Abstracts

Abstract

In 1949, anthropologist Marius Barbeau recruited Margaret Sargent, a young classically trained musician from Ontario to work for him at the National Museum of Canada. As the first ever musicologist to be employed by this institution, Sargent’s first task was to transfer Barbeau’s wax cylinder sound recordings to magnetic tape. While working on Barbeau’s massive collection, Sargent became interested in collecting folksongs and proposed to him the idea of going to Newfoundland to do research. With Barbeau’s support, in 1950 she spent eight weeks in the province, collecting folksongs, fiddle tunes, and other folklore materials mainly in St. John’s and Branch. Despite launching the first Canadian funded research into Newfoundland’s folksong traditions, little is known about Sargent’s activities for the National Museum mainly because she published nothing of her Newfoundland work. Instead, her successor Kenneth Peacock is often viewed as launching this research. Although Peacock later visited the province six times, eventually publishing a three-volume collection Songs of the Newfoundland Outports (1965), it was Sargent who initiated the Museum’s folksong research program in that province. This essay, which is based in part on interviews with Sargent, as well as her field notes and tapes, provides a detailed account of her Newfoundland fieldwork and of the kinds of material she was able to acquire during her one summer of fieldwork. It highlights the fieldwork challenges Sargent faced while in Newfoundland and how her groundbreaking fieldwork paved the way for Peacock’s later research.

Résumé

En 1949, l’anthropologue Marius Barbeau recruta Margaret Sargent, jeune musicienne de formation classique de l’Ontario, pour travailler avec lui au Musée national du Canada. En tant que première musicologue jamais employée par cette institution, la première tâche de Sargent fut de transférer les enregistrements des cylindres phonographiques de cire sur bande magnétique. Tandis qu’elle travaillait à la massive collection de Barbeau, Sargent commença à s’intéresser à la collecte de chansons folkloriques et lui proposa de se rendre à Terre-Neuve pour effectuer des recherches. En 1950, avec l’appui de Barbeau, elle passa huit semaines dans la province, recueillant des chansons, des airs de violon et d’autres matériaux folkloriques, principalement à Saint-John’s et à Branch. Mais, bien qu’elle ait réalisé la première recherche subventionnée dans le domaine des traditions de la chanson folklorique à Terre-Neuve, les activités de Sargent pour le Musée national sont peu connues, car elle n’a rien publié de son travail à Terre-Neuve. Au lieu de cela, son successeur, Kenneth Peacock, est souvent considéré comme étant celui qui a inauguré cette recherche. Bien que par la suite Peacock ait visité six fois la province et qu’il ait fini par publier un recueil en trois volumes des Songs of the Newfoundland Outports (1965), c’est Sargent qui avait lancé le programme de recherche en chansons folkloriques du Musée dans cette province. Cet article, qui se base en partie sur des entrevues avec Sargent autant que sur ses notes de terrain et ses enregistrements, relate en détail son travail de terrain à Terre-Neuve et décrit le type de matériaux qu’elle put recueillir au cours de son été passé sur le terrain. Il souligne les défis auxquels Sargent avait eu à faire face sur le terrain à Terre-Neuve et comment son travail précurseur a facilité plus tard les recherches de Peacock.

Article body

In the 1987 special issue of The Journal of American Folklore titled “Folklore and Feminism,” Barbara Babcock observes that “the history of folklore studies is the history of the male line” and that “women folklorists have been marginalized if not rendered altogether invisible” (Badcock 1987: 395). In terms of Canadian folklore scholarship, Greenhill and Tye similarly argue in Undisciplined Women: Tradition and Culture in Canada that both women’s traditions and women’s contributions to the discipline as collectors often have been passed over or underestimated (Greenhill and Tye 1997: 7). According to Greenhill and Tye, although women have frequently forged new territory, their work has been largely excluded from “the paradigm of conventional academic folklore” due to a lack of formal folkloristic training (Greenhill and Tye 1997: xii). The article that follows explores the contributions to Canadian folklore of one woman who I argue falls into this category of the overlooked and underappreciated: Margaret Sargent.

A native of Thunder Bay, Ontario, Margaret Sargent (McTaggart) (1921- ), graduated from the University of Toronto’s School of Music in 1943. In 1949 she was recruited by well-known anthropologist Marius Barbeau (1883-1969) of the National Museum of Canada. Sargent worked with the Museum for just under two years, resigning in the fall of 1950 to get married. As the first ever musicologist to be employed by this institution, Sargent’s primary task was to transcribe the aboriginal music Barbeau had collected from wax cylinder recordings that were rapidly deteriorating (Sargent 1951: 78). While at the Museum, Sargent also provided assistance to Helen Creighton (1899-1989) by transcribing songs for her publication Traditional Songs from Nova Scotia (Creighton and Senior 1950: 1, 17, 41, 64 and 106). As well, she launched the first Canadian funded research into Newfoundland’s folksong traditions. Sargent spent eight weeks in the province collecting both in St. John’s and the community of Branch on the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula.[2] Before leaving the National Museum of Canada, she recommended former School of Music classmate, Kenneth Peacock (1922-2000) as her replacement (Guigné 2004).

This article focuses attention on Margaret Sargent’s contributions to Canadian folklore that have been overlooked. Her short employment with the Museum attracted little attention and she published so few works (and nothing related to her Newfoundland research) that her impact on the disciplines of folklore and ethnomusicology is generally viewed as insignificant. For example, the few assessments of Sargent’s position within both folklore and music scholarship are largely dismissive. A biographical sketch appeared in the 1981 Encyclopedia of Music in Canada but was dropped from the revised 1992 edition (Duke 1981: 843). In her study of folklore scholarship in Canada, Carole Carpenter comments that, while in Newfoundland, Sargent “misunderstood the customs associated with singing” and “consequently failed to obtain much material during her brief collecting trip in the early 1950s” (Carpenter 1979: 37). Notwithstanding these appraisals, I argue here that Margaret Sargent did make important contributions to Canadian Folklore Studies. Furthermore, Sargent’s experiences at the National Museum reveal much about the fragmented state of folklore research at this institution during the mid-twentieth century. In 1997, when I contacted Sargent, still living in Vancouver, British Columbia, to learn more about her work for the National Museum and her motivations for going to Newfoundland, she kindly provided me with a detailed chronology of her activities on behalf of the National Museum and, in particular, her initial efforts to collect songs in Newfoundland in 1950. She also allowed me access to two photograph albums and six notebooks kept during her Newfoundland field research[3]. In light of this new material, in addition to her field tapes deposited at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, her activities during this time period for the Museum must be reevaluated[4].

Figure 1

Margaret Sargent at the National Museum, 1950.

At the age of twenty, Sargent was working on her Bachelor of Music degree when she first developed an interest in researching aboriginal music in 1941. Looking around for a thesis topic, and anxious to break away from the more conservative studies of European composers and European-based music which typified the Music School’s approach in the 1940s, she proposed to her supervisor, Leo Smith, the idea of doing something on the native and primitive music of Canada. He advised her to see Marius Barbeau of the National Museum of Canada. Sargent subsequently sent Barbeau a letter outlining her interest[5].

Since 1911 Barbeau had been actively engaged in the collection and documentation of folklore materials, concentrating mainly on aboriginal and French Canadian cultures (Nowry 1995). He was well known to instructors at Toronto’s School of Music both for his research and for his extensive popularizing of his collected materials for such events as the Canadian Pacific Railway sponsored folk festivals (McNaughton 1981: 67-73). Barbeau gladly agreed to serve as consultant to Sargent, offering her access to his field materials. Shortly after this, Sargent visited Barbeau in Ottawa to view his collection and to listen to some of his recordings. In 1998 Sargent speculated that her visit to the Museum during the war period served as a mental boost for Barbeau: “It looked like his stuff would never see the light of day. It was getting mildewed. It was on those soft wax cylinders. That a university student would come up and look at it and work on it, you know, gave him some hope[6].” Barbeau had reason to be concerned about the state of his enormous song collection which, by the late 1940s, included over 3000 aboriginal, 7000 French-Canadian and 1500 English items, all of which were made using an Edison phonograph machine and soft-wax cylinders (Fowke 1988: 15). At fifty-eight, he was getting close to retirement and a large part of his life’s work was lying in the corridors of the Victoria Museum in a fragile state.

