Abstracts

Abstract

We explore the emergence of an entrepreneurial team strategic orientation, or team regulatory focus, and highlight factors that contribute to its dynamism throughout a sustainable venture’s early growth. By considering the hierarchical model of regulation that distinguishes between the system (ideal vs. ought goals), strategic (eager vs. vigilant), and tactical (risky vs. conservative) levels, we show that the combination of foci is achieved at the tactical level, when team members have reached a shared understanding at the strategic level. Moreover, changes at the strategic level can accompany changes at the goal level, pressuring ideal goals that were previously shared.

Keywords:

- Regulatory focus,

- entrepreneurial team,

- growth,

- sustainable venture

Résumé

Nous explorons l’émergence d’une orientation stratégique dans une équipe entrepreneuriale, ou focus régulateur d’équipe, et mettons en évidence des facteurs qui contribuent à son dynamisme pendant la phase de croissance initiale d’une entreprise durable. En considérant le modèle de régulation hiérarchique qui distingue les niveaux système, stratégique et tactique, nous montrons que la combinaison des focus est réalisée au niveau tactique, lorsque les membres de l’équipe ont atteint une compréhension partagée au niveau stratégique. De plus, des changements au niveau stratégique peuvent accompagner des changements au niveau des objectifs (niveau système), en faisant pression sur des objectifs idéaux précédemment partagés.

Mots-clés :

- Focus régulateur,

- équipe entrepreneuriale,

- croissance,

- entreprise durable

Resumen

Exploramos el surgimiento de una orientación estratégica en un equipo empresarial, o un enfoque regulatorio de equipo, y destacamos los factores que contribuyen a su dinamismo durante la fase de crecimiento inicial de una empresa sostenible. Al considerar el modelo jerárquico de regulación que distingue los niveles de sistema, estratégico y táctico, demostramos que la combinación de enfoque se logra en el nivel táctico, cuando los miembros del equipo han alcanzado un entendimiento compartido en el nivel estratégico. Además, los cambios en el nivel estratégico pueden acompañar a los cambios en los objetivos, al presionar los ideales previamente compartidos.

Palabras clave:

- Enfoque regulatorio,

- equipo empresarial,

- crecimiento,

- empresa sostenible

Article body

Diversity opens the possibilities of action for entrepreneurial teams (Brockner et al, 2004). This is important during venture creation (Schjoedt & Kraus, 2009) and early growth (Hite & Hesterly, 2001), which involve rapidly changing tasks and resource needs. In particular, Schjoedt and Kraus (2009) call for the consideration of deep-level factors such as diversity in terms of values, attitudes and personality (Ben-Hafaïedh, 2017; Klotz et al, 2014). Along the same line, Brockner et al (2004) suggest that diversity in terms of self-regulation is key for entrepreneurial teams. Building on Regulatory Focus Theory (RFT, Higgins, 1997; Higgins, 1998), they distinguish between two main strategic orientations: an idealistic and eager approach of entrepreneurial action, that is a promotion focus, or a responsibility-driven, vigilant approach, that is a prevention focus. Promotion is usually associated with ideal goals, the eager approach of desired end-states and the avoidance of status quo. A promotion focus has been linked to entrepreneurial actions such as the identification of more business opportunities (Tumasjan & Braun, 2012) and the development of new products that are more original (Spanjol et al, 2011). By contrast, prevention is mainly concerned with duties and obligations, the approach of safety as well as the avoidance of status quo deterioration (Baas et al, 2011), which tend to be associated with entrepreneurial actions such as due diligence when screening ideas (Brockner et al, 2004), and the cautious execution of a business plan (Pollack et al, 2015).

A promotion-focused team would benefit from more flexibility and creativity while exploring business opportunities (Brockner et al, 2004; Hmieleski & Baron, 2008), yet it is associated with a lack of commitment to extant plan (Scholer et al, in press). A prevention-focused team would diligently manage the venture (Brockner et al, 2004; Wallace et al, 2010) but it can lead to rigidity and obsolescence (Hmieleski & Baron, 2008). Heterogeneous teams, on the other hand, would have the capability to commit to extant business opportunities as well as the willingness and capacity to change direction when necessary (Scholer et al, in press). Hence, building on RFT, we can deepen our understanding of entrepreneurial actions, in particular how teams cope with challenges that require both foci (Brockner et al, 2004), such as when balancing the exploration of business opportunities with their exploitation (Choi et al, 2008), idealistic aspirations with business discipline (Dees, 1998) or a sense of environmental responsibility with opportunities of gains and growth (Fischer et al, 2018).

However, entrepreneurship research, so far, has come short of investigating the combination of foci in teams. Most publications look at the RF of solo entrepreneurs (Angel & Hermans, 2019) and do not inform about the way they could be (fruitfully) combined inside teams (Fischer et al, 2018). But research from social psychology and organization studies provides some preliminary conceptual pieces. It suggests that teams might experience a convergence of focus rather than a combination. Because of team interactions (Beersma et al, 2013; Florack & Hartmann, 2007; Levine et al, 2000) and elements of organizational culture (Faddegon et al, 2008; Roczniewska et al, 2018), team members would tend to regulate their group-related activities with the same focus, labelled Collective Regulatory Focus (CRF) (Rietzschel, 2011). More recent work even construes CRF as an emergent state (Johnson et al, 2015; Owens & Hekman, 2016; Sacramento et al, 2013), i.e. a property of teams which is dynamic in nature and varies as a function of team context, inputs, processes, and outcomes (Marks et al, 2001, p. 357). While existing research contributes to understand the regulation of teams, there are two notable shortcomings. First, the construct of CRF as currently mobilized (Owens & Hekman, 2016; Rietzschel, 2011; Sacramento et al, 2013) reflects sharedness (van Knippenberg & Mell, 2016) amongst team members rather than diversity. Second, the focus is on the impact of CRF rather than on its emergence. The dynamic processes by which a CRF might develop and be maintained are still largely unknown (Johnson et al, 2015). Especially, the role of conflicts needs further attention (Johnson et al, 2015) as the tentative combination of prevention and promotion would most likely come along with frictions (Bohns & Higgins, 2011; Bohns et al, 2013; Scholer et al, in press). The same event – a new collaboration prospect, for instance – could be a competitive threat to be avoided with a prevention focus, or a new opportunity to be explored with a promotion focus (McMullen et al, 2009).

In this article, we tackle those two shortcomings. First, we draw on the hierarchical model of self-regulation (Scholer & Higgins, 2008, 2010), which distinguishes between the system (ideal vs. ought goals), strategic (eager vs. vigilant), and tactical (risky vs. conservative) levels. Such a complexity allows to refine our understanding of team regulation beyond the mere emergence of a consensual strategic orientation. We find that the articulation of different RF in the entrepreneurial team is achieved at the tactical level, when team members have reached a shared understanding at both the goal and strategic levels. Second, we apply an in-situ, qualitative approach to investigate RF as it unfolds inside an entrepreneurial team. We contribute to the study of CRF as an emergent state by identifying factors that interrelate with it, including the team processes of voice (Liang et al, 2012; Lin & Johnson, 2015), affective commitment between team members (Johnson & Yang, 2010) and growing pains from scaling the venture (Flamholtz & Randle, 2000). We distinguish between two types of voices (Liang et al, 2012; Lin & Johnson, 2015) that contribute, respectively, to the convergence at the strategic level and diversity at the tactical level. We argue that both are needed to reap the benefits of diversity. We also suggest that the articulation at the tactical level might weaken over time, as imperatives at the strategic level – “how” team members organize growth – pressure shared goals – “what” team members consider as a legitimate finality. Through such dynamics, the convergence at the strategic level pressures diversity at the system and tactic levels.

