Résumés

Abstract

Although anxiety has been documented as an important variable in both interpretation performance and second language acquisition, there has been virtually no research on the interconnections between the anxiety reactions induced by these two cross-linguistic / cultural endeavors. A review of the literature on anxiety and interpretation performance finds that most of the existing studies have treated the anxiety induced by interpretation as a transfer of other general types of anxieties, such as trait anxiety, without considering the probable role of second language anxiety in interpretation performance. In order to determine the role of foreign language anxiety in 213 Chinese-English interpretation students’ learning outcomes, which were indexed by the participants’ mid-term exam scores and semester grades, this study employed Spielberger’s (1983) Trait Anxiety Inventory to measure the students’ trait anxiety, while utilizing Horwitz, Horwitz et al.’s (1986) Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) to measure the participants’ foreign language anxiety. Results of correlation analyses showed that a) trait anxiety was not related to either mid-term exam scores or semester grades, b) foreign language anxiety was significantly and negatively associated with both outcome measures, c) after controlling for the effect of trait anxiety, the relationship between foreign language anxiety and interpretation learning outcomes remained significant, and d) a vast majority of the FLCAS items had significant and negative associations with both outcome measures. Implications for developing a theory of and a measurement instrument for interpretation learning anxiety are suggested.

Keywords:

- anxiety,

- theory,

- measurement instrument,

- interpretation,

- achievement

Résumé

Bien que le rôle déterminant de l’anxiété ait été démontré autant en situation d’interprétation que dans le cadre de l’acquisition d’une langue seconde (L2), peu de travaux ont été menés sur les liens pouvant exister entre les formes d’anxiété respectivement induites par ces deux situations, toutes deux translinguistiques et transculturelles. Les principales études menées jusqu’à présent sur l’anxiété en situation d’interprétation tendent à considérer l’anxiété d’un interprète comme l’expression d’autres formes d’anxiété, par exemple l’anxiété constitutive. Elles ne tiennent pas compte de la probable influence de l’anxiété due à l’utilisation d’une langue étrangère en situation d’interprétation. Le présent article fait état d’une étude qui visait à déterminer l’influence de l’anxiété liée à l’utilisation d’une langue étrangère sur les résultats d’apprentissage obtenus par 213 étudiants en interprétation chinois-anglais. Les résultats examinés étaient les résultats de mi-session et les résultats finaux. Deux échelles ont été employées, celle de Spielberger (1983 ; State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), pour évaluer l’anxiété caractérielle, et celle de Horwitz, Horwitz et al. (1986 ; Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale, FLCAS), pour évaluer l’anxiété liée à l’utilisation d’une langue étrangère. Les analyses de corrélation ont montré : a) qu’il n’y avait aucune corrélation entre l’anxiété caractérielle et les résultats d’apprentissage examinés ; b) qu’il existait une corrélation négative significative entre l’anxiété due à l’utilisation d’une langue étrangère et les résultats d’apprentissage ; c) qu’une fois l’effet d’anxiété de trait neutralisé, la corrélation entre l’anxiété due à l’utilisation d’une langue étrangère et les résultats d’apprentissage était toujours significative ; d) que la grande majorité des items de l’échelle FLCAS sont corrélés négativement et de façon significative avec les résultats d’apprentissage examinés. En conclusion, les implications théoriques et expérimentales (instrument de mesure) relatives à l’anxiété liée à l’apprentissage de l’interprétation sont abordées.

