Abstracts

Summary

This article examines the relationship between gender, forms of employment and dimensions of precarious employment in Canada, using data from the Labour Force Survey and the General Social Survey. Full-time permanent wage work decreased for both women and men between 1989 and 2001, but women remain more likely to be employed in part-time and temporary wage work as compared to men. Layering forms of wage work with indicators of regulatory protection, control and income results in a continuum with full-time permanent employees as the least precarious followed by full-time temporary, part-time permanent and then part-time temporary employees as the most precarious. The continuum is gendered through both inequalities between full-time permanent women and men and convergence in precariousness among part-time and temporary women and men. These findings reflect a feminization of employment norms characterized by both continuity and change in the social relations of gender.

Résumé

Cet article étudie la relation entre le sexe, les types d’emploi et l’ampleur de la précarité d’emploi au Canada. L’emploi précaire se définit comme étant des formes d’emploi comportant des contrats d’emploi atypique, des avantages sociaux restreints, peu de droits en vertu de la loi, de l’insécurité, de l’ancienneté faible, des conditions de travail médiocres et un risque élevé au plan de la santé physique. En faisant appel à des données d’enquête pour illustrer la « féminisation des normes du travail » (Vosko 2000), cet essai évalue le caractère sexué de l’augmentation de l’emploi précaire au sein de la main-d’oeuvre canadienne.

L’article comprend quatre parties : la première passe en revue les termes retenus pour décrire et expliquer les changements survenus au plan de la relation d’emploi. Au Canada, il existe une tendance à l’effet de grouper ensemble un spectre assez large de formes d’emploi et d’aménagements du travail en une seule et même catégorie, à savoir « le travail atypique » (Conseil économique du Canada 1990 ; Krahn 1991). Cependant, on reconnaît d’importantes différences tant à l’intérieur qu’entre ces formes atypiques d’emploi (Bourhis et Wils 2001 ; Duffy et Pupo 1992 ; Fudge, Tucker et Vosko 2003 ; Lowe, Schellenberg et Davidman 1999 ; Mayer 1996 ; Vallée 1999 ; Vosko 2000 ; Zeytinoglu et Muteshi 1999). Au contraire, les statisticiens et les universitaires en Europe ont abordé le problème du déclin de la relation d’emploi standard en mettant en évidence la notion de l’emploi précaire (Rodgers et Rodgers 1989 ; Silver 1992). Beaucoup d’efforts de recherche malgré tout néglige encore de considérer le lien entre le sexe et la précarité d’emploi. Le « sexe » est ici défini comme le processus par lequel les significations culturelles et les inégalités en termes de pouvoir, d’autorité, de droits et de privilèges en viennent à êtres associées avec une différence sexuelle (Lerner 1997 ; Scott 1986).

Nous avons développé l’idée de relations d’emploi contemporaines comme étant caractérisées par une féminisation des normes de l’emploi (Vosko 2000, 2003), un processus qui implique à la fois la continuité et le changement dans les tendances tant raciales que sexuées de la main-d’oeuvre. La féminisation est typiquement associée avec l’entrée des femmes dans la force de travail, encore que la féminisation des normes de l’emploi renvoie à des tendances plus vastes du marché du travail qui coïncident avec la détérioration de la relation d’emploi standard comme étant la norme et les formes non standard qui démontrent des qualités d’emploi précaire associées aux femmes et à d’autres groupes marginaux (Vosko 2003). La féminisation des normes d’emploi comporte une multitude d’aspects, dont deux sont analysés ici : (1) la polarisation entre les femmes et entre les hommes et les femmes, façonnée par le sexe, la race et d’autres rapports sociaux ; (2) la sexualisation des tâches de façon à ce qu’elle ressemble à ce qu’on appelle « du travail pour les femmes » plus précaire, c’est-à-dire du travail relié à la dispense de soins et du travail non rémunéré dans la sphère domestique. Cependant, à cause des faiblesses des données, cette étude ne peut analyser la façon dont les relations ethniques contribuent à la féminisation des normes de l’emploi depuis que l’Enquête sur la population active et l’Enquête sociale générale recueillent des données fiables sur les sortes d’emploi qui se situent à l’extérieur de la relation d’emploi standard, mais elles ne parviennent pas à recueillir des données adéquates touchant la race ou l’appartenance ethnique.

