Résumés

Abstract

In 1841 John Murray published a sumptuously ornamented edition of John Gibson Lockhart’s Ancient Spanish Ballads. Murray’s new edition, printed using the very latest bookmaking technologies and pitched at a readership newly accustomed to paying exorbitant prices for book ornaments and illustrations, was radically different from the first edition of Lockhart’s ballads, which had appeared without accompanying ornament in 1823. Illustrated by the leading illustrators of the day and decorated throughout in multiple colors by the architect Owen Jones (who would go on to become famous as a Superintendent of the Great Exhibition and the author of The Grammar of Ornament), Murray’s edition represents a stunning departure in Victorian printing and a highpoint in mid-Victorian design generally. At the same time, it crystallizes a debate about the nature and application of artistic design that was beginning to emerge in the early years of Victoria’s reign and that would erupt with maximum vigor ten years later in the confrontation between John Ruskin and the South Kensington School. The tension between flat, stylized design and what Ruskin was later to term “truth to nature” is already palpable in the conflict between illustrations and ornaments to Murray’s book. However, it was the involvement of Owen Jones that especially distinguished the volume, as it gave Jones the opportunity to demonstrate in a practical way ideas about design, color, and style that he would theorize fifteen years later in The Grammar of Ornament. Those ideas are especially resonant today, given recent work on the history of the book and the “bibliographic codes” of literature, since the effect of Jones’s work is to expose the textual condition of Lockhart’s poetry itself and to harness the eye as an active constituent in the act of reading. Fifty years before the work of William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Jones and Murray showed Victorian readers that a printed book might be a thing of real beauty and that poetry, no less than painting or architecture, is dependent on the perceptual structure of its textual vehicle.

Corps de l’article

In the work of the artist, the pleasure we receive is always relative to the objects… depicted or sculptured; in the work of the ornamentist, the pleasure we receive is always referable to the work itself. The one, in short, is a figment that affords us pleasure by suggesting some actual or possible beauty of nature; the other is a reality that, so far as it goes, pleases us in the same sense, and for the same reason, that nature does itself.

William Dyce, Introduction to Drawing Book of the Government Schools of Design (1842)

A book that must have illustrations, more or less utilitarian, should, I think, have no actual ornament at all, because the ornament and the illustration must almost certainly fight.

William Morris, “The Ideal Book” (1893)

In the late 1830s and early 1840s, British designers, educators, and legislators were beginning to disagree sharply about the nature and application of artistic design.[1]And although the battle was not so fierce as that which would unfold in the mid-1850s, when Ruskin would take on the forces of South Kensington in arguing for the importance of “truth to nature” and against any tendency to abstraction or “conventionalizing,” the dividing lines were already beginning to become clear. On the one hand were those, like the painter Benjamin Hayden, who would place figure drawing and “general proportion” at the center of a national art curriculum, or James Skene, secretary to the Royal Institution for the Encouragement of Fine Arts in Scotland, who testified in 1835 that “drawing from the round [is] the rudiments of design;” that British designers were “deficient” in “correctness of drawing the human figure;” and that insofar as pattern-making was concerned, “there is a very great defect… in botanical accuracy.”[2] Design was best, according to such figures, if it adhered closely to still-life drawing and maintained absolute fidelity to the forms of nature. On the other hand were so-called pioneers of modern design such as Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, who argued that “designs should be adapted to the material in which they are executed” (Pugin 1), and William Dyce, soon to be Director of the Government Schools of Design, who wrote in his 1842 Introduction to The Drawing Book of The Government Schools of Design that “ornamental art is rather abstractive and reproductive than imitative” (n.p.).[3] Where the fine artist “imitates the beauty of nature, by making beautiful images of natural objects,” says Dyce, the “ornamentist … proceeds by a method directly the reverse: Beauty with him is a quality separable from natural object” (n.p.). For Dyce, ornamental design, though a species of “art” and not merely a form of artisanship,[4] demanded very different protocols from those employed in the production of fine art, and the experience to be had in viewing such designs was of a peculiarly self-contained kind. In the work of fine art, “the pleasure we receive is always relative to the natural objects depicted or sculpted.” In the work of ornament, by contrast, “the pleasure is immediately referable to the work itself” (n.p.).

It is within the context of this debate that the 1841 publication of John Murray’s sumptuously ornamented edition of a book of ballads by the Scottish man of letters, John Gibson Lockhart, demands to be understood. Murray’s edition of Ancient Spanish Ballads incorporated decorative devices and illustrations on a scale unprecedented in the history of the mass-market book, and these played directly, even self-consciously, to the ongoing debate I have been describing. In the conflict between this book’s illustrative and more purely decorative elements, as we shall see, we can detect not merely its producers’ deep equivocation about just what relevance the emerging discourse of design possessed for works of literature, but also dramatically different understandings of what design comprised in the first place.

Lockhart’s Ancient Spanish Ballads, containing free translations of Spanish ballads largely from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, had first been published to critical acclaim, without any accompanying ornament, by Blackwood in Edinburgh in 1823.[5] “The volume proves that Mr. Lockhart is a master of the English language and … will entitle him to rank with the best of our living poets,” one reviewer had remarked in 1823 (Rev. of Ancient Spanish Ballads [1823], 357). But by the late 1830s, when Lockhart had already for some years been the editor of Murray’s Quarterly Review, Murray felt that Lockhart’s early work deserved wider recognition. Murray was determined “to rescue a work of real genius from comparative obscurity” while also producing “the Book of the Season for next Christmas,” writes one biographer (Smiles 2:449-50).[6] So great was Murray’s determination in this regard that his 1841 edition was produced at a financial loss, notwithstanding its gorgeous design.[7]

By this time, developments in British publishing had created the conditions for an edition of Lockwood’s poems radically different from the Blackwood first edition of 1823. The early years of Victoria’s reign witnessed a spate of high-quality, illustrated publications attempting to marry illustration and design with a book’s verbal, often poetic, text. The publication of such finely-illustrated works such as Pearls from the East, or Beauties from Lallah Rookh (Tilt 1837), The Authors of England (Tilt 1838), Clarkson Frederick Stanfield’s Coast Scenery (Smith Elder 1836), and the annual Drawing Room Scrap Book (Fisher, Son & Co., 1832-52) each featuring numerous, high-quality, illustrated plates engraved on steel, copper, and wood, had established a vogue for art gift-books that were high in craftsmanship, price and profitability (McLean 25-28). Of particular note is the vogue for picturesque annuals that sprung up in the 1830s, spurred in part by the new respectability and artistry brought to book illustration by the employment, as illustrators, of landscape painters such as J. M. W. Turner, George Cattermole, and Stanfield (McLean 28). Like the travel handbooks published so successfully by Murray from 1832 onwards, such picturesque illustrated books spoke to a growing craving for vicarious travel among a middle-class readership possessed with new leisure, cash, and a curiosity about the world stimulated by the growth of railways.

Picturesque books about Spain seem to have been especially in demand. As Diego Saglia has recently demonstrated, Spain had been the object of Romantic fascination since the 1790s (41), and this fascination had been consolidated by the publication of Sir Walter Scott’s Vision of Don Roderick, Robert Southey’s Roderick, Last of the Visigoths, and by a number of works by Lord Byron including Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and Lara. One manifestation of this Romantic fascination with Spain, clearly motivating the translation and 1823 publication of Lockhart’s ballads in the first place, was a preoccupation with translating Spanish medieval or “frontier” ballads: the “Romance of Alhama,” for instance, was translated by Southey, Thomas Rodd, Matthew Lewis and Byron before its re-translation by Lockhart and Sir John Bowring in the 1820s (Saglia 257-59). However it was the literary success of Washington Irving’s Conquest of Granada and Tales from the Alhambra, published by Murray in 1829 and 1832 respectively, that had stirred British attention to Andalusia and the Alhambra in particular. George Vivian, David Roberts, and John Frederick Lewis had all issued folio volumes of lithographed Spanish scenes and subjects in the late-1830s, and Roberts had been the illustrator for a number of highly praised picturesque “Landscape Annuals” devoted to Spanish landscapes.[8] “The demand for views of Spain at this time was phenomenal,” comments one observer (C.T. Lewis 140). This was a demand on which Murray first capitalized with the exquisitely engraved edition of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage published in 1841, a book representing perhaps the definitive marriage of the early-Victorian craving for “views” with Byron’s text.

