Abstracts

Abstract

Research objective: Through relatively higher unionization rates within the casino industry, casino employment provides a counterexample to the connection between low-skill service work and low wages. The existing literature, however, suggests that casino workers embrace a commodified vision of their labour. It is of interest to understand whether and how unions are successful in decommodifying both ideologically and materially, wage entitlements in this expanding industry as this is a main mechanism through which unions challenge income inequality. This article examines the Canadian Auto Workers’ (CAW) attempt to decommodify wages in the casino industry.

Methodology: These findings are based on a case study of Casino Windsor, located in Windsor, Ontario—the automotive capital of Canada and the first city to host a resort casino outside of Atlantic City and Las Vegas. Ninety-one interviews were conducted with Windsor stakeholders (20), and automotive (43) and casino (28) workers. The local newspaper from 1994-2014 is also examined and descriptive statistics are utilized.

Results: Casino workers initially did adopt a decommodified vision of wage entitlements; yet, due to political—the New Democratic Party of Ontario—and institutional—low sectoral union density—forces, casino workers during 2014-2015 interviews embrace a service mind where wages are determined by a market-oriented human capital model.

Conclusions: CAW union representatives and the casino membership now view the CAW’s attempt to bring an industrial mindset into the casino as a mistake, naturalizing the link between decommodified wages in automotive manufacturing and the market-oriented wage entitlements of the service sector. This case study marks a critical lost opportunity by the CAW to decommodify wage entitlements in the casino industry and the broader service sector.

Keywords:

- labour union,

- casino,

- wage,

- service sector,

- employment

Résumé

Objectif de recherche : Grâce à des taux de syndicalisation relativement plus élevés dans les casinos, l’emploi dans ce secteur constitue un contre-exemple du lien entre travail de service peu qualifié et bas salaires. La littérature existante, cependant, suggère que les travailleurs de casino adoptent une vision marchandisée de leur travail. Il est intéressant de cerner si et comment les syndicats parviennent à « démarchandiser », tant idéologiquement que matériellement, les salaires dans cette industrie en expansion, car il s’agit là d’un mécanisme important par lequel les syndicats peuvent parvenir à remettre en question les inégalités de revenus. Cet article examine la tentative des Travailleurs canadiens de l’automobile (TCA) de « démarchandiser » les salaires dans le secteur des casinos.

Méthodologie : Ces résultats sont fondés sur une étude de cas du Casino Windsor, situé à Windsor, en Ontario — la capitale de l’automobile au Canada et la première ville à accueillir un casino « station de vacances » (resort casino en anglais) en dehors d’Atlantic City et de Las Vegas. Au total, 91 entrevues furent réalisées, soit 20 avec des intervenants de Windsor, 43 avec des travailleurs de l’automobile et 28 avec des salariés du casino. De plus, le journal local fut dépouillé de 1994 à 2014, et des statistiques descriptives furent analysées.

Résultats : Les travailleurs du casino ont initialement adopté une vision « démarchandisée » de leurs droits salariaux; cependant, en raison des forces politiques — le Nouveau Parti démocratique de l’Ontario — et des forces institutionnelles — de faible densité syndicale dans le secteur des services —, les employés de casino, durant les entrevues menées en 2014-2015, adoptèrent une « vision service » (en anglais, service mind approach), où les salaires sont déterminés par un modèle de capital humain axé sur le marché.

Conclusions : Les représentants syndicaux des TCA et les membres du syndicat du casino voient maintenant la tentative des TCA d’introduire une « mentalité industrielle » dans le casino comme une erreur. À présent, ces derniers naturalisent le lien entre salaires « démarchandisés » dans l’industrie automobile et salaires marchands du secteur des services. Cette étude de cas illustre une occasion manquée par les TCA de démarchandiser les salaires dans le secteur des casinos et des services en général.

Mots-clés:

- syndicat,

- casino,

- salaire,

- secteur des services,

- emploi

Resumen

Objetivo de investigación: Gracias a las tasas de sindicalización relativamente más altas en la industria de los casinos, el empleo en ese sector constituye un contraejemplo del vínculo entre trabajo de servicios poco calificado y los bajos salarios. La literatura existente sugiere, sin embargo, que los trabajadores de casino adoptan una visión mercantilizada de su trabajo. Es interesante comprender si los sindicatos logran “desmercantilizar” los beneficios salarios en esta industria en expansión, y cómo lo hacen, tanto ideológicamente como materialmente, pues se trata de un mecanismo importante por el cual los sindicatos pueden cuestionar las desigualdades de ingresos. Este artículo examina la tentativa de los Trabajadores automotrices canadienses (TCA) de “desmercantilizar” los salarios en el sector de los casinos.

Metodología : Esta resultados se basan en un estudio de caso del Casino Windsor, situado en Windsor, Ontario --- la capital del automóvil en Canadá y la primera ciudad a recibir un casino de tipo « complejo vacacional » (resort) a parte de Atlantic City y de Las Vegas. En total, se realizaron 91 entrevistas, 20 con inversionistas de Windsor, 43 con los trabajadores del automóvil et 28 con empleados del casino. Además, el periódico local fue analizado de 1994 a 2014 y las estadísticas descriptivas fueron analizadas.

Resultados : Los trabajadores del casino han adoptado inicialmente una visión “desmercantilizada” de los beneficios salariales, sin embargo en razón de las fuerzas políticas - el Nuevo Partido Democrático de Ontario – y de las fuerzas institucionales – baja densidad sindical en el sector de servicios --, los empleados de casino durante las entrevistas llevadas a cabo en 2014-2015, adoptaron una visión servicio (service mind), en la cual los salarios son determinados por un modelo de capital humano orientado hacia el mercado.

Conclusiones: Los representantes sindicales del TCA y los miembros del sindicato del casino ven ahora como un error la tentativa del TCA de introducir una « mentalidad industrial » en el casino que naturalizan el vínculo entre salarios “desmercantilizados” en la industria del automóvil y salarios mercantiles del sector de servicios. Este estudio de caso ilustra una ocasión perdida crítica por parte del TCA para “desmercantilizar” los beneficios salariales en el sector de casinos y de servicios en general.

Palabras claves:

- sindicato,

- casino,

- salario,

- sector de servicios,

- empleos

Article body

Casinos and the Decommodification of Wages

Policymakers have increasingly used casinos as a strategy to create ‘good’ service jobs in regions that have lost or are losing their primary industries, like manufacturing. Through relatively higher unionization rates within the casino industry, casino employment provides a counterexample to the connection between low-skill service work and low wages (Waddoups, 2002; Waddoups and Eade, 2013). Existing research, however, suggests that casino workers embrace a commodified understanding of labour (Mutari and Figart, 2015; Sallaz, 2002; Taft, 2016). Whether unions are successful in materially and ideologically decommodifying wage entitlements in the expanding casino industry is critical as wage decommodification is the main mechanism through which unions combat income inequality. The focus of this article is an analysis of a union’s attempt to decommodify wage entitlements in a casino. Decommodification is broadly defined as taking wages out of market competition and basing wage setting on political forms of negotiation (Esping-Andersen, 1990).

