including works by William Morris, George MacDonald, H. Rider Haggard, Arthur Machen, and Lord Dunsany. One representative cover from the series is that of Rider Haggard and Andrew Lang’s co-written classical Egyptian Odyssean romance The World’s Desire. It combines Haggard’s femme fatale with Arabian architecture, hieroglyphic mysticism, and psychedelic flames to fine effect, and is not very Victorian, but it captures the free artistic spirit of 1972 rather well. The typography of the title is modern SF with a hint of Art Deco styling[2]. Incidentally, we can chart at least one specific reader for this particular edition: Northrop Frye’s copy is at the Victoria College library in the Frye collection, diligently annotated. Frye owned a number of Ballantine Adult Fantasy books, by Morris and others. Frye thus represents the collector who was drawn to the paperback reprint series’ promise of greater access to known writers.

The enthusiastic Ballantine introductions of Lin Carter portray fantasy literature as having an aristocratic though inbred history of criticism and readership; in each introduction, the editor drops names that are (or that become with repetition) recognizable landmarks of the genre—George MacDonald, William Morris, Lord Dunsany—reinforcing with each repetition the work’s place in the canon of fantastic literature. But in the introductions, Carter makes it clear that the project of textual recovery is for him a matter of individual personal liking and taste. In his introduction to Arthur Machen’s sophisticated macabre exercise The Three Impostors (1890, reprinted by Ballantine in 1972), Carter frankly acknowledges his fannish love for the story:

Like everyone else who loves the kingdom of books, and whose life has been devoted to adventuring within the all-but-limitless borders of that kingdom, I have found my way to certain books which seem to have been written for my pleasure alone.

vii

Carter goes on to include a list of his favourite books, Machen’s among them. This disarming, breezy, self-indulgent tone is almost universal among the fantasy reprint series editors; it bespeaks equally the pride of the accomplished library explorer, the exclusiveness of the scenester, and the self-consciousness of the geek. That is, Carter’s introduction is quite open about the fact that even the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, with its aesthetically accomplished covers and its assertion of typographical control over the texts of the novels (a control that the facsimile reprints of Newcastle could or would not assume), was still an exercise in what Joe Sanders calls “fan-publishing.” This was both a strength and a weakness of the enterprise, since it might seem to make for an atmosphere of dilettantism; and yet without that amateur enthusiasm few of these works would have been resurrected at all. Despite the professional-looking design and the dedication of Carter and the publishers Betty and Ian Ballantine, sales of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series were, according to the fan-bibliographer “The Haunted Bibliophile,” “mediocre.”

While the Ballantine series marks the beginning of the recovery of fantasy literature in relatively respectable paperback form, there had been previous magazine attempts to quarry the vast quantity of obscure and out-of-print fantastic literature from the previous century. Mary Gnaedinger’s Famous Fantastic Mysteries digest ran from 1939 to 1953, sometimes monthly and sometimes bimonthly, reprinting old and newish science fiction and fantasy. The demand for this material was so great—or at least, there was so much material—that Gnaedinger started a companion magazine, Fantastic Novels. The exterior presentation of Famous Fantastic Mysteries has little to distinguish it from its many pulp contemporaries that published new work—such as Science Fiction Quarterly or the grand old magazine Weird Tales. But the inclusion of out-of-print works by Bram Stoker and Jack London was a different kind of draw. At that point, there were still readers who remembered these stories from their youth. But Famous Fantastic Mysteries had another, youthful, audience, for whom its recoveries were a revelation. Fantasy fandom, always self-conscious about its newness to the literary scene, was beginning to gain a sense of history.

Among this young audience were Doug Menville and Robert Reginald, two young Californians who had met at a newsstand in Hollywood and who, in the early 1970s, would embark upon an ambitious recovery project of their own. Doug Menville recalls in an email to me that he discovered Famous Fantastic Mysteries at the age of ten, accumulated a full run of the magazine, and thereafter began avidly to collect the works of Wells, Rohmer, and especially Haggard. The timing for such collecting was good, since original editions of early fantastic literature were still available at reasonable prices in the used bookstores if one knew where to look. In the late 1960s, Robert Reginald (the literary pseudonym of Michael Burgess) had compiled the first bio-bibliography of science fiction writers as an honours project at Gonzaga University. So between Menville’s collecting and Reginald’s bibliographical industry, they were well prepared when the booksellers whose newsstand they frequented (Al and Joe Saunders) decided to move into publishing and enlisted Doug Menville’s help as editor.

