Abstracts

Abstract

During the mid-to-late nineteenth century, the American Civil War, Canadian Confederation, transnational violence, and rising concerns over undesirable immigration increased anxieties in Canada and the United States over the permeability of their shared border. Both countries turned to a combination of direct and indirect control to assert their authority and police movement across the line. Direct control utilized military units, police officers, customs officials, and border guards to restrict movement by stopping individuals at the border itself. This approach had minimal success in limiting the movement of groups such as the Coast Salish, Lakota, Dakota, and Cree. In response, both countries employed indirect border-control strategies that attacked the motivations for crossing the border instead of its physical manifestation. They used rations, annuities, extra-legal evictions, and reserve land to impose national boundaries onto First Nations communities in the prairies and on the West Coast. The application of this indirect approach differed by region, by tribe, and by community leading to a ragged set of borderland policies that remained in flux throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Résumé

À la fin du XIXe siècle, la guerre de Sécession, la confédération canadienne, la violence transnationale et les préoccupations grandissantes entourant l’immigration indésirable ont exacerbé les craintes au Canada et aux États-Unis à l’égard de la perméabilité de leur frontière commune. Les deux pays ont mis en place une série de contrôles directs et indirects pour marquer leur autorité et pour surveiller les mouvements transfrontaliers. Le contrôle direct a misé sur des unités militaires, des agents de police, des douaniers et des gardes-frontières pour restreindre les déplacements en stoppant les personnes à la frontière. Cette méthode a connu un succès mitigé pour limiter la circulation de groupes tels les Salishs du littoral, les Lakotas, les Dakotas et les Cris. En réaction, les deux pays ont usé de stratégies indirectes de contrôle qui se sont attaquées aux motifs de traverser la frontière plutôt qu’aux passages proprement dits. Ils ont eu recours à des rations, à des rentes, à des expulsions extrajudiciaires et aux terres de réserve pour imposer une frontière nationale aux communautés des Premières Nations des Prairies et de la côte Ouest. L’application de ces stratégies a varié selon la région, la tribu et la communauté, ce qui a mené à une courtepointe de politiques frontalières qui ont continué à évoluer pour le reste du XIXe siècle et le début du XXe siècle.

Article body

During the nineteenth century, Canada and the United States embarked on nation building campaigns aimed at delineating their shared border and expanding control over their respective territories. To do so they adopted a series of direct and indirect border-control strategies. Direct control focused on monitoring and influencing the ways that individuals physically crossed the border itself. North-West Mounted Police officers, border guards, immigration and customs agents, fishery patrols, provincial police forces, and naval units all contributed to this policing. Historical and contemporary accounts of border control often focused on this naked form of coercion, as it represented one of the most visible ways that federal governments intervened in daily life.[1]

Direct control, for all its significance, suffered from systemic limitations particularly when applied to Native American communities. In 1885, for example, A.W. Bash, a collector of customs in Washington Territory, noted that he had less than two dozen men responsible for a district of “some 350 miles and a coast line of not less than 1000, and including islands 2000 miles to guard.”[2] His twenty-odd men, already overburdened, kept no record of the nationality of travellers entering their district. They failed to stop smugglers and all but ignored First Nations who crossed the line. The extensive challenges Bash encountered while enforcing national borders were not unique to the West Coast nor to customs officials.[3]

Army units, Indian agents, North West Mounted Police officers, and fishery patrols all complained about the inadequate appropriations, insufficient personnel, and the extensive borderland they were forced to contend with. Canada’s small economy created additional impediments for its border-control strategies by limiting its federal presence to little more than a skeleton force in many regions and by making military actions, a crucial feature of American Indian policy, prohibitively expensive. The economic, demographic, and military superiority the United States maintained over Canada gave it additional options for how it policed movement, but it still struggled to control an often uncooperative borderland population. Faced with insufficient administrators, troops, and agents, both nations stationed men at areas of heavy traffic and left most of the border undefended. The difficulties of enforcement created room for transnational movement, local variation, misunderstandings, and corruption.

The difficulties Canada and the United States experienced while trying to patrol such an extensive border led them to adopt indirect strategies of enforcement, which attacked the motivations for crossing the border rather than simply their physical manifestation. Although this kind of control has received less sustained attention by historians, it was nonetheless essential to extending federal authority throughout the borderland. Indirect control relied on limiting incentives for movement by restricting access to resources and labour markets. This approach required fewer personnel and allowed agents stationed off the 49th parallel to contribute towards border-control policies.

Indirect control came with a distinct set of limitations and was often used to supplement rather than supplant direct control attempts. Controlling the motivations for border crossing worked best when applied at the community and tribal levels and proved inconsistent and ineffective in controlling small-scale movements of individuals and families. Nor could indirect control be applied in a uniform fashion. Dependency, which amplified the effectiveness of indirect control, varied by region and often occurred as the result of a combination of factors over which the federal governments had limited control. The disappearance of the buffalo, changing labour markets, intertribal conflicts, and demographic shifts all played an important role. This left both governments with the ability to exploit situational opportunities but prohibited them from imposing consistent and effective indirect border controls at a national scale.[4]

Although indirect control was exercised against all ethnic groups, it was most significant with respect to Native Americans because of their unique legal status within each country and because of the relative inability of either country to control First Nations’ movements through checkpoints. Native American knowledge of local geography, the expansiveness of their familial ties, and their ability to slip past federal patrols made enforcing the border at the physical line more often than not a lesson in futility. At the same time the economic, legal, racial, and political status of Native Americans in the United States and Canada made them particularly vulnerable to the meddling of Indian Affairs agents, army units, land surveyors, and treaty commissioners. Relying on vulnerabilities, however, meant that the ability of both governments to exercise indirect control varied by region, tribe, and community. As a result, the strategies that worked on the prairies could not be translated to the Pacific coast without significant modifications, creating a ragged and inconsistent set of borderland controls that remained in flux throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Indirect Control in the Prairies

The disappearance of buffalo, which began during the 1860s and 1870s, tore away at the independence of Indigenous groups on the northern plains. By the early 1880s, the buffalo had all but disappeared. Native American groups responded to the buffalo’s destruction in a variety of ways, including selling land in exchange for rations and annuities and engaging in wage labour. In each case, however, the new economic strategies did little to recreate the same level of independence First Nations groups had maintained prior to the buffalo’s destruction, giving Canada and the United States greater ability to interfere in the daily lives of plains Indians. Canadian and American Indian agents, for example, began using Indian status, rations, and treaty payments as leverage to threaten and punish First Nations who violated the sanctity of national spaces.[5]

