Abstracts

Abstract

Chinese organizational behavior is the product of history. In this paper, we propose an introduction to the philosophical bases of Chinese behavior. This introduction is contextualized and historically situated; then compared to Western thinking to ensure that its value for organizations is understood. We examine first the dominant Chinese philosophy schools and decode their possible meaning for managing organizations. In particular, such issues as organizational structure, leadership, emotions and time-orientation are discussed in reference to traditional values. The paper’s conclusion suggests that Chinese firms’ behavior can be better understood and studied by looking at their philosophical and historical roots.

Keywords:

- Chinese philosophies,

- Strategic management in China,

- Confucianism-Taoism,

- History and strategic management,

- History-based leadership,

- Time-orientation,

- Emotions and management

Résumé

Le comportement organisationnel chinois est le produit de l’histoire. Dans cet article, nous développons les bases philosophiques du comportement chinois, en prenant en compte le contexte et l’histoire. Ensuite, nous comparons à la pensée occidentale pour révéler les enseignements pour les organisations. Les grandes écoles philosophiques sont discutées pour révéler leur signification pour le management des organisations. Nous abordons notamment les questions de structure organisationnelle, leadership, émotions et orientation-temps, en référence aux valeurs traditionnelles. La conclusion insiste sur l’idée que le comportement d’entreprises chinoises peut être mieux compris et mieux étudié en prêtant attention à leurs racines philosophiques et historiques.

Mots-clés :

- Philosophies chinoises,

- management stratégique en Chine,

- Confucianisme-Taoisme,

- Histoire et management stratégique,

- histoire et leadership,

- orientation-temps,

- émotions et management

Resumen

El comportamiento organizacional chino es el producto de la historia. En el presente trabajo, proponemos una introducción a las bases filosóficas del comportamiento chino. Esta introducción se contextualiza y se sitúa históricamente; a continuación, se compara con el pensamiento occidental para asegurarse de que se entiende su valor para las organizaciones. En primer lugar examinamos las escuelas de filosofía chinas dominantes y desciframos su posible significado en cuanto a la gestión de las organizaciones. En particular, se discuten cuestiones tales como la estructura de la organización, el liderazgo, las emociones y la relación con respecto al tiempo en referencia a los valores tradicionales. La conclusión del trabajo propone que se entienda y se estudie mejor el comportamiento de las empresas chinas examinado sus raíces filosóficas e históricas.

Palabras clave:

- Filosofías chinas,

- Gestión estratégica en China,

- Confucianismo-Taoísmo,

- Historia y gestión estratégica,

- Liderazgo basado en la historia,

- Relación con respecto al tiempo,

- Emociones y gestión

Article body

For most Westerners, China is a paradox; it continues its communist ideology and macro-control, while allowing a “socialistic free market” economy. It is moving from the dependence on a rural agrarian economy to a rapidly emerging urban and industrial economy, with a fast growing middle class. It is a society where traditional culture exists side by side with post-modern Western culture. While China has historically insulated its institutional framework from Western influence; today it allows measured Western incursion, but within a traditional Chinese governance system.

Chinese business behavior is also paradoxical. Though market potential and business opportunities in China are appealing, foreign investors perceive that they are facing a lot of uncertainty. In particular, the business institutional environment is perceived to be unstable (Child & Rodrigues, 2004), and Chinese business and customer behavior (BCG, 2006; Chen, 2001) is poorly regulated and hard to predict. Experience highlights that doing business in China is a struggle for Western executives, and Chinese business people are seen as lacking credibility (WSJ, 2006) and can hardly be trusted (Graham & Lam, 2003). They use deceptive tactics and tricks, leading to a generally disorderly and sometimes chaotic business environment. To decode such a behavior has been described as a challenge for companies hoping to profit from this huge new market (Chen & Vishwanath, 2005).

Studies suggest a deep misunderstanding of Chinese by Westerners, stemming perhaps from “a lack of cultural knowledge” (Chen, 2001). Misunderstanding runs so deep that, for some, Chinese are “baffling” and Chinese behavior generally deceptive. Yet, Chinese are also seen as long-term oriented. Their behavior is value-centric and emphasizes collective rather than individual good (Hofstede, 2003). And traditional teachings (Schumacher, 1967) advocate frankness, honesty, trustworthiness, loyalty, righteousness, harmony-seeking and balance-keeping, the so-called “mid-way” behavior (Confucius, 1971). When compared to perceived behavior, these values are at the center of a real paradox.

Chinese, on their part, do not see deception and value-centric behavior as contradictory. Guided by a Chinese mindset and historical savvy, they look at them as the two sides of Chinese strategic thinking and approaches to life and achievements. China is unusual in many respects. It is widely diverse yet has always been dominated and united by a strong civilisation, based on common history, philosophy and institutions. Chinese history and ancient philosophy in particular seem to be the most critical common good to which Chinese refer constantly to understand their own behavior. Chinese often say “Consider the past and you will know the present” (Samovar, Porter and Stefani, 1998). History is a mirror and a reference to shape strategy and behavior.

Chinese business mindset takes the market as a battlefield (Chu, 1991; Fang, 2006; Luo, 2001b; Tung, 1994). Perhaps instinctively, Chinese business elites practice strategies and tactics that are part of their history, and they are able to decode their local competitors’ business behavior because they are cognizant of history and philosophy. Samovar et al. (1998) argued that the nature of Chinese core values is largely the product of thousands of years of living and working together. Yet, the extant literature on strategy rarely acknowledges the relationship of these ancient Chinese sources to modern corporate strategic thinking.

In this paper, we propose to: 1) undertake a systematic review of values and norms embedded in philosophy and history and discuss how these might affect Chinese behavior; and 2) examine how Chinese traditional thinking could be related to today’s Strategic Management Studies. This paper intended contribution is therefore threefold: First, it introduces strategic management scholars to Chinese philosophy and discuss its importance as an additional lens, when trying to understand Chinese behavior; second, it hypothesizes possible links between philosophy and firm strategic behavior; and finally provides an example of how institutions, in particular cognitive-based ones, could have a subtle effect on behavior, allowing the co-existence of conflicting values and their resolution when needed.

To do that, in Part I, we propose a brief introduction to the dominant schools of ancient Chinese philosophies, in which Chinese core values and behavior norms are embedded, and in which Chinese strategic thinking is rooted. A better understanding of the traditional school of thinking then helps, in Part II, discussing how these ancient philosophies could be related to specific behavior. Finally, in Part III, we try to justify hypotheses of possible links between Chinese philosophical thoughts and modern strategic management, in particular in such areas as: 1) the Chinese conceptions of organization, 2) the Chinese conception of strategy, and 3) specific issues of strategy and management in China. We discuss these ways of looking at Chinese behavior in Part IV, and in conclusion, we make suggestions for future research and for practitioners engaged in China-based operations.

Chinese basic philosophies

The earliest Chinese philosophical thinking is associated with the Yi Jing (《易经》 the Book of Changes), dated back to more than 2500 years ago. For Western schools of historical thoughts, the Yi Jing is somewhat an ancient compendium of divination. However, Chinese generally believe that the legendary author of this book, Fu Xi (伏羲), is the founding father of Chinese philosophy. Later, different philosophical schools emerged, and their scholars described themselves as disciples of Yi Jing. These schools advocate different, sometimes even contradictory, doctrines and reflections about human nature and life. But, for leaders and elite groups in China, these schools are complementary to one another and are used as guides for organizational and individual life. Today, it is likely that some of these schools have shaped China’s core values; others provided thinking and behavioral norms. In what follows, we offer brief introductions to some selected schools, believed to be the most influential in Chinese philosophical thoughts -- Confucianism, Taoism, Strategist school, Historical school, Legalism and Mohism.

