Abstracts

Abstract

Translation plays an important role in the transcultural conceptualization of the characteristics of names (form, function, meaning, naming practices in the world…), especially when it includes names that look unusual from the Eurocentric, Western point of view. This paper analyzes such a situation in relation to the Spanish translations of Native American proper names in the literature by these cultural groups: it explores the diversity of names in the source language and culture and compares it to the target texts in order to observe the choices and decisions made by translators. The analysis also includes a revision of the scholarly ideas about the translation norms concerning Indian names and finally leads to an interpretation of the broader context of the transcultural reception of the indigenous Other in Spain.

Keywords:

- literary translation,

- Native American literature,

- translation of names

Résumé

La traduction joue un rôle important dans la conceptualisation interculturelle des caractéristiques des noms (leur forme, leur fonction, leur signification, les pratiques pour donner des noms dans le monde…), particulièrement quand elle comprend des noms qui semblent peu communs du point de vue eurocentrique, occidental. Cet article analyse cette situation en ce qui concerne les traductions espagnoles des noms propres amérindiens dans la littérature écrite par ces groupes culturels. En effet, nous explorons la diversité des noms dans la langue et la culture source et nous la comparons avec les textes cibles pour observer les choix et les décisions des traducteurs. L’analyse comprend aussi une révision des idées académiques sur les normes de traduction concernant les noms amérindiens et enfin, elle conduit à une interprétation du contexte plus large de la réception interculturelle de l’Autre indigène en Espagne.

Mots-clés :

- traduction littéraire,

- littérature amérindienne,

- traduction de noms

Article body

1. Introduction

In the Euro-American thinking, there is a widespread and, in many circumstances, unconscious assumption that proper names indicate a unique entity, one that may be either absolute, such as President George Washington or writer Fatou Diome, or relative, as John or Mary. This supposition is directly linked with the cultural belief that proper names and personal identity share a relation “at once intimate and complete upon which all other relations of self-identity rest” (Ferguson 2009: 83). However, scholars such as Allerton (1987), Thomas (1997) and Trapero (1996) claim that anthroponyms only carry referential, not semantic meaning. This implies that proper names do not show “ninguna cualidad del ente que lleva ese nombre” [any quality of the being which carries that name][1], nor create “condiciones de pertenencia a la categoría” [the belonging conditions of the category] they are part of (Franco Aixelá 2000: 60). Such a situation usually causes the clash of these reflections with the culturally different realities of non-Western communities, where names are conceptualized in dissimilar ways.

In this context, translation processes play an important role. As Carbonell i Cortés (1997), Cronin (2006), Ryou (2005) or Vidal Claramonte (2007), among others, point out, identities are always negotiated in social and artistic contexts, and, when translation takes place, these identities are (re)constructed in a situation of inequality between the cultures involved in the process. Thus, the conditioned nature of identities in the translation process leads many times to decisions that “entail transforming the alien elements in accordance with the conventions of the target discourse” (Robyns 2004: 417). Even before contemporary Indian literatures written into English, object of this study, were published, Native American oral literatures had already undergone this kind of transcultural alterations: “Transformations of Native American oral literary performances into European-language texts have tended to reflect the translators’ preconceptions about ‘the Indian’ and about literature” (Clements 1991: 1).

Translation processes involve, potentially and actually, so important modifications of the identities of the Other and the Self, that even minor elements in everyday language are studied to determine how professionals use translation strategies when facing transcultural differences (Mojola 2004). Bandia (2008: 40), for example, argues that proper names are an essential aspect of African postcolonial societies, so the different translation possibilities concerning names show the complex cultural and identitarian signification of naming practices at both edges of the translation process. He points out that names, being one of the most culturally specific items, become “natural zones of resistance to colonialist assimilation” in the source text, but, at the same time, an important imperialist object of translations in the Western strategies of conquest (Bandia 2008: 40). In this way, even if it seems easy to couple an identity and a proper name, translators (un)consciously modify and/or respect identities according to the defining capacity of names themselves and to the corresponding conceptualization that their own society has at a given moment. Therefore, the formal, referential and semantic characteristics of names influence the establishment of more or less standardized regulations that determine what is translated and how (Franco Aixelá 2000: 56-64).

The regulations are not evenly shared by all professionals, and the alternative strategies that different translators use serve as an indication of the working ideologies within the target society and its transcultural reaction to the presence of the Other par excellence. The Euro-American conceptualization of names has distorted, among others, the traditional systems of naming within Native American communities, (re)producing recurrent stereotypes about the semantic dimension of Indian anthroponyms. The resulting assumption concerning the function and meaning of Native American names only contributes to the misleading idea of Indians having unusual, extravagant proper names that do actually define the holder. Such Eurocentric vision perpetuates the differentiation of individuals on the basis of a falsified description, causing a greater lack of transcultural understanding and the promotion of old-fashioned myths about Indian names and identities.

Native American naming practices are complex, and have varied widely through history and from tribe to tribe. As Hirschfelder and Beamer (1999: 35) point out, some Indian communities link name giving to different ages: traditionally, Tewa babies got their names at birth, while the Lenapes did not bear any name until they were three or four years old; among the Hopi, children used to receive their names between six and ten, when they were initiated into the religious practices. Charles A. Eastman reveals in his autobiography Indian Boyhood (1902)[2] that Dakotas in the nineteenth century changed their names several times throughout their lifetime. In his personal case, he was called Hakadah (pitiful last) at birth due to his mother’s death, becoming later known as Ohiyesa (winner); finally, he adopted his Euro-American name once his father converted to Christianity. In addition to these differences, the assimilationist doctrine of White society included the renaming of Indians and the adoption of the given name plus surname format, making possible contemporary names such as Ben Nighthorse Campbell, Cleo Big Eagle, S. Neyooxet Greymorning, or A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff.

This paper explores these particularities of Native American names when they are involved in a translation process from English into another European language, in this case, Spanish. It examines how Spanish translators have dealt with Indian proper names when rendering the written literature produced by the indigenous peoples of the United States.[3] In addition, the survey reflects on translation regulations and techniques, their (dis)advantages, and their significance in the broader context of the transcultural (re)creation of the Native American identities. In this way, the present study avoids the repetition of anthroponomical stereotypes and, at the same time, highlights the importance of knowing about the actual variability of names that Indians use in their daily life and in their own writings.

Last but not least, the present survey accentuates the diachronic importance of translation in the construction of identities, especially that of Native Americans. In Spain, more than sixty books authored by American Indians have been translated since 1975, when the Spanish version of Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (Deloria 1969)[4] was published. The steady release of new translations and old translations alike involves a constant reformation of the conceptualization that Spaniards have of Indianness, both in relation to the popular and academic projection of it. Thus, the study of the transference of personal names will show us how the Native American naming practices are received in Spain and how the different translation strategies affect the identity of the Other when he is exported to another culture.