Barbeau eagerly placed his field collection, along with published and unpublished papers, at Sargent’s disposal and it was this material which later formed the basis of her thesis “The Native and Primitive Music of Canada” (1942). After graduating, Sargent sent Barbeau a copy of her dissertation[7]. Although she wished to further her studies in this area, and perhaps pursue a career at the Museum working on aboriginal music, the Second World War had placed a strain on many government institutions. As she recalled,

I would have loved to have got a job working in the Museum on Dr. Barbeau’s Indian recordings, but there wasn’t a hope in hell of doing so in a half-shut institution, in a Canada which had just emerged from a ten-year depression and was in the midst of a costly war. Investigations showed no chance for graduate study on Indian music, which didn’t exist in Canada nor in American universities written to. Anyway [there was] difficulty studying in the U.S. because of wartime currency[8].

Despite the lack of employment opportunities, Barbeau and Sargent continued to stay in touch, exchanging letters from time to time.

Barbeau officially retired from the Museum in 1948, but because of his lifelong contribution, he was permitted to retain an office there and to use its facilities for several years. Realizing that much of his collection still remained unprocessed and on wax cylinders, in the improved fiscal climate following World War Two, Barbeau negotiated with the Museum to fund a position to allow him to attend to his Indian song recordings. A few months later he offered Margaret Sargent the job.

Despite Barbeau’s lifelong commitment, when Sargent arrived at the National Museum in March of 1949, folklore research at the institution was still in an embryonic stage. The staff consisted of a small band of workers: Helen Creighton, Carmen Roy (1919- ), and Barbeau’s son-in-law, Marcel Rioux (1911-1992), the Chief of Ethnology and Folklore (Croft 1999: 102; Nowry 1995: 349; Ouimet 1985: 42-57). All of these individuals had been recruited by Barbeau, and, other than Helen Creighton who concentrated mainly on Anglophone traditions, much of their research concentrated on either aboriginal or French-Canadian traditions.

It was in this environment that Sargent started her initial employment with Barbeau. Using a newly invented Sound Mirror recording machine, her first task was to transfer material from wax cylinders to magnetic tape (Sargent 1951: 75). Sargent worked initially with the Huron songs from Lorette, Québec, that Barbeau had collected in 1911 and which had been virtually untouched (Sargent 1950: 175-180). The tasks Sargent carried out then would comfortably fall within the realm of what later would be called ethnomusicology, or “the study of music in culture” (Merriam 1963: 206-13). In the late 1940s, though, she was operating in uncharted waters.

There was no name for what I was doing and they finally called me a technical officer.… When he hired me he said, “There’s a new type of machine called a tape recorder” and with that he foresaw that we could use it for transcribing songs because soft wax, you can only play it once or twice before you destroy it[9].

Barbeau realized that Sargent’s musical training could be of considerable use to him and, because of her thesis research, she was at least casually familiar with the aboriginal materials.

By 1949 the Museum had seen a dramatic increase in enquiries from individuals looking for examples of aboriginal and folk music (Guigne 2004: 174). Sargent, who was assigned to handle the enquiries, described her activities in her “Folk and Primitive Music” report.

During the past year, outside contacts have been numerous. Iroquois music was recorded on magnetic tape to assist in the preparation of a film on the False-Face and Rain Dances of the Iroquois, by the National Film Board. A Museum lecture was given to the children of Ottawa, showing the collecting of folksongs, their use by the children themselves, and films incorporating them. Both Alan Mills and Edith Fowke of the CBC have visited the Museum to examine the collections and to discuss the possibility of broadcasting the best samples over the radio, Mr. Mills as a singer of folksongs and Mrs. Fowke as a program director.

Sargent 1951: 78

She also recognized the Museum’s limitations in handling such requests. In addition to transferring material from wax cylinders to magnetic recordings, the Museum was attempting to transcribe songs and to add to its collections. Much of the material had yet to be processed or converted into any publishable format.

Perhaps because she recognized the overabundance of aboriginal and French collections, Sargent was also keenly aware of the lack of English Canadian materials. One day, at the Museum’s library, she encountered Elisabeth Greenleaf and Grace Mansfield’s Ballads and Sea Songs of Newfoundland (1933) and Maud Karpeles’ Folksongs from Newfoundland (1934) (Gregory 2000: 151-165; Rosenberg and Guigné 2004: ix-xxv). Intrigued by the rich variety of material these women had separately acquired on their travels several years earlier, and enchanted by Barbeau’s pursuits as a researcher, Sargent proposed to him the idea of going to Newfoundland.

Barbeau was certainly aware of the research potential in this region. He was familiar with W. Roy MacKenzie’s works The Quest of the Ballad (1919) and Ballads and Sea Songs from Nova Scotia (1928), and early on he identified the prospects for collecting “sailors’ chanties and other songs” in “Newfoundland, Cape Breton and Nova Scotia” (1919: 189). Up until the late 1940s, with the exception of Helen Creighton’s work in Nova Scotia, the Museum had paid little attention to the folk music traditions of Eastern Canada. And, as Sargent discovered, the Museum had no material of any kind from Newfoundland: “I also added that since Newfoundland was our newest province and the federal government was anxious to do things for them they might look favorably on the idea[10].”

Sargent’s interest was timely; the American folklorist, MacEdward Leach (1892-1967), was already preparing to come to Newfoundland that same summer to begin the first of two seasons of fieldwork (Guigné 2004: 121-124)[11]. Barbeau responded enthusiastically to her suggestion, guiding her through the process of presenting a proposal to Dr. Alcock, Curator of the Museum.

[Barbeau] was a wonderful boss. Every bright idea I got he encouraged. Even though some of them were probably not that great. He was really very nice to work for. And so he said, “Well you find out about it and then if it’s feasible.…” He said, “We’ll go and see Dr. Alcock. Work out a presentation and we’ll talk to Dr. Alcock.” He was a geologist who was the head of the National Museum, of our part of the National Museum, although he knew very little about folksongs. He came from the Maritimes, so he was enthusiastic about Maritime and Newfoundland stuff. He usually deferred to Dr. Barbeau on anything that had to do with folklore, folk music, you know, that type of thing and so he agreed[12].

Having received Alcock’s approval, at Barbeau’s suggestion, Sargent also wrote Premier Joseph Smallwood noting “With the entry of Newfoundland into the Dominion of Canada we in the Anthropological Division of the National Museum are desirous of possessing a collection of Newfoundland folk-songs to be preserved and studied with those of other parts of Canada…[13]” Smallwood promptly replied advising her that he thought the idea a good one. He then asked his close friend, Leo Moakler, advertising manager for F. M. O’Leary which published the monthly newspaper The Newfoundlander, to correspond with her[14]. Moakler had earlier helped Smallwood with the publication of the two volumes of the Book of Newfoundland (1937) sponsored by F. M. O’Leary Limited (Will 1991: 592).

Shortly thereafter, in a letter to Sargent, Moakler explained that this monthly publication carried a folksong section for over ten years with the words supplied by the readership: “They are not all exclusively Newfoundland, but all are authentic folksongs handed down from generation to generation[15].” He advised her of the existence of various lesser known sources which consisted of “paper-covered booklets containing from 12 to 20 songs.” These publications which included, among others, James Murphy’s Songs Their Fathers Sung, For Fishermen, Old Time Ditties (1923) and John Burke’s Burke’s Popular Songs (1928) had been created at the beginning of the twentieth century and reflected the high value Newfoundlanders historically placed on their own folklore (Mercer 1979).

Moakler also sent Sargent the names of several key individuals already well known for their interest in Newfoundland folksongs. They included two prominent St. John’s figures: businessman Gerald S. Doyle (1892-1956) and lawyer Frederick Rennie Emerson (1894-1972). She was also encouraged to contact Maud Karpeles (1886-1976), the British folksong collector who had visited Newfoundland several years earlier (Doyle 1989: 32; Frecker 1972: 2; Bronson 1977: 455-64). Finally, Moakler also suggested that she contact the Canadian musician Howard Cable (1920- ), who had visited the province in 1947 with music educator Leslie Bell to collect folksongs (“Cable.” 1992: 182-83; Rosenberg 1994: 55-73).

Of this group, Emerson and Doyle were well-known locally for their separate efforts to make Newfoundlanders culturally aware of their distinct musical heritage (Woodford 1988: 174; Rosenberg 1991: 45-57). Both men were respected for their knowledge of Newfoundland folksongs and had done much to promote the collection and dissemination of folk music in Newfoundland. A St. John’s native, Emerson spent his school years in Suffolk, England obtaining a British education. He learned to play the piano at an early age and had a natural love of music. Although Emerson wanted to be a musician, his father instead encouraged him to first study law. He apprenticed to a St. John’s law firm, and at age twenty-three was a practicing lawyer.

