Abstracts

Abstract

The Portland Book Festival, originally known as “Wordstock,” is the main annual literary event in Portland, Oregon. It is also an increasingly prominent literary festival in the United States. The branding shift from “Wordstock” to “Portland Book Festival” in 2018 unearths key tensions, hierarchies, subversions, and cultural changes in the communicative and social functions of the Festival. The essay identifies transactional and transformative aspects of the Festival. Bank of America’s festival-naming “title” sponsorship, the partnership of cultural heritage organizations, and Portland place branding offer transactional stability for the Festival, where parties give and get in kind. The Festival’s temporary affective bonds and their social media documentation facilitate transformational experiences that reinscribe hierarchies of centre/periphery. The name change fosters a more democratic and accessible festival experience. This article takes a multimethod approach, triangulating sentiment analysis of tweets from the 2017 and 2018 Festivals, a survey of 2018 Portland Book Festival attendees, and interviews with prominent stakeholders in the Festival rebranding.

Keywords:

- Portland Book Festival,

- literary festival,

- liveness,

- place-based marketing,

- book discovery

Résumé

Le Festival du livre de Portland (Portland Book Festival), appelé Wordstock à sa création, est la principale manifestation littéraire annuelle de Portland (Oregon) et est en voie de devenir l’un des festivals littéraires les plus en vue des États-Unis. Le passage de « Wordstock » au « Portland Book Festival », en 2018, est révélateur des tensions, des hiérarchies, des subversions et des changements culturels à l’oeuvre dans les fonctions communicative et sociale du Festival. Le présent article identifie les aspects transactionnels et transformatifs de ce dernier. D’une part, la présence d’un commanditaire en titre, Bank of America, le partenariat avec des organismes voués au patrimoine culturel et l’image de marque de Portland confèrent une stabilité transactionnelle au Festival, en vertu de laquelle les parties à la fois donnent et reçoivent. D’autre part, les liens affectifs temporaires se créant lors du Festival et la façon dont ils sont documentés sur les réseaux sociaux soutiennent des expériences transformationnelles qui réinscrivent les hiérarchies centre/périphérie. Le changement de nom du Festival favorise une expérience plus démocratique, plus accessible. L’article s’appuie sur une approche multiméthode, par la triangulation d’une analyse de sentiments des tweets publiés en 2017 et de 2018, d’un sondage réalisé auprès des visiteurs de l’édition 2018 et d’entretiens avec diverses parties prenantes au changement d’image du Festival.

Mots-clés :

- Festival du livre de Portland,

- festival littéraire,

- animation,

- commercialisation sur place,

- découverte du livre

Article body

Introduction

The rebranding of the annual literary festival in Portland, Oregon from “Wordstock” (2005–2017) to “Portland Book Festival” (2018–present) signifies the event’s evolution from one that traded upon Portland’s branded weirdness (“Keep Portland Weird,” discussed below) to a self-evident and place‑based festival name. The transformation from “Wordstock” to “Portland Book Festival” pivots the festival from a reference to the iconic, countercultural 1969 music festival (“Woodstock”) to place branding that permits a wider range of signification while still tapping into Portland’s artisanal culture.

In the introduction to this special issue, Squires and Driscoll argue that contemporary book festivals cannot enact a revolutionary version of the carnival because of the essential role that festivals play in the creative economy: “they keep neoliberal publishing economies running.”[1] In agreement with Squires and Driscoll’s claim, this essay aligns with Snyder’s findings that while book festivals are not wholly subversive like the carnivalesque, there are subversive elements of book festivals that exist alongside the more conventional elements. This essay will trace how the Portland Book Festival (PBF) rebranding both activates and dampens elements of the carnivalesque from the point of view of various stakeholders: festival goers, festival organizers, event sponsors, and allied cultural organizations. The authors surveyed a statistically significant number of 2018 Portland Book Festival-goers about the festival name change, and interviewed stakeholders at Literary Arts, the Portland Art Museum, and local small press publishers who exhibit on the Festival’s expo floor.

Specifically, this essay argues that the Portland Book Festival’s carnivalesque features, such as the flattening of celebrity hierarchies and demand-side economic stimulation through $5 “vouchers” redeemable on one day only with any book vendor at the festival, are undergirded by a status quo infrastructure: corporate sponsorship, and events partnership with allied cultural organizations in Portland’s cultural arts district. The essay identifies “transformative” (carnivalesque) and “transactional” (status quo) festival elements that give new application to classic concepts of the carnivalesque as articulated by Bakhtin in Rabelais and His World (1965; translated to English 1968),[2] such as the way socio-economic status and other markers of status are temporarily redrawn in the collective, short-lived experience of attending a festival. Collective identity at the Portland Book Festival bonds people across strata and across physical and digital realms, but stops short of the bawdiness and vulgarity that attracted Bakhtin’s notice in Renaissance festivals. Instead of bawdy/bodily excesses which “reflect the collective leveling culture of carnival” by focusing on sexuality and the “lower stratum” of human life, documentation of physical excess is transposed to book hauls and exclamations of fan devotion.[3] A “book haul” is not a carnivalesque inversion, but almost its opposite: a welcomed commercial excess. Further, tweeted emojis remediate fan feelings into excesses of approbation. The pent-up danger of the carnivalesque Bakhtin describes is here diffused in enthusiasm and pleasure in book fandom, a radical shift from Renaissance carnivalesque’s transgressive and threatening substructure. The festival’s Twitter and Instagram hashtags are participatory databases that powerfully inform live carnivalesque experience, offering instant publication of (temporary) status recalibration, as when a literary celebrity engages with a festival goer’s tweet. Sentiment is a product of the ephemeral collective identity formation that charges the PBF’s liveness with purpose.[4] The essay is divided into discussion of the “transactional” and “transformative” festival elements of the Portland Book Festival, with subsections that specify key features of the binary classification, and outliers that disrupt binary classification.

Methodology

This essay takes a multimethod approach to analyzing the carnivalesque and reactions against the carnivalesque that includes sentiment analysis of tweets from the 2017 (Wordstock) and 2018 (Portland Book) festivals; a survey of 2018 Portland Book Festival attendees; and interviews with prominent figures who created, implemented, or were affected by the branding change. A multimethod approach is important for triangulating results. In this case, a survey of 2018 Portland Book Festival attendees was conducted first and the results from the survey informed further avenues of investigation through semi-structured interviews with prominent figures who created, implemented, or were affected by the branding change. Sentiment analysis of tweets provided further connections between these three methods of exploration of the effect of the rebranding on festival participant experience.

The 14 survey questions were designed to answer the research question, “How has the rebranding of the book festival affected the participant experience?” The questions broadly fell into a few categories, including demographic information (age, ethnicity, gender, location, etc.), comparison of past Portland Book Festival experiences with the 2018 experience, list and assessment of attended events, views on the name change, and social media involvement. After the initial drafting of the survey questions by the two research investigators, the questions were approved and revised through collaboration with Literary Arts (the nonprofit organization that organizes and manages the Portland Book Festival) and the Portland State University Institutional Review Board. In order to reduce attendees’ reluctance to take the survey, every effort was made to reduce length and question complexity. Entrance into a book draw was also used to incentivize attendees to take the survey, and the survey was further legitimized to attendees through the partnership with Literary Arts.[5] In-person surveys were chosen because the response rate is often higher than with mail or web-based surveys; with in-person surveys, the researcher has the opportunity to sell the respondents on the survey[6] and, in the case of the book festival, researchers can approach attendees while they are waiting (in line, for an event to start, for food at food trucks, etc.), when they are least likely to be engaged in other activities that will prevent them from taking the survey.

Through email recruitment to students at Portland State University (PSU) in the English department (primarily graduate students, but also some undergraduate students), seven student volunteers were recruited for assistance in physically distributing the survey to festival attendees. The Portland Book Festival is more spread out in terms of venues than many other book festivals, with nine spots within seven venues. Each volunteer was randomly assigned one venue of the seven so as to cover each venue and avoid bias that might be introduced by overrepresenting certain venues. The volunteers and two lead researchers collected surveys during the festival from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. With the permission of Literary Arts, researchers and volunteers focused on lines and areas where people were waiting so as to maximize response rate and reinforce the randomness of the sample, because everyone in a line was approached in a systematic way. The sample size of 420 out of the entire population of 10,000 means that with a 95 percent confidence level, the margin of error is 4.68. The survey data was entered into a spreadsheet and closed questions were analyzed statistically while open-ended questions were analyzed with thematic coding.

