Abstracts

Abstract

Translating into a language that is not one’s native language is no easy task, but one which may be necessary in certain settings. If a market niche exists for professional translators whose working language is not their native language, as studies have shown it does in Spain, it seems appropriate that translation trainees should be encouraged to develop their competence in what is generally known in Translation Studies as inverse (A-B/C) translation, in order to satisfy market requirements. Given current European Higher Education Area (EHEA) requirements for training students for the professional workplace, most translation degree programs in universities in Spain include subjects in which students are required to translate into the foreign language. This paper describes an early attempt to reconcile institutional requirements (curriculum design, assessment, reporting) and professional requirements (development of translation and instrumental competences, together with so-called softskills) in the specialised inverse translation class in the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. A competence-based, learner-centred, process-oriented curriculum was instituted.

Keywords:

- Translation teaching,

- competence-based training,

- inverse translation,

- translation technologies

Résumé

Traduire dans une langue étrangère n’est pas une tâche aisée, mais elle existe bel et bien dans certaines situations. Si, comme certaines études l’ont démontré, il existe effectivement une niche de marché en Espagne, les étudiants en traduction devraient alors être encouragés à développer leur compétence en « traduction en langue seconde », selon sa dénomination dans le cadre des études de traduction, pour pouvoir répondre aux attentes du marché. Conformément aux exigences actuelles de l’Espace européen de l’enseignement supérieur (EEES) pour l’obtention d’un poste de travail par des étudiants en formation, la plupart des programmes de grade de spécialisation en traduction des universités espagnoles comportent des matières dans lesquelles les étudiants sont appelés à traduire dans une langue étrangère. Le présent article décrit une première tentative de réconciliation entre les exigences professionnelles (développement de la compétence de la traduction et de la compétence instrumentale, ainsi que desdits soft skills ou compétences sociales) et les exigences institutionnelles (conception d’un programme d’études, évaluation, compte-rendu d’apprentissage) dans le cours de traduction inverse spécialisée de la Faculté de traduction et d’interprétation de l’Université autonome de Barcelone (UAB). Un programme d’études fondé sur la compétence, axé sur l’apprenant et orienté vers la démarche de traduction a été institué.

Mots-clés :

- Enseignement de la traduction,

- formation par compétences,

- traduction en langue seconde,

- technologies de la traduction

Resumen

Traducir hacia una lengua que no es la materna no se considera una tarea fácil y, aún así, se da en determinados contextos. Si, como algunos estudios han demostrado en el caso de España, existe un nicho de mercado para traductores profesionales que trabajan hacia la lengua extranjera, los estudiantes de traducción deberían, por tanto, ser formados para desarrollar su competencia traductora en lo que se conoce en los Estudios sobre la Traducción como traducción inversa (A-B/C), con el objetivo de satisfacer las necesidades del mercado. De acuerdo con las indicaciones del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (EEES) respecto a la formación de traductores para el desempeño profesional, la mayoría de programas de Grado de traducción de las universidades españolas incluye asignaturas de traducción inversa. Este artículo describe un primer intento de reconciliar las exigencias institucionales (diseño curricular, evaluación, justificación) y profesionales (desarrollo de la competencia traductora e instrumental, así como las llamadas softskills) en el aula de traducción inversa especializada de la Facultad de Traducción e Interpretación de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Para ello se aplicó un programa basado en competencias, centrado en el estudiante y orientado al proceso.

Palabras clave:

- Enseñanza de la traducción,

- formación por competencias,

- traducción inversa,

- tecnologías de la traducción

Article body

1. Introduction

In a globalised world in which English is used as the lingua franca of business, science and technology, diplomacy, and the media, it is not untoward to expect translators whose working language is English, to be prepared to translate into and out of English even though it is not their native language (Lorenzo 2003; Goodwin and McLaren 2003; De la Cruz 2004; Adab 2005; Pokorn 2005, 2009; Thelen 2005; Stewart 2008).

Moreover, given the current emphasis on mobility of labour within the European Union and the demand for more flexible, versatile workers who can demonstrate not only field-specific competences[1] but also cross-curricular competences (so-called soft skills, such as critical thinking, powers of decision-making, interpersonal, intercultural, management and organisational skills), responsibility lies with translation faculties to fulfil both these requirements to ensure trainee translators can become successful translation service providers (EMT Expert Group 2009).

2. The inverse translation market in Spain

Although there is a dearth of systematically conducted surveys and statistical data on the practice of inverse translation in Spain, the few studies that exist show that professional translators do indeed provide translation services in their foreign language at some time or other in their career.

In a survey conducted by Roiss (2001) among 230 professional translators, 50 graduates from the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting of the University of Salamanca, and translators from 50 translation agencies in Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia, it was found that 84.4% of the respondents had translated into their foreign language at some point in their career, with 6.7% translating more frequently (<70%) into their foreign language than into their mother tongue. Inverse translation accounted for more than half the work of 13.3% of the translators surveyed; 25% of the work of 23.3% of the translators; and approximately 10% overall of the work of 41.1% of the translators. Zimmerman (2007) found that 60% of a sample population of 54 translator trainees had provided inverse translation services within a professional setting at some point during their studies, and Rodríguez-Inés (2008) found that of 35 freelance translators who were Spanish native speakers and used English as their working language, 100% had been asked to provide translation services in English with only 5% refusing to do so. A much more recent survey (Gallego-Hernández 2014) conducted among 500 translators showed that French was the foreign language into which texts were most often translated, followed by English and then German. Eighty per cent of those translating into English as their foreign language (162 out of 500) said they had sometimes translated legal texts. Technical and economic texts were less frequently translated into English and scientific or literary texts were never, or hardly ever, translated into English.

