Abstracts

Abstract

How do Multinational Companies (MNC) learn to adapt to foreign markets and cultural differences ? We examine seven qualitative case studies of Brazilian MNCs which show that international experience and intercultural interaction, supported by geocentric international human resource strategies, are key factors in the organizational development of intercultural competence. Brazil appears to be a particularly interesting case, as certain characteristics of Brazilian culture, such as “estrangeirismo” and flexibility, seem to foster the development of intercultural competence.

Keywords:

- Brazil,

- culture,

- intercultural competence,

- intercultural learning,

- international experience,

- international human resource management,

- organizational learning

Résumé

Comment les entreprises multinationales apprennent-elles à s’adapter aux marchés étrangers et aux différences culturelles ? Sept études de cas qualitatives d’entreprises multinationales brésiliennes montrent que l’expérience internationale et l’interaction interculturelle, renforcées par des stratégies internationales de ressources humaines géocentriques, sont des facteurs clés du développement de compétences interculturelles organisationnelles. Le contexte du Brésil apparaît comme particulièrement intéressant, car certaines spécificités de la culture brésilienne, comme l’ « estrangeirismo » et la flexibilité, semblent accélérer le développement de compétences interculturelles.

Mots-clés :

- Brésil,

- culture,

- compétence interculturelle,

- apprentissage interculturel,

- expérience internationale,

- gestion internationale des ressources humaines,

- apprentissage organisationnel

Resumen

¿Cómo aprenden las empresas multinacionales a adaptarse a los mercados extranjeros y a las diferencias culturales ? Siete estudios de caso cualitativos de empresas multinacionales brasileñas enseñan que la experiencia internacional y la interacción intercultural, fortalecidas por estrategias internacionales de recursos humanos geocéntricas, son los factores clave del desarrollo de habilidades interculturales organizacionales. El contexto de Brasil aparece como especialmente interesante, pues ciertas especifidades de la cultura brasileña, como el « estrangeirismo » y la flexibilidad, parecen acelerar el desarrollo de habilidades interculturales.

Palabras clave:

- Brasil,

- cultura,

- habilidad intercultural,

- aprendizaje intercultural,

- experiencia internacional,

- gestión de recursos humanos,

- aprendizaje organizacional

Article body

The question at the core of International Business research is: “What determines the international success and failure of firms ?” (Peng, 2004). Intercultural competence (IC) is one of the resource-based advantages that influence the performance of international companies: the IC of individuals and organizations has a strong economic impact as seen in a multitude of situations such as, for example, expatriation (Black, 1990; Clarke & Hammer, 1995), customer-supplier relationships (Bush et al., 2001), offshore outsourcing (Ang & Inkpen, 2008) and effective interaction within MNCs (Ralston et al., 1995). Consequently, IC represents a source of strategic organizational competence for MNCs (Ang & Inkpen, 2008; Klimecki & Probst, 1993; Moon, 2010; Saner et al., 2000).

How do certain companies manage to develop such organizational IC while others do not ? Our understanding of the process- and implementation-related issues in international business is still limited, both in general (Peng, 2001) and more specifically for the subject of organizational intercultural competence (Ang & Inkpen, 2008; Moon, 2010). Adaptation to foreign local contexts and the integration of several cultures into the company’s culture is important for MNCs as they bridge large psychological, cultural and economic distances. More and more MNCs from emerging countries are confronted with these questions. Yet, research on MNCs from those countries remains quite scarce, and there is need for more resource-based-view work devoted to emerging economies (Peng, 2001).

This study aims to help close this knowledge gap by examining the ways in which MNCs acquire IC at an organizational level, and by empirically studying IC in the context of Brazil. An abductive research approach was adopted here, making repeated connections between theory and empirical data. Thus, after a review of existing literature, I will present empirical evidence drawn from seven case studies of Brazilian MNCs and then compare the results to further literature relevant to our findings.

Organizational learning of intercultural competence: from specialization to generalization of intercultural interaction

How do organizations acquire IC ? In other words, how do they learn to understand cultural differences underlying business interactions in foreign countries, and develop structures and strategies capable of dealing with them ? In order to answer these questions, we first need to turn our attention toward the definition of individual and organizational IC. As organizational competence is developed through organizational learning (OL), I will first review OL theory in general and then more specifically OL of IC. This theoretical framework is summarized in figure 1, the elements in the figure appearing in italics in the text.

Culture and Individual Level Intercultural Competence

Culture is a system of meanings shared by a group (Geertz, 1973), whether this group is a nation, an organization, or any other type of group with relatively stable membership over time. Individuals are influenced by the cultures of the different groups to which they belong, and the culture of a group (e. g. a nation) is far from being homogeneous and does not apply to every one of its members in the same way. Corporate cultures are shaped to a large extent by the national and regional culture in which they operate, influencing the management style, structures, and processes (D’Iribarne, 1989).

Many numerous contributions on individual IC have been made, but there is still no consensus on the definition (Bartel-Radic, 2009; Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009). For the purpose of this study, IC is defined as a person’s ability to understand the specifics of intercultural interaction and to adjust to these specifics by actively constructing an appropriate strategy for interaction (Bartel-Radic, 2009; Friedman & Berthoin-Antal, 2005). This definition of IC is very close to that of other terms proposed in related research, notably “cross-cultural competence” (Johnson et al., 2006), “cultural intelligence” (Earley & Ang, 2003) and “global mindset” (Levy et al., 2007).

IC largely depends on a person’s mental models (views of the other and of foreignness) which can evolve through an intercultural learning process including intercultural experience and critical reflection (Bartel-Radic, 2009). Intercultural learning improves intercultural sensitivity and replaces ethnocentrism with ethnorelativism (Bennett, 1986). “Acceptance” (of cultural differences), “adaptation” (to those differences) and “integration” (of these differences into one’s personality; development of a multicultural personality) are, according to Bennett, the successive levels of individual IC.

Organizational Intercultural Competence

Competence can be considered organizational when the combination of individual competences and dynamic interaction between them give birth to collective, embedded competences (Kusunoki et al., 1998). Research on organizational IC remains scarce, and as for individual IC, there is no agreement on naming related concepts. The terms of organizational IC (Bartel-Radic & Paturel, 2006; Klimecki & Probst, 1993) and “firm-level intercultural capability” (Ang & Inkpen, 2008; Moon, 2010) coexist. I consider that the terms can be used interchangeably because both refer to resource-based theory and IC or similar constructs. Drawing on the definition of individual IC, organizational IC can be defined as a company’s ability to understand the specifics of intercultural interaction and to adjust accordingly by actively constructing appropriate strategies. The IC of a firm resides not only in its managers’ individual cultural intelligence but also in the organization’s processes and routines and in its structure (Ang & Inkpen, 2008). Firm processes and paths - like cross-cultural coordination, learning and experience - are also a key to the development of organizational IC (Moon, 2010).

