Abstracts

Abstract

A study of the translation of advertising material cannot be restricted to the analysis of language transfer, as the effectiveness of advertisements is contingent upon the successful linkage of (audio)visual elements, media of dissemination and written text. This paper analyses the cross-cultural dissemination of advertisements for the video-game industry, examining commercial arguments from a linguistic and cultural perspective.

It is posited here that, in spite of their apparent disparity, the disciplines of translation theory and marketing interface to a large extent in the context of cross-cultural advertising. In the global marketplace, multinationals are faced with the choice to either internationalize or localize the promotion of their products, an issue that mirrors the long-standing debate on naturalising (or domesticating) vs. foreignizing translation strategies. The conclusion reached is that the cross-cultural dissemination of advertising material is best served by adopting an instrumental approach to translation, as described by Nord (1989).

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- internationalization,

- localization,

- cross-cultural communication,

- videogames

Résumé

Une étude de la traduction des textes publicitaires ne peut se limiter à l’analyse du transfert linguistique dans la mesure où l’impact publicitaire dépend de la réalisation d’une fusion entre les éléments (audio-)visuels, le mode de diffusion et le texte écrit. Cet article porte sur l’analyse de la diffusion transculturelle de textes publicitaires issus du secteur des jeux vidéo, et en particulier sur l’examen des arguments commerciaux selon une perspective culturelle et linguistique.

Il est suggéré qu’en dépit de leur apparente disparité, les disciplines de la théorie de la traduction et du marketing se recoupent largement dans le contexte de la publicité transculturelle. Sur le marché mondial, les multinationales peuvent faire le choix de l’internationalisation ou de la localisation pour la promotion de leurs produits, reflétant ainsi le débat de longue date sur la domestication vs la foreignisation. La conclusion proposée est que la meilleure réalisation de la diffusion transculturelle de textes publicitaires passe par l’adoption d’une méthodologie instrumentale de la traduction, à l’image de celle de Nord (1989).

Article body

Background

In spite of its relative youth, the videogame trade boasts unquestionable economic strength: videogames alone generate more revenue than the Hollywood film industry. The main players (Sony, Nintendo and Microsoft) are all companies with a powerful international presence, which is reflected in the promotion of their products worldwide. As the stakes get higher in the quest for market domination, the increasingly ambitious advertising campaigns have budgets to match: Microsoft spent $500 million in the launch of its Xbox console in 2001-2002, and Nintendo and Sony invested around $250 million each in the promotion of the GameCube (2001-2002) and the Playstation 2 (2001), respectively.

The management of such massive campaigns could not be restricted to the choice of formats for dissemination (print, audio-visual); rather, it constituted a complex logistical operation, including TV, cinema and print adverts, third-party co-marketing, product placements in films, competitions and various promotional events in a concerted effort to emerge as victors in what was dubbed by the media “the console wars.” For the purposes of this study, only translatable communicative acts, i.e., adverts, will be taken into consideration.

The marketing directors of videogame companies are faced with the formidable task of targeting a wide cross-section of consumers. Figures released by the Interactive Digital Software Association (established in 1993) show that 97% of the buyers of PC games and 87% of the buyers of console games are 18 or over, and that 84% of the buyers under the age of 18 get parental permission for their purchases (Edge, February 2001: 64). The lack of reliable data as to what proportion of the said percentages are users, or “gamers,” as opposed to non-user “buyers,” only confounds the issue further. It is well known that purchasing power is not necessarily matched to the generation of desire or ambition through advertising, and this, of course, has ethical implications in itself. However, in the case of gaming hardware and software, the fact that those who “use” the product may have it bought for them (as is also the case with toys) has particular implications for the advertisers, who rely on the recognition of a product promoted through non-explicit means (teaser advertising) and the prior knowledge of the brand by their target audience (the gamers, and not necessarily the buyers).

Demographics represents a major concern for the marketing teams of all three main players. Nintendo products are perceived as being “for kids,” Sony Playstation is the choice of the “post-pub generation,” and Microsoft’s Xbox was conceived as a more “grown-up” product. Faced with an increasingly competitive marketplace, all three companies have gone to great lengths to portray themselves as being inclusive, both in terms of age groups and gender. David Gosen (Nintendo’s European Managing director) speaks of “a significant shift in the profile and make up of gamers today. It’s a much broader range” (Edge Specials, issue 7: 15-16), and purports that his company’s products are aimed at “gamers ‘from eight to eighty’” (ibid.: 16). Females have been traditionally ignored by videogame advertisers in the context of a male-dominated industry; yet, in an effort to appeal to this group, Microsoft organised an Xbox women-only preview night, employed female student representatives in order to market the console in universities and targeted women’s magazines. This strategy was a qualified success (for example, Cosmopolitan did not provide any cover, as the product was perceived as “unappealing” to its target readership), which would appear to be representative of a wider issue, as expressed by Rhona Robson (senior programmer at Kuju): “There is no actual way of advertising games to women. […] there are no women’s magazines that I want to buy and while I like what is in the men’s technology magazines, I don’t want to be sold technology with a page three model draped over the cover.” (Edge, May 2002: 78).