Although limited in scope, the aforementioned studies show that translating into the foreign language is not an uncommon task for translators in Spain. This fact, together with current European Higher Education Area (EHEA) requirements for training students for the professional workplace, thus justifies the decision made to prepare students in Spanish Faculties of Translation for this type of task, thereby enhancing their employability.[2]

3. Inverse translation in faculty curricula in Spain

In 2008, Wimmer carried out a study to determine the extent to which provision had been made for training translators in inverse translation in the degree courses in Translation and Interpreting (Licenciatura en Traducción e Interpretación)[3] that were in greatest demand in the 5 top-ranked universities in Spain, as cited in the newspaper El Mundo.[4] No consensus was found amongst the universities as to the number of core credits given over to inverse translation. As a compulsory subject, inverse translation accounted for 0-50% of the total number of credits for translation overall in the different universities’ degree programmes. In the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, non-specialised inverse translation accounted for 8 credits in the second year, and specialised inverse translation for 8 credits in the fourth year of study, i.e. 5.3% of the total number of credits for translation overall. With the introduction in 2010 of the 4-year-long EHEA compatible Degree in Translation and Interpreting (Grado en Traducción e Interpretación) non-specialised inverse translation currently accounts for 6 ECTS and specialised inverse translation (no longer compulsory) accounts for 6 ECTS. Inverse translation thus represents a maximum of 5% of the total number of credits for translation overall if students study both non-specialised and specialised translation, which is not always the case. Mindful of market requirements in Spain, the fact that only 2.5% of core credits is devoted to inverse translation would appear to be at odds with one of the main goals to be achieved with the creation of the EHEA.

4. Reconciling institutional and professional requirements

Institutional requirements with regard to translator training have to do with syllabus design and development, and include questions of teaching methodology, assessment, and reporting. Within the context of the common model of higher education established within the EHEA, comparable and compatible qualifications are required.[5] Syllabi must necessarily make reference to competences to be developed, intended learning outcomes, and assessment procedures, with evidence of students’ performance throughout the learning process being provided in a student’s portfolio.

Professional requirements have to do with developing the skills and attributes that trainees need to improve their performance and enhance their employability. In 2009, the European Commission’s Directorate–General for Translation established a reference framework for the professional competences to be developed by trainee translators. The competences listed were: translation service provision competence, language competence, intercultural competence, information mining competence, thematic competence, technological competence. “This reference framework should be understood within the overall context of university education for translators, which goes beyond the specifically professional competences listed below. It sets out what is to be achieved, acquired and mastered at the end of training or for the requirements of a given activity, regardless where, when and how” (EMT Expert Group 2009: 3).

The syllabus for the final year Spanish-English specialised translation class in the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona was designed to satisfy both institutional and professional requirements.

5. Satisfying institutional requirements

Satisfying institutional requirements focused on the design and development of a syllabus compatible with the common model of higher education established within the EHEA.

5.1. Syllabus design

The syllabus designed for the specialised inverse translation class described in this paper was thus competence-based (Nunan 1988b; Kelly 2007), process-oriented and learner-centred (Brindley 1984, 1989; Nunan 1988a). It was task- based (Candlin 1987; Nunan 1989, 2004), and incorporated a problem-solving methodology with a collaborative teacher-student approach to learning (Nunan 1992).

Course content included both pedagogical tasks to develop and monitor progress in the acquisition of translation competences, and real-life rehearsal translation service provision tasks designed to familiarize students with the demands of the professional translator’s workplace. Pedagogical tasks included a diagnostic test; copy-editing exercises; exercises to develop documentation and instrumental skills; written and visual reports by students explaining their decision-making processes when solving translation problems; and self-assessment and evaluation questionnaires. Real-life rehearsal translation service provision tasks involved the translation of extracts (150 words; confidential data substituted) from four authentic[6] texts from different specialist areas of interest to the translation market and a large-scale 10,000-word translation (Term Project), presented ready for publication in both hard-copy and digital format.

Approximately 60 final-year students attended the specialised inverse translation class for a period of one semester. Two two-hour sessions were programmed each week – one in a traditional classroom setting (translation workshops), the other in a multimedia classroom. Most students were native speakers of Spanish although some Erasmus exchange students attended the classes as required by their Learner Agreements. Faculty enrolment procedures defined the characteristics of the resulting multicultural, multilingual, mixed-ability group.

Students were encouraged to work in different types of groups or learning communities, and to participate in regular peer-conferencing sessions (Nunan 1988b; Boud, Cohen et al. 2001). Whether as a large community of practice in a classroom setting, or a small community of purpose as a group working on a project, or as an online community as translators in a translators’ forum using the World Wide Web or the university’s Virtual Campus, each individual’s experience, knowledge etc. was used to share and negotiate control of the group’s learning process so that in the end gains were made by all members of the group linguistically, socially and, ultimately, professionally.

A blended learning approach (Rodríguez and Fox 2006; Galán-Mañas and Hurtado Albir 2010) to classroom activities was used. Whilst students had regular face-to-face contact with teachers responsible for their course twice weekly, assignments (tasks) were downloaded and, once completed, uploaded on to the Campus Virtual. Familiarising students with the use of ICTs anticipated the realities of the professional translator’s workplace.

Responsibility for developing the syllabus was divided between two teachers – one, a bilingual Spanish native speaker, responsible for documentation and translation technology classes, and the other, a bilingual English speaker, responsible for the translation workshops (Villa, Thousand et al. 2008; Römer and Arbor 2009; Pokorn 2005, 2009).

5.1.1. Learning goals

Table 1 shows the learning goals (competences) set for the course. Indicators of the development of these competences served to assist students in focusing and monitoring their learning process as well as providing teachers with competence-related criteria for assessment purposes.

