Abstracts

Abstract

This research note contributes to the conceptual development of neo-institutional theory by applying the work of scholars associated with the economies-of-worth research stream to enhance understanding of how objects and material devices contribute to stabilising coordination processes when multiple principles of action coexist within a single organisation. We demonstrate that, depending on the responses to different principles of action constructed by an organisation and its members, different objects and material devices are involved. Specifically, we use empirical examples to highlight three categories of objects and material devices: specific, composite and settlement objects.

Keywords:

- Neo-institutional theory,

- economies of worth,

- institutional pluralism,

- objects and material devices,

- compromise,

- local settlement

Résumé

Cette note de recherche contribue au développement analytique de la théorie néo-institutionnelle en mobilisant les économies de la grandeur pour comprendre comment les objets et dispositifs matériels participent aux processus de coordination lorsque plusieurs principes d’actions coexistent au sein d’une même organisation. Nous montrons qu’en fonction des réponses au pluralisme des principes d’actions construites par l’organisation et ses membres, différents objets et dispositifs matériels sont mobilisés. Précisément, nous mettons en valeur, au travers d’illustrations empiriques, trois catégories d’objets et dispositifs matériels : les objets spécifiques, composites et d’arrangement.

Mots-clés :

- Théorie néo-institutionnelle,

- économies de la grandeur,

- pluralisme institutionnel,

- objets et dispositifs matériels,

- compromis,

- arrangement local

Resumen

Esta nota de investigación contribuye al desarrollo analítico de la teoría neoinstitucional, movilizando las economías de la grandeza para entender cómo participan los objetos y dispositivos materiales en los procesos de coordinación cuando varios principios de acción coexisten en el seno de una misma organización. Mostramos que, en función de las respuestas al pluralismo construidas por la organización y sus miembros, distintos objetos y dispositivos materiales intervienen. En particular, ponemos de relieve, a través de ilustraciones empíricas, tres categorías de objetos y dispositivos materiales que intervienen en el tratamiento del pluralismo institucional: los objetos típicos, de compromiso y de acuerdo.

Palabras clave:

- Teoría neoinstitucional,

- economías de la grandeza,

- pluralismo institucional,

- objetos y dispositivos materiales,

- compromiso,

- acuerdo local

Article body

The way an organisation and its members successfully ensure the coexistence of heterogeneous principles of action currently lies at the heart of neo-institutional theory (NIT) (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Besharov & Smith, 2014; Lounsbury & Boxenbaum, 2013; McPherson & Sauder, 2013; Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke, & Spee, 2015). Objects and material devices[1] are regularly cited amongst the elements that play a central role in the ability of organisational members to manage this plurality of principles of action or institutional pluralism[2] (Friedland, 2012; Lanzara & Patriotta, 2007; Leca, Huault, & Boxenbaum, 2015; Tryggestad & Georg, 2011), but little work documents their roles (Blanc & Huault, 2014; Jones, Boxenbaum, & Anthony, 2013). This research note contributes to this effort by building on the conceptual developments of economies of worth (EW), which are also concerned with how organisations with heterogeneous principles of action function (Boxenbaum, 2014; Cloutier & Langley, 2013; Dansou & Langley, 2013; Leca & Naccache, 2008; Patriotta, Gond, & Schultz, 2011; Taupin, 2013). We refer to EW in order to understand how objects and material devices participate in coordination processes when multiple and heterogeneous principles of action coexist within an organisation. We show that, depending on the responses to institutional pluralism enforced by the organisation and its members, different objects and material devices are used to resist or promote change within the organisation. Specifically, we use empirical examples to highlight three categories of objects and material devices involved in the response to institutional pluralism: specific, composite and settlement objects.

This research note is divided into three main parts. First, we show that coordination issues that arise when organisations face multiple principles of action lie at the heart of both NIT and EW research streams. Second, we explain that if contributors to NIT recognise the importance of objects and material devices for solving the difficulties generated by the presence of multiple principles of action, they have to date done little to document the nature of these objects and their roles. Third, we show how EW could contribute to filling the ‘material gap’ in NIT research by focusing the analysis and developing research on three categories of objects and material devices.

Understanding collective coordination issues associated with institutional pluralism

Until recently, there was no dialogue between NIT and EW, even though NIT research focused on key and historic EW issues (Daudigeos & Valiorgue, 2010). Both theoretical frameworks study the ability of members of the same organisation to ensure that heterogeneous and potentially contradictory principles of action coexist within an organisation (Boxenbaum, 2014; Brandl, Daudigeos, Edwards, & Pernkopf-Konhäusner, 2014; Cloutier & Langley, 2013; Taupin, 2013).