La deuxième partie de cet article décrit l’approche méthodologique, qui comporte deux étapes. En vue d’établir si les formes d’emploi plus précaires augmentent parmi les hommes et les femmes, nous avons scinder l’emploi total en utilisant une typologie de formes mutuellement exclusives. Ce qui implique un effort de différencier les employés de ceux qui sont des travailleurs autonomes, une distinction qui renvoie au degré de protection législative. Les gens qui sont des travailleurs autonomes sont à leur tour répartis en deux catégories : ceux qui sont des employeurs et ceux qui travaillent à leur compte (ils n’ont pas de salariés). L’analyse porte alors sur le degré de certitude d’un travail continu en les catégorisant par le statut d’employés temporaires ou d’employés permanents. Finalement, chaque forme d’emploi retient la distinction entre un emploi à temps plein et un emploi à temps partiel, parce que cette distinction occupe une place centrale dans toute analyse du sexe de la précarité. La deuxième étape de l’analyse aborde la relation entre les formes de travail salarié et les indicateurs de trois aspects additionnels de la précarité d’emploi : (1) la petite taille de l’entreprise (moins de 20) à titre d’indicateur de la protection législative ; (2) l’étendue de la syndicalisation comme indicateur du contrôle sur le procès de travail et sur la protection législative ; (3) le salaire horaire comme indicateur de revenu.

La troisième partie analyse le sexe et la précarité d’emploi au Canada en recourrant à des données tirées de l’Enquête sur la population active et l’Enquête sociale générale. Au cours de la période 1989-2001, pour les hommes et les femmes, le travail salarié à plein temps et permanent a diminué alors que le travail salarié temporaire et à plein temps et l’emploi des travailleurs à leur compte ont augmenté ; on a observé des augmentations significatives du travail salarié temporaire à temps partiel dans le cas des femmes. En 2001, les hommes étaient plus susceptibles que les femmes d’occuper des emplois permanents à temps plein, alors que les femmes avaient tendance à se retrouver dans des emplois à temps partiel, soit permanents, soit temporaires.

Les employés permanents à temps plein sont les moins susceptibles d’oeuvrer dans des petites entreprises non syndiquées et ils gagnent des salaires plus élevés que ceux gagnés par des personnes qui s’adonnent à d’autres formes de travail salarié, encore qu’il existe aussi des différences entre des employés temporaires et ceux à temps partiel qui résultent en un continuum de travail salarié précaire. La précarité d’emploi s’accroît selon l’ordre suivant : les employés permanents à plein temps constituent la cohorte des moins précaires ; suivent les employés temporaires à plein temps, les permanents à temps partiel et les employés temporaires à temps partiel qui constituent le groupe des plus précaires. En analysant les différences propres au sexe en suivant ce continuum, on illustre ainsi la féminisation des normes d’emploi qui demeurent caractérisée par à la fois la continuité et le changement dans les relations entre les personnes de sexe différent. Le changement se traduit par une « sexualisation des occupations » parmi les employés temporaires et ceux à temps partiel, là où quelques hommes, plus particulièrement les jeunes, bénéficient d’une protection législative réduite et possèdent moins de contrôle tout comme beaucoup de femmes de tous les âges. Il existe une évidente continuité de la persistance des inégalités chez les employés permanents à plein temps, où les hommes obtiennent un meilleur score que les femmes sur les trois indicateurs retenus. Cette continuité est également évidente en termes de polarisation entre les hommes qui exercent une occupation salariée permanente à plein temps, d’un côté ; entre les femmes et les hommes dans un travail salarié permanent à temps partiel et temporaire à temps partiel, d’un autre côté.