Both countries perceived the transnational movements of Native Americans as a financial liability, a diplomatic risk, a challenge to their sovereignty, and a disruption to their Indian policies. The two governments did not, however, view all forms of transnational mobility with equal apprehension. Canada and the United States understood Blackfoot mobility, for example, to be an annoyance rather than a crisis because the Blackfoot remained peaceful. In contrast, they viewed the movements of the Dakota, Lakota, Nez Perce, Métis, and Cree, who resisted federal authority through a combination of warfare and mobility, to be direct affronts to their power.[6]

Persistent violence made the permeability of the border harder to ignore and provided strong impetus for new border policies. During the early 1860s, for example, mounting conflicts between the Dakota and the United States government created ample concern over border control. The Dakota had ceded parts of Minnesota, Iowa, and the Dakotas to the United States in 1815, 1836–1837, and 1851, but pressure for their land remained. The United States’ failure to pay the Dakota the annuities promised under treaty, local traders’ reluctance to supply goods on credit, and skirmishes between settlers and the Dakota fanned discontent. Between 18 and 23 August 1862 the Dakota responded to their long-standing grievances by launching a series of attacks that killed hundreds of settlers and threw the surrounding region into disarray. By late September, the American army had broken Dakota resistance forcing hundreds to flee from Minnesota to the Red River Settlement in British territory or face arrest. Once across the border, the Dakota refugees attempted to transform their past relationships with the British into contemporary support. The refugees produced flags and medals given to them by the British government during the War of 1812 and requested Britain set land aside for them north of the border.

The refugees put Britain in a hard position. Britain lacked the troops necessary to evict the Dakota and the sudden influx of so many people strained the nearby British and Métis communities. After numerous attempts to remove the Dakota from the Dominion’s territory, the government offered the approximately 1,800 Dakota refugees in Canada a permanent reserve under two stipulations. First, Canada maintained that the land being offered was a sign of good faith rather than an obligation on the Canadian government’s part. The Dakota would not be considered treaty Indians and would receive no annuities. Second, American Dakota entering Canada after the treaty would not be recognized as Canadian Indians by the Department of Indian Affairs and would not be given a place on the reserve. Canada attempted to reaffirm the sanctity of the border. Past transgressions could be forgiven, but from this point forward American Sioux were to remain in the United States. Canadian Sioux were to remain in Canada.[7]

Canada became far more reluctant to grant even partial recognition to American Indians who crossed into its jurisdiction by the late nineteenth century. By the 1870s, the Department of Indian Affairs had created complex legal definitions of who qualified as a Canadian Indian, impacting their ability to claim access to land, rations, annuities, and resource gathering sites. The Canadian Indian Act of 1876, for example, ruled that any Indian who resided for “five years continuously” in a foreign country would lose their status “unless the consent of the band with the approval of the Superintendent-General or his agent”[8] was first obtained. Native American mechanics, missionaries, professionals, teachers, and interpreters engaged in their duties were exempt from this restriction. This policy divided sanctioned crossings from illegitimate ones, while leaving the gray areas at the discretion of the Department of Indian Affairs. Over time, Indian agents pushed to have reserves located further from the border, increased their commitment to monitoring cross-border movements, and showed greater reluctance to assist Native American groups fleeing conflict with the United States.[9]

The United States implemented a similar series of indirect border-control measures to limit the benefits First Nations from Canada could reap by crossing into the United States. In 1885, Cree militants participated in an unsuccessful resistance against the Canadian government aimed at pressuring Canada to acknowledge the rights of First Nations and Métis. In the rebellion’s aftermath, Little Bear’s Cree entered the United States seeking sanctuary much like the Dakota had done in the opposite direction two decades earlier. The Cree received a cold welcome on their arrival. Local Indian agents prevented the Cree from residing on the reservations of “American” Indians, and the group struggled to find work in the surrounding towns.

In 1896 the United States Congress appropriated $5,000 to rid the country of Canadian Crees who had claimed refuge in the United States after the rebellion. Montana’s Governor, John E. Rickards, argued that the Cree had violated gaming laws, looted cabins, and interfered with cattle grazing. Ultimately the argument rested on the idea that Canada, not the United States, should be responsible for these troublesome “British” Indians. That the Cree had historic ties to land on both sides of the border was lost in the debate. Between 20 June and 7 August 1896 the United States forced Little Bear, Lucky Man, and over 500 Indians across the line into Canada. The initial round up included American-born Cree, Ojibwa, Gros Ventre, and Assiniboine. Intermarriage and the close association between groups provided some of the confusion. American authorities considered Métis and Cree, for example, to be “Canadian” Indians regardless of their actual birthplace. Congress’ orders assumed clarity of tribal identity, race, and nationality that simply did not exist.[10]

By the turn of the century, most of the so-called Canadian Cree had returned to Montana. Soldiers could evict Indians living in the wrong country, but unless a constant force remained stationed along the line, groups like the Cree could easily re-cross. A.E. Forget, a Canadian Indian Commissioner, wrote to the superintendent general of Indian Affairs “it was not possible to do anything beyond the adoption of persuasive measures, to prevent their [the Cree’s] exodus.”[11] Persuasion, however, could be a powerful weapon. Canada and the United States expended great effort to ensure that only hardship awaited those who violated the national divide.

In 1916 Little Bear’s Cree secured a reservation in the United States with the help of Rocky Boy’s Chippewa, a group with whom they had hunted and travelled in the past. The two groups received a 56,000-acre reservation on the military reserve at Fort Assiniboine over the concerted opposition of land speculators. On the surface, the recognition of Little Bear’s claim to land in the United States suggests the limitations of both direct and indirect border-control strategies. The army had evicted the Cree once but could not stop them from crossing the border at will. Indirect attempts to control the Cree, through the denial of reservation lands, annuities, and legal recognition, had not deterred them from remaining in the United States for decades. The American government had eventually weakened before the Cree’s demands. Little Bear received the recognition he had coveted.

