Abstracts

Abstract

Whereas Gillian Beer’s Darwin’s Plots traces the sometimes-indirect impact of Charles Darwin on a number of major Victorian novels, this article proposes to examine the fictions of two writers very directly concerned with evolution, but preferring what they took to be Erasmus Darwin’s version of it. The first of these is Samuel Butler, who progressed from sympathetically spoofing Charles’ evolutionism to bitterly attacking his theory of natural selection, holding up what he believed to be the goal-directed evolutionary model of Erasmus and others instead. Along with a glance at Butler’s polemical evolutionary works, his two major novels Erewhon and The Way of All Flesh are explored both for their critiques of Charles and the ways they may have drawn on Erasmus, particularly his Botanic Garden and Zoonomia.

The other writer with links to Erasmus is George Bernard Shaw, the Preface to whose ambitious five-play cycle Back to Methuselah denounces Charles and explicitly praises both Butler and Erasmus’s Zoonomia, while its plot bears interesting similarities to Erasmus’s final evolutionary poem, The Temple of Nature. Since it is not certain Shaw had read this poem the following comparison runs the unproved possibility of direct influence in parallel with Viktor Shklovsky’s idea of the transmission of literary forms in a series of “knight’s moves,” “discontinuous but teleological” as Fredric Jameson calls them. While the parallels between the two works are striking, including the political contexts to which they are responding, the article finally distances Erasmus’s full-blooded but non-exclusory evolutionism from the hints of “survival of the fittest” Social-Darwinism to be found in Shaw’s (and to a lesser extent Butler’s) works.

Article body

In Darwin’s Plots, Gillian Beer shows how arguments and metaphors from Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species weave themselves into such fictional strategies as the focus on variation within apparent resemblance in George Eliot’s Middlemarch and the coexistence of present-moment pleasure and future-directed plot in a range of Hardy’s novels, and may themselves owe something to the apparently random multiplication of characters—eventually giving way to the demonstration of numerous intricate connections through familial descent—in earlier Victorian novels such as Dickens’s Bleak House (Beer 139-68, 220-41, 42-3). In this essay I propose to take the endlessly suggestive implications of Beer’s title in a different direction, by looking at some narrative plots rather more crudely and directly concerned with the issue of evolution, but less under the aegis of Charles Darwin than his equally evolutionist grandfather. As well as those of Erasmus Darwin himself, I shall focus on the belatedly Erasmian plots of the nineteenth-century novelist Samuel Butler and the twentieth-century playwright George Bernard Shaw, both of whose polemical writings champion the evolutionism of Erasmus’s prose treatise Zoonomia, Part One (1794) in preference to his grandson’s work, but some of whose fictions can also be seen as somewhat more elusively inscribed with images and plot-devices from his major poems The Botanic Garden, Parts One and Two (1791) and The Temple of Nature, or The Origin of Society (1803).

After his high-point of fame in the 1790s, Erasmus Darwin’s literary and scientific reputation collapsed in the nineteenth century[1] to the extent that by 1880, according to Butler, “ninety-nine out of every hundred of us had never so much as heard of the Zoonomia,” and saw Erasmus only as “a forgotten minor poet” (Unconscious Memory 8). It would be going too far to say a similar fate has now overtaken Shaw and Butler in their turn, but their reputations as impish contrarians arguably do currently weigh against their works being taken as seriously as they once were. Are they primarily “literature” or amusingly dressed-up social/scientific theory, or do they fall, like Erasmus Darwin’s poetry, into the strange twilit limbo of deliberately fanciful “didactic imaginative literature”? In any case, they formed a narrow but significant conduit for the transmission of Erasmus’s firmly non-theist brand of evolutionism through the nineteenth century into the twentieth, presented as a kind of counter-stream to both the creationism of orthodox religion and the perceived arbitrariness of Charles-Darwinian Natural Selection.

I. Samuel Butler: Erewhon and the war against Charles

If on my descent to the nether world I were to be met and welcomed by the shades of those to whom I have done a good turn while I was here, I should be received by a fairly illustrious crowd. There would be … Buffon, Erasmus Darwin and Lamarck; … and I shall not take it too much to heart if the shade of Charles Darwin glides gloomily away when it sees me coming.

Butler, Note-Books 378

In several books beginning with Evolution Old and New: Or, The Theories of Buffon, Dr. Erasmus Darwin, and Lamarck, as Compared with That of Mr. Charles Darwin (1879), Samuel Butler argues that the Darwin whose evolutionism we ought to be following is not Charles, but Erasmus. While giving Jean-Baptiste Lamarck the prime credit for his developing conviction that organisms strive for and transmit their own necessary adaptations, Butler also hails Erasmus Darwin as a major evolutionary pioneer and quotes extensively from the most relevant part of his Zoonomia: Section 39, “Of Generation” (Evolution Old and New 233-4).[2]

Butler’s hostility to Charles, and his frequent use of Erasmus as a stick to beat him with, developed only gradually. In his brief comic essay “Darwin among the Machines” (published in The Press, New Zealand, 1863), Butler depicts the evident development of machines towards greater and greater efficiency as the next stage in (Charles-) Darwinian evolution, which will eventually lead to mankind’s total enslavement by the mechanical objects they already devote so much of their lives to servicing. The only solution is to destroy all existing machines now, and invent no new ones. Expanding on this article, three chapters of Butler’s fantasy-novel Erewhon (1872) are devoted to explaining how the inhabitants of his imaginary country Erewhon (i.e. “nowhere,” neither quite a utopia nor dystopia) have already taken this step, confining the evidence of their previous ingenuity to a carefully guarded machine-museum after one of their professors has argued

that the machines were ultimately destined to supplant the race of man, and to become instinct with a vitality as different from, and superior to, that of animals, as animal to vegetable life. So convincing was his reasoning [that] they made a clean sweep of all machinery … , and strictly forbade all further improvements and inventions.

Butler, Erewhon 97

Initially hugely impressed by Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, Butler denied that this inclusion of machines in the story of evolutionary struggle was anti-Darwinian satire (Erewhon, Preface to Second Edition 29-30). He had earlier written a strong defence of Origin which Darwin himself appreciated (see Raby 88) and Erewhon shows a close grasp of that book’s detailed arguments, for instance in a discussion of the useless “little protuberance on the bottom of the bowl” of the protagonist’s tobacco-pipe, from which a particularly brainy Erewhonian correctly deduces that earlier, heavier pipes must have had larger such protuberances for resting them on tables, and links this to the fact that, just as in biological evolution, “the presence of rudimentary organs which existed in many machines feebly developed and perfectly useless, yet serv[ed] to mark descent from an ancestor to whom the function was actually useful” (Erewhon 214). This fairly directly echoes Charles Darwin’s remark near the end of Origin that

On the view of descent with modification, we may conclude that the existence of organs in a rudimentary, imperfect, and useless condition … far from presenting a strange difficulty, as they assuredly do on the ordinary doctrine of creation, might even have been anticipated, and can be accounted for by the laws of inheritance.

C. Darwin, On the Origin of Species 455-6

However, while Butler clearly has such passages of Charles’s directly in his sights, a similar discussion of rudimentary organs also marks Erasmus Darwin’s first-ever published declaration of his own evolutionism in a note to TheLoves of the Plants, the serio-comic second part of his two-poem masterwork The Botanic Garden (1791). Treating the sexual organs of flowers as amorous little human beings, Loves contains a seriously scientific note on turmeric, comparing its infertile “rudiments of stamens” to the useless “rudiments of hinder wings” in certain insects and “teats on the breasts of male animals,” all indicating their “having in a long process of time undergone changes in some parts of their bodies,” and pointing to the bold if tentatively-phrased conclusion that “Perhaps all the productions of nature are in their progress to greater perfection?” (Loves [1791] note to 1.65, pp. 7-8).[3]

When publishing Erewhon in 1872 Butler had not yet announced his conversion to Erasmus, and may still have shared the general view of him as “a forgotten minor poet”. All the same, there were longstanding friendly connections between Butler’s family and the Darwins (see Raby 10-13), and if Butler had even glanced through Erasmus’ once hugely popular Botanic Garden he might have recalled the above note from its second part, in conjunction with Charles’ later recasting of the same argument. Butler might also have remembered that its first part, The Economy of Vegetation, includes some of the first and most positive celebrations of the machine-age being ushered in by Erasmus’s Birmingham Lunar Society friends Matthew Boulton and James Watt, whose steam-pumps are brought to conscious organic life much as the plants are in Loves: “Quick moves the balanced beam, of giant-birth, / Wields his large limbs, and nodding shakes the earth” (E. Darwin, Economy 1.261-2). In Erasmus’s approving eyes, this “giant-birth” and affirmative nodding clearly foretell the earth-shaking takeover of previously human activities to which Butler more critically devotes a significant part of Erewhon. Remembering that this aspect of the novel sprang from an article wittily poised on the apparent disconnect between its two terms “Darwin” and “Machines,” it is at least relevant to recall that there had been another Darwin whose work quite explicitly lay, often and arrestingly, “among the machines”.[4]