At the same time as the aforementioned works by Byron, Southey, Irving, Roberts, and others had created a pressing demand for Spanish subjects in art and poetry, the literary success of so-called “Romantic Orientalist” works such as Thomas Moore’s Lallah Rooke, Southey’s Thalaba The Destroyer, and Byron’s Eastern Tales had inspired massive popular interest in an imagined “Orient” located beyond the fringes of Christian Europe (Leask; Sharafuddin). In some Romantic Orientalist works, Spain itself was characterized as part of such an exotic, un-Christian, un-European domain (Saglia 254-330). This interest was stimulated by Orientalist works of art, anthropology, and archaeology too, such as James Cavanah Murphy’s Mahometan Empire of Spain (1816), and extended well into the late 1830s in such works as Edward Lane’s An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), and Sir. J.G. Wilkinson’s Manners & Customs of the Ancient Egyptians (1837 and 1841).

Murray’s 1841 edition of Lockhart’s Ancient Spanish Ballads, then, was timed to exploit a number of recent developments, including burgeoning interest in Spain and in a largely-imagined Orient beyond the fringes of Christian Europe, as well as the incursion of landscape art into the printed book so as to satisfy the demand for picturesque forms of literature. A measure of its success, in this regard, can be gauged from the fact that it went into numerous editions in its own right, being reprinted in 1842, 1856, and 1859, often with entirely new elements of decoration, illustration or overall design.[9] But Murray’s volume was timed, too, to exploit developments proceeding from a very different direction. By the late 1830s, publishers and printers were showing a pronounced interest in developing techniques for color printing in the wake of exciting new theories about the “laws of harmonious colouring” and their application to the arts. David Hay’s Laws of Harmonious Coloring (1828) was one of the first and most influential attempts to apply the burgeoning science of Chromatography to the practice of decoration or design,[10] and Murray himself, who seems to have been acutely interested in color theory, was to issue the first English translation of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s influential Theory of Colours, just one year prior to issuing his new edition of Lockhart’s Ballads.[11] While color treatises had to wait another thirty years before harnessing the power of color printing as such,[12] early Victorian printers and publishers seem to have been sufficiently stimulated by the scientific and aesthetic arguments to have attempted applying “harmonious” color to literary works on a scale previously unthinkable. George Baxter in particular had recently shown the viability of producing high-quality color relief prints and illustrations for the mass market. Although handicapped commercially by the timing and scale of its publication, Baxter’s Pictorial Album; or the Cabinet of Paintings, published by Chapman and Hall in 1837, had established a benchmark for the mass printing of high-quality colored plates (McLean 38).[13]

Even before Murray commissioned him to design and oversee his edition of Lockhart’s Ancient Spanish Ballads, no book artist had done more to unite these different strains in early Victorian publishing than Owen Jones, who was to become famous in later years as a Superintendent of the Great Exhibition and as the printer-author of The Grammar of Ornament. In 1836 Jones had published the first parts of his monumental Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of The Alhambra, two years after returning from a long sojourn in Granada where he and his companion Jules Goury had made lengthy, detailed visual records of the colorful designs to be found among the courtyards and inner walls of the Alhambra. This pioneering work, known ever since simply as The Alhambra, had been aimed primarily at a readership of professional architects and scholars. The exorbitantly high costs and labor of its publication entailed that it was issued piecemeal, by subscription, to only the wealthiest readers. Publication of the work was not, in fact, completed till 1845, and as late as 1854 many copies remained unsold, forcing Jones to auction off his remainders and to absorb their high costs at his own expense (McLean 80, 96). Even still, the earliest parts must have caused a considerable stir on account of the brilliance and fidelity with which elements of architectural design were transposed to, and reproduced in, the medium of print. On returning from Granada, determined upon publication, Jones realized early on that the colorful decorative schemes he wished to illustrate would demand the application of printing techniques never previously employed in Britain.[14] Undeterred by the refusal of existing printing establishments to undertake this work, he had succeeded in setting up his own print shop, with the aid of the lithographic printers Day and Haghe, and after a period of experimentation—and at massive cost—had proceeded to issue the first of ten parts, each containing up to five chromolithographed plates illustrating features of the Alhambra’s design (Ferry 175-88). Besides constituting astonishing examples of a Moresque visual style for which Jones would subsequently become famous, these plates were among the earliest chromolithographs ever produced in Britain and thus a benchmark in the history of color printing (see Friedman, McLean, and Frankel).

Figure 1

“Spandril of An Arch, Hall of the Ambassadors,” Chromolithograph from Plans, Details, Elevations, and Sections of The Alhambra.

By 1841, when Murray’s new edition of Ancient Spanish Ballads was published, Jones’s reputation as the author of The Alhambra went before him. In a letter to Jones from this time, in which Murray expressed his desire that the complete book should meet with Jones’s approval, Murray confessed that he had undertaken Ancient Spanish Ballads and commissioned Jones specifically in order “to secure for [Lockhart’s] translations the publicity they merit and have not yet obtained” (Murray ms. 41911). In advertisements for Ancient Spanish Ballads, Murray flagged the fact that the work was designed by “Owen Jones, Architect, Author of The Alhambra.”[15] And on reviewing the volume, The Athenaeum remarked that “the freedom of design, the variety and the delicacy… are worthy of the enthusiastic author of the noble work illustrative of the Alhambra, a work in itself an encyclopedia of decoration” (Rev. of Ancient Spanish Ballads [1841], 827). Clearly Murray had commissioned Jones to design ornaments for Ancient Spanish Ballads on the strength of Jones’s reputation as the author–printer of The Alhambra. Jones had almost single-handedly started a vogue in Britain for Moorish decoration, thereby complicating and enriching the picture of what “Spain” and “picturesque” meant.

But Murray also wanted to capitalize on the recent vogue for line-engraved pictorial illustration of Romantic subjects. In this regard, Jones’s commission was problematic, for Jones was by no means skilled as a representational artist. His reputation in this respect was far eclipsed by that of established illustrators like William Harvey, who had illustrated an outstanding edition of The Arabian Nights in 1840, or by the emerging figure of Henry Warren, later President of the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour, who “built a reputation for oriental genre painting without ever having traveled to the East” (Buchanan-Brown 198). Murray, in fact, had commissioned multiple illustrations from Warren for the edition of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage published in 1841. Jones’s deficiencies in this respect were all the more acute insofar as Murray had by this time “quietly adapted his firm’s publications to the prevailing demand for more and more illustration” (Buchanan-Brown 153-54). By 1841, Murray’s business was predicated in part on the production of elaborately illustrated editions of poetry, especially Byron and George Crabbe, many engraved by the distinguished firm of W & E. Finden.

For these reasons, Jones was never given the responsibility to “illustrate” Lockhart’s ballads as such. Though it seems reasonable to speculate that Murray’s new edition was first mooted while Jones was still engaged on the production of chromolithographic plates for Wilkinson’s Second Series of the Manners & Customs,[16] Murray must have felt surer of the edition’s success by commissioning Harvey and Warren as well as more distinctly picturesque artists such as David Roberts, William Allan, and William Simson.[17] Roberts, Simson, and Allan, to be sure, were eminent Scottish artists, and it seems almost certain that, if they knew Murray as a Scotsman, they also knew Lockhart—Walter Scott’s son-in-law and biographer, as well as the biographer of Burns, and still a major figure on the Edinburgh scene despite becoming resident in London in 1825—independently from whatever interest they had in his Spanish Ballads.[18]

When we turn to the book itself, the broad ambitions of its producers are boldly announced even before we open the covers. On the front boards of the 1841 edition an elaborate arabesque design is stamped in gold on highly-burnished, light-red cloth boards.[19] The title words “Lockhart’s Spanish Ballads” are situated in the center of a series of frames, the lettering surrounded and illuminated by masses of abundant vegetative growth. Although flat and heavily stylized, produced in a fashion that would have satisfied Pugin’s and Dyce’s exacting standards,[20] the design hints at a Moorish window scene and in some respects anticipates Jones’s plates illustrating doorway and window decorations from Volume Two of The Alhambra. The effect is to suggest that Lockhart’s ballads are artifactual or iconic entities, to be viewed through the mediating lens of Moorish decoration.

Figure 2

Die-stamped binding design by Owen Jones from J. G. Lockhart, Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 3

“Small Panel in Jamb of a Window, Hall of the Ambassadors,” Chromolithograph from Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of The Alhambra.