The battle for recognition, however, also revealed just how powerful indirect forms of control had become. The Cree’s desire for land recognition from the United States’ government would have appeared strange earlier in the nineteenth century, when the borders that had mattered had been between Native American groups rather than European ones. Moreover, Little Bear’s success in securing suitable land had taken almost three decades of suffering and precluded his ability to claim land and annuities in Canada. The United States and Canada had succeeded in gutting the benefits of transnational mobility on the plains and increasing its risks. That the Cree were willing to endure such great hardships to secure land is more suggestive of the poor treatment they received at the hands of the Canadian government, than to the ineffectuality of indirect control.[12]

Indirect Control on the Pacific Coast

British, Canadian, and American attempts to control the risks and benefits First Nations gained by crossing the border took a different form on the Pacific Coast than they did on the plains. Local circumstances limited the kinds of coercive measures both governments could use. First Nations maintained control over their subsistence along the coast for longer than they had on the plains, and British and American reliance on Native American labourers on the West Coast limited the kinds of economic sanctions they could impose until the end of the nineteenth century. While British, Canadian, and American authority remained limited, each government attempted to restrict only the kinds of transnational movements they found most troubling and left the vast majority of crossings undisturbed. As the demographic, military, and economic contexts changed along the coast, Britain, Canada, and the United States expanded the ways they interfered with transnational identities attacking the cultural ceremonies, economic opportunities, and familial bonds that spanned national lines. By the twentieth century, they had succeeded in using Indian status and reservation lands as a cudgel with which to enforce the national orderings they had envisioned during the nineteenth century.

Coastal raiding had occurred on the Pacific Coast long before the arrival of Europeans and remained widespread throughout the early nineteenth century. Raiding troubled Britain and the United States because it signified the continued military significance of Native Americans along the coast, disrupted the regional economies in which Indians formed a significant portion of the labour force, and made a mockery of the boundary the two countries had tried to draw. In 1858, J.W. Nesmith, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Oregon and Washington Territories, noted, for example, that large war canoes from British and Russian territories could carry 100 warriors, with a swiftness which rendered “anything but a steamer useless in pursuit” while their “courage, numbers, and skill render them too formidable … [for] an ordinary crew.”[13] When groups of raiders, such as the Okinakanes, were pressured, they could “easily effect their escape into the British possession, where … they cannot be taken except by a tedious extradition process.”[14] In such circumstances, the boundary assisted raiders in avoiding retribution, but did little to protect the coastal communities that they preyed upon. Transnational raiders highlighted the inability of the United States or Britain to protect their own settlers or defend the Coast Salish who had chosen to live on government reservations. Raiders also made it difficult to ignore just how little of a deterrent the border was to First Nation’s mobility.[15]

Britain and the United States also worried about the military forces First Nations could muster, as opposition to treaties mounted and outbreaks of violence appeared imminent. They feared that Indian warfare in one country could drag both countries into a much larger conflict. Colonial administrators, faced with the possibility of dispersed and chronic warfare, began to cooperate across national lines. This cooperation required that colonial administrators collapse conflicts into an “Indian” vs. “white” binary, ignoring the hundreds of competing identities and interests that existed within each group. The binary could not account for why the Duwamish warned Seattle’s residents of an incoming attack by the Nisqually, or why the United States was so concerned about the Hudson’s Bay Company’s connection to Native Americans south of the 49th parallel. That required an understanding of local circumstance. The racial categorizations, however flawed, had a seductive appeal to Britain and the United States. They created a simpler world of racial solidarity in which Britain and the United States worked together to bring civilization to Indians. Conceptualizing the problem in such a fashion allowed colonial administrators to provide military and logistical support to one another, even as they competed over territory such as the San Juan Islands.[16]

By the 1860s Britain and the United States introduced faster ships to their navies, which allowed them to keep up with the speed of the war canoes. At the same time, American military successes along the coast reduced the likelihood of extended military campaigns that spanned national lines. Native American raiding disappeared as a major concern, but the policies Britain and the United States could implement remained limited. When there was no crisis to spur attempts to police the border, the boundary remained open and the national spaces hazy. Britain and the United States had still not found an answer for enforcing the border on a daily basis. Geography, labour shortages, and the limited bureaucracies in both countries encouraged transnational movements and linked settler economies, while restricting the kinds of policies either country could pursue.[17]

The Cascade and Rocky Mountains made it easier to travel between the coastal regions of Washington Territory and British Columbia than to travel between the coast and the interior in either place. As a result, businessmen, labourers, smugglers, and even law enforcement officials near the coast found it easy to develop social, economic, and personal ties that transcended national boundaries and difficult to establish them within a national framework. The Ne-u-lub-vig, Misonks, Cow-e-na-chino, and Noot-hum-mic living in Washington Territory, for example, maintained strong commercial ties to the Hudson’s Bay Company in British territory and weak ones within the United States. By choosing the path of least resistance, people on both sides of the border built regional connections in place of national ones.[18]

The specific labour demands of the canning and hops industries made their production facilities particularly receptive to using Native American and transnational labour. They needed large numbers of workers in the summer when the salmon ran and in September when the hops ripened. The inconsistency of employment, the low pay, and the manual nature of the work held little appeal for the initial European settlers. Native American communities responded more favourably to these economic opportunities providing a necessary influx of labour. When the transnational labour migration of Native Americans peaked in 1885, as many as 6,000 First Nations from British Columbia (approximately fifteen to twenty percent of the First Nation population) migrated seasonally to Washington. The participation of large numbers of First Nations in these industries worried Indian agents because it limited the time Indian Agents had to “civilize” Indians and provided Native Americans with money the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) and Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) had no control over.

The seasonal nature of the canning and hops industries appealed to groups such as the Stó:lo- , Swinomish, and the Lummi, because it allowed First Nations to acquire commercial goods without interfering with other seasonal activities. For part of the year, First Nations communities prepared food for the winter. In July and August these communities left for the canneries, leaving behind only a few individuals to take care of the young children. In September thousands moved south to the hops fields. In the winter, some groups cut firewood or made woolen socks to sell to European settlers, while others engaged in local wage labour opportunities. The reliance of the regional economies in British Columbia and Washington on Native American labour allowed First Nations to retain their subsistence rights and their mobility. Attacking either risked disrupting the economic arrangements that had been made, and neither Canada nor the United States wished to lose access to an important source of labour.[19]