Geography is another crucial factor for consideration. In the era of globalization, multinational companies are confronted with the choice to internationalize or to localize the promotion of their products. In other words, they can choose to produce a promotional message that will appeal to the widest target audience possible, irrespective of their cultural setting, or to adapt the message to specific locales, taking into account cultural differences and autochthonous peculiarities. According to Adab, “one feature of this new global culture is a tendency to destroy, or at least seek to minimise, intercultural differences” (2002: 141). She elaborates on the issue by stating that multinationals “assume the existence of a global set of values and expectations, usually in relation to business.” (ibid.: 142). This points to a preference for internationalizing strategies, which, as will be shown below, holds true in the instance of videogame advertising.

The forerunners in this field (Sony, Nintendo and, formerly, Sega) are non-Western (Japanese) companies with regional (European and American) divisions.[1] The competition from Microsoft (USA), a new entrant into this specific sector, raises issues as to different translation and cultural adaptation strategies for the penetration of markets. The notion of ethnocentrism, as outlined below, is of particular relevance in this instance:

Ethnocentrism is a universal phenomenon and is deeply rooted in most areas of intergroup relations. It is defined as the beliefs (knowledge structures and thought processes) held by consumers about the appropriateness, indeed morality, of purchasing foreign-made products in place of domestic ones (Shimp and Sharma, 1987). […] It is posited that generally speaking, members of a high-context culture (i.e. Japan, China) are more ethnocentric than members of a low-context culture (i.e. USA and Western European countries), though there might be some similarities between the two cultural groupings in terms of subgroups (i.e. teen market, upscale consumer market).

Kaynak and Kara, 2001: 46

The carefully orchestrated strategies on the part of the Japanese companies have paid dividends, and they are both firmly installed in the Western markets they targeted, in spite of the fact that, in particular, “Europe is a big headache for any foreign company. While Japan and the US lead the way in terms of cultural relevance, not to mention sheer financial clout, Europe is a curious territory. So many different languages, so many different tastes…” (Edge, December 2002: 50). The European market was a big priority for Microsoft and, although its success in this geographical area was not what the Seattle company had hoped for, it proved a more fertile ground than the Japanese market. Leaving aside technical difficulties (whose negative influence is paramount in a nation accustomed to technological excellence), the media agreed that “Microsoft’s publicity campaign proved vague and ambiguous to the majority of Japanese gamers” (Edge April 2002: 8). Despite the fact that “in the high-context culture of Japan, celebrity advertisements using well-known foreign personalities exert strong influence on consumers in making decisions” (Kaynak and Kara op. cit.: 459), not even the presence of Bill Gates himself at the Japanese launch of the Xbox turned the tide in favour of his product: “Microsoft chose a launch date according to memorable numerology. Unfortunately, February 22, which fell a couple of days before most Japanese companies pay employees their salaries, proved inauspicious.” (Edge April 2002: 8). As a result, “Japanese gamers were left with the impression that Microsoft is incapable of adapting to local market conditions” (ibid.: 8-9).

Translation theory and marketing

In spite of their apparent disparity, the disciplines of translation theory and marketing interface to a large extent in the context of cross-cultural advertising. It can be assumed that the translation of publicity material involves the transfer of the intended source message into different target cultures, although not necessarily different target languages (dissimilar strategies can be applied for the promotion of a product in separate markets that share a common language, such as the UK and the USA, or Spain and Latin America). This is also a core concern for multinational marketing.

Adab states that “From a functionalist perspective, whether or not a target text is a ‘good’ translation will depend on the extent to which it can be used by the intended reader for a pre-determined purpose.” (op. cit.:136). The functionalist approach is also central to marketing: a good advertisement will be one that achieves “a pre-determined purpose” (i.e., awareness, sales) by means of useful communication with its target audience. Skopos theory, introduced by Reiss and Vermeer (Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie, 1984), which postulates that translation strategies should be determined by the function of any given translation, is particularly relevant to the translation of promotional materials, as is audience design: if an advertising text does not fulfil its intended purpose in a language other than that in which it was originally conceived and devised (taking into consideration potential variations in respect of its target audience), the quality of the translation can be called into question.

