Abstracts

Abstract

Interpreters are often anonymously and flimsily archived, given their subsidiary role in diplomatic exchanges. These fragmentary records pose problems for in-depth studies on ancient interpreters. Japanese monk Ennin’s (794-864) diary documenting his decade-long (838-847) China sojourn, however, provides a delightful contrast to this evidence limitation. Known for its authentic, detailed, and objective descriptions, it contains thirty-eight references to four Sillan (ancient Korean) interpreters, of whom one was an interpreting clerk affiliated with a prefecture in eastern coastal China. He was also Ennin’s longest-serving interpreter, from 839 through 847, having been documented twenty-three times. This interpreting functionary, Yu Sinǒn, worked in a regional office of a Sillan enclave and assisted visitors from Japan and Silla. His work, apart from language mediation, included liaising, trading, logistics and message go-betweens. As a civil servant, this Sillan interpreter was expected to be law-abiding. Yet in his mediating services for Ennin, he frequently flouted the legal limits. In the process, he was given monetary rewards, although later textual hints suggest that his mediation for the Japanese monks was primarily based on goodwill and friendship. The detailed descriptions in Ennin’s travelogue offer us first-hand information about an interpreting official’s infringements of the Tang Chinese laws. However, was it not exactly his official position, with easy access to institutional networks and legal bureaucracy, which enabled him to work around the loopholes? This case of an interpreter and his patron provides valuable evidence for the development of their initial professional ties and subsequent personal bonding. It also speaks of the arbitrary boundaries between interpreting officials and civilian interpreters in first-millennium East Asian exchanges.

Keywords:

- Sillan interpreters,

- first-millennium East-Asian exchanges,

- 9th-century China interpreting,

- history of interpreting,

- foreign interpreters

Résumé

Les interprètes sont souvent anonymes ou ce qu’on en sait est mal documenté, notamment en raison de leur rôle accessoire dans les échanges diplomatiques. Les données fragmentaires auxquelles nous avons accès posent évidemment problème au moment de mener des études approfondies sur les interprètes d’autrefois. Le journal du moine japonais Ennin (794-864), dans lequel il décrit son séjour de près de dix ans en Chine (838-847), constitue une heureuse exception. Reconnu pour ses descriptions authentiques, détaillées et objectives, ce journal fait 38 fois référence à quatre interprètes de Silla (ancienne Corée). L’un de ceux-ci était un interprète rattaché à une sous-préfecture de la côte orientale de Chine, en plus d’avoir agi à titre d’interprète d’Ennin de 839 à 847. Ce dernier en fait mention à 23 occasions. Ce fonctionnaire interprète, Yu Sinǒn, travaillait dans le bureau régional d’une enclave de Silla et avait pour fonction de répondre aux besoins des visiteurs du Japon et de Silla. En plus d’agir à titre de médiateur linguistique, il agissait comme intermédiaire et messager, et remplissait des tâches liées au commerce et à la logistique. En tant que fonctionnaire, on attendait de lui qu’il respecte la loi. Pourtant, dans le cadre de ses services de médiation pour Ennin, il passait souvent outre les limites légales. Il était rémunéré pour son travail, quoique des textes ultérieurs suggèrent que la médiation pour les moines japonais se fondait avant tout sur la bonne volonté et l’amitié. Les descriptions détaillées contenues dans le récit de voyage d’Ennin constituent des sources d’information primaires sur les transgressions d’un interprète officiel sous les Tang. Par ailleurs, n’était-ce pas précisément grâce à cette fonction officielle qui lui donnait accès aux réseaux institutionnels et à la bureaucratie juridique, que l’interprète arrivait à déjouer le système ? Ce cas de figure d’un interprète et de son maître nous fournit des renseignements importants sur l’évolution de leur relation, d’abord professionnelle puis personnelle. Cela démontre également le caractère arbitraire des frontières entre interprètes officiels et civils dans le cadre des échanges en Asie de l’Est au cours du premier millénaire.

Mots-clés :

- interprètes sillais,

- échanges en Asie de l’Est au premier millénaire,

- interprétation en Chine au ixe siècle,

- histoire de l’interprétation,

- interprètes étrangers

Article body

1. Introduction

Roland (1982/1999) was one of the pioneer researchers drawn to interpreters’ linguistic and non-linguistic roles in international politics. Surprisingly, though, for decades, studies on interpreters’ non-linguistic duties continue to be under-represented in the literature. Is it because of the scarce empirical data about interpreters throughout history? Bowen, Bowen et al. (1995) propose that, in the context of European imperialism for example, one important archive is in memoirs, correspondence, travel writings, and diaries of colonial officials. In fact, from the 1990s onwards, translation researchers were inspired to examine the theoretical link between translation and colonialism. Numerous colonial and postcolonial contexts have since been examined for insights pertaining to interpreters’ duties, cultural identity, and loyalty (Bassnett and Trivedi 1999; Lawrance, Osborne et al. 2006). Most colonial memoirs or diaries contain anecdotes about the adventurers’ deployment of and experience with indigenous bilinguals. These would be valuable data sources for a study of colonial interpreters. These interpreters, or local polyglots, serving the foreign intruders were often given a functional title of interpreter. It is not uncommon, however, that these ad hoc and amateurish interpreters were in fact captives or sometimes slaves who happened to be gifted with languages in demand. Writing in 1636 about the Spanish Conquest, Juan Rodriguez Freyle (in Ostler 2005: 341) recalls,

General de Quesada tried to find out what people were arrayed against him. There was an Indian whom they had captured with two cakes of salt and who had led them to where they were in this realm, and who through conversation already spoke a few words of Spanish. The General had him ask some Indians of the country whom he had captured to serve as interpreters.

The notions of colonizers and colonized are keys to understanding, for instance, the tension between the colonial officers and the interpreters in captivity (Cronin 2000). Niranjana (1992) argues that translation occurred primarily within the asymmetrical power between the colonial adventurers and the indigenous interpreters. The picture of the interpreter-patron relation was not entirely bleak though. At least in the colonial African context, local interpreters were valued as crucial “hidden linchpins” in the administration, as they “translated, mediated, and recorded” the interactions between the colonizers and the colonized (Lawrance, Osborne et al. 2006: 4).

In this article, I intend to explore an alternate dimension of interpreters in adventurers’ diaries. The adventurer was Japanese monk Ennin, who spent ten years sojourning in China. During his travels, he recorded plenty of encounters with Sillan interpreters who gave him linguistic and non-linguistic assistance. As we shall see in his travelogue, Sillan interpreters enjoyed a more egalitarian relation with their patrons. Such a liberal working relation in pre-modern times between interpreters and their clients was unorthodox. What, in the social context of the inter-lingual milieu, would encourage the development of such symmetrical relations? Ennin’s diary provides us with some answers.