Organizational competences can give companies a competitive advantage if they are perceived as valuable by customers in several markets and are difficult to imitate and to substitute (Barney, 1991). Several authors claim that organizational IC is a strategic competence for MNCs (Ang & Inkpen, 2008; Klimecki & Probst, 1993; Moon, 2010; Saner et al., 2000). Present throughout the organization, in all of the company’s departments and activities, embedded organizational IC adds to the value perceived by customers and business partners and is difficult to develop and imitate.

Organizational competence cannot be observed directly but can be assessed through situations relying on effective international communication and management such as international strategy (i.e. success of internationalization strategies, success of international mergers and acquisitions) and intercultural interaction within and outside of the company (effective intercultural communication, constructive conflict management, achievements of global teams, etc.).

Organizational Competence and Learning

Individuals are usually seen as the basis of learning within organizations (Nonaka, 1994; Kim, 1993) but organizational learning (OL) is not simply the sum of each member’s learning (Fiol & Lyles, 1985). Like individual learning, OL includes cognitive and behavioral elements. These behavioral elements are often associated with a first level of learning whereas cognitive learning is considered as higher-level learning. The concept of single- and double-loop learning (SLL and DLL) developed by Argyris & Schön (1978) is the best-known model of OL, described as an ongoing process which involves action and cognition during which well-established knowledge and abilities are confronted with new ideas and possibilities.

What distinguishes actual OL from individual learning within the organization ? At the single loop level, learning becomes organizational when individual action turns into organizational action (Kim, 1993) through the creation or modification of organizational structures and routines. Cyert and March (1963) highlight the structural aspects of organizational action and learning. According to these authors, learning is an adaptation of the organization that is incorporated into procedures. Structure and procedures are thus elements of organizational routines, which “appear prominently and persistently in descriptions of organizational action” (Cohen & Bacdayan, 1994: 555). Routines are “distributed procedural memory”. Standardization and specialization within the organizational structure are two of such routines preserving organizational memory (Fiedler & Welpe, 2010). Organizational structure is “often seen as an outcome of learning” (Fiol & Lyles, 1995: 805) but it also determines OL processes.

At the double-loop “superior” level of OL, shared organizational mental models emerge (Kim, 1993). When learning is “embedded” within the organization through routines or shared mental models, it is considered to be OL from which organizational competence may arise.

Crossan et al. (1999) conceptualize OL as an ongoing process during which individual intuition is interpreted and integrated by the group, and institutionalized within the organization, triggering, in turn, individual intuition and so forth. Corporate culture, organizational strategy and structure, and the organization’s environment are contextual factors that influence OL (Fiol & Lyles, 1985). The first three are outcomes of learning as well as determining factors in the learning processes.

Organizational Learning Processes and Intercultural Competence

While few studies have been carried out on OL of IC, two papers have made key contributions to this area. Klimecki and Probst (1993) provide a theoretical application of Argyris and Schön’s SLL and DLL model to intercultural learning. Bartel-Radic and Paturel’s (2006) empirical and inductive study of the organizational learning of IC in a French MNC also points to the existence of two distinctive learning processes in this context, corresponding to SLL and DLL. By combining this literature with theory on international development of the firm, diversity and intercultural management, it is possible to construct a theoretical framework of OL of IC.

Single-loop learning of intercultural competence

An organization achieves SLL of IC when the organization is adapted to the intercultural context, and when the dominating values remain unchanged (Klimecki & Probst, 1993). In general, organizational SLL results in the creation or modification of organizational routines, procedures, and structures.

A polycentric organizational structure (Perlmutter, 1969), where “locals” are in charge of contacts with both customers and stakeholders on foreign markets, can be an effective way for MNCs to ensure IC at the single-loop level (Bartel-Radic & Paturel, 2006). A structure based on high local adaptation (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989) corresponds to a “specialization” of the personnel depending on their cultural origin and competence. When this kind of structure is deliberately designed by top managers, their individual IC (“cultural differences matter and we have to adapt the organization to them”) is institutionalized in the organizational structure. Another example is the adaptation of selling methods and communication styles to the local culture: the creation of routines and procedures raise learning from the individual to the organizational level.

Double-loop learning of intercultural competence

DLL of IC occurs when the managers and the personnel question the values, norms and basic assumptions that prevail within the organization (Klimecki & Probst, 1993) and when the organizational culture shifts towards higher “ethnorelativism” (Bennett, 1986). Organizations where DLL of IC has occurred show openness to cultural diversity and consider it as a resource for change and learning. Cultural differences are not discriminated against, but openly discussed and positively integrated into the work processes (Ely & Thomas, 2001). Organizations with this perspective show cultural diversity at every hierarchy level, especially among managers and top managers, and strategic intention to valorize cultural differences (Dirks, 1995). Companies with a “global mindset” have top managers who have a global perspective, managers who encourage knowledge sharing and international collaboration, companies that adapt their organization and their products to the characteristics of local markets (Schneider & Barsoux, 2003: 276).

Experience with intercultural situations is considered a key to learning, both at the individual and the organizational level (Taylor & Osland, 2003: 227). Within MNCs, expatriation can lead to a virtuous learning cycle if it starts with adequate strategic planning: expatriates should be sent abroad “for the right reasons” (Harris et al., 2003), which means following geocentric international human resource strategies (Perlmutter, 1969). In other words, when the aim of expatriation is to gain better knowledge of foreign markets, to train international executives and to develop a global organizational culture, then learning is much more likely to occur as a result.

Intercultural interaction within a company, which means contact between subsidiaries from different countries and working with intercultural teams, carries a particularly high potential for intercultural learning. Therefore, the diversity inherent in an MNC can be a positive factor for OL (Taylor & Osland, 2003). Relationships that are characterized by long-term, spontaneous interaction, shared context and language, attention to other organizational members and conflict among hierarchically equal team members incorporate the highest learning potential for IC (Bartel-Radic & Paturel, 2006; Ely & Thomas, 2001). DLL of IC can arise when many members of a company are in contact with foreign cultures (“generalization of intercultural interaction”). As a consequence, many members of the organization develop IC within the organizational setting. Figure 1 sums up this framework that combines IC and OL literature and insights from a single-case study of a French MNC (Bartel-Radic & Paturel, 2006).

Figure 1

Theoretical framework of the study and indicators for organizational learning of intercultural

Legend :

Text in bold letters : elements of the double-loop organizational learning model (Argyris and Schön, 1978)

Text in ordinary characters: adaptation of the double loop learning model to intercultural competence

Text in balloons : indicators for the learning level or process

Method: Multiple Case study research

The aim of the empirical study was to confront this emerging framework with a larger number of cases in the context of a culture in which this phenomenon has not yet been studied, the Brazilian culture. In this section, I explain the choice and context of the case studies as well as the methods used to collect and analyze the data.

