Abstracts

Abstract

This paper focuses on children’s picture books featuring same-sex couples in Anglophone and Francophone cultures, and more particularly in France and in the United States, with a particular interest in the censorship of these works. Censoring a book is common in the United States. This essay is a reflexion on the publication and reception of Francophone picture books on the topic – originals and translations. In this perspective, it also considers the question of the circulation of these books between the two cultures, as well as towards the two cultures respectively, Francophone picture books tending to be bolder in content than their Anglophone counterparts. Some references used to explain reception are gathered thanks to primary sources, in particular personal communications; others come from secondary sources, such as academic publications, blogs, and newspaper articles. This paper also explores the different forms of censorship, including the translation of a work from another culture or the alterations to the illustrations of an original work in an adaptation. The contrastive approach adopted reveals that, despite the growing number of picture books featuring same-sex couples, censorship is not only an American reality but a French reality as well.

Keywords:

- translation,

- adaptation,

- picture-books,

- same-sex relationship,

- censorship

Résumé

Cet article s’intéresse aux albums jeunesses représentant des couples homosexuels dans les cultures anglophone et francophones, et plus particulièrement en France et aux États-Unis, dans l’optique de la censure de ce type d’ouvrages. Celle-ci est chose commune aux États-Unis. Il s’agit de réfléchir à la publication et à la réception des albums francophones sur le sujet, originaux et traductions. Dans cette optique, il s’agit également de considérer la question de la circulation de ce type d’albums entre les deux cultures et vers chaque culture respectivement, les albums francophones tendant à être plus ouverts en termes de contenu que les albums anglophones. Les références sur la réception de ces ouvrages sont collectées par le biais de sources primaires, en particulier des échanges personnels ; d’autres références sont issues de sources secondaires, telles que des publications universitaires, des blogues et des articles de presse. Cette analyse explore aussi les différentes formes que peut prendre la censure, dont l’accueil d’une oeuvre d’une autre culture par le biais de la traduction, ou la modification des illustrations d’une oeuvre adaptée d’une autre culture. L’approche contrastive adoptée révèle que, malgré le nombre croissant d’albums représentant des couples homosexuels publiés, la censure frappe ces albums en France, comme aux États-Unis.

Mots-clés :

- traduction,

- adaptation,

- albums,

- relation homosexuelle,

- censure

Resumen

Este trabajo se enfoca en los libros de cuentos ilustrados con parejas del mismo sexo y su censura en culturas anglófonas y francófonas, particularmente en Francia y los Estados Unidos. Este ensayo refleja la publicación y recepción de los libros de cuentos ilustrados francófonos con este tema, originales y sus traducciones. Desde esta perspectiva también se considera la cuestión de la circulación de estos libros entre las dos culturas a la vez. Los libros francófonos son más audaces en cuanto al contenido que los libros anglófonos. Se recupera referencias que explican la recepción gracias a recursos primarios, en particular las comunicaciones personales; otros vienen de recursos secundarios, tal como las publicaciones académicas, los blogs y los artículos de periódicos. Este artículo también explora los diferentes tipos de la censura que incluye la traducciones del trabajo de otra cultura o las alteraciones a la las ilustraciones de un trabajo original en adaptación. Aunque la censura es más común en Estados Unidos, una aproximación de contrastes revela que a pesar del aumento de estos libros de cuentos ilustrados que presentan parejas del mismo sexo, la censura no es solamente una realidad americana sino una francesa también.

Palabras clave:

- traducción,

- adaptación,

- libro de cuentos ilustrado,

- relación homosexual,

- censura

Article body

Introduction

In February 2014, the association Bibliothèques en Seine-Saint-Denis – an association of libraries in the department of Seine-Saint-Denis, France – voiced its concern in an open letter published online about recent instances of censorship in the libraries of the department. Those took different forms, including the control of the new acquisitions made by some libraries.[1] In the wake of the “mariage pour tous” movement (same-sex marriage) in France, there were several attempts by various groups and individuals to censor several LGBTQ-themed children’s picture books, including a book adapted from the English,[2]Tango a deux papas, et pourquoi pas? The original US book, And Tango Makes Three, featuring the true story of two male penguins who became partners and raised a penguin chick in the Central Park Zoo, has been among the most frequently “challenged”[3] books in the United States in recent years.[4] If such “challenges” are not uncommon in the United States, they come as a surprise in a country like France. Topical as they may seem, their existence begs for further study within the more general context of the publication of LGBTQ literature for children both in France and in the United States.

The question is all the more interesting given that the discourse around picture books featuring same sex couples has gone from vocal to almost silent in France, raising the question of the current “visibility” of these books in the country. The topic, which made the headlines in France back in 2014 at the time of the controversy regarding mariage pour tous, has since then sunk into oblivion. Incidentally, in the French academia, the publication, reception and translation of these books in France is under-researched. To date, only a few academic studies have focused on the topic, in particular Minne’s (2013) and Coursaud’s (2003), but none of these studies address the issue of translation. The other sources of information available are mainly non-academic, such as blogs.[5],[6] This “gap” is all the more interesting as, in the last decade, Translation Studies in Anglophone cultures have recognized the importance of exploring the gender and queer politics of translation across multiple languages and cultural contexts (Larkosh 2011; Bermann and Porter 2014; Spurlin 2014a, 2014b; Epstein and Gillett 2017). This invisibility in the French academia serves as a reminder that more largely the theorizing and promotion of gay and lesbian visibility has met with resistance in France (Harvey 1998: 311; Revenin 2012; Bardou 2016[7]).

Turning to the concept of censorship, recent research in Translation Studies has brought out the multi-facetedness of the phenomenon (Ben-Ari 2010: 133; Billiani 2007), an aspect encapsulated in its vision as a continuum: censorship is seen as ranging from “extreme” or “overt” forms of censorship – institutionalized censorship being a case in point – to “more or less subtle” or “diluted” forms of censorship (Merkle, O’Sullivan, et al. 2010: 7; Billiani 2007: 3). Part of this complexity explains why Translation Studies have now slightly shifted their focus to incorporate occurrences of censorship not only in autocratic governments but also in liberal societies (Merkle 2002: 10), as is the case here. Billiani, when investigating censorship in light of translation practice speaks of the “polymorphous nature of censorship and its slipperiness when applied to translations” (Billiani 2007: 3, my emphasis). This derives from the different agents involved in the translation process – i.e the publisher, the translator, the proof-reader – and the time factor at play in the whole process – i.e the selection of the book by the target culture, its translation by the translator, its proof-reading by a third-party before publication. These are two key aspects at the core of the broad definition of censorship proposed by Merkle that serves as a basis for this study. In Merkle’s own terms, “[c]ensorship refers broadly to the suppression of information in the form of self-censorship, boycotting or official state censorship before the utterance occurs (preventive or prior censorship) or to punishment for having disseminated a message to the public (post-censorship, negative or repressive censorship)” (Merkle 2002: 9). In other words, censorship is more or less detectable, and is even more so when internalized in the form of self-censorship. This can make censorship almost impossible to locate, an idea Bourdieu made explicit by phrasing the term “invisible censorship” (Bourdieu 1996: 15). In such a situation, the subject matter of the source text and the political and cultural context of the target culture remain critical to illuminate the potential censored nature of a practice. Of great interest in this respect is then Tymoczko’s analysis of self-censorship as a manifestation of hegemony: “Through the mechanisms of hegemony, translators, for example, introject dominant interests and further dominant interests by means of their translations […]” (Tymoczko 2009: 31). Such considerations are key in the context of sexual minority politics that interests us here. One last point worth addressing regarding the analysis of censorship in the context of translation, is a lack of visibility of the link between the two. As remarked by Merkle, the term censorship “[…] is applied to both original texts and translations, although the distinction between the two is rarely made in the literature” (Merkle 2002: 9). To address this issue and give more visibility to censorship linked to the process of translation, I coined the term “translasorship” through lexical blending[8] and I use this neologism in this essay.