A case study of Windsor, Ontario—the automotive capital of Canada and the first city to host a resort casino outside of Atlantic City and Las Vegas—is used. Like automotive workers in Windsor, Casino Windsor[1] workers are unionized by the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW).[2] The CAW has a history of bargaining successfully to decommodify the wage rates of the Big Three (Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors) automotive assembly workers (Gindin, 1995). When organizing and bargaining on behalf of casino workers, the CAW attempted to frame wages as a share of profits in Ontario’s first casino, Casino Windsor. The CAW Local 444 brought, as one union leader termed it, an “industrial mindset” to the casino and casino membership. This equalled framing wages as a share of profits rather than as a response to a competitive labour market. The union attempted to transpose an “industrial mindset” or a surplus mentality into the casino and its casino membership to decommodify wage entitlements. In fact, the CAW promised its membership and demanded from the employer decommodified “auto wages.”

This “mindset” regarding wage determination drew on the potential of attaining Golden Age wage gains for the casino membership based on a labour-capital compromise of decommodified wages (Esping-Andersen, 1990). The CAW leadership assumed that the post-WWII managerial-labour relationship, entitling workers to a share of the profits they generate for their employer, could be brought into the new casino industry in Ontario (Kotz, 2007).[3] The expectation that casino workers would enjoy wages like automotive assembly workers rested on the assumption that union representatives could transplant these specific set of labour relations protocols, founded in political struggle, to the “brand new” (read: not to be compared to other service sector work) gaming industry in Ontario. In fact, the CAW used the newness of the casino industry as a lynchpin to justify wage decommodification, treating casino jobs as separate from the low and market-oriented wages of service work. These findings show that, during the unionization drive (1994-1995) and the first collective agreement negotiations (1995), casino workers adopted a discourse that they deserved the profits they created for the casino. Indeed, Casino Windsor workers did have the potential of ideologically becoming the new automotive workers of the service sector.

By 2014-2015, casino workers understood their wages relative to the human capital they offered.[4] As a counterpoint, these findings demonstrate that automotive workers—and the Casino Windsor membership’s CAW brothers and sisters—continue to stress their entitlement to a proportion of the profits they create for the employer.[5] Union representatives and the casino membership now view the CAW’s attempt to bring an industrial mindset into the casino as a mistake, naturalizing the link between decommodified wages in automotive manufacturing and the market-oriented wage entitlements of the service sector. Two factors explain why the CAW’s efforts failed: 1- the failure of the New Democratic Party of Ontario (NDP) to support the CAW (instead, the NDP worked against the CAW); and 2- lower union density in the service sector. Utilizing 91 interviews with Windsor stakeholders (20), automotive workers (43), and casino workers (28), an examination of the local newspaper from 1994-2014, and descriptive statistics, these findings demonstrate how the CAW failed in decommodifying wage entitlements at Casino Windsor. This was not due to some inherent nature of service work, but because of the political and institutional environment, which squashed an alternative model of wage entitlements.

Unionization, Decommodification, and the Rise of the Service Sector

With the rising prominence of service sector employment and the loss of ‘good jobs’ that manufacturing-centred regions once provided, the labour market has become increasingly segmented in terms of the rewards received between high- and low-skilled workers (Brown, Eichengreen, and Reich, 2010). The difference between the rewards received by low-skilled manufacturing workers compared to low-skilled service workers is largely attributable to differences in sectoral union density (ChangHwan and Sakamoto, 2010; Foster, 2003; Guschanski and Özlem, 2016; Waddoups and Eade, 2013). Rising income inequality, in large part, is due to the dismantling of institutions, like unions, that formerly insulated a large proportion of workers from direct engagement with market forces as the immediate wage-setting mechanism. Put simply, unions help decommodify remuneration.

Within the scholarly literature, there is discussion on whether unions can be characterized as decommodifying labour when engaged in collective bargaining. Unions do interfere with the mechanisms of the capitalist labour market, replace individual bargaining with collective bargaining, and work to lessen the commodification of labour (Hyman, 2007). From a Marxist perspective, however, unions function to negotiate the price of the labour commodity but do not decommodify labour through collective bargaining (Linn, 2017). Broadly, decommodification is a process whereby a person can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market—labour, in a capitalist system, therefore cannot be fully decommodified. Organizing and acting collectively does not eliminate the essential status of labour as a commodity under capitalism since workers rely on the sale of their labour power to survive (Barbash, 1991; Streeck, 2005). In this article, however, the term “decommodification” refers specifically to taking wages out of market competition and speaks to a union’s ability to decommodify workers’ wage rates—ideologically and materially—rather than labour itself.

In advanced industrialized countries, there has been a rise in service sector employment and declining employment in the highly unionized manufacturing sector. There is a robust literature addressing what constitutes barriers—and the magnitude of their importance—to unionizing the mostly union-free service sector comprised of low-skilled and low-wage workers. Explanations surrounding the failure of unions to establish themselves in the service sector can be broken down into five broad areas. First, a major barrier to unionizing the service sector is union identity. A union that remains a “prisoner of [their] own history” will be unable to successfully unionize other sectors and will be caught in a path dependency of past identities (Lévesque and Murray, 2010: 344). Unions must challenge their values and traditions to reflect the workplaces of the service sector in order to successfully unionize the service sector (Frege and Kelly, 2003). Second, a central barrier to unionizing the service sector is employer opposition to unionization. This opposition, in combination with the ineffectiveness of labour laws to protect and enforce the right to unionize, may prevent unions from transposing work regulation and collective bargaining similar to the manufacturing sector (Bronfenbrenner, 1997; 2009). Third, some posit that the low-skilled service sector represents a “non-union zone,” where unionization is difficult since these workplaces tend to be small in size, dispersed, and characterized by hostile employers. Indeed, in advanced industrial economies, the union zone (i.e. industry and manufacturing) is shrinking and the non-union zone is growing (Haiven, 2003). Fourth, the removal of economic barriers (i.e. increasing the mobility of capital) and increasing competition explains part of the difficulty of unionizing the service sector (Peters, 2008). Lastly, some emphasize the importance of local union power as explaining the successes and failures of unionization, whereby unions ought to work on their resources and capacities to better ensure their success (Lévesque and Murray, 2003; 2010).

The Service Sector: Casino Jobs as an Exception to the Rule?

Service work represents the ‘new’ economy of non-unionized, low-wage, and non-benefited work; yet, the trend, especially in hotel-casino resorts, is for workers to be represented by powerful Locals from the United Automotive Workers to UNITE HERE (Benz, 2004; Greenhouse, 2003; Kim, Moire, and Argyres, 2009; Meyerson, 2003; Prokos, 2006; Waddoups and Eade, 2013). As states look for non-tax based ways to raise revenue and as competition increases between neighbouring states and countries over capturing and recapturing gambling dollars, casinos have spread across the US and Canada along with efforts to unionize these large workplaces. With the increasing unionization rate in this growing industry, the ability to reduce the commodification of casino work is increasingly possible (Waddoups, 1999; 2000). While this represents a ‘new frontier’ of unionization across North America, there has been no research to date as to whether and how unions have been successful—ideologically and materially—in decommodifying the labour of casino workers.

The research, which has examined casino work, suggests that casino workers are mobile, transient, and adopt a ‘postindustrial’ ideology of individualism and entrepreneurialism. For instance, Taft (2016) finds that casino workers embody the new economy (i.e. postindustrial service economy) by embracing an entrepreneurial ethic and individualist mantra. Nonetheless, the research is sparse and tends to focus on non-union casinos and on dealers (who tend not to be unionized, even in unionized casinos) (Sallaz, 2002; Taft, 2016). The focus on non-union casinos and non-union workers contrasts with the wider unionization trend in the North American casino industry. In addition, studies addressing casino workers tend to examine core gambling locations in the US (i.e. Las Vegas and Atlantic City) (Mutari and Figart, 2015; Sallaz, 2002).[6] These areas have longstanding histories with casinos and the service sector. As a result, such cases can tell us little of what casinos mean for workers when used in more peripheral locations—where casinos are increasingly being placed—as a tool to diversify and/or transition cities from manufacturing to the service sector.

