Abstracts

Abstract

We often think of surveillance as ubiquitous, secretive, top-down, corporate, and governmental—and in many ways, it is. Through three vignettes, this essay prods at the ways in which our everyday tools, technologies, and gestures extend surveillance’s reach into our intimate lives and relationships. Each vignette is a story constructed from facts gleaned in news stories, social media, or personal conversations. As such, these vignettes are neither empirical nor entirely speculative. In an effort to consider surveillance as an ongoing and daily activity, they invite readers into more intimate contexts than those that are usually the object of rigorous scholarly analysis. In their intimacy, these stories serve to remind us of the ways in which communication devices are always, in some capacity, tracking and trailing our desires.

Vignette 1 tells the story of the NSA agent who uses the agency’s powerful database to spy on an ex-lover. Vignette 2 explores the kinds of information users can get (about themselves) from Big Tech companies, from social media and dating apps. Vignette 3 looks at Internet cookies and their capacity to make unlikely—and unwanted—introductions. Technology, apps, and our always-on devices complicate the boundaries of intimacy and often work to redefine the trajectories of our desire in the process. The breaches of trust detailed in these stories expose the ways in which Big Tech’s desire to predict and to measure human emotion and behaviour exists in tension with our memories, our secrets, and our wild imaginations.

Résumé

On s’imagine souvent que la surveillance se fait au sommet, qu’elle est omniprésente, secrète, gouvernementale et restreinte à un petit nombre d’initiés. Et de bien des manières, c’est effectivement le cas. En s’appuyant sur trois vignettes, cet essai pointe du doigt la façon dont nos petits gestes quotidiens, nos outils et nos technologies rendent notre intimité et nos relations personnelles accessibles à la surveillance. Chaque vignette est une histoire construite à partir d’informations récoltées dans les nouvelles, sur les réseaux sociaux ou dans des conversations privées. De ce fait, elles ne sont ni empiriques ni tout à fait spéculatives. Les lecteurs sont placés dans un contexte plus intime que celui auquel ils sont habituellement confrontés dans le cadre d’analyses universitaires plus rigoureuses, et cela, dans le but de souligner le caractère banal et quotidien de la surveillance. Ces histoires, par leur intimisme, nous rappellent de quelles manières nos outils de communication servent, dans une certaine mesure, à repérer et à faire le suivi de nos désirs.

La vignette 1 nous raconte l’histoire d’un agent de la NSA se servant de la base de données de cette puissante organisation pour espionner son ex. La vignette 2 donne un aperçu des différentes informations accessibles à un utilisateur (informations le concernant lui-même) à partir d’une grande entreprise technologique, des réseaux sociaux aux applications de rencontre. La vignette 3 se penche sur les cookies Internet et leur capacité de présenter un utilisateur de façons inattendues — et indésirables. Les ruptures de confiance exposées par ces histoires soulignent la volonté qu’ont les grandes sociétés technologiques de pouvoir prédire et mesurer les émotions et comportements humains, et le fait que cette volonté entre en tension avec nos souvenirs, nos secrets et nos fantasmes.

Article body

Vignette 1: LOVEINT

- Quentin Hardy @qhardy[1]Met her, date her,

Not much later,

She finds out what I meant

'bout keeping her content.

#NSAlovepoems

Fig. 1

Access to the world’s largest database lets him search for secrets about his ex-girlfriend. And later, the polygraph test makes him admit that he’s done it. It’s always the machine that’s to blame—first for the uncontrollable urge to know, and then for the unbearable guilt of knowing.

Weeks after his search, when he fails the lie detector test necessary to renew his security clearance, he cites an overwhelming “curiosity” to explain his lack of self-control.[2] He never considers himself at fault for querying the database because that’s what he does for a living: as an analyst for the National Security Agency (NSA), he has been trained to spy. And part of this training means becoming immune to the impacts of spying—and, it would seem, immune to the consequences of breaching another person’s privacy. It means not feeling the breach as a breach. To him, it’s just a query. Just a way to get more information—to confirm a suspicion, to gather more data, to finish a conversation. To become an analyst, after all, he had merged with a system that normalizes these kinds of searches, that frames data as merely data: dry, neutral, and devoid of meaning until aggregated or triangulated into a larger pattern.