Choice and Context of the Case Studies

The Brazilian economy is not highly internationalized compared to other countries. In 2009, Brazil was the 10th economy in the world, but only the 24th exporter, the 26th importer, the 13th worldwide destination for foreign investment, and the 24th investor abroad (CIA World Factbook). The Brazilian economy really opened its borders in the mid-1990s (Abu-El-Haj, 2007). The large majority of Brazilian companies do not have long-term experience of international business and cultural differences. Therefore, until the 1990s, the Brazilian economy did not offer good conditions for the development of IC. One could thus suppose that IC is not highly developed in Brazilian companies, but as we will see in the results section, this is not necessarily the case.

Companies were chosen according to the following criteria:

substantial international experience (at least exportation and existence of foreign subsidiaries), so that conditions for SLL of IC were fulfilled (see figure 1) and that intercultural learning might have occurred in the company

Brazilian origin and management, in order to try to “capture” Brazilian characteristics, if possible

headquarters in Southern Brazil (in the States of Santa Catarina and Paraná). We intended to visit each company in order to conduct face-to-face interviews within the company context and location. The research team was based in Santa Catarina and we had no funding to travel further than 500km for each case study.

Two dozen companies corresponded to our criteria and were contacted. Gaining access to the field was very difficult, but in the end, seven companies agreed to take part in the study. In other words, we studied all the accessible cases that fit our criteria.

Of course, these cases are not representative of Brazil as a whole, which is one limitation of our study. Santa Catarina and Paraná are part of the industrialized south of Brazil with São Paulo as its center. The south is far wealthier than the north: average income in the northeast is only 40 % of that in the southeast. Culturally, Santa Catarina and Paraná are greatly influenced by the numerous immigrants from Europe; people of African origin are underrepresented compared to the rest of the Brazilian population. Santa Catarina has no major city like São Paulo or Rio, but several medium-sized industrial centers, where the selected companies are located. The case studies can be considered as representative of industrial and modern but not metropolitan Brazil. Despite these regional characteristics, the traits of Brazilian culture detailed below apply to Santa Catarina and Paraná as well as to other regions.

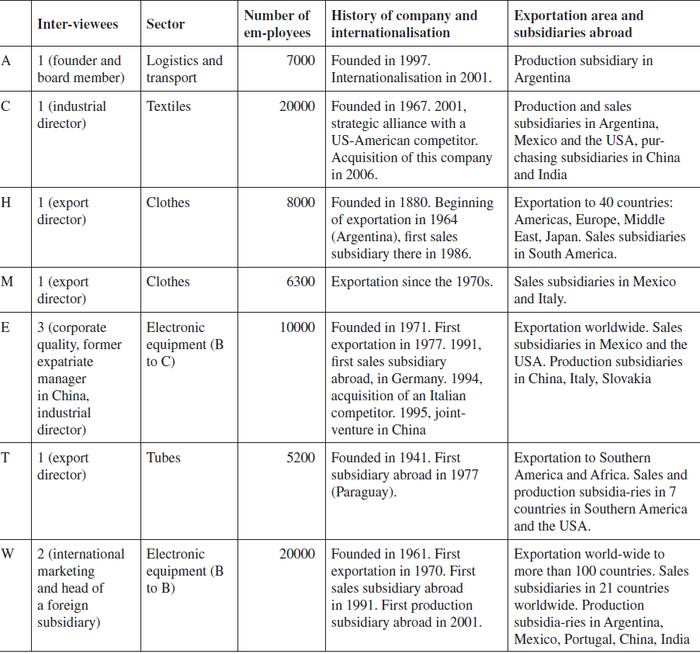

Table 1 gives an overview of the seven companies, including their history and level of internationalization. Three of the companies are exportation champions, truly international companies that went abroad many years ago and are often quoted as an example of internationalized Brazilian companies (E, T, W). Three other companies have shorter and/or less intense international experience (C, M, H). The last company (A) was founded only recently in 1997, but went international very quickly, in 2001.

The case studies are mainly based on semi-directive interviews carried out in 2008. The research team included the author and four Brazilian research assistants; the interviews were conducted in Portuguese. In each company, we aimed to interview several members who held various functions at different levels and locations, but this proved possible in only two companies as most of the companies did not grant more than one interview. All of the interviewees were highly involved in the internationalization of their company: board members, export managers, former expatriate managers of foreign subsidiaries, and marketing directors are part of the sample (see table 1).

The interview data were backed up by extensive documentary research, including internal documents. We also benefited from secondary qualitative data, case studies related to the internationalization of several of the companies studied (Forum de Lideres Empresariais and SOBEET, 2007) that we discovered after the interviews had been conducted. In the interviews with managers, themes linked to IC were mentioned spontaneously, frequently and very explicitly. These secondary data were coded like the primary data and showed the importance of these subjects for the companies. The fact that other researchers obtained results quite comparable to ours when interviewing other managers from these companies increases the validity of our study.

Table 1

Short description of the seven Brazilian MNCs studied

Data Analysis

My assistants fully transcribed all of the interviews, and I coded them within N’Vivo. Coding of the data concerned the subjects and indicators presented in figure 1. Data were analyzed following the methodology of content analysis: data were viewed as representations, read, and interpreted for their meanings. This step yielded chains of process propositions, consisting of hypothesized relations between abstracted events, which are represented in figure 2. A comparative table (table 2) and verbatim reports of interviewees was then used to present and illustrate the results. In keeping with the choice of content analysis, the quotations were chosen for what they meant for the interviewee, not only for the apparent information or text they contained.

Table 2

Indicators for organizational learning of IC in the seven cases

Results

The aim of this study was to question the process, pace and outcomes of intercultural learning in Brazilian companies. A first result concerns learning outcomes. When going international, companies are often not prepared for cultural differences and have difficulties dealing with them. In the course of other research projects, I have met people from many European and US-American companies and questioned them on these issues. I learned that it takes a long time and requires strong will for companies to acquire truly international mindsets, and many companies have not developed IC so far. As the Brazilian economy is not very international compared to other countries, and as the international experience of many Brazilians is rather limited and recent, one could suppose that Brazilian companies might not have developed high IC. This hypothesis proved to be completely wrong: organizational IC was surprisingly high in all seven companies. The studied companies had learned “faster” than we might have predicted. Table 2 shows to what extent the facilitators and indicators for OL of IC (figure 1) were present in the cases studied.

All of the companies studied have achieved SLL of IC. The following two sections detail main facilitators of intercultural learning in the cases, which are geocentric international human resource strategies and Brazilian culture. Thanks to these facilitators, four of the seven companies achieved DLL, which is reported in the last section of the results.

