Abstracts

Abstract

Interpreting performance is shaped by three major forces: a) the interpreter’s interpreting competence, b) cognitive conditions on-site and c) norms of interpreting. This research is a descriptive study of norms in the Chinese-English interpreting of Chinese Premier Press Conferences, which reveals the actual norms of consecutive interpreting especially with regard to source text and target text relations. It employs the research paradigm of descriptive translation studies and the analytic tool of shifts. Through inter-textual comparative analysis of the parallel corpus of the on-site interpretation of 11 Chinese Premier Press Conferences (1998-2008), three types of shifts are identified, including Type A shifts (Addition), Type R shifts (Reduction) and Type C’ shifts (Correction). With quantitative statistics of the regularity of the occurrences of shifts and qualitative analysis of every type of shifts in the corpus, four typical norms of ST-TT relations are identified: a) the norm of adequacy, b) the norm of explicitation in logic relations, c) the norm of specificity in information content, d) the norm of explicitness in meaning. This descriptive study of norms based on a relatively large corpus of on-site interpretation can serve as a tentative exploration of the methodology in descriptive interpreting studies. It may also shed new light on interpreting quality studies.

Keywords:

- norms of interpreting,

- descriptive study,

- methodology,

- shift,

- press conference

Résumé

La performance en interprétation est conditionnée par trois facteurs majeurs : a) la compétence de l’interprète ; b) les contraintes cognitives auxquelles ce dernier est soumis sur le terrain ; c) les normes en matière d’interprétation. Le présent article porte sur l’étude descriptive des normes qui ont régi l’interprétation du chinois vers l’anglais lors des conférences de presse du premier ministre chinois, révélant ainsi les normes d’interprétation consécutive en vigueur, en particulier en ce qui concerne les relations entre le texte source et le texte cible. Il s’appuie tant sur le paradigme propre aux études descriptives de traduction que sur l’analyse des écarts. Grâce à une analyse intertextuelle comparative du corpus parallèle recueilli lors de l’interprétation des 11 conférences de presse du premier ministre chinois (de 1998 à 2008), trois types de glissements ont été identifiés : type A (Ajout), type R (Réduction) et type C’ (Correction). Une analyse statistique quantitative portant sur la fréquence des glissements ainsi qu’une analyse qualitative des différents types de glissements repérés a permis de mettre en évidence quatre normes typiques des relations TS – TC : a) l’adéquation, b) l’explicitation des relations logiques, c) la spécificité du contenu informatif, d) l’explicite du sens. Cette étude descriptive des normes, fondée sur un corpus relativement important colligé sur le terrain, constitue une exploration d’une méthodologie descriptive dans le cadre des recherches en interprétation. Elle se veut également une contribution nouvelle aux études sur la qualité d’interprétation.

Mots-clés :

- normes d’interprétation,

- étude descriptive,

- méthodologie,

- écart,

- conférence de presse

Article body

1. Introduction

For a long period in its history, interpreting studies has focused on the exploration of cognitive processing in interpreting behaviors. According to Baker’s observation,

[t]he vast majority of research [on interpreting] has been, and continues to be, devoted to investigating cognitive aspects of interpreter performance. […] Little or no attention has so far been given to investigating constraints which arise from the nature of the role played by the interpreter and the pressures on him or her by other participants in specific settings.

Baker 1997: 111

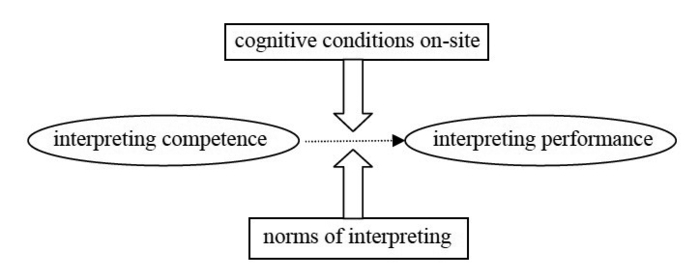

In spite of its significance, the exploration of cognitive-related issues cannot be regarded as being the whole of interpreting studies. An adequate description of interpreting behaviors and activities, as the disciplinary foundation of interpreting studies, requires not only the exploration of internal cognitive processing factors but also the examination of external social and cultural factors. Interpreters’ interpreting performance is shaped by all these factors in combination. The major shaping forces of interpreting performance include: a) the interpreter’s interpreting competence, b) the cognitive conditions on-site and c) norms of interpreting. Their relationship to interpreting performance can be embodied by the figure as follows:

Figure 1

Major shaping forces of interpreting performance

Among the three major shaping forces of interpreting performance, “norms of interpreting” can be defined as the shared values and ideas among interpreters of the profession and users of interpreting service on what the generally-accepted interpreting methods and strategies are and what the right and proper interpreting behaviors are. In descriptive translation studies, “norm” as a descriptive term is used to refer to “regularities of translation behavior” (Toury 1995: 56). It functions on a continuum of “socio-cultural constraints” between the two extremes of “idiosyncracies” and “absolute rules” (Munday 2009: 210). Norms are internalized rules, reflecting the shared values of a social or cultural group on the behaviors of its members (Toury 1980: 51). Interpreting, as a social behavior and activity, is certainly governed by norms. That is to say, norms of interpreting guide interpreters in their choice of strategies in interpreting behaviors and shape the interpreting activities in a socio-cultural context.

The significance of research into norms of interpreting was first proposed by Shlesinger (1989) in the debut issue of Target, which was soon echoed by Harris (1990) and then highlighted by Schjoldager (1994; 1995), Gile (1999) and Garzone (2002). While scholars raised the issue of methodological obstacles involved in the research of norms in interpreting, esp. the difficulty of building up a corpus for describing norms and the representativeness of such a corpus (Shlesinger 1989) and other scholars tried to avert such difficulties by gathering data from experiments in a simulated/didactic situation (Schjoldager 1995), Gile (1999: 99) emphasized the necessity of studying norms in interpreting research by noting that “[norm] is a neglected factor in interpreting research” and it provides “an attractive avenue for new projects.” He rightly pointed out that “interpreting strategies are at least partly norm-based.” Gile exemplified his view by identifying such norms as “maximizing information recovery” and “maximizing the communication impact of the speech,” which he originally named as “rules” that interpreters tend to follow (Gile 1995: 201-204). Garzone, who defined norms as “internalized behavioral constraints which govern interpreters’ choices in relation to the different contexts where they are called upon to operate” (Garzone 2002: 110), explored the ground-breaking significance of norms to the study of quality in interpreting.

2. Research Question

The present study intends to conduct a descriptive study of norms in the interpreting activities of Chinese Premier Press Conferences. It tries to explore what actual norms the on-site consecutive interpreting in Chinese Premier Press Conferences embodies, especially with regard to source text and target text relations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research paradigm

This study employs the research paradigm of descriptive translation studies (Toury 1980; 1995). The norms of source-target text relations are described through the inter-textual comparison between the source text (ST) and the target text (TT). With the comparative analysis, “shifts” in the target text will be identified.

“Shifts” is an analytic tool of norms in descriptive translation studies, which refers to changes in the target text as compared with the source text (van Leuven-Zwart 1989; 1990; Toury 1980; 1995). It must be pointed out that shifts do not mean translation errors and translation errors are not included in the category of shifts. It should also be noted that the necessary changes caused by the systemic formal differences between the source and target texts are not counted as shifts either.

3.2. Data collection and selection of on-site interpreting

This study collected the on-site interpreting data of 11 Chinese Premier Press Conferences, which is held annually from 1998 to 2008. The major speakers of the 11 press conferences are Premier Zhu Rongji (1998-2002) and Premier Wen Jiabao (2003-2008); in addition, there are interventions in the form of questions from journalists of various media throughout the world. Although the speakers might have prepared for the press conferences beforehand, the interactions in the form of questions-and-answers should be categorized as “impromptu speeches.” The on-site interpreting is done by five interpreters (Interpreter 1: 1998, 1999, 2000; Interpreter 2: 2001, 2002, 2003; Interpreter 3: 2004; Interpreter 4: 2005; Interpreter 5: 2006, 2007, 2008). All of them are in-house interpreters of the Interpreting and Translation Section of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In the case of the three interpreters who worked for more than one press conference, a single conference has been selected to represent each interpreter. Therefore, a total of five press conferences (in the years of 2000, 2002, 2004, 2005 and 2008) are selected as representative data for analysis.