Given the slippery nature of translasorship, as underlined by Billiani (Billiani 2007: 3), prior censorship is explored here in light of the distinction Toury (Toury 2012: 82) makes between preliminary and operational norms of translation. Preventive translasorship can be operative through preliminary norms in the very process of selection of texts to be translated (Wolf 2002: 49). This includes cases when “the source culture may have initiated the transfer process but the transfer may not be accepted by the target culture” (Merkle 2010: 19). In such situations, there is a cultural blockage despite an attempt from a source agent – an author or a publisher, for instance – to import the cultural product. Because translations are costly to produce and the publishing market is driven by profit, presses are more reluctant to publish potentially controversial titles that are harder to sell, or in other words, works that “deviate most from target culture values” (Merkle 2010: 19). Once preliminary norms have allowed for a work to be selected for translation, operational norms can then be the locus of censorship. In the case of multisemiotic texts (i.e. comics and picture books), this can translate into the alteration of the imagery of the work (Oittinen 2004: 176). It should be mentioned that the term “translation” is used in this essay to refer to both interlingual and intersemiotic translation in Jakobson’s triadic system of translation (Jakobson 1959: 114). Further, in the perspective adopted here, illustrations fall under the broader category of intersemiotic translation.

The corpus under study is relevant in many respects when considering censorship. First, case studies of translation of gay-themed literary works have shown censorship often plays an important role in shaping the translation of such texts (Baer and Massardier-Kenney 2016: 87), with alterations ranging from deletion and substitution, to toning down gay thematics or adapting them (Tyulenev 2014). Second, when dealt with, translasorship or the circulation and translation of LGBTQ works is generally investigated in works of fiction for adults[9] and very seldom in literature for the youth.[10] Thirdly, the notion of censorship is crucial to the translation children’s literature (Klingberg 1986), in which adequacy prevails over accuracy (Shavit 1981: 171-172). When the target readers are children, the original work is often altered to better adjust to the literary, social, and moral standards of the target culture, and censorship is often motivated by a desire to protect the vulnerable (Merkle 2010: 19). Here lies the complexity of censorship when considering children’s literature: when does adaptation become censorship? And to what extent can the concept be applied to the filtering at stake in the process of translating children’s literature, so that it maintains its critical significance? These are questions raised by scholars (Merkle, O’Sullivan, et al. 2010: 14) to which this essay would like to contribute. A further dimension to consider when turning to picture books in particular is their visual qualities. Censorship needs to be investigated in relation to this specificity (Oittinen 2004: 176). It is true that because of financial constraints, multisemiotic texts tend to be co-produced in order to lower the cost of translation (Jobe 2004: 922); in that case, the visuals remain the same. But for adaptations, the visuals can be altered, which makes this worthy of attention. Equally important is the translation of the text into visuals.

In the same spirit as the very recently published Queer in translation (Epstein and Gillett 2017), this essay endeavours to “shed light on the manner in which heteronormative societies influence the selection, reading and translation of texts” (Epstein and Gillett 2017). Anchoring its reflection in the two domains of comparative studies and Translation Studies, this essay provides the basis for a more general reflexion on the publication and reception of LGBTQ-themed children’s picture books in French and in English – original texts and translations – over the years. As a contribution to this larger project, the present reflexion considers works similar to And Tango Makes Three in terms of topic, format, and target readers. The corpus therefore consists of the picture books featuring same-sex couples published in these two languages until now[11] for children up to the age of eight,[12] with a particular interest in the titles published by US or French presses. Picture books offer a solid basis for this study: they are one of the most published types of books for children (White 1998: 18; Milliot 2014[13]; Nikolajeva 2011: 406) and they are a sensitive issue in both cultures because of the age of their target readers.

The focus is on the reception and inclusion of this type of literature within the two cultures. And since children’s books published in France tend generally to take more risks in subject matter and illustrations than children’s books published in the United States (Pudlowski 2012; Dar 2015[14]), one of the questions is whether this is reflected in the production and publication in France of picture books such as And Tango Makes Three. The focus on the reception of the corpus is tied to the exploration of the different forms of censorship at play in the publication of those books in France, be they originals or translations. More generally, the essay interrogates the notion of censorship by locating certain cultural or literary practices in the context in which they occurred; among those practices, the extent to which a culture is open to translating certain texts (Toury 2012: 82) or the alteration of the visuals of a multisemiotic text in an adaptation.

As a starting point, the analysis charts the production and publication of the corpus in the Francophone and Anglophone cultures. After this contrastive analysis, the reception of those works in France is analysed, highlighting the different forms censorship took. A “mixed” approach is used to collect the references explaining reception: some are gathered thanks to primary sources, in particular personal communications; others come from secondary sources, such as academic publications, blogs, and newspaper articles. The challenges received by the corpus in France leads us to concentrate on one work in particular in the French culture: Tango a deux papas et pourquoi pas?, that can be considered an adaptation of And Tango Makes Three. The focus is mainly on the alteration of visuals that leads to the silencing of the homosexual relationship between the two male penguins present in the original text. Such a discussion is linked to the more general reflexion on the boundaries of the notion of censorship.

Picture Books Featuring Same-Sex Couples in the Anglophone and Francophone Worlds

The corpus – i.e. original texts and translations in French and in English – is analyzed in order to discover discernible patterns in terms of timeline of publication, number of books published, targeted readership, but also in terms of storyline and characterization. First I address similarities and then focus on the noticeable differences.

In both Anglophone and Francophone cultures, publishers, journalists and academics lament the scarcity of inclusive picture books available for young readers and more particularly picture books featuring same-sex couples. In June of 2013, Kisby (2013:151), a senior lecturer in English Education, stressed the paucity of picture books challenging conventions and offering a representation of diverse families for young readers. A French journalist drew the same conclusion about France in an article published in February 2014: “Out of 70, 000 titles published in France, most picture books feature ‘idyllic’ families: a mum + a dad + (a) kid(s) […] too few picture books present different types of families – families headed by single parents, same-sex parents, families without kids or blended families” (my translation).[15] This should nevertheless not come as a surprise in both cultures, given the persistence of the myth of the idyllic family, typically portrayed in works for children and adults (Alston 2008; Coontz 1992).

Nonetheless, in recent years, both cultures have seen the emergence of more inclusive types of picture books, notably as regards the composition of the nuclear family and same-sex parenting. Hall (2002: 150) draws our attention to this phenomenon in the United States. As far as France is concerned, Minne speaks of “a growing acceptance of the theme in children’s literature” (Minne 2013: 87, my translation). This idea is echoed by the owner of a bookstore in Bordeaux (see note 11), France, who nevertheless qualifies this statement by making clear that overall the increase has been insignificant and is mostly due to a few publishers trying to capitalize on the passing of the law on same-sex marriage.[16]

From a synchronic perspective, the number of picture books featuring same-sex couples published in English in Anglophone countries is indeed small compared to the total number of picture books published in the same language, with around only fifty titles (Sunderland and McGlashan 2012: 190). The same remark applies to the number of picture books with the same topic published in French in Francophone cultures as compared to the total number of picture books available in French, with only twenty or so books. Thus, overall the number of books on the topic is insignificant in either language. Rare as these picture books may be, a pattern does emerge in terms of their countries of origin in both cultures: among Anglophone cultures, mainly US publishers have been publishing such books, and among Francophone cultures, mainly French publishers have.

Among these books, the number of translated picture books into French or into English is also remarkably low in both cultures. Both suffer a “translation deficit,” as evidenced by Table 1 and 2 below; the possible rationale behind this deficit is addressed in the next section. What the two tables show is first that the United Kingdom imported the first foreign picture book on the topic with Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, a translation from Danish undertaken by a small and specialized press, Gay Men’s Press, in 1983 (Table 1); second, that the United States and France imported such books only recently, that is after the new millennium. Tricycle Press, a small American press that sought out “books outside the mainstream; books that encourage children to look at the world from a different angle” (Pope qtd in Heffernan 2007: 50) published King & King in 2003. And the fast-growing French publisher Auzou, which has only recently specialized in juvenile literature, published the translation into French of a picture book from New Zealand, Milly Molly and Different Dads one year later, in 2004; more recently, in 2014, Auzou translated one of its own French title Camille veut une nouvelle famille into English.