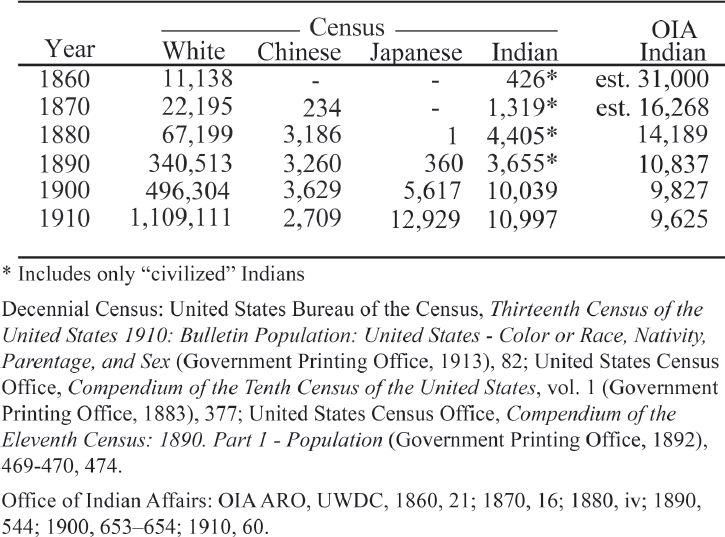

As European immigration to the Washington Territory grew exponentially during the mid-nineteenth century, local industries decreased their reliance on the transnational Native American labour force. During the 1860s, American Indians outnumbered whites living in Washington Territory by an estimated 3: 1. Two decades later the trend had reversed. European migrants became the most significant portion of the population outnumbering Native Americans 4: 1. British Columbia experienced a slower but similar reversal. The 1881 census recorded 25,661 First Nations (a substantial undercounting according to the Department of Indian Affairs), 16,861 Europeans, and 4,350 Chinese. By 1911 First Nations composed well under ten percent of British Columbia’s population. This demographic change reduced the power of Native Americans and decreased regional industries’ reliance on Indian labour.[20]

As local industries began to rely less and less on Native Americans labourers, it freed up Canada and the United States to implement more aggressive Indian policies. Indian agents, fishery patrols, and customs agents attacked First Nation’s mobility, culture, land, and resource gathering sites. In doing so, federal agencies began to adopt an interpretation of Indian status that neither granted First Nations the protections due to them under treaty, nor brought Indian policies in line with those governing whites or other racial groups. Instead, federal agents in both countries created economic policies that maintained First Nation’s separate legal, social, and economic classification, but transformed it from an identity that had once protected indigenous access to resources through treaty rights to one that used race to restrict their claims. When conflicts emerged between Indians and settlers, the federal governments supported white labourers and businessmen over Native American ones and passed a series of measures, including racially based fishing licenses, that resisted First Nations’ ability to work.[21]

Table 1

Washington's Population by Ethnic Origin 1860-1910

Table 2

British Columbia's Population by Ethnic Origin 1871-1911

Controlling the border, however, remained a tricky proposition. Direct border-control strategies continued to fail to address the needs of either country. Military, police, and customs personnel, already swamped with other tasks, including controlling Chinese immigration, could not keep pace. The border was too long, the transnational connections that First Nations communities maintained were too entrenched, and the Pacific Coast’s geography was too complex to be guarded by a handful of overworked and underpaid personnel. Faced with a difficult situation, federal administrators turned to indirect methods of control to help curtail the benefits Native Americans could gain from moving between national spaces. To do so, Canada and the United States targeted the social and economic bonds that connected transnational communities together, much as they had on the prairies, and began to punish those who resisted.

Indirect control showed signs of success. The drive to assimilate First Nations, their exclusion from productive resource sites, and the competition that Native American workers faced from Chinese, Japanese, and white workers all diminished the benefits groups such as the Stó:lo- and Lummi gained from their transnational mobility. The hops industry, which had once encouraged the seasonal migration of thousands of Indians from British Columbia into the United States, stopped being the reliable source of income it had once been. Market fluctuations, labour competition, and the appearance of the hops louse — which ravaged hops production — lessened the industry’s reliance on Native American labour and, as a result, reduced the income many communities had come to expect. By 1896 an Indian agent noted in his annual report of the Tulalip Agency in Washington that there existed little inducement for the Indians of the agency to travel to the hops fields because the value of the hops and need for Native American labour had diminished so severely.[22]

Economic changes on both sides of the border plagued Native American workers in the fishing and canning industries as well. In 1888, for example, British Columbia forced First Nations to either fish commercially under a licensing system or fish freely for subsistence. They could no longer do both. Canneries imposed a voluntary quota system of their own, limiting the number of Asians and Native Americans who could fish, and the Canadian government made it illegal for Natives Americans to catch fish in traps, weirs, or reef nets. This imposition prevented Native Americans from adopting new technologies as well as utilizing traditional ones. In 1900 the United States restricted fishing licenses to American citizens, which by definition excluded American Indians, and in 1913 British Columbia instituted a system of licensing that provided white fishermen with higher wages and more flexibility as to where they sold their fish than it allowed for either Native American or Asian fishermen. Fishery patrols began to levy fines and confiscate the gear of First Nations who refused to be bounded by the national borders or failed to obey European models of resource management. Confiscations could turn hunts, which would have been profitable, into financial disasters.

Groups such as the Lummi actively fought these changes. They took the United States government to court in 1895 over violations of their fishing rights. In other instances, Native American labourers resorted to vigilante justice, alongside their European counterparts, to try to prevent Chinese workers from displacing their own people on the jobsites. Neither strategy saw much success and the kinds of protections Native Americans had once enjoyed because of their importance in the labour market disappeared.[23]

The loss of reliable opportunities diminished the economic incentives for border crossings, but did not eliminate them entirely. The Kyukahts from the Alberni Agency in British Columbia continued to sell their baskets in Washington State in 1902. First Nations found work in the same areas of employment as in the past, albeit in lesser numbers. Labour shortages and short growing seasons in the hops, berry picking, and canning industries provided periodic surges in employment opportunities. The loss of consistent work, however, eliminated one of the primary motivations for transnational mobility that had been so commonplace in the 1880s.[24]

By the twentieth century, Canada and the United States possessed a variety of viable strategies to pressure First Nations living on the West Coast into adopting a single national identity. The American army did not forcibly evict “Canadian” Indians living in Washington State as it did on the prairies, but economic restrictions eliminated many of the benefits Native American communities could expect to gain by crossing national lines. As had happened on the plains, economic misfortune allowed the federal governments to use annuities, Indian status, and land recognition to punish those who continued to maintain regional rather than national ties. Both governments began to assault groups, such as the Sinixt, who retained ambiguous national identities, creating significant risks for those who continued to retain ties in both Canada and the United States.[25]

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Sinixt had travelled throughout the Columbia River system maintaining connections to various seasonal resource-gathering sites. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, they wintered near Fort Colville on the west coast of the United States and took advantage of the resources at Arrow Lakes north of the 49th parallel. The border bisected the territorial base of the Sinixt creating an uncomfortable ambiguity. The United States included them as part of the Colville Reservation, which initially contained land adjacent to the Canada-United States border. In 1892 Congress eliminated the northern half of the Colville Reservation to free the land up for miners. As a result, the middle section of the Sinixt’s territory was cut out, creating a stark divide between their lands in Canada and the United States. North of the line, the Canadian government set aside land for the Sinixt who remained on the shores of the Lower Arrow Lake.

