Résumés

Abstract

Hong Kong is probably one of the most exciting places in the world to study translation as a student or a researcher. Seven out of the eight universities offer translation degrees. Among others, journalistic translation has always been one of the most popular courses for students. However, students have often felt underprepared in journalistic translation even after taking some related courses. This study argues, with the support of empirical evidence that one of the major reasons accountable for this is the gap between institutional translator training and the real world of professional translation, which, in the context of journalistic translation, manifests itself as the difference in translation methods taught in translation programs and used in professional practice. The author further contends that this gap needs to be bridged in order to better prepare student translators for the market. Recommendations are also made as to how the gap can be narrowed or bridged.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- Hong Kong,

- journalistic translation,

- translator training,

- professional translation

Résumé

Hong Kong est très vraisemblablement une des villes les plus attrayantes au monde pour des études en traduction. Sept des huit universités offrent des diplômes en traduction. Entre autres, la traduction journalistique a toujours été un des programmes les plus populaires des étudiants. Toutefois, ceux-ci jugent souvent leur formation insuffisante, même après avoir suivi les cours liés au domaine. Cette étude montre, avec des données empiriques, qu’une des raisons principales du décalage entre la formation universitaire et la traduction journalistique en milieu professionnel se manifeste dans la différence des techniques de traduction enseignées à l’université et celles utilisées dans le milieu professionnel. L’auteur propose des suggestions pour réduire ce décalage afin de préparer adéquatement les étudiants au marché du travail.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Translation has always been an important activity in Hong Kong as a bilingual society. In the early 1970s, Chinese was first recognized as an official language along with English in Hong Kong. This legislation made it necessary for parallel bilingual texts to be prepared for official documents and communications (Lai, 1997). As a result, there was a burgeoning in Hong Kong of translating activities in all sectors. For a while, there was a shortage of translators and interpreters in Hong Kong. In response to this societal demand, translation courses were set up in universities and polytechnics to train translators and interpreters. Specialized translation, such as commercial, mass media, legal and government translation, has always been very popular among students and hence the foci in many translation programs. Take mass media translation for example. All seven local translation departments/programs offer one or more courses for specialized translation in mass media, though the titles of the courses vary from one to another (see table 1). Except for the University of Hong Kong (HKU), mass translation has been set up as term courses for three credits each. The University of Hong Kong and the Polytechnic University of Hong Kong (PolyU) both require students to take mass media translation, whereas others, including the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), the City University of Hong Kong (CityU), the Baptist University of Hong Kong (HKBU), Lingnan University (LU), and the Open University of Hong Kong (OUHK), offer it as electives.

Table 1

List of Mass Media Courses on Offer in Hong Kong Tertiary Institutions

Statement of the Problem: Translation or Trans-adaptation

Despite its popularity, students have generally found they are un- or under- prepared in mass media translation even after taking the courses. One of the reasons, I suspect, is the separation of the institutional translator training from the real world of professional translation. As I have observed, the teaching of mass media translation in Hong Kong has been focused on direct complete translation of media texts. However, is this what is required or expected of professional media translators? Mass media, taken broadly, are the channels of, the content within and the culture integral to, information in the public sphere. Media thus include not only newspapers, film, cable TV, wire services and the like, but also publishing houses, dictionaries, the Internet, mass e-mailings. Along the same line, media translation refers to translating texts in all the above media areas. To make my discussion focused, I would like to concentrate on how newspapers arrive at their Chinese translation/adaptation of English international news, which is probably the most important aspect of mass media translation in Hong Kong today. My research questions, therefore, become:

What methods are used in translating English news into Chinese in Hong Kong?

What methods are being taught in local translation programs?

How are they similar or different?

What implications for teaching of translation in general and journalistic translation in particular?

Survey of Local Newspapers

To answer the first question, we conducted a survey of the methods employed in the translation of all the international news published in four major Hong Kong newspapers for three consecutive days from the 8th to the 10th of December 1999. The four newspapers were the Mingpao Daily (明報), the Oriental Daily (東方日報), the Apple Daily(蘋果日報) and Wenweipo(文匯報). It is generally understood that the Mingpao Daily is targeted at educated middle class readers whereas the Oriental Daily and the Apple Daily are aimed at the working class. Wenweipo is known to be supported and funded by the Beijing government and thus receives strong influence from the Mainland in both the selection of news items and the methods of translating international news. Therefore, it is probably not far from the truth for us to say that these four papers are representative of the general situations of newspapers in Hong Kong.