Table 1

Picture books featuring same-sex couples translated from language X into English

Table 2

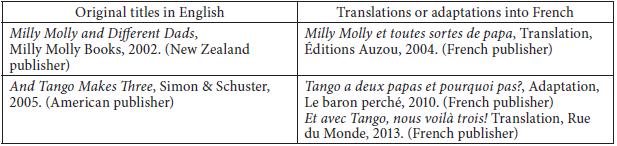

Picture books featuring same-sex couples translated or adapted from English into French[9]

In spite of the very scarce number of translations, the results are significant in several respects, if analyzed in light of one general tendency: English-speaking countries have always translated fewer books than other countries, including children’s books.[18] The tendency has always been towards a higher number of books translated from English in non-English-speaking European countries (Pym 2015: 5),[19] even in bilingual countries like Canada (Cobban 2006: 7). The reason for this asymmetry is mainly cultural.[20] To be more specific, the US children’s book industry is rather reluctant to import what Yokota calls “wild books” (cited in Dar 2015). By “wild,” Yokota means titles that are innovative and daring in terms of narrative and illustrations (Dar 2015). “Innovative” and “daring” are two terms that can indeed qualify French-Canadian and French picture books, which tend to take more risks in subject matter and illustrations than the books published in Anglophone countries (Cobban 2006: 11; Dar 2015; Pudlowski 2012). Thus, unsurprisingly, the United Kingdom and the United States imported one and only one title featuring a same-sex couple respectively. What is more surprising and worth noting is that France – and French-Canada incidentally – for which the translation of books from English plays a prominent role in the publishing industry, did not import this particular type of picture book. Thus, picture books featuring same-sex couples do not travel well between France and the United States in either direction.

The books on the topic in the two cultures, scarce as their number may be, share another interesting characteristic when it comes to the audience they target: when consulting several reliable sources, one realizes that there are discrepancies in the age recommended for the same reference. This variation in the age recommendations is proof of the challenge the question of age appropriateness for these books poses in each culture and between cultures. The discrepancies also betray the conservative outlook sometimes adopted on the question. Tables 3 and 4 below[21] feature a handful of books of the corpus that have been selected because they are representative of the discrepancies just mentioned. When they feature the recommended age, the sources do sometimes provide the same age as a reference, as is the case, for instance, for Et avec Tango, nous voilà trois!, Milly Molly et toutes sortes de papa or Mommy, Mama and Me. But there are times when there is a conflict between the ages recommended for the same work. This is illustrated by Jean a deux mamans or And Tango Makes Three, recommended for pre-school versus primary school children depending on the source selected. There are also cases when a different edition of the same work recommends another audience for it. The age may vary depending on the date of publication, as it the case for the French Ulysse and Alice; the age may also vary for the same language depending on the publisher’s country, as shown for Milly, Molly and Different Dads. Noticeable also are the discrepancies existing between the original and its translation. This is the case, for instance, for the New Zealand Milly, Molly and Different Dads and the French Milly, Molly et toutes sortes de papas. The source text was intended for children aged 4-8, as mentioned at the back of the book. The translation in French, on the other hand, bears no age recommendation and the age target mentioned varies depending on the sources consulted: Memento recommends it for children aged 3 and up and WorldCat for children in primary and secondary school.

Table 3

Recommended audiences for picture books featuring same-sex couples in French

Table 4

Recommended audiences for picture books featuring same-sex couples in English

One last notable feature shared by the Anglophone and Francophone picture books of the corpus concerns their characterization, which places same-sex couples at the centre of the plot and upholds homonormativity. First, the same-sex couples represented in these stories are generally the main protagonists and the story revolves around them (Crisp 2010: 95). Only two exceptions can be found in the Francophone corpus: the French-Canadian Ulysse et Alice (2006), and the more recent French Le Voyage de June (2015). In both picture books, the main focus of the story is not the same-sex couple. The fact that characters are lesbians is incidental to the story, as a way of showing that same-sex relationships are part of life and do not deserve more attention than other types of relationships. The other shared characteristic of the books in the two cultures is their adherence to the homonormative subject. Let us consider the tree aspects Lester investigates in her LGBTQ-themed Anglophone corpus in this respect: “gender conformity, reproduction/parenting, White supremacy and middle-class normativity” (Lester 2014: 247). Very noticeable is indeed the predilection of the books of our corpus in both languages for “depicting predominantly middle-class white households […]”[22] (Minne 2013: 96, my emphasis, my translation). Minne (2013: 93) points to the small number of Anglophone picture books featuring interracial couples, a tendency that also holds true for picture books in French. Interracial couples can be said to be non-existent, with the exception of the Quebec Ulysse et Alice and the French La Princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes. Furthermore, except for the very recent French Canadian Ils sont…, telling the story of two old men united by a life-long love, all the picture books in French exclude families without children. Lastly, most of the books of the corpus in French fall prey to a tendency pointed out by Lester in her Anglophone corpus: gender conformity or “gender presentations that are less threatening to hegemonic discourse, that is, gender presentations that mimic those associated with heterosexuality” (Lester 2014: 250). This tendency Lester identified in portrayals that favour gender binarism or normative prescriptions of femininity (2014: 250), applies to our corpus in French. In terms of the representations of femininity, Lester pointed to two tendencies: “either both women are drawn as feminine or one of them is feminine and the other is more masculine” (Lester 2014: 251), compared to two less feminine representations. La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes, Jean a deux mamans or Cristelle et Crioline illustrate the first tendency; Dis… mamanS, the second. Gender binarism is another manifestation of gender conformity. The perfect example is Jean a deux mamans, which conforms to prescribed gender roles, despite its groundbreaking aspects.[23] In the same way, the two bulls in Camille veut une nouvelle famille are “heterosexualised”: Roger is cooking, while Bastien, depicted as the “strongest bull,” is waiting for the meal to be served at the table. Le voyage de June and Ulysse et Alice stands out in both respects.

These picture books also have their own specificities, especially in terms of their timeline of publication, and of their storyline and characterization. First a major difference concerns their time of publication: the Francophone world was slower to bridge the gap between fiction and “lived experiences” in society. Hall refers to the publication of picture books in English depicting same-sex parents “in recent years” (Hall 2002: 150). This means in reality, the late 70s in the United States, for the first picture book featuring a same-sex couple published in English, with Jane Severance’s When Megan Went Away (1979). The very first picture book presenting a same-sex family among different types of families was Drescher’s My Family, Your Family, published one year later, in 1980. In fact, the term “recent years” is more accurate for the titles published in France or in Québec. Evidently, no picture book featuring homosexual or lesbian couples targeting the age group selected were published there or in any Francophone country prior to 1999. The first picture book presenting a line-up of different families in French, L’heure des parents, was published in November 1999, the same year the PaCS (Civil partnership for same-sex couples) was adopted in France, and the first story featuring a same-sex couple, Marius, was published in 2001.[24] Both were published in France at a time when LGBTQ theories and queer studies were beginning to find their way into the French academia under transatlantic influences (Bardou 2016). The very first picture book on the topic published in French in Canada, Ulysse et Alice, dates back to 2006. This is one point of convergence among many others between the French-Canadian children’s book industry and the European French children’s book industry.[25]

The second major difference between picture books featuring same-sex couples in the two cultures concerns some aspects of their storyline and characterization. This is somewhat revealing of the more general approach each culture adopts towards the topic. Most US picture books of the corpus “do not fall into an imaginative fictional mode […] and operate under the rubric ‘this is my life’” (Mitchell 2000: 117). In the picture books published in France or in French, the way the narrative mode tends to be less direct, either because the story resorts to the fairy-tale topos or because it features animal characters. La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes by Alice Brière-Haquet, Cristelle et Crioline by Muriel Douru, or the more recent Heu-reux by Christian Voltz, are good illustrations of this tendency. The only existing picture book published in English with the motif of the fairy tale is King & King, which is a translation, and can therefore be seen as a “niche” product. As for stories on the topic featuring animal characters, this is the rule rather than the exception in French.[26] In contrast, the US picture books dealing with same-sex couples very rarely feature animal characters. Three exceptions can be pinpointed: Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, featuring guinea pigs, And Tango Makes Three, inspired from a real-life situation involving penguins, and Henry Searches for the Perfect Family, a translation undertaken by a French publisher. Therefore, only one of the works authored in the United States featured anthropomorphized animals originally. And yet this type of characterization is very common in picture books in either language, as it helps children under ten relate to the story and its characters (Danset-Léger 1988: 73; Friedman 2011: 6). Most crucially, anthropomorphizing animals is also a means to “soften the didactic tone and ease the tensions raised by dealing with issues not yet fully resolved or socially controversial” (Burke and Copenhaver 2004: 210), which is significant when one knows that the representation of same-sex couples in picture books is still a controversial topic for some people in France. This goes hand in hand with Shimanoff’s remark that, in And Tango Makes Three, “[t]he fact that Roy and Silo are animals rather than humans, may make their nonnormative, same-sex attraction more marketable” (Shimanoff 2012: 1012). Therefore, the picture books published in France we are considering here are generally more conservative in their characterization than the US picture books. This may explain the “translation deficit” noted for picture books on the topic in the direction United States-France. We will come back to that.

