Abstracts

Abstract

This article examines public school taxes, housing, and changing suburban space in Etobicoke Township (suburban Toronto) between 1945 and 1954. Bridging educational and urban and suburban history, and incorporating recent insights from tax history, it examines the role that school taxes played in transforming Etobicoke from a rural and income-mixed pre-war suburb into a more middle-class, homogenous post-war one. School trustees taxed the new, middle-class housing being constructed in the suburb to underwrite educational expenditures that expanded and modernized the Etobicoke public school system. At the same time, tax and other public policy excluded lower-value rental housing and small dwellings, and also excluded their residents, who did not contribute enough in property taxes to support the emerging suburban school system. School taxes marked inclusion and exclusion in changing Etobicoke. As suburban space changed, established working-class residents and farmers tried to defend their interests as school taxpayers. Farmers could not defend their interests in the same way, and many sold their properties to sub-dividers for housing, erasing farms and one-room schools from the suburban landscape. The history of suburbanization and the history of educational expansion and modernization were causatively dependent on one another. Historians of education and urban and suburban historians benefit from drawing on each other’s aligned historiographies, and from looking at taxes.

Résumé

Cet article examine les taxes scolaires, le logement et l’évolution de l’espace suburbain dans le canton d’Etobicoke (banlieue de Toronto) entre 1945 et 1954. Faisant le lien entre l’histoire de l’éducation et celle de la ville et de la banlieue, et intégrant les connaissances nouvelles de l’histoire fiscale, le texte examine le rôle que les taxes scolaires ont joué dans la transformation d’Etobicoke, qui est passée d’une banlieue rurale d’avant-guerre à revenu mixte à une banlieue plus homogène de classe moyenne d’après-guerre. Les commissaires d’école ont taxé les nouveaux logements de classe moyenne construits dans la banlieue pour financer les dépenses liées à l’éducation qui ont permis d’étendre et de moderniser le système scolaire public d’Etobicoke. En même temps, les politiques fiscales et autres politiques publiques excluaient les petits logements abordables, et excluaient également les résidents de ceux-ci, qui ne contribuaient pas suffisamment aux taxes foncières pour soutenir le système scolaire de banlieue naissant. Les taxes scolaires ont accentué l’inclusion et l’exclusion durant l’évolution d’Etobicoke. Alors que l’espace suburbain se transformait, les résidents de la classe ouvrière et les agriculteurs qui y étaient établis ont tenté de défendre leurs intérêts en tant que contribuables scolaires. Les agriculteurs ne pouvaient pas défendre leurs intérêts de la même manière, et nombre d’entre eux ont vendu leurs propriétés pour faire place à des subdivisions résidentielles, supprimant ainsi les fermes et les écoles à classe unique du paysage suburbain. L’histoire de la banlieusardisation et l’histoire de l’expansion et de la modernisation de l’enseignement étaient dépendantes l’une de l’autre. Les historiens de l’éducation et les historiens des villes et des banlieues ont intérêt à s’inspirer de leurs historiographies respectives et à se pencher sur les taxes.

Article body

Canadian historians of education have not paid school taxes much attention.[1] They have also largely ignored urban and suburban history, only infrequently drawing theoretical or analytical insights from these historiographies.[2] Urban and suburban historians have just as frequently disregarded schools and educational history.[3] Yet, in the early post-war period, the histories of suburbanization, of taxation, and of educational expansion and modernization were causatively dependent on one another.[4] People in the Toronto suburb of Etobicoke lived that dependence, although Canadian historians have hardly noticed it existed. In the 1945–1954 period Etobicoke Township made an historic transition from a pre-war suburb, consisting of farms and a mixture of working-class and more upscale housing subdivisions, to a post-war, largely middle-class residential suburb.[5] Urban historians have peered into the public policy toolbox for transforming post-war suburban space that contained federal mortgage legislation, new municipal planning and zoning bylaws, and municipal building codes. School taxes were the other tool in that toolbox that historians have mostly overlooked.[6] Public schools were by far the biggest item on the Etobicoke property tax bill. By 1953, they accounted for forty-eight cents on the municipal tax dollar.[7] New studies by Elsbeth Heaman, Shirley Tillotson, and David Tough alert us to tax’s often neglected significance to Canadian history.[8] Taxation was one very important way the state defined citizenship and belonging, and distributed wealth and opportunity. Tax debates represent “the eternal conversation, about the interface between rich and poor, state and citizen,” Heaman writes.[9] School taxes in Etobicoke in the late 1940s and early 1950s helped define inclusion and exclusion, or who belonged and who did not, in the changing suburb. Both the historic remaking of suburban space and school taxes were crucial to an expansion and modernization of Etobicoke’s public school system as well. The post-war “enthusiasm for investing in education” seized Etobians, just as it did people across the province and country.[10] New suburban homes and taxes paid for that investment. Like Etobicoke’s suburban landscape, Etobicoke schools transitioned also, from modest nineteenth-century schoolhouses (see Figure 2) to mid-twentieth-century modern institutes of learning (see Figure 3).

In this article, I will show how developers, public school trustees, municipal councillors, the township planning board, and middle-class ratepayers in Etobicoke made a suburb of middle-class houses and modern schools, and created tax advantages mostly for middle-class homeowners. Developers built new middle-class single-family tract housing that was assessed at a relatively high value. School trustees taxed that value to pay for schools. With help from new industries and businesses that also located to Etobicoke in this period and paid property taxes in support of public schools, as well as help from provincial education grants, Etobicoke’s public school board raised the revenues it needed to expand and modernize the township’s public schools. Township council and the planning board defended the township’s increasingly wealthy total tax assessment. This kept homeowners’ school tax rates down, even as school trustees increased educational spending drastically. Middle-class ratepayers, municipal councillors, and the planning board used school taxes to try to exclude various types of working-class renters and owners of small houses from Etobicoke. They did this in order to unburden middle-class homeowners from the cost of carrying too many of these free-riding residents. (A “free-rider” pays nothing or underpays for a public good.) Working-class homeowners who had established themselves in Etobicoke pre-war and the township’s farmers struggled to defend their particular interests in Etobicoke as taxpayers. That struggle’s outcome, largely not in their favour, further solidified Etobicoke’s transition to mainly middle-class suburban space.

Etobicoke Township Transformed

Today Etobicoke (pronounced \e-ˈtō-bi-ˌkō) is part of Toronto. In 1945, it was an independent municipality on the City of Toronto’s western edge. At approximately the mid-twentieth century, two thirds of Etobicoke Township, as it was then known, was covered by farms and dotted with farming villages. The remaining one third consisted of scattered housing subdivisions.[11] There were more upscale residential areas, such as Kingsway Park.[12] However, historian Richard Harris paints a different and unfamiliar picture of Toronto’s pre-war suburbs, a portrait that encompasses many other Etobicoke Township subdivisions quite unlike Kingsway Park. More inhabitants of pre-war suburbs were working-class, not middle-class, Harris observes. Few suburbanites owned cars. They walked to work or rode the street railway. The suburbs attracted many people who could not afford expensive urban housing, or the city’s costly municipal services and taxes. Many suburban residents did not have money to pay a professional builder either and built their homes with their own hands instead. They added to their dwellings over time, unable to borrow enough to buy the whole house at once. The passersby could see homeowners’ “sweat equity,” as Harris calls it, in the structures of pre-war suburbia, a kaleidoscope of styles unhurriedly assembled as time and finances permitted.[13] Alderwood in Etobicoke Township’s southwest corner, Humber Bay where the Humber river empties into Lake Ontario, and Humbervale and Westmount further north on the river across from the Town of Weston, were Etobicoke working-class subdivisions like the ones Harris has described.[14] (See Figure 1).

