Abstracts

Abstract

Internationalization process theories have been dominated by the Uppsala theory and the new venture theory: they provide explanations for slow international growth by mature firms and fast international growth by young firms, but fail to consider other combinations of age and speed. This article sketches a 2*2 matrix and explores the performance differentials of four internationalization patterns. Building on early empirical evidence from the retailing industry (1998-2004), the combination of young and slow internationalization is preferable to other options, while a young age is generally more likely to yield internationalization performance than any combination of mature internationalization with slow or accelerated speed.

Keywords:

- Internationalization Performance,

- Uppsala,

- New Venture Theory,

- Age,

- Speed

Résumé

La littérature sur les processus d’internationalisation a largement été dominée par la théorie d’Uppsala et la théorie des New Ventures : ces deux approches permettent d’expliquer la croissance internationale lente des firmes matures et la croissance internationale rapide des jeunes entreprises, mais restent muettes sur les autres processus d‘internationalisation combinant âge et vitesse de développement international. Cet article esquisse une matrice 2 * 2 et explore les différences de performances entre quatre processus d’internationalisation. Sur la base de données empiriques de l’industrie de la grande distribution au niveau mondial (1998-2004), une croissance internationale lente dès le plus jeune âge semble préférable à toutes les autres options d’internationalisation. Et s’internationaliser jeune favorise la performance internationale plus que n’importe quel processus d’internationalisation à un âge plus mature, que ce processus soit lent ou rapide.

Mots-clés :

- Performance de l’internationalisation,

- Uppsala,

- Théorie des New Ventures,

- Age,

- Vitesse

Resumen

La literatura sobre el proceso de internacionalización ha sido ampliamente dominada por la teoría de Uppsala y la teoría de New Ventures: Ambas teorías contribuyen a explicar el lento crecimiento internacional por parte de las empresas maduras y el rápido de las empresas jóvenes. Sin embargo, tales teorías no tienen en cuenta otras posibles combinaciones de edad y velocidad de internacionalización. Este artículo examina las diferencias de rendimiento de cuatro procesos de internacionalización según una matriz 2 * 2. Un primer análisis de datos empíricos de la industria de la gran distribución (1998-2004), sugiere que la combinación empresa joven e internacionalización lenta es preferible sobre las otras opciones posibles. En términos más generales, la internacionalización de las empresas jóvenes permite un rendimiento internacional mayor que el de las empresas más maduras independientemente de la velocidad de internacionalización de estas últimas.

Palabras clave:

- Rendimiento internacional,

- Uppsala,

- teoría de New Ventures,

- Edad,

- Velocidad

Article body

It has long been accepted that firms’ operations beyond their domestic boundaries enable them to reap the benefits from foreign market engagements and increase profitability (e.g. Barkema & Vermeulen, 1998). However, empirical support for this assumption has been mixed (Tallman & Li, 1996) and the overwhelming literature on the relationship between internationalization and performance has not achieved consensus (see notably Glaum & Oesterle, 2007: 40 Years of Research on Internationalization and Firm Performance: More questions than Answers[1]). This article is based on some preliminary results drawn from the 1st author’s unpublished dissertation (Cellard-Verdier, 2008) and addresses two of the flaws that have plagued past theoretical and empirical research on the relationship between internationalization and performance.

A first major shortcoming of extant studies results from their static and content-based view of internationalization. Internationalization has often been conceived as the mere degree of “multinationality”, but this does not in itself reflect internationalization as a movement towards foreign markets. Indeed, the recent literature has suggested that it is not the degree that may have an impact on internationalization performance, but the way firms reach this level through time-based considerations (Tallman & Li, 1996; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002). Consequently internationalization should be operationalized through the patterns of the internationalization process (Wagner, 2004). In this article, we examine the internationalization age and internationalization speed of firms in the worldwide retailing industry. Specifically, we demonstrate that Uppsala-based incremental and new venture internationalization processes – the two most influential models in the literature – only reflect two extreme ways of internationalization: a fast international growth preferred by young firms and a slow international growth typically undertaken by mature firms. However, restricting an analysis to these prototypical strategies fails to include two other alternatives, which may also prove successful: a fast international growth by mature firms and a slow international growth by young firms. By combining the two time-related dimensions of internationalization age and internationalization speed, we sketch a 2*2 matrix that should be conceived as a first step towards developing a full-fledged typology (Doty & Glick, 1994).

A second shortcoming in the literature concerns the definition of performance outcomes. Facing the general paucity of clear performance variables in the literature, authors have taken indicators such as ROA, ROS, and ROE (Daniels & Bracker, 1989; Kumar, 1984, Lu & Beamish, 2001), as well as market-based measures such as Beta and risk-adjusted returns (Buhner, 1987; Collins, 1990; Goerzen & Beamish, 2003). However, many of these indicators are not directly applicable to new ventures in their early stages of internationalization (Pangarkar, 2008) as their emphasis is on entering multiple markets quickly (Oviatt & McDougall, 1995). On one side, many market measures may not be applicable to small firms since many are not listed on stock exchanges. On the other side, being early in the stage of internationalization, new venture firms might place strong emphasis on sales growth and an analytical focus on their profitability underestimates their true performance. Therefore, we define growth here as the relative yearly increase in foreign sales, an indicator which has been used quite consistently across a variety of studies (e.g. Cavusgil & Zou, 1994; Chandler & Hanks, 1993; Delmar, Davidsson & Gartner, 2003).

Empirical evidence based on qualitative insights and selected descriptive statistics from the retailing industry 1998-2004 shows that high performing retailers do not necessarily follow one of the two internationalization patterns as predicted by the incremental ‘Uppsala’ and new venture processes, but reflect the two under-explored alternative patterns. Incidentally or deliberately, WAL-MART and CARREFOUR, the two undisputable leaders in the industry, illustrate these two patterns. In the remainder of this article we conceptually develop and illustrate this 2*2 matrix. As a result, the comparison of the four patterns of internationalization opens new avenues for both theoretical and empirical research and also provides valuable insights for managers involved in the internationalization processes of their firms.

Two theories but four internationalization patterns

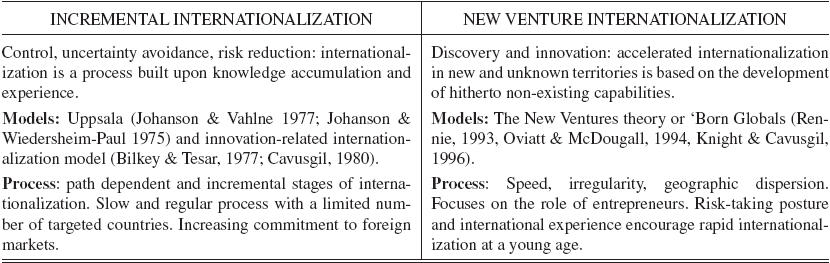

While various streams of research have investigated the nature of foreign market entry, incremental internationalization and accelerated early cross-border engagements have come to form the dominant paradigms in internationalization process research (Zahra, 2005). The first, the so-called Uppsala, or internationalization stage school, purports that firms enter into markets gradually, once they have established their home base (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990; Bilkey & Tesar, 1977). In contrast, the so-called international new venture theory suggests that firms adopt an accelerated foreign market entry process right from inception (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994). Both theoretical approaches have provided succinct explanations on the process of foreign market entry[2]. Yet, none has sufficiently explained the underlying differences in the manner in which firms establish and consolidate their competitive advantage and their differential (and often paradoxical) impact on performance (Zahra, 2005; Sapienza, Autio, George & Zahra, 2006). Table 1 summarizes the major differences and commonalities between the two most influential models in the literature.

