Résumés

Abstract

This contribution develops a framework for research dealing with translation and localization in the media. It is stated that the borderlines between translation, localization and rewriting have become very blurred in the context of news production. Parallel to transediting, a term coined earlier, the concept of the journalator is presented, i.e., an interventionist newsroom worker who makes abundant use of translation when transferring and reformulating or recreating informative journalistic texts. By reference to both narrative theory and imagology, it is shown that the creation of national and cultural images occupies a special position in the intersections between translation studies, journalism studies and image studies. In the last part, the framework is complemented by a test case dealing with the representation of neighboring countries in Dutch-language Belgian (i.e., Flemish) TV news. It indicates that particularly the coverage of Germany is marked by specific topics and image building that were hypothesized before the analysis of the corpus.

Keywords:

- news translation,

- imagology,

- narrative theory,

- TV news,

- representation

Résumé

Le présent article contribue à établir un cadre de recherche en traduction et en localisation dans les médias. On dit que les limites entre la traduction, la localisation et la réécriture sont devenues particulièrement floues dans la production de nouvelles. En parallèle avec la transediting [transédition], un terme déjà proposé, nous présenterons le concept de journalator [journaducteur], c’est-à-dire une personne qui intervient en salle de presse et utilise abondamment la traduction pour transférer et reformuler ou recréer des textes journalistiques. En référence aux théories de la narration et de l’imagologie, nous démontrons que la création d’images nationales et culturelles occupe une place unique, à la frontière de la traductologie, des études en journalisme et de l’imagologie. En dernière partie, nous joindrons au cadre de recherche une étude de cas sur la représentation des pays voisins dans les nouvelles télévisées belges en néerlandais (flamand). Dans cette étude, l’analyse de notre corpus a confirmé notre hypothèse de départ selon laquelle le choix de certains sujets précis et la construction d’une image étaient particulièrement forts dans le cas de l’Allemagne.

Mots-clés :

- traduction dans les médias,

- imagologie,

- théorie de la narration,

- nouvelles télévisées,

- représentation

Corps de l’article

1. Translation and localization in the media

Until the beginning of the 21st century, scholarly publications on the position and impact of language use, let alone translation, in the media were very rare. This has changed considerably in the past decade, as several authors began to focus their research on news translation and linguistically determined influences in journalistic settings (see, for example, van Doorslaer 2010a for main references). Nevertheless, we should be aware that the increase in interest is mainly, if not exclusively, the merit of translation studies. The other (sub)disciplines involved in the interaction until now seem to have failed to investigate this potentially interdisciplinary topic. In a recent publication, Bielsa remarks for instance that “[m]edia sociology has neglected the study of the linguistic processes that make it possible to produce and communicate news across geographic, cultural and linguistic boundaries” (Bielsa 2010: 48). Even more recently, Demont-Heinrich in a review on Bielsa and Bassnett’s Translation in Global News criticizes media and communication studies harshly for their neglect of crucial linguistic and translational issues. It may be seen as a hopeful sign for translation studies and research on news translation that this topical discussion between sub-disciplines is being conducted in an important sociolinguistic journal.

It’s shameful that globalization, media and international communication scholars, on the whole, tend to gloss over, pretty much completely, the crucial issues of language and translation. Much of this lack of interest in language and translation may be rooted in disciplinary parochialism. Language, in the minds of many media and communication scholars, is the province of linguistics. In fact, as Bielsa and Bassnett so persuasively illustrate, the study of media and globalization is fundamentally interdisciplinary. Hopefully, some of the globalization and media and international communication scholars who should read this book will indeed encounter it and read it. They will not be disappointed if they do, and it may well inspire at least some to reconsider their previous perspective on language and translation, a perspective that views language and translation in terms which render them essentially, and problematically, invisible.

