Résumés

Abstract

The Nunavut Department of Education is committed to creating culturally relevant Nunavut secondary schools using, as a foundation, the principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit traditional knowledge and learning), bilingualism, and inclusive schooling. This paper focuses on the voices of Nunavut secondary school educators by building upon the results of the Sivuniksamut Ilinniarniq research project, which explored multiple graduation options for Nunavut youth and was conducted by the Nunavut Department of Education in 2004. Some of the data for this research project came from a survey of secondary school educators. The open-ended responses revealed three main themes: the role of Inuit language and culture in Nunavut education; an increased role for family and community; and concerns about student engagement. An overview of the initial survey results as well as further qualitative analysis and discussion of the three main themes is provided. For current educational planning, it is necessary to understand how the majority non-Inuit secondary school educators view the Nunavut school system and the possible assumptions embedded within these views.

Résumé

Le Département de l’éducation du Nunavut s’est engagé à créer des écoles secondaires culturellement adaptées au Nunavut en se basant sur les principes du Inuit Qaujimajituqangit (le savoir traditionnel et l’apprentissage inuit), le bilinguisme et l’enseignement inclusif. Cet article expose les opinions d’enseignants du secondaire du Nunavut, tout en se fondant sur les résultats de l’étude Sivuniksamut Ilinniarniq, menée par le Département de l’éducation du Nunavut en 2004, qui explorait les multiples options de cursus pour les jeunes du Nunavut. Certaines des données du projet de recherche Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq résultent d’une enquête menée auprès des enseignants du secondaire. Ce questionnaire d’enquête ouvert permit d’identifier trois thèmes principaux préoccupant les enseignants du secondaire: le rôle de la langue et de la culture inuit dans l’enseignement au Nunavut, l’accroissement du rôle de l’implication familiale et communautaire, ainsi que des préoccupations au sujet de l’engagement des étudiants. Cet article présente un survol des premiers résultats de l’enquête ainsi qu’une étude qualitative plus approfondie et un exposé des trois principaux thèmes. La manière dont les enseignants non-Inuit du secondaire envisagent le système scolaire du Nunavut et les possibles préjugés que recouvrent leurs conceptions représentent des informations non négligeables à considérer dans les processus de planification de l’enseignement en cours.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

During the 2003 school year the Nunavut Department of Education undertook a research project named Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq in order to inform and consult the public about the Department’s ongoing agenda of curriculum reform for Nunavut secondary schools. This project[1] was developed from Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit traditional ways of knowing and learning), followed the objectives of Pinasuaqtavut,[2] and emphasized including all students within the learning environment. Its goals were to address the needs of individual learners, by building personal capacity while considering how they grow and contribute to their community.

Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq sought answers to two major questions: 1) What are the appropriate and relevant standards for Nunavut graduates? and 2) How many pathways to graduation are sustainable? Contracted researchers generated data in three ways: 1) community consultations; 2) survey of Nunavut students from kindergarten to Grade 12; and 3) a survey of secondary school educators. Approximately 10% of the survey respondents were Inuit, with only eight of the 42 Inuit respondents being classroom teachers. The survey sample reflected the composition of Nunavut secondary schools, which have very few Inuit teachers.

This paper builds upon the results of an earlier report (Aylward 2004) provided to the Nunavut Department of Education. Data have been analysed from the non-Inuit respondents to provide additional insights into the challenges facing these educators who are attempting to “work across difference” (Narayan 1988) in order to teach the majority Inuit student population. To understand how culturally relevant schooling is negotiated in Nunavut, the article also includes an examination and discussion of how non-Inuit secondary educators construct the role of Inuit language and culture as they consider the goals of Grade 12 graduation in Nunavut.

Culturally relevant schooling in Nunavut

Nunavut educational leaders are striving to embed schooling in its multiple community contexts as part of ongoing circumpolar and worldwide efforts that place Indigenous knowledge at the heart of learning (Barnhardt 2001; Battiste 2004; Bishop 2003; McCarty 2002). These efforts aim to create culturally relevant schools with respect to curricula and educational practices. Such schooling draws on research into diversity and equity education (Ladson-Billings 1995, 2001) and seeks to make educators more culturally competent. This means using the community values of their students and schools as a basis for pedagogies while at the same time raising their socio-political consciousness to avoid oversimplified and essentialist views of cultures.

