Abstracts

Abstract

The paper examines the relationship between indigenous knowledge and heritage documentation efforts generated by scientists and other forms of local activities that work in strengthening indigenous cultural identity and tradition. As the studies in indigenous heritage and environmental knowledge have become one of the fastest-growing fields in northern cultural research, there is tough competition for limited resources and, even more, for the time, goodwill, and attention of northern constituencies. Scholarly projects in heritage and knowledge documentation represent just one stream within today's public efforts, though an important and visible one. Those projects do have an impact in local communities; but such impact is often subtle, circumstantial, and may not be sustainable when left standing on its own. Local knowledge, very much like active language, relies primarily on oral transmission, family ties, community events, and subsistence activities. As long as those prime channels of cultural continuity are working, “our words put to paper”—knowledge and heritage sourcebooks, school materials, and catalogs—should be regarded as long-term cultural assets that may play a crucial role in the transformed northern societies of today and of tomorrow.

Résumé

L’article étudie la relation entre les savoirs autochtones et les efforts de documentation du patrimoine générés par des scientifiques et d’autres formes d’activités locales qui travaillent à renforcer l’identité et la tradition culturelle autochtones. Alors que les études sur le patrimoine autochtone et les savoirs environnementaux sont parmi les champs de recherche en culture nordique les plus rapides à s’être développés, la compétition est rude pour des resources limitées et, plus encore, pour le temps, la bienvaillance et l’attention des circonscriptions du nord. Des projets scientifiques sur le patrimoine et la documentation des savoirs ne représentent qu’un courant parmi l’effort public actuel, mais il est important et visible. Ces projets ont bien un impact sur les communautés locales ; toutefois un tel impact est souvent subtil, indirect et n’est sans doute pas viable une fois abandonné à l’auto-gestion. Les savoir locaux, tout comme les langues vivantes, reposent principalement sur la transmission orale, les liens familiaux, les évènements communautaires et les activités de subsistance. Aussi longtemps que ces canaux principaux de continuité culturelle fonctionnent, «nos mots transcrits sur papier» — les livres sources des savoirs et du patrimoine, les documents scholaires, et les catalogues — doivent être considérés comme des avoirs culturels à long terme qui jouent et joueront peut-être un rôle essentiel dans les sociétés nordiques transformées d’aujourd’hui et de demain.

Article body

Introduction

This paper examines the impact—anticipated, declared, and real—of some recent efforts in the documentation of traditional knowledge and cultural heritage in the Bering Strait region. Today, the study of indigenous knowledge is one of the fastest-growing fields in northern cultural research. It generates scores of projects every year, both scholarly and locally initiated. Those efforts commonly deliver tangible products, such as books, catalogs, CD-ROMs, documentary films, and teaching aids.

In today’s village life, knowledge on local environment, subsistence practices, former spiritual rules, and community history is regarded as a crucial pillar of Native culture. Local communities and the growing ranks of researchers praise the value of indigenous knowledge; many agencies and institutions now actively promote its documentation. These days, northern communities increasingly turn to partnership with scientists in the collection and sharing of records about indigenous knowledge. Several recent examples of successful collaboration have already generated substantial enthusiasm in the communities and among heritage scholars alike; they have helped open valuable historical resources and museum materials to local audiences. From their side, northern residents are becoming more attentive to their legacy as it is preserved in “written knowledge,” that is, in texts, historical photographs, catalogs of early ethnographic collections, and other scholarly formats.

The impact of this recent enthusiasm about Native knowledge documentation should, nevertheless, neither be taken for granted nor overestimated. Anthropologists and linguists commonly praise the special value of their written products, like texts and dictionaries, in support of Native cultures, or, as we call it, following the terminology of Joshua Fishman (1991), in “reversing language and knowledge shift” (RLKS or RKS, for the knowledge only). But rarely do we risk testing how our printed products score against other forms of knowledge preservation that function routinely in situ, within the community, or develop independently of our efforts.

Indeed, it is hard to evaluate the impact of a printed heritage volume, a museum catalog, or a dictionary of Native language against, let’s say, a village dance festival or an elders’ town meeting. Nor do we have adequate tools to compare our books on culture with a community whale hunt, a trip to a fishing camp, a Native craft workshop, or a quiet family evening, with traditional meals and parents’ storytelling. Each activity plays its own role. Each format—oral, written, interactive, or expressive—works in strengthening one’s cultural identity and one’s attachment to local tradition. In fact, they all act in “reversing knowledge shift.” They also function in the complex milieu of today’s community life that subjects every person and the community, as a whole, to the many “shift” factors from the world at large, like new technologies, modern schooling, mass media, easy travelling, new norms, and many more.

Under these stressful conditions of ongoing culture change, the similarities between the efforts that support indigenous languages and the documentation of traditional knowledge are obvious. They literally invite us to search for parallels and to compare successes, as well as failures in our respective fields. This profound unity (“community”) of our disciplines is something I personally learned from years of interaction with Michael Krauss. I believe we have much to learn from each other’s fields. It is no coincidence that this paper addresses the issue of knowledge/heritage preservation in the North under a distinctively socio-linguistic paradigm of “reversing language shift.”

This paper examines three major issues. First: What is the current status of that which is commonly called “traditional Native knowledge,” or, rather, what kind of transition is it going through in several Bering Strait communities that have been the subjects of recent studies? Second: What is different in Native knowledge and language change (“shifts”) and what lessons from earlier language preservation efforts may be applicable to the current knowledge documentation field? The third issue is the very question mark that has been placed on the title of the symposium, “Reversing Knowledge and Language Shift in the North?” Are we doing enough or, at least, something to reverse this shift? If so, how do our scientific products interact with other current factors and venues that act in support of traditional knowledge, as outlined above?

In answering these questions, I will cite illustrations and refer to lessons learned from several heritage and knowledge documentation projects I have been a part of during the last decade. Those studies have been undertaken on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, the Alaskan mainland, and in the nearby Chukchi Peninsula, Russia. They have covered many fields of traditional cultural legacy, including expertise on sea ice and weather, walrus biology and subsistence hunting, historical photography, oral tradition, genealogical stories, but first and foremost, recent change in the volume and status of knowledge preserved in today’s Native communities (see Freeman et al. 1998; Krupnik et al. 2002; Krupnik 2000a, 2001, 2002, 2004; Krupnik and Mikhailova in press; Krupnik and Oovi in press; Krupnik and Vakhtin 1997, 2002; Metcalf 2004; Oozeva et al. 2004; Walunga et al. 2004). Most of the knowledge and heritage documentation efforts cited in this paper resulted in substantial outreach activities; they also produced valuable cultural materials that have been widely disseminated in local communities. Native elders, knowledge experts, and many younger people played critical roles in those projects as researchers, writers, volume co-editors, translators, or collaborators. The projects generated several published reports, which describe each specific effort in detail.