These boards are all the more striking when we consider their technical innovativeness. The art of blocking in gold, like that of cloth binding, was a relatively new phenomenon in English publishing at this time.[21] As Ruari McLean notes (216), Murray’s binding for Ancient Spanish Ballads is one of the earliest examples of a design blocked in gold over the whole front side of a book, and it must have struck a loud chord with Victorian readers, not merely on account of the fine materials and unprecedented craftsmanship involved, but also because of the modernity and abstraction of the design. When viewed in the context of other trade bindings of this time, Jones’s binding is still very appealing to the eye, its lightness of touch quite remarkable given Jones’s later predilection for heavy bookbinding materials such as wood and papier maché. In many respects, the binding for Ancient Spanish Ballads, executed by Remnant & Edmonds, foreshadows those of Aubrey Beardsley and Charles Ricketts, executed in the 1890s by Leighton, Son and Hodge, in whose hands the art of gold-blocking on cloth would arguably reach its apogee.

The binding to the 1841 edition embodies the very latest developments in trade bookbinding, then, as well as Jones’s absorption of principles beginning to be advanced in the growing debate about design, such as Dyce’s assertion of the need for ornament to be “abstractive.” Its visual pretensions are carried over into the body of the book proper by specially printed decorative endpapers (printed in three colors in the 1842 edition and in just one color in the 1841 edition) designed by Jones himself (McLean 80). But nothing can have prepared the book’s readers for the feast of ornament and color to be discovered among the book’s preliminary pages, where the reader encounters, in close succession, the following sequence: a chromolithographed half-title, blocked in three colors; a title-page decorated and engraved in two colors as well as in black; an elaborate “imprint” page on the verso of the title-page proper combining chromolithography and wood-engraving (this page proudly announces that Vizetelly and Co. acted as printers and engravers of the book);[22] a decorated table, “Contents and List of Illustrations,” printed in two colors, in which the artist or “designer” of each of some eighty-odd illustrations is conspicuously named; and finally another chromolithographed fly-title, printed in three colors, announcing the book’s Introduction. The latter faces a page in which a Moorish window-vignette is simply engraved in blue, unaccompanied by any verbal text.

Figure 4

Chromolithographed half-title from Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Contents and List of Illustrations from Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 8

Contents and List of Illustrations from Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 9

Chromolithographed fly-title announcing Introduction to Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 10

Wood-engraved Moorish window vignette from Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Prefacing the literary text in this colorful, highly ornamented, manner had been a marked feature of early-Renaissance manuscript books, and it was to become a conspicuous feature of both trade and private-press books during the so-called Renaissance of Printing of the 1890s and early 1900s.[23] But such self-conscious attention to the preliminary pages of a modern trade book was unprecedented in 1841. As one reader remarked at the time, “I have never seen anything approaching to them…. [The book] really does high honour to British Art, and to the British Press.”[24] Where historical tendencies in British publishing since the late-18th century had minimized the visual paraphernalia of the printed book’s preliminaries, simplifying title-pages and speeding readers’ passage to the “text itself,”[25]Ancient Spanish Ballads obliges its reader to linger over such pages and to see the text itself as a concrete, corporeal entity, inseparable from the printed medium through which it comes to its reader. The original Blackwoods edition of 1823 had treated Lockhart’s ballads as purely imaginative entities, at a distant remove from the reality of the contemporary British reader. By contrast, the preliminary pages to the 1841 edition insist that we view the text as something seen or felt, much like the works of Islamic architecture that inspired it.

But before I explore the implications of these pages for our understanding of Lockhart’s poetry itself, it should be noticed that the book’s preliminary pages also manifest an evident tension between the older technologies of letterpress printing and wood engraving, on the one hand, and the newer technology of chromolithography, on the other. This tension is perceptible on the imprint page, for instance, where Vizetelly’s rococo imprint sits oddly with Jones’s Moorish borders (see fig. 6), and again in the page-opening where the chromolithographed fly-title “Introduction” (see fig. 9) faces the engraved, single-color, window-vignette (see fig. 10). In this tension, we can detect something of the distinction Walter Benjamin draws between signs, which Benjamin describes as utilizing the “horizontal position” of writing or books, inscribed flatly for “symbolic” decipherment, and colored marks, which occupy the “longitudinal section” or “vertical position” of painting (“Painting and The Graphic Arts” 82) and which, for Benjamin, consequently appear “always absolute and resemble nothing else in [their] manifestation” (“Painting, or Signs and Marks” 84). As Benjamin explains further:

A picture must be held vertically before the observer. A mosaic lies at his feet. Despite this distinction, it is customary to regard the graphic arts as paintings. Nevertheless, the distinction is very important and far-reaching …. We might say that there are two sections through the substance of the world: the longitudinal section of painting and the cross-section of certain pieces of graphic art. The longitudinal section seems representational; it somehow contains … objects. The cross-section seems symbolic; it contains signs. Or is it only when we read that we place the page horizontally before us?

“Painting and The Graphic Arts” 82

The realm of the sign comprises various territories which are defined by the fact that, within their borders, “line” has various meanings …. This realm is probably not a medium but an order that appears at the moment to be wholly mysterious to us …. The sign is printed on something, whereas the mark emerges from it. This makes is clear that the realm of the mark is a medium … for the mark is always absolute and resembles nothing else in its manifestation.

“Painting, Or Signs and Marks” 83-84

Benjamin’s comments are helpful in explaining the relationship between color, mass, and written inscription in some of the preliminary pages to Ancient Spanish Ballads. In the half-title for the book, for instance (see fig. 4), the hand-drawn, lithographed words “Spanish Ballads” appear uncertain about their own significatory function. Surrounded by masses of ornament in red, gold and blue, and situated within a Moorish window-frame, the words “Spanish Ballads” seem to merge with the filigreed metalwork of the window-lattice. Like the window-frame itself, they cast a slight shadow, as if they were three-dimensional or “upright” things, thrown into relief by light projected from the left. As with the word “Ancient,” which at first sight seems indistinguishable from the gold and red materials of the escutcheon on which it is printed, written language appears here as a purely concrete thing, like Benjamin’s “mark” or medium, wholly subsumed within the objective world of vision.[26] It is significant, in this regard, that virtually no part of the paper has been left unprinted, except for the narrow margin surrounding the overall design, despite the use of only three colors.[27] Words are treated here as blocked masses or marks, to be relished with the senses.

By contrast, the title-page proper prints title and bibliographic information more conventionally (see fig. 5), using letterpress types (both Gothic and modern-face) to announce the title and names of the book’s chief producers. But even still it is the page’s wood-engraved borders and the combined interplay of red and blue inks that catch the eye. One has to squint to read the 6- and 7-point type with which key information is printed in black, telling us that the book contains “numerous illustrations from drawings by William Allan R. A., David Roberts R. A., etc,” (see fig. 5) or that “the borders and ornamental designs [are] by Owen Jones, architect” (see fig. 8). Though such information is typographically centered, the overall effect of the page is literally ex-centric insofar as the eye is pulled to the margins by the riot of color and design taking place there. Though the title-page is by no means the most strikingly original piece of printing in the book, its typography gives a hint of the dialectical battles between eye and mind that will be acted out, writ large, on the book’s ensuing pages.

Before taking leave of the title-page proper, two other elements of its design demand comment. The first concerns the hierarchy structuring the title words proper: for the phrase “Spanish Ballads,” unusually printed in red in 30-point Gothic type, assumes priority over the word “ancient,” printed just above it in 18-point type, as well as over the phrase “historical and romantic,” printed just below in 14-point type. This latter phrase had been employed by Lockhart himself, along with the term “Moorish,” to taxonomize the ballads on their first publication in 1823.[28] But here the taxonomic qualifiers, as well as the “ancient” historicity of the ballads, are secondary considerations. Though the borders foreground a spirit of “Moorishness” that was marginal at best in the 1823 edition, it is the Spanishness of the ballads that is being accentuated so far as the typesetting is concerned.[29]

The second notable element of the title-page is the phrase “The borders and ornamental vignettes by Owen Jones, architect.” Though not visually prominent in the general scheme of the page, this phrase represents the first instance, in a modern English trade book, of readers’ attention being called to the overall design of the book as opposed to its “illustration”—that is, to the artistry and individuality of the book’s borders and ornaments as well as to its representational aspects. The professional designation “architect” is especially significant in this respect, since it brings the cultural capital of a profession at once respected, artistic, and practical to bear as a legitimizing force upon the book’s design (and dimly foreshadows William Morris’s famous pronouncement fifty years later that, in order to succeed, ornament “must… become architectural” [“The Ideal Book” 72-73]). This proclamation of the book as a designed entity, not merely an illustrated one, is repeated a few pages later, at the end of the book’s table of contents and illustrations (see fig. 8), where blue print calls the reader’s attention to “the coloured tiles, borders, and ornamental letters and vignettes, by Owen Jones.”