Table 1

Competences to be developed and their indicators

5.1.2. Assessment

Assessment [8] was criterion-referenced (Nunan 1988a, 1988b; Adab 2000; Way 2008). The criteria used were clearly specified and understood in terms of students’ level of attainment of learning goals. Indicators of the competences to be developed (Table 1) served as assessment criteria. Students were informed at the start of their course of the criteria used for assessment and of the weighting given to the different tasks they had to complete (Appendix 2).

Ongoing, formative assessment of learning outcomes, in conjunction with the use of self-assessment questionnaires, was used to monitor progress in students’ attainment of learning goals.

Summative assessment determined whether or not students, individually or within a group, evidenced attainment of the overall course objectives.

5.1.3. Evaluation

Feedback was incorporated into the syllabus design to inform pedagogy and to make any necessary adjustments to the syllabus in subsequent semesters. This was done through the use of an evaluation questionnaire. Because students were actively involved in their learning processes, which took place in collaboration with their teacher and peers, their comments on different aspects of syllabus design were of importance in making adjustments in those areas of interest to the group as a whole (Fox and Rodríguez-Inés 2013).

5.1.4. Accountability

Given the need for transparency with regard to EHEA requirements, learning goals, expected learning outcomes; and assessment criteria for the course were posted online on the UAB Faculty of Translation home page in the form of a guide to the subject (Guía de la asignatura).

Moreover, the university’s virtual learning environment (Campus Virtual) served to keep a permanent record of materials uploaded; items of interest; tasks set and work submitted for assessment; interim results of continuous assessment; and teacher-student and/or student-student correspondence in forums designed as learning communities.

Students’ progress in developing the competences established as learning goals was evidenced through their completed worksheets, self-assessment questionnaires, translated texts, Term Project, and evaluation questionnaire – all of which were assessed using the indicators cited in Table 1.

5.2. Course content

The task-based syllabus of the specialised inverse translation class was comprised of a series of pedagogical and real-world rehearsal tasks aimed at developing the competences established as course objectives or learning goals. They included a diagnostic test; copy-editing exercises; ICT worksheets (Rodríguez-Inés 2014); translations from different specialist fields; written and visual reports on translation problem solutions; an extended translation project; self-assessment questionnaires; and an evaluation questionnaire.

5.2.1. Diagnostic test and copy-editing

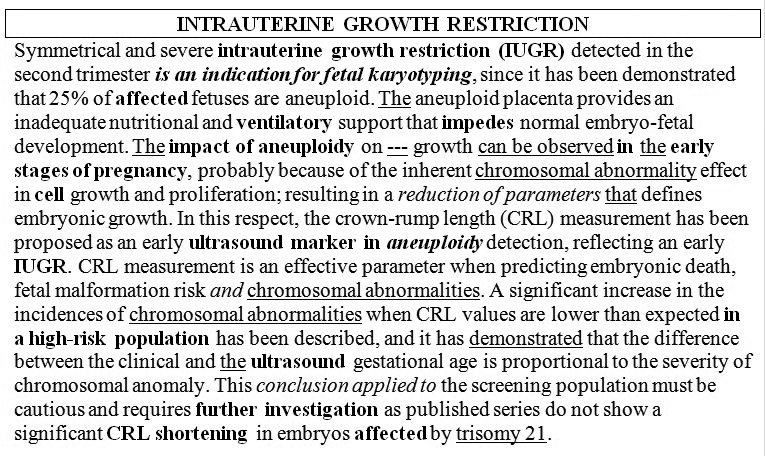

Given that the syllabus was needs-based, a diagnostic test was given on the first day of class. Students were invited to submit, individually, and within a period of one week, their translation of the text “Crecimiento intrauterino retardado,” using whatever resources they wished to complete their work. After completing their translations, they were asked to fill in a self-assessment questionnaire which was submitted along with their texts. The students’ translations were then used as a basis for copy-editing exercises with a view to focusing attention on aspects of the translation process and final text production specific to the field of medicine (translation workshops).

Using input from the translation workshops, peer discussion sessions, and multimedia classes focusing on documentation and ICTs (Appendix 3), students were asked to proofread and copy-edit their original translations on three separate occasions, submitting successive versions of their translated texts – the first incorporating corrections in bold (at week 1), the second incorporating corrections underlined (at week 2), and a final version (at week 3) with corrections in italics. After submitting their final versions of the diagnostic test, the self-assessment questionnaire was again administered. By comparing the outcome of both questionnaires it was possible to see how much more aware students were of what was involved in a specialised translation task; how much more aware they were of the competences they had to develop individually; and the effect on their performance of work carried out in the multimedia classroom and the translation workshops. The use of a diagnostic test in conjunction with copy-editing exercises and ICT worksheets was designed to prepare students for the translation of four texts from different specialist fields which would be assessed to determine their level of attainment of course objectives.

Figure 1 shows corrections made by students in their first (in bold type), second (underlined) and final version (in italics) of a translated text after attending practical lessons and translation workshops.

Figure 1

Copy-editing a text (modifications included)

Figure 2 shows the self-assessment questionnaire used after students’ first translation of the text “Crecimiento intrauterino retardado” and after the final version submitted.

Figure 2

Self-assessment questionnaire

5.2.2. Translations

Once students were familiar with the way in which they were encouraged to go about their translation work, they were asked to translate, individually, texts from four different specialist fields (medical, technical, financial, legal) (Appendix 1). When undertaking these tasks, students were required to put their language to a wide range of uses. They were required to translate texts for different English-speaking audiences using specialised language that had not been mastered (or had been imperfectly mastered as they had received no English language training in any of the specific subject fields), drawing on their own resources to negotiate and make meaning. Close coordination between the work done in the multimedia classroom and the translation workshops aimed at developing the skills and strategies necessary to compensate for any shortcomings in students’ correct, appropriate and meaningful use of language in context. Overall improvement in students’ performance evidenced the degree to which this coordination was successful.