Demont-Heinrich 2011: 404-405

Undoubtedly one of the main reasons for the growing interest in translation in a journalistic environment is the relative complexity of translation in such contexts. It is not a situation in which the traditional ST-TT (source text – target text) relationship exists. Kang refers to the concept of “entextualization” (used before by other authors) for describing the process in news translation in which the original text is made subordinate to the journalistic purpose of recontextualization (Kang 2007: 221). It is a case in point for a much broader view on the object of translation studies, even to a level at which the borderlines between translation and the more encompassing concept of “transfer” become strangely blurred (see also Göpferich 2010: 374).

Several authors have also studied the relationship between translation and localization in the paradoxical context of globalization. What is global “is such not because it is the same everywhere, but because it has been adapted to infinite numbers of different cultural and social contexts” (Orengo 2005: 169). The situation described here is remarkably close to what translation in a global news environment actually does or intends to do. While using this principle as a starting point, it comes as no surprise that Orengo proposes to extend the object of localization to the study of news translation (Orengo 2005: 170). Translated news texts can be seen as a complex mixture of summarizing, paraphrasing, transforming, supplementing, reorganizing and recontextualizing procedures, as a product that is “renegotiated (in terms of meaning, form and function) to respond to a new context of use” (Kang 2007: 222).

Local press texts about foreign news are also mentioned by Pym as a legitimate case of localization of foreign-language texts, moreover a case where the characteristics of the transformation process clearly “go beyond endemic notions of translation” (Pym 2004: 4). Orengo parallels the localization processes in news translation with marketing practices and with the launching of a product in the global industrial world: as close as possible to a simultaneous release (Orengo 2005: 171, referring to Sprung).

The position where one source text (e.g., a telex message from a news agency) including its source text situation is dispersed and results in several target texts and target text situations is generally recognized as a situation that is typical of translation in a journalistic setting (e.g., in newsrooms). It can be seen as a first extension of the classical one-to-one ST-TT relationship, making use of Jakobson’s explicit enlargement of the object of Translation Studies (i.e., also including intratextual or intersemiotic translation – see Jakobson 1959). I here try to visualize the so-called first extension.

Figure 1

First extension: one source text resulting in several target texts

On the other hand, translation in journalistic environments can also be characterized by the opposite situation. When aiming at the production of one single (new or partly new) journalistic text, journalists will base that article on several earlier news items, on information and feedback from experts, and possibly also on other national and international coverage on the topic. In an earlier article, I suggested considering this journalistic use of multiple source texts (where translation is almost always involved) as a second extension of the ST-TT relationship in news contexts: a multi-source situation which is not unique, but typical of translation in the journalistic field (van Doorslaer 2010b).

Figure 2

Second extension: several source texts resulting in one target text

Although defining and identifying a source text and a target text may be “at best labyrinthine” (Orengo 2005: 180) in news translation situations, these distinctions may assist us, not necessarily in finding a way out of the labyrinth, but at least in designing a map of the complex positions of translation in everyday international news flows.

2. The revenge of the journalator

What Figure 2 visualizes is that the production of a news story, a so-called totally new text, is the result in many cases of several translation and reformulation processes. Translated texts are being “dismembered” (Orengo 2005: 170) and used as raw material in the journalistic writing process: a combination of copying, pasting, adding, deleting and translating. Seen from this perspective, the journalist very often functions as an invisible translator, the invisibility being the consequence of the fact that translation has not only been integrated into journalism, but has even been effaced by it in the perception of readers, listeners and viewers. Although journalists to a large extent make use of the principles of free translation, this “highly interventionist role of journalists as translators contrasts with the very invisibility of translation within journalism” (Bielsa 2010: 45).

Parallel to Stetting’s famous coinage, “transediting” (she conflated the words “translate” and “edit” – see Stetting 1989), this close interconnection between the daily work of a journalist and a translator could induce a plea for the use of the term journalator: a newsroom worker who makes abundant use of translation (in its broader definitions) when transferring and reformulating or recreating informative journalistic texts. As opposed to Stetting’s term, which originally was not specifically targeted at newsroom settings, journalator would make the overall presence of forms of translation in newsrooms linguistically visible. It directly refers to the journalist’s work and is associated with an active interventionist attitude. Through this active presence, to a certain extent it would also comply with many translators’ wishes to terminate the relative invisibility of their work (and the corresponding lower status). A translator very rarely feels like a terminator of (perceived or real) injustice. A journalist often does.