Mots-clés :

- anxiété,

- théorie,

- instrument de mesure,

- interprétation,

- performance

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Researchers have long been interested in the role of anxiety or stress in interpretation performance because it has the potential to interfere with the task of interpretation (Alexieva 1997; Cooper, Davis et al. 1982; Coughlin 1988; Gile 1995; Herbert 1952; Keiser 1977; Klonowicz 1991, 1994; Moser-Mercer, Künzli et al. 1998; Moser-Mercer 2003; Roland 1982; Seleskovitch 1978). Although anxiety is one of the most widely discussed affective variables in the literature on interpretation, there has been no consensus on its definition and measurement. As pointed out by Chiang (2009), interpretation stress and interpretation anxiety are often used interchangeably in interpretation literature; here, unless a distinction is intended, interpretation anxiety is used to highlight the connection to second language (L2)[1] anxiety research. In most of the studies on interpretation anxiety, the anxiety associated with interpretation has been treated as a transfer of other more general types of anxiety and measured by either trait anxiety scales, or state anxiety scales, or a combination of both trait and state anxiety scales (e.g., Gerver 1974; Jiménez Ivars and Pinazo 2001; Kurz 1997; Riccardi, Marinuzzi et al. 1998). Recent studies have attempted to assess the anxiety induced by interpretation through more specific stressors, such as difficult source texts and fear of public speaking (e.g., AIIC 2002; Jiménez Ivars and Pinazo 2001). While these studies have advanced our knowledge about the anxiety associated with interpretation, the advancement has been limited. At best these studies have provided only a partial account about the anxiety associated with interpretation. In particular, existing studies have not only yielded discrepant findings regarding the relationship of anxiety to interpretation performance, but also disregarded the influence of L2 anxiety on interpreters’ performance against the fact that interpretation has usually involved one or even two L2s. These problems with the conceptual ambiguity and measurement instrument specificity regarding the construct of interpretation anxiety must first be overcome before the antecedents, correlates and consequences of interpretation anxiety can be fully established.

In order to further our knowledge about the exact nature of interpretation anxiety, this study followed up on Chiang’s (2009) study on foreign language (FL) anxiety in student interpreters and investigated the relationship between trait anxiety and FL anxiety as well as their respective associations with student interpreters’ learning outcomes in interpretation classes. It is hoped that the findings of this study will not only shed new light on the nature of interpretation anxiety, but also help develop a more refined theory and measurement instrument for the construct of interpretation anxiety than those we currently have. In this study, FL anxiety is defined as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” (Horwitz, Horwitz et al. 1986: 31), and is measured by Horwitz, Horwitz et al.’s (1986) Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS); trait anxiety is defined as a relatively stable personality trait and is operationalized by Spielberger’s (1983) Trait Anxiety Inventory. Four research questions guided this study:

Is student interpreters’ trait anxiety related to their FL anxiety?

Is student interpreters’ trait anxiety related to their learning outcomes in interpretation courses?

Is student interpreters’ FL anxiety related to their learning outcomes in interpretation courses?

Are the individual items of the FLCAS as rated by student interpreters related to their learning outcomes in interpretation courses?

2. Method

Reported below is the research method for the present study, including participants, instruments, and procedures of data collection and analysis.

2.1. Participants

The participants were 213 interpretation students from six higher-education institutions in Taiwan. At the time of the survey, they were taking Chinese-English interpretation[2] at two universities in northern Taiwan, two universities in central Taiwan, and one university in southern Taiwan. Of the participants, 165 were women (78%) and 48 were men (22%). They ranged from 19 to 22 years old, and had learned English as a foreign language (EFL) as an academic subject at school for at least six years. These students were recruited because they were both interpretation students and EFL students.

2.2. Instruments

Three instruments were used, including a Background Information Questionnaire (BIQ), Spielberger’s (1983) Trait Anxiety Inventory (TAI), and Horwitz, Horwitz et al.’s (1986) Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS). The BIQ was designed to collect important demographic information about the participants, such as gender. The TAI is a 20-item self-report scale developed to measure a person’s general level of anxiety independent of any anxiety-provoking event. Spielberger (1983) reported that the TAI had Cronbach alpha coefficients ranging from .93 to .95. In the present study, the TAI had an internal consistency of .91, using Cronbach’s alpha. The FLCAS measures a student’s anxiety unique to the situation of learning a foreign language based on a 33-item self-report questionnaire. Horwitz (1986) reported that the FLCAS had a satisfactory level of internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha = .93 (n=108), and test-retest reliability over a period of eight weeks, with r = .83 (n= 78, p < .01). The validity and reliability of the FLCAS have been supported by a good number of studies involving students with different target languages (e.g., Cheng 1998; Elkhafaifi 2005; Tallon 2009). In the present study, the Chinese version of the FLCAS also had high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha= .94.