5.2.3. Report on the solution of translation problems

At the same time as students submitted their translations for assessment, they were required to report on the decision-making and problem-solving processes used to solve translation problems they encountered. These were short written reports.

The example below shows a student’s justification of the solution found to a translation problem in a legal text. The aim of this type of task was to develop student awareness of the process involved in translation problem-solving. It also served teachers as a means to monitoring the development of students’ critical thinking, decision-making and problem-solving strategies.

6. Satisfying professional requirements

Satisfying professional requirements in the specialised inverse translation class focused on developing: i) students’ overall translation competence; ii) their instrumental competence and knowledge of translation technologies (Trados, WebBudget, WebCopier, WordSmithTools); iii) their critical thinking, powers of decision-making, interpersonal, intercultural, management and organisational skills.

Preparing students with their occupational goals in mind, however, also entailed familiarising them with the professional environment within which they would operate in the future. Ready access to multimedia classrooms, the use of Internet and the UAB’s virtual learning environment, Campus Virtual (Rodríguez-Inés and Fox 2006) provided the necessary means to this end.

By using the Internet and the Campus Virtual, it was possible to simulate the professional translator’s workplace as students worked, communicated, and coordinated with their clients (teachers) and colleagues (fellow group members) from independent workstations downloading/uploading/compressing files via the Campus Virtual (mirroring the way in which freelance translators receive and return work online); met deadlines (access to accounts to upload translations was not possible after a specific date and time); and consulted and advised on translation, documentation and software problems through the use of translator forums.

Tasks specifically designed to satisfy professional requirements included the preparation of invoices to accompany each translation; the translation of a web page, and the translation of an extended text for a financial institution ready for publication in the form of a booklet.

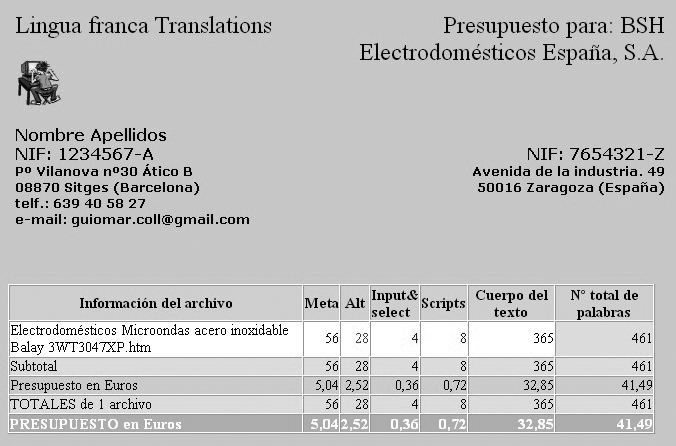

6.1. Estimate for the translation of a webpage generated with WebBudget

Before fulfilling the client’s request to translate a web page, students were required to produce an estimate for the translation of a webpage using the program WebBudget.

Figure 3

Example of an estimate produced using WebBudget

6.2. Translation of a webpage using WebBudget

Once students had submitted their estimates, they were required to translate a webpage using the program WebBudget (see source text in Appendix 1).

Figure 4

Example of the translation of a webpage using WebBudget

6.3. Term Project

In order to assess students’ overall attainment of learning goals, they were required, in groups of 7, selected in alphabetical order from the class list, to translate a large-scale Term Project (10,000 words) and to submit the translation ready for publication in the form of a booklet. The text to be translated was one produced by a leading Spanish bank on the subject of mortgages. Taking advantage of the presence of international students in the class, all groups were made up of native Spanish speakers and international exchange students whose L1 language was not necessarily Spanish. No specific roles were assigned to the members of the groups; they were responsible for organising, planning, managing and executing the translations themselves. The Term Project was designed to simulate professional practice working on a single, large-scale project within a group of multilingual, multicultural translators one had never worked with before. The following is an example of the translation of the introduction to the extended text used for the students’ Term Project. It should be noted that the project was presented in digital and hard-copy format.

Figure 5

Example of a student group’s translation of an extract from the Term Project text

6.3.1. Report on the solution of translation problems

After completing their Term Project, each group of students was required to give a report, in class, explaining three different translation problems they had encountered. Having by now developed their instrumental competence, instead of submitting written reports, students presented their reports in the form of a PowerPoint presentation. Not only did these presentations focus students’ attention on the decision-making processes at work when solving translation problems, thereby developing their ability to think critically, but by presenting their reports in class they were able to share their experience with the learning community as a whole. Trainers were, moreover, provided with an objective means of assessing critical thinking, decision-making and problem-solving strategies, as well as instrumental competence.

The following is an example of the solution of one of the translation problems explained in one of the PowerPoint presentations given by one of the student groups:

PROBLEM-SOLVING PROCESS (as reported by the students):

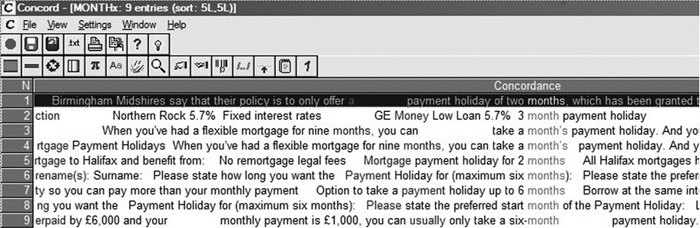

After some initial searches on the Internet we came up with two options as possible equivalents: waiting period and payment holiday.

The term waiting period was ruled out after searching it in the corpus of mortgages as it means something different (i.e. from the time the final loan papers are signed to receipt of the actual loan money).