Methodology

Focusing on the automotive capital of Canada—Windsor, Ontario—the author is particularly interested in how the casino was framed as a tool to transition a struggling auto manufacturing city from industrial to postindustrial and what this meant for workers and labour unions in the city. With Casino Windsor opening in 1994, would the CAW—with much political currency and strength in Ontario’s automotive industry in the 1990s—be able to decommodify the labour of its Casino Windsor membership? In this expanding industry, this effort could challenge the connection between the service sector and low wages. The analysis offered is based on 91 semi-structured interviews, the local news media, and descriptive statistics.

From September 2014 to April 2015, the author interviewed local stakeholders and auto and casino workers. Interviews lasted from one to three hours. In referencing interview excerpts, pseudonyms are used. Twenty Windsor stakeholders from business, politics, and labour were questioned—all of whom had some ‘stake’ in the casino at various points in time—on the labour relations at Casino Windsor throughout the years. While there was a set of primary questions, interview guides were specifically crafted for the individual. These stakeholders were obtained by calling and/or emailing their respective offices and requesting interviews. Interviews were conducted at their place of work or at a coffee shop.

The purposive sample of unionized casino and auto workers offers a glimpse into the differences between how casino and auto workers understand wage entitlements. A large majority of interviews were conducted one-on-one. A small portion of the interviews, however, were done with spouses/partners who also worked at the casino or auto plant. Auto and casino workers were also questioned on their personal and employment histories and their thoughts about their wages and wage entitlements more generally.

To recruit auto workers, the author stood outside the plant gates during the day to afternoon shift change at the Chrysler Windsor Assembly Plant and the Ford Engine Plant, requesting workers’ participation as they either left or were coming into work. Of the 131 phone numbers obtained and contacted, a total of 43 auto worker interviews were completed. The majority of interviews were conducted at coffee shops throughout the city.

Recruiting casino workers was more difficult. Mandated by Casino Windsor, workers are banned from speaking with researchers regarding Casino Windsor. Since this was not publicly available information, the author was unaware of this when entering the field and began the recruitment process by placing approximately 110 flyers on the cars of casino workers in the casino’s parking garage. Not receiving a single call, this recruitment failure was discussed with a relative of the author in Windsor. She informed the author of a friend who was a casino worker who lived nearby, suggesting that she be approached at her home. Going to this woman’s home, the author asked if she would be willing to participate with full confidentiality. She quickly declined, explaining that she could not risk losing her job. Casino workers were inaccessible through direct recruitment due to fear of termination. Access was then requested through the casino’s Human Resource department, which was denied. Reaching out to the union representing the casino workers—CAW Local 444—the author then attended a union hall meeting where members were introduced to the author. At that meeting, the union president assured members of confidentiality, enabling the author to obtain a sample of 28 casino workers.[7]

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Using MAXQDA 12 software, an abductive approach to analyze the data was used. This employs rigorous data analysis against the backdrop of theoretical expertise in various literatures that address the expansion of casino gambling. Through revisiting and defamiliarization, new hypotheses and theories are created based on surprising or anomalous empirical findings (Timmermans and Tavory, 2012). What was striking in all interviews—from Windsor stakeholders to casino and auto workers—was the emphasis on how casino workers were supposed to be paid “auto wages.” This unexpected finding led the author to a detailed examination of wage decommodification in relation to the casino industry.

Finally, the local newspaper, the Windsor Star, was surveyed between the years 1994-2014. This timeframe allows for an examination of the unionization drive and the seven collective bargaining rounds—1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2008, 2011, and 2014—which captures the ‘ideological debate’ waged over what wages casino workers deserve. An examination of the ‘official’ narrative being produced within the city in real time offers a backdrop to the struggle over wage entitlements that was engaged in between the CAW, Windsor Casino Ltd., and the Ontario provincial government. Below, the historical pretext and narrative under which a casino was brought to Windsor is laid out.

Casino Jobs: From Public to Public-Private

Windsor stakeholders—business, labour, and political leaders—initially proposed to the Windsor community a casino which would be owned and operated by the provincial government. Under the aegis that these would be public-sector employees, Windsor stakeholders legitimized the casino to the community based on the claim that the casino would create good paying jobs for a city experiencing economic difficulties. Like other public-sector employees in Ontario, this workplace would likely be unionized. Casino Windsor would be a no-tipping environment where casino employees could expect an average annual income of $41,500 CAD in 1992 ($61,980.52 CAD in 2015 dollars).

The provincial government later decided, however, that the casino would be operated by a public-private partnership between the provincial government and a private consortium. The province would own the building through a new branch of the provincial government called the Ontario Casino Corporation, and the private Nevada group, comprised of Circus Circus, Caesars Entertainment, and Hilton Hotels—under the title of Windsor Casino Ltd.—would operate the venue. Opening on May 17, 1994, the workforce at Casino Windsor were employees (some now dependent on tips) of a Nevada consortium rather than the provincial government.

Windsor Casino Ltd. offered wages—between $7-12 an hour (Cross, 1994d)—to its employees that did not fulfill the initial expectation of the casino providing ‘good jobs.’ The Windsor Star (Vander Doelen, 1994) reported, “the new hirees are fuming about ‘minimum wage jobs’ [and are] complaining to politicians and the [Windsor] Star that the company has offered them $7 per hour instead of the $17 per hour plus benefits they expected.” This discrepancy acted as a catalyst for the rapid signing of union cards during the unionization drive, which began in May 1994. Three unions competed for the Casino Windsor membership: the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union (HERE), the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU), and the CAW (Cross, 1994b).

The Expectation of Auto Worker Wages

The CAW used their collective bargaining successes with the Big Three (Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors) and legacy within Windsor’s automotive industry to persuade Casino Windsor employees to choose their representation (Cross, 1994a). CAW leaders suggested that they would bring their successes from the auto industry to the casino. Undergirding this promise was the proposition that wages would not be determined by market forces but based on a decommodified logic of wage entitlements. CAW union leaders argued that casino workers ought to be entitled to a proportion of the profits they create for their employer. The Windsor Star (Cross, 1994b) reported on a CAW organizer saying:

The casino’s making good money, record profits, and without the input from the workers that wouldn’t be possible […] the lucrative wages and benefits of auto workers might be used as a pattern for casino workers. If the casino industry generates the same kind of profits (as the auto industry), there’s no reason they can’t enjoy the same wages and benefits.

The CAW won the unionization vote to represent Casino Windsor workers on September 18, 1994 with 80 percent support. The CAW leadership continued to cultivate an expectation of auto worker wages based on labour’s entitlement to a share of the employer’s profits. Before beginning negotiations for the first collective agreement, the Windsor Star (Cross, 1994c) reported:

Lewenza [president of Local 444] was already suggesting that casino workers could end up with wages [$22 an hour], benefits, and work rules comparable to those of autoworkers. […] In any industry that makes big profits—be it the car industry or the casino industry—workers are entitled to ask for a share of those profits, Lewenza said. […] ‘the sky’s the limit,’ for worker wages, Lewenza said.