The phone records and the metadata he tapped into to spy on his ex-girlfriend were deemed insignificant by most employees at the Agency. Indeed, eleven other NSA agents would later be caught committing similar transgressions; like him, these agents suffered few professional consequences. Internally, the incidents did not constitute a scandal either. Of the eleven known cases of NSA employees breaching the boundaries between work and pleasure that have surfaced since 2013, eight involved snooping on current or past lovers or spouses during the last decade.[3] Five employees quit before being disciplined. The rest received letters of reprimand or short suspensions without pay. Few dropped in rank; when they did, the demotion smacked of symbolism rather than a genuine punishment.

While unfettered access to their present and past lovers’ personal details proved too tantalizing for these eleven employees to resist, the data involved in these cases represents just the tiniest fraction of 1.7 billion communications intercepted by the NSA every day.[4] NSA programs such as PRISM and XKeyscore[5] give analysts open access to American citizens’ private information. It remains unclear to the public what the parameters of use are or how (or if) these are policed internally at the Agency. The network’s reach is huge and tentacular; and because of how metadata is gathered, spying on an ex is spying on their entire network, too.

So what does “curiosity” mean in this context, beyond being enough to justify breaching the privacy of one’s intimate partner(s)? What about privacy, or intimacy, itself? As he queried her data, was he hoping that he could (finally) know her––the real her, the secret her? Was he thinking that he could finally know what she’d kept from him, cross-reference the many versions of the stories she’d told, fill in the interruptions, defragment the threads, and be privy to the details of her private conversations with others, too? Does he feel entitled to these details—not only as an NSA employee, but also as her ex-boyfriend? Primed for surveillance at this scale, does he reason that true intimacy means knowing everything? Do the lines between analyst and lover blur further—does he believe that this, too, is for her safety, for her protection?

Compared to the analyst’s unfettered access to her innermost self, why would he settle for the lover’s partial truths? We cannot know definitive answers to these questions, but we can see how his role at the NSA would facilitate any effort at omniscience. Nobody can know what his motives were, but his actions illustrate the ways in which surveillance is antithetical to intimacy. Maybe he imagined that his training qualified him to keep her data in check. Maybe that training taught him to think of relationships as something to be managed numerically, rationally, analytically: objectively. Maybe he became an NSA employee in order to gain this kind of privileged access to other people’s data—or, perhaps this privileged access is what thwarted his ability to think ethically and empathetically. Or perhaps it’s impossible to resist such a God-like, fly-like, ghost-like viewpoint. Perhaps surveillance is antithetical to intimacy because the data surveillance gathers comprises the deep uncertainties and blind trust that constitute intimacy. Or perhaps surveillance is yet another tentacle extension of the privilege white men afford themselves by building these infrastructures in the first place. Surveillance as insecurity.

As the scandal of NSA agents spying on lovers past and present broke in 2013, the news media acknowledged that the case—known as LOVEINT—was at least potentially troubling. Part of LOVEINT’s power to disturb, they suggested, was that some people could too easily relate to the often violent and controlling desire to breach trust—to seek out truths that are not easily available, and perhaps not meant for us to uncover. Given the chance, however, how many others would do the same as these NSA employees? How many of us do, in fact, do something similar with the means that we have, by checking a lover’s email or phone sub rosa? How many of us spy on each other by way of bureaucratic paperwork or devices that reveal traces of each other’s digital routines? Isn’t social media largely built for legitimated forms of self-tracking and for “following” others? The language certainly has a stalkerish ring to it. And if it becomes increasingly difficult for us to distinguish between a quick flip through a lover’s phone and mass data theft, perhaps we understand that intimacy is a more crucial component—and motive—of surveillance than so far made explicit in our technosocial imaginaries.