As the authors of Inuuqatigiit: Curriculum from the Inuit Perspective (Northwest Territories Education, Culture and Employment 1996) explained, Inuit consider learning, evaluation, and personal improvement to be a continuous process for everyone. Traditionally, learning was facilitated by many “experts” and instruction began by first having children observe. Then with practice and given additional responsibilities children would learn new skills. Immediate and positive feedback from parents and other adults was provided in the form of praise, encouragement, and suggestions for improving their work. Children were also supported to promote persistence (ibid.). The traditional life of Inuit changed dramatically with the arrival of European explorers along with southern Canadian government agents and businesses. The rapid changes brought on by the influx of business and governmental action made it increasingly difficult to preserve the ways and means of being Inuit. The effects on Inuit ways of life by the whalers, Hudson’s Bay Company, missionaries, RCMP, military, and government officials are summed up by elder Oolooriaq Ineak: “our children today only know it is important to go to school and work [...] this has happened since there were Qallunaat [non-Inuit]” (in Gagnon and Iqaluit Elders 2002: 297).

Today, having survived the many influences of southern Canadian colonial agents, Inuit demand to be recognised as equal Indigenous members of Canada’s federation. In addition, Nunavut residents recognise the need for a system of education to be both relevant and responsive to the Nunavut context. Since the creation of the Nunavut Territory in 1999, the Nunavut Department of Education (2000) has emphasised a commitment to restructuring its schools by having bilingual education and the principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit as a foundation. The following sections provide more details of these bilingual and culture-based education initiatives.

Bilingual education

The Nunavut Department of Education began rewriting the Education Act and reforming its bilingual education policy in its first mandate. It commissioned two research projects—Qulliq Quvvariarlugu (Corson 2000) and Aajjiqatigiingniq (Martin 2000)—to investigate the status of the languages-of-instruction policies and practices in Nunavut schools. In both cases southern Canadian academic researchers partnered with Inuit and non-Inuit northern research assistants to map out the options for bilingual education that would meet the diverse needs of the three Nunavut regions. The languages of instruction research reports informed the Government of Nunavut that it had inherited a weak bilingual education model that failed to respond to the present and future human development needs of Nunavut.

Specifically, Martin (2000) clearly indicated that the weak model of bilingual education, presently in place, had profound influence on the grade level achievement and failure of Inuit students. In addition, the research showed that this model did not respect the linguistic human rights of students and communities. Findings also indicated that Inuit languages were practically absent from the secondary school domain in Nunavut and that a pattern of “subtractive bilingualism” in both fluency and literacy was operating. Among students, high English fluency and literacy correlated with low scores in Inuktitut. As Nieto (2002) describes, “early exit” transitional, bilingual education programs (such as those in Nunavut) use the native language as a bridge to the dominant language Once English is learned, the bridge is burned. These research results pushed the Government of Nunavut to revise its Bilingual Education Strategy and promote community-based educational models that ensure the maintenance of Inuit languages as well as English (George 2004). Further efforts to preserve the languages and culture of Nunavut led to the passing of the Inuit Language Protection Act in Nunavut in 2008. This act aims to protect Inuit languages by guaranteeing both public and private-business services in an Inuit language.

The role of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit in Nunavut schooling

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is an Inuit epistemology that cannot genuinely make the translation in all its richness from Inuktitut to English. IQ (as nicknamed in English) is holistic and was first defined in written public documents by Louis Tapardjuk of the Nunavut Social Development Council (NSDC) as “all aspects of traditional Inuit culture including its values, world-view, language, social organisation, knowledge, life skills, perceptions, and expectations. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is as much a way of life as it is sets of information” (NSDC 1998: 2).

Policy makers and educators in Nunavut think that it is impossible to base Nunavut schooling on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit principles while leaving the system of education as is. With a view to a more collaborative relationship, these principles are calls to develop shared leadership models and strong relationships within schools. Educators and policy planners are thus re-examining administrative structures, disciplinary measures, and grade groupings. Other principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit call for efforts to support and maintain a healthy environment of personal responsibility and respectful behaviour (NDSC 2000). Educators need to think about how schooling can strengthen and extend the interdependent nature of this relationship with the environment.