Critics may immediately remark that journalists will never accept this term, since they consider translation (in its narrower definition) as only a very small part of their professional activities (see Valdeón 2010: 149, for example). This is a valid argument, but mainly deals with journalistic perception and status. On the other hand, the growing presence of translators has already been recognized in newsrooms. Although the dominant model in the world news agencies still shows translation as being fully incorporated into journalistic news production, Bielsa has also detected what she calls an alternative model of translation in news agencies like IPS (Bielsa 2010: 39-42). In this alternative model, languages are promoted as being equal and texts are being translated “into the highest amount of languages possible” (Bielsa 2010: 40). This model has given rise to a new positioning of translation, and to the important hybrid figure of the translator-editor, often carried out by professional translators instead of journalists. Perhaps the journalator’s existence is less a product of science fiction than it may seem at first sight.

In any case, investigating the position of translation in news contexts confronts journalistic practice with the reality that there is no clear-cut distinction between the journalist’s discourse and the translating agent’s discourse (see also Kang 2007: 221). It is justifiable to conceive of the translator predominantly as a transmitter instead of a communicator. Also Cronin believes that “there is a sense in which the role of the translator is likely to become more, rather than less, important in the informational age” (Cronin 2003: 65).

Transmitting and transferring always involves changes of a certain kind. The translating or transmitting journalist (or journalator) inevitably takes into account the new circumstances of the target situation and audience. When the source texts (or the texts used as sources) gradually drift away from their original meaning “in order to meet readers’ expectations and ideological views” (Orengo 2005: 185), the journalator’s interventions simultaneously manifest characteristics of a translator, a communicator, a manipulator, a mediator and a transmitter. Several case studies over the last years have analyzed the target situation differences in journalistic reproduction (see for example Schäffner 2008 for an informative account on the different national renderings of a political interview). For whatever reason, newsmakers sometimes seem to stretch the journalistic freedom of text reproduction, not to mention the journalist’s ethics.

Inevitably, I think, this begs questions concerning degrees of consciousness, intentionality and systematicity involved in the production and representation of such texts. In other words, it raises questions about more or less deliberate manipulation by newsmakers, about more or less deliberate misrepresentation by media, and about distortions produced not through conscious action but through human variability and fallibility, or by underlying institutional and “cultural” systems.

Holland 2006: 249

3. Narratives in the media

It goes without saying that a certain degree of freedom in text production (although based on several other source texts) goes hand in hand with adaptation, reconsideration and reperspectivization on the basis of the new needs in the target text situation. Since subjectivities and interpretative readings of the different source texts play a role, “the entextualizing function of institutional news translation inevitably entails a reformulation of the source text in response to priorities and values relevant within the target context” (Kang 2007: 240).

In communication and journalism studies, the concepts of framing and reframing have been extensively adopted for similar processes of text (re)production in journalistic contexts. In her book on Translation and Conflict, Baker has written one specific chapter on the framing of narratives in translation. She mainly concentrates on aspects of framing as treated in the literature on social movements. Within this particular tradition, framing is defined as “an active strategy that implies agency and by means of which we consciously participate in the construction of reality” (Baker 2006: 106). The renegotiating of interpretations and texts which is the daily practice in newsrooms is an active stage in constructing a journalist’s and an audience’s reality as well as social knowledge and viewpoints.

Well-known strategies for realizing these renegotiated interpretations are foregrounding and backgrounding, making information more implicit or explicit, and of course the process of selection and de-selection of information which predetermines the construction potential of journalistic narratives (see van Doorslaer 2010b: 182-184). The absence of certain facts or topics in many cases is as meaningful as their presence would be. Subjects that are not included in the news coverage simply do not exist for the reader, the viewer or the listener; they do not belong to the news. Suppressed topics are important for the study of journalism, as it is generally acknowledged among journalism studies researchers that “the frequency of inclusion provides us with an index of social power” (Richardson 2005: 3).

