Résumés

Abstract

In this article, we explore the phenomenon of deictic center shifts in literary translation, concentrating on the Spanish translation (La historia siguiente, 1992) of the Dutch novel Het volgende verhaal (1991 [The Following Story, 1993]). The empirical description focuses on lexical spatiotemporal markers and verbal tenses. We compare the source text and the target text in order to identify the translational shifts: we consider these shifts as textual traces of the translator’s interpretive process of resetting the spatiotemporal coordinates of the discourse. We will argue that the deictic shifts between source and target text are related to occasional hesitations of the translator, who tends to emphasize the most salient deictic center. On a methodological level, we hope to show that a close reading of a translated text, taking into account its thematic and structural peculiarities, can contribute both to Translation and Literary Studies.

Keywords:

- deictic center shift,

- literary translation,

- lexical spatiotemporal markers,

- verbal tenses,

- proximal and distal demonstratives

Résumé

Dans le présent article, nous explorons le phénomène des déplacements du centre déictique en traduction littéraire, en nous centrant sur la traduction espagnole (La historia siguiente, 1992) du roman néerlandais Het volgende verhaal (1991 [L’histoire suivante, 1991]). La description empirique porte sur les expressions lexicales spatio-temporelles ainsi que sur les temps verbaux. Nous comparons les versions source et cible afin d’identifier les changements induits par la traduction : ceux-ci se présentent comme des traces textuelles du processus interprétatif du traducteur qui rétablit les coordonnées spatio-temporelles du récit. Nous argumentons que les déplacements déictiques entre les versions source et cible correspondent à des hésitations occasionnelles du traducteur qui a tendance à accentuer le point d’ancrage déictique le plus saillant. D’un point de vue méthodologique, nous tentons de démontrer qu’une analyse détaillée du texte traduit prenant en compte les particularités thématiques et structurelles peut contribuer tant à la traductologie qu’aux études littéraires.

Mots-clés:

- déplacement du centre déictique,

- traduction littéraire,

- expressions lexicales spatio-temporelles,

- temps verbaux,

- démonstratifs de proximité et d’éloignement

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

In recent years there has been a growing body of empirical research on deictic expressions in translated texts. The research questions vary from typological linguistic matter (Da Milano 2007) up to stylistically or ideologically oriented literary translation studies (Munday 2007). For linguistics, this type of research is valuable because the translated corpora give additional input for the difficult challenge of describing the semantics and stylistics of deictic expressions (Goethals 2007; Jonasson 2002; Whittaker 2004). For literary translation studies, these studies are valuable because they allow a search for rather volatile notions such as the narrator’s voice or subjectivity by examining structurally identifiable expressions (Bosseaux 2007; Jonasson 2001; Mason and Şerban 2003).

Following the second line of research, the present study will examine the translation of deictic elements such as spatiotemporal adverbial expressions and verbal tenses in a literary text. We will examine to what extent the translation affects the organization of the deictic center(s) in the text. Concretely, we focus on the Spanish (ES) translation La historia siguiente of the Dutch (NL) novel Het volgende verhaal (The Following Story, 1993) by Cees Nooteboom (1991).[1] By studying a language combination that has been studied rarely until now, one of our essential aims is to find new translational issues and their solutions, which may complement the findings of previous studies. Let us start however by making explicit some of our fundamental methodological and conceptual assumptions.

We consider the translated deictic elements as textual traces of re-contextualization, which is the interpretive process, realized by the reader and/or translator (i.e., the interpreter), consisting of resetting the context of a certain story. Indeed, the interpreter not only construes a mental representation of the story that is told, but also of the story-telling, and of the deictic center(s) from which the story is conceptualized.

Unlike oral speech, written speech can only be connected to an extratextual reality through the referential elements encoded in the written text. This distancing between text and utterance of discourse (Ricoeur 1976) is even more complicated in the case of a literary text because of its autotelic world-creating capacity, since context is created by linguistic devices in the text and cannot be verified by extratextual real-world situations. We have concentrated on deictic elements because they are key aspects of this contextual anchoring, that is, the “process by which cues in narrative discourse trigger recipients to establish a more or less direct or oblique relationship between the stories they are interpreting and the contexts in which they are interpreting them” (Herman 2002: 8; see also Kleiber 2003; Macías Villalobos 2006 and Philippe 1998 on deictics in literary texts).

Further, we assume that the translator leaves certain traces of his translational interpretation in the translated text and that these latent traces can be made manifest through comparative ST/TT analysis (Koster 2000; Naaijkens 2002). The ST/TT comparison allows for identifying the translational changes between both texts and clarifying which deictic features in the TT reflect the ST’s and which are to be attributed to the translational interpretation.

2. The deictic center: preliminaries

Although a complete review of deixis and the deictic center goes beyond the scope of this paper, we will give a brief outline of the narratological, translational, and linguistic aspects that are most relevant for our analysis.

2.1. Narratological preliminaries

Deictic elements in literary texts are related to the spatial, temporal and (inter)personal settings that orientate the reader whenever interpreting a narrative. Deictic elements are referring expressions whose semantics is not restricted to referring to an entity, but also includes invoking a deictic center, that is, the focalization point from which the spatial, temporal and (inter)personal information is given.

Within structuralist narratology, much attention has been paid to the observation that deictic centers may shift within one and the same narrative. One of the best-known shifts is the one between focalization points that are anchored to the narrating level (who speaks) and focalization points that are anchored to the narrated level (who perceives) (Genette 2007: 340). This narrating technique is frequently used in The Following Story (hereinafter TFS), as illustrated in excerpt 1.

