Abstracts

Abstract

This research marks a new attempt to examine the development of new industrial relations actors in contemporary China. It appears that the CMDA has the potential to convert members’ common pursuit into action, albeit with different strengths and patterns compared with its Western counterparts. However, the process of mobilizing doctors is likely to be challenged by China’s unitary industrial relations system. For Chinese doctors, the question is how to convert constant work-related discontent and conflict into an institutional response, and how much freedom the CMDA can be given. Follow-up observation is needed to assess the impact of the CMDA’s continuous expansion in the industrial relations system in China’s health services.

Findings suggest that currently the CMDA is neither an independent union organization, nor a new industrial relations actor within Chinese health services due to its structural weakness and political limitations. Unlike its Western counterparts, the CMDA does not have high levels of social and economic power to control licenses and access to the medical profession. However, the prospect remains that the CMDA may be more active within the industrial relations system if doctors’ social capital and group identity can be further strengthened.

This paper examines possibilities and difficulties for the Chinese Medical Doctor Association (CMDA) to become a new industrial relations actor in China’s health services. It attempts to provide evidence on whether the CMDA functions in similar ways as its Western counterparts in mobilizing members. Aiming at filling the research gap in Chinese professional organizations’ involvement in the industrial relations process, this paper discusses the CMDA’s potential and the challenges of becoming a union organization. Data were collected through 39 semi-structured interviews with supplementation of documentary evidence from the government, doctors’ professional societies, hospitals and trade unions.

Keywords:

- Chinese doctors,

- professional association,

- mobilization,

- industrial relations actor

Résumé

La présente recherche constitue une tentative pour étudier le développement de nouveaux acteurs en relations industrielles en Chine. Il semble que l’AMC ait le potentiel pour transformer les objectifs communs de ses membres en action, bien qu’avec des forces et des moyens différents de ceux de leurs collègues occidentaux. Le processus de mobilisation des médecins chinois risque toutefois d’être contesté par le système unitaire de relations industrielles chinois. Pour les médecins chinois, la question est comment transformer le mécontentement constant lié au travail et les conflits de travail en une réponse institutionnelle et quelle liberté peut être accordée à l’AMC. Il faudra suivre l’évolution de la situation pour voir quel impact aura le développement de l’association sur le système de relations industrielles des services de santé en Chine.

Les résultats de la recherche démontrent qu’actuellement l’AMC n’est ni une organisation syndicale indépendante ni un nouvel acteur du système de relations industrielles vu sa faiblesse structurelle et ses limites politiques. Contrairement à ses homologues occidentaux, l’AMC n’a pas assez de pouvoir social et économique pour contrôler les permis d’exercice et l’accès à la profession médicale. Il y a cependant espoir que l’AMC devienne plus active dans le système de relations industrielles si le capital social des médecins et leur identité de groupe étaient renforcés.

Cet article examine la possibilité que l’Association des médecins chinois (AMC) devienne un nouvel acteur du système de relations industrielles dans les services de santé en Chine. Il cherche à établir si l’AMC fonctionne de la même façon que ses homologues occidentaux dans la mobilisation des membres. Visant à combler un vide dans la recherche sur l’implication des organisations professionnelles chinoises dans le processus de relations industrielles, cet article étudie la possibilité pour l’AMC de devenir une organisation syndicale et les défis que cela représente. Les données, pour ce faire, furent colligées au moyen de 39 entrevues semi-structurées et par la consultation de la documentation pertinente provenant du gouvernement, des sociétés professionnelles médicales, d’hôpitaux et de syndicats.

Mots-clés :

- médecins chinois,

- association professionnelle,

- mobilisation,

- acteur du système de relations industrielles

Resumen

Esta investigación marca un nuevo intento de examinar el desarrollo de nuevos actores de las relaciones laborales en la China contemporánea. Surge a la vista que la AMC tiene el potencial para convertir la búsqueda común de sus miembros en acción, aunque con diferentes fuerzas y modelos comparado a sus homólogos del Oeste. Sin embargo, el proceso de movilización de los médicos deberá probablemente enfrentar el reto del sistema unitario de relaciones laborales en China. Para los médicos chinos, la cuestión es cómo convertir el constante descontento y conflicto vinculado al trabajo en una respuesta institucional, y cómo puede ser conferida una mayor libertad a la AMC. Es necesario seguir con la observación para evaluar el impacto de la continua expansión de la AMC sobre el sistema de relaciones laborales en los servicios de salud de China.

Los resultados sugieren que actualmente la AMC no es una organización sindical independiente ni un nuevo actor de las relaciones laborales en los servicios de salud en China, y esto, debido su debilidad estructural y sus limitaciones políticas. A diferencia de sus homólogos del Oeste, la AMC no tiene niveles altos de poder social y económico como para controlar las licencias y el acceso a la profesión médica. Sin embargo, la perspectiva sigue siendo que la AMC pueda ser más activa dentro del sistema de relaciones laborales si el capital social de los médicos y su identidad de grupo pudieran ser fortalecidas.

Este documento examina las posibilidades y dificultades para que la Asociación de Médicos de China (AMC) se convierta en un nuevo actor de las relaciones laborales de los Servicios de salud en China. Se intenta proporcionar evidencia a saber si la AMC funciona de manera similar que sus homólogos del Oeste en cuanto a la movilización de sus miembros. Con el objetivo de cubrir el vacío de investigaciones sobre la implicación de las organizaciones profesionales chinas en el proceso de relaciones laborales, este documento discute el potencial de la AMS y los retos para convertirse en una organización sindical. Los datos fueron colectados mediante 39 entrevistas semi-estructuradas con datos documentarios adicionales provenientes del gobierno, de las sociedades profesionales médicas, de los hospitales y los sindicatos.

Palabras clave:

- Médicos chinos,

- asociación profesional,

- movilización,

- actor de relaciones laborales

Article body

Introduction

In recent years, the examination of the industrial relations framework has become one of the main focuses of human resource management research in China (Cooke, 2009). Much attention has been paid to conventional industrial relations actors: government organizations such as the labour dispute resolution system (Choi, 2008; Shen, 2007), employers such as state-owned enterprises and multinational corporations (Hassard et al., 2006; Zou and Lansbury, 2009), and the official unions, the ACFTU (All China Federation of Trade Unions) (Ding, Goodall and Warner, 2002; Clarke, 2005). However, comparatively little work has been done to study the role of professional associations such as the Chinese Medical Doctor Association (CMDA).[1] This might be due to two reasons. The first is because many of China’s employment issues had not been noticed until very recently when economic reform exposed more conflicts between employers and employees. The second is that the industrial relations literature on emerging economies is still limited (Greene, 2003: 310).