The most influential schools of Chinese philosophy

Confucianism covers the fields of ethics and politics, emphasizing personal and governmental morality, social relationships, justice, traditions, and sincerity. Confucianism has been one of the dominant philosophical schools in China. The Analects of Confucius (《论语》 written around 450 B.C.) advocate: 1) Benevolence and Humanity (仁爱); 2) Loyalty and Righteousness (忠义); 3) Filial behavior (孝), 4) Ritual (礼); 5) Honesty (诚) and Trustworthiness (信); and 6) People Orientation (人本). These are considered as “the Chinese core values”. For Confucius, human nature has an innate tendency towards goodness (人性善), and this leads to the concept of “Universal Love (兼爱)”. However, bad environments tend to corrupt good intentions. Therefore, to avoid that men need to proactively take action and establish a society of benevolence with a certain level of social order and hierarchy. The concept of social hierarchy later became the most important element in the Chinese governance institutions. Nevertheless, the love of people goes beyond this hierarchy to reach the ultimate goal of a benevolent society. To a leader: “the people are the most important; next is the country; least is the ruler himself (民为贵,社稷次之,君为轻)”, and to the people: “do not impose upon others what they would not choose themselves (己所不欲,勿施于人).” Loyalty is an unconditional value, but should be rooted in Righteousness (义), a behavior guided by an innate sense of right and wrong. A disloyal behavior can be legitimized if it is righteous. In practice, Confucius advocates: “Rid of the two ends, take the middle (中庸),” a path to reach some satisfactory middle ground, towards a society of benevolence.

While Confucianism provides detailed values and behavioral norms, Lao Tzu’s “Tao” takes on the most abstract meanings: “an ultimate rule or truth that encompasses the entire universe but which can hardly be described or felt (道可道,非常道)”. Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching (《道德经》 written around 500 B.C.) advocates non-action (无为), the strength of softness (柔弱胜刚强), respect of nature and spontaneity (道法自然), and relativism (所倚所伏). While Confucianism advocates proactive behavior to correct the injustice within society, Taoism takes a non-action “laissez-faire” perspective. It argues that it is an undeniable fact that human beings attempting to make the world better, ends up making it worse. The world would be better if everybody takes care of his own business properly, and it is better to strive for harmony without the ruler’s intervention (Kirkland, 2004; Van Norden & Ivanhoe, 2005). From a Taoist perspective, life is a form of subjectivity, balanced by a kind of sensitive holism. The whole universe is seen as a self-balancing natural system. Therefore, the world does not need any governance; and should not be governed. Good order emerges spontaneously when things are let alone (Rothbard, 1990).

At the individual level, Taoism advocates that simplicity (简朴) and humility (谦卑) are key virtues, and often are incompatible with selfish actions. At the political level, the concept of “non-action” means avoiding such circumstances as war, harsh laws and heavy taxes. Taoism was more influential than Confucianism in the first 50 years of the Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 220 A.D). It even became the state ideology, and coincided with the highest level of prosperity in the early Chinese history.

Ancient Chinese scholars argued that Sun Tzu’s Art of War was highly influenced by the Taoist school. If we translate the original title (《孙子兵法》 written around 500 B.C.) directly from Chinese into English, it is: Sun Tzu’s Art of Strategy (Wing, 1988). The book provides abstract strategic principles about: estimating (chapter 1), planning (chapter 3), positioning (chapter 4), directing (chapter 5), weakness and strength (chapter 6), building variation and adaptability (chapter 8), motivating people (chapter 9) and using intelligence (chapter 13). Sun Tzu’s strategy is always analysis-based, so you need to “know yourself and know your opponent (知己知彼).” To formulate an effective strategy, unique and inimitable (Wing, 1988), it is necessary to evaluate five critical dimensions: 1) Your values and norms: a set of well-articulated and shared organizational goal (道:令民与上同意), 2) the ruling institution (天), 3) the competition (地), 4) Human resources available (将) and 5) your governance system (法)[1].

“To subdue the enemy without fighting is the supreme excellence (不战而屈人之兵,善之善者也)”, and the main objective. This is the great legacy of the strategist school; and “for a great leader … war is only a choice when he does not have any other choice (圣人之用兵……不得已而用之)” (Cao, 1999). Therefore the greatest leaders’ intelligence and war skills will remain obscure, because they will never conquer any place by using force (故善用兵者,无智名,无勇功) (Wei, 2009). This is in line with the Taoism argument that “the greatest leader is the one that is barely noticeable (太上,不知有之).” Sun Tzu’s work is the essence of Chinese strategist school. The book is today a strategic management “Bible” for business people in China (Tung, 1994).

Sima Qian (司马迁: 145 – 86 B.C) is regarded as the father of Chinese historiography because of his masterpiece, Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》, written in 109 – 91 B.C.), in which he recounted Chinese history from the time of the Yellow Emperor[2] (黄帝: about 3000 – 2600 B.C.) until his time. The book provides the very first systematic general historical record for the whole of China, presenting history in a series of biographies. Sima Qian was liberal and objective. As in modern history, he saw History as not only facts, but also interpretations (Carr, 1961). He did not hesitate stating his own opinions, and interpretations, sometimes criticizing with emotions the emperors’ policies and legitimacy. He critically used stories passed on from antiquity as part of his sources, balancing reliability and accuracy of the existing records. The purpose was not only to record historical facts, but also to use history as a textbook from which people can learn. History is a mirror, as Emperor Li Shimin[3] stated: “take copper plate as a mirror, put clothes in a proper manner; take people as a mirror, understand gain and loss, take history as a mirror, master (the nation’s) rise and fall (以铜为鉴,可以正衣冠;以人为鉴,可以明得失;以史为鉴,可以知兴替).”

Thus, all history is not only contemporary history (Croce, 1981), but also a mirror that can help “to identify the future which has already happened” (Drucker, 2000). Chinese often look in history to find a situation or scenario similar to the one that they are facing, in search for clues and inspiration and for the related skills and tactics used successfully by historical figures. History is both a medium which transfers core Chinese values and behavioral norms, and a reference framework that guides people’s behavior. Sima Qian’s work is comparable to Herodotus and his Histories (Martin, 2009), and the contributions to Chinese philosophy and thinking are as significant as Voltaire’s and Hegel’s to the Western world.

Legalism was one of the main philosophical schools 2000 years ago. In fact, it was the state ideology of the first emperor of China, Ying Zheng (秦始皇嬴政: 259 – 210 B.C.), who unified the entire China in 221 B.C for the first time in Chinese history. Legalism is a utilitarian political philosophy that does not address general questions like the nature and purpose of life. Unlike Confucianism, it postulates that human nature is evil (人性恶) and to prevent chaos, control through laws is needed. Legalism focuses on strengthening the ruler’s political power using “laws” (法), seen as tactics (术) to build legitimacy (势). The “law” referred to “stringent rules and harsh punishments (严刑峻法)” under autocracy or totalitarianism (Creel, 1953). Though rarely advocated by leaders, legalism is probably more influential in Chinese society, especially among Chinese political and business leaders, than were in the West the teachings of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469 – 1527) in The Prince.