The Results

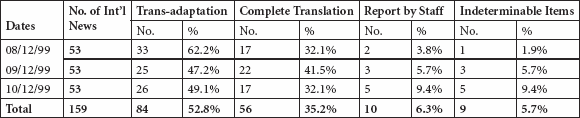

It was found that three methods were generally used by the four surveyed newspapers in transmitting and/or transferring English international news into Chinese, namely complete translation, selective trans-adaptation, and reports by their own news staff. The categorization of the transmission/transference method was determined according to the phrase indicating the source of the news items given in the dateline of each piece. The news marked “Summary Report (綜合報道)” was considered a trans-adaptation, or a selective translation; news marked with the name of a news agency, for example, Associated Press (美聯社), was deemed a direct translation from a news dispatch received from international news agencies. The third category was straightforward, as the news under this category was often clearly identified as supplied by the news staff of the newspaper. Among the three methods, selective trans-adaptation was used most often, with an average of 52.8%; a little over one-third of the news items were complete translations of news dispatches from international news agencies (see Table 2).

Table 2

Translation Methods Used in the Four Major Newspapers in Hong Kong during 08-10 December 1999

Wenweipo used mostly the method of direct complete translation of news dispatches received from news agencies, with 83.4%, 76.9% and 53.8% respectively for the three days (see Table 3). Among the dozen of international news published every day, only one item was adapted rather than directly translated from English.

Table 3

Translation Methods by Wenweipo

In the Mingpao Daily, trans-adaptation was the most important method for translating international news. A little less than two-thirds of the international news was trans-adapted into Chinese and less than one-third was translated directly from English news dispatches. None was supplied by its own report staff (see Table 4).

Table 4

Translation Methods by the Mingpao Daily

The Oriental Daily used mainly trans-adaptation as well. For instance, over 80% of the international news that came out on December 8th was trans-adaptation and less than 10% was direct translation from English news dispatches (see Table 5). On average, approximately over 70% was trans-adaptation for the three days.

Table 5

Translation Methods by The Oriental Daily

Similar to the Oriental Daily, 90% of the international news that appeared in the Apple Daily on the 8th of December was adaptations while none was translated directly from English news dispatches from international news agencies. On average, approximately 72% of the international news was adapted rather than translated during the three days.

Table 6

Translation Methods by The Apple Daily

In summary, an average of 68.5% of the international news was translated using the method of trans-adaptation for three newspapers including the Mingpao Daily, the Oriental Daily and the Apple Daily during December 8th or 10th 1999. Wenweipo, however, seemed to have taken a complete different approach to the translation of international news, that is, it mainly relied on direct complete translation from English news dispatches received from international news agencies. Over 70% of the international news that appeared in it during the survey period was direct translations (see Table 7).

Table 7

A Comparison of Trans-adaptation and Translation by the Four Newspapers

Discussions and Implications

The Gap between Translation Training and the Real World

According to this survey, the dominance of selective trans-adaptation as transmission/transference method in the handling of international news is very obvious for all the newspapers but Wenwuipo. However, according to a brief telephone survey of six teachers of mass media translation in Hong Kong, all taught only or mostly complete translation in the course. Only one teacher reported that some trans-adaptation was taught in addition to complete translation. Three major reasons are accountable. First of all, traditionally, translation is defined as a complete transference or transmission of meaning from one language to another in which faithfulness and equivalence in meaning and message are two key conditions and criteria for translation. Any deviation from the original meaning or even the original form was considered bad or inadequate translation. Teachers, who were taught such a definition of translation themselves when they were students, naturally think complete translation is the proper way. Also, many have come from a literature background where full translation has long been the primary mode of translation. Second, many teachers do not have any practical experience in journalistic translation though some may have translated literature. This lack of professional experience and hence little knowledge of the real translation world has prevented them from seeing the need for teaching trans-adaptation in a course of journalistic translation. Third, teaching trans-adaptation is probably more of a challenge for many teachers than direct complete translation due to their lack of experience in selective translation as well as the technicalities involved in adaptation as it is more of a creative writing task than is direct complete translation.