The comparative approach presented here reveals that France is as conservative as the United States with regard to the production and publication of the picture books of the corpus. Several aspects point to this idea: the very recent publication of those books, the scarce number of books available, the translation deficit that affects the books despite an obvious need for such titles in the French culture, the choice of characterization made in the stories. Despite that, a handful of picture books featuring same-sex couples have been published in France over the last few years. And yet, as the reception of these books is not unproblematic, it is important to contextualize the production and publication of those picture books, originals and translations, and their reception in France. In particular, we need to investigate the different forms of censorship these books have experienced, including the phenomenon of non-translation.

Censorships[27] somewhere over the “French” rainbow[28]?

Banning books, the most visible form of censorship, is not uncommon in the United States, where “larger-scale censorship efforts” (Casement 2002: 206) have actually led to the creation of a “banned books” week. But censorship is not solely a US reality, as shown by the title of an online article published at the time of the controversy on same-sex marriage in France: “Controversy Over Children’s Content is New in France […]”.[29] Albeit on a smaller scale and therefore with less visibility, the books of the corpus selected for this essay were and are still the targets of censorship. But what do we mean by censorship? Banning books is in fact just the tip of the iceberg. The definition of censorship proposed here draws partly on Merkle’s (Merkle 2002: 9). Prior or preventive censorship refers therefore to the suppression of information in the form of self-censorship before the utterance occurs. I would like to point out the dual nature of the term “utterance,” which can refer to the written or the oral, which is key when considering theatrical adaptations of original works. Post-censorship refers to retaliatory actions for having disseminated a message to the public. Prior censorship or post censorship can affect original, translated or adapted works alike.

Next are presented the occurrences of censorship that had an impact on the works of the corpus in French: first, the forms of censorship that affected both original and translated titles, second, those that were specific to works that are translation, or translasorship. The classification follows the prior-post-utterance typology proposed by Merkle and draws on the Tourean terminology of preliminary and operational norms. Censorship prior to publication did affect the texts of the corpus, both in the case of original and translated titles, in the form of self-censorship. This internalized form of censorship was the result of all the pressures exerted on librarians, authors, publishers, and academics that was meant to limit the access of children to picture books featuring same-sex couples. Thierry Magnier,[30] who is a publisher for three French presses, Actes Sud Junior, Le Rouergue, and Les éditions Thierry Magnier, voiced his concern, explaining how some teachers and librarians gave in to the pressures exercised by some parents or some radical groups and consequently stopped ordering books with LGBTQ content. Thierry Magnier himself was the victim of pressure on the part of some readers who wrote derogatory letters to his publishing house. Marie Moinard (2015), the publisher of Mes deux papas, had a similar experience. Nonetheless, both publishers, being firm believers in the principle of the freedom of speech and in the cultural value of what they do, refused to give in to self-censorship. Self-censorship also occurred with booksellers during the critical stage of the promotion of the books by publishers. Moinard (2015) explained that Mes deux papas faced such a setback: the work did not receive a very warm welcome from booksellers, which considerably reduced its visibility and certainly had a negative impact on its sales to professionals.

Censorship posterior to publication – by radical groups, politicians or individuals – also had an impact on some of the books of the corpus, be they translations or originals. On the one hand, radical groups or politicians demanded the removal of some picture books already acquired by public libraries. That was the case for Jean a deux mamans in 2005, when Edwige Antier, a renowned pediatrician, attacked the book in Le Figaro Magazine and declared that only parents have the right to make the “marginal” ideas it conveys accessible to their children, not public libraries or local councils.[31] Similarly, in February 2014, while the marriage pour tous campaign was at its peak, a far right-wing group called “Printemps français” went around public libraries putting together lists of books that they defined as immoral and asking for those books to be removed from the shelves. Among those books were Tango a deux papas et pourquoi pas?, La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes and Mes deux papas. This call for censorship was backed by Philippe Brillault, the mayor of a Parisian suburb. Brillault, an opponent of gay marriage, ordered Tango a deux papas, along with other titles, to be moved from the children’s section to the adult’s section.[32] One cannot but notice the impromptu reaction of far-right counter discourses: some of the books targeted, such as Jean a deux mamans (2005) or Tango a deux papas, et pourquoi pas? (2010), had long been available in bookshops and libraries.

Some individuals also took concrete steps to restrict children’s access to the books that had already been acquired by libraries or were being offered for sale in bookshops. For instance, some people would borrow books from libraries but not return them; others would tear books apart in bookshops or steal them, something that happened to Mes deux papas (Moinard 2015). Furthermore, some librarians pulled the books off the shelves in the children’s section to put them in the adult’s section or in a section the public did not have access to (see note 30). In a similar vein, but in a different spirit, in library catalogues, some books are still recommended for an older audience than the one intended originally. For instance, the public library in Lyons, France, recommends Milly, Molly et toutes sortes de papas for children aged 6-10,[33] while Memento recommends it for children aged 3 and up, WorldCat for children in primary and secondary school, and the original publisher for children aged 4-8. As for the books that were not yet on the shelves, some censors were ready to deprive public libraries of the right to acquire them: in March 2014, a right-wing municipal candidate, Franck Margain, declared his opposition to the acquisition of picture books dealing with same-sex parenting by public libraries in Paris (see note 27).

When it comes to translated titles in particular, prior censorship was linked to the preliminary norms of translation, that is the selection process. Two key elements should be taken into account when considering “non-selection” before addressing the controversy linked to the books of the corpus: the “quality” of those books and the role of awards, two elements that are not unrelated. It is true that the quality of some of the earliest US picture books of the corpus or their content appropriateness (see Chick 2008: 17) on the first edition of Heather Has Two Mommies) may have played a role in the translation deficit highlighted. Nevertheless, high-quality US titles were produced over time (Mitchell 2000; Rowell 2007; Chick 2008: 17-18) that were not selected for translation either. Likewise, the lack of visibility of the books of the corpus in terms of awards may have played a part in the translation deficit, awards helping books “get attention for international publication” (Yokota 2011: 473). It is indeed only very recently that awards have been created to identify and celebrate the best LGBTQ works. Awards, when they exist in the Francophone literary landscape, are nonetheless not as prestigious or “comprehensive” in their categories as the US Lambda Literary Awards, which feature a “Children’s/Young Adult” category: no literary LGBTQ award exists for now in Canada; in France, one award, with a somewhat limited visibility, celebrates the best French gay novels; the award is given on an annual basis by Les éditions du frigo. That being said, one may still wonder to what extent the “national and international media attention”[34] prestigious awards such as the Lammys bring to the works nominated, helps cross-cultural communication? Indeed, while several of Leslea Newman’s picture books featuring same-sex couples were Lambda finalists, none has been translated into French so far.[35] Aside from those considerations and their potential role in the selection process, one must also acknowledge the negative impact of controversy. Controversy made the books of the corpus a sensitive issue in France and can also explain the rather lengthy time gap for France to import even a few Anglophone titles. As already noted, the handful of picture books featuring same-sex couples – either as part of a line-up of families or as central characters – originally published by French presses appeared in the new millennium. Hence the timeline of publication of the translations, with Milly, Molly et toutes sortes de papas (2002/2004) and Tango a deux papas et pourquoi pas? (2010). The selection conforms to the already-existing repertoire of texts published in French then, certainly as a way to ensure that the books will appeal to the readers and will therefore be more marketable. One presents a line-up of families, the other, a real story featuring animals. This also explains why the first picture book featuring same-sex parents translated in 1983 in the United Kingdom was published by a forward-thinking publisher – Gay men’s press.