Vignette 2: Love Handles

It knows the real, inglorious version of me who copy-pasted the same joke to match 567, 568, and 569; who exchanged compulsively with 16 different people simultaneously one New Year’s Day, and then ghosted 16 of them.

- Judith Duportail[6]

Fig. 2

It’s a lot of information.[7] When the two of them look at the hard copies they requested, they realize that everything they’ve done online, however fleeting it might have seemed in the moment, amounts to tomes in print. In paper format, it takes on the weight of accumulated evidence. The tally for her is 800 pages from Tinder, a popular dating app; for him, a 1,200-page PDF from Facebook.[8] While two people don’t make a trend, they can make a point—about how Big Tech handles intimacies, with little regard paid to its users’ privacy or intimate lives. She’s a journalist; he’s a privacy activist. The two of them share an interest in user privacy in the context of the EU data protection law at a moment when Big Tech—especially social media companies—are trying their hand at surveilling users.[9]

First: the journalist

She orders her personal data from Tinder, and the company delivers her an 800-page report that details things she’d mostly forgotten regarding her various flirtations, desires, and fears. Embarrassed, she flips through the pages that speak back to her age, education, interests, and tastes. Recorded in these pages are also incredible volumes of information about her whereabouts, habits, proclivities—all things that emerge from patterns in the aggregate data. This is all data she’d willfully shared through the app itself for the purposes of dating. But the guilt and shame she later feels is evidence that you can in fact surprise yourself—not just by encountering a constellation of interpersonal communications that wouldn’t otherwise be read in relation to each other, but also when a company report confronts you with intimate patterns about yourself that you weren’t aware they were even collecting.

Tinder knows her in ways she doesn’t know herself because while she’s forgotten almost all of her 1,700 Tinder interactions, the app hasn’t, and won’t. Her ability to forget is what has allowed her to move on, to grow, to like new things without having to trace the many trajectories that informed those choices—without having to consider whether they were guided by moments of solitude, longing, boredom, sleepless nights, impulses, rejection, or the restlessness of too much quiet. The more she used the app, the more refined it became. In information technology studies, aggregated data generates what’s called “secondary implicit disclosed information.”[10] This just means that the app generates new data from patterns in the data volunteered by its users. And because Tinder has 50 million users, her data is cross-referenced with many others, which in turn reveals more about everyone using the app, as a group, than it does about each individual.

Tinder doesn’t hide the fact that it collects data on its users. They also reserve the right to sell it, trade it, or repurpose it. Tinder is made for matchmaking and most of its users are more preoccupied with finding lustful connections than with how their data might not be as safe, secure, or private as it feels within the framework of the app. That was true for her until she heard that the app’s algorithm produced a “desirability score” for all its users.[11] Tinder’s internal rating is called “the Elo Score” (a chess concept, referring to ability levels) and the app privately determines all of its users’ desirability score (which is not based, as one might expect, exclusively on the number of right and left “swipes” by others).[12] In turn, this score informs who you are likely to match with and thus to date, placing people in categories based on secret algorithmically generated criteria controlled by Tinder. She knows that her ratings limit her pool to people “in her own category.”[13] The more you match with people deemed highly desirable by Tinder, however, the more desirable you become. The app literalizes and reinforces the idea that people should date others in their “league” through algorithmic wizardry that quantifies the unquantifiable.

Second: the law student and privacy

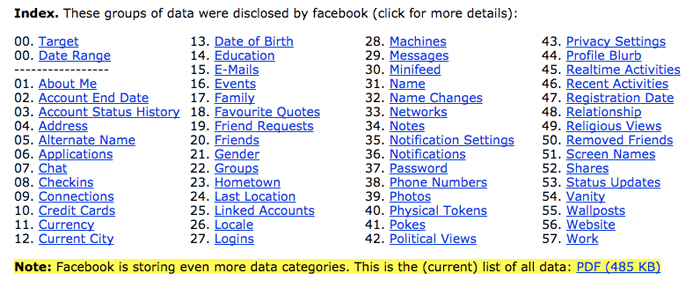

Facebook also gathers data on its users. Given that one of its data centres is in Ireland and services the site’s European clientele, it is subject to different laws than in the US. There, the “right to access” entitles Europeans to know what a company knows about them. So when he ordered his Facebook details from the company, Facebook had no choice but to comply. They sent him a 1,200-page PDF outlining his clicks, likes, and pokes. He was only on Facebook for three years when the request was made, but the complexities of the data astound and worry him. As a privacy activist and a lawyer, he has since posted the contents and an analysis online, revealing the kinds of categories that Facebook is collecting, or willing to admit it’s collecting:

Fig. 3

Data categories collected by Facebook. Max Schrems, “Facebook’s Data Pool,” Europe Versus Facebook, http://europe-v-facebook.org/EN/Data_Pool/data_pool.html (accessed 16 May 2018).

The lawyer wasn’t privy to his own biometric faceprint (considered a trade secret); presumably, the company leaves out other such experiments, which it too considers to be secondary information, a calculated byproduct of its magnificent algorithms. But he keeps pushing and challenging the legal system, insisting that a precedent not be set for companies like Facebook to act above the law. Above all, he wants to break the persistent myth circulated by the industry that nobody cares about their privacy on social media sites.[14] Mass, indiscriminate surveillance has quickly been normalized in data-driven industries—where storage becomes a fortress for ideals that see and support Big Tech as knowing best and caring for its users’ well-being.[15]

Vignette 3: Algorithmic Cookies

The Heart Goes Last, Margaret Atwood[16]“No, it isn’t,” Charmaine insists. “Love isn’t like that.

With love, you can’t stop yourself.” -

Fig. 4

“Do you know who this is?” she asks her new boyfriend with sincere bewilderment. She looks closely at the stranger’s face that Facebook has suggested to her as a possible connection: she is a blond woman in her late twenties. “Who is this?” she asks again, pointing to the blonde woman on her phone. The BF barely looks up. He works up a shrug, and says, “I think we hung out a few years ago, I don’t really know…” He keeps eating his cereal, unfazed, as few would be in this situation. Doesn’t he want to know why? Or, how she’s gotten around to asking him about an obscure ex? Nope.

Later, they are driving together. The GPS offers rerouting after rerouting as they make a detour to the liquor store on their way to a party in the suburbs. Time stops as she swipes off the mapping app, revealing a series of texts below. He snatches the phone away. She recognizes the Facebook woman’s name. It’s on his phone. They are driving. The boyfriend keeps his eyes on the road. They both remain silent.

We know where this is headed. But why deny knowing her in the first place? What had become normal for him here? Why couldn’t he speak of their relationship openly? And how had their networks become so entangled?

In the weeks to follow, she creates a series of fake dating accounts to match with his to see which online dating sites he was using (there were five; all of them very active). She confronts him and he lies again. Later still, while he is in the shower, she goes through his entire contact list and reads all of his texts. What she discovered was that he’d kept up conversations with a dozen or so women, recounting specific details of their personal lives in a way that created and maintained intimacies. He often asked them for sexy photos, which he’d just as often receive. When confronted about these conversations, though, he shows no remorse. He just says, “I don’t see the problem. It’s just virtual stuff.”

The line of what counts as “real” emotional contact and what counts as “virtual” flirtation is not for any one person to determine. What is at play here, however, is more significant than ongoing debates about what counts as “cheating.” These are often moral lines in the sand. Online communication has, however, created new ways to connect people; increasingly, it does so using algorithms programmed from a particular moral standpoint. Constantly managing how we are being tracked by our own devices can and will have huge effects on how we socialize and form connections offline.[17]