Finally, Pilimmaksarniq (‘knowledge acquisition, skill development, capacity building’) is at the heart of conversations on cultural relevance and Nunavut secondary school options. One of its objectives is a re-writing of the kindergarten to Grade 12 curriculum with emphasis on both cultural relevance and academic excellence (Government of Nunavut 1999; 2004). Inuit ways of knowing and doing are thus recognised as an academically legitimate frame of reference. To this end, it is necessary to survey secondary school educators on the graduation options and programs now available to Nunavut youth.

Secondary school educators’ views of Nunavut schooling

In the Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq research project, a questionnaire was sent to all Nunavut educators who worked with students in Grades 7-12 in the following positions: Assistant Principals; Classroom Assistants, Classroom Teachers; Consultants, Principals, Executive Directors; Elders; Guidance Counsellors; Language/ Cultural Specialists; Program/Student Support teachers; School Community Counsellors; and Student Support Assistants. The questionnaire was based on two previous surveys from the Nunavut Boards of Education (1994) and the Federation of Nunavut Teachers (2001). The new survey included closed and open-ended questions. In the closed-ended questions respondents were asked to rank a series of statements on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree.

The survey used lists of discrete factors such as interpersonal skills, creative problem solving, and personal coping. In each closed-ended question the respondent could fill in any additional categories that he or she felt appropriate and rate them on the same scale. For example one question read: “Please circle your position on the personal barriers that are preventing your students from graduating. Circle only those that you feel apply and leave others blank (1 = low, 5 = high).” Respondents could also provide comments at the end of every question. The survey contained: a series of questions on the respondent’s age, gender, ethnicity, work experience and job; seven closed-ended questions; and an open-ended question at the end of the survey. The open-ended question asked secondary educators to write about “programs, activities or courses in your school that are helping to keep students in school.” Educators were asked for information about:

Strengths of current and past students who were struggling in school and at risk of not graduating

Personal barriers of current and past students who were struggling in school and at risk of not graduating

System-wide barriers affecting students’ graduation options

Barriers to teacher effectiveness

Course areas for strengthening graduation options that fit student needs and the needs of their communities

Resources needed to change or strengthen course areas

Suggestions to improve graduation options

Programs, activities, and courses that are helping keep students in school

An estimated 445 educators worked with Nunavut secondary school students in the 2002-2003 school year. The survey had a response rate of 48% over a total of 213 completed surveys. The sample was statistically reliable at the 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error. Table 1 identifies the survey population and response rates.

Table 1

Nunavut secondary school educators surveyed and their response rates.

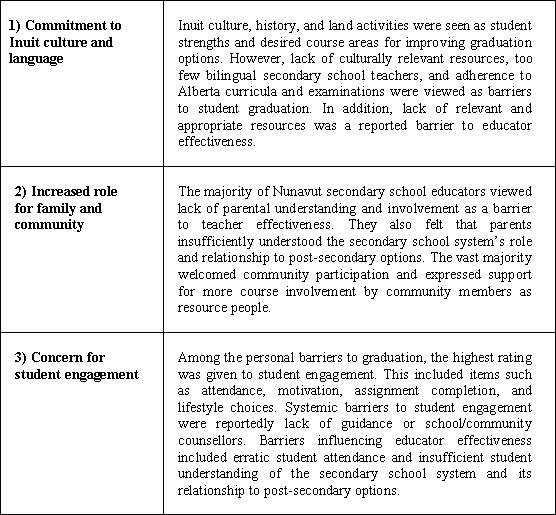

An initial quantitative analysis by Guy (2003) found three main themes from the data (Table 2). As stated by Guy (2003: 33): “The best way to understand what educators said is to read the entire report. However, certain themes did emerge in this research that show that Nunavut’s secondary educators have (and in some cases, share) some overriding concerns, opinions and ideas.” Many of the themes were comparable to previous results from surveys of Nunavut educators (Federation of Nunavut Teachers 2001; O’Donaghue 1998). There are many encouraging signs in the secondary school survey data, most notably the recognition of the importance of Inuit language and culture to improving school success. However, further analysis of the majority non-Inuit respondents’ open-ended comments provides additional information on their assumptions about Nunavut schooling. Each of the three themes can be considered factors that contribute to the cultural relevance of Nunavut schooling. It is therefore worthwhile to analyse the possible meanings of responses from the majority non-Inuit secondary school educators.