2. Theoretical and practical background in Spain

With the exception of legal documents, translation in Spain is not regulated by law.[5] In fact, Translation Studies are defined by a descriptive methodology: researchers, in most cases, study the labor of fellow professionals, identifying logical patterns in the practice of translation and, at the same time, helping future translators with the many problems they may face during the translation process (Brownlie 2008). These research works vary in their scope and depth, but usually tend, as is expected in the profession, to offer a non-prescriptive insight of what has been done in previous decades and what translators are doing at the moment in order to interpret the development of the profession and the academic discipline and to evolve according to the new transcultural challenges (Dollerup and Appel 1996; Lee-Jahnke 2011; Nord 1988/1991; Rodríguez Rodríguez 2011).

Such a perspective about the scope of research causes interesting, sometimes endless, debates about the (im)possibility of creating rules and the actual dimension and power of norms (Schäffner 1999: 1-2), both as tendencies and as explanations (Chesterman 2006: 14 and 15). Placed in the middle space of a socio-culturally constrained scale whose extremes are rules, at one edge, and idiosyncrasies, at the opposite edge (Toury 1995: 54), norms, beyond theoretical definitions, “are rarely explicitly verbalized and tend to be followed by translators almost unawares” (Malmkjaer 2005: 14). In this way, norms, with their long-term alterability and their dependence on the surrounding context (Hermans 2013: 2, 5), express the expectations and conventions of a given society at a given moment in relation to certain cultural items once they are being incorporated into the target society through translation.

Names are one of these items with norms associated, something that has not gone unexplored inside Translation Studies. Spanish professionals, for instance, have at their disposal a series of research works concerning the translation of proper names in different contexts: Espinal (1994) debates about the linguistic constraints of names for their translation; Mateo Martínez-Bartolomé (1994) discusses the importance of names and their translation in comedy plays; Marcelo Wirnitzer and Pascua Febles (2005) analyze the role of creativity and imagination when translating names in Harry Potter; Cámara Aguilera (2009) attends to the multiple possibilities offered by children’s literature. All of them claim that there is a set of norms well disseminated and shared by translators, although these norms mainly work as preferences and suggestions that do not have to be followed by professionals themselves when the circumstances require a strategy different from the one advised by scholars and language institutions.

Even if “in the last decades it has been accepted as the general norm of translation practice that proper names are not translated” (Marcelo Wirnitzer and Pascua Febles 2005: 965), the exceptions abound. For instance, the theoretical and practical reflections of Spanish researchers accentuate the tradition of rendering in Spanish the names of members of royal families, including new members such as Kate Middleton (Fundéu BBVA 2011).[6] At the same time, they insist on the current inclination to restore some of the names formerly translated such as John Milton or Arthur Koestler (Moya 2000: 38). In fact, several researchers have already pointed out that the reasonable action is to transfer without modifications source names and avoid, thus, comic and nonsensical translations such as Jorge Arbusto for George Bush (Torre 1994: 104), Bertín Esperanza for Bob Hope or Julius Churches for the Spanish singer Julio Iglesias (Santoyo 1987: 46).

The rehabilitation of source names in contemporary translations, as Franco Aixelá (2000: 131) states, takes places thanks to a gradual change in the poetics, that is, in the norms that regulate the communication process that translation is. Usually hand in hand with changing ideologies and socio-cultural contexts, the adaptation of norms to new circumstances allows both translators and audiences to develop different visions of the world, and even “a revision of the traditional notion of what constitutes a correct translation” (Hermans 2013: 4). It is implied, then, that professionals can choose whether or not to follow the changes in the norms of translation, they can comply or disagree with general tendencies, practical recommendations, and pre-established cases, leaving the door open to “a convenient way of introducing novelties into a culture, without arousing too much antagonism” (Xianbin 2007: 28).

Despite norms being a central topic of research and debate within Translation Studies, their constraining nature and long-term adaptation has not been widely explored in relation to Native American names. Peculiar as these may be, few studies attend to the characteristics and transcultural possibilities of this type of anthroponyms when they are involved in the translation process. It has been Moya (1993; 2000) who has, finally, put in the academic mouth what society thinks about naming practices among Indian communities. Moya (1993; 2000) has twice analyzed Native American names and their particularities in relation to other kinds of names, general norms, and specific exceptions. He even offers examples of Indian names to explain his reflections. The recommendation that Moya finally gives in both instances is to translate Native American names, for these anthroponyms do not fit the formal, semantic and functional characteristics that he uses to classify names into normal and exceptional categories. But how does Moya arrive at such a conclusion?

First of all, Moya’s system of classification differentiates names with, on the one hand, real and, on the other, fictitious referents, creating a separation of anthroponyms that establishes opposite norms for these two groups. Whereas proper names with real referents are kept in the original language, the fictitious ones are linked to the formula “a mayor carga simbólica del signo del nombre mayor es la obligación de traducirlo” [the greater the symbolic load of the name sign, the greater the obligation of translating it] (Moya 1993: 239). However, Native American names are defined as an exception in each of the groups, placing them next to historically relevant figures (popes, prophets, royalty…) and allegorical fictitious names. This suggests, according to Moya’s reflection (1993; 2000), that Indian names do not fit within the Spanish conceptualization of what proper names look like, independently from the socio-cultural accuracy and authenticity of his examples.

Moya (1993: 239; 2000: 43), in addition, deliberates about the characteristics of American Indian names, resolving that the meaning of these anthroponyms is transparent and manifest due to the fact that they function as nicknames. These kinds of comments contribute to reinforce the idea that, since these communities lack anthroponyms that follow Euro-American naming patterns, Indian proper names do not represent real and unique identities. Moya further supports this argument pointing out the specific history of Native American names: the source language anthroponyms that are used for the Spanish naturalization are already in English, “una traducción del nombre original indígena” [a translation of the indigenous original name], sometimes without attending to the real meaning in the Native languages (Moya 2000: 43). Not surprisingly, Moya (1993; 2000) offers a set of examples that corroborates this conceptualization as well as the formal, semantic and functional characteristics that he has attributed to Native American names in the first place.

The examples used to illustrate the onomastic reality of American Indian communities are well-known anthroponyms both inside and outside the US borders: they either refer to historically relevant figures or are part of the popular culture. These names are: “Toro Sentado (Sitting Bull),” “Alce Negro (Black Elk),” “Caballo Loco (Crazy Horse)” (Moya 2000: 39), “Tecumseh, Cochise, Seattle, and Tomahawk” (Moya 2000: 43), “Bailando con lobos, Cabello al viento, En pie con el puño en alto” (Moya 1993: 239).[7] It is revealing that there is neither a single example of a Christian name, typical among Indians since the nineteenth century when many were enrolled in boarding schools or listed in population scrolls nor a name followed by a surname. Moya, in fact, does not notice or comment the possibility of having a specific repertory for the 21st century, one that mixes Euro-American functionality with Indian traditions and transcultural naming legacies and that makes translation more difficult and highly unexpectable.