The paper unfolds as follows. In the next section, we present the theoretical framework. We then turn to the methodology used to explore RF during early growth in a sustainable venture. Our findings constitute the following section. The last section discusses this research’s results and their implications as well as some limitations, and concludes with future research directions.

Theoretical Framework

Prevention and Promotion Foci

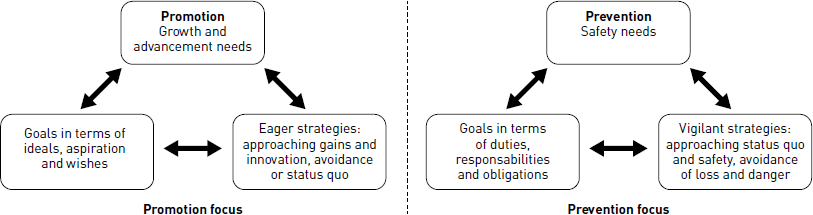

RFT looks at the way individuals translate their needs into congruent goals, strategies and tactics for goal pursuit (Higgins & Molden, 2003). Individuals who are motivated by growth and advancement needs might define their goals in terms of their own aspirations and ideals (Cornwell & Higgins, 2015; Higgins, 1997, 1998), their “unreachable star” (see Figure 1). At the same time, they will tend to select projects that are risky but have the potential to advance their dream. It is about thriving and maximizing positive outcomes (Higgins & Spiegel, 2004). Higgins (1997, 1998) calls this regulation principle a promotion focus, where individuals give more attention to potential gains rather than loss: status quo is already a failure and tends to be avoided (Cornwell & Higgins, 2015; Molden et al, 2008).

By contrast, a prevention focus is associated with safety needs. Goals are expressed in conservative terms, like duties, responsibilities and obligations, and are minimal goals, or ought goals, rather than ideals and aspirations (Cornwell & Higgins, 2015). It is about surviving and minimizing negative outcomes (Scholer et al, 2010), which means that the status quo – the survival of an activity for instance – is already a success. As such, more conservative strategies might be preferred (Higgins & Molden, 2003). There is an interesting exception though: when already in state of failure, a prevention focus might trigger a risky behavior to get back to safety (Scholer et al, 2010). Risk preferences are thus not stable but change according to the situation and the imperatives of goal pursuit. According to Scholer and Higgins (2008, 2010), the reason is that self-regulation unfolds at different levels (system, strategic, tactic), which are defined by different concerns (e.g., goals, strategies, behaviors) and together form a hierarchical model of self-regulation (see Table 1).

The system level is about “what” individuals typically consider as a desired end-state to be approached, or an undesired end-state to be avoided (Cornwell & Higgins, 2015), such as ideals and growth (promotion), or duties and security (prevention). The strategic level of motivation is about “how” people engage in goal pursuit, which is with either eagerness, or vigilance (e.g., Spiegel et al, 2004; Wallace et al, 2009). Finally, the tactical level refers to the instantiation of a strategy at a given time and place (Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987; Higgins, 1997) such as risky versus conservative thresholds for project approval (Johnson et al, 2015), or speed versus accuracy when performing a task (Förster et al, 2003). In an entrepreneurial setting, Kanze et al (2018) argue that discussions about roll-out, speed to market, network effects, milestone projection and business development are cues for a promotion focus, while discussions about quality assurance, due diligence, logistics, competitive defensibility, cost effectiveness, policies and procedures are cues for a prevention focus.

FIGURE 1

Regulatory focus: articulating congruent needs, goals and strategies

Table 1

A hierarchical model of regulatory focus

According to Scholer and Higgins (2011), each level is independent, meaning that there is more than one behavior that can serve a given goal at the upper level. Without this distinction, it would not be possible to consider the risky behavior of preventive-focused individuals, or the risk aversive behavior of promotion-focused individuals. Furthermore, it allows for a sharper understanding of entrepreneurial behavior in context, when external instructions have proper self-regulation effects (Spiegel et al, 2004).

Combining Prevention and Promotion

The Benefits of Diversity

Higgins argues that a promotion focus is central for entrepreneurial tasks such as the generation of new ideas for solving problems or developing new business models (Baas et al, 2011; Brockner et al, 2004). Its positive influence on entrepreneurial outcomes (e.g., creativity, opportunity recognition, innovation) has been largely confirmed (Hmieleski & Baron, 2008; Johnson et al, 2015; Simmons et al, 2016; Spanjol et al, 2011; Wallace et al, 2010). For other tasks, such as idea screening with due diligence (Brockner et al, 2004), a prevention focus might be more adequate but entrepreneurship research exhibits a negative bias towards prevention and its impact on entrepreneurial outcomes. Some rare exceptions are Wallace et al (2010) who show the positive effect of the CEO’s prevention focus on performance in stable environments, as well as Burmeister-Lamp et al (2012) who show that a prevention focus leads to more time allocation in the project under the right circumstances. Moreover, we find even fewer studies examining the complementarity of promotion and prevention focus. This is surprising, since Brockner et al (2004) explicitly develop the idea that combining promotion and prevention is a key success factor for entrepreneurs. Self-regulation diversity opens up the possibility of action, since team members are confronted with new representations, heuristics and mental schemes, which provide new view points and actions (Fridman et al, 2016).

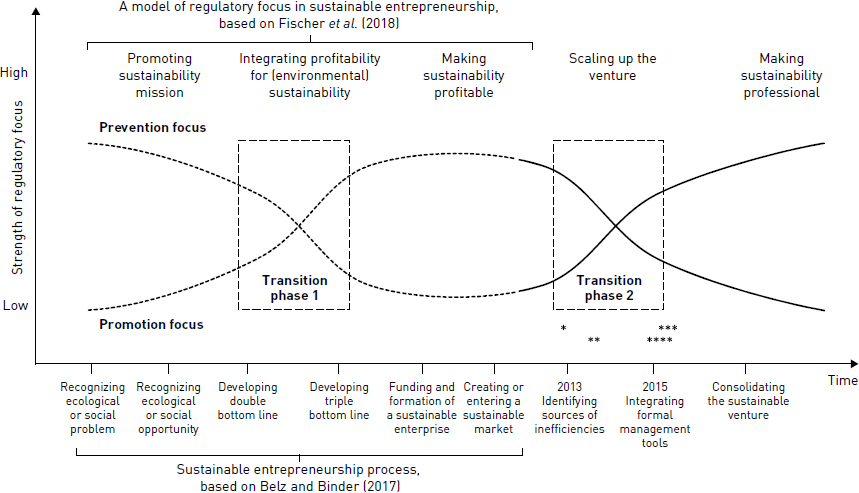

A notable exception is Fischer et al (2018) who study whether the initial motives of the founder of a sustainable venture persist or change during the venture creation process. They suggest that (solo) sustainable entrepreneurs are more prevention-focused during the opportunity identification phase, when they realize the planet must be protected, and then switch to promotion when creating the venture and planning for growth. However, their study does not examine what happens afterwards (see Figure 2). What needs does scaling trigger? And how would this unfold at the various levels of the hierarchical model (Table 1 above)? These questions constitute our first research concern in this article. Moreover, while Fischer et al (2018) state the importance of entrepreneurial teams, their research does not examine this issue specifically.