Figure 6

Screenshot of concordances of “waiting period”

A truncated search of “payment holiday*” showed that it was the right equivalent as it appeared in the same context as in the ST.

Figure 7

Screenshot of concordances of “payment holiday”

The definition of payment holiday was checked in a specialised glossary: “a short break from regular mortgage repayments sometimes offered with flexible mortgages….” (http://www.nexmortgage.co.uk/mortgages/jargonbuster/#p)

Apart from providing us with the term payment holiday, the corpus also helped us with possible verbs that would collocate with it: apply for, take, allow.

A further problem, this time of a strategic nature, was whether to use years or months when talking about mortgage loans and payment holidays as this is what the ST did respectively.

A small corpus on payment holidays was specifically built for the purpose of finding out more about the way time was expressed. Webpages from banks such as NatWest, Barclays, Lloyds and Halifax containing the expression payment holiday were downloaded and added to the main corpus.

Concordances were extracted for “month*” and “year*” including “payment holiday*” as a context word.

Figure 8

Screenshot of concordances of “month*”

Figure 9

Screenshot of concordances of “year*”

Finally, on the basis of the evidence obtained from the corpus, we decided to use years for periods over 12 months.

6.3.2. Evaluation questionnaire

In conjunction with their Term Project translation and PowerPoint presentation, students completed an evaluation questionnaire which effectively constituted a self-assessment of their ability to work in a multilingual, multicultural environment (Q 11, 12); and their ability to plan, coordinate and manage a large-scale project (Q 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11). Comments from some students pointed to the fact that, as a result of working as a group, they had not only learned to plan, coordinate and manage a project, but they had also learned how to accept different points of view regarding the solution of translation problems, how to justify their own choices and to defend them diplomatically.

Responses to the questionnaire also provided teachers with feedback as to whether or not institutional and professional requirements had in fact been met by the syllabus designed. Students’ answers reflected their awareness of their learning process as regards the development of translation competence (Q 13, 16) and their ability to think critically (Q 5, 9, 14, 15, 17). This information, together with the results of the assessment of students’ translation tasks, provided the information necessary to make adjustments to the syllabus design as required.

Table 2

Evaluation questionnaire

6.3.3. Assessment of the Term Project

Assessment of the Term Project took into consideration the punctual completion of the project; the tidy presentation of files, etc. on the CD; the meaningfulness, and overall coherence of the translated text; appropriateness of the corpus used for documentation purposes; the quality of the report on the translation process plus screenshots; and responses to the evaluation questionnaire regarding interpersonal skills, skills in project design, management, and coordination.

7. Conclusions

A competence-based, task-based, learner-centred, process-oriented curriculum is highly recommended for accommodating institutional and professional requirements in tertiary education institutions.

Defining the key competences required in a behavioural domain, converting them into course objectives to be attained through the completion of appropriately designed tasks assessed using criteria derived from the competences identified, provides an effective framework within which a student’s progress and level of attainment of course objectives may be monitored and assessed. Self-assessment and evaluation questionnaires, as well as reports on decision-making and translation problem-solving processes are important tools to raise students’ awareness of the processes at work when translating.

As a foretaste of the working environment of the professional translator, the use of virtual learning environments encouraged students to become more autonomous learners and more responsible translators. Working conditions were more flexible in terms of time and place, and as a result students organized their work better (for example, punctual submission of assignments improved). It was also possible to simulate real-life client–translator / translator–translator relationships so that communication and coordination among students (the community of translators) and between students and teachers (through forums, tutorials, e-mail, news) was highly effective. It also satisfied institutional demands for transparency, by ensuring that the course syllabus together with the objectives and assessment criteria set for the course were posted for consultation from the outset, and that a permanent record of teaching materials used, students’ work submitted, marks given, and teacher–student / student–student communications were available for consultation at any time.

Attention should however be drawn to two aspects of the syllabus which were subsequently modified as a means to improving students’ performance and their overall assessment. One was the incorporation into students’ overall assessment of the Term Project reports on translation problems and solutions (PowerPoint presentations). The other was a change in workload involved in the course (deemed by many to be excessive).

As regards the PowerPoint presentations, it was found that they were a particularly useful means of assessing students’ instrumental and communicative competence as well as their critical thinking, powers of decision-making, and interpersonal, management and organisational skills.

Consequently the following assessment chart was drawn up and trialled at the end of the following semester with a new group of 60 students. Assessment was carried out by both teachers responsible for the course and given a weighting within overall assessment. Table 3 shows the proposed assessment chart.

Table 3

Template to assess group PowerPoint presentations

As a result of students’ complaints about the excessive workload (individual translation of four texts from different specialist areas plus an extended Term Project in groups, all within one semester), it was decided to reduce the subject areas of the four texts to be translated individually to only one, that of the extended Term Project. Four different 150-word extracts were taken from the Term Project text and used to preview different translation problems that would arise in the course of its translation.

The problems of management and organisation arising out of group work in the Term Project were described in terms of the lack of commitment of some group members; problems of conflict management; and demotivation as a result of having to work with others in a group with whom they had never worked before. Incompatible timetables and work schedules were most often cited as a particular problem with most groups finding it difficult to find effective alternatives to face-to-face meetings in the faculty. Group forums, file hosting and sharing services (e.g. GoogleDocs; Dropbox) provided three of the most useful solutions.

Only at a much later date, again thanks to feedback from students’ evaluation questionnaire, was it possible to find an effective solution to the other problems of lack of commitment, conflict management and demotivation. The solution was found in determining specific roles for students working in groups on three extended translations, in groups of three, alternating the roles of documentalist, translator, and copy-editor (Fox and Rodríguez-Inés 2013).