Table 1

Incremental vs. new ventures internationalization processes

Incremental internationalization. Incremental internationalization process theory builds on knowledge accumulation and experience. It incorporates several related approaches, which are similar in their explanatory power. The Uppsala internationalization model (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975) and the innovation-related internationalization model (Bilkey & Tesar, 1977), both contend that firms become international in a slow and incremental process with a limited number of targeted geographic markets. To explain internationalization across countries, authors hypothesize that firms have to compensate between market knowledge, resource dependency, and uncertainty. The internationalization of a firm is described as being necessarily path-dependent based on prior knowledge acquisition. Thus, internationalization is a process built upon the reduction of uncertainty by knowledge accumulation. Knowledge of the firm increases with time and experience so that firms choose an incremental pattern of internationalization, gradually seizing opportunities on a country-by-country basis. All in all, a strong underlying assumption of the gradualist approach is that firms initiate their first international entry once they have a strong domestic market base, i.e., at an older age. Internationalizing at an older age supposes building on the referential knowledge base of the home market and competitive advantage in foreign markets is gained by exploiting current home-based advantages.

The incremental view of internationalization has not been without its critics. As the environment has changed significantly since the traditional internationalization theories were developed, firms have quite often been required to speed up their foreign market entry processes. The increased level of globalization in many industries may further lessen the perceived risk of entering foreign markets and partly explains the observed increase in the speed of internationalization. Technological innovation aside, the presence of an increasing number of people with international business experience has established new foundations for multinational enterprises (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994). Crick & Jones (2000) found that many firms were set up by managers with previous experience in international markets, who had already dealt with the complexities of international operations, appreciated the risks and resource implications, and even more important, developed a network of customers and contacts on which to build for setting up their own firms. Not surprisingly then, given this criticism, a new theoretical approach has started to develop since the late 1980s. This relates to the establishment of new ventures as firms with an international orientation right from inception (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994, 1995).

New venture internationalization. Due to environmental changes and the limited explanatory potential of the incremental process theory of internationalization, Johanson & Mattson (1988) have pointed out that some firms might follow a different pattern of internationalization than suggested by the stage models. More recently, several authors have emphasized a new phenomenon of small and medium enterprises that are becoming international soon after being founded (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005, 1994; Autio, Sapienza & Almeida., 2000; Rennie, 1993; Knight & Cavusgil, 1996; Madsen & Servais, 1997). This idea gave the impetus for the concepts of “born globals” and “international new ventures” with the latter providing the name for the theory (McDougall, Shane & Oviatt, 1994, Zahra, 2005). This new stream of research started from the definition of international new ventures as “a business organization that, from inception, seeks to derive significant competitive advantage from the use of resources and the sale of output in multiple countries” (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994, p. 49) or “born globals”, defined as firms that have reached at least 25% of foreign sales within three years after establishment (Madsen, Rasmussen & Servais, 2000). The theory of international new ventures mostly relates to these early and rapid internationalization processes. However, internationalizing at an earlier stage involves more risk-taking than the well-established internationalization processes of older firms (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994). This may be due to the fact that new ventures choose to pursue international opportunities aggressively in order to capture capabilities on a global-scale.

The born-global approach presents a unique challenge to incrementalism and stage theory (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994). If internationalization were possible only by knowledge accumulation and experience, then new ventures could not be international and successful from inception. Older firms with the necessary resources and skills that enable investments in learning and thus effective adaptation were clearly in a superior position. Yet those established firms are often subject to structural inertia that prevents or limits their ability to grow quickly abroad (Oviatt & McDougall, 1995). In this vein, internationalizing at an earlier stage may have advantages as compared to an established company whose ability to learn and develop its operations may be limited (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994).

In order to solve the dilemma posed by the inconclusive performance results of both incremental and new venture theory (Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002; Wagner, 2004), researchers have suggested that internationalization should not only be considered from a content but also through a process lens. This includes the rates and patterns by which firms organize their internationalization processes and incorporates the notion of time (Jones & Coviello, 2005). Specifically, internationalization processes can be distinguished according to the time elapsed until a firm starts international activities (Reuber & Fischer, 1997; McNaughton, 2000) and we refer to this as internationalization age. Further we relate to the rate at which internationalization occurs as the speed of internationalization (Coviello & Munro, 1997; Jones 1999). Differences in internationalization age and speed of internationalization suggest new ways of accounting for different internationalization processes that are likely to entail performance differentials. By combining those two dimensions, we establish a 2*2 matrix that may enrich theoretical development and invites us to investigate two additional internationalization patterns (see Table 2). In the next sections, we wish to examine the heuristic power of this matrix, i.e., answer the question whether it adds new light to our understanding of firms’ internationalization patterns. To do so, we apply this matrix to the mass grocery retailing industry, and then explore the performance differentials across internationalization patterns.

Internationalization processes in the mass grocery retailing industry

For several reasons, we chose the mass grocery retailing industry as a relevant setting to examine the heuristic power of our matrix. First the pursuit of international development has been a major target for most players in the industry (Hallsworth, 1992, Williams, 1992a, 1992b, Treadgold, 1988, Alexander & Myers, 2000, Dawson, 1994). Second, whereas the Uppsala theory befits all industries, there is no consensus on the applicability context of the international new venture theory. Some authors argue that the international new venture phenomenon is only observable in knowledge-based industries (Burgel & Murray, 2000), while others defend its existence in all industries (Rennie, 1993). Thus, the retailing industry is interesting for examining and comparing the relevance of the two dominant theories of internationalization (Akehurst & Alexander, 1996). Lastly, the retail industry includes a large variation of internationalization ages from one-year old firms to 204 year-old firms and also shows differential rates of internationalization speed.

Our population includes all internationalized companies in the world in the grocery retailing industry, based on exhaustive data from Planet Retail, a leading consulting firm specialized in worldwide retailing. Retailers in the population are active in at least one of the six store formats: supermarkets, hypermarkets and superstores, convenience stores, discount stores, neighborhood stores, and cash and carry. We consulted additional secondary sources such as company websites, the specialized press, sector analyses, biographies, and annual reports to complement our data. We defined international retailers as firms having stores in at least two countries (Dunning, 1989). Former studies have considered firms as being international when they were implanted in at least six countries (Goerzen & Beamish, 2003) but we take the view that young internationalizers cannot be that internationalized at an early stage (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005). Among the 96 international retailers making the population, we selected those who had been present for at least three years in a row in our 7 year period. In sum, we studied 86 international retailers from 1998 to 2004. Two empirical factors suggest that the 1998-2004 time frame is especially relevant for our purpose. First, retailers developed intense international activities during that period (including both entries in and exits out of countries, and growth or decline at the country level). Second, retailers experienced a wide range of variations in their speed of internationalization (i.e., some firms progressed slowly and others rapidly).

Internationalization age. Internationalization age refers to the time taken to begin international activities (Reuber & Fischer, 1997; McNaughton, 2000). Internationalization age was measured by the number of years between a firm’s founding date and its first international sales abroad (Autio et al. 2000). As regards internationalization age, the retailing industry is interesting because retailers are widely distributed according to this variable (Figure 1). The average internationalization age in the population is 59 while 30 is the median.

Figure 1

Internationalization Age

Some firms begin their internationalization right from inception and others very late in their history. For instance the German company named METRO started its first international outlet in the Netherlands in 1968, four years after its foundation. The Portuguese retailer MODELO CONTINENTE did the same in Brazil in 1989. On the opposite end, another Portuguese retailer, JERONIMO MARTINS, created as early as 1792, and one of the first retailers in the world, started its internationalization very late in 1995 in Poland and in 1997 in Brazil. WAL-MART expanded abroad to Mexico only after 30 years of operations in the US.