Ennin’s command of written Chinese was fine,[1] but he had little command of vernacular Chinese. This verbal deficiency therefore became a central feature of his sojourn, in which Sillan interpreters, usually proficient in the Japanese, Chinese, and Sillan vernacular,[2] played a major part as mediators. Through its descriptive entries about the contexts of civilian exchanges, Ennin’s diary recaps interpreters’ traces in East Asian communication. In this 80,000-word Chinese diary, four Sillan interpreters were described, and one, with whom Ennin had no acquaintance, was mentioned as an anecdote (Ennin 2007: 154).[3]

This study is significant in two regards. First, the diary, containing dozens of references to Sillan interpreters,[4] suggests that their deployment was probably not an isolated event, but evidence for their important roles, over centuries, in East Asian exchanges. Second, this diary presents evidence suggesting the blurred distinction between interpreting functionaries and civilian interpreters in 9th-century coastal China. By examining an interpreting clerk’s decade-long work for Ennin, I argue that the interpreter’s official status in fact gave him the mandate to compete for odd jobs relating to language mediation, logistics, trading, and liaising services, which could have otherwise been undertaken by civilian interpreters. The clerk’s civil servant identity also gave him a distinct edge and leeway to manipulate the law, which was necessary to secure Ennin’s better interests.

This article begins with the historical background of United Silla (668-935) and Sillan enclaves, followed by a brief introduction to Ennin and his travelogue. It then presents preliminary quantitative data about Sillan interpreters, before shifting focus to a qualitative analysis of the interpreting clerk, Yu Sinǒn. This is followed by a core section profiling four kinds of the clerk’s controversial assistance to Ennin over nine years. These empirical data serve to illustrate the arbitrary distinction between official and civilian interpreters in 9th-century China.

2. Background of United Silla and Sillan enclaves

Geographically, the Korean peninsula is connected with northeastern China. Before its unification in 688, Silla (58 BC-688 AD) co-existed with two stronger states: Baekje (or Paekche) and Goguryeo (or Koguryŏ). In the Three Kingdom era (Figure 1), Silla was the weakest, situated on the southwestern part of the peninsula.

Figure 1

Map of the Three Kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula around 600AD[5]

Its remote position from the hinterland explains why Silla lagged behind in forging ties with imperial China and learning from Chinese culture and institutions. In fact, Silla relied on Baekje in its Chinese learning,[6] since the latter started learning from China much earlier than its counterparts, nurtured far more Chinese experts, and amassed a large collection of classics and scriptures.[7] For centuries, these states frequently fought over territorial disputes. They trumpeted their vassal loyalty to China in order to lobby for peninsular supremacy. Eventually, with its astute statecraft and shrewd diplomacy, Silla emerged and obtained Tang China’s support in its unification warfare. After the unification, the entire peninsula was ruled under United Silla until 935. This study falls within the timeframe of United Silla. The term “Sillan” therefore refers to ancient Koreans from United Silla, regardless of their ancestral origins in the Three Kingdom era.

Ennin’s travelogue gives graphic details about Sillan interpreters who helped him and Sillan residents or traders he encountered in China (Jin 2012). It bears testimony to the dynamic interaction of East Asian countries and the prominent distribution of Sillan enclaves in eastern coastal China (Zhao 2003). These enclaves, in the form of villages or towns (Chen 1996), were rooted in centuries of coastal civilian and commercial exchanges with the peninsula. Under the reign of Qin China (221-206 BC), tens of thousands of people fled to the southern peninsula hoping to escape from its notoriously harsh labor and brutal penalties. In Han China (206 BC-220 AD), when the government became less autocratic, many ethnic Chinese returned. Around 108 BC, after pacifying some tribal conflicts on the peninsula, Han China established four commanderies that governed parts of its territory and east China (Zhang 2006; Kyung 2010). At these early times, therefore, China regarded the peninsula not as another country, but as one of its provinces. So the movement of the two peoples was considered internal relocation. In times of peninsular calamities, such as drought, famine or political turmoil in the late 8th century,[8] China was naturally taken as a safe haven because of its proximity (Chen 2011). Moreover, smuggling and trading of Sillan slaves was blatant in coastal China at the time (Zhao 2003). Inevitably, then, Sillan migrants from different sources were settled or naturalized in China for generations.

3. Ennin and his travelogue

Ennin (793-864) went to China to pursue the Buddhist Dharma in 838, traveling with the Japanese embassy as a scholar monk. Yet, he was forbidden by the authorities to undertake an inland pilgrimage. The restrictions originated from his nominal diplomatic capacity. After several futile petitions, Ennin decided to be bold and creative. He approached three Sillan interpreters separately in early 839 for means to prolong his stay. Eventually, he traveled widely and visited monasteries for over a decade. His diary documents events and peoples he encountered. It is regarded as perceptive and elaborate (Niu 1993). Most importantly, his identity as a monk enhances its credibility and objectivity. This account is thus held with historic esteem, on a par with Xuanzang’s travelogue and Marco Polo’s account of the East, as one of the three crucial archives on the Orient. Yet, Ennin’s travelogue was written in diary format during his pilgrimage. This sense of immediacy explains why it vividly captures greater details about peoples he encountered, including their actions, letters, utterances, and demeanor. It is a travelogue he meant to write for himself as a record, not an account commissioned by authorities. This independence indisputably makes it more valuable for humanities research.

The original journal, with 595 entries of various lengths, is not extant; what we have are copies from Japan of the oldest hand-copy found in a Kyoto monastery, called Toji, in the late 19th century. The diary was first published in China in 1936 and has since been translated into Japanese, Korean, French, and German. Its English version was translated in 1955 by Edwin Reischauer, an esteemed scholar in Japanese and Chinese studies and a US ambassador in Japan. In the same year, Reischauer also published an ethnographic account on 9th-century East Asian cultural exchanges based on Ennin’s diary (Reischauer 1955b). Through Ennin, we can see Sillan interpreters from diverse angles over almost a decade. In this light, the monk’s diary is certainly a treasure for interpreting historians of East Asia.

4. Civilian interpreters and an interpreting clerk

This article has no intention to analyze all four Sillan interpreters mentioned in Ennin’s diary. Notwithstanding their diverse backgrounds, I shall merely summarize the three civilian interpreters who only briefly appeared from 838 to 839. The bulk of this article will focus on an interpreting clerk, Yu Sinǒn, most often documented over the years. The interpreter historian Baigorri (2006: 102) legitimately argues that examining the profiles and situations of a group of interpreters counts far more than the mere “gleanings of information” of an individual interpreter. Yet, after a generic study of Sillan interpreters as a community (Lung, forthcoming), I noticed that this interpreting clerk, as an object of research, has a lot to offer. His interpreting position was a regular establishment in the enclave office.[9] It can be reasonably assumed that other prefectural Sillan enclaves might have been equipped with interpreting clerks as well. Therefore, Yu Sinǒn was not entirely an isolated or individual case. He might have been one of many interpreting clerks for the regional authorities at the time.

The case of Yu Sinǒn most intrigues me not just because of the longitudinal and qualitative evidence from the diary, but also Yu’s official status, through which he succeeded where the civilian interpreters failed in securing Ennin’s stay in China. This perhaps explains why these civilian interpreters were mentioned until mid-839 in the diary, whereas Yu Sinǒn, who first appeared in March 839, remained in touch with the monk until 847. Hence, the study of this interpreter offers a fascinating, vivid, and unusually detailed depiction of interpreters in 9th-century East Asian exchanges, involving Chinese, Korean, and Japanese interlocutors. No existing text to date, I believe, contains as much information pertaining to first-millennium interpreters.