Reinforcing the idea that the CAW would be able to provide high wages in sectors outside of the automotive industry, the Windsor Star reported the then-CAW national president Buzz Hargrove as saying that there’s “no expertise the CAW lacks in representing working people. There’s nothing magical about experience in a given sector” (Cross, 1993).

The membership at Casino Windsor were also buying-in to framing wages as a share of surplus. A casino worker wrote in a Windsor Star (Subity, 1995) op-ed:

The casino has been profitable for the Las Vegas proprietors, the government of Ontario, and the businesses of Windsor. Why is it that the only ones being dealt out of the profits will be those most responsible for the casino’s success, its employees?

Casino workers also saw themselves as separate from other low-wage service workers. For instance, the Windsor Star (Cross, 1994c) reported, “Cage cashier Shirley Egan believes her job warrants at least $15 an hour. ‘I mean, they’re making that at [the grocery store], and I have a heck of a lot of responsibility.’” Despite this initial adoption of a share of surplus mentality, these findings show how the CAW failed to bring an industrial mindset to the casino based on interviews with auto and casino workers in 2014-2015.

Auto Workers’ vs. Casino Workers’ Framing of Wage Entitlements

Like the discourse of union leaders during the casino’s unionization drive and negotiation of the first collective agreement, during the 2014-2015 interviews, auto workers maintain a decommodified vision of wage entitlements. Automotive workers argue that wages should reflect the profits that workers create for the employer. For instance, Dom, an automotive worker, reflects on his wage, saying, “The company succeeded because of its workers, they are the ones that make the company’s profit.” Another auto worker, Victor, contends, “They are making a billion dollars because we are building a decent product […] but if we are making a billion dollars, why shouldn’t we get a raise in the next contract?” (Italics added). Using “we,” the profits made by the employer are indivisible from the employee’s labour.

Despite being part of the same union/Local as auto workers, casino workers have difficulty seeing their wages being determined by anything beyond the market. This contrasts with union representatives’ and casino workers’ discourse used in the initial stages of the casino. For instance, Carl comments on his shift in perspective over the years:

For the work that I do? $18 and a half an hour. 10 years ago, I would probably say, ‘They should pay me $5 more an hour,’ but most people don’t make $18 and a half an hour in a kitchen. Like I run dishes back and forth between a kitchen or I wash them so…

Comparing himself to others in the service sector, Carl experienced a declining sense of “entitlement” for a higher wage. Relatedly, Karen suggests that fellow casino workers ought to be “intelligent enough” to compare their wages to those in their sector. Unlike auto workers, casino workers assess their wages based on their and their coworkers’ human capital. Given the education and skills needed in the workplace, casino workers see their wages as “fair.” For instance, Rick comments:

We make good money for what we do. We play cards, let’s be honest. Anybody who wanted to do that job, could do that job. It is not like that is a skillset that is unique or something. That you need ample amounts of training to do. It is like really, anybody can do that job.

Casino workers’ framing of wage entitlements is in stark contrast to automotive workers who often discuss the product they create and the profit it produces. Casino workers do not see themselves as producing a product. Instead, casino workers see themselves as producing an experience for patrons. For instance, Dan discusses the distinction between producing a product and an experience:

Because you are producing something, you are producing something that people can use or are going to use. We don’t produce anything here. All we do is take money and give people that... you give me $5 and I let you think that you are a very special person and that this is where you want to be with the glitz and glamour and that goes along with being in a casino. […] That is all that is, we don’t think about how much money casinos make and produce nothing.

These findings reflect Livingstone and Scholtz’s (2016) argument that workers producing an experience rather than a visible good have difficulty seeing the surplus they create. In contrast, workforces—such as those existing in the automotive assembly industry—that create a tangible product for profit are more able to see the surplus they create and move beyond a wage-setting framework which is solely market-determined.

Nevertheless, many casino workers are also in a position to directly see the profits, or at least the large sums of money, passing through the casino. Based on this logic, casino workers having a share of profits mentality is plausible. For example, Jessica states:

I’ve counted out $25,000 in cash, $50,000 in cash. You don’t even think about it. One player, he is allowed to bet the max, a $50,000 limit. And I think to myself every now and then—it doesn’t bother me—but I think, ‘Your one hand, the two seconds that it took… It’s more than I make in a year.’ And then I am like ‘Wow, it must be nice to be in your shoes’ [laughs].

Here, Jessica focuses on the disposable income of the patron rather than the profits being generated for the casino. As a result of understanding wages as based on the skillset they offer, combined with comparing their wages to others in the service sector while not having the language to ground how the experience they produce creates a surplus, casino workers express gratitude for their wages and having employment. For instance, Kate says, “The income is good, it is better than other people in bars and restaurants, so we are grateful for our income.”

Casino workers frame their wage-setting arrangements quite differently than auto workers, despite being part of the same union—and many the same Local—and becoming members during a similar timeframe. The industrial mindset CAW union representatives attempted to bring to the casino is in stark contrast to the casino membership’s contemporary framing of wage entitlements based on human capital and intra-service sector comparisons. Below, from the 2014-2015 interviews, evidence is provided of union representatives’ and casino workers’ post-hoc re-evaluation of the attempt to frame wages at Casino Windsor based on a share of surplus approach.

Unrealistic Expectations

‘‘I am not an auto worker […] we are not auto workers.’’ – Betty, casino worker

Reflecting on the demands made and the expectations cultivated, union representatives—some of whom were involved in creating those expectations 20 years earlier—and casino workers concede that attempting to bring an industrial mindset to the casino was a mistake. Union representatives and casino workers have naturalized the disconnect between casino jobs, and service sector jobs more broadly, and wage decommodification. In fact, a union official cites “the industrial mindset” as “getting in the way” and creating an unrealistic expectation for service workers. Tom, a former CAW union leader, states:

We took our industrial mentality to this new industry, and that wasn’t… after the [1995] strike[8] […] we knew what we couldn’t achieve in this industry. And we couldn’t treat it like a GM, Ford, or Chrysler, or any of our auto parts companies. We had to treat it based on the occupations within that large employment workplace. […] Our industrial mind delayed us getting a collective agreement for a little while. (Italics added)

Union leaders suggest that intra-service sector wage comparisons were more appropriate. Another union leader, Denis, also echoes this sentiment:

You got to go back to the membership and say, ‘You know what, the $19 we talked about wasn’t really realistic, because that’s more automotive and you’re more here.’ So, we’ve learned that we need to put ourselves into their [employer’s] shoes, be more empathetic about how they fit into their sector of the economy.

A top executive at Casino Windsor also comments on these expectations, suggesting that there was an attempt to put “an auto-plant mentality” into the casino. He states, “I would say that they’re totally different industries. I think trying to put an auto-plant mentality in a casino is difficult, and I think that’s what the early stuff was [labour relations conflict]. Now we are all much better at it.” Union leadership and casino membership have naturalized the link between decommodified wages and automotive manufacturing and commodified wages and casino/service work. Below, the political and institutional forces which led to this naturalization are elucidated.

Political Constraints: The New Democratic Party of Ontario

Negotiation of the first collective agreement began with a massive gap between the union’s wage demands and Windsor Casino Ltd.’s offer. The union demanded a 100 percent wage increase in some classifications and double digit increases in others while Windsor Casino Ltd. offered a 6 percent wage increase over 3 years. Despite the gulf between wage demands and offers, the CAW Local 444 president commented in the Windsor Star (Cross, 1995b) on the minuteness of such differences relative to the revenue generated by the casino:

The difference between what the union wants and what the company offers is about $42 million over three years, a sum the casino can make up in 30 days of operation, Lewenza argued. […] Casino officials say that the union demands are outrageous and are unjustified for a business that fits itself in with a hospitality sector that typically pays lower wages than factories.