I completed a qualitative analysis of the open-ended survey responses through an inductive category process (see Maykut and Morehouse 1994) that began by narrowing the data corpus to those comments that explicitly spoke to the role of Inuit language and culture in Nunavut schooling and visions for graduation options. Following on from the initial analysis (Aylward 2004), the current analysis focused on two questions. 1) How does this group of educators express their commitment to Inuit language and culture, their concerns about student engagement, and their views on the role of family and community in Nunavut schooling? 2) Which recurring themes and issues identified by this group relate to the role of Inuit languages and culture in Nunavut secondary schooling, student engagement, and family/community involvement? The themes and issues were identified through key words that appeared in respondents’ statements and their relationship to the current literature as well as my previous educational research within the Nunavut context (Aylward 2006). I am a non-Inuit educator who lived and worked in Nunavut for eight years and therefore bring that perspective to the analysis. The issues that emerged from the data are discussed below within the categories of the original research report.

Table 2

Main themes from Nunavut secondary school educators survey (based on Guy 2003).

Commitment to Inuit language and culture: Educational standards and teacher experiences

How Nunavut secondary school educators interpret educational standards within the Nunavut school context is vital to understanding implementation of culturally relevant schooling. Many survey comments expressed concerns about how Article 23 of the Nunavut Land Claims Act (which allows equivalencies for job competitions with a view to increasing Inuit representation in the public sector) works against high school completion. Students drop out of school to follow potential career paths. Educators felt that a unique Grade 12 credential might stem the tide of exiting students: “Maybe a special Nunavut Gr.12 certificate could be given that would be accepted by anyone in Nunavut only” (S-33).[3] Such a comment indicates that some educators subscribe to the view that a “made in Nunavut Grade 12” might need to be a “recognised only in Nunavut Grade 12” in order to raise the graduation rate and to improve access to employment. Some educators proposed a two-stream system based on whether or not students met the Alberta Departmental Exam requirements, stating that programs could be “academic” and “something else.”

Secondary school educators also viewed Nunavut students’ strengths and possible life trajectories in relation to purportedly static and universal academic standards. Secondary school teachers were wary of other possible arrangements that would not meet the accepted Canadian national standard for a Grade 12 diploma: “My concern is that the minimum standards of the skills, knowledge and attitudes one must attain to graduate from high school may differ quite a bit from those set by the rest of Canada. If the minimum standards were changed so as to be equal in value, as judged by Western Society, but different, that would be acceptable” (S-45). “We need to stop ‘watering down’ programs for students so they can get an education that is equivalent to the south” (S-152). The responses may reflect a belief that learning must be formal, school-based, and sequential. “Equal” and “different” are potentially contradictory concepts in the Nunavut educational context. Many responses suggested that Inuit cultural competence and academic achievement in present-day schools are incompatible or mutually exclusive. Inclusion of traditional knowledge and/or efforts to make Nunavut curricula more culturally responsive and relevant was often equated with non-standard education.

Some educators commented that many students viewed school as a process of “becoming non-Inuit.” Douglas (1998) explored these tensions between “life” and “school,” comparing the socialisation processes of one Nunavut community to the socialisation processes of the school and found significantly different worldviews at play. Repeated references were made by secondary school educators to the lack of support for Inuit cultural studies within the academic and non-academic program. Comparisons were made to other curriculum subjects in order to demonstrate how aspects of Inuit language and cultural programs were still largely considered “extras” of Nunavut schooling and at present could not meet the educational standards required for better graduation outcomes.

It is important to consider teacher experiences in translating their commitment to Inuit language and culture into practice. Educators reported the struggles they faced when trying to implement school programs that they felt to be often ineffective even if appropriately respectful. Professional isolation and lack of resources were of great concern: “We’re all in this alone” (S-122); “I have so many creative talents and little opportunity to show them” (S-190). Some commented on how personally and professionally unprepared they were to do the work required of them. The new teachers pointed to factors that undermine their performance, such as loss of energy and enthusiasm, lack of committed leadership in schools, absence of orientation activities, and an inability to respond to multi-level, multi-course classroom arrangements.

Increased role for family and community: Parental support for education

Educators reported a lack of parental partnership in their attempts to uphold community school practices and policies: “Parents need to encourage students more rather than make excuses—there are no goals at home to enhance the work done at school” (S-32). There were multiple prescriptive suggestions as to what needed to be done to improve parental involvement as in the following: “[Parents should] enforce sleep curfews, provide food, and provide a nurturing violence-free home, environment and appropriate discipline” (S-112). Misunderstandings and mis-readings of Inuit child-rearing practices as well as misinformation about how children develop responsibility in Inuit culture may contribute to how secondary school educators frame the parental role in education. For example, there may be food in the students’ homes but not the established meal times that are familiar to middle-class, southern Canadian families.