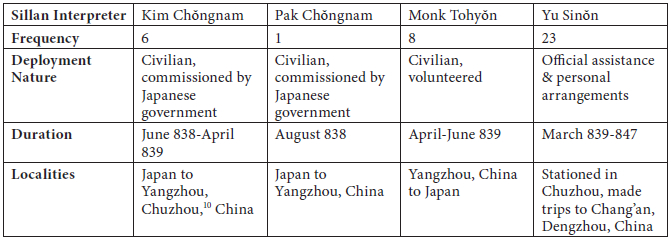

Table 1 gives a tally of the Sillan interpreters’ occurrences and the nature of their deployment. Each count is an independent event or action, but it deliberately does not align simply to a numerical count of the mentioning of Sillan interpreters. In my analysis, a count may involve one or more references to interpreters in a specific text. Each counted item includes concrete information about interpreters’ actions and words.

Table 1

Sillan interpreters in Ennin’s travelogue and the nature of their employment

I discuss elsewhere the first three interpreters which will not be duplicated here (Lung, forthcoming). This article will focus entirely on Yu Sinǒn. With substantial textual references in the diary, it is possible to meticulously represent what a Sillan interpreting clerk was like in the wider context of pre-modern East Asian exchanges.

5. Interpreting clerk’s roles in Ennin’s pilgrimage

Yu Sinǒn, affiliated to the Sillan enclave in the Chu prefecture (Chuzhou楚州, thereafter), was responsible for assisting the official guests visiting from Silla and Japan. His scope of duties was sufficiently broad to allow him to define what were considered relevant and nominal duties. As we shall see, much leeway was thus given to him to make a sideline profit. Most notably, many of his tasks, which include trading brokerage, messaging, and liaising with and for Ennin, came close to infringing (or actually broke) the law at the time. This was of course ironic, given his position as a law-abiding official cum gatekeeper. Yet it seems that it was precisely his official identity that conveniently enabled him to get around the law and ultimately served Ennin’s better interests. Regarding the insider role of interpreters, Michael Cronin aptly states that

[t]he interpreters are often recruited as ‘guides’ so that the act of travelling is explicitly bound up with the act of translation […]. Interpreters are valuable not only because of what they do but because of who they are. They are generally part of the host community and as such are conduits for privileged ‘inside’ information on the society and culture.

2000: 72

Being an interpreting clerk, Yu Sinǒn legitimately came in frequent contact with foreign guests. This position naturally drew them to approach him for problems they encountered during their stay. In a way, his official title might have marginalized the civilian interpreters from whom Ennin, for instance, used to solicit help. The fact is, soon after Ennin started contacting Yu Sinǒn, the other interpreters rapidly disappeared from Ennin’s record. This suggests he occupied a lion’s share of the interpreting business, which could otherwise have been handled by civilian interpreters. In the next section, I provide four categories of evidence to show how the interpreting clerk leveraged his official position and flouted the Chinese law in order to serve Ennin’s interests.

5.1. Trading brokerage for Ennin

According to the Tang China (618-907) code of law, tributary embassies could only conduct trade through official channels under close supervision.[11] This measure was meant to better monitor and stabilize commodity prices, which most affect people’s livelihood. The rule was strictly implemented to the extent that foreigners could not shop or trade in town. Ennin’s diary entries from 20th through 22nd February 839, as quoted below, recorded the recurrent arrests of the Japanese simply for shopping in town.

[Feb.] 20th Day: […] because they had not been able to buy or sell at the capital, the men mentioned above had been sent here to buy various things […]. Wang Yu-chen, the Manager and Military Officer, would not allow Nagakura and the others to sell […] would strike the drums.

Reischauer 1955a: 84[12]

Over these three days, six counts of Japanese trading violations and associated detentions were noted (Ennin 2007: 30-31; Reischauer 1955a: 84-85). Ennin’s apprehension of the detention risk must have convinced him to resort instead to the interpreting clerk’s sideline brokerage service. Exactly a month after the reported arrests, he implicitly engaged Yu Sinǒn concerning the purchase of some goods using his gold dust.[13] His diary entries from two consecutive days mysteriously bear the description of his sending two taels of gold dust and an Osaka sash to Yu Sinǒn and receiving from the interpreter some powdered tea and pine nuts in return.

(March) 22nd: Early in the morning I sent two large ounces of gold dust and an Osaka girdle (sic. sash) to the Korean Interpreter, Yu Sinǒn.

Reischauer 1955a: 94[14]

This is the first time Yu Sinǒn appeared in Ennin’s account. Oddly enough, no contextual clue justifies such expensive gifts to a newly-acquainted interpreter. Could the gifts be a bribe for a service from the interpreting clerk? The mystery, however, is better understood in the next entry when he gave Ennin “ten pounds of powdered tea and some pine nuts,” again unusually generous gifts for a new acquaintance, however religious the interpreter might have been.

(March) 23rd: At 2pm Yu Sinǒn came and gave me ten pounds of powdered tea and some pine nuts.

Reischauer 1955a: 95[15]

Being a Chinese resident and a government officer, Yu Sinǒn was, of course, free to trade in town. Yet, it might be dodgy, if not controversial, for him to accept gold dust from Ennin, which could easily be interpreted as a bribe for an illegal dealing. What was the nature of their exchange of gifts? At a time when barter trade was popular in Tang China, the exchange was in effect a business or trading brokerage deal. In the first scroll, Ennin mentioned presenting powdered tea and pine nuts, products he often used, to newly-acquainted monks and officials. The two entries above could then be understood as subtle references to a market purchase in disguise through the interpreter. Not confined by the restrictions, Yu Sinǒn probably acted as Ennin’s agent in the transaction, for a commission not explicitly stated. In any case, even with no explicit instructions, he seemed to have a tacit understanding why Ennin approached him in this context. He was fully aware of the legal loopholes, through which he efficiently helped Ennin and possibly made a profit. A Chinese interpreter might not have been so bold as to risk breaking the law. Yet, a Chinese interpreter might not have the access to Sillan social networks to conduct such secret transactions within the enclave either.

5.2. Scheming for Ennin’s illegal sojourn

According to the Tang code of law, tributary embassies could only travel in China with permits specifying the routes. Members of the embassies were expected to leave soon after tribute was paid to the emperor. This protocol was problematic for Ennin. Traveling to China with the embassy boats was more of a convenience for him. He was not really an embassy member. Nevertheless, this could be hard to argue with the officials holding the Japanese checklist of representatives on which Ennin was listed. With the will to undertake a pilgrimage in China, Ennin submitted formal applications to pursue his religious goals, but was denied time and again, even with the active lobbying of the Japanese ambassador and Li Deyu, the then chief minister in China. Yet, he never stopped exploring alternate options, known only to the natives. In February and April 839, Ennin separately approached civilian interpreters, Kim Chǒngnam and Monk Tohyǒn, for secretive means to stay. They asked around their Sillan networks and gave Ennin hope, but their plans did not materialize. After Tohyǒn was last mentioned in late June 839, Ennin continued to seek official permission for two years while staying in some Sillan monasteries.