The union—seeking to decommodify wages—argued that casino workers, like auto, deserved to reap the rewards of the profits they help create. In contrast, the employer argued that wages must be comparable to other casinos—to compete with the potential of Detroit building casinos—and to the service sector. For instance, the Windsor Star’s Cross (1995d) reported:

The casino had wanted to keep wages down to hospitality-industry levels in order to be competitive with future casinos. The CAW rejected that argument outright, asserting this was a brand new Ontario industry making wads of money, and that workers deserved a bigger share of the revenue. This ‘philosophical difference’ kept the sides so far apart. […] The union called for provincial intervention and went so far as to call for the ouster of these American casino operators.

With the union’s final demand of a 38 percent wage increase and Windsor Casino Ltd. offering 11 percent over three years, there was overwhelming strike support from the Casino Windsor membership. With over 60 percent of the casino membership in attendance and a vote of 1,111 to 22 in favour of giving their bargaining committee strike authorization, casino workers went on strike on March 9, 1995 (Vander Doelen and Crawford, 1995).

NDP Provincial Government: Smothering Decommodification

A 27-day strike ensued and the NDP provincial government declared that they would not intervene during negotiations and the strike. The announcement of this ‘hands-off’ policy was in spite of casino labour costs being almost completely absorbed by the provincial government instead of the employer. As reported in the Windsor Star (Cross, 1995a):

Ontario Casino Corporation spokesman Bill Gillies said the government would be affected most by any increase in labour costs. ‘It would be safe to say that for every $1 increase in cost, 90 cents of that would be less revenue for the province,’ he said. But Gillies said the province has no plans to intervene in the talks. ‘This is between a private employer and a union and that’s where it should be.’

With the provincial NDP reiterating its non-engagement, the CAW pushed back and highlighted the promises made by the provincial government of the casino providing well-paid work in a “brand new industry” (Cross, 1995b):

The provincial government, which owns the casino and gets a significant cut of revenues and profits (rumoured at close to $1 million a day), has maintained it is not involved in the negotiations. Ontario Casino Corporation spokesman Bill Gillies reiterated the government position again today, that the negotiations are between the union and the casino company. […] The union has maintained from the start that this is a brand new industry that’s making big money, money which should be more equally shared with the employees. They harken back to NDP government promises when the casino was announced, that workers would be well paid. […] ‘The province is doing well, the corporation is doing well, the City of Windsor is doing well, developers and construction is doing well. Everyone seems to be doing well except the workers at the bottom of the totem pole,’ [Lewenza said].

The CAW leadership expected the NDP to provide support to the CAW during negotiations and the NDP publicly stepped aside. For instance, the Windsor Star (Sumi 1995) reported that the union expected the province to push Windsor Casino Ltd. back to the bargaining table when the employer broke off talks, “The union had hoped the Crown corporation could intervene and get the two sides back to the table, but [Crown] corporation directors met Thursday and decided against any government influence in the dispute, Gillies [Ontario Casino Corporation spokesman] said.” CAW union leader, Ken Lewenza, and the Windsor NDP MPP, Dave Cooke, who were both influential in bringing the casino to Windsor, are also reported as offering conflicting views on the position the provincial government ought to take in negotiations and the strike in the Windsor Star (Cross, 1995d):

‘They’re [the province] ignoring this whole unnecessary strike,’ Lewenza said. ‘They can say it’s the private sector, but this is the Ontario government. They can settle it with one phone call, but they won’t.’ On Monday, Windsor MPP Dave Cooke, a cabinet minister, reiterated what Premier Bob Rae said before: ‘It would serve no useful purpose for the government to intervene,’ Cooke said. ‘We’re not the employer.’ Although the CAW plans to ask its many Windsor-area members to write OCC [Ontario Casino Corporation] chairman Gil Bennett asking for some intervention, no change in the government’s position is expected.

The strike concluded with a ratified collective agreement—with 78 percent membership support—where workers would receive nearly a 25 percent wage increase over 3 years.[9] Upon ratification, Local 444’s leader expressed regret for creating too high expectations in casino workers, stating in the Windsor Star (Cross, 1995d), “‘Our sights were set very, very high, their sights were set very, very low,’ recounts CAW Local 444 president Ken Lewenza. Looking back, Lewenza wishes he hadn’t made such a daring statement [re: wages, sky’s the limit].”

With the first collective agreement, labour costs would rise 30-40 percent in the first year of the deal. As a result of the profit-sharing agreement between the Las Vegas consortium—Windsor Casino Ltd.—and the provincial government, the provincial government would absorb 95 percent of this extra cost. Despite the provincial government incurring the majority of the increased labour costs, representatives of the provincial government maintained that they played no role in the talks, yet stated that they remained “‘very, very interested observers’” (Cross, 1995d).

The provincial NDP government remaining out of negotiations ran counter to CAW expectations, which represents a large proportion of the Canadian labour movement—which has historically supported the NDP. The NDP positioning themselves as taking a ‘hands-off’ approach effectively amounted to intervening on the side of the employer, given the inherent power imbalance that exists between labour and capital. This also positions the provincial NDP government, the most ‘labour friendly’ of all, against other Canadian governments intervening to restrain employers (Logan, 1956; McBride, 1996; Pentland, 1979). In fact, the NDP tacitly intervened to lower the union’s expectations. Tom, the former casino union leader who was instrumental in negotiating the first collective agreement, suggests that, instead of taking a hands-off approach, the provincial government was active in lowering the union’s wage demands:

Our expectations were higher because there was an NDP government in power, and we thought the NDP would, behind the scenes, provide the support to break some of those barriers down. But they didn’t. I mean, they took the position, and 25 years later, I believe it was the right position. They took the position, ‘Listen we invested heavily in Windsor, Ontario. We created hundreds and hundreds of jobs.’ […] So, we always thought that the New Democratic Party would eventually succumb to some of the pressure that we had at the bargaining table, but they didn’t. They weren’t as helpful as we thought they would be, and that’s also because our expectations were so high. […] The government took the position to treat the workers fairly, ‘but remember, we introduced this for revenue for the province of Ontario and for diversity in Windsor relative to job creation. And in those areas we succeeded so let’s not blow our heads off basically. Don’t compare it to Chrysler, Ford, or GM, cause that’s not the league we are in.’ So that was the philosophical battle.

Tom also comments on the NDP’s role in managing the amount of “progress” the CAW and its casino membership achieved since this collective agreement could set a precedent for future Ontario casinos. He states:

But it was very very difficult because we had no contract like it in Canada. This was the model. And we knew, being a pilot program at Casino Windsor, that if Casino Windsor expanded, that our contract would apply to the new casinos. There was a lot of pressure on the province to make sure that workers didn’t exhaust all of the success that came out of the casino. (Italics added)

A Windsor NDP representative, John, who was involved in the development of Casino Windsor and present during the first round of collective agreement negotiations, also states, “I think at first people initially thought that we’d be able to pay [Casino Windsor workers] the same rate as an auto worker, which isn’t the case in the service sector.”