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1. Examples of source texts given to students to translate individually

Source text: Medical

El crecimiento intrauterino retardado

El crecimiento intrauterino retardado (CIR) simétrico y severo detectado en 2º trimestre es indicación de estudio del cariotipo fetal, habiéndose demostrado que un 25% de fetos afectos son aneuploides. La placenta aneuploide proporciona un inadecuado soporte nutricional y respiratorio que impide un normal desarrollo embrio-fetal. El impacto de la aneuploidía sobre el crecimiento puede evidenciarse en etapas precoces de la gestación, probablemente debido al efecto inherente de la cromosomopatía sobre el crecimiento y proliferación celular, traduciéndose en una reducción de los parámetros que definen el crecimiento embrionario. En este sentido, se ha propuesto la medición de la longitud cráneo-nalga (LCN) como signo ecográfico precoz en la detección de aneuploidías, reflejando un CIR precoz. La medición de la LCN es un parámetro efectivo en la predicción de muerte embrionaria, riesgo de malformaciones fetales, y anomalías cromosómicas. Se ha descrito un aumento significativo de la incidencia de cromosomopatías ante valores de LCN inferiores a los esperados, en población de alto riesgo, demostrándose que la diferencia entre la edad gestacional clínica y ecográfica es proporcional al grado de severidad de la anomalía cromosómica. La extrapolación de este fenómeno a la población de screening debe ser cautelosa y requiere estudios más exhaustivos, habiéndose publicado series que no demuestran una significativa reducción de la LCN en embriones afectos de T21. Por otra parte, se ha sugerido una relación entre el desarrollo precoz de un crecimiento intrauterino retardado en fetos trisóndeos y el descenso de valores séricos de alfafetoproteina (AFP), hipótesis que no ha sido confirmada en otros estudios.

Source text: Technical

4WG1919XP

800 W - 19 litros

Con grill simultáneo de cuarzo.

Selector de funciones: microondas (5 niveles), grill y microondas + grill.

Programador de tiempo de 60 minutos y dos velocidades.

Interior esmaltado.

Parrilla grill elevada.

Plato giratorio de 25,5 cm de diámetro.

Potencia grill 1.050 W.

Marcos de empotramiento opcionales; 4AW 2019 XR color gris acero y 4AW 2019 XP en acero inoxidable.

Source text: Financial

DOREMI INSTRUMENTOS, S.A.

Junta General Ordinaria de Accionistas

En virtud de decisión adoptada por el Consejo de Administración de DOREMI INSTRUMENTOS S.A. se convoca a los accionistas a Junta General ordinaria, a celebrar en Madrid, en los recintos feriales (Feria de Madrid) del Campo de las Naciones, Parque Ferial Juan Carlos 1, Pabellón 3, el día 30 de mayo de 2004 a las 12 horas en primera convocatoria, y para el caso de que, por no alcanzar el quórum legalmente necesario, no pudiera celebrarse en primera convocatoria, el día 31 de mayo de 2004, a las 12 horas, en el mismo lugar, en segunda convocatoria, con el fin de deliberar y adoptar acuerdos sobre los asuntos comprendidos en el siguiente

ORDEN DEL DIA

Examen y aprobación, en su caso, de las Cuentas Anuales y del informe de Gestión, tanto de DOREMI INSTRUMENTOS, S.A. como de su Grupo Consolidado de Sociedades, así como de la propuesta de aplicación del resultado de DOREMI INSTRUMENTOS S.A. y de la gestión del Consejo Administración, todo ello referido al Ejercicio social correspondiente al año 2009.

Examen y aprobación, en su caso, del Proyecto de Fusión de DOREMI INSTRUMENTOS, S.A. y Musical Networks S.A. mediante la absorción de la segunda entidad por la primera, con extinción de Musical Networks S.A. y traspaso en bloque, a título universal, de su patrimonio a DOREMI INSTRUMENTOS, S.A. con previsión de que el canje se atienda mediante la entrega de acciones de la autocartera de DOREMI INSTRUMENTOS, S.A., todo ello de conformidad con lo previsto en el Proyecto de Fusión.

Nombramiento de Consejeros

Designación del Auditor de Cuentas de la Compañía y de su Grupo Consolidado de Sociedades al amparo de lo previsto en los artículos 42 del Código de Comercio y 204 de la Ley de Sociedades Anónimas

Source text: Legal

Tienen los Sres. comparecientes, a juicio mío y según intervienen, capacidad legal para formalizar la presente escritura de TRASPASO DE LOCAL DE NEGOCIO, Y

== EXPONEN: ==

Que la finca objeto de esta escritura es el local de negocio ubicado en la baja del planta edificio sito de la Rambla del Mig, número setenta y nueve, de Mollet del Vallés.

Que Don Manuel y Doña Josefa López Lis son nudo-propietarios y Doña Josefa Lis Gutiérrez es usufructuaria, del derecho de arrendamiento del local referido en el expositivo anterior destinado a taller mecánico de reparación de coches, por herencia del esposo de la última y padre de los dos primeros, Don Miguel López López, fallecido el 2 de Julio de 1991, en virtud de escritura de Manifestación y Adjudicación de Herencia autorizada por el Notario de esta ciudad, Don Luis María Aragonés, el 18 de Diciembre 1991, número 1.669 de Protocolo, siendo la propietaria-arrendadora Doña María Barceló Peña, con domicilio en Mollet del Vallés, Rambla del Mig,79, 4º.

Los arrendatarios hacen constar:

a) Que el causante Don Miguel López López y Doña María Barceló Peña suscribieron contrato de arrendamiento del referido local de negocio en Mollet del Vallés, el día 1 de Septiembre de 1981.

b) Que actualmente se satisface una renta mensual de 94.306 pesetas, más los impuestos correspondientes.

c) Que llevan por tanto más de dieciocho años legalmente establecidos en dicho local, explotándola ininterrumpidamente en él el citado negocio de taller mecánico de reparación de coches.

y d) Que el derecho de arrendamiento sobre dicha finca esta libre de cargas que impidan su traspaso.