I also rely here upon both published and personal accounts of many of my colleagues in the knowledge/heritage documentation field, as our shared experiences become parts of a common lore (e.g., Aporta, this volume; Burch 1981, 1998; Crowell 2004; Crowell et al. 2001; Ellana and Sherrod 2004; Fair 2004; Fienup-Riordan 1998, 2005; Fox 2002; Gearheard, this volume; Huntington et al. 1999; Huntington and Fox 2005; Jolles 2002, 2003; Krupnik and Jolly 2002; Schaaf 1996; Thorpe et al. 2001, etc.).

Evolution of knowledge: Can I guess the weather as my father used to?

The question put here is, of course, an imaginary one. Of course, I learned some valuable tips from my father about winds, stars, and clouds; but I neither followed him as a child on his daily weather watch nor received any portion of that knowledge as our “family tradition.” As far as I know, he did not get much of his “weather knowledge” from his father either. We both learned the bulk of what we know about the environment primarily from books, or on personal travels. Ours is a type of culture in which every valuable skill is acquired through formal learning and one that has had no generational continuity in occupation and residency for the last 100 years.

I would probably have to go several generations deep into my family genealogy to find an ancestor who indeed possessed such “local knowledge,” that is, one that blended practical experience and spiritual beliefs, used dozens of specific terms for certain local phenomena, and one that has been handed down via elders’ teaching, verbal transmission, and careful observation. However, my family's weather knowledge (or, rather, lack of it) is a legitimate illustration of the ongoing global process of knowledge change. As the topic of traditional or indigenous knowledge is gaining prominence in scholarly research, millions of people at the focus of our studies are following a common transition. Much like my family, they are trading that which was once called “traditional intellectual culture” for modern mixed knowledge acquired primarily via formal schooling, literacy in state-supported languages, and mass communication.

This situation is strikingly similar to the one known all too well by linguists who work in support and documentation of what is called “endangered languages.” Likewise, there is an obvious trend of conceptualizing studies in indigenous knowledge under the paradigm of “salvage anthropology,” that is, of capturing the phenomenon while it remains mostly untouched by culture change. The task is scientifically sound; but it ignores the simple fact that in all societies environmental and historical knowledge is open to many agents of change (and always has been!), namely, to the often rapid shifts in the content and structure of the information that has to be learned, transmitted, and preserved.

As several recent projects in the indigenous knowledge documentation illustrate, in the Bering Strait region and elsewhere, many northern communities still enjoy an outstanding pool of expertise on many aspects of their environment, cultural tradition, and local history (e.g., Ellana and Sherrod 2004; Fair 2004; Fienup-Riordan 2003; Jolles 2003; Metcalf 2004; Oozeva et al. 2004; Walunga et al. 2004). They are blessed with many highly experienced people who excel in watching and predicting weather, animal migrations, and game behaviour. They can name dozens of terms for various types of sea ice and winds; they can easily operate within traditional classifications that identify numerous forms of walruses or caribou/reindeer, based upon age-sex classes, skin colour, or shape of tusks or antlers. Those elderly experts usually learned such knowledge directly from their fathers, uncles, or other senior male relatives, who were, like them, walrus hunters or reindeer herders. Similarly, women learned their supreme skills and elaborate stories by following and listening to their senior female relatives. Grandparents and great-grandparents all did the same; so, many people still carry a unique and lineally transmitted body of knowledge based on established contents, rules, and patterns of sharing.

These people, however, are not—and have never been—immune to the many agents of culture change that act both within and beyond their communities. These days, the expert knowledge and intellectual legacy of the ancestors is not bestowed automatically upon everyone who is Native, or who lives in the village, or who is even a practicing hunter (Krupnik 2002: 183). First, people have to speak the same language as their forefathers—just to learn the many Native terms for various types of ice and weather, and to be able to use them. Second, they have to keep going onto the sea ice, or into the bush, in order to gain the visual experience of the realities codified in language terms, elders’ stories, and cultural tradition. And third, they have to undergo, at least, partly, a similar educational process, under which they learn to pay attention to certain phenomena under specific behavioural context(s). Those conditions can hardly be met in most of today’s northern communities where children normally are at school until the age of 16. Formerly, they used to follow their fathers to the sea at the age of eight and onto the ice at the age of 10 or 12. Today, they hunt with their fathers on weekends or during school vacations and they rarely go onto the moving ice. When they become adults, many often move to towns and become weekend or part-time hunters.

Many other agents of change are inducing this knowledge shift. Some come with technological modernizations that introduce more efficient weapons and hundreds of other practical innovations. As the high-speed snowmobiles and motorboats replace slower-moving dog-teams and skin boats, a whole layer of generational knowledge in mastering traditional equipment, safety rules, weather forecasting, and navigation, becomes endangered or obsolete. Much larger and broader landscape or seascape comes into use; but the old terms and names are fading away. As one young Siberian Yupik hunter articulated, “Why should we care about those shore currents—with our speedy boats we jump over them anyway.”

Technological modernization also means that knowledge is being lost, because fewer people can afford to be hunters these days. Less traditional technology around and fewer people knowing how to use it means that there is more reliance on expensive new equipment and on its even more pricey maintenance (such as gas, oil, spare parts, engines, snowmobiles, powerful ammunition, etc.). The ever-growing reliance on costly modern technology literally grounds those unable to afford it; it also limits their experience primarily in the routines of village or town life[1]. When fewer people go onto the ice or into the bush every day, there are fewer daily stories to share and a shrinking pool of good storytellers to say nothing about curious listeners. This is another subtle way the technological modernization plays into the loss of environmental knowledge, as local events and politics gradually become the key subjects of people’s attention in today’s Native village context.

Another factor may be called the “greening” of local knowledge. In the old days, hunters’ success and the availability of game animals was always viewed as an outcome of proper human behavior, of abiding to established guidelines, spiritual rites, ritual injunctions, and beliefs. Hunters of today, even the elders, speak increasingly in terms of stock “health,” pollution, and climate change (Krupnik 2002: 183). They like to say that their forefathers used to be “good ecologists;” that “the Eskimos were always in synch with their ecosystem,” and that they “were neat in preserving their environment.” Weather is now bad because of “global warming,” or because of some “radiation coming from out of space.” Again, this is a global process, as schooling, modern media, and game management regimes advance the “green” component of local knowledge, to the demise of traditional paradigms.

Another aspect of the knowledge change—very much like in the language documentation—is the gradually shifting ratio between the data preserved in scholarly records versus that maintained by the users on the ground. When I started my fieldwork in the Bering Strait region some 30 years ago, there were dozens of elders very knowledgeable about the events that took place in the early 1900s and even in the late 1800s. Those elderly experts were then filled with more stories about “old” life in their communities than could ever have been put to paper in one’s lifetime (Krupnik 2001). Over the three following decades, almost all of those elders passed away; and the people who were young in the 1970s are now considered experts in local tradition. Their body of knowledge is very different, because of the time that passed, language change, and other agents of shift. In the meantime, our records of the traditional culture keep growing. We may rely upon old taped interviews and hundreds of transcribed stories. We also have genealogical charts, field notes of earlier ethnographers, lexicons of old subsistence terms, historical photographs, and documentary records. These are invaluable sources of Native heritage that have been preserved because of written documentation, but the relevant oral knowledge is fading in local memory and use.

