Abstracts

Abstract

Rural residents can incur substantial travel-related costs to receive needed care. In this study, we describe and compare the medical travel programs offered by provincial and territorial governments. We conducted a document analysis of medical travel subsidy programs available in Canada to the general public. Only programs funded and administered by provincial/territorial governments were included. Based on the information that we collected, we determined there were three types of programs. Discount programs (BC) allow eligible patients to receive reduced or waived prices for travel and lodging at designated providers. Non-reimbursement programs (BC, SK) cover the costs of travel and lodging without requiring patients to pay for costs up-front. In reimbursement programs (MB, ON, QC, PEI, NS, NL, YK, NWT, NT), patients generally pay costs up-front and then submit claims for reimbursement after receiving the health service. Rates, co-payments, and maximum allowable amounts vary by program. Our findings indicated that although many provinces and territories offer medical travel subsidy programs, the availability, terms, and conditions vary widely. The study highlights regional disparities that may contribute to inequitable access to care across Canada.

Keywords:

- Medical travel,

- health care expenses,

- rural,

- subsidies,

- provincial and territorial programs

Résumé

Les résidents en milieu rural peuvent cumuler des frais de déplacement substantiels pour se faire soigner. Dans la présente étude, nous décrivons et comparons les programmes de transport pour raison médicale offerts par les gouvernements provinciaux et territoriaux. Nous avons mené une analyse documentaire des programmes de subvention des déplacements pour soins médicaux dont peut bénéficier la population au Canada. Seuls les programmes financés et gérés par les gouvernements provinciaux ou territoriaux ont été retenus. À partir de cette analyse, nous avons déterminé qu’il existe trois types de programmes. Il y a les programmes de rabais (C.-B.), qui accordent aux patients admissibles des rabais ou une dispense sur les frais de voyage et de logement chez des fournisseurs désignés. Il y a les programmes de non-remboursement (C.-B., Sask.), qui couvrent les frais de déplacement et de logement sans que le patient ait à les payer initialement. Enfin, il y a les programmes de remboursement (Man., Ont., Qc, Î.-P.-É., N.-É., T.-N., Yn, T. N.-O., Nt), qui exigent généralement que le patient paie les frais puis soumette une demande de remboursement une fois qu’il a été soigné. Le taux de remboursement, la quote-part et les montants admissibles maximaux varient d’un programme à l’autre. Nous avons constaté que, même si bien des provinces et territoires ont des programmes de subvention des déplacements pour soins médicaux, il y a de grandes différences parmi ceux qui sont offerts et leurs modalités. Cette étude fait ressortir des disparités régionales qui pourraient contribuer aux iniquités en matière d’accès aux soins à l’échelle du Canada.

Mots-clés :

- Frais de déplacements pour soins médicaux,

- rural,

- subventions,

- programmes provinciaux et territoriaux

Article body

Travelling long distances to access health services is a reality for residents of rural communities. In addition to the time and inconvenience of travel, rural residents can incur substantial travel-related costs to access and receive needed care. Several studies have described the travel and lodging costs for various health services including cancer care (Cohn, Gooenough, Foreman, & Suneson, 2003; Howard et al., 2014; Lauzier et al., 2011; Lightfoot et al., 2005; Longo & Bereza, 2011; Longo, Deber, Fitch, Williams, & D’Souza, 2007; Longo, Fitch, Deber, & Williams, 2006; Martin-McDonald, Rogers-Clark, Hegney, McCarthy, & Pearce, 2003; Mathews, Buehler, & West, 2009; Mathews, West & Buehler, 2009; Zucca, Boyes, Newling, Hall, & Girgis, 2011), primary healthcare (Wong & Regan, 2009), abortion services (Sethna & Doull, 2007), and prenatal and maternity services (Fry, Cartwright, Huang, & Davies, 2003; Kornelsen & Grzybowski, 2006) in Canada and Australia where residents may live considerable distances away from regional and tertiary care centres. Longo et al. (2006) found out-of-pocket costs posed a “significant or unmanageable” financial burden for roughly one fifth (20.4%) of cancer patients surveyed in Ontario, and that the costs related to travel were greater than the costs of all other out-of-pocket costs combined (Longo et al., 2007). Patients’ travel expenses may grow as provinces consolidate and centralize health services.

Travel-related, out-of-pocket costs have been suggested to contribute to “distance decay” effect, specifically, that health service utilization decreases with increasing distance (Wong & Regan, 2009). For example, researchers have described travel costs as a barrier to rural residents accessing dental care (Curtis, Evans, Sbaraini, & Schwartz, 2007), paediatric speech pathology services (O’Callaghan, McAllister, & Wilson, 2005), specialist care (Wong & Regan, 2009), and cancer care (Howard et al., 2014; Mathews, Buehler et al., 2009; Mathews, West et al., 2009; Watanabe et al., 2013; Zucca et al., 2011). Moreover, high travel costs have been shown to negatively affect participation in cancer care clinical trials (Sabesan et al., 2011) and cardiac rehabilitation programs in Australia (De Angelis, Bunker, & Schoo, 2008). Rural cancer patients are more likely to view travel costs as an important consideration when making treatment decisions (Mathews, Buehler et al., 2009; Mathews, West et al., 2009).