By the 1930s British Columbia expressed its interest in the timber on the Arrow Lake Reserve. Over the next two decades, the Department of Indian Affairs, using all manner of inconsistencies — including creating temporary band status, amalgamating and then unamalgamating reserves, and conflating band membership with residency — removed the few remaining descendants of the Arrow Lake Band from their rolls and declared the band “extinct.” With no remaining legal members in the tribe, the land reverted to British Columbia’s control. Throughout the process, the Sinixt’s presence on both sides of the border provided a pretext for eliminating their legal status in Canada. Canada declared those residing south of the line to be ineligible for membership north of it. Legal recognition as an Indian could only be achieved on one side of the border or the other. Ambiguity ceased to allow Native American communities to play one government off against the other. Instead, uncertainty became a liability that allowed federal officials to strip First Nations’ communities of their title to land and resource gathering sites.[26]

The Withering of Direct Control

During the early twentieth century, direct forms of control began to impact the transnational movements of non-indigenous peoples to a much greater extent, owing in part to expanded funding to agencies such as customs and immigration. At the same time, a series of legal challenges brought into question what jurisdiction if any these agencies had over Native Americans. In 1924, for example, the United States passed the Indian Citizenship and National Origins Acts, which created an unintentional challenge to the transnational movements of Native Americans labourers along the border’s entire length. The Indian Citizenship Act made “all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States … citizens.” [27] During the same year, the National Origins Act created a quota system to restrict yearly immigration to the United States. Although the National Origins Act did not address the transnational movements of Native Americans specifically, immigration officials began to use Section 13 (c) to restrict First Nation’s mobility. Section 13 (c), which declared “no alien ineligible to citizenship shall be admitted to the United States,” had been intended to restrict Chinese and Japanese immigration.[28] The act’s wording, however, allowed immigration agents to prevent Canadian Indians, who were inadmissible for citizenship under the American Indian Citizenship Act, from crossing the border.

The broad interpretation immigration agents took towards the National Origins Act worried business owners such as the McNeff Brothers who operated in Washington. The brothers wrote to John W. Summers in 1925 stating that preventing fruit, produce, and hops farmers in Washington from utilizing the labour of First Nations from British Columbia would hurt their business, and made little sense. The Indians from British Columbia “are more or less intermarried with the Indians in western Washington and Yakima and for the last 40 years (and more) hundreds of the B.C. Indians have come across the line to visit and work during the fruit and hops harvests.”[29] Farmers no longer depended on Indians from British Columbia to the extent they had during the 1880s, but they still feared anything that disrupted their ability to draw on a versatile labour market. Flexible hiring options, especially during short harvest seasons or labour shortages, could make the difference between profit and debt. Immigration officers allowed Indians from British Columbia to come to Puget Sound “on an emergency basis” to harvest fruit crops after the restrictions, but their position remained tenuous.[30]

The interpretation immigration agents took towards the provisions of the National Origins Act fostered opposition within many Native American communities. Their challenges to the act took many forms including a legal challenge by Paul Diabo, a Mohawk ironworker from Québec, against the National Origins Act’s applicability to Native Americans. On 18 March 1927, district Judge Oliver B. Dickinson ruled in favour of Diabo. The National Origins Act did not apply to Native Americans, and Indians would be allowed to cross the border without obstructions. The United States Immigration Service appealed the decision and opponents of Diabo’s court case contended it only applied to Six Nations, which would have left the restrictions in force across the rest of the boundary.[31]

The Immigration Service lost its appeal and the United States Congress clarified the matter on 2 April 1928, when it confirmed the right of all First Nations born in Canada to pass into the United States. The 1928 Act, however, left gray areas over who fulfilled the criteria of being an “Indian.” Non-enrolled mixed bloods blurred the lines that Indian agents and immigration officials attempted to draw, forcing them to adopt functional definitions of identity based on blood quantum and tribal identity, which were hard to establish in practice. The decision made Indian status and federal recognition an integral facet to the ability of First Nations to cross the border unmolested.[32]

The Department of Immigration’s defeat over the interpretation of the 1924 acts neutered the kinds of direct border-control strategies Canada and the United States could pursue. By that point, however, both countries had ample experience influencing the ways Native Americans interacted with national spaces through other means. Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Canada and the United States had developed a suite of indirect forms of control that undermined the motivations First Nations had for maintaining transnational connections on the Prairies and West Coast. Federal administrators chose reservation locations away from the border to increase the travel times of transnational movements. They withheld treaty goods from groups who disobeyed Indian agents or spent too much time beyond the confines of the nation state. Both federal governments attacked the cultural and economic practices that drew First Nations communities on both sides of the border together. Indian status and legal recognition became tools, which Canada and the United States used to control how Indians moved between national spaces.

Federal policy tore away at the connections Native American communities maintained across the border and encouraged them to adopt a single nationality. Many groups refused to do so, and have maintained transnational connections to this day. The kinds of benefits they could gain from doing so, however, eroded over time. The potential risks, as seen by Canada’s declaration that the Arrow Lakes Band had become extinct and by the Cree’s struggle to secure a reservation, grew in significance. Legal recognition as an Indian could only be achieved on one side of the border or the other. Ambiguity, which had once allowed Native American communities to circumvent federal authority, had become a powerful tool to strip groups of their legal title to land and resources.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Andrew Graybill, Stephen A. Aron, Richard White, and three anonymous reviewers for their feedback at various stages of this paper as well as financial support from Stanford University and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council.

Biographical note

BENJAMIN HOY is an Assistant Professor at the University of Saskatchewan. His work addresses the formation of the Canadian-United States border, federal attempts to enumerate First Nations, and racial violence.