Micius (墨子: about 470 – 391 B.C.) was the first philosopher to openly challenge Confucianism. In contrast to Confucius, Mohism morality emphasizes self-reflection and authenticity rather than obedience to hierarchy and ritual. Mohism proposes that people are capable of changing circumstances and directing their own lives. Mohism is at the origins of meritocracy (任人唯贤), and states for example that if a leader is incapable of ruling, people have the right to downgrade him. Mohism also promotes a philosophy of impartial love and caring (博爱) – a person should care equally for all other individuals. Instead of preaching obedience to fatuous rulers as Confucius did, Micius proposes that people have the right to fight for benevolence, and for him Righteousness means: building the world as a commonwealth shared by all (天下为公). This utopian belief is similar to Plato’s (428 – 348 B.C.) (Bobonich, 2002; Laks, 1991), and can be compared to more recent definitions of a “moral commonwealth” (Selznick, 1990). Mohism’s influence over Chinese revolutions in both ancient and modern times is seen as important.

Integration: A Chinese mix of philosophies

In Chinese history, philosophy has always been moulded to fit the prevailing schools of thought. The Chinese schools of philosophy can be both critical, and yet relatively tolerant of one another. At a specific period of time, one particular school may prevail and be officially adopted by the ruling coalition as ideology; however, all schools have continued to co-exist for most of the time. A few tried to ban competing schools, but none was successful. Because of the everlasting debates and competition, they generally have cooperated and shared ideas, which they would usually incorporate into their own. For example, the concept of love: 1) benevolent love (仁爱), 2) universal love (兼爱), and 3) impartial love (博爱), and the love of people, or people-orientation, are fundamentally the same. In fact, even the strategist school argues that “Conquer a city is not a good strategy, win the heart of people is the supreme strategy (攻城为下,攻心为上) (in Thirty-Six Stratagems 《三十六计》)” (Luo, 2003).

In fact, each school is only a part of a jigsaw puzzle. To understand Chinese people, one needs to look at the broader picture. For example, Taoism served as a rival to Confucianism for thousands of years; however, both are schools of active morality, the relationship is inevitable and interwoven with added richness. This rivalry is reconciled by Chinese with a proverb: “practice Confucianism on the outside (behavior), Taoism on the inside (belief and attitude).” For Chinese, Confucianism and Taoism are two sides of a coin. For a leader, the non-action “laissez-faire” (Taoism) is actually a strategic choice of action (Confucianism), therefore, Lao Tzu argued that “the greatest leader is the one that is barely noticeable by the people (太上,不知有之)” for he is apparently not doing anything. This Taoism “laissez-faire” by a leader leads to “laissez-tout-faire” (无为无不为) by the people. Even if a leader chooses to act, Confucius also asserted that he must know when and how to “laissez-faire” (有所为,有所不为).

Taoism relativism helps Chinese to calm down when they succeed, and cheers them up when they fail: “Misery, by the side of which happiness is to be found; happiness, beneath which misery lurks (祸兮福之所倚,福兮祸之所伏)”. Then, Confucius encourages Chinese to “take action, even if you know it is impossible (知其不可而为之).” “Try your best, then accept the result as it is (尽人事以听天命)”, that is the survival key of the Chinese civilization.

While Taoism provides guidelines for one’s attitude, and Confucianism offers Chinese core values and behavioral norms, the strategist school sets proactive or reactive strategic principles for people to respond to difficult situations and to confront challenges, and the historical school provides historical experiences and lessons, with vivid illustrations and detailed tactic guidelines. Thus, for Chinese these schools are interdependent rather than contradictory. Both Lao Tzu and Confucius advocated humbleness and humility, therefore to keep a low profile: “he who knows does not speak (知者不言), and he who is intelligent and capable seems stupid (大巧若拙)” (Taoism). The strategic school’s interpretation is to disguise your strength and advantage: “feign incapability and show weakness (能而示之不能,用而示之不用)” (Confucianism) so as to “take action when least expected (出其不意)”. “To keep a low profile (韬光养晦),” as a national strategy in the international arena (Deng, 2004), has been China’s dominant diplomatic policy for the last three decades.

Furthermore, Confucianism social hierarchy and legalism law and rules provide the infrastructure for governance. So, power is always centralized, even though leaders always adopt Taoism suggestion “ruling a big nation is like cooking small fishes (治大国若烹小鲜)”, that is, only use mild heat, do not stir very much, and be cautious and respect your power. In addition, Mohism further reinforces the people-orientation concept of Confucianism. Not only should you respect the power in your hand, but also recognize and respect the power of the people. With Mohism perspective, Emperor Li Shimin once argued “Emperor is a boat, and people are water, which floats a boat, which sinks a boat (君舟也,民水也,水可载舟,亦可覆舟)”.

In conclusion, one can say that Chinese use a mix of these philosophies to make up their thinking and behavior. Taoism relates to Chinese life attitude and Confucianism to Chinese core values and behavioral norms. Strategic and historical schools offer guidelines to respond to specific situations in life. Confucian social hierarchy and legalism ruling system justify the centralized governance structure. Mohism sees the people as the nation’s foundations. For 2000 years, despite much social turbulence and many wars, Chinese core values have kept intact. But, we suggest that because of such a turbulent and violent history, Chinese behavior is often disguised through tactics and deceptions. In this paper, we do not intend to demonstrate such an assertion. Rather, in an inductive way, we point at some observations which make this a credible hypothesis.

Philosophy and specific behavior

There are important differences between Chinese and Western philosophies. Chinese philosophy takes a practical or pragmatic attitude; it does not concern itself much with the nature of a phenomenon, but about dealing with it (Moore, 1967). For example, Chinese do not really care much about what Heaven (天) or Tao (道) really are, but want to know more about the Will of Heaven, or the Power of Tao, and its impact on people’s action and behavior. In this sense, Chinese philosophy and history give primacy to issues of human life, rather than metaphysical conceptualization. First, Chinese philosophy is more direct (Zhang, 1946) in guiding people’s life and behavior. It has been argued that Western philosophy and culture are centered on intellect and reason, while Chinese philosophy and culture are centered on morality (Mou, 2009). Since Chinese people are used to talking about human life, character and behavior directly, philosophers do not feel necessary to justify their belief about human life by appealing to theories as required in Western philosophy (Ivanhoe & Van Norden, 2006). Second, Jiang (2009) argued that Chinese philosophy has no concept of substance. Therefore, it is not ontology-based (Cleary, 2009), and would rather be concerned with possible changes and relations rather than with ultimate essence or substance. On this basis, correlative thinking is seen as a characteristic of Chinese philosophical thoughts (Zhang, 1946). Third, Chinese philosophers use different modes of inference. Most importantly, Chinese logic uses analogy, and analogical thinking and arguments are the characteristic forms of inference (Moore, 1967). Although analogical arguments are often seen as inappropriate in Western philosophical thought (Russell, 1969), they are commonly valued in Chinese social and political argument and discussion. Chinese philosophers often use metaphors to argue a point (Zhang, 1946). Such metaphors , as, “Lure a tiger out of the mountain (调虎离山)”, and “Toss a brick to attract a piece of jade (抛砖引玉)” are typical of the Strategist school (Tung, 1994; Verstappen, 1999).