The use of technology, alternate care delivery programs, as well as government, private, and charitable subsidy programs may help reduce the barriers created by travelling. For example, a number of studies have noted the potential cost savings to patients when care is provided closer to home through initiatives such as rural visiting surgical specialist programs (Rankin et al., 2001), different forms of prostate cancer treatment (Sethukavalan et al., 2012), hemodialysis delivered in satellite centres (Diamant et al., 2010), and tele-health services (Elford et al., 2001; Loh et al. 2013; Thaker, Monypenny, Olver, & Sabesan, 2013; Watanabe et al., 2013). A study of veterans in the United States found that following increases in travel reimbursement rates, reimbursement-eligible veterans were more likely to use outpatient services, and use more of these services (Nelson, Hicken, West, & Rupper, 2012). Researchers in Canada have noted the importance of government-funded travel programs (Lightfoot et al., 2005; Longo et al., 2007; Mathews, Buehler et al., 2009; Mathews, West et al., 2009), lodging, and volunteer driver programs offered by charitable organizations (Lauzier et al., 2011) in alleviating patients’ out-of-pocket costs.

Social workers play a key role in helping patients to lessen the burden of these expenses. Social workers assess patients’ financial needs, provide financial counselling, and inform patients about government, industry, and charitable programs (Levy & McCourt, 2015; Mellace, 2010; Prutting, Cerveny, MacFarlane, & Wiley, 1998; Smith, Nicolla, & Zafar, 2014). They also assess patient eligibility for assistance programs, and assist patients in completing and compiling the documentation required to take advantage of these programs. Social workers will often highlight a patient’s financial concerns and facilitate discussions between the patient and other members of the health care team (Alexander, Casalino, Tseng, McFadden, & Meltzer, 2004; Levy & McCourt, 2015).

In Canada, travel and related costs fall outside the provincial/territorial universal public health insurance program (“Medicare”), which covers the costs of all medically necessary treatment provided in hospitals and physician services provided in community and institutional clinics. To alleviate the financial burden posed by travel, many provinces and territories offer programs to transport patients and/or cover some or all of the costs related to travel for medical care. However, the availability and terms and conditions of these programs vary widely. In this study, we describe and compare the medical travel programs offered by provincial governments. This study describes publicly-funded programs aimed at improving access to care for residents of rural and remote communities. It highlights regional disparities that may contribute to inequitable access to care across Canada. The study responds to the need for current and comparative information about financial assistance programs available to patients (Smith et al., 2014).

Methods

We conducted a document analysis to describe and compare medical travel subsidy programs available in Canada. Only programs funded and administered by provincial/territorial governments were included in this study. We did not include programs by hospitals, regional health authorities, charitable organizations, or private firms. Moreover, since we were interested in programs available to any resident in the province, we excluded programs offered exclusively to individuals receiving income support (i.e. social assistance), or that were offered on the basis of employment (e.g. RCMP, veterans), or aboriginal status (Non-Insured Health Benefits Program).

To identify programs, we consulted the websites of provincial/territorial governments and health ministries. We also directly contacted health ministry officials to inquire about these programs. For each program, we gathered information on terms and conditions including eligible applicants (patients and escorts), services, and expenses. Program data were collected in French and English. Once preliminary data were gathered, a research assistant verified the data with a program official. These consultations included telephone interviews and email correspondence, and took place in May 2014.

We summarized the data for each of these attributes and, where applicable, used descriptive statistics to characterize numeric data. In the tables, the term “not available” was used to indicate information the program contact did not know, or could not provide and/or verify.