Erewhon, then, certainly qualifies as one of the many Victorian novels partly plotted around Charles Darwin’s theories;[5] but in its playful dissolving of the supposed differences between machines, humans and plants into a single living continuum, Erasmus’s Botanic Garden may also play a part. And Butler’s knowledge of Erasmus lies more certainly behind a new chapter which he belatedly added to Erewhon in 1902. Chapter 27, “The Views of an Erewhonian Philosopher Concerning the Rights of Vegetables,” follows up a previous chapter’s vegetarian arguments “Concerning the Rights of Animals” with an argument which could have come from either Darwin about plants’ and animals’ common ancestry, leading to the deliberately absurd conclusion that human beings should eat neither. Having established the “intelligence” of plants from their skillful use of camouflage and other self-defences, Butler’s philosopher argues that this intelligence involves the plant’s memory of how to perform crucial actions—such as growing, flowering and so forth—as being derived from its successful ancestors, of which it is really a continuation rather than a separate “personality”:

if rose-seed number two is a continuation of the personality of its parent rose-bush, and if that rose-bush is a continuation of the personality of the rose-seed from which it sprang, … [e]ach stage of development brings back the recollection of the course taken in the preceding stage, and the development has been so often repeated, that all doubt—and with all doubt, all consciousness of action—is suspended.

239

There may well be an echo here of the full-blooded depictions of flower-parts as amorous little human “personalities” throughout TheLoves of the Plants, but Erasmus makes a more decisive contribution to Butler’s theory of offspring as continuations—or “elongations”—of their parents’ identities, in the following passage from Zoonomia, which Butler hails in Evolution Old and New (214) and again in Unconscious Memory (1880; 40) as one of Erasmus’s greatest breakthroughs:

Owing to the imperfection of language, the offspring is termed a new animal; but is, in truth, a branch or elongation of the parent, since a part of the embryon animal is or was a part of the parent, and, therefore, in strict language, cannot be said to be entirely new at the time of its production, and, therefore, it may retain some of the habits of the parent system.

Zoonomia 1.480

Even before he announced his conversion to Erasmus, Butler’s still-humorous psycho-physiological study Life and Habit (1877) seemed to pre-echo the above passage’s stress on inherited habits while arguing for the difference between habitually knowing how to do something and consciously knowing that we know it. For Butler, the deeper our memories go the less conscious they will be: we only become aware of our knowledge when we need to call on it in unfamiliar circumstances. This leads to the paradox that we are most “experienced” when at our youngest because our forebears have laid down many memories of their youthful experiences within us—as the above passage from Erasmus suggests—whereas when we get old there is less guidance from the past, and so we become like lost and confused children:

A living creature well supported by a mass of healthy ancestral memory is … thoroughly acquainted with its business so far. … It is the young and fair, then, who are the truly old and the truly experienced … When we say that we are getting old, we should say rather that we are getting new or young, and are suffering from inexperience, which drives us into doing things which we do not understand, and lands us, eventually, in the utter impotence of death.

Butler, Life and Habit 199

Butler was sufficiently pleased with this passage to re-quote it in his posthumous novel The Way of All Flesh (143). However, while still partially inhabiting the same world of witty paradox as Erewhon, Life and Habit inaugurates Butler’s increasingly dogged search for evolutionary theories which place unconscious wishes and needs at the heart of the evolutionary process, in firm preference to the Charles-Darwinian theory of “natural selection” which, for Butler, deliberately blocks off any attempt to ascribe animal or plant variation to anything more than accident.[6]

Evolution Old and New (1879), his first explicit enlistment of Erasmus, also credits the great French biologists Buffon and Lamarck with developing a comprehensive theory of evolution long before Charles—though the eighteenth-century Buffon had to disguise his subversive conclusions in a veil of suave French irony. While this book’s biggest star is Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, whose evolutionary Philosophie Zoologique (1809) appeared fifteen years after Zoonomia, Erasmus’s insistence on the offspring as an “elongation of the parent” retaining “some of the habits of the parent system” seems to have haunted Butler as much as he said it “plainly haunted” Erasmus himself (Evolution Old and New 202). It was this idea—not found in Buffon or Lamarck—which allowed all organisms, including plants, to transmit the “wants and endeavours” based on their own experiences to their children, leading to Butler’s grand claim in Unconscious Memory (1880) that:

I may predict with some certainty that before long we shall find the original Darwinism of Dr. Erasmus Darwin … generally accepted instead of the neo-Darwinism of to-day, and that the variations whose accumulation results in species will be recognised as due to the wants and endeavours of the living forms in which they appear, instead of being ascribed to chance, or, in other words, to unknown causes, as by Mr. Charles Darwin’s system.

Unconscious Memory 280-81

In the book just quoted and the later Luck, or Cunning? (1887), Butler increases his attack on every aspect of Charles’ work, from a stylistic evasiveness indicated in his many revisions of the precise field of agency covered by “natural” selection, to his propensity to claim the whole theory of “descent with modification” (clearly shared with his grandfather) as “my theory”. Luck, or Cunning? contains a whole chapter on “The Excised “My’s” in successive editions of The Origin of Species, drawing attention to how self-conscious Charles clearly was about the dubiousness of this usage. (Luck, or Cunning?, chapter 15, 202-10)

Another line of almost obsessive attack in these two later books relates to Charles’s allegedly duplicitous response to Butler’s own criticisms, as supposedly manifested in the sneering conclusion of Charles’s and the German biologist Ernst Krause’s joint study, Erasmus Darwin (1879).[7] Translated from its original German by W. S. Dallas and prefaced by a biographical “Preliminary Notice” by Charles, Krause’s part of this book gave high praise to the pathfinding evolutionism of Erasmus’s Zoonomia, Temple and other works. But 1879 had also seen the publication of Butler’s Evolution Old and New, declaring Erasmus’s evolutionism much superior to Charles’s, which (in Butler’s view) had prompted Krause to add a thinly-veiled rebuke at the very end of his otherwise glowing account of Erasmus’s evolutionary theory: that “to wish to revive it in the present day, as has actually been seriously attempted, shows a weakness of thought and a mental anachronism which no one can envy” (Krause 216). Butler’s conviction that Charles conspired with Krause to add this last-minute dig at himself, but then stoutly denied it, adds a new, Butlerian twist to the idea of “Darwin’s plots,” perhaps.

Applying that term more properly to the plots of novels, we have so far seen a very definite contribution by Charles Darwin to the first edition of Erewhon, along with some more speculative ones by Erasmus. However, it is fair to detect Butler’s conversion to Erasmus as a significant influence on his last, posthumous novel, The Way of All Flesh (1903, but chiefly written 1872-84). Somewhat earlier I mentioned this novel’s inclusion of a passage from Life and Habit arguing that the young are in some ways “older” and wiser than the old—a view which Butler had by now found confirmed in Erasmus’s picture of children as “elongations” and unconscious repositories of the “habits” of their parents. The partly autobiographical The Way of All Flesh charts its hero Ernest Pontifex’s journey from cowed Anglican conformism to a complete rejection of orthodox Christian teaching, and this journey is signposted by way of a number of short but telling glances at evolutionary theory—both Charles Darwin’s and the one Butler now attributed to Erasmus and Lamarck. Thus the failure of Ernest’s Cambridge theology tutors to consider atheist arguments is compared to hens’ failure to grow webbed feet “because they did not want to”—Butler’s aside that “this was before the great days of Evolution” clearly implying the then-imminent Origin of Species but adding a Lamarckian-Erasmus-Darwinian tinge in the idea of the hens’ own volition or lack of it as decisive (265). Later we hear that Ernest “read Mr Darwin’s books as fast as they came out and adopted evolution as an article of faith” (373), but more weight is given to the narrator’s musings as to whether Ernest’s many “blunders” have sprung from the

accidents which happen to a man before he is born, in the person of his ancestors, [which] will, if he remembers them at all, leave an indelible impression on him: ... To enter the Kingdom of Heaven [one] must do so, not only as a little child, but as a little embryo, or rather as a little zoosperm - and not only this, but one which has come of zoosperms which have entered the Kingdom of Heaven before him for many generations.

