Abstracts

Abstract

This paper uses a comparative case study approach to assess convergence between three areas of Canadian, US, and Mexican policy that shape (im)migrant access to health and social services. These three areas include key policies and programs in relation to Immigration and Citizenship rights; Temporary and Foreign Labour Visa Programs; and Health and Human Services programs and policies. The paper takes a meso-level approach and compares policy and programming trends among public and private organizational actors and fields in Canada, the US, and Mexico at societal, political and technical levels. Ultimately, the paper finds that despite local level innovation, there is a large degree of agreement in all three policy areas, as well as increasing convergence at social, political, and technical levels. Theoretically, the paper contributes to recent debates about how to assess policy convergence, as well as debates about the impact of globalization on policy convergence. Practically, understanding local dynamics of immigration and health policy convergence serves to develop realistic and informed policy and programs at the international, national, and local levels.

Résumé

À l’aide d’une approche comparative d’étude de cas, le présent article évalue la convergence entre trois secteurs de politique canadiens, états-uniens et mexicains, qui façonnent l’accès des immigrants aux services sociaux et de santé. Ces trois secteurs comprennent des politiques et des programmes clés en rapport avec les droits en matière d’immigration et de citoyenneté, les programmes de visa pour la main d’oeuvre temporaire et étrangère, et les programmes et politiques des services de santé et services sociaux. L’article suit une approche de niveau moyen et compare les tendances en matière de politiques et de programmes parmi les acteurs et les champs d’activité d’organisations publiques et privées au Canada, aux États-Unis et au Mexique, aux niveaux sociétal, politique et technique. Enfin, le document constate qu’en dépit de certaines innovations au niveau local, il existe un degré important d’entente dans les trois secteurs de politique, ainsi qu’une convergence croissante aux niveaux social, politique et technique. Théoriquement, le document contribue aux récents débats sur la manière d’évaluer la convergence politique ainsi qu’aux débats concernant l’impact de la mondialisation sur la convergence politique. En pratique, le fait de comprendre les dynamiques locales de convergence de la politique en matière d’immigration et de santé, sert à élaborer des politiques et des programmes réalistes et éclairés aux niveaux international, national et local.

Article body

Introduction

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) significantly increased the flow of goods, capital, and labour between the US, Mexico, and Canada. Since NAFTA, however, North American trade and immigration policies, such as the Security and Prosperity Partnership, have not addressed the separate-but-connected issues of the need for labour in many economic sectors and whether to provide amnesty for the millions of undocumented migrants living and working in all three countries of North America. At the federal level, all three nations have been reluctant to reform immigration policy significantly. In the US, after the failure of immigration reform in 2005–2006, the federal government left immigration legislation to state and local jurisdictions (Progressive States Network 2008) where many controversial anti-immigrant laws have since been passed. In 2008 Mexico changed its Constitution in response to US pressure to lessen draconian sanctions against undocumented immigration and reduce human right abuses of migrants; and in 2009 Canada passed Bill C-50 to reduce flows of Mexican migrants. Aside from these policies, US, Canadian, and Mexican, provincial, state, and local actors have had a relatively large degree of slack to generate local-level policy and programs (Lune 2007). Consequently, throughout North America, migration flows have shifted away from county, city, and state jurisdictions that have passed anti-immigrant policies reducing social programs, and toward jurisdictions that have passed more encouraging measures or become Sanctuary Cities. Given the wide range of slack, the shifting nature of (im)migration and the emergence of a diverse range of both pro- and anti-immigrant local-level policy and program innovations, in what direction is policy moving?

This paper assesses convergence between three sets of Canadian, US, and Mexican policies that shape (im)migrant access to health and human services: immigration policies, temporary and foreign labour policies and visa programs, and health and human services policies. At the practical level, understanding immigration and health policy convergence helps to develop realistic and informed policy and programs. Theoretically, the paper contributes to recent debates about how to assess policy convergence, as well as debates about the impact of globalization and neoliberal economic policies on policy convergence.

In debates about policy convergence, many have criticized the assumption that modernization and globalization lead to a convergence of national policies governing areas such as environment, consumer health and safety, and regulation of labour (Bayrakal 2005; Drezner 2005, 2005; Blank and Burau 2006; Park 2002). In one of the few comparative health-policy-convergence studies, Blank and Burau (2006) examine policy convergence in nine industrial countries, showing that clusters of convergence exist primarily at the ideational level, whereas actual practices on the ground continue to vary widely across countries. The main problem with convergence theory is that the conceptual framework(s) of convergence studies remains vague. This paper uses Blank and Burau’s multi-level framework to “unpack,” assess, and compare levels of convergence across three policy domains. Blank and Burau suggest a framework that distinguishes between three substantive areas—the social, political, and technical—of health policy and their corresponding goals (intent to deal with common policy problems), content (formal policy), and instruments (institutional tools to administer policy) (see Table 1).

Table 1

Framework—Substantive and Procedural Aspects of Health Policy Convergence

Park (2002) and Bayrakal (2005) also point out that some recent examples of globalization and policy convergence studies focused on “meso-level” interaction among non-state and sub-national actors and institutions, a point that Drezner (2005) and other researchers largely ignore as they focus on state-based regulatory mechanisms. Alternative (non-state and sub-national) regulatory mechanisms (including industry- and sector-specific voluntary agreements, self-regulatory standards, information-based disclosure requirements, and transnational civil society networks) are becoming an important supplement, if not substitute, for traditional state-based government policy making and as such are important for understanding policy innovation and convergence.

Research Methods

This project utilized a case study approach (Yin 2003), combining qualitative ethnographic methods (participant observation, in-depth semi-structured interviews, archival research, policy analysis) to gather data for comparative analysis across numerous knowledge domains for each of the cases. Using a mixed methods approach to conduct comparative case studies has become common in the social sciences (Creswell 2003), particularly for researching complicated social and health problems (Needle, Trotter, et al. 2003).

The three cases consist of three separate but overlapping organizational fields (Dimaggio and Powell 1983). The primary research sites were regions in Canada, the US, and Mexico where large numbers of (Latino) transnational migrants and immigrants live as members of either sending or receiving communities, and where there exist significant bi- and trilateral US–Mexico–Canada health initiatives. These regions were Ontario, Canada (Leamington, Windsor, Toronto, Ottawa); Central Mexico (State of Mexico, Federal District, Puebla); and California (Los Angeles, San Diego).