Results

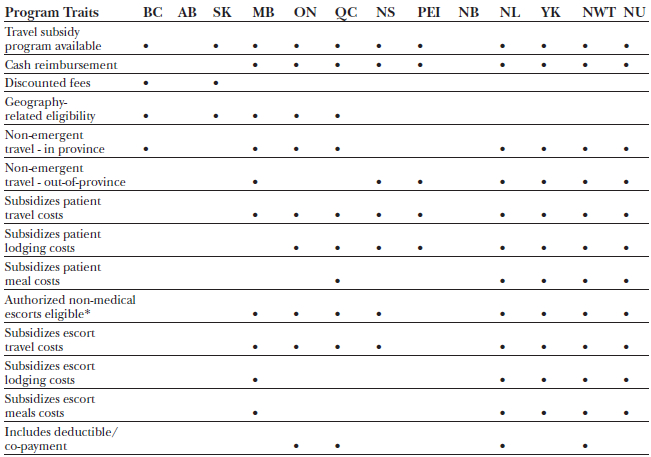

We found 14 government-funded programs that met the eligibility criteria (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2013a, 2013b; Government of Saskatchewan Health, 2012; Health PEI, n.d.; Manitoba Health, 2014a, 2014b; Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Health and Community Services, n.d.; Northwest Territories Health and Social Services, n.d.; Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, 2013; Nunavut Department of Health, n.d.(a), n.d.(b); Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2009-2010; Services Quebec, 2003; Yukon Health and Social Services, 2014). All but two of the provinces and territories (Alberta and New Brunswick) offered some program to alleviate travel and related displacement costs (Table 1). Where available, the programs varied considerably in terms of the nature of subsidy, eligibility of patients, nature of eligible travel, types of costs subsidized, and level of subsidy. While all programs allowed for costs related to escorting minors, escorts for adult patients for non-medical reasons (e.g. translation) were permitted only with authorization (usually by referring physicians). Further details of the terms and conditions of each program are described below.

Table 1

Summary of Availability and Conditions of Medical Travel Programs in Canada

*– for adult patients; BC – British Columbia, MB – Manitoba, ON – Ontario, QC – Quebec, NS – Nova Scotia, PEI – Prince Edward Island, NL – Newfoundland and Labrador, YK – Yukon, NWT – Northwest Territories, NU – Nunavut

There were three types of government-based programs: Discount, non-reimbursement, and reimbursement (Table 2). Discount programs, like the one offered by British Columbia (BC Travel Assistance Program), allowed eligible patients to receive discounted and in some instances waived prices, for travel and lodging through designated providers. No money is provided to patients and/or their escorts who must pay-out-of pocket for these services. Non-reimbursement programs covered the costs of travel and lodging without requiring the patient or their escort to pay for costs up-front. Reimbursement programs provided patients and/or their escorts funding to cover some or all of their eligible travel and lodging expenses. In these programs, patients and escorts generally paid costs up-front and would then submit claims for reimbursement after receiving the health service.

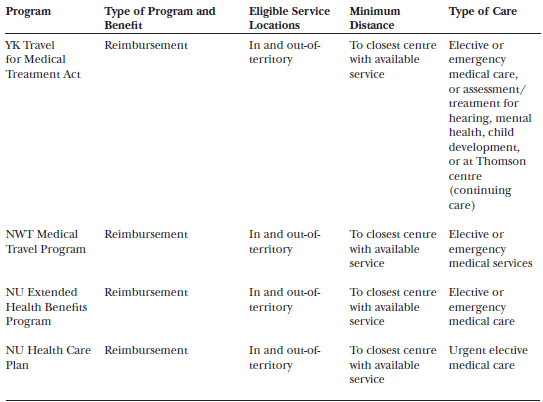

Table 2

Medical Travel Program Type and Service-Related Eligibility Criteria

BC – British Columbia, MB – Manitoba, ON – Ontario, QC – Quebec, NS – Nova Scotia, PEI – Prince Edward Island, NL – Newfoundland and Labrador, YK – Yukon, NWT – Northwest Territories, NU – Nunavut; km – kilometre; NIHB – Non-Insured Health Benefits; “not available” – the program contact did not know, provide and/or verify the requested information.

All programs covered provincial/territorial residents with provincial health insurance coverage (i.e. held a provincial health insurance number/card). In addition, the programs were considered to be measures of “last resort.” Patients covered by employer insurance, private insurance, or other government programs were not generally eligible for these government-based programs, except, in some cases, where their benefits had been exhausted or programs were complementary. While the majority of programs included in-province/territory travel, those for Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island consisted of out-of-province travel exclusively, with additional minimum distance or service criteria (Table 2). While the nearest healthcare centre was the requirement for most programs, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia stipulated minimum travel distances. Primary care, including routine lab and diagnostic services, were not covered under any of the programs. Only services covered under provincial health insurance plans were eligible for these programs. As a result, patients seeking experimental care were not eligible. The Saskatchewan Northern Medical Transportation Program covered emergency care only, while Prince Edward Island’s program was limited to patients requiring specific types of transplants (Prince Edward Island Transplant Surgery Out-of-Province Travel and Accommodation Assistance).