For NIT, the issue of multiple principles of action crossing organisations has historically been embodied in the work of Friedland and Alford, who call on institutional theorists to ‘bring back society’ and all its diverse values in organisational theories (Friedland & Alford, 1991). In the first instance, studies of institutional pluralism focus their analyses not at the level of an organisation and its members, but at the level of the organisational fields. In particular, it is the concept of ‘institutional logic’, defined as ‘the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality’ (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008, p. 101), that opens up new research perspectives on institutional pluralism. For Friedland and Alford, Western societies and the organisations that constitute them are intersected by five major institutional logics or principles of action that support cognition and action: the bureaucratic state, Christianity, democracy, the capitalist market and families (Friedland & Alford, 1991). These ideal types of institutional logics have since been developed by Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury, who differentiate community, enterprise, the state, family, the market, the profession and religion (Thornton, 2004; Thornton et al., 2012). Following this perspective, researchers have documented how progressive change of instiutional logics within an organisational field leads to changes of cognitive frames, practices and structures at the level of organisations within the field in question (see Cloutier and Langley, 2013, for an overview). For example, Thornton and Ocasio have studied how the adoption of a market logic in the publishing sector has led to changes in terms of organisational structures and the way in which managers are succeeded (Thornton & Ocasio, 1999). Successive empirical studies have progressively demonstrated that an organisational field is not a homogeneous space but is intersected by multiple principles of action, and that the sustained supremacy of one institutional logic over others is the exception rather than the rule (Daudigeos, Boutinot & Jaumier, 2013; Goodrick & Reay, 2011; Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, 2011; Kraatz & Block, 2008).

Drawing on this, more recent works set aside references to organisational fields, instead positioning the analysis of responses to institutional pluralism at the level of organisations (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Battilana & Lee, 2014; Battilana, Sengul, Pache, & Model, 2015). Authors document how an organisation and its members successfully ensure the coexistence of heterogeneous principles of action. In the examples of a recruitment company and a microfinance organisation, Battilana and colleagues suggest that coordination rules are defined not at the level of the organisational field but within the organisation. The socialisation process of new recruits becomes a key process in assisting new members to better integrate the complexity arising from the presence of multiple principles of action (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Pache & Santos, 2010). Other studies show how heteregeneous principles of action coexist within an organisation on a discretionary basis, without organisational members seeking to establish a permanent solution (Pache & Santos, 2013). Internal negotiation spaces are thus developed so that solutions may be found and tested by organisational members (Battilana et al., 2015). Some research also examines the individual strategies and behaviour of organisational members, and studies the daily practices of these individuals for tackling the complexity generated by the presence of different principles of action (Smets & Jarzabkowski, 2013; Smets et al., 2015; Voronov, De Clercq, & Hinings, 2013).

When it comes to EW, the question of multiple principles of action crossing organisations has historically been a central issue (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999; Boltanski & Thévenot, 1989, 1991; Daudigeos & Valiorgue, 2010; Jagd, 2011; Thévenot, 2006). Within the EW conceptual framework, organisations are treated ‘not as unified entities characterised in terms of spheres of activity, systems of actors or fields, but as composite assemblages that include arrangements deriving from different worlds’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 18). These worlds that intersect organisations correspond to different principles of action. They provide organisational members with practical advice as well as with criteria and cognitive frames for assessing collective action (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006; Cloutier & Langley, 2013; Patriotta et al., 2011). According to EW scholars, organisational members have cognitive capacities that enable them to justify, assess and judge a given principle of action (Pernkopf-Konhäusner, 2014). EW distinguish eight different worlds or principles of action that act as a cognitive and assessment tool for organisational members to judge and justify collective action: civic, domestic, environmental, industrial, inspired, market, fame and project (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999; Boltanski & Thévenot, 1991; Lafaye & Thévenot, 1993) and ‘it is precisely the plurality of the mechanisms deriving from the various worlds that accounts for the tensions that pervade these organisations’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 18-19).

The EW theoretical contribution is not limited to identifying and describing the content of different worlds or principles of action, as the authors demonstrate the different processes enabling individuals to form agreements and secure compromises between different principles of action, thereby enabling collective action (Boltanski & Thévenot, 1991; Patriotta et al., 2011). EW offer a vision of collective action in which agreements and disputes between individuals arise not only from the confrontation of principles of action, but also from situated disputes and agreements that rest ‘on the involvement of human beings and objects’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 128). Thus, organisations may be analysed as composite collective action devices that incorporate ‘very diverse beings – persons, institutions, tools, machines, rule-governed arrangements, methods of payment, acronyms and names, and so forth – [that] turn out to be connected and arranged in relation to one another in groupings that are sufficiently coherent for their involvement to be judged effective, for the expected process to be carried out, and for the situations to unfold correctly’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 41).