Transactional Festival Elements

“Keep Portland Weird,” Wordstock, and White Privilege

Portland’s weirdness was popularized by the indie sketch comedy television show Portlandia (2011–2018), but its weird origins can be found into the 1980s. The countercultural phrase “Keep Portland Weird” is a large, painted mural on a building at SW 3rd and Ankeny. Its exhortation to “keep” Portland weird idealizes a time before Portland’s burnished reputation as a foodie—and green lifestyle—destination. The independent record store Music Millennium filed a trademark for the phrase “Keep Portland Weird” in September 2006, permitting it to own use of the phrase in Oregon in connection with “stickers, buttons and t-shirts.”[7] Music Millennium notes their first date of “Keep Portland Weird” use as October 2002. Today, the “Keep Portland Weird” mural on 3rd and Ankeny is a tourist selfie destination listed on TripAdvisor and multiple tourism blogs.

The first mediatized moment of Portland “weird”ness was in 1985 when Mayor Bud Clark, a former barkeep who campaigned with the cry of “Whoop! Whoop!”, appeared on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show.[8] In 1982, Clark became well-known in the Portland area for his poster “Expose Yourself To Art,” which was considered controversial at the time.

Figure 1

Portland weirdness. Bud Clark, Portland mayor (1985–1992).

Today, Portland’s weirdness has ebbed into upscale quirkiness that some people find precious. “There is no place in the country better known as a bastion of good living, leisure and happy inebriation than Oregon’s largest little city, the low-lying mini-metropolis of Portland,” extolled the New York Times in one of its several encomia of Portland.[9]

The commercial origin and TV media amplification of Portland’s anodyne weirdness obfuscates its truly strange mix of progressive social politics and libertarian skepticism of government regulation and taxation. This admixture is one key to understanding why the brand name “Wordstock” appealed to some Portlanders, and why municipal funding did not sufficiently support it. “Wordstock” is a joke—that a book festival would be a Portland version of a drug- and sex-fueled music festival—that also operated as an in-group identification marker. People “in the know” understood the name not only as a witticism, but as a tacit marker of elite status. The kids in 1969 who could afford to “tune in, turn on, and drop out” enjoyed privilege facilitated by money and racial whiteness that so imbued their lifestyles that they couldn’t recognize it as privilege.[10] Portland has been called the “Whitest City in America.”[11] This, too, is part of the “Wordstock” sign system.

The inaugural 2005 Wordstock, spread out over six days (April 19–24), featured programming that manifested the festival’s origin in privilege. The featured speakers were all racially white and part of the elite New York publishing establishment: John Irving, Norman Mailer, Russell Banks, Alice Sebold, Susan Orlean, and Philip Yancey.[12] Tickets to see each of these speakers cost $15–25 for general admission. Comcast was the Wordstock underwriter, with additional support from a range of national and local sponsors. Wordstock’s “Night of Literary Feasts” featured 25 unnamed authors who signed books, mixed and mingled over drinks, and then broke into 25 dinners (one author per group) at the cost of $5,000 per group. While plenty of literary arts festivals continue to use a patronage model of sponsorship, such as the Texas Book Festival, whose 2019 First Edition Literary Gala was held at the Four Seasons in Austin,[13] the combination of Wordstock’s author lineup, ticket prices, and luxury dinner fundraising indicates an event that did not aim to attract audiences beyond its own demographic.

By 2010 and 2011, Wordstock had condensed into a two-day event located in the Oregon Convention Center, with affordable ticket prices of $7 for one day and $10 for both. Children 13 and under were admitted free of charge. Wordstock began to evolve from single-author talks to panels. “Whenever we put groups of writers together on a stage, no matter who they are, people come out to see them interact,” said Wordstock Director Greg Netzer.[14] Featured speakers continued to be, in an overwhelming ratio, white. All of the headliner speakers featured in the 2011 preview printed in Portland Monthly were white; 2010 featured only one non-white headliner, Lan Samantha Chang, as represented in the Wordstock preview published online at OregonLive, the digital version of the then-daily Oregonian newspaper.[15]

The “Wordstock” name ceased to be an apt fit in the mid-2010s, when Woodstock’s availability as a cultural touchstone waned with audiences under age fifty. Comcast’s sponsorship did not endure, and the people running Wordstock—Larry Colton and Community of Writers, an organization he co-founded—scrambled to fund the festival. Literary Arts, a state-wide literary nonprofit, took over the Wordstock festival in 2015.

The second largest bank in the United States, Bank of America, became a “title sponsor” of the Portland Book Festival in 2017. Bank of America’s title sponsorship meant that its logo was prominently featured on “Wordstock” Festival logo and collateral marketing. Wordstock’s connotation with the rock festival Woodstock muddled the Bank’s philanthropic strategic goal, which is to invest in local community activities. An unambiguous, place-based festival name dovetailed with that goal. This significant sponsorship gave Literary Arts, Oregon’s largest non‑profit literary organization, the resources to complete the transformation of the Wordstock brand into the Portland Book Festival, where ticket sales comprise just 10 percent of total festival cost, and free tickets are offered to attendees 17 years old or younger. During the same time, the racial diversity of headliner speakers has also increased. Racial inclusion and community access are keynotes of Bank of America’s sponsorship of the festival: “Bank of America’s leadership in the community and continued support of Literary Arts help inspire a better, more inclusive world through the power of storytelling,” concludes the first paragraph of a 2019 blog post on the Literary Arts website celebrating the Bank’s continued sponsorship. The transactional exchange is clear: the national bank facilitates community building through sponsorship of the Festival, and the Festival gets the underwriting that pays for low ticket prices, enticing broader demographics than “Wordstock’s” original core audience.

While municipal funding is common for book festivals in the UK and Australia,[16] and Canadian festivals are eligible to apply for funding from the national Writers’ Union of Canada,[17] in the U.S., municipal funding is scarce.[18] The Portland Book Festival relies upon the Bank of America to fund the signature piece of the festival’s value proposition, affordable tickets and accessibility. In exchange, the Bank of America’s name and logo feature prominently on the Portland Book Festival logo. This is a transactional exchange that permits the transformational experience that the live, dynamic qualities of the carnivalesque unleash. Without major corporate sponsorship, the Portland Book Festival would have to increase ticket prices by approximately 400 percent.[19] The PBF does not charge admission to any of the events, including the two headliners; a book purchase guarantees a seat in the symphony hall to see a headliner, but there are no priority seats for donors or other high-status individuals.

Figure 2

Bank of America’s logo is prominent on the 2018 Portland Book Festival logo. Unlike British and Australian municipalities that host book festivals, U.S. municipalities typically contribute too little to sustain a book festival.

Diversity and Supply-side Carnivalesque

The number of nonwhite authors featured at the festival has increased since it was acquired by Literary Arts, who have also secured funding that could make every event at the festival affordable to working-class people by having no separate ticket prices for headliner events. Portland’s increasing cosmopolitanism, stoked by a population boom between 2014 and 2016 that added about 40,000 residents each year, coincides with the period when Literary Arts acquired the financially struggling Wordstock. Literary Arts Executive Director Andrew Proctor and then-new Book Festival Director Amanda Bullock, both veterans of New York City publishing and literary events, relocated the Wordstock festival from the sprawling and corporate-feeling Oregon Convention Center to Portland’s cultural arts district. Here, nestled in green park blocks with mature trees, an array of cultural institutions join together to host the Portland Book Festival: the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, multiple theatres in the Portland’5 complex, old churches, and especially the Portland Art Museum. The now one-day Portland Book Festival takes place in seven venues within short walking distance of each other in the 12-block cultural arts district. The Art Museum is headquarters for the thousands of book festival guests, who get free admission to the Museum as an added bonus: advance-purchase festival tickets are actually 25 percent cheaper than the cost of Museum admission, not to mention a full day of book festival programming. The Museum houses the two‑story book expo and approximately 70 popup readings staged directly in front of artworks individually chosen by two curators, one from Literary Arts and the other from the Museum, to complement each book. (More on the pop-up readings and celebrity, below.)