Absence or presence impacts on the degree of normalization of certain representations, particularly of people, events or countries. Localization practices in newsrooms during the editing process are thoroughly applied to all kinds of reporting and are “heavily influenced not just by the norms of the target language, but also by the national narratives of the writers, which permeate the events themselves and offer domestic perspectives of European and world issues, altering the thematic organization of the texts,” as Valdeón concludes after having studied the perspectives of Euronews (Valdeón 2009: 149).

Despite all discourse on internationalization and globalization, domestic and national perspectives still seem to have a major impact on journalistic choices and formulations as well as on underlying values, norms and explanations. In a situation where a journalist-translator almost necessarily shapes narratives (see Baker 2010: 217), it is valuable to be aware of that. In the same way some journalists are embedded in war zones, their colleagues in the newsroom are embedded in translation and transferral, and they embed or fit their messages into the dominant or expected accounts. National or cultural images and knowledge (or ignorance) clearly impact on the rewriting or reformulation process as well as on the coverage about countries and nationalities, as recent research has convincingly shown.

Gottlieb has revealed the clear dominance of the Anglophone inspiration in Danish media reports on post-9/11: “As always, the Anglo-Saxon impact surpasses anything else” (Gottlieb 2010: 150). In a study on BBCMundo, Valdeón was confronted with a national and cultural image creation that “accentuates an ethnocentric view of the world whereby Anglophone news is given prominence at the expense of other more international items” (Valdeón 2008: 303). And my own analysis on the countries dealt with in foreign news items in Belgian newspapers shows quite striking correlations between the countries covered and the image determining use of news agencies (see van Doorslaer 2009). All these scholarly examples implicitly or explicitly reveal the interconnections between journalism, translation and national image building. The remarkable results of this kind of research have even resulted in an international conference in the Low Countries on the topic “Translation and National Images” (Antwerp and Amsterdam, November 2011), at which the link of the central topic with news translation was one of the sub-themes.

4. Translating and constructing images

In the past, as in the present, rewriters created images of a writer, a work, a period, a genre, sometimes even a whole literature. These images existed side by side with the realities they competed with, but the images always tended to reach more people than the corresponding realities did, and they most certainly do so now. Yet the creation of these images and the impact they made has not often been studied in the past, and is still not the object of detailed study. This is all the more strange, since the power wielded by these images, and therefore by their makers, is enormous. It becomes much less strange, though, if we take a moment to reflect that these rewritings are produced in the service, or under the constraints, of certain ideological and/or poetological currents […].

Lefevere 1992: 5

Although to my knowledge Lefevere has never studied translated images in the media, in his book he develops similar ideas about the links between image creation and power exertion in the literary field, all the more because he explicitly and deliberately used the term rewriters (Lefevere 1992). They develop an activity many characteristics of which are also present in journalistic production, as was shown before. And Lefevere adds that the images constructed by those rewriters play an important and powerful role in societies.

Another parallel can be drawn with the reception of journalistic texts. When readers of literature say they have read a book, for Lefevere this means “that they have a certain image, a certain construct of that book in their heads” (Lefevere 1992: 6). It can be hypothesized that a similar reception and construction process takes place when readers, listeners or viewers of journalistic text production read, hear or see the representation of nationalities, countries or cultures. As was mentioned before, in almost all cases aspects of translation are involved in the journalistic construction of national images. On the basis of a case study on the image of Spain in the British press, Kelly stated that translation decisions influence the portrayal for the target culture (Kelly 1998: 57). She observed that “the British press consistently reproduces and hence reinforces stereotyped images of countries, thus maintaining domestic consensus on the ‘national interest’” (Kelly 1998: 59).

So when Lefevere writes regarding the literary field that “rewriters adapt, manipulate the originals they work with to some extent” (Lefevere 1992: 8), there seems to be no reason why this construction process, be it conscious or unconscious, would not hold true for journalistic rewriting. Other related examples are the constructed images of countries passed through translated children’s literature (see Frank 2007, for example, on the constructs of Australia in French translations) or even the localized use of specific rhetorical devices in film narratives to enhance the chances for a successful reception in different nations and cultures (Cattrysse 2004). In this respect, Orengo also explicitly refers to the conscious tribal choices in marketing research, like for instance the different reception of products in Latin and Northern societies (Orengo 2005: 174-176).