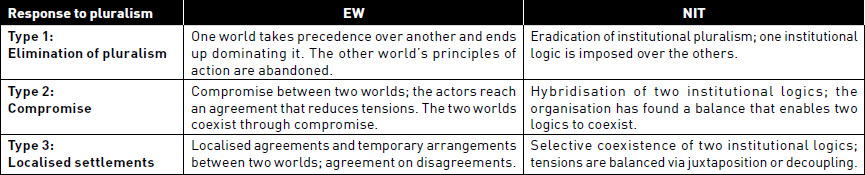

Through these developments, we see that one issue intersects both streams of research – that is, how members of one organisation can act together in the presence of multiple and heterogeneous principles of action. The table below, adapted from Cloutier and Langley, shows the responses implemented by organisations and their members to tackle the heterogeneous principles of action identified by the authors of each theoretical framework (Cloutier & Langley, 2013).

In this way, NIT and EW share the view of organisations as composite modes of collective action where the meaning and values that guide individuals are collectively constructed within a pluralist institutional context (Boxenbaum, 2014). As shown in Table 1, both theoretical frameworks offer very similar solutions for addressing issues related to the presence of multiple principles of action within one organisation: domination, compromise and localised settlements for EW; and radical change of logic, hybridity and discretionary coexistence for NIT. However, a notable difference emerges because – contrary to the situation in NIT – objects and material devices play a central role in the response to institutional pluralism in EW.

Objects and material devices as a blind spot in NIT

Recently, many studies have called on NIT authors to pay more attention to material aspects and the role of objects in their analyses of the dynamics of institutions (Cloutier & Langley, 2013; Friedland, 2012, 2013; Jones et al., 2013; Leca et al., 2015). Whereas Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury define institutional logics by their symbolic and material aspects (Thornton et al., 2012), Jones et al. (2013) stress that most theoretical and empirical studies neglect the material dimension of institutional logics (Jones et al., 2013). The review completed by the three authors demonstrates that most research on the material aspects of institutional logics centres on practices and structures, and very rarely on objects and material devices (Jones et al., 2013). In their view, this blind spot is problematic as it constitutes ‘a weakness of institutional logics research, one that may impede theory development of the multidimensionality of logics. The absence of material objects in conceptual formulations may impede empirical investigations of how practices and structures become anchored in organizations, which in turn may truncate our understanding of how logics operate across time, space, dimensions, and levels of analysis’(Jones et al., 2013, p. 69). Friedland makes the same observation when he highlights the absence of ‘institutional objects’ and notes that ‘primacy is given to practices; objects – although sometimes mentioned – are analytically inactive and invisible’ (Friedland, 2012, p. 589). According to Friedland, this omission is problematic because institutional logics are ‘constellations of practices, identities and objects’ (Friedland, 2012, p. 588) that are profoundly linked to one another and that are difficult to separate. The institutional logics that intersect an organisation are anchored in practices, and rely on objects and material devices inasmuch as they bring them into existence by conferring on them a particular meaning and function (Friedland, 2012, p. 590).

It is clear to Friedland that objects and material devices are directly connected to institutional logics and that, depending on their nature, they will play different roles. He demonstrates that certain objects – such as telephones, shoes and trombones – are not linked to specific institutional logic a priori and that they navigate without any difficulty from one institutional logic to another. They are able to adjust with a high level of flexibility to the intentions, projects and identities of the individuals who wish to follow new principles of collective action. Others, by contrast, are strongly associated with an institutional logic, and their presence indicates a frailty within, dispute with, or transformation of an agreement previously set by organisational members. For example, Friedland refers to the conflict created by the introduction of patents in university laboratories. These patents mark the university’s shift towards a market logic (Friedland, 2012, p. 591). Thus, changes of certain objects are mediums through which institutional balance is transformed. The integration of a new principle of action therefore occurs by transforming or reshaping objects and material devices. Conversely, changing objects or integrating new objects leads to a re-examination of the compromises made between institutional logics, and this development involves the task of redefining discourses, cognitive frames, values and identities of actors.

Table 1

Institutional pluralism and organisational responses, according to Cloutier and Langley (2013)

Friedland’s recent work opens the path to a broader view of objects and material devices at the heart of the NIT theoretical apparatus (Friedland, 2012, 2013). In particular, the role of objects in responding to institutional pluralism within organisations still needs to be fully clarified with regard to the nature of the different objects involved as well as to their roles within the different responses to institutional pluralism specified above (cf. Table 1). Between the objects that offer no opposition and the objects that signal a major institutional change, it would seem possible to develop a more detailed analysis of the role that objects play in the response constructed by organisational members. The contribution of EW is witnessed in this important regard, as this theoretical stream offers insights into distinguishing between different categories of objects and material devices, as well as into their roles in the construction of organisational responses to multiple principles of action.