FIGURE 2

A model of regulatory focus in sustainable ventures

Combining Foci in Teams: Insights from Entrepreneurship Research

The few relevant studies provide conflicting results. Johnson et al (2017) show that a leader’s prevention can moderate the positive effect of a follower’s promotion on entrepreneurial intention. By contrast, Wu et al (2008) suggest that a leader’s injunction simply supplants follower’s regulation foci. Similarly, Spanjol et al (2011) suggest that instructions can induce a dominant focus in heterogeneous teams, in which case the chronic RF of partners have no direct or indirect effect on team performance. Yet, Spanjol et al (2011) also find that chronic RF have a direct effect on performance for homogenous teams, with a twist. In preventive teams, eager instructions positively moderate the effect on team’s outcomes. In promotional teams, vigilant instructions positively moderate the effect of their promotion focus on outcomes. In other words, homogenous teams are able to reap the benefice of complementarity when provided with instructions reflecting the other focus. Heterogeneous teams fail to do so and converge towards the instructed focus.

The hierarchical model of self-regulation might shed some light on these strange results and help to understand the combination of foci. In heterogeneous teams, without shared goals (system level), the leader’s instructions are the only adequate imperatives (strategic level). A convergence towards this strategic orientation occurs. In homogeneous teams, partners have congruent goals (system level) and preferred strategies orientation (strategic level). Once confronted with complementary strategic instructions, they are able to integrate them for more performance. This is in line with Bohns and Higgins (2011) who suggest that, to reap the benefice of complementarity, heterogeneous partners should have a common goal and mobilize their preferred strategies on distinct tasks.

Combining Foci in Teams: Insights from Organization Studies

While RF research at the team-level is scarce in entrepreneurship, this topic has been getting some attention in other disciplines. First, studies from social psychology suggest that teams might experience a convergence of focus through team interaction (Beersma et al, 2013; Florack & Hartmann, 2007; Levine et al, 2000) as well as elements of organizational culture such identity (Faddegon et al, 2008) and climate (Roczniewska et al, 2018). It echoes the work by Wu et al (2008) and Spanjol et al (2011), who suggest that a leader induces a situated RF for their team members. Research from organization studies (Owens & Hekman, 2016; Rietzschel, 2011; Sacramento et al, 2013) confirms that individuals tend to regulate their group-related activities with the same focus, a CRF (see Johnson et al, 2015). CRF is conceptualized as a psychological state that arises through team interactions and becomes (partly) shared among members (van Knippenberg & Mell, 2016) and has been explicitly labelled an emergent state more recently (Owens & Hekman, 2016; Sacramento et al, 2013), i.e. a property of teams that is dynamic in nature and varies as a function of team context, inputs, processes, and outcomes (Marks et al, 2001).

However, extant studies on CRF have two shortcomings. First, the construct of CRF as currently mobilized only reflects sharedness (van Knippenberg & Mell, 2016) amongst team members. We suggest that the hierarchical models of self-regulation might help in unfolding sharedness and diversity inside heterogeneous teams. Second, this stream of research focuses on the impact of CRF rather than its emergence. The convergence of strategic orientation is taken for granted, with the notable exception of Owens and Hekman (2016) who test a model of social contagion where the leader directly influences the strategic orientation of their team members. Beyond the leader’s role, the dynamic processes behind its emergence are still largely unknown (Johnson et al, 2015), whereas the conflicting results from entrepreneurship research hint at the possible hurdles that await team members. If team members mobilize different foci, it is important to understand how tensions unfold (Scholer et al, in press) and are turned into learning opportunities at the benefit of the project (Fischer et al, 2018).

Methodology

Research Strategy: A Qualitative, In-Depth Case Study

Research on CRF is quite scarce and measures the concept using scales at the individual level that are then either averaged (Rietzschel, 2011) or compared to determine the level of sharing (Johnson et al, 2015). It confirms the existence of the concept but falls short in showing how the convergence actually develops and whether a combination of foci occurs. In order to do so, we argue that a qualitative approach is more relevant, and offers methodological fit as this is an emerging concept that we are trying to better understand (Edmondson & McManus, 2007).

Moreover, we chose sustainable entrepreneurship as the setting for our investigation because sustainable ventures should present more salient goal discussions, which can contribute to emphasize RF tensions. Second, this is also the setting of Fischer et al (2018), which studied solo entrepreneurs’ RF during the venture creation process. We extend their qualitative study in two ways: by focusing on the team level as well as by examining what happens after venture creation (see Figure 2 above).

In order to have an in-depth appreciation of team RF emergence, we chose to focus on a single case. The selected case, AgriCOOP, is part of a larger research program that studies the role of collectives in alternative agriculture in Belgium and France. AgriCOOP is a cooperative venture focused on organic, small-scale, sustainable farming and is considered as success stories for the transition movement (Hopkins, 2011). It has also a more specific social finality, which is the integration of individuals who have been experiencing difficulties on the job market. We selected AgriCOOP (Figure 3) because it was identified by our research collective as a sustainable venture, combining social, environmental and economic goals (Muñoz & Cohen, 2018; Shepherd & Patzelt, 2011), and because it was experiencing tensions within the entrepreneurial team. Some members were still eagerly developing the venture and others were voicing their need to slow down the pace, thereby providing cues that our theoretical framework would be of interest.

FIGURE 3

The case-site: AgriCOOP

Thus, by investigating AgriCOOP as a single case, we can have a deeper understanding of the salient regulation focus inside the entrepreneurial team, along the early growth process. While Fischer et al (2018) focused on inception and market entry, we go further in the process to examine early growth, i.e. when scaling becomes an important focus. We pinpoint different elements which, taken together, enable us to characterize early growth both in terms of “a change in amount” (turnover increase) and “a process by which that change is attained” (growing pains) (Davidsson et al, 2006). These elements are presented along our findings (next section) and precise events are recorded (see Figure 4 in the Findings section).

Data Collection

Data collection in AgriCOOP started sixteen months after the venture creation in August 2011. Seventeen semi-structured interviews were conducted with members of the collectives between January 2013 and December 2015, plus a follow-up interview performed in February 2018 (see Table 2). These interviews averaged one hour of duration with the shortest being a half-hour (not with a member of the entrepreneurial team) and the longest two hours. Observations notes and minutes are available for six producers’ meeting from February 2014 to December 2015. The length of the meetings averaged two hours with the shortest about one hour and the longest close to four hours. The various informants and the repeat interviews help cross-checking information and the establishment of a timeline. We also performed a credibility check through a final interview with a member of the collective, during which we discussed the timeline and a draft version of the paper (Yin, 2004), with a focus on the relative importance of promotion and prevention inside the team, as well as changes related to the actualization of RF as the venture grew.

Since the investigation of sustainable entrepreneurship, as well as the underlying motivation and utopia, is vulnerable to social desirability bias, we took several measures to reduce it. We performed face-to-face interviews instead of focus groups of the entrepreneurial team in order to minimize self-presentational concerns (Wooten & Reed, 2000) and to reduce peer pressure (Bristol & Fern, 2003). Most interviews were conducted in individuals’ homes to make them feel at ease. At the beginning of each interview, informants were encouraged to answer honestly, and that there were no right and wrong answers.