As demonstrated in the quotes above, many non-Inuit educators seem to believe Inuit parents and home environments were to blame for low academic achievement. This finding echoes that of Fuzessy (2003) in his study of teacher role definitions in Nunavik. Despite ample data on the significant social crises facing many Nunavut communities, secondary school educators’ responses indicated little recognition or awareness of substantial systemic barriers within educational institutions and the role educators can play in erecting them. This view is not unique to Nunavut educators. Often teachers’ experiences with formal education and their institutional role can limit more critical explorations of success and achievement in most educational settings.

Concern for student engagement: Biculturalism and the language gap

The respondents commented on the clash of the “two worlds” or bicultural life of Nunavut students as a possible explanation for the lack of student engagement with schooling, as in the following example: “Lifestyle does not fit education” (S-99). Biculturalism is defined by Darder (1991: 48) as a “process wherein individuals learn to function in two distinct sociocultural environments: their primary culture, and that of the dominant mainstream culture of the society in which they live.” This kind of bicultural orientation separates life from school and establishes a permanent division between formal schooling (i.e., mostly within school buildings) and traditional, culturally relevant learning (i.e., in the community). As one educator commented: “I don’t want to see us ‘dumb down’ the academic program so that we can get kids, whose talents lie in other areas, through the system […]. We need to give the child who spends half the year on the land the right to graduate with a ‘traditional skills’ diploma” (S-75).

Strong adherence to the tenets of biculturalism might help non-Inuit secondary school educators explain why there are “problems with students” and why academic achievement for some Inuit students remains elusive. Though helpful in the cultural awareness stage of education planning, biculturalism and metaphors of “two worlds” severely restrict the students’ perceived options and potentially contribute to further marginalisation (Henze and Vanett 1993), as exemplified in the following comments: “[…] the majority of our students are not interested in post-secondary school. Culturally relevant programs and life skills would help these students be more successful in life” (S-98). Within these comments is the assumption that Nunavut students, as a whole, are not interested in post-secondary education and an assertion that culturally relevant programs and success in post-secondary schooling represent distinctly different pathways.

Respondents also expressed concerns about the perceived “language gap.” The most abundant comments on students’ needs concerned the language gap between the students’ current levels of English literacy and the perceived necessary level of English literacy for their grade level: “The system will never be functional as long as we are making bilingual illiterate people” (S-145). The language of instruction in Nunavut secondary schools is English with Inuit language taught as an individual course credit in most communities. Many Inuit secondary school students have not had instruction in an Inuit language since elementary school. Secondary school educators criticised the bilingual language programs and stated clearly that English proficiency was a graduation requirement: “If students are not strong in English they have virtually zero chance of graduating” (S-36). More and better quality English-language instruction was considered the remedy. Students were often discussed in terms of their “lack of English; lack of southern knowledge.”

Discussion and conclusion

One might ask “where is the good news?” Many strengths have been richly detailed with respect to the Nunavut school system and its educators in the full Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq report as well as in previous Nunavut education studies (Aylward 2006; Berger 2008; Tompkins 1998). This article provides analysis and discussion that might contribute to the ongoing critical conversation about educational change by Indigenous scholars, leaders, and their allies since the imposition of formal schooling on Canada’s Aboriginal peoples in the early to mid-1900s. With respect to northern Canadian schooling and specifically the Arctic regions, Inuk leader Jose Kusugak (1979: 4), bluntly said, “the current [education] system is just not working.” It is necessary to examine the significant issues raised by non-Inuit secondary school educators in Nunavut in relation to the role of Inuit language and culture, the role of family and community, and concerns about student engagement, as these issues shed much light on the broader issue of cultural relevance. Indeed, the educators outline clearly what is not working.