3.3. Principles of data collection and selection

Two major principles are followed in the process of data collection and selection.

3.3.1. Control of variables

Considering that interpreting performance is shaped by three major factors – the interpreter’s competence, the cognitive conditions on site and norms of interpreting – and this study focuses on norms of interpreting, the other two variables need to be controlled. Through the data selection of the interpretation of in-house interpreters from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who are generally regarded as representing the seasoned level of professional interpreting competence, the first variable is controlled as much as possible; and through the data selection of consecutive interpreting, in which the interpreter has relatively more time to decide on interpreting strategies, the second variable will not play at such a level as to interfere with the functioning of interpreting norms.

3.3.2. Representativeness of the data

In spite of the difficulty of gathering large-scale homogeneous data in interpreting studies, which is quite necessary for the study of norms, the present study manages to build a relatively large-scale corpus of the interpretation in Chinese Premier Press Conferences based on the live TV broadcast every year. With the major speakers being two premiers of the government representing different speaking styles and five different interpreters (three female interpreters and two male interpreters) working for the 11 conferences, the data are representative.

It is also noteworthy that interpretation for Chinese Premier Press Conferences has always been regarded as being very stringent with little room for the interpreter’s latitude, which is characteristic of diplomatic and political settings (Ren 2000; Xu 2000). If “shifts” can be found in this type of interpreting, then the norms of interpreting inferred in the present study shall be considered as being widely representative.

3.4. Processing of the data

The original data of the on-site interpreting are collected through the audio-video recording of live TV broadcast. With the duration of every press conference varying between one hour 15 minutes and two hours, the length of recording of the five press conferences chosen for analysis is nearly nine hours. The word count of the transcript of the source text in Chinese and the target text in English is 71,730 words. Four steps of processing are done on the data:

transcription of the source text and target text from the audio-video recording;

manual alignment of the source and target texts and making them into a parallel corpus;

annotation of the “shifts” in the target text as compared with the source text;

qualitative and quantitative analysis of the “shifts.”

4. Analysis of the Corpus: ST-TT Inter-textual Analysis

Through inter-textual comparative analysis of the parallel corpus, three types of shifts are discovered, including Type A shifts – “Addition,” Type R shifts – “Reduction” and Type C’ shifts – “Correction.”

4.1. Type A shifts – “Addition”

Five sub-types are identified under the category of Type A shifts: A1 shifts (addition of cohesive devices), A2 shifts (informational addition and elaboration), A3 shifts (explicitation of intended meaning), A4 shifts (repetition), A5 shifts (addition proper).

4.1.1. A1 shifts: Addition of cohesive devices

In A1 shifts, interpreters add either textual cohesive devices or logic connective expressions to their target texts in interpretation to make the implicit textual or logical connection explicit in the target texts.

In example 1, the interpreter adds such textual cohesive devices as so, first of all and logic connective word because. In example 2, the interpreter adds Let me make the following points in order to begin the listing of several points the speaker has made. In example 3, the interpreter adds For instance, which makes the implicit logical connection explicit in the structure of target texts.

4.1.2. A2 shifts: Informational addition and elaboration

A2 shifts refer to the addition and elaboration of background information with situational, contextual and cultural significance in the target text.

In example 4, the interpreter adds for some opening remarks illustrating the situational information of the press conference. In example 5, the interpreter adds (friends) from the press and (Premier) of the State Council of China as complement in background information. In example 6, the interpreter adds (investment) into the building of infrastructure, which is actually specific information embedded in the speaker’s context.

4.1.3. A3 shifts: Explicitation of intended meaning

A3 shifts refer to the phenomenon that interpreters make explicit in the target text what is intended but implicit in the source text.