These sorts of humble suburbs, in Etobicoke and elsewhere, were transforming rapidly by the late 1940s and early 1950s. The new suburban housing that was constructed in post-war Etobicoke was a different product than what had existed there before, especially in places like Alderwood, Humbervale, or Westmount. Public policies from all levels of government drove the transformation of suburban housing stock from its pre-war to its post-war form. Federal housing legislation made mortgage financing much easier to obtain, but also favoured the construction of certain types of homes. Under new federal mortgage insurance rules, and a federal “joint loans” program, large numbers of suburban purchasers qualified for a desirable long-amortizing (low down-payment, 25-year) mortgage. That mortgage was only available on homes that met federal eligibility requirements. To qualify the home as eligible, the builder had to follow guidelines that the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) devised. These guidelines guaranteed that houses would be of a sufficient quality and value to reduce lender risk. To accomplish this, the CMHC guidelines set strict minimum standards. They applied to lot size and frontage. (Frontage is the lot’s width, usually measured where it faces the street). CMHC minimums applied to building materials as well. The minimums encouraged larger, new, professionally-built houses that sat on larger lots and that building companies erected in batches in the suburbs.[15] These homes gave the suburban landscape a different look, that of the modern tract housing that we identify with suburbia today.

Figure 1

Map of Etobicoke.

Municipal zoning by-laws contributed to the transformation of suburban housing stock as well. These by-laws also strongly favoured the construction of higher value, single-detached homes, of relatively generous size on bigger lots. The purpose of zoning by-laws like these was to protect property values for owners. As I will show a little later in this article, protecting values like this also shored up the tax assessment base, which was hugely significant for municipal and public school tax rates in Etobicoke. “Control and conservation measures, such as zoning, will be the most important instruments in guiding the development of Etobicoke,” the 1947 township official plan states, “thereby preventing undesirable development and the decline of land values.”[16] The provincial government required municipalities who wished to pass a zoning bylaw covering their entire municipality to establish a planning board first. Etobicoke was one of the first Ontario municipalities to establish such a board.[17] Etobicoke’s township planning board, which the township council formed in 1946, comprised nine appointed members. Several of these men also served on the council.[18] Etobicoke’s first township-wide zoning bylaw, which council passed in 1949, allowed builders to erect relatively spacious, single-detached homes on big lots, in any of the municipality’s residential zones, whereas it restricted multi-family units, like apartments and even duplexes and row houses, to only a few, much smaller zones.[19] The bylaw set minimum frontages for residential lots at a relatively large forty or fifty feet.[20] Lots this size were double the typical pre-war suburban frontage.[21] The square footage of houses was by-law controlled as well. Tellingly, the bylaw set a minimum square footage — to prevent single-family homes from getting too small — but did not set a maximum that stopped them from being large.[22] Even the Etobicoke building code, which the 1949 zoning bylaw amended and strengthened, encouraged the new type of construction, with the goal of further protecting property values. Like other building codes revised in the post-war period, it forced builders to use better materials. This increased house values and favoured professional building companies who had the abilities to acquire and use those materials, excluding amateur owner-builders who did not.[23]

As urban historians such as Kenneth T. Jackson and Robert O. Self have observed about the United States, zoning laws and other municipal codes were powerful public policy tools that post-war suburban residents and politicians used quite intentionally to form their communities economically and socially. They used them to consolidate valuable property, and better-off (and often white) populations, in selective suburbs. They pushed away undesired land uses — and land users. Consequently, zoned communities, like Etobicoke, were more homogeneous, not least of all because post-war suburbs applied exclusionary zoning heavily.[24] In the pre-war period, sub-dividers had used private measures on a much smaller scale to control land use and to screen residents. Etobicoke’s Kingsway Park, quite typically for a wealthier subdivision, employed restrictive covenants for this purpose.[25] In the post-war period, public policy did the job of excluding people and it could do that job more effectively than pre-war private measures could.

The new suburban housing attracted a different kind of home-purchaser to Etobicoke Township in the post-war period than often had lived there pre-war. These purchasers, who also arrived in unprecedented numbers, were more apt to be middle-class. To buy a new suburban home, the post-war purchaser had to have money to pay a professional builder and access to credit to get a mortgage. The purchaser was also choosing from a stock of houses that were costlier because they were larger, sat on bigger lots, and were built to a higher standard. Historians have inferred these purchasers were middle-class.[26] John Bélec, Richard Harris, and Geoff Rose used case studies of mortgage data from Hamilton and Vancouver in 1951 to actually confirm “a pattern of selection by income” among residents moving to these cities’ suburbs. Middle-class borrowers, and some blue-collar borrowers with incomes close to the middle-class range, were the ones qualifying for the CMHC-insured mortgages that Bélec, Harris, and Rose looked at. These mortgage holders moved in large numbers to the new post-war suburbs where they segregated themselves into new subdivisions that were “relatively homogeneous” by income, including many middle-class ones. The study uses the only available income data for borrowers who held CMHC-insured mortgages.[27] However, other evidence as well hints strongly at middle-class influx into suburbs like Etobicoke in the post-war period. Harris found that in 1951, 49 per cent of the Toronto area’s “old” suburban housing units still had blue-collar occupants. However, blue-collar families occupied just 35 per cent of new suburban units.[28] This suggests that the suburban population was turning over in class terms as middle-class families arrived to take up residence in the new houses being constructed.[29] The number of new units in Etobicoke, the type Harris found less likely to house blue-collar occupants, grew quickly in the early 1950s. The total value of construction permits for new residential units in Etobicoke increased by over $20 million between just 1951 and 1954, nearly doubling their value. By comparison, the value of permits for repair construction of old units grew slowly, increasing only by approximately one quarter during the same period.[30] Largely on the strength of new housing construction, Etobicoke Township’s population ballooned. There were approximately 21,000 residents in 1945, but over 83,000 by 1954. [31] This increase represented an influx of new and almost assuredly middle-class families moving into suburbs to occupy newly built houses.

Modern Schools as Suburban Services

Post-war occupants of suburban homes in Etobicoke viewed investing in municipal services and schools differently than pre-war residents had. Their mood about paying taxes needed to support services and schools differed also. Harris showed that in the early twentieth century many suburbanites had moved to suburbs specifically to dodge urban municipal regulations and forego services like sidewalks and sewers, in order to keep their housing costs, including their property tax bill, low.[32] The Etobicoke neighbourhood of Alderwood was a low-cost housing area like this. In southwest Etobicoke, it was subdivided for housing in 1918 and 1920. Residents who purchased the lots built “tar paper shacks” to live in at first.[33] If roads were a good measure of residents’ stance on civic expenditures, then Alderwood’s residents were very cost-conscious. Violet Holroyd, who lived in the neighbourhood in the 1920s, described the area’s crude roads: “In spring…impassable. Having no proper road beds, the melting snow and spring rains turned them into deep ruts and mud holes. In summer…turned to dust. During the winter, in the absence of snowploughs, snow blocked.”[34]

Harris does not mention schools in places like Alderwood in his otherwise far-reaching description of services in pre-war working-class suburbs.[35] However, Alderwood’s educational services were modest, like its other civic infrastructure, and like the school services in many other similar Toronto suburbs.[36] Its schools certainly were less elaborate than the city’s.[37] Alderwood in 1949 had two small brick schools that were several decades old; 487 pupils, all in elementary grades, and twenty-three teachers.[38] Ratepayers had exercised their right to decline to join the township high school board (probably to save on taxes). Consequently, Alderwood youth lacked guaranteed free access to Etobicoke’s only high school in the village of Islington.[39] Prior to school board consolidation in 1949, school governance in Etobicoke was hyper-local, which enabled areas like Alderwood to tailor expenditures and services to their residents’ desires.[40] Public School Section no. 16 (Alderwood) was one of about a dozen distinct school boards in Etobicoke that served the children of public school supporters for approximately grades 1–8.[41]

Figure 2

Figure 3

Rexdale Public School [Etobicoke], photographed in 1955 by V. Salmon.

