Abstracts

Abstract

This article addresses the organizational and discursive dynamics of a green urban movement in Austin, Texas, and how one community found its voice and translated a significant current of opinion into an effective cultural and political force. Of particular interest is the production and deployment of assorted texts and cultural capital by environmental activists in full engagement with a no less determined multinational corporation. The objects and artifacts, as we observe them during a flânerie or “walkabout” of the town’s symbolic center, provide a rich interpretive source for understanding the culture and community which produced them.

Résumé

Cet article examine les dynamiques organisationnelles du mouvement écologiste urbain à Austin, Texas, et la manière dont une communauté particulière a pu se faire entendre et générer un courant d’opinion significatif qui s’est traduit en une réelle force politique et culturelle. Il est d’un intérêt particulier d’examiner la production et l’usage de textes thématiques et de capital culturel par les activistes environnementaux dans leur engagement plein et entier à l’encontre d’une entreprise multinationale aussi déterminée qu’eux. Les objets et artefacts que nous pouvons observer au cours d’une « flânerie » dans le centre symbolique de la ville nous procurent une source d’interprétation très riche pour la compréhension de la culture et de la communauté qui les a produits.

Article body

Though the forces that came together to create the uprising of the Paris Commune in 1871 were extraordinarily heterogeneous, they were all bound together by a common loyalty to the place they called Paris and all agreed that the liberation of Paris was a crucial aim.

David Harvey, Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference

The citizens of Appolonia Pontica, after having had one of the experiences already described, provided that the gates should be locked with a great hammer and the making of a tremendous noise, so that the locking or opening of the gates could be heard over almost the entire city; so ponderous were the fastenings and so strengthened with iron; and the same thing was done in Aegina also.

Aeneas Tacticus, On the Defence of Fortified Positions - XX

Introduction

People, Anthony Giddens says, make their own geography. But which people get to do what kind of geography-making can make all the difference. John Dorst (1989), Martha Norkunas (1993), and Chris Wilson (1997) have shown how dominant elites in southeastern Pennsylvania, Monterey, California, and Santa Fe, New Mexico have selectively appropriated cultural elements for the construction of top-down mythic narratives and a project of self-authentication and cultural production. In this article I offer the case of Austin, Texas, where citizens have constructed a progressive and resistant discourse that deploys the city’s natural setting and an array of supporting textual citations as ideological centerpieces in support of a new paradigm of nature preservation and sustainable urban growth. Here a broad alliance of activists and sympathizers have coalesced as a rhetorical community and co-opted aggressive private interests while pursuing initiatives that enlarge the public sphere and enhance urban quality of life in matters such as green space, clean air and water, species preservation, and regional development patterns.

Figure 1

An aerial view of Barton Springs Pool and downtown Austin from the Barton Creek greenbelt

Methods

As an overarching rhetorical frame for this ethnography, I borrow Ernest Bormann’s (1972, 1985a, 1985b, 1994) conception of social movements as rhetorical communities, converging around a core set of symbolic structures or rhetorical vision, and utilizing fantasy themes and assorted discursive strategies and devices which unify the community and trigger shared fantasies. With this “imagined” and “imagining” community as our framing device I believe we may approach this site, like John Dorst’s postethnographer (1989), by treating it as a kind of library or apparatus that “exists for and through the management of texts” (206). The ethnographer’s task then is to form the collection — selecting and arranging — and then “reading critically as a rhetorician” and unpacking the “ ‘motivations’ of the texts, reading them as historically situated” (206). As field experiences in human and discourse geography indicate, much of this arranging and collecting has already been done, in auto-ethnographic fashion, by on-site institutional interests (Dorst 1989: 206-209). Similarly, this Austin community has been actively engaged in this gatekeeping or curating function as they stage, by varying degrees of reflexivity, the citations through which this site is constituted.

Individual texts in the collection presented here are considered via a range of critical rhetorical techniques, from the cultural and dramatistic to ideological analysis. Our collecting and presentation is further informed by theories on communicative action and knowledge interests advanced by Jurgen Habermas (1984), as well as the insights afforded by a number of thinkers on human geography. For all this method and tradition, however, our “postethnographic” objective — following Denzin’s (1989) and Tyler’s (1986) turn on postmodern representation and poststructuralist ethnography — is a collection which effaces, as much as possible, second-order concepts and structures while foregrounding and evoking for the direct experience of my readers this community’s ethos and sense of ethical action. If the running analysis of our central Austin tour should seem a bit fragmented at times, this may be due to the fragmented nature of postmodern space. For some help with this and for the consistency of narrative commentary, I employ Walter Benjamin’s figure of the flâneur as our tour guide through this land and cityscape.

The Flâneur

The central galvanizing symbol which defines the collective identity of this community is Barton Creek and Barton Springs, which lie at the heart of the Town Lake environs. A columnist writing in the local alternative weekly, The Austin Chronicle, offers some hint of the synchronic reflexivity immanent in much green discourse.

Barton Creek is one of Austin’s most glorious natural treasures, and the Greenbelt surrounding it is an oasis of flora, fauna and natural beauty of the sort that can be found in few, if any, other American cities. To understand the importance of its preservation, one only has to take advantage of the many activities it offers: hiking, swimming, floating, biking, caving and climbing, or just relaxing along its banks... Barton Creek has been in continuous human use for some 11,000 years. The 120-square-mile Barton Creek watershed has an estimated 274 archaeological sites with remains from the Jumano, Comanche, Apache, and Tonkawa tribes. The indigenous people were undoubtedly attracted by the water and wildlife in the area. Some of the animals that live in the region include the endangered golden-cheeked warbler, painted buntings, green herons, great blue herons, woodpeckers, flickers, kingfishers, great horned owls, black vultures and turkey vultures, armadillos, deer, raccoons, grey foxes, field mice, rattlesnakes, coral snakes, turtles, numerous fish species, rare and endangered plants and a wide variety of insects and spiders.