Cultural blockage, also in the form of prior censorship, occurred despite attempts by source agents to initiate the transfer of the original text. In other words, finding a publisher in the French culture proved challenging for some authors.[36] For instance, Linda De Haan and Stern Nijland, two Dutch authors who exported their picture book Koning & Koning into the US, have been trying to initiate the transfer process of the book into France for several years (Haan and Nijland 2015). The author and the illustrator shared that French publishers “had shown no interest in their project” (Haan and Nijland 2015) despite their flexibility. As the artwork can be a hindrance to having a picture book imported into another culture since tastes may differ between cultures (Tomlinson 1998: 19), the authors have been considering “altering the original illustrations of the book” (Haan and Nijland 2015). Koning & Koning has indeed a very distinct artwork, which may explain its being selected as “the most unusual book of the year,” “honorable mention,” in the 2002 annual “Off the Cuff awards”[37] published by Publishers Weekly. The question of censorship is all the more relevant here as the book has been successful in many other countries over the past few years. Koning & Koning has been translated into nine different languages so far, chronologically: Frisian (2000), German (2000), Danish (2000), English (2002), Spanish (2004), Catalonian (2004), Polish (2010), Czech (2013) and Japanese (2015). The picture book was also adapted for the stage by the Mexican playwright, Szuchmacher, in 2009 (Water 2012: 72). And in the United States, Tricycle Press, which imported the book in 2003, asked its authors to write a sequel to it in order to publish the work in English; that’s how King & King & Family was born. Further, the US King & King received several awards (Naidoo 2012: 101) and was favourably reviewed by several highly regarded reviewers (Sova 2006: 198), which is a sign that the book is worthy of international publication.

Occurrences of censorship prior to the “utterance” also had an impact on intersemiotic translations. Both the adaptation of a text into a theatrical performance and into visual artwork, that is illustrations, are considered here in relation to displays of affection between same-sex couples, in particular a kiss. In the following examples, “translating” a kiss between a same-sex couple, either by way of acting or by way of illustrations appears to be problematic. A little bit of context is necessary before we move on to the two examples. Generally speaking, displays of affections between same-sex couples in picture books have been a bone of contention in the United States; one can think, for instance, of the representation of the two kings exchanging a kiss at the end of King & King and the controversy it triggered, despite the kiss being hidden behind a heart. The French picture book La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes resorts to the same “indirect” technique of representation: the text makes clear the two princesses kiss and this is translated into the illustrations by their posture and by the heart drawn above their heads. And yet, the motif of the kiss is a staple of the genre of the fairy tale. This suggests that showing two princesses or two princes exchanging a kiss is more problematic than showing a prince and a princess. It is true that in more realistic stories featuring a family and a couple as parents, be they heterosexual or homosexual, age-appropriateness raises the question of “how physical and intimate […] the contact [can] be” (Sunderland 2012: 155). We are in a context where physical contact between parents was and still is not traditionally shown in children’s picture books (Women on Words and Images Society 1975: 35; Sunderland 2012: 155). In such a perspective, suggesting a kiss between two parents of the same sex in the visuals can be analyzed as a way of addressing the concern of age appropriateness.

The two examples selected to illustrate censorship prior to the “utterance” are both linked to the “non-representation” of a kiss exchanged between a same-sex couple in an adaptation of a text into two different systems: an adaptation into a play or into visuals. The first example is the cancellation in March of 2014 of the theatrical performance of La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes by the theatrical company La môme perchée because of a decision by the city council where the play was supposed to be running.[38] Since then, the company has had difficulty finding venues to perform the play, compared to the other theatrical performances the company offers. In particular, schools or media libraries have been reluctant to host the play (Orléach 2016). Orléach, who is part of the company, explained (2016) that now she is in charge of the promotion of the play she can sense a certain feeling of uneasiness when her interlocutors understand that the story involves a princess kissing another princess. This may explain the reluctance the French play has met with, despite the company’s effort to guarantee age appropriateness. This may also explain why the recent adaptation of And Tango makes Three, Ryo Silo Tango by the French company La Pierre et le Tapis (2016) was rather well received by the French public. The theatrical performance does not involve such displays of affections between the two male penguins. In that, the play remains faithful to the French adaptation (La Pierre et le Tapis 2016). The second example of “non-representation” is linked to the translation of a text into visuals. In Le voyage de June, the text explicitly refers to June’s mums exchanging a kiss at the end of the story, but the illustrations show a shoulder embrace instead. This choice of an “asymmetrical” interaction between word and picture (drawing on Nikolajeva and Scott’s “symmetrical interaction” (2000: 225)) leaves one wondering. First, in light of the choice made of a symmetrical interaction between text and image in the same scene for the hug June gives her grandfather; second, when analyzing this choice against the more general backdrop outlined here: the uneasiness surrounding the representation of a kiss between two people of the same sex. The suggestion of a kiss was still a possibility if age appropriateness was a concern.

As we have seen here, the same story could experience different types of censorship at different stagesof the process of publication – and the longer the process, in the case of translations, the more forms of censorship the book was potentially exposed to – but also afterthe process of publication, when the work was published, including when the work was adapted. The previous sections have also set the background against which the work selected for analysis in the next section, Tango a deux papas et pourquoi pas?, was published in France. The reason for choosing this particular work is that according to Santaemilia “[…] media groups, political parties, religious institutions and a large number of pressure groups favour predictable and unpredictable forms of self-censorship […]” (Santaemilia 2008: 223, my emphasis). The context in which this adaptation was published illuminates choices that were made concerning the representation of a same-sex couple. The next section therefore explores those choices. By comparing key passages of the adaptation, my case study argues that the French adaptation of the picture book downplays and therefore silences the homosexual relationship between the two penguins, Roy and Silo. Illustrations prove to be of particular interest in this contrastive approach.

A case study: And Tango Makes Three, Tango a deux papas et pourquoi pas? and Et avec Tango nous voilà trois

And Tango Makes Three was published originally in the United States by Simon and Schuster in 2005. It is based on a true story of two Central Park Zoo penguins, Roy and Silo, who hatched and raised a female chick, Tango. It was first introduced in France as Tango a deux papas et pourquoi pas? by Le baron perché in 2010 and then as Et avec Tango nous voilà trois, by Rue du Monde, in 2013. As explained previously, and as suggested by the two titles, Rue du Monde translated the original text, while Le baron perché proposed an adaptation of the work. As an adaptation, the French picture book offers insight into the culture that adapted it, while the context in which the work was adapted offers valuable information to decode the choices that were made in the adaptation in terms of the topic that interests us. In a word, the conservatism that is observed around picture books depicting same-sex couples in France and the instances of censorship already pinpointed give credit to the idea that, compared to the original work, the adaptation downplays the homosexual relationship between the two male penguins.

Although the larger context of publication of such picture books in France was presented in the previous section, we turn now to the context of publication of the adaptation and the translation of And Tango Makes Three in France. One cannot help but notice the lengthy time gap between its original publication in the United States, 2005, and its publications in France, respectively 2010 and 2013; the larger context of publication therefore raises the question of invisible censorship. This lengthy time gap is all the more surprising as the book did get “the attention for international publication and translation” mentioned by Yokota (Yokota 2011: 473). And Tango Makes Three was indeed the recipient of several prestigious awards in the United States and in Great Britain in 2005 and 2006 (Worldcat 2016).[39] An award attracts publishers’ attention as “[it] gives the book a distinguished pedigree” (Yokota 2011: 473). A “pedigree” that, in the case of And Tango Makes Three, was also recognized in scholarship. Young, for instance, demonstrated in his doctoral dissertation how the picture book functions as “a high-quality work of queer multicultural children’s literature” (Young 2010: 4). The work gained visibility not only because of its literary merit but also, unfortunately, because of the number of challenges it received in the United States for three years in a row, from 2006-2008 (see note 3), which is more than any other book during those three years. All this must have played a role in the publication of the adaptation in France in 2010. It should nevertheless be noted that Rue du Monde produced the translation of And Tango Makes Three in 2013, at the same time as the same-sex marriage debate, not knowing that an adaptation of the book already existed on the French market (Serres 2016).

When it comes to the choices made in the adaptation in terms of perspective, text, and visuals, the same question of invisible censorship resurfaces. Indeed, the original And Tango Makes Three is not only about two male penguins parenting a chick but also about the homosexual relationship between Roy and Silo. By contrast, the French adaptation silences this relationship in all those respects. The story concentrates instead on the parenting aspect of the tale, while also adopting a more educational perspective.[40] This difference in orientation – a more or less “frontal” representation of homosexuality – is more generally visible in the perspective adopted in each work, in terms of its artwork and narrative strategy. Minne (2013: 98) remarked that the original visuals offer a more “frontal” view of the story, with eye level shots to present it, while the adaptation oscillates between low-angle shots and high-angle shots. In keeping with this idea of a less “frontal” outlook in the adaptation is the change from an omniscient narrator in the original version to a first-person narrator, with a little boy telling the story in the adaptation and sharing it with his mother.