Los citados arrendatarios comunicaron a la arrendadora su decisión de realizar este traspaso y su precio, por medio de acta autorizada por el Notario de esta ciudad, Don Luis María Aragonés, en fecha 25 de Noviembre de 1999, número 3.896 de Protocolo, habiendo sido comunicada por la propietaria-arrendadora su oposición de dicho traspaso mediante acta autorizada por el Notario de esta ciudad, Don Manuel Díaz Cordobés, en fecha 20 de Diciembre de 1999, número 2.179 de Protocolo.

Appendix 2. Correction criteria for individual translations and weighting of marks for the course overall

Appendix 3

Examples of worksheets designed to develop students’ instrumental competence and, as a result, their ability to solve different types of translation problems and copy-edit their texts.

Problem with collocates and use: Numbers: words or figures? In the Spanish sentence “malformaciones…detectadas en el 2º trimestre,” which verb is usually found in this context?

Problem with use: With or without a hyphen?

“(…) de alta resolución…”

Problem with discourse: How to introduce information that contradicts a previous statement

“Contrariamente,…”

Problem with terminology: “malformación de Dandy-Walker”

Notes

-

[1]

Competences for professional translators were defined as: “translation service provision competence, language competence, intercultural competence, information mining competence, thematic competence and technological competence” by the EMT Expert Group (2009): Competences for professional translators, experts in multilingual and multimedia communication. Visited on 1. February 2016, <https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/emt_competences_translators_en.pdf>. Also Fox 1995; Kelly, Martin et al. 2003; Hurtado Albir 2007; and PACTE 2014.

-

[2]

“The role of higher education in this context is to equip students with skills and attributes (knowledge, attitudes and behaviours) that individuals need in the workplace and that employers require, and to ensure that people have the opportunities to maintain or renew those skills and attributes throughout their working lives. At the end of a course, students will thus have an in-depth knowledge of their subject as well as generic employability skills” in European Higher Education Area (2007): Employability. Bologna Process. Visited on 2. September 2016, <http://www.ehea.info/pid34786/employability-2007-2009.html>.

-

[3]

The Licenciatura en Traducción e Interpretación has since been phased out and been replaced, as from 2010, with the EHEA–compatible Grado en Traducción e Interpretación.

-

[4]

El Mundo (9 de mayo de 2007): 50 Carreras: Dónde estudiar las más demandadas. El Mundo Especiales.

-

[5]

Conference of Ministers responsible for Higher Education (19 September 2003): Realising the European Higher Education Area. Berlin Communiqué. Bologna Process. Visited on 23 September 2016, <http://media.ehea.info/file/2003_Berlin/28/4/2003_Berlin_Communique_English_577284.pdf>. Also see Education and training (2013): Diploma Supplement. European Commission. Visited on 23 September 2016, <http://ec.europa.eu/education/tools/diploma-supplement_en.htm>.

-

[6]

Following Brosnan et al. (1984: 2-3) in Nunan (2004): “adults need to see the immediate relevance of what they do in the classroom to what they need to do outside it and real-life material treated realistically makes the connection obvious.” For our purposes authentic text is not only real writing that has been published in a magazine, book or scientific journal, or online as a webpage, but it is also real writing that has been submitted to a professional translator for translation– a real-world (authentic) translation task.

-

[7]

Current trends in education increasingly support the view that learners should be educated to be autonomous independent learners capable of continuing the process of learning even after leaving the classroom. The advantages of developing independent learning skills according to Dickinson (1987. are that students who might not be able to attend classes regularly may continue to progress; differences between students in aptitude, cognitive styles and learning strategies are accommodated, learner autonomy is promoted and requirements for continuing education (life-long learning) are satisfied, etc.

-

[8]

Brindley (1994) states that the aim of assessment is to ensure that information both of immediate value (formative assessment) and for later use (summative assessment) should be gathered through observation and recorded in a suitable form so that it can be understood by both the teacher and others.

Bibliography

- Adab, Beverly (2000): Evaluating Translation Competence. In: Christina Schäffner and Beverly Adab, eds. Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 215-228.

- Adab, Beverly (2005): Translating into a second language: Can we, should we? In: Gunilla Anderman and Margaret Rogers, eds. In and Out of English: For Better, for Worse? Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 227-241.

- Boud, David, Cohen, Ruth and Sampson, Jane, eds. (2001): Peer learning in Higher Education. London: Kogan Page.

- Brindley, Geoff P. (1984):Needs Analysis and Objective Setting in the Adult Migrant Education Program. Sydney: Adult Migrant Education Service.

- Brindley, Geoff P. (1989): Assessing Achievement in the Learner-centred Curriculum. Sydney: National Centre for English Language Teaching and Research, Macquarie University.

- Brindley, Geoff P. (1994): Task-centred assessment in language learning: The promise and the challenge. In: Norman Bird, Peter Falvey, Amy Tsuiet al., eds. Language and Learning: Papers Presented at the Annual International Language in Education Conference (Hong Kong, 1993). Hong Kong: Hong Kong Education Department, 73-94.

- Candlin, Christopher N. (1987): Toward task-based language learning. In: Christopher Candlin and Dermot Murphy, eds. Language Learning Tasks. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 5-22.

- Cruz, María M. (de la) (2004): Traducción inversa: una realidad. Trans. 8:53-60.