Native people keep saying that “when a knowledgeable old person dies a whole library disappears.” In fact, we, anthropologists, have also built massive libraries of knowledge on Native societies—very much like linguists did on Native languages. This knowledge once generously shared with us, has to be shared once again, this time with the communities we worked with. This is a new ethical aspect to our work, which I elsewhere called “knowledge repatriation” (Krupnik 2000b: 10). Very much like the work of linguists in promoting literacy and education in Native languages, knowledge documentation and knowledge repatriation may eventually transform the way people judge our mission and appreciate the value of our field.

Knowledge versus language: What can we learn from each other?

Being the products of human mind, of community intellectual life, and of people’s interactions, language and knowledge have much in common. This is especially true in the ways they are both learned and transmitted, as well as how they become endangered through the process of culture change. Storytelling and listening, watching and following one’s family members or village elders, peer communication—in short, the many settings of family and community life—are key venues in both language and knowledge continuity in every society. They still play a critical role in towns and villages across the North, despite several recent agents of culture shift.

Those parallels notwithstanding, scholars engaged in the documentation of Native languages and knowledge did surprisingly little about comparing their experiences. Since the time of Boas, Rasmussen, and Bogoras (who were all engaged in both culture and language documentation), northern anthropology has been instrumental in putting substantial blocks of indigenous knowledge onto paper. Volumes of basic ethnographies have been produced for many northern groups, often lavishly illustrated and supported by massive museum collections. Those classical ethnographies established our baseline documentation of the past knowledge, particularly in the fields of material culture, folklore, and spiritual beliefs.

Since the 1960s, the linguists made remarkable progress in the documentation of indigenous northern languages. They have published comprehensive dictionaries, grammars, and collections of texts, and they developed educational and community approaches to support language preservation through new venues of formal teaching and literacy, including textbooks, readers, educational guides, and curricula. Michael Krauss was particularly instrumental in these efforts both through his personal contributions and as an avid reviewer of other people’s work (Krauss 1973a, 1973b, 1980). Advances in the northern language preservation took place 15 to 20 years before most anthropologists began to contemplate similar efforts in indigenous “knowledge preservation.” Northern linguists also accumulated great experience in various forms of language maintenance, as they witnessed the decline of minority languages, in spite of so many good intentions and costly attempts.

One may argue that today’s anthropologists working with northern communities on the documentation of Native knowledge face the same challenges and fight almost the same battles as the linguists fought (and, mostly, lost) in the 1970s and 1980s. The reverse is also true: current community projects in the documentation and preservation of indigenous knowledge, particularly, of subsistence and environmental knowledge, may offer a boost to Native language preservation. They target the same constituencies, appeal to the same cultural values, and often use the same practices and even the same experts. The studies of Native place-names, traditional navigation and forecasting techniques, or the most recent efforts in the documentation of indigenous environmental observations in Native languages (see Oozeva et al. 2004) are good examples of those fields where language and knowledge can hardly be separated.

To begin, however, we have to identify, what is different in the processes of language and knowledge preservation, and why it is so. From an anthropologist’s perspective, those differences stem primarily from the ways language and knowledge functioned in traditional communities. First, prior to the onset of Native language education in governmental schools, no traditional community mechanism existed to teach the language other than through learning it in the family or daily setting. As such, there was no acknowledged process of language transmission, no special rules, designated actors, and no recognized grades in language acquisition. To the contrary, the process of environmental knowledge learning (and teaching!) was carefully structured, and supervised (see Bodenhorn 1997; Krupnik and Vakhtin 1997). Whereas basic subsistence and practical skills were normally acquired by simply watching and following one’s family members, direct teaching and information exchange were critical after certain age. Senior relatives, neighbours, and village elders, male or female for boys and girls respectively, usually acted as “teachers.” This is still the most common practice in many northern communities, with various groups of adults taking the lead at a certain stage in the youth learning process. The point here is that Native language education is a relatively new phenomenon, whereas the teaching and sharing of environmental knowledge has deep roots in Native culture.

Second, in traditional society, mastery of knowledge was far more particularized and socially controlled than mastership of language. Differences in family, neighbourhood, or kin group speech within one community were usually symbolic markers or products of recent mixture; they hardly impeded general communication. To the contrary, every kin group, every family had its pockets of restricted (non-shared) knowledge. There were also barriers in knowledge sharing between men and women, juniors and adults, shamans and the non-initiated. Knowledge was transmitted in culturally meaningful “packages,” and boundaries were enforced by tradition, taboos, and by the division of labor. As such, there were literally blocks of men’s knowledge versus women’s knowledge; those of coastal hunters versus inland herders; people from the northern side of the village versus people from the southern side; and, on top of that, of one’s home community versus everybody else.

Third, in traditional society knowledge, unlike language, was always personalized and sanctioned by the authority of its bearer(s), such as senior family relatives or village elders. Knowledge, unlike language, had always a prized value: it was a path to prestige, success, and community respect. It was something that people cherished and competed for. In short, if language was a given, knowledge was a pricey must. Those who had outstanding knowledge were also highly rewarded, as people praised experienced elders, obeyed the powerful shamans, and offered their daughters to skilled and knowledgeable hunters as second, and even third, wives.

These features and others associated with traditional knowledge may be regarded as great assets to today’s programs in the knowledge documentation and preservation. For example, today, people fully accept that cultural knowledge has to be “learned” through a certain established process—much like in the old days—and that it requires one’s active commitment as well as experienced “teachers” (Bodenhorn 1997: 123-124). It also creates a far more respectful attitude towards various knowledge “teaching aides,” such as tapes, printed sourcebooks, and reading materials. These days, such knowledge teaching aids are often nicely printed and illustrated by Native drawings, historical photos, and images of old objects (see Borlase 1993; Lee 1999). Unlike Native language educational materials, traditional knowledge can also be disseminated and actively promoted via texts and books published in other languages or with a limited component of the original language (e.g., Arnestad Foote 1991; Burch 1981; Crowell et al. 2001; Ellana and Sherrod 2004; Hallendy 2001; Kassam et al. 2000; Krupnik 2001; MacDonald 1998; McDonald et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 2001).

The particularized nature of traditional knowledge, versus Native language, offers another advantage to knowledge documentation efforts. For example, a linguistic booklet on Native nouns or suffixes could make an impact on an individual’s language fluency; but it usually engages a rather limited audience of Native language teachers and enthusiasts. To the contrary, an illustrated guide on how to make a traditional hunting skin boat (Ainana et al. 2003; Bogoslovskii 2004), or a catalog of old women’s tattoo patterns (Krutak 2003), caribou skin parkas (Burnham 1992; Vukvukai 2004), skin boots (Kobayashi Issenman 1997), or traditional dolls (Lee 1999) can easily stand on its own as a publicly valuable knowledge resource and as an agent in RKS. To experienced users, it offers new designs and expands existing skills. To those who have little knowledge, it brings inspiration and may encourage them to make a first try. Appealing heritage materials may trigger new interest in certain traditional activities that were considered lost for generations. Revival of grass basketry, dance mask-making, or of wooden canoe-building in many Native Alaskan communities are a few examples of knowledge and skills reestablished because of the availability of those new illustrated teaching aides. Of course, the other crucial factor was the input of a few experienced practitioners eager to share their knowledge with untrained enthusiasts.