For all its visual preciosity, the title-page to Ancient Spanish Ballads would not have struck Victorian readers as a great technological advance since it relies on the familiar technologies of letterpress and woodblock. In many ways, the design printed on its verso is a far more radical experiment and a more striking declaration of the book’s overall intentions (see fig. 6). Here the combined skills of the book’s designer (Jones), principal illustrator (Warren), and printer (Vizetelly & Co.) have been employed to highlight and celebrate, by decorative means, the fact of the book as a printed entity. The page is a consummate example of the chromolithographer’s skill, in many ways surpassing the printing of those parts of Jones’s Alhambra that had already seen the light of day. Although informed by the Moorish principles to be witnessed in the Alhambra designs,[30] principles that Jones would articulate and rationalize in The Grammar of Ornament (185-204), the design shows a restraint and delicacy on Jones’s part that he did not always subsequently practice. In part, this must be ascribed to the collaborative nature of this book’s production, since Jones has left space within his border designs to showcase the work of illustrator and printer: Warren’s rococo cupids float in lithographed space, holding up a scroll on which the identity of the book’s printers and engravers is announced in red machine-cut type. The impression evoked is one of balance and poise; despite the materials and technique on display, the overall effect is transcendent, accentuating the printing of this book as something heavenly and other-worldly.

The verso leaf containing these illuminations to the printer’s imprimatur is one of five chromolithographed pages in the 1841 edition. Of these five, three may properly be termed “fly titles,” insofar as they introduce or demarcate discrete sections of the book as a whole (the fourth consists of the decorative half-title reproduced in fig. 4 and discussed in para. 16 above). The fly-title announcing Lockhart’s “Introduction” to the ballads (see fig. 9) displays a more economical use of color and a more delicate use of patterning than the half-title discussed earlier, and the coloring is arguably more effective for the large amount of white-space containing it, giving the page a sparkle and three-dimensionality absent from the half-title. Despite being used more sparingly here, the color red is the more pronounced for being largely restricted to the ornament’s central device, where it operates as the ground for the word “Introduction,” written in imitation of the Alhambra inscriptions.[31] Swirls of filigreed gold and vine-like forms in blue at once focus the eye upon this central “Introduction” motif and direct the eye outwards to the vacant areas of the page, calling our attention to the facing-page opposite, on which a decorative device—again reminiscent of a window jamb or alcove—is printed in blue, unaccompanied by any written text, and framed by a single blue line. As with the words “Spanish Ballads” on the half-title, the term “Introduction” demands to be seen as a visual mark, not merely a sign, and it is printed in self-conscious imitation of certain Arabic inscriptions, written into the decorative schemes of the Alhambra, about which Jones would write memorably in The Grammar of Ornament as follows:

The ornament of The Alhambra wanted but one charm… symbolism. This the religion of the Moors forbade; but the want was more than supplied by the inscriptions, which, addressing themselves to the eye by their outward beauty, at once excited the intellect by the difficulties of deciphering their curious and complex involutions, and delighted the imagination when read, by the beauty of the sentiments they expressed and the music of their composition.

185-86

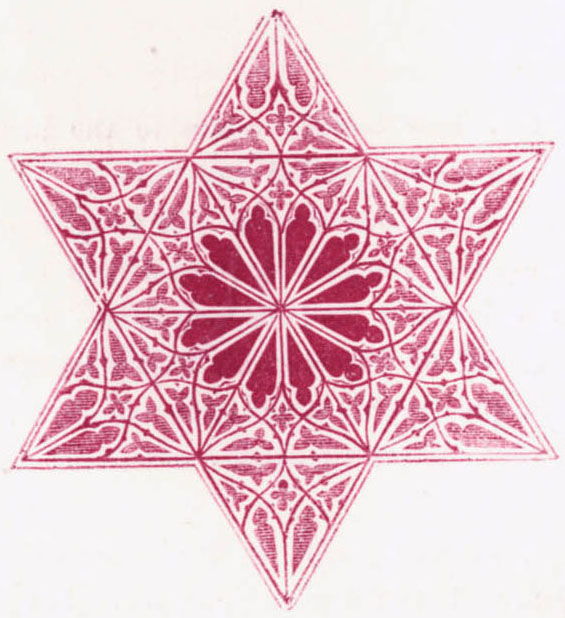

Similar Moorish elements are to be found in Jones’s spectacular fly-title to the five “Moorish Ballads” (see fig. 11) that constitute the central section of the book. As has already been remarked, Lockhart was not concerned with this section sufficiently to flag it, alongside “Historical and Romantic” ballads, in the collection’s subtitle; and in a prefatory note to the Moorish section, written for the 1823 edition, he confesses “It is sometimes very difficult to determine which of the Moorish Ballads ought to be included in the Historical, which in the Romantic class; and for this reason, the following five specimens are placed by themselves” (Ancient Spanish Ballads [1823], 122; Ancient Spanish Ballads [1841], n.p.). But Jones’s splendid fly-title reclaims these ballads from the purely intermediate space to which Lockhart consigned them. The page’s affinities with the book’s half-title establish important continuities between these ballads and the rest. As importantly, the fineness of the workmanship here, as well as the splendid illuminated capital “I” that commences this section, is a form of homage, even sacrifice, to the content of this section, especially when we consider the absence of such workmanship from the prefatory material to the (far-longer) Historical section. Precisely because this page serves no useful function and is purely caliphoric in nature, the page lends value to the thing it adorns. As Ruskin famously argued, the very costliness and complexity of the decoration represents “a desire to honor” (18), an “act of adoration” (25), or “an offering, surrendering, and sacrifice of what is to ourselves desireable” (17). And much as for Ruskin, works of devotional and memorial architecture ought to be adorned with the most costly and labor-intensive materials “merely because they are precious, not because they are useful or necessary” (17), so Jones’s ornamented fly-title to “Moorish Ballads” represents a form of expenditure or sacrifice—of time, money and creative enterprise—in the service of the Moorish spirit that (for Jones and Lockhart, at least) drives this section of the book. As Oleg Grabar has argued, ornament operates in the service of something and mediates between the viewer and the object adorned: “it is the mediator which accompanies one’s entry into the building and which seeks one’s attention inside a building, just as it remains a constant companion of the user of a book or the drinker from a cup” (103).

Figure 11

Chromolithographed fly-title announcing “Moorish Ballads” section of Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Considered from a reader’s point of view, Jones’s carefully ornamented half-title and fly-titles exert tremendous effects over the pages that follow them, exposing what Jerome McGann would term the textual condition of language itself (3-6, 88-98). In this respect, they accelerate the usual logic of title-pages to a point at which the structure of the book, or the dependency of language on its textual vehicle, becomes self-conscious and visible. “Compared with its following text, the title is a trifle,” Theodore De Vinne writes, “and yet the impression made upon a casual reader by any title is not to be undervalued” (xv). “The title-page, besides fulfilling its function of announcing the subject or name of the work and its author,” agrees Oliver Simon, “gives to the book the general tone of its typographical treatment” (61). De Vinne’s and Simon’s comments hint at what is significant about Jones’s title-pages for Ancient Spanish Ballads; for Jones’s title-pages perform a role that constitutes and conditions the text that ensues. They assert the “architecture of words” (De Vinne 332) while simultaneously proving what illuminators, rubricators and readers of Medieval manuscripts once took for granted, that a book whose content was prized might be “a piece of beauty obvious to the eyesight” (Morris, “Some Thoughts” 1-2). “My endeavour is to connect the whole that the eye should run from beginning to end without feeling uncomfortable,” remarked Jones.[32] Skillfully deploying the new technology of chromolithography, Jones’s title-pages embody what one of his contemporaries termed a veritable “art of Euchromatics, or beauty of color” in which a “real aesthetic harmony of color” might be relished purely for its own sake (Fergusson 109).[33]

* * *

To this point, readers might justly claim that Murray’s edition of Ancient Spanish Ballads operates principally, if not wholly, as a visual entity, prefiguring what the twentieth century would come to term the “livre d’artiste” (Drucker 1-19). But as Buchanan-Brown has remarked, “the books which [Jones] designed and embellished for Murray are real books, and not simply specimens, however lovely, of chromolithography …. Unlike his own illuminated books, they really are books. A complete integration of text, illustration and decoration which satisfies the Romantic aspiration for Oriental or medieval richness, they yet remain eminently practical and readable objects” (Buchanan-Brown 149, 153).