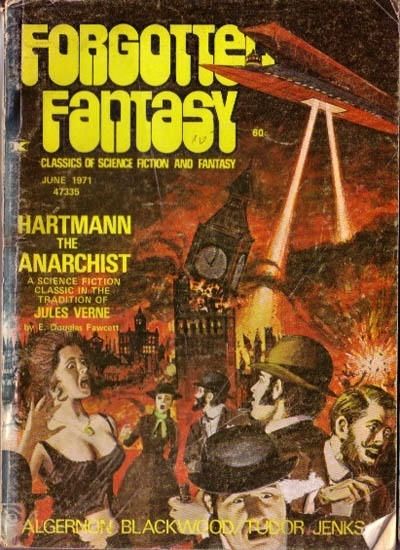

The result was Forgotten Fantasy Magazine (FFM), a digest-style magazine with Menville as editor and Reginald as associate editor, which ran bimonthly from October 1970 to June of 1971, for a grand total of five issues. Each issue was 128 pages long and had a newsstand price of 60 cents. The first centrepiece was the very strange 1892 underground-civilization tale The Goddess of Atvatabar by George Bradshaw, serialized across the first four numbers[3]. The editors selected and reprinted a variety of material, not only to vary the pace and to fit the digest format but to display precedents for the imaginative fantasy canon in a variety of genres, from kunstmärchen and ghost stories to poetry and utopian or prophetic fiction. This chameleonism as to genre is a function of SF’s legendarily tolerant inclusivity, which has found its voice diversely in, among others, Morris’s medievalist cantifables, the interplay of graphic and textual media in comic books (capable of, in works like Stern and Steininger’s Beowulf or Frank Miller’s 300, mining their material from both epic and history), and prose didacticism of all kinds (from Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia on up to fundamentalist romances such as the Left Behind series). So in addition to providing a novel in serial, Reginald and Menville printed poems by lesser-known Decadents and Romantics like Richard Le Gallienne, Matthew “Monk” Lewis, and Thomas Lovell Beddoes; short stories such as H. G. Wells’s “The Valley of Spiders” and Edith Nesbit’s “Man-Size in Marble”; and William Morris’s early novella-length romance The Hollow Land. The latter found what was probably the finest treatment among the covers of the five issues, with Tim Kirk’s illustration of the hero falling off the cliff against an eerie green background which seems to bleed greenly into his bushy blond Viking moustache. Each issue’s cover was designed specifically for the magazine by one of three artists—George Barr, Bill Hughes, and Tim Kirk. Since a colourful mediation of the contents on the cover was indispensible to any SF digest magazine, those cover illustrations comprised FFM’s only really sizeable monetary outlay.

Fig. 1

Forgotten Fantasy Magazine 1.1 (Oct. 1970)

Opening page spread. Courtesy of the Merril Collection of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Toronto Public Library.

Fig. 2

Forgotten Fantasy Magazine 1.5 (June 1971). Cover

Courtesy of Galactic Central (http://www.philsp.com/).