The personalized nature of traditional expertise also corresponds to today’s practices of knowledge documentation and book publishing, which tend to elevate personal authorship. These days, experienced elders and knowledge experts are often referred to as “our books,” or even “readers of our tradition” (taquaqtit), which makes the association between traditional oral knowledge and its new written formats even closer (Bodenhorn 1997: 123–24). Individual authors” names, when placed on book covers, often add a particular stamp of authority and strengthen the value of traditional knowledge put on paper. For example, Paul Tiulana’s life-story (Senungetuk and Tiulana 1987), Conrad Oozeva’s sea ice dictionary (Oozeva et al. 2004), Sheme Pete’s list of Alaska place-names (Kari and Fall 2003 [1987]), Simon Paneak’s stories and personal drawings (Campbell 1998), or Paul Johns’ oratories (Fienup-Riordan 2003) enjoy special value in Native communities, first and foremost because of the recognized authority of those outstanding experts.

Last but not least, maintaining one’s native language and, even more, becoming fluent in it (that is, an individual RLS effort) brings public respect and deep personal satisfaction, but has no tangible value. Mastering certain types of traditional knowledge (RKS) offers similar rewards, but it also brings tangible practical benefits, such as better access to certain subsistence resources, like edible plants or traditional materials for arts and crafts. In today’s public environment in Alaska and Chukotka, it also opens prized public venues, like regional and state-wide dancing performances, craft shows, elders’ meetings, heritage and museum events, to name but a few. These are a great bonus to knowledge revitalization efforts, which earlier language programs rarely, if ever, received.

Written versus “natural”: How do we score?

On one winter day, I was sitting in the lobby of a village guesthouse in Gambell, Alaska and was glancing over the many posters pinned to the walls. In the absence of other designated entry space in this isolated northern town of some 700 people, the guesthouse (or a “lounge” as it is called) offers a good public display of how the community addresses its members, but also how it presents itself to visitors from the greater world.

Altogether, I counted over a dozen glossy posters on the walls, some featuring familiar people or images. I recognized, for example, the face of Iñupiat educator James Nageak featured above the slogan “I Eat Well – Like My Ancestors Did!” “Eat Traditional Food!” argued a message on another poster written in large font, with a huge exclamation mark. There was also a big archaeological poster decorated with old ivory harpoon heads, titled “Sivuqaq Archaeology,” and prepared, as stated, “upon the materials from the Smithsonian Institution.” Next was a large 2004 wall calendar titled “Naruyakaa Akutaq,” with a picture of Yup’ik children from Tuksook Bay. Three almost identical posters carried the same title, “Eskimo Cultural Values, as narrated by Paul Tiulana” (the latter an esteemed King Island elder). They displayed a type of 12 Eskimo ethical commandments, written both in English and in one of the three Alaska Yupik languages: Siberian Yupik, Yauyuk (Central Alaskan Yup’ik), and Southern Yupik. Each poster featured a Native elder’s face; all were well-known and familiar figures.

I was literally stunned by this village wall propaganda and, even more so, by its clear concentration on Native tradition, language, and heritage. On that trip, I was doing an assessment of the impact of our earlier heritage sourcebook, Akuzilleput Igaqullghet (Krupnik et al. 2002). I had seen our books on kitchen tables and on the floor in family houses. Copies of historical photographs from the Smithsonian collections reproduced in the volume had become fixtures in many village apartments. Stories were told about the sourcebook being sent as gift to relatives off the island, to students at distant schools, to family members in the hospitals and even in jail, to boost their spirit and ethnic pride. “I am proud to be a Yupik now”—one student, reportedly, said upon receiving a book that was shipped to his college dorm in California from the island.

As rewarding as those stories might be, the impact of that and other efforts in the documentation of indigenous knowledge should be put into the broader context of today’s community life. Like the many posters on the walls of the village guesthouse, we compete not only for resources in knowledge documentation work, but also for the time, goodwill, and attention of Native constituencies. Many Native institutions, individual Native artists, writers, and historians are now increasingly active in initiating their own efforts in knowledge documentation and preservation. They often have greater support from their communities, as well as from Native and non-Native sources.

In their attempts to document cultural heritage, in “reversing knowledge shift,” Native activists usually focus on certain steps that anthropologists are not aware of or do not treat seriously. Incidentally, these are often the very same steps that Fishman (1991: 88-108) advocated with regard to “reversing language shift” for endangered minority languages. Though Fishman’s book was hardly ever heard of in rural Alaska, some local RKS efforts are very close to his recommendations; in fact, they may be seen as intuitive overlaps.

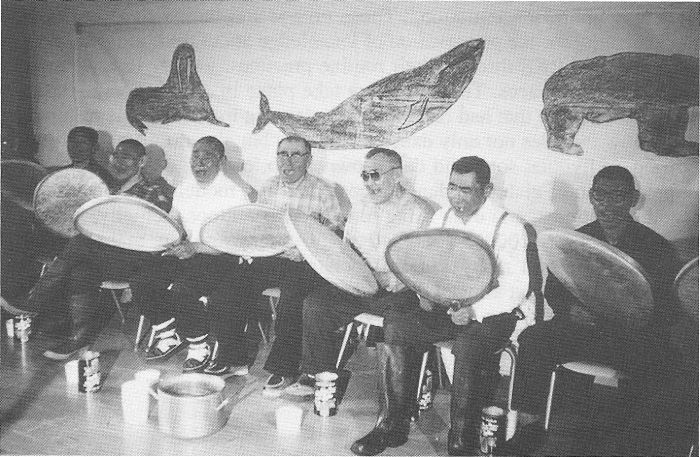

Nowhere is that more obvious than in the field of Native dances, or dancing culture, which remains the most successful example of the RKS (“reversing knowledge shift”) achievements in both Alaska and Russian Chukotka. Naturally, traditional dancing is the domain of elderly experts, who preserve the expertise on the music, songs, and dancing arrangements as well as on associated cultural knowledge. By the 1960s, in many Bering Strait communities, public performances of traditional dances were undertaken primarily by elders and often by elders alone (Figure 1). In some places, traditional dances have died out completely, because of the local missionaries’ ban on non-Christian performances (seen as “backward” or “pagan”). Hence, the first success in RKS was achieved when Native dance ceased to be associated with “elders only” and when mixed-age and, particularly, family-dance units mushroomed (Figure 2). In this way, the dancing “oralcy” (Fishman 1991: 92) received what Fishman (ibid.) calls “a demographic concentration.” Those village and family dance groups became the main vehicle(s) for the preservation of knowledge about traditional dancing culture and to the eventual RKS through their routine practices, weekly local rehearsals, and larger public performances. The latter now take place in almost every Alaska Native community, even those that had once lost their dancing tradition. This restored cultural knowledge now includes not only dance techniques but also drum-making, music- and song-writing, individual song and dance-ownership, exchange of personal songs and dances, production of elaborate dancing costumes that model traditional clothing and ornamentation patterns, and even using female dance tattoos (actually, make-up, Lars Krutak, pers. comm. 2003). Some 40 to 50 years ago, in many Bering Strait communities, these and many other associated cultural practices were considered doomed to extinction, lost altogether, or remembered by very few. The preservation, a clear case of the RKS, has been achieved by the Native practitioners themselves, without any intervention from outside cultural agencies, professional musicians, or anthropologists[2].