Single-loop Intercultural Learning

All of the companies studied are confronted with cultural differences through exportation and the establishment of subsidiaries abroad. This was one of our sampling criteria. More surprisingly, all of the interviewees very explicitly recognized that cultural differences exist and that they had to adapt to them in everyday business. This attitude is not as prevalent as one may think. Interviewees in other countries, in comparable companies and positions, sometimes deny cultural differences or minimize their impact. Here, all of the interviewees had developed individual IC. Their companies were able to draw on these individual competencies in order to adapt the organization to cultural diversity. The verbatim shows that the interviewees clearly adopt an ethnorelative attitude: “My work is to find common policies for our four production sites in Brazil, Italy, Slovakia, and China. This is not only a strategic alignment, but also a cultural one. You need to understand how these cultures ‘work’. You can not take some policies from here and take them over there… this won’t work. You need to respect local culture, and what they believe in.” (E)

The interviewees not only acknowledged the existence of cultural differences, but also demonstrated the ability to keenly analyze them. They did point to well-known stereotypes, but went beyond them in their perception of differences between people, situations, and economic sectors.

All of the companies studied have adapted their structures and routines to cultural diversity. In order to sell products and services abroad, the companies consider that simply adapting the products to foreign markets is not enough. They have realized that cultural differences have to be taken into account not only “at the surface”, but also within the organization itself: “We don’t only adapt our products to foreign markets, we also adapt the company.” (M) In all of the seven companies, work involving contact with foreign customers is systematically done by locals. Cultural differences are considered to be strong, and adapting to them is deemed so difficult that no one can perform better than locals when dealing with customers. “The commercial directors, normally, are locals, for nobody knows better the market, ways of communication and culture than somebody from the country. This strategy has helped us to overcome barriers when entering the market.” (T) The systematic delegation of customer contact to locals is an organizational structure and routine that ensures that organizational IC is displayed by the company.

The companies implement language policies that are open to cultural and language diversity. In order to better communicate with their customers, most of the companies systematically used various languages when contacting them. W’s customers are addressed in English, Spanish, German, and even Persian.

The studied companies are conscious of the image of Brazil abroad, and use or manage this image with their foreign business partners. Several interviewees mentioned that Brazil is seen by many foreigners as “the country of carnivals and beaches” but not as a country of trustworthy industrial companies producing good technical products. For the two companies in the clothing industry, this is far from a problem, as this image actually helps them sell their products abroad. But for W, a company in the B-to-B electronic industry targeting worldwide markets, this image of Brazil abroad could negatively affect the company’s ability to secure important contracts. Therefore, W established the practice of inviting foreign customers to their headquarters in Santa Catarina so as to show them the company and the industrial side of modern Brazil. “We invite our customers and potential customers over here to get them to know the country and the company, to show them that we are trustworthy. This has turned out to be one of the most effective marketing policies for the company. Every week, 34 foreign customers on average come to our headquarters. At the moment, we are expecting people from Iran and Russia. They will be looked after here by fellow natives from their respective countries, working in Brazil. This makes a big difference for the customers; their confidence in W increases immediately.” (W) The visitors stay for several days and interaction with them goes beyond convincing a customer and signing a contract. The aim of the program is to transmit tacit knowledge of the Brazilian culture and context.

Comparing these results with the theoretical framework (figure 1 and table 2), we can see that all of the companies attributed tasks to their personnel according to their cultural origins. They developed routines enabling the company to better understand cultural diversity, to behave more appropriately in foreign cultures, and to help foreign customers and partners better understand Brazilian culture. Sales methods and communication styles are largely adapted to local habits and conditions, and locally managed. Nevertheless, the seven companies are not clearly polycentric, because the independence of local subsidiaries is limited to customer relationship management and marketing; strategic decisions are centralized and a high level of integration of the subsidiaries characterizes many aspects of the companies’ policies.

Facilitators of DLL (1): Geocentric International Human Resource Strategies

Six of the seven companies encourage international cooperation and knowledge sharing between units located in different countries (table 2). In four of the companies, intercultural interaction is intensified by clearly geocentric IHR strategies. All of the companies have sent at least some of their Brazilian personnel abroad. One main reason for these foreign assignments is the transmission of corporate and organizational culture to the foreign subsidiaries. “The general and administrative directors, in all of the foreign subsidiaries except Bolivia, are Brazilians. This is important in the beginning, as they have to transmit our organizational culture.” (T)“Currently, we have ten Brazilian expatriates in China, and the main objective of this is to exchange cultures, knowledge, and customs.” (E) The younger the subsidiary, the more the presence of Brazilians with long experience at the headquarters is considered crucial. The expatriates’ mission is not to control operations from an ethnocentric viewpoint but to transmit formal and informal knowledge about the group within a geocentric mindset; as soon as local employees know the company well enough, they take over the direction of the subsidiary (M, W, T). “It’s very important for us to have Brazilians working abroad, because they already know our brands, already know their strengths (…). Over time, there will be progressive change, and some Brazilian workers will come back here, and others will stay [in Mexico]. There is a whole process of transmission of knowledge toward the Mexican employees, for them to learn to know the brand and how best to sell it.” (M)

Learning about foreign markets and cultures is another main objective of foreign assignments and travelling abroad to foreign subsidiaries. “You always have to go there and see for yourself. Only when you go to these markets, can you understand them. When you visit a shop, you can understand how things are organized. When we plan to launch an ad on a foreign market, our marketing experts travel to the country to meet the local teams, and to try to ‘feel’ the country, what will make people laugh and what will affect them” (T).

The companies studied aim to learn through intercultural interaction and transmission of tacit knowledge within the company. “The big secret lies in achieving a balance between Brazilians working abroad for M and local workers. The Brazilians represent the company better, they know M’s culture better, but on the other hand, the locals who work for M abroad are very important because they possess better knowledge of the local market and culture of the country.” (M) The IHR policies are quite informal. “We never determine the length of a foreign assignment in advance. It depends on the developments, on the process… Some expatriates will one day come back to Brazil; others will remain in the country or move on to another destination.” (T) This makes learning and adapting to changing realities possible.