Bryce 1992: 33

The writer also suggests how the community’s identity is enmeshed in what has been called place or body ballet (Seamon 1980), the intimate physical and psychic connection to a place such as, among many other things, a neighborhood, a beach, a woods. Such a connection between self and social space constitutes an affective intensity essential to the reduction of environmental stress and alienation (Wilson 1980: 145). Under extreme conditions, such a connection calls forth resistance and the defense of such a lifeworld. This connection is apparent in the spatial-behavioral patterns of citizens and in the quasi-religious and mystical language with which they describe their place and their place ballet, the intersubjective understanding of their urban geography.

Given these site dynamics, significant data for this study has been generated over ten years of participant observation and the researcher’s own bodily experience of the site. Strolling about the city has meant sitting in on heated city council hearings, hiking and biking the city’s greenbelt trails, kayaking its waterways, transcribing fieldnotes in downtown coffeehouses, leafleting the infinite expanses of apartment complexes, and driving a sound truck through green strongholds for one green candidate’s council campaign, and physically immersing myself in the creek when Texas heat and politics became too oppressive. Flânerie as a kind of ethnography has sensitized me, I believe, to the “psychodynamics of place” (Pile 1996: 229) and the conduct of ethnography as “embodied practice” (Conquergood 1991: 180)[1].

Accordingly, I believe that the textual density of this urban environmental movement, its spatial intensities, can best be read in the Benjaminian/Baudelardian fashion, in the solitary figure of the strolling, spectating detective. As a “critical ‘gumshoe’,” Benjamin strolled through Paris and the other great cities of Europe “excavating discursive structures, ruminating on the act and process of representation in the modern era” (Mazlish 1994: 57) and looking to particular instances in order to appreciate more general social currents and structures. For the critical theorist Theodor Adorno, whose own proto-postmodern microanalysis was derived from Benjamin, one looked to philosophy and art in their capacity to “construct constellations of ideas and images which can illuminate the particular and the broader social forces” (Best and Kellner 1991: 227).

Though more utilitarian in its ethnographic purposes, an Austin flânerie might sharpen our spatial and affective sense of the interpretative frame of the Lilliputians (the Save Our Springs Alliance) in fierce engagement with their Gulliver (the Freeport McMoRan Corporation, the development community, and the Texas State Legislature). Understand, however, that in this Paris, this Berlin, our Austin, we wear Adidas trail running shoes and that jogging (a measured, plodding jog) and “power walking” is our perambulation of choice. And unlike Baudelaire’s solitary dandy patently on the make, I will reference here one particularly representative Sunday outing, a morning in which my life partner, something of a flâneuse in her own right, states that she has something she wants to show me, a slight departure from our usual rounds. Taking her cue, we head out then on our run around Austin’s Town Lake.

On this Sunday, my partner reverses my preferred course and runs the hike and bike trail counter-clockwise on its six mile circuit, east to west from the bass and turtle pond and gazebo in the far northeast corner of Zilker park (abutting the southern edge of Town Lake the west side of the 1st Street Bridge), north across the 1st street pedestrian bridge, then west towards Austin High School, Lamar Boulevard, and Mo-Pac Hiway.

This is the heart of downtown Austin, the stronghold of the green resistance movement. These precincts directly to the south, west and north of downtown will produce a 75-90% affirmative vote on any green issue or candidate. Given the level of this intensity, one might predict that the alert and ever ready flâneur should be able to “read” something of this resistance and its attendant ideology in the found objects of this cityscape.

Urban Graffito

Had Baudelaire the advantage of accessing the runner’s natural high, he surely would have forsworn opium for good running shoes. Some minutes into our jog, with the steady rhythmic pompitypom of my heel-striking gait, a deep and even breathing soon settles me into the jogger’s trancelike state and brings a slight surreal focus to my thoughts. And with the steady pompity pom pom ten to fifteen minutes into the run I espy the Missouri-Pacific Railroad Bridge. Through an endorphin haze I appraise the white scrawl of letters blazing defiantly upon the Mo-Pac train bridge; I appraise it as tens of thousands of other joggers, strollers, and cyclists have appraised it for years now, in all its suggestively urgent, quasi-hypnotic suggestiveness: RIP JIM BOB.

Some brave heart has slipped off the east bridge side, steadied herself precariously with the thinnest of hand and toe holds to paint this terse statement which stands as a double signifier: as the imperatively aggressive “RIP Jim Bob” (go vote in discordance with Jim Bob’s interests) or acceding the past tense, “Rest In Peace, Jim Bob” (the rippers got their man: turn out the lights, the party’s over).

All the collective affect and emotionality attendant upon the Barton Springs habitus may have remained indefinitely and politely in the urban background, however, were it not for one Jim Bob Moffett and a June 7, 1990 all-night city council meeting. On that night nearly a thousand Austinites converged upon city hall to protest the developer’s plan to convert 35,000 acres of green space bordering Barton Creek, to the southwest of the city, into an exclusive community of championship golf courses and gated executive communities. Freeport-McMoRan, a multinational mining and engineering firm, not only owned the largest gold mine in the world, but it also had the dubious distinction of the being listed as the nation’s number one ranking water polluter. Most alarming to Austinites was their hydrological understanding that any pollution of the Barton Creek watershed would quickly imperil Austin’s beloved and fragile Barton Springs, a large spring fed swimming pool maintained by the porous, limestone-filtered subterranean inflows at a cardiac-arresting 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius), and described by an issue of that year’s Outside magazine as the “finest dunk in the Southwest”.

The New Orleans based Freeport corporation and its combative CEO Jim Bob Moffett — a square-jawed, tough-talking, five o’clock shadowed ex-lineman for the Texas Longhorns — would readily provide the villainous foil that good rhetorical fantasy and an activated rhetorical community requires: a significant cadre of Austinites would quickly enter into a process of collective identity formation that would over time transform the local political process and the material conditions of their locale.

In the weeks before the critical hearing, key city councilors had been conceding that Freeport “had done its homework” (N. Scanlon, personal communication, May 14, 1996) and that the approval of Freeport’s development plan for public utility district was a near fait accompli, but the large and raucous June 7 turnout in support of Barton Springs and Barton Creek persuaded a stunned city council to cast a unanimous 6:00 a.m. vote against the development plan.