The original interview guideline comprises six main topics: entrepreneurship (e.g. Which opportunity/ies was/were the starting point of the collective?); internal coordination (e.g. How did you recruit the co-operators?); external coordination (e.g. Do you try to get known outside of your collective? who are you targeting and why?); organizational culture (e.g. What are the values that you try to sustain inside the collective? What are the specificities of your collective compared to other similar groups?); social movement (e.g. Beyond the operational objectives of the collective, do you have think it is guided by an “utopia”? To what extent does the collective contribute to it? What are your allies in this context? ) and emotions (e.g. You just mentioned this emotion, could you elaborate on a specific event where it was felt, expressed, or shared with others?).

Table 2

List of the qualitative material

Names have been changed to respect the anonymity of respondents; members of the entrepreneurial team are indicated in bold.

The five members of the entrepreneurial team were interviewed, some of them multiple times. Two employees, four cooperators-producers, and one cooperator-consumer were interviewed to better understand the dynamics of the cooperative. The lead entrepreneur was interviewed five times, between January 2013 and March 2015. Additional interviews were semi-directed and focused on the evolution of the venture, follow-up on the emerging tensions discussed in the earlier interview(s) and the way decisions were taken inside the team. This enables to better grasp the evolution of RF in actors’ discourses and their instantiation in actual choices and behaviors.

The members of the entrepreneurial teams were identified as fulfilling at least two out of the three following conditions from the literature: they are founders; they are significant (financial and/or sweat) equity stakeholders; they are strategic decision-makers (Ben-Hafaïedh & Dufays, 2015; Ensley & Hmieleski, 2005). In our case, the members of the entrepreneurial team were all founders and were still part of the collective at the end of the data collection process. As the venture is a cooperative, sweat equity is more relevant than financial equity with regard to the second condition. Finally, they are all strategic decision-makers through, notably, their presence in the administration board and their engagement in the strategic reflection of the venture. Team members were identified based on discussions with the project champion, and through discussions with researchers of the larger research program, thereby providing credibility (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000) to our choices through shared intelligence (Roussel & Wacheux, 2005) and peer debriefing (Dyck et al, 2005). By doing so, we consider that the boundary of teams are a matter of social convention and open to negotiation (Katz & Martin, 1997), but that such conventions can lead entrepreneurial teams to be “seen as a social entity by themselves and by others” (Schjoedt & Kraus, 2009).

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed and then coded using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo. In line with Fischer et al (2018) and Kanze et al (2018), we developed an analysis grid that grasps RF strength in qualitative materials. We do not measure RF as a chronic disposition but rather look at regulatory strength influenced by the specific circumstances of the venture and the interactions of team members (Kanze et al, 2018). According to Scholer et al (in press), manual coding allows for assessing “an individual’s current motivational orientation as captured in his or her speech patterns, regardless of its chronic or situational origin”. Furthermore, we focus on the shared goals and legitimate ways of acting in the ventures, revealing a team-level emergent state as made apparent in individuals’ discourses.

We integrate the hierarchical model of self-regulation by systematically coding excerpts related to the system, strategic and tactic levels. The analysis grid also includes codes related to the tensions discussed by respondents; the articulation of logics; and about the nature of scaling discussed. Table 3 provides a synthesis of our codes, as well as coding examples.

After thematic coding, we looked for relationships between categories and rearranged them hierarchically. We compared the set of categories describing motivational concerns across levels of self-regulation, across our multiple informants, as well as at different moments in time. In doing so, we categorize tactics as promotional or preventive, and identify instances of articulation. Likewise, a picture of shared norms is revealed across team members, as well as its evolution.

Regulatory Foci in Young Collectives

Regulatory Focus before Scaling Up

AgriCOOP’s story starts with the concern for security of its stakeholders, especially the farmers with small scale, organic farming units, who are struggling for viability. As expressed by Leo, the lead entrepreneur: “When I left university, I started working in the sector of work integration. (…) We would organize and follow-up internships in local farms, and from that I realized that most farmers were still wondering ‘how can I make my farm viable? Even if I sell directly to the customers, how can I make sure that I survive in the long run?’” (Leo 2013-12). At the same time, Leo saw an opportunity to stabilize his punctual work integration initiatives into a commercial vehicle and maybe bring security to people with difficult life courses.

Leo is described as an utopist by his partners and is inspired by an ideal vision of agriculture. He sees AgriCOOP as a way to progress towards this ideal (Leo 2013-01): “we might never totally get there, but we will try”. This point of view was shared by the producers who joined him at the start-up stage. He was able to convince more conservative followers that the project is worth fighting for, since it addressed their concerns for security. Furthermore, his prior successes acted as strong positive evidence that danger could be averted: “We said to ourselves that this is not a joke that comes out of nowhere. And we are not going to waste our time by listening to him. We know that he is serious, that if he has the possibility, he will go to the end [of the project]” (Paula 2014-01).

The shared utopia with the producers is translated into an economic model that works for small-scale, organic, rural agriculture. With consumers, who see themselves as consumer activists (“consom’acteur” in French), the shared goal becomes a better access to good agricultural products at a fair price (for the producer). However, other aspects of Leo’s utopia were less obvious, like the work integration finality. Leo had to convince his followers that the underlying values were the same, that the creation of social links through all means possible was the way to go, and he succeeded. In this launching phase, it seems that there is room for all aspirations and goals, as long as they are not conflicting in terms of values. Shared goals are expressed in terms of both security (for the producers and the workers) and ideals (for society).

From there, Leo’s strategic orientation is eagerness: “to get to their dreamed model [of agriculture]” (Leo 2013-01). He starts experimenting “bits and bobs” (Leo 2013-01) and steadily develops AgriCOOP. Eagerness is instantiated in promotional tactics such as the creation of jobs as an important milestone, growing the number of baskets sold to customers, and maximizing the number of people impacted by their initiative and offering flexible purchase subscriptions. This concurs with Kanze et al (2018) and with Fischer et al (2018) who show that, in sustainable entrepreneurship projects, the preventive identification of the social and environmental issues at the origin of the venture is followed by a promotional focus for venture roll-out (see Figure 4).

Regulatory Focus at Scaling-Up

Vigilance Gaining Momentum

The first interview of the lead entrepreneur was performed sixteen months after the creation of the cooperative. At that moment, promotional tactics are still largely brought up by the lead entrepreneur, as well as other team members like Paula, who suggest that sharing between members is the most interesting part of the adventure so far (Paula 2014-01). However, a prevention focus gains momentum and eagerness is steadily questioned by members of the entrepreneurial team. “The financial situation of the cooperative is in danger. We need to make strategic decisions” (Loic 2015-01). It is about making “real decisions” (Paula 2014-12), notably in terms of acceptable commercial modalities and internal coordination between producers. Table 4 illustrates how promotional tactics, such as sharing inside and outside the venture, are first challenged as adequate tactics for AgriCOOP and then adapted to, or even replaced by, tactics that better serve a vigilant approach.