In Western countries, doctors’ professional associations are traditionally well-organized and vigorous actors in the industrial relation systems. For example one of the major doctors’ professional organizations in the UK, the BMA (British Medical Association), was established in 1832 (Seifert, 1992). The AMA (American Medical Association), the most influential society for medical practitioners in the US, was founded in 1847 (Wynia et al., 1999). In contrast, Chinese doctors did not have their own professional society until 2002 when the CMDA was established. Aiming at representing the interests of China’s 2.1 million practising doctors (CMDA, 2005), the CMDA has expanded significantly since its establishment. To date, it has set up 26 local branches and 38 specialist groups across the country, covering most parts of the public health services. It seems that the CMDA has some similar features to its counterparts in the West: organizing and networking, training and education, and attempting to protect members. The question is, however, whether the CMDA has developed industrial relations functions that have enabled this professional association to effectively defend its members’ interests.

Conventional mobilization theory argues that “collective organization and activity ultimately stem from employer actions that generate amongst employees a sense of injustice or illegitimacy” (Kelly, 1998: 44). However unionization in China is not straightforward. On the one hand, Chinese employees’ growing awareness of employment-related conflicts requires the ACFTU to play a more positive role. On the other hand, the unitary industrial relations system does not allow Chinese unions to independently mobilize workers and collectively bargain with employers (Taylor, Chang and Li, 2003; Clarke, 2005; Cooke, 2008). Nonetheless, the ACFTU is beginning to make efforts to break away from the tight constraint of state corporatism at the very top level (Chan, 2004). In addition, mobilization activities can also be led by alternative workers’ organizations (Kelly, 1998: 100). Therefore, the development of the CMDA may provide Chinese doctors with an alternative mechanism, other than the ACFTU, for having their voice heard.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the emergence of the CMDA in the context of China’s dramatic economic reform. It attempts to provide evidence on whether the CMDA functions in similar ways to its Western counterparts in mobilizing members. Aiming at filling the research gap in Chinese professional organizations’ involvement in the industrial relations process, this paper discusses the CMDA’s potential and the challenges of becoming a union organization. Therefore, the following questions will be addressed. To what extent have Chinese doctors been mobilized by the CMDA to defend their own interests? Has the CMDA turned out to be a new industrial relations actor, or is it the same as a traditional Dunlopian trade union organization? What are the reactions from the government and employers regarding the emergence of the CMDA? What is the distinction between the CMDA and the doctors’ official union, the ACFTU, and between the CMDA and doctors’ professional bodies in the West?

The remainder of this paper is divided into five sections. Firstly, the paper will review mobilization theory and the traditional industrial relations actors’ proposition. Secondly, the nature of doctors and their associations will be discussed, along with an introduction to China’s healthcare system, the state of Chinese doctors and the CMDA. Thirdly, the research methods will be introduced. Fourthly, the paper will analyze the evidence in relation to the CMDA’s major functions by examining the CMDA’s relationship with the ACFTU and doctors’ employers. It will focus on how internal and external factors influence the CMDA’s mobilization function. Finally, the concluding section will discuss the implications and limitations of the research.

New Actors in Industrial Relations Systems

In an industrial relations environment, an actor is “an individual, a group or an institution that has the capability, through its action, to directly influence the industrial relations process, including the capability to influence the causal powers deployed by other actors” (Bellemare, 2000: 386). According to Dunlop, there are three groups of industrial relations actors: managers and their representatives, workers and their organizations, and government agencies concerned with the workplace and work community (Dunlop, 1958: 383). These groups, as Dunlop acknowledges, interact within a certain environment where technology, market and power relations are interrelated.

The three actors’ model is well-known for its categorization of the traditional industrial relation system; however the shortcomings of this model are also widely discussed. For instance, this approach is said to be “incorrectly specified for cross-national research, with national culture being an omitted variable” (Black, 2005: 1140). Bain and Clegg (1974) also claim that Dunlop’s systems theory needs to include both behavioural and structural variables, as well as different relationships in order to cover all aspects of job regulation. Certainly the status of these conventional actors such as workers’ organizations will alter systematically in the course of economic development. For example, small unions may merge into larger organizations to retain bargaining strength.

Apart from changing the status of traditional actors, many new industrial relations actors have been increasingly active in recent years. Some new institutions have emerged in campaigning, advocacy, advisory and service-providing that discharge some union functions, often presented for “a particular segment of the workforce or an identity group” (Heery and Frege, 2006: 602). This is accompanied by a need to re-assess the three actors’ approach, which has been increasingly problematic in explaining many recent changes in the field, including the new relationship between new types of actor (Bellemare, 2000). Meanwhile there has been a renewed call to re-evaluate institutional actors within Dunlop’s systemic framework, but with an update for today’s economy (Heery and Frege, 2006). For instance, the development of European Works Councils has been closely observed following European Union economic integration (see Hall, 2009).

A new actor in industrial relations requires a conscious leadership group and a constituency to mobilize (Dickinson, 2006: 713). To become a genuine actor, one “must not only take action, but also have the capacity to allow other actors to take one’s action into consideration and to respond favourably to some of one’s expectations or demands” (Bellemare, 2000: 386). Many new institutions, mainly representing employees or government bodies, have been emerging in recent years. The emergence of HIV/AIDS peer educators in South Africa is assessed for the potential of becoming workplace industrial relations actors (Dickinson, 2006). In the UK, Abbott (1998) surveyed the possibility of Citizens’ Advice Bureaux becoming new industrial relations actors. In the US, the continuous decline of union membership has created opportunities for alternative institutions to flourish. For example, Employment Rights organizations have been expanding their networks in recent decades (Heckscher and Carre, 2006), while Employment Arbitrators are more active in mediating workplace disputes (Seeber and Lipsky, 2006). The emergence of these institutions offers multiple arenas for industrial relations research, such as the specific form of employee representation and its comparisons with conventional trade unionism (Heery and Frege, 2006: 602).