IHRM policies also include impatriation of foreign employees for some of the companies (E: Italy, USA; W: several nationalities). Long-term assignments, meetings and short-term assignments also aim to have company members meet at the headquarters (all companies but H). Once again, mutual learning is the main objective of this policy: impatriated foreigners get to know both the company’s and the Brazilian culture, and Brazilian employees acquire international knowledge and IC from these encounters. “It helps a lot to have foreign people here at the headquarters. Contact with them makes it easier to adapt to our customers’ cultures. We have people from Russia, Iran, England, Spain and Japan working at our headquarters. We also have foreign employees come over here for internships, so that they will take some Brazilian culture back home to their country, afterwards. Once a year we hold the International Meeting here at the headquarters, and all the directors of foreign subsidiaries come to Brazil to exchange information and points of view. This meeting is very rich, as it reveals not only the Brazilian perspective of the company, but also that of the foreigners.” (W) “In the case of Algeria, for instance, last year, we had three employees from one of our distributors come here (…) We showed them our production sites, the marketing department and strategy, the organization of exportation, several shops… and they learned how we operate here in Brazil. They will take this knowledge back home, and try to adapt as many things as possible to their market” (T). These verbatim quotations show that managers understand the important role that tacit knowledge plays and that it is transmitted through socialization, as has been conceptualized by Nonaka (1994).

Facilitators of DDL (2): Brazilian Culture

One unexpected possibility progressively emerged from the data: Brazilian culture might enhance individual intercultural learning. When asked how their company managed to adapt to foreign markets, several interviewees spontaneously underlined the role of their home culture. “I believe that Brazilians and ‘Made in Brazil’ are welcome all over the world. Brazilians easily adapt to foreign cultures, which helps a lot. (…) I believe that the Brazilian culture, our ease to communicate, to adapt, the happiness of our people, helps more than it disrupts when negotiating.” (M) “I would say that Brazilians are highly flexible when they have to adapt to a new reality.” (T) “How I was able to adapt in China ? Well… I learned to be happy for small reasons ! But I think that we Brazilians can adapt to every country in the world.” (E)

This reaction is completely different from those I have observed in the course of other research projects in European companies. I have questioned people from several countries on how they (individually) or their companies adapted to cultural differences. Individually, people generally consider that they are able to adjust to other cultures because of their personality and attitude (openness, positive attitude towards foreignness) and thanks to former international experience. They also insist on the difficulty of learning intercultural competence, and on the fact that many people in their country are not really open to other cultures. Before studying Brazilian companies, I had never encountered people who considered that people from their country adapted to cultural diversity more easily than others.

Why does the Brazilian culture appear to be particularly beneficial to intercultural learning ? In keeping with the abductive design of this research, I referred back to the literature. Individual IC implies the absence of ethnocentrism and is enhanced by personality traits such as open-mindedness, attributional complexity or empathy (Bush et al., 2001), flexibility of behavior and tolerance for ambiguity (Kühlmann & Stahl, 1998). These traits are likely to be unequally distributed among cultures (Hatzer & Layes, 2003). Thus, traits linked to IC could also represent dimensions that distinguish national cultures. In cultures where such traits are clearly present, individuals and organizations might develop IC more easily. Several dimensions of the Brazilian national culture correspond to these “strengtheners” of IC. They basically concern flexibility and “estrangeirismo”, the Brazilian expression for ethnorelativism.

Flexibility is a typical dimension of the Brazilian culture. The interviewees point out that in Brazil, one is frequently confronted with great differences: differences in regional culture and context, color of skin, social classes, education, etc. They consider that adaptation skills are frequently necessary, without even leaving the country. Indeed, the Brazilian culture can be described best by the concept of “metissage” (Davel et al., 2008), used by Freyre (1966) as a means of sociocultural interpretation of the Brazilian specificity, or heterogeneity (Prestes Motta et al., 2001). Brazil is “a country of continental dimensions and a nation of mixed races (miscegenation), religions (syncretism), and cultures (diasporas, borderlands)” (Garibaldi de Hilal, 2006). Brazil is also a country with particularly significant regional differences, considerable disparity in income between the rich and the poor, and discrepancy between formal and informal economy (Davel et al., 2008). Da Matta (1997) showed that behaviors continually oscillate in Brazil: people can express apparently different or even contradictory opinions and behaviors depending on whether they position themselves in the ‘street’ or in the ‘home’. The space of one’s ‘home’ (including the workplace) is associated with the hierarchical and individual-related moral world in which relations among family members and servants or among superiors and subordinates involve hierarchies of race, class, age and gender. The ‘street’ space is egalitarian and individualistic and hierarchies are suspended. In certain situations the ‘home’ encompasses the ‘street’ and all matters are treated in a personal, familiar way, with the sense of loyalty and collectivism; in others the ‘street’ encompasses the ‘home’ and behavior is free of the sense of loyalty, governed by the criteria of individualism, by laws and by the rules of the market. There is, therefore, a double-edged ethic that operates simultaneously and that leads to different behaviors. Brazilians are constantly negotiating between two different codes (Garibaldi da Hilal, 2006), which requires flexibility.

The flexible nature of the Brazilian culture is also illustrated through “jeitinho”, “an informal problem-solving strategy in organizations” (Duarte, 2006) that involves bending or breaking the rules in order to deal with difficult or awkward situations. It differs from corruption in that the person who engages in a ‘jeitinho’ neither receives nor gives any financial or material benefit (Prestes Motta & Alcadipani, 1999). Jeitinho also stresses the discrepancy between rules and reality, making ambiguity a typical component of the Brazilian culture (Wood & Caldas, 1998). It is linked to ambiguity (Davel et al., 2008). In an organizational context, this culture creates dynamics based on a multitude of references that coexist in an ambivalent situation (Davel et al., 2008). Consequently, Brazilians have a high tolerance for ambiguity, one aspect of IC.

Another recurring theme in the interviews was the “inferiority complex” that many Brazilians demonstrate towards developed countries. They frequently refer to Brazil as a “3rd World Country” as opposed to “the 1st World”, like the USA or Western Europe. As a result, many Brazilians consider that they can learn a lot from foreign (“1st World”) countries, not positioning themselves in an ethnocentric perspective. “Estrangeirismo” (Prestes Motta et al., 2001) designates this attitude that overvalues what comes from abroad. As a consequence, foreign concepts and references are easily appropriated (or devoured), which has been designated by “cultural anthropophagy” (Wood & Caldas, 1998). Brazilians have “anthropophagous management practices” (Davel et al., 2008), which means that foreign management practices are easily “ingested” and adapted to local values and customs. Such management practices are somehow coherent with the main idea of the cannibalism of the first inhabitants of Brazil, the Tupi-Guarani Indians, whose aim was not to destroy that which is strange, but to ingest it (Dole, 1993). An extreme and negative expression of “estrangeirismo” is the overestimation of foreign practices and underestimation of local practices (Caldas & Wood Jr., 1997). A positive consequence of “estrangeirismo” is that it prevents an ethnocentric attitude which hinders intercultural learning. Brazilian managers consider that there are learning opportunities to be seized from other cultures and countries, especially when it comes to business or industry. When in contact with companies or customers from industrialized countries, Brazilian companies show a strong desire to learn from them. Also, unlike what people from developed countries might do, when in contact with other emergent countries or developing economies, they do not adopt a superior position. In both of these situations, this “ethnorelative” attitude, helping the organization to move towards a geocentric orientation, opens up opportunities for learning.