What Buchanan-Brown means by a “complete integration of text, illustration and decoration” becomes clear from the moment we start reading Lockhart’s ballads themselves, all of which are printed conventionally in 8-point black type at the center of the page. But it also becomes quickly apparent that Jones’s designs sometimes serve as commentaries or re-readings of Lockhart’s texts, not simply affectless adornments of them, and in this respect they sometimes conflict with the accompanying illustrations. The very first poem, “The Lamentation of Don Roderick,” sets an elegiac tone for the collection as whole, evoking the loss and exhaustion of King Roderick, the last visigothic king of Spain, following the military overthrow of his reign by Moorish conquerors in the eighth century:

5-18His horse was bleeding, blind, and lame – he could no further go;

Dismounted, without pain or aim, the king stepped to and fro;

It was a sight of pity to look on Roderick,

For, sore athirst and hungry, he staggered, faint and sick.

All stained and strewed with dust and blood, like to some smouldering brand

Plucked from the flame, Rodrigo shewed: — his sword was in his hand,

But it was hacked into a saw of dark and purple tint;

His jeweled mail had many a flaw, his helmet many a dint…

He looked for the brave captains that led the hosts of Spain,

But all were fled except the dead, and who could count the slain?

Warren’s medievalesque illustration in black and white at the foot of the poem, depicting a disconsolate Rodrigo suicidally poised at the edge of a rocky crag, captures the mood of black despair hanging over the poem, which is on one level a lament for the subjugation of Christian Spain as much as the lament of Rodrigo himself (see fig. 12). But the imaginative claims of poem and illustration are considerably enriched, if not contradicted, when viewed in the context of Jones’s blue border (see fig. 13). In so far as the illustration is concerned, black ink is exploited by the engraver to represent the storm gathering in the valley below Rodrigo and to suggest an ominous atmosphere of death and destruction. Both poem and illustration, however, are encased in a border of bright blue (see fig. 14), the color of a storm-less sky, not a stormy one, lending the ballad a vitality absent from Lockhart’s original, and somewhat at odds with the poem’s elegiac tone. If this suggests that the poem’s fierce dialectic of life and death is enacted at the very surface of the page, such a suggestion is given further resonance by the stylized nature of the pattern employed on the decorative border, a pattern that Jones would later describe in his Grammar as Moorish or “Mauresque” (185-204). For the pattern suggests not only that the Moor’s defeat of Rodrigo is somehow re-enacted in the very design of the page but also that the Moors effectively re-invigorated a lifeless world through their importation of color, order and design. Decoration here makes claims on our attention that stand opposed to those made by illustration to “represent” the subject and ethos of the poem itself.

Figure 12

Henry Warren, wood engraving for “The Lamentation of Don Roderick” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 13

Owen Jones, wood-engraved border design for “The Lamentation of Don Roderick” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 14

Detail of Owen Jones, wood-engraved border design for “The Lamentation of Don Roderick” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

This dialectic between visual decoration and illustration or representation—between a polychromatic and a monochromatic vision of the world—is repeated time and again in Ancient Spanish Ballads, where poems and illustrations are frequently encased in borders of often startlingly bright hues, color-combinations, and patterning, and it is made all the more resonant by the underlying clash between Christian Europe and “Pagan” Orient barely concealed beneath the ballads’ surface. This dialectic becomes conspicuous again, for instance, upon reading “The Pounder,” a ballad positioned roughly mid-way through the section of historical ballads. Viewed narrowly, Lockhart’s ballad celebrates the unvanquishable spirit of the “Christians [who] have beleaguered the famous walls of Xeres,” such as “Don Alvar and Don Diego Perez, / And many other gentlemen, who, day succeeding day, / Give challenge to the Saracen and all his chivalry” (1-4). The ballad celebrates the heroism of Diego Perez, in particular, who, as Cervantes recorded in Don Quixote, is reputed to have continued slaughtering Moors and “Paynims” with an uprooted olive-tree even after his sword shivered and split in two:

9-20It fell one day when furiously they battled on the plain,

Diego shivered both his lance and trusty blade in twain;

The Moors that saw it shouted, for esquire none was near,

To serve Diego at his need with faulchion, mace, or spear.

Loud, loud he blew his bugle, sore troubled was his eye,

But by God’s grace before his face there stood a tree full nigh, —

An olive tree with branches strong, close by the wall of Xeres, —

“Yon goodly bough will serve, I trow,” quoth Don Diego Perez.

A gnarled branch he soon did wrench down from that olive strong,

Which o’er his head-piece brandishing, he spurs among the throng.

God wot ! Full many a Pagan must in his saddle reel ! —

What leech may cure, what beadsman shrive, if once that weight did feel.

Viewed in isolation, the poem contains little to suggest that Diego’s valor and expediency are unmerited; indeed, the poem closes with the words of Don Alvar celebrating his compatriot’s strength in perpetuity: “Sure mortal mould did ne’er enfold such mastery of power; / Let’s call Diego Perez THE POUNDER, from this hour” (23-4). But the illustration by Henry Warren that acts as a headpiece to the ballad (confusingly titled “Moorish Arms, etc,” according to the book’s Table of Contents) depicts the Pounder’s grave scene, his sword intact, and his other weapons now idle, of no use in fending off inevitable death. As with “The Lamentation of Don Roderick,” Warren’s illustration brings out an elegiac mood, derived from a reading of the ballad in its larger context, barely latent beneath the surface of Lockhart’s language. Like other antiquarian illustrations at this time, Warren’s illustration historicizes its subject, lending a Romantic futility to its hero’s actions.[34]

Figure 15

Henry Warren, “Moorish Arms, etc,” wood engraving for “The Pounder” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

But the darkness of Warren’s illustration is itself made to seem ironic when viewed in the context of Jones’s designs for border and tailpiece. For these restore to the poem a vitality and primal power absent from Warren’s illustration. This is partly a matter of the ink used for these devices, whose color (crimson) is traditionally associated with passion and blood. But it is a matter too of the stark geometry of Jones’s design, which contrasts sharply with the apparently random structure of Warren’s illustration (in which the accoutrements of battle are literally piled upon one another as if driven to obliterate the body buried beneath them). Where Warren’s illustration evokes decay and ruin, Jones’s border evokes order, system, and a world of restrained delight.

Figure 16

Owen Jones, wood-engraved border design and tail-piece for “The Pounder” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 17

Detail of Owen Jones, wood-engraved tail-piece for “The Pounder” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Despite the evident tensions between illustrations and decorations, there can be little doubt that John Murray intended Ancient Spanish Ballads to be continuous with his existing gift-book catalogue, offering readers a feast of masterfully executed illustrated work married to a new edition of a popular, late-Romantic, author. We have already witnessed how Murray advertised the work, on title-page and in advertisements, as containing numerous illustrations by eminent artists. The Table of Contents (in red) doubles as a List of Illustrations (in blue) (see fig. 7) and lists on a separate line, below each ballad’s title, the title of each illustration as well as the name of the artist by whom it was designed. As the absence of Jones’s name from this list would suggest—except for three occasions, on one of which Jones is identified purely as the illustrator of “the architecture”—“designed” effectively means “illustrated” in this instance, since it excludes Jones’s ornamental contributions, in the form of borders, tailpieces, etc. On one level at least, it seems clear, Ancient Spanish Ballads was intended to constitute a monument of picturesque illustration every bit the equal of those editions of Scott, Byron, Thomas Campbell and Samuel Rogers, illustrated by Turner, which had set the benchmarks for illustration at this date.

It is conspicuous, in this respect, that the 1841 edition of Ancient Spanish Ballads contains five full-page illustrations, engraved by S. Williams, from original drawings by the Scottish painter William Simson, separately leaved and titled, such as “The Penitence of Don Roderick” given a leaf to itself in the middle of the ballad of that title.[35] Modern critics find such hors-texte illustrations disruptive of the book’s overall unity (Buchanan-Brown 151; McLean 80; and Muir 154), and such illustrations are conspicuously absent from editions of the book published in the 1850s. Nonetheless, such illustrations are a noticeable feature of other illustrated books produced at this time, and they attest to Murray’s desire to produce a book continuous with the dominant strains in contemporary book illustration.