La dernière partie consiste, en guise de conclusion, en une présentation des résultats clef. Considérées dans leur ensemble, ces données sur la sexualisation des tâches, la polarisation de la rémunération et la diffusion des formes précaires d’emploi reflètent bien le phénomène de féminisation de l’emploi précaire. Bien que les hommes dans des tâches rémunérées à temps partiel et temporaires s’en tirent plutôt mal, plus de femmes que d’hommes se retrouvent dans des types d’emploi où des dimensions multiples de la précarité convergent. La participation des femmes dans le type le plus précaire de travail salarié (temporaire à temps partiel) s’est accrue vers la fin des années 90. Pour une analyse plus approfondie de la féminisation des normes d’emploi, d’autres travaux devront étudier comment varie l’emploi précaire selon d’autres facteurs, tels que la race et l’ethnie, selon les contextes sociaux importants, tels que l’occupation et le secteur d’activités.

Resúmen

Este artículo examina la relación entre el genero, las formas de empleo y las dimensiones del empleo precario en Canadá, utilizando datos de la Encuesta sobre la fuerza de trabajo y la Encuesta social general. El trabajo asalariado a tiempo completo ha disminuido tanto por las mujeres que por los hombre entre 1989 y 2001, pero las mujeres mantienen una probabilidad mayor que los hombres de ser empleadas a tiempo parcial y ocupar empleos temporales. Si procedemos a una clasificación escalonada de las formas de trabajo asalariado según los indicadores de protección reguladora, control e ingresos, se obtiene un continuum donde los empleados a tiempo completo figuran como los menos precarios, seguidos de los trabajadores temporales a tiempo completo y de los permanentes a tiempo parcial, mientras que los temporales a tiempo parcial representan los trabajadores mas precarios. Este continnum adopta un genero cuando se considera las desigualdades entre mujeres y hombres con empleo permanente a tiempo completo y la convergencia entre la precaridad de las mujeres y hombres con empleo a tiempo parcial o a estatuto temporal. Estos resultados reflejan la feminización de las normas de empleo que encarnan la continuidad y el cambio en las relaciones sociales de género.

Article body

Evidence of the decline of the standard employment relationship (SER) and its associated gender relations is escalating in Canada. The SER refers to a normative model of employment where the worker has one employer, works full-time, year-round on the employer’s premises under his or her supervision, enjoys extensive statutory benefits and entitlements, and expects to be employed indefinitely (Muckenberger 1989; Schellenberg and Clark 1996; Vosko 1997). The SER became the statistical reality for (primarily white) men in Canada in the post World War II era, yet forms of employment that fall outside this norm and that employ primarily women have grown since the late 1970s (Fudge and Vosko 2001a). Nevertheless, the SER remains the model upon which labour laws, legislation and policies are based, prompting a correlation between the growth in “non-standard” forms of employment and a rising precariousness that is highly gendered (Fudge and Vosko 2001b; Vallée 1999; Vosko 1997).

The aim of this article is to examine the links between gender, forms of employment and dimensions of precarious employment in the Canadian labour force.[1] Precarious employment is defined as forms of employment involving atypical employment contracts, limited social benefits and statutory entitlements, job insecurity, low job tenure, low earnings, poor working conditions and high risks of ill health. Thus, the term “precarious employment” places emphasis on the quality of employment. Gender is the process through which cultural meanings and inequalities in power, authority, rights and privileges come to be associated with sexual difference (Lerner 1997; Scott 1986). To speak of the “gendering” of a phenomenon is to focus attention on the process whereby sex differences become social inequalities. To argue that a phenomenon is gendered is to emphasize that gender shapes social relations in key institutions that organize society, such as the labour market, the state or the family (Acker 1992).