Indicators of DLL: Change in Organizational Culture

Most of the companies studied exported for the first time several decades ago, but the actual internationalization took place much later, progressing rapidly over the last ten or fifteen years. As a result of international experience and intercultural interaction, organizational culture clearly changed for four of the companies (C, E, T, W). One interviewee describes how he and his colleagues learned intercultural competency: “In the 1990s, when Brazil started to come out of its shell, we had no idea of what the business world abroad was like. Within the company, we had less than ten people with education in international relations, or who had lived abroad. When E set up its joint venture in China, it was a big culture shock for us. The Brazilians did not know anything about China, and the Chinese had hardly ever heard anything about foreigners, and even less about Brazilians. People were not prepared for this.What has changed most at E is that today, the world is our home. We noticed that we live in a small world. We carry cultural richness in our bags.” (E) Some interviewees even mentioned organizational culture change explicitly: “Our international dimension has increased a lot during the last two years. There has been a big cultural change within the company, which was the acceptation of the internationalization process. (…) We dedicate our efforts to the national, as well as to the international market. (…) Many people already work abroad, and others will leave soon, when new subsidiaries are established. Today, many people are now ready in their minds for an international assignment. They are ready for a new experience.” (T)

This openness to cultural diversity is reflected in organizational routines. Members of foreign subsidiaries participate in strategic decision making. “Today, when we establish a corporate policy, we never set up rules based only on Brazil. For any project, people from all of the countries participate. There is one key word: ‘respect’ for both sides. We Brazilians from the headquarters respect the local plants and personnel, but they also have to respect us.” (E)

Language issues also show that mindsets are becoming more global in some of the companies. “Brazilians working at the subsidiaries often write us [at the headquarters] e-mails in English. They forget that we are Brazilian, too !” (W) “One of the big things, at the moment, is the introduction of the Spanish language. We have employees here at headquarters who are currently studying Spanish. In the beginning, many people thought we would not need to learn Spanish because it is quite similar to Portuguese. Today, we have changed our minds.” (T)

We met managers who had a global perspective in all of the seven companies; as detailed above, the Brazilian national culture seems to have enhanced their intercultural learning. But the problem lies in the transmission of an international mindset to people and departments of the company that are less involved with intercultural contact. In the four companies having developed geocentric IHR strategies (C, E, T, W), many organizational members seem to have acquired IC. In the other three cases (A, H, M), limited intercultural interaction has restricted intercultural learning to management teams. Their difficulty lies in the generalization of learning. “Our biggest difficulty [since we started internationalization] is to transmit this ‘exportation culture’ within the company. We have a long way to go to become a company with an ‘international DNA’.” (M) Organizational learning processes of IC are far from being achieved in these three companies.

Discussion

The empirical data fit the model (figure 1) in several respects. Generally speaking, the framework which included two levels of learning, with adaptation of organizational structure at SLL and culture change at DLL, is coherent with the data. However, the case studies made it possible to obtain a finer analysis of OL of IC. Firstly, in our study, Brazilian culture not only figures as a context in which OL of IC has not yet been studied. The characteristics of Brazilian culture also emerge as facilitators for learning of IC. Secondly, some of the companies studied went further than others in DLL of IC. Our data allows us to distinguish three stages within DLL of IC and therefore to refine the model. Figure 2 adapts the framework to the new empirical findings from the Brazilian context.

In keeping with our abductive research design, the new insights from the data will now be confronted with the literature.

Figure 2

Organizational learning of intercultural competence in the seven Brazilian companies studied

National Culture as a Facilitator of OL of IC

Literature explicitly addresses organizational culture, and more implicitly national culture, as a context element for organizational learning processes. Yet, so far, national culture has not been considered as an element of the conceptual framework of organizational learning. In the data from the case studies, Brazilian culture, and especially its flexibility and plasticity, emerge as a resource for IC. As a consequence of their national culture, the Brazilian people seem to develop IC more easily, even with less international experience and intercultural interaction. Top managers who possess good IC are more likely to design strategies encouraging organizational intercultural learning by creating appropriate organizational structures and routines (SLL) or by establishing IHR policies that facilitate organizational culture change (DLL).

Literature suggests that certain aspects of national culture can hinder learning through expatriation. Wong (2005) reports the case of Japanese companies where “collective myopia” inhibits organizational learning from expatriates’ experience. In the case of Japan, a high community spirit, desire for normality and ethnocentric international strategy act as “blocking mechanisms” affecting organizational learning. This study shows that some dimensions of national culture can have a strong impact on organizational learning of aspects linked to the internationalization. Like Wong’s study, our results suggest that specific elements of organizational and national culture have a strong impact on DLL of IC.

One of the reasons why expatriation policies in the Brazilian companies appear to be successful is their geocentric orientation (Perlmutter, 1969). Their aim is neither to impose Brazilian methods with strong control (ethnocentric orientation), nor to drop potential synergies and exclusively adapt subsidies to local culture (polycentric orientation). In line with Harris et al.’s (2003) recommendations, expatriates are sent “for the right thing”. Expatriation policies aim at intercultural learning, which happens to be the main outcome of missions abroad. This is also coherent with research on diversity that shows that the organizational context (organizational culture, business strategy and human resource policies and practices) moderates the link between diversity, team processes and outcomes (Kochan et al., 2003). The IHR strategies observed within the case studies are in line with Ely and Thomas’ (2001) “integration and learning perspective” on cultural diversity. Organizations adopting this perspective meet the conditions necessary for cultural diversity to have a positive effect on performance.

Naturally, geocentric orientation and well-designed expatriation policies are not limited to Brazilian companies. However, the case studies show that the Brazilian national culture enhances individual IC, particularly among top managers. As a consequence, when defining relationships with foreign subsidiaries, for instance, they are spontaneously inclined to adopt a geocentric orientation, and create international interaction that encourages intercultural DLL.

Three Stages of Double Loop Learning of Intercultural Competence

Some of the companies studied went further than others in DLL of IC. So far, literature has analyzed DLL as “one block”. The empirical data made it distinguish three stages within organizational DLL of IC.

In the first stage, organizational mental models move increasingly towards ethnorelativism within the top management teams who adopt a global perspective and a strategic intention to promote diversity within the company. Almost all of the companies studied have reached this step, which is facilitated by the flexibility and plasticity of the Brazilian national culture.

At the second stage, the management teams design strategies for the intercultural learning of several organizational members. According to the interviewees, IC is mainly acquired through international experience. When asked how their company managed local contingencies and cultures abroad, interviewees immediately pointed to the role of contact with foreign people and contexts. Results of the case studies are particularly clear on this aspect and are completely coherent with existing literature on this point.