Figure 1

Gambell village Yupik dance performance, ca 1964.

Figure 2

Savoonga village dance team performs at the Elders-Youth annual conference in Nome, February 2004.

The team includes dancers and singers from four generations; its eldest member, Jimmie Toolie, passed away in 2003 at the age of 98. Photo by G. Carleton Ray.

Native dance culture now exceeds the community (village) level and transcends many other domains of public life. Inter-village, regional, all-Alaskan, and even international indigenous dancing festivals are now regular events that attract hundreds of enthusiastic participants and spectators. Native dance performances are increasingly featured as a key bi-cultural component at every public meeting focused on Northern issues in Alaska and elsewhere, including many run in English or in Russian only. Last but not least, Native dance has now strong educational support via classes in Native dances offered at many Alaskan schools, colleges, and at several campuses of the University of Alaska. In this way, knowledge about Native dance extends to a larger audience and generates a bi-cultural (in Fishman’s terms, “majority bi-lingual”) constituency. In fact, there are many non-Natives or highly assimilated Alaskan Natives who are active practitioners of indigenous dance. The most powerful illustration of the accomplished RKS in the field of Native dance was a procession of many thousand Native American marchers and dancers on the U.S. National Mall in Washington, D.C., on September 21, 2004, the day of the opening of the new Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. For over three hours, Native American dance culture proudly assured its vibrancy and presence in the very symbolic public space of the U.S. Capital. Using Fishman’s own words, this is a true “success story” of a minority expressive language that has established a viable niche, along the powerful majority culture[3].

One can cite several recent RKS achievements when components of Native Alaskan knowledge and heritage—much like Native dance—endured and expanded, despite the overall culture and language shift. Today’s vigorous status of Alaskan subsistence whaling under the regulation of the Alaskan Eskimo Whaling Commission is a good example. At present there are many more Native Alaskan whalers, hunting crews, and whaling communities than there were at any time during the 20th century (Braund and Moorehead 1995)[4]; associated hunting knowledge, spiritual beliefs, and community rites are duly preserved (Anungazuk 2003; Jolles 2003; Larson 2003). Restoration of Native masks, mask-making, and masked dances—after almost 70 years of extinction—is another Alaskan RKS achievement (Fienup-Riordan 1996: 148-150). Knowledge about Native place-names, life-stories, and local village histories is also increasing its public status and its share of public attention, including in the book and media markets—even though the actual pool of knowledge may be shrinking. In these and many similar RKS efforts, local experts and communities are often doing the main groundwork. Many recent projects in knowledge documentation (even when accomplished by or with the assistance of professional anthropologists) have been initiated by Native agencies, such as the Alaska Native Science Commission, Alaska Native Knowledge Network, Alaska Eskimo Whaling and Walrus Commissions, and others[5]. The situation is, of course, much more advanced in Nunavut and Greenland, where local agencies run by the Inuit themselves are primarily in charge of knowledge documentation and preservation efforts (see papers by Aporta, Csonka and Gearheard, this volume).

Conclusion

Of the many messages a cultural anthropologist can borrow from Fishman’s advocacy on behalf of “reversing language shift,” two seem particularly relevant to the field of knowledge preservation. First, today’s anthropologists are usually more focused on the study of change. This naturally leads them into the field of cultural and knowledge transitions under the pressure of modernization. We are also deeply influenced by our field’s legacy of “salvage anthropology” and by the rhetoric of endangered minority languages and cultures. As a result, we usually know much more about indigenous cultural losses than of endurance and cultural revival. Hence, a few documented stories of successful RKS cases in the North have to be specially advocated, for the sake of the Native and scholarly audiences alike. Second, as Fishman (1991: 12) argues , it is always possible to do something for an endangered minority language (or culture); the key task is to decide what can be done in a particular context and, usually, with limited resources.

As this paper illustrates, Native communities in the Bering Strait region and elsewhere across the Arctic have witnessed a new era in the documentation and promotion of their traditional knowledge. That growing interest in indigenous knowledge has arrived to the North almost two decades later than to the more southerly areas, like tropical forest or arid regions (see Berkes 1999: 17-26); but it materialized here with full force and a big public splash. These days, almost every Native Alaskan meeting, website, or public venture refers, one way or another, to traditional, or indigenous knowledge. It is accompanied by a huge surge of interest in what is commonly known as TEK (“traditional ecological knowledge”) among local audiences, research and public institutions. Resources are now flowing in from various directions; so, the question is, of course, how to put them to better use?

Recently, this new enthusiasm for local environmental knowledge preserved in Native communities across the North has been championed by two very energetic constituencies, first by environmentalists and, later, by scientists engaged in the study of global climate change (see Berkes 1999; Helander and Mustonen 2004; Krupnik and Jolly 2002). Numerous environmental science programs in Alaska today (and even more so in Canada) feature Native knowledge as a source of valuable data. Many international climate change initiatives now welcome contributions from Native experts, and agencies are eager to contribute resources to support Native observations and traditional knowledge documentation projects (e.g., Hassol 2004; Huntington and Fox 2005). Scientific and public interest in Native knowledge has also attracted unprecedented media attention. Recently, major newspapers, science and popular magazines ran front-page stories about the rapidly changing Arctic environment. Almost every one of them referred to the ecological expertise of northern residents or quoted their observations[6]. Under this new spotlight, knowledge documentation projects initiated by professional scientists constitute but one stream within a flow of public efforts, though an important one. We often produce the most refined and better-known products, but we rarely acknowledge the limitations of our niche and how we score against other efforts in the field.

My hope is that, overall, we may at present have slightly better chances with the preservation of indigenous knowledge (if not to the RKS, in general) than the linguists had in the field of Native language preservation some 20 or 30 years ago. We began several decades later and thus can benefit from the experience of earlier RLS efforts, as well as from the institutional framework created during the years of Native education programs. Both Native communities and institutions are better organized now than in the 1960s; they are also taking on most of the groundwork in the preservation and documentation efforts in many fields (like dancing, subsistence whaling, Native arts and crafts). Still, much like the case of northern languages, there are many spheres of traditional knowledge that are shrinking or, rather, are being supported by an ever-diminishing group of elderly experts.