Two further issues can be derived from the above. Firstly, a study of the translation of advertising material cannot be confined to the analysis of language transfer, as the effectiveness of advertisements is contingent upon the successful linkage of (audio)visual elements (from something as elementary as their layout, to the complexity of the cinematic images shown on TV/pre-film commercials), media of dissemination and/or text. Secondly, the identity of what is being translated merits further consideration. If we assume that we translate “words,” or textual units, the translation act is restricted to the rendering of a pre-existing text into a different language. If to the rendering of a text in a foreign language we add the modification of a set of images and/or sounds in an act of cross-linguistic, cross-cultural communication, the confines of this “narrow” approach to translation are expanded. If, as argued elsewhere (cf. de Pedro 1996), what we translate is a message, any form of advertising material for a given product would be, in itself, a translation of the basic, underlying message of advertising (i.e., “want this/buy this”), whether or not it involves linguistic transfer, and a total or partial modification of images and sounds. Thus, all versions of an advertisement, however different in nature, are manifestations of a generic source “text,” persuasive as it may be in tone, but essentially imperative in nature. Translation ceases to be reproduction, or even re-creation, and it becomes creation in its own right.

The aforementioned issue of localizing vs. internationalizing strategies, central to advertising discourse in an increasingly globalized market, is closely related to the long-standing debate within translation scholarship on naturalizing vs. foreignizing strategies. To what extent would consumers favour an advertising strategy that recognizes their cultural identity over a campaign essentially foreign in nature? Foreignness has undeniable appeal among certain consumer segments, as the ability to grasp foreign concepts and to understand a foreign language is associated with social prestige, or because it fosters notions of belonging to a global community. On the other hand, recognition may be more conducive to a positive attitude towards the advertising message. Internationalizing strategies bank on the assumption that it is possible to reconcile both, since the boundaries between cultures have been eroded by the globalization process: it is now possible to generate communicative acts to which a global audience can supposedly relate on the same grounds. Marketing practitioners exploit this circumstance in order to minimize costs and create a unified image of a product or service.

Finally, there have been calls arising from marketing experts to depart from the traditional focus of advertising theory, based on behavioural sciences, and to embrace a linguistic approach. Boutlis posits that: “Advertising should be less informed by psychology and sociology (which, generally, presupposes a passive ‘subject’ who can be prodded like a lab animal, ‘shrunk’), and more versed in semiology – the science of actively constructing, interpreting signs and symbols as the basic blocks of human experience.” (2000:19). The notions purported within this approach will be familiar to those who espouse linguistic and cultural theories of translation alike:

The self-referentiality of signification, then, amounts to the commercialisation of -culture: culture becomes an industry in itself – it becomes fashion, self-conscious stylisation. There are no longer any stable ‘norms,’ rites, beliefs, mythologies […] which are faithfully followed, re-inscribed over time by the great majority – what Lyotard calls ‘meta-narratives.’ Instead, we have the open conflation of signs; a proliferation of images.

ibid.: 9

Semiology is a discipline that has informed translation theory, implicitly or explicitly, since its advent as a discipline in its own right, and thus it places this postmodern conception of marketing very close to its core.

The (non)translation of adverts

A field such as advertising, whose main objective is to achieve the maximum public exposure possible, leaves itself open to constraints that not only arise from cultural preferences, but also from legal mechanisms that may vary from country to country. For example, Sega’s signature line for its Dreamcast console, “Play up to six billion players,”[2] was banned by the British Independent Television Commission (ITC), as it was found to be in breach of its standards (Edge, December 2002: 47). Yet, in some cases, the perceived need to appeal to a rebellious, non-conformist demographic segment leads the promoters of videogame industry products to test the limits of lawfulness, which, once more, can be conducive to cross-cultural friction. When the British division of the software developer Acclaim, much to the annoyance of the Department of Transport, initiated a publicity stunt promising to reimburse speeding fines imposed on drivers on the release date of the Playstation 2 game Burnout 2: Point of Impact (11 October 2002), their French counterparts were displeased. The press officer of Acclaim France issued a statement explaining: “A l’inverse de nos homologues anglais, nous ne souhaitons pas faire l’apologie de la vitesse, qui pour une grande part est responsable de nombreux accidents sur nos routes, ni l’encourager” (quoted in:www.overgame.com ) [“In contrast with our English counterparts, we are neither inclined to condone speeding, which is largely responsible for a substantial number of accidents on our roads, nor to encourage it.”; my translation].

Videogame advertising campaigns have often courted controversy in ways that often transcend cultural boundaries. Taboos are called upon in order to attract public attention, in seeming agreement with Oscar Wilde’s much-quoted maxim to the effect that “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” In 2002, Acclaim were criticized for approaching families of the recently deceased offering to pay for the funeral of their late relative in exchange for them advertising Shadowman: 2econd Coming on the relevant gravestone. Accusations of xenophobia and incitement to violence were ripe when Sega released a series of adverts based on national (German, French and English) stereotypes in order to promote its Dreamcast console. Microsoft’s Xbox television advert “Champagne” (see the official website: www.playmore.com ), was banned by the ITC, following a public outcry: it depicted a baby being ejected from his mother’s womb and travelling through the air at great speed as he grew progressively older, until he, as an old man, violently crashed into a grave. The closing frames of the advert showed the Xbox’s slogan: “Life is short. Play more.” The advert was, however, the recipient of the prestigious Lion D’Or at the International Advertising Festival (Cannes, July 2002).