Moya’s views are grounded in the mythical image Euro-American society has of Native peoples, associated exclusively with stereotypical naming practices and identities, whether they refer to real people (Sitting Bull or Tecumseh) or to fictional constructions (Dances with Wolves). The examples, in addition, expose the Eurocentric imagery surrounding the presence of Indians and their cultures in literature and how these ideas shape translation strategies in Spain. Although the anthroponyms mentioned above are offered as a representative sample of Native American naming practices, all of them show almost the same format (name formed by English words or by Native language words) and none incorporates any kind of surname, whether Euro-American or formed by English words. Moya, thus, represents the academic and social unawareness about the transhistorical validity of such a structure and reinforces the general views of the society and the translation profession about what Indian names and identities look like.

Last but not least, Moya’s norms concerning names also arise from a comparison between Native American and Euro-American names in relation to translation. In fact, Moya (2000: 44) mockingly mentions the names of Paul Newman and Robert Redford with the possible translations of the two surnames (Hombre Nuevo and Prado Rojo)[8] if they were to be rendered into Spanish just as happens with Indian names. The transcultural contrast between the Euro-American and Indian naming practices might benefit both the source and the target cultures, for the former would be represented more respectfully and the latter would learn about the diversity of anthroponyms beyond its boundaries. However, Moya overlooks the naming and identity particularities of Native Americans in favor of a Eurocentric conceptualization of the Other thanks to his ironic, Hollywood-centered exemplification: by comparing only names of famous people, both Native and Euro-American, he confirms the Western conceptualization of the Indians as mythical, unreal figures, non-existent out of stereotypical movies and romanticized stories of the historical past.

3. Survey material and classification

In order to observe the extent to which stereotypes about Indians shape the Spanish reception of names, it is necessary to study what translators have actually done when source texts show the complex reality of names and identities of US indigenous communities. The present survey, then, is constructed around the Spanish renderings of Native American literary works, considering their temporal, thematic and authorial particularities. The books selected, briefly described below in chronological order of translation, are representative of the forty-seven renditions available in Spain. First of all, they cover different genres from anthropology to short stories, from contemporary fiction to young adult fiction. In addition, the different publication periods of the source texts and the target texts are taken into account: the original books date mainly from the 1990s and 2000s, when the publications increased, but also include texts from earlier decades; the translations cover the last four decades (1970s-2010s), since their first appearance in the Spanish market. Lastly, the selected authors are among the most important writers of the different literary periods of Native American communities, including the early decades of the twentieth century (Eastman), the first, the second and third waves of the Native American Renaissance (Momaday, Erdrich, and Alexie, respectively) or some less-known writers with different degrees of popularity (Hungry Wolf and Power).

Louise Erdrich’s Filtro de amor (1984/1987, translated by Carlos Peralta).[9] First translation of a fictional novel authored by a Native writer. In 2009 the author incorporated new sections to this book. A revised translation of it was published in Spain in 2010 (Erdrich 1984/2010a, translated by Carlos Peralta and Susana de la Higuera);[10] it incorporates those additions as well as some modifications on the previous rendition. This situation allows a comparative examination between the two translations and the two translators involved in the process.

Charles A. Eastman’s Grandes jefes indios (1918/1993, translated by Silvia Komet).[11] It is an anthropological book characterized by its original context of publication at the beginning of the twentieth century. In that era, Native authors were dependent on a group of collaborators, editors and readers who were eminently White.

Sherman Alexie’s La pelea celestial del Llanero Solitario y Tonto (1994b/1994a, translated by Marco A. Galmarini)[12] and Susan Power’s Vísteme de hierba (1994/1996, translated by Flavia Company).[13] Both books were the first publication of these writers and had a great success in US, as well as in Spain. The main difference between them is the narrative structure: Alexie’s work is formed by short stories, while Power’s has the usual non-linear narrative of many Native American novels.

Beverly Hungry Wolf’s La vida de la mujer piel roja: cómo vivían mis abuelas (1980/1998, translated by Esteve Serra).[14] Another anthropological book with a temporal context very different from that of Eastman’s writing: set and published in the late twentieth century, Hungry Wolf’s book uses a personal point of view to talk about the cultural reality of the contemporary Bloods, rather than a historical perspective.

Sherman Alexie’s El diario completamente verídico de un indio a tiempo parcial (2007/2009, translated by Clara Ministral).[15] This book is aimed at young readers, and is full of discursive and visual irony. It works as a comparative text for the other book by Sherman Alexie.

Louise Erdrich’s Plaga de palomas (2008/2010b, translated by Susana de la Higuera),[16] one of the latest renderings of this author’s writings. It has been translated by the same professional who adapted Filtro de amor for the 2010 edition, the other text by Erdrich used for this survey.

N. Scott Momaday’s La casa hecha de alba (1968/2011, translated by Amelia Salinero),[17] winner of the Pulitzer prize in 1969. The very first translation into Spanish of any book by an author considered central to the founding figures of the Native American Renaissance (Lincoln 1983: 184).

In these books, a total of 173 proper names has been found, whether referring to real or fictitious people of Native American origin. Since the archetypical formats (names formed by English words or names formed by indigenous words) are not the only type of anthroponyms in these books, a specific system of classification has been developed. This classification, unlike that of Moya (1993; 2000) presented above, does not include the distinction between names with a real referent and those with a fictitious one due to its being irrelevant for the survey.

Category A: given names.

Category A1: given names in an indigenous language without a complementary English translation (Nanabozho).

Category A2: given names in an indigenous language with a complementary English translation (AnandaAki, Pretty Woman).

Category A3: given names in English, in many cases, a translation from an indigenous language; they are mainly formed by English common words (Sitting Bull).

Category A4: given names of Euro-American style (Rosie).

-

Category B: a given name plus a surname.

Category B1: a given name plus a surname of Euro-American format (Ben Benally).

Category B2: a given name of Euro-American style with a surname formed by English common words (Thomas Builds-the-Fire).

Category C: surnames of any kind (Holy-Track, Kashpaw).

Category D: given name and/or surname accompanied by a title (King Philip).

Category E: nicknames (Pumpkin).

Table 1

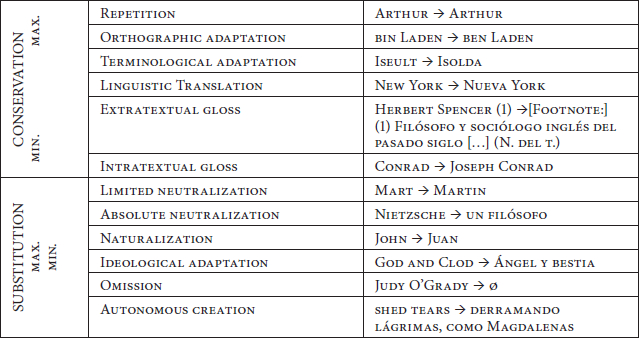

Franco Aixelá’s scale of translation strategies for names

For analyzing the resulting names in the target text, the survey incorporates the reflections of Franco Aixelá (2000: 84-94) about the diverse strategies that translators may apply when encountering names. His classification of translation techniques combines the concepts of conservation and substitution with historical and cultural details surrounding each of the names (for instance, Is the name new in the target culture? Which kind of cultural stimulus creates a certain name in the source text?). Franco Aixelá constructs a scaled classification of the different degrees of cultural adaptation that names may undergo during the translation process (Table 1).