In China, ongoing economic liberalization and the development of the labour market have generated more opportunities for new industrial relations actors to emerge. Meanwhile one of the traditional actors, the ACFTU, is constrained by insufficient independence. There has been a growing call for the ACFTU “to respond to the constituents’ cry for protection” (Shen, 2007: 521), although it keeps acting as a “transmission-belt” between the Party-state and workers.[2] Two self-contradictory principles, protecting workers’ interests and the affiliation to the Party-state, prevent the ACFTU from independently performing the representation function (Taylor, Chang and Li, 2003). As a result, the challenge to the ACFTU has created new scope for other types of employees’ organizations, such as the doctors’ professional association, to emerge.

Mobilizing Doctors through Professional Organizations

Doctors and Professionalism

Doctors are highly skilled professionals working in health services. They are special because their work is regarded as unusually complex, uncertain and of great social importance (Scott, 1982). In most Western countries, medical professionals such as doctors have been granted certain privileges including high pay, professional powers, and gate keeping control of licensure and entry to professional schooling (Crum, 1991: 3). In China, however, doctors’ pay is not among the “top rank” (Bloom, Han and Li, 2001). In addition, Chinese doctors are not traditionally self-organized and they do not control licensing, nor do they have a gatekeeper function in qualification and accreditation.

An important aspect of the Western doctors’ profession is the perception of professionalism, subject to specialized training, expert knowledge, social status and a certain level of reward (Perkin, 1989). Doctors’ professionalism rests on independence, which gives individual doctors clinical freedom and the profession collectively the authority to decide about the standard and organization of medical work (Irvine, 1997). Some Western doctors work independently or in partnership, and some are even employers of private clinics. Meanwhile, doctors’ professional aspects are supported by the state, whose direct interventions include the creation of professional degrees and the passage of laws for licensing and certification (Cook, 1996). In the UK, a regulatory public body, the General Medical Council (GMC), governs the registration and qualification of doctors in the country. In addition, the GMC also determines the training and education requirements, and monitors doctors’ conduct (Burchill and Casey, 1996). In contrast, there is no such parallel organization in China, and Chinese doctors’ qualification and standards of work are controlled by government health authorities.

Doctors’ Associations in the West

Another aspect of Western doctors is that their professional responsibilities are often supported by internalized controls and reinforced by collegiate associations (Scott, 1982). As Scott notes, much of doctors’ professional practice is assisted by their societies, which consist of a group of highly qualified individuals who are collectively committed to protecting the group interest as a whole. In addition to being an instrument of internal control, doctors’ professional associations in the West are also political bodies. Professional association activities are justified by ideologies highlighting “the importance of the group’s skill for society as a whole” (Gospel and Palmer, 1993: 121). These associations seek to advance members’ interests, backed by state support and doctors’ monopoly position in the provision of specified services. This is done through a professional registration system that protects the public by guaranteeing certain standards, and also generates exclusiveness by requiring qualifications in order to practise (Burchill and Casey, 1996: 49). With such special power, doctors are likely to be able to gain substantial economic and social advantages (Scott, 1982).

Western doctors’ professional groups, such as the British Medical Association (BMA), have traditionally sought to safeguard practitioners’ pay, status and job territory through “legal enactment based on narrowly conceived vested interests” (Seifert, 1992: 46). With a particular position in the labour market, doctors’ professional associations are characterized by their protection function in maintaining and enhancing members’ status and prestige. As Seifert states, professional groups in the NHS have sought to defend “their vested interests” such as “customary pay and conditions” (1992: 49). The BMA, for instance, has strong trade union functions to protect its members. Due to a high level of membership density, organizational independence and integrity, and a relatively strong financial position, the BMA can maintain control over the supply of labour through controlling qualifications and professional discipline (Seifert, 1992).

According to mobilization theory, there are three conditions under which employees are likely to be unionized: a sense of common identity which differentiates employees from the employer, the attribution of any perceived injustice to the employer, and a willingness to engage in some form of collective organization and activity (Kelly, 1998). In the case of doctors, they have a particular way of organizing thanks to their special knowledge, skills and qualifications, as well as their unique identity. Doctors’ monopoly power also helps their collective organizations to pressurize the government and employers in order to protect members’ interests.

Doctors and their Association in China: A Very New Development

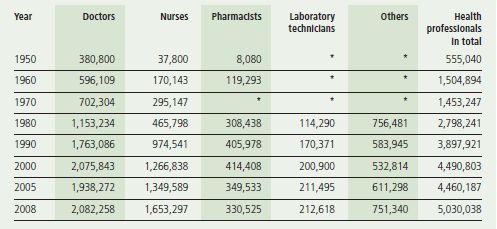

Doctors in China have several distinctive features. Firstly, the majority of doctors (about 90%) work in the public health services[3] (Ministry of Health, 2009), and they are state employees with life-long and secured employment. Government health authorities employ doctors and allocate them to different hospitals and health centres.[4] Private hospitals and clinics have started to emerge in recent years; however public hospitals are more attractive to doctors since they can provide systematic career development opportunities. Secondly, unlike many other countries, China has more doctors than nurses (Anand, 2008). In 1980, the number of doctors was more than twice that of nurses; even in 2008, the number of doctors (2.08 million) was still nearly 500,000 more than that of nurses (see Table 1). Historically, the Chinese health services regarded nurses as low-skilled assistants to doctors and there had been insufficient investment in nurse training and recruitment, causing a severe shortage of frontline nurses (Hu, Shen and Jiang, 2010). As a result, Chinese doctors have been given too heavy duties and workloads. Thirdly, unlike most of their foreign counterparts, who are well-paid professionals, Chinese doctors’ pay is only ranked at the middle level among public sector professions. For instance, higher education professionals and civil servants have a higher level of pay than doctors. Statistics show that the average annual earnings for medical practitioners was 33,830 RMB Yuan in 2008,[5] compared with 44,995 RMB Yuan for higher education staff and 56,652 RMB Yuan for financial service employees (National Bureau of Statistics, 2009).

Table 1

Numbers of Doctors and other Health Professionals in China

To become a doctor in China, one must hold a recognized medical qualification and obtain a licence registered to the health authority. At least five years are needed for formal medical school training, and medical graduates have to work as a junior doctor for a period of time. Then they need to pass relevant exams before their doctor’s licence is awarded by the government health authorities. This legal requirement was only launched in 1999 with the implementation of the Medical Practitioner Act, which also emphasizes doctors’ ethical standards, in an attempt to encourage doctors to “actively protect people’s lives” (Chinese Central Government, 2005).