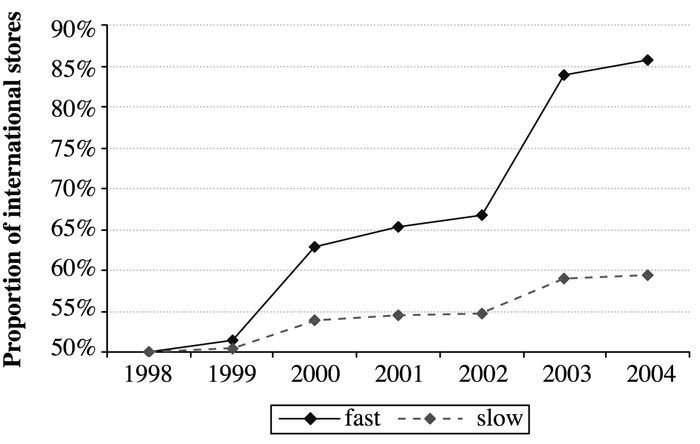

Internationalization Speed. Speed is indicative of the rate by which a firm undertakes foreign commitments (Jones & Coviello, 2005). It is a time-based measure representing how fast a firm develops outlets abroad. To measure internationalization speed, we adopted Wagner’s methodology (2004). We defined internationalization speed as the change in the ratio of foreign entities to total entities (Lu & Beamish, 2004) between 1998 -2004. The larger the change over the seven-year period, the higher is the expansion speed. Slow internationalizers are firms that choose a gradual process with a low increase in the ratio of foreign stores to total stores during our period of observation. Fast internationalizers register a high increase of this ratio. Among the 86 retailers and within the period of observation, the means of internationalization speed is 1%. Figure 2 shows an example of both patterns

Figure 2

Internationalization Speed

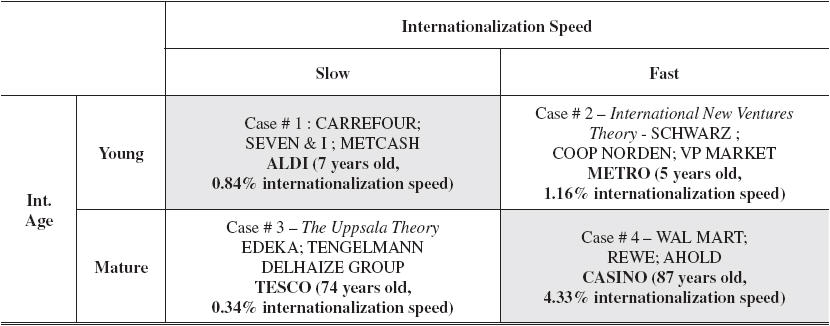

Four internationalization processes. Table 2 presents the matrix of internationalization processes with examples of prominent retailers

Table 2

A matrix of internationalization patterns with examples from retailers

Case 1. CARREFOUR (France), ALDI (Germany), METCASH (Australia) and SEVEN & I (Japan) are young internationalizers that pursue a slow internationalization process. For instance, ALDI was created in 1960 and started its internationalization in 1967. In 2004, it was implanted in 14 countries. However, from 1998 to 2004, the ratio of its foreign stores to total stores increased only by 0.84%. This ratio is low considering that ALDI entered four countries during this period: Luxembourg (1997), Ireland (1999), Australia (2001), and Spain (2002).

Case 2. SCHWARZ (Germany), COOP NORDEN (Scandinavian: Swedish, Norwegian and Danish), VP MARKET (Lithuania) and METRO (Germany) are young internationalizers that pursue a fast internationalization process. METRO was created in 1964 and operated its first international establishment in the Netherlands in 1968. It is implanted in 26 countries and during the period of observation, its ratio of foreign stores to total stores increased by 1.16%.

Case 3. TESCO (UK), TENGELMANN (Germany), DELHAIZE GROUP (Belgium) and EDEKA (Germany) are mature internationalizers that pursue a slow internationalization process. In this category, firms start their first international establishment later and their internationalization follows a slow curve. TESCO started its internationalization at the age of 74 years and its speed is about 0,34% during this period, while its number of countries increases from 7 to 13. This means that TESCO experiments carefully in these new countries.

Case 4. Finally, WAL MART (United States), CASINO (France), AHOLD (The Netherlands) and REWE (Germany) are mature internationalizers that pursue a fast internationalization process. CASINO started its internationalization process at 87. However, its internationalization speed is very high. CASINO increases its foreign presence at a rate of 4,33% during the period. It increases its number of countries by 18 in 7 years.

Interestingly, the two industry leaders, namely CARREFOUR and WAL-MART, have followed completely different internationalization processes, and do not support the two dominant ones. CARREFOUR started its internationalization at a young age, and though the number of countries of implantation increased, its foreign stores ratio decreased during this period. Until 2004, CARREFOUR entered 38 countries and only exited two. On the contrary, WAL-MART started its internationalization process rather late at 31 years of age. However, its increase in foreign stores ratio reached almost 3% with only half the number of Carrefour’s countries. While the two cases are not sufficient to build theory, they clearly stir interest in different variants of the internationalization-performance relationship. They also present initial proof that there are viable alternatives to the well-established internationalization paths suggested by both the Uppsala and the new venture schools of thought.

Relating internationalization processes and performance

In this section, we examine whether our matrix of internationalization patterns can yield additional insights on the relationship between internationalization and performance. We define our measure of performance: international sales growth, then provide a general proposition relating “age-times-speed” to performance. The interpretations of the results will form part of the major contributions of this article.

International sales growth. Performance relates to expectations about the achievement of firms’ objectives such as profitability and return on investment (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994). However, early internationalizers do not have the opportunity to substantiate these conventional performance outcomes as they have a very limited opportunity to realize their strategy and generate a sustained revenue stream. Conventional measures of performance do not capture the early intent of these firms, whose short-term objective is to quickly internationalize in multiple markets. Therefore, much of the theoretical literature on new ventures has focused on (international) sales growth (Oviatt and McDougall, 1995, 1994; Bloodgood, Sapienza & Almeida, 1996; Chandler & Hanks, 1993), and some authors have even used sales growth to distinguish these entrepreneurial firms from non-entrepreneurial firms (McDougall, Shane & Oviatt, 1994). Sales growth is also widely used by trade publications, industry experts, and venture capitalists (Sapienza et al. 2006). We use international sales growth here as the conventional measure of performance (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994) because it seems better suited to international outcomes of both young and mature internationalizers. International sales are defined as all sales revenues derived from retailers’ international operations. We computed the change in international sales by calculating the relative growth of international sales per year, then averaged the ratio over the period by calculating the mean of the seven years. This procedure is in line with previous studies, which have considered relative sales growth as the best-established measure of growth (Delmar, Davidsson & Gartner, 2003).

Age and speed as predictors of international sales growth. Theoretically, incremental and new ventures scholars have provided contrasting explanations regarding age at first international entry and speed of the internationalization process, yet very few studies have been designed to capture and interpret time-related phenomena (Coviello & Jones, 2004). Studies focusing on the relationship between age and growth have their roots in population ecology (Carroll & Hannan, 2000) but very few empirical studies have addressed international contexts (Hannan, Carroll, Dobrev & Han , 1998). Age is known to negatively influence growth and firms that internationalize early are more aware, more capable and more willing to pursue international opportunities (Autio et al., 2000). Moreover, internationalization requires firms to unlearn past routines and learn new ones (Barkema, Shenkar, Vermeulen, Bell, 1997). At a younger age, routines are less established, such that firms are less embedded in their past routines; indeed learning impediments through established routines are lower. Barkema et al. (1997) underlined the difficulty for older firms to unlearn established routines and adopt new ones, due to existing cognitive, political, and relational constraints. The older the firm, the more established are the routines and practices, and the higher is the level of organizational inertia (Hannan & Freeman, 1984). Structural inertia arguments imply that younger firms are more likely to dynamically participate in the internationalization process than older firms (Autio et al., 2000). Finally, the liability of senescence of older firms indicates that capabilities exhibit an increasing misalignment with the environment and are resistant to change over time (Hannan, 1998). Therefore, all of these convergent lines of thought suggest that growth should be higher at a younger age.

That said, our setting is different as we are interested in the interaction effect between internationalization age and internationalization speed on international sales growth. In principle, the speed of internationalization should limit the time frame to transfer, accumulate and generate knowledge. According to the organizational learning tradition, an increasing speed of internationalization would lead to increasing difficulties of internationalization arrangements since it reduces time for adaptation, generation of knowledge and development of absorptive capacity (Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002). Therefore, based on age-related liabilities and speed constraints, we offer the following proposition:

International sales growth will be relatively higher for young internationalizers at a low speed, relatively lower for late internationalizers at a high speed, and moderate [read: in-between these two extremes] for young internationalizers at high speed and late internationalizers at low speed.