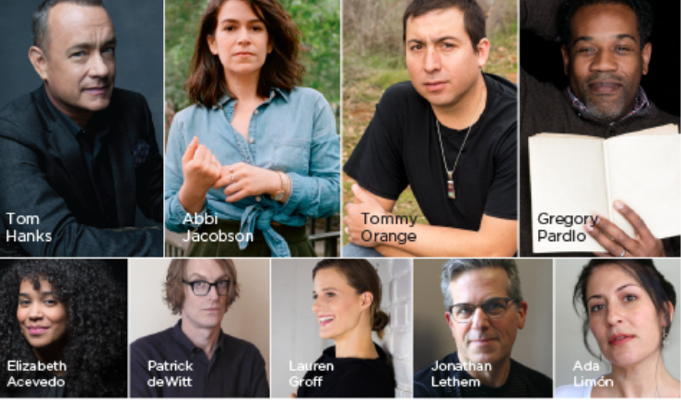

Literary Arts’ commitment to diversity manifests in both supply-side and demand-side tactics: increasing the number of non-white invited speakers, including headliners (supply); and putting $5 vouchers into the hands of every paying ticketholder so that guests can literally capitalize on discovery (demand). The optics of Literary Arts’ composite of PBF headliner headshots from 2017–2019 tells an important story about the racial diversification of literary celebrity:

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

“Until the end of the twentieth century,” observes Millicent Weber in Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture, “there was a gradual shift from supply-side to demand-side support for the arts, where supply-side funding directly supports the creation, production and distribution of cultural products, and demand-side support aims to boost consumption.”[20] Bullock’s push to boost consumption paid dividends that lifted the prospects of the entire festival infrastructure. Local, independent booksellers who sponsor PBF—Powell’s, Broadway Books, and Green Bean [children’s] Books—provide the necessary artifacts, books, that stoke the festival’s main engine: the excitement of celebrity and new author discovery. Discovery spills from the live event onto social media PBF hashtags, where photographs of “book hauls,” stacked books with spines visible, are stylized badges of pride (see also “volunteers” section, below).

Vouchers: Demand-side Carnivalesque

The vitalizing circulation of economic capital at the Portland Book Festival is driven by a unique “voucher” system: a $5 voucher is rolled into the cost of a festival ticket. With vouchers for all paid ticket holders, festival goers recoup up to one third of their entry fee to spend with a vendor at the festival, whether a bookseller at any of the seven event locations, or on the expo floor where small and midsize presses exhibit their products. Festival admission is inexpensive at $15 preorder, $20 at the door. Book vouchers power a high volume of book sales at the one-day PBF. Vouchers are not a discount. Booksellers and publishers get paid their full price, and Literary Arts absorbs the cost. “We essentially treat the festival passes as $10,” Bullock notes. “Since we’ve included the vouchers from the beginning [2015], there was no adjustment [in budgeting] needed to accommodate them.”[21] In 2018, 78 percent of PBF ticket holders bought a book. Twenty-nine percent bought three or more books. Of the 6,425 vouchers issued, well over half (54.7 percent) were used—that’s 3,515 purchases made using vouchers. 2018 voucher use jumped 7.4 percent over the previous year. The Portland Book Festival was the first festival known to implement the voucher system, although it has been adopted by other festivals since.[22]

Booksellers sponsor the PBF so long as it helps them meet their sales and marketing goals. Because vouchers can only be spent in person and on the day of the festival, “free money” supercharges the festival wander-and-browse experience because people don’t want to lose the cash value. Vouchers make it seem less risky to buy a new thing. “We collected somewhere between three to four dozen vouchers,” observed Craig Bunn, Associate Sales Manager for Pomegranate Communications, which rented a large end-cap booth on the 2018 expo floor. Pomegranate sold out of boxed notes, Edward Gorey specialty items, jigsaw puzzles, and knowledge cards. “People often spend more money when it feels like they’re getting a discount,” he notes.[23]

New York publishers have tended to see literary festivals as marketing cost centres rather than prime opportunities to sell books. Vouchers disrupt that supposition. “With the preorder opportunity [in 2018] for Abbi Jacobson and Tom Hanks,” observed Kim Sutton, Chief Customer Officer at Powell’s Books, Portland’s internationally renown independent bookstore, “PBF sales are about double a robust author event that we host at an offsite location. Vouchers are very helpful in driving sales at PBF, to incent a purchase that may not have happened, or to allow festival goers to treat themselves to an additional item.”[24]

The neoliberal funding priorities of the U.S., where civic arts projects are frequently funded or co‑funded by businesses, are a transactional value proposition.[25] “Bank of America understands that there is a transformative power in making connections between people in our community,” said Literary Arts Executive Director Andrew Proctor in a blog post announcing the bank’s continued sponsorship (emphasis ours). “We thank them for making such an important investment in our work and helping us produce a civic event that reminds all Oregonians of what we have in common: stories.”[26] Here, Proctor makes the transactional a kind of precondition to the transformative, where Bank of America’s brand messaging is woven into the argot of a civic event.

Proctor expressly connects Bank of America’s “civic” investment to a “transformative” flattening of social status at the book festival (“what we have in common: stories”), where the richest people aren’t automatically entitled to the best access. That is, the transactional nature of corporate sponsorship, where the bank donates money for people to have an enjoyable, “transformative” civic experience, repays the bank with unique local marketing, creating a local habitus for an otherwise gigantic and faceless national brand. Business involvement in activities like Portland Book Festival leads to transformative possibilities for local booksellers who sponsor the event in exchange for erecting popup stores at the seven event sites. This involves exposure to new audiences who may not regularly visit bookstores.

The greatest sign of the carnivalesque transformation of the Portland Book Festival is that 56.9 percent of attendees in 2018 attended the Festival for their first time, in contrast to 46 percent in 2017. This marks the first time in the history of the Festival that the largest portion of festival attendees were aged 35–54 years (39.9 percent), not 55 and older. The branding name change to the self-evident and transparent “Portland Book Festival” succeeded in helping the event to find new audiences. Low ticket price, communal feeling, and diverse programming increased the likelihood of attracting demographics beyond the “Wordstock” elite, observations borne out in our 2018 survey data. Younger festival goers generally prefer the Portland Book Festival name because it “[f]eels more inclusive and yet diverse, very welcoming to all,” in the words of one 25–34-year-old female survey respondent.

When respondents to the survey were asked what they thought of the festival name change, their answers revealed a divide between long-time Portland Book Festival attendees and new attendees, where more long-time attendees preferred the old Wordstock name. This illustrates resistance to change more than a particular intrinsic value to the Wordstock name. However, it was the inclusiveness and diversity that many respondents acknowledged:

“Wordstock was a clever name but the Portland Book Festival feels to connect to a larger community of book lovers.”

45–54-yr-old male respondent

“More accessible and will attract more people.”

25–34-yr-old male respondent

“Love it! Feels more inclusive and get diverse very welcoming to all.”

25–34-yr-old female respondent

“Sounds more professional.”

18–24-yr-old female respondent

Volunteers and the Festival’s Liminal Spaces

Volunteers occupy a liminal space between festival goer and festival organizer. They disrupt the binary pairings endemic to the carnivalesque. The Festival’s deliberate inversion of people’s ordinary status outside the festival feeds the festival’s carnivalesque effervescence. The benefits of liveness, the flat hierarchies in the green room, and the compressed timeline create conditions for a transformative rather than transactional experience for featured writers. Volunteer labour—including the donated labour of the writers themselves—is key to this transformative, affective experience. Portland Book Festival relies on the labour of approximately 300 volunteers, who do everything from monitoring lines and answering guest questions to engaging directly with visiting writers. Volunteer labour is the “secret sauce” of the PBF, because all writers get celebrity treatment. They are met at the airport and driven to their hotel by volunteers; they hang out in a green room reserved only for writers whose location is unmarked so fans can’t easily find it. In classic carnivalesque inversion, a celebrity like Oscar-winner Tom Hanks (a 2018 headliner) gets to be an ordinary writer talking about books, with a kind of tribal belonging that Hanks signaled by dressing down in a sweater, glasses, and jeans for his mainstage appearance (more on Hanks and celebrity, below). No writers, not even headliners, are paid to present at the Portland Book Festival. This equalizing gesture clears the way for writers to concentrate on other things than payment as markers of status. Awards and mentions on best-of lists are probably the most pertinent status indicators. Sentiment circulates like a kind of currency, too, and writers can slip into the role of fan or friend in the privacy of the green room. This green room intimacy is reinforced by volunteers who see to writers’ comfort. The writer’s job for most of their PBF experience is to socialize and have fun.