A clear link between image building and translation was also established by Kuran-Burçoğlu whereby she attributes an initiating, a formative as well as a transforming role to translations as far as image construction is concerned (Kuran-Burçoğlu 2000: 144-145). She distinguishes three different levels or stages at which image building may have an impact: at the moment of the text choice, during the encoding process and during the reception process. These three stages could also be distinguished for journalistic texts and image construction.

It seems to be self-evident when studying national images and cultural representation that translation and journalism studies should also consult the findings of imagology or image studies, the discipline that studies how nations and nationalities are represented (an important recent work being Beller and Leerssen 2007). Although imagology has mainly concentrated on literary material until now, there seem to be too many interesting parallels with journalistic text production to leave this unexplored. I have indicated some of the potential interconnections and possibilities of collaboration between translation studies, journalism studies and imagology in earlier contributions (see for instance van Doorslaer 2010b: 184-186). I also refer to Chew when he states that “the potential sociocultural and, indeed, political benefits of image studies for the field of language and inter-cultural communication can hardly be exaggerated” (Chew 2006: 186).

I realize that I have devoted quite some space to the existing literature. But I considered it appropriate to develop a relatively broad framework in which translation, narratives and image studies are clearly interconnected. Even more than fifty years after Jakobson, the use of such a broad concept of translation and its overlap with journalistic rewriting, selection principles and (national) image construction, is not self-evident. Being a combination of approaches that are seldom combined, the construction of the framework itself is seen as one of the objectives of this contribution. Nevertheless, the time has now come to test the framework in a concrete case study.

5. Test case: the representation of neighboring countries in Flemish TV news

In an earlier publication the case of selection and de-selection in world news in Belgian newspapers was presented, along with its geographical distribution as well as the obvious links with language and translation choices (van Doorslaer 2009). This case study aims to complement the earlier findings by examining data on TV news. It is a fact that very few case studies deal with the analysis of TV news data (Tsai 2006 interestingly being one of the rare exceptions). This is remarkable, yet understandable, since (spoken) TV or radio news texts are much harder to retrieve and to compare than written texts in newspapers, magazines or on the internet. Even more so than in written media, translation seems to be absent in TV news. Gambier calls this “la quasi absence apparente de traductions” (Gambier 2010: 23). Nevertheless, in TV news translation is also omnipresent, especially in international reporting, the following example being a (not even exceptional) case in point.

Kurdish leader could be translated into English on the dope sheet: the desk editor could supply a written French version which could then be voiced over. Successive translations are carried out by journalists from the televised press agencies; perhaps only the voice over is carried out by a professional translator].

Gambier 2010: 26, exerpt translated by Peter Flynn[1]

In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, an electronic TV news archive is available for researchers[2]. It contains the main TV newscasts of the two major Flemish broadcasters, the public station VRT (Vlaamse Radio en Televisie) and the major commercial station VTM (Vlaamse Televisiemaatschappij). Both stations broadcast these news programs at 7 pm every day, and both are relatively long compared to similar newscasts in other countries (35-40 min). The length of these popular newscasts also influences the content. Not only are dry news facts presented, they are supplemented with background and human interest reports for purposes of illustration.

For this case study, we have concentrated on the news coverage about the Netherlands, France, Germany and the United Kingdom, all neighboring countries of Belgium. For the results discussed here, we have not yet focused on the linguistic representation of the countries in the spoken texts (that may be dealt with using a qualitative approach for follow-up research), but mainly on the selection of topics, as well as on the themes the countries are associated with in the newscasts. To use Kuran-Burçoğlu’s terminology of the different levels establishing the link between image creation and translation/transfer mentioned earlier: we here concentrate on the level of the text choice and on the part of the encoding process that involves image selection. The ENA project also gathers information about and allots codes to the different subtopics in the TV news. The corpus analyzed here contains all the 7 pm newscasts of VRT and VTM in the years 2009 and 2010, i.e., 1,460 newscasts. Figure 3 shows the total number of news items per country in these two years.