A self-taught polyglot, Emerson spoke eight languages and could read twelve more. Music, however, was his first love. An amateur musician and composer, Emerson was frequently involved in local stage productions of one kind or the other (Woodford 1988: 174). From the 1920s, Emerson played both an influential and supportive role to those interested in the documenting Newfoundland folksongs. In 1928, during a family trip to London, he met Maud Karpeles, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Clive Kerry and other prominent figures involved with the English Folk Dance and Song Society, shortly thereafter becoming a member himself. When Karpeles visited Newfoundland to collect folksongs in 1929 and 1930, Emerson befriended her, facilitating her activities and offering accommodations. As Emerson’s daughter recalls,

He was always interested in music, always interested in folksongs, and then Maud came out; she came to visit us. I don’t remember, the first one was about ’29 and again in ’31-’32 [1930] those sorts of things. Actually I remember she used to dance with bells around her knees and Skipper (Father) would play for her. She was always a family friend[16].

An intellectual at heart, Fred Emerson wrote one of the earliest essays on Newfoundland folk music and its collectors (Emerson 1937: 234-38). During the 1940s, Emerson regularly gave music appreciation lectures to various groups in St. John’s, including students of Memorial University College. In many sessions he highlighted the importance of Newfoundland folksongs. As he once noted, these songs were worthy of study “because they are the very heart of our real Newfoundland culture[17].” Emerson regularly performed examples of older English folksongs which Karpeles had collected in Newfoundland and which her friend and colleague, the British collector Cecil Sharpe, had also documented during his trips to the Appalachians (Karpeles,1932; 1934). Although Emerson appreciated the older material, he also recognized that his friend Karpeles was sometimes too exclusionary in her collecting tastes — rejecting “Come All Ye’s” and locally composed material. As he reminded his students “Newfoundland has still much to offer to the folk-song collector[18].”

Like Emerson, Gerald S. Doyle also had a passion for Newfoundland music. Originally from King’s Cove, Bonavista Bay, Doyle moved to St. John’s at age five. In his early teens he worked at Wadden’s Drug Store, but by 1919 established himself as the exclusive Newfoundland agent for the Dr. A.W. Chase Medicine Company. Doyle eventually became a highly successful businessman (Doyle 1989: 32). As a Newfoundland patriot, Doyle promoted “home-grown” locally composed music through the free distribution of songsters which were paid for by the advertising of various products associated with his business. By 1950, Doyle had already published two editions of Old-Time Songs and Poetry of Newfoundland (1927, 1940) which Neil Rosenberg describes as “‘key texts,’ in creating a popular canon for Newfoundland” (Rosenberg 1991: 46).

During the 1940s, Canadian servicemen stationed in Newfoundland gained exposure to Doyle’s more popularized brand of Newfoundland music, both through his songsters which they later exported back to Canada, and through the performances of musician Robert (Bob) Macleod (1908-1982) who assisted Doyle in preparing the 1940 edition of Old-Time Songs and Poetry of Newfoundland (Krachun 1991: 418-19). In 1948 and 1949, Canadians also became familiar with songs taken from the Doyle publications through the arrangements of musicians Howard Cable and Leslie Bell on CBC radio. During their travels to the island in 1947 to collect folksongs, these musicians were introduced to Bob Macleod who played a number of Newfoundland songs for them from Doyle’s 1940 publication (Rosenberg 1994: 58 ). Soon after, Cable and Bell created contemporary arrangements of this material, later having them performed on air by such groups as The Leslie Bell Singers (Cowle 1992: 744).

Sargent contacted several of the individuals Moakler recommended, seeking their advice on travel to Newfoundland[19]. Several weeks later she received a letter from Maud Karpeles advising that, thanks to her friend Fred Emerson, there was “a possibility that the authorities in St. John’s, Newfoundland may invite me to do more collecting[20].” Karpeles proposed that she and Sargent could possibly join forces. Although Dr. Alcock, the Chief Curator, approved of the collaboration, Karpeles’s plans to link up with Sargent later fell through because of lecturing commitments and financial difficulties. Sargent decided to go to Newfoundland on her own.

Before Sargent’s departure, Dr. Alcock arranged for her to meet Claude Howse, an associate government geologist in the provincial Department of Natural Resources located in St. John’s (Cuff 1984: 1097). Barbeau coached Sargent on the kinds of equipment she would need, including a camera which she had never used before. He encouraged her to look for a variety of folklore genres such as beliefs and practices, customs related to social and political institutions, rites of individual life, games, sports and pastimes, stories, songs and sayings. Sargent noted these suggestions down in her field book shortly before her departure[21].

On 4 July 1950, Sargent boarded the train in Ottawa eastbound for the Maritimes. Commenting later to Barbeau, Sargent observed, “Virtually everyone on the train from Ottawa to North Sydney was bound for Newfoundland[22].” From North Sydney she then took the ferry making the one hundred and forty-five kilometer trip across the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Port Aux Basques, Newfoundland. She boarded another train crossing the province, arriving in St. John’s four days later. From the moment Sargent embarked on her lengthy journey, she showed a keen interest in the people around her. She recorded the names of individuals she met and any information they conveyed to her about Newfoundland culture and folklore.

Once in St. John’s, local contacts she had made on her journey helped Sargent to get her bearings. Anna Templeton, whom she had met on the train coming down, and a key field worker for the Jubilee Guilds (later renamed the Newfoundland and Labrador Women’s Institutes), arranged for her to stay at the Hendersons’ Boarding Home on Waterford Bridge Road in the west end of the city (Graham 1994: 606-607)[23]. Bringing her to places of local interest and providing her with interpretations of Newfoundland expressions and customary traditions, the Hendersons in turn extended their hospitality showing her the sights of the city. With this family Sargent had her first sampling of Newfoundland cuisine including such dishes as liver cakes, potato cakes and brewis[24]. After obtaining copies of some of the recipes from her hosts, Sargent made note of the experience in her fieldbook.

Sunday morning I had “brewis” and bacon which Mr. Henderson had prepared. It consists of Nfld. hard tack soaked overnight. Then it is heated while damp. Then bacon is cut up and mixed with it, melted butter and bacon fat are poured over it and salt and pepper to taste are added. The result is very tasty. This was often used by the fishermen out on the banks who added fish instead of bacon[25].

Over the course of her visit Sargent would record similar everyday events in her notebooks.

Sargent spent her first week in Newfoundland sorting out equipment and following up potential leads. After an initial visit with Claude Howse, she commented in a letter to Barbeau, “All at once everything is happening and I am making contacts[26].” Sargent’s notes reveal that many of the people she first encountered on her arrival were well positioned to help her with fieldwork. They included government officials, the clergy, various lawyers, some radio personnel, and the head librarian at Gosling Memorial Library. Aware that she was looking for folklore, they responded with ease, giving her bits of their own folk knowledge on many subjects, including medicinal cures, words, phrases and expressions found in the local dialect, the occasional fairy legend and anecdotes about local characters. Sargent duly jotted these materials down. After meeting Claude Howse she observed,

[w]e talked about everything under the sun. He has had warts cured by a curse. His secretary Miss K. Hawco, had a toothache cured by a seventh son of a seventh son. Would like to get it recorded — also Mr. Howse’s imitation of typical dialect[27].”

Howse eventually guided Sargent to Gerald S. Doyle’s friend, Bob Macleod. He in turn took her to the Colonial Broadcasting Corporation, introduced her around and played Newfoundland songs for her. Sargent was thrilled with this experience.

I can’t get over the leisurely way business men act here. We talked for about an hour and a half. Then over to the Colonial Broadcasting Corporation where I met Mr. [Mengie] Schulman and Mr. [George] Murdock. They’re going to let me have some copies of Biddy O’Toole on tape. What a slap-happy gang! For an hour or so Bob Macleod played the organ, I played the piano and everybody sang[28].

Later Claude Howse brought Sargent to meet Fred Emerson at his law office. In a letter to Barbeau she remarked, “He took me to see Emerson who knows Maud Karpeles and Vaughan Williams very well[29].” Like Macleod, Emerson sang her a selection of Newfoundland songs in his office. He also extended his friendship, bringing her to his home where “we discussed music all night — folk music, classical music, everything[30].”