281-2

This passage fairly clearly implies the view of children as “elongations” of their parents’ personalities which Butler’s Unconscious Memory hails Erasmus Darwin for first propounding. In the exclusive concern with descent from the male “zoosperm,” there may also be a trace of Erasmus’s masculinist theory that the essence of the human embryo is fundamentally shaped by the father’s imagination at the moment of forming the sperm—as stated in his 1794 Zoonomia, though significantly retracted in his less-read 1801 revision—to be discussed more fully later in this essay.

This whole issue of paternal descent relates to one of the novel’s most striking structural features, by which its hero Ernest is only introduced after a long and careful tracing of his male line from his unassuming great-grandfather (whose workmanlike creativity can be seen as re-emerging in the young Ernest) through his toweringly tyrannical grandfather, to the domineeringly conventional clergyman-father from whose power and influence he spends much of the book trying to escape. In the narrator’s above musings on Ernest turning out reasonably undamaged (which is all “the Kingdom of Heaven” implies in this context), we can glimpse the idea planted in the novel’s curious structure that the escape from the father’s dominance may lie in the “impressions” donated by the “zoosperm” of the men of one or two generations before, whether he “remembers them at all” or not.

The idea of “unconscious memories” skipping generations perhaps echoes what might be called the Oedipus Complex Squared of Butler’s contempt for his own clergyman father and sense of continuing family domination by the towering figure of his dead grandfather, Bishop Samuel Butler. The latter’s careers as Headmaster of Shrewsbury School and Bishop of Lichfield happened to cross paths with the Darwin family at various points: Erasmus Darwin had once been Lichfield’s most renowned doctor, our Samuel Butler’s father was a schoolfellow of Charles Darwin’s at Shrewsbury School, and the two families remained on friendly terms until Butler began his savage attack on his erstwhile hero Charles in the works discussed above (see Raby 5-13, 163-178). Exploring these tangles, one Freudian critic argues that they involved Butler first choosing Charles as a substitute authority-figure for his own hated father and that father’s Christian God, and then switching his allegiance to Erasmus in a kind of displaced echo of Butler’s awareness that the real power and energy in his own family derived from his grandfather, the headmaster-bishop (Greenacre 93-5).

II. The Knight’s Move: from Erasmus’s Temple of Nature to Shaw’s Back to Methuselah

Bernard Shaw first came across Butler’s ideas in 1887 when, working as an ill-paid book reviewer for the Pall Mall Gazette, he was sent a copy of Luck, or Cunning? which greatly impressed him (Holroyd, vol. 3, 38).[8] By the time of his enormous five-play sequence Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (1921), Shaw had long championed Butler both in print and in a somewhat edgy friendship, and was familiar with the rest of his evolutionary works as well as at least some of Erasmus’s Zoonomia, from which his Preface enthusiastically paraphrases an evolutionary passage also quoted by Butler but with a further detail only to be found in the original.[9] A lifelong habitué of the British Museum Reading Room (Holroyd 3.501), it is very possible that as well as digging out the then-obscure Zoonomia Shaw also came across Erasmus’s other evolutionary work, The Temple of Nature, though neither he nor Butler ever seems to mention it specifically.[10]

The next part of this essay explores numerous parallels between Erasmus’s Temple and Shaw’s Methuselah which could—if useful—be taken as internal textual-biographical “evidence” of direct influence from one to the other. However, a perhaps more interesting argument revolves around the choice by these two very different writers of certain closely-related images, devices and tropes, to address the same central problem: how to translate a powerful engagement with the idea of species-evolution from the language of scientific inquiry into the language of vividly-pictured and imaginatively engaging literature. The relationship between the two texts can be thought of in terms of a theory of literary transmission which Fredric Jameson has linked to a particular set of incidents in Shaw’s Methuselah. In the second and third plays of Shaw’s sequence (The Gospel of the Brothers Barnabas and The Thing Happens), the eponymous “gospel” that we can will our own longevity is half-consciously picked up and made to “happen” by two apparently minor characters—a parlourmaid and a silly-ass young clergyman—rather than the bigwigs the brothers have been addressing. For Jameson this “extraordinary moment,” where the expected line of mental and evolutionary descent is sidestepped in favour of less predictable beneficiaries, has a parallel in the Russian Formalist critic Viktor Shklovsky’s idea of the L-shaped “knight’s move” as the characteristic shape for progress in literary history:

the knight's non-linear jump across the chessboard … awkwardly seems to rebuke, in a vaguely premonitory or Utopian fashion, the more traditionally graceful yet prosaic moves of the other pieces. … Shklovsky wanted to dramatize by this figure an idea that … had to do essentially with literary history—namely, that this last does not proceed from father to son … but rather from uncle to nephew. The development of forms and genres is thus discontinuous and teleological all at once.

Jameson 334; see too Shklovsky 3-4

Applying this idea of the development of forms and genres to the connection between Erasmus’s Temple and Shaw’s Methuselah—arguably teleological in the sense of “having to happen” at some point even if discontinuous in terms of direct influence—we can posit Butler as the bend in the “L” which connects Shaw’s evolutionary imagination back to Erasmus Darwin’s, having taken a utopian sideways leap from the “traditional yet prosaic” centrality of the more obvious route through Charles.

Before exploring some of the parallels between these two works it will be useful to give a brief outline of each of them, which will of course include an initial recognition of their many substantial differences. Versifying and greatly expanding the evolutionary arguments of Zoonomia, Erasmus’s Temple of Nature is a didactic or “philosophical” poem and so not primarily a narrative: nonetheless, a certain fictive and mythopoeic thread does run through it. After the Fall of Adam and Eve, the site of their erstwhile Garden of Eden is surrounded by rocks and threatening storms, until the poet’s “Muse” and other postulants find themselves ushered through a crystal tunnel into the grounds of a huge temple on the site of Eden, with the veiled goddess Nature at its centre (Temple 1.33-166). Much of the rest of the poem consists of the responses by a different Muse—Nature’s priestess-hierophant Urania—to the poetic Muse’s questions about the origins and nature of life.

As a note and a brief comment in the Preface indicate, the poem’s fanciful “machinery” is structured round the four stages of the ancient Greek Eleusinian Mystery rituals which—according to Erasmus’s main source William Warburton—supposedly transported their initiates from the recognition of death to the celebration of sexual reproduction, then to the appearance of light-bringing torches symbolizing mental enlightenment, and finally to the assertion that certain heroes have gained the godlike “immortality” of fame (Temple Preface and note to 1.137).[11] As loosely mapped onto this supposedly Eleusinian structure, Temple’s four cantos—“Production of Life,” “Reproduction of Life,” “Progress of the Mind” and “Of Good and Evil”—describe how “Organic life began beneath the waves” of a hitherto dead world (1.234) before expanding onto land; how asexual parthenogenesis in both plants and animals was greatly improved on by the joyful emergence of sex; how various environmental adaptations led to the growth of mental and social abilities in animals and humans; and finally the human achievements and other reasons for affirming that—however dark in its proto-Charles Darwinian recognition that “One great Slaughter-house the warring world!” (4.66)—this new evolutionary vision of Nature ought not to lead us to pessimism.

As Shaw’s magniloquent Preface makes clear, his utopian dramatic sequence Back to Methuselah is centred round the idea of “Creative Evolution”: the possibility of species-transformation through efforts of will, whether conscious or unconscious. Proclaiming Creative Evolution as “the religion of the next epoch,” the Preface attributes its growth largely to Schopenhauer—whose The World as Will offered “the metaphysical complement to Lamarck’s natural history”—and to Shaw’s particular hero Nietzsche, who understood the Will to Power as primarily “power over self” (Methuselah xxx, liii).[12] Thus philosophically bolstered, the Preface invokes Lamarck, Butler and Erasmus’s Zoonomia as key sources for the idea that animals can transmit desirable traits to their offspring by an effort of volition (xx-xxi, xlv-xlvi), and Methuselah as a whole extends this to humans, dramatizing the idea that only by deciding to live longer with unimpaired minds will people ever become wise enough to avert catastrophes like the senseless slaughter of the First World War (x, xvii).

First, as we learn at the end of Methuselah (264), the primeval pre-sexual figure of Lilith wills herself to split into male and female; then in the first play, called In the Beginning, Adam and Eve overcome their new fears of mortality on finding a dead fawn by deliberately (rather than instinctively) taking up sex to produce children. In the next play, set in Shaw’s early twentieth-century present, The Gospel of the Brothers Barnabas begins to persuade people that they can will themselves to live for at least three hundred years. In the next play, set a hundred and fifty years later in 2170, The Thing Happens—or in fact turns out to have already happened—in that two apparently minor characters from the previous play have taken the Barnabas’ gospel to heart and continued to live in complete health, having adopted various subterfuges to conceal their longevity. By the fourth—Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman, set in 3000—the long-lived inhabit a separate community in Ireland, taking various measures to protect visitors with ordinary lifespans from the shock of fully realizing their inferiority.