Figure 3

Total number of news items about Belgium’s neighboring countries

France and the Netherlands are the two neighboring countries most represented in the studied newscasts and most closely related to Belgium from a linguistic point of view: approximatively 60% of Belgium is Dutch-speaking, and 40% is French-speaking. Despite the fact that 2009 and 2010 were years in which the international financial crisis was very important, Germany (being the main trade partner of Belgium) is much less present.[3] The leading position of France, as well as the minor position of Germany, shows a clear parallel with the analysis of the Flemish newspapers in the earlier case study. In this TV case, the Netherlands are relatively more present in the overall number of items.

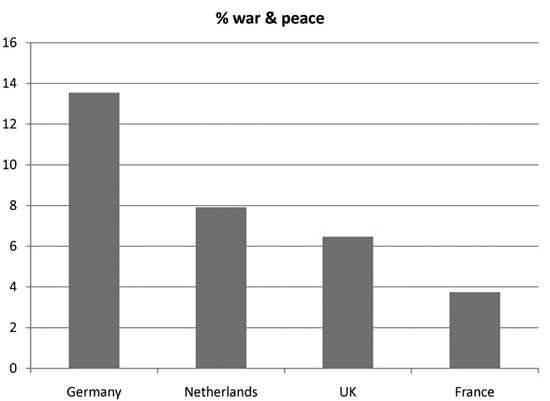

Besides paying attention to neighboring countries in general, we now want to bring in aspects of image construction or confirmation by focusing on a few topics from the corpus under study. Journalists first select topics for the foreign news, and then they create a new narrative, a new frame for the target audience. Can we hypothesize that, at least to a certain extent, their recreated narrative or translational transfer of the news takes into account existing national images (for instance through association with certain topics)? We have selected three particular (clusters of) topics and studied their share in the total news coverage about the different neighboring countries. The selected topics are: the hard topic of financial and economic news, the soft topic of the arts (including music, film, stage arts, literature and figurative arts), and the topic of war and peace, which has deeply influenced the relations between these Western European countries in the 20th century. The following figures give an overview of the results for every topic and country. The percentages represent the share of the total news coverage per country in 2009 and 2010, as can be seen in Figure 3. Ten percent of the news coverage about the Netherlands, for instance, means more or less 50 items on that topic in two years’ time.

Figure 4

Percentage of coverage of selected topics: financial and economic news

Figure 5

Percentage of coverage of selected topics: arts

Figure 6

Percentage of coverage of selected topics: war and peace

The most notable differences in the quantitative analysis of the TV news data are related to Germany: the neighboring country less represented in the Flemish TV news scores much higher on selected topics like “financial and economic news” or coverage of “war and peace.” Differences between the countries are much less marked in the shares of coverage about arts topics. But when one takes into account that the total number of news items about France is much higher, the arts coverage percentages also mean that considerably more items were shown in absolute terms.

The cultural construction of national characters in literature has been intensively studied in imagology. Images of Nations Surveyed, Part 2 of the book Imagology (Beller and Leerssen 2007: 77-259), offers an overview of these images per nation as constructed in literature. Although every country or culture is characterized by the creation of divergent images and counter-images, some stereotypes clearly prevail during certain periods. Over the last centuries, the image of France for instance was often associated with aspects of culture, both positively (civilization, fashion) and negatively (artificiality, showiness) (see Florack 2007). The results of this test case of TV materials, at least as far as the selection of topics is concerned, seem to confirm a specific part of the representation of Germany as derived from literary sources: not the 18th century “land of poets and philosophers,” but the 19th century image of an industrial power and the 20th century image of the militaristic nation (see Beller 2007: 159-164) are more dominant for Germany than for other countries.