The contribution of EW on the nature and role of objects in response to institutional pluralism

Whereas NIT primarily examines the response to institutional pluralism via cognitive changes and changes of practice (Friedland, 2012, 2013; Leca et al., 2015), the study of the role of objects and material devices in response to this very same challenge has historically been an integral part of the research programme of EW (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999; Boltanski & Thévenot, 1989, 1991; Conein, Dodier, & Thévenot, 1993; Dodier, 1993; Livet & Thévenot, 1994; Thévenot, 1990, 2006). Boltanski and Thévenot explain: ‘we seek to show how persons confront uncertainty by making use of objects to establish orders and, conversely, how they consolidate objects by attaching them to the orders constructed’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 17). In order to construct and stabilise compromises between multiple principles of action, the members of an organisation ‘rely on things, objects, and devices that are used as stable preferences for carrying out tests and trials’ (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999, p. 367). In this way, EW have progressively updated a ‘repertoire’ of objects and material devices that play differentiated roles in responding to multiple principles of action (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999; Boltanski & Thévenot, 1989, 1991). Three major categories of objects and material devices are identifiable through the specific roles they play in responding to pluralism.

Specific objects and the domination of one principle of action

One of the first categories of objects presented by EW brings together objects and material devices that are strongly associated and intertwined with a given principle of action. Authors refer to specific objects and material devices to refer to these material entities that characterise a principle of action (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 142). These objects form ‘a coherent and self-sufficient world, a nature’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 40). In Table 2 below, we present the specific objects and material devices attached to the different principles of action or worlds outlined in the work of Boltanski and Thévenot (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006).

These specific objects play an important role in helping organisational members to assess the situation in which they are immersed. Indeed, ‘when [specific] objects, or their combination in more complicated arrangements, are arrayed with subjects, in situations that hold together, they may be said to help objectify the worth of the persons involved. All objects can be treated as the trappings or mechanisms of worth, whether they are rules, diplomas, codes, tools, buildings, machines, or take some other form’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 142).

Each principle of action has a more or less developed repertoire of specific objects, which makes it easier or more difficult for individuals to assess a situation. Specific objects are particularly hostile to multiple principles of action and do not tolerate competition. The presence of other specific objects from a different principle of action creates tension because it indicates the emergence of new forms of assessing and coordinating collective action. A conflict develops between specific objects; this accompanies disputes between organisational members regarding values and perceptions. In the event that one principle of action takes precedence over another within an organisation, it is clear to EW that the specific objects associated with the mode of action in decline will be progressively criticised and devalued, to the advantage of the objects and material devices of the new principle of action. These relational disputes and the domination of specific objects by others is well demonstrated in the work of Lafaye, who studied the impact of a change of political majority on the functioning of a municipality (Lafaye, 1989).

Table 2

Specific objects and principles of action, as put forward by Boltanski and Thévenot (1991); Chiapello and Boltanski (1999); and Lafaye and Thévenot (1993)

Lafaye demonstrates how, with the arrival of a new secretary general at the head of municipal services, ‘domestic modes of action previously founded on tradition, characterised by employee seniority and the dominance of family ties, [are] dismantled in order to be replaced by industrial practices (fixed hours of work, reliance on competence criteria for recruitment, establishment of internal regulations, etc.)’ (Lafaye, 1989, p. 49). Under the thrust of the new direction, municipal employees are faced with an ‘industrial’ principle of action to develop ‘rational services management’; the process that is initiated demands ‘a purging of work situations to the sole interest of industrial efficiency’ (Lafaye, 1989, p. 49). This purging profoundly impacts the objects and material devices that are associated with a domestic principle of action; it is applied, in the first instance and symbolically, to the office of the former secretary general. The new secretary general does his utmost to eradicate his predecessor’s office, which he dismisses as being ‘very cluttered’ and as operating in a way that favours inefficiency. The tension resulting from a dispute between the domestic principle of action (deemed to be outmoded) and the industrial principle of action (deemed to be modern) leads the secretary general to ‘eradicate the items and objects belonging to the previous logic’ (Lafaye, 1989, p. 51). As Lafaye highlights, this reorganisation of municipal services ‘involves the creation and implementation of tools and instruments that are able to establish the industrial worth of the municipal services’ (Lafaye, 1989, p. 57); all the objects associated with the domestic principle of action are eliminated and rejected.

Composite objects and the construction of compromise between heterogeneous principles of action

An organisation is rarely constructed on the basis of only one principle of action; rather, it incorporates many different and potentially conflicting ones (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999; Boltanski & Thévenot, 1989, 1991). Constructing compromises is a way to ensure the sustainable coexistence of the modes of action of different principles within the organisation. According to EW, this requires ‘composite objects’ that will create and sustain a compromise over time (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 225). Thévenot highlights that ‘creating a compromise may involve an individual favouring a balance between two principles of action, but its sustained stability requires tools and devices’ (Thévenot, 1996, p. 10). These tools and devices take the form of composite objects that strengthen the compromise between heterogeneous principles of action because they are endowed ‘with their own identity in such a way that their form will no longer be recognizable if one of the disparate elements of which they are formed is removed’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 278). They make it possible ‘to suspend a clash – a dispute involving more than one world – without settling it through recourse to a test in just one of the worlds. The situation remains composite but a clash is averted. Beings that matter in different worlds are maintained in presence, but their identification does not provoke a dispute’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 277). Composite objects support a common good that goes beyond the principles of action in dispute.