A first set of promotional tactics centers on the creative bricolage of Leo who experiments different business models and imagines new revenue flows (see Table 4). Some preventive elements are articulated to the promotional tactics, such as “experimenting [prom/tact] about costs and norms [prev/tact]” (Leo 2013-12). Considering the hierarchical model of regulation (Scholer & Higgins, 2011), multiple tactics are serving the eager development of the venture. At the same time, a growing concern for vigilance is emerging, notably linked to a heavy real-estate investment (see Figure 4). A more rigorous and transparent approach is called for inside AgriCOOP, which questions the informal tactics of Leo. The assessment is shared by members of the entrepreneurial team who identify ways to help make AgriCOOP more professional. The main imperative steadily becomes vigilance, supported by formalization rather than improvisation. After the new billing system at the end of 2014, a cost accounting system is implemented in 2015, allowing for a better identification [of] (un)profitable activities of the venture.

Table 3

Synthesis of the analytical themes and coding examples

FIGURE 4

A model of regulatory focus for sustainable scaling

Industry and Competition: * New competitor arrives on the market; *** Market saturation Internal events: ** Purchase of the building; **** Cost accounting software implementation

The same concern for vigilance is brought up when challenging the promotional tactics of diversification and business extension (Kanze et al, 2018). As expressed by Paula, a frontline arises between those who want to stabilize the activities, and those who want to keep developing the cooperative. She considers the latter as a “jump in the dark” (Paula 2014-12), excessive and dangerous. Steadily, even the project champion is rallied to this vigilant approach. “Leo was adept of an ‘infinite opening’; we had a hard time making him understand that it was the wrong approach. Now, he is seeing himself the limits of such a system” (Loic 2015-01). Accordingly, the number of development projects shrunk (Thibault 2018-02), as AgriCOOP rather focuses on the consolidation of its activities. Moreover, the remaining extension projects are now at the service of vigilance. The cooperative is planning the opening of two new direct sales location in two nearby cities. However, these openings are no longer at the service of the eager development of the venture. It is a strategic move to counteract the threats of competitors in those locations (see Table 4).

Table 4

Emergence of vigilance: challenging eagerness and framing tactics at the service of vigilance

Likewise, the promotional tactic of networking (Kanze et al, 2018) is challenged by the vigilance concerns. Inside the cooperative, sharing between members is still met with enthusiasm. However, it is now mobilized as a peer control mechanism (see Table 4). Members would plan visits to the different farming units, use it as an opportunity to share best practices, and to control that the farmers are meeting the cooperative’s requirements. Sharing with outsiders, on the contrary, is strongly challenged. Paula and Loïc ask Leo to slow down his missionary activities, unless a direct contribution to AgriCOOP is possible. At the same time, Leo realizes that new competitors are popping-up in AgriCOOP’s market and that some had met with AgriCOOP’s team members and are applying its best practices in their own projects. Leo thus grows a greater concern for vigilance too. Sharing opportunities with local entrepreneurs is now considered as a competitive threat rather than an opportunity. AgriCOOP is still active in the transition ecosystem. However, such activities are framed as strategic positioning: to be recognized as the true pioneer on the market (Thibault 2018-02).

Reaping the Benefits of Heterogeneity

In the transition phase, “growing pains” are not experienced the same way by different team members. Leo adapts his tactics but still pursues an eager development of the venture. He is aware of “the risk of losing product quality if there is an increase in the quantity of baskets sold” (Leo 2013-02), but addresses this risk with more diversifications: “We do not want to be a “basket factory”. There, for the moment, I am at 550-600 basket equivalents, I want to stay at this threshold [prev] and develop the direct sales store instead [prom]” (Leo 2013-01). Furthermore, he puts in place an after-sales service. While the number of basket stays stable, the status quo is pushed forward by enhancing the quality through the feedback of customers. This combination of conservative and risky tactics is facilitated by team exchanges, which help members contemplate tactics that would not have been their first choice (see Table 5). Some team members are convinced of the interest of a conservative tactic, such as the scientific analysis of the soil, by discussing the ways it contributes to the ideals of organic agriculture. Likewise, promotional tactics such as diversification are adopted by more conservative members by addressing their concern for security.

However, by keeping on an eager development, Leo creates tensions inside the entrepreneurial team. As showed in the previous section, promotional tactics are not challenged per se by Loic and Paula, but only when they are not serving a vigilant approach. They target the strategic level, which is unchanged for Leo – at least at first. The tensions are directly addressed during the board meetings and executive boards, and crystallize in “a frontline between those who want to run the business and those who want to stick to principles” (Loic 2015-01). Indeed, decision making in AgriCOOP is facilitated by the sociocracy principles, which encourage each member to voice their concerns about a specific decision and to form a consensus during team meetings. Leo is welcoming such dissent: “That’s interesting... They are upset with me ‘Good God what did you do? Oh no, what did you do? Why this? Oh no not that!’. And there, it becomes interesting. It means that the group is being empowered. They are no longer saying ‘Yes, Leo said so…!’,... and they believe in the project” (Leo 2014-02). As a result, both eagerness and vigilance are challenged during meetings (see Table 5) and a consensus is reached about the adequate solutions. We find that the team is steadily able to legitimize vigilance as the adequate strategic orientation. Leo is indeed “slowing things down” (Thibault 2018-02) and thus “seeing the limit of the [eager] system” as suggested earlier by Loic (2015-01).

Team members use different resources to build a consensus, the first one being the affective commitment of the team which stems from the enthusiastic beginning of the venture (Johnson et al., 2010) and is still salient when tensions arise: “the team is almost unchanged from the beginning. There is still a sense of belonging. We knocked out a lot of… [work]... we went a long way together. We all have mutual recognition and it helps to weld a team.” (Loic 2015-01). Because of this affective commitment, members voice their concerns in a safe climate. However, it is a double-edged sword: “the cohesion of the board remains the priority. When one or two persons defend a cause and they are a minority, they let it go” (Loic 2015-01). Likewise, Catty observes that “Leo will never command, or force, anything. (…) It could be the shattering of the project. If he wants to systematically go where the group does not want to. It’s not okay” (2015-07).

A second important resource is the repertoire of shared goals. Team members use them to signal their loyalty to the project, protect the cohesion of the team, and challenge the strategic and tactic levels rather than the system level. As expressed by Loic, “everybody agrees on ‘being social’ in the collective. The issue is about agreeing on how to do it concretely” (2015-01). Likewise, Paula suggests that “in the end, we all agree, but it’s a question of timing: Leo wants to run, and the producers do not want to run” (2014-12). However, evidence suggests that shared goals are still being pressured. For instance, “being social” is quite ambiguous. Work integration is one way of doing it, but not the only one. As a result, we see that the social finality – in terms of work integration – is steadily challenged inside AgriCOOP, up until the latest general assembly, when producers finally “sounded the alarm” (Thibault 2018-02).

To conclude, we suggest that the convergence at the strategic level is reached through voicing concern about current problems and tactics that are not at the service of vigilance (see Figure 5). By contrast, the combination at the tactic level is made possible when voicing solutions: framing a risky tactic to address a security need, and, conversely, a conservative tactic to address a growth need. In other words, new actions and solutions are voiced by team members and legitimized through the existing shared goals. This final situation is represented in Figure 5, showing the multiple shared goals (system level), the collective strategic orientation (strategic level), and the articulation of tactics at the service of vigilance (tactic level).