In the present survey, there has not been any case of orthographic adaptation, absolute neutralization or ideological adaptation. The linguistic translation technique has only been applied to those names and/or surnames that bear any kind of title before them (for instance, King Philip, Uncle Bev), whereas few names have been translated by using the strategies of intratextual gloss, limited neutralization, and omission (one name with each of the techniques). There is, however, one interesting exceptional case in the set of names found in the target texts: he → Francisco (Momaday 1968: 77; 1968/2011: 86). The autonomous creation of a name out of a personal pronoun, even if it is the matching anthroponym, is a stylistic solution that does not bring about identitarian reflections, although it distorts the author’s artistic technique, an aspect that is not observed in the present survey.

4. Results from the survey and discussion

As stated above, a total of 173 names has been found, randomly distributed among the nine categories of names previously specified. The translation techniques applied to them reveal that the recommendation by Moya (1993; 2000) of rendering into Spanish any Indian name is only followed from time to time due to the anthroponomical reality of Native American communities. After all, not all indigenous peoples, whether real or fictitious, bear archetypical names formed by English words or by indigenous words as Moya’s examples showed.

4.1 Category A

Consider, for instance, the first category of the classification system used for this survey. When indigenous names are written in any Native language, the possibilities of translation are very limited, so translators in all cases (A1 = 16) choose to repeat them, preserving their original form. Names such as Wabashaw (Eastman 1918/2008;[18] 1918/1993: 9), Nanabozho (Erdrich 1984: 194;[19] 1984/1987: 190) or Petiestewa (Momaday 1968: 16;[20] 1968/2011: 27) are difficult to adapt orthographically, and their linguistic, non-referential meaning cannot be easily ascertained without extensive knowledge of both the language and the culture of each tribe. The technique of repetition may add a certain sense of exoticism to the target texts but, at the same time, gives a sense of normality to these anthroponyms which look too unusual to Spanish audiences. This transference of names without modification, then, expands the conceptualization that the target audience has in relation to names coming from different cultures and naming systems, and helps to respect the indigenous identities in their own terms.

In the case of the category A2 (n = 5), the combination of a given name in an indigenous language with an English translation asks for a merger of the repetition of the first element of the name and the naturalization of the second element. In this way, when Hungry Wolf (1980: 19)[21] states that “AnadaAki means Pretty Woman,” in the Spanish text AnadaAki is maintained and Pretty Woman is translated as Mujer Bonita (Hungry Wolf 1980/1998: 17). Once again, the Spanish audience has access to the actual reality of Indian names and, in this instance, understands the meaning of the name and the fact that it is not a mere nickname, but a name legally recognized within and outside the indigenous community corresponding to real identities equal to those of Euro-Americans.

Next to these types of proper names, the books used in this survey offer a high quota of names constructed by English words (category A3; n = 46). This, according to Moya’s point of view (1993; 2000), validates the archetypical idea that all Native Americans have this kind of name, names that can and should be translated due to their similarity with nicknames. The examples are many: Sword → Espada (Eastman 1918/2008; 1918/1993: 16), Sitting Bull → Toro Sentado (Eastman 1918/2008; 1918/1993: 55), Weasel Tail → Cola de Comadreja (Hungry Wolf 1980: 60; 1980/1998: 50), Eagle Fly → Vuelo del Águila (Hungry Wolf 1980: 60; 1980/1998: 50), Red Dress → Vestido Rojo (Power 1994: 220;[22] 1994/1996: 270). A great percentage of these names (93.62%) are rendered into Spanish, making evident that translators still evaluate Native names from a Eurocentric perspective that does not attend to the actual peculiarities of other cultural systems of naming. The ultimate consequence of this is neocolonial practices of translation and market-driven (mis)representations of the Other to be consumed by multiple Selves in their own, unchangeable terms.

There is an interesting comment to be made in relation to the ample percentage of names rendered into Spanish, one that depends on the grade of diffusion that these translations have in the target culture. Franco Aixelá (2000: 86) claims that whenever a translation of a name is the official or, at least, popular version of that name in the target culture and identifies the same entity, such technique is no longer a process of naturalization, but a terminological adaptation. Names such as Sitting Bull or Great Spirit (Toro Sentado, Gran Espíritu in Spanish) were first translated as early as the 1940s, when Spanish citizens did not know much of the English language and it was not yet a common subject in primary and secondary schools. In addition, this type of name has historical and cultural relevance, so their naturalization in the first place into Spanish answered functional demands, assuring the comprehension of the target readers. However, the same reasons that made the translation of Sitting Bull and Great Spirit necessary seem to justify nowadays the naturalization of other anthroponyms never before seen in Spain (for instance Sword, Weasel Tail, Eagle Fly). Even if it is logical to avoid further confusion among the Spanish readers with new denominations for already-known individuals, this system of transcultural transference helps extensively to perpetuate the belief that Indian names are semantically loaded, transparent and equivalent to nicknames (Moya 1993; 2000).

The perpetuation of the naturalization technique for this kind of names, in addition, involves more than a simple decision concerning the linguistic circumstances of the target audience: it also comprises an ideological preference for cultural assimilation. First of all, naturalizing means adapting the naming practices to the expectations of the target culture, assigning Spanish denominations to foreign entities and usually creating estrangement, even exoticism (Franco Aixelá 2000: 90). Secondly, such a translation technique disguises source identities under an aura of commonality and similarity, absorbing the Other in order to make it recognizable as a target culture entity. Finally, translators, with this and other techniques, fail to recognize the new activist vision of translation in society and in the transcultural encounter (Tymoczko 2010): in their role of mediators, they perpetuate both a paternalizing attitude towards their readers and their linguistic skills and a hegemonic vision according to which the Other can only be understood under the homogenizing magnifying glass of the target culture.

This belief, in fact, makes translators find alternative translation techniques that subtly hide the presence of the Indian Other and the real and complex naming system of Native American communities. For instance, the translator of Eastman omitted the name Hole-in-the-Day (Eastman 1918/2008) in the Spanish text, leaving only the social reference of this character: el jefe de los ojibways (Eastman 1918/1998: 33). In this particular case, two factors seem to have joined forces to make the name disappear from the target text, namely the linguistic difficulty of this name to be rendered into Spanish, and the idea that it is irrelevant for the development of the story told by Eastman. Examples like this demonstrate that Native American identity can be erased, condensed in abstract referents if it does not fit the Eurocentric expectations about naming practices or historical importance, conceptions that are not checked or updated in relation to indigenous cultures.