These differences may explain why many Western scholars and management practitioners have difficulties relating tactical skills or deception , to value-based competitive behavior. A possible explanation also lies in history. Most of the founding philosophers, such as Confucius, Lao Tzu and Sun Tzu were contemporary of one another. In the war era in which they lived, it was their different assumptions about society which led to different philosophical propositions. For example, Confucianism and Mohism took an idealistic perspective, while Taoism, Strategic and Historical schools took a realistic perspective to society and institutions. Thus, in the Art of War the author provides us not only with strategic principles, but also with vivid tactics and deceptive skills. In that time’s chaotic and destructive competitive environment, survival was first priority. At the time, no rule would be respected, and strategy was mostly “a game of deception (兵者,诡道也)”. Tactics and deceptive skills were highly valued by leaders as key capabilities and assets. According to the Art of War, in a given confrontation scenario, the effectiveness of stratagems relies on both psychological status and personality. As result, to reach the same goal, different strategies and stratagems may be reasonable. However, the most effective ones rely on the understanding of oneself and the competing organization’s leader as a human. Not only a strategy should be unique, so does its implementation. History plays a significant role not only in Chinese life and behavior, but also in Chinese strategic thinking and behavior. In our presentation of the dominant philosophies, we argued that most of the active principles, guidelines, tactics and stratagems could be traced bac k through thousands of years of Chinese history to real events which took place in the ancient times. For Chinese, history is not only the carrier of culture and values, but also a reference for action and behavioral norms.

History is a bridge between deceptive and value-based behavior

Scholars suggest that cultural misunderstanding is the cause of mistaken decoding of the value-vs.-deception behavior paradox in China (Chee & West, 2004; Ambler and Witzel, 2000; Chen, 2001), and history is the carrier of culture. Croce (1981), an historian and philosopher, argued that “all history is contemporary”, and the richness of history comes not from the facts, but from specific “historic scenarios” and interpretations (Carr, 1961). Since Chinese, according to the discussion of the basic philosophies, are often seen as taking history as a mirror and referring to it for inspiration and guidance, they try to look for those scenarios most relevant to behavior and decision making.

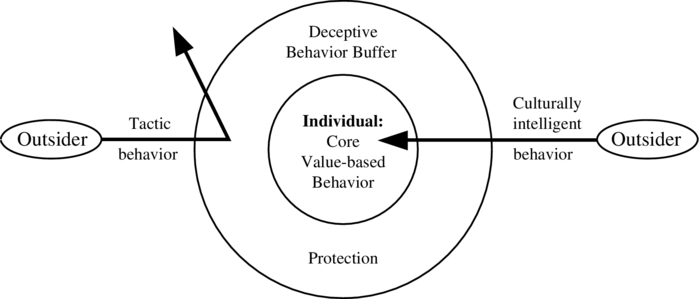

In our interpretations of the Strategic and Historical schools, deceptive tactics have three functions: 1) verifying others’ sincerity and identifying those really willing to cooperate from the others; 2) protecting oneself, by concealing strengths and weaknesses; and 3) delivering misleading information to “confuse and exhaust” rivals. We argue that these actually build a buffer zone, which is a barrier to the understanding of fundamental Chinese value-based behavior. When failing to recognize that there is a buffer and going beyond it, then age-old deceptive tactics could be used and may prevent any fruitful cooperation.

Figure 1

Deceptive Behavior and Value-based Behavior

Making the link with strategic management

Chinese strategic thinking cannot be captured easily as China is in the midst of old philosophy influences, but also of the strong impact of the socialist values and experience, and of the recent market economy dynamics. Socialism has not disappeared, but has subsided somewhat as the traditional planning system has been replaced, even in the public sector (Li Yan, 2010) by market-related management. However, we suggest that Chinese philosophy, as described earlier, is influential in Chinese decision-makers’ strategic thinking. It is not the only influence on managerial behavior, but our circumstantial observations of large Chinese company managers suggest that it is an important factor.

For example, Luo Guanzhong’s novel, The Three Kingdoms, built around a concatenation of old values, is generally seen by most Chinese as history. We conducted a simple experiment, asking30 managers about key characters and the representations that they were left with. 28 of the 30 managers described almost exactly what the book reports. The characters were familiar and their behavior as reported by Luo was known and seen as representative of good and bad behavior. This encouraged us to revisit our own research on Chinese management, which covered the Chinese beer industry, the transformation of the electricity industry and the strategic management of state-owned firms (references to be provided). This section and the next report some derived insights and hypotheses. It is important to emphasize that this exercise is inductive. We are not suggesting that all behavior in China is as described below. We are however arguing that the philosophies described earlier have an impact on some of managers’ behavior. This does not exclude for example that there is in China behavior which is more akin to socialistic behavior of the Mao Era, or to savage capitalism of the English laisser-faire era (Polanyi, 1945). The attempt here is suggestive rather than demonstrative. In his study of “The Human Group”, Homans (1950) argued that in the development of theory, it is legitimate to build on several, even unconnected, studies, as long as they are used with a single purpose in mind. However, a key principle in doing so is: “Enough will be included to support our theories, but nothing left out that is contrary to them....” (p. 20). In more recent writings about theory building the general sentiment is similar. Weick (2007) insists on the creative part of theory building; Eisenhardt (1989) suggests that it can be done using numerous cases; others insist on the systematic use of the data available. All of these, however, cannot do away with the dilemmas of inductive reasoning, that of its incompleteness (Ketokivi & Mantere, 2010).

What does ancient Chinese philosophy suggest for today’s general management? And how does it complement today’s strategic management thinking? In this part, we discuss the Chinese conceptions of organization, leadership and the importance of two issues that are salient in Chinese management: Time and emotions. These have been often seen as critical dimensions in general management (see in particular Simon, 1990), and are likely to be affected by ancient philosophy and related cognitive orientations.

Conceptions of organization: A dynamic tension between opposites

Western scholars see organizations from different perspectives (Jones, 2009; Scott, 1981, 2001), and provide a variety of theories. However, in China, because of the Chinese practical sense, as suggested by ancient philosophy, some scholars’ concerns is seen as being less about developing a theory, and more about dealing with phenomena (Moore, 1967). Therefore, original Chinese organizational theories does not seem to be a concern. Yet, Chinese have their own way of describing organizations and their operations. In ancient Chinese language (文言文), organization was written with two characters as 组织 = The first character (组) means “weave”, and the second (织) means “spin”. In this sense, an organization could be conceived as a large and open network; and the leader of an organization could be regarded as the weaver, with a broad view of the network, weaving and integrating (internal and external) forces, to achieve organizational goals. Therefore, an organization could be seen as an open system in which all variables and forces are interdependent and interacting, as goes the saying: “pull one string; the whole network reshapes (牵一发而动全身)”. To manage an organization is to manage such a dynamic system. In China, developing a strategy to compete has been described as a kind of Tao (Sun Tzu), and as in Drucker’s (1954) a work of art.

As discussed previously, harmony and balance-keeping are core values embedded in philosophy and history. A well-functioning organization works constantly to maintain harmony and balance, as illustrated in the Taiji Tu, frequently translated as the Diagram of the Great Ultimate (Robinet, 2008).

Figure 2

Taiji Tu: Diagram of the Great Ultimate

Although in Chinese philosophy, harmony and balance are the ultimate goal, Taoist teachings differ. For Lao Tzu, the ultimate organizational balance and harmony – the ultimate Tao – are impossible to achieve, and are not sought by Chinese leaders. According to Confucius, if the ultimate status were to be reached, decline will be the only direction ahead. Thus, the Chinese conception of an organization is a search for a balanced integration of Taoist relativism and Confucian proactivism. The Taiji Diagram, though the Taoism symbol of relativism, was actually proposed by Confucius, an advocate of proactive intervention. Furthermore, in Taoism, there is no clear positive and negative. Advantages and disadvantages are seen as interdependent and interactive. The Strategist school also proposes that strength and weakness can be transformed into each other when a proper strategy is setup. Confucian teachings prevent Chinese leaders and managers from taking extreme actions and initiatives. For example, to keep power balance in an organization, power disparity is always necessary. Centralization of the decision-making power is not contradictory with decentralization and empowerment. New proactive initiatives can be started from a policy of “laissez-faire”. Pluralism, within an organization, is often necessary to build a shared organizational goal and competitiveness (Pascale, 1990).