Residents flooding into Etobicoke during this period appear to have been eager to improve education in places like Alderwood. Public school trustees increased dramatically the amount of money that Etobicoke school sections spent as the township transitioned residentially to greater middle-class dominance. Between 1946 and 1949, total operating expenditures across thirteen Etobicoke public school sections more than doubled, rising from $206,000 to $480,000.[42] In 1949, the provincial government consolidated the sections with the previously independent high school board to create a single new school authority, the Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke that took over public schools in 1950.[43] By 1954, the consolidated Etobicoke Township board of education was spending $2.6 million on operating costs, a four-and-a-half-fold increase over school section spending in 1949.[44]

The growing Etobicoke public school expenditures described above must be put into perspective. Population increase in the township, and the youngest baby boomers entering school for the first time, enlarged school attendance considerably.[45] So too did greater numbers of teenagers, who began to stay in school longer as the opportunity and benefit of doing so increased. Thirty-eight per cent of fifteen- to nineteen-year-olds in Ontario were in school in 1946. Already by 1955, that figure had risen to 51 per cent, though the real explosion in high school participation rates still lay ahead.[46] The nascent Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke had an average daily attendance (ADA) of approximately 4,800 pupils in 1949. By 1954, ADA was 12,400.[47] There were provincial legislative grants (direct transfers from the province to school boards) to support local education; however, these were not a great help. The province increased the grants considerably in 1945, but they soon began to slide backwards yearly through to 1950.[48]

The developments just described required more spending in their own right. However, expenditures of the Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke local public schools outpaced attendance growth considerably, exceeded inflation, and did far more than merely compensate for the diminishing provincial grants.[49] The consolidated public school board’s nearly 450 per cent spending increase from 1949 to 1954 was accompanied by (only) a 158 per cent increase in ADA. In other words, both spending and enrolment grew, but spending grew much more quickly. Looking back from 1956, the Etobicoke Civic Advisory Committee observed substantial upturns in per-pupil capital costs and instructional expenditures between 1949 and 1954. The Civic Advisory Committee’s calculations show capital costs per elementary pupil (ADA) in Etobicoke rising from $18 in 1949 to $47 in 1954. Secondary school capital costs increased from $32 to $102 per pupil (ADA) during the same period. Elementary instructional expenditures went up from $82 per pupil (ADA) in 1949, to $131 in 1954. The cognates for secondary schools were $149 per pupil (ADA) in 1949, and $200 by 1954.[50]

Spending translated into modernizing service improvements. The Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke raised teacher salaries, built state-of-the-art facilities, and funded new programs. Trustees increased high school teacher salaries from an average of $3,385 in 1949 to an average of $4,464 in 1954; they hiked elementary teacher salaries from an average of $2,494 to $3,575 in the same period. This represented 37 per cent and 43 per cent pay gains, respectively.[51] There were big improvements in school plant as well. (See the contrast between buildings in Figure 2 and Figure 3). For example, the Ontario Association of Architects boasted that the cutting-edge Crestwood Public School, which the Etobicoke board was constructing in 1952, would establish “entirely different standards of design and construction for educational buildings.” Crestwood contained a custom kindergarten room, a teachers’ lounge, a health office, a kitchen, and a playroom that doubled as an auditorium. The building had double-glazed windows, linoleum tile floors, and convection heating. The kindergarten had a radiant-heated floor “so that the children will find it warm for playing, resting or sitting.”[52] The trustees added program frills as well. They started a music program by recruiting a music supervisor, luring Mr. R. McGregor from Ottawa’s Glebe Collegiate for the position.[53] They created six itinerant music teacher positions under McGregor in just three years. The trustees also hired into newly created positions for a reading supervisor, a remedial specialist, a home instruction teacher, a superintendent of public schools, an assistant superintendent, and a supervising principal of high schools.[54]

Paying Public School Taxes and Excluding Those Who Could Not Pay

Modernizing educational services meant levying more taxes. Etobians appear to have been willing to pay the property taxes needed to make service improvements, but only to a point. In Etobicoke during the late 1940s and 1950s, much like in suburban Flint, Michigan, as Andrew Highsmith has shown, and in Johnson County, Kansas, as John Rury has shown, belonging to the suburban community meant desiring educational services and contributing willingly to their costs through higher school taxes.[55] Between 1950 and 1953, local school trustees raised the Etobicoke mill rate (tax rate) on property for public schools from 35.7 to 66.4 mills, nearly doubling the tax rate.[56] However, Etobicoke ratepayers’ willingness to pay school taxes ended abruptly where paying these taxes meant subsidizing low-income renters and the owners of smaller homes. Etobicoke municipal councillors and some ratepayers tried instead to exclude these residents from their community, so that better-off homeowners would not have to make up for shortfalls in the amount of taxes renters and owners of small houses would pay, sums perceived to be insufficient to support their share of educational services. Tillotson has observed that many Canadians in the 1950s accepted paying their income taxes out of their sense of responsibility to be “a fair dealer.” We should not confuse that, she writes, with any “particular commitment to social equality” or feelings of “sacrifice for others.”[57] Etobicoke public school ratepayers were not altruists, either.

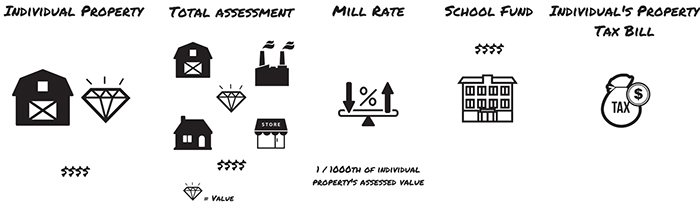

To understand how school taxes contributed to inclusion and exclusion in Etobicoke, especially to understand why ratepayers and their representatives excluded neighbours who were potential free-riders, one must first learn a few school tax basics. The most important lesson is this: the higher the value of individual properties in your municipality, the higher your municipality’s total assessment is likely to be; the higher the total assessment, the lower you can set the property tax rate (called a mill rate) to generate a school fund capable of supporting your schools. The figures below illustrate this relationship. Figure 4 introduces the elements of the public school tax. Total assessment multiplied by the mill rate equals the school fund. Individual property’s value multiplied by the mill rate equals the individual property-owner’s tax bill for schools.

Figure 4

Figures 5 and 6 show how two different districts fare under this system, if they have identical numbers of pupils to educate, but one district has a high total assessment (wealthier), while the other has a low total assessment (poorer). The low assessment district has higher taxes, yet its school fund is no richer than the low tax, high assessment district’s.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Differences between District 1 and District 2 in Figures 5 and 6 would significantly affect individual taxpayers who live there. To raise an identical school fund, District 2 school trustees must set a mill rate of 40 — or four times the rate in District 1. As Figure 7 shows, Farmer Brown, who owns $4,000 of real property in District 2, where the rate is 40 mills, pays $160 in public school taxes. His counterpart in District 1, Farmer Jones, who also owns $4,000 of real property, pays just $40 because the rate in District 1 is only 10 mills.

Figure 7

Historically, low-assessment districts struggled to raise resources because they had to set much higher tax rates. As a result, ratepayers in them often funded their schools less than in districts that had higher assessments. District 2 may wish to raise $100,000 to put its schools on equal footing with District 1, but Brown and the other residents cannot afford the 40 mill rate needed to do that. Instead, school trustees in District 2 set a rate of 30 mills and collect only $75,000 for the school fund. District 2’s schools are less supported. Yet, Brown, who sends his children to a school that has less funding than Jones’ children’s school, is still paying school taxes (now $120, not $160) that are much higher than Jones’ ($40). It matters greatly who your neighbours are under such a system. The more their properties are worth the better, because then you will pay lower taxes and have better funded schools.

Etobicoke residents and municipal politicians understood this perfectly well at mid-century. They took efforts to exclude working-class and poorer neighbours who would occupy properties that would be assessed at a lower value and would drive the Etobicoke total assessment down and the public school mill rate up.[58] They took measures to ensure that Etobicoke would end up like District 1 in the hypothetical case above, and not like District 2. Early examples of those exclusionary measures involved federal government housing projects. Wartime Housing Limited (WHL), and later the CMHC, completed or planned projects of this type in Etobicoke from 1946 and 1948.[59] There were two types of dwelling in WHL/CMHC projects: privately owned houses that the government helped Second World War veterans to finance, and rental units on land that the federal government continued to own. By February 1946, WHL had participated in building just over 200 veterans’ houses near Royal York and the Queensway in the township. Ratepayers living in one of the pre-consolidation Etobicoke school boards, called Public School Section No. 15 (Queensway), where the veterans’ houses were located, anticipated having to cover a shortfall of school tax revenues. This was because the veterans’ homes, which were small, consequently had a low assessed value compared to other Queensway residences, and their owners would thus contribute less than other homeowners in school taxes. The other Section No. 15 ratepayers also worried about paying for what the section’s representatives claimed was a higher number of schoolchildren per household in the veterans’ housing than in the rest of the school section. Township council later estimated that the WHL veterans’ houses would add a substantial 36-mill increase to School Section No. 15 ratepayers’ school tax bill.[60] This would have more than doubled their public school taxes, pushing their rate from 25.6 to 61.6 mills.[61]