The creator of the “Champagne” advert, Bartle Bogle Hegarty Ltd. (based in London), was the agency responsible for the promotion of the Xbox in Europe, and had previously seen its contract with Microsoft cancelled (March 2002). The account was transferred to Interpublic’s McCann-Erikson, which was already responsible for the advertising of the Xbox in USA and Asia. Microsoft explained that the decision had been taken so as to consolidate the promotion of its console by commissioning the work to a single global agency, and not because of any dissatisfaction regarding the work of the British agency.

Whatever Microsoft’s reasons may have been, its strategy is consistent with a growing trend in the advertising of global products, namely the increasing concern with the portrayal of a unified corporate image that is comprehensible across cultural boundaries. There are economic arguments that support these tactics. Douglas (1984: 62) quotes Lionel Godfrey (at the time, European co-ordination director of the advertising agency Leo Burnett) as stating: “Many reasons are often quoted for running the same campaign in many countries. They include savings in production costs, savings in management time, the development of a unified image and the growth of international media, such as satellites.”

In the era of global communication via the Internet (chat groups, discussion forums, “viral” advertising), the statement above is particularly relevant. Ambler records that: “in an analysis of the entries to the 1998 IPA Advertising effectiveness Awards […] reveals that the traditional persuasion theory (née AIDA [Attention ➔ Interest ➔ Desire ➔ Action]) remains, after 100 years, the most frequent practitioner model of how advertising works.” (2000: 299). In stark contrast to this, it can be argued that in the advertising of the videogame industry desire precedes any other consideration: brand-awareness makes this possible. Previous knowledge or experience of, or, indeed, loyalty to, goods produced by a given manufacturer prevail over any specifications that may characterise new releases. Kaynak and Kara’s elucidation of two key concepts appears to underpin this assumption:

Intrinsic cues are physical attributes of a product whereas extrinsic cues are related to the augmented part of a product such as brand name, labelling a packaging […] It is believed that consumers are generally more familiar with extrinsic cues than intrinsic cues, and use them to organise their belief structures and knowledge bases about various products/brands.

op. cit.: 458

Thus, affiliation with a product, which, in turn, leads to consumption, is established on the basis of parameters that supersede advertising. Boutlis contends that, in our times, “The dialectic between ‘truth’ (production) and ‘appearance’ (advertising) is radically subverted. ‘Appearance’ becomes the only truth. […] branding becomes just as, if not more, important, as the ‘substance’ of the product.” (op. cit.: 11). The advertising of videogame-related products confirms this statement: global advertising campaigns are frequently identifiable as marketing a certain product merely by the presence of a logo, whilst the images and sounds used bear no relation to the product in question and no information is provided as to its characteristics or capabilities. This may seem at odds with the reliance of the industry on technical prowess; -however, it makes perfect sense, as the trust of the target market has been earned previously. Ambler describes this phenomenon as “heuristic processing,” which “involves deductions or rules of thumb derived from previous experiences. This is not product usage experience but advertising processing experience (e.g., Japanese manufacturer of a camera equals ‘good’)” (op. cit.: 304). Furthermore, all information regarding the product that may be required can be attained by other means, such as the Internet or specialized magazines, and would appear to be redundant for those “in the know” if included in an advert, thus reducing its appeal.

Thus, iconography becomes essential. Following on Elliot and Wattanasuwan’s thesis (1998), Boutlis propounds that “in a plural society, consumers construct identity through consumption, adopting brands as symbols of self and social identity. Brands are used to counter threats posed by postmodern fragmentation.” (op. cit.: 18). Hence the prevalence of the symbol both in print and television advertisements for videogame products and the relevance of semiology in the analysis thereof. All Nintendo, Sony Playstation and Microsoft Xbox logos are registered trademarks, as are the symbols on the main buttons of the Playstation joypad (cross, triangle, square and circle).[3] The usage of these symbols in global television and print advertising ensures that:

A unified corporate image is preserved and becomes instantly recognizable (although images may vary in accordance with national (culturally-determined) tastes and/or legal constraints.

Text is not required in order to convey a message to the intended target audience.

Cross-cultural communication is thus achieved without having to resort to linguistic translation.