Methodological Overview. The findings that we shall report in the next paragraphs are part of a larger research program (Cellard-Verdier, 2008). Consequently, we wish to provide an overview of the control variables and statistical methods employed. As mentioned earlier, the population includes observations for 86 firms, each computed in their respective country implantations over seven years (1998-2004).

Since several variables might affect the hypothesized relationships between age, speed and international sales growth, we included six controls: company size, market scope, country scope, competitive intensity, international experience, and exit. Company size was measured by the logarithm of a firm’s total sales over the period. Market scope corresponds to a company’s degree of diversification. Measured by the number of formats of worldwide implantation, it is likely to be negatively related to performance (Delios & Beamish, 1999). Country scope represents the number of countries of implantation (Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002), and researchers formerly showed that performance increases with the number of countries (Tallman et Li, 1996, Goerzen et Beamish, 2003). We also considered the competitive intensity measured by the firm-level Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI). International experience measures for how long a firm has been established abroad. The positive effect of international experience on performance has largely been investigated (Madhok, 1996). However, as international experience increases, it may lead to a firm’s lock-in, since it supports mature age-related liabilities. Lastly, we control for exit. Exit can be either dissolution, i.e. closure of an existing business in a country, closure, or divestiture, i.e. the sale of this business (Li, 1995). Researchers previously showed that performance is negatively related to exits, since firms exit from a country if performance is low (Montgomery & Thomas 1988).

Alternative sets of hypotheses predicting both international sales growth but also exit were tested through Ordinary Least Square multiple regression models on SAS 9.0 and fuller results can be examined elsewhere (Cellard-Verdier, 2008). Below, we wish to report on selected findings in order to solve our initial research question: is there such a thing as one singular internationalization process that would significantly surpass others with respect to international sales growth?

Findings and contributions

Given our conceptualization of the 2*2 matrix of internationalization processes, and the broad formulation of our guiding proposition, we start with a visual representation of the interaction effects of international age and speed on international sales growth (Figure 3).

Figure 3

The two-ways interaction effects

The two slopes indicate the following: whatever their speed of internationalization, younger retailers outperform more mature retailers. This result supports the negative relationship between firms’ internationalization age and their potential international sales growth that has been reported elsewhere (Autio et al., 2000). However, isolating this direct relationship neglects the complex set of internationalization drivers. While former research has suggested that the relationship between internationalization and firm performance is contingent on foreign expansion speed (Wagner, 2004; Barkema & Vermeulen, 1998), our findings provide confirmatory evidence of this moderating effect (Table 3).

Table 3

A matrix of internationalization patterns with retailers’ performance

Young internationalizers that pursue a slow internationalization process enjoy higher international sales growth rates as compared to young internationalizers that pursue a fast internationalization process. But mature internationalizers that pursue a fast internationalization process reach higher performance results than mature internationalizers that pursue a slow internationalization process. For instance, CARREFOUR and EDEKA both followed a slow internationalization process, but started their first international expansion at different ages. CARREFOUR began its internationalization at a younger age and enjoyed an international growth of 17.74% during the period[3]. In turn, EDEKA started its international expansion at 84 and experienced an international sales growth rate of 1.06%. Among fast internationalizers, METRO and WAL-MART are two well-known firms. METRO internationalized early (5 years old) and enjoyed a 7.99% international sales growth. WAL-MART internationalized at a much older age (30 years old), yet experienced an international sales growth of 38.8%. In short: when a firm starts its internationalization process, it is better to be slow if young, to be fast if old, but it is better to start young anyway!

Behind that evoking yet simplifying slogan, our contributions refer to the existence of alternative performing paths to internationalization. By building on the different combinations of age and speed of internationalization, we not only dealt with the Uppsala and the international new venture theories but also considered the two others processes. Apart from large and mature internationalizers (case # 3) and small and young new international ventures (case # 2), our findings (preliminary descriptive statistics and correlations) suggest that two other processes (cases # 1 and # 4) yield significantly better internationalization performance outcomes. These two additional patterns of internationalization are illustrated by CARREFOUR and WAL-MART, the two undisputed leaders in the field. Recently, Bell, McNaughton & Young (2001) have talked about so-called “born-again global firms” as those firms that begin a rapid international expansion process after an extensive period of domestic development (case # 4). Our findings further reveal not only born-again global firms like WAL-MART but also firms, that we propose to label “careful-born global” like CARREFOUR (case # 1), which may enjoy higher internationalization outcomes than more established incrementalists and born-globals.

Explaining the performance of CARREFOUR-like “careful-born global”. Fifty years ago, Penrose (1959) argued that a firm’s growth depends on its potential to sense and seize opportunities and to respond to them by reconfiguring its routines. Applied to an international context, a firm’s growth through the expansion of international opportunities would be influenced by its ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure resources and routines to cope with a changing environment. When a firm initiates its first international market entry, it builds routines and rules for change (Guillèn, 2002). Internationalizing early generates specialized capabilities for rapid adaptation to the external environment (Sapienza et al., 2006). A slow speed of internationalization provides sufficient time for the firm to better address and experiment with internationalization constraints. These firms take their time to effectively absorb the new complexity, design a suitable organizational structure, and reap the benefits of internationalization while concurrently managing threats and assimilating foreign knowledge (Wagner, 2004). In addition, early internationalizers enjoy some learning advantages of newness (relatively to more mature internationalizers) that can enhance growth (Autio et al., 2000). Taken collectively, the younger the firm at internationalization, the stronger its internationalization efforts for learning (Sapienza, De Clercq & Sandberg, 2005) and for rapid adaptation. Typically, younger international firms see foreign markets as less ‘foreign’ and embryonic routines reduce the time and costs of dynamic capability development (Autio et al., 2000). Internationalization exposes the firm to new exogenous situations (cultural, economical, political, competitive conditions) and new endogenous constellations (reconfiguration of resource allocations) and younger firms often have more time and the necessary attributes to answer them.

Explaining the performance of WAL-MART-like fast and mature internationalizers. Born-again global firms (Bell, McNaughton & Young, 2001) are those firms that begin a rapid international expansion after an extensive period of domestic development. Mature internationalizers have accumulated domestic resources that strengthen their domestic competitive advantage. WAL-MART’s ‘fast and furious’ internationalization strategy during our window of observation is largely based on the leverage of its financial resources and buying power over multinational suppliers. In WAL-MART’s case, there is little doubt that standard resource-based-view (RBV) arguments provide a compelling explanation for its international performance.

In addition, organizational learning theory provides further insight (Forsgren, 1989; March, 1991; Sapienza et al., 2006). For instance, an accelerated speed of internationalization reduces both the time for learning and knowledge transfer. It requires the ability to integrate new environmental settings, which is dependent on the absorptive capacity of firms (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990). Absorptive capacity is a dynamic capability pertaining to knowledge creation and utilization to enhance a firm’s competitive advantages. Mature internationalizers rely on home-based and cumulative knowledge acquisition experience to build absorptive capacity. Once sufficient, firms extend market coverage and then benefit from higher positional advantage and legitimacy (Podolny, 1993), which provide them with a solid background to face hazards rate. An initial large stock of resources helps to absorb the negative effects of accelerated international growth, hence overcoming structural inertial forces. Essentially, they rely on the two different sets of absorptive capacity.

First they count on their own domestic consolidated knowledge base that constitutes their potential absorptive capacity, i.e., prior related knowledge to assimilate and use new foreign knowledge input. Second, firms’ rapid and path-breaking internationalization process enables them to overcome their age liabilities by developing dynamic routines for change which constitutes their realized absorptive capacity. Mature firms following a fast internationalization track may then have an increased absorptive capacity (both potential and absorptive) and develop dynamic capabilities that foster international growth rates (Prange & Verdier, 2010).