Initially Sargent was unaware that some of the material being presented to her reflected a St. John’s interpretation of rural Newfoundland culture. People from St. John’s frequently drew upon local dialect and song to make fun of their outport counterparts whom they considered to be less educated, unrefined and therefore the subject of much humor (Hiscock 2005: 205-242). For example, this attitude was evident in her meeting with Macleod whom she describes to Barbeau as “an almost unbelievable figure”.

He has gone to all the outports collecting the old songs for Gerald S. Doyle, he can do all the accents.… He learned a great many of these songs right from P.K. Devine an old Irish Newfoundlander. Despite the fact that he is an accomplished musician he sings them like a person from the outports[31].”

At the time Sargent was so impressed by Macleod’s knowledge that she recorded him singing several songs from the 1940 Doyle publication which he frequently performed. These included “The Badger Drive,” “Concerning One day in Bonay I Spent,” “Jack Was Every Inch a Sailor,” “Kelligrews Soiree,” “Lukey’s Boat,” “The Ryans and the Pittmans,” “Tickle Cove Pond” and “Six Horse Power Coaker” composed by Art Scammell (Doyle 1940: 29, 33, 13, 16, 71, 53, 18, 74; Blouin 1982). Sargent also recorded him performing “Feller from Fortune” and “H’emmer Jane” which Macleod sang using an exaggerated Newfoundland dialect. Although these songs had not been published previously by Doyle, they were part of Maclod’s performance repertoire[32]. Reflecting back on this experience Sargent noted, “He wasn’t what I called a folk singer; they called him ‘professor’ as a nickname[33].”

By her second week, Sargent was anxious to try her hand at fieldwork in the outports. On Monday, 17 July she finally headed off for Branch, a small coastal fishing village 130 miles from St. John’s in St. Mary’s Bay on the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula (Horan 1981: 240-41). This mainly Roman Catholic community with strong Irish roots is one of several settlements located on the Cape Shore leading toward the town of Placentia. Oral history has it that Branch was originally settled in the late 1700s by Thomas Nash from Callan of County Kilkenny (Power, Careen and Nash 1989: 6). Many families along this area of the Avalon Peninsula trace their roots back to Ireland[34]. In the 1850s it was one of two communities along this part of the shore to have a Roman Catholic church. By 1900, with a school, a small number of businesses and the church, Branch was an important centre along the coast.

When Sargent arrived in Branch in 1950, the church still dominated much of life there. Typical of many rural Newfoundland communities, Branch had no running water or electricity. The resident population of approximately 400 survived mainly on subsistence farming and fishing. As elsewhere on the Cape Shore, the fisherman of Branch still sold their catch to the mercantile firm of Sweetmans in Placentia under the “truck” system of credit by which a merchant advanced supplies and fishing gear to fishermen against a season’s catch; “squaring up” was generally done in the fall of the year (Power, Careen and Nash 1989: 9; Story, Kirwin and Widdowson 1982: 585). Starting in 1940, with the commencement of the United States Naval Base in Argentia, some residents found additional employment outside the community. It was also common for young women to move to St. John’s where they worked in domestic service with various families. Sargent chose Branch primarily because Claude Howse had suggested it and was able to arrange for ground transportation. At the time many communities were inaccessible by road and travel to the outports required some preparation. As Sargent notes, “To get to an outport there were no bus routes and to get to an outport you had to sort of know somebody who was going out[35].”

Rural Newfoundland provided quite a contrast to what Sargent found in St. John’s. As was customary, she boarded in homes in the community, thereby experiencing first-hand the rural way of life. In a letter to Barbeau, she described her initial impressions, her difficulties in finding accommodation and her first attempts to collect.

Arriving at length in Branch one of the most beautiful villages I have ever seen. (Houses scattered on a hill, immaculately painted, each with a white fence, the village enclosed on one side by fawning cliffs on the other by rolling hills while it looks on the sea.) I tried in vain to get a place to stay. It was no good, I couldn’t get one, so back we went to St. Bride’s. There I succeeded in getting a lovely place where I stayed 3 days. There I got much folklore but no songs[36].

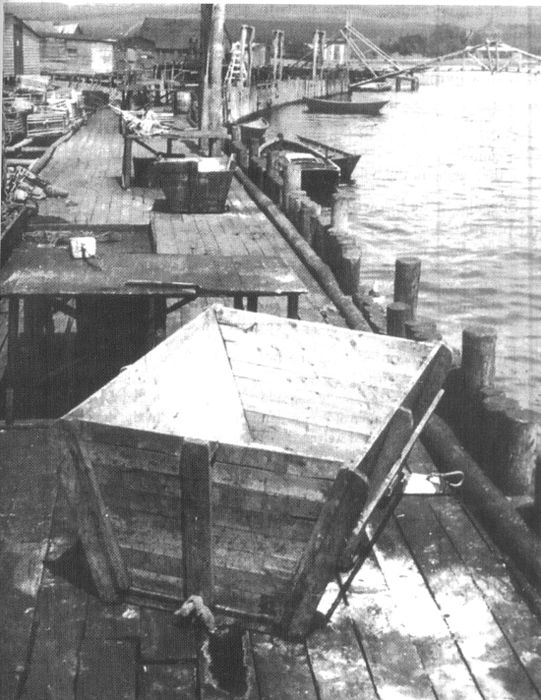

Figure 2

Fish flakes with bows, Branch in the background.

As Sargent’s comments to Barbeau reveal, she reached an early point of exasperation in her attempts to locate folksongs and folksingers. She recounted how, in commuting back and forth to Branch, she had visited an elderly gentleman, Andrew Joseph Nash, “who gave me loads of stories and verses — but still no folk music.” She had also called on the priest looking for folksong sources only to be told “there wasn’t any.” Nevertheless, she informed Barbeau, “I couldn’t help feeling there should be[37].” While in St. Bride’s, however, she took down various anecdotes and stories as had been conveyed to her by the people she visited. During her stay with the Conway family in St. Brides she noted “The next morning during breakfast I heard why the flounder’s eyes looked as they did — also other tales[38].” A few pages later she noted this tale down as follows.

Once upon a time the fish decided to choose a king. They were all there but the flatfish. The herring wanted to be king but the others said “No. The whale was the largest. He should be king.” When they agreed to this along came the flatfish. When he heard about this he looked scornful his mouth puckered and his eyes popped. He said “How silly; I should be king,” and it was because of his indignation at not being chosen king that he looks the way he does today[39].

On July 20, Sargent finally found accommodations with a young couple in Branch. She continued to look for folksongs, but once within the community, turned her attention to documenting her surroundings. Using her camera as a means of being both visible and purposeful in her activities, she recorded the scenery as well as activities around the community, at the fish flakes and on the wharf. She was eclectic; for example on one instance she documented decorative entrances to several of the homes.

This morning, Saturday I made a very bad start. Not getting up until ten. I went out taking pictures and managed to get a full role [sic] solidly of doorways. As far as aesthetic value goes, some of them are not very good, I’m afraid, but they are all done here, and as an example of artistic endeavor, they’re very interesting[40].

The children of Branch assisted Sargent in her picture taking.

Friday was a day of picture-taking. I must have taken 70 shots of the village and the sea. My helpers were very useful. They told me of places to go, and carried the camera etc[41].

Figure 3

Fishing Stage at Branch.

In addition to acting as gatekeepers of community information for Sargent, the children undoubtedly informed Branch residents of the reasons for her presence — a lone female stranger — in the community.

Her written records were as varied as her photographs. For example, through casual conversations with local inhabitants Sargent gathered details pertaining to community history and the fisheries. She discovered that local fishermen working under the “truck” system found it difficult to make a living because they were constantly in debt.

Down I went into one of the houses and talked to two of the men about the amount of fish they caught. The price they get ($10 a quintal this year — $15 last year) the cost of salt, the likelihood of their going in the hole. They can hardly seem to win[42].

She also jotted down various residents’ comments on local beliefs and practices.

It is against custom to speak when hauling in nets. Also one doesn’t go fishing on Sundays or holy days — only allowed 2 Sundays and the fish taken on those days has to be given to the church. Women belong to a Holy Name Society and each partakes in scrubbing the church[43].

Finally, she recorded what to her seemed like interesting everyday practices.

Point Lance is about 7 or 12 miles from St. Brides. In the days before roads when a man died he was done up in a canvass. Then the others cut large poles called “burying poles.” They slung the canvas from it and carried him that way, all the way to St. Brides to be buried. One thing I forgot to note…. where I am staying they lock the door when they go out and hang the key on a nail beside it[44].