2.3. Data collection and analysis procedures

The data were collected through a set of questionnaires consisting of the three instruments described in the above section. The questionnaires were administered to the participants during one of their class hours with the assistance of the instructors.

A 4-point Likert scale was used to score the items of the TAI, with responses ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). A 5-point Likert scale was used to score the items of the FLCAS, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The participants’ responses to the TAI and the FLCAS were scored in such a way that higher scores indicated higher trait or FL anxiety and lower scores indicated lower trait or FL anxiety. The participants’ responses were entered into SPSS files and processed by computer. Pearson product-moment correlations and partial correlations were used to address the research questions.

3. Results

3.1. Is student interpreters’ trait anxiety related to their FL anxiety?

In order to examine whether student interpreter’s trait anxiety is related to their FL anxiety, the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed between the two variables.

Table 1 presents the result of Pearson correlation between trait anxiety and FL anxiety.

Table 1

Pearson r between Trait Anxiety and FL Anxiety

As presented in table 1, student interpreters’ trait anxiety and their FL anxiety were positively and significantly related to each other. The significant positive correlation (r = .339, p < .01) between these two anxiety constructs suggested that the higher the Taiwanese student interpreters’ trait anxiety, the higher their FL anxiety, or that the higher the Taiwanese students’ FL anxiety, the higher their trait anxiety. In addition, while trait anxiety and FL anxiety had a common variance of 11.2%, they were nevertheless two distinct anxiety constructs, as around 90% of the variance was not shared between them. Thus, trait anxiety and FL anxiety in Taiwanese student interpreters were two related but distinguishable psychological phenomena.

3.2. Is student interpreters’ trait anxiety related to their learning outcomes in interpretation courses?

With an eye to exploring the relationship of student interpreters’ trait anxiety to their learning outcomes, a Pearson product-moment correlation analysis was performed on the variables under investigation. Table 2 displays the findings regarding the relationships between trait anxiety and two measures of interpretation achievement.

Table 2

Pearson r between Trait Anxiety and Achievement Measures

As shown in table 2, student interpreters’ trait anxiety had a negative relationship with mid-term exam scores, but the relationship did not reach a significant level. Likewise, their trait anxiety had a negative association with semester grades, but the relationship did not reach a significant level either. Moreover, the strength of association between trait anxiety and interpretation performance seemed to decrease as the semester progressed from mid-term to the end of the semester. Thus, the students’ trait anxiety did not play any signficant role in their mid-term and end-of-semester interpretation achievement.

3.3. Is student interpreters’ FL anxiety related to their learning outcomes in interpretation courses?

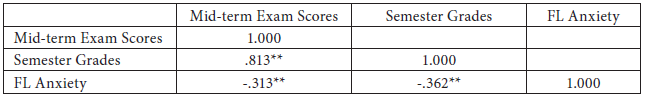

With a view to determining the relationship of the students’ FL anxiety to their interpretation learning outcomes, a Pearson product-moment correlation analysis was performed on the variables under study. Table 3 displays the results regarding the associations between student interpreters’ FL anxiety and two measures of interpretation achievement.

Table 3

Pearson r between FL Anxiety and Achievement Measures

As shown in table 3, student interpreters’ FL anxiety was significantly and negatively related to their mid-term performance, suggesting that the higher the students’ FL anxiety, the lower the students’ mid-term exam scores, or that the higher the students’ mid-term exam scores, the lower their FL anxiety. Similarly, their FL anxiety was significantly and negatively associated with semester grades, suggesting that the higher the students’ FL anxiety, the lower the students’ semester grades in interpretation courses, or that the higher the students’ semester grades, the lower their FL anxiety. Moreover, the strength of association between FL anxiety and interpretation performance seemed to increase as the semester progressed from mid-term to the end of the semester. Thus, it appeared that student interpreters’ FL anxiety had a signficant positive association with their mid-term and end-of-semester interpretation achievement.