Structured leadership

The Historical school proposes three groups of managers, who are critical to successful operations: 1) leaders, 2) strategic advisers (high level officers around the leader), and 3) generals (operational officers). The Three Kingdom story illustrates these managers’ roles in strategy formation and implementation. As in Western classics (see for example Barnard, 1938), organizational leaders allocate resources, setup the organizational context (goals and directions, rule of games, core values and norms) to influence organizational members’ decision. Other officers had also specific tasks according to Chinese historiography. Advisers are often seen as the guardians of the system, in particular of values, rules of the game, behavioral norms. As expert thinkers, they provided guidance and stability to the whole system. They were generally the medium through which a leader had access to knowledge about strategy, technology, and “best practices.”

Strategic advisors first shaped then translated leader’s policies and decisions for divisional officers. They advised leaders about proper assignments to projects. The ancient philosophy literature shows that they were often highly committed to their leader and to their own “scholarly knowledge.” Although they did respect one another, they competed as well. They never hesitated debating amongst themselves in front of their leader, confronting ideas and rebuking each other’s arguments, proposing strategies, tactics and projects. They were rarely ideological in advocating proposals. Rather, they were practical problem-solvers.

More importantly, great leaders mentioned in early classics shared the governance of organizations with advisers and divisional officers, adopting a legalist governance stand. Advisers and divisional officers played a central role, preparing decisions and administering their implementation. As a result, they were also the conduit for negotiation and for compromise, when reason made these necessary. They provided leaders with clarifications, alternatives and rationales for action in new circumstances. In these early large and complex organizations, divisional managers setup their own strategies for the assigned tasks, and proposed their own strategic action plans for the specific situations that they encountered in battlefields. As a result of this division of managerial labour, management was specialized (Bower, 1972, 2007). Leaders succeeded only when they were able to identify and motivate the better advisers and divisional managers, and advisers and divisional managers acquired recognition only when associated with a leader who appreciated their services.

Even though the forms and the institutional context were different, it is interesting to point at similarities with modern strategic management literature (Bower & Gilbert, 2005; Bower & Gilbert, 2007), at least as far as managers and their roles are concerned.

Centralized decentralization

The centralization of power is one of the most obvious characteristic of China and Chinese organizations. Yet, Chinese philosophers proposed decentralization as a natural way of life. They did not see it as incompatible with strong central power. At first sight, at the national level, the centre has such a control on the choice of local government officers and large SOEs’ executives that it may seem laughable to talk about decentralization. But the fact is that throughout history an officer when selected enjoyed a lot of freedom. It is often said that “a general in the battle field does not have to follow the king’s remote instruction (将在外,君命有所不受).”

In large and complex Chinese organizations, leaders have relatively little knowledge and understanding of the activities that they are conducting. They can be visionary, but as argued earlier they still need to rely on their strategic advisers for good strategic decisions, and on their divisional managers for effective implementation. More interesting, this complex and dynamic system functions because there is little harsh punishment going around, as suggested by the Three-Kingdom sum. Except in unusual circumstances, where punishment may serve as an example or a strong signal, failing officers were simply recycled, and given other chances to show their value and talent. Our own observations of recent history are consistent with such a conclusion. As a result, individual initiatives, new ideas and innovations, kept the system overall healthy. The system breaks down mostly at the top, when leaders lose credibility or legitimacy.

We propose that, for Chinese, strategy is more about strategic implementation than formulation. From a macro perspective, we could observe that the economic reform has been guided by a vision set by Deng (2004), with an emphasis on the implementation process: “touching stones in water when wading across a river (摸石头过河)”. This perhaps explain why, for three decades, many socio-political and macro-economic policy changes have first been experimented with, before being gradually generalized (Morris, Hassard and Sheehan, 2002). The reforms were initiated as localized experiments which, only if successful, would spread (Peng, 2000). This is consistent with our own findings in the transformation of the electricity industry, and plays well with the traditional, pragmatic and results-oriented behavior.

In line with historical accounts, Chinese leaders prefer to ensure that enough preparation is provided for major moves. They are generally slow decision-makers and would probably feel uncomfortable with opportunistic and hasty behavior. The need to be prepared, and implement strategy properly, gives power to officers lower down the organization, and explains the tension between centralization and decentralization The centralized decision-making ensures the predominance of leaders’ goals and directions. Decentralized implementation leaves room for divisional manager to adjust their action plans to fit the realities in the field and better align with the ultimate goal.

Time at the heart of strategy

In China, strategy is guided by long term objectives, but local adaptation leads to incremental implementation. For example, the post-Mao Chinese economic reform has been frequently labelled as incremental and evolutionary (Prasad & Rajan, 2006). This feature highlights the importance of time in Chinese management traditions. The time dimension remains largely implicit and unexamined in organizational theories and strategic management (Albert, 1995; Mosakowski & Earley, 2000; Sastry, 1997). In contrast, the strategy school emphasizes time as a strategic management dimension (Ancona, Goodman, Lawrence and Tushman, 2001), Chinese leaders, as described in historical accounts, pay special attention to timing when releasing a critical decision or announcing policy shifts. Generals in battles also adjust the pacing and sequencing of implementation with internal dynamics and environmental contingencies.

The Strategy school proposed a three-pillar strategy model, frequently described by Western scholars as: 1) the Heaven (天时), 2) the Terrain (地利), and 3) the human-beings (Giles, 2007; McNeilly, 1996; Sawyer, 2007), or humanity (人和) (Foo, 2007, 2008). However, direct translation from ancient Chinese to modern English may have lost the essence of the original meanings (Wing, 1988); the three pillars can be more properly defined with today’s management terms as: 1) Institutions (天) and time (时), 2) Competitive environment (地) and advantages (利), and 3) Human resources (人) and internal harmony (和).

Chinese tradition emphasizes the value of time as a strategic management dimension and leaders use it as a critical tool. First, there is the horizon to which leaders mentally extend themselves when considering goals and actions to undertake (Nuttin, 1985). Future goals affect present behavior when there is a temporal integration that links the future with the present and when leaders believe they are able to influence the outcome (Nuttin, 1985).

With the lessons learned from history, Chinese managers take a long-term perspective in their strategy formulation and implementation processes. Decision makers, with a long term perspective may choose more patient approaches, emphasizing future and lasting outcomes, and close relationships among key actors (Das, 1987). Long term and short term temporal perspectives coexist and can be functional simultaneously; however, Chinese believe that a long term temporal perspective is vital for the organization’s growth and development process. Furthermore, in the Chinese context, concern with the past also has a strong effect on the present and the future (Samovar, Porter and Stefani, 1998); therefore, the temporal dimension is not only related to timing, pacing, and sequencing capabilities (Huy, 2001), but is also history dependent (Mezias & Glynn, 1993).

Figure 3

Three-pillar strategic model of the Art of War

Leaders and Emotions

Chinese elite members are taught to control themselves, especially not to expose their personal feelings and emotions to others (喜怒不行于色). A dignified, noble, even stoical behavior is seen as an indication of a person’s real value. Both lack of emotion and excessive emotion are frequently related to losing face. Confucius cautioned against taking extreme actions and positions in behavior; and Sun Tzu warned that a general should never take action with rage (Tung, 1994). However, emotion is an important element of behavior (Damasio, 1994; Ekman & Davidson, 1994), and it is a double-edged sword. In all cases, it has to be controlled and demonstrated in a proper manner.