Discussion

In AgriCOOP, we examined the articulation of logics inside the entrepreneurial team, as well as the emergence of a CRF at the team-level as team members progressively challenge the eager development of the venture and legitimize a vigilant approach. A frontline appears inside the entrepreneurial team, which crystallises the confrontation of strategic orientations. We suggest that a consensus at the strategic level reduces such tensions while still reaping the benefits of heterogeneity. This is for example the case when a team member articulates risky and conservative tactics at the service of the emerging team strategic orientation. While previous works consider RF as a single construct, we suggest that the distinction of regulation levels (system, strategic, tactical) allows for a more comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurial action.

Moreover, our findings highlight the role of dissent inside the team, which is used to question tactics when they are not at the service of the “right” strategic orientation. While the emergence of this faultline is associated to growing conflicts, the team members use the affective commitment (Johnson & Yang, 2010) that binds them together as an important resource to turn it into a CRF. More precisely, we identify two types of voices that allow to develop and maintain RF at the team-level. First, a prohibitive voice contributes to the strategic convergence inside entrepreneurial teams. Prohibitive voice addresses past or current problems and concerns that could otherwise lead to harmful outcomes for the organization (Liang et al, 2012; Lin & Johnson, 2015). In this case, it means challenging current tactics and strategies until the emergence of a consensus. Second, we show that a promotive voice influences the combination of foci at the tactic level. Promotive voice is defined as the voicing of new opportunities and initiatives to improve future organizational functioning (Liang et al, 2012; Lin & Johnson, 2015). By framing risky tactics to adress security needs (or, conversely, conservative tactics to adress growth needs), team members sustain the articulation of foci, beyond a mere strategic consensus. We thus theorize that each type of voice contributes uniquely to the sharedness and diversity of a team-level RF. Prohibitive voice only would fail short in reaping the benefit of diversity. Promotive voice without consensus would deplete the affective ressources of the collective.

Table 5

Heterogeneity of regulatory focus in the entrepreneurial team

FIGURE 5

Hierarchical CRF and dynamics between levels

As a result, we see that RF, at the team-level, is a temporary and situated adhesion to certain goals and means to reach them, in a given time and space. As an emergent state, it is dynamic in nature (Marks et al, 2001), influenced by the internal circumstances of the project such as growing pains (Flamholtz & Randle, 2000), external factors such as competition, as well as team processes such as team prohibitive and promotive voices.

Our research thus contributes to RFT by further elaborating on team RF as an emergent state, showing the importance of considering the three levels of regulation, and suggesting factors that enable to benefit from heteregenous team. We show that team RF is a three-dimensional construct that involves shared mental representation of goals (ought and ideals), shared representation of goal pursuit (vigilance vs. eagerness), and articulation at the tactical level (e.g., a promotional tactic at the service of vigilance). Furthermore, we theorize the team processes that influence each level, as well as the dynamics at stake. In particular, we suggest that the articulation at the tactical level might weaken over time, as imperatives at the strategic pressure shared goals. In terms of methods, it means that CRF should not simply be computed as an average of the individual members RF but be examined as an emergent state, with three levels of regulation that are interrellated.

Finally, our research contributes to the field of sustainable entrepreneurship by examining the development process beyond inception and identifying a second transition phase in terms of salience of RF and its relationship with early growth (see Figure 4). We developed a regulatory-based explanation of the transition experienced by collectives in sustainable entrepreneurship. Using the RFT as a new prism to understand tensions inside young ventures, we might provide entrepreneurs (and their advisors) with a new way to look at their frustrations and challenges. We show that growing pains are associated with a greater concern for vigilance, which is instantiated into conservative tactics such as the implementation of a cost accounting software, transparent billing systems, and more formalization. Such a shift from promotion to prevention after venture creation is thus a way to address the new requirement of scaling-up and the professionalization of the venture (Flamholtz & Randle, 2000). However, the specific pattern of transition might differ in some predictable ways in other cases, depending on environemental and internal contingencies. In this research, we chose to focus on a single case in order to have in-depth understanding of the team RF. Future research would look into more cases to refine our findings and the appreciation of regulation at different levels. It would also be interesting to examine whether cases outside of sustainable entrepreneurship present similar patterns.

Our research has some limitations, which, as often is the case, open paths for future research. We examined team RF as an emergent state in a specific transition period and reconstructed, based on our empirical material, the evolution of team RF through the process of sustainable entrepreneurship from the beginnings to the early growth stage. This calls for a longitudinal research design in order to be able to fine track the dynamics along the three levels of self-regulation as well as the evolution of team RF at later developmental stages. Moreover, future research design might include a measure of output, such as team satisfaction, product innovativeness, or social impact. It means mobilizing the IMOI (input-mediator-output-input) framework recommended for the study of team emergent states (Ilgen et al, 2005). This is in line with Scholer et al (in press), who argue that understanding the conditions under which self-regulation diversity is beneficial or problematic is an exciting direction for future work on teams. Finally, we confirm that an entrepreneurial team can switch focuses. This property is interesting in many respects. Notably, it enables a new venture to alternate eager and vigilant phases and thus grow through stages of punctuated equilibrium. However, entrepreneurial teams might meet blocking points that hinder oscillations and bring rigidity to the venture. Further study might focus on such factors.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Group of Interdisciplinary Research in Agroecology, and more specifically Denise Van Dam, Jean Nizet, and Thomas Pongo for access to data and useful discussions. We also extend our thanks to the anonymous reviewers, EV-3 in particular, for their precise and constructive feedback.

Biographical notes

Julie Hermans is Assistant Professor of Entrepreneurship at the UCLouvain, Louvain Research Institute in Management and Organization. Her research interests focus on entrepreneurial decision making and tensions management, from a cognitive perspective.

Cyrine Ben-Hafaïedh is Assistant Professor in Entrepreneurship & Strategy at IÉSEG School of Management (Paris campus) and member of the LEM-CNRS research laboratory. Her research interests are collective entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial teams in particular, that she studies in different contexts. Cyrine is board member of the European Council for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (ECSB) and part of the group of administrators of the French Academy of Entrepreneurship and Innovation (AEI).

Bibliography

- Angel, Vincent; Hermans, Julie. (2019). “Théorie des Focus Régulateurs: Etat de l’Art et Défis pour la Cognition Entrepreneuriale”. Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat, Vol. 18, N° 1, p. 23-72.

- Baas, Matthijs; De Dreu, Carsten KW; Nijstad, Bernard A. (2011). “When prevention promotes creativity: the role of mood, regulatory focus, and regulatory closure”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 100, N° 5, p. 794.

- Beersma, Bianca; Homan, Astrid C; Van Kleef, Gerben A; De Dreu, Carsten KW. (2013). “Outcome interdependence shapes the effects of prevention focus on team processes and performance”. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, Vol. 121, N° 2, p. 194-203.

- Ben-Hafaïedh, Cyrine. (2017). Entrepreneurial Teams Research in Movement. In Research Handbook on Entrepreneurial Teams: Theory and Practice, ed. Ben-Hafaïedh, Cyrine; Cooney, Thomas M. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing

- Ben-Hafaïedh, Cyrine; Dufays, Frédéric. (2015). Entrepreneurial Teams in Social New Venture Creation: A Research Agenda. Presented at International Council for Small Business 50th anniversary conference, June 6-9, Dubai

- Bohns, Vanessa K; Higgins, E Tory. (2011). “Liking the same things, but doing things differently: Outcome versus strategic compatibility in partner preferences for joint tasks”. Social Cognition, Vol. 29, N° 5, p. 497-527.