In-depth interviews were conducted with actors from three knowledge and action domains: (a) state public health policy and program decision-makers; (b) representatives of community-based NGOs; and (c) representatives of transnational organizations (foundations, development agencies, and international NGOs) working within and across North American borders on migrant and immigrant health. Participant observation also occurred at key events, including applied health forums, conferences, health policy planning meetings and civil society events in Mexico, Canada, and the US. Finally, a historical comparative analysis of archival data, such as health policy documents, conference and workshop proceedings, and organizational literature (including brochures, websites, annual reports, and internal documents) was conducted to provide a foundation for the multiple sources of qualitative ethnographic data. Data from interviews, participant observation, and archival documents were triangulated to generate a historical comparative analysis of trends, patterns, and explanations for levels of policy convergence (or divergence). Data was organized into three comparative matrixes to assess the societal, political, and technical aspects of policy convergence (see Tables 3a, 3b, 3c).[2]

Framework for Assessing Health Policy Convergence

The analytic framework assesses (dis)agreement between policy goals, content, and instruments, at societal, political, and technical levels. The societal level refers to larger immigration policies that can shape (im)migrant access to citizenship and therefore to health and social services. At the social level it’s important to remember that the funding and administration of health services in the US, Canada, and Mexico are significantly different. Canada and Mexico mandate the constitutional right of citizens to health care and have socialized health care systems that are more “open” to migrants. The US, in contrast, operates largely on a private model with some public services and programs for the elderly, poor, and children, and in some cases for migrants.

At the political level, the focus is on (im)migrant policies and programs, such as the H-2 Visa Program in the US, the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) in Canada, and the Mexico–Guatemala Temporary Agricultural Worker Program. Existing within or alongside these temporary worker programs are policies and programs directed specifically at migrant health. For example, Canada’s SAWP mandates immediate access to health care for migrants by mandating that workers purchase private medical insurance for the first 90 days in Canada. After that, access to “free” provincial medical care begins. For Mexican (im)migrants in the US, the Mexican government provides information about health services through consular “Health Counters” (Ventanillas de Salud) and the Binational Health Week. Mexico also provides health care to returning Mexican (im)migrants via the Programa Paisano (Countryman Program), Vete y Regresa Sano (Leave and Return Healthy) and the Programa Salud del Migrante (Migrant Health Program).

The technical level focuses on the implementation of policy and the mechanisms by which actors do the actual work of “managing” (by enforcing, ignoring, or challenging) laws and policy and serving (or not) the (im)migrant population. At this level, the linkages (and disconnects) between policy convergence and sub-national, non-state actors become more evident, particularly the role of civil society actors in policy and program innovation and creating “alternative regulatory mechanisms” (Park 2002).

Population Focus

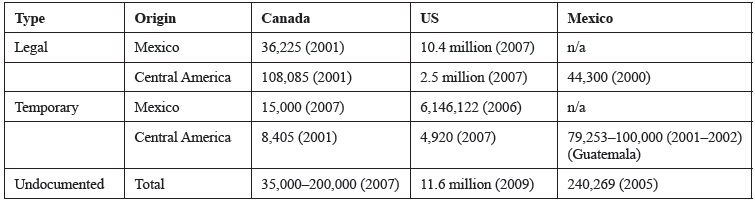

It is estimated that more than 28 million Latin American and Caribbean people live outside their country of origin (Sohnen 2008). Yet only 3.7% of Latin Americans abroad have access to social security benefits and “advanced portability” regulated by bilateral agreements. Simply stated, immigration in North America is stratified into two main classes. The first class consists of those who have high levels of education and skills, work in the professional sector, and have permanent or temporary (i.e., the H-1B Visa in the US) legal status. The second class consists of temporary foreign labour with lower levels of education who work in manual fields or agricultural labour (i.e. the H-2A or H-2B Visa in the US), and those with undocumented status. The focus of this paper is on the second class of (im)migrants (see Table 2).

Table 2

Legal, Temporary, and Undocumented Immigrants in Canada, the US, and Mexico

In the US, the size of the temporary worker population was approximately 6,151,042 in 2006–2007 (Wedemeyer 2006; Office of Immigration Statistics 2007). In Canada about 25,000 workers entered via the SAWP in 2007 (Gibb 2006). Mexico also relies on about 100,000 temporary labourers from Central America, who work in agriculture and construction (OIM 2003). In terms of undocumented labour, in the US, the size of the undocumented population is estimated at 11.6 million (Hoefer, Rytina, and Baker 2009). Canada’s undocumented population is much smaller, estimated at between 35,000–200,000 (Gibb 2006; Crepeau and Nakache 2006). Mexico’s undocumented population is estimated at 240,269, the majority of whom are from Guatemala and Honduras (OIM 2003).

Assessing Levels of Policy Convergence

Societal Level

The societal level encompasses the dominant values and norms that shape debates and changes in immigration and temporary labour policy, and health and social service policy. In general, despite sharing many of the same labour needs, each country has a distinctive stance toward immigration policy and assimilation (See “Policy Goals” in Table 3a). The US is considered a “melting pot” in which immigrants blend and assimilate; Canada is a multiculturalist “mosaic” of distinct cultures; Mexico, by contrast is highly nationalistic (Lazos 2008; Watson 2006; Waller 2006).

Table 3a

Framework for Assessing Health Policy Convergence—SOCIETAL LEVEL

A review of the main policy documents and debates in each country reveals that the tensions centre on “enforcement” versus “asylum” based approaches to deal with unauthorized immigrants (and their access to labour and health and social services; see Policy Content, Table 3a). On the enforcement side, all three nations have increased border security and enforcement as evidenced in the tri-lateral 2005 Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America, which promotes security integration and recommended the development of unified visa and refugee regulations by 2010 (Crepeau and Nakache 2006). However, only the US and Mexico have taken security implementation to the extent of militarizing their southern borders. Despite all three nations agreeing on the need for immigration reform to meet labour needs and resolve the problem of unauthorized migration, none have enacted any comprehensive measures, leaving large amounts of “slack” (Herold, Jayaraman, and Narayanaswamy 2006; Lune 2007) for local actors to interpret and innovate policy and programs at the state/provincial and local level.