Apparently, there exists a tremendous gap between the reality of professional translation and the institutional translator training in terms of the methods of translating international news from English into Chinese.

Bridging the Gap?

For years, many, academics and practitioners alike, have sounded the call for innovation in translator training (e.g. Kiraly 2000). One of the concerns for the translation training community is the gap between institutional translator training and the real world of professional translation. Some have argued that translator training is more a university education than a vocational training, and the focus should be placed on teaching knowledge about language and translation, and teaching students how to think. Pym criticized the current practice of translator training in Spain for not producing thinkers of translation.

[I] ntermediaries require more than technical expertise; they require a few of the ideals of a general humanistic education, able to transcend the outlooks of their cultures and professions of origin. That is why translator training in Spain is perhaps in danger of becoming too specific. We are churning out many technicians but few real thinkers. Ideally, students should be able to do more than find work in the market. They should eventually improve the intercultural relations they are engaged in. And that means having a few ideas about improving the market itself.

1993:120

He cautioned against any strong direct relation between market demands and the training of translators.

At a recent roundtable discussion on translator training and market needs held at the FIT Congress 2002, Mossop echoed Pym’s argument. To him, it is, and will always be, unrealistic to expect translation graduates to arrive in the workplace able to translate quickly and well, and therefore classroom training should be focused on reflection on translation problems and methods of translation, rather than simulated professional translation.

[T]ranslation schools are inherently limited in what they can do to prepare students for the workplace and that we should not make exaggerated demands on them. It has sometimes been fashionable to complain that the graduates of translation schools do not arrive in the workplace already able to translate quickly and well. But that’s always been an unrealistic hope, and always will be.

With a class of 20, the teacher can only look at a couple of hundred words a week per student, which isn’t much. There are no clients in the classroom, so it’s hard for students to develop a sense of what’s important and what isn’t based on a brief from the client. Some teachers have tried to simulate the workplace in the classroom, but in my view, that’s not what the function of a classroom is. The classroom should be used for reflection on the problems and methods of translation.

2002

However, others disagreed. Many have argued strongly for the need for closer links between institutional training and what some refer to as "the real world" of professional translation in order to ensure that students of translation are able to hit the ground running when they leave school/training courses (Dollerup, 1994; Pagano, 1994; Vienne 1994; James, Roffe and Thorne 1995; Klaudy 1995; Li 2000). For instance, Ulrych believed that "trainee translators need to be prepared for the conditions they will find in the working world" (1995: 253). Li also contended that authentic translation should be provided to students in order to reduce the “real world shock” for graduates at the workplace (2000).

Viaggio also criticized the current approach to translator training.

“Translators and interpreters are not currently trained as professionals, but taught a ‘do-as-I-do’ system inherited from the medieval guilds. Most are self-made, having acquired technique and applied it to languages already known. However, there is now enough known about mediated interlingual communication to teach translators and interpreters how to be successful practitioners… It is time for the translating and interpreting professions to develop professional training.”

1992

I myself favour professional training in translation programs for three reasons. First, students expect to be trained for the market when entering a translation program. In a series of surveys I conducted over the last couple of years on translation trainees, professional translators and translation administrators, the need to prepare students for the real world has stood out repeatedly as a major issue. Almost all the stakeholders felt strongly about linking translator training with professional translation. Second, while I fully support the position of training translation thinkers, I am not comfortable with leaving students’ needs entirely unattended. After all, they have come to our programs to be translators and to make a living with translation or other language skills after graduation. We could have left the part of practical training to the workplace. However, we all remember too well that almost all advertisements for translators require applicants to have several years of translation experience. Very few translation companies are willing to hire with the expectation to provide extensive on-the-job training. On the contrary, they expect the newly hired to already have a good understanding of the market and be quite well prepared for it. Apparently, students have been put into a catch-22 situation. They need practical experience in order to be hired. But without even an initial employment, they will not have the required experience. Therefore, some professional training at college in the form of simulated professional training and/or translation internship may provide them with some kind of practical professional experience, and is thus more than necessary.

Besides, I do not see provision of simulated professional training in the classroom in conflict with any goal of producing thinker-translators. What makes the real difference is the approach adopted in teaching. While providing simulated professional translation, the focus should still be on the development of students’ decision-making and problem-solving abilities. For that purpose, the reflective and process-oriented approach to translation teaching and learning should be used.