However, as FL anxiety and trait anxiety were found to have a significant positive relationship as presented in table 1, in order to control for the effect of trait anxiety on FL anxiety, a partial correlation was performed on the relationship between student interpreters’ FL anxiety and their learning outcomes, with the influences of their trait anxiety being statistically controlled. Table 4 displays the results of the partial correlation analysis.

Table 4

Partial Correlations between FL Anxiety and Interpretation Achievement

As shown in table 4, after the effect of trait anxiety was partialled out, the relationship between FL anxiety and student interpreters’ mid-term exam scores remained significant, suggesting that the significant association between FL anxiety and the students’ mid-term interpretation performance was independent of the influence of trait anxiety. Similarly, after the effect of trait anxiety was statistically removed, the relationship between FL anxiety and student interpreters’ semester grades also remained significant, suggesting that the significant association between FL anxiety and the students’ semester-end interpretation performance was independent of the influence of trait anxiety as well. Furthermore, after the effect of trait anxiety was statistically controlled, the strength of association between FL anxiety and semester grades remained stronger than that between FL anxiety and mid-term exam scores. Thus, the signficant negative associations observed between FL anxiety and the two achievement measures were independent of the influence of trait anxiety.

3.4. Are the individual items of the FLCAS as rated by student interpreters’ related to their learning outcomes in interpretation courses?

In order to determine whether the significant negative relationships between FL anxiety as measured by the overall FLCAS and the two achievement measures hold at the level of individual FLCAS items, another Pearson product-moment analysis was performed on the variables involved. Table 5 reports the results of the correlation analysis.

Table 5

Pearson r between Individual FLCAS items and Interpretation Achievement

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

As shown in table 5, a vast majority of the individual FLCAS items were significantly and negatively associated with Taiwanese student interpreters’ learning outcomes in interpretation classes. Of the 33 FLCAS items, 24 (72.7%) were significantly associated with mid-term exam scores. That is, only 9 FLCAS items were not related to student interpreters’ mid-term interpretation achievement (items 52, 57, 59, 60, 61, 66, 68, 78, and 79). Likewise, 28 out of the 33 FLCAS items (84.8%) were associated with student interpreters’ semester grades. That is, only 5 FLCAS items (15.2%) were not related to the students’ interpretation achievement at the end of the semester (items 52, 57, 60, 68, 78). In addition, whether they were related to both outcome measures or not, most of the FLCAS items showed increases in their strength of association with interpretation achievement as the semester progressed from mid-term towards semester’s end. Thus, the significant negative relationships between FL anxiety and the two achievement measures generally held at the level of individual FLCAS items.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Unlike previous studies on anxiety and interpretation performance, most of which have employed general anxiety scales to measure the anxiety induced by interpretation, the present study utilized a combination of general anxiety scale and situation-specific anxiety scale to examine Taiwanese student interpreters’ anxiety, and found that while Taiwanese student interpreters’ trait anxiety was significantly and positively related to their FL anxiety, it was not related to either their mid-term exam scores or semester grades in interpretation courses. In contrast, their overall FL anxiety was significantly and negatively linked to the two outcome measures in interpretation courses, and so were most of the individual FLCAS items. The significant negative associations between the students’ overall FL anxiety and their interpretation learning outcomes appear to hold, even when the effect of trait anxiety was statistically controlled.