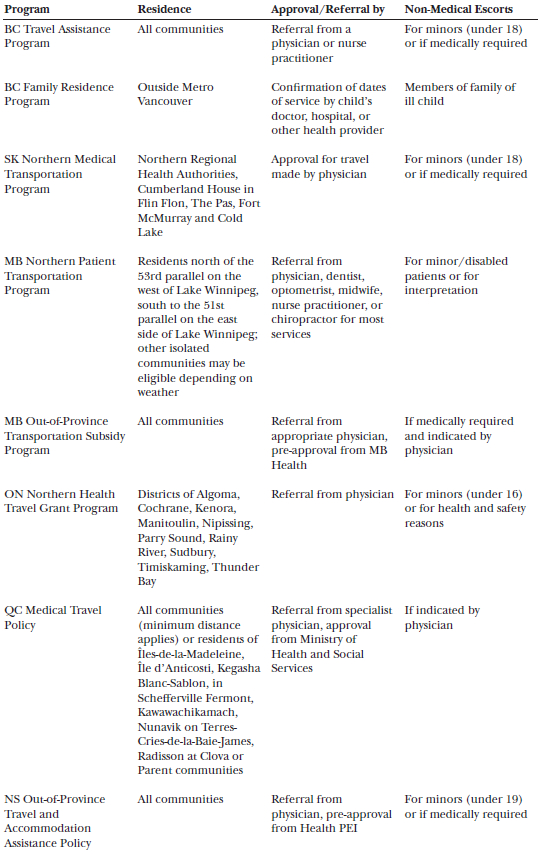

Table 3

Medical Travel Program Applicant-Related Eligibility Criteria

BC – British Columbia, MB – Manitoba, ON – Ontario, QC – Quebec, NS – Nova Scotia, PEI – Prince Edward Island, NL – Newfoundland and Labrador, YK – Yukon, NWT – Northwest Territories, NU – Nunavut; km – kilometre; NIHB – Non-Insured Health Benefits; “not available” – the program contact did not know, provide and/or verify the requested information.

Five programs stipulated specific community or regional residency requirements, in addition to minimum travel distance requirements (if applicable), while other programs were available to all eligible provincial/territorial residents (Table 3). All programs were available to adult and paediatric patients except British Columbia’s Family Residence Program, which was available exclusively to the families of paediatric patients. Two programs (Prince Edward Island Transplant Surgery Out-of-Province Travel and Accommodation Assistance and Nunavut Extended Health Benefits) also had patient-related health condition and /or age criteria. While all programs required some form of documentation (referral, approval or completion of eligible forms by a healthcare provider), some required program-specific approval prior to travel/receipt of service. Out-of-province travel, where eligible, generally required a referral from the specialist physician and additional approval. All but one program (Prince Edward Island Transplant Surgery Out-of-Province Travel and Accommodation Assistance) (Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, 2013) permitted non-medical personnel as escorts, although only a minority permitted escorts for social reasons (upon physician recommendation).