The accommodation of Indian identity through the translation of names is not performed by means of deletion only. The potential knowledge of the audience, not only in the specific case of Native American cultures, but also in relation to more general cultural aspects, plays an important role in the translator’s decision-making and selection of translation strategies. When encountering the name Geronimo (Alexie 2007: 162)[23], the Spanish translator has used an intratextual gloss, rendering the famous chief’s name as el indio Jerónimo (Alexie 2007/2009: 190). This choice is probably derived from the possible confusion that the name Jerónimo, once orthographically adapted, may cause among Spanish readers, more familiar with the Catholic priest Saint Jerome. Even though the technique is aimed at avoiding misunderstanding, it shows, at the same time, the unfair treatment of the cultural and identitarian plurality of Native Americans. Few translators would select el dálmata Jerónimo for Saint Jerome, let alone a more generic, vague term such as el romano Jerónimo. However, the equivalent non-specificity has been applied to Geronimo’s name, without contemplating more respectful possibilities in relation to Native American cultures (for instance el apache Jerónimo, el dine Jerónimo) or simple references to his fame (for instance el famoso Jerónimo).

Another unusual technique has been used by the same translator for the name Tonto, which is referred to as Toro in Spain. To render the name of Lone Ranger’s sidekick (Alexie 2007: 63), the translator has preferred to substitute the name with a more famous referent, that of Pocahontas (Alexie 2007/2009: 83). This technique, called limited neutralization, has likely been chosen to compensate the opacity of Toro for present-day young readers in Spain. Although, once more, this technique helps readers to understand the cultural references, it also serves to veil the identitarian variability of Native Americans, even within the stereotypical dimension of their representation. In this particular case, substituting Tonto with Pocahontas weakens Alexie’s strategy of deconstructing stereotypes in order to show how destructive these images are for Native Americans, for their “whole life is shaped by [their] hatred of Tonto” (Alexie 28 June 1998).[24]

Unlike what has just been observed, the category A4 (n = 56) is characterized by the distinctive repetition of names, a tendency that takes place in 98.18% of the cases. The reason behind such a shared trend among translators derives from the formal aspect of this group of anthroponyms: the Euro-American appearance of Esther, Harley, King Junior, Nathan, Nector or Rosie makes translators follow the general rule of non-translation pointed out by Moya (1993; 2000) and other scholars (for example Franco Aixelá 2000; Marcelo Wirnitzer and Pascua Febles 2005). The difference between this category and the category A3 (high versus low percentage of repetition) shows that professionals do not consider certain transference options such as neutralizing, naturalizing, or omitting when facing Euro-American-looking names, simply because of their proximity to the Spanish cultural understanding of anthroponyms. Such a situation means the protection of a realistic Native American identity, although its preservation in the original form does not derive from a transcultural commitment on the translators’ side.

4.2 Category B

The following group of anthroponyms, category B1 (given names plus surname; n = 16), confirms the relation between names with a Euro-American format and their repetition (100%) in the Spanish text. This type of names and their maintenance in the Spanish versions indicate that translation professionals prioritize the form to the referent, perpetuating a Euro-American point of view in relation to naming practices. This means that no name will be modified if it fits the Eurocentric conceptualization of names and surnames, whether it indicates a historical or a fictional individual. In fact, translators make no difference between those names with a real referent (for instance Vine Deloria, Louis Riel) and the fictitious characters (for instance Ben Benally, King Kashpaw), taking for granted the fact that these Indian names function in the same way as those names that Euro-Americans consider normal do (for instance Kevin Costner, Jeanette McVay, John Wildstrand). Such an assumption promotes among translators the shared belief that names without transparent symbolic meaning must always be preserved in the translation, for they stand, formally and logically, for a normal(ized) identity.

In this way, translators find it reasonable that any surname with a native origin such as Benally and Kashpaw do not bear any semantic load: after all, if their formal and functional characteristics are identical to those of Euro-American-looking surnames, they have finally lost their primary meaning and, thus, their capacity of mentioning and defining the identity behind (Franco Aixelá 2000: 60-61). In addition, these surnames seem too obscure to be rendered into Spanish in case translators considered they still have actual meaning. Then, it is not relevant in narrative or identitarian terms that Benally, for instance, is a Navajo surname derived “from binálí ‘his son’s son, his parental grandfather’” and assigned to many individuals in tribal registers by US federal administration although “originally, the Navajos did not use surnames” (Bright 2004: 62). Equally, it is considered beside the question of translation that the surname Kashpaw comes “from Cree (Algonquian) kâspâw ‘it is brittle, crisp’” (Bright 2004: 237).

When surnames do not have the Euro-American structure but are composed of English words, translators tend to repeat the rendition pattern observed in the category A3, that is, to naturalize instead of maintaining the indigenous anthroponyms. The percentage of repeated names in the Spanish texts, then, drops from 100% in the category B1 (n = 16) to 20% in the category B2 (n = 15); naturalization is the most used technique (60% of the cases). This redistribution of percentages shows that there is a general predisposition on the translators’ side to consider Native American surnames as nicknames, just as it happened with given names, even if these surnames indicate real and official identities according to both indigenous cultural criteria and US governmental standards. Native American identities are, thus, affected and distorted by a transcultural misunderstanding that grows from the Euro-American stereotypical conceptualization of the Other.

The narrative context in which this kind of surname appears underlines the real discrimination against the Other, expressed through the incoherent translation and naming strategies that translators create in the Spanish texts. In many books, proper names are kept whereas their accompanying surnames are translated, producing anomalous combinations: Thomas Builds-the-Fire → Thomas Enciende-el-Fuego (Alexie 1994b: 93;[25] 1994b/1994a: 103), Gloria Betty Holy Hand → Gloria Betty Mano Santa (Power 1994, 284; 1994/1996, 350). Other cases show more clearly the discriminatory practices applied to Native names and surnames when they appear next to surnames of Euro-American format. This can be easily seen, for instance, in the partial naturalization of the name Charles Bad Holy MacLeod → Charles Mal Santo MacLeod (Power 1994: 101; 1994/1996: 123). In the same way, the several names adopted by a Hungry Wolf character throughout her life (Hungry Wolf 1980: 19) make evident the translative differentiation between Native and Euro-American names. In the Spanish text (Hungry Wolf 1980/1998: 17), the names Hilda Heavy Head and Hilda Strangling Wolf are translated as Hilda Cabeza Pesada and Hilda Estrangula al Lobo, leaving Hilda Beebe as the only one repeated due to the fact that its format fits “ciertas condiciones de pertenencia socialmente predeterminadas” [some socially predetermined belonging conditions] (Franco Aixelá 2000: 63).