Ennin must have contacted Yu Sinǒn for the same cause, although it was not overtly stated. The third time Yu Sinǒn was mentioned in 842 (Ennin 2007: 127), he was already actively engaged in accommodating Ennin’s disciples and properties, and updating Ennin, in writing, of the embassy boats’ return.

[…] Master Gensai was at present at Yu Sinǒn’s place with letters and twenty-four small ounces of gold dust. Egaku Kasho […] was intending to return home this spring, and [Yu] Sinǒn had arranged for someone’s ship [to carry him] [……]. [Yu Sinǒn] received a letter during the winter [from him], saying that he intended to avail himself of the ship of Li Lin-te Ssu-lang to return to his homeland from Ming-chou, but that, since his valuables and clothing as well as his disciples were all at Ch’u-chou [……] and someone’s ship had already been arranged for, he was still depending on [Yu Sinǒn to arrange] for their being sent from there [to Japan] [……]. These things are now at the home of Yu Sinǒn.

Reischauer 1955a: 317-318[16]

Yu Sinǒn thus carried out the civilian interpreters’ undelivered promises, facilitating Ennin’s illegal residence and keeping custody of his belongings. In fact, as seen from the above example, he displayed careful coordination of logistics arrangements and Sillan network resources he could command. It is unclear if he helped Ennin out of his Buddhist zeal or did it for monetary rewards. As discussed, Ennin did give him some gold dust at their first encounter. One may legitimately ask if it was an intrinsically fair transaction, given that gold dust is far more valuable than nuts and tea powder.[17] Is it possible that the transaction, well in the interpreter’s favor, was meant to bribe, if not cover expenses, to materialize Ennin’s illegal residence? If so, there is reason to believe that the exchange of gifts was deliberately made ambiguous, considering that illegal dealings, including trading for a foreigner and scheming for his extended stay, could have earned him a stay in jail.

Unlike the civilian interpreters, the interpreting clerk actually followed through to ensure that Ennin’s illegal sojourn was logistically secured. In 845, while finally seeing Ennin off towards the Deng prefecture (Dengzhou 登州, thereafter), the interpreter gave him letters of introduction so that his Sillan friends in Lianshui county could take care of the monk. Unfortunately, those friends did not turn out to be kind to Ennin.

(9 July 845:) Because the Ch’u-chou Interpreter had a letter for his Lien-shui compatriots bidding them to care for us and to see about keeping us when we reached the subprefecture, we first went to the Korean ward, but when we met the people of the ward they were not courteous to us.

Reischauer 1955a: 377[18]

At this late stage in 845, Yu Sinǒn’s independent arrangement exemplified his active coordination for Ennin, although his friends from the other end were not equally warm. At any rate, the interpreter’s social network with Sillans from other enclaves must have strengthened his ability to support Ennin during his sojourn, thanks to his official status, which easily commanded respect from fellow Sillans in the region.

5.3. Logistics support for monks during Buddhist persecution

Ennin’s years of relying on the interpreting clerk’s guidance, advice, and arrangements of various sorts must have convinced him of Yu Sinǒn’s credibility. Undeniably, the interpreter’s official background did make him more trustworthy. Realistically, in times of emergency, Ennin could at least contact him at his enclave office. In contrast, the civilian interpreters, often running errands on a need basis, might not be as accessible. Although Ennin was comfortable with the clerk’s continuous logistics assistance, it does not necessarily mean that Yu Sinǒn was obliged to help him, not after he left the embassy in late 839 anyway. After all, the clerk’s scope of duties was nominally confined to assisting the official guests in his enclave region, not beyond. Yet, as we shall see in further examples, he went the extra mile to fend for the monk’s well-being. His assistance for Ennin and other disciples was outside his mandated duties and might easily cause him troubles, given his official identity. Helping Ennin became more damaging to him during the Buddhist persecution throughout China from 842-846.[19] The grim political climate did cause him to be discreet, but he did not stop helping Ennin until the monk’s hastened departure for Japan in 847. In 846, he wrote Ennin a letter, saying:

There has been an Imperial edict to burn the Buddhist scriptures, banners, and baldachins, and the clothing, bronze vases, bowls, and the like of the monks, destroying them completely. Those who disobey are to be punished to the limit of the law. I burned all the scriptures, banners, pious [pictures], and the like of my household and kept only your writings and the rest. Since the regulating has been extremely severe, I feared that at guarded barriers they would discover them, so I did not dare take them out and send them to you.

Reischauer 1955a: 390[20]

One could not but wonder why the interpreter would casually take this risk in a time of mounting political tension against Buddhists? Initially, it might well have been simply a business connection, as suggested by Ennin’s plain factual entries when Yu Sinǒn was first introduced in March 839 (see section 5.1.). Over the years, presumably, their bonding was consolidated. For instance, Ennin noted the interpreter’s distress at failing to secure the monk’s departure for Japan from Chuzhou in 845. Besides, the clerk gave Ennin nine bolts of silk, socks, and knives as parting gifts (Ennin 2007: 150). This example of the interpreter’s emotion will be further discussed in the next section.

The interpreter’s integrity was crucial for Ennin. During his sojourn, valuables, such as gold dust, scriptures, banners, clothing, pious pictures, and letters, were entrusted with the interpreting clerk. Since Ennin’s pilgrimage was officially sponsored, gold dust was occasionally forwarded to him from Japan, in relay, through traveling monks or Sillan traders (Wu 2004; Li and Chen 2008). Sillan interpreters were sometimes entrusted to arrange for the transfer of these valuables. This relay procedure is frequently described. In May of 842, Ennin’s disciple at Chuzhou wrote and informed him of the embassy’s final return to Japan in 840, with some property and human losses, unfortunately, in the rough sea journey. Besides, he received a letter from Yu Sinǒn reporting that his disciple, with twenty-four small ounces of gold dust, was staying at his home. Five months later, the chain of events relating to these valuables was recapped as follows:

(13 Oct 842:) The twenty-four small ounces of gold which had been entrusted to T’ao Chung had already been used by Yu Sinǒn, the Interpreter of Ch’u-chou […]. I received a note from the Interpreter saying that he had already used [the gold] in accordance with Master Ensai’s instructions. The letters, boxes, and envelopes had already been broken open.

Reischauer 1955a: 321[21]

In the context of Buddhist persecution, Ennin summarized, on 9 October 842, the related imperial edict after the above entry dated 13 October 842. I was initially puzzled by the apparent misplaced “entry” of 9 October 842 (Reischauer 1955a: 321), an entry that should have chronologically been placed earlier. In fact, it is not really a regular entry, but a part of the entry of 13 October 842, inserted as a recollection or supplementary information. It reads:

On the 9th day [of the tenth moon] an imperial edict was issued [to the effect that] all the monks and nuns of the empire who understand alchemy, the art of incantations, and the black arts… should all be forced to return to lay life. If monks and nuns have money, grains, fields, or estates, these should be surrendered to the government.