How to Bridge the Gap

An Integrated Approach to Translation Teaching To improve the teaching of translation in general and journalistic translation in particular, an integration of Gile’s process-oriented approach (1995) and Wilss’s practice-oriented approach (1996) should be of great help. Currently, teachers are taking mostly a product and/or practice oriented approach, in which they strive to provide students with as many different types of translation tasks as possible, hoping to familiarize them with the stylistic features and useful vocabularies of different media texts. This would have worked well but for two reasons. First, the time constraint makes it practically impossible to exhaust all the different tasks of journalistic translation. As Toury (1992) argued,

For translators to gain acknowledgement and recognition, they must acquire a set of translation norms. Norms are specific to sociocultural context, and at the same time are inherently changeable. Translators need to be aware of these characteristics. Because no translation training program can impart to students the whole complex of translation norms, even in a single culture, specialization has increased and the notion of social appropriateness in translation has been pushed aside. When trainees enter the real world of translation they must unlearn part of what they were taught and adjust to prevalent norms of appropriateness … students should be trained to consider what would be gained by taking a certain translation approach, what would be sacrificed, whether the gain is worth the loss, and whether there are alternatives with a better balance of gain and loss … This approach could open students’ eyes to the many possible translation norms

Secondly, the translation market is fast changing. Apart from preparing our students for the unpredictable (Almberg 1997), we also need to prepare them for the future (Mossop 2002).

For this purpose, the process-oriented approach can and must be integrated into the teaching of journalistic translation. According to Gile (1993), the process-oriented approach has the four basic characteristics.

During the process-oriented part of the course, trainees are considered as students of translation methods rather than as producers of finished products… Teachers take a normative attitude as far as the processes are concerned. As regards the product, they put questions to the students whenever possible rather than criticize them. Processes are supported by theoretical models which explain and integrate them. Problem diagnosis can be done partly by analyzing the product and partly by putting questions to the students.

p. 108

However, I would like to add that in the process-oriented approach, translation is considered and learned as a reflective practice (Kiraly 2000). Students are to reflect on their translations and their process of translating, particularly the choices and decisions made and the strategies used. One strategy to this end is writing of translation journals. Journaling can help students develop their own translation theory as well as internalize the theories they receive from teachers and books, hence students’ eventual development of a unified theory of their own. (Li 1998)

The gist of the reflective process-oriented approach is to, by drawing students’ attention to the processes and hence the methods of translation, help them develop decision-making and problem-solving abilities which are required of translators as thinkers. An integrated approach to teaching journalistic translation, i.e, an integration of the traditional product- and practice-oriented approach and the process-oriented approach, will not only provide students with knowledge of the useful vocabularies and patterns necessary in translating different kinds of journalistic texts, but also enable them to develop understanding of the translation processes and methods, hence augmenting their problem-solving abilities as translation practitioners and thinkers. Students trained in this model will generally have much greater professional confidence upon completing the course.

Teachers’ Knowledge of the Real World

Bridging the gap between translator training and the real world of professional translation requires authentic training as well. Authentic training includes at least two parts: authentic training materials and simulated professional translation. It is obvious that we should use authentic materials from the real translation world rather than materials contrived merely for translation practice. "All texts are authentic and unedited texts, selected because they present real-life translation problems" (Dollerup 1994: 124).

To provide simulated professional translation, it is imperative for teachers to have a good knowledge of professional news translation/adaptation. Unfortunately, many teachers today do not have the needed understanding of the real world. Several reasons are accountable for this. First, many teachers do not have any practical journalistic translation experience before or after they join the teaching profession. This is in part attributable to the current hiring system adopted in tertiary institutions, requiring teaching staff to be PhD holders. As we all know, few translation practitioners hold PhD degrees. Therefore, such a system effectively limits the number of experienced translators to be hired or even entirely excludes them from the teaching profession. Second, universities generally do not allow their teaching staff to be engaged in any professional translation though translation of books for publication is allowed. Consequently, teachers who join the training profession without any practical journalistic translation experience will not be able to gain any such experience on the job. Even for the few who become teachers with prior experience in journalistic translation, they gradually become unfamiliar with the real market of professional translation after a couple of years of teaching. Few can maintain a close contact with the translation world.