In Chinese history and ancient philosophical teachings, the value of emotions in human interactions is often highlighted. Leaders valued emotion management skills (Huang, Law and Wong, 2006), and practiced emotion management. For ancient Chinese elites, emotion was regarded as a part of leadership and a key ingredient of charisma. Historical leaders were respected and admired when they were able to strike a delicate balance between the extremes. Most of the leaders who succeeded were liked and sometimes also disliked because they were also emotional about things. Leaders may be inspired by Heaven (天), but emotions are probably a great leader’s claim of being human (人) too. A legitimate leader should balance these two aspects (天人合一) delicately. In the Three Kingdom account, leaders cried openly when losing close friends and associates. They cried when others misbehaved. They applauded with energy and enthusiasm to their associates successes. Emotions are like an energy that motivates people and stimulates human relationships.

Today, both social psychologists and organizational scholars have gathered compelling empirical evidence that emotions spread across individuals in organizations (Barsade & Gibson, 1998; Brief & Weiss, 2002), especially in high-context (Hall, 1976; Samovar & Porter, 2004) collectivistic cultures (Hofstede, 2003), such as China’s. This skill at emotion exchange has also been noted by Chinese philosophers. Confucian philosophy highlights the importance of empathy for leaders and their decision-making, by arguing that leaders “do not impose on others what one would not choose for oneself (己所不欲,勿施于人) (Confucius, 1971);” and “treat with the reverence due to age the elders in your own family, so that the elders in the families of others shall be similarly treated; treat with the kindness due to youth the young in your own family, so that the young in the families of others shall be similarly treated (老吾老以及人之老,幼吾幼以及人之幼) (Mencius, 1971).”

Discussion and Conclusion

Although China is plural and one could find support for almost any theory, we believe history to remain important, and emphasize here its effects. In the early 1980s, Western management and organization theories were first introduced into the Chinese economic reform, and seen as attractive because they came with easily and clearly controlled and measured sets of variables. Also, a lot of “best practices” were introduced into Chinese firms, as modern and advanced international management experiences.

However, Chinese leaders are practical. Western theories and management practices did not always improve performance. This led to a comeback of century-old philosophical thoughts and strategic teachings, and step by step, traditional Chinese values and experiences were used alongside Western management theories and practices. for example the economic model is labelled: the Socialist Market Economy with Chinese Characteristics (Huang, 2008; Redding & Witt, 2008). This hybrid form of economy system is also a reflection of how Chinese ancient thinking could complement modern strategic thinking.

China is a country or rather a civilization that both fascinates and mystifies all who come in contact with it. The country’s cultures, history and realities are like a kaleidoscope that shows different pictures each time one peeks into it. In this paper, we presented leading ancient philosophical schools. While most Western scholars in strategic management focus mainly on the strategy or Confucian schools, each school is only a part of a dynamic philosophy which tries to stir away from extremes. In our discussion, we proposed three sets of dynamic equilibriums: 1) proactivism and relativism, 2) centralization and decentralization, and 3) rationality and emotion.

For example, we can use ambition-vs.-compromise as an illustration of proactivism and relativism. The Historical school proposes that ambition is a core value, while compromise is a skill to reach an ambition. The latter is the ultimate goal, supporting a leader’s legitimacy. In history, great leaders take proactive actions to reach their ultimate goals. However, to reach these goals, leaders are always ready to compromise, as promoted in the Art of War. According to Chinese philosophy, compromise is necessary to achieve an ambition (Tung, 1994). Therefore, for Chinese leaders, it is one of the skills they need to master, to avoid attack, maintain harmony and keep power balance, in order to “subdue the enemy without fighting”. Compromise is important when in a position of disadvantage, so as to disguise weakness, to conceal ambition, to build alliances, to acquire and accumulate resources. Thus, we argue that in Chinese tradition, long-term strategic goals require proactive actions, while short-term objectives are relative and can be adapted through compromise when necessary. In practice, the emphasis on compromise balances the Confucian proactivism and Taoist relativism. Whether a relationship is competitive or cooperative, compromise is also a means to develop and keep an ongoing long-term relationship. As proposed by Confucius: “Try your best, and then accept the result as it is”, in this sense, compromise is the ultimate survival strategy in the Chinese civilization.

The Chinese perspective sees all organizational elements as interdependent and interactive. Harmony and balance are ultimate goals to reach, but always relative. Strongly influenced by history, we proposed that the history-based conception of strategy balances centralization with decentralization, which is critical for leaders’ ability to deal with complexity. The decentralized strategic implementation gives an organization the flexibility to handle uncertainty. The centralized control of strategy formulation ensures consistency in the general direction of the organization as a whole. As a result, implementation can be guided to converge. This is what is indicated in Sun Tzu’s teaching that general values and principles need to be rigid (Confucian proactivism), while flexibility and adaptation must also be allowed in action plans (Taoist relativism).

We also proposed two specific issues related to history, which could contribute to a better understanding of today’s Chinese strategic management: 1) emotion is a management tool, and 2) the importance of a temporal dimension in which a long-term perspective dominates. To ensure cooperation and coordination, leaders take a long-term temporal perspective, especially when dealing with uncertainty and contentions. This long term temporal perspective gives operational managers room to perform, and introduce the top strategic vision more effectively into their relatively short-term and pragmatic implementation. The long term temporal perspective is the product of history, and the belief that “a general’s value should not be judged only on one battle’s winning and losing (不以成败论英雄).”

Emotion is another specific issue, which is new and understudied in strategic management (Huy, 2009). For too long, emotions have been concealed behind closed doors and ignored in favour of rationality and efficiency (Hill, 2008). They have been banished to the wings while cognition and rationality have monopolized central stage in the drama of management and leadership (Pitcher, 1995, 1999). Recently, Damasio (1994) proved that decision, judgment and rationality are vitally dependent on emotions. Without emotions, the decision-making process could rigidify, and be unable to learn from the past,(Pitcher, 1999).

The AIG case could be interpreted to illustrate the importance of these factors. AIG was the first foreign insurance company allowed to enter the Chinese market in 1992. The reason could be found in the past, when Shanghai was occupied by the Japanese army during World War II. Instead of retreating from China like many other foreign insurance firms, AIG continued its service and some of its senior managers in Shanghai were even imprisoned by the Japanese army. Chinese did remember AIG’s righteous behavior 50 years later, which won AIG a large first mover advantage. To be authorized to operate, other major players in this industry like New York Metropolitan, Japan Life and Sunlife had to wait another 8 years until China’s entry into the WTO in 2001.

The ancient Chinese encyclopaedia published in the 1st century, The Record of Rites (《礼记》) proposed seven basic emotions: joy, anger, sadness, fear, love, likeness and dislikeness (Russell, 1991). For Chinese these emotions are the carrier of a leader’s charisma and an effective tool to motivate people. It complements loyalty, trust, honesty and righteousness. Leaders’ emotional empathetic behavior is highly valued by society.

This paper introduces to traditional Chinese philosophy, and makes an attempt at relating it to management. We boldly proposed several theoretical hypotheses, which could be tested. For example, if barriers to doing business in China are often experienced, and loudly blamed for failure, as was the case of the international beer industry 10 years ago, would a patient show of willingness to cooperate lead to a drop in the traditional behavioral barrier? This relation can be tested, by looking at Western and Chinese firms’ experiences in China.