In this fragment, different deictic centers are activated, prompting the reader to adopt alternatively the narrator’s perspective and the perspective of the character focalizing the event. The past tense (wist/knew) refers to a situation in the past, thus invoking a posterior deictic center, presumably anchored to the narrating level. Then we notice a shift coded linguistically by the use of a present tense (weet ik niet/do not know). The deictic center is now situated at the narrated level: it is the main character of the described situation who focalizes the events. Adverbial expressions like the previous evening versus last night confirm this deictic shift: whereas the previous evening suggests a moment situated before another moment in the past, last night refers to a past perceived from the deictic center.

It is important to note that shifting focalizations are not limited to above-sentence or paragraph level but also occur within one sentence. This is for instance the case when the author combines a past tense with adverbial expressions indicating proximity such as now (Vandelanotte 2004). This strategy is also frequently used in TFS. In excerpt 2, the past tenses (stond ik/I was standing; kende/knew) invoke the storyteller’s viewpoint whereas the temporal proximity in the adverb nu/now activates a deictic center anchored to the perspective of the character.

In addition to the structuralist interpretation of deictic shifts, a broader cognitive interpretation of the concept is advanced in recent works on narratology (Herman 2002; Zubin and Hewitt 1995). Instead of focusing on the shifts of the focalization point as textual features, the cognitive approach defines the concept as the general process “whereby narrators prompt their interlocutors to relocate from the here and now of the act of narration to other space-time coordinates – namely, those defining the perspective from which the events of the story are recounted” (Herman 2002: 271).

In our view, the cognitive interpretation of the concept deictic center shift offers an almost natural link to Translation Studies, since the translator is of all interpreters of a story probably the one who feels most compelled to execute this deictic shift, in order to be able to re-create the same story world for a new audience. Moreover, in translations we expect to find textual traces of the difficulties of performing this cognitive deictic shift. If we look at these difficulties not as personal errors made by the translator (or as unfortunate deviations with respect to the construct of an ideal interpretation), but rather as traces of the mental representation that interpreters prototypically construe when reading the story, studies on translations may actually enrich narratological research. Therefore, it is rather surprising that in reference works on narratology such as Genette 2007 or Herman 2002 very little is said about translation, or translated texts.

2.2. Translational preliminaries

Within Translation Studies, Richardson (1998) was one of the first to draw attention to the potential of studying deixis in translation. Later studies (Bosseaux 2007; Doiz-Bienzobas 2003; Krein-Kühle 2002; Mason and Şerban 2003; Şerban 2004; Whittaker 2004) have made important contributions by describing the translational deictic shifts in different text types, thereby considering different language pairs. All authors found that deictic shifts are pervasive in translations and may indeed affect the contextualization of the text. One of the most explicit conclusions was formulated in Mason and Şerban (2003), who in a corpus of Romanian-English literary translations made by non-native speakers of English found a consistent distancing trend: distals were relatively more frequent in the English translations than in the Romanian source texts. Thus, according to Mason and Şerban (2003: 290), the English translations “project a reader role which invites less involvement than that projected by the source texts”: whereas the source texts frequently activate a deictic center anchored to the narrated level, the translations tend to anchor it to a more distanced, and less involved narrator. Similar general conclusions about the translation of deixis may be found in Jonasson (2001), who observes a more objective rendering of demonstrative deictics in translation, or Bosseaux (2007), who finds a loss of deictic anchorage in the translation of deictic adverbs or pronouns.

However, an analysis similar to Mason and Şerban (2003) on a bidirectional Dutch-Spanish corpus did not confirm the general distancing trend (Goethals 2007). On the contrary, it revealed that the proximal-distal alternation varies considerably between different samples of the same translation direction. This sample variation was significantly higher than was the case with the shifts between demonstrative modifiers and definite articles (e.g. this house vs. the house), or the shifts between pronouns and explicit nominal constructions (e.g. this vs. this house).[3] So, for example, in the Spanish translation of the Dutch youth novel Belledone, there were five times more distancing shifts than approximating shifts, whereas in The Following Story, with the same translation direction, there were eighteen times more approximating shifts than distancing shifts. In Goethals (2007) we referred explicitly to the TFS case to argue that corpus research on translated texts should not only try to describe overall tendencies, but also pay attention to the individual samples which are part of the corpus (see Goethals 2008 for a similar point).

Hence, our starting point is a translation that shows a clear approximating trend. This quantitative trend cannot be explained by a systemic-linguistic contrast between Dutch and Spanish, since other translations with the same language pair show the opposite pattern. Neither can it be explained as a general characteristic of translations: compared with the data of Mason and Şerban (2003) it is even an exceptional case. In the study that follows, we will try to find out what this exceptional case teaches us about the fundamental mechanisms involved in the translation of deictic elements. Concretely, we will see that the exceptional narratological characteristics of this source text are important for understanding why this sample gives different results than other samples. Or, put in more general terms, that narratological features interfere in the translation process.

2.3. Linguistic preliminaries

From a linguistic point of view, NL-ES translation involves a paradigm shift in the demonstrative system. Dutch has a binary paradigm, distinguishing between proximals (dit/deze) and distals (dat/die), in a way that is similar to the English distinction between this and that. Spanish, on the contrary, has a triadic system, distinguishing between proximals (este/-a/-os/-as), medial-distals (ese/-a/-os/-as) and marked distals (aquel/-la/-los/-las).

The clearest difference between the two systems concerns the marked distal form in Spanish. Whereas all other forms in Dutch or Spanish involve a relative approximating or distancing of the referred entity with respect to the deictic center, the marked distal aquel explicitly separates it from the deictic center. Spatial aquel does not mean there but further over there (Butt and Benjamin 1994: 86). Temporal aquel does not simply express that the moment referred to is situated in the past, but rather that it is situated in a distant past that has no relation with the present. Because of this semantic potential, Spanish can for example also express the discourse deictic contrast between the former and the latter with the demonstratives aquel and este. As is the case with English this/that, the contrast between Dutch demonstratives is not strong enough for this contrastive reading. Other expressions, such as eerstgenoemde/ laatstgenoemde (first mentioned/last mentioned) need to be used.