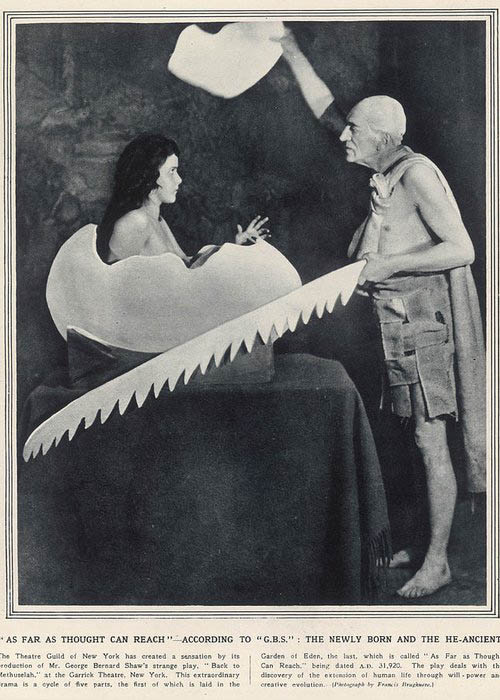

In the final play, As Far as Thought Can Reach, longevity is so completely the norm that the healthy young folk we see engaged in various love-affairs and cultural pursuits are only counted as children. The pain of childbirth having been removed by their incubation in eggs (from which they emerge as already adolescent, as shown in the photo below from the first stage production in New York, 1922), these youngsters are allowed to enjoy themselves but will eventually grow into the “ancients” we also meet, whose mental enlightenment is so great that they plan to discard their bodies and live on in a realm of pure mind.

Like Erasmus Darwin’s Temple, then, Shaw’s Methuselah is about defeating the fear of death in a universe devoid of standard Christian notions of the afterlife. To achieve this reassurance, both texts appeal to remarkably similar mythopoeic structures. Thus both map contemporary evolutionism onto the ancient origin-myth of Adam and Eve, and subversively rewrite the latter as part of the progress towards better things rather than the reverse. As a key alternative source of cultural authority to the Bible’s creation myth, both also appeal to the classical idea of the oracular temple, and perhaps Shaw’s structure also appeals to at least the first three stages of Erasmus’s classical Eleusinian “machinery” in its transition from the awareness of death to the successive rebirths of sexual reproduction and mental enlightenment, with a rather looser parallel between Shaw’s final utopia and the various “reasons to be cheerful” of Erasmus’s fourth and last Eleusinian stage.

As regards Adam and Eve in more detail: Erasmus’s Temple repeatedly visits the story of the Garden of Eden in a series of playful jabs designed to throw doubt on its literal truth. First we see Adam cheerfully “bartering life for love” by taking the sexily-offered “sweet fruit” from Eve (1.33-46); then we revisit the story of Eve’s birth from Adam’s rib as an Egyptian allegory of the evolutionary leap from asexual to sexual reproduction (2.117-20, 135-58) before joining the poet’s Muse to enjoy a “no longer interdicted” fruit-picnic beneath the still-flourishing Tree of Knowledge (2.435-46); finally, on the less positive side, it is hinted that the true Fall into the knowledge of evil and death arose from the killing of animals, and guilt at their “blood by Hunger spilt” (3.449-60).

In what feels like an echo of this last thought, Shaw’s Back to Methuselah begins with Adam’s and Eve’s discovery of a dead fawn: by proving that death is possible, this leads to a slow unravelling of all their innocent assumptions, culminating in Eve’s rather disgusted learning of the facts of sex from the serpent, and the concomitant “fall” of her and Adam’s idealistic awareness of immortality once they realize they can have offspring—including the murderous Cain—to replace them (Methuselah 1-2, 17-19). At the very end of the play-series they reappear along with their pre-sexual ur-parent Lilith, who describes how “I tore myself asunder … to make of my one flesh these twain, man and woman” (264), much as Erasmus’s dreaming Adam “formed a new sex, the Mother of Mankind,” in what is clearly explained as an allegory for the crucial evolutionary moment when “sex from sex the nascent world divides” (2.140, 120).

In Temple, the site where Erasmus’s truth-seekers learn about this and other matters is the imposing eponymous Temple of Nature itself, presided over by the Goddess of Nature whose “mystic veil” is at last removed “with trembling awe” in the poem’s closing lines (4.517-24). In Methuselah, one crucial scene (Act 2 in the fourth play, Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman) is set “before the columned portico of a temple,” presided over by an oracular “veiled and robed woman of majestic carriage,” who when she “throws back her veil” causes one short-living postulant to “shriek, stagger, and cover his eyes” (Methuselah 178, 180). Later, other postulants are threatened by “Terrific lightning and thunder” (201), rather as Erasmus’s temple is shielded from “the profane” by “eternal tempest” and “livid lightnings” (Temple 1.49-50). It may or may not be relevant that the role of the veiled figure’s hierophant-priestess—called Urania in Temple—is taken in Methuselah by a long-liver called “Zoo,” whose curious name is dwelt on at some length with no suggestion of animal-displaying zoological gardens being involved (Methuselah 153). Perhaps the name simply implies “zoon,” or “animal organism,” but it is tempting to see it as a more specific nod to Erasmus’s evolutionary Zoonomia, just as Zoo’s flippant self-mockery of her own hierophantic role (189) could possibly testify to Shaw’s wry acknowledgment that his temple’s awe-inspiring machinery seems to be largely borrowed from Erasmus’s Temple of Nature (whose off-putting thunders are rather similarly evaded by a bevy of “tittering” initiates (Temple 1.61)).[13] However this may be, in both texts this elaborate set-dressing is chiefly designed to stress the challenge and difficulty of grasping the evolutionary instruction being conveyed.

To reinforce the possibility of direct textual influence, it is worth noting that a reader flicking rapidly through Erasmus Darwin’s Temple in pursuit of further support for the ideas of Zoonomia could have found most of the imaginative tropes I have been picking out in its first few pages. We encounter Adam and Eve, the thunder-guarded temple, the veiled goddess and the key note on the structure of the Eleusinian Mysteries all in the first thirteen pages (lines 1-137); and although the focus on sexual differentiation only appears in Canto Two, our putative rapid flick might also quickly light on the second of the poem’s four full-page illustrations by Henry Fuseli, showing “The Creation of Eve” from the sleeping Adam’s rib (opposite p. 55), and clearly keyed to Erasmus’s subversive note describing this Biblical myth as an Egyptian allegory for the switch from non-sexual to sexual reproduction (Additional Notes p. 42).

Thus, it is perfectly possible that Shaw encountered the relevant parts of Erasmus’s Temple—say in the British Museum Library—when researching Butler, Lamarck and Erasmus’s own Zoonomia as background to the theories of Methuselah; but if so, he did not say so. If not, something like Shklovsky’s “knight’s move” might be argued to provide the connection between them: at once “discontinuous and teleological,” if we take the discontinuity as read and the telos as determined by the felt need for an epically ambitious piece of imaginative literature relating evolutionary theory to humankind. With this aim some reasonably natural moves might well involve starting with the Eden myth only to slyly subvert it, offering powerful alternatives to scriptural authority via the familiar gravitas of the oracular classical temple, removing truth-concealing veils, and so forth. Nonetheless, if these shared elements do not after all tell us anything about direct influence, they do tell us something about the formation of new genres or subgenres under the pressure of changing circumstances, as with the Shklovskyan transmission of literary forms not “from father to son … but rather from uncle to nephew,” of which Jameson is reminded by the curious sideways transmission of the gospel of willed longevity in Methuselah’s second and third plays (Jameson 334).

III. Plotting a course: Erasmus’s evolutionism and will-power

Questions of direct or indirect influence between literary plots and images take us only so far. More important than such matters of transmission are the comparisons these texts open up between the ways authors in different periods make use of evolutionary theory to plot a course through the social and political issues their fictions also confront. In the remaining part of this essay, I shall try to pull together some broader points about the scientific and social theories underlying the works being discussed, and then connect these to the varied—but in some ways comparable—social and political contexts from which they arose.