Reischauer 1955a: 321-322[22]

The above example gives a picture of the intensity of the anti-Buddhist socio-political mood at the time. This contextual understanding is useful in making sense of the interpreter’s actions in assisting Ennin. Of course, it is possible that the interpreter might have used up or kept the gold dust in return for his logistics coordination. This included lodging for Ennin’s disciples and their belongings, catering, delivering messages or letters, writing Ennin to report updates, and arranging Japan-bound transport. We should not ignore the risk Yu Sinǒn took by defying the anti-Buddhist instructions. What he did, viewed from this context, was an act of treason. This business or personal tie with the monks was certainly not wise. In this sense, the interpreter should indeed be generously rewarded, given his sensitive official background. Alternatively though, his controversial decision to spend all the gold dust, meant to be taken to Ennin, might have been a contingent response to the imperial edict stipulating that monks’ properties and money be confiscated. Using up Ennin’s gold dust was Ensai’s idea, possibly sensing the critical reality. The interpreter’s fear of being implicated in worshipping Buddhism explained why he opened Ennin’s “letters, boxes, and envelopes” in his place. This move would ensure that no Buddhist items would be easily found in case of a house search. He could not be more careful. Once convicted, he would be severely penalized. It was only through his planning, courage, and bureaucratic network that Ennin and some of his scriptures could survive the storm.

5.4. Bribing government hirelings to prolong Ennin’s stay

With the interpreting clerk’s official identity, he must have developed rapport with fellow government hirelings. With this local authority network, he had once again secured deals to cater to Ennin’s well-being. In 845, dreading the Buddhist persecution and exhausted from years of pilgrimage, Ennin wanted to hop on a boat for Japan from Chuzhou, a route that would shorten his inland and seaborne travels. Yet the regional bureaucrats insisted, based on their peculiar procedures, that he should depart from Dengzhou further north. That would impose on Ennin a hike in the most unhospitable terrain in summer. The interpreter was disturbed by his failure to cater to Ennin’s most legitimate request. This example is a rare display of an interpreter’s emotion. It seems that their rapport was indeed more than a business tie. The interpreter’s enthusiasm to help Ennin was not entirely driven by material reward. In his seventh year of acquaintance with Ennin, he was enraged over Ennin’s interests being compromised.

(3 July 845:) The Commissioner Sǒl and the Interpreter Yu had wished to be able to keep us and settle us in the Korean ward and send us home from here, and they were made unhappy over their inability to keep us because of the subprefecture’s refusal.

Reischauer 1955a: 375[23]

Two days later, after several futile attempts to reverse the official decision, he came up with yet another plan to ease Ennin’s life before the arduous trip. Ennin’s diary records the interpreter’s persuasive rhetoric addressing the government hirelings for his temporary stay in Chuzhou.

[5 July 845:] At dawn we went with some government hirelings to the home of the Interpreter Yu. The Interpreter gave three hundred cash to the government hirelings and conferred with them privately, saying, “The monks are going on a distant trip just at the hottest time of the year, and already they are in distress. I should like to be able to keep them in my home and have them rest for two or three days [….].” The government hirelings agreed to the suggestion and returned home. The Commissioner and the Interpreter did all they could to take care of us.

Reischauer 1955a: 375[24]

As we notice, the interpreter undertook more than sheer persuasion. Not proficient in spoken Chinese, Ennin could not talk to the Chinese officials. It was the interpreting clerk who acted as his agent to independently liaise with the hirelings. When the hirelings escorted Ennin, soon to be deported, to the interpreter’s house, Yu Sinǒn bribed them with three hundred cash and reasoned with them about the ordeal Ennin had been through. He succeeded in buying time for Ennin, but it is unclear if this was done with his money or the gold dust temporarily entrusted to him. Either way, an interpreter at work was dramatically portrayed here, with his rhetoric, oratory skills, action, and scheme presented in this account. Most ironically, it was an official bribing other officials to obtain merciful allowance to defer deporting Ennin. Such fine details about how an interpreting clerk astutely served his patron are rarely captured in standard archives. With Ennin’s meticulous and first-hand description, however, we are privileged to witness the interpreting clerk’s actual work at the time.

6. Implications and conclusions

6.1. Private archives

This study highlights the value of private archives over official archives for empirical research on historical interpreting and interpreters. Ennin’s diary, most notably, contains informative accounts of interpreters he encountered. His personal record exposes us to the concrete contexts in which Sillan interpreters liaised and ran errands for him over a decade. This came as a stark contrast to the typical official records in which interpreting or interpreters are often anonymously mentioned in passing. Ennin’s diary, with its intensity, depth, and lively descriptions, is thus a rare gem about interpreters and interpreting in histories. Credible personal memoirs or travelogues are indeed valuable data sources, precisely because they were not commissioned by authorities. With a personal touch in their first-person experience, they describe interpreters and interpreting events as they were. Given the people-oriented genre in the writing of memoirs and travelogues, these private archives could better reveal how language or cultural brokers operated and functioned in cross-linguistic contexts.

6.2. Prominence and incongruence of Sillan interpreters

East Asian exchanges in late first-millennium China, viewed through the lens of Ennin, throw an interesting light on interpreters. Prominent as they were, Sillan interpreters become more intriguing as we examine their roles and identities in dozens of textual examples. Fundamentally, they did not work in static venues as conventional interpreters do. Instead, they dynamically liaised with local authorities or regional civilians for foreigners, or ran around to coordinate the logistics for their patrons. This variation of interpreters’ duties makes their profiling even more significant. Yet this is just a broad picture of Sillan interpreters, which serves as but a background to this study.

This article focused on an interpreting clerk’s work for Ennin, which was not simply language mediation. Instead, his tasks ranged from liaising, trading, logistics arrangement, and message go-between. However, the multiplicity of interpreters’ work, as we notice, was not confined to the interpreting clerk alone. In the evidence presented, polyglots given the title of interpreter – as Kim Chǒngnam and Yu Sinǒn were – did not simply engage in straightforward interpreter-mediated exchanges. This inconsistency is similar to Mairs’s study in which myriad interpreters’ roles were identified in the Roman empire (27 BC-393 AD). Mairs (2011) observes that the Latin (interpres) and Greek (hermêneus) terms for interpreters in the Roman empire may be understood as multi-faceted commercial go-betweens, negotiators, mediators, or simply someone who explains. Although these two foreign terms are regularly, and narrowly, anglicized as interpreters, their scope of reference went beyond sheer linguistic mediation. In some cases, the so-called interpreters or negotiators were purely trading brokers in the Roman military services (Mairs 2012). Is this incongruence between interpreters’ functional title and interpreters’ work necessarily more pronounced in remote historical periods? Why? Perhaps modern theoretical descriptions of interpreting and interpreters need to consider also the non-linguistic roles or duties of intermediaries from earlier historical contexts.