For Chinese doctors, their own professional association is a relatively new concept. Before the launch of the CMDA in 2002, there was another society, the Chinese Medical Association (the CMA), which had already existed for nearly 90 years. The CMA is open to all occupations and professionals in China’s health services, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, administrative and managerial staff. In contrast, the CMDA is supposed to be “a national, professional and non-profit voluntary organization” exclusively for practising physicians (CMDA, 2005). The main purpose of the CMDA is to provide professional guidance, self-discipline, coordination, promotion of ethical standards and protection of doctors’ legitimate rights. In addition, the CMDA also provides consultation and training services to promote new medical techniques and achievements. Admittedly, the establishment of the CMDA is not based on a desire to build a new union-like institution, but to implement the Chinese government’s agenda to develop the health profession’s academic activity, and to fulfil doctors’ own hope to form an exclusive society.

Research Methods

To investigate the emergence of the CMDA and the possibility of it being a new industrial relations actor, this research deploys qualitative methods. Data were collected through 39 semi-structured interviews with supplementation of documentary evidence from the government, doctors’ professional societies, hospitals and trade unions. By using face-to-face interviews, the researcher was able to collect in-depth data about the influence of the CMDA’s activities in the workplace. In 2004, the researcher visited the CMDA’s national headquarters in Beijing and interviewed one official of its Development Department. Interviews were also conducted with officials in the Ministry of Health, the ACFTU and local health authorities in order to evaluate the CMDA’s relationship with these existing industrial relations actors. In particular, interviews were focused on how the CMDA had attempted to protect members’ interests. Most of the seven interviews during the first visit to Beijing were tape-recorded, except the one with an official from the Ministry of Health, due to participant’s reluctance. During the visit, relevant documentary evidence was collected from these organizations, including the CMDA’s official publications, the handbook and journals for its members.

The second fieldwork was carried out in 2005. The researcher visited two case study hospitals and conducted interviews and collected documentary evidence. One of the case hospitals is located in Guangdong province in southern China. This is a medium-sized county general hospital, with 305 doctors serving a local population of 600,000. The other hospital is in Beijing in northern China, which is larger in scale and size, and with more doctors (424) and better facilities to serve 3 million local residents.[6] As well as for access reasons, these two hospitals were chosen mainly because this research was attempting to find out if and how the CMDA’s activities varied in different types of hospitals and between rural and urban areas.

A total of 24 doctors were interviewed in the two case study hospitals. They were from different departments and with different professional grades. The selection method ensured the representation of different doctors’ opinions about the CMDA’s involvement in the workplace, in the hope to understand how various types of doctors had experienced the CMDA’s activities. Interview questions probed doctors’ feelings about pay, workload, ethical issues and medical disputes, as well as doctors’ expectations about the CMDA’s involvement in protecting their rights and benefits. Interviewees also included eight managers and hospital union officials, to understand hospital managements’ perceptions of the CMDA and the official union’s role in representing doctors in the workplace. Most interviews were tape-recorded except the ones with two directors from both case hospitals due to the participants’ refusal. Follow-up data were collected via emails and telephone after the second field visit to gather updated documentary evidence about the case study hospitals, doctors’ professional societies and unions. The new data ensure that the researcher can use up-to-date sources to reflect the continuous development of the CMDA.

Findings

The trade union aspects of medical practitioners’ associations are based on the notion of professionalism, and strong financial and political positions which enable associations to confront employers (Seifert, 1992). To examine the extent to which the CMDA can represent members’ interests, it is necessary to look at its membership and funding, professional integrity, training and education activities, and functions of protecting members’ rights. In addition, it is essential to distinguish the CMDA from the ACFTU, and to clarify the CMDA’s relationship with the Party-state as well as with doctors’ employers.

The Party-State Control, Membership and Funding

As a professional society affiliated to the Ministry of Health, the CMDA is like other Chinese associations that are constrained by the Party-states’ political control (Unger, 2008). The majority of the senior management working in the CMDA used to work in central or local governments or hospitals as high ranking officials. For example, the CMDA president was previously the vice Health Minister. The CMDA president, general secretary and other senior officials are nominated by the Ministry of Health before they are “elected” symbolically by the association’s council members. In theory, members of the CMDA can raise concerns; however in practice, doctors are not able to exert influence in policy-making. The CMDA officials are not democratically elected; therefore they do not have to pursue doctors’ interests. Instead, the CMDA’s loyalty to the Party and dependence on the government means it is closely connected to the Party-state. For instance, if the CMDA wants to appoint some managers, the appointment must be agreed by the Ministry of Health. As the CMDA Charter declares, “the association accepts the leadership, supervision and management of the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Civil Affairs” (CMDA, 2005). This is confirmed by a CMDA official: “As an affiliated organization, our leaders are all nominated and appointed by the Ministry of Health. Our Party committee belongs to the Ministry Party system” (interview, CMDA).

Although there is no financial and personnel relations between them, both national and local CMDA organizations recruit members at the same time. For instance, a surgical doctor in Guangdong’s case hospital said that he did not know whether his CMDA membership was for the provincial CMDA or the national one. Therefore the recruitment of members has become a problem, as doctors may join the organization at both local and national levels. Doctors can also join CMDA specialist sub-branches as long as they are willing to pay the necessary fees. Given that there are many group (or collective) members, it has become very difficult to know exactly how many members the CMDA has. In addition, it appears that the CMDA is more active in the Beijing case hospital than the one in Guangdong, showing an urban-rural difference.

At the moment, an immediate challenge to the CMDA is how to find enough funding. Because the government does not provide any subsidy, the CMDA has to raise income from membership charges, donations and advertisements. As individual membership fees are low, much of the CMDA’s income comes from charges for “collective membership” – the hospital members and enterprise members. In addition, academic activities such as conferences, training programmes and publications, can also generate income.

The national official interviewed admitted that there was insufficient support from the government and the CMDA had suffered from financial difficulties. He noted that:

Each year we spend about 40 million Yuan, 75% of which comes from the income from publishing medical magazines, and 25% from advertisements or other activities. The contributions of individual membership fees to us are small and limited, and many doctors are reluctant to pay more. So finance is a big issue for our survival.

The funding issue also has an impact on the CMDA’s structure, as the “Business Development Department” is set up to generate more income through business activities. This seems to be ironic considering the CMDA’s voluntary and non-profit principle. Furthermore, receiving collective members’ fees may have a negative impact on its independence and undermine the CMDA’s function of representing doctors’ interests.