On the other hand, new associations and new topics appear. One of the subtopics in the ENA is “migration and integration.” For the period under study it was noteworthy that almost all items on this topic were related to France. But since the other neighboring countries were hardly ever mentioned in this respect, the absolute number of items on this topic was relatively limited. For this reason we decided not to visualize it in a graph.

Of course it should be noted that other variables may influence the results, but have not been examined in this particular case study. The research on the countries dealt with in the Belgian newspapers (see van Doorslaer 2009) suggests an important impact of the news agencies, the agency subscriptions and the related language knowledge in the different newsrooms. They have not been taken into account here.

6. Conclusion

The test case and its quantitative analysis of newscasts indicate that the transfer or translation of national and cultural images is connected with the selection of topics and the association of countries with certain social fields or topic clusters. When we accept Richardson’s claim that frequency of inclusion provides us with indications of social power and relationships (Richardson 2005: 3), the coverage in the (influential) TV newscasts and their topic selection clearly impacts on national image building. Particularly when dealing with world news coverage, it is obvious that translational aspects are involved. When translation is seen as a broad process of transferral, including selecting, rewriting and recontextualizing, the adaptation and (re)localization procedures used in foreign news coverage are clearly of great interest for translation studies researchers. When a journalator selects a topic and creates or frames his new narrative, parts of the story will inevitably be modified during the translation process (transediting). The material examined in this test case indicates that in world news coverage and selection these modifications are informed by existing national or cultural stereotypes. Some topics are more pointedly associated with one country than with another. Throughout the translation and localization process, existing images are being repeated and confirmed. It seems that journalistic framing processes and the translation processes have a lot in common.

Follow-up research can use the results of this quantitative analysis as a starting point for more qualitative refinement, for instance for a focus on one single country or culture. The translating, transferring and renegotiating influence of the journalist may indeed also be present in the choice of vocabulary and/or the choice of archival images used when editing a news item. However, we have to be aware of the fact that the multi-source situation will render a traditional one-on-one ST-TT comparative approach unfeasible. Alternative methods are to be taken into consideration, like key-logging software, various forms of ethnographic enquiry, and even the imitation of journalistic translating and rewriting in an experimental setting. They all may provide valuable research findings on this topic.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

«Un leader kurde peut être traduit en anglais dans le dopesheet: le rédacteur du desk en donnera une version française écrite qui pourra ensuite être voice-overisée. Les traductions successives sont réalisées par les journalistes des agences de presse, d’images; seul peut-être le voice-over est effectué par un traducteur professionnel.»

-

[2]

In Dutch called the Elektronisch Nieuwsarchief or ENA. Visited on 15 october 2012. <http://www.nieuwsarchief.be/>.

-

[3]

Although the USA does not belong to the object of study in this corpus, it may be interesting to mention the number of items in which the USA was the main country: 1351 items, far more than double the number of items about France. Other figures: China 250, Italy 246, Spain 207, Russia 190.

Bibliography

- Baker, Mona (2006): Translation and Conflict. A Narrative Account. London/New York: Routledge.

- Baker, Mona (2010): Interpreters and translators in the war zone. Narrated and narrators. The Translator. 16(2):197-222.

- Beller, Manfred (2007): Germans. In: Manfred Beller and Joep Leerssen, eds. Imagology. The Cultural Construction and Literary Representation of National Characters. A Critical Survey. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 159-166.

- Beller, Manfred and Leerssen, Joep, eds. (2007): Imagology. The Cultural Construction and Literary Representation of National Characters. A Critical Survey. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi.

- Bielsa, Esperança (2010): Translating news: A comparison of practices in news agencies. In: Roberto A. Valdeón, ed. Translating Information. Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo, 31-49.

- Cattrysse, Patrick (2004): Stories travelling across nations and cultures. Meta. 49(1):39-51.

- Chew, William L. (2006): What’s in a national stereotype? An introduction to imagology at the threshold of the 21st century. Language and Intercultural Communication. 6(3-4):179-187.

- Cronin, Michael (2003): Translation and Globalization. London/New York: Routledge.

- Demont-Heinrich, Christof (2011): Review of [Bielsa, Esperança and Bassnett, Susan (2009): Translation in Global News. London: Routledge.] Journal of Sociolinguistics. 15(3):402-405.