The decorations within came from copyright-free works of Art Nouveau and Victorian book-decoration, via Dover collections such as Ernst Lehner’s Alphabets and Ornaments (1952). Photo offset printing allowed the editors to reproduce these decorations as well as the original illustrations to works like The Goddess of Atvatabar. It was not specifically a facsimile reprint project, but as Menville recalls, they “wanted to present the old stories as they originally appeared, whenever possible.” The result was not exactly a historically consistent layout, but certainly one that collages the antiquarian with the up-to-date. In the contents page and frontispiece of the first number of FFM, for instance, the display type of the title seems to tread a middle path, if there is one, between Wild West and Computer, while the Art Nouveau frontispiece and the little triumphant jester capture the zeitgeist of 1970 equally well with that of 1890. In the bottom left of the copy reproduced here is a bit of provenance information which similarly reveals something of the carefree spirit of the late 60s: the stamp of the “SPACED OUT LIBRARY”—the original name for the Toronto Public Library’s Science Fiction and Fantasy collection, before it was given the more professional-sounding title “The Merril Collection.” The “Features” include Doug Menville’s editorial (titled “Excavations,” devoted in this issue to Famous Fantastic Mysteries and to the accessibility of other sources of reprint fantasy) and a “Prognostications” section, which hints at future issues, including “A short science fiction tale by—Voltaire!” The “Calibrations” feature was devoted to book reviews, including generous notices of other classic fantasy reprints, mostly from Ballantine, that were currently being made available. In the third volume, a letters section would be added, entitled “Articulations.”

The letters section is an essential part of any digest magazine, and of none more so than an SF magazine. Whether a reader’s feedback was implemented or not, his or her letter was still a way of gauging the magazine’s qualities and the nature of its appeal; the reader’s comments could even dictate sensitive adjustments to the overall mechanism of the magazine, affecting its forward motion. I do not mean to suggest that FFM or any other such science fiction magazine was a collective project, but the very active letters section of FFM reflects SF fandom’s avidity and willingness to criticize.

As the initial point of contact, the covers of FFM were a natural point for comment for readers, and they were eager to contribute their opinions. For every reader who enjoyed “the old stereotype illustrations” and thought they might serve for the cover as well, there were others who wanted to suggest a more contemporary direction. As one reader, Charles W. Wolfe, wrote in the letters section of the third number,

No one wants to visualize his hero in a derby hat, and with a soup-strainer such as worn by Theodore Roosevelt / Howard Taft, etc. No one wants to see the heroine in a high bodice, corset, ankle-length dresses, button shoes, etc. Illustrations must be sexy in the modern vein.

126

Wolfe’s use of the absolute “no one” here attests to the stake many readers felt they had in the project. Ray Bradbury’s letter in the same issue took the opposite tack (and, indeed, a less peremptory tone) in his critique of the first issue’s cover: “I am tired of naked ladies gesturing at maelstroms, but obviously I grow old, and just as obviously others find these sad ladies worthy of attention” (127). You can’t please everybody, but the clashing of readerly tastes and desires here is one of the difficulties an SF editor inevitably confronts. Wolfe’s critique of steampunk fashion avant la lettre is a little puzzling, not least because it’s hard to imagine what would be more appropriate to the subject matter, or less expensive to the editors. Bill Hughes’s cover to the final number (June 1971) introducing E. Douglas Fawcett’s 1893 dirigible warfare story Hartmann the Anarchist, includes, in seemingly explicit defiance of Charles W. Wolfe’s strictures, a crowd of frightened Londoners sporting variously a derby hat; plentiful masculine facial hair; a high bodice; and (judging from the prominent cleavage at the bottom left) perhaps a corset as well. The only concession to modernity is that these remnants of nineteenth-century fashion are seemingly about to be crushed by the toppling Big Ben.

An audience for forgotten fantasy certainly existed in the early 70s; they self-identify in the letters section as old and young, as those who remembered the stories as antiquarian curiosities dimly remembered from decades before and as those who were struck by them for the first time. Established writers such as Ray Bradbury wrote in to count themselves among the readership, as did academics looking for a canon to give background to the SF courses that were currently springing up on college campuses. There were those who were excited at the archaeological prospect of recovering an entire unknown corpus of nineteenth-century fantastic literature, those who thought that something like The Goddess of Atvatabar was “cruddy” and “inane” and should never have been published at all, and those who (like the readers who wrote in asking if they could contribute) did not fully understand the purpose of the magazine. But even those in the last category were doing what SF readers all did: they wrote, they drew, they collaged, they digested, they anthologized, and they criticized. SF was from the very first a genre that encouraged its readers to be active, creative, and assimilative. Menville recalls receiving “many letters of encouragement, some with suggestions for future reprints, as in the old [Famous Fantastic Mysteries and Fantastic Novels] letter columns.”