In the US, the failure of immigration reform led to the introduction of another failed Bill, HR4437, one of a growing number of “enforcement only” immigration reform bills, making it a felony to be an undocumented non-citizen or to offer non-emergency assistance to an undocumented non-citizen. HR4437 sparked weeks of large nationwide demonstrations in support of immigrant rights and reform, including a national strike, school walk-outs, and consumer boycott on May 1, 2006 (Wedemeyer 2006). Bill HR4437 eventually died in the Senate, but Bill S.2611 was passed in its place, which has many of the same enforcement provisions as HR4437, but also includes a guest worker program that provides a path to residency and an amnesty provision that allows undocumented immigrants to become legal residents if they meet several requirements and pay a stiff fine. The enforcement approach of S.2611 includes implementation measures such as high profile workplace raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the temporary deployment of 6,000 National Guard troops to support the Border Patrol along the southern border, the hiring of 6,000 new Border Patrol agents by 2008, and building 700 miles of new fencing along the Mexican border (Wedemeyer 2006).

Amnesty approaches are less visible, but still popular in the US. The Pew Hispanic Center’s 2006 report on American public opinion finds that a significant majority of Americans see illegal immigration as a serious problem. However, a significant majority of Americans also believe that illegal immigrants are taking jobs Americans do not want, and favour measures to allow illegal immigrants currently in the US to remain in the country, either as permanent residents and eventual citizens, or as temporary workers who will eventually go home. American polls also indicate a majority in favour of amnesty (as permanent residents, eventual citizens, or temporary workers) over deportation (Pew Hispanic Center 2006). The proliferation of Sanctuary Cities (discussed further below) in the US is another indicator that amnesty approaches are widespread.

In comparison to the US and Canada, Mexico has the most restrictive immigration policy, denying until 2008 all fundamental rights to non-citizens and treating undocumented (im)migrants as criminals. In particular, Mexico’s treatment of Central American migrants is characterized by violence and human rights abuses. For example, in March 2008, Univision.com reported that Central American migrants were being persecuted by the Mexican police. The report stated that “the level of brutality seen during a police operation against undocumented migrants near a train station in Central Mexico, where a local man was killed because of the color of his skin and the style of his clothes seemed Central American” was unprecedented (Abusos de ilegales en México 2008). Witnesses (citizens and migrants) and reporters have provided evidence that the police “hunt” migrants at night and sexually abuse female migrants; migrants regularly report to human rights workers how they are victims of police, soldiers, and citizens that rob, rape, beat, and even kill migrants. Despite—or perhaps because of—such extreme anti-immigrant sentiment, many Mexican civil society actors have organized to meet the legal, health, and human service needs of Central American migrants in Mexico (Tobar 2008).

Canada has a different history of immigration policy than either the US or Mexico. In the case of unauthorized migrants, Canada takes an amnesty-first approach, providing the undocumented with asylum as their case makes it through the immigration system. A big question for most undocumented cases is whether they can legitimately claim asylum or are simply economic migrants. Very few Mexican asylum cases are accepted because most are seen as economic migrants; however, while their case is making its way through the system, the migrant often gets “lost” in the country so that by the time the deportation order comes through, he or she is untraceable.

Despite its relative historical openness to immigration, the majority of Canadians (two-thirds according to a Citizenship and Immigration Canada poll) favour deportation of illegal immigrants, even if they had family ties, “because they did not follow the rules” (Aubry 2007). In contrast, American polls indicate a majority in favour of amnesty over deportation (Pew Hispanic Center 2006). Canada’s recent shift from a Liberal government (2003–2006) to a Conservative one in February 2006 has shaped its recent stance on immigration. Increasingly, Canada is following the US model of tightened security on the border and using ICE-style immigration raids of the employers of undocumented workers (No One Is Illegal 2009). This shift is indicated by changes in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act proposed by Bill C-50 in 2009, which give the Conservative government considerable power in deciding immigration quotas, giving priority to specific immigration categories, and refusing applications (No One is Illegal 2008; Campion-Smith 2008). Specifically, in an attempt to deal with the large number of Mexicans claiming asylum, Bill C-50 mandates a new, somewhat controversial visa requirement for Mexicans; no visa has been previously required for Canadians visiting Mexico.

Access to Health and Human Services for (Im)migrants in the US, Mexico and Canada

Debates about immigrant use of public health care show the conflict between the goal of providing care, and enforcement-based immigration policies that deny access to care (Field Costich 2002). In Mexico, the US, and Canada, access to health and human services for migrant workers is viewed by public health and civil society actors as a human and labour right. At the societal level, all three nations have signed international documents supporting protection of the human rights of migrants (Crepeau and Nakache 2006), but policy implementation and enforcement at the local level is difficult, particularly in southern Mexico and along the US–Mexico border. As a result, the vast majority of health and human service providers in each country enact a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy by ignoring existing statutory barriers to health care for undocumented (im)migrants. The discordance between public health practices and immigration policy opens up space for local-level innovation; such innovative practices are observed at the political and technical levels of the policy assessment framework.

Political Level

(Anti) Immigrant Policy in Canada, the US, and Mexico

The political level compares specific policies that structure immigration and health systems, including state and municipal immigration laws, temporary and foreign labour programs, and migrant health policies and programs (see Table 3b). Given the lack of comprehensive immigration reform at the national level in all three countries, each state and province has much leeway to pass laws and create programs that structure access to labour rights and health care for migrants.

Table 3b

Framework for Assessing Health Policy Convergence—POLITICAL LEVEL

In the US, “States have displayed an unprecedented level of activity—and have developed a variety of their own approaches and solutions” (National Conference of State Legislators 2008). For example, according to the National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL) Immigrant Policy Project (NCSL 2006; NCSL 2008), “state legislators have introduced almost three times more bills in 2007 (1,562) than in 2006 (570) and the number of enactments from 2006 (84) has nearly tripled to 240 in 2007.” Much of the legislation focused on restrictions in the areas of employment, health, identification, drivers and other licenses, law enforcement, public benefits, and human trafficking. As a result of the climate of fear produced by anti-immigrant policies, many immigrants have stopped shopping or going to church and have closed bank accounts (Constable 2008; Southern Poverty Law Center 2007), and may also limit use of social and health services (Field Costich 2002). Another result is increasing internal migration away from anti-immigrant areas (such as Oklahoma and Arizona) to more immigrant friendly regions in the US (Archibold 2008; Pinkerton 2008).