That trait anxiety was found to have negative but non-significant relationship with student interpreters’ learning outcomes in the present study cast further doubts on whether treating the anxiety induced by interpretation as a transfer of other more general types of anxiety is an adequate way to conceptualize and measure the interpreter’s anxiety. As already pointed out (Chiang 2009), although the definition of anxiety varies from study to study, most interpretation anxiety studies have treated the anxiety triggered by interpretation as a manifestation of other more general types of anxiety by utilizing trait anxiety scales, state anxiety, or a combination of both trait and state anxiety scales to measure it. However, these studies employing general anxiety measures have produced inconsistent findings regarding the relationship of anxiety to interpretation performance or achievement. For instance, whereas Gerver (1974) reported the relationship between conference interpreters’ anxiety (as measured by a trait anxiety scale) and their interpretation performance varied from significant negative correlation to positive but non-significant correlation depending on the levels of noise, Kurz (1997) found conference interpreters’ anxiety as measured by both trait and state anxiety scales did not affect their interpretation performance. Furthermore, in contrast to the negative trend between trait anxiety and interpretation learning outcomes found in the present study, Jiménez Ivars and Pinazo (2001) found that student interpreters’ anxiety (as measured by a state anxiety scale) was not related to their mid-term exam scores in consecutive interpretation courses. These discrepant results suggest that general anxiety measures, such as state or trait anxiety scales, may be incapable of fully capturing the anxiety induced by interpretation.

In fact, the problems of using general anxiety measures to examine anxiety have been widely discussed in the general literature on anxiety as well as in the literature on L2 anxiety, but they have been rarely discussed in the literature on anxiety related to interpretation. For instance, one of the major disadvantages of the trait anxiety approach is its indifference to contexts. As anxiety researchers such as Endler (1975) have argued, discussions of trait anxiety are nugatory unless trait anxiety is examined in interaction with situations. In other words, treating the anxiety associated with interpretation as a manifestation of trait anxiety is essentially viewing such anxiety as if it were no different from the anxiety induced by other situations such as public speaking or taking exams. For most interpreters, some interpretation situations will provoke anxiety, but others will not. Furthermore, the situations triggering anxiety will also differ among a group of interpreters, even when they have similar trait anxiety scores.

Likewise, utilizing state anxiety instruments to measure the anxiety induced by interpretation also has shortcomings because state anxiety scales do not address the issue of the sources of the interpreter’s reported anxiety. As L2 anxiety researcher MacIntyre and Gardner’s criticism of using state anxiety scales to measure L2 anxiety illustrated:

Instead of asking, “Did this situation make you nervous?,” they ask, “Are you nervous now?” A myriad of factors can contribute to a respondent’s reaction to such a statement. In general, it is assumed that the situation contributing most to the response is the one under experimental consideration, but this is an assumption. With state anxiety assessment, the subject is not asked to attribute the experience to any particular source.

MacIntyre and Gardner 1991a: 90

The above criticism is also applicable to studies employing state anxiety scales to examine the interpreters’ anxiety. That is, state anxiety scales do not measure the interpreters’ anxiety directly, but only indirectly by inference.

Instead of viewing interpretation anxiety as a transfer of other more general types of anxieties, a more promising alternative is to conceptualize interpretation anxiety as a situation-specific type of anxiety similar and related to FL anxiety. A situation specific type of anxiety can be regarded as a kind of trait anxiety in a given situation (MacIntyre and Gardner 1991a). Conceptualizing interpretation anxiety as a situation-specific anxiety has the advantage of taking into account the interaction between situations and persons, while avoiding the shortcomings of construct ambiguities as exemplified by the trait anxiety approach, which disregards the importance of the situation involved, or as exemplified by the state anxiety concept, which does not specify the sources of anxiety. The findings of the present study lend further support to the view that it is more productive to conceptualize the anxiety related to interpretation as a distinct type of anxiety. Using a situation-specific anxiety measure – the FLCAS – to examine student interpreters’ anxiety, the present study found the students’ FL anxiety was significantly and negatively related to their learning outcomes in interpretation courses, regardless of whether the influence of trait anxiety was statistically controlled or not. This finding is not only similar to the low but significant correlation between conference interpreters’ psychological stress and performance quality found in the AIIC (2002) Workload Study, which, as noted before (Chiang 2009), has in effect taken a step in this direction by encompassing specific stressors of conference interpreting in the Evaluating stress section of its attitude questionnaire, although the term situation-specific was never used in the study, but also similar to the results regarding situation-specific L2 anxiety variables and L2 performance reported in the L2 anxiety literature (for a more comprehensive review, see Horwitz 2001). Given the fact that interpretation generally involves an L2, and the findings of the present study, it is only natural to suggest that L2 anxiety is inherent to the anxiety students experience in an interpretation classroom, and it is highly likely that interpretation learning anxiety shares some commonalities with L2 anxiety. In other words, interpretation anxiety in general, and interpretation classroom anxiety in particular, may not be simply a transfer of other more general types of anxiety, but a situation-specific type of anxiety intertwined with and similar to L2 anxiety.