Professional Integrity

The integrity of medical professionalism is fundamental to the CMDA’s commission. According to the 1999 Medical Practitioner Act, the CMDA has legitimate rights to defend doctors’ professional integrity. As the CMDA’s Charter states, doctors’ professionalism requires prioritizing patients’ interests, and maintaining standards of competence and integrity (CMDA, 2005). It reads:

The principles and responsibilities of medical professionalism must be clearly understood by both the profession and society. Essential to this contract is public trust in physicians, which depends on the integrity of both individual physicians and the whole profession (CMDA Charter, 2005).

Ethical issues and professional self-discipline are the major activities relating to the CMDA’s aim of maintaining professional integrity. Within the CMDA there has been a “National Doctors’ Ethics Committee” to supervise doctors’ ethical issues. For example, over the years, many Chinese doctors have received patients’ money (red packets) privately in exchange for providing better or faster service. Although receiving red packets is common practice in many parts of society, it is still conceived as illegal bribery and is against doctors’ ethics requirements. During the fieldwork, many doctors and hospital managers admitted that red packets existed in both hospitals. For the CMDA, red packets behaviour should be prohibited, but the CMDA has little influence on hospital management. Therefore the CMDA can only publish a series of documents, or organize training programmes, calling on doctors to be more self-disciplined.

Without an effective sanction mechanism, the CMDA’s effort to deal with doctors’ red packets behaviour seems weak. As the CMDA national official said:

We understand the damage of the red packets phenomenon to doctors’ reputation, and we have been working very hard along with health authorities and hospitals to educate doctors. [He also claimed that] We genuinely want to strengthen doctors’ morality, because this is the basis of protecting and promoting doctors’ social status.

However, when the researcher asked doctors about red packets in both case hospitals, nobody mentioned the activities of the CMDA’s Ethics Committee. It appears that the CMDA’s influence in the workplace needs to be strengthened.

Training and Education

Organizing training activities and academic conferences are important functions for the CMDA. In particular, its further education programmes are supported by the government and some of the learning credits are connected with doctors’ promotion. At the same time, these academic activities are a good source of income for the CMDA, and hospitals or local health authorities usually pay for their doctors to attend. Periodically doctors have to take “continuation education programmes,” which can generate a stable income for the CMDA. On the other hand, the CMA, as another professional society in the health service, has larger scale training and education programmes because of its much longer history in providing the service. There has been some degree of competition on who should provide what kind of training, and who can benefit from the income. In theory, there is no direct relationship between these two organizations, although both are affiliated to the Ministry of Health and have similar training and education functions for medical professions. Since the distinction between the CMDA and CMA is less clear, it is felt that both organizations provided similar services in their conferences, publications and training programmes.

The training and further education programmes provided by the CMDA were welcomed by doctors. One consultant in the Beijing hospital thought it was always good for academic exchange or training opportunities, and often the CMDA invites an external specialist to come to the hospital to deliver a guest lecture. Some doctors even complained about the lack of opportunity to attend CMDA’s academic activities. One paediatric doctor in the Guangdong hospital said that the training system was not properly operated, because the “distribution of training organized by the CMDA is not always fair.” Overall, there were more positive responses. One gynaecology obstetrician said:

We doctors do appreciate those CMDA training opportunities, which are always very good at improving our skills and techniques. By attending external conferences and training courses, we will be able to get in touch with more specialists and gain more new information (interview, Guangdong case hospital).

Managers also expressed their positive attitudes towards the CMDA’s training and education programmes. Because many of these schemes are organized and funded by health authorities, hospitals do not have to consider the cost. The vice-director of the case study hospital in Guangdong claimed: “We welcome the CMDA’s provision for further education programmes for doctors, as training is an important strategy in improving doctors’ capability and skills.” Meanwhile, hospital managements would like to use training opportunities to improve doctors’ commitment and performance.

Protection of Doctors’ Legitimate Rights

In recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in medical disputes in Chinese hospitals (Wang, 2010), and the CMDA has increased its activities in helping doctors to protect their legal rights. Part of the 1999 Medical Practitioner Act’s initiatives is to provide statutory protection for licensed doctors in China (Gao and Yang, 2006), which is also one of the principles of the CMDA. At national level, the CMDA has set up a special organization, the Doctors’ Rights Protection Committee, to oversee the issue of protecting doctors’ interests and legal rights.

Research has found that many medical disputes in China are related to the recent health service marketization reform, which has made patients pay much more to hospitals than before (Blumenthal and Hsiao, 2005). When patients are unhappy with the services, they are more likely to express their discontent to the frontline health workers, especially doctors. Evidence from both hospitals shows that many doctors were not happy with their stressful working environment, long working hours and a low level of payment that did not properly reward their professional contribution. When they were misunderstood by some patients and their families, doctors felt that somebody should stand up to protect practitioners’ own interests. As a doctor stated:

I was very scared when some patients’ family members rushed into my office, shouting at me and accusing me of negligence. It was actually not our fault but they didn’t understand. Sometimes our hospital was unable to fully protect us because our leaders did not want to be involved in disputes (interview, Beijing case hospital).

Although the CMDA has attempted to deal with medical related disputes, in practice it is quite difficult because of the complicated legal process of mediation and arbitration.

Doctors’ Perceptions of the CMDA

Evidence shows that doctors felt the CMDA was purely an academic society with no influence at all on work conditions or pay. They joined the CMDA to access more learning and training opportunities, rather than to seek institutional help to safeguard their status. Doctors understood that the CMDA could not represent members to confront hospital management. As one doctor in the Beijing case study hospital said:

In China, there is no freedom for any person or organization to fight against government institutions. Thus it is difficult for the CMDA to disagree with hospitals that are managed by health authorities.

Since the CMDA has no industrial relations functions, its relationship with medical doctors is mainly educational and academic.

It is not always easy for doctors to distinguish between the CMDA and CMA, although they had joined these organizations because everybody else had done so. A paediatric consultant from the case study hospital in Guangdong said:

I do not know whether I have subscribed membership to the CMDA or the CMA, or both. I am not sure of the differences between them, as the finance department just deducts my membership fees.

The CMDA and Hospitals

The CMDA has no direct relationship with the doctors’ employers, i.e. hospitals, due to its voluntary nature. As a professional body, the CMDA has no authority to intervene in a hospital’s operation, including the management of personnel affairs such as pay.