A great advantage to knowledge preservation and the prospective RKS efforts is that they may be implemented in limited, though meaningful “blocks” and, still, can be quite successful. This is in sharp contrast to language preservation programs that should come in certain totality, like by several years or grades in language education, to ensure a lasting impact. To many of those knowledge “blocks,” however—as in the case of Native dance or whaling—scholarly programs in knowledge documentation play but a secondary role. Though more vital to other fields, such as genealogical memory, arts and crafts, or community history, it is hardly critical, as long as the tradition is viable and local experts may be easily consulted. In fact, when anthropologists’ notes and other written records become the key source of information for Native audience, it is a clear indicator of knowledge endangerment. This is, again, very much identical to the many RLS efforts on behalf of endangered minority languages, which, though, blessed with a shelf-full of dictionaries and grammars, enjoy few active speakers.

Scholarly projects in knowledge documentation do have an impact in local communities. That impact, however, is more often than not circumstantial, subtle, and, perhaps, unsustainable if left to stand on its own. Local knowledge, like active language, relies primarily on oral transmission, family ties, community events, and subsistence activities. As long as those prime channels of cultural continuity are working, “our words put to paper”—published books, school materials, and museum catalogs—will play only a secondary role. Our knowledge documentation projects and their products do find a receptive readership among certain types of local audience, such as literate elders, students, heritage enthusiasts, schoolteachers, and cultural workers, to which those heritage publications are, in fact, addressed. Much like texts in Native languages, texts and sourcebooks in Native knowledge are vital to supporting such a constituency of trained readers in northern villages, who are typically the most active users and promoters of indigenous heritage anyway. This literally blurs the dichotomy between the exsitu (or etic, that is, the one coming from the outside) versus the insitu (or emic, the one being done from the inside) knowledge-preservation approaches (see Agrawal 1995a: 429-432, 1995b: 6-7).

In other contexts, as for example among urban Native residents or in the Russian indigenous communities in Chukotka, heritage publications, old photographs, and sourcebooks already act as critical vehicles of ethnic knowledge. Most of those constituencies are, however, in the final stages of the “knowledge shift” process and are unlikely to reverse it on their own

To conclude, scholarly and heritage publications, “our words put to paper” can hardly be expected to produce a sustainable RKS effort. Rather, they should be regarded as long-term cultural assets that may play a vital role in the transformed, that is, more literate, school- and information-oriented Native society of today and tomorrow. This is something anthropologists can do as welcomed partners, when the communities are eager to take responsibility for the documentation and preservation of their ancestors’ knowledge. By that time we hope there will be shelves of heritage books, catalogs, and story collections for every northern community (Figure 3), to which Native audience may turn. Anthropologists cannot reverse knowledge shift, but the community may. If so, anthropologists will be there to assist.

Figure 3

Printed materials used for the Yupik Language and Heritage classes at the Gambell high-school, 2004.

It is a peculiar mix of various publications, including old Russian Yupik textbooks in Cyrillic, recent folklore collections, scientific publications, and homemade teaching aides. Photo courtesy Christopher Koonooka.

Appendices

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to many colleagues in the field of the documentation of traditional knowledge, particularly, to Fikret Berkes, Lyudmila Bogoslovskaya, Ernest S. Burch, Jr., Mikhail Chlenov, Ann Fienup-Riordan, Louis-Jacques Dorais, Shari gearheard, henry huntington, vera metcalf, and nikolai vakhtin, for their insight, collaboration, and critical feedback over the years. Special thanks go to michael krauss, with whom i shared many illuminating discussions on the relationship between language and knowledge preservation efforts. g.carleton ray and christopher koonooka kindly offered their photographs as illustrations. cara seitchek and shari Gearheard, as well as two anonymous reviewers made many valuable comments to the earlier drafts of this paper that are highly appreciated. Native elders and knowledge experts—lyudmila ainana, christopher koonooka, chester noongwook, george noongwook, conrad oozeva, willis walunga—partners in many documentation efforts listed in this paper, deserve special thanks.

Notes

-

[1]

I am grateful to Shari Gearheard for this insightful comment.

-

[2]

My rather cursory knowledge of Native dance revival on the Alaskan side has been boosted by a far more detailed analysis of the Iñupiaq dance culture in Barrow in the recent M.A. thesis by Ikuta (2004). The situation is quite different in Chukotka Native communities on the Russian side. There, Native dance culture was heavily influenced by professional Russian musical workers. Native dance teams and festivals were (and still are) supported by the state-run cultural agencies as a part of the governmental cultural policy.

-

[3]

In February 2004, I watched another illustration of an accomplished RKS in Native dance culture at the Elders and Youth conference in Nome, Alaska. Unmentioned among many other local dance teams, there was a performance by a small group from the village of Shishmaref. Fourteen years ago, on my visit to Shishmaref in 1991, no Native dance was practiced in the community and nobody, including the elders, remembered how to dance, due to the old ban on traditional ceremonies imposed by the village Lutheran church. Today, Native dances are again alive and thriving.

-

[4]

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Native whaling has been extended to several Alaskan communities that lost their tradition of whaling (like Wales and Diomede) or were never active in whaling in “the old days” (like Kivalina, Kaktovik, or Nuiqsut). In the 1990s, Native whaling was also reestablished in Chukotka, after being suppressed for almost 40 years, due to the state-imposed ban on village subsistence whaling (Krupnik 1987).

-

[5]

A good example is the heritage documentation effort in Western Alaska (Yukon-Kuskokwim area) initiated by the recent discovery of several hundred historical color slides taken by Dr. Leuman M. Waugh in the 1930s. Although the collection itself was first processed and examined by the Smithsonian anthropologists, the Calista Elders Council took the leading role in the collection and dissemination of the information related to the old images (see Fienup-Riordan 2005: viii).

-

[6]

The New York Times 2004, June 8, January 13; The Washington Post 2003, September 13, September 23; Independent 2003, September 24; Los Angeles Times 2002, March 31; National Geographic 2004; The New Yorker 2005, April 25.

References

- AINANA, Lyudmila, Victor TATYGA, Petr TYPYGHKAK and Igor A. ZAGREBIN, 2003 Baidara. Traditsionnaia kozhanaia lodka beregovykh zhitelei Chukotskogo poluostrova / Baydara. Traditional Skin-Boat of the Coastal People of the Chukchi Peninsula, Provideniya and Anchorage, National Park Service (Russian and English versions).

- AGRAWAL, Arun, 1995a Dismantling the Divide Between Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge, Development and Change, 26(2): 413-439.

- AGRAWAL, Arun, 1995b Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge: Some Critical Comments, Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor, 3(3): 1-10.

- ANUNGAZUK, Herbert O., 2003 Whaling: Indigenous Ways to the Present, in Allen P. McCartney (ed.), Indigenous Ways to the Present, Native Whaling in the Western Arctic, Edmonton and Salt Lake City, Canadian Circumpolar Institute and University of Utah Press: 427-432.