Sargent’s notes reveal that aspects of life in Branch both perplexed and disturbed her. It was so different from anything she had ever experienced. On the young couple with whom she was staying, she remarked in her field book:

It puzzles me how [she] who worked in town for 6 years, and [he] who was a gunner in the R.A.F. who talks of dancing the tango in a Covent Garden Dance Hall and Blackpool who has been in N.Y. and Boston, in all the British Isles can live here in Branch under the most primitive conditions possible, and act quite contentedly about them[45].

Sargent was often pulled between the business of folklore collecting and her social conscience, for while prosperity was certainly present in St. John’s, living conditions were much lower in many of Newfoundland’s rural communities in the early 1950s. Although captivated by the beauty of the area around Branch and by the people, she found the low standard of living distressing. Clean water was an issue and, as she communicated to Barbeau, several people had become ill with “summer complaint,” a local term for diarrhoea (Crellin 1994: 131).

One child died last week. I think it might be due to infection whether from water or the swarms of flies which infest the place. Both the man and little girl in the place where I stayed are ill. I rather think that must have been the reason for my illness of several weeks. It doesn’t seem logical that it would have been rheumatic fever since I was in excellent health when I arrived[46].

In another entry she writes:

The teeth of Newfoundlanders are very poor. This is due not only to faulty food, but also due to utter absence of care. Most of them never have their teeth filled but when they decay have them pulled out. One may see a child of ten or eleven with either no front teeth, or little slivers left. Very few people past their early twenties have their own teeth. A lot of the children have red inflamed eyes. The doctor said this was largely due to the lack of fresh vegetables, I guess it’s a kind of scurvy. I haven’t had fresh vegetables once. Imagine living like that all the time[47].

Finally, Sargent was also concerned about the tuberculosis epidemic in Newfoundland during this period. Having recently recuperated from a severe bout of rheumatic fever she was acutely aware of the fragility of her own health.

Heavens I’m coughing. Being surrounded by tuberculid people has made my mind more conscious of tuberculosis than I usually am… Everyone here has a cold. No wonder it turns to T.B. when they don’t stay in bed until it’s better[48].”

Sargent was particularly surprised by the heavy demands placed on women.

Even the women here go out at night in their aprons. How hard they work. They make meals, bake bread on a hot cookstove during the hot summer, as well as winter. They wash, iron, look after children. Truly their work is never done[49].

Sargent’s observations support Hilda Chaulk Murray’s findings in her study More Than 50%: Woman’s Life in a Newfoundland Outport, 1900-1950. Murray describes women’s work as crossing over from the kitchen to the garden and the fisheries; she points out that these female responsibilities started at a very early age. In light of the social problems she encountered, Sargent puzzled over the apparent lack of leadership in the community and, in particular, the role of the priest and the Roman Catholic church.

Also with so many children obviously suffering from malnutrition I can’t figure why [he] can’t organize them into a brigade to grow a garden to supply everyone with enough fresh vegetables. At the same time though the women have to be taught how to cook. Here goes the social reformer again[50].

Notwithstanding her own personal adjustments to rural Newfoundland, Sargent did manage to collect some song material. Although she was unable to use her tape recorder because of the lack of electricity, her field books and notes at the back of her photograph albums reveal that during the week that she spent in the Branch area, Sargent took down several song texts[51]. From Andrew Nash, age 70, she collected “The Maid of Newfoundland,” and a local composition “The Drowning of Carter and Aspel.” From Patrick Mooney and Thomas Joseph Nash respectively, she collected the texts and melodies for “Reilly,” a version of the British broadside ballad “William Riley’s Courtship” (Laws 10) and the North American ballad “Young Charlotte” (Laws G-17). Although the performers are not noted, Sargent also copied the text for “Ye Roving Boys of Newfoundland” (also known as “The Shea Gang”) and the texts for three local compositions “The Loss of the John Harvey,” “The Loss of the Tolseby “ and “Merchant Who Lost His Wife Asked for a Girl in a Showroom [Outharbour Merchant Writes for a Wife][52].”

Having had enough of life in Branch, Sargent eventually decided to return to St. John’s. Ironically, on the eve of her departure she finally had a breakthrough in folksong collecting. A short time later she described the encounter to Barbeau.

I was writing some poems and folklore. When I mentioned songs one of them asked if I’d like a song called the “Summer Seasons.” One of the others said “Oh no she only wants Newfoundland songs, not the old ones.” I said I was interested in everything and when I heard it I almost gasped… They all know these songs — one man 140 of them — so I think I’ve struck a gold mine[53].

In her letter to Barbeau she included a hand transcription of the music and she also noted the text in one of her fieldbooks. Although she did not disclose which singer knew 140 songs, the performer of this song turned out to be a man who regularly visited the family she was staying with in Branch[54].

On 24 July, Sargent left Branch for St. John’s. Planning to return again, she left her field equipment behind. During her first week in St. John’s she spent time visiting Marjorie Mews, the librarian at Gosling Memorial Library, recording from her enthusiastic performances of “A Great Big Sea Hove in Long Beach” and a variant of “I’s the B’y[55].” Sargent paid another visit to Bob Macleod recording additional songs from him. She visited the Emersons and attended a coffee party hosted by Anna Templeton[56].

Three weeks later, Sargent returned to Branch to collect her clockwork Edison phonograph recorder, staying in the community just overnight. She had hoped to contact a man named John Joe English (1886-1991), known to be a great “entertainer” along the Cape Shore often performing at community concerts (Power, Careen and Nash 1989: 101; “John Joe English” 1991: 4)[57]. As luck would have it, English was also heading into St. John’s by way of the same community taxi she was taking. As she later informed Barbeau,

[h]e returned to town last night so I did too and tomorrow night he’s coming over here to sing and I can use the tape machine! He knows all sorts of old ballads he learned from his parents. He says he hasn’t sung them for years because he gets laughed at[58].

Over the course of an evening at Hendersens in St. John’s, English performed eight songs for Sargent: “The Foggy Dew,” “Riley and I Were Chums,” “Mary and Willie Down By the Seaside,” “Banks of the Nile,” “Edwin the Gallant Hussar,” “Mary the Pride of the Shamrock Shore,” and the sacred round “Dona Nobis Pacem” which English may have learned via the Roman Catholic church in the community (Blouin 1982)[59]. English also gave her three recitations: “Man With a Hundred Wives,” “The Brave Engineer” and “Coon, Coon, Coon” a Negro dialect song[60].

With the exception of her brief return trip to Branch, Sargent chose to stay in St. John’s for the remainder of the field season. Reluctant to move too far because of poor health, she drew on contacts she had made on the trip to Newfoundland to locate informants and then conducted her interviews in and around the city. During the second week in August, a friend, “Nealie,” whom she had met on the train, took Sargent to see an uncle, Mr. W. J. Bursey (1892-1980) who “sang for me in his office at the back of his store, the Fort Amherst Fish Company[61].” Originally from Old Perlican, Trinity Bay, Bursey had been involved in the fishing business since the early 1920s. He had operated Fort Amherst Sea Foods out of Quidi Vidi since 1945 (Stockwood 1981: 300). Sargent recorded nine songs from Bursey including “A Woman’s Tongue Can Never Take a Rest,” a version of “Lukey’s Boat,” the occupational song “Haul on the Bo’line,” and a humourous formula tale “’Twas on the Labrador Me B’ys” sung as a round[62]. Bursey performed the round as a kind of story as follows.

Some years ago, in the most northern parts of Newfoundland, there was a concert started. Some one suggested that Uncle John should tell a story. And Uncle John went on about various things. “But” he said, “boys listen,” he said, “the only story I can tell, I’ll sings ye’s a song. And I want ye to help me out with the various parts.” [Bursey then starts to sing].

“Oh, ’twas on the Labrador me b’ys,

’twas on the Labrador,

’twas on the Labrador me b’ys

’twas on the Labrador.”

[He then laughingly commented “Now boys, the second verse”]

“Oh, ’twas on the Labrador me b’ys,

’twas on the Labrador,

’twas on the Labrador me b’ys

’twas on the Labrador.”

[Bursey enthusiastically shouted “ Now boys, join in the chorus”

and started the round again.]

“Oh, ’twas on the Labrador me b’ys,

’twas on the Labrador,

’twas on the Labrador me b’ys

’twas on the Labrador[63].”

Sargent was greatly amused.