In addition to fleeing conservative states for more liberal locales in the US, immigrants are also moving north, into Canada. Canada has had an historical commitment to immigrant and refugee rights, affirmed in 2001 with the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. In September 2007 the Windsor–Peel, Ontario area experienced an “explosion” of Mexican migrants claiming refugee status (Hall 2008; Waldie, Freeman, and Perkins 2007). However, Mexican applicants for refugee status in Canada are usually denied because they are seen as economic migrants, not refugees. Yet once in Canada, while waiting for their claim to clear the system (a process that could take years), the Mexican claimant is given a work permit and a health card, and as time passes, often becomes part of the growing non-status population living and working in Canada (Canadian Council for Refugees 2007; Goldring, Berinstein, and Bernhard 2007).

As stated above, Mexico has had the most restrictive immigration policy until 2008. Despite the change in law, the practice of illegal immigration is still viewed as a criminal act. In March 2008, because of media and civil society outrage, Jorge Bustamante (the “Relator Especial” for the Mexican Human Rights Commission) exhorted the Mexican Government to fulfill their responsibility on Mexico’s southern border. “What we do to the Central Americans that come into our country without papers,” he stated, “does not qualify us as an exemplar country. There are human rights violations worse than what happens to our countrymen in the US” (Ballinas and Becerril 2008).

Policy Content and Instruments: Temporary and Foreign Labour Programs in Canada, the US, and Mexico

The current trend in immigration policies of most major countries is to reduce permanent settlement of unskilled labour in favour of “re-forming” temporary migration visa programs. The core for implementing US, Mexican, and Canadian immigration and labour policy is visa programs that release a limited amount of temporary skilled labour (H-1) visas, as well as a larger number of temporary unskilled (agriculture H-2A and seasonal H-2B labour) visas. The effect is a two-tiered system that favours employer use of cheap, temporary, foreign labour. At the societal level, all three countries acknowledge that there is a need to reform existing temporary labour programs and policy in order to meet long-term demands for labour and prevent the abuse of workers. Yet at the political level, debates have focused on expanding and streamlining temporary visa programs in ways to make it easier for employers and the government to increase labour mobility and provide foreign workers with a fewer labour protections. Below, I outline the content of instruments of US, Canadian, and Mexican visa programs, including the rights and responsibilities of employers and workers, and program abuses and sanctions.

The US H-1, H-2A, and H2-B Visa Programs

To (im)migrate to the US, individuals can apply for either an H-1 or an H-2 visa. H-1 visas are granted to highly skilled individuals (professionals). This paper focuses on workers entering with H-2A visas (seasonal agricultural workers) and H-2B visas (temporary non-agricultural workers in industries such as forestry, construction, landscaping, services, meat and vegetable packing, fishing, tourism, etc.). In 2007 the US admitted 87,316 H-2A visa workers, 79,394 of whom were from Mexico (US Citizenship and Immigration Services 2008). The top receiving US states were North Carolina (25% of labour certifications), Georgia (13.9%), and Virginia (9.2%) (Wedemeyer 2006). In 2007 the US also admitted 154,892 workers on H-2B visas, with 105,244 returning back to Mexico (US Citizenship and Immigration Services 2008).

Despite the fact that H-2A and H-2B visa holders are supposed to guarantee worker rights and protections, abuses are common (Wedemeyer 2006; Bauer 2007; Farmworker Justice 2008). For example, employers frequently use the non-agricultural H-2B labour certification to import agricultural workers (especially in the area of packing produce) because the H-2B visa is less costly to obtain than the H2-A visa. Other documented examples of the exploitation of H2-B workers include being cheated of wages, being denied overtime pay, being held captive by employers who “hold” worker identity documents, being forced to live in unhealthy conditions, and being denied medical benefits (Bauer, 2007). Workers are also often recruited by firms that charge them for visas (i.e. $2,500 for a Guatemalan worker, $20,000 for an Asian worker) and transportation; often workers go into debt just to get a visa to work in the US. “Workers are systematically exploited because the very structure of the program places them as the mercy of a single employer and provides no realistic means for workers to exercise the few rights they have” (Farmworker Justice 2008). As well, evidence from H-2B court cases shows that employers and recruiters discriminate by gender as they steer women into H-2B visas while reserving H-2A visas for men; employers and recruiters are also notorious for discriminating on the basis of age (Bauer 2007; Wedemeyer 2006). As documented by the Southern Poverty Law Center, if guest workers complain, they face deportation, arbitrary firings, and blacklisting or other forms of retaliation (Southern Poverty Law Center 2007).

One of “the most unacceptable aspect of guest worker programs is the limitation placed on the mobility of imported workers within the labour market, which goes against the very grain of liberal democratic principles” (Griffith 2006). According to Griffith and others, the exploitative nature of the temporary and seasonal visa programs linked to the unbalanced power relations between employers and workers is akin to slavery or indentured servitude. Additionally, the implementation of guest worker programs is characterized by a lack of Department of Labour (DOL) enforcement of employer violations. Moreover, in cases where the DOL is aware of employer violations, it frequently takes no legal action (Bauer 2007; Wedemeyer 2006; Farmworker Justice 2008). The DOL has been silent despite the fact that since its inception the agricultural sector has used the H-2A program to import cheap foreign labour, even when there are domestic labour surpluses.

The Canadian Seasonal/Temporary Agricultural Worker Program

In 1974 Canada and Mexico formed the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) Mexico–Canada (Trejo García and Álvarez Romero 2007) and in 2007 issued approximately 25,000 visas, 15,000 to Mexican workers. The general framework and implementation are similar to the US H-2A visa. Like the US program, Canada’s SAWP provides certain social protections to the migrant (pension plan contributions, vacation pay, workers’ compensation, health care). Again, employer abuses are amply documented, but accessing legal rights is problematic because workers are either uninformed or wary of claiming entitlements for fear of blacklisting and deportation (Farmworker Justice 2008; McLaughlin 2008; Preibisch 2007; Petrich 2005).