Being a volunteer is its own kind of “insider” status. Volunteers are in positions of authority to make decisions that affect the event’s smooth operation, and sometimes are offered quasi-“backstage pass” access to festival celebrities. Literary Arts surveyed their volunteers to learn what motivates their participation. Free admission to the Festival in exchange for a four-hour shift ranks fifth on the list of motivations (34 percent). The top reasons why volunteers donate time? “I love books” (85 percent) and “To support the arts” (79 percent).[27] This suggests that volunteers might be swept up in the positive emotions of the day, so that they don’t regard their four hours of donated labour as a chore. This tweet from PBF volunteer Brooke Parrott demonstrates some of the carnivalesque dynamics at play in volunteering:

Figure 6

A stylized “book haul” that tags the authors is a bid for instant status augmentation if an author likes or reposts the tweet.

Parrott’s tweet is book festival carnivalesque-in-action, where the “spoils” of personal access transform one’s usual status into something temporarily burnished. Parrott’s use of the word “spoils” conjures a Homeric setting where a warrior takes reward for superior labour on the battlefield. In this case, the battlefield is the crowded festival, where volunteer status brings Parrott into closer proximity with the highest status guests, writers. Her tweet is a carnivalesque bid for celebrity social capital, where the attractor is a stylized image replete with an arcing orchid and stacked, festival-purchased books offset from their axis to create a more dramatic column. This purchase transaction enables Parrott to transform herself from ordinary festival goer (and a relatively low-status Tweeter, with 641 followers at time of writing) to one who has had personal interaction with high status writers, two of whom are New York Times bestselling authors, and one of whom, Elizabeth Acevedo, went on to win the National Book Award three days later. Parrott’s signed “spoils” are souvenirs of “meeting so many fantastic and lovely authors.” Parrott’s rhetorical turn “Books pictured,” which she follows with a list of the authors’ Twitter handles, is a way of closing the distance between herself and the high-status writers. The books become a metonym, stand-ins for when they met face-to-face off-camera. Tagging those authors also opens the possibility that they might further validate Parrot’s “spoils” by retweeting or favouriting her post. The tactic worked: the post was liked by six accounts, three of which are high-status, Twitter‑verified (blue-checkmarked) accounts: April Baer of Oregon Public Radio (@aprilbaer), New York Times bestselling author Nova Ren Suma (@novaren), and New York Times bestselling author Acevedo (@AcevedoWrites).

Teenagers and Enduring Inversions

While the carnivalesque facilitates the reversal of roles in traditional hierarchies, such reversal is short-lived and only spans the duration of the festival event. By its very nature the carnivalesque is fleeting, but transactional elements of the PBF can enable a more permanent change. Teenagers are the class of PBF guest for whom the carnivalesque’s temporary status inversions have capacity to be enduring. Rather than the fleeting augmentation conveyed by celebrity engagement with a tweet, or the temporarily leveling effects of the green room, the types of experiences teenagers can have at PBF can be life-changing. More specifically, teenagers are given the opportunity to publicly perform their identities as writers by giving readings at the PBF. Being exposed to the writing community through free festival admission with no expectation that they will volunteer labour to offset their ticket cost means that teenagers have the freedom to explore the festival without festival-imposed constraints on their time and movement. Some respondents to the survey indicated that school‑aged kids were an important part of the festival demographic: some of the reasons they listed for attending the festival were a “field trip” (2); to go to “children’s readings [to] get our boys excited about books, writing, publishing”; “extra credit for a class”; “Family in town—fun activity”; “Free for student”; “Hear our grandson read his essay”; “kids” (4); “My daughter … she is 12 and wants to write.” Literary Arts sponsors the Writing in the Schools (WITS) program; WITS writers read at the festival from their published anthology, To Break the Stillness.

All year long, Literary Arts cultivates the supply of next-generation talent by expanding the number and socio-economic range of kids who can attend literary events. In the fall, PBF offers youth writing workshops and youth readings, and in the spring, the teen poetry slam Verslandia, held at The Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, home of the Oregon Symphony and Literary Arts’ Lecture Series, which has the most subscribers of any book lecture series in the United States. Performance at PBF and Verslandia supply writerly students with crucial experience manifesting their writerly identities. These events de-centre book publishing as the sine qua non of literary achievement, acknowledging that spoken word performance is and has long been a mode of literary production and acclaim that is more accessible to youth and marginalized people of all backgrounds. “Youth poets possess an acute ability to articulate socio-political commentary worthy of recognition when given the requisite platform and support,” note Davis and Hall in their study of spoken word performance as activism.[28]

Transformative Festival Elements

Stratification of Celebrity

We see manifestations of the carnivalesque in the stratification of celebrity that both scaffolds and disrupts the festival environment. Marwick and boyd [sic] view celebrity as a continuum of fame, rather than as a clear designation between celebrities and non-celebrities,[29] since a local author is not a celebrity in the same way that an international star like J.K. Rowling would be, even though that local author has some fame in certain circles. At the Portland Book Festival, all authors fall somewhere on this continuum, depending on the size of their fan communities and their recognizability to readers. The organizers of the Festival aim to make this celebrity continuum as wide as possible, with a concerted emphasis on local authors and on giving even small authors (“micro celebrities,” we might call them) a window of time in the spotlight at this legitimizing event.

There is a particular stratification and hierarchy that is expected at an event like a literary festival. A literary festival is a performative experience in which agents play their roles—roles such as author, moderator, volunteer, reader, and so on. It’s a space of identification, where “authors and readers identify themselves and one another” and where these agents and others “compete for legitimacy through the acquisition of cultural, social, and economic capital.”[30] In terms of the carnivalesque, is the stratification of celebrity at the Portland Book Festival carnivalesque or traditional? Does it offer a transformative or transactional experience? We argue that stratification of celebrity at the Portland Book Festival is transformative because it is both responsive to and contingent on liveness.

In his analysis of liveness in theatre performances, Reason identifies three elements of liveness as important to the live event experience: shared memory, the humanness of the performer, and the sense community with other members of the audience.[31] This section focuses primarily on Reason’s liveness element of “humanness of the performer” as it relates to the idea of celebrity. In addition, there is another aspect of liveness that is important to the literary festival experience: serendipity or unexpectedness. The contextual elements of the event (which inform the experience) are impossible to disentangle from the event itself, particularly because the context shapes the event. The transformative aspects of the Portland Book Festival can be observed within four general categories: fluidity within traditional hierarchies, subversion of traditional hierarchies, role of venue in stratification, and role of locality in stratification.

Fluidity within Traditional Hierarchies

Like other festivals of its kind, the Portland Book Festival is primarily a festival for readers. This was evident in the survey data of festival attendees, where 92 percent of respondents self-identified as readers. However, only 39 percent of those who self-identified as readers identified only as readers; the other 61 percent self-identified as “reader” along with another category: writer, teacher, student, academic, publishing professional, librarian, or other. In contrast to data from previous scholars in which over half of literary festival audience members identified as writers themselves,[32] only 34 percent of respondents self-identified as writers, and only one respondent identified as only a writer. Thirty-nine percent of respondents said that they were readers and writers. Eighteen percent identified as teachers, 14 percent as students, 10 percent as other, 9 percent as academics, 6 percent as publishing professionals, and 5 percent as librarians. This data illustrates the fluidity of identities and hierarchies within the festival. The Twitter data demonstrated the prominence of writers‑as‑readers; these authors exude fandom and excitement over getting to meet or see their own favourite authors. They might be alternatively seen as celebrities-as-fans, where despite their elevated status on the celebrity continuum of fame, in the literary festival, they play roles both as celebrities and as fans.