Usually the CMDA does not need to send its officials to the workplace, as training, conference or membership recruitment activities are carried out through local health authorities. Hospitals are happy to support a professional association’s work, on condition that there is no budget constraint. It is evident in the statement by the director of the case study hospital in Beijing:

We fully support the CMDA’s activities in training and further education. If it is needed we will send doctors to attend CMDA conferences unless they are too expensive.

Although the CMDA is distant from hospital management, some of its functions are relevant to human resource practices such as pay. In both case study hospitals, there has been increasing discontent among doctors regarding their pay level, the distribution of bonuses and pay determination methods. This issue is related to the CMDA’s perceived function of protecting doctors’ interests, despite the fact that legally this association is unable to represent members for negotiating pay. The CMDA acknowledged its concerns about doctors’ income, which had been influenced by the marketization of the health services and the government’s insufficient funding. As one CMDA official said:

We actually have no influence on doctors’ pay at all, although in the future doctors’ income might become a key concern. [He admitted that] now our participation in the workplace is mainly through providing training, further education and conferences for doctors.

The CMDA and the ACFTU

A comparison of these two organizations can be found in Table 2. Evidence from the case study indicates that the CMDA has not become a union organization, but it does have some similar features to the doctors’ union, the ACFTU. First, both the ACFTU and CMDA are subordinated to the Party leadership and health authorities. Second, neither the CMDA nor the ACFTU has the right to carry out collective bargaining; the major reason that doctors join the ACFTU or the CMDA is for welfare or academic reasons. Third, both organizations have very limited impact on doctors’ pay and working conditions, although in theory their aims are to protect their members’ interests.

Table 2

CMDA and Doctors’ Trade Unions at Hospitals

There are some clear distinctions between the CMDA and ACFTU. The CMDA is aimed at providing professional services, rather than representing doctors within the industrial relations system. Members of the CMDA are mainly doctors and there is no full-time official representing the CMDA in the workplace. By contrast the ACFTU is well organized at grassroots level as it is embedded in the hospital administrative structure, and its membership is open to all hospital staff. As part of the management system, the ACFTU is well supported both financially and politically by hospitals. The ACFTU is very close to the hospital management hierarchy, as the hospital union chair is also a Party committee member. The comprehensive network has helped the ACFTU to maintain a high union density in hospitals, whereas the CMDA has to find its own ways to recruit new members. Nonetheless, the ACFTU is mainly involved with staff welfare and entertainment activities, rather than representing members to confront or challenge management.

Discussion

These findings have highlighted the structural weaknesses that limit the CMDA from becoming an independent trade union organization. The CDMA’s affiliation to the government has also weakened its independence. Unlike many doctors’ associations in the West that have industrial relations functions, the CMDA mainly works for academic purposes. No evidence has been found to indicate that the CMDA can represent members politically; neither can it take part in members’ pay determination or any management decision-making process. Instead, the CMDA is organized like many other professional associations in China, whose expansion is constrained by limited professional autonomy and tight state intervention (Gu and Wang, 2005). Because doctors’ official unions are also not able to effectively represent members, hospital management is in a strong position when dealing with the management-labour relationship. As a result, Chinese doctors’ collective response is insignificant, and their discontent is expressed in individualistic ways such as personal complaints.

Evidence suggests that currently the CMDA is neither an independent union organization, nor a new industrial relations actor within Chinese health services. Several elements contribute to this fact. There is little political and legal support for independent unionization in China. As a result the CMDA has no power to exercise its true autonomy, since the success of mobilization is closely related to the situation where unions can have greater legal rights (Kelly, 1988: 49).

Another reason is that the CMDA lacks strong, capable and independent leadership. As senior officials of the CMDA are appointed by health authorities and many of them are also Party members, it is not surprising to see the CMDA’s subordination to Party-state control. As Heery et al. (2004: 17) emphasize, union leaders need to be more representative because leaders must share the identity of those they seek to represent. Moreover, the CMDA has financial difficulties, as the shortage of funding has limited its independence and role as a voluntary organization. The CMDA has accepted hospital and enterprise members as a means to compensate for the financial deficit. Collective membership will undermine the CMDA’s professional integrity and will result in conflicts of interest between protecting doctors’ interests and supporting hospitals. Evidence shows that the CMDA has more influence in urban hospitals than rural ones, due to imbalanced medical service development between these two areas. There are also structural weaknesses for the CMDA, as its membership is overlapped and unclearly categorized. It is not easy for organizations to develop members’ collectivism and loyalty with blurred identification (Cregan et al., 2009).

In addition, doctors’ individualistic behaviour has undermined their potential to take collective action. The CMDA’s relationship with doctors is not one between an independent union and its members, but more of a relationship between academic service provider and its customers. It is common practice for doctors to accept red packets as informal payment to increase their income, while some doctors may have chosen to leave their jobs. By choosing to “exit”, doctors are not able to take any further collective action, and the increase of informal income may reduce doctors’ willingness to pressurize employers to increase their pay.

On the other hand, findings also indicate that possibilities remain for the CMDA to be involved in the industrial relations process. Firstly, workplace conflict is a pre-condition for the CMDA to raise its collective voice. In fact, there has been increasing discontent from doctors regarding their pay and work conditions. Employee dissatisfaction, workplace injustice and related collective interest are the first step of a mobilization process (Kelly, 1998). With consistent injustice, unions may use “a more moral alternative to persuade members to restore justice through collective action” (Johnson and Jarley, 2004: 555). Yet dissatisfaction is not necessarily connected with a growing willingness to unionize (Charlwood, 2002). The CMDA would need to raise the awareness of the members that collective action is a way forward to get the dissatisfaction and workplace injustice resolved, but it is not clear whether the CMDA would head in this direction.

Secondly, the CMDA has some essential features that can help it to organize members collectively. Unlike many Western doctors who work in partnership or as employers of private clinics, the majority of Chinese medical doctors are state employees. This provides a potential “constituency” for future mobilization activities and a better opportunity for the CMDA to perform some of the trade union functions. In particular, training and education can provide doctors with more opportunities to upgrade their skills and meet together to discuss common issues. Training and conferences are good opportunities to expand networking within professional circles, as the educational environment provides a context of interaction between members (Kirton and Healy, 2004). The provision of training can help trade unions to pursue conscious strategies for the expression of the collective employee voice (Munro and Rainbird, 2004). Education has the potential to transform organizations into more inclusive unions that have clearer collective targets (Kirton and Healy, 2004). The CMDA’s institutional framework and network have set up a good platform for doctors to develop their social capital and group identity.