Etobicoke Township reeve (mayor) Frank Butler rushed to defend other ratepayers of School Section No. 15 against the veterans. He demanded the federal government, whose program had financed the veterans’ houses, pay for a new ten-room school for the Queensway. If it did not commit to that, Butler threatened to push veterans’ housing free-riders off the school section’s education tax bill, so that the veterans would pay the true and full cost of education themselves. “We will set up these homes as a separate school section and levy to them the entire cost of educating the children. … The rate would be prohibitively high.”[62] Butler followed through. Etobicoke Township council used the authority the School Act gave it to pass a township bylaw severing the new Queensway subdivisions from School Section No. 15. The township created a new School Section No. 17, which only contained the veterans’ housing projects.[63] Elected officials in another metropolitan Toronto suburb, North York, also threatened to create school sections that contained only federal veterans’ housing. Toronto’s mayor, Robert H. Saunders, accused Etobicoke and North York of acting “against the whole spirit of education.” Reeve Butler retorted, “we stated that we would provide educational facilities for veterans’ children in our districts. We did not say who would pay for those facilities.”[64] For months, Butler and the rest of Etobicoke council held out.[65] Finally, in October, they relented. They reversed the bylaw that had severed School Section No. 15 and created No. 17.[66] The historical evidence does not say what changed the council’s mind, nor whether Ottawa paid up or the Etobicoke politicians surrendered for another reason.

Then there was the proposed rental housing on federal land. The federal government would not pay taxes on its rental homes, as it has always been exempted from property tax. Instead, the federal government promised to compensate Etobicoke with tax replacement payments. David Mansur, the CMHC head, in 1948 vowed yearly federal payments of $70 per rental house to municipalities in lieu of property taxes to cover municipal and educational services. In the view of Toronto’s suburban reeves, and in some residents’ view, the federal renters would be free-riders: the federal payments Mansur promised municipalities too little to fully cover the cost of the services the renters would use, educational costs not least of all. The reeves wanted nearly double Mansur’s offer, $130 per rental house yearly to cover services, and threatened not to sign the agreement until they got a larger amount.[67]

Here was a situation that repeated frequently in the period this article examines: Etobians were willing — perhaps even eager — to pay more school taxes to improve schools for themselves. They were unwilling to pay them, as a sacrifice, to cover the cost of educating poorer residents whose school taxes did not stretch as far as theirs did. Reeve Butler, township council, federal representatives like Mansur, and School Section No. 15 ratepayers were engaged in the kind of dialogue that Heaman has described between rich and poor citizens and the state about the distribution or redistribution of wealth through taxation. The municipal arena was often where these contests had their highest stakes, because municipalities were so heavily involved in direct taxation (of property and income) and because they taxed to redistribute wealth, often to redistribute it from the poor to the rich, Heaman notes.[68] The School Section No. 15 ratepayers and their representatives, like Reeve Butler, spoke in words and actions. They acted to exclude their unwanted neighbours in a highly public and visible manner: they municipally divorced them. Opposition to federal housing projects, and the school costs they brought, was not isolated to areas around Toronto, either, also reaching suburbs like Burkeville in Vancouver.[69]

Etobians shoved away all sorts of perceived free-riders and tax-eaters in the late 1940s and early 1950s. More often than not, these would have been poor and working-class residents, or future residents, who were presented partly or fully as not belonging. They were presented like this because the school taxes they would contribute would be insufficient to cover their share of educational services in an Etobicoke public school system that was expanding and modernizing.[70] The local Etobicoke Guardian newspaper in 1953 railed against a proposed social housing project, and against doubling-up and illegal basement sublets.[71] They all posed the same problem of inadequate tax revenue against educational costs. “A number of people have expressed the opinion,” Guardian columnist Edna Harris wrote about two families doubling-up in a single home taxed just once for schools, “that the load of paying education expenses is not fairly distributed, [sic] [W]here two families are located in one home and both are sending children to school, they should be paying equal costs toward education.”[72] Gerry Daub, a columnist who covered Alderwood for the Guardian, said that he had received “several calls” with complaints about apartments in basements “and similar subletting.” Dividing a home and subletting it like this was illegal in Etobicoke, and therefore the sublet was not directly taxable. “The argument here,” Daub continued, “is that while the property owner subletting pays no more to the upkeep of education costs than the single-family property does he has the extra revenues.” Daub then estimated that families occupying sublets were sending Etobicoke public schools some 150 children, costing the system, by his estimate, $180,000 yearly. His claim was that these children’s families contributed nothing in the form of school taxes. “It is one of the reasons our tax bill on Eucation [sic] keeps climbing.”[73]

School tax affected housing in the post-war period. Etobicoke’s educational expansion policy, which called for a threshold of tax support that only wealthier ratepayers would reach, predetermined what type of housing the township would allow people to build and for whom.[74] Given the affordable housing shortages of the immediate post-war period, which people at the time and historians since have commented on, and which did not fully abate until around 1951, the exclusion from Etobicoke Township of housing for poor and working-class families was significant.[75] There were no protests against the school costs that owners of larger homes would create, because people took it for granted that these homeowners would pay enough in taxes to cover the educational services they would use. Social work professor Albert Rose writes about Toronto in this period: “This was the era of the glorification of home ownership as the mark of assumption of individual and civic responsibility for family heads.”[76] Owners of larger homes belonged in post-war suburbs as valued residents and taxpayers. Other owners such as the veterans and renters of all sorts were excluded as free-riders. As Tillotson writes, “Because tax is always about contributing to a collectivity, tax talk and tax practice provide opportunities for marking inclusion or exclusion.”[77] This was certainly true in mid-twentieth-century Etobicoke.

Shoring Up the School Tax Assessment Base

Excluding owners of smaller homes and renters from the township was a way to shore up the tax assessment base in Etobicoke against lower property values. Maintaining a rich total assessment, composed of higher value properties, kept the school and municipal tax rate down for homeowners. Shoring up the base kept the tax rate down, even as Etobians taxed and spent liberally to expand and modernize schools. (See Figures 4 to 7 for a reminder of how this worked). Defending the higher total property assessment base was the Etobicoke Township planning board’s job, perhaps its main responsibility in fact. As I showed earlier in this article, the planning board practised a defensive exclusion when it zoned Etobicoke and developed rules about land uses, dwelling sizes, and construction materials. These rules favoured dwellings that were larger over smaller ones and homeowners over tenants. The planning board did formally and technically the same sort of thing residents did informally and politically when they pushed out free-riding owners of small homes and renters. Both technical and political exclusion helped protect Etobicoke’s high total assessment against declining property values, something that observers at the time comprehended. Prominent housing reformer Humphrey Carver remarked in 1948 that each Toronto municipality has “sought to attract those building enterprises whose high assessment would increase the tax revenue and has resisted any kind of development which would cost more to service than it yielded in taxes.” He continued: “specifically it has been the ambition of municipal councils to obtain new industries and large houses and to exclude low-cost and low-rental housing.”[78] The Civic Advisory Council of Toronto observed in 1949 that, by “passing by-laws fixing minimum sizes for houses,” some Toronto area municipalities successfully increased their assessment and lowered their “educational tax rate.”[79]

Obtaining new industries was the final piece of the public policy puzzle that Etobicoke’s planning board fit into place to shore up the assessment. Companies paid considerable public school taxes from property tax levies on their factories, warehouses, and other facilities. The 1947 township plan set aside ample room for industrial zones and boasted about companies that had already chosen Etobicoke for their operations, such as the Noxzema Chemical Company, asbestos tile maker Flintkote, and the Aluminum Company of Canada (later Alcan). Their property taxes contributed to funding public school expansion and improvement while removing some of that burden from homeowners.[80] In 1954, Etobicoke’s reeve, Bev Lewis, remarked that thanks to the planning board, Etobicoke had achieved “a balanced assessment” of homes and industries that made other Toronto-area municipalities jealous.[81] The planning board also used the town plan and zoning bylaws to place buffers, like a green belt, between industries and the highest valued Etobicoke homes.[82] Residents of places like Humber Bay and the Queensway discovered that the planning board would let industry encroach on their homes and schools, but not on wealthier parts of Etobicoke like Kingsway Park, to keep residential taxes down.[83]