These composite objects and the compromises they support are well documented by Boisard and Letablier, who studied the transformation of the modes of production of Camembert within a Normandy dairy cooperative that struck a compromise in order to produce a traditional Camembert using cutting-edge industrial tools (Boisard & Letablier, 1987, 1989). Contrary to the earlier example, the members of this organisation sought to create a compromise between ‘domestic’ and ‘industrial’ principles of action. In order to successfully strike a compromise that respected both the traditional norms recognised by the AOP (Appellation d’Origine Protégée) and standardised mass production aimed at creating a larger client base, the organisational members – after many years and much trial and error – developed a new Camembert casting machine. This respects the norms of traditional production with respect to the shape of moulds, fermentation temperature, and length of ageing, whilst simultaneously enabling mass production. The casting machine is ‘as described by its creators, a device that simultaneously meets domestic and industrial requirements’ (Boisard & Letablier, 1989, p. 214). It is ‘subject to fluctuating descriptions depending on whether focus is placed on its ability to emulate the traditional cast or on its productive capacity and industrial performance’ (Boisard & Letablier, 1989, p. 214). In the case of the dairy, ‘the striking of a compromise requires the establishment of composite material devices that borrow from both nature and activities, by people able to act in accordance with the norms of both the industrial investment formula and the domestic formula. The construction and use of the casting machine illustrates this activity’ (Boisard & Letablier, 1989, p. 214). The casting machine produces ‘compromise’ Camembert that carries a traditional certification label and has the industrial characteristics of uniformity and consistency. It allows organisational members to sustain the two heterogeneous principles of action (domestic and industrial) over time without generating conflicts within – and challenge by – either one world or the other.

Settlement objects and the construction of a localised solution

The construction of compromise via the mobilisation of composite objects that support them is the expression of organisational members’ willingness to find a common good. The organisational members deem it possible and necessary to find a harmonious compromise between multiple principles of action in the interests of all concerned. EW suggest another way of responding to the multiplicity of principles of action. It is a localised agreement between organisational members who share a temporary understanding based on their interests. This time, it is not the common good that is sought, but situational agreement ‘between two parties that refers to their mutual satisfaction rather than a general good (“you do this, which is good for me; I do that, which is good for you”)’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 336). Organisational members ‘reach an understanding – a momentary, local understanding – in such a way that the disagreement is smoothed over even though it is not resolved by reference to a common association’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 33).

The agreement is valid for a period of time and depends on given actors, without any pretence to being extended and publicly defended. Organisational members agree amongst themselves ‘to bring a disagreement over worth to an end without exhausting the issue, without really resolving the quarrel’ (Boltanski & Thévenot, 2006, p. 128). As with compromise, the construction of a localised solution requires tools and the use of specific objects. Here, we use the term ‘settlement objects’ to designate the category of objects that permit organisational members to find localised and temporary solutions to integrating multiple principles of action in line with their interests and particular projects (Boltanski & Thévenot, 1991, pp. 336-338).

These settlement objects can be seen in the work of Girard and Stark (Girard & Stark, 2003), who – using analytical developments within the EW theoretical framework – examine the sources of innovation through ethnographic research carried out within a web agency. For Girard and Stark (2003, p. 80), an organisation’s innovative potential ‘may be most fully realized when different organizational principles coexist in an active rivalry within the firm[3]. By rivalry, we do not refer to competing camps and factions, but to coexisting logics and frames of action. The organization of diversity is an active and sustained engagement in which there is more than one way to organize, label, interpret and evaluate the same or similar activity.’ In the absence of a centralised agreement, this sustainable coexistence of different, heterogeneous principles of action requires a by-project management method, based on very specific objects and material devices. In fact, each project unites a certain number of actors from different departments who use different principles of action: business managers linked to the market principle of action, designers linked to the inspirational principle of action, and programmers and data processors linked to the industrial principle of action. No compromise is agreed at the organisational scale between different organisational members. It is the project management guide and the planning time schedule that prove to be the key material devices for uniting the various members involved in harmonising and reaching localised agreements that apply only for a limited time and to a specific project. This project management guide invites the various project members to work independently in order to be as creative as possible within their respective fields, whilst also insisting on the need to meet deadlines and set aside time for meetings and consultation, so that each actor liaises with the other parties participating in the project: ‘I present to you accounts of my work so that you can take my problems and goals into account in yours. We do what works to make it work. We need to talk to get the job done, but to get the job done we need to stop talking and get to work. We give reasons and explain the rationale but always use multiple rationalities. We do not end disputation so much as suspend it. To build web sites, we make settlement’ (Girard & Stark, 2003, pp. 99-100). In the absence of compromise, settlement objects are indispensable to the coexistence of different principles of action. Without their existence, collective action is difficult as actors are unable to agree and cooperate with one another.