6.3. Interpreting clerk versus civilian interpreters

In this article, I examined how the interpreting clerk’s official position enabled him to effectively promote Ennin’s interests. This quasi institutional support was essential for Ennin in the context of Buddhist persecution in mid 9th-century China. Yu Sinǒn was superior to civilian interpreters exactly because of his ability to manipulate legal loopholes and his premium access to official connections. Ennin’s predicament as an illegally resident monk heightened his acute need for a government interpreter who could offer him sound advice and practical protection. His choice of Yu Sinǒn was certainly not randomly made. Remember, before approaching the interpreting clerk, Ennin sought help from two civilian interpreters separately but to no avail. This perhaps explains why the first appearance of Yu Sinǒn in March 839 coincided with the absence of civilian interpreters in the diary from late June 839.

Admittedly, Yu Sinǒn was the only interpreter in our data with an official background.[25] Yet, this data limitation can be balanced by the depth of Ennin’s multifaceted descriptions of this clerk over nine years. Through dozens of textual examples, I noticed the arbitrary distinctions between an interpreting clerk and civilian interpreters in those days. Crucially, Yu Sinǒn’s various tasks undertaken for Ennin were no different from those often shouldered by other entrepreneurial interpreters. Undeniably, these assignments often went beyond what was expected of his official capacity. Yet we should remember, our reading of the diary was directed by Ennin’s necessarily monolithic perspective. It is possible that most of Yu Sinǒn’s work in the enclave was in line with the protocol of the regional government, but understandably his other work escaped Ennin’s attention. As a step to examine Sillan interpreters further, the more important question is why? Why did Yu Sinǒn continue to run errands for Ennin over nine years? Was it solely due to material rewards? Alternatively, his helping Ennin might have been partly out of his sympathy for Buddhism, which happened to be the state religion of Silla.[26]

In Ennin’s diary, there were two references to valuable gifts entrusted to Yu Sinǒn: first, two taels of gold dust, probably to purchase tea and nuts; second, twenty-four taels of gold dust, to be forwarded to Ennin, in principle. Being a courier of valuables for foreign visitors was certainly not the clerk’s listed duty. Yet, Yu Sinǒn seemed quite comfortable, and in fact familiar (no questions asked), with the course of events. Interestingly, the use of the gold dust was conveniently not specified, possibly for fear that someone should be implicated for flouting the law against foreigners undertaking transactions in China. In short, it is possible that the interpreter might have been rewarded for helping Ennin in ways he was not supposed to. Their tacit understanding might have induced him to privately undertake liaison, trading, courier, and logistics tasks otherwise commonly contracted to civilian interpreters. As noted from Ennin’s narrative, this interpreting clerk nevertheless succeeded better in advancing Ennin’s interests and accomplishing tasks asked of him. Being affiliated to the regional Sillan enclave, he was sufficiently resourceful and was seen to be in touch with his Sillan social network in China, Japan, and Silla. Such networking support inarguably strengthened his decade-long assistance to Ennin. Ironically, though, it was precisely his official position that enabled him to be in frequent contact with foreigners, and to flout both the law forbidding foreigners to trade in China and the law persecuting Buddhism.

6.4. Interpreter’s voice in work correspondence

Interpreters’ visibility has been a key concern in modern interpreting studies. Ennin’s diary not only makes frequent and intricate references to interpreters, it also archives the interpreting clerk’s voice by including his direct speech (see section 5.4.) and his work correspondence (see section 5.3.). In order to update Ennin with news from Japan, the interpreter gathered intelligence from Sillan traders commuting in East Asia. These news items were sometimes included in his letters to Ennin. The interpreter’s words and writings were in turn documented, possibly verbatim, in the diary. In an example quoted in section 5.2., 書云 literally means “the letter says.” So, the words following 書云 are, in principle, all extracted from the interpreter’s letter. In this example, the use of 敝所 (literally, a humble and polite reference to “my house”) strongly suggests that this was probably the verbatim text from Yu Sinǒn’s letter addressed to Ennin.[27]

It is pertinent to the history of interpreting that what we have here is the interpreter’s working correspondence to his patron, not simply words in a memoir. This letter and others are effectively hard evidence of the interpreter in action and at work. These writings of a 9th-century interpreter are significant. The same interpreter reappeared in 847 after being promoted to General Manager of the Sillan enclave, an administrative position, not an interpreting position. From this point onward, he was referred to by his superior new title, not as an interpreter (Reischauer 1955a: 392). His promotion from a regional interpreting clerk to a senior administrator enlightens us of the possible career path for East Asian polyglots at the time. Both the interpreter’s correspondence and his promotion are worthwhile research topics since they cast light on first-millennium interpreters in East Asia. They present unique data on this remote time and place for which only limited research on inter-lingual communication has been conducted. These lines of inquiry promise to be fruitful avenues of historical interpreting research.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

Research for this paper was supported by a General Research Fund (LU 341512) from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong.

Biographical note

Rachel Lung is Professor in the Department of Translation of Lingnan University, Hong Kong. For the past decade, her research interests have been in the historical study of translation and interpreting in imperial China. She is particularly interested in identifying and analyzing archival evidence pertaining to interpreters and interpreting, which is a valuable means to unveil what inter-lingual mediation and being an interpreter were like one or two millennia ago. Using this empirical approach, she has published over a dozen journal articles on this topic since 2005, including “Interpreters and the Writing of Histories in China” in Meta (2009), together with a research monograph, Interpreters in Early Imperial China, published by John Benjamins in 2011. Her more recent research goes beyond imperial China to examine the roles of Sillan (ancient Korean) interpreters in East Asian civilian and commercial exchanges in the second half of the first millennium. Her forthcoming publications include: “Defining Sillan interpreters in first-millennium East Asian exchanges,” in New Insight on the History of Interpreting: Evolving Identities, Adapting Practices, Benjamins Translation Library Series, (Eds.) Kayoko Takeda and Jesús Baigorri (2015), and “The Jiangnan Arsenal: A microcosm of translation and ideological transformation in 19th-century China,” in TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Redaction (2016).

Notes

-

[1]

Written classical Chinese was a diplomatic lingua franca in first-millennium East Asia. The East Asian states, not having developed their written languages, considered Imperial China the centre of civilized learning. For instance, Silla and Japan relied on Chinese translated scriptures to understand Buddhism. For East Asian monks, therefore, competence in written Chinese is a channel through which they mastered the scriptures. One common way to practice their Chinese learning was to copy these scriptures.

-

[2]

According to Lee and Ramsey (2011: 4), the Sillan vernacular, known also as Old Korean, “effected a linguistic unification of Korea,” since it became the peninsular lingua franca after the unification; “[i]t gave rise also to Middle Korean, which is the direct ancestor of Korean spoken today.” Ennin recalled that the Sillan vernacular was used in Buddhist lectures and chanting in the Sillan monasteries he visited in Shandong, suggesting the strength of local Sillan communities in eastern coastal China (Ennin 2007: 61-62. Reischauer 1955a: 153-155).

-

[3]

As Ennin recapped on 22nd September 845 in his diary, I Sinhye李信惠, a Sillan monk, lived in Japan for eight years (815-823). This monk returned to China in 824 and became a Sillan interpreter, capitalizing on his spoken Japanese competence (Ennin 2007: 154; Reischauer 1955a: 387).