Most important, this paper makes the suggestion that history matters for a better understanding of Chinese management behavior. By studying Chinese history and philosophy, one can have a clearer understanding of the Chinese culture, core values and behavioral norms, and in the relationship with Chinese organizations adjust behavior accordingly.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Li Yan is an assistant professor of strategy at the Singapore Management University. Prior to that, he was CEIBS, China, associate director of executive education. He has designed and conducted numerous strategy-related executive programs and taught strategic management to several executive MBA groups. Li Yan has conducted extensive work on the intellectual history of China. His Ph.D. research focused on Strategic Management and Change in Large State-Owned firms. He conducted extensive field work on the Chinese electricity system and on the largest Chinese construction company. He holds a master’s of science degree and a Ph.D. from HEC Montréal.

Taïeb Hafsi is the Walter J. Somers Professor of international strategic management at HEC Montreal, the business school of the University of Montreal. His articles have been published in major management journal, and he wrote or edited thirty three books or monographies, dealing with strategic management and change in situations of complexity. He is the founder of International Management and has been the editor of the journal until 2004. He is a Research fellow of Economic Research Forum, a thinktank for the MENA region. He has received many awards and distinctions; in particular, he was awarded twice, in 1998 and in 2008, the Quebec Publishers’ best book award. He holds a Master’s of science degree in management, from the Sloan school of management, at the Massachussetts Institute of Technology, Boston, and a Doctorate in business administration, from the Harvard Business School.

Notes

-

[1]

Direct translation in military terms: 1) Moral values (道), 2) the weather and environment (天), 3) the battle field (地), 4) assign generals (将), and 5) discipline and law (法).

-

[2]

The Yellow Emperor, can arguably be dated back to 3000 B.C. – 2600 B.C. is the first ruler whom Sima Qian considers sufficiently established as historical to appear in the historical records, though most Western historian still think that it is only based on legendary stories.

-

[3]

Li Shimin (599 – 649 A.D.): the second Emperor of Tang Dynasty (618 – 907). Arguably, Li Shimin has been considered as the greatest and most respected Chinese Emperor by Chinese.

Bibliography

- Albert, S. (1995). Towards a theory of timing: An arachival study of timing decisions in the Persian Gulf War. Research in Organization Behavior, 17(1): 1 – 70.

- Allison, G., Zelikow, P. (1999). Essence of decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (2nd ed.): Longman.

- Ancona, D. G., Goodman, P. S., Lawrence, B. S., Tushman, M. L. (2001). Time: A new research lens. Academy of Management Review, 26(4): 645.

- Anonymous author. (1991). Thirty six strategems: The wiles of war (H. C. Sun, Trans.): Foreign Lanugage Press [Originally published in Ming Dynasty of China (1368 – 1644)].

- Barnard, C. I. (1938). The Functions Of The Executive. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Barsade, S. G., Gibson, D. E. (1998). Group emotion: A review from top and bottom. In M. A. Neale, E. A. Mannix (Eds.), Research on Managing Groups and Teams: JAI Press.

- BCG. (2006). Banking on China: Successful Strategies for Foreign Entrants: The Boston Consulting Group.

- Bobonich, C. (2002). Plato’s Utopia Recast: Clarendon Press.

- Bower, J. (1972). Managing the Resource Allocation Process: a Study of Corporate Planning and Investment: Richard D. Irwin Publishing

- Bower, J. (2007). From Resource Allocation to Strategy Oxford University Press.

- Bower, J. L., Gilbert, C. (2005). From Resource Allocation to Strategy: Oxford University Press.

- Bower, J. L., Gilbert, C. (2007). How Managers’ Everyday Decisions Create -- or Destroy -- Your Company’s Strategy. Harvard Business Review 85, no. 2, 85(2).

- Brief, A. P., Weiss, H. M. (2002). Organizational behavior: Affect in the workplace. Annual Review of Psychology, 53: 279 – 307.

- Cao, C. (1999). Eleven Strategists’ Annotations to the Art of War (十一家注孙子校理): China Press (中华书局).

- Carr, E. H. (1961). What is history: Ramdom House.

- Chen, A., Vishwanath, V. (2005). Expanding in China. Harvard Business Review, 83(3).

- Chen, M.-J. (2001). Inside Chinese business: A guide for managers worldwide: Harvard Business School Press.

- Child, J., Rodrigues, S. B. (2004). Corporate Governance in International Joint Ventures: Toward a Theory of Partner Preferences. In A. Grandori (Ed.), Corporate Governance and Firm Organization: Microfoundations and Structural Forms: Oxford University Press.

- Cleary, T. (2009). The Way of the World: Readings in Chinese Philosophy: Shambhala Publications Inc.

- Confucius. (1971). Confucian Analects, The Great Learning & The Doctrine of the Mean (James Legge ed.): Dover Publications

- Creel, H. G. (1953). The Totalitarianism of the Legalists. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Croce, B. (1981). Historical Materialism and the Economics of Karl Marx (Materialismo storico ed economia marxistica): Transaction Publishers (originally published in 1900).

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain: Putnam Publishing.

- Das, T. K. (1987). Strategic planning and individual temporal orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 8(2): 203 – 210.

- Deng, X. P. (2004). The Selected Works of Deng Xiao Ping: People’s Press.

- Descartes, R. (1960). Discourse on Method and Meditations (L. J. Lafleur, Trans.). New York: The Liberal Arts Press (Originally published in 1637).

- Drucker, P. (2000). The Ecological Vision: Reflections on the American Condition: Transaction Publishers.

- Drucker, P. F. (1954). The Practice of Management: HarperBusiness.

- Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J. (1994). The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions: Oxford University Press.

- Fan, Y. (2000). A classification of Chinese culture. Cross Cultural Management, 7(2): 3 – 10.

- Foo, C. T. (2007). Epistemology of strategy: some insights from empirical analyses. Chinese Management Studies, 1(3): 154.

- Foo, C. T. (2008). Cognitive strategy from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Chinese Management Studies, 2(3): 171.

- Giles, L. (2007). The Art of War by Sun Tzu (Special Edition): El Paso Norte Press.

- Graham, J. L., Lam, N. M. (2003). The Chinese Negotiation. Harvard Business Review, 81(10).

- Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond Culture: Anchor Books.

- Hill, D. (2008). Emotionomics: Kogan Page.

- Hofstede, G. (2003). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.): Sage Publication.

- Huang, G. H., Law, K. S., Wong, C. S. (2006). Emotional intelligence: A critical review. In L. V. Wesley (Ed.), Intelligence: New Research: Nova Science Pub Inc.

- Huang, Y. (2008). Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State: Cambridge University Press.

- Huy, Q. N. (2009). What does managing emotions in organization mean?: La Chaire de management stratégique international Walter-J.-Somers, HEC Montréal (Working paper).

- Ivanhoe, P. J., Van Norden, B. W. (2006). Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy: Hackett.

- Jiang, X. (2009). Enlightment Movement. In B. Mou (Ed.), History of Chinese Philosophy Routledge.

- Jones, G. R. (2009). Organizational Theory, Design, and Change: Prentice Hall.

- Kirkland, R. (2004). Taoism: The Enduring Tradition. London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Laks, A. (1991). Utopie Législative de Platon. Revue Philosophique, 4: 416 – 428.

- Lawrence, S. V. (2000). Beer Making: A thirst for success. Far Eastern Economic Review, 163(52): 106 – 108.

- Luo, G. (2003). The Three Kingdoms (M. Roberts, Trans.): Foreign Languages Press and University of California Press (Originally published in Chinese in 14th century).

- Martin, T. R. (2009). Herodotus and Sima Qian: The First Great Historians of Greece and China. Boston: Bedford and St. Martin’s.