First, given both Shaw’s and Butler’s enlistment of Erasmus as a proto-Lamarckian, it is worth considering how far he really did hang his hat on a Lamarck-like theory of the will of individual organisms towards improvement, in preference to his grandson’s identification of random “natural selection” of better-adapted mutations as the chief mechanism of evolutionary change. As Butler himself notes, Erasmus’s treatment of sexual selection through the growth of male attributes such as antlers almost exactly anticipates Charles,[14] and his account of the world as a necessary “slaughterhouse” of excess species-populations (Temple 4.66) echoes his contemporary Thomas Malthus, whose Essay on Population (1798) Charles described as foundational to his own theory of Natural Selection.[15]

However, at other times Erasmus suggests somewhat loosely that organisms have willed their own transformations because of some perceived need, as in the formulation: “The three great objects of desire, which changed the forms of many animals by their exertions to gratify them, are those of lust, hunger and security” (Zoonomia 1.506). Perhaps as much a manner of speaking as an essential plank of his theory, this idea of organisms actively “exerting” themselves towards their own transformations is one of the things Butler and Shaw would pick on enthusiastically, as a stick to beat Charles with.[16]

And there is one specific aspect of Erasmus’s thought where will and desire do seem to be more definite factors. This is reproduction, where the male “imagination” at the moment of sexual conception is held to shape key aspects of the foetus. Not fully integrated with the rest of his theory, this idea is spelled out thus in Zoonomia, Part One (1794):

I conclude, that the imagination of the male at the time of copulation, or at the time of the secretion of the semen, may … cause the production of similarity of form and of features, with the distinction of sex; as the motions of the chissel of the turner imitate or correspond with those of the ideas of the artist.

519

Though Darwin explicitly retracted it in Zoonomia’s 1801 third edition, which gives equal weight to both sexes’ contributions (2.277-97), an ambiguous trace of this idea lingers on in a passage we have already glanced at in the 1803 Temple, in which the birth of Eve from Adam’s rib through “Imagination’s Power” is held up as an intentional allegory for the willed transition from asexual to sexual reproduction in a range of early species, whereby:

2.117-20The potent wish in the productive hour

Calls to its aid Imagination’s power,

O'er embryon throngs with mystic charm presides,

And sex from sex the nascent world divides.

We have already seen how Butler speculates on the way paternal and grandpaternal “impressions” may be similarly transmitted through their “zoosperms” in The Way of All Flesh, but Erasmus’s view of the transformative power of imagination may also feed into Shaw’s vision of the power of will over matter.

And Temple does contains one further hint towards Shaw’s more specific conviction that we can “will” ourselves into longevity, if not immortality. A lament over the brevity of life at the start of Canto 2 leads to a footnote which in turn leads to one of Darwin’s lengthy “Additional Notes” at the back of the book. Titled “Old Age and Death,” this note repeats much of Zoonomia’s analysis of these phenomena from a medical viewpoint but adds the further comment that, while “the approach of age” results from “the inexcitability of the fibres, or the diminution of the production of sensorial power,”

there is one kind of stimulus, which … seems to increase the production of sensorial power beyond the expenditure of it … and thence to give permanent strength and energy to the system; I mean that of volition… [M]any who have exerted much voluntary effort during their whole lives, have continued active to great age. This [arises principally from] exciting and comparing ideas.

Temple, Additional Notes 7, 29-30

Though violent physical exertion simply “forwards old age” by exhausting the body—which explains the short lives of the poor—such vigorous mental activity actually has the ability to fend it off through the power of will or “volition”.

While this isolated observation is presented as simple physiological fact, a further subtext can be read from the strongly political company it keeps in its late-eighteenth- / early-nineteenth-century context. Even before he wrote it his satirical enemies George Canning, George Ellis and John Hookham Frere of the reactionary Anti-Jacobin magazine had accused Erasmus of taking the idea much further, tying it both to evolutionism and French-Revolutionary hostility to monarchy and religion, by making “him” state in a footnote to their Darwin-parody “The Loves of the Triangles”:

if, as is demonstrable, we have risen from a level with the Cabbages of the field ... by the mere exertion of our own energies, we should, if these energies were not repressed and subdued by the operation of prejudice and folly, by KING-CRAFT and PRIEST-CRAFT ..., continue to exert and expand ourselves ... to a rank in which [Man] would be, as it were, all MIND; would enjoy unclouded perspicacity and perpetual vitality; feed on Oxygene, and never die, but by his own consent.

Canning et al., Anti-Jacobin 2.164-5

Such doctrines had been more seriously voiced in this period by avowed political radicals such as William Godwin (another butt of “Triangles”), the first edition of whose An Inquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) asked “why may man not be one day immortal?” on the basis of a remark by Erasmus’s friend and fellow-freethinker Benjamin Franklin that “mind will one day become omnipotent over matter” (Godwin 2.862).[17] A little later, in “A Hymn to Intellectual Beauty” (1816), Godwin’s radically atheist disciple Percy Shelley declares that:

Shelley 526-8, lines 39–41Man were immortal, and omnipotent,

Didst thou [Intellectual Beauty], unknown and awful as thou art,

Keep with thy glorious train firm state within his heart.

A century later, Shaw proclaims his own radical “eighteenth-centuryism” and “Shelleyism,” approvingly echoing Shelley’s denunciation of the orthodox Christian God as an “Almighty Fiend” (Methuselah Preface lxxxvi, liv, xli-xlii),[18] and constructs his entire “Metabiological Pentateuch” round the idea that at some point human will-power will drive us towards an intelligent longevity that will free us from the political stupidities imposed by our current short lives:

We shall go to smash within the lifetime of men now living unless we recognize that we must live longer … We can put it into people’s heads that there is nothing to prevent its happening but their own will to die before their work is done.

Methuselah Part Two: The Gospel of the Brothers Barnabas 73, 84

Hence, even if not directly echoing Erasmus himself, there is certainly an echo of his freethinking radical milieu in Methuselah’s postulation of willed longevity as the next evolutionary leap. Without pinning his own colours completely to the immortalist mast, Erasmus Darwin added some physicianly weight to this discourse and may have implicitly connected it to evolutionary theory through its positioning in Temple.

IV. Plotting the Future: Science Fiction and Utopia

Fredric Jameson titles his chapter on Shaw’s Methuselah “Longevity as Class-Struggle” (328-44) and indeed, in an already densely populated world and with great advances in life-prolonging medical research now bidding fair to replace Shaw’s evolutionary willpower, the question of who should have access to the benefits of such research could soon put other issues of wealth and status completely in the shade. In Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, Yuval Noah Harari suggests that the race is now on for “The Last Days of Death” in which twenty-first century humans “are likely to make a serious bid for immortality” (Harari 24-34). While doubting that this is completely realizable medically, Harari links this aspiration with a future scenario in which Artificial Intelligence renders human abilities redundant and/or human agency and consciousness are transferred to computers, or the cloud, in the kind of cyber-immortality described by Ray Kurzweil as “the Singularity” (49-52, 444-51). When considering such a “post-human” future it is perhaps also relevant to bring in Erewhon’s vision of human/machine crossovers, of which Kenneth M. Roemer argues that “Butler’s satire of anti- and pro-technological development represents one of the most sophisticated and perceptive foreshadowings of the twentieth-first century “post-human” dilemma” (Roemer 90). In Harari’s (or anyone’s) “Tomorrow,” then, Butler’s vision of takeover by machines could well join forces with Shaw’s vision of takeover by long-livers, to cataclysmic effect.

While Erewhon’s complex Swiftian mingling of utopian and dystopian elements is often noted (Kumar 106-8), Shaw’s Methuselah can be considered as a more straightforward work of utopian science fiction. For Tom Shippey, “a case can be made for [it] as a compendium of future science fiction plots and developments,” while for Jameson, “there are genuinely science-fictional pleasures coursing through” it, pleasures flowing on into such sci-fi works as Robert Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children (1941/1958) which borrows its name and central idea from Shaw, including that of long-livers having to escape detection by faking their own deaths (Shippey 206, Jameson 328).

Of the various sci-fi modes it explores, Methuselah certainly concludes as a utopia.[19] Set in 31,920 AD its fifth and last play, As Far as Thought Can Reach, presents a classical-pastoral setting where healthy young folk of both sexes dance, chatter and conduct guilt-free love affairs under the benign eye of two still-healthy ancients who have long passed beyond such things. Then a young scientist called Pygmalion displays his latest invention: a pair of apparently perfect humanoid automata who/which unfortunately respond to stimuli in a completely self-centred way, finally killing their creator. Indicating that these cyborg throwbacks to Charles-Darwinian “survival of the fittest” are an evolutionary dead end, the ancients serenely dispose of them and then depart, looking forward to a time when they can become pure minds, and “there will be no people, only thought” (Methuselah 257).