Mexico–Guatemala Temporary Agricultural Labour Program

The temporary foreign worker flows of Central Americans on Mexico’s southern border have increased in number, geographic scope, and economic sectors from the mid-1900s to present (Trabajadores Migratorios Temporales en la Frontera Sur de México 2005). Low economic development and high poverty rates cause many Central Americans to migrate to Mexico’s southern border (and the US and Canada) to work in the agricultural sector. Most work is in the coffee sector in Chiapas, however, new labour markets in service and construction have emerged where migrants can earn double or triple the average salary. As in the US and Canada, the visa stipulates the migrant can only work for one employer, has the right to social security and medical care, and has the right to receive minimum wage. However, given the backlog and the deficiencies in the National Migration Institute’s (INM) ability to process documents (specifically Forma Migratoria para Visitante Agrícola (FMVA), many migrants arrive in Mexico without documents; furthermore the FMVA in Chiapas is granted within the Mexican territory, i.e., while Guatemalans are already in Mexico. Entering without documents is relatively easy, as the Guatemala–Mexico border has many puntos ciegos (blind spots) where an indeterminate number of both documented and undocumented workers cross in both directions daily (Herrera Ruiz 2003).

Given its level of disorganization, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) acknowledges that “the labor market across the border between Guatemala and Mexico has traditionally posed practices in which the minimum protection guarantees are diminished for labor rights of temporary migrant workers, affecting directly the social and economic labor conditions of the worker and his family” (OIM 2003, 4). Finally, in early 2008, the Mexican National Human Rights Commission opened investigation into the treatment of Guatemalan guest workers after media reports exposed bad working conditions, the use of child labour, and human trafficking (Hernández Navarro 2008; Abusos de ilegales en México 2008; Shepard-Durni 2008).

Policy Content and Instruments: Health Programs for Migrants

Alongside temporary and foreign labour visa programs, Mexico, the US, and Canada have developed a range of health policies and programs specifically for migrants with and without visas. Shared health problems have been a concern for the three countries since the early 1900s, when the first bilateral (US–Canada and US–Mexico) agreements were created to prevent animal-borne diseases. In the case of health policy, much more programming has occurred between the US and Mexico rather than the US and Canada or Canada and Mexico, largely because of rising rates of infectious disease (TB, hepatitis, HIV, etc.) in the populated, sister-city border areas shared by the US and Mexico (Collins-Dogrul 2007). In 1967 the Binational TB Commission was created, representing the first human health policy agreement between the US and Mexico. The next significant human health policy agreement, however, did not occur until the 1994 Border Health Commission Act, when the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) created the US–Mexico Border Health Task Force. To implement its migrant health programs, HRSA funds 1,612 migrant health centres distributed throughout the US. It is estimated that HRSA-funded health centre programs serve more than one-quarter of all migrant and seasonal farmworkers in the United States. In 2007 alone, HRSA-funded migrant health centres served more than 826,977 migrant or seasonal farmworkers and their families (HRSA 2007; Laws 2002).

In 2000 the US–Mexico Border Health Task Force created the first truly bilateral health organization—the US–Mexico Border Health Commission (USMBHC). Two of the most successful USMBHC health programs—organized with the Mexican government and health system—are the US–Mexico Binational Health Week and the Ventanillas de Salud (Health Counters) Program. As described above, the Health Counters are modules located in the Mexican consulates of 23 US states, where culturally competent outreach workers explain existing health insurance programs and inform the Mexican-origin population of available health services. The Health Counters program started in 2002 in the Los Angeles and San Diego consulates in collaboration with the Mexican consulate and community-based organizations.

In addition to providing services to Mexican migrants in both the US and Mexico, the Mexican Health Ministry provides services to the large population of Central American migrants on its southern border. The Ley Federal de Trabajo establishes the labour and health care rights of both nationals and foreign migrants. The temporary agricultural worker program between Mexico and Guatemala also establishes the right to health care for foreign migrants with a visa yet implementation of this policy is non-existent or weak at best. According to Rudolfo Casillas, a researcher with FLACSO, even though employers in Tapachula formed a network and signed an agreement with the Instituto México de Seguro Social (Mexican Social Security Institute, IMSS) to provide care to migrant workers, it left a significant number of migrants not covered. Additionally, many Central American migrants do not even know they have the right to access care or know how to access the IMSS system.

Compared to the long-term development of US–Mexico border health, Canada’s political and organizational response to migrant health is nascent yet robust. Unlike the US and Mexico, Canada’s visa program gives authorized migrants access to the Canadian public health system (for a fee) and many community health centres operate on a “don’t ask don’t tell” policy, providing services to all regardless of immigration status (Trejo García and Álvarez Romero 2007). Yet problems with accessing care still exist, in part due to language barriers and lack of knowledge of how to utilize the Canadian health system, but also because most migrants live and work in rural zones where health services are sparse and access is a problem even for Canadian citizens.

Technical Level

Enforcers versus Providers

The technical aspects of policy convergence include the actors, mechanisms, instruments, and strategies by which policy is implemented. In terms of the goals of policy at the technical level, all three countries converge on several points (see Table 3c): 1) the need to control (and reform) the (im)migration process; 2) the need to provide a limited amount of social services and health care to (im)migrant farmworkers; and 3) to shift the burden of care and enforcement to regional and local actors. An assessment of policy content at the technical level clearly indicates agreement toward expanding and shifting service provision and immigration enforcement to local and regional police, doctors, educators, employers, and community-based organizations (CBOs). The increasing involvement of regional and local Canadian, US, and Mexican civil society organizations in responding to (im)migrant health and human rights issues is a product of the global trends toward inclusive neo-liberalism in which North American countries have “shifted away from federal government control to greater roles for sub-national governments and civil society actors” (Mahon and Macdonald 2007).

Table 3c

Substantive and Procedural Framework for Assessing Health Policy Convergence—TECHNICAL (ENFORCER/PROVIDER) LEVEL

While there are many technical aspects to implementing these policies, here I highlight the roles of “enforcer” and “provider” instruments (as mechanisms and/or actors). Unlike previous studies that indicate little convergence at the technical level (Blank and Burau 2006), this study shows considerable agreement (indicated by merged cells in the table) of technical-level policy goals, content, and instruments.