Later that afternoon, Bursey took Nealie and Sargent to Portugal Cove where they talked to fishermen and watched them mend nets. A short time later she returned to the community with the Hendersons so she could photograph some nineteenth century gravestones[64]. Around 18 August she also met with educator and historian, Leo English (1887-1971), observing “he has been an inspector of schools for many years and has picked up things in many outports” (Janes 1981: 780)[65]. At the time English was Curator of the Newfoundland Museum and a recognized authority on many Newfoundland subjects. Sargent persuaded English to let her tape-record him reading entries from various chapters of his unpublished manuscript “Legends and Folklore of Newfoundland[66].” Over the course of two days she recorded from him stories, words, customs, superstitions, legends, information on folksongs and other folk materials which he had collected for his publication. English infilled the conversation with anecdotes about the material. As well, Sargent stopped by the Jubilee Guild’s office to see her friend Anna Templeton and photographed some of the crafts on display[67].

On 23 August, the Hendersons took her to nearby Torbay to visit a fiddler, Tom Jennings. In her notebook Sargent took an account of the fourteen melodies she recorded including “Wind That Shakes the Barley,” “Irish Washerwoman,” “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” “Soldier’s Joy Reel,” and “Haste to the Wedding.[68]” Jennings also performed the song “The Jolly Tar.” Before leaving Sargent took photographs of Jennings and the Hendersens.[69]

She recorded more songs from Bursey on 24 August and, that evening, the Hendersons took her to supper at Murray’s Pond Fishing and Country Club just outside St. John’s. Here she met St. John’s businessman Harold MacPherson (1885-1963), the owner of Royal Stores located on Water Street (Paddock 1991: 425-26). MacPherson indicated that he had an employee who sang traditional songs and suggested that Sargent might like to meet and record him. Sargent headed to Royal Stores on 28 August, where MacPherson introduced her to Louis Burry, an elderly packer who was originally from Greenspond, Bonavista Bay. McPherson granted Burry time off and provided Sargent with a room where she could record him singing. Over the course of two days she collected ten songs from Burry. These included “Faithful Sailor Boy,” “The City of Boston,” “The Bolina,” and “The Alphabet Song” more commonly known as “The Sailor’s Alphabet.” Burry also provided Sargent with “Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis” and an Irish number “Behind McCarthy’s Mare” (Blouin 1982).[70] This interview with Burry ended Sargent’s fieldwork in Newfoundland.

Figure 4

Fiddler Tom Jennings.

Margaret Sargent left St. John’s on 31 August. Stopping briefly in Cape Breton, where she gave a presentation on her Newfoundland work to the Alexander Graham Bell Ladies Club of Baddeck, she returned to Ottawa in mid-September. In late October she headed off to British Columbia to marry Kenneth McTaggart. Shortly thereafter, with her new husband, she moved to Vancouver where he took up a teaching position at the University of British Columbia. She left her tape recordings at the Museum but no report of her Newfoundland activities.

Although after this Sargent was only distantly linked to the Museum, and the Newfoundland field trip was her first and last venture of this sort, her work had influence. Based on the wealth of information she acquired during this brief field trip, the National Museum subsequently decided to continue with its investigations of Newfoundland folk music. On Sargent’s recommendation, the following year Kenneth Peacock was awarded a contract to go to the province to carry on the research, eventually publishing his findings in a three volume work Songs of the Newfoundland Outports (1965) (Guigné 2004: 207).

Sargent’s own assessment of her work is complex. She considered her collecting to be less important than Peacock’s. Reflecting back on her experiences in 1998, she commented that her fieldwork was rather insignificant in comparison to Peacock’s subsequent research. Her minimizing was in part due to the fact she had not had the chance to see her work published. Nonetheless, there is evidence that Sargent had begun to set out some ideas regarding her Newfoundland experiences.

When I set out from the National Museum to collect folk-songs in Newfoundland I had only a vague idea of the kind of country I was going, and what I could expect. About Newfoundland itself I had been told that it was a barren bleak place with plenty of rain. This resulted in packing a raincoat which I used only once and a pair of rubber boots which I used not at all. About its songs, I had seen the two books published by Greenleaf and Mansfield and Karpeles and the one prepared by a St. John’s merchant Gerald S. Doyle. Newfoundland has 2 kinds of songs — a repository of English ballads, Nfld, Compositions about everyday life. I came with the preconceived idea that the ballads were the most valuable. I left with the realization that Nfld songs were the thing… Nfld songs are alive. Some of them are written by local figures, others by unknown fishermen. They mirror everyday life — both in the outports and in St. John’s.[71]

When looked at in its entirety, Sargent’s collection, consisting of field tapes, photographs, notebooks, and her correspondence with Barbeau, is basically an unprocessed bundle of field data. Her comments regarding the people she saw and interviewed are spread throughout her six notebooks. By sifting through all this material and then comparing it with her field tapes and notes in the photograph albums, information emerges both regarding her field experiences and about Newfoundland song traditions. As a typical example, at the back of a book Sargent used to note the photographs she had taken, I found references to her recorded interview with Louis Burry.[72] She had listed the various songs he provided her during their recording sessions. This information was useful when screening her field tape.

Although she was not able to record songs in Branch, I discovered that she had taken down the texts for sixteen of them. For the songs “Young Charlotte” and “Reillie” she had also transcribed the texts and melodies. These I found at the back of one of her photograph albums.[73]

The back of her photograph albums also contain both hand and typed transcriptions of Burry’s rendition of “The Alphabet Song” along with the musical transcription. A close reading of the intersections of her recordings, notes and photographs promises to reveal more insights.

If we consider that Margaret Sargent was on an exploratory expedition to ascertain what kinds of material might be viable to collect, this small collection of recordings, field notes and photographs, assembled over fifty years ago, is of considerable value for its depth and diversity. During her stay she successfully managed to locate and interview informants from three different areas: St. John’s, Torbay and Branch. She recorded seven of these informants on tape; musician Bob Macleod, librarian Marjorie Mews, archivist Leo English, and W. J. Bursey all from St. John’s, Tom Jennings of Torbay, John Joe English, of Branch as well as Louis Burry originally from Greenspond but residing in St. John’s.

Her notes and correspondence reveal much about the logistics of doing research in Newfoundland, offering a new context for considering both her activities and her findings and a more appropriate means to reevaluate her contribution to folklore and music scholarship in this area. The various people she met in St. John’s provided her with valuable information on aspects of Newfoundland and its cultural traditions. From Leo English, for instance, she learned a little more about the diversity of folklore in Newfoundland. He introduced her to various legends, information on medicinal cures, songs and local sayings. People such as English could at least point her in the right direction.

Her musical collection offers a rare opportunity to listen to music that may not be available elsewhere. Because of this, Sargent’s sound recordings represent an important resource for future scholars in several areas. For example, Sargent’s recordings of Tom Jennings playing the fiddle are of note because she took the opportunity to collect this material at a time when other collectors might have overlooked it. Although Leach acquired various examples of instrumental music while he was in the province in 1950 and 1951, he did not collect tunes played on the fiddle. Forty-seven of the sixty-three songs Sargent acquired during her field trip are on tape and these are of historical interest because, as in the case of Leach’s material, they are also some of the earliest extant sound recordings. Furthermore, her recordings of Bob Macleod are important for what they reveal of an early cultural producer. As we now know today, Macleod was a main link in the dissemination of Gerald S. Doyle’s variety of Newfoundland folksong to the mainland. Through his work with Doyle and his performances of this material, Macleod was also one of the few knowledgeable people in St. John’s who could speak about that aspect of Newfoundland folksong. His conversations with Sargent indicated an attempt to educate her on the activities of the balladeer Johnny Burke, and aspects of the songs which he found interesting. Macleod supplied ten songs including “Kelligrews Soiree,” “Lukey’s Boat,” and “Jack Was Every Inch a Sailor.” In particular, Sargent’s recordings of his “H’emmer Jane” and “Feller from Fortune” are the earliest of his performances of these songs. Sargent’s recordings now allow us to hear Macleod’s specific interpretations of Newfoundland folksongs.

The thirty-seven other sound recordings, as performed by such singers as Louis Burry, John Joe English, and W. J. Bursey, cross over a broad spectrum and include local compositions, American and British broadside ballads, as well as American and Irish popular songs. Here too are materials of special interest. The singer John Joe English of Branch had an extensive repertoire. He was recognized in the community as a good performer of recitations and songs. Sargent was the first of many researchers to document his repertoire. As the small sampling of material which he gave her suggests, his repertoire was wide-ranging. Sargent’s recordings hold value for future scholars who continue to document English’s life and material and to consider his contribution to our understanding of traditional performance in Newfoundland.