Some MNCs from developed countries use global teams to create international experience for organization members (Bartel-Radic & Paturel, 2006). Some of the Brazilian companies also did this, but the majority of the companies studied (4 out of 7) mainly adopted IHR policies and expatriation in order to enhance learning.

The third stage of the DLL learning of IC is a change in the organizational culture towards ethnorelativism that is obvious at many levels of the organization. Only the companies that developed considerable intercultural interaction situations for their employees, through IHR strategies, reached this third stage. As a consequence of the geocentric orientation and “integration and learning perspective” (Ely & Thomas, 2001), intercultural interaction within Brazilian MNCs is characterized by some of the conditions identified in the literature as main catalysts for intercultural learning: long-term, spontaneous interaction among ‘equal’ organization members. These catalysts of IC development on an organizational level also seem to work in the Brazilian context. Along with expatriation, inviting foreign customers and salespeople to the headquarters in Brazil also encourages intercultural interaction and learning. These policies show that the companies recognize the important role of tacit knowledge (Nonaka, 1994) and informal knowledge transfer via socialization when it comes to international business.

Our data show that Brazilian national culture helps intercultural learning, but does not replace international experience. Flexibility and ethnorelativism enhance the acquisition of IC, and Brazilian managers quite spontaneously adopt a global perspective and create learning occasions for other organization members. Yet, when this is not done, for reasons such as insufficient international activity or other priorities, DLL fails to occur at many levels of the MNC and throughout the company as a whole. Consequently, the company does not reach the third stage of OL of IC.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to examine the organizational learning of intercultural competence in Brazilian MNCs in order to contribute to the construction of a more general model for the development of IC on the organizational level. In the seven cases studied, firms had achieved a surprisingly high level of learning. The reason for this fast pace of learning seems to lie within the Brazilian culture itself. The main contribution of this study lies in the identification of national culture as an element of the organizational intercultural learning process: national culture enhances intercultural learning in the Brazilian case, while it inhibits learning in other countries. Another contribution relies in highlighting the role of geocentric international human resource strategies for the development of organizational IC. The case studies also led to a more precise analysis of the DLL of IC including three stages.

The empirical study in this research was limited to the South Brazilian context. External validity is a critical point in case study research. To what extent is the organizational learning process of IC specifically Brazilian, to what extent is it universal ? Given the lack of empirical research on this topic in other contexts, a clear answer can not be given for the moment. “Estrangeirismo” and flexibility, typical aspects of the Brazilian culture, appeared to accelerate intercultural learning in Brazil. This idea was initially self-asserted by the interviewees, but was supported by the literature on Brazilian culture. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to question foreign business partners or colleagues on the adaptation capacity and flexibility of the Brazilian people. It would also be interesting to further develop these emerging results through more country-specific and comparative studies of intercultural learning. A potential “Brazilian exception” should be considered as a proposition resulting from our study, and needs to be further tested with larger-scale research. In the meantime, this study proposes a theoretically founded and empirically supported model of organizational intercultural learning, and shows that the Brazilian culture is a fertile ground for IC.

Managers who intend to develop their company’s IC can draw several insights from this study. OL of IC requires that cultural diversity be valued within the organization, through

high decentralization of decision-making to locals, especially concerning the management of customer relationships,

development of intercultural interaction within the company, through foreign assignments, intercultural teams and international meetings.

To this effect, strategic intent is necessary. Top managers must be convinced of the importance of IC and should possess IC themselves. Some people, such as the Brazilians evidently, develop IC more easily than others. Companies seeking to develop organizational IC should endeavor to recruit people who possess high IC or good learning potential for IC when considering strategic positions or top management teams.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The author is very thankful to the Brazilian research assistants, Julia Alves Lacerda, Arthur Pires, Natacha Tcholakian and Bia Yuri Yamamoto for pleasant and effective teamwork.

Biographical note

Anne Bartel-Radic is a full professor in business administration at Institut d'Etudes Politiques of Grenoble, researcher at CERAG, Université Pierre Mendès France, Grenoble, and associate researcher at IREGE, Université de Savoie. As a German living in France, she has been interested for years in intercultural competence of people and organizations, and in intercultural teams. Her research in the field of intercultural management has been published, among others, in Management International, Management International Review and Recherches en Sciences de Gestion.

Bibliography

- Abu-El-Haj J (2007) From Interdependence to Neo-mercantilism: Brazilian Capitalism in the Age of Globalization. Latin American Perspectives 34 (5): 92-114.

- Alves Chu R and Wood Jr T (2008) Cultura organizacional brasileira pos-globalização: global ou local ? Revista de Administração Publica 42 (5): 969-991.

- Ang S and Inkpen AC (2008) Cultural Intelligence and Offshore Outsourcing Success: A Framework of Firm-Level Intercultural Capability Decision Sciences. 39 (3): 337-358.

- Argyris C and Schön DA (1978) Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Barney J (1991) Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17 (1): 99-120.

- Bartel-Radic A and Paturel R (2006) L’apprentissage organisationnel de la compétence interculturelle. Revue Sciences de Gestion 57: 55-86.

- Bartel-Radic, A (2009). La compétence interculturelle: état de l’art et perspectives. Management International 13 (4): 11-26.

- Bartlett CA and Ghoshal S (1989) Managing across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Bennett MJ (1986) Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In: Paige RM (ed), Cross-cultural orientation: New conceptualizations and applications. New York: University Press of America, 27-70.

- Black JS (1990) The Relationship of Personal Characteristics with the Adjustment of Japanese Expatriate Managers. Management International Review 30 (2): 119-134.

- Bush VD, Rose GM, Gilbert F and Ingram TN (2001) Managing Culturally Diverse Buyer-Seller Relationships: The Role of Intercultural Disposition and Adaptive Selling in Developing Intercultural Communication Competence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 29 (4): 391-404.

- Caldas MP and Wood T Jr (1997) “For the English to see”: the importation of managerial technology in late 20th-century Brazil. Organization 4 (4): 517-534.

- Carneiro R (2002) Desenvolvimento em crise: a economia brasileira no ultimo quarto do século XX. São Paolo: UNESP.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2010) Brazil. The World Factbook, Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/br.html (acc. 26 June 2010).

- Clarke C and Hammer MR (1995) Predictors of Japanese and American Managers Job Success, Personal Adjustment, and Intercultural Interaction Effectiveness. Management International Review 35 (2): 153-170.

- Cohen MD and Bacdayan P (1994) Organizational Routines Are Stored as Procedural Memory: Evidence from a Laboratory Study. Organization Science 5 (4): 554-568.

- Crossan MM, Lane HW and White RE (1999) An organizational learning framework: from intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review 24 (3): 522-537.