In this regard, the conceptual foundations that Horwitz, Horwitz et al. (1986) used to build their situation-specific construct of FL anxiety have important implications for the theory and measurement of interpretation learning anxiety. Three psychological dimensions underlie Horwitz, Horwitz et al.’s (1986) theory of FL anxiety, including communication apprehension, fear of negative evaluation, and test anxiety. As the findings of the individual FLCAS item analyses in the present study suggested, all of these dimensions are relevant to interpretation learning anxiety. For instance, communication anxiety should be an important subcomponent of interpretation learning anxiety: as shown in table 5 in the result section, several items tapping Taiwanese student interpreters’ English communication apprehension were significantly related to their mid-term exam scores and semester grades in interpretation courses, including item 47 I never feel quite sure of myself when I am speaking English in my English classes, item 55 I start to panic when I have to speak in English without preparation in English classes, item 64 I feel confident when I speak English in English class, item 70 I feel very self-conscious about speaking English in front of other students, and item 73 I get nervous and confused when I am speaking English in my English classes. If anxious student interpreters feel a deep self-consciousness when speaking the L2 (English) in the presence of other people, it is likely that they will have the same, perhaps even deeper, self-consciousness when interpreting into their L2 in front of others.

Fear of negative evaluation might be another performance anxiety related to interpretation learning anxiety. As shown in table 5, several FLCAS items measuring fear of negative evaluation were significantly associated with Taiwanese student interpreters’ two learning outcomes in interpretation courses, including item 53 I keep thinking that the other students are better at English than I am, item 69 I always feel that other students speak English better than I do, item 71 English classes move so quickly I worry about getting left behind, and item 77 I am afraid that other students will laugh at me when I speak English. If student interpreters fear that their English ability is inferior to other students or is negatively evaluated by them, then they will probably also worry that their interpretation ability is inferior to their peers or is negatively judged by them, especially when they have to interpret into their L2.

Test anxiety is a third performance anxiety relevant to interpretation learning anxiety. As shown in table 5, several FLCAS items indicative of test anxiety were significantly linked to Taiwanese student interpreters’ two learning outcomes in interpretation courses, including item 48 I don’t worry about making mistakes in English classes, item 54 I am usually at ease during tests in my English classes, item 65 I am afraid that my English teacher is ready to correct every mistake I make, item 67 The more I study for an English test, the more confused I get, and item 56 I worry about the consequences of failing my English classes. If test-anxious student interpreters are afraid to make mistakes in English classes, and perceive every correction as a failure, then they will probably also feel constantly tested on their English ability or interpretation ability or both in Chinese-English interpretation, and feel that anything short of a perfect test performance is a failure.

Although the findings of the present study indicate that the three dimensions underlying Horwitz, Horwitz et al.’s (1986) construct of FL anxiety might also be useful building blocks for developing a theory of interpretation learning anxiety, caution should be exercised when theorizing interpretation learning anxiety as a construct similar to L2 anxiety, as several studies employing factor analysis to unearth the subcomponents of FL anxiety have challenged Horwitz, Horwitz et al.’s conceptualization. As MacIntyre and Gardner (1989, 1991b), Aida (1994), and Wu (1994) have found, while speech anxiety and fear of negative evaluation are central components of foreign language anxiety, as Horwitz, Horwitz et al. (1986) hypothesized, test anxiety seems to be a general problem not specific to foreign language learning. If that’s the case, then it’s likely that test anxiety is also a general problem not specific to the learning of interpretation, though the present study has found that several items measuring English test anxiety were significantly related to Taiwanese student interpreters’ learning outcomes in Chinese-English interpretation classes. In addition, low self-confidence might be another important dimension of interpretation learning anxiety, as this dimension has been found to be one of the subcomponents of FL anxiety in Cheng’s (1998) study of English majors in Taiwan, and in Matsuda and Gobel’s (2001) study of Japanese EFL university students.