In example 7, the interpreter makes explicit what is implied in the tone of the speaker by adding actually. In example 8, the interpreter adds new to characteristics, which is intended by the speaker. And in example 9, the interpreter adds we hope that and we believe that, which are implied in the speaker’s message but not explicitly expressed.

4.1.4. A4 shifts: Repetition

A4 shifts refer to two kinds of repetition: repetition of synonymous words or phrases in target language expressions and repetition resulted from the interpreter’s self-correction.

In the above examples, the repetitions of to oppose China and to do something against China and significant link or clear logic are repetitions of synonymous words or phrases; while the repetitions of as the imaginary or as the potential (enemy) and Chinese side or the mainland side are repetitions resulted from the interpreter’s self-correction, because the first part is not accurate and the interpreter must have realized that instantly.

4.1.5. A5 shifts: Addition proper

As a contrast to A2 shifts, the sub-type of A5 shifts refers to the addition of new information which does not exist in the source text.

As are shown by the above examples, what is interesting about A5 shifts is that some new information is added to the target text, such as resource reservation in example 13, so-called (middle class) in example 14 and proper (policy) in example 15. The attitude and evaluation of the interpreter is especially salient to the audience in example 14 and 15.

Statistics of the occurrences of the five sub-types of shifts under Type A in the corpus can be observed in the following graph:

Figure 2

Statistics of the occurrences of the five sub-types of shifts under Type A

4.2. Type R shifts – Reduction

Two sub-types of shifts can be identified in the corpus under the category of Type R: R1 shifts (omission) and R2 shifts (compression).

4.2.1. R1 shifts: Omission

This type of shifts occurs when interpreters omit what they consider to be negligible information from the speaker’s words in their interpretation.

In the above example, the greeting words from the journalist are omitted by the interpreter. What is worth notice is that such shifts of omission usually occur in the interpretation of journalists’ remarks, but not in the interpretation of the Premier’s words, which may imply that interpreters tend to be more loyal to their principal of service (the Premier in the present study) when more than one speakers are involved in the activity.

4.2.2. R2 shifts: Compression

R2 shifts appear when the interpreter compresses loose structures and redundancy in the source text and makes them streamlined in the target language expression.

It is often the case that when the speaker speaks spontaneously on site, their speech tends to be characterized by loose structures, repetition and redundancy. While dealing with that, interpreters are apt to compress the expression in the target text, as are shown by the above examples.

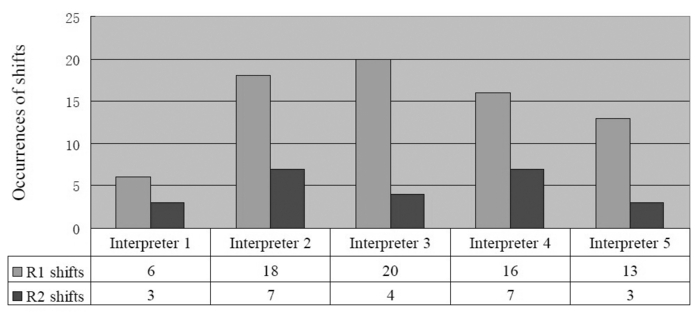

Statistics of the occurrences of the two sub-types of shifts under Type R in the corpus can be observed in the following graph:

Figure 3

Statistics of the occurrences of the two sub-types of shifts under Type R

4.3. Type C’ shifts – Correction

Type C’ shifts occur when interpreters deliberately correct the information or expressions that they believe are inaccurate or wrong.

In example 19, the interpreter may know from his background knowledge that Premier Zhu has not finished half of his term in office by the time of the press conference. Therefore, he corrected that piece of information. In example 20, hearing the speaker say interests … must be protected, the interpreter may judge that only legitimate interests shall be protected, thus the correction. In example 21, maybe there is a slip of the tongue when the speaker says biggest; therefore, the interpreter corrects it as major, which is the information true to the fact.