Although the correspondences between Dutch proximals and distals, on the one hand, and Spanish proximals and medial-distals on the other should be examined in further detail, it is correct to say that there are no grammatical reasons for using or not using the most equivalent form (i.e. Spanish proximal for Dutch proximal and Spanish medial-distal for Dutch distal), at least as far as the spatiotemporal markers in our study are concerned. Of course, although the choice between them does not cause ungrammaticality the forms are not synonymous, for they may yield a different conceptualization of the situation. Roughly speaking, proximal este situates the referred entity nearby the speaker, and medial-distal ese situates it nearby the hearer and/or away from the speaker (Da Milano 2007; Jungbluth 2005).

Summarizing, translating Dutch demonstratives into Spanish may yield: (1) marked choice for aquel, introducing in the TT a marked distancing effect or (2) a choice between este and ese which is not governed by grammatical rules, but which may yield a different conceptualization regarding the relative approximating or distancing with respect to the deictic center.

3. Case Study: Het Volgende Verhaal [The Following Story] and its Spanish translation

For the presentation of the empirical data, we draw on the methodological guidelines proposed in Koster’s (2000) Armamentarium. First, a description of the ST novel will show that the search for the deictic center is an essential element in the text, both structurally and thematically. Second, we will focus on the Spanish TT, independently from the Dutch ST. We will show that the deictic center is manifestly unstable, particularly in the opening scene of the Spanish TT. Finally, and most importantly, we will compare the Dutch ST and the Spanish TT, focusing on spatiotemporal markers and verbal tenses. The ST/TT comparison will allow us to identify which deictic instabilities in the TT reflect the ST’s and which are to be attributed to translational interpretation.

3.1. Thematic discussion of the novella: metamorphosis and the search for spatiotemporal and interpersonal coordinates

The underlying theme of the novella is the multiple metamorphoses of man: during life, when an individual may assume multiple identities, in the transition from life to death, or in the metamorphosis of our experiences when we remember them, or tell about them (Bekkering 1998; Hottentot 1994). In this unstable world, man is in search of temporal coordinates (How is now to be understood? Is it the moment of experiencing, of remembering, or of telling?), spatial coordinates (Where am I?), and personal coordinates (Who is the entity I refer to by saying I? Who is you?).

The main character is the narrator, Herman Mussert. Mussert is a former teacher of Latin and Greek, surnamed Socrates by his pupils, who got fired because he had an affair with a married colleague (Maria Zeinstra). After this, he started writing travel guides using the pseudonym of Dr. Strabo.

In the first part of the book, the narrator tells about a day when he woke up in a hotel room in Lisbon, which was a very confusing experience (fragment 3) as he had gone to bed in his house in Amsterdam. He recognized the room because he had been there years before with his mistress, Maria Zeinstra. He further describes how he got up and wandered through Lisbon, in search of his own identity, and remembering the time he spent there with Zeinstra, besides other episodes of his life, such as his career as a teacher or as a travel guide writer.

At different times, the narrator explicitly refers to a narrating situation, using the present tense, and sometimes he also addresses a feminine you-character. However, the narrating situation remains mysterious: no information is given about when or where it takes place, and the narrator even questions the extra- or intradiegetic character of the addressee (Herman 2002: 338-341):

Explicit reflections on contextualization also occur, as in excerpt 5, where the main character is looking at a huge clock and wondering about the meaning of now:

Or excerpt 6, where the narrator is explicitly reflecting on his use of past and present tenses:

In the second part, the I-character is on a ship that departs from Lisbon, with five other men. The mysterious, feminine, addressee of the story seems to be present as well, although some doubt remains whether she is real. The other men on the ship tell her the story of their death, and then disappear. It is suggested that the addressee is a construct of the five men who momentarily take over as narrator:

In both parts of the book, past tenses tend to be used to describe the narrated situation, except when there are focalization shifts (see below). Present tenses are used to refer to the narrating situation, except at the end of the book, where the I-character is the last remaining character on the ship, and is about to tell his story. We expect the narrator to tell the story of his death, after which he would disappear, as was the case with the other men on the ship. Interestingly, at this point, a past tense is used (vertelde/told):

Thus, the past tense at the end of the book for the first time activates a deictic center that is posterior to the main narrating situation. We could say that one more metamorphosis takes place: after the metamorphosis of the main character, who woke up in another city (or probably died and was metamorphosed into a voice that remembers and narrates his memories), now the narrator – supposedly – told the story of his death and then was metamorphosed into a new narrator.

This last sentence makes clear that the novella is built upon a ‘mise en abyme’-structure, since the last sentence is also the title of the book. This has the reader wondering whether he/she is addressed by you (remember also the reflection on the extra or intradiegetic nature of you): the reader would then be the audience that the narrator needs in order to disappear and metamorphose into a new narrator. Although other interpretations are possible, it is clear that the book draws upon (rather explicit) reflections about story-telling, about the relation between an author, his narrators, and his audience, and spatiotemporal and interpersonal contextualization.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the extra-textual conditions in which the book was originally commercialized, for this by now very successful and frequently translated novella was written in 1991 as the traditional gift for the annual Dutch Week of the Book and was offered for free to all customers of Dutch bookshops. The author of the gift was also the central guest of the Week of the Book. All these elements: the circumstances in which the book was written and given to the readers for free, its mise en abyme structure, the deliberately fuzzy or multi-interpretable I and you-forms, the overall theme of metamorphosis, and the character’s search for the right temporal and spatial coordinates create a global setting where the interpreter inevitably will be concerned with the re-contextualization of the story.