As pointed out above, the translators apply incongruous techniques to this kind of name, making evident the underlying ideology in relation to Indian cultures and identities. Since the Euro-American conceptualization of the world tells us that Native Americans are not part of the apparently normal Eurocentric White America, their names may look impossible, incoherent and, ultimately, funny. After all, they are only half normal thanks to names such as Thomas, Betty or Charles, and their names should be treated according to the norms shared by translators: Euro-American looking names are transferred whereas those anthroponyms formed by English words are naturalized into Spanish. Consequently, translators, mainly unconsciously, render these names, independently from their existence in the real world (for instance Hilda Heavy Head), in outlandish ways, perpetuating the Euro-American mainstream features of naming practices and identitarian prototypes.

Fortunately, some surnames that are part of the category B2 are repeated in the Spanish texts due to different reasons; it seems that some translators have explored the naming reality of Native Americans and, as a consequence, have used this technique to show their commitment to a more respectful treatment of the Other. One translator has used extratextual glosses to explain the semantic meaning of the words that form some surnames when those surnames appear for the first time in the text: Henry Yellowbull (Momaday 1968: 113) and Napoleon Kills-in-the-Timber (Momaday 1968: 110) are repeated in the Spanish text and a footnote presents their respective translations: literalmente «Toro amarillo» (Momaday 1968/2011: 118) and literalmente «El que mata en el bosque» (Momaday 1968/2011: 115). The name of Arnold Spirit, Alexie’s main character (2007; 2007/2009), is also kept and no explanation is offered, allowing the Spanish young audience to meet the reality of Indian peoples. In the case of Erdrich’s Plague of Doves (2008),[26] the name Seraph Milk has been repeated in the Spanish text (2008/2010b) probably because other similar names with Euro-American referents (for instance English Bill, Reginald Bull) appear in the translation without any modification. The fact that this translator has kept in the original version all but one name (which will be commented in the next section) confirms the translation norms concerning names, for all anthroponyms, whether real or fictional, lack literal semantic meaning even if they may be symbolically loaded within the story they belong to.

4.3 Category C

The category C (n = 6) puts together surnames of both Euro-American and Native appearance mentioned in isolation from their corresponding given names. The data show the same distribution pattern as the previous category (B1 and B2). The surnames Benally, Kashpaw or Peace, which match Eurocentric naming practices, are repeated in the Spanish texts, whereas those surnames formed by English words (Builds-the-Fire, Holy Track, WalksAlong) are naturalized into the target language. This confirms the tendency observed in category B2 as well as its consequences and causes: translators, immersed in the Eurocentric conceptualization of the world around us, classify and deal with surnames according to their (un)usual appearance, strengthening the uninformed meeting with the Other and the distorted stereotypes and hegemonic conceptualizations of the culturally different.

The surnames Peace and Holy Track are representative of this situation. They appear in the same text, Erdrich’s Plaga de palomas (2008: 17; 2008/2010b: 30), but they have been treated in two opposite ways by the translator, who, as stated above, has kept in English all, including the surname Peace, but one name, Holy Track, in the Spanish version of the text. Holy Track, rendered as Sendero Sagrado, is one of the few names in the book which has a real referent, as Erdrich herself points out in the novel’s acknowledgement section (Erdrich 2008: 313; 2008/2010b: 381). On the one hand, the performance of this translator confirms the importance of learning the anthroponomical particularities of other cultures in order to avoid treating the real and fictional identities of the Other in a prejudicial way. On the other hand, the translation of Holy Track, despite its connection with a real identity, highlights the fact that Moya’s norms (1993; 2000) are not actually followed by translators, due to the force that traditional Eurocentric conceptualization of the Indian names and identity still has on Spanish translators.

4.4 Category D

When given names and/or surnames appear in the texts with a personal title (category D; n = 9), they usually have the title translated into Spanish and the actual name kept in its original language, a technique called linguistic translation (Franco Aixelá 2000: 86-87). The application of such technique to the anthroponyms studied in this survey creates the illusion of translators favoring the conservation of these anthroponyms. However, all of the names included in the category D follow the Euro-American pattern, making possible the maintenance of all the names in the translations: Uncle Bev → tío Bev (Erdrich 1984: 78; 1984/1987: 82), Mrs. Lamartine → señora Lamartine (Erdrich 1984: 223; 1984/1987: 215). This partial translation of personal names is derived from the existing tradition in the target culture about addressing titles and courtesy forms. However, in some cases, it has already established a popularly-accredited Spanish version of certain Native names, such as King Philip → Rey Philip (Eastman 1918/2008: n.pag.; 1918/1993: 62) and Chief Joseph → jefe Joseph (Eastman 1918/2008: n.pag.; 1918/1993: 121), distorting the Indian identity and, at the same time, settling the basis for the perpetuation of misconceptions and stereotypes.

4.5 Category E

The last category (category E; n = 4) shows that the Native American naming systems distinguish between proper names and nicknames, a reality that goes against the Eurocentric conceptualization of Indian names as derived from or similar to nicknames. From a hegemonic point of view, nicknames are the unique anthroponyms used by US indigenous peoples, an incorrect assumption based on and contributing to the perpetuation of the mythic Indian ideal of noble and, at the same time, wild savage. According to this conceptualization of Native names, when translators face actual nicknames, they apply multiple techniques depending on the linguistic characteristics of these anthroponyms, but also on their vision of the identitiarian relevance of those nicknames.

The nickname Pumpkin, for instance, has been naturalized as Calabaza (Power 1994: 23; 1994/1996: 28), following its semantic meaning, whereas Dirty Joe, Joe el Sucio in the Spanish version (Alexie 1994b: 54; 1994b/1994a: 65), has been adapted like those names with a title shown in the previous category, that is, translating only the linguistic part of the anthroponym and leaving the Anglo-American name Joe intact. In these two cases, the translators have considered it relevant to make explicit the meaning of nicknames, so readers understand the relation between the names and their bearers’ identities, for Pumpkin is a Native girl with red hair and the character of Dirty Joe acts as the prototypic personification of the drunkard. The translator of Momaday’s novel, however, has not only substituted the nickname the chief by el Jefe (Momaday 1968: 116; 1968/2011: 122), she has also included an extratextual gloss in which she points out the discrimination that the main character suffered in the army, where he was assigned this nickname. This technique shows that, for this particular translator, nicknames and names give explicit important information about the cultures and the identities behind them. Thus, it is necessary to include such details in the translation, both to help the audience to understand the names and to make the readers go beyond the text itself.

Last but not least, there is a very interesting example in the two available translations of Erdrich’s Love Medicine: the 1987 Spanish version repeats the English nickname Rushes Bear (Erdrich 1984: 17; 1984/1987: 25), but the 2010 revision of the translation offers a Spanish naturalization of it, Espanta Oso (Erdrich 1984/2010a: 34). This change between the earliest and the most recent versions of the translation shows the disparity in the points of view that translators have in relation to the apparently simple category of nicknames. However, it also highlights how the identity behind the names is not taken into account when encountering the Other, for the 2010 option of naturalizing stands as a step backwards in the greater transcultural respect that most translators, professionals and scholars alike are advocating. At the same time, the decision of translating Rushes Bear, along with the other examples of the category E, shows the shared assumption, even norm, that nicknames should be rendered into the target language in order to offer the readers of the translation access to the semantic meaning of those anthroponyms.