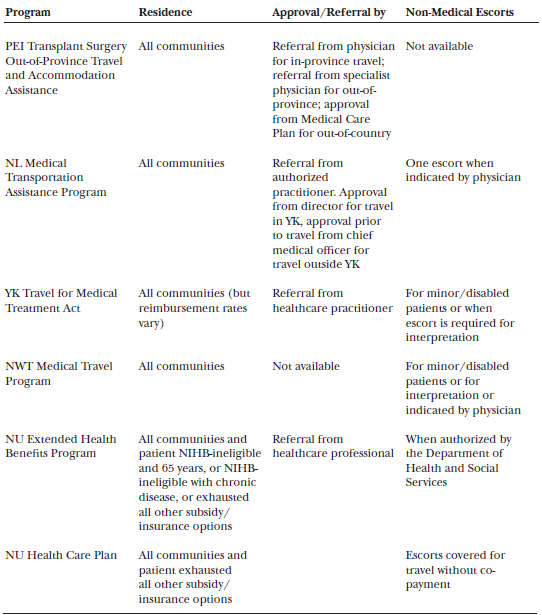

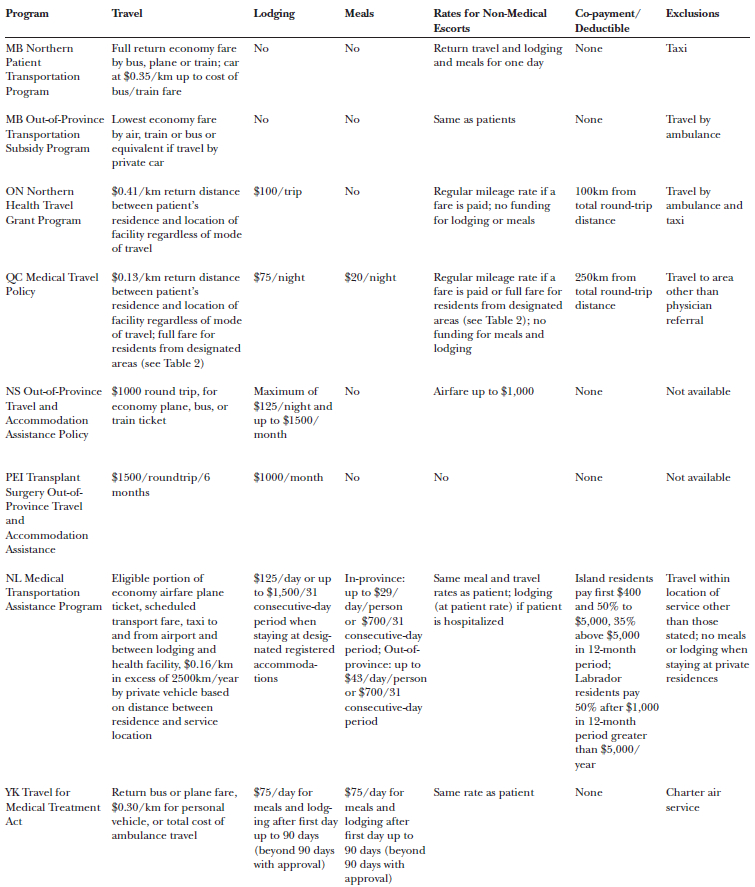

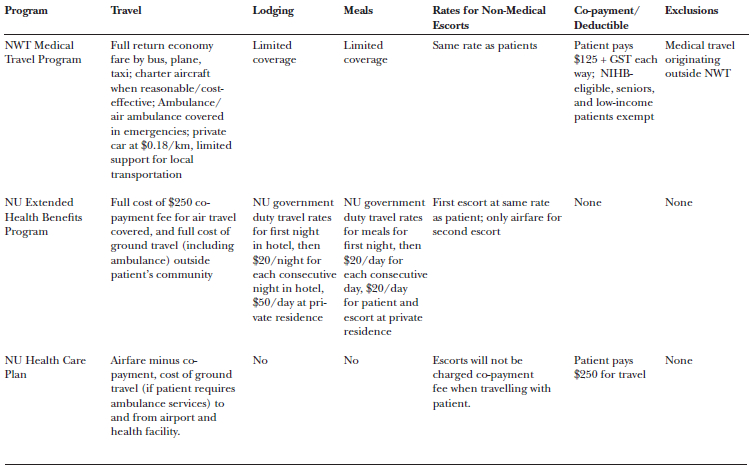

Table 4

Eligible Expenses and Rates for Reimbursement-Type Medical Travel Programs

BC – British Columbia, MB – Manitoba, ON – Ontario, QC – Quebec, NS – Nova Scotia, PEI – Prince Edward Island, NL – Newfoundland and Labrador, YK – Yukon, NWT – Northwest Territories, NU – Nunavut; km – kilometre; NIHB – Non-Insured Health Benefits; “not available” – the program contact did not know, provide and/or verify the requested information.

Reimbursement programs varied in their coverage of travel and related costs, with some programs specifying eligible modes of transportation and not all programs covering the full costs of transportation (Table 4). For example, Ontario provided a reimbursement amount of $0.41/km based on road distance between the patients’ community of residence and the health facility, after a 100km deductible. Seven of the ten reimbursement programs included lodging and only four specifically included meals (sometimes included in the rate allowed for lodging). For escorts, travel costs were allowed only if an additional fare was paid (that is, not if the patient and escort travelled together in a car). Escort lodging costs were allowed only if the patient was hospitalized, otherwise programs expected the escort and patient would share lodging. With the exception of Quebec, programs that allowed meal costs for patients also allowed meal costs for escorts. Five of the ten programs (Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nunavut Health Care Plan) had deductible or co-payments.

Discussion

Medical travel-related costs disproportionately affect lower socio-economic groups, particularly the “working poor” who earn too much income to qualify for income support. Costs related to medical travel consume a larger share of disposable income than in high-income groups. These disparities are magnified for rural residents who, compared to their urban counterparts, earn lower incomes (Canadian Population Health Initiative, 2006; Singh, 2002), are less likely to have private health insurance (Mathews, West et al., 2009), and have poorer health status and more chronic conditions (Canadian Population Health Initiative, 2006). Despite the potential of medical travel subsidy programs to redress these inequities, the provinces and territories varied in their approach to alleviating patients’ travel-related costs, with two provinces (Alberta and New Brunswick) offering no program whatsoever. All provinces and territories encouraged residents to avail of other programs offered through other provincial/territorial departments, the federal government (including tax rebates), employers, private insurance policies, private companies, and charitable organizations. Many of the provincial/territorial programs partnered with other agencies, often identifying these organizations as designated providers.

While most provinces offered programs to reimburse patients’ out-of-pocket costs, British Columbia (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2013a, 2013b) and Saskatchewan (Government of Saskatchewan Health, 2012) offered programs that covered the costs of services or facilitated price discounts, with no monies going directly to patients. The majority of programs offered by provincial and territorial governments provided reimbursement after patients had incurred out-of-pocket expenses. The initial outlay of monies to cover the costs of care may pose a substantial barrier for some patients. Some programs such as Newfoundland and Labrador’s “50% pre-payment of economy airfare” option may help reduce the up-front costs faced by patients (Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Health and Community Services, n.d.). None of the programs aimed to cover all out-of-pocket travel-related expenses borne by patients. Even programs that, on first glance, covered a wide range of items for patients and escorts only reimbursed a portion of these costs. All programs (including those offered by non-government organizations) require documentation, referrals, and in some cases, pre-approval.