Working-Class Residents and Farmers Respond

Residents of Etobicoke’s historically working-class subdivisions such as Alderwood, and the township’s farmers, responded to their community’s transformation into middle-class dominated suburban space. One sign of that response was their efforts to negotiate the terms of school board consolidation. Consolidation threatened to deprive them of local control of their schools, not least of all their ability to control expenditures and taxes, while also potentially imposing a hefty tax burden on them. However, Alderwood residents and farmers, as groups, responded slightly differently to consolidation.[84] Ontario’s educational experts in the late 1940s and early 1950s supported consolidating the province’s thousands of small section school boards into larger school districts to improve services and create efficiencies.[85] Under pressure from the province to consolidate, Etobicoke Township councillors in 1949 asked Charlie Millard, a Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) member of provincial parliament who represented Etobicoke, to introduce a private member’s bill consolidating the township’s public school authorities. Millard’s bill united more than a dozen previously autonomous public school sections and Etobicoke’s single high school board into the new Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke.[86]

In consolidation discussions, Alderwood school section representatives initially opposed being joined to other Etobicoke public school sections, the Globe and Mail reported, “on the grounds [that Alderwood] had no representation in council and would find it equally difficult to obtain representation on the new board of education.”[87] Under the school section system, Alderwood had its own school board and its trustees had considerable latitude to set expenditures and the school tax rate. As we saw earlier, Alderwood school trustees were a thrifty bunch. They had not joined the township high school district, probably to save on taxes. Alderwood’s spokespersons probably feared that the community would have no representation on a consolidated school board that might be more inclined to spend, imposing increased taxes the residents they represented could not afford. (They would have been partially correct, because, as we have seen, the consolidated board taxed and spent enthusiastically). In fact, Millard’s bill proposed that, like township council, the Board of Education be elected at-large with no guarantee that any area of the township would win representation. To correct this, Gerald Daub, president of the Alderwood Home Owner’s Association (and an Etobicoke Guardian columnist concerned about school taxes, as we learned earlier), and Alexander King, a trustee on the pre-consolidation School Section No. 16 (Alderwood) board, pushed for a change to Millard’s private member’s bill. They asked for the consolidated board to be elected on the ward system, instead of at-large, to guarantee a seat at the table for Alderwood.[88] They partly achieved this aim when a Liberal MPP moved a friendly amendment to Millard’s bill to require that only the first trustee election for the consolidated board be at-large. The amended bill, which the provincial parliament passed, promised a plebiscite in Etobicoke on the ward system to occur no later than 31 December 1950.[89]

Daub and King’s fears about Alderwood losing its voice, and about its working-class homeowners being overwhelmed by new taxes they could not afford, went unfulfilled. The top vote getter in the 1949 at-large school board elections, it turned out, was none other than Alderwood’s Alexander King.[90] Etobicoke public school board electors subsequently chose wards for school board elections in the 1950 plebiscite. In fact, voters approved wards for township council elections as well, in 1953. The adoption of wards, as well as the boundaries decided upon, guaranteed Alderwood and farmers some representation as Etobicoke changed. Northern Etobicoke, still largely farmland, was given its own ward (Ward 4), even though it had a much smaller population than the other three wards. It would elect only one councillor, however, while the others would elect two each.[91] The remaining ward boundaries carved the southern half of the township, everything south of Richview Side Road (today called Eglinton Avenue West), into three wards with east-west boundaries.[92] As for Alderwood residents’ ability to afford more taxes, in the immediate post-war period, working-class wages were rising. This pushed many on low incomes into the middle group.[93] Working-class Etobicoke residents had more money and therefore less to fear from unaffordable taxes than during the pre-war period. Post-war suburbs were “unaffordable” for only a diminishing number of working-class families whose wages bucked the trend and did not increase.[94] And for that matter, working-class homeowners who remained in Etobicoke got better schools, which wealthier homeowners partly subsidized for them (begrudgingly).

The township’s transformation affected Etobicoke’s farmers differently than established working-class homeowners. Farmers also responded to school board consolidation differently. School Sections Nos. 4 (Richview), 6 (Highfield), 7 (Smithfield), and 9 (an inter-county union school section of Toronto Gore, Etobicoke, and Vaughan) served mainly farms.[95] Under consolidation, Etobicoke farmers in these sections faced skyrocketing school tax rates, which threatened to send farmers’ tax bills soaring much higher than homeowners’. Before consolidation, Etobicoke rural public school trustees had set very low tax rates for elementary schools: 3 mills in Richview; 9 mills in Highfield; 12 mills in Smithfield. Ratepayers in all three sections paid an additional charge of 4.3 mills each for county high schools. This compared to much higher rates in other Etobicoke public school sections that served housing subdivisions; rates that before consolidation ranged from 15.3 mills to as much as 34.9 mills for elementary schools, plus an additional 4.3 to 6.8 mills for high schools.[96] Farmers typically set the rates low because farmers owned a lot of real property, and it was real property, not income or other wealth, that was taxed for schools. But just because farmers had a lot of real estate, this did not make them richer than other people in the township, nor for that matter did it give them cash liquidity to pay their school taxes.[97]

Recognizing farmers’ unique situation, Millard’s consolidation bill placed a special though limited cap on increases to school taxes applying only to farmers living in sections nos. 4, 6, 7, and 9. In these sections, the rate of any taxpayer owning and cultivating a single property of at least forty-five acres was capped. The Millard bill prevented the consolidated school board from taxing these farmers at a rate greater than 1 mill to construct new elementary school buildings in other parts of the township. The farmers’ taxes for other public school purposes, however, were not capped. The bill did not cap their rate on elementary school operating expenditures, which were set to rise high as the new Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke added frills and boosted teachers’ salaries. The bill did not protect farmers from tax increases to pay for high school operating costs either, nor from high school capital costs. The cap expired the moment the consolidated board took on capital debt to renovate or expand an elementary school to serve any of the capped sections.[98] On the eve of consolidation in 1949, Richview, Highfield, and Smithfield were still operating one-room schools that would shortly be out of place in the modernizing consolidated Etobicoke system. Parts of the Smithfield school dated back to 1874 and the building still lacked indoor plumbing in 1949.[99] (See Figure 3). The consolidated board announced almost immediately after it was formed a plan to close the Smithfield school and bus students to the village of Thistletown, still in the township but about two kilometres away.[100] Smithfield residents opposed closing their school, a position that residents of Highfield adopted also when the board slated their school for closing around the same time.[101] There was the matter of protecting their 1-mill cap, which expired effectively when their schools closed and the board spent money to accommodate their children elsewhere. There is evidence, as well, that these Etobicoke farmers also did not want to surrender their one-room schools because they did not yet want to give up their way of life as their community was transformed before their eyes into a modern suburb. Gidney writes that under consolidation in Ontario, “local people remained jealous of local control and the closing of a schoolhouse might deprive a small community of its only public institution.”[102] Smithfield residents opposed the school board shuttering their schoolhouse because, as board minutes record, “there is a certain sentiment attached to the old school [at Smithfield] and it is always difficult for some people to make the break.”[103] The board succeeded in closing the school four years later, in 1953, with rural Etobicoke residents still opposed.[104] When one-room schools eventually closed, the old ways in education were erased from the suburbanizing landscape. Like farms, they no longer seemed to belong.

By 1953, the public school tax rate for Etobicoke farmers had climbed steeply. They now paid a public elementary school rate of 39.1 mills, plus a high school rate of 16.8 mills, giving them a total rate of 55.9 mills. This was the capped rate. It was close to the 66.4 mills that Etobicoke’s non-farmers were charged.[105] The contrast of pre-consolidation school tax rates for farmers of 7.3 to 16.3 mills against a 55.9 mill rate, which is more than six times higher in some cases, is stark. For some farmers, this meant that they could count on one hand the number of years it had taken for their tax bills to grow by 650 per cent.

The farmers’ salvation was sub-dividers’ demand for their land. Many families who had owned farmland in the township for generations sold it for suburban development in this period. One group of just nine Etobicoke farmers disposed of 600 acres in 1953, enough to build 3,000 homes, 60 walk-up apartments, a shopping mall, and an industrial park.[106] In this final way, as well, changing school taxes contributed to the transformation of Etobicoke as suburban space, as farmers sold property to sub-dividers to avoid them.