To my mind, our “Rip Jim Bob” graffito is patently an Earth First! action. It is also patently urban graffito, not unlike the roadway semiosis, which advised one how to act or not act in the ancient city. Consider here the bodies of criminals in medieval stocks or, more desperately and fatally, of criminals upon the Roman pinions, or the propped up caskets of ne’er-do-wells in American frontier towns. And so it is here in our postmodern city that citizens may reflect upon this sign with varying degrees of aerobic consciousness, this symbolic corpse of Jim Bob hoisted ceremoniously over our lake. “Pollute not our water, all ye who enter here”.

We jog on, crossing to south Austin via a walkway suspended under the Mo-Pac Bridge. One is free to look west then east, up and down the scenic Colorado River which courses easily through the center of our town, Mediterranean style mansions to the west, a rowing team lapping down river, eastward to my left. At the south end of the foot bridge, where I expect to go left, my partner sprints straight, motioning me forward to a further knoll, towards an area of Zilker Park circumscribed by the Botanical Gardens.

The Nature Center

After a short quarter mile we come to a long row of exhibit booths facing the path. A flyer tells us that this is the forward checkpoint for Safari 98, a joint production by entities called the Natural Science Guild of Austin and the Austin Science and Nature Center. Guild literature describes itself as “a nonprofit all volunteer support organization” whose goal is “to educate children and adults to appreciate, respect, and protect the environment”. The Science and Nature Center describes itself as “Austin’s premier environmental education facility”, a “living nature museum” funded by the City of Austin’s Parks and Recreation Department and grants. Its mission is to provide individuals, families, and groups with educational and recreational opportunities which increase knowledge, awareness, and appreciation of the Central Texas natural environment and its connection to other world ecosystems (Austin Parks and Recreation 1998).

Through such educational and textual practices, organizations such as the Nature Center and the Natural Science Guild contribute to the rhetorical community’s ongoing struggle to win hearts and minds. The subtlety and ambition of this project in its attempt to bridge diverging life worlds and life forms is soon evident as we follow a narrow asphalt road that ascends into a Hill Country tableau. Suddenly my partner breaks into the brush, down a path and onto a trail walk, part of the Center’s exhibit. Less than one mile long, the semi-steep trail takes you down into a riparian area along one of the contributing creeks to the Colorado River. Sizable boulders, tossed along by violent floods, rise up in and along the dry creek bed, and we are suddenly surrounded by steep vegetation covered cliffs. We could be in the wilderness. Along the trail, tutorial stations invite you to stop and cover your eyes, for instance, and “listen with the ears of a fox” or cover your ears and “see with the eyes of an owl”. Other stations point out unique geological features of this natural area. In the near background one hears the ceaseless hum of automobile traffic on the Mo-Pac freeway.

After ascending the trail out of the small canyon we come to an exhibit of birds — hawks, owls, ravens, falcons — injured in the wild or confiscated from errant citizens who were illegally keeping them as pets. As we enter the complex proper there are exhibits of aquatic life, wildflowers, and land born creatures. Today, young children with parents in tow are poring over “hands-on” exhibits, “discovery cart” presentations, animal demonstrations, and discovery boxes. An array of child-friendly exercises, which is — we are reminded by the literature — “Open to the public seven days a week, admission-free”.

On the other side of the complex is an elaborate feature called The Land Before Time. Established as part of a Young Explorers program, this exhibit includes a full sized waterfall and a Hill Country stream feeding into a large pool or small lake. The exhibit overviews the origins of similar Hill Country topography. Explorers can ride a paddle boat and participate in various interactive activities. During our chat with Freddie the Turtle, we are invited to open our Explorer’s Kit and take the temperature of the air and the water, to see if it’s a good day for Freddie to be out and about.

In this interactive exhibit we see how the tone, style, and fantasy themes of our rhetorical community are associated with the several dimensions of knowledge interests endemic in the new environmental praxis, along the lines suggested by Eyerman and Jamison (1991), following Habermas (1984). In terms of organizational praxis, for example, there are very anti-elitist sentiments at work here as natural scientific expertise is demystified and humanized in the context of “exploration”. Consonant with new environmental movements generally, scientific knowledge production at this site is framed as a democratic enterprise (non-gendered, non-ageist, trans-classist) accessible to anyone with a little background knowledge and a few tools.

Local movements form an identity particular to their birth site (Eyerman and Jamison 1991: 67). Here, the strength of this green movement is in its capacity to meet the whole of its public, to fashion a family oriented and family friendly practice. This “guild” project is an institutional and cultural move, imprinting the capacity for interacting with the environment at a very young age. If the SOS Alliance or Earth First! were so bold as to begin a recruitment and training program for youngsters fresh from the cradle, this Center approximates what such a programming effort might look like. Monitoring air and water is important and this is the technology with which you do it. Here we see systems ecology appropriated as social and political action in public space, where science is a kinesthetic, bodily experience.

The Center is singularly Austin and this is a singular act of organizing practice, cultivating the knowledge interests of our urban movement through deep cultural work. In a few years, the children seen here might opt for service with the Lower Colorado River Authority’s River Watch, a network of students and other citizens who monitor the water quality of creeks that feed the Colorado River.

I see the Science and Nature Center and the Natural Science Guild as textual registers for the density of the urban movement. First, the alliance is diachronically dense in its capacity to deepen its recruiting base through the artful articulation of an ecological worldview, thus extending the lines of environmental struggle well into the next century. And second, the site registers a synchronic density, as one observes the number of exhibitors at the check-in area who have chosen to exhibit their organizations and their particular forms of knowledge interests: the Austin Astronomical Society, the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve, Central Texas Herpetological Society, Cub Scouts, Eco-Fair, Horned Lizard Conservation Society, House Rabbit Resource Network, International Society for Endangered Cats, Keep Austin Beautiful, Perdernales Electric Co-op, Primitive Doin’s, Star Date Magazine-McDonald Observatory, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Travis Audubon Society, Travis County Archeological Society, Travis County Parks, Westcave Preserve, Wild Basin Preserve, and Wildlife Rescue, Inc.

The density of organizational interests and textwork on display here resonates with the density of individual and organizational interests that reached a critical mass earlier in the decade. Greens would build on the momentum of the June 7, 1991 hearing as a constellation of local environmental groups organized themselves into the Save Our Springs Coalition (SOS). In record time the group gathered the signatures which led to the passage of the United States’ first citizens’ initiated referendum governing water quality on a 1992 ballot by 66% of the voters.