-

[4]

Korean sources about Sillan interpreters are flimsy, but traces of these interpreters can be found in or inferred from Japanese histories (Ma 2005; Yuzawa 2010). It is important to note, however, that Sillan interpreters in the Japanese sources might be ethnic Japanese, not necessarily Sillan as those mentioned in Ennin’s diary. This distinction is not often carefully identified in the literature.

- [5]

-

[6]

According to the Liangshu, in 520, Silla tagged along with Baekje’s China-bound embassy. Its Chinese letter for the emperor of Liang China (502-557) was prepared with active assistance of Baekje.

-

[7]

For centuries in the first millennium, Japan benefitted from Baekje’s Chinese scholars in its learning of Chinese language and culture.

-

[8]

The Samguk Yusa (Legends and History of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea) records that earthquakes and famines were widespread in Gyeongju, Silla’s capital, from 78. through 790, and again in 796 and 797 (Zhao 2003).

-

[9]

Interpreting clerks as a community were most notable in the colonial African context. Nelson Mandela wrote, “I had my heart set on being an interpreter or a clerk in the Native Affairs Department. At that time, a career as a civil servant was a glittering prize for an African” (Lawrance, Osborne et al. 2006: 3). Interpreters for colonial Africa, usually black males, were also called “white-blacks” because of their intermediary and civil servant roles.

-

[10]

Chuzhou was in the north of Nanjing at the intersection of the Grand Canal and the Huai River, which at that time flowed into the Yellow Sea.

-

[11]

Officials in the court of diplomatic receptions (Honglusi 鴻臚寺) in Tang China would assess and record the value of the tributary gifts in order that gifts from China of equivalent or approximately equal value would be “bestowed” in return to the embassy concerned. This is called tributary trade, a form of international trade in disguise.

-

[12]

(二月) 廿日[……]緣上都不得賣買,便差前件人等為買雜物來[……]不許永藏等賣[……]即打鼓發去。(Ennin 2007: 30)

-

[13]

Examining Ennin’s diary from historical Economics, Zhang and Zou (1998: 49) confirm that gold dust could be valuated through either official or private agents, but “usually at a discounted rate,” in Tang times. They claim that “three small taels of gold dust were equivalent to one big tael of gold dust” in 9th-century China (my translation).

-

[14]

(三月) 廿二日。早朝。沙金大二兩。大阪腰帶一。送與新羅譯語劉慎言。(Ennin 2007: 34)

-

[15]

(三月) 廿三日。未時。劉慎言細茶十斤。松脯贈來。與請益僧。(Ennin 2007: 34)

-

[16]

[…] 寄仁濟送書云。玄濟闍梨附書狀。並砂金廿四小兩。見在敝所。惠萼和尚 […]今春擬返故鄉。慎言已排比人船訖 […]冬中得書云。擬趁李鄰德四郎船。取明州歸國。依萼和尚錢物衣服並弟子悉在楚州 […] 從此發送 [……] 此物見在劉慎言宅。(Ennin 2007: 127)

[…] 寄仁濟送書云。玄濟闍梨附書狀。並砂金廿四小兩。見在敝所。惠萼和尚 […]今春擬返故鄉。慎言已排比人船訖 […]冬中得書云。擬趁李鄰德四郎船。取明州歸國。依萼和尚錢物衣服並弟子悉在楚州 […] 從此發送 [……] 此物見在劉慎言宅。(Ennin 2007: 127) -

[17]

Anthony Pym queried whether the trading of ordinary items, such as powdered tea and nuts, for gold dust was a fair deal (May, 2014, personal communication). Yet, if the gold dust was partly meant to be paid to the interpreting clerk as a formality fee, commission or bribe, the deal could perhaps make better sense.

-

[18]

緣楚州譯語有書付送漣水鄉人。所囑令安存。兼計會之事。仍到縣。先入新羅坊。坊人相見。心不殷懃。(Ennin 2007: 150)

-

[19]

During the later reign period of emperor Wuzong (814-846), who was more sympathetic to Taoists, a range of anti-Buddhist measures were in place to increase revenue and vent his prejudice against Buddhism. These measures included forcing the “unproductive” monks and nuns back to lay life and confiscating Buddhist properties.

-

[20]

有敕焚燒佛教經論幡蓋及僧衣物銅瓶碗等。梵燒淨盡。有違者便處極法。自家經幡功德等皆焚燒訖,唯留和上文書等。條流甚切,恐鎮柵察知,不敢將出寄付。(Ennin 2007: 155)

-

[21]

其付陶中金廿四小兩。楚州譯語劉慎言先已月盡[……]得譯語報云。據圓載闍梨命。先已用矣。書函封先已折開。(Ennin 2007: 128)

-

[22]

[十月]九日,敕下:天下所有僧尼解燒煉咒術禁氣、背軍身上杖痕烏文、雜工巧,曾犯淫養妻不修戒行者,並勒還俗。若僧尼有錢物及谷斗田地庄園,收納官。(Ennin 2007: 128)

-

[23]

薛大使。劉譯語意欲得勾留在新羅坊裡置。從此發送歸國。緣州縣不肯。遂苦勾留不得也。(Ennin 2007: 149)

-

[24]

曉際。共家丁到劉譯語宅。譯語以三百文與家丁。私計會云。和尚等正熱之時。遠涉道路。見已困乏。慎言欲得安置宅裡。令兩三日歇息。[……]家丁受囑歸家。大使。譯語竭力將養。(Ennin 2007: 149)

-

[25]

In the limited research in China on Sillan interpreters, their identities were often dealt with indiscriminately and impressionistically (Li and Chen 2008; 2009; Chen 2009a; 2009b). Li and Chen (2009), for instance, apparently mistook a Sillan official, 張詠 Chang Yŏng, in Ennin’s account as an interpreter. This assumption was made entirely based on Ennin’s reference to this official as 新羅通事押衙張詠 (Ennin 2007: 52). The term tongshi 通事 might have been casually understood as an interpreter, although Ennin carefully distinguished his usage of 譯語 (interpreter) and 通事 (officer) throughout his travelogue. Reischauer translated 通事 incorrectly as “interpreter” several times (1955a: 14, 131). The problem is that the same Chinese term could have rather different meanings when used in different historical periods. Although it is true that tongshi denotes interpreters from Song (960-1279) through Qing (1664-1911) dynastic China, the term does not bear this connotation until the final years of Tang China at the earliest (Yao 1981). As Judy Wakabayashi observes in her review of various conceptualizations of translation historiography, “multiple interpretations of a particular terminological concept can coexist in a given period, and the meaning often changes over time” (2012: 182).

-

[26]

Ennin’s descriptions suggest that the rituals and ceremonies held in Sillan monasteries in coastal Chinese counties easily gathered 250 Sillan civilians.

-

[27]

Reischauer’s translation (1955a: 317-318) turned Ennin’s direct quotation into reported speech. Readers relying exclusively on his translation will simply miss out on this subtlety.