Figure 18

William Simson, wood-engraved illustration of “The Penitence of Don Roderick” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

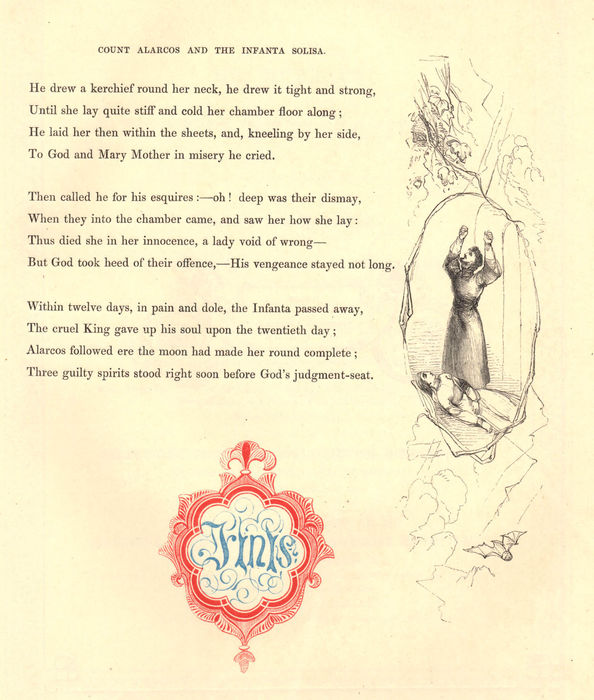

This desire can be witnessed too from the fact that many ballads contain multiple illustrations, such as “The Flight From Granada,” on which both Warren and Simson worked separately, or “Count Alarcos and the Infanta Solisa,” which contains no less than eight fore-margin panel illustrations by Harvey as well as an elaborate headpiece depicting the Infanta, thus representing a considerable investment of time and energy by an illustrator already much in demand at this time. (At least three engravers were also employed on the reproductions of Harvey’s designs for “Count Alarcos.”)[36] Even to talk of the latter as containing a series of illustrations, however, is to misrepresent the relation between the different elements of Harvey’s design as well as his tendency to represent a number of different scenes within the bounds of one illustration. For Harvey’s illustrations employ some of the same storytelling conventions as the ballad to “narrate” the story of Count Alarcos and his betrayal of his lovers. In the second panel (see fig. 19), for example, the Infanta weeps upon her father’s lap, at the top of design, telling him how Count Alarcos has broken his promise of marriage to her, while the bottom of the design represents Alarcos’s treacherous wooing of her in a flashback. Ensuing panels represent (among other events) the king’s injunction that Alarcos should murder his present wife and Alarcos’s dejection as he journeys to execute the king’s command (see fig. 20), Alarcos’s greeting by his present wife and children (see fig. 21), his announcement of her fate and her pleading (see fig. 22) for her own life, as well as the story’s tragic denouement (see fig. 23). To stress any one of these panels as illustrations is clearly to downplay their interdependency as a sequence, as well as their proto-filmic capacity to engage the mind as a narrative medium in their own right.

Figure 19

William Harvey, wood-engraved fore-margin panel for “Count Alarcos and The Infanta Solisa” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 20

William Harvey, wood-engraved fore-margin panel for “Count Alarcos and The Infanta Solisa” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 21

William Harvey, wood-engraved fore-margin panel for “Count Alarcos and The Infanta Solisa” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 22

William Harvey, wood-engraved fore-margin panel for “Count Alarcos and The Infanta Solisa” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 23

William Harvey, wood-engraved fore-margin panel for “Count Alarcos and The Infanta Solisa” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

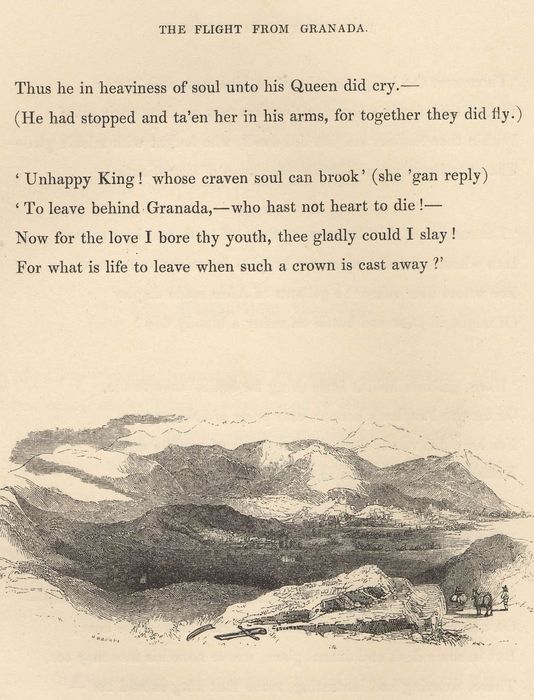

“The Flight From Granada” is interesting on a different score, since it shows how a number of different visual conventions are coming into collision within the confines of a single text. Even if we ignore the clash produced by Jones’s red crimson border, the illustration of the poem seems over-determined: its three, distinct, representational styles at odds with one another. The first illustration, far from being picturesque, is historical in orientation, collapsing a complex unfolding event into a single “moment” comprehensible as a unified, visual whole (see fig. 24). This illustration’s historical ambitions are declared in the titled scroll at the top, just beneath which the Moorish king Boabdil is depicted presenting the keys of the city to Ferdinand and Isabella. To their left, and in a sinuous curve bordering the left-hand margin, the Moors leave the city, advancing on foot towards the reader, the men in relatively full-face, the women veiled and faceless. On the opposite side of the page, in an equally sinuous curve to the right of Lockhart’s prefatory text, the Christian knights of Ferdinand and Isabella enter the city, many on horseback, only visible from the rear as they move slowly towards the gate situated to Ferdinand’s right. Two features of this illustration are especially interesting insofar as they deploy different pictorial conventions to produce historical effects. The first concerns the collapsing of space and time into one “pictorial” dimension; the gates of Granada through which Moors and Christians pass, on the right and left hands of the page, seem not to occupy the same spatio-temporal world as the scene of Boabdil presenting the keys to the city in the central vignette (crucially, a stylized scroll-like leaf separates these worlds). Or more literally, the opposed forces of Christianity and Islam seem to be engaging or disengaging the process of illustration itself insofar as the gates mark points of entry, or departure, into the central illustrative vignette. By the same token, the three distinct events depicted in the illustration—the flight of the Moorish citizens, the entry of the Christian conquerors, the formal capitulation of Boabdil to Ferdinand & Isabella—seem coterminous or simultaneous with one another. An event that must have taken place chaotically over hours, if not days (as well as miles rather than meters), is here shown to have passed—or rather, to be passing—in an instant.

Figure 24

Henry Warren, wood engraving and illumination for “The Flight From Granada” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Notwithstanding this collapsing of time and space, the illustration generates an uncanny sense of movement. We come away feeling that we have somehow literally perceived the scene of the Moors’ flight and the Christians’ conquest. This is partly a function of the page’s typography, resulting from the manner in which the sinuous border illustrations impinge, smoothly and continuously, upon the letterpress text so as to break up the regularity of the individual line. Far from being a static entity, Lockhart’s text—a prose preface to the ballad itself—is made to appear as if it were moving through space and time, its reader a traveler equally unmoored to any fixed point.

In contrast to Warren’s dynamic illustration of the flight from Granada, which is literally peopled with human activity, the picturesque vignette serving as a tailpiece to the ballad operates according to an entirely different set of conventions (see fig. 25). Everything here seems static, and signs of human activity are confined to the extreme bottom right of the scene, where a behatted peasant of indeterminate ethnicity and religion holds a cargo-laden donkey by the reins. The illustration is a self-consciously “picturesque” landscape scene or “view” and, as the title given to it in the book’s “Contents & List of Illustrations” indicates (“View of Granada from Ultimo Suspiro del Moro, Sketched on the Spot by Richard Ford, Esq.”), it claims to represent space with absolute fidelity. Where Warren’s depiction of the flight from Granada decenters or animates the text, stressing the mutual interdependence of reader, illustration, and text, Warren’s reproduction of Ford’s View recenters it, making Lockhart’s text appear to be an objective thing separate from the illustration itself.