5. Conclusion

The results from the present survey reveal that translators in Spain, even right into the twenty-first century, are highly influenced by the Eurocentric conceptualizations about the Indian identity and naming systems. The main reason for the results here observed is the limited transcultural comprehension that Spanish professionals have about Native American anthroponyms and their legal, historical and identitarian particularities. It is obvious that the ample variability of translation techniques is not harmful in itself, since it allows translators to face the Indian realities and their cultural differences from multiple points of view. However, the regulations and recommendations offered by researchers such as Franco Aixelá (2000) and Moya (1993; 2000) do not help in the promotion of a more respectful encounter between the Spanish Self and the Native American Other.

By means of analyzing the different categories of names of this survey, it is possible to observe that the translators do not share an actual tendency in their techniques beyond their general assumption that Indian names are not veridical entities with legal and cultural value. This lack of transcultural understanding both in the past and present makes difficult any major diachronic evolution of translation techniques, perpetuating, thus, the conceptualizations that accept the naturalization of Native American anthroponyms as a normal and adequate way of presenting the indigenous Other to Spanish audiences.

The survey, in addition, shows that the genre of books affects the decisions that translators make in relation to Native American names. Independently from their real or fictitious referents, names appearing in (pseudo)anthropological books tend to be naturalized more frequently than those included in fiction narratives. Taking into account that publishing houses have their own editorial regulations about these elements, translators may have considered it important for the fictional veracity of certain stories to keep the American atmosphere through name repetition. In the same way, those professionals translating the anthropological books can feel the necessity of clarifying the indigenous anthroponyms, so that non-expert readers may follow the text without any potential linguistic misunderstanding.

All in all, according to the results of the survey, translators should attend to the characteristics of Indian naming practices and explore the (dis)advantages of the various techniques, not only from the point of view of the target readers, but also from the point of view of the source culture. This means that, in order to respect Native American identities, it is necessary to examine the multiple circumstances around their names: the historical and personal significance of names, the tribal meaning of famous names, the transcultural origin of many surnames, and the legal dimension of such names both in the past and in the twenty-first century. The precedents are already in translated texts, as observed above with Momaday’s translation (1968/2011) and its extratextual glosses. However, translators still lack a deeper knowledge of the particularities of Indian names, a knowledge that goes beyond the cultural and racial discrimination implicit in the treatment of some anthroponyms.

For carrying out such a revolution in the practical treatment of Native American names in translation, there should be a profound revision of what scholars and translators assume about the indigenous naming systems. The background of this survey has proved that researchers like Moya present in their investigations a name reality restricted by the Eurocentric conceptualization of anthroponyms and the Euro-American stereotypical representations of Indianness. Such assumed reality is shared with translators, both professionals and trainees, perpetuating a transcultural misunderstanding that does not match the Native American viewpoints. Only when Spanish professionals working with translations acquire a basic knowledge of the naming systems of US indigenous communities will a substantial change happen in the translated literature, giving free way to the gradual implementation of new translation techniques that respect the transcultural difference of the Indian Other and lead to more committed and activist translation processes.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

This article is partially based on the research carried out for my doctoral dissertation, entitled “La traducción al español de la prosa nativa-americana: estudio crítico de la (re)construcción transcultural de la identidad indígena estadounidense” [The Translation into Spanish of Native American Prose: Critical Study of the Transcultural (Re)Construction of US Indigenous Identity], completed in 2013 under the supervision of Mª Carmen África Vidal Claramonte and Mª Rosario Martín Ruano. This investigation has been possible thanks to the funding from the Junta de Castilla y León and the European Social Fund (Orden EDU/1933/2008, November 11th).

I would also like to thank Sami Lakomäki and the two anonymous reviewers for Meta for their helpful comments and suggestions on this article.

Notes

-

[1]

All translations into English are mine.

-

[2]

Eastman, Charles A. (1902): Indian Boyhood. New York: McClure, Phillips & Co.

-

[3]

In the present paper, American Indian authorship is understood in a broad sense. It not only indicates those books created by Native American writers, but also includes collaborative autobiographies such as Black Elk Speaks, as well as the works of white people adopted into an indigenous tribe (i.e. Adolf Hungry Wolf). Some borderland cases have been included in order to attend to the transnational reality of American Indians and First Nations.

-

[4]

Deloria, Vine (1969): Custer Died For Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

-

[5]

In Spain, the practice of translation is regulated by law only when it deals with legal documents. Translators have to get a certification by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation allowing them to do sworn translations within the country.

-

[6]

In April 2011, having in mind the near marriage of Prince William and Kate Middleton, Fundéu BBVA (2011), an institution for the correct use of Spanish language in media, recommended the translation of Kate Middleton’s given name as Catalina. This recommendation was based on her incorporation to the English royal house, following the tradition of rendering into Spanish the names of the members of European royal families. Fundéu BBVA (Last update: 05 July 2014): Visited 05 July 2014, <http://www.fundeu.es/recomendacion/kate-middleton-sera-catalina-cuando-forme-parte-de-la-familia-real-904/>.

-

[7]

“Bailando con lobos, Cabello al viento, En pie con el puño en alto” (Moya 1993: 239) are the Spanish translations of the names Dances with Wolves, Wind in His Hair, and Stands with a Fist, all of them fictional characters in the movie Dances with Wolves (1990).

-

[8]

As stated in the text, Moya (2000: 44) gives Prado Rojo (red field) as translation of the surname Redford, making vado rojo a more direct translation.

-

[9]

Erdrich, Louise (1984/1987): Filtro de amor. (Translated by Carlos Peralta) Barcelona: Tusquets.

-

[10]

Erdrich, Louise (1984/2010a): Filtro de amor. (Translated by Carlos Peralta and Susana de la Higuera) Barcelona: Tusquets.

-

[11]

Eastman, Charles A. (1918/1993): Grandes jefes indios. (Translated by Silvia Komet) Palma de Mallorca: José J. de Olañeta.

-

[12]

Alexie, Sherman (1994b/1994a): La pelea celestial del Llanero Solitario y Toro. (Translated by Marco A. Galmarini) Barcelona: El Aleph.

-

[13]

Power, Susan (1994/1996): Vísteme de hierba. (Translated by Flavia Company) Barcelona: El Aleph.

-

[14]

Hungry Wolf, Beverly (1980/1998): La vida de la mujer piel roja: cómo vivían mis abuelas. (Translated by Esteve Serra) Palma de Mallorca: José J. de Olañeta.

-

[15]

Alexie, Sherman (2007/2009): El diario completamente verídico de un indio a tiempo parcial. (Translated by Clara Ministral) Madrid: Ediciones Siruela.

-

[16]

Erdrich, Louise (2008/2010b): Plaga de palomas. (Translated by Susana de la Higuera) Madrid: Ediciones Siruela.