In May 1993, a slate of three SOS endorsed candidates were swept into office to establish green majority control of the council. By May 1997, environmentalists completed a 7-0 green sweep of the council, as an SOS endorsed mayor and two new councilors stepped up to the dais. Subsequently, the council pursues an ambitious “Smart Growth” strategy and annexes 14 adjoining jurisdictions, partners with private development interests on core inner-city projects, and pursues an unprecedented expansion of green space and park lands. The council successfully defends its initiatives against reactionary forces vowing to “take back Austin” and vigorously contests a spate of “Austin-bashing” legislation — a biennial sporting tradition in the Texas state legislature — intended to abrogate Austin’s home rule prerogatives. With the luxury of the Parks and Recreation budget under its direct control, the green council would generously fund Town Lake projects such as the Natural History Center as well as several important Zilker Park exhibits we observe next.

My partner and I retreat from the hilltop, down past the exhibitors, back down from the grassy knoll through the support columns of the Mo-Pac Bridge spanning Town Lake (graffito on a Mo-Pac support column at the Barton Creek span: NO JOBS ON A DEAD PLANET) and resume our trail run eastward. A mile later we come to the Barton Creek outlet to Town Lake. Passing a small lookout gazebo, we proceed south along this small tree lined bayou. A father and young son fish from a small beach-like access point. Nearby, several couples with children feed ducks and geese, while yards away out on the water other couples negotiate their canoe northwards towards the lake, while other canoes move up river to the city’s rental station where Earth First! activist Neil Tuttrup holds a city job renting out canoes, while simultaneously monitoring the creek. Dogs on leashes enjoy the morning. Babies whiz by in jogging buggies propelled by well-conditioned parents.

Zilker Pool: Splash!

Beyond some picnic grounds and an extensive playscape we arrive suddenly at the Zilker Park pool bathhouse, faced (as noted by a 1948 Architectural Digest) with “creamy Austin stone” and “featuring open-sky dressing courts” (as cited in Pipkin and Frech 1993: 50). The pool is not yet busy. A wooden kiosk near the exit turnstiles reviews the historical particulars of the pool and an origin myth.

The cosmological dimension of the community’s rhetorical mythos is reproduced at this kiosk in an Indian myth recounted by Frank Brown in the Annals of Travis County and the City of Austin (1875). According to this text, a rainbow was cast by the Great Spirit with so much force against a rock that it shivered asunder: “whereupon Barton’s celebrated spring... gushed forth from the mountain side, and a portion of the brilliant bow, having mingled with the waters of the fountain, caused the beautiful prismatic colors reflected from the depths of its waters” (Pipkin and Frech 1993: 11). This appropriation of a native cosmological narrative (and by extension appropriating the presumed intensities of the indigene’s relationship to his ecology) in order to create connections to the present place and time is a recurring move within green movements, animating member identities wherever they may be constituted (Eyerman and Jamison 1991: 74).

In another part of the complex, past the pool gift shop, a diorama is under construction. This new half-million-dollars Zilker Park exhibit, Splash! Into the Edwards Aquifer highlights the technological dimension of the Alliance’s educational project, as it illuminates the hydro-geophysics of the region that allows rainwater ten miles away to end up in this pool. On the day Splash! opens, the Austin-American Statesmen offers this gloss:

Utilizing computer animation, [this is] a lively, kid-friendly introduction to the geological history of the Edwards Aquifer. A model representing the major geological strata within the Edwards Aquifer surrounds visitors. At another station, with the push of a button, visitors activate the Aqua Scape model, which demonstrates the geography and hydrology of the Edwards Aquifer. Special effects include simulated rain and lightning. At another station visitors can follow rainwater from Barton Creek in the Hill Country to Barton Springs, to the Colorado River, then down to the Gulf of Mexico. Four aquariums display plant and animal life native to each region. In the last part of the display evaporation is explained, showing how the cycle begins again. In the Mad Scientist Zone “everyone gets to be a scientist” with a hands-on station which encourages a fun experimentation in water analysis. You can search for mystery bacterial sources in the aquifer with help from the on-screeen “Captain Splash”, analyze water from Austin creeks or use a giant magnifying lens to identify different bugs. Towards the end of the exhibit, three hands-on stations show how development affects our water. The Stormwater Simulator compares water flow through urban and rural surfaces. Erosion velocity is observed as water flow and speed are increased in a circular tank filled with materials. At the Pollution Prevention Ponds, you see the effects of runoff from a parking lot and into a detention pond.

Austin-American Statesmen, October 17, 1998: Section C1

The exhibit is open to field trips where teachers can take a $10 training session and then lead their classes through for free. Otherwise, two-hour guided tours for children or adults are $2.50. Three years in the planning, the exhibit’s construction cost nearly a half-million dollars. Contributors include the original coalition of groups as well as the Austin Nature and Science Center, the Austin Parks Foundation, the Austin Parks and Recreation Department, the Barton Springs Diving Championships, The Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, the Water and Wastewater Utility’s Center for Environmental Research, the University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology, the Lower Colorado River Authority, Save Barton Creek Association, Friends of the Summer Musical, Drainage Utility Department and the Junior League of Austin.

Figure 2

Barton Springs place-ballet

Top to bottom: Scenes from a water festival; a blessing from Tibetan monks; a diver’s finish.

Here we note the striking density of organizational affiliation, even in its most tertiary aspects with respect to formal Alliance membership, but sharing such knowledge and cultural interests as to constitute a hegemonic valence. This exhibit-as-artifact constitutes one more fortifying move in the defense of its newly won position, another brace of precautionary fastenings on our city gates. But for all these martial metaphors, these agonistic flourishes, the emblem of the Splash! exhibit is one cheerfully oversized, sparkling water droplet. While this logo is resonant with the instrumental, concentrated focus of the Alliance, at the same time it conveys all the joy and pleasure that a little rain and water can bring to the semi-arid Southwest. This logo is the semiotic depository of all the affect conjured up by one long campaign begun at the start of the decade.