- Bohns, Vanessa K; Lucas, Gale M; Molden, Daniel C; Finkel, Eli J; Coolsen, Michael K, et al. (2013). “Opposites fit: Regulatory focus complementarity and relationship well-being”. Social Cognition, Vol. 31, N° 1, p. 1-14.

- Bristol, Terry; Fern, Edward F. (2003). “The effects of interaction on consumers’ attitudes in focus groups”. Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 20, N° 5, p. 433-454.

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E. T.; Low, M. B. (2004). “Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 19, N° 2, p. 203-220.

- Burmeister-Lamp, Katrin; Lévesque, Moren; Schade, Christian. (2012). “Are entrepreneurs influenced by risk attitude, regulatory focus or both? An experiment on entrepreneurs’ time allocation”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 27, N° 4, p. 456-476.

- Cantor, Nancy; Kihlstrom, John F. (1987). Personality and social intelligence. Pearson College Division.

- Choi, Young Rok; Lévesque, Moren; Shepherd, Dean A. (2008). “When should entrepreneurs expedite or delay opportunity exploitation?”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 23, N° 3, p. 333-355.

- Cornwell, James FM; Higgins, E Tory. (2015). “Approach and avoidance in moral psychology: Evidence for three distinct motivational levels”. Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 86, p. 139-149.

- Davidsson, Per; Achtenhagen, Leona; Naldi, Lucia. (2006). What Do We Know About Small Firm Growth? In The Life Cycle of Entrepreneurial Ventures, ed. Parker, Simon C., pp. 361-398: Springer

- Dees, G. 1998. The meaning of “social entrepreneurship’. available https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/knowledge_items/the-meaning-of-social-entrepreneurship/

- Denzin, N. K.; Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Dyck, Bruno; Starke, Frederick A; Mischke, Gary A; Mauws, Michael. (2005). “Learning to build a car: an empirical investigation of organizational learning”. Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 42, N° 2, p. 387-416.

- Edmondson, Amy C.; McManus, Stacy E. (2007). “Methodological fit in management field research”. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, N° 4, p. 1155-1179.

- Ensley, Michael D.; Hmieleski, K. M. (2005). “A comparative study of new venture top management team composition, dynamics and performance between university-based and independent start-ups”. Research Policy, Vol. 34, N° 7, p. 1091-1105.

- Faddegon, Krispijn; Scheepers, Daan; Ellemers, Naomi. (2008). “If we have the will, there will be a way: Regulatory focus as a group identity”. European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 38, N° 5, p. 880-895.

- Fischer, Denise; Mauer, René; Brettel, Malte. (2018). “Regulatory focus theory and sustainable entrepreneurship”. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, Vol. 24, N° 2, p. 408-428.

- Flamholtz, E. G.; Randle, Y. (2000). Growing Pains: Transitioning from an Entrepreneurship to a Professionally Managed Firm. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Florack, Arnd; Hartmann, Juliane. (2007). “Regulatory focus and investment decisions in small groups”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 43, N° 4, p. 626-632.

- Förster, Jens; Higgins, E Tory; Bianco, Amy Taylor. (2003). “Speed/accuracy decisions in task performance: Built-in trade-off or separate strategic concerns?”. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 90, N° 1, p. 148-164.

- Fridman, Ilona; Scherr, Karen A; Glare, Paul A; Higgins, E Tory. (2016). “Using a Non-Fit Message Helps to De-Intensify Negative Reactions to Tough Advice”. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 42, N° 8, p. 1025-1044.

- Higgins, E Tory. (1997). “Beyond pleasure and pain”. American Psychologist, Vol. 52, N° 12, p. 1280-1300.

- Higgins, E Tory. (1998). “Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle”. Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 30, p. 1-46.

- Higgins, E Tory; Molden, Daniel C. (2003). “How strategies for making judgments and decisions affect cognition: Motivated cognition revisited”. Foundations of social cognition: A festschrift in honor of Robert S. Wyer, Jr, edited by Galen V. Bodenhausen, Alan J. Lambert, Vol., p. 211-235.

- Higgins, E Tory; Spiegel, Scott. (2004). Promotion and prevention strategies for self-regulation: A motivated cognition perspective In Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications, ed. Baumeister, R. F.; Vohs, K. D., pp. 171-187. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press

- Hite, Julie M; Hesterly, William S. (2001). “The evolution of firm networks: From emergence to early growth of the firm”. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 22, N° 3, p. 275-286.

- Hmieleski, Keith M; Baron, Robert A. (2008). “Regulatory focus and new venture performance: A study of entrepreneurial opportunity exploitation under conditions of risk versus uncertainty”. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, Vol. 2, N° 4, p. 285-299.

- Hopkins, Rob. (2011). The Transition Companion: Making Your Community More Resilient in Uncertain Times. pp. 240. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Ilgen, Daniel R.; Hollenbeck, John R.; Johnson, Michael; Jundt, Dustin. (2005). “Teams in organizations: From Input-Process-Output Models to IMOI Models”. Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 56, N° 1, p. 517-543.

- Johnson, Mark; Monsen, Erik W; MacKenzie, Niall G. (2017). “Follow the Leader or the Pack? Regulatory Focus and Academic Entrepreneurial Intentions”. Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 34, N° 2, p. 181-200.

- Johnson, P. D.; Smith, M. B.; Wallace, J. C.; Hill, A. D.; Baron, R. A. (2015). “A Review of Multilevel Regulatory Focus in Organizations”. Journal of Management, Vol. 41, N° 5, p. 1501-1529.

- Johnson, Russell E; Yang, Liu-Qin. (2010). “Commitment and motivation at work: The relevance of employee identity and regulatory focus”. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 35, N° 2, p. 226-245.

- Kanze, D., Huang, L., Conley, M. A., & Higgins, E. T. (2018). We Ask Men to Win and Women Not to Lose: Closing the Gender Gap in Startup Funding. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 61, N° 2, p. 586-614.

- Katz, J Sylvan; Martin, Ben R. (1997). “What is research collaboration?”. Research Policy, Vol. 26, N° 1, p. 1-18.

- Klotz, Anthony C.; Hmieleski, Keith M.; Bradley, Bret H.; Busenitz, Lowell W. (2014). “New venture teams: A review of the literature and roadmap for future research”. Journal of Management, Vol. 40, N° 1, p. 226-255.

- Levine, John M; Higgins, E Tory; Choi, Hoon-Seok. (2000). “Development of strategic norms in groups”. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, Vol. 82, N° 1, p. 88-101.

- Liang, Jian; Farh, Crystal IC; Farh, Jiing-Lih. (2012). “Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination”. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 55, N° 1, p. 71-92.

- Lin, S. H.; Johnson, R. E. (2015). “A suggestion to improve a day keeps your depletion away: Examining promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors within a regulatory focus and ego depletion framework”. Journal of Applied psychology, Vol. 100, N° 5, p. 1381-1397.

- Marks, Michelle A.; Mathieu, John E.; Zaccaro, Stephen J. (2001). “A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes”. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 26, N° 3, p. 356-376.

- McMullen, Jeffery S; Shepherd, Dean A; Patzelt, Holger. (2009). “Managerial (in) attention to competitive threats”. Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 46, N° 2, p. 157-181.