-

[17]

Momaday, N. Scott (1968/2011): La casa hecha de alba. (Translated by Amelia Salinero) Valencia: Appaloosa Editorial.

-

[18]

Eastman, Charles A. (1918/2005): Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains. Edition by Project Gutenberg. (Last update: 08 January 2013): Visited on 05 July 2014, <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/336/336-h/336-h.htm>.

-

[19]

Erdrich, Louise (1984): Love Medicine. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

-

[20]

Momaday, N. Scott (1968): House Made of Dawn. New York: Harper & Row.

-

[21]

Hungry Wolf, Beverly (1980): The Ways of My Grandmothers. New York: William Morrow & Co.

-

[22]

Power, Susan (1994): The Grass Dancer. London: Picador.

-

[23]

Alexie, Sherman (2007): The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. New York: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

-

[24]

Alexie, Sherman (28 June 1998): I Hated Tonto (Still Do). Los Angeles Times. (n.d.) Visited on 05 July 2014, <http://articles.latimes.com/1998/jun/28/entertainment/ca-64216>.

-

[25]

Alexie, Sherman (1994b): Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven. New York: Grove Press.

-

[26]

Erdrich, Louise (2008): Plague of Doves. London: Harper Perennial.

Bibliography

- Allerton, Derek J. (1987): The Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Status of Proper Names: What Are They, and Who Do They Belong To? Journal of Pragmatics. 11(1):61-92.

- Bandia, Paul F. (2008): Translation as Reparation: Writing and Translation in Postcolonial Africa. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Bright, William. (2004): Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Brownlie, Siobhan (2008): Descriptive and Committed Approaches to Translation Research. The Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge, 77-81.

- Cámara Aguilera, Elvira (2009): The Translation of Proper Names in Children’s Literature. Anuario de investigación en literatura infantil y juvenil. 7(1):47-61.

- Carbonell i Cortés, Ovidi (1997): Traducir al otro. Traducción, exostismo, poscolonialismo. Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

- Chesterman, Andrew (2006): A note on norms and evidence. In: Jorma Tommola and Yves Gambier, eds. Translation and Interpreting: Training and Research. Turku: University of Turku, 13-19.

- Clements, William M. (1991): ‘Identity’ and ‘Difference’ in the Translation of Native American Oral Literatures: A Zuni Case Study. Studies in American Indian Literatures. 3(3):1-13.

- Cronin, Michael (2006): Translation and Identity. London and New York: Routledge.

- Dollerup, Cay and Appel, Vibeke, eds. (1996): Teaching Translation and Interpetring 3: New Horizons. Paper from the Third ‘Language International’ Conference, Elsinore, Denmark, 1995. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Espinal, Mª Teresa (1993): Criterios lingüísticos para la traducción de los nombres propios al catalán. EUSKERA: Euskaltzaindiaren lan eta agiriak. 39(3):1309-1331.

- Ferguson, Harvie (2009): Self-Identity and Everyday Life. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Franco Aixelá, Javier (2000): La traducción condicionada de los nombres propios (inglés - español). Salamanca: Ediciones Almar.

- Hermans, Theo (2013): Norms of Translation. In: Carol A. Chapelle, ed. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 1-7.

- Hirschfelder, Arlene and Beamer, Yvonne (1999): Native Americans Today: Resources and Activities for Educators, Grades 4-8. Englewood: Teacher Ideas Press.

- Lee-Jahnke, Hannelore (2011): Interdisciplinary Approach in Translation Didactics. Rivista internazionale di tecnica della traduzione. 11:1-12.

- Lincoln, Kenneth (1983): Native American Renaissance. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Malmkjaer, Kirsten (2005): Norms and Nature in Translation Studies. SYNAPS. 16:13-19.

- Mateo Martínez-Bartolomé, Marta (1994): ¿Lady Sneerwell o Doña Virtudes? La traducción de los nombres propios emblemáticos en las comedias. In: Margit Raders and Rafael Martín-Gaitero, eds. IV Encuentros complutenses en torno a la traducción. Madrid: Universidad Complutense, 433-443.

- Marcelo Wirnitzer, Gisela and Pascua Febles, Isabel (2005): La traducción de los antropónimos y otros nombres propios de Harry Potter. In: Mª Luisa Romana García, ed. II AIETI. Actes del II Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Ibérica de Estudios de Traducción e Interpretación. Madrid, 9-11 de febrero de 2005. Madrid: AIETI, 963-973.

- Mojola, Aloo O (2004): Similarity, Identity, and Reference across Possible Worlds: The Translation of Proper Names across Languages and Cultures. In: Stefano Arduini and Robert Hodgson, eds. Similarity and Difference in Translation: Proceedings of the International Conference on Similarity and Translation, New York May 31-June 1, 2001. Rimini: Guaraldi, 259-272.

- Moya, Virgilio (1993): Nombres propios: su traducción. Revista de Filología de la Universidad de La Laguna. 12:233-247.

- Moya, Virgilio (2000): La traducción de los nombres propios. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Nord, Christiane (1988/1991): Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. (Translated by Christiane Nord and Penelope Sparrow 1991). Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi.

- Robyns, Clem (1994): Translation and Discursive Identity. Poetics Today. 15(3):405-428.

- Rodríguez Rodríguez, Beatriz Mª (2011): La traducción literaria: Nuevos retos didácticos. Estudios de Traducción. 1(2):25-37.

- Ryou, Kyongjoo H. (2005): Aiming at the Target: Problems of Assimilation and Identity in Literary Translation. In: Juliane House, M. Rosario Martín Ruano and Nicole Baumgarten, eds. Translation and the Construction of Identity (IATIS Yearbook 2005). Seoul: IATIS, 96-108.

- Santoyo, Julio César (1987): La ‘traducción’ de los nombres propios. In: Fundación «Alfonso X el Sabio», ed. Problemas de la Traducción (Mesa redonda - Noviembre 1983). Madrid: Fundación «Alfonso X el Sabio», 45-50.

- Schäffner, Christina (1999): The Concept of Norms in Translation Studies. In: Christina Schäffner, ed. Translation and Norms. Clevedon and Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters Ltd., 1-8.

- Torre, Esteban (1994): Teoría de la traducción literaria. Madrid: Síntesis.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Trapero, Maximiniano (1996): Sobre la capacidad semántica del nombre propio. El Museo Canario. 51:337-353.

- Thomas, Gerald (1997): Onomastics. In: Thomas A. Green, ed. Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music and Art. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 607-614.

- Tymoczko, Maria (2010). “Translation, Resistance, Activism: An Overview,” in Maria Tymoczko (ed.). Translation, Resistance, Activism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1-22.

- Vidal Claramonte, Mª Carmen África (2007): Traducir entre culturas: diferencias, poderes, identidad. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Xianbin, He (2007): Translation Norms and The Translator’s Agency. SKASE Journal of Translation and Interpretation 2(1):24-29.

List of tables

Table 1

Franco Aixelá’s scale of translation strategies for names