Sargent experienced and recorded aspects of folklife in ways that other folklore collectors did not. For example, her observations of life in Branch and St. Brides provide a realistic contrast to Peacock’s Newfoundland work which started a year later. Sargent readily made note of the desperate living conditions which she experienced first-hand in Branch; low fish prices associated to the truck system which placed fishermen at a disadvantage, lack of clean running water which led to diseases such as summer complaint, lack of electricity and the out-migration of women to St. John’s to go into service. Her observations help us to better appreciate the challenges of living in outport Newfoundland at mid-twentieth century. Her efforts to document various aspects of material culture are also of merit. Her photographs of Bowring Park, the craft movement, Branch houses and doorways, all capture aspects of Newfoundland culture in particular times and places that were not usually noted by researchers.

Sargent’s lasting contributions are in part due to her lack of previous collecting experience and her lack of formal training in folkloristics. She documented anything that was presented to her as folklore without filtering this material out or questioning its source[74] and her collection accurately represents the types of folk material one typically would find in rural Newfoundland at mid-century: songs from British and Irish traditions, locally-composed ballads, fiddle music, and recitations. Unlike Maud Karpeles who selectively searched out older material (Lovelace 2004: 284-298), Sargent’s notes on Branch and St. Bride’s indicate that she took an inclusive approach to fieldwork. Although she was interested primarily in obtaining folksongs, her fieldbooks contain descriptions of the everyday activities she encountered: a mundane evening playing cards, kitchen visits, foods she liked and disliked, descriptions of houses in the community and the personalities of individuals she met, notes on community activities, songs, anecdotes, and several recipes.

In this way, Sargent is typical of many early Canadian women collectors who have been perceived to be “undisciplined” in their approach (Tye 1991: 41). As this new examination of her work illustrates, although the material which Sargent acquired while in Newfoundland is unprocessed, the content contains a wealth of information about the places she visited and the lifestyles of the people. Rather than romanticizing Newfoundland and its folk culture, Sargent was frank in her observations about certain aspects of life in Canada’s newest province. A curious woman by nature, she appears to have been greatly affected by those whom she encountered and by what she saw. Her comments on people she met in St. John’s, Branch and St. Bride’s and her distinct experiences poignantly depict the economic and social separation between St. John’s and rural Newfoundland at that time period. Although the province was undergoing considerable economic change as a result of Confederation, the living conditions in many communities were still forbidding. Looking back upon the whole experience in 1998 she noted: “To us it was a Third World country almost, and I’m sure I was suffering from culture shock. In the outports there was such a contrast. The people were fine and hard working and very good looking and then there was this dire poverty. It was pretty awful[75].”

Sargent’s collection from Branch is valuable for contextualizing the material that Kenneth Peacock later gathered from Branch singers Andrew Nash, Patrick W. Nash, and Gerald Campbell. Although Peacock later visited Branch in 1961, he wrote nothing of his experiences nor did he share any observations with me when I interviewed him many times years later (Guigne 2004: 455-56). During Peacock’s six visits, he experienced rapid changes concurrent with similar disparities in the living conditions throughout the province but he chose not to record his fieldwork experiences, placing little emphasis on keeping diaries and fieldwork accounts.

No, I’ve never been the diarist sort of person. I know people do that sort of thing but I never did. It’s like trying to record your dreams, you know; you have these wonderful dreams. And I went through a period where I was writing everything down and then you read them a few months later and there’s just this stupid story. The dream is really an emotional experience and you can’t retrieve that from just reading about it[76].

Sargent’s notebooks, and her reminiscences of this time period, provide the missing contextual detail and a much needed balance to her successor’s later activities. Writing to Helen Creighton shortly before leaving the Museum in late October 1950, she appropriately summed up the entire experience like this.

The trip to Newfoundland was wonderful. The hospitality of the people both rich and poor must be seen to be believed. The folklore treasure there is astoundingly rich — largely I should think because it is an island and because it has been so little influenced by other countries.… I have only scratched the surface since it took me a while to become acclimatized and to make contacts. I left however with an overwhelming desire to return and follow up my beginning.[77]

While Sargent did not return to the field to collect as she had done in Newfoundland, she went on to contribute to the discipline in several ways. Shortly after her marriage, and with the assistance of Barbeau, Sargent applied for and was awarded a six-month UNESCO scholarship in 1952 to study at the University of Indiana under George Hertzog and at Cecil Sharp House in London under the direction of Maud Karpeles (Duke 1981: 843). By the late 1950s, to accommodate her family commitments which included two children, she shifted her activities toward projects that could be handled closer to home. Over the course of the next decade folklore research at the Museum gained a stronger footing under Barbeau’s replacement, Carmen Roy, who headed up the newly established Folklore Division at the National Museum of Canada. Roy regularly offered Sargent small contracts which contributed significantly to the transcription and cataloguing of folklore materials in British Columbia. In the 1960s, at Roy’s request, Sargent carried out a survey of folk music and aboriginal music sources in British Columbia (Sargent McTaggart 1967: 67-71). The British Columbia song collector, Philip Thomas, called on Sargent to transcribe his field recordings for two publications “B.C. Songs,” (1962) and The Caribou Wagon Road 1858-1868: The Opening of a Frontier. Documents in Song (1964). Under a grant from the Canadian Folk Music Society, Sargent worked with musicologist Ida Halpern, cataloguing musical instruments, tape and acetate recordings, and instruments in her collection as well as helping Halpern in making her recordings of Kwakiutl songs available. Sargent edited the booklet for Halpern’s 1967 album Indian Music of the Pacific Northwest (FE 4523) (Peacock 1969: 67).

With the exception of the song, “The Irish Foggy Dew,” which Sargent obtained from John Joe English and later passed to Peacock to include in Songs of the Newfoundland Outports, nothing of her Newfoundland work has ever been published (Peacock 1965, 2: 520-21). Understandably then, she has been excluded from historical accounts of Newfoundland folksong collectors and her work has gone largely unacknowledged. For this reason we often equate the National Museum’s folksong research in Newfoundland with her successor Kenneth Peacock. Yet, as this brief chronicle reveals, it was Sargent, not Peacock, who initiated the Museum’s Newfoundland folksong collecting program, paving the way for later research. With her groundbreaking 1950 fieldwork, Sargent effectively established the potential for folksong research in Newfoundland thereby advancing the National Museum’s anglophone folklore research program in Eastern Canada. Rather than viewed as belonging to the margins, Margaret Sargent should be appreciated for her substantial contributions both to the documentation of Newfoundland folksong at mid-twentieth century and to the field of Canadian folklore.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Anna Kearney Guigné

Anna Kearney Guigné holds a PhD in folklore from Memorial University of Newfoundland. Between 1995 and 2005, she worked as a sessional instructor for the folklore department and during this time taught courses on Newfoundland folklore, Introduction to Folklore and Folklore Research Methods. She is currently an adjunct professor for the MA and PhD Programs in Ethnomusicology, at Memorial’s School of Music. Her work has been published in several journals including the Canadian Journal for Traditional Music, the Canadian Folk Music Bulletin, Lore and Language, Culture &Tradition, and Contemporary Legend: The Journal of the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research. She is the 2005-2006 recipient of the Institute of Social and Economic Research’s postdoctoral Books Fellowship. Her publication Folksongs and Folk Revival: The Cultural Politics of Kenneth Peacock’s“Songs of the Newfoundland Outports” is forthcoming (ISER 2007).

Anna Kearney Guigné

Anna Kearney Guigné détient un doctorat en ethnologie de l’Université Memorial de Terre-Neuve. Entre 1995 et 2005, elle a travaillé en tant que chargée de cours au Département de folklore où elle donnait les cours d’introduction au folklore, de folklore de Terre-Neuve et de méthodologie en ethnologie. Elle est actuellement professeure associée au programme de maîtrise et de doctorat de la Memorial’s School of Music. Elle a publié dans plusieurs revues, y compris dans le Canadian Journal for Traditional Music, le Bulletin de musique folklorique, Lore and Language, Culture & Tradition et Contemporary Legend: The Journal of the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research. Elle a été récipiendaire de la bourse de publication postdoctorale de l’Institut pour la recherche économique et sociale en 2005-2006. Son ouvrage Folksongs and Folk Revival: The Cultural Politics of Kenneth Peacock’s “Songs of the Newfoundland Outports” est en cours de publication (ISER 2007).

Notes

-

[1]

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Folklore Studies Association of Canada Annual Meeting, 1998 Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Ottawa, Ontario, 27-29 May. I am grateful to Pauline Greenhill and Philip Hiscock and to the external reviewers for earlier readings of this work. Thanks as well to Diane Tye for her editorial assistance.