Bibliography

- Baigorri, Jesús (2006): Perspectives on the history of interpretation: Research proposals. In: Georges Bastin and Paul Bandia, eds. Charting the Future of Translation History. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 101-110.

- Bassnett, Susan and Harish, Trivedi (1999): Introduction: Of colonies, cannibals and vernaculars. In: Susan Bassnett and Harish Trivedi, eds. Post-colonial Translation: Theory and Practice. London and New York: Routledge, 1-18.

- Bowen, Margareta, Bowen, David, Kaufmann, Francine, et al. (1995): Interpreters and the making of history. In: Jean Delisle and Judith Woodsworth, eds. Translators Through History. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 245-273.

- Chen, Jianhong 陳建紅 (2009a): 試論新羅譯語及其歷史作用 [Silla interpreters and their historical roles]. Master thesis, unpublished. Yanbian: Yanbian University.

- Chen, Jianhong 陳建紅 (2009b): 試論新羅譯語 在東亞通交中的作用 [Functions of Silla translators in the exchanges between East Asian countries]. 黑龍江史志 [History of Heilongjiang]. 6:23-27.

- Chen, Shangsheng陳尚勝 (1996): 唐代的新羅僑民社區 [The community of the Silla expatriates in the Tang dynasty]. 歷史研究 [Historical studies]. 1:161-166.

- Chen, Shangsheng陳尚勝 (2011): A study of Silla immigrant enclaves in the Tang empire. (Translated by Clarissa Fletcher) Chinese studies in history. 44(4):6-19.

- Cronin, Michael (2000): Across the Lines: Travel, Language, Translation. Cork: Cork University Press.

- Ennin 圓仁 (2007): 入唐求法巡禮行記 [Ennin’s diary: The record of a pilgrimage to China in search of the law]. Guilin: Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe.

- Jin, Cheng’ai. 金成愛 (2012): 九世紀における 在唐新羅人 社会の相互連携: 円仁『入唐求法巡礼行記』の記事 を手掛かり として [Sillan residents of T’ang China in the 9th century: Reflections on mutual communication through Ennin’s Travels in T’ang Chna]. Journal of history, culture and society. 9:11-22.

- Kyung, Moon Hwang (2010): A history of Korea. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lawrance, Benjamin, Osborne, Emily and Roberts, Richard (2006): Introduction: African intermediaries and the “Bargain” of collaboration. In: Benjamin Lawrance, Emily Osborne and Richard Roberts, eds. Intermediaries, Interpreters, and Clerks: African Employees in the Making of Colonial Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 3-34.

- Lee, Ki-Moon. and Ramsey, Robert. (2011): A history of the Korean language. Cambridge: CUP.

- Li, Zongxun 李宗勛 and Chen, Jianhong 陳建紅 (2008): 圓仁的《入唐求法巡禮行記》與九世紀東亞海上通交 [Ennin’s travels in China and maritime exchange in 9th-century East Asia]. 東疆學刊[Journal of Dongjiang]. 4:53-61.

- Li, Zongxun 李宗勛 and Chen, Jianhong 陳建紅 (2009): 試論新羅譯語的來源及其特點 [The origin and features of Silla translators]. 延邊大學學報[Journal of Yanbian University]. 1:69-73.

- Liangshu 梁書 [A history of the Liang dynasty] (1973): Compiled by Cha Yao and Silian Yao. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

- Lung, Rachel (forthcoming): Defining Sillan interpreters in first-millennium East Asian exchanges. In: Kayoko Takeda and Jesús Baigorri, eds. New Insight on the History of Interpreting: Evolving Identities, Adapting Practices. Benjamins Translation Library Series. Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Co.

- Ma, Yihong 馬一虹 (2005): 古代東亞漢文化圈各國交往中使用的語言與相關問題 [Language use among states in the Chinese cultural sphere in ancient East Asia]. In: Yuanhua Shi 石源華, ed. 東亞漢文化圈與中國關係 [The relation between the Chinese cultural sphere in East Asia and China] (2004 proceedings of the International conference on the history of Sino-foreign relation). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 99-119.

- Mairs, Rachel (2011): Translator, traditor: The interpreter as traitor in classical tradition. Greece and Rome. 58(1):64-81.

- Mairs, Rachel (2012): ‘Interpreting’ at Vindolanda: Commercial and linguistic mediation in the Roman army. Britannia. 43:17-28.

- Niranjana, Tejaswini (1992): Siting Translation: History, Post-structuralism and the Colonial Context. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Niu, Zhigong 牛致功 (1993): 論《入唐求法巡禮行記》的史料價值 [The historical value of Ennin’s diary: The record of a pilgrimage to China in search of the law]. 人文雜誌 [Renwen zazhi]. 2:89-95.

- Ostler, Nicholas (2005): Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Reischauer, Edwin (1955a): Ennin’s Diary: The Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Law. By Ennin. (Translated by Edwin Reischauer). New York: Ronald Press Company.

- Reischauer, Edwin (1955b): Ennin’s Travels in T‘ang China. New York: Ronald Press Company.

- Roland, Ruth (1982/1999): Interpreters as Diplomats: A Diplomatic History of the Role of Interpreters in World Politics. Revised edition. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

- Samguk Yusa 三國遺事 (Tr.) (2006): Legends and History of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea. (Translated by Tae-Hung Ha and Grafton Mintz) USA: Silk Pagoda.

- Wakabayashi, Judy (2012): Japanese translation historiography: Origins, strengths, weaknesses and lessons. Translation studies. 5(2):172-188.

- Wu, Ling 吴玲 (2004): 九世紀 唐日 貿易中的東亞商人群 [East Asian traders in Sino-Japanese commerce in the 9th-century]. 西北大學學報 (社會科學版) [Xibei daxue xuebao (shehui kexueban)]. 9:17-23.

- Yao, Congwu姚從吾 (1981): 遼金元時期通事考 [A study of tongshi during Liao, Jin, and Yuan China]. Taipei: Taipei Zhengzhong shuju.

- Yuzawa, Tadayuki 湯沢質幸 (2010): 古代日本人と外国語 東アジア異文化 交流の言語世界 [Ancient Japanese and foreign languages: East Asian intercultural exchanges in the linguistic world]. Tokyo: Bensey Publishing Company.

- Zhang, Renzhong 張仁忠 (2006): 中國古代史. [Ancient Chinese history]. Beijing: Peking University Press.

- Zhang, Jianguang 張劍光 and Zou, Guowei 鄒國慰 (1998): 《入唐求法巡礼行记》的經濟史料價值略述 [An outline of the value of Ennin’s Travels in China on economic history]. 上饒師專學報 [Journal of shangrao teachers college]. 18(4):43-50.

- Zhao, Hongmei 趙紅梅 (2003): 從在唐新羅人看在唐新羅關係 ― 以新羅人在唐聚居 區為中心 [A study of the relationship between Tang China and Silla: Focusing on Sillan enclaves in China]. Master thesis, unpublished. Yanbian: Yanbian University.

List of figures

Figure 1

Map of the Three Kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula around 600AD[5]

List of tables

Table 1

Sillan interpreters in Ennin’s travelogue and the nature of their employment