Conclusion

People and policies dramatically transformed Etobicoke’s suburban landscape in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Similar to what occurred in many Toronto suburbs, as urban historians have shown, Etobicoke’s farms and older, more eclectic working-class housing subdivisions gave way to what Harris memorably described as “creeping conformity,” much more middle-class, professionally-built tract housing.[107] Federal legislation enabling borrowers to get long-amortizing mortgages, municipal planning and zoning bylaws, and building codes enabled the changes. And though Canadian urban historians have been slow to recognize it, public schools and school taxes played a big part in this mid-century transformation. The public school system’s modernization and expansion changed Etobicoke’s political economy and physical landscape, contributing to preferences for higher valued residences and for more industry and businesses. Public school taxes levied against these properties paid for modernization, helping school trustees transform the Etobicoke system from one-room or modest schools to more elaborate educational infrastructure. Public school taxes were also the largest item on the township tax bill. The ability to pay them helped to create belonging and exclusion in the changing suburb. This affected the types of residences Etobians allowed to be built, and the residents they allowed to inhabit their community. Middle-class homeowners wanted to expand and modernize school infrastructure, but they were only willing to pay for this for themselves and people they deemed to be like them. They pushed away renters, basement apartment dwellers, families that doubled up, owners of small houses, and social housing residents, seeing all of these as school tax free-riders. Township council and the planning board designed the township plan, the zoning bylaw, the building code, and the residential-industrial mix to leverage a higher total property tax assessment into better schools at a lower rate for Etobicoke homeowners. Working-class residents of established neighbourhoods and farmers tried to protect their interests as taxpayers against change. Both groups focussed efforts on the school consolidation bill. Alderwood school trustees and homeowners pushed successfully for a ward system to give them representation on the school board and township council. Farmers managed to protect themselves from some tax increases for a time, but, in the end, they were swamped by a rising public school mill rate. Established working-class residents could afford the taxes and held on. Farmers sold and moved on. Farms disappeared from the changing suburban landscape.

School taxes had more implications, which lie beyond this article’s scope and that I have not discussed. Quality public schools increase homeowners’ property values. Not only that, they enhance their students’ educational outcomes. Suburban public school quality, costs, and taxes drove the history of post-war social mobility in ways that Canadian historians could further examine.[108] Public school taxes were central to Toronto’s metropolitan political history during the period of this study, and slightly after it as well. Residents of less well-off suburbs in Toronto, like Scarborough, lost ground in the late 1940s and early 1950s against richer Etobicoke, where schools were better funded at lower tax rates.[109] This was such a significant problem that the province formed the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto in 1954 to try to more evenly and justly redistribute tax revenues for schools and other services across metropolitan borders. Creating equality of educational opportunity and fairly balancing its costs in the form of school taxes, along with economic development needs, were the strongest driving forces behind “Metro.”[110] The “new suburban history” calls on historians to pay much greater attention to metropolitan contexts, as individual suburbs like Etobicoke were in a state of dynamic political and economic tension with suburban neighbours and the city, all struggling with one another over power and resources.[111] As Ansley Erickson convincingly shows in Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits, schools were “a force in the making of the city and metropolis rather than … solely a recipient of urban dynamics.” The metropolitan historical context and its educational dimension especially, Erickson argues, also shows just how deeply race and class affect suburban history. Suburbs are inseparable from metropolises, where race and class divide politics and resources (like educational funding and opportunity).[112] Indeed, the history of school taxes is also related to the history of racial discrimination in Canada in ways that historians have not yet fully explored. The sort of prejudice against tax eaters that excluded lower-income residents in Etobicoke was expressed as racial prejudice in other, similar historical contexts. Several historians have shown how what Camille Walsh calls “taxpayer citizenship” bred a type of belonging that, in the United States, converged with white supremacy. “Ultimately,” Walsh writes, “by linking the right to education to taxation, these white ‘taxpaying citizens’ facilitated an idea that public school resources should legitimately be linked to the tax payments and taxable wealth of a person or a racialized community.”[113] Racialization of school taxes was not an American phenomenon only. The British Columbia government, in 1876, passed a poll tax to support the province’s public schools, instead of using a property tax for this. The poll tax fell most heavily, and intentionally so, on Chinese residents, who owned less taxable property, redistributing an estimated $17,000 from them to whites. Premier A.C. Elliott’s government chose the poll tax for just this reason, because, Heaman writes, “Elliott explained that while special Chinese taxes would be unconstitutional, the school tax would ‘catch’ the Chinese” — and would force Catholics to also “pay their share.”[114] I found no evidence for this sort of racialization of school taxes in Etobicoke in the period I examined, though it is not out of the question that it occurred then or at another time. Educational and urban historians — and tax historians too — have much more to investigate together.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a National Academy of Education/Spencer Postdoctoral Fellowship (2017). The author thanks the NAEd and the Spencer Foundation. He also thanks Karen Brooke, Jack Dougherty, R.D. Gidney, Michael Leblanc, W.P.J. Millar, three anonymous peer reviewers, and the JCHA editorial board for their comments on versions of this article.

Biographical note

JASON ELLIS is a historian of education and associate professor in the Department of Educational Studies at the University of British Columbia.

Notes

-

[1]

They have often disregarded money altogether. Exceptions include R.D. Gidney and W.P.J. Millar, How Schools Worked: Public Education in English Canada, 1900–1940 (Montreal & Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2012), 151–96; Peter N. Ross, “The Free School Controversy in Toronto, 1848–1852,” in Education and Social Change: Themes from Ontario’s Past, eds. Michael B. Katz and Paul Mattingly (New York: New York University Press, 1975), 57–80; Wendie Nelson, “‘Rage against the Dying of the Light’: Interpreting the Guerre des Éteignoirs,” Canadian Historical Review 81, no. 4 (December 2000): 551–581; Helen Brown, “Financing Nanaimo Schools in the 1890s: Local Resistance to Provincial Control,” in School Leadership: Essays on the British Columbia Experience, 1872–1995, ed. Thomas Fleming (Mill Bay, BC: Bendall Books, 2001), 199–220, and Paul Axelrod, Scholars and Dollars: Politics, Economics, and the Universities of Ontario 1945–1980 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982).

-

[2]

Some Canadian historians of education have drawn theoretical insights from urban history. See Jean Barman, “‘Knowledge Is Essential for Universal Progress but Fatal to Class Privilege’: Working People and the Schools in Vancouver during the 1920s,” Labour/Le Travail 22 (Fall, 1988): 9–66, and Helen Harger Brown, “Binaries, Boundaries, and Hierarchies: The Spatial Relations of City Schooling in Nanaimo, British Columbia, 1891–1901” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 1998).

-

[3]

Jack Dougherty, “Bridging the Gap Between Urban, Suburban, and Educational History,” in Rethinking the History of American Education, eds. William J. Reese and John L. Rury (New York: Palgrave, 2007), 245–59.

-

[4]

Matthew D. Lassiter, “Schools and Housing in Metropolitan History: An Introduction,” Journal of Urban History 38, no. 2 (2012): 195–204. See also, Andrew R. Highsmith, Demolition Means Progress: Flint, Michigan, and the Fate of the American Metropolis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 103–20; Jack Dougherty, “Shopping for Schools: How Public Education and Private Housing Shaped Suburban Connecticut,” Journal of Urban History 38, no. 2 (2012): 205–24; Karen Benjamin, “Suburbanizing Jim Crow: The Impact of School Policy on Residential Segregation in Raleigh,” Journal of Urban History 38, no. 2 (2012): 225–46; Ansley T. Erickson, “Building Inequality: The Spatial Organization of Schooling in Nashville, Tennessee, after Brown,” Journal of Urban History 38, no. 2 (2012): 247–70.

-

[5]

Richard Harris, Unplanned Suburbs: Toronto’s American Tragedy, 1900 to 1950 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996). This transition, though not widely known, was very common in Canada and the United States; Toronto was not an exception. See also Richard Harris, Creeping Conformity: How Canada Became Suburban, 1900–1960 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 119–74, and Becky Nicolaides, My Blue Heaven: Life and Politics in the Working-Class Suburbs of Los Angeles, 1920–1965 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 3–6.

-

[6]

See also, Lassiter, “Schools and Housing in Metropolitan History,” 196.