Ultimately, the provincial government did not provide the support the CAW leadership expected. Instead, the provincial government, like the Las Vegas consortium, was concerned about labour costs and setting a precedent for other casinos. Indeed, the “philosophical debate” of how much casino work was worth—and whether it would be classified as within the low-wage service sector or seen as a “brand new” category of work—was not simply waged between the employer and the union; the provincial government also took an active role in not allowing a share of surplus model to be brought into the casino.

After the first collective agreement, union representatives’ framing of casino worker wages changed in the Windsor Star during subsequent rounds of collective bargaining. When examining the Windsor Star’s reports on the following six collective bargaining rounds—1998, 2001, 2004, 2008, 2011, and 2014—the ‘ideological debate’ of whether casino workers are entitled to auto-like wages or a proportion of their employer’s profits was absent. Union leaders no longer publicly announced that casino workers ought to be paid like auto workers or deserve part of their employer’s profits.

Ultimately, the NDP was pivotal in suppressing the CAW’s agenda of offering an alternative mode of framing wage entitlements in the service sector. Put plainly, the Ontario NDP did not provide this support and, in fact, was crucial in pushing the managerial interest in framing wages with reference to the low-wage service sector versus the decommodified wage entitlements of automotive manufacturing. Working-class interests—i.e. decommodifying wages—were not supported by the Ontario NDP when in power (McBride, 1996). With pressure from the NDP, the CAW leadership reined in their rhetoric. Therefore, given the union’s primary objective to limit market competition surrounding wages, the union leadership actually undermined the potential of building a consciousness around this cause in its casino membership; a worker consciousness that allows their organization to exist in the first place (Brenner, 1985: 37). When attempting and failing to bring an “industrial mindset” into the casino industry, it is clear that CAW representatives took for granted the specific labour-managerial relations established in the post-war decades and the decommodified wage scales found in automotive assembly that were born out of political struggle. The next section demonstrates how the institutional setting of low union density within the service sector further constrained the union leadership’s and casino membership’s ability to frame wage entitlements outside the market.

Institutional Constraints: Sectoral Union Density

The CAW has been able to retain high union density in automotive assembly. For instance, while falling from a high of 67.5 percent in 1982, from 1990-1995, union density in “Transportation equipment manufacturing” in Canada remained steady at approximately 42 percent (Figure 1). From 1997-2015, “Manufacturing” union density ranges from 23.5-33.3 percent (Figure 2). More specifically, from 1997-2015, the unionization rate of “Motor vehicle assemblers, inspectors, and testers” was between 52.4-73.2 percent (Figure 3). This has contributed to union representatives’ and auto workers’ ability to establish alternate benchmarks for wage rates—such as company profits—since their wages have been largely taken out of competition.[10] Indeed, automotive workers’ industrial mindset, which reflects a decommodified wage scale, is reinforced by high union density and the CAW’s legacy of decommodifying automotive manufacturing wages.

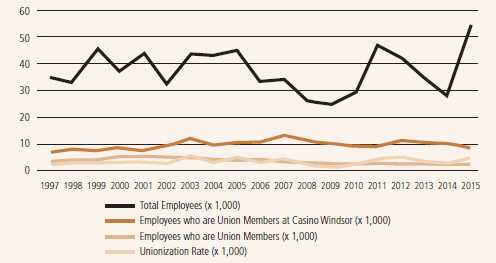

In contrast, Casino Windsor was entering a service sector that had much weaker union density. For instance, in Canada, up until 1986, “Accommodation, food, and beverage” and “Other services (except public administration)” display zero union density, while from 1990-1995 union density ranges from 8.6-9.1 percent in “Accommodation, food, and beverage” and from 11.6-15.9 percent in “Other services (except public administration)” (Figure 1). From 1997-2015, the unionization rate in “Accommodation and food services” ranges from 5.8-7.9 percent and “Other services (except public administration)” ranges from 8.6-9.7 percent (Figure 2). Looking at “Casino occupations” from 1997-2015, the unionization rate ranged from 24.8-54.1 percent. This is relatively high, especially compared to service industries captured in Figure 2. Nonetheless, when examining the total number of casino employees who are union members while taking into account the number of unionized employees at Casino Windsor, the Casino Windsor unionized workforce comprises a significant proportion of the total count of unionized casino employees. Therefore, while the union density in this particular occupation—casino work—on aggregate is relatively high, it is accompanied with the caveat that union density in “Casino occupations” is significantly comprised of unionized Casino Windsor employees (Figure 4). Casino Windsor workers’ frame of reference became embedded into the low union density service sector instead of constructing a high-density casino island. An effect of this is casino workers associating casino jobs with the larger (non-union) service sector labour market, rather than as part of a group of higher-wage unionized jobs (including casinos and automotive manufacturing).

Figure 1

Union Density by Industry, 1978-1995, Canada

Labor Force Survey, December estimates.

Union density is the proportion of unionized workers derived from Corporations and Labor Unions Returns Act (CALURA) CANSIM table 2790026, component unionized workers, to the number of employees derived from the Labor Force Survey (LFS) CANSIM, table 2790026, component employees.

Figure 2

Union Rate by Industry, 1997-2015, Canada

Unionization rate: Employees who are members of a union as a proportion of all employees.

Figure 3

Motor Vehicule Assemblers, Inspectors, and Testers, 1997-2015, Canada

Figure 4

Casino Occupations, 1997-2015, Canada

Conclusion

Casinos have become an increasingly popular strategy to create ‘good’ service jobs in regions losing their primary industries, like manufacturing. Through relatively higher unionization rates, casino employment provides a counterexample to the connection between low-skill service work and low-wages (Waddoups, 2002). Whether and how unions are successful in decommodifying wage rates in this expanding service industry is relevant since decommodification is the main mechanism through which unions combat income inequality.

Despite the spread of casinos, research that examines casino work is sparse. The research that does exist finds that casino workers are mobile, transient, and adopt a ‘postindustrial’ ideology of individualism and entrepreneurialism, suggesting that casino workers adopt a commodified understanding of their labour (Sallaz, 2002; Taft, 2016). These findings, however, are based on workers at non-unionized casinos and on dealers (who tend not to be unionized, even in unionized casinos). This contrasts with the unionization trend in the wider North American casino industry. In addition, these studies examine core gambling locations in the US (i.e. Las Vegas and Atlantic City) (Mutari and Figart, 2015; Sallaz, 2002). Such cases can tell us little of whether the unionization of casinos represents the decommodification of labour in contexts where they are increasingly being used (i.e. peripheral and deindustrializing areas). Indeed, do casinos represent the new factories of the service sector?

Casino Windsor workers—and members of CAW Local 444—initially expected and demanded “auto wages,” claiming that they deserved a proportion of the profits they created for their employer. Nonetheless, by 2014-2015, casino workers understood their wages by comparing them to those of low-wage service sector jobs, their skillset relative to supply and demand, and what they produce (or rather do not produce) (Livingstone and Scholtz, 2016). Auto workers, in contrast, continue to stress their (and other workers) entitlement to a proportion of the profits they create for the employer. Unlike the automotive workers, who enjoy a legacy of decommodified wages as a result of political struggle and high union density, the CAW leadership’s and casino membership’s attempt to frame wages outside the cash nexus was squashed by larger political and institutional forces. The CAW’s attempt to transplant the industrial mindset into the casino was unsuccessful.