In order to ease the comprehension of the different story-situations we will refer to in our analysis, we have listed them schematically in Table 1:

Table 1

The different story-situations in The Following Story

3.2. The unstable deictic center in the Spanish TT

We will now analyze two fragments in the Spanish TT which clearly show important deictic center shifts. The first fragment concerns the opening scene of the novella, which is a crucial place for contextualization (see Philippe 1998). It is indeed often the opening scene that gives crucial information about the spatiotemporal setting of the narrated story, and thus indirectly also about the situation of the deictic center. In excerpt 9 we offer a lengthy quote from the Spanish TT. The lexical spatiotemporal elements and verbal tenses that will be discussed are italicized and underlined respectively.

In the opening scene of the book, we find references to two situations. The narrating situation (S-0) is referred to in pero me desvío (but I digress) and ésta es la primera vez que intento contarlo (this is the first time I try to tell this). The present tense anchors the deictic center to this narrating situation. Although explicitly mentioned, S-0 is minimally described: no information is given yet about the narrator’s spatial or temporal situation or about the fictional addressee.

The second situation is S-1, the I-character waking up in Lisbon. To describe S-1, past tenses are used, e.g. tenía algo sobre lo que reflexionar (I had something to think about), me desperté (I woke up), or abrí los ojos (I opened my eyes). In this fragment, this happens systematically, except perhaps in the first paragraph, where an assertion in the past (esto tampoco implicaba/that did not imply) is followed by an assertion with a present tense (lamentablemente éste no es el caso/Unfortunately, this is not the case), although both sentences seem to refer to the same situation. Yet, in the group of lexical temporal indications, there is far more variation. First, a proximal este-form (esta mañana/this morning) is used, which situates the deictic center close to S-1. After this, however, the deictic center shifts away: in the next indication we find the medial-ese form (en ese momento/at that moment), and a little further even two instances of the marked distal form aquella mañana (that morning). Interestingly, the references with aquel appear after S-0 is evoked. Thus, at the beginning of the text the deictic center is placed near S-1, but when S-0 is described, the deictic center is anchored to the latter situation, and a clear distinction is drawn between S-0 (present + ésta/this) and S-1 (past + aquel/marked that). This same ‘moving away’-tendency can be noted in the spatial indications: in the first spatial reference, a proximal form is used (esta habitación/this room), but later we find esa cama extraña (that strange bed) and esa habitación de Lisboa (that room in Lisbon).

The deictic center shifts can be illustrated with a second fragment. (The I-character is sitting in a restaurant, and remembers the evening when he was there with his mistress, Maria Zeinstra. The dining room is surrounded by several mirrors.)

In this fragment there are references to situations S-2b (the adultery in Lisbon), S-1 (the day of waking up in Lisbon) and S-0 (the narrating situation). The lexical temporal references to S-2b show considerable variation: from proximal esta noche over medial esa noche to end with the marked distal aquella noche. The variable relation between the deictic center and situation S-2b is clearly a case of variable internal focalization. At the beginning of the fragment, we look through the eyes of the I-character at the moment S-2b, when he sees his mistress reflected in the mirrors. The activated deictic center is anchored to the conceptualizer of situation S-2b, and not to the narrator. After this, situation S-1 is described, with present tenses (e.g. todavía hoy la busco/I still expect to see her; no tengo ninguna necesidad/ I need no…; sigo el trayecto/I follow), which shifts the deictic center towards S-1. Now, S-2b is referred to by esa noche/that night. Then follows a remarkable fragment, where the narrator comments on his use of the present tense (el presente era una equivocación/my present tense was a slip), and emphasizes that, except for the narrating situation S-0 all other situations, including S-1, belong to the past ([el presente] sólo sirve para ahora/it applies only to now). At this point, the deictic center is clearly anchored to S-0: situations S-1 and S-2b are referred to with past tenses, and, remarkably, situation S-2b is described with the marked distal aquella noche/that night.

3.3. Translational deictic shifts between ST and TT

We will now proceed to systematically analyze the translation of the spatiotemporal expressions, and the verbal tenses. As already stated, the aim of the ST/TT comparison is to distinguish the deictic shifts in the Spanish ST that can be related to the translational interpretation process, from those which merely reflect the variable internal focalization of the Dutch ST. We will focus separately on three different deictic markers, namely lexical spatial expressions, lexical temporal expressions and verbal tenses.

3.3.1. Lexical spatial expressions

Let us start considering the translation of the spatial adverbs hier (here) and daar (there). In Table 2 we find that the adverb hier is systematically translated by the lexical equivalent aquí, except in one case, where it is left implicit. There is more variation in the translation of the adverb daar: on a total number of 13 examples, 9 are translated with the equivalent allí, 3 cases are left implicit, and there is one shift towards the proximal aquí. This shift takes place in an example where daar refers to S-1 (11).

Table 2

The translation of hier (here) and daar (there)

Now, we will consider spatial expressions that consist of an NP introduced by a demonstrative determiner (e.g. this/that room). Table 3 shows that there are four spatial markers with a proximal demonstrative in the ST. They all refer to S-1, and are all translated by the most equivalent form, i.e., the proximal form este/esta. In contrast, the spatial markers introduced by a distal demonstrative in ST show considerable variation: of the ten cases, three are translated by medial ese, one by marked aquel, and up to five cases by proximal este. The translations with este refer to situations S-1 and S-2b, which both take place in Lisbon. Aquel, on the contrary, is used to refer to S-2a, which takes place in Amsterdam.