Why would born-globals and incrementalists under-perform? Our third and final contribution relates to the two well-know internationalization processes that seem to be under-performing. In the following, as we did for the two former processes, we elaborate on the reasons that could explain such a low performance.

Born-globals, i.e., young and fast internationalizers often do not have an incubation phase. Managers’ prior experience is often cited as influencing the speed of internationalization (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005) but as firms internationalize early, this experience has often not been sufficiently entrenched. Experience that comes too fast can overwhelm managers leading to an inability to transform experience into meaningful learning (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Young and fast internationalizers may face a lack of consolidation capabilities, because permanent exploration of foreign markets requires resources and capabilities that are solely generated in a preceding period of consolidation (Rothaermel & Deeds, 2004). Therefore, new ventures might neglect building capabilities for positional advantage and social embeddedness, i.e., consolidation capabilities (Johanson and Vahlne, 2009; Ellis, 2010). In a fast internationalization process, younger firm’s lack of positional advantage (i.e., status, trust, reputation) and the absence of incipient routines can reduce the growth outcomes. Moreover, firms that set up foreign entities face time compression diseconomies because there are limits to the capacity of absorption (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Vermeulen & Barkema (2002: 641) stated that overload caused by a very high pace reduces a firm capacity to further absorb expansion. In brief, young internationalizers may sometimes overstretch their absorptive capacity. Eventually, this line of thought is fully consistent with population ecology frameworks and their underlying arguments concerning the liabilities of newness: newly founded firms are more likely to fail because of the scarcity of their initial resources (Freeman, Carroll & Hannan, 1983).

Incrementalists, i.e., mature internationalizers encourage the accumulation of knowledge and experience. They build their internationalization after a period of domestication of their competitive advantage. Therefore, they base their internationalization on home-based knowledge, which they transfer abroad. Competitive advantage in foreign markets is gained by exploiting current home-based knowledge. Accordingly the internationalization of mature and slow firms is linked to path-dependent learning and knowledge accumulation through international experience. Subsequently, internationalization is contingent on a given portfolio of knowledge but also on a firm’s potential to reconfigure and deploy them for foreign market entry. Typically, the firm intends to pursue domestic consolidation of knowledge and competitive advantage until it reaches a sufficient level of threshold necessary to support multinational activity (Forsgren, Holm & Johanson, 1995; Tallman & Fladmore-Lindquist, 2002). However, this may also lead to a lock-in for further international opportunities as a firm develops its knowledge in a path-dependent process in which possible future steps are constrained by its history. This is exactly why this cumulative knowledge development that limits feasible paths for internationalization (Knudsen & Madsen, 2002). Eventually, cumulative capability development results in older firms being more static, exhibiting structural inertia (Hannan et al. 1998).

Limitations and conclusions. As any research, this one is not without limitations. Notably, our interpretations are based on early findings and more quantitative research is needed to identify the performance consequences resulting from the interaction of international age and internationalization speed. While the reported findings are free from sample selection biases (we consider the entire population of retailers worldwide, whatever their country of origin) and robust after controlling for company size, market scope, country scope, competitive intensity, international experience, and country exit (see the ‘Methodological Overview’ paragraph), several additional variables could be taken into account to fully reflect the subtleties of internationalization patterns. Three of them deserve special scrutiny in further work: the rhythm of international development, conceived as a measure of the (ir)-regularity of international speed; the cultural diversity of the portfolio of countries in which retailers expand; and the firm’s country choices as reflecting its capacity to select (more or less) attractive countries. Also important in longitudinal and evolutionary empirical studies are cohort and period effects (Aldrich & Ruef, 2006), and those effects need to be controlled for if we want to better understand internationalization patterns. Finally, a more in-depth analysis of selected cases of retailers’ internationalization strategies would yield useful insights to our understanding of internationalization patterns, and provide additional robustness to support our results. This would then result in extending the 2*2 matrix into a full-fledged typology (Doty & Glick, 1994).

There are several suggestions for further research. Among the most pertinent avenues is the linkage to recent studies on exploration versus exploitation (March, 1991). Interpreting different processes of internationalization as exploration and exploitation allows for re-examining various combinations, which organizational scholars have recently examined under the label of ambidexterity (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). Only few studies have yet applied an ‘ambidexterity’ approach to an international context (Han, 2005; Barkema & Drogendik, 2007; Luo & Rui, 2009; Prange & Verdier, 2010) so there is ample opportunity to extend the concept beyond its national scope.

In this article, we have established that both young firms following a slow internationalization and mature firms following a rapid internationalization reach higher international sales growth rates than firms following processes as advocated by the Uppsala and international new venture theorists. In a less formal language, and everything else being constant, we would very much like to tell executives and top managers in charge of international expansion that it seems better to proceed slowly if their firm is young, to go fast if their firm is old, and that internationalizing young seems better anyway!

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Sylvie Verdier est chef de projet chez Zurich Financial Services (ZFS), basée à Zürich (Suisse). Elle travaille sur le développement et l’adaptation d’outils et de processus à l’international pour toutes les branches du groupe. Titulaire d’un doctorat de l’Université Lyon 3 (France), elle a été assistante de pédagogie et de recherche à EMLYON Business School et chercheure invitée à l’Université du Connecticut (Etats-Unis) et à l’Université de Saint Gall (Suisse). Ses recherches portent principalement sur le processus d’internationalisation, l’ambidextrie et la performance des firmes multinationales. Sylvie Verdier a été finaliste pour le prix Newman Award de l’Academy of Management (AoM) pour le meilleur article tiré d’une thèse. Elle a aussi été finaliste pour le prix de thèse de l’Université Lyon 3 et pour le prix de la meilleure thèse en management stratégique de l’Association Internationale de Management Stratégique (AIMS).

Sylvie Verdier is a project manager for Zurich Financial Services (ZFS), based in Zürich (Switzerland). She drives the development and adaptation of tools and processes across countries and Lines of Business. She obtained her Ph.D. from the University Lyon 3 in France. Before joining ZIC, she was a research associate and lecturer at EMLYON Business School and a visiting scholar at the University of Connecticut (USA) and the University of San-Gallen (Switzerland). Her main research topics deal with the internationalization process, ambidexterity and performance of MNC. Sylvie Verdier was finalist for the Academy of Management (AoM) Newman Award for single-authored outstanding papers based on a dissertation. She was also finalist for the best dissertation award of the University Lyon III and the Association Internationale de Management Stratégique (AIMS) respectively.

Sylvie Verdier es jefe de proyecto en Zürich Financial Services (ZFS), basada en Zúrich (Suiza). Trabaja sobre el desarrollo y la adaptación de herramientas y procesos a nivel internacional para todas las ramas del Grupo. Titular de un doctorado de la Universidad Lyon 3 (Francia) ha ejercido como asistente de pedagogía y de investigación en EMLYON Business School y como investigadora invitada en las Univesidades de Connecticut (Estados Unidos) y Saint Gall (Suiza). Sus investigaciones tratan principalmente sobre el proceso de internacionalización, la ambidextría y la performance de las empresas multinacionales. Sylvie Verdier ha sido finalista del Premio Newman Award de L’Academy of Management (AOM) por el mejor artículo sacado de una tesis. Ha sido también finalista del Premio de tesis de la Universidad Lyon 3 y del Premio de la major tesis en management estratégico de L’Association Internacional de Management Estratégico (AIMS).

Christiane Prange est Professeur associée en Marketing et Stratégie internationale à EMLYON Business School, France. Après une carrière dans l’industrie et le conseil, elle obtient un doctorat de l’Université de Genève et d’un MBA de la Free University de Berlin. Ses recherches actuelles portent sur les stratégies globales, l'innovation collaborative et les fonctions innovantes pour les consommateurs dans les firmes multinationales. Christiane Prange a publié six ouvrages et de nombreux articles dans des revues académiques et professionnelles et consulte dans plusieurs entreprises multinationales. Elle tient ou a tenu des positions de professeure visitant à la Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration et la Danube University Krems (Autriche), l’Université de Liverpool et The Open University (RU). Elle enseigne sur le Campus de Shanghai d’EMLYON Business School et anime de nombreux séminaires de formation pour dirigeants.