An individual can hold multiple identities simultaneously and perform those identities differently depending on the context. This is what we see among both the participants and the celebrities at the Portland Book Festival. But in addition to the fluidity of roles, we also see a fluidity in different “types” of celebrity, not insofar as their placement on the celebrity continuum of fame, but rather in why the individual is famous. The prime example of this is the headliner for the 2018 Portland Book Festival: actor Tom Hanks. Tom Hanks was at the Portland Book Festival as an author, but Hanks’s celebrity status is not based on his prominence as an author. Instead, festival attendees came to see Tom Hanks not as readers at an author event, but as fans at a performance of a well-known and well-loved actor celebrity. Comedian Abbi Jacobson and chef Edward Lee are other examples of individuals whose celebrity status does not prominently hinge on their identities as authors, even though it was as authors that they came to the festival. For some festival participants, Hanks was seen as not “literary” enough a celebrity to be the headliner at a literary festival. One tweeter said, “I skipped the headliner (Tom Hanks—not as ‘literary’ as I’d hoped).”

Turner asserts that the process of celebritisation itself is transformative.[33] The celebritisation process is one that has changed dramatically in the twenty-first century in that it is a “more level playing field” because there are more ways in which “ordinary individuals might obtain celebrity status.”[34] This is particularly the case in the literary community, where small but enthusiastic audiences and niche groups are enough to establish a level of micro-celebrity or local celebrity status for a writer. Within the Portland Book Festival’s live experience, in which a community of bookish participants are drawn together to celebrate books and authorship for a day, these micro‑celebrity authors are celebrities at the festival but not celebrities in everyday life outside of the festival. The experience of this kind of celebrity status is fleeting and, thus, carnivalesque.

This fluidity in hierarchies and identities is contingent on liveness. An author may be a literary celebrity during their panel or pop-up event, but a fan and a reader during the other events they attend at the festival. Small measures of legitimacy—even a presenter badge, for example—can make all the difference in the switch between readerly and writerly identities. This was the case for Portland-based debut author Tabitha Blankenbiller, who saw the “real badge” she was given at the festival as a legitimizing symbol of her “true writer” status.

Figure 7

The higher on the celebrity continuum of fame an author resides, the more liveness becomes an essential part of the experience for readers. Murray and Weber observe, “The more famous and virally circulated a certain authorial festival appearance becomes, the more literary bragging rights attach to having actually been there—having witnessed it live.”[35] Thus, we see that the stratification of celebrity in the festival is fluid because readers, writers, and others occupy multiple identities and perform different identities and roles as the context requires. We also see that celebritization itself is a transformative experience, and liveness influences the role that an individual at the festival performs as well as the degree of importance given to liveness (based, in part, on the place of the celebrity on the fame continuum).

Subversion of Traditional Hierarchies

Reason argues that humanizing the performer is an important aspect of live performance.[36] Likewise, Murray and Weber note that literary festival attendees describe the events as humanizing, “emphasizing the invaluable quality of the direct, face-to-face contact with a writer.”[37] Nowhere is this more evident than in the oft-shared pictures on Twitter of the moment that Tom Hanks paused in his literary performance on stage to hold a baby from the crowd. As arguably the person at the literary festival with the most fame and highest “celebrity capital,” this act was especially humanizing and relatable to the audience. While a recognizable actor celebrity in everyday life, Tom Hanks performs his roles as “author” and “ordinary person” at the book festival.

Figure 8

During Tom Hanks’s presentation at the 2018 Portland Book Festival, Hanks held a baby from the audience, which elicited social media excitement from audience members.

Not only is there fluidity in the celebrity hierarchies at the festival, but there are also moments when those roles are suberverted, and it is in the subversion that humanity is revealed. Celebrity studies scholars have emphasized that the relationship between celebrity and fan is asymmetrical and not mutual,[38] and it is usually a relationship in which the fan feels a kinship with the celebrity even though the fan and celebrity have never met face-to-face. What is different about literary celebrities, especially in the context of book festivals, is that they can often be accessed in more intimate spaces than other celebrities can be by fans. As Murray and Weber note, literary festivals not only “propagate the celebrity status of authors” but do so in an intimate space that gives an “interpersonal dimension to readers’ experiences of their books.”[39]

Still, proximity (even in an intimate setting) does not mean that an equal relationship develops between literary celebrity and fan. The best illustration of this is the Portland Book Festival participant who tweeted two pictures of the top headliners on stage: Tom Hanks in one and Abbi Jacobson in the other. Infusing his post with deliberate irony, the tweeter jokes that Tom Hanks and Abbi Jacobson are his new best friends, because he is in the same room as them.

Figure 9

A reader infuses his post with deliberate irony to indicate that being in the same room with literary celebrities Tom Hanks and Abbi Jacobson results in a friendship between literary celebrity and fan.

Role of Venue in Stratification

The Portland Book Festival is located in downtown Portland at seven clustered venues around an area known as the “park blocks.” Streets directly outside the park blocks area of the festival are blocked off on the day of the festival for safety reasons. For the most part the venues are familiar ones: church buildings, concert halls, and other cultural buildings. But there are two particular venues or spaces that challenge the traditional and involve serendipity, spontaneity, and liveness in unique ways: the Portland Art Museum and Lit Crawl venues.

The Portland Art Museum is the central location for the Portland Book Festival. Just outside the museum doors, tents are set up on the day of the festival for registration. A ticket to the Portland Book Festival includes free entry into the Portland Art Museum. But the unique use of the art museum space is for the popup events, and the primary value of Portland Book Festival to the Portland Art Museum is in those popup events. Stephanie Parrish, Associate Director of Programs, says that the popup literary festival events get people “into the galleries,” which is not something that necessarily happens at many book festivals.[40] In fact, Liz Olufson, Public Programs Coordinator at Literary Arts, said she spends months curating, researching, and matching appropriate art gallery pieces with particular authors and books.[41] Art museums are spaces typically associated with highbrow, elite patrons and frameworks that have, traditionally, not been perceived as accessible to a wide group. But the free ticket to the art museum and the minimal commitment needed for a popup event bring what the museum hopes is a new audience. The popup events are short, around 10 or 15 minutes. Stephanie Parrish said of these short events, “it’s not a big investment of time [for attendees], but they pack a punch.” And while Parrish sees the relationship with the museum as being one of the partnerships that helps to de-weirdify and professionalize the festival, the quirkiness comes in the unrestricted nature of the events: “It’s about supporting artists. It’s about having fun. It’s about watching the creative process and different versions of it unfold.”[42] In popup events, which are allotted to small-name and big-name authors alike, authors can choose to adopt any format they like. While many authors stick to the traditional format of reading a portion of their written piece, others spend the time playing music, engaging in Q&A and informal chat with fans, and myriad other activities.

Figure 10

These popup events are some of the aspects of the festival that attendees praise most highly. As Murray and Weber note, smaller events have a special intimacy that allows for “affectively charged experience which connects those members of the audience.”[43] This affectively charged experience is a transformative one.

Figure 11

The curated pairings of particular authors, books, and art in the pop-ups at the Portland Art Museum create intimate and emotional experiences for readers.

Perhaps one of the most important aspects of the popup events, however, is their conduciveness to serendipitous discovery. As Weber notes, serendipitous discovery is vital to literary festivals: “The importance of the serendipitous discovery, and of being able to access new writers with a certain degree of credibility and talent, is considered valuable by numerous audience members.”[44] Because of the minimal time commitment of a popup event, festival participants can fit popup events in between other events they want to see, and can thus encounter new authors in a low-risk, low-investment way. This allows readers to find “new celebrities” through popups, elevating authors in celebrity status on the continuum through serendipitous discovery.

Another set of venues that is ripe for serendipitous discovery at the festival is Lit Crawl. Lit Crawl is a collaborative project between Literary Arts and Litquake. Lit Crawl in Portland is not unique to Portland; there are other Lit Crawl events held in San Francisco, Manhattan, Brooklyn, Austin, Los Angeles, Iowa City, Seattle, London, Helsinki, Chicago, Denver, and Cheltenham.[45] Lit Crawl PDX is a series of smaller, informal events in Portland the night prior to the Portland Book Festival. Events move around to various local venues, from breweries to music stores to bookstores. The informal and low-risk nature of Lit Crawl makes it conducive to discovering new authors, as is illustrated in the following tweet.