Table 3

The translation of spatial contextualization markers, type this/that room

Thus, concerning spatial markers, we find that there are no shifts from proximal to medial or marked distal. In contrast, there are several shifts from distal to proximal, especially concerning the expressions with a demonstrative determiner. The shifts only happen when the Dutch distal refers to one of the situations that take place at the central location of the story, Lisbon. In the Dutch ST, there is already a link between the deictic center and Lisbon, which can be seen for example in the frequent use of proximals or here to refer to S-1. However, the Spanish translation reinforces this link, translating five out of ten distal demonstratives by a proximal, or by translating one case of daar (there) by aquí (here).

3.3.2. Lexical temporal expressions

The translation of the temporal adverbials nu (now) and toen (then) shows very few shifts. Nu is left implicit in three cases, but all other 31 examples are translated by the equivalent lexical items ahora or ya. Similarly, toen is almost always translated by the equivalent entonces. The only striking translation is por aquel entonces, in which entonces (then) is reinforced by the marked distal aquel. This expression emphasizes the temporal distancing of situation S-2b.

Table 4

The translation of temporal adverbs nu (now) and toen (then)

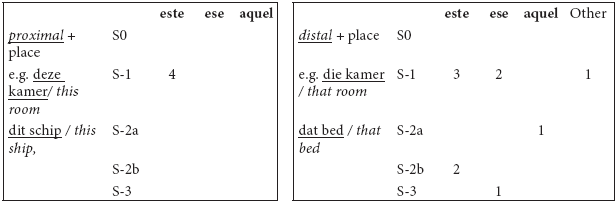

Again, the translation of the NPs introduced by a demonstrative is more varied. First, we find that ST clearly avoids the proximal form: there is only one case of temporal proximity expressed by a demonstrative (there is also only one example of the compound form vanavond –this evening–, which also refers to S-1 and is also translated with este; the compounds vanochtend, vanmiddag and vannacht [resp. this morning/afternoon/night] do not occur). This clearly contrasts with the large group of 32 temporal expressions including a distal demonstrative. Of these examples, 17 are translated by medial distal ese, five are translated with proximal este, and ten with marked distal aquel.

Table 5

The translation of demonstrative temporal contextualization markers (e.g. this/that night)

Several observations can be made. First it may be noted that three examples of aquel refer to situation S-1. This marked distancing is surprising, since the analysis of the spatial contextualization on the contrary revealed an approximation of the deictic center and S-1 (above). Interestingly, however, two of the three aquel-examples appear in the opening scene that was discussed in section 3.2. Let us compare in detail ST and TT:

In the Dutch ST we find a relatively univocal contextualization, since the deictic center is consistently distanced from S-1, by the use of past tenses, and distal demonstratives (die ochtend, dat ogenblik). The deictic center seems to be anchored to the narrator and the narrating situation S-0, which is explicitly referred to in the same fragment. In the Spanish TT, the contextualization is far more variable. At the beginning, the deictic center is approximated to S-1, with a present tense in éste no es el caso (this is not the case), as an explicitation of the implicit tense in jammer genoeg niet (unfortunately not), and also with esta mañana (this morning) as a translation of die ochtend (that morning). The first paragraph ends with the adverb toen, translated with the equivalent entonces and after this, the translator opts for the medial en ese momento (at that moment) and consistently uses the past tense to describe S-1. The explicit reference to the narrating situation S-0 constitutes a major break in the text, since it foregrounds the deictic center explicitly. This has a clear effect on the Spanish TT: although in the Dutch ST references to S-1 remain unchanged (die ochtend/that morning), in Spanish, aquella mañana now is used, and not esta or esa mañana. The use of aquel enforces a separation between S-1 and S-0, situating the deictic center nearby S-0 and moving it away from S-1.

In our view, we are witnessing here the traces of the translator’s interpretive search for the coordinates of the deictic center. First, the translator seems inclined to approximate the deictic center to the described situation S-1, more than is the case in the ST, but afterwards, when S-0 is described explicitly, the marked distals emphasize on the contrary a distancing with respect to S-1. At this stage of the analysis, it is important to note that the use of aquel to refer to S-1 is almost restricted to the opening scene of the story. In the rest of the story, ese or even proximal este are used. Distancing S-1 therefore certainly does not correspond to a deliberate strategy of the translator. The shifts in the opening scene are better interpreted as traces of the starting interpretation process, where the interpreter is trying to focus the lens of the camera.

A second observation concerning the data in Table 5 is that aquel is the most frequent demonstrative referring to situation S-2b (adultery in Lisbon): aquel is used in three out of five cases. Interestingly, in the situations of category 3 (which show no spatial or temporal overlap with S-1), aquel is less frequently used (three out of seventeen cases), although these situations may be even more distant in time than situation S-2b. In excerpt 13 aquel refers to S2-b:

The excerpt starts with a description in the past of S-1, with the main character wandering through Lisbon, and revisiting his past experiences, amongst others the adultery in the same Lisbon (S-2b). The translator uses aquellos días and en aquel entonces to refer to S-2b. This draws a distinction between the past of S-1, and the past of S-2b, distancing the latter one explicitly from the activated deictic center.

Interestingly, the temporal distancing of S-2b contrasts with the spatial approximation that we deduced from Table 3: there, we found that the two spatial references to S-2b with a distal demonstrative in Dutch are translated with a proximal demonstrative in Spanish (14).

Obviously, the temporal distancing and spatial approximation reflect exactly the relation between situations S-2b and S-1, which happen at the same place, but at different moments in time. In other words, the described situation S-1 affects the contextualization of the other situations: if a situation takes place in the same spatial setting but at a different moment in time, the TT emphasizes the spatial approximation and the temporal distancing more than the ST. In the situations which show no temporal or spatial connection with S-1 (i.e., situations of category 3), the translational shifts are far less important (Tables 3 and 5).