Erasmus Darwin has also been hailed as a founding father of science fiction.[20] One of Temple’s notes helped to inspire Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein[21] - which may in turn have inspired Shaw’s murderous androids—and his earlier poem The Economy of Vegetation contains previsions of steam-trains, aeroplanes, submarines and climate-control through the redirection of winds and icebergs. (Darwin, Economy 1.289-96, 4.195-200, 4.336-50, 1.529-46).[22] These prophecies are technological rather than political in any clear way, but Temple’s opening invocation to the Muse does drop a hint that it was at one point planned as a “pentateuch” of five cantos, (in contrast to Darwin’s usual four) prophesying a future fifth age: “Four past eventful Ages then recite, / And give the fifth, new-born of Time, to light” (Temple 1.9-10). These lines are borne out nowhere in the extant poem, but gesture fleetingly at a different projected poem on socio-technological developments to be called “The Progress of Society,” which Darwin had abandoned in favour of the extant Temple. His drafts (which Shaw could not possibly have known about) for the future fifth “Age of Philosophy” convey a strongly utopian yearning for a world which has at last outgrown war, hatred and inequality, not unlike the vision of life in Methuselah’s fifth play:

Canto V. Age of Philosophy … Liberty. No crime…. Ruins of superstition long remain. Philosophy. Science. Peace. Elements subdued. Swords turned to ploughshares. Every man under his fig tree. Moral world. Love each other. “Do as you would be done by”.

Priestman 282[23]

V. Evolution and Politics

Both these writers’ yearnings for such utopias can be linked to the political atmospheres in which they were writing. Both Temple and Methuselah were written in the shadow of war—which these authors opposed—and overseas revolution, which they supported. Darwin was notorious for welcoming both the American and French Revolutions of 1776 and 1789; Shaw for supporting the Russian Revolution of 1917; but for both, the massive wars closely coinciding with these revolutions were disasters. By 1801, when Darwin seems to have been rounding off Temple, the long Anglo-French/Napoleonic War was enjoying a very temporary lull in the Peace of Amiens, on which Darwin seizes with a denunciation of the “fell demoniac rage” of “wide-wasting war,” combined with a plea to the progressive “patriot heroes” of Parliament not only to uphold this short-lived “fostering peace” (4.273, 280, 285) but also to reverse the blinkered police-state suppression of free expression in the war-years:

4. 283-6Oh save, oh save, in this eventful hour

The tree of knowledge from the axe of power;

With fostering peace the suffering nations bless,

And guard the freedom of the immortal Press!

For Shaw, the First World War and its revanchist aftermath in the Treaty of Versailles had produced “a European catastrophe of a magnitude so appalling, and a scope so unpredictable, that as I write these lines in 1920, it is still far from certain whether our civilization will survive it” (Methuselah x). In this context, for him, the Russian Revolution was only a sensible withdrawal from the collective insanity:

Meanwhile Russia, reduced to a scrap of fish and a pint of cabbage soup a day, has fallen into the hands of rulers who perceive that Materialist Communism is at all events more effective than Materialist Nihilism, and are attempting to move in an intelligent and ordered manner, [seeing] workers as fitter to survive than idlers.

Methuselah lxx

Temple contains no direct praise of the French Revolution which had precipitated the Anglo-French War but in 1790 Darwin had described himself to James Watt as feeling “all french, both in chemistry and politics” (E. Darwin, Letters 200) and his vocal support for the Revolution in the 1791 Botanic Garden and in Derby local politics had brought him close to prosecution for treason (Economy 3.377-94; King-Hele 276-7). As I have argued elsewhere, it was probably from fear of similarly hostile responses—as in the passage from Canning, Ellis and Frere’s “Loves of the Triangles” quoted above—that he dropped his projected socio-political Progress of Society in favour of the more purely evolutionist Temple.[24] Nonetheless, his subtitle for the latter, The Origin of Society, retains half of that earlier title and—in a context of recent war abroad and suppression of thought at home—its opening invocation pleads for a new understanding of the primacy of the social impulse once the facts of our gradual evolution from simpler life-forms are fully grasped:

Temple 1.3-8Say, MUSE! how rose from elemental strife

Organic forms, and kindled into life;

How Love and Sympathy with potent charm

Warm the cold heart, the lifted hand disarm;

Allure with pleasures, and alarm with pains,

And bind Society in golden chains.

Whereas Shaw makes an evolutionary human species-shift the only possible escape from disasters like the First World War, Erasmus’s Temple holds out the simpler hope that a truer scientific understanding will free us from the delusions of religious superstition, and that a strengthening of our evolved capacity for “Love and Sympathy” will disarm “the lifted hand” of war.

Embracing similar (if not identical) theories of evolution and confronted by distinctly parallel historical circumstances, then, both Erasmus and Shaw formed imaginative fictions which use the first to plot a course through the second. And if both Erasmus and Shaw produced their evolutionary epics out of a strong awareness of immediate political crisis, Samuel Butler’s strange and rather disturbing novels can also be described as responses to crisis, albeit of a more protracted kind. To an extent, it is Charles Darwin’s Origin itself, with its blow to orthodox Christian creationism, that dominates Butler’s career from beginning to end, prompting complex reactions from playful embrace to angry rejection; and, tongue-in-cheek though his treatment of machines may be, it reflects many Victorians’ sense of the unstoppable growth of industrial mechanization as another massive trauma, albeit in protracted slow-motion.

To return to Erewhon with these points in mind: apart from its hero’s realistically-described discovery of this isolated utopia/dystopia at the beginning and his escape in an air-balloon at the end, its only real “plots” are the various convoluted mental journeys we as readers are made to undertake, from the country’s various mad beliefs—particularly in crime as a sickness and sickness as a crime in Chapters 10 to 12—back to the aspects of Victorian English life they are implicitly commenting on. Here there is a mixture of “progressive” and reactionary elements: if the medicalization of criminality looks forward to more enlightened uses of psychology, the criminalization of sickness and other kinds of misfortune seems to point to a prospect in which “survival of the fittest” might one day move from being a dimly-glimpsed Darwinian law of nature to an acknowledged law of respectable society. However amusingly presented, some of its descriptions of the harsh penalties meted out for disease and accidental misfortune (e.g. Erewhon 121-2) prefigure scenes from Kafka’s The Trial, or perhaps even twentieth-century extermination camps.

If we connect this point to Erewhon’s section on machines we can see that, for Butler as well as Shaw and Erasmus Darwin, something in the time is out of joint and some serious new thinking about evolution is needed to set it right. For Butler specifically, the natural evolution towards “Love and Sympathy” described in Temple’s invocation is by no means inevitable given “the whole movement in favour of mechanism” which he has had in his sights from his early squib on “Darwin Among the Machines” onwards. What he emphatically calls “the Neo-Darwinistic doctrine of natural selection, which … involves an essentially mechanical mindless conception of the universe,” eventually leads Butler to the conclusion that “to natural selection’s door, therefore, the blame of the whole movement in favour of mechanism must be justly laid” (Luck, or Cunning? 139-40).[25]

VI. Neo-Darwinism and Social Darwinism

Butler’s repeated use of the term “Neo-Darwinism” is strategic, implying that Charles is not actually the “real” Darwin, just a belated perverter of his grandfather’s more accurate teachings. Shaw takes over the same term, but adds the further nuance that Charles’s own plodding insights are not wholly to blame for their erection into a social world-view by his “Neo-Darwinist” followers. However, be that as it may:

At the present moment one half of Europe, having knocked the other half down, is trying to kick it to death, and may succeed: a procedure which is, logically, sound Neo-Darwinism.

Methuselah x-xi

For Shaw, this kind of dog-eat-dog nationalism joins dog-eat-dog capitalism as Neo-Darwinism’s logical outcome. (Though he sees Marxist communism as also infected by it, he finds its selection of the proletariat as “fittest” for survival less problematic than capitalism’s preference for the already empowered [lix-lx].)