Christiane Prange is an Associate Professor of International Marketing and Strategy at EMLYON Business School in France. After a career in consulting and industry, she obtained a Ph.D. from Geneva University and an MBA from Free University Berlin. Her current research interests revolve around global strategies, collaborative innovation and innovative customer functions in the MNC. She published six books and several academic and managerial articles and consults in numerous multinational companies. She holds or has held visiting positions with the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration and the Danube University Krems in Austria, the University of Liverpool and The Open University in the UK. She also teaches at the Shanghai Campus of EMLYON Business School and in various executives and corporate programmes.

Christiane Prange es Profesora Asociada en Marketing y Estrategia internacional en EMLYON Business School, Francia. Tras una carrera en la industria y en consultoría, obtiene su doctorado en la Universidad de Ginebra y el MBA en la « Free University de Berlín ». Sus investigaciones actuales tratan sobre estrategias globales, la innovación colaborativa y las funciones innovadoras para los consumidores en las empresas multinacionales. Christiane Prange ha publicado 6 obras y numerosos artículos en las revistas académicas y profesionales y es asesora en varias empresas multinacionales. Ha ocupado y ocupa puestos de profesora visitante en Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration, en la Danube University Krems (Austria), en la Universidad de Liverpool y en the Open University (Reino Unido). Enseña en el campus de Shanghai de EM LYON Business School y anima numerosos seminarios de formación para dirigentes.

Tugrul Atamer est professeur de management stratégique et doyen du corps professoral à EMLYON Business School. Après une expérience industrielle en Turquie, il reçoit son doctorat de l’Université des Sciences sociales de Grenoble. Ses activités de recherche portent sur les dynamiques internationales des industries, la mise en oeuvre des stratégies globales et plus généralement le changement stratégique de grande ampleur. Auteur de nombreuses publications, notamment dans Long Range Planning et Journal of World Business, il est également consultant auprès des firmes multinationales en stratégie internationale, conduite de changement et élaboration du plan stratégique. Il est co-auteur de nombreux ouvrages dont Diagnostic et Décisions Stratégiques qui a obtenu le grand prix du livre de management et de stratégie Afplane-Les Echos en 1993. Il a également publié The Dynamics of International Competition (Sage 2000) pour une audience anglo-saxonne.

Tugrul Atamer is Professor in Strategic Management and Dean of the Faculty at EMLYON Business School (France). After industrial experiences in Turkey he obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Grenoble (France). His research focuses on the implementation of global strategies, the international dynamics of industries and more generally large-scale strategic changes. He has carried out consultancy assignments with several multinational companies. His consulting experiences include facilitating top management teams in strategic planning processes, developing and implementing international strategies and managing organizational change. Dr. Atamer's research has been extensively published in leading journals, including Long Range Planning and Journal of World Business. His books Diagnostic et Décisions Stratégiques and L’Action Stratégique : le Management Transformateur have been long-sellers in France and the former one was awarded the Afplane-Les Echos Best Management Book of the year in 1993. Dr. Atamer also published The Dynamics of International Competition (Sage, 2000) for an Anglo-Saxon audience.

Tugrul Atamer es profesor de management estratégico y decano del cuerpo profesoral en EMLYON Business School. Tras una experiencia industrial en Turquía, recibe su doctorado en la Universidad de Ciencias Sociales de Grenoble. Sus actividades de investigación tratan sobre las dinámicas internacionales de las industrias, la puesta en marcha de estrategias globales y de forma más general el cambio estratégico de gran envergadura. Autor de numerosas publicaciones, principalmente en Long Range Planning y Journal of World Business, es igualmente asesor para empresas multinacionales en estrategia internacional , conducta de cambio y elaboración del plan estratégico. Es coautor de numerosas obras, entre otras, Diágnóstico y Decisiones Estratégicas que ha obtenido el gran premio del libro de management y estrategia Afplane-Les Echos en 1993. Ha publicado igualmente The Dynamics of International Competition (Sage 2000) para una audiencia anglosajorna.

Philippe Monin est professeur de management stratégique et Doyen Associé à la Recherche à EMLYON Business School. Il est titulaire d’un doctorat de l’université Jean Moulin Lyon III et de la Richard Scott Distinguished Award for Scholarly Contribution de l’Académie Américaine de Sociologie (2005). Dans le champ du management stratégique, il étudie les processus d’intégration dans les fusions et acquisitions. En particulier, il examine l’influence de la justice organisationnelle, de l’exemplarité et de la confiance, des perceptions de comptabilité culturelle et des identifications multiples sur des variables comme la volonté de coopérer. En sociologie, il étudie la transformation des champs culturels, notamment le champ viticole et la grande cuisine française. Ses recherches actuelles portent sur le rôle des mouvements sociaux, des catégories et des critiques, et des antécédents et conséquences de l’adoption de l’innovation. Ses travaux ont notamment été publiés dans American Journal of Sociology, American Sociological Review, Strategic Management Journal et Organization Science.

Philippe Monin is Professor in Strategic Management and Associate Dean for Research at EMLYON Business School (France). Philippe received his Ph.D. in 1998 from University Lyon III (France), and the W. Richard Scott Distinguished Award for Scholarly Contribution from the American Sociological Association, in 2005. In the field of strategic management, he studies integration processes in mergers and acquisitions. Notably, he considers the influence of organizational justice, exemplarity and trust, perceptions of cultural compatibility, and transitions among identifications on outcome dimensions such as the willingness to cooperate. In the field of sociology, he examines the transformation of cultural fields, including notably the Wine industry and French Haute Cuisine field. Current topics include the role of critics, social movements and categories and the antecedents and consequences of innovation adoption. His work has appeared in journals such as American Journal of Sociology, American Sociological Review, Strategic Management Journal or Organization Science.

Philippe Monin es profesor de management estratégico y Decano Asociado a la investigación en EMLYON Business School. Es titular de un doctorado de la Universidad Jean Moulin III y de la Richard Scott Distinguished Award for Scholarly Contribution de la Academia Americana de Sociología (2005). En el campo de management estratégico, estudia el proceso de integración en las Fusiones y Adquisiciones. Examina particularmente la influencia de la justicia organizacional, ejemplaridad y confianza, percepciones de contabilidad cultural e identificaciones múltiples sobre variables como la voluntad de cooperar. En sociología, estudia la transformación de los campos culturales, principalmente en el campo de la viticultura y de la gran cocina francesa. Sus investigaciones actuales tratan sobre el papel que desempeñan los movimientos sociales, categorías y críticas, y antecedentes y consecuencias de la adopción de la innovación. Sus trabajos han sido publicados principalmente en American Journal of Sociology, Americain Sociological Review, Strategic Management Journal o Organization Science.

Notes

-

[*]

The comments expressed in this publication are the author's own personal opinions only and do not necessarily reflect the positions or opinions of the employer

-

[1]

The effects of the degree of internationalization on performance have been found of various natures: negative (Geringer, Tallman & Olsen, 2000), positive (Goerzen & Beamish, 2003, Delios & Beamish, 1999; curvilinear (Lu & Beamish, 2001; Daniels & Bracker, 1989) and even S-Curve (Lu & Beamish, 2004).

-

[2]

Given the focus of this Special Issue of Management International, we purposefully frame the contest between Uppsala and born-global approaches. Of course, we fully acknowledge that several alternative theories are highly referenced and established as demonstrative for firms engaged in internationalization, including notably Dunning’s eclectic paradigm (1977, 2001), Ethier’s OLI triad (1986), Buckley and Casson’s internalization theory (1976, 2009), transaction cost approaches (Hennart, 1982), strategic behavior approaches (Harrigan 1988 or Kogut, 1992), or else springboard perspectives (Luo and Tung, 2007).