Thirdly, the inability of the ACFTU to mobilize Chinese workers provides a further opportunity for doctors in China to seek help from alternative institutions such as their professional association, the CMDA. It has been argued that “a weak trade union or lack of independent trade unionism does not mean that there is no workers rights protection in China” (Shen, 2006: 367). The absence of the ACFTU in the workplace has provided more opportunities for other collective organizations such as the CMDA to develop. Data indicate that more effective communication channels between hospital management and doctors are needed. It may not be long before Chinese doctors start to use the CMDA as a platform to defend their common interests. As Taylor, Chang and Li indicate, when Chinese workers become more conscious of their interests as a social group, they may try to “use their social capital as a basis on which to transform a common interest into collective action” (2003: 342).

Conclusion

This paper has examined the possibilities and difficulties for the CMDA to become a new industrial relations actor. It finds that the CMDA has not become an independent Dunlop-type union due to its structural weaknesses and political limitations. Unlike its Western counterparts, the CMDA does not have high levels of social and economic power to control licenses and access to the medical profession. However, the prospect remains that the CMDA may be more active within the industrial relations system if doctors’ social capital and group identity can be further strengthened. In the context of China’s continuous economic liberalization and official trade unions’ powerlessness (Clarke, 2005), the CMDA’s institutional expansion may help to increase its chance to better represent and defend members’ interests.

This research marks a new attempt to examine the development of new industrial relations actors in contemporary China. It appears that the CMDA has the potential to convert members’ common pursuit into action, albeit with different strengths and patterns compared with its Western counterparts. However, the process of mobilizing doctors is likely to be challenged by China’s unitary industrial relations system. On the one hand, organizing health professionals may help the government to ease workplace conflict and maintain stability. On the other hand, it is not easy for the CMDA to develop its political power and challenge the Party-state and employers’ authority.

The findings of the study highlight the significance of the CMDA, a society representing the largest number of medical practitioners in the world. As the majority of Chinese doctors are public hospital employees, the CMDA may have a good chance to perform some functions of trade unions, for instance representing doctors to pressurize government to enhance doctors’ status or increase income. Mobilization requires employees to perceive and respond to injustice and assert their rights (Kelly, 1998: 51). For Chinese doctors, the question is how to convert constant work-related discontent and conflict into an institutional response, and how much freedom the CMDA can be given. Follow-up observation is needed to assess the impact of the CMDA’s continuous expansion in the industrial relations system in China’s health services.

This study is constrained in part by deficiencies in Chinese official statistics. This is echoed by research conducted by Cooke that, in the social science research area, “statistical deficiency in the Chinese statistical system has often been a major barrier for researchers wishing to carry out more in-depth analyses” (2008: 134). It is hard to establish the accurate figures about CMDA membership because there is overlapping recruitment between the CMDA’s national organization, and its local and specialty sub-branches. This has made it difficult to precisely reflect CMDA’s membership density – an important indicator for analyzing the extent of unionization.

Appendices

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Editors, the anonymous reviewers, Carole Thornley and Dave Lyddon for their helpful comments.

Note biographique

Xuebing Cao is Lecturer in Human Resource Management at Keele Management School, Keele University, Staffordshire, UK.

Notes

-

[1]

“Doctors” in China mean licensed medical practitioners including surgeons, dentists and technical professionals in health services. In this study, all doctors are from public hospitals where the majority of Chinese doctors work.

-

[2]

A transmission belt is used to signify the way in which Chinese trade unions act as a link between the Party-state and workers, transmitting policies to workers and reflecting workers’ opinion through “democratic management” (White, 1996: 437).

-

[3]

In recent years, there have been many changes in China’s health services: an urban health insurance scheme is being launched by the government and in rural areas, a new co-operative medical system is being set up. However, it is said that government health expenditure is still insufficient and the on-going public health reform has been criticized for lack of fairness and easy-access (Blumenthal and Hsiao, 2005).

-

[4]

Health centres are set up by Chinese health authorities to provide basic medical services to community residents in both urban and rural areas. They are more convenient than hospitals. However, public hospitals are more appealing to patients because they have better facilities and higher quality of service.

-

[5]

The RMB Yuan is China’s currency. In December 2010, one US Dollar was worth approximately 6.65 Yuan.

-

[6]

It should be noted that there are many public hospitals in every region. Around the Beijing case study hospital, there are about twenty other general hospitals. In Guangdong’s case, there are four general hospitals in the same county. In addition, there are also some private hospitals and clinics in each region.

References

- Abbott, B. 1998. “The Emergence of a New Industrial Relations Actor: The Role of the Citizens’ Advice Bureaux?” Industrial Relations Journal, 29 (4), 257-270.

- Anand, S., V. Fan, J. Zhang, L. Zhang, Y. Ke, Z. Dong and L. Chen. 2008. “China’s Human Resources for Health: Quantity, Quality, and Distribution.” Lancet, 375 (November), 1774-1781.

- Bain, G. S. and H. A. Clegg. 1974. “Strategy for Industrial Relations Research in Great Britain.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 12 (1), 91-113.

- Bellemare, G. 2000. “End Users: Actors in the Industrial Relations System?” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 38 (3), 383-405.

- Black, B. 2005. “Comparative Industrial Relations Theory: The Role of National Culture.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16 (7), 1137-1158.

- Bloom, G., L. Han and X. Li. 2001. “How Health Workers Earn a Living in China?” Human Resources for Health Development Journal, 5, 25-38.

- Blumenthal, D. and W. Hsiao. 2005. “Privatization and Its Discontents: The Evolving Chinese Health Care System.” The New England Journal of Medicine, 353 (11), 1165-1170.

- Bryson, A. and R. Gomez. 2005. “Why Have Workers Stopped Joining Unions? The Rise in Never-Membership in Britain.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43 (1), 67-92.

- Burchill, F. and A. Casey. 1996. Human Resource Management, The NHS: A Case Study. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Chan, A. 2004. “Some Hopes for Optimism for Chinese Labour.” New Labour Forum, 13 (3), 67-75.

- Charlwood, A. 2002. “Why Do Non-union Employees Want to Unionize? Evidence from Britain.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 40 (3), 463-491.

- Chinese Central Government. 2005. The Medical Practitioner Act. Beijing: China Law Press.