On the other hand, despite the above indications that interpretation learning anxiety may share some common dimensions with FL anxiety, the dimensions underlying interpretation learning anxiety cannot be identical to those underlying FL anxiety. As interpretation is a skill contingent upon listening and speaking skills in both L1 and L2, the psychological phenomenon of interpretation learning anxiety is likely to be more complicated than that of FL anxiety, and it cannot be equated with or be reduced to FL anxiety. That is, although interpretation learning anxiety may be related to L2 listening and speaking anxieties, it is unlikely that interpretation learning anxiety is simply the transfer of L2 listening and speaking anxieties. What distinguishes interpretation learning anxiety from L2 anxiety is a question worthy of further investigation.

In conclusion, the present study examined the relationship between Taiwanese student interpreters’ FL anxiety and their learning outcomes in Chinese-English interpretation courses. Results indicate that the students’ FL anxiety had significant and negative relationships with both their mid-term and final achievement in interpretation courses, and the significant relationships were independent of the influences of trait anxiety, which was significantly related to FL anxiety but had non-significant relationships with both outcome measures. Based on these results, the present study suggests that the majority of existing interpretation anxiety studies may not have been sensitive and subtle enough to the interpretation situations triggering anxiety by treating the anxiety induced by interpretation as a mere manifestation of other more general types of anxieties: Specifically, it suggests that the three dimensions underlying Horwitz, Horwitz et al.’s (1986) FL anxiety – communication apprehension, test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation – may be relevant in re-conceptualizing interpretation learning anxiety as a situation-specific multi-dimensional construct related to L2 anxiety, while cautioning against reducing it to the transfer of L2 anxiety. Such an L2-anxiety-based interdisciplinary re-conceptualization seems to hold more promise than the general anxiety approaches to advance the theory and measurement of interpretation classroom anxiety.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Here the term second language covers both second and foreign language learning. When the emphasis is being placed on the learning of a foreign language, such as the learning of English as a foreign language (EFL) in this study, the term foreign language is used.

-

[2]

In most of these classes, consecutive interpretation was the focus of instruction, while simultaneous interpretation was also taught in some of these classes in the second semester.

Bibliographie

- Aida, Yukie (1994): Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Copes’ construct of foreign language anxiety – the case of students of Japanese. Modern Language Journal. 78(2):155-168.

- AIIC (2002): Workload Study. Geneva: AIIC.

- Alexieva, Bistra (1997): A typology of interpreter-mediated events. The Translator. 3(2):153-174.

- Cheng, Yuh-show (1998): Examination of two anxiety constructs: Second language class anxiety and second language writing anxiety. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Austin: University of Texas.

- Chiang, Yung-nan (2009): Foreign language anxiety in Taiwanese student interpreters. Meta. 54(3):605-621.

- Cooper, Cary L., Davis, Rachel and Tung, Rosalie L. (1982): Interpreting stress: sources of job stress among conference interpreters. Multilingual. 1(2):97-107.

- Coughlin, Josette (1988): Inside or between languages, oral communication equals interpretation. In: L. D. Hammond, ed. Language at Crossroads. Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the American Translators Association. Medford, N.J.: Learned information, 105-113.

- Elkhafaifi, Hussein (2005): Listening comprehension and anxiety in the Araric language classroom. The Modern Language Journal. 89(2):206-220.

- Endler, Norman S. (1975): A person-situation interaction model for anxiety. In: Charles D. Spielberger and Irwin G. Sarason, eds. Stress and anxiety. Vol. 1. Washington, D. C.: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, 145-164.

- Gerver, David (1974): The effects of noise on the performance of simultaneous interpreters. ACTA Psychologica. 38:159-167.