I see this as yet another feature of this city’s built environment, consciously constructed by a challenging group with an eye to consolidating its hold on history, urban policy, and everyday practice, creating the structural conditions by which its knowledge interests might vault to the future.

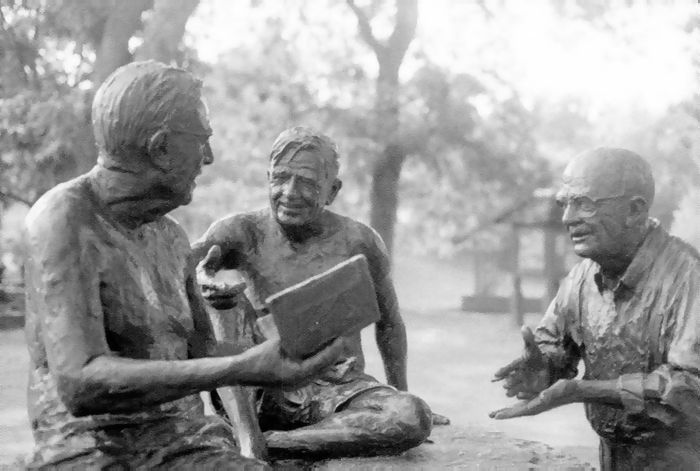

Philosophers’ Rock

Entering or exiting from nearly any direction in the Zilker pool complex one must eventually confront the life-sized statue of Philosophers’ Rock. Here, three fast friends and “fathers of Texas letters” — Roy Bedichek, J. Frank Dobie, and Walter Prescot Webb — are frozen in a moment of vigorous conversation upon “Bedi’s rock”, a rock in Barton Springs which achieved modest notoriety by virtue of their frequent attendance (Wright 1993: 51).

This statue first appears on the Zilker Park grounds in the early 1990’s. I would offer that this work’s appearance coincides with the shifting power differentials at city hall. Like all public commemorative monuments this one is a rhetorical product which selects from history “those events, individuals, places, and ideas that will be sacralized by a culture or a polity”, and lifts from “ordinary historical sequence those extraordinary events which embody our deepest and most fundamental values” (Schwartz 1982). Moreover, as Blair, Jeppeson, and Pucci (1991) advise

commemorative monuments “instruct” their visitors about what is to be valued in the future as well as in the past. As Griswold notes, “the word ‘monument’ derives from the Latin monere, which means not just ‘to remind’ but also ‘to admonish’, ‘warn’, ‘advise’, ‘instruct’”.

Blair et al. 1991: 263

To what is a Zilker Park visitor being advised? How are we being instructed? Eschewing the rhetorical neutrality of modernist architecture, this monument is decidedly regional and vernacular in style and tone. Not only is Philosophers’ Rock, as I see it, “sympathetic” to its natural setting, it colludes seamlessly in an act of highly localized story telling. Lawrence Wright gives us something of the story line, writing in the coffee-table tome, Barton Springs Eternal, that the statue of Dobie, Webb, and Bedichek

Figure 3

Philosophers’ Rock

“The polis, properly speaking, is not the city-state in its physical location: it is the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between people living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be” (Arendt 1958: 198).

... is a valedictory farewell for the very qualities these men embodied (whose) greatest gift to themselves and their community was their friendship. Wit and humor, biting and intelligent conversation, an open and accessible humanity, a love of teaching and an endless quest for learning — these were attributes that made these men heroes to our particular place and time... Barton Springs is a part of their legend. Bedichek became such a fixture at the Springs that his perch is still called Bedi’s rock. Most afternoons Dobie would join him, and the two of them would hold court. Webb, who didn’t swim, would come by for picnics. This is how they are so fondly remembered in Austin. Barton Springs is more than the setting where they worshipped nature. It is the community bath where they joined their neighbors. It is the matrix that held them together in its pure, and purifying, artesian embrace. The statue... commemorates not only their friendship but also their love of this place. In honoring them this way, we pay homage to our own love of Barton Springs and its spiritual power to bring us together in mutual shivering appreciation.

Wright 1993: 51

Tempo and vitality. Nature and spirit. A place-based community ballet. Philosophers’ Rock inscribes the uniquely constituted values of this urban movement, putting the “social” back into “new social movements”. The memorial appropriates a thread of social democratic values that is often lost in political identity movements.

The postmodern commemorative work, according to Blair et al., “gestures toward its surroundings and users”, and is “characterized by an interrogative, critical stance” (1991: 264). Seamless in its life-sized representation with the rest of the pool complex, we see here three citizen bathers reclined upon a rock. Children wend their way over, onto, and between our heroes, and the “close grained” details and accessibility invite such interaction. Unlike monuments hoisted many feet off the ground, the better to impose and be revered, the Philosophers’ Rock is for many children but an extension of the nearby playscape. Unperturbed, the philosophers continue their vigorous engagement. Older curious children might ask, eventually, what could the topic be here that roils them so? Surveiling parents often move in for a closer look, to read the plaque-bound commentary. What might these commentators have to say, the present day citizen-reader is asked, of Jim Bob Moffett’s private preserve in the Hill Country?

As a postmodern structure Philosophers’ Rock “references” its surroundings, makes “citation” of the regional and historical motifs inscribed in its structure. Here, I believe we are told: Talk matters. Nature merits our passion, our reflection, and our discourse. Mary Arnold, a longtime green activist, is explicit about what the monument meant for the movement. “It legitimated”, she says, “what we were all about, what we had been saying all along for years”.

The Stevie Ray Vaughn Memorial

We jog on, my partner and I, out of the pool and playscape complex, north along Barton Creek towards Town Lake, eventually crossing the creek by way of a small wooden bridge from which one can see downtown skyscrapers picturesquely framed between tree lined creek banks. We proceed along a veritable boulevard of a trail (wide with a gentle slope for efficient rain runoff) bordering Town Lake. A mile later, we break out into an expanse of park. To the right, the civic auditorium broods like a great gray and rusty mushroom. From its main entrance, however, a concrete walkway extends northward, crossing an avenue, continuing tree lined through the park and culminating, lakeside, in the larger-than-life-sized figure of Stevie Ray Vaughn. Vaughn, a noted Austin based blues guitarist, was killed when his helicopter pilot, disoriented by a fog bank while exiting a Wisconsin rock concert, crashed the machine into a hillside.