-

[7]

For comparison, the second biggest item on their property tax bill — roads and bridges, no less — accounted for just nine cents. “Permanent Basis; 15 New Police,” Etobicoke Guardian (2 April 1953), 1–2. This article is concerned with public school taxes. Catholic families could send their children and direct their school taxes (except the high school portion) to separate schools. Those schools and taxpayers are not subjects of this article.

-

[8]

E.A. Heaman, Tax, Order, and Good Government: A New Political History of Canada (Montreal & Kingston: Queen’s University Press, 2017); Shirley Tillotson, Give and Take: The Citizen–Taxpayer and the Rise of Canadian Democracy (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017); David Tough, The Terrific Engine: Income Taxation and the Modernization of the Canadian Political Imaginary (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018).

-

[9]

Heaman, Tax, Order, and Good Government, 5; Tillotson, Give and Take, 12–13; Tough, Terrific Engine, 7.

-

[10]

R.D. Gidney, From Hope to Harris: The Reshaping of Ontario’s Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 28–30, 55–8.

-

[11]

Civic Advisory Council of Toronto, The Committee on Metropolitan Problems, First Report: Section Two (Toronto: Civic Advisory Council, 1950), 32A.

-

[12]

Esther Heyes, Etobicoke — From Furrow to Borough (Etobicoke: Borough of Etobicoke, 1974), 138–48; Robert Paterson, “The Development of an Interwar Suburb: Kingsway Park, Etobicoke,” Urban History Review 13, no. 3 (February 1985): 225–35.

-

[13]

Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 141–232.

-

[14]

Violet M. Holroyd, Alderwood: Where the Alders Grew (Orillia, ON: Printing Plus, 1993); Robert A. Given, Etobicoke Remembered (Toronto: Pro Familia, 2007), 64–74, 179–82.

-

[15]

Harris, Creeping Conformity, 119–23; John Bélec, “Underwriting Suburbanization: The National Housing Act and the Canadian City,” The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 59, no. 3 (2015): 342–6.

-

[16]

Etobicoke Historical Society Collections, E.G. Faludi, A Plan for Etobicoke: Prepared by E.G. Faludi, Town Planning Consultants Limited, for the Etobicoke Planning Board (n.p., c.1947), 3.

-

[17]

Richard White, Planning Toronto: The Planners, Their Plans, Their Legacies, 1940–80 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016), 44–5, 65–7.

-

[18]

E.G. Faludi, A Plan for Etobicoke; City of Toronto By-law Status Registry, Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 6963, A By-law to appoint a subsidiary Planning Board pursuant to the provisions of The Planning and Development Act, 1946 (15 November 1946), http://app.toronto.ca/BLSRWEB_Public/HomePage.do, <viewed 26 May 2020>.

-

[19]

City of Toronto By-law Status Registry, Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 7673, Restricted Area (Zoning) By-Law of The Township of Etobicoke (11 April 1949), http://app.toronto.ca/BLSRWEB_Public/HomePage.do, <viewed 26 May 2020>. Etobicoke added an additional zone in 1951. City of Toronto Archives (hereafter CTA), City of Etobicoke Fonds, Series 1086 Etobicoke Planning Board minutes and reports, Seventh Meeting, 25 March 1951, 5; E.G. Faludi. Township of Etobicoke. 1:24,000 map. Etobicoke: Etobicoke Planning Board, 1949.

-

[20]

Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 7673.

-

[21]

Harris, Creeping Conformity, 130.

-

[22]

Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 7673, §§ 9.4.2.1.

-

[23]

City of Toronto By-law Status Registry, Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 7673, § 3, and Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 6477, To Regulate the Erection and Provide for the Safety of Buildings (3 April 1944), http://app.toronto.ca/BLSRWEB_Public/HomePage.do, <viewed 26 May 2020>. On building codes, see Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 155–9; Harris, Creeping Conformity, 153–6.

-

[24]

Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 277–9; Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 241–3. See also, Highsmith, Demolition Means Progress, 108–10.

-

[25]

Restrictions applied to such things as the use, design, building materials, and occupants. Kingsway Park had many restrictions on design and materials, but Paterson says there is no evidence that the Home Smith and Company, which developed Kingsway Park, applied a racially or religiously restrictive covenant against residents, though other Canadian suburbs did, such as Hamilton’s Westdale. Nevertheless, Kingsway Park remained quite restrictive into the post-war period. The price of houses there was a form of income screening that excluded most non-British, non-Protestant residents in an area that the Home Smith and Company billed as “A Little Bit of England Far From England.” Paterson, “The Development of an Interwar Suburb,” 228–33. See also Patrick Vitale, “A Model Suburb for Model Suburbanites: Order, Control, and Expertise in Thorncrest Village,” Urban History Review 40, no. 1 (2011): 46–9, who reached a similar finding about a subdivision of Etobicoke – Thorncrest.

-

[26]

Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 258–63.

-

[27]

John Bélec, Richard Harris, and Geoff Rose, “The Federal Impact on Early Postwar Suburbanization,” Housing Policy Debate 28, no. 6 (2018): 864–6.

-

[28]

He defines “new” as built in the preceding decade. Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 259.

-

[29]

Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 254–63. See also Larry McCann, “Suburbs of Desire: The Suburban Landscape of Canadian Cities, c. 1900–1950,” in Changing Suburbs: Foundation, Form and Function, eds. Richard Harris and Peter J. Larkham (London: Routledge, 1999), 111–45.

-

[30]

Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Canada, CS64–501, Building Permits, 1951–56 (Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics, 1957), 64–8.

-

[31]

Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 1945 Annual Report of Municipal Statistics (Toronto: T.E. Bowman, 1946), 19; Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 1954 Annual Report of Municipal Statistics (Toronto: Baptist Johnson, 1954), 1.

-

[32]

Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 109–67. See also Heaman, Tax, Order, and Good Government, 292–4.

-

[33]

Esther Heyes, Etobicoke — From Furrow to Borough, 129; Given, Etobicoke Remembered, 114.

-

[34]

Holroyd, Alderwood, 2.

-

[35]

Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 141–67.

-

[36]

Silvio Sauro, A Celebration of Excellence to Commemorate the 25th Anniversary of the Etobicoke and Lakeshore District Boards of Education, 1967–1992, and the dissolution of the Etobicoke Board of Education, May 1949–December 1997 (Etobicoke: Etobicoke Board of Education, 1997), 1–33.

-

[37]

For comparisons of city, town, suburban, and rural school conditions in this period in Ontario, see Gidney and Millar, How Schools Worked, 80–110, and Maxwell A. Cameron, The Financing of Education in Ontario, Bulletin No. 7 of the Department of Educational Research (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1936), 80–170.

-

[38]

Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Schools and Teachers in the Province of Ontario, Part I, Public and Separate Schools, November, 1949 (Toronto: Baptist Johnson, 1949), 451. The figure of 487 pupils records “average [daily] attendance” (ADA). Contemporary sources, and historians, tend to use ADA as the most accurate proxy for school enrolment available in records for this period. See Gidney and Millar, How Schools Worked, 16–19.

-

[39]

Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Schools and Teachers in the Province of Ontario, Part II, Collegiate Institutes, High Schools, Continuation Schools, Vocational Schools, Normal Schools, and Technical Institutes, November, 1949 (Toronto: Baptist Johnson, 1949), 218.

-

[40]

A.C. Lewis, Handbook of the Administration of Education in Ontario, 7th ed., Educational Research Series No. 1 (Toronto: Department of Educational Research, Ontario College of Education, University of Toronto, 1954), 20–6; Gidney, From Hope to Harris, 10–11.

-

[41]

See Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Schools and Teachers in the Province of Ontario, Part I, 1949, 446–51, 694–701, and Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Schools and Teachers in the Province of Ontario, Part II, 1949, 218.

-

[42]

Calculated from Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 1945 Annual Report of Municipal Statistics, 20; Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 1949 Annual Report of Municipal Statistics (Toronto: Baptist Johnson, 1950), 15.

-

[43]

Civic Advisory Council of Toronto, First Report: Section Two, 39; “Warns Etobicoke Board Will Veto School Extensions,” Globe and Mail (15 December 1948), 5. “Etobicoke Elects Seven to First School Board,” Globe and Mail (16 May 1949), 4.

-

[44]

Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 1954 Annual Report of Municipal Statistics, 13.

-

[45]

Douglas Owram, Born at the Right Time: A History of the Baby-Boom Generation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 4.