- Gile, Daniel (1995): Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Herbert, Jean (1952): The Interpreter’s Handbook: How to Become a Conference Interpreter. Geneva: Librairie de l’Université.

- Horwitz, Elaine K. (1986): Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of a foreign language anxiety scale. In: Elaine K. Horwitz and Dolly J. Young, eds. Language Anxiety: From Theory and Research to Classroom Implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 37-40.

- Horwitz, Elaine K. (2001): Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 21:112-126.

- Horwitz, Elaine K., Horwitz, Michael B. and Cope, Joanne (1986): Foreign language classroom anxiety. In: Elaine K. Horwitz and Dolly J. Young, eds. Language Anxiety: From Theory and Research to Classroom Implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 27-36.

- Jimenez Ivars, Amparo and Pinazo, David (2001): “I failed because I got very nervous.” Anxiety and performance in interpreting trainees: An empirical study. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. 9:21-39.

- Keiser, Walter (1977): Selection and training of conference interpreters. In: D. Gerver and H. W. Sinaiko, eds. Language, Interpretation and Communication. New York: Plenum Press, 11-24.

- Klonowicz, Tatiana (1991): The effort of simultaneous interpretation: It's been a hard day…. FIT Newsletter. 10(4):446-457.

- Klonowicz, Tatiana (1994): Putting one's heart into simultaneous interpretation. In: Sylvie Lambert and Barbara Moser-Mercer, eds. Bridging the gap: Empirical Research in Simultaneous Interpretation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kurz, Ingrid (1997): Interpreters: stress and situation-dependent control of anxiety.In: Kingga Klaudy and Janos Kohn, eds. Transferre Neccesse Est. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Current Trends in the Studies of Translation and Interpreting, Budapest: Scholastica, 201-206.

- MacIntyre, Peter D. and Gardner, Robert C. (1989): Anxiety and second language learning: toward a theoretical clarification. Language Learning. 32:251-275.

- MacIntyre, Peter D. and Gardner, Robert C. (1991a): Methods and results in the study of anxiety and language learning: A review of the literature. Language Learning. 41(1):85-117.

- MacIntyre, Peter D. and Gardner, Robert C. (1991b): Language anxiety – Its relationship to other anxieties and to processing in native and 2nd languages. Language Learning. 41(4):513-534.

- Matsuda, Sae and Gobel, Peter (2001): Quiet apprehension: Reading and classroom anxieties. JALT Journal. 23:227-247.

- Moser-Mercer, Barbara (2003): Remote interpreting: Assessment of human factors and performance parameters. Visited 26 May 2005, <http://www.aiic.net/ViewPage.cfm?page_id=1125>.

- Moser-Mercer, Barbara, Künzli, Alexander and Korac, Marina (1998): Prolonged turns in interpreting: Effects on quality, physiological and psychological stress (pilot study). Interpreting: International Journal of Research and Practice in Interpreting. 3(1):47-64.

- Riccardi, Alessandra, Marinuzzi, Guido and Zecchin, Stefano (1998): Interpretation and stress. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. 18:93-106.

- Roland, Ruth A. (1982): Translating World Affairs. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Seleskovitch, Danica (1978): Interpreting for International Conferences. Washington, D. C.: Pen and Booth.

- Spielberger, Charles D. (1983): Manual for State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Tallon, Michael (2009): Foreign language anxiety and heritage students of Spanish: A quantiative study. Foreign Language Annals. 42(1):112-137.

- Wu, Chin-O (1994): Communication apprehension, anxiety, and achievement: A study of university students of English in Taiwan. Master’s thesis, unpublished. Austin: University of Texas.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Pearson r between Trait Anxiety and FL Anxiety

Table 2

Pearson r between Trait Anxiety and Achievement Measures

Table 3

Pearson r between FL Anxiety and Achievement Measures

Table 4

Partial Correlations between FL Anxiety and Interpretation Achievement

Table 5

Pearson r between Individual FLCAS items and Interpretation Achievement