Figure 25

Henry Warren, wood-engraved tailpiece to “The Flight From Granada” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Yet a third set of conventions governs Simson’s tinted full-page woodcut of Boabdil presenting the keys of the city to Ferdinand and Isabella, which, confusingly perhaps, carries the title “The Flight of Granada” beneath it (see fig. 26). This illustration too lays claim to represent a historical event, but it operates very differently from Warren’s similarly titled illustration. Space and time seem perfectly preserved here; but more importantly, the historicity of the central event is diminished by the scene’s apparent disconnection from any meaningful context—a disconnection thrown more sharply into relief by the picture’s seemingly arbitrary title. Differences in dress highlight racial and gender differences among the leading figures, but the historical import of the scene is undercut by its combination of intimacy and formality. Where the Moors are depicted standing or (in one case) abjectly kneeling, Ferdinand and Isabella are shown on horseback, their military forces standing erect. The central event of the illustration begs to be understood as a fundamentally human arrangement, a Victorian tableau in which the leading actors appear stiff and self-possessed, as if the transfer of the keys were a merely formal occasion.

Figure 26

William Simson, wood-engraved illustration of “The Flight From Granada” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

In the final event, it is not Warren’s and Simson’s illustrations in themselves that should concern us so much as the effect of them in combination with Lockhart’s poem, with one another, and with Jones’s borders. For in a crucial sense, all the illustrations to “The Flight from Granada” are discontinuous with the poem itself. Two of them operate beyond the red borders demarcating the poem’s boundaries (see figs. 27a and 27b), as headpiece and tailpiece merely, and the only one included within the poem’s borders—Warren’s reproduction of Ford’s “View” (see fig. 27b) —stresses the separateness of text from illustration, as has already been noted. They are all unquestionably illustrations to, or for, Lockhart’s poem. But saying they are illustrations of Lockhart’s poem seems more problematic.

Figure 27

a

b

By contrast, Jones’s borders appear integrated with Lockhart’s text while comprehending it as a totality (see fig. 27a and 27b). Their style and coloring are in keeping with the Moorish subject of the poem, which emphatically presents the Moors’ flight from Granada as a loss while making just one passing, indirect, allusion to the Castillan monarchs.[37] Where Warren’s and Simson’s illustrations highlight Ferdinand and Isabella as the Christian conquerors of Boabdil, Jones’s border-design, like the poem itself, presents the flight from Granada from a largely Moorish perspective.

Something similar is apparent from the way in which color-printed ornament sometimes interrupts or eclipses the black and white illustrations it is supposed to complement. One sees this in the way that the bright blues and reds of border designs and ornaments unsettle Harvey’s headpiece to “Dragut the Corsair,” for instance, or in the way that the closing device (“Finis”), printed in red and blue, punctuates the air of tragedy hanging over the final act of “Count Alarcos and the Infanta Solisa” (see fig. 23). One of the most dramatic and subtle examples of this tendency, however, comes in the tension between ornament (blue) and illustration (black and white) apparent in “The Song of the Galley.” Contemporary readers who were enthusiasts of art and illustration might well have skipped directly to this ballad, since it is one of just two illustrated by the eminent Scottish artist William Allan, R. A., President of the Royal Scottish Academy (see fig. 28). At first glance there is little to disturb the poignancy of Allan’s picturesque coastal scene titled “Maiden Watching the Galleys”. But it is interesting to speculate what might have been the reaction of Allan and his admirers to the tiny diapered decorative device in blue that Vizatelly has introduced into the center of the scene—in mid-ocean, as it were—between the ballad’s title and Lockhart’s short prefatory note (see fig. 29). For this decorative device, which occurs again near the beginning of other poems in the “Romantic Ballads” section, variously printed in blue, green, mauve, or yellow, unsettles Allan’s illustration in a number of ways. First and foremost, it reminds us that poem and illustration are fundamentally printed things, perhaps calling our attention too to the way in which the poem itself seems to “float” in space or water midway between the cliffs (on the left) and the departing galleys (on the right). In this sense, the device seems to occupy an entirely different geospatial dimension from that occupied by Allan’s work, destroying the habitual pictorial conventions by which black-and-white illustration operates in favor of a more phenomenologically accurate view of the page. But the device also operates as blue’s interruption of a monochrome world, and in this sense the device not only hints at the manner in which the poem will conclude on the verso—amidst an explosion of blue decorative bordering, with no remaining trace of illustration—but also carries hermeneutic implications for our understanding of Lockhart’s poem. “It is a narrow strait, / I see the blue hills over” (21-2), declares the maiden at one point towards the poem’s conclusion. The decorative device, midway up the “narrow strait” of the illustrated page, hints at a hopefulness already latent within the poem but perhaps missed by its sentimental illustrator.

Figure 28

William Allan, “Maiden Watching The Galleys,” wood-engraved illustration to “The Song of The Galley” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 29

Detail of Henry Vizatelly, blue wood-engraved diaper device for “The Song of The Galley” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

Figure 30

Owen Jones, wood-engraved decorative border of “The Song of The Galley” in Ancient Spanish Ballads: Historical and Romantic.

The intensity of “illustrative” energy represented by the representational engravings to such poems as “The Flight From Granada” and “Song of the Galley” clearly demonstrates the determination of Murray and others that the book should constitute a highly ornate, readable object. But Jones’s designs demonstrate a unique understanding of what such an object might be and how it might operate. And in this respect, they expose certain problems in the overall concept of the book embodied in the work of illustrators such as Warren, Simson, and Allan. For Warren, Simson and Allan, we might say, vision is supplemental to the poem itself; the latter constitutes simply the vehicle or occasion by which the artist represents or makes explicit what is merely latent within the poem. But for Jones vision is integral to the reading-experience, his decorations a constitutive element of the poem itself. As Dyce was to remark just one year later, representational art is a “figment” that “affords us pleasure” by suggesting something apart from itself (n.p.). Ornamental art, by contrast, is a “reality” that, so far as it goes, affords pleasure by its direct appeal to the senses. Or as Morris was to write fifty-one years later:

If we think the ornament is ornamentally a part of the book merely because it is printed with it, and bound up with it, we shall be much mistaken. The ornament must form as much a part of the page as the type itself, or it will miss its mark…. A mere black and white picture, however interesting it may be as a picture, may be far from an ornament in a book; while… a book ornamented with pictures that are suitable for that, and that only, may become a work of art second to none.

“The Ideal Book” 72-73

Paradoxically, the clash I am describing between illustration and ornament only throws into relief the absence of illustration from some of the ballads to be found in the Historical section, such as “The Complaint of the Count of Saldana” or “Bernardo and Alphonso,” for which gaps exist in the List of Illustrations under the heading “Designed by.” In the 1842 edition of Ancient Spanish Ballads, these gaps would be filled by Louis Haghe, Jones’s partner in the printing of The Alhambra. Insofar as the 1841 edition is concerned, however, these ballads exist as purely decorated entities, as if Jones’s conception of them somehow escaped the capacity of the illustrator.[38]

* * *

For at least one commentator at the time, the fitness I have been describing between Jones’s colored decorations and the poetry contained in Ancient Spanish Ballads was a marked feature of colour as a means of art; “Colouring is the decorative part of Art,” remarked the art educator Frank Howard in 1838, “It answers to rhythm and rhyme in poetry as the means of attracting the senses” (21). “The colourist may perhaps borrow from, as well as contribute something to, the poet,” agreed the color-theorist George Field (Chromatography 27). Howard’s assertion of an intrinsic connection between color and prosody is one with which William Blake would have agreed, and it foreshadows later collaborative experiments between poets and graphic artists determined to marry color-printing with poetry, such as Oscar Wilde’s and Charles Ricketts’s The Sphinx (printed in three colors in 1894) and Blaise Cendrars’s and Sonia Delaunay’s Prose Du Transsibérien (1913). “The word and its sound, form and its color, are vessels of a transcendental essence that we dimly surmise,” declares Johannes Itten with Heideggerian vigor; “as sound lends sparkling color to the spoken word, so color lends psychically resolved tone to form” (13). Colors are “primordial ideas,” he rhetorically affirms, “children of the aboriginal colorless light and its counterpart, colourless darkness” (13).

If there is a fitness between poetry and color, moreover, there is a particular fitness too between poetry and the decorative patterns bordering and surrounding Lockhart’s verse in Murray’s edition. In his study of the psychology of decorative art, Ernst Gombrich remarks that “pattern-making happens in time” (293), and argues that rhythm, or “the perception of order,” constitutes the basis of decoration: “The study of decoration … concerns a human activity [in] which … the sense of order is given free range in generating patterns of any degree of clarity or complication” (146). By Gombrich’s account, the decorative urge affects other arts than the strictly visual, and it perhaps comes as no surprise that analogies with music, poetry and writing permeate Gombrich’s text. Thus “both decorative art and poetry know of examples where … obedience to self-proclaimed rules blossomed into mastery” (Gombrich 291). For Gombrich, the very acts of reading and writing are premised upon a decorative urge, best witnessed perhaps in the mid-Victorian explosion of interest in medieval manuscript illumination and, most especially, in the spate of illuminated calligraphic manuscripts that William Morris generated for private ends in the 1860s and 1870s. “The sense of order which accounts for the appearance of the line and the page also enables the eye to pick out with the least effort the small deviations from regularity which constitute the distinctive features of characters, punctuation and paragraphing” (146).