Conclusion

A growing number of scholars highlight the paradoxical and problematic relationship of the NIT research stream with objects and material devices. Whereas the role of this research stream in response to institutional pluralism is continually raised, little work has theoretically addressed or empirically described the role of objects and material devices. The purpose of this research note is to bridge this gap by engaging the theoretical framework of EW. Researchers associated with the EW research stream have demonstrated that – depending on the responses constructed by an organisation and its members (the elimination of opposing logics, compromise between logics, or localised agreements) – different objects and material devices intervene to resist or support internal change within the organisation. Specifically, we highlight in this paper three categories of objects and material devices that play a role in responding to institutional pluralism within organisations. Specific objects are associated with a given principle of action, and the introduction of a new principle of action is accompanied by the introduction of associated specific objects and competition with pre-existing specific objects. Composite objects embody and sustain organisational compromise over time. They support a common good that transcends rival principles of action. Finally, settlement objects sustain localised agreements between organisational members that are temporary and founded on specific interests. These results suggest that EW can, in many ways, contribute to NIT research on how institutional pluralism is managed within organisations. First of all, EW offer a typology of objects and material devices that reflect their varied natures. Then, they allow for an examination of the role of these different objects in how the various types of organisational response to institutional pluralism are formed. Finally, they open the door to understanding objects not simply as indicators that make it possible to grasp the institutional logics in play, but also as elements directly involved in the response to institutional pluralism alongside organisational members (Chiapello & Gilbert, 2013; Livet & Thévenot, 1994; de Vaujany, Mitev, Lanzara & Mukherjee, 2015).

Appendices

Biographical notes

Thibault Daudigeos is Associate Professor at Grenoble Ecole de Management and the head of the Alternative forms of Organizations and Markets (AFMO) research team. His research focuses on the role of business in society and on the related institutional dynamics in and around organizations. He has recently launched a new research program on the sharing economy. His works have been published in Business & Society, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Management Studies or Organization.

Bertrand Valiorgue is professor of strategy and corporate governance at the Ecole Universtaire de Management of Clermont-Ferrand (France). His research activities are linked to corporate social responsibility issues and the collective management of negative externalities. He is also a specialist of corporate governance issues in cooperatives. From 2010 to 2011, he has been a research fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He holds with Xavier Hollands the Chair Alter-Gouvernance (www.alter-gouvernance.org) and has recently released the first governance code dedicated to agricultural cooperatives (www.refcoopagri.org).

Notes

-

[1]

Boltanski and Thévenot (1991, p. 179) define material devices as combinations of complex objects.

-

[2]

Institutional pluralism refers to the fact that multiple principles of action or institutional logics provide organisational members with different cognitive systems and practical patterns of collective action (Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, 2012).

-

[3]

Stark refers to ‘heterarchies’ to define complex organisational systems intersected by multiple principles of action or institutional logics (Stark, 2011).

Bibliography

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), p. 1419-1440.

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing–Insights from the study of social enterprises. The Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), p. 397-441.

- Battilana, J.; Sengul, M.; Pache, A.-C.; Model, J. (2015). Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: The case of work integration social enterprises. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), p. 1658-1685.

- Besharov, M. L.; Smith, W. K. (2014). Multiple institutional logics in organizations: Explaining their varied nature and implications. Academy of management reviow, 39(3), p. 364-381.

- Blanc, A.; Huault, I. (2014). Against the digital revolution? Institutional maintenance and artefacts within the French recorded music industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 83(1), p. 10-23.

- Boisard, P.; Letablier, M.-T. (1987). Le camembert: normand ou normé. Deux modèles de production dans l’industrie fromagère Entreprise et produits. Paris: Cahiers du Centre d’études de l’emploi, Presse Universitaire de France.

- Boisard, P.; Letablier, M.-T. (1989). Un compromis d’innovation entre tradition et standardisation dans l’industrie laitière. In L. Boltanski et L. Thevenot (Eds.), Justesse et justice dans le travail (pp. 210-218). Paris: Presse Universitaire de France.

- Boltanski, L.; Chiapello, E. (1999). Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme: Gallimard Paris.

- Boltanski, L.; Thévenot, L. (1989). Justesse et justice dans le travail. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

- Boltanski, L.; Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification.Economies of worth. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Boxenbaum, E. (2014). Toward a Situated Stance in Organizational Institutionalism Contributions From French Pragmatist Sociology Theory. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(3), p. 319-323.

- Brandl, J.; Daudigeos, T.; Edwards, T.; Pernkopf-Konhäusner, K. (2014). Why French pragmatism matters to organizational institutionalism. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(3), p. 314-318.

- Chiapello, E.; Gilbert, P. (2013). Sociologie des outils de gestion. Paris: La Découverte.