Needs Assessment

This problem of teachers’ lack of knowledge of the real profession defies any easy solution. Regular needs assessment might be a possible remedy (Li 2001). To our own benefit, we might consider building such needs assessment into our research project. This can be a quite effective way of establishing and maintaining ties with the translation profession. My recent experience makes a good testimony in this respect. Driven by a strong desire to understand the local translation market and needs of translation professionals and agencies, I have started a project on the relationships between societal needs and translation teaching in Hong Kong. As part of the fieldwork, I have conducted questionnaire surveys, followed by informal interviews, with professional translators, administrators of translation/language service agencies in addition to translation teachers and students. I have found these meetings extremely informative, enlightening and even instructional, which has helped me tremendously in linking my teaching with the professional world.

Collaborative Research

Another possibility is to develop research projects in collaboration with professional translators and/or translation agencies. For this purpose, the action research method can be of good use. Elliot defines action research briefly as “the study of a social situation with a view to improve the quality of action in it” (1991: 69). Action Research is the process by which practitioners attempt to study their problems scientifically in order to guide, correct, and evaluate their decisions and actions. It has the potential to generate genuine and sustained improvements in an organization. It gives practitioners new opportunities to reflect on and assess their translation; to explore and test new ideas, methods, and materials; to assess how effective the new approaches are; to share feedback with fellow team translators; and to make decisions about which new approaches to adopt in their translation practice.

Collaborative action research has two advantages. First, such research requires involvement and active participation of research subjects. Thus it is not something done to or on the translators or administrators but something done by them. Second, the focus of action research on reflective practice and consequently, the empowerment of the research participants means further training of translation practitioners (many translation administrators were once and/or still are translation practitioners themselves).

Exchange Programs

Martin (2002) suggested that some kind of exchange programs between translation teachers and professional translators may be another option in the attempt to narrow the gap between translation training programs and professional translation. That is, a full-time translator from a translation agency, perhaps with some background in teaching, transfers to a university for part of a semester and teaches a particular translation-related course there; and in return a teacher at the university can come to work at the translation agency. Such swaps are logistically very difficult to organize, but should not be impossible, especially considering the benefits they can bring to the training institutions and the translation profession. However, we must be aware that support of the administration is essential for such projects to bear fruit. The European Commission has gone half of the way towards such swaps by sending professional translators to teach in translation programs and is considering the implementation of the other half. Their experience may be summarized and disseminated later on for reference for other collaborative projects between universities and translation agencies.

Focus on Trans-adaptation

This brief survey of methods adopted in journalistic translation in Hong Kong also has direct implications for teaching news translation in Hong Kong. First, the focus should be readjusted from the current direct complete translation to trans-adaptation, since the methods used in professional news translation is predominantly trans-adaptation as revealed in the afore-mentioned survey. However, as complete translation is still very much practiced in the mainland or mainland-supported newspapers, students should also be made aware of this fact and be given practice in it. This is especially important considering the fact that an increasing number of Hong Kong college graduates are moving up north to seek employment in the mainland after the reversion of Hong Kong’s sovereignty to China and China’s accession to the WTO. The difficulty is to strike an appropriate balance between translation and trans-adaptation in teaching. Since students, as well as teachers, are generally more familiar with the former, we might consider beginning the course of journalistic translation with direct complete translation, and gradually move to trans-adaptation. In this way, students will receive training in both translation and trans-adaptation, and the focus on the latter is ensured.

In teaching trans-adaptation of international news, we need to familiarize students with some basic principles of news writing. For instance, how to create a catchy and informative news title in English and in Chinese? What is the basic structure of English and Chinese news (e.g. the inverted pyramid)? How to write a good news lead in English and in Chinese (see for example Rich, 2002: 155-173)? How are titles and leads different in English and Chinese, and what adaptations need to be made in the process of news trans-adaptation? Students need to know how to write good news in order to be able to produce a good translation or trans-adaptation of English and Chinese news.

Besides, to do a good job of trans-adaptation, students need to understand what makes good news for the targeted readership. Knowledge of news qualities, such as the novelty, proximity, timeliness, impact, conflict, prominence (see for example Hugh 1984: 2-3), can be of much help in the selection process of the trans-adaptation.