Like Itten’s suggestion of an intrinsic connection between color and poetry, Gombrich’s account of the decorative urge driving writing and poetry suggests that Murray’s 1841 edition of Lockhart’s Ancient Spanish Ballads possesses interest not merely on literary grounds, nor as a touchstone of Victorian Moresque styling, nor for its undeniable achievement as a milestone in color-printing, but rather for its combination of all three of these elements. For perhaps more than any other book of its day, it brings us to a fuller consciousness of what Wilde was later to term “the material element of metrical beauty” (“Critic as Artist” 345). Through its designer’s usurpation of the textual position to which the illustrator and engraver had been elevated by the late 1830s, and its insistence upon Lockhart’s poems as thoroughly decorated entities, Ancient Spanish Ballads makes us conscious of the perceptual structures upon which poetry depends even in an age of so called free verse. As Wilde remarked elsewhere, poetry requires “architecture” as much as “melody” if it is to possess “that delightful sense of limitation which in all the arts is so pleasurable” (“[Poems By Henley and Sharp]” 91).

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Yale Center for British Art, and to Rachel Thomas, Asst. Curator of the John Murray Archive at the National Library of Scotland, for facilitating work on this essay.

Biographical Notice

Nicholas Frankel teaches English at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is the author of Oscar Wilde's Decorated Books (Univ. of Michigant Press, 2000) and of Masking The Text: Essays on Literature and Mediation in the 1890s (Rivendale Press, 2009). He is also a co-editor of Rice University Press’s new digital series “Literature By Design: British and American Books, 1880-1930.” His digital edition of The Sphinx, by Oscar Wilde with decorations by Charles Ricketts, will be appearing in this series in 2010, followed by two print editions of Wilde’s writings from Harvard University Press.

Notes

-

[1]

In the late 1830s, there was general agreement that British art education was in a sorry state, as well as a widespread fear that deficiencies in British art education would place British manufacturers at a disadvantage with their European competitors, especially the French. Underpinning such fears was a general recognition among manufacturers and legislators that industrial England was commercially reliant on developments in design. See Bøe 40-56, and Report from the Select Committee on Arts and Their Connexion with Manufactures.

-

[2]

Quoted respectively in Report from the Select Committee on Arts and Their Connexion with Manufactures, Part One 87, and Part Two 93 (Part One, containing a transcript of the 1835 session, and Part Two, containing the 1836 session, are separately paginated).

-

[3]

The phrase “pioneers of modern design” is borrowed from the title of Pevsner’s classic study.

-

[4]

The art of the ornamentist … ranks midway between fine art and art purely mechanical, and partakes of the nature of both …. The distinction drawn between ornamental art and fine art is made in reference to some object towards which each stands in some manner related …. But in regard to the beautiful … they labour in common ground.

Dyce, Introduction, [ n. p.).] -

[5]

Shasta M. Bryant writes that “Lockhart possessed a fairly large measure of poetic talent, but had little sense of obligation to his materials, and so did not hesitate to alter either the spirit or ideas of his sources. Consequently, while his poems are to be admired for their spirited style and artistic polish, more often than not they resemble original compositions rather than translations” (296).

-

[6]

The phrase “the Book of the Season, etc” is quoted by Smiles from an unpublished letter from Murray to Lockhart.

-

[7]

“Alas when the whole 2000 copies of which the edition consists are disposed of at the highest price which can be put upon them, they will not cover the expense” (Murray, Letter). Murray’s comment is born out by his firm’s account books, which reveal a final loss of £220, 16s/ 1d on the 1841 edition, notwithstanding total sales of £ 2993, 2s (Murray, Ledger). See also Murray’s remark to Jones, quoted above, that his principal motive in undertaking the work had been to secure for Lockhart’s translations “the publicity they merit and have not yet obtained.” Murray’s second edition (1842), the ledgers reveal, proved more profitable.

-

[8]

See Vivian, Spanish Scenery and Scenery of Portugal and Spain; Roberts, Views in Spain and Picturesque Sketches; and J. Lewis, Sketches of Spain and Sketches and Drawings. See also the series of “Landscape Annuals” with text by Thomas Roscoe and illustrations by David Roberts published by R. Jennings from 1835-38: The Tourist in Spain. Grenada, The Tourist in Spain. Andalusia, and The Tourist in Spain and Morocco. John Frederick Lewis “is usually called `Spanish Lewis’ to differentiate him from Frederick Christian Lewis, his father, who was an aquatinter” (C.T. Lewis 134). For J. Lewis’s representations or “views” of the Alhambra, see Gombrich 101-2.

-

[9]

Among other differences, the editions of 1856 and 1859 contain slightly less illustrative matter and a consequent elevation of decorative design, especially insofar as page borders are concerned.

-

[10]

See Hay; Field, Chromatics and Chromatography; Chevreul; Benson; and Keyser.

-

[11]

On one occasion, Owen Jones wrote to Murray enclosing a copy of a book (possibly Hay’s Laws of Harmonious Colouring) annotated by George Field, the author of Chromatics and Chromotography, in order to show how much Hay was indebted to Field for his ideas about color. “The knowledge and ideas come from Field,” Jones remarked, while “Hay is only responsible for the particular form in which the ideas are expressed” (Jones, Letter to John Murray. 28 May 1857).

-

[12]

Of the 1857 English edition of Chevreul’s The Laws of Contrast of Colour, Joan Friedman remarks, “Spanton’s translation was not only the first English edition of Chevreul’s treatise, but it was also the first English application of color printing to a book actually about color” (38).

-

[13]

“It is … a remarkable book, and it is certain that nothing like the colour plates had ever been seen before” (McLean 38). As McLean explains, although it was a technological and artistic success, Baxter’s book was a commercial failure owing to the untimely death of its dedicatee (King William IV) just prior to publication as well as Baxter’s tardiness in getting the book ready for the Christmas market.

-

[14]

“It is not entirely clear why Jones settled on chromolithography,” says Friedman (51). Friedman speculates that Jones “knew of work in chromolithography being done on the Continent, particularly by Godefroi Englemann in Paris” (52). For the relation between Jones’s decorative theories and the medium of chromolithography, see Frankel.

-

[15]

“Books in Press, March 1841” (n.p.), bound together with the third volume of J.G. Wilkinson’s A Second Series of the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, Including Their Religion, Agriculture, &C. Derived from a Comparison of the Paintings, Sculptures, and Monuments Still Existing, with the Accounts of Ancient Authors. Some copies of Murray’s second edition of Ancient Spanish Ballads (1842), published with revised page designs as well as additional illustrations by Louis Hague, carry prospecti for The Alhambra bound in with Murray’s own advertisements at the book’s end. The Yale Center for British Art possesses a copy of Murray’s second edition containing a decorated prospectus in red, blue, and black for Volume 1 of The Alhambra, followed by a second, similarly decorated, prospectus advertising Part One of Volume 2 of The Alhambra. It is telling that the architectural pretensions embodied in Volume One of The Alhambra (properly titled Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra) are dropped from Volume 2—titled merely Details and Ornaments from the Alhambra—which consequently stresses the purely decorative character of the work. Volume Two also omits the name of Jones’s original collaborator, Jules Goury, while elevating Jones’s name and profession to a position of greater prominence.

-

[16]

On 12 Feb. 1841, Jones wrote to Murray that “we are now finishing the printing of Wilkinson’s plates” and requesting permission to print a further 500 plates above and beyond the 1500 plates that had been initially required; “they would not of course form an account till you required them,” wrote Jones, “but if they are ever likely to be wanted, I would rather do them now that the man is used to the stones” (Jones, Letter to John Murray. 12 Feb. 1841).

-

[17]

Unlike the other illustrators of Ancient Spanish Ballads, Allan and Roberts were both members of the Royal Academy, known especially for their watercolors and lithographs. That they were engaged principally so as to lend an air of respectability and legitimate artistry to the project seems indisputable from the low number of illustrations they were commissioned to produce; where Harvey and Warren contributed 29 and 27 illustrations respectively, Allan’s and Roberts’s combined contribution was three.

-

[18]