-

[46]

Gidney, Hope to Harris, 27–8.

-

[47]

CTA, Frank Langstaff Fonds, Etobicoke Civic Advisory Committee, File 33 Education Committee, 1953–57, “Etobicoke Township, Average Daily Attendance, 1949–1954,” from “The Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke, 1956 Budget.” See note 38 for a definition of ADA and its significance.

-

[48]

Robert M. Stamp, The Schools of Ontario, 1876–1976 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), 185; Gidney and Millar, How Schools Worked, 166. Stamp, Gidney, and Millar look at aggregated provincial contributions. It is not known precisely how much provincial grants in Etobicoke changed, though there is no reason to suspect changes in the township were substantially different from anywhere else.

-

[49]

In the period 1949 to 1954, total inflation was 17 per cent. All of the increases referred to earlier exceeded that. Bank of Canada, Inflation Calculator, https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/related/inflation-calculator/ <viewed 26 May 2020>.

-

[50]

CTA, Frank Longstaff Fonds, Series 601 Etobicoke Civic Advisory Committee, File 33 Education Committee, 1953–57, “The Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke Educational Rates – 1956.”

-

[51]

CTA, Frank Longstaff Fonds, Series 601 Etobicoke Civic Advisory Committee, File 33 Education Committee, 1953–57, “The Board of Education for the Township of Etobicoke Educational Rates – 1956.”

-

[52]

“Unusual Design Main Feature of New School,” Globe and Mail (2 February 1952), 3.

-

[53]

Toronto District School Board Archives (hereafter, TDSBA), Township of Etobicoke. Board of Education. Minutes 1950. Jan.–Dec. 17–35. Twenty-Second Meeting, 26 April 1950, 15–16.

-

[54]

“Opened in Unique Ceremony,” Etobicoke Guardian (21 May 1953), 2; “100 New Teachers Engaged and Major Appointments Announced,” Etobicoke Guardian (25 June 1953), 6.

-

[55]

Highsmith, Demolition Means Progress, 112–18; John L. Rury, “Trouble in Suburbia: Localism, Schools, and Conflict in Postwar Johnson County, Kansas,” History of Education Quarterly 55, no. 2 (May 2015): 144–8.

-

[56]

The total is the sum of public elementary and secondary rates. See the yearly bylaws setting the rates for 1950–3. City of Toronto By–law Status Registry, Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 7892, A By–Law to Adopt the Assessment on which the taxes shall be levied for the year 1950, to levy the taxes for the year 1950, and to provide for the collection thereof (13 March 1950); By-law No. 8075 (19 March 1951); By-law No. 8309 (24 March 1952); By-law No. 8614 (26 March 1953), http://app.toronto.ca/BLSRWEB_Public/HomePage.do, <viewed 26 May 2020>. I have not included earlier figures because they varied considerably on account of the existence of so many different public school sections.

-

[57]

Tillotson, Give and Take, 236–7. See also, Tough, Terrific Engine, 116–46.

-

[58]

I have simplified this example considerably to make the explanation easier. For a much fuller account of how this worked in theory, see Gidney and Millar, How Schools Worked, 151–78. For an account of how it worked in practice, see Cameron, The Financing of Education in Ontario.

-

[59]

For the program, see Jill Wade, “Wartime Housing Limited, 1941–1947: Canadian Housing Policy at the Crossroads,” Urban History Review 15, no. 1 (June 1986): 46–7.

-

[60]

“Will Levy Education Costs Etobicoke Gives Ultimatum,” Toronto Daily Star (12 February 1946), 5; “Make Vets’ Homes New School Area,” Toronto Daily Star (28 May 1946), 9.

-

[61]

For the rate in Section No. 15, see City of Toronto By-law Status Registry, Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 6754, A By-law to fix rates of taxation for the year 1946 (25 February 1946), http://app.toronto.ca/BLSRWEB_Public/HomePage.do, <viewed 26 May 2020>.

-

[62]

“Will Levy Education Costs Etobicoke Gives Ultimatum,” Toronto Daily Star (12 February 1946), 5.

-

[63]

“Make Vets’ Homes New School Area,” Toronto Daily Star (28 May 1946), 9; City of Toronto By-law Status Registry, Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 6806, A By-law of the Municipality of the Township of Etobicoke to Divide Public School Section Number Fifteen, Etobicoke, and to Establish a New Public School Section to be Designated Number Seventeen, Etobicoke (27 May 1946), http://app.toronto.ca/BLSRWEB_Public/HomePage.do, <viewed 26 May 2020>.

-

[64]

“Reeve Sees Dual Blow at Municipal Rights,” The Globe and Mail (7 June 1946), 7.

-

[65]

“Flood Control Tri-Township Meeting Topic,” The Globe and Mail (12 June 1946), 4.

-

[66]

City of Toronto By-law Status Registry, Township of Etobicoke, By-law No. 6923, A By-law to Repeal By-law no. 6806 (15 October 1946), http://app.toronto.ca/BLSRWEB_Public/HomePage.do, <viewed 26 May 2020>.

-

[67]

“Deputation to Ask Provincial Aid In Housing Plan,” Globe and Mail (13 February 1948), 4; “If Province Pays Schools, Ottawa Pays Tax Load,” Globe and Mail (9 March 1949), 1; Wade, “Wartime Housing Limited,” 50. Federal and provincial governments do not pay property tax, under § 125 of the British North America Act. William Houston, ed., Documents Illustrative of the Canadian Constitution. The Confederation Act, 1867, and Supplementary Acts (Toronto: Carswell, 1891), 211.

-

[68]

Heaman, Tax, Order, and Good Government, 186.

-

[69]

Wade, “Wartime Housing Limited,” 52.

-

[70]

See Campbell F. Scribner, The Fight for Local Control: Schools, Suburbs, and American Democracy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016), 94–116.

-

[71]

Stanley K. Smith, “Etobicoke Residents Are Aroused; Workers Fear Loss of Last Playground,” Etobicoke Guardian (30 April 1953), 1, 4.

-

[72]

Edna Harris, “The Party Line,” Etobicoke Guardian (18 June 1953), 12.

-

[73]

Gerry Daub, “The Southwest Corner,” Etobicoke Guardian (2 July 1953), 8. It could be argued that the ability to sublet and generate rental income would increase a property’s value along with the owner’s tax bill. To the best of my knowledge, however, this consideration was not raised in the debate in 1953.

-

[74]

Lassiter, “Schools and Housing in Metropolitan History,” 197–201.

-

[75]

Humphrey Carver, Houses for Canadians: A Study of Housing Problems in the Toronto Area (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1948); “Housing Visions Fade; Family of Six in Tent,” Globe and Mail (8 May 1946), 5; Harris, Unplanned Suburbs, 249–52; Wade, “Wartime Housing Limited,” 42–4; James Lemon, Toronto since 1918: An Illustrated History (Toronto: Lorimer and National Museums of Canada, 1985), 90–2.

-

[76]

Albert Rose, Governing Metropolitan Toronto: A Social and Political Analysis 1953–1971 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), 31.

-

[77]

Tillotson, Give and Take, 130. See also, Heaman, Tax, Order and Good Government, 285–6, 320–4.

-

[78]

Carver, Houses for Canadians, 115. See also, Rose, Governing Metropolitan Toronto, 31.

-

[79]

Civic Advisory Council of Toronto, The Committee on Metropolitan Problems, First Report: Section One (Toronto: Civic Advisory Council, 1949), 32.

-

[80]

Faludi, A Plan for Etobicoke, 22–36. See also, “No Legal Status for Cumming Report,” Etobicoke Guardian (12 November 1953), 4.

-

[81]

“Inaugural Night Brings Forecasts of Bright Future,” Etobicoke Guardian (7 January 1954), 1–2.

-

[82]

Faludi, A Plan for Etobicoke, 3. See also, Nicolaides, My Blue Heaven, 22–5.

-

[83]

CTA, City of Etobicoke Fonds, Series 1086 Etobicoke Planning Board minutes and reports, Second meeting, Committee of whole, 12 April 1951, 1; Fourteenth regular meeting, 29 May 1951, 2–3; Fifteenth regular meeting, 5 June 1951, 2–5.

-

[84]

See also Highsmith, Demolition Means Progress, 110–14.

-

[85]

Gidney, From Hope to Harris, 12–13.

-

[86]