First, all three countries have enacted post 9/11 border security policies that support increasing control of their borders (Crepeau and Nakache 2006). As stated above, the trilateral 2005 Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America promotes security integration and recommends the development of unified visa and refugee regulations by 2010. While Canada has agreed to increase border security and harmonize visa requirements, it has not gone as far as the US and Mexico, both of which have effectively militarized their southern borders.

Alongside the amplification of local policing resources dedicated to immigration enforcement in North America, are increasing numbers of high profile raids by Immigration Control and Enforcement (ICE) that target unauthorized (im)migrants (vs. employers). In the US, arrests of undocumented workers grew by 750% between 2002 and 2006; and there has been a trend toward large-scale immigration raids arresting between 99–1,200 workers at a time. These tactics have a humanitarian cost, resulting in the separation of children from parents, often for months at a time (Abraham 2008). Canadian immigration officials have adopted the US ICE-raid strategy and increased raids targeting (im)migrants (vs. employers), as evidenced by actions at a number of workplaces in Southern Ontario, arresting and detaining approximately one hundred unauthorized workers in Spring and Summer 2009 (No One Is Illegal 2009).

The Sanctuary City Movement

As a response to rising anti-immigrant sentiment and the militarization of borders, citizens in a number of US, Canadian, and Mexican states and cities have established Sanctuary Cities (SRE 2007). In the US, the Sanctuary City movement is widespread—all but 22 states have sanctuary cities (there are just over 120 cities in total), and Oregon, Alaska, and Maine are Sanctuary States. Some innovative local strategies include a San Francisco (which passed its Sanctuary City ordinance in 1989) city-sponsored public service campaign to assure undocumented immigrants that they are welcome and safe (McKinley 2008). In another response to anti-immigrant legislation passed in Prince William, Frederick, and Anne Arundel counties in Maryland, where immigrants have become afraid to attend church, drive, or go to the bank for fear of having a run-in with the local police (Constable 2008), Prince George and Montgomery counties (in Maryland) have publicized their support for new service centres for migrants and/or have taken a hands-off approach to immigration enforcement (“Anne Arundel goes after illegals” 2007).

Sanctuary Cities are spreading across North America. Canada started its own Sanctuary City movement in Toronto in 2009, and in Mexico, the mayor of Ecatepec (a suburb in the state of Mexico where migrants catch a freight train that arrives at the US–Mexico border) declared his city a sanctuary for illegal immigrants from Central America (Tobar 2008). Sanctuary Cities are a destination of migrants and immigrants fleeing less immigrant-friendly locales; however, such cities bear the brunt of the costs and benefits of migrants and immigrants (Juozapavicius 2008).

Conclusion

It is widely recognized that the North American economy benefits from migrant remittances, and that the labour market benefits as immigrants and migrants create more jobs and demand for goods and services (Fix 1994). It is less well-known that the migrant and immigrant labour-force pays a high price in terms of reduced well-being and productivity due to poor working conditions, exposure to pesticides, poor housing, and limited access to health services. Explanations for lack of access have typically focused on “internal” factors that reduce access to health care—problems possessed by the migrant or immigrant, such as financial, linguistic, and cultural barriers. Also important—but receiving less attention—are “external” factors that shape access to health care, such as 1) national sovereignty issues (who is “responsible” for migrants; legal/citizenship issues), 2) diversity of organizational actors and interests, 3) negative public opinion and anti-immigrant legislation. This paper assesses the external policy factors that shape migrant health and human service access.

At the societal level there is a strong degree of agreement between the US, Mexico, and Canada regarding the goals of immigration and migration reform, however given Canada’s multiculturalist immigration policy, the US and Mexico are closer in policy content and instruments. The political level also shows trilateral convergence regarding goals to increase temporary labour mobility while decreasing labour protection and providing limited services via public health and community-based organizations. Canada is also moving closer to the US in terms of instruments—i.e., increasing use of ICE-like immigration raids and the increasing role and importance of community organizations in providing health and human services to farmworkers. Finally, a strong degree of agreement in policy goals, content, and instruments also exists at the technical level in terms of expanding immigration control and enforcement by shifting gate-keeping (profiling) duties to local and regional police, doctors, educators, and social service providers, as well as increase the use of ICE-like immigration raids and mass deportations. On the provider side, there is increasing reliance on community-based services and advocacy (via “don’t ask don’t tell” practices) and the spread of the Sanctuary City movement from the US to Mexico and Canada.

In sum, this policy convergence study assesses societal, political, and technical levels of society across various policy domains (goals, content, and instruments) and finds a large degree of policy convergence at all levels. How is such agreement possible given that ample federal slack provides space for developing a diverse range of local policy and program innovations? One possibility for the surprising amount of policy convergence is the spread of local information via transnational civil society networks that inform and shape policy and program innovation and implementation. This possibility assumes that civil society networks can play a role in developing policy and programs “from below” in ways that both challenge existing political power structures and produce policy convergence. Local actors have certainly been given a central role in program service provision, yet the degree to which civil society actors are integrated into—versus given a “parallel space” for—the policy-making process is a question that remains to be explored

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

(Im)migrant is spelled and punctuated as such to indicate that the paper addresses both migrant and immigrant policies, as well as to indicate that in the case of the population under study migrant vs. immigrant status can be interchangeable.

-

[2]

Note: Policy convergence, or agreement, is indicated by merging cells in the tables.

Bibliography

- Abraham, Yvonne. “As immigration raids rise, human toll decried.” Boston Globe 20 May 2008. Boston Globe. 9 August 2011 http://www.boston.com

- Agricultural Workers Alliance. History of Agricultural Workers in Canada. awa-ata.ca Rexdale, Ont.: 2009.

- “Anne Arundel goes after illegals.” Washington Times 7 December 2007. Washington Times. 9 August 2011 http://www.washingtontimes.com

- Archibold, Randal. “Arizona Seeing Signs of Flight by Immigrants.” New York Times 12 February 2008. New York Times. 9 August 2011. http://www.nytimes.com

- Aubry, Jack. “Canadians Want Illegal Immigrants Deported: Poll.” National Post 20 October 2007. National Pst. 9 August 2011. http://www.nationalpost.com

- Azmier, Jason. “Western Canada's unique immigration picture.” Canadian Issues (Spring), 2005: 116-18.