Notes

-

[1]

For a brief cross section of the borderlands literature see Sterling Evans, ed., The Borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests: Essays on Regional History of the Forty-Ninth Parallel (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006); Karl S. Hele, ed., Lines Drawn upon the Water: First Nations and the Great Lakes Borders and Borderlands (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2008); John J. Bukowczyk, Permeable Border: The Great Lakes Basin as Transnational Region 1650–1990 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005); Benjamin H. Johnson and Andrew R. Graybill, eds., Bridging National Borders in North American: Transnational and Comparative Histories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010); John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000); John Herd Thompson and Stephen J. Randall, Canada and the United States: Ambivalent Allies (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008); John Boyko, Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013); Richard A. Preston, The Defense of the Undefended Border: Planning for War in North America 1867–1939 (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1977); Bruno Ramirez, Crossing the 49th Parallel: Migration from Canada to the United States 1900–1930 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001); Sarah Carter and Patricia McCormack, ed., Recollecting: Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2011); Kornel S. Chang, Pacific Connections (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012); Sheila McManus, The Line Which Separates: Race, Gender, and the Making of the Alberta-Montana Borderlands (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005); Andrew R. Graybill, Policing the Great Plains: Rangers, Mounties, and the North American Frontier 1875–1910 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

-

[2]

National Archive Pacific Northwest Region (hereafter NA PNR), RG 36, U.S. Customs Service, Puget Sound, Box 37 Letters sent to the Secretary of the Treasury 1881–1886, Book 2, A.W. Bash to Daniel Manning, 22 April 1885, 376.

-

[3]

NA PNR, RG 36, U.S. Customs Service, Puget Sound, Box 37 Letters sent to the Secretary of the Treasury 1881–1886, Book 2, Unsigned [likely A.W. Bash] to Wm. F. Snitzler, 15 June 1885, 426–8; NA PNR, RG 36, U.S. Customs Service, Puget Sound, Box 109, Letters Received From SubPorts and Inspectors, San Juan, File 3, A.L. Blake to A.W. Bash, 5 May 1883; Nicholas R. Parrillo, Against the Profit Motive: The Salary Revolution in American Government 1780–1940 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 4.

-

[4]

McManus, The Line Which Separates, 71–4; Graybill, Policing the Great Plains, 61; for an example of the struggle to control individuals see the case of Thomas Faval. Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC), RG 10, Vol. 3573, File 142, Pt. G, Reel C-10188 [Online], Indian Commissioner for Manitoba and Northwest Territories, Indians Enrolled in Canada and United States, 26 May 1908, 64–71.

-

[5]

University of Waterloo, Microfilm CA1 IA H5P37, “Papers Relating to the Sioux Indians of U.S. who have Taken Refuge in Canadian Territory,” 13 December 1875 to 14 April 1879, (hereafter Papers Relating to the Sioux), F.W. Seward to Sir Edward Thornton, 13 February 1879, 133; David G. McCrady, Living with Strangers: The Nineteenth-Century Sioux and the Canadian-American Borderlands (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 4, 92, 110; Michel Hogue, “Disputing the Medicine Line: The Plains Crees and the Canadian-American Border, 1876–1885,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 52, no. 4 (1 December 2002): 4–11; Peter Douglas Elias, The Dakota of the Canadian Northwest: Lessons for Survival (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 2002), 57, 83, 222; Andrew C. Isenberg, The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 140–3; William A. Dobak, “Killing the Canadian Buffalo, 1821–1881,” The Western Historical Quarterly 27, no. 1 (1996): 33-52; McManus, The Line Which Separates, 73; Gerhard J. Ens, “The Border, the Buffalo, and the Métis of Montana,” in The Borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests: Essays on Regional History of the Forty-Ninth Parallel, 147.

-

[6]

McManus, The Line Which Separates, 66.

-

[7]

LAC, RG 10, Indian Affairs, Black Series, Reel C-10114 [Online], Volume 3651, File 8527, “Notes Taken at a Meeting between the Lieut. Governor of the NW Territories Attended by the Officers of the Mounted Police at the Station and a Deputation of about 20 Sioux Indians Headed by a Chief Named White Cap at Swan River on the 29th Day of June ’77,” 29 June 1877; Archive of Manitoba (hereafter AM), Alexander Morris (Lieutenant-Governor’s collection) MG 12 B1, Microfilm Reel M135, No 811, Bernard to Alexander Morris, 16 July 1874; Elias, The Dakota of the Canadian Northwest, 18–19, 37–41, 57, 152–9, 205; LAC, RG 10, Indian Affairs, Volume 3577, File 422 [Online], D. Gunn et al., “Petition,” c 1872, “Manitoba – Proposal for Reservation for Refugee Sioux Indians from the United States”; McCrady, Living with Strangers, 16, 105–6; Alvin C. Gluek Jr., “The Sioux Uprising: A Problem in International Relations,” Minnesota History (Winter 1955), 320, 324; LAC, Department of Indian Affairs Annual Reports (1864–1990) [Online] (hereafter DIA ARO), J.A. Markle to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, 16 August 1900, 132; John D. Bessler, Legacy of Violence: Lynch Mobs and Executions in Minnesota (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 25–46; John S. Bowman, Chronology of Wars (New York: Infobase publishing, 2003), 86–8; Gontran Laviolette, The Sioux Indians in Canada (Regina: Saskatchewan Historical Society, 1944), 31-35.

-

[8]

“An Act to Amend and Consolidate the Laws Respecting Indians Assented to 12th April, 1876,” in Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (Ottawa: Brown Chamberlin, 1876), 44.

-

[9]

AM, Alexander Morris (Lieutenant-Governor’s collection) MG 12 B1, Microfilm Reel M135, No 718, D.R. Cameron to Alexander Morris, 29 April 1874; McCrady, Living with Strangers, 73–4; Dobak, 48; University of Waterloo, Papers Relating to the Sioux, H. Richardson to Assistant Commissioner Irvine, 26 May 1876, 1–2, G. Irvine to Lieut-Colonel Richardson, 1 July 1876, 2, J.M Walsh to J.F. Macleod, 31 December 1876, 9–10, and W.T. Sherman to G.W. McCrary, 16 July 1877, 36–7; LAC, RG 10, Indian Affairs, Volume 3766, File 32957 [Online], “Northwest Territories – Sioux Indians Crossing the International Boundary and Requesting Direction as to Whether they will be Allowed to Stay or be Sent Back to the United States,” Hayter Reed to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, 24 September 1886; Indian Commissioner for Manitoba and Northwest Territories, Indians Enrolled In Canada and United States, 3; for examples of sanctioned crossings see LAC, RG 10, Indian Affairs, Volume 2676, File 135,883, “Alnwick Agency - Request from Allan and Wellington Salt, for Permission to Reside in the United States”; LAC, RG 10, Vol. 2821, File 168,097, Alnwick Agency – Application of Hannah Eliza Cox (Mrs. James Cox) and George Cowe for Permission to Reside in the United States [Online], Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs to John Thackeray, 7 December 1895.