Statistics of the occurrences of shifts under Type C’ in the corpus can be observed in the following graph:

Figure 4

Statistics of the occurrences of shifts under Type C’

5. Major Findings and Discussion

5.1. Statistics reflecting regularity of shifts

5.1.1. Occurrences of the three types of shifts in each interpreter

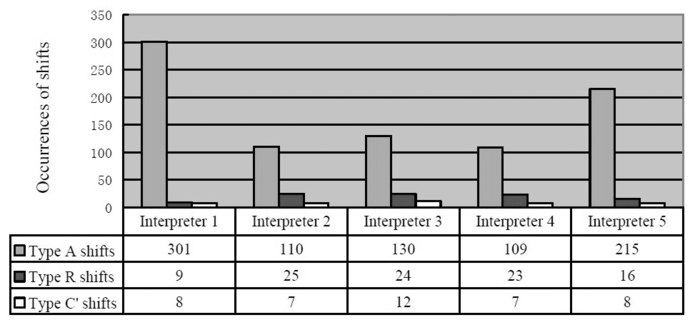

The following graph shows the statistics of occurrences of ST-TT inter-textual shifts under the three categories in every interpreter’s interpretation:

Figure 5

Occurrences of the three types of shifts in each interpreter

It can be observed from the above graph that there are significant occurrences of Type A shifts (Addition) in the interpretation of all the five interpreters and fewer occurrences of Type R (Reduction) shifts and Type C’ shifts (Correction), which implies that interpreters tend to add or elaborate more frequently than reduce and correct in their interpretation.

5.1.2. Average occurrence of every type of shifts across conferences

The average occurrence of every type of shifts across conferences can be seen as an index indicating the regularity of the interpreters’ behaviour of making shifts in their interpretation. Statistics of the average frequency of every type of shifts across the five press conferences in the corpus are shown in the following graph:

Figure 6

Average occurrence of every type of shifts across conferences

5.1.3. Frequency of shifts in the interpretation of each interpreter

The statistics of the frequency of shifts in the interpretation of each interpreter in the corpus are calculated on the basis of occurrences per minute, as is shown in the following graph:

Figure 7

Frequency of shifts in the interpretation of each interpreter

As can be observed from the above graph, the frequency of shifts in the interpretation of all the interpreters ranges from 2.4 occurrences per minute to 6.3 occurrences per minute. The average frequency of shifts across the five interpreters’ interpretation is 3.9 occurrences per minute, which means the interpreter makes about four shifts within every minute while interpreting.

5.2. Norms of ST-TT relations

The above statistics of occurrences of shifts, the average frequency of shifts across all the conferences and frequency of shifts for every interpreter in the corpus as well as qualitative analysis of every type of shifts reveal the existence of four typical norms of ST-TT relations in interpreting as the following:

-

The norm of adequacy in interpretation:

Interpreters tend to adhere to the norm of adequacy in interpretation, according to which they pursue accuracy, consistency and completeness of information conveyed in source texts, mainly through A1, A2, A3 and A4 shifts.

-

The norm of explicitation in logic relations:

Interpreters tend to adhere to the norm of explicitation in logical cohesion and coherence in interpretation as is achieved mainly through A1 shifts.

-

The norm of specificity in information content:

Interpreters tend to adhere to the norm of specificity in information content in interpretation as is achieved mainly through A2 shifts.

-

The norm of explicitness in meaning:

Interpreters tend to adhere to the norm of improved level of explicitness in meaning and message conveyance in interpretation as is achieved mainly through A3 shifts.

5.3. Discussion

It can be seen from the high frequency of A1, A2, A3 and A4 shifts in the corpus that the norm of adequacy plays a major role in the consecutive interpreting of the Chinese Premier Press Conferences. While A5 shifts, Type R shifts and Type C’ shifts may in appearance be considered as exception to the norm of adequacy, their low frequency of occurrences in the corpus suggests that interpreters tend to be very cautious in adding new information, reducing the speaker’s words or correcting the speaker’s mistakes. And the qualitative analysis of the corpus reveals that those types of shifts, which are made by the interpreters with their sound judgment based on good command of relevant knowledge, actually contribute in most cases to adequacy in interpretation and reflect their loyalty to their principle of service.