Patients must be aware of terms and conditions in order to benefit fully from these programs. They must be diligent in keeping receipts, seeking written referrals and approvals, and submitting necessary documentation within stated timelines. Social workers work closely with individual patients to help them avail of these programs, by referring patients to various programs, counselling patients on how to arrange personal finances to qualify for programs, and/or assisting patients with completing forms (Levy & McCourt, 2015; Smith et al., 2014). Social workers have noted the difficulty in keeping current of available programs and their eligibility and documentation requirements and have called for updated and complete listings of available resources (Smith et al. 2014).

Studies have shown that few patients who face conditions with potentially high out-of-pocket costs were aware of financial assistance programs. For example, surveys of cancer patients show that only a minority of patients were aware of financial assistance programs or believed the programs were well advertised (Longo & Bereza, 2011; Longo et al., 2006; Longo et al., 2007; Mathews, Buehler et al., 2009; Mathews, West et al., 2009; Mellace, 2010). Patients may not be fully aware of the cost implications of their condition when they are initially diagnosed and may become more concerned about out-of-pocket costs as they incur an ever-growing amount of expenses. These studies have highlighted the need to educate patients about financial assistance programs at multiple points during their diagnosis and treatment. Although social workers play a key role in helping cancer patients address financial concerns, a US survey of oncology social workers found only one third of patients actually see a social worker for these concerns (Mellace, 2010).

Limitations

This study is the first to describe medical travel assistance programs in Canada. We took a number of steps to ensure the completeness and validity of the data, including verifying data against original sources and re-confirming information associated with each program. Given that terminology used to describe the programs varies across Canada, it is possible that, despite our efforts, some programs may not have been identified and included in the analysis.

Conclusion

All of Canada’s provinces and territories, except Alberta and New Brunswick, offer programs to alleviate the costs related to travel for medical care. These programs include discount programs that provide patients with access to lower prices, non-reimbursement programs that provide patients with travel and lodging without paying out-of-pocket, and reimbursement programs that allow patients to recoup a portion of out-of-pocket costs. The availability and terms and conditions of these programs vary widely. The study highlights regional disparities that may contribute to inequitable access to care across Canada.

Appendices

Biographical note

Maria Mathews is a professor, and Dana Ryan a research assistant, in the Faculty of Medicine at Memorial University.

Bibliography

- Alexander, G. C., Casalino, L. P., Tseng C.-W., McFadden D., & Meltzer, D. O. (2004). Barriers to patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. Journal of General Internal Medicine,19, 856-860.

- British Columbia Ministry of Health. (2013a). Family residence program. Retrieved from http://www.bcfamilyresidence.gov.bc.ca/

- British Columbia Ministry of Health. (2013b). Travel assistance program. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/tapbc/tap_patient.html

- Canadian Population Health Initiative. (2006) How healthy are rural Canadians? An assessment of their health status and health determinants. Canadian Institute for Health Research: Ottawa. Retrieved from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/rural_canadians_2006_report_e.pdf

- Cohn, R. J., Gooenough, B., Foreman, T., & Suneson, J. (2003). Hidden financial costs in treatment for childhood cancer: An Australian study of lifestyle implications for families absorbing out-of-pocket expenses. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 25(11), 854-863.

- Curtis, B., Evans, R.W., Sbaraini, A., & Schwartz, E. (2007). Geographic location and indirect costs as a barrier to dental treatment: A patient perspective. Australian Dental Journal, 52(4), 271-278.

- De Angelis, C., Bunker, S. & Schoo, A. (2008). Exploring the barriers and enablers to attendance at rural cardiac rehabilitation programs. Australian Journal of Rural Health,16, 137-142. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2008.00963.x

- Diamant, M. J., Harwood, L., Movva, S., Wilson, B., Stitt, L., Lindsay, R. M., & Moist, L. M. (2010). A comparison of quality of life and travel-related factors between in-centre and satellite-based hemodialysis patients. ClinicalJournal of the American Society of Nephrology, 5, 268-274. doi:10.2215/CJN.05190709

- Elford, D. R., White, H., St John, K., Maddigan, B., Ghandi, M., & Bowering, R. (2001). A prospective satisfaction study and cost analysis of a pilot child telepsychiatry service in Newfoundland. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 7, 73-81. doi:10.1258/1357633011936192

- Fry, M. J., Cartwright, D. W., Huang, R. C., & Davies, M. W. (2003). Preterm birth a long distance from home and its significant social and financial stress. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gyneaecology, 43, 317-321. doi:10.1046/j.0004-8666.2003.00092.x