- Dickinson, Leslie (1987): Self-Instruction in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fox, Olivia (1995): Cross-cultural transfer in inverse translation: a case study. In: Marcel Thelen and Barbara Lewandowska, eds. Translation and Meaning, Part 3.Proceedings of the Maastricht session of the 2nd International Maastricht-Lodz Colloquium on Translation and Meaning. Maastricht: Hogeschule Press, 324-332.

- Fox, Olivia and Rodríguez-Inés, Patricia (2013): The Importance of Feedback in Fine-Tuning Syllabus Design in Specialised Translation Classes – A Case Study. In: Don Kiraly, Silvia Hansen-Schirra and Karin Maksymski, eds. New Prospects and Perspectives for Educating Language Mediators, Tubinger: Gunter Narr, 181-196.

- Galán-Mañas, Anabel and Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2010): Blended Learning in Translator Training Methodology and Results of an Empiric Validation. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 4(2):197-231.

- Gallego Hernández, Daniel (2014): A vueltas con la traducción inversa especializada en el ámbito profesional. Un estudio basado en encuestas. Trans. 18:229-238.

- Goodwin, Deborah and McLaren, Cristina (2003): La traducción inversa: una propuesta práctica. In: Dorothy Kelly, Anne Martin, Marie Louise Nobset al., eds. La direccionalidad en traducción e interpretación. Perspectivas teóricas, profesionales y didácticas. Granada: Atrio, 235-252.

- Hurtado albir, Amparo (2007) Competence-based curriculum design for training translators. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 1(2):163-195.

- Kelly, Dorothy, Martin, Anne, Nobs, Marie Louise et al., eds. (2003): La direccionalidad en traducción e interpretación: Perspectivas teóricas, profesionales y didácticas. Granada: Atrio.

- Kelly, Dorothy (2007): Translator Competence Contextualized. Translator Training in the Framework of Higher Education Reform: In Search of Alignment in Curricular Design. In: Dorothy Kenny and Kyongjoo Ryou, eds. Across Boundaries: International Perspectives on Translation Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 128-142.

- Lorenzo, María Pilar (2003): La traducción a una lengua extranjera: uno de los muchos desafíos de la competencia traductora. In: Dorothy Kelly, Anne Martin, Marie Louise Nobset al., eds. La direccionalidad en traducción e interpretación. Perspectivas teóricas, profesionales y didácticas. Granada: Atrio, 93-116.

- Nunan, David (1988a): The Learner-centred Curriculum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nunan, David (1988b): Syllabus design. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nunan, David (1989): Designing Tasks for the Communicative Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nunan, David, ed. (1992): Collaborative Language Learning and Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nunan, David (2004): Task based language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pacte (2014): First Results of PACTE Group’s Experimental Research on Translation Competence Acquisition: The Acquisition of Declarative Knowledge of Translation. MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación. Special issue 1:85-115.

- Pokorn, Nike K. (2005): Challenging the Traditional Axioms: Translation into a Non-mother Tongue. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Pokorn, Nike K. (2009): Natives or Non-natives? That Is the Question…: Teachers of Translation into Language B. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 3(2):189-208.

- Rodríguez-Inés, Patricia (2008): Uso de corpus electrónicos en la formación de traductores (inglés-español-inglés). Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- Rodríguez-Inés, Patricia (2014): Using Corpora for Awareness-raising Purposes in Translation, Especially into a Foreign Language (Spanish-English). Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 22(2):222-241.

- Rodríguez-Inés, Patricia and Fox, Olivia (2006): AVISO: cambio de aula… y de metodología de trabajo. Enseñanza de la traducción e interpretación. In: Marcos Cánovas, Josep M. Frigola, Richard Samson and Joan Solà, eds. Accessible Technologies in Translating and Interpreting [CD-ROM]. Vic: Universitat de Vic.

- Roiss, Silvia (2001): El mercado de la traducción inversa en España. Un estudio estadístico. Hermeneus. Revista de Traducción e Interpretación. 3:379-408.

- Römer, Ute and Arbor, Ann (2009): English in Academia: Does Nativeness Matter? Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies. 20(2):89-100.

- Stewart, Dominic (2008): Vocational translation training into a foreign language. Intralinea. 10. Visited on 23 September 2016, http://www.intralinea.org/archive/article/1646.

- Thelen, Marcel (2005): Translating into English as a non-native language: The Dutch connection. In: Gunilla Anderman and Margaret Rogers, eds. In and Out of English: For Better, for Worse? Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 242-255.

- Villa, Richard, Thousand, Jacqueline and Nevin, Ann (2008): A guide to co-teaching. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

- Way, Catherine (2008): Systematic Assessment of Translator Competence: In search of Achilles’ Heel. In: John Kearns, ed. Translator and Interpreter Training: Issues, Methods and Debates. London: Continuum, 88-103.

- Wimmer, Stefanie (2008): La traducción inversa en práctica, formación y teoría de la traducción. Master’s dissertation, unpublished. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- Zimmermann, Petra (2007): Misión (casi) imposible. La Traducción Especializada Inversa al alemán desde la mirada del alumno. In: Belén Santana, Silvia Roiss and Mª Ángeles Recio, eds. Puente entre dos mundos: Últimas tendencias en la investigación traductológica alemán-español. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 394-402.

List of figures

Figure 1

Copy-editing a text (modifications included)

Figure 2

Self-assessment questionnaire

Figure 3

Example of an estimate produced using WebBudget

Figure 4

Example of the translation of a webpage using WebBudget

Figure 5

Example of a student group’s translation of an extract from the Term Project text

Figure 6

Screenshot of concordances of “waiting period”

Figure 7

Screenshot of concordances of “payment holiday”

Figure 8

Screenshot of concordances of “month*”

Figure 9

Screenshot of concordances of “year*”

List of tables

Table 1

Competences to be developed and their indicators

Table 2

Evaluation questionnaire

Table 3

Template to assess group PowerPoint presentations