An example of this is Sony’s pan-European campaign for its Playstation 2, for which the work of the prestigious Hollywood director David Lynch was commissioned. The result was a series of short films (all of which can be downloaded at: media.ps2.ign.com/articles/099/099423/vids_1.html and www.lynchnet.com/ads/). The bizarre pictures (see examples) provided no indication for the viewer as to the nature of the product that was being advertised, until the Playstation logo, along with the PS2 slogan “The Third Place” (which was freely translated into French and Spanish as “Le troisième monde” [“The third world”] and “El otro lado” [“The other side”], respectively) flashed on the screens.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

The dissociation of the advertising message in itself and the product underscores the industry’s reliance on brand-image. It flouts the Gricean maxim (1975) according to which a communicative event should “avoid ambiguity and obscurity.” It is, however, representative of a trend in modern advertising, as suggested by Boutlis: “Ads today are increasingly abstruse, open-ended, conceptual. At times, the product or brand is hardly mentioned – the product as anti-hero.” (op. cit.: 14). He uses this phenomenon in order to uphold his tenet that: “Postmodern consumers are not simply manipulated by ads; they respond to them on a mediated, ‘knowing’ level. As such, they react best to ads that are irreverent and self-referential.” (ibid.: 3), in contrast to a more traditional interpretation of advertising, i.e., the manipulation thesis, rooted in Marxist philosophy. This thesis is based on the hypothesis that advertising creates “commodity fetishism”: “it mystifies products, exaggerating their value to us.” (ibid.: 6). However, it could be argued that, by avoiding linguistic communication (which, in turn, renders text translation redundant) and creating a “cult of the image,” the mystification of the product is complete.

The promotional strategy for the Playstation 2 also involved country specific adverts. The examples provided belong to the French campaign (they were both created by TBWA\PARIS), and their nature may explain why they would be deemed to be inappropriate or unacceptable in different cultural frameworks.

Figure 7

Figure 8

The overt sexual overtones of “Joypad” are clearly intended to be negotiated by the audience: the image resembles a Playstation joypad, and a close inspection of the photograph reveals that its trademark buttons are embossed on the model’s shorts. The expectation-confounding “Renaissance” was awarded Grand Prix in the press category and the Lion d’Or in the poster category at Cannes 2002.

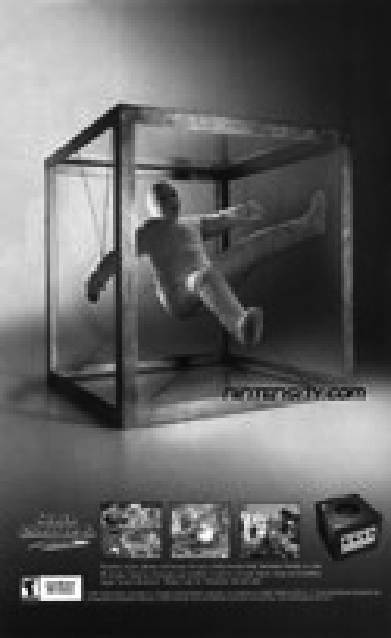

When Nintendo launched its GameCube, the television and cinema campaign (designed by the global agency Leo Burnett) centred on a surreal set of images that portrayed people enacting “in real life” scenes related to seven of the games available for the console in the confined space of a glass cube, “showing the blurred line between reality and the escapist fantasy of the gaming world experienced through the Nintendo GameCube” (www.cube-europe.com/news.php?nid=1943). The adverts, used in seventeen different countries, concluded with the slogan, “Life’s a Game.”[4] Still photographs mimicking the films were used in the print adverts.

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

As can be seen from the examples shown, a basic element of linguistic translation was introduced in these adverts: informative texts about the product and related goods (games) were included in the relevant languages.

In fact, the advertising of videogame products does not always exclude linguistic translation. As well as literal translations of the type indicated above, other strategies have been applied in cross-cultural advertising. The introductory campaign for the Playstation in Europe (1999) featured the promotional film “Double Life” directed by Frank Budgen (see: www.gorgeous.co.uk), which was structured around the eponymous poem reproduced below:

For years I’ve lived a double life.

In the day I do my job; I ride the bus, roll up my sleeves with the hoi polloi.

But at night I live a life of exhilaration, of missed heartbeats and adrenaline.

And, if the truth be known, a life of dubious virtue.

I won’t deny it. I’ve been engaged in violence. Even indulged in it.

I have assailed adversaries, and not merely in self-defence.

I’ve exhibited disregard for life, limb, and property,

And savoured every moment.

You may not think it to look at me,

But I have commanded armies and conquered worlds.

And though, in achieving these things, I have set morality aside,

I have no regrets.

For though I have led a double life, at least I can say

I have lived.

When the text was translated into Spanish, the text was reduced to the following lines:

Desde hace años llevo una doble vida. De día trabajo, pero después, después, pues… mi corazón y mi adrenalina se disparan. Al verme jamás pensarías que he dirigido ejércitos, que he conquistado mundos. Yo sí que puedo decir… que he vivido.