- McNeilly, M. (1996). Sun Tzu and the Art of Business : Six Strategic Principles for Managers. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mencius. (1971). The Works of Mencius (James Legge ed.): Dover Publications.

- Mezias, S. J., Glynn, M. A. (1993). The Three Faces of Corporate Renewal: Institution, revolution and evolution. Strategic Management Journal, 14(2): 77.

- Moore, C. A. (1967). Chinese Mind: Essentials of Chinese Philosophy and Culture: University of Hawaii Press.

- Morris, J., Hassard, J., Sheehan, J. (2002). Privatization, Chinese-style: Economic reform and the state-owned enterprises. Public Administration, 80(2): 359 – 373.

- Mosakowski, E., Earley, P. C. (2000). A selective review of time assumptions in strategy research. Academy of Management Review, 25(4): 796 – 812.

- Mou, B. (2009). History of Chinese Philosophy: Routledge.

- Nuttin, J. (1985). Future time perspective and motivation: Theoryand research method: Leuven University Press/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Pascale, R. T. (1990). Managing On the Edge: How the smartest companies use conflict to stay ahead? : Simon and Schuster

- Peng, M. W. (2000). Business Strategy in Transition Economies Sage Publications, Inc. .

- Pitcher, P. (1995). Artists, Craftsmen and Technocrats: The Dreams, Relaties and Illusions of Leadership: Stoddart Pub.

- Pitcher, P. (1999). Artists, Craftsmen and Technocrats. Training and Development, 53(7): 30.

- Prasad, E. S., Rajan, R. G. (2006). Modernizing China’s Growth Paradigm. The American Economic Review, 96(2): 331.

- Redding, G., Witt, M. A. (2008). The Future of Chinese Capitalism: Oxford University Press.

- Robinet, I. (2008). Taiji Tu: Diagram of the Great Ultimate. In F. Pregadio (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Taoism A−Z: Routledge.

- Rothbard, M. (1990). Concepts of the Role of Intellectuals in Social Change Toward Laissez Faire. The Journal of Libertarian Studies, 9(2).

- Russell, B. (1969). The History of Western Philosophy: Touchstone (Originally published in 1946).

- Russell, J. A. (1991). Culture and the Categorization of Emotions. Psychological Bulletin, 110: 426 – 450

- Samovar, L. A., Porter, R. E. (2004). Communication Between Cultures (5th ed.): Thompson and Wadsworth.

- Samovar, L. A., Porter, R. E., Stefani, L. A. (1998). Communication Between Cultures (3rd ed.): Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Sastry, M. A. (1997). Problems and paradoxes in a model of punctuated organizational change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(2): 237 – 275.

- Sawyer, R. D. (2007). The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China. New York: Basic Books.

- Schumacher, E. F. (1967). Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered: Abacus.

- Scott, W. R. (1981). Organizations: Rational, natural, and open systems: Prentice-Hall.

- Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and Organziations (2nd ed.): Sage Publications Inc. .

- Simon, H. A. (1957). Administrative Behavior (2nd ed.): Macmillan.

- Simon, H. A. (1960). The New Science of Management Decision: Harper & Row.

- Tung, R. L. (1994). Strategic management thought in East Asia. Organizational Dynamics, 22(4).

- Van Norden, B. W., Ivanhoe, P. J. (2005). Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Vaughan, D. (1996). The Challenger Launch Decision: University of Chiago Press.

- Verstappen, S. H. (1999). The Thirty-Six Strategies of Ancient China. San Francisco: C.B. Inc.

- Wei, Y. (2009). The Selected Works of Wei Yuan: (魏源集) Zhonghua Book Company (中华书局) (Originally published in 19th Century).

- Wing, R. L. (1988). The Art of Strategy: A New Translation of Sun Tzu’s Classic The Art of War. New York: Broadway Books.

- WSJ. (2006). Retail’s One-China Problem: Immense, Fragmented Market Poses Problems for Wal-Mart, Other Chains Seeking to Expand, Wall Street Journal (Oct. 23, 2006).

- Zhang, D. (1946). Knowledge and Culture (知识与文化): Commerial Press (商务印书馆).

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Li Yan est professeur adjoint de stratégie à la Singapore Management University. Avant cela, il fut Directeur pour la formation exécutive à CEIBS, l’école de management de Shanghai en Chine, Il a conçu et réalisé de nombreux programmes en management stratégique et enseigné le management stratégique à de nombreux groupes de MBA exécutif. Li Yan a conduit un travail important sur l’histoire intellectuelle de la Chine. Sa thèse de Ph.D. portait sur le Management stratégique et le changement dans les grandes entreprises d’État en Chine. Il a notamment étudié en détail le système d’électricité en Chine et la plus grande société de construction. Il a un MSc et un Ph.D. d’HEC Montréal.

Taïeb Hafsi est professeur titulaire de la chaire Walter J. Somers de Management stratégique international à HEC Montréal. Ses recherches portent essentiellement sur la gestion stratégique des organisations complexes. Sur ces sujets il a écrit plus d’une centaine d’articles académiques ou professionnels et trente-trois livres ou monographies. Il est Research Fellow du groupe de réflexion Economic Research Forum, pour l’Afrique du Nord et le Moyen Orient. Il a été le fondateur de Management International et son rédacteur en chef jusqu’en 2004. Il a reçu de nombreux prix et distinctions. En particulier il fut deux fois récipiendaire, en 1998 et 2008, du prix du meilleur livre de gestion des éditeurs du Québec. Il détient un diplôme d’ingénieur en génie chimique, une maîtrise en management de Sloan School, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, ainsi qu’un doctorat de la Harvard Business School.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Li Yan es profesor adjunto de estrategia de la Universidad de Administración de Singapur. Antes, era director asociado para la educación ejecutiva en CEIBS, la Escuela de Administración de Shanghái, China. Ha diseñado y dirigido numerosos programas ejecutivos relacionados con la estrategia; en el MBA, ha dictado cursos de gestión estratégica a varios grupos ejecutivos. Li Yan ha llevado a cabo una amplia investigación sobre la historia intelectual de China. Para su tesis doctoral enfocó su investigación en la gestión estratégica y el cambio en las grandes empresas estatales. Llevó a cabo un extenso trabajo de campo sobre el sistema eléctrico de China y sobre la más importante empresa de construcción de este mismo país. Graduó con una maestría en ciencias de la gestión y un doctorado de HEC Montréal.

Taïeb Hafsi es profesor titular de la Cátedra Walter J. Somers de Gestión Estratégica Internacional en HEC Montréal, la escuela de negocios de la Universidad de Montreal. Sus ponencias se publicaron en las revistas de gestión más importantes. Escribió o editó treinta y tres libros o monografías, que tratan de gestión estratégica y de cambios en situaciones de complejidad. Es el fundador de Gestión Internacional y ha sido el editor de la revista hasta el año 2004. Es Research Fellow del Foro de Investigación Económica, un centro de estudio para la región MENA. Ha recibido numerosos premios y distinciones; en particular, fue premiado por los editores de Quebec en dos ocasiones, 1998 y 2008, para el mejor libro. Graduó con una maestría en ciencias de la gestión de la Sloan School of Management del Instituto de Tecnología de Massachusetts, Boston, y con un doctorado en administración de los negocios de la Escuela de Negocios de la Universidad Harvard.

List of figures

Figure 1

Deceptive Behavior and Value-based Behavior

Figure 2

Taiji Tu: Diagram of the Great Ultimate

Figure 3

Three-pillar strategic model of the Art of War