-

[10]

Michel Hogue, “Crossing the Line: Race, Nationality, and the Deportation of the ‘Canadian’ Crees in the Canada-U.S. Borderlands 1890–1900,” in The Borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests, 155–71; Hans Peterson, “Imasees and His Band: Canadian Refugees after the North-West Rebellion,” Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 8, no. 1 (1978): 30, 33; United States Congress, “Relief for the Cree Indians, Montana Territory,” in The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Fiftieth Congress 1887–1888, vol. 2561, Ex. Doc. No. 341 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889), 1–6.

-

[11]

LAC, DIA ARO, A.E. Forget to Superintendent of Indian Affairs, 20 November 1897, 216.

-

[12]

Glenbow Archives, M7937, Geneva Stump’s Rocky Boy Collection (hereafter Rocky Boy Collection), Little Bear to J.D. McLean, 30 March 1905, David Laird to Little Bear, 24 January 1906, Little Bear to Secretary of the Interior, 10 February 1905, Superintendent of Indian Affairs to Governor General in Council, 1 August 1908, and Little Bear to Frank Oliver, 7 November 1905; Ed Stamper, Helen Windy, and Ken Morsette Jr., eds., The History of the Chippewa Cree of Rocky Boy’s Indian Reservation (Montana: Stone Child College, 2008), 11–6; Brenden Rensink, “Native But Foreign: Indigenous Transnational Refugees and Immigrants in the U.S.-Canadian and U.S.-Mexican Borderlands 1880–Present” (Ph.D. diss., University of Nebraska, 2010), 5–6; Verne Dusenberry, “The Rocky Boy Indians,” The Montana Magazine of History 4, no. 1 (Winter 1954): 10–4; Michel Hogue, “Crossing the Line,” 166.

-

[13]

University of Wisconsin Digital Collections (hereafter UWDC)[Online], Office of Indian Affairs Annual Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (hereafter OIA ARO), J.W. Nesmith to Charles E. Mix, “No. 79,” 20 August 1858, 219.

-

[14]

UWDC, OIA ARO, George A. Paige to W. H. Waterman, “No 10,” 8 July 1865, 99.

-

[15]

UWDC, OIA ARO, G.A. Paige to Col. J.W. Nesmith, “No 136,” 1 August 1857, 331; UWDC, OIA ARO, M.T. Simmons to J.W. Nesmith, “No. 137,” 1 July 1857, 332; UWDC, OIA ARO, M.T. Simmons to Colonel J.W. Nesmith, “No. 81,” 30 June 1858, 236; UWDC, OIA ARO, M.T. Simmons to Edward R. Geary, “No. 180,” 1 July 1859, 396; UWDC, OIA ARO, Edward R. Geary to A.B. Greenwood, “No. 77,” 1 October 1860, 182; Jeremiah Gorsline, ed., Shadows of Our Ancestors: Readings in the History of Klallam-White Relations (Port Townsend, WA: Empty Bowl, 1992), 35; Lissa K. Wadewitz, The Nature of Borders: Salmon, Boundaries, and Bandits on the Salish Sea (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012), 69.

-

[16]

UWDC, OIA ARO, Geo. W. Manypenny to Isaac I. Stevens, 9 May 1853, 216; Coll Thrush, Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place (United States: University of Washington Press, 2007), 52–4; Alexandra Harmon, Indians in the Making: Ethnic Relations and Indian Identities Around Puget Sound (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 65–6; Barry M. Gough, Gunboat Frontier: British Maritime Authority and Northwest Coast Indians, 1846–90 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1984), 12, 57–9, 158.

-

[17]

Colonial pressure did not end raiding on its own. The Haida, for example, began to consider whether the costs of raiding outweighed its benefits. By ending or limiting slave raiding, indigenous groups made their treks to wage labour markets safer by reducing the chances of reciprocal violence or unexpected encounters with hostile people. UWDC, OIA ARO, M.T. Simmons to Edward R. Geary, “No. 78,” 1 July 1860, 190–1; UWDC, OIA ARO, Henry A. Webster to Calvin H. Hale, “G4 Territory of Washington - Treaties of Neah Bay and Point-No-Point 1855,” 1862, 410; John Lutz, “Work, Sex, and Death on the Great Thoroughfare: Annual Migrations of ‘Canadian Indians’ to the American Pacific Northwest,” in Parallel Destinies: Canadian-American Relations West of the Rockies, ed. Ken S. Coates and John M. Findlay (United States: University of Washington Press, 2002), 89–94; Leland Donald, Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 229–30, 245; John S. Lutz, Makúk: A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008), 169.

-

[18]

UWDC, OIA ARO, E.A. Starling to Anson Dart, “No. 71,” 1 September 1852, 171; Lutz, Makúk, 171; Gorsline, Shadows of Our Ancestors, 82; UWDC, OIA ARO, Hal J. Cole to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 15 August 1891, 441; John Lutz, “Work, Sex, and Death,” 82; British Columbia Archive (hereafter BCA), James Douglas Fond, A/C/20/Vi/2A, James Douglas to Archibald Barclay, “On the Affairs of Vancouver Island,” 5 October 1852, 101; Thrush, Native Seattle, 41, 47–9, 71; University of Washington Special Collections, Melville Jacobs Collection (Narrative taken by Paul Fetzer, 1951), 1693-91-13-001 Box 112, V 206, Folder 10, George Swanaset, “George Swanaset: Narrative of a Personal Document” 10; Elizabeth Rose Lew-Williams, “The Chinese Must Go: Immigration, Deportation and Violence in the 19th-Century Pacific Northwest” (Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 2011), 55–56; UWDC, OIA ARO, J.H. Jenkins to Colonel M.T. Simmons, “No. 82,” 27 May 1858, 237.