Nevertheless, it would be erroneous to state that this tendency is only to be found in the TT. In fact, the data show that the translation reinforces a tendency that is already present in the ST: Tables 2-5 show that, when proximals are used in the ST, this usually happens to refer to S-1. In other words, the described situation S-1 functions as a pole of attraction for the location of the deictic center in the ST, and this effect is still reinforced in the Spanish translation.

3.3.3. Past and present verbal tenses

We will now discuss the use and the translation of the verbal tenses. The present analysis is restricted to the shifts between past and present tenses, and does not focus for example on the choice between the different past tenses in Spanish to translate Dutch past tenses. It is certainly true that this choice can also have narratological implications, but these are very difficult to separate from other considerations such as aspect.

In the descriptions of situation S-0, the present tense is used systematically through the whole story. Only at the end of the book (15), there is a shift in the way of referring to S-0, for then is it presented as anterior to the deictic center. As we stated earlier, this happens very clearly in the last sentence (toen vertelde ik jou/ then I told you) where a past tense is used. This is translated equivalently in the Spanish TT (entonces te conté). However, in the Dutch ST, there is another, more subtle, reference that also describes S-0 as anterior to the deictic center. This happens in the sentence zodra ik jou mijn verhaal verteld had (as soon as I had told you my story): this sentence refers to a moment posterior to the narrating situation, but this reference point is also situated in the past, as is indicated by the use of the pluperfect tense. In the Spanish TT, in contrast, this is not the case, since the posterior relation is defined with respect to the present: tan pronto como te haya contado (as soon as I will have told you). This means that in the Spanish TT, S-0 will remain the deictic center’s anchor point for a while longer, as the translator will take more time to locate the deictic center in the very obscure posteriority to the narrating moment (see above).

In the descriptions of situation S-1, past tenses are most frequently used both in ST and TT (following a rough estimation, past tenses are used in about 90% of the verbal forms referring to S-1). However, there are also shifts in the internal focalization, and then present tenses are used. Excerpt 16 is an example of this: at the beginning we find past tenses (wist ik/I knew; intentaba/I tried). This description is followed by some memories that the I-character had in situation S-1. He remembered particularly one of the situations S-3, namely a period in his teaching career (in dat ene jaar van genade/in that one year of grace). At the end of the paragraph, situation S-1 is described again (the anchor point of the memories), but now present tenses are used (al weet ik niet waarom ik hier benalthough I still do not know why I am here). The following paragraph elaborates the description of S-1, and continues to use the present tense (doe ik/I am going; blijft/remains; is het nu/now I am).

As can be inferred from excerpt 10, the variable internal focalization in the Dutch ST is most frequently translated equivalently in the Spanish TT. However, although translational shifts are not very frequent (6 cases), they show a clear pattern: five out of six cases concern a shift from a past tense in the Dutch ST to a present tense in the Spanish TT. Only one example shows the opposite shift.

Let us consider (17), which is an illustration of the past-to-present translational shift. Excerpt 17 starts with a description of S-1 using present tenses (ik sta nu hier/I am standing here now; hangt er/is still hanging; dat mag ik ook wel eens doen/perhaps I should do the same). Up to this point, the tenses used in the Spanish TT are equivalent to the ones used in the Dutch ST. Then, an important reflection is inserted, when the narrator says that he should make time obey him (make the past run towards me like an obedient dog). After this reflection, the ST refers to S-1 with past tenses: daar kon ik het beste mee beginnen (I might as well start straight away[4]) and ik werd er een stuk groter door (it made me considerably taller). In the Spanish TT, the shift towards the past tenses also occurs, but only in the last sentence (me hizo un poco más alto): in the first case, a present is used (lo mejor es que empiece en seguida)

The fact that there are five shifts from past to present, and only one from present to past may be related to the previously observed tendency on the part of the Spanish translator to anchor the deictic center to the described situation S-1. However, this tendency does not seem to be a deliberate translational strategy, since shifts are occasional and not systematic.[5] The overall translational strategy is to render a translation as equivalent as possible. The shifts are traces of the complex interpretation process that the translator went through, not the result of a deliberate productive strategy.

An additional argument for this is that almost all translational shifts regarding the tenses, such as 17, are found at the end of the paragraph, and in fact are cases where the translation fails to immediately follow a focalization shift that occurs in the ST. Focalization shifts are an important structural and thematic feature of the Dutch ST, which may be related to the overall theme of metamorphosis: the I-character of the story is explicitly searching for the coordinates of his life, and in a similar way the first-person narrator seems to search for the coordinates of his story. One of the techniques frequently applied by Nooteboom to emphasize the mobility of the deictic center is to situate the deictic shifts within the paragraph, instead of making them coincide with major breaks in the text, such as new chapters, or new paragraphs. This is what happens in excerpt 17: we find present and past tenses to refer to S-1 within the same paragraph. Now, the majority of the translational shifts concerning tenses occur when there is such a deictic shift at the end of the paragraph in the ST. The translator then seems to have more difficulty following the deictic shift, and waits a little longer to execute it (see 17). Another illustration of this phenomenon is (18), the only case of a present-to-past translational shift. In (18), both the Dutch ST and the Spanish TT start with a reference to S-1 with a past tense (stond ik/estaba junto/I was standing) but then the Dutch ST shifts to a present tense within the same paragraph (nu sta/I am standing) and continues to use this tense in the next paragraph (draai me om/I turn around; weet/I know, …). The Spanish TT, on the contrary, waits to execute this shift until the new paragraph (me vuelvo; sé, …): the reference in the first paragraph is still using a past tense (ahora estaba/I was standing).