Politically, these findings suggest that the (in)actions of the NDP provincial government (1990-1995) during the first round of collective bargaining at Casino Windsor substantially contributed to the CAW being unsuccessful with its campaign. The NDP squashed the CAW’s discourse of a “brand new industry” and their attempt to create a casino island—i.e. not comparing wage entitlements to other service work—based on decommodified wages. Instead, the CAW conceded that casino worker wages would be compared to the broader service sector. Casino work became part of the broader service sector, constraining the CAW’s ability to set alternative wage benchmarks. Casino work discursively becoming service work meant low sectoral union density made it further difficult for casino workers to see their wage entitlements beyond market forces. This contrasts with the CAW’s success in creating a decommodified auto worker island within a higher union density manufacturing sector.

Concerning barriers to successfully decommodifying wage entitlements in the service sector, these findings highlight the importance of government non-engagement/opposition and union identity in relation to the service sector as a “non-union zone” (Bronfenbrenner, 1997; 2009; Haiven, 2003; Lévesque and Murray, 2010). First, the NDP’s unwillingness to publicly intervene during negotiations of the first collective agreement and extinguishing the CAW’s surplus mentality discourse was a strong endorsement of labour commodification. Second, the union’s framing of casino work as outside of the service sector and as a brand new industry was an attempt to create a casino membership identity outside of the low-wage service sector. Union representatives also demanded auto worker wages, which drew on the historical successes of the CAW decommodifying wage rates. Indeed, the CAW attempted to mix a “brand new” identity with the legacy of the auto surplus mentality. CAW representatives, however, conceded to NDP discipline and retracted the pursuit of this identity. Now, since the Casino Windsor workers’ ethos has been structured on service sector labour market norms and identities—or the “non-union zone” of highly commodified labour and low union density—the CAW has been unable to ideologically and materially decommodify wage rates. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the CAW’s unionization of Casino Windsor has not been a complete failure as they have been able to gain representation and bargain agreements whereby its Casino Windsor membership is generally paid more than other workers in the low-skilled service sector. Yet, the CAW has been unable to transpose an industrial mindset or share of surplus mentality due to government opposition in combination with a failure to establish a share of surplus identity in its union representatives and membership. This has led to CAW representatives and the casino membership naturalizing the link between commodified wage rates, the service sector, and the casino industry.

These findings can be interpreted in light of literature on union renewal, which highlights the mismatch between industrial-age union culture and cultures which exist in new workplaces (Frege and Kelly, 2003). In the case of Casino Windsor, the CAW attempted to transpose an industrial identity in an effort to set Casino Windsor workers apart from the broader low-wage service sector. Upon analysis and reflection, it may have been more strategic for the CAW to attempt to discursively reframe the service sector more generally by pursuing a service sector surplus mentality. This would be based on creating a union culture and discourse which identified the profits service sector workers create and the entitlement of service workers to these profits.

This study’s findings demonstrate that there is nothing inherent in casino work—and service work, more generally—that necessitates that workers in these industries will receive—or believe they deserve to receive—commodified wages. Rather, these findings elucidate how larger political and institutional forces shape what such employees feel they deserve. It is clear that there was a struggle to make jobs in the casino industry the new auto jobs in Canada’s growing service sector. In this expanding industry, the success of the CAW’s effort could have had broader implications for challenging income inequality and the seemingly inherent connection between the service sector and highly commodified labour.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Casino Windsor was rebranded as Caesars Windsor in 2008. For simplicity, the author refers to the casino in Windsor as Casino Windsor throughout this article.

-

[2]

As of September 2013, the CAW and the Communications, Energy, and Paperworkers Union merged, creating the largest private sector union in Canada, Unifor. For the purposes of this paper, I refer to the union as the CAW since historically (and presently) this is how Windsor casino and auto workers and the broader community refer to it.

-

[3]

Canada’s post-war managerial-labour framework—PC 1003, the Rand Formula, and the Industrial Relations and Disputes Investigations Act—was a compromise whereby labour traded militancy for the right to organize and assented to Taylorism in return for a share of the resulting productivity increases (Fudge and Tucker, 2001; Wells, 1995). The UAW was pivotal in creating the labour-capital compromise characteristic of post-war labour relations, which had a dramatic impact on automotive manufacturing employment compensation in Canada (Benedict, 1985; Wells, 1995b).

-

[4]

Human capital is an individual’s education and training, which then influences rewards received in the labour market (Becker, 1994).

-

[5]

The casino and auto workers interviewed were hired and became members of the CAW—many within the same Local—during a similar period. Among the respondents, 32 of 43 automotive workers interviewed were hired at Chrysler (CAW Local 444) or Ford (CAW Local 200) from 1993-2000. Twenty-seven of the 28 casino workers interviewed were hired at Casino Windsor (CAW Local 444) from 1994-2000.

-

[6]

Taft (2016) investigates Pennsylvania, the second largest commercial casino state outside of Nevada.

-

[7]

Due to deep concerns over confidentiality related to the threat of employer dismissal, the author does not disclose the job classification of the casino worker participants.

-

[8]

In 1995, there was a 27-day strike, which centred on wages during the negotiation of the first collective agreement.

-

[9]

The Collective Agreement (1995-1998) resulted in wage increases of 17 to 34 percent over three years. Canadian Auto Workers Local 444 officials estimated that the average casino wage would go up about 25 percent, from $9.23 an hour to about $11.50 an hour (Rennie, 1995).

-

[10]

In recent years, the decommodification of wages in the automotive sector has slipped, particularly with the rise of two-tier wage scales and the erosion of defined benefit pension plans (Fowler, 2011; Owram, 2016).

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges financial support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada. The author would like to thank Dr. Elaine Weiner and Dr. Barry Eidlin for their comments on drafts of the manuscript. Finally, the author thanks the participants who made this study possible.

References

- Barbash, Jack (1991) “Industrial Relations Concepts in the USA.” Relations industrielles/ Industrial Relations, 46 (1), 91-119.

- Becker, Gary (1994) “Human Capital Revisited.” In Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education (3rd Edition). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 15-28.

- Benedict, Daniel (1985) “The 1984 GM Agreement in Canada: Significance and Consequences” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 40 (1), 27-47.

- Benz, Dorothee (2004) “Labour’s Ace in the Hole: Casino Organizing in Las Vegas.” New Political Science, 26 (4), 525-550.

- Brenner, Robert (1985) “The Paradox of Social Democracy: The American Case.” The Year Left, 1, 32-86.

- Brown, Clair, Barry Eichengreen, and Michael Reich,eds. (2010) Labour in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate (2009) “No Holds Barred: The Intensification of Employer Opposition to Organizing.” Briefing Paper No. 235, May 20, Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate (1997) “The Role of Union Strategies in NLRB Certification Elections.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 50 (2), 195-221.

- ChangHwan, Kim and Arthur Sakamoto (2010) “Assessing the Consequences of Declining Unionization and Public-Sector Employment: A Density-Function Decomposition of Rising Inequality from 1983 to 2005.” Work and Occupations, 37 (2), 119-161.

- Cross, Brian (1993) “CAW Has the Inside Track: Unions Compete for Plum of 2,500 New Workers.” The Windsor Star, December 7, B2.

- Cross, Brian (1994a) “Casinos Workers Urged to Join ‘Chrysler’s Local.’” The Windsor Star, June 11, A3.

- Cross, Brian (1994b) “Casino Workers Voting on CAW Bid.” The Windsor Star, September 15, A3.