LinkedIn and Facebook, two of the most popular social networking sites for work and leisure, constantly recommend new connections in an effort to increase your (their) network. LinkedIn offers a sidebar of “People You May Know”; so does Facebook.[18] But how does the platform know who you should know?[19] Officially, it looks for commonalities between members, and shared connections in terms of employment, education, and experience (algorithmically defined). It also draws from cookies[20] and contacts imported from users’ address books. The rhizomatic nature of the platform’s growth renders the always-new web of connections almost too vast, as if to confuse and convince its users that it isn’t pulling from things like email, geolocation data, Facebook, or dating apps. But it is. While you might limit your privacy settings and turn off location services, these conscientious choices can be overridden by just one of your contacts offering LinkedIn access to their contacts. Facebook operates in a similar way.[21] Even if you change your phone number or email address, your friend network will reconnect you, insert you back into the social media sphere. Location services will out you based on proximity to another person.[22] And, increasingly, deep-learning facial recognition algorithms (Microsoft Face API, Facebook’s Facial Recognition App, Amazon Rekognition) are starting to do the work of profiling and connecting people, too. For example, Facebook makes a “template” of your face by using “a string of numbers” that is unique to you.[23] It then uses this data to match you and others in relation to you. The examples have become endless—and normal—and less startling to many as a result. In this story the couple is doomed to understand itself within the trappings of white heteronormative society and have this simultaneously be disrupted and reinforced by the impulsive affordances and addictive features of social media.

Surveillance structures intimacy in the present moment, and does so by normalizing and compartmentalizing it, and flattening desire along the way. This is important in the bigger picture of surveillance studies because too often concerns over privacy are not explored in terms of how they change our lives in profound ways—we all need secrets and the space to explore our multitudes.

Appendices

Biographical note

Mél Hogan is an Assistant Professor (Environmental Media) in the Communication, Media and Film (CMF) Department at the University of Calgary. She is slowly writing a book about genomic media. Leading up to this, her research has been mainly on data storage—from server farms to DNA—with a focus on surveillance-biocapitalism. Her work has been published in journals like Ephemera, First Monday, and Big Data and Society, and she has co-edited special journal issues about media infrastructure in Culture Machine (with Asta Vonderau) and Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies (2017, with Alix Johnson). She is the Canadian Communication Association Board Secretary, a founding co-member of the “Genomics, Bioinformatics, and the Climate Crisis” working group at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Humanities (Calgary), and was recently awarded a SSHRC Insight Development Grant entitled “Storing Genomic Data: New Media-Historical Contexts for Coding Life.”

Notes

-

[1]

Tweeted by Quentin Hardy (verified account), https://twitter.com/qhardy/status/371415789955338241?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[2]

Edward Moyer, “NSA Offers Details on ‘LOVEINT’ (That’s Spying on Lovers, Exes),” C|net, 27 September 2013, http://www.cnet.com/news/nsa-offers-details-on-loveint-thats-spying-on-lovers-exes/ (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[3]

Charles E. Grassley, “Grassley: Americans Deserve Accountability from the Department of Justice on NSA Surveillance Abuses,” Chuck Grassley’s Website, 2 February 2015, https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-americans-deserve-accountability-department-justice-nsa-surveillance (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[4]

Ryan Gallagher, “How NSA Spies Abused Their Powers to Snoop on Girlfriends, Lovers, and First Dates,” Slate, 27 September 2013. https://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2013/09/27/loveint_how_nsa_spies_snooped_on_girlfriends_lovers_and_first_dates.html (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[5]

Glenn Greenwald, “XKeyscore: NSA tool collects 'nearly everything a user does on the internet,” The Guardian, 31 July 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/31/nsa-top-secret-program-online-data (accessed 19 November 2018).

-

[6]

Judith Duportail, “I Asked Tinder for My Data. It Sent Me 800 Pages of My Deepest, Darkest Secrets,” The Guardian, 26 September 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/sep/26/tinder-personal-data-dating-app-messages-hacked-sold?CMP=share_btn_tw (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[7]

Austin Carr, “I Found Out My Secret Internal Tinder Rating And Now I Wish I Hadn’t,” Fast Company, 11 January 2016. https://www.fastcompany.com/3054871/whats-your-tinder-score-inside-the-apps-internal-ranking-system (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[8]

Kashmir Hill, “Max Schrems: The Austrian Thorn in Facebook’s Side,” Forbes.com, 7 February 2012, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2012/02/07/the-austrian-thorn-in-facebooks-side/#243d6f3b7b0b (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[9]

Spencer Soper, “This Is How Alexa Can Record Private Conversations,” Bloomberg, 24 May 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-24/amazon-s-alexa-eavesdropped-and-shared-the-conversation-report (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[10]

Duportail, 2017.