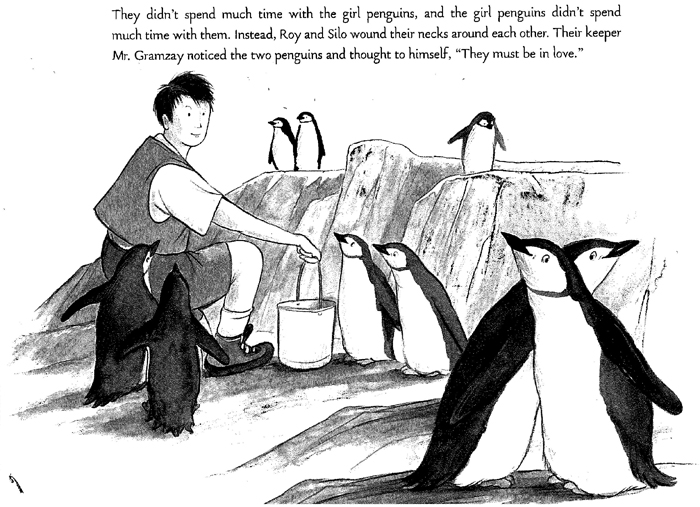

Thus, in the original picture book, the two penguins are humanized and the homosexual relationship is not only foregrounded in the illustrations of the work but also in the text, even if less so than in the illustrations. This is not the case in the adaptation. Let us first examine two key corresponding passages from both texts before concentrating on the visuals, where the difference is thus even more glaring. In the original text, at the beginning of the story, the two male penguins are depicted “w[inding] their necks around each other” (Richardson and Parnell 2005: 9). Further, in a way that is reminiscent of anthropomorphized animal documentaries as analyzed by Mills (2012), the keeper makes sense of their relationship in human terms, making the comment that the penguins “must be in love” (Figure 1).

At this point in the story in the original text, readers already know that the two penguins are males. In the corresponding passage in the adaptation, there is also the mention of Roy and Silo “snuggling together” (Richardson and Parnell 2010: 10), and even though the penguins’ gender is mentioned, it is only a couple of pages later. This somewhat dilutes the message of the original text. Further “dilution” occurs in that very same passage because of the perspective adopted, which is more anthropological than in the original work: the text indeed harnesses the narrative into the animal world by referring to the “mating season” (Richardson and Parnell 2010: 9) and to the “courtship dance” (Richardson and Parnell 2010: 9). To this can be added the use of the term “couple” in both works. In the original work, the word is used throughout the book to refer to the heterosexual relation between other penguins, but it is used in the author’s note at the end of the book to identify Roy and Silo’s relationship, putting both types of relations on a par. In the adaptation, the term “couple” is always used to refer to the heterosexual penguins of the story, including on the back cover of the work, where Roy and Silo’s relationship is again identified through an anthropological lens, with the term “mating season.”

Figure 1

The same difference in orientation applies to the artwork of the two books: the illustrations of the adaptation focus on the family unit, while the original text also gives pride of place to Roy and Silo’s relationship. The importance of the love uniting the two penguins is not only highlighted in the illustrations per se but also in the place they occupy in the overall composition of the book. With regard to the visuals, this is made visible in two types of representations in the original text: those depicting the family unit and those depicting the couple. When represented snuggling together with Tango, as a family, the original illustrations always foreground the complicity between the two male penguins, not only through the way they look at each other but also through their posture. By contrast, the visuals in the adaptation focus on the family unit and on Tango. Two passages from each book show evidence of this. First, the book covers of the two editions (Figures 2 and 3).

In the US edition (Figure 2), the bodies of the male penguins touch and Roy and Silo look at each other in a very loving way. In the French edition (Figure 3), the penguins are focused on Tango and are wide apart in a very symmetrical representation; the bodies and beaks of the penguins point towards the chick as the focal point of the scene. The penguins are less visible as a result, part of their bodies incidentally being cut off from the frame. The scene’s focus is on parental care. A second example is the last representation of the three penguins as a family (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 2

Figure 3

In the original work (Figure 4), the eyes of the two penguins are closed, showing they are relaxed and that they enjoy tactile affection. Further, in some sort of inverted image of the cover of the adaptation (Figure 3), Tango looks at them sharing this intimate moment: they are the centre of attention. In the adaptation (Figure 5), Tango is the centre of attention: in the final representation of the family, the penguins both look at Tango. The illustration reinforces this idea of parental warmth and care, not only because Tango is still very young, but also technically through the very symbiotic distribution of the colours and the body arrangement. Moreover, in the original version, when represented “winding their necks around each other” (Richardson and Parnell 2005: 9) without Tango by their side, the two male penguins are shown enjoying physical contact: the expression of content is mimicked by their pupils: one penguin can be seen closing his eye (Figure 6).

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

When shown snuggling together in the adaptation, the penguins do not appear to enjoy physical contact, the penguins’ eyes lacking expressiveness (Figure 7).

Figure 7

With regard to the place and placement of these illustrations, the same conclusion can be drawn: the original work gives visibility to Roy and Silo’s relationship, while the adaptation reduces its visibility. In terms of placement, the representations featuring displays of affection between the two male penguins appear in key passages in the original, that is not only in the story, but also in two paratextual passages: on the book cover, with Tango by their side (Figure 2), and on the title page, without Tango (Figure 6). This is not retained in the adaptation: as mentioned previously, the two penguins both look at Tango on the front cover (Figure 3); as for the title page, it features rocks instead of the male penguins. If the two penguins are indeed depicted together on the front endpapers and the back endpapers of the adaptation, which is not the case in the original text, none of these representations actually involves a display of affection between the two male penguins (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8

Figure 9

This reduced visibility of Roy and Silo’s homosexual relationship in the adaptation is also clear with regard to the place given to the illustrations depicting the two penguins snuggling in the whole work. This representation is “confined” to half a page in the adaptation (Figure 7), while this is a recurring image in the original version (Figures 1, 2, 4 and 6).

Therefore, overall, the adaptation can be said to dilute the gay overtones of the original text. In this light, Tymoczko’s remark that translators can sometimes “reframe[d] translations and suppl[y] an alternate place of enunciation, so as to package subversive texts and ideas in ways that are difficult for the censor to object to” (Tymoczko 2009: 26) is very meaningful. Not only does the adaptation literally “reframe” the US original through the change in narrative point, but it also shifts part of the intended message of the original. The back cover of the French text clearly mentions the primary function of the French text: “a pretext to talk about same-sex parenting” (my translation). The relationship between text and image is therefore symmetrical in this endeavor. Interestingly enough, the new “frame” is reminiscent of a somewhat stereotypical representation of parents, as highlighted by the Women on Words and Images Society in 1975 about heterosexual couples featured in children’s books. The society had then come to the conclusion that in the readers analyzed all the interaction is between parent and child and that there is virtually no touching between parents (Women on Words & Images Society 1975: 35). Such a stereotypical child-centered representation surfaces in the adaptation of Tango and is more largely symptomatic of the French social, political and cultural norms in which it was produced.

Concluding Words

This article should be of interest to researchers in Translation Studies, but also more largely to researchers in literature, cultural studies or multimodal narratives. The analysis sheds light on the context of publication and reception of picture books featuring same-sex couples in France in light of the situation in the United States. In particular, this context illuminates how such books fell prey to more or less detectable or obvious forms of censorship, including what I call translasorship. The context is key to answer the question of the filtering at stake in the translation of children’s picture books and its potentially censoring nature. Such manipulation or filtering is akin to censorship when it targets a potentially controversial issue in the target culture. Such practices, be they voluntary or involuntary, take a toll on intracultural communication, but also on cross-cultural communication, as highlighted by Billiani: “Censorship […] blocks, manipulates and controls the establishment of cross-cultural communication. By mainly withholding information from certain groups, often dominated and subaltern ones, to the advantage of dominant sectors of society, censorship functions as a filter in the complex process of cross-cultural transfer encouraged by translations” (Billiani 2007: 3).