- Cloutier, C.; Langley, A. (2013). The Logic of Institutional Logics Insights From French Pragmatist Sociology. Journal of Management Inquiry, 22(4), p. 360-380.

- Conein, B.; Dodier, N.; Thévenot, L. (1993). Les objets dans l’action - de la maison au laboratoire. Paris: Raisons pratiques.

- Dansou, K.; Langley, A. (2013). Institutional work and the notion of test. M@n@gement, 15(5), p. 503-527.

- Daudigeos, T., Boutinot, A., & Jaumier, S. (2013). Taking stock of institutional complexity: Anchoring a pool of institutional logics into the interinstitutional system with a descendent hierarchical analysis. In M. Lounsbury et E. Boxenbaum (Eds.), Institutional Logics in Action, Part A., Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, p. 319-350.

- Daudigeos, T., & Valiorgue, B. (2010). Convention theory: Is there a French school of organizational institutionalism? Academy of Management Proceedings, Retrieved from http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/51/23/74/PDF/WP_10-04.pdf

- DeVaujany, F.-X., Mitev N., Lanzara F., and Mukherjee A., (2015). Materiality, Rules and Regulation: New Trends in Management and Organization Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dodier, N. (1993). Les appuis conventionnels de l’action. Eléments de pragmatique sociologique. Réseaux, 11(62), p. 63-85.

- Friedland, R. (2012). The Institutional logics Perspective: A now approach to culture, Structure, and Process. M@n@gement, 15(5), p. 583-595.

- Friedland, R. (2013). God, love and other good reasons for practice: Thinking through institutional logics. Institutional Logics in Action: Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 39, p. 25-50.

- Friedland, R.; Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In W. Powell et P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 232-263.

- Girard, M.; Stark, D. (2003). Heterarchies of value in Manhattan-based new media firms. Theory, culture & society, 20(3), p. 77-105.

- Goodrick, E.; Reay, T. (2011). Constellations of institutional logics changes in the professional work of pharmacists. Work and Occupations, 38(3), p. 372-416.

- Greenwood, R.; Raynard, M.; Kodeih, F.; Micelotta, E. R.; Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), p. 317-371.

- Jagd, S. (2011). Pragmatic sociology and competing orders of worth in organizations. European Journal of Social Theory, 14(3), p. 343-359.

- Jones, C.; Boxenbaum, E.; Anthony, C. (2013). The immateriality of material practices in institutional logics. In M. Lounsbury et E. Boxenbaum (Eds.), Institutional Logics in Action, Part A. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, p. 51-75.

- Kraatz, M. S.; Block, E. S. (2008). Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In K. Sahlin-Andersson, R. Greenwood, C. Oliver et R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism, London, Sage, p. 243-275.

- Lafaye, C. (1989). Réorganisation industrielle d’une municipalité de gauche. In L. Boltanski et L. Thévenot (Eds.), Justice et justesse dans le travail. Paris: Presse Universitaire de France, p. 43-66.

- Lafaye, C.; Thévenot, L. (1993). Une justification écologique?: Conflits dans l’aménagement de la nature. Revue française de sociologie, 34(4), p. 495-524.

- Lanzara, G. F.; Patriotta, G. (2007). The institutionalization of knowledge in an automotive factory: templates, inscriptions, and the problem of durability. Organization studies, 28(5), p. 635-660.

- Leca, B.; Huault, I.; Boxenbaum, E. (2015). Le tournant “materiel” dans la théorie néoinstitutionnaliste. In F. De Vaujany, A. Hussenot et J. Chanlat (Eds.), Théorie des organisations, Quatre tournants pour penser les évolutions organisationnelles et managériales. Paris: Economica.

- Leca, B.; Naccache, P. (2008). Book review: “Le Nouvel Esprit du Capitalisme” : Some reflections from France. Organization, 15(4), p. 614-620.

- Livet, P.; Thévenot, L. (1994). Les catégories de l’action collective. Analyse économique des conventions, p. 139-167.

- Lounsbury, M.; Boxenbaum, E. (2013). Institutional logics in action. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 39, p. 3-22, Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- McPherson, C. M.; Sauder, M. (2013). Logics in action managing institutional complexity in a drug court. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(2), p. 165-196.

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. (2010). When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of management review, 35(3), p. 455-476.

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F. (2013). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), p. 972-1001.

- Patriotta, G.; Gond, J. P.; Schultz, F. (2011). Maintaining legitimacy: Controversies, orders of worth, and public justifications. Journal of Management Studies, 48(8), p. 1804-1836.

- Pernkopf-Konhäusner, K. (2014). The Competent Actor Bridging Institutional Logics and French Pragmatist Sociology. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(3), p. 333-337.

- Smets, M.; Jarzabkowski, P. (2013). Reconstructing institutional complexity in practice: A relational model of institutional work and complexity. Human relations, 66(10), p. 1279-1309.