[For years I have lived a double life. During the day, I work, but afterwards, afterwards, well… my heart and my adrenaline go wild. You may not believe it to look at me, but I have lead armies, I have conquered worlds. I can say… that I have lived”; my translation].

According to Veres (2002), this advertisement communicates the notion that “el juego suponía la posibilidad de librarse al antojo del consumidor de las desgracias del mundo cotidiano.” [“Gaming implied the possibility for consumers to rid themselves at will of the misfortunes of everyday life”; my translation]. This may be so, but the English text went further: indulging in violence and setting morality aside, with “no regrets,” emphasize the separation of real life (going to work, riding a bus, mixing in with other people) and the world of videogaming (killing, maiming, stealing, leading armies). This distinction (“in the day”/ “at night”) does not emerge from the Spanish text, whereas the English text makes it simpler to infer that what is being referred to is two different types of “reality.”

For the launch of one of the titles in its seminal series Zelda (Ocarina of Time), Nintendo of Europe used a television advert which was “localized” for different markets. The English images closed with the controversial caption: “Wilst thou save the girl, or play like one?.” In Spain, the images were accompanied by a text that introduced the gaming experience as being part of a universe that is more valid than the real world [my translation], “un universo mucho más válido que el mundo real” (Veres: ibid.): “Nos convertimos en ese héroe solitario que debe combatir el mal afrontando toda clase de peligros. Queremos vivir esta experiencia en solitario para identificarnos más con el personaje y sentirnos así más héroes todavía” [“We become the lone hero who must fight evil, and, in doing so, faces all manner of dangers. We want to experience this on our own, so that we can identify ourselves further with the character, and become, in our minds, even more heroic”]. The explicit sexist overtones have disappeared from the Spanish accompanying text, but the core promotional concepts are present in it: the “lone hero” who embarks in a quest against evil reminds the audience of the stories of times gone-by, as does the archaic verbal tense (“wilst”) and personal pronoun (“thou”) in the English slogan. This could be considered an example of what Adab (op. cit.: 141) describes as a situation when “the target text is produced on the basis of a set of information and concepts rather than on a source text.” As argued above, this strategy can be considered as a form of translation, although there is no “original” source text in writing to transform, if we assume that “when people communicate, they communicate meaning” (de Pedro 2001: 109), and not necessarily “words.”

In a more radical departure from traditional interpretations of translation, the procedure known as “copy adaptation” (i.e., the adaptation of the words and/ or images and sounds of an advert, normally for the purpose of its dissemination in different cultural contexts) can be cited. An example of this technique is the print advertisement for the game “Golden Sun,” for the Game Boy Advance SP handheld console. The same central image (a picture of the console with flames burning through its screen) was used in Great Britain and France and the slogan was translated literally (“Play with fire”/ “Jouez avec le feu”). However, whereas the accompanying English text consisted of reviews of the game from specialized magazines, the French text built up the gaming experience by compelling its audience to play, by means of a succinct, implicit, outline of the characteristics of the game:

Voyagez vers une terre où le feu, le vent, la terre et l’eau sont des armes toute puissantes. Où sortilèges et épées règnent en maître. Et où une communauté d’aventuriers téméraires luttent contre les ténèbres pour la destinée du monde.

[“Travel to a land where fire, wind, earth and water are the most powerful weapons; where magic spells and swords rule supreme; where a group of fearless adventurers fight against the forces of darkness to save the world.”; my translation].

In a reversa l of the same technique, the print advertisement of the game “SoulCalibur” (for Playstation 2 and Xbox) showed the same peripheral images (the box cover for the two formats and two stills from the game) and the same text, in English and French (respectively: “Weapons featured not in game”/ “Armes non disponibles dans le jeu” and “Fight with the best range of weapons in beat’em up history”/ “Combattez avec la plus grande variété d’armes de l’histoire des jeux de combats”), but changed the main picture: whilst in the British version two actors brandished a string of sausages and a bunch of flowers, in the French version the same two actors attacked each other with a filled baguette and a cucumber.

Finally, it can be propounded that a total transformation of both images and text (an extreme form of copy adaptation) can be considered as a form of translation of the underlying message of an advertisement (“buy this”/ “want this”). In the framework of functionalist translation, Nord describes the “instrumental approach” to target-text generation[5] as one that seeks to recreate the function of the source text in a different cultural context: “[the receivers of the target text] are the new addressees of the source text” (1991: 210). This construct (essentially textual in nature) can be extended to encompass images and/or sounds, since they are both integral parts of the message (of the meaning to be conveyed) in the case of advertisements. Thus, as Adab remarks, it would be consistent with what Hewson and Martin call a “homologon” (1991: 48): “translation seeks to transfer a specific message, by whatever means will best ensure its accessibility for the intended TL reader.” (Adab op. cit.: 144).