By and large, the findings of this essay align with Perreau’s demonstration of a “persistence of a straight mind in the [French] nation despite major changes in the law and in everyday behavior with respect to sexual minorities” (Richardson and Parnell 2016: 184). In France, “the heterosexual nuclear family remains the symbolic cement of the national community” (Perreau 2016: 184). Bearing that in mind, further research is needed on the publication and translation of LGBTQ-themed works that target older youth audiences, including multimodal narratives. This essay provides therefore the basis for a more general reflexion on the publication and reception of LGBTQ-themed children’s picture books in Francophone and Anglophone cultures. More generally, it raises the question of how well-challenged books travel between cultures and how different cultures welcome challenging books when they import them.

Appendices

Appendix

Abramchick, Lois (1996): Is Your Family Like Mine. New York: Open Heart Open Mind.

Alaoui, Latifa M. and Poulin, Stéphane (2001): Marius. Le Crest: Atelier du poisson soluble.

Argent, Hedi, and Wood, Amanda (2007): Josh and Jaz Have Three Mums. London: BAAF.

Belmontes, Juan Alfonso and Pudalov, Natalie (2010): La boda de Gallo Pinto. Pontevedra: OQO Editora.

Belmontes, Juan Alfonso and Pudalov, Natalie (2010/2011a): Le mariage de Coquet le coq. (Translated by Maud Huntingdon) Pontevedra: OQO Éditions.

Belmontes, Juan Alfonso and Pudalov, Natalie (2010/2011b): Speckled Cocquerel’s Wedding. (Translated by Marc W. Heslop) Pontevedra: OQO Books.

Berg, Sara and Arpiainen, Johanna (2015): Pyret and the Pingvinpapporna. Färjestaden: Vombat Forläg.

Bertouille, Ariane and Favreau, Marie-Claude (2006): Ulysse et Alice. Montréal: Éditions du Remue-ménage.

Bertouille, Ariane and Favreau, Marie-Claude (2006/2013): Otis and Alice. (Translated by Christie Harkin) Markham: Fitzhenry & Whiteside.

Bontoux, Gilles and Tabatabaï, Axelréza (2012): La Peur de Lou. Carpentras: Éditions Noir Au Blanc.

Bösche, Susanne and Hansen, Andreas (1981): Mette Bor Hos Morten Og Erik. Copenhagen: Fremad.

Bösche, Susanne and Hansen, Andreas (1981/1983): Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin. (Translated by Louis Mackay) London: Gay Men’s.

Boutignon, Béatrice (2010): Tango a deux papas, et pourquoi pas? Paris: Éditions Le Baron Perché.

Brannen, Sarah S. (2008): Uncle Bobby’s Wedding. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Brière-Haquet, Alice and Larchevêque, Lionel (2010): La Princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes. Arles: Actes Sud Junior.

Brown, Forman and Trawin, Leslie (1991): The Generous Jefferson Bartleby Jones. Boston: Alyson Wonderland.

Brue, Christian and Claveloux, Nicole (1999): L’heure des parents. Paris: Éditions Être.

Bryan, Jennifer and Hosler, Danamarie (2006): The Different Dragon. Ridley Park: Two Lives Publishing.

Carter, Vanda (2007): If I Had a Hundred Mummies. London: Onlywomen.

Chabbert, Ingrid and Loueslati, Chadia (2010): La fête des deux mamans. Palaja: Les Petits Pas De Ioannis.

Combs, Bobbie and Hosler, Danamarie (2001): 1, 2, 3: A Family Counting Book. Ridley Park: Two Lives Publishing.

Combs, Bobbie, Keane, Desiree, and Rappa, Brian (2001): ABC: A Family Alphabet Book. Ridley Park: Two Lives Publishing.

Considine, Kaitlyn and Hobbs, Binny (2005): Emma and Meesha My Boy: A Two Mom Story. West Hartford: [Two Mom].

David, Morgane (2007): J’ai 2 Papas qui s’aiment. Paris: Hatier.

Douru, Muriel (2003): Dis… mamans. Paris: Ed. Gaies et Lesbiennes.

Douru, Muriel (2011): Cristelle et Crioline. Paris: KTM Éd.

Drescher, Joan (1980): Your Family, My Family. New York: Walker.

Garden, Nancy and Wooding, Sharon (2004): Molly’s Family. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux.

Haan, Linda de and Nijland, Stern (2000): Koning en Koning. Haarlem: Gottmer Kinderboeken.

Haan, Linda de and Nijland, Stern (2000/2003): King & King. (Translator’s name not mentioned) Berkeley: Tricycle Press.

Haan, Linda de and Nijland, Stern (2004): King & King & Family. Berkeley: Tricycle Press.

Johnson-Calvo, Sarita (1993): A Beach Party with Alexis. Boston: Alyson Wonderland.

Kovess-Brun, Sophie (2015): Le Voyage de June. Vincennes: Des Ronds Dans L’O Éditions.

Lestrade, Agnès de and Petrone, Valeria (2010): L’abécédaire de la famille. Paris: Milan.

Meyers, Susan and Frazee, Marla (2001): Everywhere Babies. San Diego: Harcourt.

Moreno Velo, Lucia and Termenon, Javier (2007): L’amour de toutes les couleurs/The many-colored Love. Paris: La Cerisaie.

Newman, Lesléa (2002): Felicia’s Favourite Story. Ridley Park: Two Lives Publishing.

Newman, Lesléa and Crocker, Russell (1991): Gloria Goes to Gay Pride. Boston: Alyson Wonderland.

Newman, Lesléa and Dutton, Mike (2011): Donovan’s Big Day. Berkeley: Tricycle Press.

Newman, Lesléa and Hegel, Annette (1993): Saturday Is Pattyday. Norwich: New Victoria.

Newman, Lesléa and Souza, Diana (1989): Heather Has Two Mommies. Boston: Alyson Wonderland.

Newman, Lesléa and Thompson, Carol (2009): Mommy, Mama, and Me. New York: Tricycle Press.

Newman, Lesléa and Thompson, Carol (2009): Daddy, Papa, and Me. New York: Tricycle Press.

Riff, Hélène and Nimier, Marie (1997):Comment l’éléphant a perdu ses ailes. Paris: A. Michel Jeunesse.

Oelschlager, Vanita and Blackwood, Kristin (2010): A Tale of Two Daddies. Akron: Vanita.

Oelschlager, Vanita and Blanc, Mike (2011): A Tale of Two Mommies. Akron: Vanita.

Parachini-Deny, Juliette and Béal, Marjorie (2013): Mes Deux Papas. Vincennes: Des Ronds Dans L’O Jeunesse.

Parr, Todd (2008): It’s Okay to Be Different. Boston: Little, Brown and Company for Young Readers.

Pennington, P. (2012): Your Mommies Love You! A Rhyming Picture Book for Children of Lesbian Parents. CreateSpace Independent Platform.

Pittar, Gill and Morrell, Cris (2002):Milly, Molly and Different Dads. Gisborne: Milly Molly.

Pittar, Gill and Morrell, Cris (2002/2004): Milly, Molly et toutes sortes de papas. (Translated by Fabienne Bergantz) Paris: Auzou.

Polacco, Patricia (2009): In Our Mothers’ House. New York: Philomel.

Richardson, Justin and Parnell, Peter (2005): And Tango Makes Three. New York: Simon & Schuster for Young Readers.

Richardson, Justin and Parnell, Peter (2005/2013): Et Avec Tango, Nous Voilà Trois! (Translated by Laurana Serres-Giardi) Paris: Rue Du Monde.

Rigoberto, Gonzales and Alvarez, Cecilia Concepción (2005): Antonio’s Card. San Francisco: Children’s Book.

Schreiber-Wicke, Edith and Holland, Carola (2006): Zwei Papas für Tango [Two Papas for Tango]. Stuttgart/Vienna: Thienemann.

Setterington, Ken and Priestley, Alice (2004): Mom and Mum Are Getting Married! Toronto: Second Story.

Severance, Jane and Schook, Tea (1979): When Megan Went Away. Chapel Hill: Lollipop Power.

Severance, Jane and Schook, Tea (1983):Lots of Mommies. Chapel Hill: Lollipop Power.