Figure 4

Stevie Ray Vaughn memorialized “as much for his mythic image — the guitarist as border gunslinger in the Clint Eastwood/Sergio Leone mode — and his tragic end as he is for his artistry” (McLesse 1999: E1).

The eight foot tall statue, with Vaughn attired in his signature bolero hat, trail duster, and substantial boots, gazes to the south/southwest, guitar at his side, with the downtown canyon to his back. The Vaughn memorial was unveiled on November 21, 1993. I believe this commemoration, like the architecture noted by Jencks and Sterns (as cited in Blair et al. 1991: 268), can be seen as postmodern-styled “story telling” or communicative art: like Philosophers’ Rock in the north of the park, Vaughn is carefully set in a cultural and physical context.

Statues offer indices of what counts for what. And the Vaughn statue is a testimony, surely, to the music industry that is a significant presence in the local economy, but also an industry that also made a significant contribution to the fundraising coffers of the SOS Alliance. In the early going, as to this day, musicians played at hundreds of annual fundraising events. Jerry Jeff Walker currently chairs the SOS Alliance. Don Henley, a native Texan and founding member of the Eagles rock group, has contributed tens of thousands of dollars to the support of green referendums and candidates. Bill Oliver’s song “Barton Springs Eternal” receives airplay over public radio station KUT with the intervention of every mini-crisis.

But beyond mere political economics, music of some form or fashion — blues, folk, rock and roll — has always been a close fellow traveler with the new social movements. Music captures and manages the attention of publics and heartens the troops. Tim Jones of Earth First! proudly offers that the ranks of his group, and the EF! leadership in particular, are well represented with “troubadours and minstrels”.

The Vaughn statue can certainly be appreciated on its own merits as an acknowledgement of the man’s life and art. Pilgrims trek to this spot daily to take photographs and leave flowers. But I believe the Vaughn memorial also registers another power current at this site. This is not, after all, a larger-than-life-sized statue of Jim Bob Moffett or Bob Dedman, orange-blooded champions of commerce, but of a quick-handed master of the electric guitar and of a particular blues guitar and vocal styling — insistent, edgy, bathing listeners in balladic crescendos of sound. And that finally is, for this reader, what registers semiotically in this work — the accentuation and celebration of Vaughn’s signature gun-fighting stance. This stylization captures something of the agonistics, if not the psychodynamics, of the OK Corral conflict that has been waged here this decade. Could it be otherwise? Under stress do we not fetishize those objects of our concern and revulsion, appeal to the gods for our city’s protection, the security of its walls? By his posture and his siting, I see Vaughn as proxy for the SOS Alliance, its back to the watercourse, a steely eyed mariachi duelist waiting, silent, eternal (“The price of Barton Springs is eternal vigilance” our SOS Legal Defense newsletter banner tells us), weapon at his hip ready to pounce upon any black-hatted developer villains. This is my city. Our drinking water. See there, hanging by yon train bridge, what becomes of “no count” water polluters[2]. Vaughn-cum-SOS Alliance is town sheriff, our Paladin, our fetish version of those hundreds of life-sized Chinese terra-cotta warriors posted at the palace gates. I believe my reading here is consistent with this community’s overall rhetorical style.

Downtown

We jog on, my partner and I, to the Zilker gazebo for a stretch, water, an impromptu shower, and a discreet towel off and clothes change by our vehicle. We head north across Town Lake on the 1st Avenue Bridge for a Sunday morning brunch. We take our eggs poached at the Hickory Street Bar & Grill on Congress Avenue and our espresso steaming at the Little City Coffee House, a block further north towards the capitol.

The Hickory Street Bar & Grill has been home to monthly meetings of the Save Barton Creek Association for several years and it would seem a fitting place, comfortable and homey with its heavily wooded features, sturdy ceiling beams, wainscoting, a worn floor. Around the entire expanse of the interior is a photographic archive of Barton Springs in the early part of the twentieth century. The Colorado River and Barton Creek at full flood in 1935. Nineteenth Century Austin gentlewomen in long skirts and frocks, gentlemen in starched collars, dark jackets, and ties posing at the edge of the springs, courting, picnicking. Other photographs show smiling locals, young women, bolder, in Flapper-era swimming attire. A later, pre-World War II era photograph shows yet another generation of young women suspended out over the water, their bare legs dangling from the steam shovel bucket used to enlarge the pool. I take Hickory Street as yet another cultural trace, a bass note here at the city’s interior, a mark of the city’s centurylong love affair with the creek and fascination for the water resources of the region. As early as 1853, we are told, the July 4th holiday was being celebrated at Barton Springs. Even as the city has matured from cow town to high-technology manufacturing center, this relationship between a townspeople and their water resources has endured. Certainly, something of the people’s libidinal and bodily attachment to the creek can be observed even in these old photographs.

We repair to the Little City Espresso Bar, a block north toward the Capitol building for post-breakfast espressos. We might have gone to the Ruta Maya Coffee House a few blocks further to the east. Either way, signs of resistance can be found even in these dark and aromatic corners of the downtown district. At the Ruta Maya, we might have seen upon the back “announcements” wall near the entrance to an enclosed tobacco shop, a “Wanted” poster bearing Jim Bob Moffett’s dour and threatening visage.

At Little City Espresso Bar, celebrated by a New York Times feature writer for its Soho minimalism, there is one bit of animated and affective excess. The careful flâneur will notice a piece of contemporary metal sculpture, the length of which entwines the corner pole of the patio-style smoking area. Looking closely one sees that the sculpture is in the form of a spare tree, and that in the tree are the figures of small birds, several of them in nests holding determinedly to field cannon, machine gun “nests” as it were, looking outward to some unseen threat. The work is the creation of Austin sculptor Barry S. George who held a Little City opening in the early nineties, featuring several other metal work pieces. In one piece, a dog, a caricature of Jim Bob Moffett, relieves himself on the state capitol. Although much smaller than the Stevie Ray Vaughn and Philosophers’ Rock memorials, the rhetorical valence here is still the same: to “instruct” readers with regard to core city values, to reproduce and replicate the affect, ideology and metaphysics of the June 7th hearing[3] (and of every victory and defeat that came after), to invite inquiry and dialogue, to agitate and provoke, and to legitimate resistance. Like much postmodern architecture (Blair et al. 1991), much of the work in the central city, as we have reviewed in the course of this flânerie, is highly regional, contextualized, and agonistic.