In the light of this premise, the introductory print campaign for Microsoft’s Xbox in Japan merits analysis. In contrast to the American and European approaches, it focused upon a low-tech image of the console. Whereas the logo of Microsoft’s Xbox, a green X, was the key to introduce the console in Japan (enormous billboards and banners on buildings preceded the launch of the system), the actual promotional campaign featured hand-written sketches of the machine itself on crumpled pieces of paper, mimicking various stages of its development.

Figure 14

The US company was probably wise to appeal to the Japanese sense of humour with this advert, given the fact that the Xbox was in direct competition with considerably less bulky[6] and, arguably, more aesthetically pleasing local products (Sony’s Playstation 2 and Nintendo’s GameCube). In a country where small is not merely beautiful, but also practical (given the size of the average abode), and where technological capabilities, impressive though they may be, are hardly going to astound a people whose economic background is firmly grounded on the manufacturing of high-tech instruments, a less aggressive promotional approach is better positioned to win over any potentially ethnocentric consumers.

Conclusions

It would appear that an instrumental approach to translation, as described by Nord (1989: 102; see above) is the one that suits the cross-cultural dissemination of adverts: the intended target audiences need to be addressed directly, rather than being informed of a message that has been generated in a context that is alien to them. However, in the era of globalization, cultural boundaries are increasingly blurred and, as a result, “cultural contexts” have expanded beyond their original geographical confines. Furthermore, in the specific case of the videogame industry, “alien-ness” (both in the sense of “foreignness” and of “strangeness”) seems to be a valuable commodity.

Even when they have large budgets at their disposal, the promoters of videogame products operate within financial restrictions. Whilst country-specific print adverts may be created (cf. “Joypad” and “Renaissance”), those that are broadcast on television (by far, the most expensive medium of dissemination) tend to stay the same (cf. the Playstation 2 campaign) or be minimally modified (cf. Nintendo campaigns), at least for a given region.

There is a notable reliance on images (still or moving pictures, as well as logos) over language in the marketing of such products, which may be interpreted as an acknowledgement of the universality of visual communication, as opposed to the linguistic and cultural specificity of texts. This is, of course, arguable, as the same image, or even the same colour, can elicit very different responses in different countries, and the filming and photographing of different scenarios and images seems to contradict this hypothesis (cf. “SoulCalibur” French and British adverts). The deployment of this strategy can be explained by the existence of legal constraints in operation (cf. Dreamcast’s slogan), but also because of culturally determined factors, such as taste and perception of taboos (cf. “Champagne” television advert).

One additional factor merits attention: the need to appeal to a “knowing” audience emphasizes the importance of symbols (logos, the glass cubes in the Nintendo adverts) over the presentation of factual information by means of linguistic communication. As Boutlis states, it would appear that “In contemporary consumer society, what matters is not so much what is being sold as the ongoing profligacy of consumption. Consumption is a form of participation and validation of the culture – a value in itself.” (op. cit.: 9). Participating in the videogame culture entails the recognition of certain symbols or icons, which, in turn, validates the said culture. Thus, the circle of consumption is complete.

Examples of linguistic translation can be found, however, in the cross-cultural advertising of videogame products:

Literal translation (Nintendo GameCube and “SoulCalibur”)

Free translation (“The Third Place” slogan)

Gist translation (“Double Life” poem)

Generation of new text (based in a set of common features) in the context of copy adaptation (“Zelda”)

Nonetheless, it seems that internationalizing strategies (which imply a degree of -foreignization) are more prevalent than localizing strategies in the global campaigns for these products. Whilst different regions may have preserved their overall cultural singularity, certain demographic segments (young, relatively affluent consumers, in this instance) share a common identity that transcends geographical borders; hence the importance of symbols and images in the communicative acts that conform advertising. If to this we add the ascendancy of English as a lingua franca in cross-cultural communication, it is possible to conclude that “language, rather than a flexible, transformable element, is seen as an obstacle. […] The interest now seems to have shifted […] to determining how many people are going to be reached by an advert at a time, and targeting that audience.” (de Pedro 1996: 33).

Does this signal the demise of translation as a meaningful activity in the cross-cultural communication of promotional messages? Not necessarily. Linguistic transfer does take place in certain cases, as indicated above, but, perhaps more importantly, the transfer of an advertising message, as a whole, requires the work of individuals who are bilingual and bicultural, to use what Lodge called a “rather ugly phrase” (1984: 20), that is to say: translators. If we cease to perceive their role as one that revolves around language alone and to exclude non-verbal communication from their remit, translators will truly become, and will be perceived as, full-fledged cross--cultural communicators.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for their help and support in this project: Dr Raphaël Costambeys-Kempczynski, of the Université Paris III – Sorbonne Nouvelle, Ms Isabelle Pérez, of Heriot-Watt University (Edinburgh), and, especially, Dr Andy Park. Thanks are also due to M. Sébastien Kohn, of overgame.com, for kindly allowing me to reproduce images from his website’s picture library and for expressing an interest in this paper.