- Molden, Daniel C; Lee, Angela Y; Higgins, E Tory. (2008). Motivations for promotion and prevention In Handbook of motivation science, ed. Shah, James Y.; Gardner, Wendi L., pp. 169-187. New York: Guilford Press

- Muñoz, P. & Cohen, B. (2019). “Sustainable Entrepreneurship Research: Taking Stock and looking ahead”. Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 27 N° 3, p.300-322.

- Owens, Bradley P; Hekman, David R. (2016). “How does leader humility influence team performance? Exploring the mechanisms of contagion and collective promotion focus”. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 59, N° 3, p. 1088-1111.

- Pollack, Jeffrey M; Forster, William R; Johnson, Paul D; Coy, Anthony; Molden, Daniel C. (2015). “Promotion-and prevention-focused networking and its consequences for entrepreneurial success”. Social Psychological and Personality Science, Vol. 6, N° 1, p. 3-12.

- Rietzschel, Eric F. (2011). “Collective regulatory focus predicts specific aspects of team innovation”. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, Vol. 14, N° 3, p. 337-345.

- Roczniewska, Marta; Retowski, Sylwiusz; Higgins, E Tory. (2018). How Person-Organization Fit Impacts Employees’ Perceptions of Justice and Well-being. In Frontiers in Psychology. Vol 8, Jan 9, 2018, Article 2318.

- Roussel, Patrice; Wacheux, Frédéric. (2005). Management des ressources humaines: Méthodes de recherche en sciences humaines et sociales. De Boeck Supérieur.

- Sacramento, Claudia A; Fay, Doris; West, Michael A. (2013). “Workplace duties or opportunities? Challenge stressors, regulatory focus, and creativity”. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, Vol. 121, N° 2, p. 141-157.

- Schjoedt, L.; Kraus, S. (2009). “Entrepreneurial teams: definition and performance factors”. Management Research News, Vol. 32, N° 6, p. 513-524.

- Scholer, Abigail A; Cornwell, James F.M.; Higgins, E Tory. (in press). Regulatory Focus Theory and Research: Catching Up and Looking Forward After 20 Years In Oxford Handbook on Human Motivation, ed. Ryan, R. Oxford: Oxford Publishing

- Scholer, Abigail A; Higgins, E Tory. (2008). Distinguishing levels of approach and avoidance: An analysis using regulatory focus theory In Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation., ed. Elliot, A. J., pp. 489-503. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press

- Scholer, Abigail A; Higgins, E Tory. (2010). “Regulatory focus in a demanding world”. Handbook of personality and self-regulation, Vol 8, Jan 9, 2018, Article 2318., p. 291-314.

- Scholer, Abigail A; Higgins, E Tory. (2011). Promotion and prevention systems: Regulatory focus dynamics within self-regulatory hierarchies In Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications, 2nd ed., ed. Vohs, K. D.; Baumeister, R. F., pp. 143-161. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press

- Scholer, Abigail A; Zou, Xi; Fujita, Kentaro; Stroessner, Steven J; Higgins, E Tory. (2010). “When risk seeking becomes a motivational necessity”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 99, N° 2, p. 215.

- Shepherd, Dean A.; Patzelt, Holger. (2011). “The New Field of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Studying Entrepreneurial Action Linking “What Is to Be Sustained” With “What Is to Be Developed””. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 35, N° 1, p. 137-163.

- Simmons, Sharon A; Carr, Jon C; Hsu, Dan K; Shu, Cheng. (2016). “The regulatory fit of serial entrepreneurship intentions”. Applied Psychology, Vol. 65, N° 3, p. 605-627.

- Spanjol, Jelena; Tam, Leona; Qualls, William J; Bohlmann, Jonathan D. (2011). “New product team decision making: Regulatory focus effects on number, type, and timing decisions”. Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 28, N° 5, p. 623-640.

- Spiegel, Scott; Grant‐Pillow, Heidi; Higgins, E Tory. (2004). “How regulatory fit enhances motivational strength during goal pursuit”. European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 34, N° 1, p. 39-54.

- Tumasjan, A.; Braun, R. (2012). “In the eye of the beholder: How regulatory focus and self-efficacy interact in influencing opportunity recognition”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 27, N° 6, p. 622-636.

- vanKnippenberg, Daan; Mell, Julija N. (2016). “Past, present, and potential future of team diversity research: From compositional diversity to emergent diversity”. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, Vol. 136, p. 135-145.

- Wallace, J Craig; Johnson, Paul D; Frazier, M Lance. (2009). “An examination of the factorial, construct, and predictive validity and utility of the regulatory focus at work scale”. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 30, N° 6, p. 805-831.

- Wallace, J Craig; Little, Laura M; Hill, Aaron D; Ridge, Jason W. (2010). “CEO regulatory foci, environmental dynamism, and small firm performance”. Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 48, N° 4, p. 580-604.

- Wooten, David B; Reed, Americus. (2000). “A conceptual overview of the self‐presentational concerns and response tendencies of focus group participants”. Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 9, N° 3, p. 141-153.

- Wu, Cindy; McMullen, Jeffery S; Neubert, Mitchell J; Yi, Xiang. (2008). “The influence of leader regulatory focus on employee creativity”. Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 23, N° 5, p. 587-602.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Julie Hermans est Professeure Assistante en Entrepreneuriat à l’UCLouvain, Louvain Research Institute in Management and Organization. Sa recherche se focalise sur la prise de décision entrepreneuriale et la gestion des tensions, d’un point de vue cognitif.

Cyrine Ben-Hafaïedh est Professeure Assistante en Entrepreneuriat et Stratégie à l’IÉSEG School of Management (campus de Paris) et membre du Laboratoire de recherche LEM-CNRS. Sa recherche se focalise sur l’entrepreneuriat collectif, les équipes entrepreneuriales plus particulièrement, qu’elle étudie dans différents contextes. Elle est membre du Conseil d’Administration du European Council for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (ECSB) et du groupe d’Administrateurs de l’Académie de l’Entrepreneuriat et de l’Innovation (AEI).

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Julie Hermans es profesora asistente de emprendimiento en UCLouvain, Louvain Research Institute in Management and Organization. Sus intereses de investigación se centran en la toma de decisiones empresariales y la gestión de tensiones, desde una perspectiva cognitiva.

Cyrine Ben-Hafaïedh es profesora asistente en emprendimiento y estrategia en IÉSEG School of Management (campus de París) y miembro del laboratorio de investigación LEM-CNRS. Sus intereses de investigación son el emprendimiento colectivo, en particular los equipos emprendedores, que ella estudia en diferentes contextos. Cyrine es miembro del Consejo de Administración consejo del European Council for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (ECSB) y forma parte del grupo de administradores de la Academia Francesa de Emprendimiento e Innovación (AEI).

List of figures

FIGURE 1

Regulatory focus: articulating congruent needs, goals and strategies

FIGURE 2

A model of regulatory focus in sustainable ventures

FIGURE 3

The case-site: AgriCOOP

FIGURE 4

A model of regulatory focus for sustainable scaling

FIGURE 5

Hierarchical CRF and dynamics between levels

List of tables

Table 1

A hierarchical model of regulatory focus

Table 2

List of the qualitative material

Table 3

Synthesis of the analytical themes and coding examples

Table 4

Emergence of vigilance: challenging eagerness and framing tactics at the service of vigilance

Table 5

Heterogeneity of regulatory focus in the entrepreneurial team