It is impossible to engage in a dialogue about Indigenous language, cultures, curricula, and educational standards without in-depth consideration of cultural difference. In this, a common response is a “both worlds” bicultural orientation. Such an approach may lead to Inuit worldviews being more highly valued in curricula and to efforts to critique the foundations of the Eurocentric core. Yet, without recognition of the dominant/subordinate power relations inherent in bicultural education, a “both worlds” approach would remain a mythical ideal. Views of multicultural and bicultural education embedded within the concepts of cultural diversity can be deeply problematic in that they reinforce cultural polarities. Even a critical multicultural approach may not take us beyond the powerful influences of academic standards and excellence, thus relegating any Indigenous knowledges or languages to the superficial level of “add-ons” to the “real” curriculum.

In using the bicultural metaphors and dreams of “walking in two worlds,” we may sometimes offer simple answers to very complex questions. In this study, such language may reveal a naïve understanding among educators, who may thus be less able to support the dynamic cultural identities of the students and Inuit-oriented Nunavut schooling. There do exist well documented settings of successful bilingual and bicultural education within Aboriginal communities that have paid attention to the power relations inherent in such a complex negotiation (Johnston 1998; Watahomigie and McCarty 1994). The transformative work in New Zealand within the Maori education community also provides profound insights into the relationships between culture, power, and education (Bishop 2003; Bishop and Glynn 1999). Most applicable to Nunavut would be the recent work on “Inuit Holistic Lifelong Learning” completed by the Canadian Council on Learning (2007), which proposes a dynamic learning model, weaving formal and informal learning with the concepts of walking in two worlds.

Considerations of cultural difference also influence how educators assess student engagement and family involvement. Nakata (2002) maintains that much of the focus of cultural difference, within Indigenous education contexts, has been on constructing the “Aboriginal student” category rather than on the systemic and structural nature of education. Nakata believes that the anthropological definitions of cultural difference have become dominant within Indigenous education contexts, positioning Indigenous students as having learning problems due to their cultural difference. Constructions of “difference as deficit” have promoted the fixing of “broken” students and “broken” homes as a major educational goal within Aboriginal education, thus contributing to constructions of the “unhealthy Native” individual (Jester 2002). This type of thinking is reflected in the views expressed by non-Inuit educators in this study. Although the educators’ gaze is sympathetic, their biases will discourage them from seeing themselves as playing an active role in changing schooling, from taking responsibility for their own actions, and from establishing respectful relations with Inuit parents.

Finally, the views presented in this paper are a reminder to all those involved in the teaching profession about the demanding nature of the job, especially when working within an intercultural learning environment, as in Northern Canada. These demands, especially those on non-Aboriginal educators, were first detailed by the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly Special Committee on Education (1982). Harper’s (2000a; 2000b; 2004) ongoing studies of non-Aboriginal teachers working in northern Canadian Aboriginal communities suggests that there may be “no way” to prepare for the particular yet unpredictable, community-specific intercultural demands of Nunavut schooling. These challenges were also highlighted in the Nunavut-specific research by O’Donaghue (1998) as well as by Berger and Epp (2007). We should not ignore the professional and personal demands of the workplaces of Nunavut educators, as they are key to creating a positive learning environment and planning educational change.

The challenge of planning appropriate and relevant standards for Nunavut secondary school students while establishing multiple, sustainable graduation pathways is intertwined with the need for more complex understandings of culturally relevant, community-based education. Aboriginal scholars and those who work closely within Aboriginal communities have stated how education remains both a causal link and a source of hopeful solutions to many challenges and barriers facing Aboriginal peoples today (Battiste 2004; Hookimaw-Witt 1998). However, initiatives aimed at infusing Indigenous knowledge into public education around the globe are in collision with the forces of education standardisation and accountability, which are consistently and purportedly being deployed to address issues of equality (May and Aikman 2003; McCarty 2003). How “different” or “culturally relevant” can Nunavut schools become when they are constantly battling the external forces of standardisation and homogenisation? Based on the findings of SivuniksamutIlliniarniq study, Oakes’s (1988: 41) question about Canadian Arctic education appears to be still valid for secondary school educators of Nunavut today: “If the primary purpose of education is to provide students with modern job related skills, do culture courses have a place in present day classrooms?” Another question must be asked: What are the possibilities for “exemplary Indigenous education” within the contradictory lived experiences of Western educational theories and practices? (Berger 2008; Graveline 2001, 2002).