-

[3]

The figures that we provide below should be considered with caution and as illustrative: any example can be the subject of historical events. For instance, during the period (in 1999), CARREFOUR merged with another large but less internationalized French retailer: PROMODES. Consequently, the reported international sales growth would have been larger, had we restricted the analysis to the initial perimeter of CARREFOUR. That said, those nuances do not alter our general argument.

Bibliographie

- Akehurst, Gary; Alexander, Nicholas (1996). The internationalisation of retailing. London Frank Cass, 212p

- Aldrich, Howard; Ruef, Martin (2006). Organizations Evolving. London, SAGE, 344p

- Alexander, Nicholas; Myers, Hayley (2000). “The Retail internationalisation process”, International Marketing Review. Vol. 17, N° 4-5, p. 334-353.

- Autio, Erkko; Sapienza, Harry J.; Almeida, James G. (2000). “Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43, N° 5, p. 909-924.

- Barkema, Harry G.; Drogendijk, Rian (2007). “Internationalization in small, incremental or larger steps?”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, N° 7, p. 1132-1148.

- Barkema, Harry G.; Vermeulen,Freek (1998). “International expansion through start-up or acquisition: a learning perspective”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43, N° 5, p. 909-924.

- Barkema, Harry; Shenkar, Oded; Vermeulen, Freek; Bell John H. J. (1997). “Working abroad, working with others: how firms learn to operate international new ventures”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 40, N° 2, p. 426-442.

- Bell, Jim; McNaughton, Rod; Young, Stephen (2001). “Born-again global’ firms – an extension to the ‘born global’ phenomenon”, Journal of International Management, Vol. 7, N° 3, p. 173-189.

- Bilkey, Warren J.; Tesar, Georges (1977). “The export behaviour of smaller-sized Wisconsin manufacturing firms”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 8, N° 1, p. 93-98.

- Bloodgood, James M.; Sapienza, Harry J.; Almeida, James G. (1996). “The internationalization of new high-potential U.S. ventures: antecedents and outcomes”, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, Vol. 20, N° 4, p. 61-76.

- Buckley, Peter J.; Casson, Marc C. (1976). The Future of the Multinational Enterprise. Palgrave Macmillan, 128p

- Buckley, Peter J.; Casson, Marc C. (2009). The Multinational Enterprise Revisited: The Essential Buckley and Casson. Palgrave Macmillan, 288p

- Buhner, Rolf (1987). “Assessing international diversification of west German corporations”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 8, N° 1, p. 25-37.

- Burgel, Oliver; Murray, Gordon C. (2000). “The international market entry choices of start-up companies in high-technology industries”, Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 8, N° 2, p. 33-64.

- Carroll, Glenn R.; Hannan, Michael T. (2000). The demography of corporations and industries. Princeton University Press, 520p.

- Cavusgil, Tamer S.; Zou, Shaoming (1994). “Marketing strategy-performance relationship: an investigation of the empirical link in export”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58, N° 1, p. 1-21.

- Cellard-Verdier, Sylvie (2008). Expliquer la performance internationale des firmes : âge, vitesse et rythme d’internationalisation, diversité culturelle et ambidextrie dans la grande distribution alimentaire mondiale (1998-2004). Doctorat es Sciences de Gestion, Université Jean-Moulin Lyon 3, 267p

- Chandler, Gaylen N.; Hanks, Steven H. (1993). “Measuring the performance of emerging businesses: a validation study”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 8, N° 5, p. 391-408.

- Cohen, Wesley M.; Levinthal, Daniel A. (1990). “Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, N° 1, p. 128-152.

- Collins, Markham J. (1990). “A market performance comparison of US firms active in domestic, developed, developing countries”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol 21, N° 2, p. 271-287.

- Coviello, Nicole E.; Jones, Marian .V. (2004). “Methodological issues in international entrepreneurship research”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 19, N° 4, p. 485-503.

- Coviello, Nicole E.; Munro, Hugh J. (1997). “Network relationships and the internationalisation process of small software firms”, International Business Review, Vol 6, N° 4, p. 361-386.

- Crick, Dave.; Jones, Marian V. (2000). “Small High-Technology Firms and International High-Technology. Markets”, Journal of International Marketing, Vol 8, N° 2, p. 63-85

- Daniels, John D.; Bracker, Jeffrey (1989). “Profit performance: do foreign operations make a difference”, Management International Review, Vol. 29, N° 1, p. 46-56.

- Dawson, John A. (1994). “Internationalization of retailing operations”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol 10, N° 4, p. 267-282.

- Delios, Andrew; Beamish Paul W. (1999). “Geographic scope, product diversification, and the corporate performance of Japanese firms”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 20, N°8, p. 711-727.

- Delmar, Frederic; Davidsson, Per; Gartner, William .B. (2003). “Arriving at high growth”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 18, N° 2, p. 189-216.

- Doty, Harold D.; Glick, William H. (1994). “Typologies as a unique form of theory building : Toward improved understanding and modeling”, Academy of Management Review, Vol 19, N° 2, p. 230-251.

- Dunning, John H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic Approach. In: Ohlin, B. et al. (Eds.), The International Allocation of Economic Activity. London: Macmillan Press, p. 395-418.

- Dunning, John H. (1989). “Multinational Enterprises and the Growth of Services: Some Conceptual and Theoretical Issues”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol 9, N° 1, p. 5-39.

- Dunning, John H. (2001). “The eclectic (OLI) paradigm of international production: Past, present and Future”, International Journal of the Economics of Business, Vol. 8, N° 2, p. 173–90.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M.; Martin, Jeffrey A. (2000). “Dynamic capabilities: what are they?”; Strategic Management Journal, Vol 21, N° 10-11, p. 1105-1121.

- Ellis, Paul D. (2010) “Social ties and international entrepreneurship: Opportunities and constraints affecting firm internationalization”, Journal of International Business Studies, in print.

- Ethier, Wilfried J. (1986). “The multinational firm”, Quarterlw Journal of Economics, Vol. 101, N°4, p. 806-833.

- Forsgren, Mats (1989). Managing the Internationalization Process: The Swedish Case. London: Routledge, 144p.

- Forsgren, Mats; Holm, Ulf; Johanson, Jan (1995). “Division headquarters go abroad – A step in the internationalization of the multinational corporation”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 32, N° 4, p. 475–491.

- Freeman, John; Carroll, Glenn R.; Hannan, Michael T. (1983). “The liability of newness: age dependence in organizational death rates”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, N° 5, p. 692-710.

- Geringer, Michael J.; Tallman, Stefen; Olsen, David M. (2000). “Product and international diversification among Japanese and multinational firms”, Strategic Management Journal,, Vol. 21, N° 1, p. 61-80.

- Glaum, Martin; Oesterle, Michael-Jörg (2007). “40 years of research on internationalization and performance: more questions than answers?”, Management International Review, Vol. 47, N° 3, p. 307-317

- Goerzen, Anthony; Beamish, Paul W. (2003). “Geographic scope and multinational enterprise performance”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 24, N° 13, p. 1289-1306.

- Guillèn, Mauro F. (2002). “Structural inertia, initiation, and foreign expansion: South Korean firms and business groups in China, 1987-95”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol 45, N° 3, p. 509-525.

- Hallsworth, Alan G. (1992). “Retail internationalization: contingency and context?”, European Journal of marketing, Vol. 26, N° 8-9; p. 25-34.

- Han, Mary (2005). “Towards strategic ambidexterity: The nexus of pro-profit and pro-growth strategies fort he sustainable international corporation”, Paper submitted to the JIBS Frontier Conference, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

- Hannan, Michael T. (1998). “Rethinking age dependence in organizational mortality: logical formalizations”, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 104, N° 1, p. 126-166.

- Hannan, Michael T.; Freeman, John (1984). “Structural inertia and organizational change”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 49, N° 2, p. 149-164.

- Hannan, Michael T.; Carroll, Glenn L.; Dobrev, Stanislav D.; Han, Joon (1998). “Organizational mortality in European and American automobile industries, Part I: revisiting the effects of age and size”, European Sociological Review, Vol 14, N° 3, p. 279-302.