Figure 12

Serendipitous discovery of new authors and books at the Portland Book Festival is facilitated by initiatives such as Lit Crawl PDX, pop-up readings, and matching debut authors with established authors on panels.

Role of Locality in Stratification

Literary Arts maintains a program with at least 40 percent local authors for the Portland Book Festival.[46] This is an important source of pride for the organization; even as the festival grows and expands, local authors remain a part of the festival programming and experience. In many ways treatment of authors (local or national, small-name or big-name) is more democratized at the Portland Book Festival than at other festivals. For one thing, none of the authors at the Portland Book Festival is paid to be there. This means that Tom Hanks is paid (or, rather, not paid) the same amount as a debut and local Portland author. All receive free access to the rest of the festival events, author badges, escorts from one venue to another, access to the author green room, and socialization at a special afterparty just for authors.

Ferris calls local celebrities a type of “subcultural celebrity” who are only treated as famous by their fans and not by others. We might say the same of local authors. There are many benefits to a celebrity being local, including that they are “easier for audiences … to access … and to connect with interactionally, which may alter some of the relational asymmetries associated with global celebrity.”[47] In other words, where fan face-to-face interactions with national or global celebrities remain minimal, it is more possible for local celebrities to not only interact face-to-face with fans in the area but also to develop more symmetrical and reciprocal celebrity/fan relationships.

The prominence of local authors is echoed in the demographics of festival attendees. According to the survey of 2018 Portland Book Festival attendees, 87 percent of attendees in 2018 live in Oregon compared to 84 percent of attendees in 2017, so local attendance at the Portland Book Festival has increased from 2017. The average travel distance to the festival was 170 miles. Seventy-four percent (a portion of that 84 percent from Oregon) are specifically from Portland or the surrounding areas. Thus, the festival currently serves an audience that is overwhelmingly local, not only to the state (Oregon) but to the specific city in which it is hosted (Portland).

Figure 13

Portland Book Festival primarily serves a local audience of readers. While Portland Book Festival attendees come from regional, national, and international contexts, 75% live in Portland or surrounding areas, with 87% of attendees in 2018 living in Oregon.

With Literary Arts and with other festivals, the difficulty is in maintaining a balance between local and national. Murray and Weber observe that overemphasizing the national or international community can lead to a critique of elitism and subsequent funding cuts, but overemphasizing local relevance “invites criticism of the festival’s provincialism, a failure to attract ‘big names’ suggesting it is not/no longer an A-list festival.”[48] Finding the balance between the local and national—in programming, attendance, and other aspects of the festival experience—is the challenge.

Centre and Periphery

The centre and periphery are both transactional and transformative, carnivalesque and non-carnivalesque. Transactional and transformative are not demarcated necessarily along centre vs. periphery boundaries, but the “centre vs. periphery” perspective is an important one because without delineating the accepted and unaccepted, the traditional and the subversive, it’s impossible to address the power structures that are then subverted or reversed in the carnivalesque. We might also think of the carnivalesque not only as a subversion of traditional power structures, but a subversion of centrifugal and centripetal forces, changing which people are in the centre of the events of the book festival and which people are in the periphery. Murray and Weber argue that centre and periphery define the audience experience itself:

The audience is simultaneously situated “outside” and “inside” the text: it is witness to the performance, in a sense observing, and therefore outside it; but it is also a function of the performance, conceptually convened by it and through its real-time feedback influencing it, and therefore inside it. These tensions, between singular and collective entity, physical and conceptual experience, define and give texture to the experience of a performance and the conception of a live work.[49]

At the Portland Book Festival, live events are at the centre and social media is at the periphery, particularly because of the limited social media interaction that happens during the festival (including live tweeting). On social media, only 21 percent of attendees follow Literary Arts, and only 16.4 percent post about the festival. Literary Arts has 2,597 followers on Instagram, 8,500 likes on Facebook, and 8,616 followers on Twitter. Particularly on Facebook and Twitter, these are fairly substantial followings, but despite this, attendees at the Portland Book Festival do not engage with Literary Arts social media during the festival. As Weber notes, the interplay between “online and onsite engagement with literary culture” demonstrates that the live and the mediated go hand‑in‑hand. Social media and other forms of digital engagement offer additional outlets to the literary festival audience for experiencing literature and connecting with others—writers and readers alike.[50]

Physical attendance and liveness were among the themes and goals of Literary Arts in planning the festival because they wanted the draw to be for readers to attend one “unmissable” day.[51] This was also part of the reason that the Portland Book Festival is a one-day event rather than multi-day event. As has been discussed earlier, liveness provides a specific experience that is essential to the festival and difficult to replicate in digital spheres. Therefore, the Twitter space sometimes reflects people’s disappointment that they were unable to be there in person, as in the tweet below.

Figure 14

The liveness of the Portland Book Festival creates an exclusiveness and uniqueness that leaves those unable to attend pining for the live experience.

As Murray and Weber remark, “Although literary communities and interpersonal relationships frequently do develop in online spaces, a sense of physical isolation and medium-induced disconnect lingers.”[52] The exclusive, unique, and located qualities of a literary festival are defined by their liveness.[53] Thus, attendees who can participate in the physical and live events experience the transformative carnivalesque, whereas those following the limited conversations and updates about the festival on social media engage in a transactional experience.

Despite its unique qualities and carnivalesque aspects, the Portland Book Festival operates within the social, economic, and political structures of the city of Portland itself; it’s impossible to disentangle the festival from the city in this way. Two specific examples illustrate this: diversity and homelessness. One of the main objectives of Literary Arts is for the festival to be diverse: “We aim to present a diverse lineup in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, discipline/genre, geography, age, and more.”[54] This has particularly been reflected in the programming; respondents to the 2018 survey praised the diversity of the authors at the festival. However, this is not necessarily reflected in the demographic of participants. According to 2017 census data, 77.4 percent of Portlanders are white. This number is mirrored in the festival survey respondents, where 79.6 percent identified as white.

Figure 15

The Portland Book Festival operates within the social, economic, and political structures of the city of Portland itself, evidenced by the racial identity of attendees mirroring the demographics of the city in terms of whiteness.

Literary Arts has been implementing initiatives to keep the festival price down, to let children in for free, and to encourage underrepresented communities to attend, but because the festival is still situated within the very white (and politically progressive) Portland area, it is difficult to disentangle the demographics of place from the demographics of the festival. In this way, the racial diversity in programming still reinforces structures that are already there, and the hegemony absorbs the carnivalesque.

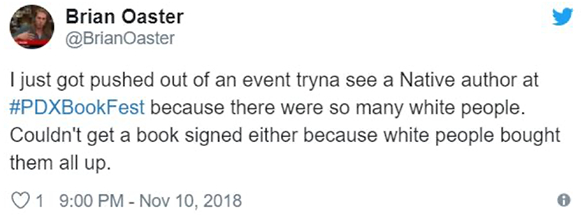

In an example from Twitter of how the racial power structures and demographics of the festival continue to shape participant experience, one attendee tweeted the following:

Figure 16

This tweet reveals that racial power structures and demographics continue to shape participant experience at the Portland Book Festival.

Here the excellence of the diverse programming is juxtaposed with a demographic that is racially homogenous, resulting in some tense situations. Brian Oaster’s tweet is carnivalesque, suggesting that the open access the Festival is expressly trying to promote may not work if more privileged (white) guests get to the event first. In a different tweet, Oaster tagged “@Powells and #PDXBookFest organizers,” saying “if you want to include Native ppl, please consider having a priority line for Natives, and host in family-friendly spaces.”[55] Oaster believes that special conditions should be created to operationalize equal access because increasing the number of BIPOC (Black and Indigenous people of colour) presenters isn’t sufficient. That is, Oaster punctures the notion that the carnivalesque atmosphere of the festival overturns, even for one day, status inequalities that exist in ordinary life.