Notes

-

[1]

The emergence of an Australasian (Australia and New Zealand) market is gaining an increasing recognition in the marketing strategies of all main players in the videogame industry.

-

[2]

This slogan was meant to reflect the gaming potential of the console, as it was Internet-ready.

-

[3]

These symbols were inserted in the Playstation slogans in place of the characters “X,” “A” and “0.” As Adab notes, quoting Chesterman: “norm-breaking can be function-enhancing, exploiting deviant spellings, structures, word-order, for communicative effect” (2002: 139).

-

[4]

The slogan was translated into Spanish as “La vida es un juego” (see: www.meristation.com/sc/noticias/noticia.asp?c=CON&n=5152) which is a remarkable decision on the part of the marketing team, since the omission of the article “un” (so that the slogan would have read: “La vida es juego”) would have established strong linguistic (because of the phonetic resemblance) and cultural links with the title of one of the best-known plays in Spanish literature, La vida es sueño (1636), by Pedro Calderón de la Barca.

-

[5]

Nord contraposes this approach to the “documentary approach,” in which “the receiver of the target text is informed about a communication event of which they do not form a part” (1991: 210), as the text reports on a communicative act that has taken place in the source culture (cf. Nord 1989: 102).

-

[6]

Due to its large size, the Xbox joypad had to be redesigned for the Japanese market, and it was the one re-launched elsewhere in the new, smaller format, which became the standard.

References

- Adab, B. (2002): “The Translation of Advertising: A Framework for Evaluation,” Babel 47-2, pp. 133-155.

- Ambler, T. (2000): “Persuasion, Pride and Prejudice: How Ads Work,” International Journal of Advertising 19-3, pp. 299-315.

- Boutlis, P. (2000): “A Theory of Postmodern Advertising,” International Journal of Advertising 19-1, p. 3-23.

- De Pedro, R. (1996): “Beyond the Words: The Translation of Television Adverts,” Babel 42-1, pp. 27-45.

- De Pedro Ricoy, R. (2001): “Translatability and the Limits of Communication,” in Grant, C.B. and D. McLaughlin (eds), Language-Meaning-Social Construction. Interdisciplinary Studies, Amsterdam and New York, Rodopi.

- Douglas, T. (1984): Complete Guide to Advertising, London, Macmillan.

- EDGE eds (February 2001): “Sex, Violence and Videogames,” pp. 62-69.

- EDGE eds (April 2002): “Xbox gets off to inauspicious start in Japan,” pp. 6-9.

- EDGE eds (May 2002): “Minority Report,” pp. 72-79.

- EDGE eds (December 2002): “Ex-box?,” pp. 46-53.

- EDGE eds (Specials, issue 7): “Interview: David Gosen,” pp. 12-19.

- Grice, H.P. (1975): “Logic and Conversation,” in Cole, P. and J. L. Morgan (eds), Syntax and Semantics, London, Academic Press.

- Hewson, L. and J. Martin (1991): Redefining Translation. The Variational Approach, London, Routledge.

- Kaynak, E. and A. Kara (2001): “An Examination of the Relationship among Consumer Lifestyles, Ethnocentrism, Knowledge Structures, Attitudes and Behavioural Tendencies: A Comparative Study of Two CIS States,” International Journal of Advertising 20-4, p. 455-482.

- Lodge, D. (1984): Language of Fiction. Essays in Criticism and Verbal Abnalysis of the English Novel, London, Routledge and Keegan Paul.

- Nord, C. (1989): “Textanalyse und Übersetzungsauftrag,” in Königs, F. G. (ed), Übersetzungswissenschaft und Fremdsprachenunterricht. Neue Beiträge zu einem alten Thema, Munich, Goethe-Institut, p. 95-119.

- Nord, C. (1991): Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis, Amsterdam, Rodopi.

- Veres, L. (2002): “El lenguage de la publicidad de los videojuegos: La violencia y la publicidad en los videojuegos,” Caleidoscopio 5, www.uch.ceu.es/caleidoscopio/numeros/cinco/veres.htm

- www.overgame.com

- www.playmore.com

- media.ps2.ign.com/articles/099/099423/vids_1.html www.lynchnet.com/ads/

- www.cube-europe.com/news.php?nid=1943

- www.gorgeous.co.uk

- www.meristation.com/sc/noticias/noticia.asp?c=CON&n=5152

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14