- ARNESTAD FOOTE, Berit, 1992 The Tigara Eskimos and Their Environment, Point Hope, North Slope Borough. Commission on Iñupiat History, Language, and Culture.

- BERKES, Fikret, 1999 Sacred Ecology. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management, London and Philadelphia, Taylor and Francis.

- BODENHORN, Barbara, 1997 “People Who Are Like Our Books”: Reading and Teaching on the North Slope of Alaska, Arctic Anthropology, 34(1): 117-134.

- BOGOSLOVSKII, Sergei, 2004 An’yapik. The Eskimo Hunting Umiak. Beringia, Severnye Prostory/Northern Expanses, 1-2: 50-56.

- BORLASE, Tim, 1993 Labrador Studies: The Labrador Inuit, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador East Integrated School Board.

- BRAUND, Stephen R. and Elisabeth L. MOOREHEAD, 1995 Contemporary Alaska Eskimo Bowhead Whaling Villages, in Allen P. McCartney (ed.), Hunting the Largest Animals: Native Whaling in the Western Arctic and Subarctic, Edmonton, Canadian Circumpolar Institute: 253-279.

- BURCH, Ernest S. Jr., 1981 Traditional Eskimo Hunters of Point Hope, Alaska, 1800-1875, Barrow, North Slope Borough

- BURCH, Ernest S. Jr., 1998 The Iñupiaq Eskimo Nations of Northwest Alaska, Fairbanks, University of Alaska Press.

- BURNHAM, Dorothy K., 1992 To Please the Caribou. Painted Caribou-skin Coats Worn by the Naskapi, Montagnais, and Cree Hunters of the Quebec-Labrador Peninsula, Toronto, Royal Ontario Museum.

- CAMPBELL, John Martin (ed.), 1998 North Alaska Chronicle: Notes from the End of Time. The Simon Paneak Drawings, Santa Fe, Museum of New Mexico Press.

- CROWELL, Aron L., 2004 Terms of Engagement: The Collaborative Representation of Alutiiq Identity, Études/Inuit/Studies, 28(1): 9-35.

- CROWELL, Aron L., Amy F. STEFFIAN and Gordon L. PULLAR (eds), 2001 Looking Both Ways. Heritage and Identity of the Alutiiq People, Fairbanks, University of Alaska Press

- ELLANA, Linda J. and George K. SHERROD, 2004 From Hunters to Herders. The Transformation of Earth, Society, and Heaven Among the Inupiat of Beringia, edited by Rachel Mason, Anchorage, National Park Service.

- FAIR, Susan W., 2004 Names of Places, Other Times: Remembering and Documenting Lands and Landscapes near Shishmaref, Alaska, in Igor Krupnik, Rachel Mason and Tonia Horton (eds), Northern Ethnographic Landscapes: Perspectives from Circumpolar Nations, Washington DC, Arctic Studies Center, Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology, 6: 230-254.

- FIENUP-RIORDAN, Ann, 1996 The Living Tradition of Yup’ik Maska. Agayuliyararput. Our Ways of Making Prayer, Seattle and London, University of Washington Press.

- FIENUP-RIORDAN, Ann, 1998 Yup’ik Elders in Museums: Fieldwork Turned on Its Head, Arctic Anthropology, 35(2): 49-58.

- FIENUP-RIORDAN, Ann (ed.), 2005 Yupiit Qanruyutait. Yup’ik Words of Wisdom, Transcriptions and Translations from the Yup’ik by Alice Rearden with Marie Meade, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press.

- FISHMAN, Joshua A., 1991 Reversing Language Shift. Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages, Clevedon, Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- FOX, Shari, 2002 These Things That Are Really Happening: Inuit Perspectives on the Evidence and Impacts of Climate Change in Nunavut, in Igor Krupnik and Dyanna Jolly (eds), The Earth Is Faster Now. Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, Fairbanks, ARCUS: 12-53.

- FREEMAN, Milton M.R., Lyudmila BOGOSLOVSKAYA, Richard A. CAULFIELD, Ingmar EGEDE, Igor I. KRUPNIK and Marc G. STEVENSON, 1998 Inuit, Whaling, and Sustainability, Walnut Creek, CA, Altamira Press.

- HALLENDY, Norman, 2001 Inuksuit. Silent Messengers of the Arctic, Vancouver and Toronto, Douglas & McIntyre and University of Toronto Press.

- HASSOL, Susan Joy, 2004 ACIA, Impacts of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- HELANDER, Elina and Tero MUSTONEN (eds), 2004 Snowscapes, Dreamscapes – A Snowchange Book on Community Voices of Change, Tampere, Tampere Polytechnic Publications, Ser. C., Study Materials 12.

- HUNTINGTON, Henry, and the Communities of Buckland, Elim, Koyuk, Point Lay, and Shaktoolik, 1999 Traditional Knowledge of the Ecology of Beluga Whales (Delpinapterus leucas) in the Eastern Chukchi and Northern Bering Seas, Alaska. Arctic 52(1):49 –61.

- HUNTINGTON, Henry and Shari FOX, 2005 Indigenous Perspectives on the Changing Arctic, in R. Corell (ed.), Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA), Arctic Council and Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- IKUTA, Hiroko, 2004 “We Dance Because We Are Iñupiaq.” Iñupiaq Dance in Barrow, Alaska: Performance and Identity, M.A. Thesis, Fairbanks, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- JOLLES, Carol Zane with Elinor MIKAGHAQ OOZEVA, 2002 Faith, Food, and Family in a Yupik Whaling Community, Seattle and London, University of Washington Press.

- JOLLES, Carol Zane with Elinor MIKAGHAQ OOZEVA, 2003 When Whaling Folks Celebrate: A Comparison of Tradition and Experience in Two Bering Sea Whaling Communities, in Allen P. McCartney (ed.), Indigenous Ways to the Present: Native Whaling in the Western Arctic, Edmonton and Salt Lake City, Canadian Circumpolar Institute and University of Utah Press: 307-340.

- KARI, James and James A. FALL (compilers), 2003 [1987] Sheme Pete’s Alaska. The Territory of the Upper Cook Inlet Dena’ina, Fairbanks, University of Alaska, Alaska Native Language Center, 2nd edition.

- KASSAM, Karim-Aly S. and the WAINWRIGHT TRADITIONAL COUNCIL, 2000 Passing on the Knowledge, Mapping Human Ecology in Waingwright, Alaska, Calgary, Arctic Institute of North America.

- KOBAYASHI ISSENMAN, Betty, 1997 Sinews of Survival, The Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing, Vancouver, UBC Press.

- KRAUSS, Michael E., 1973a Eskimo and Aleut, in Thomas Sebeok (ed.), Linguistics in North America, The Hague, Mouton, Current Trends in Linguistics, 10(2): 796-902.

- KRAUSS, Michael E., 1973b Na-Dene. 1973, in Thomas Sebeok (ed.), Linguistics in North America, The Hague, Mouton, Current Trends in Linguistics, 10(2): 903-978.