Conclusion

And with these espressos and this shining Little City near the hill, this flânerie so concludes. These objects of our fear and desire, as I have outlined them here, are the visible marks of the intensities that course our fair city. These marks are indicative of affective norms which “speak” through a cultural form, and a signification of the community which produced them — whether verbally before the city council or by graffiti, poster paper, iron, or bronze. At this central city site as I have outlined it here, our rhetorical community “attempts to shape and possess the affective norms of the present and the future by first shaping and possessing the past” (Morris, cited in Blair et al. 1991: 283). In many different ways our rhetorical community, through these objects, lays claim to the city, tags it, hoists green colors, opposes itself as One against the Other, these barbarians at the gate.

A number of implications for theory and practice may be suggested by this study. One encouraging note is that citizens of a modern city — a city existing within a concrete historical ensemble of postmodernity and advanced consumer capitalism — can indeed orient and mobilize themselves as an effective community of resistance, take charge of their own affairs, and assert their influence over the key issues effecting their geography. We see citizens who actively and self-reflexively constitute their city and themselves as autonomous subjects, rather than as docile receptors constituted by powerful elites and dominant institutions.

A second implication follows from our citizens’ unique, phenomenological attachment to their city’s topography. This connection to place and space becomes a fierce animator and an ongoing discursive and psychic resource for the rhetorical community. I believe this case demonstrates the human desire for landscapes we can love and love by playing in them. Cultivating the variety of practices that brings people into relationship with their ecology may be a pivotal consideration in long-term community organizing. Citizens who feel that there is nothing noteworthy about their locale may discover that rivers can be made clean and swimmable, prairies wild and open, that an abandoned rail line can become a wooded ski trail, a wildlife habitat, a communal space — a place-ballet to choreograph as their own.

Third, the possession of the city, the struggle for the hearts and minds of its citizens is a pedagogical project, an ongoing act of social construction and cultural production as the movement creatively deploys a variety of texts and working materials. This attention to knowledge interests and expertise is crucial to effective claims-making in the public arena, undermines dominant socioeconomic myths, and — at this site through a variety of exhibits and installations — accomplishes a measure of what Giddens calls time-space distanciation, “the capacity to store the resources involving the retention and control of information, knowledge, and narratives whereby social relations are perpetuated across time-space” (1984: 261).

In closing, I would offer two observations which might come the closest to attaining the status of “theoretical contributions” for this study. First, in the tradition of discourse geography a majority of studies can be characterized as “resistant critiques”, those readings intended “to expose and possibly disrupt the generally constrictive and regressive politics of the discourse under examination”[4] (e.g., the work of Dorst, Norkunas, and Wilson noted in our introduction). By way of contrast — and by dint of accidental tourism — our Austin account offers a positive reading of a successfully resistant discourse. Opportunistically attending to sites such as this through deep ethnography may be one contribution qualitative researchers might make towards to a growing portfolio of petits récits and petites techniques from which a full-scale genealogy of resistance might someday be written.

Secondly, I would acknowledge the social science researchers who have called for the discovery and application of “new research methods” which might allow us to account for the “dynamic workings of collective affect” (Cooperrider and Pasmore 1991: 783) as a way to begin the march to sustainable futures. In the spirit of that call, this study has attempted to extend upon the text collecting and curatorship of Dorst’s postethnography by linking it to four interpretive tacks: to (1) Bormann’s concept of the envisioned and envisioning rhetorical community; to (2) interpretive interactionism’s focus on epiphany and transformation — particularly as we have been directed to our choice of site and situation (Denzin 1989); to (3) the importance Walter Benjamin and others placed on the practice of flânerie “for getting a ‘fix’ on the city and on the Other through a deep ethnography of attitudes and regimes of value” (Shields 1996: 229); and to (4) Tyler’s interest in an “ethical” postmodern ethnography where a “cooperatively evolved text consisting of fragments of discourse” might evoke “an emergent fantasy of a possible world” (1986: 125-126).

My goal, however, is not so much to take my readers back to ethnography’s surrealist origins (Clifford 1988: 117-151), as it is to discover a theoretically and methodologically rich intersection which might evoke for my readers the spirit, emotionality, and power of this community and speak to the epiphany that has moved it, across a decade, to manifest a possible world. A world in which citizens learn to talk back to their local multinational corporation, take back City Hall, and reclaim the commons.

Appendices

Note biographique

Curt Hirsh

Curt Hirsh est enseignant en communication à St Edward’s University, à Austin, Texas. Ses intérêts de recherche se portent vers l’application critique des études organisationnelles, ethnographiques et rhétoriques à des sites problématiques concernant la géographie humaine, les discours publics et les organisations communautaires.

Curt Hirsh is a communication studies instructor at St Edward’s University in Austin, Texas. His research interest is in the application of organizational studies and ethnographic, rhetorical, and critical critique to problematic sites of human geography, public discourse, and community organizing.

Notes

-

[1]

In addition to the author’s direct participation, data has been generated via human and non-human sources. Observations of, and interviews with, environmental leaders and rank-and-file members were used to ascertain themes and motifs regarding members’ motivations, their recollections regarding relevant events, and their perspectives on the nature and evolution of the movement. This record, as well as the live and videotaped records of citizen comments to the city council, were critiqued for their dramatistic structural elements and the technical categories of symbolic convergence theory and fantasy theme analysis (Bormann 1972, 1983). Non-human sources of data collection also included assorted documents and records, including but not limited to news articles, organizational newsletters, information flyers, political advertising of all forms, print and film media, music, plays, dance performances, statuary, architecture, photographs, maps, and graffiti.