In the end, according to Menville, the greatest difficulty with the magazine was distribution. As he explains,

There was very little market at the time for digest mags (although F&SF and Analog seemed to make it through OK, but they were already well established). Our distributors cheated us and often returned bundles of magazines unopened. Also, there was no longer a large market for old fantasy and SF; newsstands and bookstores were deluged with hundreds of new SF and fantasy books by new and well-known authors. By June 1971 we knew that our baby was doomed; we couldn’t compete in the magazine market with antiquated fantasy fiction.

So the market itself was moving towards books and away from magazines. Menville’s wry comment on “antiquated” fiction is also telling; science fiction, more than fantasy perhaps, is a genre that requires constant novelty; looking backward is not a viable option. That is another reason why, although Menville and Reginald could adopt Victorian and Edwardian decorations inside the magazine, on the cover FFM had to opt for the modern approach, relying on whatever colourful modern invention their illustrator offered them. On the newsstand, FFM appears to be a fairly standard SF digest, and it is hard to say whether that was comfortingly familiar or merely more of the same to its prospective purchasers.

FFM never really had a chance to test the effectiveness of its marketing strategies and exterior presentation. In the “Excavations” column of the fourth number, Menville announces that

so far, in terms of sales figures, it looks like we’re doing only average for a new magazine. The mechanics of distribution are such that only now as this is being written (in late November [1970]) are we getting some preliminary figures on the sale of the first issue! And they seem to indicate about 25 per cent sales. Well that’s not as bad as it sounds, when you consider that all magazines are in trouble today, sales are down almost two-thirds on all of them, and sadly, several SF titles are folding.

5

It is a little odd to find an editorial offering such a bald assessment of the magazine’s chances of survival so early in its life cycle (“only average”). And having worked briefly in a magazine store, I can attest to the amount of pulping that is still done today. But Menville’s words, besides being a strategy to drum up support and sympathy, also suggest the investment of readers in the SF community; the printing of SF works is cast here as having personal significance for reader and editor alike, and Menville obviously feels that his readers have a desire, and a right, to know how the magazine is trending. In his email to me, Doug Menville further explains that one of the contributing causes to the failure of FFM was the profusion of new SF book titles (“hundreds,” he says) — so that the Forgotten Fantasy recovery enterprise, which had been driven by the popularity of SF and the cheapness of new forms of publication, was in a way also killed by those same factors. FFM number 5 shows no signs of stopping, promising in the next issue the conclusion of Hartmann the Anarchist—but that fifth number was the magazine’s last.

After the demise of FFM, the editors’ backers suggested a paperback book format instead (if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em), and the focus shifted from the digest format to reprinting entire books—mostly novels. At the same time, the ever-industrious Menville and Reginald were also editing a series of reprints from the Arno Press in New York. R. D. Mullen’s 1976 review in Science Fiction Studies has a detailed bibliography of the Arno reprints, which tended more particularly to science fiction than to medievalist or fantastic literature. The Arno titles, for instance, include Richard Jefferies’s eco-dystopia After London: Or, Wild England (1885) and Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague (1915), along with Hartmann the Anarchist finally published in its entirety. Incidentally, The Scarlet Plague had been printed in Gnaedinger’s Famous Fantastic Mysteries (in 1949), so that as with FFM the digest magazines seem to have unintentionally served as test markets for the reprint series. At any rate, reprinting books in their entirety was perhaps easier work than editing digest magazines, since full reprints would certainly require less cutting and pasting than the labour-intensive magazines; similarly, as Maggie Hivnor reminds us in “Reprint Rights,” the reprint business tends not to require much overhead in comparison with printing new books (91). That did not stop reviewers like Mullen from suggesting that the prices of the hardcover Arno reprints were rather too high (179).