With respect to the views of these educators, we must remember that Nunavut schooling is a deeply intercultural process for all. The cultural crossings are unique to each participant’s perspective. Inuit and non-Inuit educators and students must stretch their approaches in ways unfamiliar to themselves, and in ways that cause great discomfort and, in some cases, tremendous stress. In order for a public school system to meet both its territorial and national learning goals, educators will need consistent and comprehensive professional support. This has implications for teacher recruiting and learning on the job, as the opportunities for unique professional and personal growth can be an attractive aspect of teaching in Nunavut.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the Nunavut Department of Education’s leadership in the Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq consultations and resulting research reports. I was contracted to combine the data and analysis generated in the three parts of the Sivuniksamut project into one final report for consideration by the Nunavut Department of Education. I would also like to thank the Études/Inuit/Studies reviewers for their helpful and substantive feedback on this manuscript.

Notes

References

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2004 Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq, research report prepared for the Curriculum and School Services, Arviat, Nunavut Department of Education.

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2006 The Role of Inuit Language and Culture in Nunavut Schooling: Discourses of the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Conversation, doctoral dissertation, University of South Australia, Adelaide.

- BATTISTE, Marie, 2004 Animating sites of postcolonial education: Indigenous knowledge and the humanities, plenary address at the Canadian Society for the Study of Education 32nd Annual Conference, Winnipeg, May 29, 2004.

- BARNHARDT, Carol, 2001 A history of schooling for Alaska Native People, Journal of American Indian Education, 40(1): 1-30.

- BERGER, Paul, 2008 Inuit Visions for Schooling in one Nunavut Community, doctoral dissertation, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay.

- BERGER, Paul and Juanita R. EPP, 2007 “There’s no book and there’s no guide”: The expressed needs of Qallunaat educators in Nunavut, Brock Education, 16(2): 44-56.

- BISHOP, Russell, 2003 Changing power relations in education: Kaupapa Maori messages for ‘mainstream’ education in Aotearoa/New Zealand, Comparative Education, 30(2): 221-238.

- BISHOP, Russell and Ted GLYNN, 1999 Culture counts: Changing power relations in education, New York, Zed Books.

- CANADIAN COUNCIL ON LEARNING, 2007 Redefining how success is measured in First Nations, Inuit and Métis learning, Report on learning in Canada, 2007, Ottawa, Canadian Council on Learning (online at www.ccl-cca.ca/pdfs/RedefiningSuccess/Redefining_How_Success_Is_Measured_EN.pdf).

- CORSON, David, 2000 Qulliq Quvvariarlugu, Iqaluit, Government of Nunavut.

- DARDER, Antonia, 1991 Culture and power in the classroom: A critical foundation for bicultural education, Toronto, OISE Press.

- DOUGLAS, Anne, 1998 “There's life and then there's school”: School and community as contradictory contexts for Inuit self/knowledge, doctoral dissertation, McGill University, Montreal.

- FEDERATION OF NUNAVUT TEACHERS, 2001 Nunavut Professional Improvement Committee Staff Development Questionnaire Draft Report, Iqaluit, Federation of Nunavut Teachers.

- GAGNON, Mélanie and Iqaluit Elders, 2002 Inuit recollections on the military presence in Iqaluit, Iqaluit, Nunavut Arctic College, Memory and History, 2.

- GEORGE, Jane, 2004 Inuit teachers key to Inuktitut curriculum: Bilingual education strategy depends on teacher training program, Nunatsiaq News, December 10 (online at www.nunatsiaq.com).

- GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT, 1999 The Bathurst Mandate: Pinasuaqtavut: That Which We’ve Set Out To Do: Our Hopes and Plans for Nunavut, Iqaluit, Government of Nunavut.

- GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT, 2004 Pinasuaqtavut: 2004-2009. Our Commitment to Building Nunavut’s Future, Iqaluit, Government of Nunavut.

- GRAVELINE, Fyre Jean, 2001 Imagine my surprise: Smudge teaches wholistic lessons, Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(1): 6-19.

- GRAVELINE, Fyre Jean, 2002 Teaching tradition teaches us, Canadian Journal of Native Education, 26(1): 11-29.

- GUY, Barbara, 2003 Sivuniksamut Illiniarniq: Secondary Educators’ Survey Results, Research report prepared for the Curriculum and School Services, Arviat, Nunavut Department of Education.

- HARPER, Helen, 2000a White Women Teaching in the North: Problematic Identity on the Shores of Hudson’s Bay, in N. Rodriguez and L. Villaverde (eds), Dismantling White Privilege: Pedagogy, Politics and Whiteness, New York, Peter Lang Press: 127-141.