-

[2]

This gesture — however “imagined” — towards vigilante “justice” may be somewhat problematic for readers more accustomed to celebrating the transcendent eco-feminist and radical democratic potentials of deep ecology than the masculinist impulses of gunslinger iconography. Appropriating such elements of preexisting, politically suspect discourse into the community mythos may be something of a regressive move, when a more progressive — perhaps less agitative one — may be called for. This urban alliance has managed to advance productively and non-violently, as many movements do, in spite of entrenched and unavoidable discourses. The caveat remains, however, that rhetorical visions which “emerge from the chaining of negative fantasy themes” may have few links to any “anchoring material reality” and hence be dangerous or life threatening to outsiders and insider-participants alike (Shields 2000: 415).

-

[3]

A content analysis of the language deployed that June 7 evening resonates with Pierre Bourdieu’s discussion of those unique and decisive moments in human history when communities break free from the “expressly censored unnamable” into “the universe of discourse”, and are transported by an “extraordinary discourse” (the Ausseralltaglichkeit), capable of “giving systematic expression to the gamut of extraordinary experiences” (Bourdieu 1984: 170). For the duration of the decade this discourse will be a considerable resource to this community in its capacity to puncture a consensus trance, access the sacred, resuscitate group memory and solidarity, and generate collective affect.

-

[4]

I wish to extend my appreciation to the anonymous reviewer who suggested this orientation between my manuscript and the tradition of discourse geography.

References

- Austin Parks and Recreation. 1998. Safari’ 98. (Brochure). Austin, Texas.

- Best, Steven and Douglas Kellner. 1991. Postmodern theory: Critical interrogations. New York: Guilford Press.

- Blair, Carole, Martha S. Jeppeson and Enrico Pucci Jr. 1991. Public memorializing in postmodernity: the Vietnam Veteran Memorial as prototype. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 77: 263-288.

- Bormann, Ernest G. 1972. Fantasy and rhetorical vision: The rhetorical criticism of social reality. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 58: 396-407.

- ______.1982. The symbolic convergence theory of communication: Applications and implications for teachers and consultants. Journal of Applied CommunicationResearch, 10: 50-61.

- ______. 1983. Symbolic convergence: Organizational communication and culture. In Communication and organizations: An interpretive approach, eds. Linda L. Putnam and Michael E. Pacanowsky. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, Theory of communication: 99-122.

- ______. 1985a. Symbolic convergence theory: A communication formulation. Journal of Communication, 35: 128-138.

- ______. 1985b. The force of fantasy: Restoring the American dream. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University.

- ______. 1994. Cragan, John F. and Donald C. Shields. In defense of symbolic convergence theory: A look at the theory and its criticisms after two decades. Communication Theory, 4: 259-294.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bryce, Robert. 1992. Barton Springs eternal. The Austin Chronicle 1992: 33.

- Clifford, James. 1988. The predicament of culture: Twentieth-century ethnography, literature, and art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Conquergood, Dwight. 1991. Rethinking ethnography: Towards a critical cultural politics. Communication Monographs, 58: 179-94.

- Cooperider, David L. and William A. Pasmore. 1991. The organizational dimensions of global change. Human Relations: 763-787.

- Denzin, Norman K. 1989. Interpretive interactionism. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Dorst, John Darwin. 1989. The written suburb: An ethnographic dilemma. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Eyerman, Ron and Andrew Jamison. 1991 Social movements: A cognitive approach. Oxford, UK: Polity Press.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Griswold, Charles L. (1986) The Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial and the Washington Mall: Philosophical thoughts on political iconography. Critical Inquiry, 12: 688-719.

- Habermas, Jurgen. 1972. Knowledge and human interests. London: Heinemann.

- ______. 1984. The theory of communictive action. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Mazlish, Bruce. 1994. The flâneur: From spectator to representation. In The flaneur, ed. Keith Terter. New York: Routledge Press.

- McLeese, Donald. 1999. A fresh take on SRV. Austin American-Statesman, March 23: E1-E2.

- Mills, C. Wright. 1959. The sociological imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Morris, Richard. 1990. The Vietnam veterans memorial and the myth of superiority. In Cultural legacies of Vietnam: Uses of the past in the present, eds. Richard Morris and Peter Ehrenhaus. Norwood, NJ, Ablex: 191-222.

- Norkunas, Martha K. 1993. The Politics of Public Memory: Tourism, History, and Ethnicity in Monterey, California. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Pile, Stephen. 1996. The body and the city: Psychoanalysis, space and subjectivity. New York: Routledge.

- Pipkin, Turk and Marshall Frech, eds. 1993. Barton Springs eternal: The soul of a city. Austin: Softshoe Publishing, Hill Country Foundation.

- Schwartz, Barry. 1982. The social context of commemoration: A study in collective memory. Social Forces, 61: 374-402.

- Seamon, David. 1980. Body subject, time-space routines, and place-ballets. In The human experience of space and place, eds. Anne Buttimer and David Seamon. London, Cross-Helm: 148-165.

- Shields, Rob. 1996. A guide to urban representation and what to do about it: Alternative traditions of urban theory. In Re-presenting the city, ed. Anthony D. King. New York, New York University Press: 227-252.

- Shields, Donald C. 2000. Symbolic convergence and special communication theories: Sensing and examining dis/enchantment with the theoretical robustness of critical autoethnography. Communication Monographs, 67 : 392-421.

- The Austin American Statesman. October 17, 1998. Splash is here. Section C1.

- Tyler, Stephen A. 1986. Post-modern ethnography: From document of the occult to occult document. In Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography, eds. James Clifford and Georges E. Marcus. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press: 122-140.

- Weick, Karl E. 1979. The social psychology of organizing (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Wilson, Bobby M. 1980. Social space and symbolic interaction. In The human experience of space and place, eds. Anne Buttimer and David Seamon. London, Cross-Helm: 148-165.

- Wilson, Chris. 1997. The Myth of Santa Fe: Creating a Modern Regional Tradition. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Wright, Lawrence. 1993. Heroes. In Barton Springs eternal: The soul of a city, eds. Turk Pipkin and Marshall Frech. Austin, TX, Softshoe Publishing/The Hill Country Foundation: 51.

List of figures

Figure 1

An aerial view of Barton Springs Pool and downtown Austin from the Barton Creek greenbelt

Figure 2

Barton Springs place-ballet

Figure 3

Philosophers’ Rock

“The polis, properly speaking, is not the city-state in its physical location: it is the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between people living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be” (Arendt 1958: 198).

Figure 4