- Florack, Ruth (2007): French. In: Manfred Beller and Joep Leerssen, eds. Imagology. The Cultural Construction and Literary Representation of National Characters. A Critical Survey. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 154-159.

- Frank, Helen T. (2007): Cultural Encounters in Translated Children’s Literature. Images of Australia in French translation. Manchester/Kinderhook: St. Jerome.

- Gambier, Yves (2010): Media, information et traduction à l’ère de la mondialisation. In: Roberto A. Valdeón, ed. Translating Information. Oviedo: Ediuno, 13-30.

- Göpferich, Susanne (2010): Transfer and transfer studies. In: Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies, vol. 1. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 374-377.

- Gottlieb, Henrik (2010): English-inspired post-9/11 terms in Danish media. In: Roberto A. Valdeón, ed. Translating Information. Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo, 125-150.

- Holland, Robert (2006): Language(s) in the global news. Translation, audience design and discourse (mis)representation. Target. 18(2):229-259.

- Jakobson, Roman (1959): On linguistic aspects of translation. In: Reuben Arthur Brower, ed. On Translation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 144-151.

- Kang, Ji-Hae (2007): Recontextualization of news discourse. The Translator. 13(2):219-242.

- Kelly, Dorothy (1998): Ideological implications of translation decisions: positive self- and negative other presentation. Quaderns. 1:57-63.

- Kuran-Burçoğlu, Nedret (2000): At the crossroads of translation studies and imagology. In: Andrew Chesterman, Natividad Gallardo San Salvador and Yves Gambier, eds. Translation in Context. Selected Contributions from the EST Congress, Granada, 1998. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 143-150.

- Lefevere, André (1992): Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. London/New York: Routledge.

- Orengo, Alberto (2005): Localising news: Translation and the ‘global-national’ dichotomy. Language and Intercultural Communication. 5(2):168-187.

- Pym, Anthony (2004): The Moving Text. Localization, Translation and Distribution. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- Richardson, John E. (2005): Absence. In: Bob Franklin, Martin Hamer, Mark Hanna, et al., eds. Key Concepts in Journalism Studies. London/Thousand Oaks/New Delhi: Sage, 3.

- Schäffner, Christina (2008): “The Prime Minister said…”: Voices in translated political texts. Synaps. 22:3-25.

- Stetting, Karen (1989): Transediting – A new term for coping with the grey area between editing and translating. In: Graham Caie, Kirsten Haastrup, Arnt Lykke Jakobsen, et al., eds. Proceedings from the Fourth Nordic Conference for English Studies. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 371-382.

- Tsai, Claire (2006): Translation through interpreting: A television newsroom model. In: Kyle Conway and Susan Bassnett, eds. Translation in Global News: Proceedings of the Conference Held at the University of Warwick, 23 June 2006. Coventry: University of Warwick, 59-71.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2008): Anomalous news translation. Selective appropriation of themes and texts in the Internet. Babel 54(4):299-326.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2009): Euronews in translation: Constructing a European perspective for/of the world. Forum. 7(1):123-153.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2010): Translation in the informational society. Across languages and cultures. 11(2):149-159.

- vanDoorslaer, Luc (2009): How language and (non-)translation impact on media newsrooms: The case of newspapers in Belgium. Perspectives. Studies in Translatology. 17(2):83-92.

- vanDoorslaer, Luc (2010a): Journalism and translation. In: Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies, vol. 1. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 180-184.

- vanDoorslaer, Luc (2010b): The double extension of translation in the journalistic field. Across Languages and Cultures. 11(2):175-188.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

First extension: one source text resulting in several target texts

Figure 2

Second extension: several source texts resulting in one target text

Figure 3

Total number of news items about Belgium’s neighboring countries

Figure 4

Percentage of coverage of selected topics: financial and economic news

Figure 5

Percentage of coverage of selected topics: arts

Figure 6

Percentage of coverage of selected topics: war and peace

10.7202/009018ar

10.7202/009018ar