- KRAUSS, Michael E., 1980 Alaska Native Languages: Past, Present, and Future, Fairbanks, University of Alaska, Alaska Native Language Center, Research Papers, 4.

- KRUPNIK, Igor, 1987 The Bowhead versus the Gray Whale in Chukotkan Aboriginal Whaling, Arctic, 40(1): 16-32.

- KRUPNIK, Igor, 2000a Native Perspectives on Climate and Sea-Ice Changes, in Henry Huntington (ed.), Impacts of Changes in Sea Ice and Other Environmental Parameters in the Arctic, Bethesda, MD, Marine Mammal Commission: 25-39.

- KRUPNIK, Igor, 2000b Recaptured Heritage: Historical Knowledge of Beringian Yupik Communities, Arctic Studies Center Newsletter, 8: 9-10.

- KRUPNIK, Igor, 2001 Pust’ govoriat nashi stariki. Rasskazy aziatskikh eskimosov-yupik. Zapisi 1975-1987 gg (Let Our Elders Speak. Stories of the Yupik/Asiatic Eskimo. 1975–1987), Moscow, Russian Institute of Cultural and Natural Heritage.

- KRUPNIK, Igor, 2002 Watching Ice and Weather Our Way. Some Lessons From Yupik Observations of Sea Ice and Weather on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, in Igor Krupnik and Dyanna Jolly (eds), The Earth Is Faster Now. Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, Fairbanks, ARCUS: 156-197.

- KRUPNIK, Igor, 2004 The Whole Story of Our Land. Ethnographic Landscapes in Gambell, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, in Igor Krupnik, Rachel Mason and Tonia Horton, (eds), Northern Ethnographic Landscapes: Perspectives from Circumpolar Nations, Washington DC, Arctic Studies Center, Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology, 6: 203-227.

- KRUPNIK, Igor and Dyanna JOLLY (eds), 2002 The Earth Is Faster Now, Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change, Fairbanks, ARCUS.

- KRUPNIK, Igor and Elena A. MIKHAILOVA, in press Landscapes, Faces, and Stories: Aleksandr Forshtein Photo Collection, 1927-1929, Alaska Anthropological Journal.

- KRUPNIK, Igor and Vera OOVI (eds), in press Faces of Alaska. Photographs of the Old Years in the Norton Sound-Bering Strait Region. 1. St. Lawrence Island, Washington DC, Arctic Studies Center, Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology, 8.

- KRUPNIK, Igor and Nikolai VAKHTIN, 1997 Indigenous Knowledge in Modern Culture. Siberian Yupik Ecological Legacy in Transition, Arctic Anthropology, 34(1): 236-252.

- KRUPNIK, Igor and Nikolai VAKHTIN, 2002 Remembering and Forgetting: Culture Change and Indigenous Knowledge in Chukotka in the post-Jesup Era, paper presented at the Conference “The Raven Arch. Jesup North Pacific Expedition Revisited,” Sapporo, November 2002.

- KRUPNIK, Igor, Willis Walunga and Vera Metcalf (eds), 2002 Akuzilleput Igaqullghet. Our Words Put to Paper. Sourcebook in St. Lawrence Island Yupik Heritage and History, Igor Krupnik and Lars Krutak, compilers, Washington DC, Arctic Studies Center, Contributions to Circumpolar Anthropology, 3.

- KRUTAK, Lars with Christopher KOONOOKA (Petuwaq), 2003 Uglalghii Keluk Unguvalleghmun. Many Stitches for Life. History of St. Lawrence Island Yupik Tattoo, unpublished heritage sourcebook quoted with authors’ permission.

- LARSON, Mary Ann, 2003 Festival and Tradition: The Whaling Festival at Point Hope, in Allen P. McCartney (ed.), Indigenous Ways to the Present: Native Whaling in the Western Arctic, Edmonton and Salt Lake City, Canadian Circumpolar Institute and University of Utah Press: 341-356.

- LEE, Molly C. (ed.), 1999 Not Just a Pretty Face. Dolls and Human Figurines in Alaska Native Cultures, Fairbanks, University of Alaska Museum.

- MacDONALD, John, 1998 The Arctic Sky. Inuit Astronomy, Star Lore, and Legend, Toronto and Iqaluit, Royal Ontario Museum and Nunavut Research Institute.

- McDONALD, Miriam, Lucassie ARRAGITAINAQ and Zack NOVALINGA (compilers), 1997 Voices from the Bay. Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Inuit and Cree in the Hudson Bay Bioregion, Ottawa and Sanikiluaq, Canadian Arctic Resources Committee and Environmental Committee of Municipality of Sanikiluaq.

- METCALF, Vera (ed.), 2004 Pacific Walrus. Conserving Our Culture Through Traditional Management, Preliminary Project Report, Nome, Eskimo Walrus Commission, Kawerak, Inc.

- OOZEVA, Conrad, Chester NOONGWOOK, George NOONGWOOK, Christina ALOWA and Igor KRUPNIK, 2004 Sikumengllu Eslamengllu Esghapalleghput – Watching Ice and Weather Our Way, Igor Krupnik, Henry Huntington, George Noongwook, and Christopher Koonooka (eds), Washington DC, Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann (ed.), 2003 Qulirat Qanemcit-llu Kinguvarcimalriit. Stories for Future Generations. The Oratory of the Yup’ik Eskimo Elder Paul John, translated by Sophie Shield, Seattle and London, University of Washington Press, in association with the Calista Elders Council.

- SCHAAF, Jeanne (ed.), 1996 Ublasaun. First Light. Inupiaq Hunters and Herders in the Early Twentieth Century, Northern Seward Peninsula, Alaska, Anchorage, National Park Service, Shared Beringia Program.

- Senungetuk, Vivian and Paul Tiulana, 1989 A Place for Winter. Paul Tiulana’s Story, Anchorage, The CIRI Foundation.

- Thorpe, Natasha, Naikak HAGONKAK, Sandra EYEGETOK and the Kitikmeot Elders, 2001 Thunder on the Tundra. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit of the Bathurst Caribou, Vancouver, Generation Printing.

- VUKVUKAI, Nadezhda, 2004 The Kerker World, Beringia, Severnye Prostory/Northern Expanses, 1-2: 80-82.

- WALUNGA, Willis (Kepelgu), Chester NOONGWOOK (Tapghaghmii) and Christopher KOONOOKA (Petuwaq), 2004 Ayveghem Yupighestun Aatqusluga. St. Lawrence Island Yupik Walrus Dictionary, Igor Krupnik, compiler, unpublished illustrated catalog, draft copy on file, Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution, Arctic Studies Center.

List of figures

Figure 1

Gambell village Yupik dance performance, ca 1964.

Figure 2

Savoonga village dance team performs at the Elders-Youth annual conference in Nome, February 2004.

Figure 3

Printed materials used for the Yupik Language and Heritage classes at the Gambell high-school, 2004.

10.7202/012637ar

10.7202/012637ar