- Choi, Y. 2008. “Aligning Labour Disputes with Institutional, Cultural and Rational Approach: Evidence from East Asian-invested Enterprises in China.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19 (10), 1929-1961.

- Clarke, S. 2005. “Post-Socialist Trade Unions: China and Russia.” Industrial Relations Journal, 36 (1), 2-8.

- CMDA. 2005. “The CMDA Charter.” Selected Documents of Chinese Medical Doctors Association. Beijing: Ministry of Health.

- Cook, P. 1996. The Industrial Craftsworker: Skill, Managerial Strategies and Workplace Relationships. London: Mansell.

- Cooke, F. L. 2008. “The Changing Dynamics of Employment Relations in China: An Evaluation of the Rising Level of Labour Dispute.” Journal of Industrial Relations, 50 (1), 111-138.

- Cooke, F. L. 2009. “A Decade of Transformation of HRM in China: A Review of Literature and Suggestions for Future Studies.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 47 (1), 6-40.

- Cregan, C., T. Bartram and P. Stanton. 2009. “Union Organizing as a Mobilizing Strategy: The Impact of Social Identity and Transformational Leadership on the Collectivism of Union Members.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 47 (4), 701-722.

- Crum, G. 1991. “Professionalism and Physician Reimbursement.” Paying the Doctor: Health Policy and Physician Reimbursement. J. Moreno, ed. New York: Auburn House.

- Dickinson, D. 2006. “Fighting for Life: South Africa HIV/AIDS Peer Educators as a New Industrial Relations Actor?” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 44 (4), 697-717.

- Ding, D., K. Goodall and M. Warner. 2002. “The Impact of Economic Reform on the Role of Trade Unions in Chinese Enterprises.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13 (3), 431-449.

- Dunlop, J. T. 1958. Industrial Relations Systems. New York: Holt.

- Gao, H. and J. Yang. 2006. “The Implications of the American Medical Licensing Examination to the Examination System for Chinese Doctors’ License.” Chinese Medical Ethics, 108, 84-85.

- Gospel, H. and G. Palmer. 1993. British Industrial Relations. 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

- Greene, A. 2003. “Women and Industrial Relations.” Understanding Work and Employment: Industrial Relations in Transition. P. Ackers and A. Wilkinson, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gu, X. and X. Wang. 2005. “From Statism to Corporatism: Changes in the Relationship between the State and Professional Associations in the Transition to Market Economics in China.” Sociologic Review, 106, 351-369.

- Hall, M. 2009. “Behind the European Works Councils Directive: The European Commission’s Legislative Strategy.”British Journal of Industrials Relations, 30 (4), 547-566.

- Hassard, J., J. Morris, J. Sheehan and Y. Xiao. 2006. “Downsizing the Danwei: Chinese State-Enterprise Reform and the Surplus Labour Question.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17 (8), 1441-1455.

- Heckscher, C. and F. Carre. 2006. “Strength in Networks: Employment Rights Organizations and the Problem of Co-Ordination.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 44 (4), 605-628.

- Heery, E. and C. Frege. 2006. “New Actors in Industrial Relations.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 44, 601-604.

- Heery, E., G. Healy and P. Taylor. 2004. “Representation at Work.” The Future of Worker Representation. G. Healy, E. Heery, P. Taylor and W. Brown, eds. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hu, Y., J. Shen and A. Jiang. 2010. “Nursing Shortage in China: State, Causes, and Strategy.” Nursing Outlook, 58 (3), 122-128.

- Irvine, G. 1997. “The Performance of Doctors: Professionalism and Self Regulation in a Changing World.” British Medical Journal, 314 (24), 1540-1542.

- Johnson, N. and P. Jarley. 2004. “Justice and Union Participation: An Extension and Test of Mobilization Theory.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 42 (3), 543-562.

- Kelly, J. 1998. Rethinking Industrial Relations: Mobilization, Collectivism and Long Waves. London: Routledge.

- Kirton, G. and G. Healey. 2004. “Shaping Union and Gender Identities: A Case Study of Women-only Trade Union Courses.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 42 (2), 303-323.

- Martin, R. 1999. “Mobilization Theory: A New Paradigm for Industrial Relations.” Human Relations, 52 (9), 1205-1216.

- Ministry of Health. 2009. China Health Statistic Yearbook 2009. Beijing: China Union Medical University Press.

- Munro, A. and H. Rainbird. 2004. “The Workplace Learning Agenda: New Opportunities for Trade Unions?” The Future of Worker Representation. G. Healy, E. Heery, P. Taylor and W. Brown, eds. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2009. China Statistical Yearbook 2009. Beijing: China Statistic Press.

- Perkin, H. 1989. The Rise of Professional Society: England since 1880. London: Routledge.

- Scott, W. R. 1982. “Managing Professional Work: Three Models of Control for Health Organizations.” Health Services Research, 17 (3), 213-240.

- Seeber, R. and D. Lipsky. 2006. “The Ascendancy of Employment Arbitrators in US Employment Relations: A New Actor in the American System?” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 44 (4), 719-756.

- Seifert, R. 1992. Industrial Relations in the NHS. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Shen, J. 2006. “An Analysis of Changing Industrial Relations in China.” International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 22 (3), 347-368.

- Shen, J. 2007. “The Labour Dispute Arbitration System in China.” Employee Relations, 29 (5), 520-539.

- Taylor, B., K. Chang and Q. Li. 2003. Industrial Relations in China. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Unger, J. 2008. “Introduction: Chinese Associations, Civil Society, and State Corporatism: Disputed Terrain.” Associations and the Chinese State: Contested Spaces. J. Unger, ed. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe.

- Wang, S. 2010. “Doctors at Receiving End in Medical Reform.” China Daily, 25 March.

- White, G. 1996. “Chinese Trade Unions in the Transition from Socialism: Towards Corporatism or Civil Society?” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 34 (3), 433-457.

- Wynia, M., S. Latham, A. Kao, J. Berg and L. Emanuel. 1999. “Medical Professionalism in Society.” New England Journal of Medicine, 341, 1612-1616.

- Zou, M. and R. Lansbury. 2009. “Multinational Corporations and Employment Relations in the People’s Republic of China: The Case of Beijing Hyundai Motor Company.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20 (11), 2349-2369.

List of tables

Table 1

Numbers of Doctors and other Health Professionals in China

Table 2

CMDA and Doctors’ Trade Unions at Hospitals