Conclusion

To sum up, the method that dominates transference/transmission of English international news into Chinese in Hong Kong is trans-adaptation. The traditional method of full translation plays only a minor role in the profession but more in the mainland or mainland-funded newspapers. Since for now students are taught only or mostly complete translation in journalistic translation, the gap is thus evident between translator training and the world of professional translation. To better prepare our students for the profession, we need to narrow, bridge or, if ever possible, eliminate the gap.

For this purpose, emphasis should be laid on the teaching of trans-adaptation rather than direct translation, though the latter is to stay given the prospect of our graduates working for mainland newspapers. More importantly, the focus of training should be placed on the process and reflective practice of translation so that students will ultimately develop good decision-making and problem-solving abilities utterly needed by professional translators. We are not to train practitioners only, nor thinkers alone, but translator-cum- thinkers.

Parties annexes

Note

-

[1]

This study was supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the HKSAR, China (Project No. CUHK 4272/01H).

References

- Almberg, N. S. P. (1997b): “Where to begin: Top-Down or Bottom-Up”, Presented at the Conference on Translation Teaching, Hong Kong.

- Durban, C., Martin, T., Mossop, B., Schwartz, R. and C. Searls-Ridge (2003): “Translator Training and the Real World: Concrete Suggestions for Bridging the Gap”, Translation Journal 7-1.

- Dollerup, C. (1994): “Systematic feedback in teaching translation”, in C. Dollerup and A. Lingarrd (Eds.), Teaching Translation and Interpreting 2 (pp. 121-132), Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Elliot, J. (1991): Action Research for Educational Change, Milton Keynes, England, Open University Press.

- Gile, D. (1995): Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Hugh, G. A. (1984): News Writing, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company.

- James, H., Roffe, I. and D. Thorne (1995): “Assessment and Skills in Screen Translation”, in C. Dollerup and V. Appel (Eds.), Teaching Translation and Interpreting 3, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Kiraly, D. (2000): A Social Constructivist Approach to Translator Education: Empowerment from Theory to Practice, Manchester, St. Jerome Publishing.

- Klaudy, K. (1995): “Quality assessment in school vs. professional translation”, in C. Dollerup and V. Appel (Eds.), Teaching Translation and Interpreting 3, Amsterdam, John Benjamins.

- Lai, J. C. C. (1997): “What Lies Ahead for the Teaching of Translation in Hong Kong?”, Presented at the Conference on Translation Teaching, Hong Kong.

- Li, D. (1998): “Reflective Journals in Translation Teaching”, Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 6-2, p. 225-234.

- Li, D. (2000): “Tailoring Translation Programmes to Social Needs: A Survey of Professional Translators”, Target 12-1, p. 127-149.

- Li, D. (2001): “Needs assessment in translation teaching Making translator training more responsive to social needs”, Babel 46-4, p. 289-299.

- Pagano, A. (1994): “Decentering translation in the classroom: An experiment”, Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 2, p. 213-219.

- Pym, A. (1993): “On the Market as a Factor in the Training of Translators”, Koiné 3, p. 109-121.

- Rich, C. (2002): Writing and Reporting News: A coaching method, Belmont, Wadsworth/Thomson.

- Toury, G. (1992): “Everything has its price: an Alternative to Normative Conditioning in Translator Training”, Interface 6-2, p. 60-72.

- Ulrych, M. (1995): “Real-world criteria in translation pedagogy”, in C. Dollerup and V. Appel (Eds.), Teaching Translation and Interpreting 3, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Viaggio, S. (1992): “Translators and Interpreters: Professionals or Shoemakers?”, in C. Dollerup and A. Lindegaard (Eds.) Teaching Translation and Interpreting, Amsterdam, John Benjamins.

- Vienne, J. (1994): “Towards a Pedagogy of 'translation in situation'”, Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 1, p. 51-61.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

List of Mass Media Courses on Offer in Hong Kong Tertiary Institutions

Table 2

Translation Methods Used in the Four Major Newspapers in Hong Kong during 08-10 December 1999

Table 3

Translation Methods by Wenweipo

Table 4

Translation Methods by the Mingpao Daily

Table 5

Translation Methods by The Oriental Daily

Table 6

Translation Methods by The Apple Daily

Table 7

A Comparison of Trans-adaptation and Translation by the Four Newspapers