- Ballinas, V., and A. Becerril. “ONU: Desde hace décadas legisladores de México tienen una deuda con migrantes.” La Jornada 12 March 2008. La Jornada. 9 August 2011. http://www.jornada.unam.mx/ultimas

- Barnes, Nielan. “Paradoxes and asymmetries of transnational networks: A comparative case study of Mexico’s community-based AIDS organizations.” Social Science and Medicine, 66.4 (fev. 2008): 933-944.

- Batalova, Jeanne. Spotlight on Temporary Admissions of Nonimmigrants to the United States. Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2008.

- Bauer, Mary. “Testimony of Mary Bauer before the Committee on Education and Labor.” Montgomery, Alabama: Southern Poverty Law Center, 2007.

- Bayrakal, Suna. “Determinants of Canada–US Convergence in Environmental Policy-Making: An Automotive Air Pollution Case Study.” International Journal of Canadian Studies 32 (2005): 109–49.

- “BC Government is Violating Canada Health Act: Mexican Migrant Farm Workers Denied Basic Medical Coverage.” 22 March 2006. Justicia Justice. 9 August 2011. http://www.justicia4migrantworkers.org/bc/pdf/bcviolating.pdf

- Bennett, C. J. “What is Policy Convergence and What Causes It?” British Journal of Political Science 21.2 (1991): 215–33.

- Blank, Robert, and Viola Burau. “Setting Heath Priorities across Nations: More Convergence than Divergence?” Journal of Public Health Policy 27.3 (2006): 265-281.

- Bustamante, Arturo Vargas, Gilbert Ojeda, and Xóchitl Castañeda. "Willingness to Pay for Cross Border Health Insurance between the United States and Mexico." Health Affairs 27, no. 1 (2008): 167-178.

- Campion-Smith, Bruce. “Immigration proposals to stand.” The Toronto Star 17 April 2008. The Toronto Star. 9 August 2011. http://www.thestar.com

- Canadian Council for Refugees. Media Advisory: “Refugee Claimants in Canada: Some Facts.” Ottawa: 9 October 2007.

- Casillas, Rudolfo. Una Vida Discreta, Fugaz y Anónima: Los Centroamericanos Transmígrates en México. Mexico City: FLACSO, 2006.

- CERIS. “Access Not Fear”: Non-status Immigrants and City Services. Toronto: 2006.

- CERIS. The Regularization of Non-Status Immigrants in Canada 1960–2004. Toronto: 2004.

- Collins-Dogrul, Julie. “Homogeneous Policy/Heterogeneous Processes: A Historical Comparative Analysis of Legislating “Border Health” in Mexico and the United States.” 2006. The Society for the Study of Social Problems 56th Annual Meeting.

- Constable, Pamela. “Immigrants feel less welcome in Frederick.” Washington Post 6 May 2008.

- Crepeau, Francois, and Delphine Nakache. “Controlling Irregular Migration in Canada: Reconciling Security Concerns with Human Rights Protection.” IRPP Choices 12.1 (2006).

- Creswell, J. W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2003.

- Department of Homeland Security. Office of Immigration Statistics. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2007.

- DiMaggio, P., and W. Powell. “The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields.” American Sociological Review 48 (1983):147-160.

- Drezner, Daniel. “Globalization, harmonization and competition: The different pathways to policy convergence.” Journal of European Public Policy 12.5 (October 2005): 841-859.

- National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE). “Excluding migrant farm workers violates Canada Health Act.” 28 March 2006. http://www.nupge.ca/news_2006/n28ma06b.htm 28 March 2006.

- Farmworker Justice. Litany of Abuses. Washington, DC: 2008.

- Fernandez, Emilio. “Deportan a mujer en estado vegetivo.” El Universal 25 February 2008.

- Field Costich, Julia. “Legislating a Public Health Nightmare: The Anti-Immigrant Provisions of the “Contract with America.” Kentucky Law Journal, 90 (2001–2002): 1043–70.

- Fix, Michael, and Jeffrey Passel. Immigration and Immigrants: Setting the Record Straight. Washington DC: Urban Institute, 1994.

- Gibb, Heather. Farmworkers from afar: Results from an international study of seasonal farmworkers from Mexico and the Caribbean working on Ontario farms. Ottawa: The North-South Institute, 2006.

- Goldring, Luin, Carolina Berinstein, and Judith Bernhard. “Institutionalizing precarious immigration status in Canada.” Toronto: CERLAC, 2007.

- Griffith, David. American Guestworkers: Jamaicans and Mexicans in the US Labor Market. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2006.

- Griffith, David. The Canadian and United States Migrant Agricultural Workers Programs: Parallels and Divergence Between Two North American Seasonal Migrant Agricultural Labour Markets with respect to “Best Practices.” Ottawa: The North-South Institute.November 2003

- Hall, Dave. “Influx of refugees drops off.” Windsor Star 13 September 2008. The Windsor Star. 9 August 2011 http://www.thestar.com

- Hernández Navarro, Luis. “Mexican Commission Probes Treatment of Guatemalan Guestworkers.” Frontera Norte-Sur Online 27 February 2008.

- Herold, David M., Narayanan Jayaraman, and C.R. Narayanaswamy. “What is the relationship between organizational slack and innovation?” Journal of Managerial Issues, 18.3 (September 2006.)

- Herrera Ruiz, Sandra. “Trabajadores Agrícolas Temporales en la Frontera Guatemala–México.” Tercera Conferencia Internacional Población del Istmo Centroamericano. Costa Rica, 2003.

- Hoefer, Michael, Nancy Rytina, and Bryan Baker. “Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2008.” Population Estimates, February 2009.

- HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). HRSA Geospatial Data Warehouse. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/ Washington, DC: 2007.

- International Organization for Migration; Ministry of Labor and Social Provision(IOM). Guatemala Temporary Migrant Workers to Mexico. Guatemala: International Organization for Migration; Ministry of Labor and Social Provision, 2003

- Juozapavicius, Justin. “Ley causa éxodo de inmigrantes.” La Opinion 27 January 2008.

- Laws, Margaret. Foundation Approaches to US–Mexico Border and Binational Health Funding. http://www.healthaffairs.org/ Health Affairs: 2002.