Menville and Reginald launched the Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy series in September 1973, with the publication of William Morris’s 1890 romance The Glittering Plain. In all, 24 paperback titles would be printed in the Newcastle series, with Haggard and Morris making up a little more than half of them, although the editors also resurrected more obscure works like Alfred Noyes’s Aladore (1914) and Edwin Lester Arnold’s Wonderful Adventures of Phra the Phoenician (1890). Again these works were printed in essentially facsimile form—done not (or not only) for reasons of historical fidelity, but as a way of exploiting photographic offset printing to keep costs down. Since the originals often came from Doug Menville’s own collection, the facsimile form is also a sign of the collector-as-editor ethos that had informed the earlier digest format. Joe Sanders (no relation, as far as I can tell, to the Saunders brother of that name) writes in 1976 of the necessity for adopting “authoritative” texts (305) for facsimile reprints from among the various editions of classic SF, and his article describes the treacherous variety of often hastily-printed texts that the reprint’s editor had to choose from. Certainly the Forgotten Fantasy Library was far from strenuous in its choice of copytexts; Robert Reginald’s claim that “we usually chose the books for each of the two annual sales cycles just a few months before they had to go to press” suggests that he and Menville did not spend much time agonizing over textual matters, but reprinted whatever book they had on hand. The result is a paperback that certainly reproduces a particular historical snapshot of the text, but which is hardly an authoritative edition—or even a new “edition” at all in the textual sense.

Fig. 3

The House of the Wolfings, by William Morris. [1889]

The editor/publisher still found ways of insinuating new material into the edition (even if it was only the company logo), and even again to assert his own presence in the tradition of fantastic literature. The final page of the Newcastle edition of Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair, William Morris’s very loose retelling of the medieval romance of Havelock the Dane, is a striking example of this kind of historical consciousness. The Newcastle editors chose to reprint the edition of Thomas Bird Mosher, the American publisher who pirated so many of the classics of the Victorian aesthetic movement; because his editions of many of these works are still readily available in North American used bookstores, the Mosher edition—composed at Mosher’s press using a Kelmscott edition as copytext—would have probably formed part of Doug Menville’s collection. Morris’s Kelmscott books each end with a colophon; in this case, Mosher faithfully if unnecessarily repeated Morris’s colophon at the end of his own edition, simply adding the circumstances of his own printing to it. The Newcastle editors in turn naturally inserted their own colophon in imitation of Mosher, in a different, slightly darker typeface, so that the Newcastle edition has essentially three colophons on one page, marking successive printings for three very different audiences in 1895, 1900, and 1977. This triple colophon is simultaneously a textual note, an ex libris (since the copytexts in each reprint were from the printer’s own collection), and an assertion of the way in which Reginald and Menville show their own self-awareness as enthusiasts and collectors participating in the process of textual recovery, transmission, and recontextualization. This colophon also likely marks the only real intervention of the Forgotten Fantasy editors into the text, since the text was entirely reproduced from the Mosher edition.

Fig. 4

The Story of Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair, by William Morris. [1895]

The first Newcastle books (like Morris’s The Glittering Plain) were given generic covers which Menville, who designed them, characterizes as “rather crude,” but after the fourth book in the series Menville and Reginald came to an arrangement with artists such as George Barr who provided illustrations for the covers[4]. It might have been possible to take a Morris design of some kind for the cover of the Morris works, and indeed on the back they adopt a Kelmscott initial, while the Menville-designed cover to Rider Haggard’s Saga of Eric Brighteyes adopts an illustration from an earlier edition. But for the most part copyright issues would have precluded using designs by Morris and Co., and anyway these covers are purposely not Morrisian, nor even Victorian; they are for the contemporary reader and fan of fantastic literature in the 1970s. The cover to The House of the Wolfings, for instance, owes very little to the Germanic migration-age narrative that Morris tells in the story itself; there are no mounted knights in the story (this one bears an uncanny resemblance to Bill Kreutzman, one of the drummers for the Grateful Dead around this period), and the hippy princess here does not carry a lamp as the Hall-Sun does in the story. Likewise, Child Christopher on the cover of the Newcastle edition of that book looks more like a square-jawed swashbuckler against a lurid red background than like the woodsman of Morris’s own romance. The often abstract covers of the better-funded Ballantine editions are more imaginative, and indeed more suggestive of the books’ contents, than these rather concrete fantasies of a barbarian age, and with the exception of the corsets and “soup strainer” moustaches on the cover of the last issue of FFM there is almost nothing nineteenth-century about them. But of course none of these projects of textual recovery, from Famous Forgotten Mysteries to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series and the Forgotten Fantasy digest and the series that followed it, were overly concerned with aesthetic faithfulness to their Victorian originals, and there is no reason why they should have been (even their typographical fidelity to the originals may be attributed to expediency). They were products of a time when fantastic literature was still looking for its own place in SF fandom and within literature in general. The genre now has its acknowledged definitive works, and they are mostly from the mid-twentieth century; “forgotten fantasy” is not now forgotten, but is part of the genre’s prehistory.

The Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy Library series lasted until 1980; the more prolific Ballantine Adult Fantasy series had ended in 1974. Many of these paperbacks, however, especially the Ballantine reprints, are still to be found in used bookstores and are only now being superseded as the readiest points of access to much of Victorian fantastic literature. It is difficult to quantify these projects as successes or failures along the lines of general expectations for contemporary SF; although some of the Ballantine books did make it into multiple printings, sales were never high, and the cheap format and rough-and-ready editing practices of especially the Newcastle series suggest that these books were not published with the expectation of large profits. Nor were they even published for the high-minded purposes of recovering great lost works or establishing a definitive body of Forgotten Fantasy Literature for future generations to defer to, although the assertion of personal taste was certainly an essential part of the editors’ modus operandi. The reprinting of “forgotten fantasy” in the 1970s was an experimental venture in the hope of finding or creating an untapped market; it was probably an opportunity to cash in on works that were out of copyright; it was certainly an antiquarian project of textual recovery and enjoyment; and it may even in a sense have been an attempt to justify the genre by finding the roots of fantastic literature in the respectable nineteenth century. Most important, though, the material body of “forgotten fantasy” as it appears in the editions of the 1970s is significant for historians of the book as representing a exercise in textual recovery that relied for its impetus upon small publishers, avid book collectors, and above all interested readers. The fantasy reprint enterprise reveals the ways in which enthusiasm, collaboration, and a desire for novelty have always been defining characteristics of the niche market of SF, and the textual and paratextual forms of these reprints illustrate the circular feedback processes of SF fandom, which run back and forth along the book chain, blurring the arbitrary boundaries between author, editor, artist, publisher, reader, collector, and fan.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Yuri Cowan's post-doctoral research in the Research Project on Authorship as Performance (RAP) at Ghent University concentrates on nineteenth-century literature, historiography, and medievalism. His doctoral dissertation at the University of Toronto (2008) was entitled William Morris and Medieval Material Culture and he has published articles on Morris; on George MacDonald and the Aesthetic Movement; on William Allingham's Ballad Book; and (forthcoming) on the relationship of material bibliography to digital editions and archives.He is currently researching the history of editing, material bibliography, and authorship, especially as that history illuminates the circumstances of the publishing, form, and reception of nineteenth-century editions of ballads and medieval texts.

Notes

-

[1]

I would like to thank Doug Menville and Robert Reginald for their kind emails and detailed reminiscences, as well as the Merril Collection of Science Fiction and Fantasy at the Toronto Public Library for their aid in research and permission to reproduce material, and Phil Stephensen-Payne of Galactic Central for similar permissions. I am also grateful to Ian Young for finding and contributing many classic fantasy paperbacks for my own collection.

-

[2]

The typography of the Ballantine titles is very diverse and often incongruous with the subject-matter, ranging from Edwardian flourishes (Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter) to psychedelic bubble-lettering (Fletcher Pratt’s The Blue Star) to inexplicable chinoiserie (Morris’s Water of the Wondrous Isles).

-

[3]

In this, too, the digest magazine adopted one of the loyalty strategies that Altick associates with the earliest reprint series:

Closely associated with the series concept—they developed side by side in the eighteenth century—is the practice of publishing a book in instalments. From the publisher’s standpoint, number-or part-issue not only has the advantages just attributed to the series but in addition, by spreading the book’s cost to the purchaser over a period of time, makes it seem lower than it actually is. Many classic reprint series during the first two-thirds of the century—Cassell’s various illustrated editions of literary masterpieces offer examples from the 1860s – were initially issued in weekly or monthly numbers at a few pennies each, with the completed volume becoming available immediately upon the end of the part issue.