Homelessness is also very much a part of the city, at both the centre and the periphery. The Portland Book Festival is geographically at the centre of the westside: the park blocks. However, there is not one central venue where all of the festival events take place; instead, events are held in a collection of geographically close venues. Participants at the festival therefore move from venue to venue, from the Portland Art Museum and then across the blocks to the Oregon Historical Society building or even further afield to venues like the Old Church. One volunteer researcher noted a particular experience in which those not part of the festival clashed with participants of the festival because the geography of the festival overlapped with the centre of the city:

The only really interesting thing that happened was while we were waiting for the Women and Power panel in UCC [United Church of Christ], someone who was not attending the festival was yelling at the line from across the street. As the event is held across several buildings in downtown PDX, I’m sure that there were some people who happened upon the event by accident.

Thus, participants at the festival are at both the centre and the periphery in that they are at the centre of the literary festival, where non-participants on the periphery are looking in, and they are also on the periphery of the city’s downtown in that the carnivalesque book festival experience exists outside of the “everyday.” Therefore, the festival participants and others within the same physical area sometimes experience conflict, both in that the festival goers can become frustrated by the peripheral (to them) others and the non-participants can become frustrated by the peripheral (to them) festival goers. While the example above highlights a moment when those peripheral to the festival became frustrated with festival participants, there are just as many (if not more) instances of festival participants coming into conflict with other people in the Portland park blocks area. One common example of this is the intersection of festival participants with homeless people in this area.

According to a 2017 study, 4,177 people are homeless in Portland, which was up 9 percent from 2015.[56] Portland has a homelessness problem; this feature of the city influences many events, not exclusively the Book Festival. For example, the conference for the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, held at the Oregon Convention Center in Portland in February of 2019, enclosed the literary community within the building—in stark contrast to the homeless communities in immediate surrounding areas.

One student festival participant made this observation to the supervising researchers about the juxtaposition of homelessness and highbrow literary celebration: “I overheard some people complaining about the amount of homeless people at the festival (in outdoor areas). I don’t know why they were so surprised. That part of town has long had a large homeless population, and they’re not just going to disappear because of a highbrow literary festival.” Not much could be less carnivalesque than the slamming together of these two worlds (one elite, one homeless) with no role reversal or play.

Figure 17

Within the geographical boundaries of the Portland Book Festival, the attendees of the festival intersect with the homeless populations in the park blocks.

Through this centre-periphery lens, we see that live events, dominant/majority groups, and the geographical park blocks are at the centre of the festival experience. Meanwhile, social media, diverse/minority groups, and the space geographically outside of the Portland Book Festival are on the periphery. This polarized structure illustrates some of the power structures that underlie the festival, particularly racial and socio-economic. In certain aspects of the festival experience these power structures are altered, as in the emphasis on programming of diverse authors. Other aspects, however, maintain these structures, which are not only a part of the Portland Book Festival but, importantly, of the city of Portland itself.

Conclusion

This essay has traced aspects of the carnivalesque in assessing the impact of rebranding the annual Portland-based literary festival from “Wordstock” to “Portland Book Festival.” Applying the carnivalesque as a lens onto status hierarchies that the festival’s carnivalesque atmosphere temporarily flattens or inverts,[57] we have identified how the stabilizing, transactional elements of the Portland Book Festival make possible the festival’s capacity to recalibrate status or identity, either fleetingly (as in true carnivalesque) or durationally, as with teenagers and non-white communities who were underserved by the Wordstock experience.

Infrastructural steps taken by Literary Arts to stoke both demand (vouchers, volunteers) and supply (a diverse roster of featured talent, cultivation of young talent) balance the transactional with the transformative. Bank of America sponsorship, cultural organization alliances, and Portland place branding offer transactional stability at the festival, where parties give and get in kind. The recalibration of celebrity and centre/periphery dichotomies offer transformational experiences at the festival. These are contingent on the human connection, serendipity, discovery and role reversal that a live festival compresses into an intense, prescribed time period. Liveness and the carnivalesque can spark new passions and popularity that eventually become so influential that they transmute into status quo, as was the case when the positive sentiment around Elizabeth Acevedo’s 2018 PBF performance seemed to be validated when she won the National Book Award three days later.

The percentage of first-time PBF attendees is growing (46 percent in 2017 to 57 percent in 2018). This trend and the 2018 survey responses suggest that new festival goers in particular understand that the transactional elements and the name change to Portland Book Festival enable a more democratic and accessible festival experience.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Kathi Inman Berens is Assistant Professor of Book Publishing and Digital Humanities at Portland State University. She earned her PhD at the University of California at Berkeley, and was a US Fulbright Scholar of Digital Culture in Norway. She researches digital-born literature, twenty-first-century book culture, media theory, and digital pedagogy. She is published in the Debates in Digital Humanities series, Literary and Linguistic Computing, Publisher's Weekly, Hyperrhiz Journal of New Media, and Electronic Book Review. She is co-editor of the forthcoming Electronic Literature Collection Volume 4.

Rachel Noorda is the Director of Book Publishing and Assistant Professor in English at Portland State University. She has a PhD in Publishing Studies from the University of Stirling. Her research interests include twenty-first-century book culture, diaspora communities, Scottish publishing, small business marketing, international marketing, and entrepreneurship. She has been published in Book History, National Identities, Studies in Book Culture, Publishing Research Quarterly, Quaerendo, and the forthcoming Handbook on Marketing and Entrepreneurship.

Notes

-

[1]

Beth Driscoll and Claire Squires, “Book Commerce Book Carnival: An Introduction to the Special Issue”, Mémoires Du Livre/Studies in Book Culture 11, no. 2 (2020): 3.

-

[2]

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Helene Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984).

-

[3]

Ronald Knowles, “Carnival and Death in Romeo and Juliet,” in Shakespeare and Carnival: After Bakhtin (Macmillan, 1998), 45.

-

[4]

Beth Driscoll, “Sentiment Analysis and the Literary Festival Audience,” Continuum 29, no. 6 (2015): 861–73; Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (Routledge, 2008).

-

[5]

Don Dillan, Jolene Smyth, and Leah Christian, Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method (John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

-

[6]

Kate Kelley, Belinda Clark, Vivienne Brown, and John Sitzia, “Good Practice in the Conduct of Reporting of Survey Research,” International Journal for Quality in Health Care 15, no. 3 (2003): 261–66.

-

[7]

Ownership of “Keep Portland Weird” is limited to Oregon because the phrase originated in Austin, Texas with the Austin Independent Business Alliance. Red Wassernitch, a novelist, lists his first credential on his Amazon biography as being the “inventor of the phrase ‘Keep Austin Weird.’” https://www.amazon.com/Red-Wassenich/e/B001JS89N2.

-

[8]

See UPI archives: https://www.upi.com/Archives/1985/02/15/Mayor-Whoop-Whoop-says-No-No/4652477291600/ Accessed online 13 September 2019.

-

[9]

Freda Moon, “36 Hours in Portland, Ore.,” New York Times, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/13/travel/what-to-do-in-36-hours-in-portland.html. Accessed online 13 September 2019.

-

[10]

This Reddit thread argues that LSD guru Timothy Leary’s phrase is actually: “turn on (to LSD), tune in (to collective consciousness), drop out (of mainstream society).” https://www.reddit.com/r/Retconned/comments/7xi7hc/tune_in_turn_on_drop_out_turn_on_tune_in_drop_out/.

-

[11]

Real estate redlining was a practice in Portland as late as the 1970s. Sundown laws and other Jim Crow double standards are hidden beneath the veneer of Portland’s seemingly progressive politics. See three articles in Oregon Historical Quarterly’s Fall 2018 Public History Roundtable “Housing Segregation and Resistance in Portland, Oregon,” particularly Greta Smith, “‘Congenial Neighbors’: Restrictive Covenants and Residential Segregation in Portland, Oregon,” 358–64. See also Alana Semuels, “The Racist History of Portland, the Whitest City in America” published in The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/07/racist-history-portland/492035/.

-

[12]

See this BusinessWire post from 2005: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20050329005228/en/World-Class-Wordstock-Book-Festival-Takes-Portland-April Accessed online 13 September 2019.

-

[13]

“First Edition Literary Gala,” 2018 Texas Book Festival. (Austin, TX) https://www.texasbookfestival.org/gala/ (permalink leads to annual event; no particular page for 2018 gala.