- Lazos. "Entran en vigor reformas a la Ley General de Poblacion." Boletin , July 21, 2008.

- Lune, Howard. Urban Action Network: HIV/AIDS and Community Organizing in New York City. Boulder, Co: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

- Mahon, Rianne, and Laura Macdonald. “Poverty Policy and Politics in Canada and Mexico: ‘Inclusive’ Liberalism?” International Studies Association Meeting. Chicago, 2007.

- McKinley, Jesse. “San Francisco Reaches out to Immigrants.” The New York Times 6 April 2008. New York Times. 9 August 2011. http://www.nytimes.com

- McLaughlin, Janet. “Falling through the Cracks: Seasonal Foreign Farm Workers; Health and Compensation across Borders.” The IAVGO Reporting Service 21.1 (2007).:1-18.

- McLaughlin, Janet. “Gender, Health and Mobility: Health Concerns of Women Migrant Farmworkers in Canada.” FOCALPoint: Canada’s Spotlight on the Americas 7.9 (December 2008): 10-11

- NCSL (National Conference of State Legislators). 2006 State Legislation Related to Immigration: Enacted, Vetoed, and Pending Gubernatorial Action. NCSL Immigrant Policy Project, 2006.

- NCSL (National Conference of State Legislators). 2007 Enacted State Legislation Related to Immigrants and Immigration. NCSL Immigrant Policy Project, 2008.

- Needle, R. H., R. T. Trotter, et al. “Rapid Assessment of the HIV/AIDS Crisis in Racial and Ethnic Minority Communities: An Approach for Timely Community Interventions.” American Journal of Public Health 93.6 (2003): 970–79.No One is Illegal. No One is Illegal: Toronto Statement on the Auditor General’s Report and SDR Distribution Raid. Toronto: 2008.

- Needle, R. H., R. T. Trotter, et al. “Immigration Raids and Mass Detentions Come to Canada.” Pacific Free Press 4 April 2009.

- Needle, R. H., R. T. Trotter, et al. “Police Continue to do Immigration Enforcement’s Dirty Work.” http://www.nooneisillegal.org/ 4 December 2008.

- Needle, R. H., R. T. Trotter, et al. “What is a Sanctuary City?” http://www.nooneisillegal.org/ 4 December 2008.

- Office of Immigration Statistics. Temporary Admissions of Nonimmigrants to the United States: 2006. Washington DC: Office of Homeland Security, 2006.

- Office of Immigration Statistics. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2007. Washington DC: Office of Homeland Security, 2007.

- Park, Jacob. “Unbundling Globalization: Agent of Policy Convergence?” International Studies Review 4.1 (2002):230-233.

- Petrich, Blanche. “Trabajadores temporales viven en pésimas condiciones.” La Jornada 1 October 2005.

- Pew Hispanic Center. The State of American Public Opinion on Immigration in Spring 2006: A Review of Major Surveys. Washington DC: 2006.

- Pinkerton, James. “Immigrants flock to Texas amid crackdowns.” Houston Chronicle 4 February 2008. Houston Chronicle. 9 August 2011. http://www.chron.com

- Preibisch, Kerry. Patterns of Social Exclusions and Inclusion of Migrant Workers in Rural Canada. The North South Institute: Ottawa, 2007.

- Progressive States Network. The Anti-Immigrant Movement that Failed: Positive Integration Policies by State Governments Still Far Outweigh Punitive Policies Aimed at New Immigrants. New York: 2008.

- Shepard-Durni, Suzana. “The other southern border: Mexico–Guatemala.” Spero News 12 September 2008. Spero News. 9 August 2011. http://www.speroforum.com

- Sohnen, Eleanor. Scratching the Surface of Social Protection for Migrants. Ottawa: FOCAL, 2008.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. Climate of Fear: Latino Immigrants in Suffolk County NY. Montgomery, Alabama: 2009.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. Close to Slavery: Guestworker Programs in the United States. Montgomery, Alabama: 2007.

- SRE. Iniciativas de Ley y Acciones Pro Inmigrantes. Mexico City: 2007.

- Tobar, Hector. “A sanctuary for immigrants in Mexico: The mayor of Ecatepec says those on their way north illegally are safe and welcome in his city.” Los Angeles Times 31 January 2008.Los Angeles Times. 9 August 2011. http://www.latimes.com

- Instituto Nacional de Migracion of Mexico (INM) “Trabajadores Migratorios Temporales en la Frontera Sur de México.” Boletín Informativo 2 (October 2005) INM. 9 August 2011. http://www.inm.gob.mx/index.php/page/Boletin_2_Tercer_Foro

- Trejo García, Elma del Carmen, and Margarita Álvarez Romero. Programa de Trabajadores Agrícolas Temporales México–Canada PTAT. Mexico, DF: Cámara de Diputados LX legislatura, 2007.

- US Citizenship and Immigration Services. USCIS Proposes Streamlining Procedures for the H-2B Program. Washington, DC: 2008.

- Waldie, Paul, Alan Freeman, and Tara Perkins. “Windsor braces for refugee tide.” Globe and Mail 22 September 2007. The Globe and Mail. 9 August 2011. http://www.theglobeandmail.com

- Waller, Michael. Mexico’s Glass House: How the Mexican Constitutions Treats Foreigners. Washington, DC: Center for Security Policy, 2006.

- Watson, Julie. “Legisladores proponen despenalizar inmigración ilegal en México.” LosTiempos.com 21 July 2006.

- Wedemeyer, Jacob. “Of Policies, Procedures and Packing Sheds: Agricultural Incidents of Employer Abuse of the H-2B Nonagricultural Guestworker Visa.” The Journal of Gender, Race and Justice 10.1 (2006):143-192.

- Yin, R. K. Case-Study Research: Design and Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 2003.

List of tables

Table 1

Framework—Substantive and Procedural Aspects of Health Policy Convergence

Table 2

Legal, Temporary, and Undocumented Immigrants in Canada, the US, and Mexico

Table 3a

Framework for Assessing Health Policy Convergence—SOCIETAL LEVEL

Table 3b

Framework for Assessing Health Policy Convergence—POLITICAL LEVEL

Table 3c

Substantive and Procedural Framework for Assessing Health Policy Convergence—TECHNICAL (ENFORCER/PROVIDER) LEVEL