- Government of Saskatchewan Health. (2012). Northern medical transportation program. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.sk.ca/northern-medical-transportation-program

- Health PEI. (n.d.). Transplant surgery out-of-province travel and accommodation assistance. Retrieved from http://www.healthpei.ca/index.php3?number=1035143&lang=E

- Howard, A. F., Smillie, K., Turnbull, K., Chelan, Z., Munroe, D., Ward, A., ...Olson, R. (2014). Access to medical and supportive care for rural and remote cancer survivors in Northern British Columbia. Journal of Rural Health, 30(3): 311-21. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12064

- Kornelsen, J., & Grzybowski, S. (2006). The reality of resistance: The experiences of rural parturient women. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 51(4), 260-265. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.02.010

- Lauzier, S., Levesque, P., Drolet, M., Coyle, D., Brisson, J., Mâsse, B., ...Maunsell, E. (2011). Out-of-pocket costs for accessing radiotherapy among Canadian women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(30), 4007-4013. doi:10.1093/jnci/djs512

- Levy, J., & McCourt, M. (2015). Chapter 89: Bridging increasing financial gaps and challenges in service delivery. In G. H. Christ, C Messner, & L. Behar (Eds.), Handbook of oncology social work: Psychosocial pare for People with cancer (pp. 667-672). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Lightfoot, N., Steggles, S., Gauthier- Frohlick, D., Arbour-Gagnon, R., Conlon, M., Innes, C., ...Merali, H. (2005). Psychological, physical, social and economic impact of travelling great distances for cancer treatment. Current Oncology, 12(4). Retrieved from http://www.current-oncology.com/index.php/oncology/article/viewFile/80/50

- Loh, P. K., Sabesan, S., Allen, D., Caldwell, P., Mozer, R., Komesaroff, P. A., … Royal Australasian College of Physicians Telehealth Working Group. (2013). Practical aspects of telehealth: Financial considerations. Journal of Internal Medicine, 43, 829-834. doi:10.1111/imj.12193

- Longo, C. J., & Bereza, B. G. (2011). A comparative analysis of monthly out-of-pocket costs for patients with breast cancer as compared with other common cancers in Ontario, Canada. Current Oncology, 18(1),1-8.

- Longo, C. J., Deber, R. B., Fitch, M., Williams, A. P., & D’Souza, D. (2007). An examination of cancer patients’ monthly out-of-pocket costs in Ontario, Canada. European Journal of Cancer, 16, 500-507. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00783.x

- Longo, C. J., Fitch, M., Deber, R. B., & Williams, A. P. (2006). Financial and family burden associated with cancer treatment in Ontario, Canada. Supportive Care in Cancer, 14, 1077-1085. doi:10.1007/s00520-006-0088-8

- Manitoba Health. (2014a). Northern patient transportation program. Retrieved from https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/ems/nptp.html

- Manitoba Health. (2014b). Out-of-province transportation subsidy program. Retrieved from http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/mhsip/travel.html

- Martin-McDonald, K., Rogers-Clark, C., Hegney, D., McCarthy, A., & Pearce, S. (2003). Experiences of regional and rural people with cancer being treated with radiotherapy in a metropolitan centre. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9, 176-182. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00421.x

- Mathews, M., Buehler, S. K., & West, R. (2009). Perceptions of health care providers concerning patient and health care provider strategies to limit out-of-pocket costs for cancer care. Current Oncology, 16(4), 3-8. Retrieved from http://www.current-oncology.com/index.php/oncology/article/view/375/359;

- Mathews, M., West, R., & Buehler, S. K. (2009). How important are out-of-pocket costs to rural patients’ cancer care decisions? Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 14(2), 54-60.

- Mellace, J. (2010). The Financial Burden of Cancer Care. Social Work Today, 10(2), 14-16.

- Nelson, R. E., Hicken, B., West, A., & Rupper, R. (2012). The effect of increased travel reimbursement rates on health care utilization in the VA. Journal of Rural Health, 28, 192-201. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00387.x

- Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Health and Community Services. (n.d.). Medical transportation assistance program. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/mcp/travelassistance.html

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. (n.d.). Medical travel program. Retrieved from http://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/health/nwt-health-care-plan/medical-travel

- Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness. (2013). Out-of-province travel and accommodation assistance policy. Retrieved from http://novascotia.ca/DHW/Travel-and-Accommodation-Assistance/

- Nunavut Department of Health. (n.d.)(a). Extended health benefits program. Retrieved from http://gov.nu.ca/health/information/medical-travel-extended-health-benefits

- Nunavut Department of Health. (n.d.)(b). Health care plan. Retrieved from http://gov.nu.ca/health/information/medical-travel-nunavut-health-care-plan

- O’Callaghan, A. M., McAllister, L., & Wilson, L. (2005). Barriers to accessing rural paediatric speech pathology services: Health care consumers’ perspectives. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 13, 162-171. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1854.2005.00686.x

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. (2009-2010). Northern health travel grant program. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/publications/ohip/northern.aspx

- Prutting, S. M., Cerveny, J. D., MacFarlane, L. L., & Wiley, M. K. (1998). An Interdisciplinary Effort to Help Patients With Limited Prescription Drug Benefits Afford Their Medication. Southern Medical Journal, 91(9), 815-820.