In excerpts 17 and 18, the internal focalization shift occurs later in the TT than in the ST. We can therefore identify some TT inertia when it comes to follow the dynamic shifts of the ST.

4. Conclusion

In the ST/TT analysis, we have described the translational deictic shifts in the Spanish translation of TFS. These shifts are clearly not the result of a deliberate overall strategy of the translator: shifts are occasional, not systematic. We believe that the translational shifts are traces of the translator’s cognitive deictic center shift, i.e., the interpreter’s effort of adopting the vantage point of the narrating voice(s) in the text. In fact, the textual translational shifts reveal that the interpretive cognitive shift is not self-evident, but rather a continuous search for the narrative coordinates, and that the contextualization of a story is indeed a re-contextualizaton. In this sense, it is interesting to observe that translational deictic shifts are especially important at the beginning of the story – the interpretive search for the coordinates being very challenging at this point –, or when the deictic shifts in the source text do not coincide with major textual breaks –making them more surprising and more difficult to appreciate.

Although the translational shifts are occasional, they show a quite coherent pattern, which may be summarized as follows: in comparison with the ST, in the TT the deictic center is more frequently anchored to the main narrated situation (the main character waking up in Lisbon), except when the narrating situation is explicitly referred to. So, for example, there are more proximal spatial adverbial expressions to refer to the main narrated situation in the TT, and almost all the shifts in the verbal tenses concern a shift from a past to a present tense referring to this situation. In other words, in the complex cognitive task of re-adopting the vantage point(s) of the ST, the translator seems to be more oriented towards the main character’s vantage point (who perceives) than to the mysterious narrator’s vantage point (who speaks). Yet, this is only true for the main narrated situation S-1. We have shown that other narrated situations are in fact more distanced from the deictic center, for example using the marked distal temporal aquel.

At first sight, this contradicts the results of Mason and Şerban (2003), who found a distancing trend in translation and explained it by the tendency to anchor the deictic center not to the character’s vantage point but to the external narrator’s. However, in our view, there is a more fundamental mechanism generalizing across the different descriptive results, namely a tendency to emphasize the most secure vantage point (see also Goethals 2008). Our main point is that this is text-dependent. The most secure vantage point may be an external narrator, or even an objective, omniscient voice, and in these cases we expect translation to favor external focalization or a more objective rendering (Jonasson 2001; Mason and Şerban 2003), but in other texts, such as TFS, it may be a deictic center involving internal focalization. We have shown that this is closely related to its thematic and structural characteristics. In TFS, the conceptualization of the narrating situation offers an important interpretive challenge: on the one hand, it is explicitly referred to as a specific situation, with a first and a you-character, and with verbal descriptions with present tenses, but on the other hand, it is very unclear where or when it takes place, or how it relates to the main narrated situation. It is even doubtful whether it really takes place in the fictional world, or whether it is a projection of another fictional narrator. In this sense, in TFS the vantage point of the narrating situation is far less secure than the vantage point of the main narrated situation. Especially the spatial coordinates of the main narrated situation (the room where the character wakes up, and the city of Lisbon) are secure coordinates.

What makes TFS so particular is that the traces of the interpreter’s deictic center shift (the differences between ST and TT) and in fact seem to reinforce the textual deictic shifts in the ST (the dynamic internal focalization), which in their turn reinforce the character’s search for the deictic coordinates of his experience. On different ontological levels, the character, the narrator and the translator are confronted with the same challenge of re-contextualization, as a form of remembering past experiences (the character), recounting memories (the narrator) or re-creating a story-telling (the translator). This exceptional matching of the different ontological levels may perhaps help to understand the exceptional position of this text with respect to previous research.

As a concluding methodological remark within Translation Studies, we hope to have shown the virtues of a close reading of individual samples in a corpus: exceptions might prove and even refine a more general rule, but this can only be shown through an in-detail analysis of the text. Corpus studies based on large collections of small samples seeking to describe general trends in translation might underexpose the individual characteristics that are needed to explain the data adequately. With respect to narratological studies on deictic center shift we hope to have shown that studies on translated texts might make a valuable contribution in this field, considering translational deictic shifts as traces of the translator’s effort to execute the more fundamental deictic center shift which every reader of a text is invited to.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

All references indicated refer to:

Nooteboom, Cees (1991): Het volgende verhaal. Amsterdam: De arbeiderspers.

Nooteboom, Cees (1992): La historia siguiente. Madrid: Siruela. Translated by Julio Grande.

Nooteboom, Cees (1993): The Following Story. London: Harvill. Translated by Ina Rilke.

The novel has also been translated into French:

Nooteboom, Cees (1991): L’histoire suivante. Arles: Actes Sud. Translated by Philippe Noble.

-

[2]

For the English translations of the excerpts, we use the translation The Following Story, by Ina Rilke (London: Harvill, 1994), adapting it, when necessary, in order to reflect the contextualization cues of the Dutch ST. Changes are indicated between brackets. For an easier reading, the longer excerpts (9 and 10) and the ones illustrating the translational analysis (11-18) are presented horizontally.

-

[3]

The bidirectional corpus analysis in Goethals (2007) showed on the one hand that the demonstrative-definite alternation can be explained by a systemic-linguistic difference between Dutch and Spanish, Dutch preferring the demonstrative expressions. On the other hand, the pronoun/definite nominal alternation was explained as a case of the universal explicitation trend in translation.

-

[4]

Unlike the English modal, the past tense in Dutch kon is necessarily interpreted as a temporal marker, and not as a modality marker.