- HARPER, Helen, 2000b “There is no way to prepare for this”: Teaching in First Nations schools in Northern Ontario—Issues and Concerns, Canadian Journal of Native Education, 24(2): 144-157.

- HARPER, Helen, 2004 Nomads, pilgrims, tourists: women teachers in the Canadian north, Gender and Education, 16 (2): 209-224.

- HENZE, Rosemary C. and Lauren VANETT, 1993 To walk in two worlds—or more? Challenging a common metaphor of Native education, Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 24(2): 116-134.

- HOOKIMAW-WITT, Jacqueline, 1998 Any changes since residential school?, Canadian Journal of Native Education, 22(1): 159-171.

- JESTER, Timothy E., 2002 Healing the unhealthy Native? Encounters with standards-based education in rural Alaska, Journal of American Indian Education, 41(3): 1-21.

- JOHNSTON, Patricia M.G., 1998 He Ao Rereke: Education policy and Maori under-achievement: Mechanisms of power and difference, doctoral dissertation, University of Auckland. Auckland,

- KUSUGAK, Jose, 1979 The Inuit Educational Concept, Ajurnarmat, 4: 32-37.

- LADSON-BILLINGS, Gloria, 1995 Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy, American Educational Research Journal, 32(3): 465-491.

- LADSON-BILLINGS, Gloria, 2001 Crossing over to Canaan: The journey of new teachers in diverse classrooms, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

- MARTIN, Ian, 2000 Aajiiqatigiingniq: Languages of instruction research report, submitted to the Government of Nunavut, Iqaluit.

- MAY, Stephen and Sheila AIKMAN, 2003 Indigenous education: Addressing current issues and developments, Comparative Education, 39(2): 139-145.

- MAYKUT, Pamela and Richard MOREHOUSE, 1994 Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophical and Practical Guide, Washington, Falmer Press.

- McCARTY, Teresa L., 2002 A place to be Navajo: Rough rock and the struggle for self-determination in Indigenous schooling, New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- McCARTY, Teresa L., 2003 Revitalising Indigenous languages in homogenising times, Comparative Education, 39(2): 147-163.

- NAKATA, Martin, 2002 Indigenous knowledge and the cultural interface: Underlying issues at the intersection of knowledge and information systems, paper presented at the 68th International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) Council and General Conference, August 18-24, Glasgow.

- NARAYAN, Uma, 1988 Working together across difference: Some considerations on emotions and political practice, Hypatia, 3(2): 31-48.

- NIETO, Sonia, 2002 Language, culture and teaching: Critical perspectives for a new century, Mahwah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- NORTHWEST TERRITORIES EDUCATION, CULTURE AND EMPLOYMENT, 1996 Inuuqatigiit: The Curriculum from the Inuit Perspective, Yellowknife, Department of Education, Culture and Employment.

- NORTHWEST TERRITORIES LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION, 1982 Learning: Traditions and change in the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, Department of Education, Culture and Employment.

- NUNAVUT BOARDS OF EDUCATION, 1994 Pauqatigiit Staff Development Questionnaire, Iqaluit, Nunavut Boards of Education.

- NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2000 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: A new philosophy for education in Nunavut, Arviat, Curriculum Services.

- NUNAVUT SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL (NSDC), 1998 Report of the Nunavut traditional knowledge conference, Igloolik, March 20-24, Igloolik, Nunavut Social Development Council.

- NUNAVUT SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL (NSDC), 2000 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit as a planning and organizational development tool, Igloolik, Nunavut Social Development Council.

- OAKES, Jill E., 1988 Culture: From the igloo to the classroom, Journal of Native Studies, 15: 41-48.

- O’DONOGHUE, Fiona, 1998 The hunger for professional learning in Nunavut schools, doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto.

- TOMPKINS, Joanne M., 1998 Teaching in a cold and windy place: Change in an Inuit school, Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

- WATAHOMIGIE, Lucille J. and Teresa L. McCARTY, 1994 Bilingual/bicultural education at Peach Springs: A Hualapai way of schooling, Peabody Journal of Education, 69(2): 26-42.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Nunavut secondary school educators surveyed and their response rates.

Table 2

Main themes from Nunavut secondary school educators survey (based on Guy 2003).