-

[14]

Quoted in “Wordstock 2011 Preview” by the Culturegang of Portland Monthly (October 4, 2011). https://www.pdxmonthly.com/articles/2011/10/4/wordstock-2011-preview-october-2011 Accessed online 13 September 2019.

-

[15]

Jeff Baker, “Wordstock preview: An A to Z guide to this weekend’s literary festival” (October 8, 2010). https://www.oregonlive.com/books/2010/10/wordstock_preview_an_a_to_z_gu.html.

-

[16]

Millicent Weber, Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018); Simone Murray and Millicent Weber, “‘Live and Local’? The Significance of Digital Media for Writers’ Festivals,” Convergence 23, no. 1 (2017): 61–68.

-

[17]

See the Writer’s Union of Canada website: https://www.writersunion.ca/canadian-festivals-and-reading-series.

-

[18]

“The principal funders of literary festivals internationally are typically the cultural policy divisions of national, state/provincial and local governments,” note Murray and Weber, “Live and Local?”, 64.

-

[19]

Interview with Amanda Bullock, Portland Book Festival Director, July 11, 2019. Bullock speculates that without corporate sponsorship, prices might need to be even higher than a 400 percent increase because the festival would sell fewer tickets, so cost per unit would go up. See also the Literary Arts blog post “Bank of America returns as the Title Sponsor for the Portland Book Festival in 2019” (5 June 2019).

-

[20]

Weber, Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture, 157.

-

[21]

Bullock quoted in Kathi Inman Berens, “Vouching for Vouchers,” Publishers Weekly, August 5, 2019. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/columns-and-blogs/soapbox/article/80835-vouching-for-lit-fest-vouchers.html.

-

[22]

For example, Minnesota-based literary festival Wordplay offered $5 vouchers as part of the ticket price for its 2019 event.

-

[23]

Bunn quoted in Berens, “Vouching for Vouchers.”

-

[24]

Sutton quoted in Berens, “Vouching for Vouchers.”

-

[25]

Name changes of municipal stadia are one example of the shift from municipal to corporate funding of civic endeavours. Southwest Portland’s stadium originally bore place names Multnomah Field (1893–1926) and Multnomah Stadium (1926–1965). The allusion to Multnomah County was dropped in 1966, when it was renamed Civic Stadium (1966–2000). Since 2001, the stadium has had three names in 18 years, all reflecting then-current corporate donors: PGE Park (2001–2010), Jeld-Wen Field (2011–2014), and now Providence Park (2015–present).

-

[26]

“Bank of America returns as the Title Sponsor for the Portland Book Festival in 2019,” Literary Arts blog, 5 June 2019, accessed September 13, 2019, https://literary-arts.org/2019/06/bank-of-america-returns-as-the-title-sponsor-for-the-portland-book-festival-in-2019/.

-

[27]

Communication with Amanda Bullock, September 12, 2019.

-

[28]

Camea Davis and Lauren Hall, “Spoken Word Performance As Activism: Middle School Poets Challenge American Racism”; Sarah Crown, “Generation next: the rise—and rise—of the new poets,” The Guardian February 16, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/feb/16/rise-new-poets; Chris Jackson, “Diversity in Book Publishing Doesn’t Exist—But Here’s How It Can” (blog post), 10 October 2017.

-

[29]

Alice Marwick and danah boyd [sic], “To See and Be Seen: Celebrity Practice on Twitter,” Convergence 17, no. 2 (2011): 139–58.

-

[30]

Weber, Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture, 32.

-

[31]

Matthew Reason, “Theatre Audiences and Perceptions of ‘Liveness’ in Performance,” Particip@tions [sic]: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies 1, no. 2 (2004).

-

[32]

Wenche Ommundsen, “Literary Festivals and Cultural Consumption,” Australian Literary Studies 24, no. 1 (2009): 19–34; Beth Driscoll, The New Literary Middlebrow: Tastemakers and Reading in the Twenty-First Century (Palgrave Macmillian, 2014).

-

[33]

Graeme Turner, “Approaching Celebrity Studies,” Celebrity Studies 1, no. 1 (2010): 11–20.

-

[34]

Hannah Hamad, “Celebrity in the Contemporary Era,” in Routledge Handbook of Celebrity Studies, ed. Anthony Elliot (Routledge, 2018), 51.

-

[35]

Murray and Weber, “Live and Local?”, 74.

-

[36]

Reason, “Theater Audiences,” 2004.

-

[37]

Murray and Weber, “Live and Local?”, 66.

-

[38]

Kerry Ferris, “The Next Big Thing: Local Celebrity,” Society 47, no. 5 (2010): 392–95.

-

[39]

Murray and Weber, “Live and Local?”, 67.

-

[40]

Interview with Stephanie Parrish, July 9, 2019.

-

[41]

Interview with Liz Olufson, July 11, 2019.

-

[42]

Interview with Stephanie Parrish, July 9, 2019.

-

[43]

Murray and Weber, “Live and Local?”, 70.

-

[44]

Weber, Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture, 133.

-

[45]

Literary Arts website, “Lit Crawl,” accessed September 13, 2019, https://literary-arts.org/what-we-do/pdxbookfest/lit-crawl/.

-

[46]

Interview with Amanda Bullock, July 11, 2019.

-

[47]

Ferris, “The Next Big Thing,” 393.

-

[48]

Murray and Weber, “Live and Local?”, 64.

-

[49]

Ibid., 69.

-

[50]

Weber, Literary Festivals and Contemporary Book Culture, 141.

-

[51]

Interview with Amanda Bullock, July 11, 2019.

-

[52]

Murray and Weber, “Live and Local?”, 70.

-

[53]

Ibid., 74.

-

[54]

Literary Arts, “Literary Arts Strategic Framework Program Assessment 2019–2022,” accessed September 13, 2019, https://literary-arts.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2019-2022_LitArtsStrategicPlan_Assessment_FINAL.pdf, 22.

-

[55]

Brian Oaster, Twitter post, November 10, 2018, 8 :01 p.m.: https://twitter.com/brianoaster/status/1061469060372656128.

-

[56]

Molly Harbarger, “Portland’s homeless population jumps nearly 10 percent, new count shows,” The Oregonian, June 19, 2017.

-

[57]

Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World.

Bibliography

- Auslander, Philip. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. Routledge, 2008.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World, translated by Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

- Berens, Kathi Inman. “Vouching for Vouchers.” Publishers Weekly, August 5, 2019. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/columns-and-blogs/soapbox/article/80835-vouching-for-lit-fest-vouchers.html.

- Bullock, Amanda (Director of Public Programs at Literary Arts), interview by Rachel Noorda and Kathi Inman Berens. Portland, July 11, 2019.

- Culturegang (collective at Portland Monthly magazine), « Wordstock 2011 Preview », Portland Monthly, October 4, 2011. https://www.pdxmonthly.com/articles/2011/10/4/wordstock-2011-preview-october-2011.

- Davis, Camea & Lauren M. Hall. « Spoken Word Performance As Activism: Middle School Poets Challenge American Racism. » Middle School Journal: Student Activism 51 no. 2 (2020) 6–15. DOI: 10.1080/00940771.2019.1709256.

- Dillan, Don, Jolene Smyth, and Leah Christian. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

- Driscoll, Beth. “Sentiment Analysis and the Literary Festival Audience.” Continuum 29, no. 6 (2015): 861–73

- Driscoll, Beth. The New Literary Middlebrow: Tastemakers and Reading in the Twenty-First Century. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Driscoll, Beth and Claire Squires, “Book Commerce Book Carnival: An Introduction to the Special Issue”, Mémoires Du Livre/Studies in Book Culture 11, no. 2 (2020): 1–16.

- Ferris, Kerry. “The Next Big Thing: Local Celebrity.” Society 47, no. 5 (2010): 392–95.

- Hamad, Hannah. “Celebrity in the Contemporary Era.” In Routledge Handbook of Celebrity Studies, edited by Anthony Elliot, 44–57. Routledge, 2018.

- Harbarger, Molly. “Portland’s homeless population jumps nearly 10 percent, new count shows,” The Oregonian, June 19, 2017.

- Knowles, Ronald. “Carnival and Death in Romeo and Juliet.” In Shakespeare and Carnival: After Bakhtin, 36–59. Macmillan, 1998.