-

[4]

As Doug Menville describes it, “We made a deal with George whereby he charged us less than his usual fee in exchange for our returning his original paintings to him, so that he could sell them at conventions. This worked out well for all of us.”

Bibliographie

- Famous Fantastic Mysteries 1.1-14.4 (September 1939-June 1953).

- Forgotten Fantasy Magazine 1.1-1.5 (October 1970-June 1971).

- Haggard, H. Rider and Andrew Lang. The World’s Desire. [1890]. Ballantine Adult Fantasy. New York: Ballantine, 1972.

- Machen, Arthur. The Three Imposters. [1890]. Ballantine Adult Fantasy. New York: Ballantine, 1972.

- Morris, William. The House of the Wolfings. [1888]. Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy Library. Hollywood, CA: Newcastle Publishing, 1978.

- Morris, William. Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair. [1895]. Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy Library. Hollywood, CA: Newcastle Publishing, 1977.

- Altick, Richard. “From Aldine to Everyman: Cheap Reprint Series of the English Classics 1830-1906.” Studies in Bibliography 11 (1958), 3-24.

- Bosky, Bernadette. “Amateur Press Associations: Intellectual Society and Social Intellectualism.” Science Fiction Fandom. Ed. Joe Sanders. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 1994. 181-197.

- Brouillette, Sarah. “Corporate Publishing and Canonization: Neuromancer and Science-Fiction Publishing in the 1970s and Early 1980s.” Book History 5 (2002), 187-208.

- brown, rich. “Post-Sputnik Fandom (1957-1990).” Science Fiction Fandom. Ed. Joe Sanders. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 1994. 75-102.

- The Haunted Bibliophile. “The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series.” <http://home.epix.net/~wallison/bafs.html>. Web. 30 April 2010.

- The Haunted Bibliophile. “The Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy Library.” < http://home.epix.net/~wallison/nffl.html>. Web. 30 April 2010.

- Hivnor, Maggie. “Adventures in reprint rights.” Journal of Scholarly Publishing. 32.2 (January 2001), 91-101.

- Matthews, Nicole, ed. Judging a Book by Its Cover: Fans, Publishers, Designers, and the Marketing of Fiction. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007.

- Menville, Doug. “Forgotten Fantasy.” Message to the author. 17 June 2009.

- Mullen, R. D. “The Arno Reprints.” Science Fiction Studies 2.2 (July, 1975), 179-195.

- Radway, Janice. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. London: Verso, 1984.

- Reginald, Robert. “Re: Forgotten Fantasy.” Message to the author. 12 June 2009.

- Sanders, Joe. “The SF Reprint Series: Scholarship and Commercialism.” Science Fiction Studies 3.3 (November 1976), 305-10.

- Stephenson-Payne, Phil, et al. Galactic Central. <http://www.philsp.com/>. Web. 30 April 2010.

- Superdickery.com. Web. 30 April 2010.

- Weinberg, Robert. “The Fan Presses.” Science Fiction Fandom. Ed. Joe Sanders. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 1994. 211-220.

Primary Sources:

Secondary Sources:

Liste des figures

Fig. 1

Forgotten Fantasy Magazine 1.1 (Oct. 1970)

Fig. 2

Forgotten Fantasy Magazine 1.5 (June 1971). Cover

Courtesy of Galactic Central (http://www.philsp.com/).

Fig. 3

The House of the Wolfings, by William Morris. [1889]

Fig. 4

The Story of Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair, by William Morris. [1895]

![The House of the Wolfings, by William Morris. [1889]](/fr/revues/memoires/2010-v2-n1-memoires3974/045319ar/media/045319arf003n.jpg)

![The Story of Child Christopher and Goldilind the Fair, by William Morris. [1895]](/fr/revues/memoires/2010-v2-n1-memoires3974/045319ar/media/045319arf004n.jpg)