- Cross, Brian (1994c) “Expect Raises, Casino Staff Told: Moon’s the Limit, CAW Vows.” The Windsor Star, September 19, A2.

- Cross, Brian (1994d) “Huge Profits to Figure in Talks.” The Windsor Star, November 22, A3.

- Cross, Brian (1994e) “Steep Wage Hikes Key to Casino Pact, CAW Warns.” The Windsor Star, December 17, A3.

- Cross, Brian (1995) “Casino Strike Looms, CAW Warns.” The Windsor Star, March 3, A3.

- Cross, Brian (1995b) “All Bets Are Off. Workers Strike: Company Cites Wage ‘Chasm.’” The Windsor Star, March 9, A1.

- Cross, Brian (1995c) “CAW Hopes that Pen Mightier than Sword.” The Windsor Star, March 21, A3.

- Cross, Brian (1995d) “High Stakes.” The Windsor Star, April 8, E1.

- Frege, Carola M. and John Kelly (2003) “Union Revitalization Strategies in Comparative Perspective.” European Journal of Industrial Relations, 9 (1), 7-24.

- Foster, Ann C. (2003) “Difference in Union and Non-Union Earnings in Blue-Collar and Service Occupations.” Bureau of Labour Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/cwc/differences-in-union-and-nonunion-earnings-in-blue-collar-and-service-occupations.pdf

- Fowler, Tim (2011) “Working for the Clampdown: How the Canadian State Exploits Economic Crises to Restrict Labour Freedoms.” Studies in Political Economy, 88, 77-96.

- Fudge, Judy and Eric Tucker (2001) Labour before the Law: The Regulation of Workers’ Collective Action in Canada, 1900-1948. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gindin, Sam (1995) The Canadian Auto Workers: The Birth and Transformation of a Union. Toronto: James Lorimer & Co.

- Guschanski, Alexander and Özlem Onaran (2016) “Why Did the Wage Share Fall? Industry Level Evidence from Austria.” Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft-WuG, 42 (4), 557-589.

- Haiven, Larry (2003) “The Union and the Non-Union Zone: A Framework for the Challenge to Unions to Organise.” Just Labour, 3, 64-74.

- Kim, Marlene, Susan Moir and Anneta Argyres (2009) “Gaming in Massachusetts: Can Casinos Bring ‘Good Jobs’ to the Commonwealth?” Labour Resource Center Publications, Paper 3.

- Kotz, David M. (2007) “The Capital-Labour Relation: Contemporary Character and Prospects for Change.” In The Second Forum of the World Association for Political Economy.

- Lévesque, Christian and Gregor Murray (2005) “Union Involvement in Workplace Change: A Comparative Study of Local Unions in Canada and Mexico.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43 (3), 489-514.

- Lévesque, Christian and Gregor Murray (2010) “Understanding Union Power: Resources and Capabilities for Renewing Union Capacity.” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 16 (3), 333-350.

- Linn, Spross (2017) “A Dilemma for the Welfare State: Managing the Cost for Shorter Working Hours, 1919-2002.” Labor History, 58 (1), 26-43.

- Livingstone, D. W. and Antonie Scholtz (2016) “Reconnecting Class and Production Relations in an Advanced Capitalist ‘Knowledge Economy’: Changing Class Structure and Class Consciousness.” Capital and Class, 40 (3), 469-493.

- McBride, Stephen (1996) “The Continuing Crisis of Social Democracy: Ontario’s Social Contract in Perspective.” Studies in Political Economy, 50 (1), 65-93.

- Mutari, Ellen and Deborah M. Figart (2015) Just One more Hand: Life in the Casino Economy. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Owram, Kristine (2016) “Ford Canada Workers Approve Labour Agreement, but Divisions Remain.” Financial Post, November 6, https://business.financialpost.com/transportation/ford-labour-deal

- Peters, John (2008) “Labour Market Deregulation and the Decline of Labour Power in North America and Western Europe.” Policy and Society, 27 (1), 83-98.

- Prokos, Anastasia H. (2006) “Employment and Labour Relations in Nevada.” In The Social Health of Nevada: Leading Indicators and Quality of Life in the Silver State, 1-30. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/social_health_nevada_reports/21

- Rennie, Gary (1995) “Casino Workers Ratify.” The Windsor Star, April 03, A1.

- Sallaz, Jeffrey J. (2002) “The House Rules: Autonomy and Interests among Service Workers in the Contemporary Casino Industry.” Work and Occupations, 29 (4), 394-427.

- Streeck, Wolfgang (2005) “The Sociology of Labor Markets and Trade Unions.” The Handbook of Economic Sociology, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 254-283.

- Subity, Pauline (1995) “Talking Point: Readers Speak Up on Strike.” The Windsor Star, March 14, A7.

- Sumi, Craig (1995) “Strictly Hands Off, Government Says.” The Windsor Star, March 10, A11.

- Taft, Chloe E. (2016) From Steel to Slots: Casino Capitalism in the Postindustrial City. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Timmermans, Stefan and Iddo Tavory (2012) “Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis.” Sociological Theory, 30 (3), 167-186.

- Vander Doelen, Chris (1994) “Deal Upsets Casino Dealers: They Say $7 an Hour Plus Tips Is Not Enough.” The Windsor Star, March 3, A1.

- Vander Doelen, Chris (1995) “Deep Differences Divide Sides.” The Windsor Star, March 10, A3.

- Vander Doelen, Chris and Blair Crawford (1995) “Casino Staff Back Strike by 98%.” The Windsor Star, March 6, A1.

- Waddaoups, Jeffrey C. (1999) “Union Wage Effects in Nevada’s Hotel and Casino Industry.” Industrial Relations, 38 (4), 577-583.

- Waddaoups, Jeffrey C. (2000) “Unions and Wages in Nevada’s Hotel-Casino Industry.” Journal of Labour Research, 21 (2), 345-361.

- Waddaoups, Jeffrey C. (2002) “Wages in Las Vegas and Reno: How Much Difference Do Unions Make in the Hotel, Gaming, and Recreation Industry.” Gaming Research and Review Journal, 6 (1), 7-22.

- Waddoups, Jeffrey C. and Vince Eade (2013) “Hotels and Casinos: Collective Bargaining during a Decade of Instability.” In P. Clark and A. Frost (Eds.), Collective Bargaining under Duress: Case Studies of Major U.S. Industries, Labour and Employment Relations Association, p. 81-117.

- Wells, Don M. (1995) “The Impact of the Postwar Compromise on Canadian Unionism: The Formation of an Auto Worker Local in the 1950s.” Labour/Le Travail, 36, 147-173.

- Wells, Don M. (1995b) “Origins of Canada’s Wagner Model of Industrial Relations: The United Auto Workers in Canada and the Suppression of ‘Rank and file’ Unionism, 1936-1953.” Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie, 20 (2), 193-225.

List of figures

Figure 1

Union Density by Industry, 1978-1995, Canada

Labor Force Survey, December estimates.

Union density is the proportion of unionized workers derived from Corporations and Labor Unions Returns Act (CALURA) CANSIM table 2790026, component unionized workers, to the number of employees derived from the Labor Force Survey (LFS) CANSIM, table 2790026, component employees.

Figure 2

Union Rate by Industry, 1997-2015, Canada

Figure 3

Motor Vehicule Assemblers, Inspectors, and Testers, 1997-2015, Canada

Figure 4

Casino Occupations, 1997-2015, Canada

10.7202/050646ar

10.7202/050646ar