Acceptability of the target text is another major motive for the shifts in the interpreters’ interpretation, which is evident in their adherence to the norm of explicitation in logic relations, the norm of specificity in information content and the norm of explicitness in meaning in their target texts.

The norms revealed in the present study based on a relatively large corpus confirm what Gile (1999) proposed as the norm of “maximizing information recovery” and the norm of “maximizing the communication impact of the speech,” which correspond to the first norm and the other three norms respectively.

6. Conclusion

This initial trial of descriptive study of norms in interpreting based on a relatively large corpus of on-site interpretation, which reveals four norms of ST-TT relations, can serve as a tentative exploration of the methodology in descriptive interpreting studies. It may also shed new light on interpreting quality studies in that quality assessment should be more norms-based rather than based solely on such static quality criteria as equivalence between the source and target languages.

The deficiency of the present study may be complemented by more description of interpretation in other interpreting modes, e.g., simultaneous interpreting and in various interpreting settings, such as business interpreting, escort interpreting and court interpreting, which can be topics for further exploration.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Ministry of Education Research Fund for Young Scholars in Humanities and Social Sciences (Project 10YJC740092). The author wants to express special thanks to Prof. Mu Lei, Prof. Chu Chi-yu and Dr. Jeremy Munday for their valuable advice.

Bibliography

- Baker, Mona (1997): Non-cognitive constraints and interpreter strategies in political interviews. In: Karl Simms, ed. Translating Sensitive Texts: Linguistic Aspects. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi.

- Garzone, Giuliana (2002): Quality and norms in interpretation. In: Giuliana Garzone and Maurizio Viezzi, eds. Interpreting in 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, 107-121.

- Gile, Daniel (1995): Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Gile, Daniel (1999): Norms in Research on Conference Interpreting: A Response to Theo Hermans and Gideon Toury. In: Christina Schaffner, ed. Translation and Norms. Clevedon: Mutlilingual Matters,99-105.

- Harris, Brian (1990): Norms in Interpretation. Target. 2(1):115-119.

- Munday, Jeremy, ed. (2009): The Routledge Companion to Translation Studies. London/ New York: Routledge.

- Ren, Xiaoping (2000): Latitude of Diplomatic Interpretation [Waijiao kouyi de linghuodu]. Chinese Translators Journal. 143:40-44.

- Schjoldager, Anne (1994): Interpreting Research and the ‘Manipulation School’ of Translation Studies. Hermes, Journal of Linguistics. 12:65-89.

- Schjoldager, Anne (1995): An Exploratory Study of Translational Norms in Simultaneous Interpreting: Methodological Reflections. Hermes, Journal of Linguistics. 14:65-87.

- Shlesinger, Miriam (1989): Extending the theory of translation to interpretation: norms as a case in point. Target. 1(2):111-115.

- Toury, Gideon (1980): In Search of Translation Theory. Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics.

- Toury, Gideon. (1995): Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- van Leuven-Zwart, Kitty (1989): Translation and original: Similarities and dissimilarities, I. Target. 1(2):151-181.

- van Leuven-Zwart, Kitty (1990): Translation and original: Similarities and dissimilarities, II. Target. 2(1):69-95.

- Xu, Yanan (2000): Features in Diplomatic Interpretation of Translation and Diplomatic Interpreters Qualities [Waijiao fanyi de tedian yiji dui waijiao fanyi de yaoqiu]. Chinese Translators Journal. 141:35-38.

List of figures

Figure 1

Major shaping forces of interpreting performance

Figure 2

Statistics of the occurrences of the five sub-types of shifts under Type A

Figure 3

Statistics of the occurrences of the two sub-types of shifts under Type R

Figure 4

Statistics of the occurrences of shifts under Type C’

Figure 5

Occurrences of the three types of shifts in each interpreter

Figure 6

Average occurrence of every type of shifts across conferences

Figure 7

Frequency of shifts in the interpretation of each interpreter