- Cyert R and March J (1963) A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Da Matta R (1997) A Casa e a Rua: Espaço, Cidadania, Mulher e Morte no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Guanabara.

- Davel E, Dantas M and Vergara SC (2008). Culture et gestion au Brésil. In Davel E, Dupuy JP and Chanlat JF (eds) Gestion en contexte interculturel. Québec: Presses de l’Université de Laval et Téléuniversité.

- Deitos RA (2008) Economia e estado no Brasil. Revista HISTEDBR On-line 29: 20-34.

- D’Iribarne P (1989) La logique de l’honneur. Paris: Seuil

- Dirks D (1995) The Quest for Organizational Competence: Japanese Management Abroad. Management International Review 35 (Special Issue 2): 75-90.

- Dole G (1993) From the Enemy’s Point of View: Humanity and Divinity in an Amazonian Society. Journal of Latin American Anthropology 5 (2): 82-83.

- Duarte F (2006) Exploring the Interpersonal Transaction of the Brazilian Jeitinho in Bureaucratic Contexts. Organization 13 (4): 509-527.

- Earley P and Ang S (2003) Cultural intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Ely RJ and Thomas DA (2001) Cultural Diversity at Work: The Effects of Diversity Perspectives on Work Group Processes and Outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46: 229-273.

- Fiedler M and Welpe I (2010) How do organizations remember ? The influence of organizational structure on organizational memory. Organization Studies 31 (4): 381-407.

- Fiol CM and Lyles MA (1985) Organizational Learning. Academy of Management Review. 10 (4): 803-813.

- Forum de Lideres Empresariais and SOBEET (2007) Internacionalização das empresas brasileiras. São Paulo: Clio Editora.

- Friedman VJ and Berthoin-Antal A (2005) Negotiating Reality: A Theory of Action Approach to Intercultural Competence. Management Learning 36 (1): 69-86.

- Garibaldide Hilal A (2006) Brazilian National Culture, Organization Culture and Cultural Agreement. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management 6 (2): 139-167.

- Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays, New York: Basic Books

- Harris H, Brewster C and Sparrow LM (2003) International Human Resource Management. London: CIPD Publishing.

- Hatzer B and Layes G (2003) Interkulturelle Handlungskompetenz. In: Thomas A, Kinast E, Schroll-Machl S (eds) Handbuch Interkulturelle Kommunikation und Kooperation, Vol 1. Göttingen.

- Johnson JP, Lenartowicz T and Apud S (2006) Cross-cultural competence in international busi-ness: toward a definition and a model. Journal of International Business Studies 37(4): 525-543.

- Kim DH (1993) The Link between Individual and Organizational Learning. Sloan Management Review fall: 37-50.

- Klimecki RG and Probst GJB (1993) Interkulturelles Lernen. Bern: Verlag Paul Haupt.

- Kochan T et al. (2003) The Effects of Diversity on Business Performance: Report of the Diversity Research Network. Human Resource Management 42 (1): 3-21.

- Kühlmann TM and Stahl GK (1998) Diagnose interkultureller Kompetenz: Entwicklung und Evaluierung eines Assessment Centers. In Barmeyer C and Bolten J (eds) Interkulturelle Personalorganisation. Berlin: Verlag Wissenschaft und Praxis, 213-224.

- Kusunoki K, Nonaka I and Nagata A (1998) Organizational Capabilities in Product Development of Japanese Firms: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Findings. Organization Science 9 (6): 699-718.

- Levy O, Beechler S, Taylor S and Boyacigiller NA (2007) What we talk about when we talk about ‘global mindset’: Managerial cognition in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies 38 (2): 231-258.

- Moon T (2010) Organizational Cultural Intelligence: Dynamic Capability Perspective. Group & Organization Management 35 (4): 456-493.

- Nonaka I (1994) A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organization Science 5 (1): 14-37.

- Peng, MW (2001) The resource-based view and international business. Journal of Management 27 (6) 803-829.

- Peng, MW (2004) Identifying the big question in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies 35 (2): 99-108.

- Perlmutter HV (1969) The tortuous evolution of the multinational corporation. Columbia Journal of World Business Jan-Feb: 9-18.

- Prestes Motta F, Alcadipani R, Bresler R (2001) A Valorização do Estrangeiro como Segregação nas Organizações. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 5 (Edição Especial): 59-79.

- Ralston DA, Terpstra RH, Cunniff MK and Gustafson DJ (1995) Do Expatriates Change Their Behavior to Fit a Foreign Culture ? A Study of American Expatriates’ Strategies of Upward Influence. Management International Review 35 (1): 109-122.

- Saner R, Yiu L and Sondergaard M (2000) Business diplomacy management: A core competency for global companies. The Academy of Management Executive 14 (1): 80-92.

- Schneider S and Barsoux JL (2003) Management interculturel. Paris: Pearson.

- Spitzberg BH and Changnon G (2009) Conceptualizing Intercultural Competence. In: Deardorff DK (ed) The SAGE Handbook of intercultural competence. Thousand Oaks, SAGE: 2-52.

- Taylor S and Osland JS (2003) The Impact of Intercultural Communication on Global Organizational Learning. In: Easterby-Smith M and Lyles MA (eds) The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. Oxford: Blackwell, 212-232.

- Wong MML (2005) Organizational Learning via Expatriate Managers: Collective Myopia as Blocking Mechanism. Organization Studies 26 (3): 324-350.

- Wood Jr T and Caldas, MP (1998) Antropofagia organizacional, Revista de Administração de Empresas 38 (4): 6-17.

Appendices

Note biographique

Anne Bartel-Radic est professeur des universités en Sciences de Gestion à l’Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Grenoble, chercheur au CERAG, Université Pierre Mendès France, Grenoble, et chercheur associé à l'IREGE, université de Savoie. Allemande vivant en France, elle s’intéresse depuis des années à la compétence interculturelle des personnes et des organisations, et aux équipes interculturelles. Ses recherches dans le champ du management interculturel ont été publiées, entre autres, dans Management International, Management International Review et Recherches en Sciences de Gestion.

Appendices

Nota biográfica

Anne Bartel-Radic es profesora en administración de empresas del Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Grenoble, e investigadora en el CERAG (Universidad de Grenoble). De origen alemán, actualmente radicada en Francia, sus principales centros de interés por años han sido los equipos interculturales, y la competencia intercultural de personas y organizaciones. Sus investigaciones en el campo de la gestión intercultural han sido publicadas, entre otras, en Management International, Management International Review y Recherches en Sciences de Gestion.

List of figures

Figure 1

Theoretical framework of the study and indicators for organizational learning of intercultural

Figure 2

Organizational learning of intercultural competence in the seven Brazilian companies studied

List of tables

Table 1

Short description of the seven Brazilian MNCs studied

Table 2

Indicators for organizational learning of IC in the seven cases