Shaw’s and Butler’s critiques of a sinisterly pervasive “Neo-Darwinism” seem well-applicable to the tendency more recently labelled “Social Darwinism”. As with many “isms” this is a largely retrospective term, used more by later critics than actual espousers.[26] Nonetheless, it reasonably accurately pinpoints a long and widespread eugenicist attempt to apply Charles-Darwinian “survival of the fittest” (though the phrase is Herbert Spencer’s) to human social issues. The idea is often particularly applied to race, as if the very small biological differences between human ethnic groups in some way “unfits” some of them in a zero-sum sprint for racial supremacy in which there can only be one victor.[27]

To tackle this last aspect of Social Darwinism very quickly: none of our three writers take their evolutionism in the racist directions favoured by some of their contemporaries. Virtually Erasmus Darwin’s only statements on race involve angry attacks on the enslavement of our “brother” Africans, as contrasted for example to his proto-evolutionist contemporary Richard Payne Knight, who in 1796 trumpeted the fair-skinned Aryan race’s superiority as being “farthest removed from [...] the Negro,” whose “sable hue and bloated face” announces Africans’ close kinship to “their parent race,” the ape.[28] In Butler’s Erewhon, it is true that the hero Higgs impresses the darker-skinned Erewhonians with his fair hair and blue eyes (37), but none of the values expressed in this book can be taken straightforwardly and—however topsy-turvy their belief-systems—most Erewhonians we meet are dauntingly intelligent. (At the very end of the book (255-60), Higgs’s unpleasant plan to conquer and export them all to Australia as indentured quasi-slave-labour is a transparent critique of such imperialist projects, not a condonement.)[29] Shaw was a fierce internationalist, seeing the League of Nations as essential to the world’s survival and, in Methuselah specifically, including a future scenario where the British Prime Minister is only the figurehead for a government managed by Chinese and Africans because, as one of them explains, “government is an art of which you are congenitally incapable. Accordingly, you imported educated negresses and Chinese to govern you. Since then you have done very well” (100).

However, if Erewhon and Methuselah are programmatically non-racist, they do raise the issue of some groups, or types, being regarded as less fit for survival than others. As we have briefly seen, the Erewhonians’ treatment of the sick can be seen as a distorted socialization of “survival of the fittest” doctrine, in a way that Butler certainly does not condone but nonetheless seems to be “putting out there” as a present or future possibility. And when the hero of The Way of All Flesh finally brings all the conflicting social and evolutionary ideas he has wrestled with together in the form of a book, the only undoubted positive he can come up with is the importance of “good breeding” (404), an implicitly eugenicist concept which fuses the ideas of managed biological inheritance and social advantage together within a single overarching term.

Much more definitely, a Social-Darwinist distinction between social types or groups is a significant theme in Shaw’s Methuselah, particularly in Part 4, Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman. Here we learn that the long-livers—now currently all resident in Ireland—have two political parties: the Conservatives and Colonizers or “Exterminators” (172, 175). While the former are content to remain in Ireland, carefully restricting their brief contacts with visiting short-livers, the Colonizers believe there is no point in postponing their inevitable takeover of the rest of the world, most of whose inhabitants will in any case die of “the deadly disease called discouragement” (143) on looking their superior wisdom in the face—a fate to which we see the Elderly Gentleman voluntarily submitting at the climax of the play (175).

While Shaw leaves the non-Exterminationist party just in the ascendant in this 1921 piece, its picture of a half-voluntary euthanasia of redundant specimens plays unpleasantly against a Newsreel made ten years later in which an avuncular-looking Shaw calls for the extermination of undesirable social elements such as the mentally weak, habitually criminal, or simply idle, who must be genially informed that

if you do not produce as much as you consume, or perhaps a little more, then, clearly, we cannot use the organizations of our society for the purpose of keeping you alive, because your life does not benefit us and it can’t be of very much use to yourself.[30]

By 1934—eight years before the Nazis’ first use of Zyklon B in Auschwitz—Shaw had thought of the ideal solution: “I appeal to the chemists to discover a humane gas that will kill instantly and painlessly. In short—a gentlemanly gas deadly by all means, but humane, not cruel” (The Listener. London: February 7, 1934). Despite his disagreements with Hitler over race, Shaw’s embrace of the horrific tactics of Hitler as well as Stalin throughout the 1930s largely justifies George Orwell’s baffled remark that he “declared Communism and Fascism to be much the same thing, and was in favour of both” (Orwell 208).[31]

To put it at its mildest, then, Shaw’s—and to some extent Butler’s—uses of evolution to plot a course through the heart of what they see as society’s worst problems are themselves problematic; but Erasmus Darwin’s two separate “Progress” plots largely avoid connecting the two themes. The main moment where he does suggest such a connection is in an apparent echo of his contemporary Thomas Malthus’ bleak picture of the human struggle for resources depending on mass deaths:

Temple 4.369-74[32]“So human progenies, if unrestrain’d,

By climate friended, and by food sustain’d,

O’er seas and soils, prolific hordes! would spread

Erelong, and deluge their terraqueous bed;

But war, and pestilence, disease, and dearth,

Sweep the superfluous myriads from the earth.

However, whereas Malthus used such calculations as reasons for resisting most attempts to alleviate the conditions of the poor, Erasmus actively supported reformist campaigns against war, slavery, poverty and disease (Malthus 71-100; King-Hele 153, 199, 231-2). Indeed, Temple’s whole fourth canto is an attempt to overcome the Muses’ grief over their awareness that “From Hunger's arm the shafts of Death are hurl'd, / And one great Slaughter-house the warring world!” (4.63-6) Although Charles Darwin praised a similar passage in Erasmus’s Phytologia as “forecasting the progress of modern thought” (C. Darwin, “Preliminary Notice” in Krause 113), the pinpointing of particular types or individuals who in some sense “deserve” this slaughter is no part of either Darwin’s broad evolutionary argument.

One further aspect of Shaw’s open, and Butler’s more implicit, eugenicism is their distrust of sex.[33] For Shaw this is an inherently disgusting act which Eve only adopts “with overwhelming repugnance” in order to perpetuate her lineage (Methuselah 17), and from whose “prehistoric” mechanics the egg-born if flirtatious youths and maidens of 31,920 AD will be spared (237), while the hero of Butler’s The Way of All Flesh sees “the family system” as “incompatible with high development” (103), and in Erewhon sex is viewed as a bizarre mechanism by which unborn children plague and torment their future parents, “giving them no peace either of mind or body” until they consent to produce them (Chapter 18). This self-chastizing element in Butler’s and Shaw’s views of sex can be connected to their “Lamarckian” sense that we ought to be able to will our ideal successors into existence rather than simply succumbing to nature’s promptings in the matter.

By contrast, Erasmus’s Temple does not advocate any particular “evolutionary” path for humanity beyond the general expansion of thought and knowledge, avoidance of war, abolition of cruelties such as slavery, and full enjoyment of natural and social pleasure—of which sex is what he once called the “chef d’oeuvre” (E. Darwin, Phytologia 103). In his celebration of the hundred-breasted Goddess Nature’s multiplicity and abundance he comes much closer to his grandson’s climactic vision of nature as a richly “entangled bank” of co-existing differences than to the more self-narrowing and self-punishing visions of his two belated champions (Temple 1.132; C. Darwin, Origin 489).

Appendices

Biographical note

Martin Priestman is an Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Roehampton, London. He is the author of The Poetry of Erasmus Darwin: Enlightened Spaces, Romantic Times (2013), Romantic Atheism: Poetry and Freethought, 1780-1830 (1999), Cowper’s Task: Structure and Influence (1983) and a number of articles and chapters on Enlightenment and Romantic literature. He has edited The Collected Writings of Erasmus Darwin (2004) and an online edition of Darwin’s The Temple of Nature (Romantic Circles, 2006). He has also published widely on Crime Fiction and edited The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction (2003).

Notes

-

[1]

For some reasons for this collapse, see King-Hele 314-20.

-

[2]

Butler’s main objection to this section (39, “Of Generation”) is that it is too brief and should have been followed up with further work, which suggests that he had not then come across The Temple of Nature where such further work is undertaken.

-

[3]

To be strictly accurate a much shorter version of this evolutionary note had already appeared in the first, 1789 edition of Loves (1.67-8). It is also worth noting that Loves contains a lengthy bravura description of the first balloon-flight by the Montgolfier brothers, and Erewhon ends with a dramatic escape by its hero Higgs in an air-ballooon (Loves [1791] 2.25-66; Erewhon 247-52).

-

[4]

See Dyson, 15-34, for a useful discussion of many of the connections raised here between Butler, evolution, machines, both Darwins and Erasmus’s Lunar Society friends.

-

[5]

In her Preface to the Second Edition of Darwin’s Plots (1999) Gillian Beer acknowledges Butler’s relevance to her arguments, despite having been unable to give him the attention he “deserves …in this book” (xx).

-

[6]

With its emphasis on unconscious motivation, Life and Habit’s chapter 7 on “Our Subordinate Personalities” seems for a moment to anticipate Freud in its picture of an unstable “ego” at the mercy of other aspects of the self: “we are irresistibly impelled to act in such or such a manner; and yet we are as wholly unconscious of any impulse outside of our own “ego” as though [these other aspects] were part of ourselves” (106). However, rather than the id or superego, these other elements are microscopic self-directing units within our bodies, ranging from parasites to integral parts of our bodily functions such as the blood corpuscles which determine our patterns of breathing: “We breathe that they may breathe, not that we may do so; we only care about oxygen in so far as the infinitely small beings which course up and down in our veins care about it” (107). In something like a fusion between Richard Dawkins’ “selfish genes” and the Freudian unconscious, our “personality” thus consists of a tension between our conscious ego and the various id-like sets of instructions parentally inscribed within us.