-

[2]

Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull Quebec, Library and Documentation Services (hereafter referred to as CMC), Fonds Marius Barbeau, Margaret Sargent correspondence, 1942-49, box 237.

-

[3]

I am grateful to Margaret Sargent McTaggart for subsequently placing a copy of this material at the Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive (MUNFLA), St. John’s, Newfoundland; see accession numbers 98-237 and 99-138. As all of her government field books are relatively similar, they are referred to in the text as Notebook 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6.

-

[4]

For a cursory inventory of her field tapes at the CMC see C. Blouin, “Index to Collection Sargent, M./Tower, L. Audio Documents, 1950. S.T-A-1.1 to 1.9,” Canadian Centre for Folk [Culture] Studies. Library and Documentation Services, 1982.

-

[5]

Margaret Sargent, letter to Marius Barbeau 11 Nov. 1941. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Box 237, f 11.

-

[6]

McTaggart, Margaret Sargent. Telephone interview by Anna Kearney Guigné, 21 April 1998.

-

[7]

Marius Barbeau letter to Margaret Sargent, 15 Feb. 1945. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Margaret Sargent Correspondence.

-

[8]

Margaret Sargent, correspondence with author, April 1997.

-

[9]

McTaggart, Margaret Sargent. Telephone interview by Anna Kearney Guigné, 11 March 1997.

-

[10]

Margaret Sargent, correspondence with author, 2 April 1997.

-

[11]

Although they arrived in the province more or less around the same time, Sargent was unaware of Leach’s activities. His sound recordings from this fieldwork have now been digitized; see MacEdward Leach and the Songs of Atlantic Canada, Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive and Research Centre for the Study of Music, Media and Place, http:// www.mun.ca/folklore/leach/, retrieved April 2006.

-

[12]

McTaggart, Margaret Sargent. Telephone interview by Anna Kearney Guigné. 11 Mar. 1997.

-

[13]

J. R. Smallwood Papers, 1949-1972, Centre for Newfoundland Studies Archive, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Coll- 075; Canada, Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources, file 3.20.021; Margaret Sargent, letter to Joseph R. Smallwood, 20 October 1949.

-

[14]

J. R. Smallwood Papers, 1949-1972; Coll-075, Joseph R. Smallwood, letter to Margaret Sargent, 31 October 1949.

-

[15]

J. R. Smallwood Papers, 1949-1972; Coll-075, Leo Moakler, letter to Margaret Sargent, 3 November 1949.

-

[16]

Carla Emerson Furlong. Interview by Anna Guigné. St. John’s, 19 June 1996.

-

[17]

Carla Emerson Furlong Collection, MUNFLA; Frederick Emerson Papers, Lectures and Musical Compositions, circa 1930-45, Accession 98-125; Frederick Emerson, unpublished lecture, [ “I am going to talk to you for a short time today…”], pg. 14.

-

[18]

Carla Emerson Furlong Collection, MUNFLA; Frederick Emerson, unpublished lecture, “The record of musical achievement in Newfoundland…”, pg. 4.

-

[19]

McTaggart, Margaret Sargent.Telephone interview by Anna Kearney Guigné, 11 Mar. 1997; Margaret Sargent letter to Miss Karpeles, 25 October 1949. CMC, Fonds Margaret Sargent, Box 353, f. 10.

-

[20]

Maud Karpeles letter to Margaret Sargent, 8 February 1950. CMC, Fonds Margaret Sargent, Box 353 f.12.

-

[21]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 1, pp. 1-3a.

-

[22]

Margaret Sargent letter to Marius Barbeau, 9 July 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Box 237.

-

[23]

For a discussion of this women’s organization see Linda Cullum, “Under Construction: Women, The Jubilee Guilds and Commission Government in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1935-1941,” Unpublished thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, 1992. See also the song “The Jubilee Guild,” in Kenneth Peacock’s Outports (1965, 1: 66-67).

-

[24]

Brewis is a traditional meal made of a hard bread or hard tack which is soaked in often served with salt fish; see G. M. Story, W. J. Kirwin, and J. D. A. Widdowson (eds.), Dictionary of Newfoundland English (1982: 65-66).

-

[25]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 4, pg. 6.

-

[26]

Sargent had also written to Howse shortly before leaving to come to Newfoundland. Margaret Sargent, letter to Mr. C. K. Howse (n.d.); and Claude Howse, letter to Margaret Sargent, 23 June 1950, CMC, Fonds Margaret Sargent, Box 353, f. 11; Margaret Sargent letter to Marius Barbeau, 12-14 July 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Sargent Correspondence.

-

[27]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 1, pg. 6a.

-

[28]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 1, pg. 7. According to Philip Hiscock of Memorial University’s Folklore Department, both men worked for the Colonial Broadcasting Corporation. Schulman was a morning show host while Murdock was a technician. Biddy O’Toole was the stage name for a female singer who performed local songs such as “The Star of Logy Bay,” and Irish Come All Ye numbers such as “Father Dear Father” and “O’Brien Has Nowhere to Go” at the Barn Dance held at the Knights of Columbus Hall in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The “Dance” was aired over VOCM radio on Saturday nights. My thanks to Frank Armstrong of St. John’s who provided me with his recollections of listening to this program as a boy.

-

[29]

Margaret Sargent letter to Marius Barbeau, 12-14 July 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Sargent Correspondence.

-

[30]

Margaret Sargent letter to Marius Barbeau, 12-14 July 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Sargent Correspondence.

-

[31]

Margaret Sargent, letter to Marius Barbeau, 12-14 July 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Sargent Correspondence. P. K. Devine was Gerald S. Doyle’s uncle and a key figure in promoting Newfoundland folklore. For a brief biography see Murray, “Devine, Patrick Kevin 1859-1950,” (1981: 614-15).

-

[32]

MacLeod’s friend, Lloyd Soper, would later perform both songs for Peacock just as he was beginning his field collecting activities in 1951 (Guigné 2004: 220-21). Peacock subsequently passed a transcript of the Soper version of “Feller from Fortune” to Gerald S. Doyle who then included it in Old Time Songs of Newfoundland (1955: 12; Guigné 2004: 258). “H’emmer Jane” is closely associated to the St. John’s tradition; performance of the song involves mimicry of the Newfoundland dialect. Edith Fowke notes that Bob Macleod learned it in 1939 or 1940 from someone in Indian Bay who had learned it while working in a lumber camp. Macleod performed the song regularly during the 1940s always with an overstated Newfoundland accent; see The Penguin Book of Canadian Folksongs (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986: 120-21 and 204n).

-

[33]

McTaggart, Margaret Sargent. Telephone interview by Anna Kearney Guigné, 11 March 1997.

-

[34]

For a detailed comparative study of one nearby community retaining strong traditional Irish patterns of farming, kinship, dialect and folkways see Mannion 1976.

-

[35]

McTaggart, Margaret Sargent. Telephone interview by Anna Kearney Guigné, 28 February 1998.

-

[36]

Margaret Sargent, letter to Marius Barbeau, 25 July 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Sargent Correspondence.

-

[37]

Margaret Sargent letter to Marius Barbeau, 25 July 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Sargent Correspondence.

-

[38]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 5, pg. 41.

-

[39]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 5, pg. 37. For a version of this tale see “The Sole” (no 172) in Joseph Scarl, The Complete Grimm’s Fairy Tales (1972: 709).

-

[40]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, pg. 31. For examples of her efforts to document the doors and houses of Branch see accession 99-138, nos 17920-17942; at MUNFLA also see Peter Gard’s photographic collection of Newfoundland doorways, Accession 80-197.

-

[41]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, p. 29.

-

[42]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, pp. 34-35.

-

[43]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, p. 48.

-

[44]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, p. 20.

-

[45]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, pp. 30-31.

-

[46]

Margaret Sargent, letter to Marius Barbeau, 21 August 1950. CMC, Fonds Marius Barbeau, Margaret Sargent Correspondence.

-

[47]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, p. 34.

-

[48]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 5, p. 44. For a discussion of the prominence of the disease in Newfoundland particularly up to the late 1940s see Patricia O’Brien, “Tuberculosis,” Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, vol. 5 (St. John’s: Harry Cuff, 1994: 430-434).

-

[49]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 5, pg. 50.

-

[50]

Margaret Sargent McTaggart Collection, MUNFLA Accession 98-237, Notebook 6, pg. 35.

-

[51]