Simon, Norma and Flavin, Teresa (2003):All Families Are Special. Morton Grove: A. Whitman.

Sizaret, Nathalie and Dejay, Daphne (2011): Mes mamans se marient. Charenton-le-Pont: Le Monde de Gritie.

Skutch, Robert and Zarrinnaal, Laura Nienhaus (1995): Who’s in a Family? Berkeley: Tricycle.

Tax, Meredith and Hafner, Marylin (1981): Families: Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Texier, Ophèlie (2004): Jean a deux mamans. Paris: L’École des Loisirs.

Thériault, Michel (2017): Ils sont… Moncton: Bouton d’or Acadie.

Thomas, Pat and Harker, Lesley (2012): This Is My Family: A First Look at Same-sex Parents. Hauppauge: Barron’s Educational Series.

Tomie, Paola de (1979):Oliver Button Is a Sissy. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Tompkins, Crystal and Evans, Lindsey (2009): Oh, the Things Mommies Do! What Could Be Better than Having Two? CreateSpace Independent Platform.

Valentine, Johnny and Lopez, Angelo (1993): Two Moms, the Zark, and Me. Boston: Alyson Wonderland.

Valentine, Johnny and Sarecky, Melody (1994): One Dad, Two Dads, Brown Dad, Blue Dads. Los Angeles: Alyson Wonderland.

Valentine, Johnny and Schmidt, Lynette (1991): The Duke Who Outlawed Jelly Beans. Boston: Alyson Publications.

Valentine, Johnny and Schmidt, Lynette (1992): The Daddy Machine. Los Angeles: Alyson Wonderland.

Vigna, Judith (1995): My Two Uncles. Morton Grove: A. Whitman.

Voltz, Christian (2016). Heu-reux. Arles: Éditions le Rouergue.

Walcker, Yann and Rigaudie, Mylène (2013): Camille veut une nouvelle famille. Paris: Auzou.

Walcker, Yann and Rigaudie, Mylène (2013/2014):Henry Searches for the Perfect Family. (Translated by Susan Allen Maurin) Paris: Auzou.

Watson, Katy and Carter, Vanda (2005): Spacegirl Pukes. London: Onlywomen.

Willhoite, Michael (1990): Daddy’s Roommate. Boston: Alyson Wonderland.

Wilson, Anna and Carter, Vanda (2010): Want Toast. London: Onlywomen.

Notes

-

[*]

The author is affiliated to the research centre TRACT (unité de recherche PRISMES - EA 4398 - Langues, Textes, Arts et Cultures du Monde Anglophone), Université Sorbonne Nouvelle.

-

[1]

Association des bibliothécaires de France (1. février 2014): L’association prend position. Association des bibliothécaires de France. Visited 3 June 2015, <http://www.abf.asso.fr/2/22/410/ABF/l-abf-exprime-sa-position-sur-les-pressions-exercees-sur-les-bibliotheques-publiques>.

-

[2]

Tango a deux papas et pourquoi pas? is not officially “labeled” an adaptation in the original work. And yet, the idea of an adaptation is strongly supported by the similarities between the French picture book and the original work, not only in terms of format, visuals, and text, but also in terms of storyline, as hilighted by Minne (2013: 97-98) and Labosse, Lionel (31 mai 2014): Et avec Tango, nous voilà trois! de Justin Richardson, Peter Parnell & Henry Cole. Altersexualite. Visited on 28 March 2017, <http://www.altersexualite.com/spip.php?article809>. A very good point of comparison is the German Zwei Papas für Tango (2006), which is an independent text inspired from the real-life event published one year after And Tango Makes Three. Further research is needed to determine if two-dad penguins are becoming a literary “motif” in children’s books: for instance, the two-dad picture book Pyret and the Penguin Daddies (Pyret and the Pingvinpapporna) was published in Sweden 2015.

-

[3]

A challenge is “a formal, written complaint, filed with a library or school, requesting that materials be removed because of content or appropriateness.” See Morales, Macey (11 April 2016): “State of America’s Libraries 2016” shows service transformation to meet tech demands of library patrons. American Library Association. Visited on 6 June 2016, <http://www.ala.org/news/press-releases/2016/04/state-america-s-libraries-2016-shows-service-transformation-meet-tech-demands>.

-

[4]

American Library Association (26 March 2013): Top Ten Most Challenged Books Lists. American Library Association. Visited 7 March 2017, <http://www.ala.org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10>.

-

[5]

Labosse, Lionel (2006- ): Altersexualité. Visited 27 March 2017, <http://www.altersexualite.com/>.

-

[6]

Alt, Jean-Yves (9 September 2005): L’homoparentalité racontée aux tout-petits. Culture & questions qui font débats. Visited on 15 March 15 2017, <http://culture-et-debats.over-blog.com/article-822226.html>.

-

[7]

Bardou, Florian (12 October 2016): En France, les «Queer studies» au ban de la fac. Libération. Visited 1 March 2017. <http://www.liberation.fr/debats/2016/10/12/en-france-les-queer-studies-au-ban-de-la-fac_1521522>.

-

[8]

The word “translasorship” works as an overlap blend in Kemmer’s typology (2003). According to Kemmer, overlap blends are those in which the “two source lexemes share some phonological material” (2003: 73). The formation of the blend “translasorship” relies on two types of overlapping. First, the overlapping of one shared segment, “NS” (“traNSlation” and “ceNSorship”); second, the overlapping of the segments “TRANSLA-” and “-SORSHIP,” along with the clipping of the other segments of the two words (“TRANSLAtion” and “cenSORSHIP”). I believe this blend fulfills the felicitous conditions mentioned by Kemmer (2003) for it to be successful.

-

[9]

See, for instance, Harvey (1998, 2000) or Berlina (2012).

-

[10]

Epstein is one of the few researchers interested in the circulation and translation of LGBTQ works for the youth. Her research focuses on texts in English and in Swedish.

-

[11]

See appendix. The data were extracted with Altersexualité (see note 3), which presents bibliographic data on LGBTQ books, and via two databases of children’s literature, Memento and Global Books in Print.

-

[12]

The term picture books refers to board books, for infants and young toddlers, early picture books, for children aged 2-5, and standard picture books, for children aged 4-8. See Backes, Laura (6 February 2014): Understanding Children’s Book Genres. Write for kids. Visited 6 March 2017, <http://writeforkids.org/2014/02/understanding-childrens-book-genres/>.

-

[13]

Milliot, Jim (24 February 2014): Children’s Books: A Shifting Market. Publishers Weekly. Visited 17 March 2017, <http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-industry-news/article/61167-children-s-books-a-shifting-market.html>.

-

[14]

Dar, Mahnaz (22 April 2015): We Need More International Picture Books, Kid Lit Experts Say. School Library Journal. Consulted on 17 March 2017, <http://www.slj.com/2015/04/books-media/we-need-more-international-picture-books-kid-lit-experts-say/#_>.

-

[15]

Dorey, Elsa (10 February 2014): Livres jeunesse: une trop sage image de la famille (I). Rue89Bordeaux. Visited 18 July 2015. <http://rue89bordeaux.com/2014/02/livres-jeunesse-trop-sage-image-famille/>.

-

[16]

In the 2000s, barely one picture book featuring same-sex couples was published on average per year in French. After 2010, an increase was noticeable, coinciding with the political debate around “marriage pour tous.”

-

[17]

Speckled Cockerel’s Wedding (2010/2011b) and Le mariage de Coquet le coq (2010/2011a) are not included here because they are both translations from the Spanish original La boda de Gallo Pinto (2010).

-

[18]

Elfassy Bitoun, Rachel (18 February 2016): Translating Children Books: Difficulties and Reluctances. The Artifice. Visited 10 March 2017, <http://the-artifice.com/translating-children-books/>.

-

[19]

Pym, Anthony (7 April 2015): Translation and Economics: Rational Decisions, Competing Tongues, and Measured Literacy. Papers on research methodology. Visited 21 March 2017, <http://usuaris.tinet.cat/apym/on-line/research_methods/2015_Translation_and_economics.pdf>.

-

[20]

See reference in note 15 for other reasons explaining this asymmetry.

-

[21]

The books listed in the two tables are in alphabetical order.

-

[22]

As for the predominance of lesbian mothers in Anglophone picture books (Minne 2013: 96), this is not so obvious in Francophone picture books.

-

[23]