-

[5]

Although they are not very frequent, it is possible to find translations that modify the contextualization process in a systematic way. This is for example the case in the Spanish translation of the youth novel De Kloof of Jan Terlouw, where all present tenses indicating internal focalization are systematically replaced by past tenses.

References

- Bekkering, Harry (1998): Ons leren is niets anders dan herinnering: Plato en Ovidius in Het volgende verhaal van Nooteboom. In: Marcel F. Fresco and Rudi van der Paardt, eds. Naar hoger honing? Plato en Platonisme in de Nederlandse literatuur. Groningen: Historische Uitgeverij.

- Bosseaux, Charlotte (2007): How Does it Feel? Point of View in Translation. The Case of Virginia Woolf into French. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Butt, John and Benjamin, Carmen (1994): A New Reference Grammar of Modern Spanish. London: Edward Arnold.

- Da Milano, Federica (2007): Demonstratives in parallel texts: a case study. Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung. 60(2):135-147.

- Doiz-Bienzobas, Aintzane (2003): An Analysis of English, Spanish and Basque Demonstratives in Narrative: A Matter of Viewpoint. International Journal of English Studies (IJES). 3(2):63-84.

- Genette, Gérard (2007): Discours du récit. Essai de méthode. Paris: Seuil.

- Goethals, Patrick (2007): Corpus-driven Hypothesis Generation in Translation Studies, Contrastive Linguistics and Text Linguistics. A case study of demonstratives in Spanish and Dutch parallel texts. Belgian Journal of Linguistics. 21:87-104.

- Goethals, Patrick (2008): Between semiotic linguistics and narratology: Objective grounding and similarity in essayistic translation. Linguistica Antverpiensia. 7:93-110.

- Herman, David (2002): Story Logic. Problems and Possibilities of Narrative. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Hottentot, Wim (1994): Socrates’ dood als metamorfose: Nootebooms Het volgende verhaal en de klassieken. In: Rob de Jong, Wim van Lakwijk, eds. Virtute e canoscenza. Amsterdam: Mets.

- Jonasson, Kerstin (2001): Traduction et point de vue narratif. In: Olof Eriksson, ed. Aspekter av litterär översättning från franska. Kollokvium vid Växjö universitet 11-12 maj 2000. (Svensk-franskt översättningssymposium, Växjö, 11-12 May 2000). Växjö: Växjö University Press, 69-81.

- Jonasson, Kerstin (2002): Références déictiques dans un texte narratif. Comparaison entre le français et le suédois. In: Marek Kesik, ed. Référence discursive dans les langues romanes et slaves. Actes du Colloque International de Linguistique textuelle. (Colloque International de Linguistique textuelle, Lublin, 24-30 septembre 2000). Lublin: Wydawnictwo UMCS.

- Jungbluth, Konstanze (2005): Pragmatik der Demonstrativpronomina in den iberoromanischen Sprachen. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Kleiber, Georges (2003): Adjectifs démonstratifs et point de vue. Cahiers de praxématique. 41:33-54.

- Koster, Cees (2000): From World to World. An ‘Armamentarium’ for the Study of Poetic Discourse in Translation. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Krein-Kühle, Monica (2002): Cohesion and Coherence in Technical Translation: The Case of Demonstrative Reference. Linguistica Antverpiensia. 1:41-53.

- Macías Villalobos, Cristóbal (2006): El demostrativo en Miguel Delibes. Tesis Doctoral. Spain: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. Visited on August 25th, 2009. <http://descargas.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/01338386422026950645468/017999.pdf?incr=1>.

- Mason, Ian and Şerban, Adriana (2003): Deixis as an interactive feature in literary translations from Romanian into English. Target. 15(2):269-294.

- Munday, Jeremy (2007): Style & Ideology in Translation. Latin American Writing in English. London: Routledge.

- Naaijkens, Ton (2002): De slag om Shelley en andere essays over vertalen. Nijmegen: Vantilt.

- Philippe, Gilles (1998): Les démonstratifs et le statut énonciatif des textes de fiction: l’exemple des ouvertures de roman. Langue Française. 120:51-65.

- Richardson, Bill (1998): Deictic features and the translator. In: Leo Hickey, ed. The Pragmatics of Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Ricoeur, Paul (1976): Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning. Fort Worth: The Texas Christian University Press.

- Segal, Erwin M. (1995): Narrative comprehension and the role of deictic shift theory. In: Judith Felson Duchan, Gail A. Bruder, and Lynne E. Hewitt, eds. Deixis in Narrative: A Cognitive Science Perspective. Hillsdale NL: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Şerban, Adriana (2004): Presuppositions in Literary Translation: A Corpus-Based Approach. Meta. 39(2):327-342.

- Vandelanotte, Lieven (2004): Deixis and grounding in speech and thought representation. Journal of Pragmatics. 36:489-520.

- Whittaker, Sunniva (2004): Étude contrastive des syntagmes nominaux démonstratifs dans des textes traduits du français en norvégien et des textes sources norvégiens: stratégie de traduction ou translationese? Forum, revue internationale de traduction et d’interprétation. 2(2):221-239.

- Zubin, David A. and Hewitt, Lynne E. (1995): The Deictic Center: A Theory of Deixis in Narrative. In: Judith Felson Duchan, Gail A. Bruder, and Lynne E. Hewitt, eds. Deixis in Narrative: A Cognitive Science Perspective. Hillsdale NL: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

The different story-situations in The Following Story

Table 2

The translation of hier (here) and daar (there)

Table 3

The translation of spatial contextualization markers, type this/that room

Table 4

The translation of temporal adverbs nu (now) and toen (then)

Table 5

The translation of demonstrative temporal contextualization markers (e.g. this/that night)

10.7202/009355ar

10.7202/009355ar