-

[11]

“Tinder Desirability Score,” PersonalData.io, https://personaldata.io/2017/05/02/tinder/ (accessed 16 May 2018) .

-

[12]

Maya Kosoff, “You Have a Secret Tinder Rating—but Only the Company Can See What It Is,” Business Insider, 11 January 2016 http://www.businessinsider.com/secret-tinder-rating-system-called-elo-score-can-only-be-seen-by-company-2016-1?op=1 (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[13]

“Fat Girl Tinder Date (Social Experiment),” Simple Pickup, 24 September 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2alnVIj1Jf8&feature=youtu.be (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[14]

Samuel Gibbs, “Max Schrems Facebook Privacy Complaint to Be Investigated in Ireland,” The Guardian, 20 October 2015 https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/oct/20/max-schrems-facebook-privacy-ireland-investigation (accessed 16 May 2018).

-

[15]

Mél Hogan, “Sweaty Zuckerberg and Cool Computing,” The California Review of Images and Mark Zuckerberg, Volume One, Winter 2017, http://zuckerbergreview.com/hogan.html (accessed 6 June 2018)

-

[16]

Margaret Atwood, The Heart Goes Last: A Novel, [2015], New York/Toronto, Anchor Books, Reprint edition, 2016, p. 63

-

[17]

See Eric Johnson, “Your Phone Is Not Secretly Spying On Your Conversations. It Doesn’t Need To.” Recode, 20 July 2018, https://www.recode.net/2018/7/20/17594074/phone-spying-wiretap-microphone-smartphone-northeastern-dave-choffnes-christo-wilson-kara-swisher (accessed 13 November 2018); Kashmir Hill, “These Academics Spent the Last Year Testing Whether Your Phone Is Secretly Listening to You,” Gizmodo, 3 July 2018, https://gizmodo.com/these-academics-spent-the-last-year-testing-whether-you-1826961188 (accessed 13 November 2018); Amit Chowdhry, “Facebook Reiterates That It Does Not Listen To Conversations through Your Phone for Ad Targeting,” Forbes.com, 31 October 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/amitchowdhry/2017/10/31/facebook-ads-microphone/-2b258751534d (accessed 30 October 2018).

-

[18]

“People You May Know Feature – Overview,” LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/29?lang=en (accessed 8 June 2018).

-

[19]

David Veldt, “LINKEDIN: THE CREEPIEST SOCIAL NETWORK,” Interactually, 9 May 2013

http://www.interactually.com/linkedin-creepiest-social-network/ (accessed 8 June 2018).

-

[20]

“HTTP cookie,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HTTP_cookie (accessed 8 June 2018).

-

[21]

“Facebook ‘Suggested Friends’ Is Creepier Than I Ever Could Have Imagined,” Reddit, posted by u/creepyeyes, 11 July 2015, https://www.reddit.com/r/OkCupid/comments/3cy24i/facebook_suggested_friends_is_creepier_than_i/ (accessed 8 June 2018).

-

[22]

David Auerbach, “Facebook Just Suggested I Friend My Landlord. Does That Mean He’s Been Cyberstalking Me?,” Slate, 23 October 2015, https://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2015/10/why_did_facebook_suggest_i_friend_my_ex.html (accessed 8 June 2018).

-

[23]

Sidney Fussell, “Facebook’s New Face Recognition Features: What We Do (and Don’t) Know [Updated]” Gizmodo, 27 February 2018, https://gizmodo.com/facebooks-new-face-recognition-features-what-we-do-an-1823359911 (accessed 29 June 2018).

List of figures

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Data categories collected by Facebook. Max Schrems, “Facebook’s Data Pool,” Europe Versus Facebook, http://europe-v-facebook.org/EN/Data_Pool/data_pool.html (accessed 16 May 2018).

Fig. 4