-

[19]

LAC, DIA ARO, W.H. Lomas to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, 7 August 1885, 80; LAC, DIA ARO, I.W. Powell to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, 5 November 1886, 98; NA PNR, RG 36, U.S. Customs Service, Puget Sound, Box 109, Letters Received From SubPorts and Inspectors, San Juan, File 4, Ira B. Myers to A.W. Bash, 9 August 1883; Lissa K. Wadewitz, The Nature of Borders, 68–72; NA PNR, RG 75, Annual Reports Tulalip Agency, Box 1 1863-1908, Folder 1902, Edward Bristow to Charles M. Buchanan, 15 July 1902; NA PNR, RG 75 Letters received – Tulalip Agency, Swinomish, Box 7 1899–1904, Edward Bristow to Charles M. Buchanan, 7 July 1903; Russel Lawrence Barsh, “Puget Sound Indian Demography, 1900–1920: Migration and Economic Integration,” Ethnohistory 43, no. 1 (Winter 1996): 66, 69–70, 77–80; Gorsline, Shadows of Our Ancestors, 82; Lutz, Makúk, 93, 190; Thrush, Native Seattle, 111; LAC, DIA ARO, A.W. Neill to Frank Pedley, 30 June 1906, 255; Daniel L. Boxberger, “In and Out of the Labor Force: The Lummi Indians and the Development of the Commercial Salmon Fishery of North Puget Sound, 1880–1900,” Ethnohistory 35, no. 2 (1 April 1988): 172.

-

[20]

Demographic changes did not affect all parts of the coast in the same way. The European population that came to British Columbia settled on the southern portion of the province near Vancouver Island, giving them a disproportionate influence near the border and a relatively weak presence in the northern interior. In 1881 First Nations vastly outnumbered whites and Chinese on the Skeena and Nass rivers on the northwest coast. In the south, near Vancouver Island, by contrast, non-Natives comprised three-fourths of the population in 1881. Cole Harris, The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on Colonialism and Geographical Change (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1997), 149–53.

-

[21]

Daniel L. Boxberger, “Ethnicity and Labor in the Puget Sound Fishing Industry, 1880–1935,” Ethnology 33, no. 2 (1 April 1994): 183; University of Washington Special Collections, Henry Doyle Collection, Acc. 861, Box 3, Book 1908–1911, “White Fisherman Are Best for B.C.,” New Advertiser, 17 December 1911; Lissa K. Wadewitz, The Nature of Borders, 78–87; Daniel L. Boxberger, “The Not So Common” in Be of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish, ed. Bruce Granville Miller (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 2007), 60; Lutz, Makúk, 239–42.

-

[22]

NA PNR, RG 75, Annual Reports Tulalip Agency, Box 1 1863-1908, Folder 1896, D.C. Govan to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 28 August 1896; Jean Barman, The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 160; NARA, RG 85, INS, Entry 9, Box 6585, 55466/182, McNeff Brothers to John W. Summers, 20 July 1925; Great Britain, Foreign Office, Diplomatic and Consular Reports. Annual Series. United States, San Francisco, vol. 906, 1891, 27.

-

[23]

Lissa K. Wadewitz, The Nature of Borders, 81–87; Lutz, Makúk, 239–242; Lew-Williams, The Chinese Must Go, 118, 129.

-

[24]

LAC, DIA ARO, A.W. Neill to Frank Pedley, 30 June 1906, 255; LAC, DIA ARO, Alan W. Neill to Frank Pedley, 26 July 1905, 248; LAC, DIA ARO, Harry Guillod to Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, 27 August 1902, 265.

-

[25]

NA PNR, RG 75, Tulalip Agency, Records of Court of Indian Offences 1907–1947, Folder 1, E.B. Merritt to Secretary of the Interior, 10 November 1923; NA PNR, RG 75, Tulalip Agency, Records of Court of Indian Offences 1907-1947, Folder 1, C.F. Hauke to D.W. Lambuth, 14 August 1924; NA PNR, RG 75, Letters received – Tulalip Agency, Swinomish, Box 8, Folder 4, Edward Bristow to Jesse E. Flanders, 30 December 1908.

-

[26]

Andrea Geiger, “Crossed by the Border: The U.S.-Canada Border and Canada’s ‘Extinction’ of the Arrow Lakes Band, 1890–1956,” Western Legal History 23, no. 2 (Summer/Fall 2010): 121–53.

-

[27]

NARA, RG 11, General Records of the United States, Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, Public Law 68-175, 43 STAT 253, United States Congress, “An Act to Authorize the Secretary of the Interior to Issue Certificates of Citizenship to Indians,” 2 June 1924.

-

[28]

United States, “An Act to Limit the Immigration of Aliens into the United States, and for Other Purposes [Immigration Act of 1924],” 26 May 1924, 68th Congress, Session 1, Ch. 190, H.R. 7995 Public No 139.

-

[29]

NARA, RG 85, INS, Entry 9, Box 6585, 55466/182, McNeff Brothers to John W. Summers, 20 July 1925.

-

[30]

NARA, RG 85, INS, Entry 9, Box 6585, 55466/182, C.V. Maddux to Commissioner General of Immigration, 19 July 1926.

-

[31]

Gerald F. Reid, “Illegal Alien? The Immigration Case of Mohawk Ironworker Paul K. Diabo” 151, no. 1 (March 2007): 72–3; Clinton Rickard, Fighting Tuscarora: The Autobiography of Chief Clinton Rickard, ed. Barbara Graymont (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1973), 76–7; United States ex rel. Diabo v. McCandless (District Court, E.D. Pennsylvania, 18 F.2d 282; 1927 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 1053 1927); NARA, RG 85, INS, Entry 9, Box 6585, 55466/182a, W.W. Husband to Charles Curtis, 3 October 1927.

-

[32]

Clinton Rickard, Fighting Tuscarora, 90, 112–3, 119; McCandless, Commissioner of Immigration. v. United States ex rel. Diabo (Circuit Court of Appeals, Third Circuit, 25 F.2D 71, U.S. App. LEXIS 2899 1928); NARA, RG 85, INS, Entry 9, Box 6586, 55466/182b, J. Henry Scattergood to Mr. Hull, 22 September 1930; NARA, RG 85, INS, Entry 9, Box 6586, 55466/182b, John D. Johnson, “Admission into the United States of American Indians Born in Canada”; United States, “An Act to Exempt American Indians Born in Canada from the Operation of the Immigration Act of 1924,” approved 2 April 1928, [S 716], 45 Stat. 401, 76th Congress, 3d Session, Document No. 194, Chap. 308, in Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, ed. by Charles J. Kappler, vol. 5 (United States: Government Printing Office, 1941).

Appendices

Note biographique

BENJAMIN HOY est professeur adjoint à l’Université de Saskatchewan. Ses recherches portent sur la formation de la frontière canado-américaine, sur les tentatives fédérales de dénombrer les Premières Nations et sur la violence raciale.

List of tables

Table 1

Washington's Population by Ethnic Origin 1860-1910

Table 2

British Columbia's Population by Ethnic Origin 1871-1911