- Smets, M.; Jarzabkowski, P.; Burke, G.; Spee, P. (2015). Reinsurance Trading in Lloyd’s of London: Balancing conflicting-yet-complementary logics in practice. Academy of Management Journal, 58(3), p. 932-970.

- Stark, D. (2011). The sense of dissonance: Accounts of worth in economic life: Princeton, Princeton University Press.

- Taupin, B. (2013). The more things change... Institutional maintenance as justification work in the credit rating industry. M@n@gement, 15(5), 529-562.

- Thévenot, L. (1990). Les entreprises entre plusieurs formes de coordination. In J. D. Reynaud, F. Eyraud, C. Paradeise et J. Saglio (Eds.), Les systèmes de relations professionnelles. Lyon/Paris: CNRS.

- Thévenot, L. (1996). Justification et compromis. In M. Canto-Sperber (Ed.), Dictionnaire d’éthique et de philosophie morale (pp. 789-794). Paris: PUF.

- Thévenot, L. (2006). L’action au pluriel : sociologie des régimes d’engagement. Paris: La Découverte.

- Thornton, P. H. (2004). Markets from culture: Institutional logics and organizational decisions in higher education publishing: Stanford, Stanford University Press.

- Thornton, P. H.; Ocasio, W. (1999). Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958-1990 1. American journal of sociology, 105(3), p. 801-843.

- Thornton, P. H.; Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In K. Sahlin-Andersson, R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism, London, Sage, p. 99-128.

- Thornton, P. H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tryggestad, K.; Georg, S. (2011). How objects shape logics in construction. Culture & Organization, 17(3), p. 181-197.

- Voronov, M.; De Clercq, D.; Hinings, C. B. (2013). Institutional complexity and logic engagement: An investigation of Ontario fine wine. Human relations, 66(12), p. 1563-1596.

Appendices

Remerciements

Nous tenons à remercier les trois relecteurs anonymes pour leurs précieux conseils qui ont permis de préciser les enjeux et résultats de cette recherche. Les aides et encouragements de Christian Bessy se sont également avérés déterminants dans la réalisation ce travail.

Notes biographiques

Thibault Daudigeos est Professeur Associé à Grenoble Ecole de Management. Il anime une équipe de recherche dédiée aux formes alternatives de marchés et d’organisations (AFMO). Ses recherches portent sur l’évolution du rôle des entreprises dans la société et sur les institutions qui sous-tendent cette évolution. Il a récemment lancé un programme de recherche sur l’économie collaborative. Ses travaux ont été publiés entre autres dans Business & Society, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Management Studies ou Organization.

Bertrand Valiorgue Docteur en sciences de gestion et HDR, il enseigne la stratégie et le gouvernement des entreprises au sein de l’Ecole Universitaire de Management de l’Université Clermont Auvergne. Ses recherches portent sur la gouvernance des entreprises, la responsabilité sociale et le management stratégique des externalités négatives. Il a été visiting scholar en 2010-2011 à la London School of Economics and Political Science. Ses travaux sont publiés dans les meilleures revues françaises (revue française de gestion, M@n@gement, RFSE) mais également anglo-saxones (Business and Society, Journal of Business Ethics). Il est co-titulaire avec Xavier Hollandts de la Chaire Alter-Gouvernance et auteur avec ce dernier du premier référentiel de gouvernance des coopératives agricoles (www.refcoopagri.org).

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Thibault Daudigeos es Associate Professor en Grenoble Ecole de Management. Dirige un equipo de investigación dedicado a las formas alternativas de mercados y organizaciones (AFMO). Su investigación se centra en el papel cambiante de los negocios en la sociedad y las instituciones que sustentan esta evolución. Recientemente se puso en marcha un programa de investigación sobre la economía colaborativa. Su trabajo ha aparecido entre otros en Business & Society, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Management Studies o Organization.

Bertrand Valiorgue Doctor en Administración y HDR, enseña la estrategia y la gestión empresarial dentro de la Escuela de Gestión de Université Clermont Auvergne. Su investigación se centra en la gestión empresarial, la responsabilidad social y la gestión estratégica de las externalidades negativas. Era un visiting scholar en 2010-2011 en London School of Economics (LSE). Su trabajo ha sido publicado en las mejores revistas Francés (Revue Française de Gestion, M@n@gement, Revue Française de Socio-Economie), sino también anglosajona (Business & Society, Journal of Business Ethics). Tiene, junto con Xavier Hollands, la chaire Alter-Gouvernance (www.alter-gouvernance.org) y ha publicado recientemente el primer código de gobernanza dedicado a las cooperativas agrícolas (www.refcoopagri.org).

List of tables

Table 1

Institutional pluralism and organisational responses, according to Cloutier and Langley (2013)

Table 2

Specific objects and principles of action, as put forward by Boltanski and Thévenot (1991); Chiapello and Boltanski (1999); and Lafaye and Thévenot (1993)