-

[7]

For good accounts of this controversy see Raby 170-77, Amigoni 145-7, and Gillott 55-61; for a book-length Freudian account, see Greenacre.

-

[8]

Shaw’s review of Butler’s Luck, or Cunning?, called “Darwin Denounced” (31 May, 1887), can be found in Bernard Shaw’s Book Reviews, 277-9.

-

[9]

The further detail from Zoonomia is that “the brilliant colours of the leopard, which make it so conspicuous in Regent’s Park, conceal it in a tropical jungle” (Methuselah xx).

-

[10]

However, Butler must have been well aware of Temple’s evolutionism by the time he wrote Unconscious Memory (1880), since part of that book centres round his obsessively close reading of Krause’s Erasmus Darwin, which quotes Temple’s evolutionary passages at length.

-

[11]

See Warburton, Works 1.168-9.

-

[12]

However, elsewhere Shaw did acknowledge the actual source of “Creative Evolution” in Henri Bergson’s L’Évolution Créatrice (1907); see Holroyd 3.201. Nietzsche’s idea of the Will to Power as power of the self is the driving inspiration of Shaw’s Man and Superman (1903).

-

[13]

One more hint that Zoo embodies Erasmus-Darwinian wisdom lies in her giggling incomprehension of the Gentleman’s metaphor-laden use of language. Her critique of “the slavery of the shortlived to images and metaphors” (Methuselah 169) arguably echoes the very last sentence of Temple’s Additional Notes, where Darwin pleads for a future use of language “which as science improves and becomes more generally diffused, will gradually become more distinct and accurate than the ancient ones; as metaphors will cease to be necessary in conversation, and only be used as the ornaments of poetry” (Temple, Additional Notes p. 120).

-

[14]

Erasmus’s anticipation of Charles and advance on Buffon and Lamarck in establishing the importance of sexual selection, as shown by the growth of otherwise useless male features such as tusks or antlers, is noted both by Butler (Evolution Old and New, 282), and Charles’s co-natural selectionist Alfred Russell Wallace (141).

-

[15]

C. Darwin, Life and Letters, vol. 1.83.

-

[16]

James Harrison argues that Erasmus “had in his grasp … the constituent parts of the full theory of … natural selection” despite “some Lamarckian mechanisms” (260-261); for George Dyson, both Butler’s and Charles’s identification of “Erasmus Darwinism” with Lamarck’s ideas betray a “lingering confusion,” given that “The views of Erasmus were in some respects less Lamarckian, and closer to the modern synthesis, than those expressed much later by Charles” (20).

-

[17]

Godwin names fellow-radical Richard Price as another sharer of this doctrine, but the whole passage was dropped in later editions.

-

[18]

Shaw was also converted to vegetarianism by reading Shelley, whose own vegetarian arguments may have been influenced by Erasmus (see Stuart 423, 404).

-

[19]

For Methuselah’s place in the utopian tradition, see Yde 111-42.

-

[20]

For Erasmus as a foundational sci-fi writer see Aldiss 13-14, and Page 1-38.

-

[21]

In her 1831 Introduction to Frankenstein, Mary Shelley describes how her husband Percy’s and Byron’s discussion of “the experiments of Dr Darwin,” supposedly involving the generation of life, lay behind the dream which formed the germ of her novel (M. Shelley 195; see Temple Additional Notes 1, pp. 1-11, and Priestman 132).

-

[22]

For a recent plan to drag icebergs from the Antarctic to provide water for the United Arab Emirates, much as Erasmus Darwin suggested in Economy 1.529-46, see Ian Sample, “Could towing icebergs to hot places solve the world’s water shortages?,” The Guardian Fri 5 May 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/may/05/could-towing-icebergs-to-hot-places-solve-the-worlds-water-shortage

-

[23]

For Erasmus’s drafts for The Progress of Society see Priestman, Appendix to The Poetry of Erasmus Darwin 257-82.

-

[24]

See Priestman 184-92.

-

[25]

As Dyson shows, Butler was as much excited as shocked by the thought of “mind and mechanism” as interchangeable (25-8); see too Amigoni 152-4. But in the passage I have quoted, linking machinery with purely “mechanical” natural selection, the disapproval is clearly uppermost.

-

[26]

See, e. g., Richard Hofstadter. Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860-1915. [1944] Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

-

[27]

Though Charles Darwin himself may have embraced some of the eugenicist theories of his cousin Francis Galton about inherited inferiorities among the more “feckless” social classes, his The Descent of Man (1871) rejected most then-current attempts to link race-divisions to species-divisions, attributing most differences to the more superficial vagaries of sexual selection within an underlying common identity (Desmond and Moore 368, 375).

-

[28]

Knight, The Progress of Civil Society, lines 5.401-2; note to 5.315n; 4.227-30. On the incipiently racist views of early proto-evolutionists such as Lord Monboddo, Petrus Camper and William Lawrence see Fulford, Lee and Kitson 127-48, and Priestman 189. For Erasmus’s opposition to slavery, see Patricia Fara’s essay in this current issue.

-

[29]

See Amigoni on this aspect of Erewhon as a “satire on colonial exploration and exploitation” (156, 161).

-

[30]

Newsreel, March 5, 1931, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hQvsf2MUKRQ Accessed 24.02.2018.

-

[31]

For a useful analysis of Shaw’s engagements with Fascism and Soviet Communism, see Griffith 241-73.

-

[32]

For the links between Malthus and Erasmus Darwin, see Amigoni 36-40.

-

[33]

However, Glenn Clifton stresses the two writers’ differences on these points, arguing that Shaw misreads Butler by seeing the body only as a problem—leading to the many indications of bodily disgust in Methuselah - rather than as an indispensable repository of the inherited memories which make us what we are (108-26).

Bibliography

- Aldiss, Brian. Billion-Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1973.

- Amigoni, David. Colonies, Cults and Evolution: Literature, Science and Culture in Nineteenth-Century Writing. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Beer, Gillian. Darwin’s Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot and Nineteenth-Century Fiction. Third edition. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution. Tr. A. Mitchell. Lanham, MD: Henry Holt, 1911.

- Butler, Samuel. “Darwin Among the Machines”. The Press. Christchurch, New Zealand, 13 June, 1863.

- Butler, Samuel. Erewhon [1872]. Edited by Peter Mudford. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

- Butler, Samuel. Life and Habit. London: Trübner & co., 1878.

- Butler, Samuel. Evolution Old and New: Or, The Theories of Buffon, Dr. Erasmus Darwin and Lamarck, as Compared with that of Charles Darwin [1879]. Second edition revised by R. A. Streatfield. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1911.

- Butler, Samuel. Unconscious Memory: A Comparison Between the Theory of Dr. Ewald Hering and “The Philosophy of the Unconscious” by Dr. Edward von Hartmann. London: David Bogue, 1880.

- Butler, Samuel. Luck, or Cunning As the Main Means of Organic Modification? [1887] Second edition London: Jonathan Cape, 1920.

- Butler, Samuel. The Way of All Flesh. [1903]. London: Page & Co., 1923.

- Butler, Samuel. The Note-Books of Samuel Butler. Ed. Henry Festing Jones. London: A. C. Fifield, 1912.

- Canning, George, George Ellis and John Hookham Frere, “The Loves of the Triangles” in The Anti-Jacobin, or Weekly Examiner. Ed. William Gifford. 2 vols. 4th ed. London: J. Wright, 1799.

- Clifton, Glenn. “An Imperfect Butlerite: Aging and Embodiment in Back to Methuselah”. Shaw, The Annual of Bernard Shaw Studies. Vol. 34, 2014, pp. 108-126.

- Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. First edition. London: Murray, 1859.

- Darwin, Charles. The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter. 3 vols. Ed. Francis Darwin. London: John Murray, 1887.

- Darwin, Erasmus. The Loves of the Plants. First edition. London: J. Johnson,1789

- Darwin, Erasmus. The Botanic Garden (Part 1: The Economy of Vegetation and Part 2: The Loves of the Plants): London: J. Johnson, 1791.

- Darwin, Erasmus. The Economy of Vegetation in The Botanic Garden London: J. Johnson, 1791.

- Darwin, Erasmus. The Loves of the Plants in The Botanic Garden London: J. Johnson, 1791.

- Darwin, Erasmus. Zoonomia, or The Laws of Organic Life. Part One. London: J. Johnson, 1794.