- Harrigan, Kathryn R. (1988). Strategic alliances and partner asymmetries. p 205-226 in Contractor Farok J.; Lorange, Peter. Cooperative strategies in international business. Lanham, MA: Lexington Books.

- Hennart, Jean-François (1982). A theory of multinational enterprise. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan press, 216p

- Johanson, Jan; Mattson, Lars-Gunnar (1988). “Internationalization in industrial systems: a network approach”, p. 287-314, In Hood, Neil; Vahlne, Jan-Erik, (Eds), Strategies in Global Competition : Croom Helm, New York, 395p.

- Johanson, Jan; Vahlne, Jan-Erik (1977). “The internationalization process of the firm - a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments”, Journal of International Business Studies, Summer-Spring: 23-32.

- Johanson, Jan; Vahlne, Jan-Erik (1990). “The mechanisms of internationalization”, International Management Review, Vol. 7, N° 4, p. 11-24.

- Johanson, Jan; Vahlne, Jan-Erik (2009). “The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 40, N° 9, p. 1411-1431 .

- Johanson, Jan; Wiedersheim-Paul, Finn (1975). “The internationalization of the firm – four Swedish cases”, International Marketing Review, Vol. 12, N° 3, p. 305-322

- Jones, Marian V. (1999). “The internationalization of small high technology firms”, Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 7, N° 4, p. 15-41.

- Jones, Marian V; Coviello, Nicole E. (2005). “Internationalisation: conceptualising an entrepreneurial process of behaviour in time”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 36, N° 3, p. 284-303.

- Knight, Gary; Cavusgil, Tamer S. (1996). “The born global firm: a challenge to traditional internationalization theory”, Advances in International Marketing, Vol 8, N° 1, p. 11-26.

- Knudsen, Thorbjørn; Madsen, Tage Koed (2002). “Export strategy : a dynamic capabilities perspective”, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol 18, N° 4, p. 475-502.

- Kogut, Bruce (1992). “National organizing principles of work and the erstwhile dominance of the American multinational corporation”, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 1, p. 285-317.

- Kumar, Manmohan S. (1984). “Comparative analysis of UK domestic and international firms”, Journal of Economic Studies, Vol. 11, N° 3, p. 26-42.

- Li, Jiatao (1995). “Foreign entry and survival: effects of strategic choices on performance in international markets”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 16, N° 5, p. 333-352.

- Lu, Jane W.; Beamish, Paul W. (2001). “The internationalization and performance of SMEs”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 22, N° 6/7, p. 565-586.

- Lu, Jane W.; Beamish, Paul W. (2004). “International diversification and firm performance: the S-curve hypothesis”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, N° 4, p. 598-609.

- Luo, Yadong; Rui, Huaichuan (2009). “An ambidexterity perspective toward multinational enterprises from emerging economies”, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 23, N° 4, p. 49-70.

- Luo, Yadong, Tung; Rosalie L. (2007). “International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, N° 4, p. 481–498.

- Madhok, Anoop (1996). “Know-how-, experience- and competition-related considerations in Foreign Market Entry: an Exploratory Investigation”, International Business Review, Vol. 5, N° 4, p. 339- 366.

- Madsen, Tage Koed; Rasmussen, Erik.S.; Servais, Per (2000). “Differences and similarities between born globals and other types of exporters”, p. 247-265. In Yaprak, A. & Tutek, J. (Eds). Globalization, the Multinational Firm, and Emerging Economies: Advances in International Marketing, JAI/Elsevier, Amsterdam

- Madsen, Tage Koed; Servais Per (1997). “The internationalisation of born globals: an evolutionary process?”, International Business Review, Vol. 6, N° 6, p. 561-583.

- March, James (1991). “Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning”, Organization Science, Vol. 2, N° 1, p. 71-87.

- McDougall, Patricia .P.; Shane, Scott; Oviatt, Benjamin M. (1994). “Explaining the formation of international new ventures: the limits of theories from international business research”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol 9, N° 6, p. 469-487.

- McNaughton, Rod B. (2000). “Determinants of time-span to foreign market entry”, Journal of Euromarketing, Vol 9, N° 2, p. 99-112.

- Montgomery, Cynthia A.; Thomas Ann R. (1988). “Divestment: motives and gains”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 9, N° 1, p. 93-97.

- Oviatt, Benjamin M.; McDougall, Patricia P. (1994). “Toward a theory of International New Ventures”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol 25, N° 1, p. 45-64.

- Oviatt, Benjamin M.; McDougall, Patricia P. (1995). “Global Start-ups: entrepreneurs on a worldwide stage”, Academy of Management Executive, Vol 9, N° 2, p. 30-44.

- Oviatt, Benjamin M.; McDougall, Patricia P. (2005). “Defining international entrepreneurship and modelling the speed of internationalization”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 29, N° 5, p. 537-553.

- Pangarkar, Nitin (2008). “Internationalization and performance of small – and medium-sized enterprises”, Journal of World Business. Vol 43, N°4, p. 475-485.

- Penrose, Edith (1959). The Theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford: Blackwell, 304p. Planet Retail: http://www.planetretail.net

- Podolny Joel M. (1993). “A status-based model of competition”, American Journal of Sociology, Vol 98, p. 829-872.

- Prange, Christiane; Verdier, Sylvie (2010). “Dynamic capabilities, internationalization processes and performance”. Journal of World Business , in press. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2010.05.024

- Raisch, Sebastian; Birkinshaw, Julian (2008). “Organizational ambidexterity: antecedents, outcomes, and moderators”, Journal of Management, Vol. 34, N° 2, p. 1-35

- Rennie, Michael W. (1993). “Born global”, McKinsey Quarterly, Vol. 4, p. 45-52

- Reuber, Rebecca A.; Fischer, Eileen (1997). “The influence of the management team›s international experience on the internationalization behaviors of SMEs”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 28, N° 4, p. 807-825

- Rothaermel, Frank .T.; Deeds, David L. (2004). “Exploration and exploitation alliances in biotechnology: a system of new product development”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 25, N° 3, p. 201-221.

- Sapienza, Harry J.; Autio, Erkko.; George, Gerard; Zahra, Shaker A. (2006). “A capability perspective on the effects of early internationalization on firm survival and growth”, Academy of Management Review, Vol 31, N° 4, p. 914-933.

- Sapienza Harry J.; De Clercq Dirk; Sandberg William (2005). “Antecedents of international and domestic learning effect”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 20, N° 4, p. 437 -457

- Tallman, Stephen; Li, Jiatao .T. (1996). “Effects of international diversity and product diversity on the performance of multinational firms”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, N° 1, p. 179-196.

- Tallman, Stephen; Fladmore-Lindquist, Karin (2002). “Internationalization, globalization, and capability-based strategy”, California Management Review, Vol. 45, N° 1, p. 116–135.

- Treadgold, Alan (1988). “Retailing without frontiers, the emergence of transnational retailers”, Retail & Distribution management, Vol. 16, N° 6, p. 8-12

- Vermeulen, F. & Barkema, Harry G. (2002). “Pace, rhythm, and scope: process dependence in building a profitable multinational corporation”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 23, N° 7, p. 637-653.

- Wagner, Hardy (2004). “Internationalization speed and cost efficiency: evidence from Germany”, International Business Review, Vol 13, N° 4, p. 447-463.

- Williams, David E. (1992a). “Motives for retailer internationalization: their impact, structure and implications”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol 8, N° 3, p. 269-285.

- Williams, David E. (1992b). “Retailer internationalization: an empirical inquiry”, European Journal of marketing, Vol 26, N° 8-9, p. 8-24.

- Zahra, Shaker (2005). “A theory of international new ventures: A decade of research”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol 36, N° 1, p. 20-28.

List of figures

Figure 1

Internationalization Age

Figure 2

Internationalization Speed

Figure 3

The two-ways interaction effects

List of tables

Table 1

Incremental vs. new ventures internationalization processes

Table 2

A matrix of internationalization patterns with examples from retailers

Table 3

A matrix of internationalization patterns with retailers’ performance