- Rankin, S. L., Hughes-Anders, W., House, A. K., Heath, D. I., Aitken, R. J., & House, J. (2001). Costs of accessing surgical specialists by rural and remote residents. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 71, 544-7. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02188.x

- Sabesan, S., Burgher, B., Buettner, P., Piliouras, P., Otty, Z., Varma, S., & Thaker, D. (2011). Attitudes, knowledge and barriers to participation in cancer clinical trials among rural and remote patients. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, 7, 27-33. doi:10.1111/j.1743-7563.2010.01342.x

- Services Quebec. (2003). Medical travel policy. Retrieved from http://www4.gouv.qc.ca/fr/Portail/citoyens/programme-service/Pages/Info.aspx?sqctype=sujet&sqcid=2420

- Sethna, C., & Doull, M. (2007). Far from home? A pilot study tracking women’s journeys to a Canadian abortion clinic. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology,27(8), 640-647.

- Sethukavalan, P., Cheung, P., Tang, C. I., Quon, H., Morton, G., Nam, R., & Loblaw, A. (2012). Patient costs associated with external beam radiotherapy treatment for localized prostate cancer: The benefits of hypofractionated over conventionally fractionated radiotherapy. Canadian Journal of Urology,19(2), 6165-6169.

- Singh, V. (2002). Rural Income Disparities in Canada: A Comparison Across the Provinces. Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin Canada. 3(7), 1-18. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/21-006-x/21-006-x2001007-eng.pdf

- Smith, S. K., Nicolla, J., & Zafar, S. Y. (2014). Bridging the gap between financial distress and available resources for patients with cancer: A qualitative study. Journal of Oncology Practice, 10(5), e368-e372.

- Thaker, D. A., Monypenny, R., Olver, I., & Sabesan, S. (2013). Cost savings from a telemedicine model of care in Northern Queensland, Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 199, 414-417. doi:10.5694/mja12.11781

- Watanabe, S. M., Fairchild, A., Pituskin, E., Borgersen, P., Hanson J., & Fassbender, K. (2013). Improving access to specialist multidisciplinary palliative care consultation for rural cancer patients by videoconferencing: Report of a pilot project. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 1201-1207. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1649-7

- Wong, S., & Regan, S. (2009). Patient perspectives on primary health care in rural communities: Effect of geography on access, continuity and efficiency. Rural and Remote Health 9(1), 1142. Retrieved from http://www.rrh.org.au/articles/subviewnew.asp?ArticleID=1142

- Yukon Health and Social Services. (2014). Medical travel. Retrieved from http://www.hss.gov.yk.ca/medicaltravel.php

- Zucca A., Boyes, A., Newling, G., Hall, A., & Girgis, A. (2011). Travelling all over the countryside: Travel-related burden and financial difficulties reported by cancer patients in New South Wales and Victoria. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 19, 298-305. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01232.x

List of tables

Table 1

Summary of Availability and Conditions of Medical Travel Programs in Canada

Table 2

Medical Travel Program Type and Service-Related Eligibility Criteria

BC – British Columbia, MB – Manitoba, ON – Ontario, QC – Quebec, NS – Nova Scotia, PEI – Prince Edward Island, NL – Newfoundland and Labrador, YK – Yukon, NWT – Northwest Territories, NU – Nunavut; km – kilometre; NIHB – Non-Insured Health Benefits; “not available” – the program contact did not know, provide and/or verify the requested information.

Table 3

Medical Travel Program Applicant-Related Eligibility Criteria

BC – British Columbia, MB – Manitoba, ON – Ontario, QC – Quebec, NS – Nova Scotia, PEI – Prince Edward Island, NL – Newfoundland and Labrador, YK – Yukon, NWT – Northwest Territories, NU – Nunavut; km – kilometre; NIHB – Non-Insured Health Benefits; “not available” – the program contact did not know, provide and/or verify the requested information.

Table 4

Eligible Expenses and Rates for Reimbursement-Type Medical Travel Programs

BC – British Columbia, MB – Manitoba, ON – Ontario, QC – Quebec, NS – Nova Scotia, PEI – Prince Edward Island, NL – Newfoundland and Labrador, YK – Yukon, NWT – Northwest Territories, NU – Nunavut; km – kilometre; NIHB – Non-Insured Health Benefits; “not available” – the program contact did not know, provide and/or verify the requested information.