Few studies examine how dimensions of precariousness vary across forms of employment and fewer still focus on the gender of precarious employment. There is a common tendency to group together a broad range of employment forms and work arrangements, unified by their deviation from the SER, into a single category of “non-standard employment” (Carre et al. 2000; Economic Council of Canada 1990; Krahn 1991). However, there are important differences both between and within the forms of employment that fall outside the SER. For example, different regulatory challenges are posed by own account self-employment, the triangular employment relationship characterizing wage work in the temporary help industry and part-time permanent wage work (Duffy and Pupo 1992; Fudge, Tucker and Vosko 2003; Mayer 1996; Vosko 2000). With economic restructuring, there is also growing income polarization among full-time permanent paid employees (James, Grant and Cranford 2000; Luxton and Corman 2001). Finally, there are inequalities along lines of gender, “race” and ethnicity within both standard and non-standard forms of employment (Das Gupta 1996; Zeytinoglu and Muteshi 1999).

The heterogeneity among forms of employment that fall outside the SER makes it necessary to question what have come to be normalized descriptive concepts—terms such as “non-standard employment.” Scholars have begun to look within the category “non-standard employment” by distinguishing between person-level and job-level characteristics (Bourhis and Wils 2001), by focusing on the concentration of racialized groups in non-standard employment (Zeytinoglu and Muteshi 1999) and by distinguishing between structural and social psychological dimensions of changing employment relationships (Lowe, Schellenberg and Davidman 1999). However, few studies have examined how variations in dimensions of precariousness, both between and within forms of employment, are gendered.

In this article, we illustrate how precarious employment in the Canadian labour force reflects the feminization of employment norms. The feminization of employment norms denotes the erosion of the standard employment relationship as a norm and the spread of non-standard forms of employment that exhibit qualities of precarious employment associated with women (Vosko 2003). Although many scholars focus on the changing nature of work, profound continuities characterize the contemporary labour force; specifically, women, immigrants and people of colour continue to occupy the more precarious segments of the labour market (Arat-Koc 1997; Bakan and Stasiulus 1997). Analyses that fail to focus on the growth of precarious employment in relation to continuing gender inequalities may conceal important aspects of the contemporary labour market.

To advance this argument, the article proceeds in four parts. The first part reviews concepts used to describe and explain changing employment relationships and, in order to highlight the gender of precarious employment, offers the “feminization of employment norms” (Vosko 2003) as an alternative concept. The second part outlines the methodological approach. The third part of the article uses Statistics Canada data to examine the gender of precarious employment in the contemporary Canadian labour force by first examining the participation of women and men in mutually exclusive forms of employment and then layering four forms of wage work with other dimensions of precariousness, namely degree of regulatory protection, control and wages.[2] Gender differences along these dimensions both between and within forms of employment are of primary concern. The fourth part concludes by summarizing key findings and pointing to avenues for future research.

Conceptualizing Changing Employment Relationships

Non-Standard Employment

In the Canadian context, the growth of “non-standard employment” became a significant topic of discussion in the 1980s. The discussion intensified when the Economic Council of Canada pronounced that the growth of non-standard employment was outpacing the growth of full-time full-year jobs. In its study, Good Jobs, Bad Jobs (1990: 12), the Council reported that fully one-half of all new jobs created between 1980 and 1988 were “non-standard,” which it defined simply as “those [jobs] that differ from the traditional model of the full-time job.” In response to the Council’s study, several government reports examined the growth of non-standard forms of employment and work arrangements (Advisory Group on Working Time 1994; Human Resources and Development Canada 1994).

Harvey Krahn produced the earliest study on the growth of non-standard employment in Canada. Krahn’s (1991) broadest measure for non-standard employment was made up of four situations that differed from the norm of a full-time, full-year, permanent paid job: (1) part-time employment; (2) temporary employment, including employees with term or contract, seasonal, casual and all other forms of wage work with a pre-determined end date; (3) own-account self-employment (i.e. self-employed persons with no paid employees); and (4) multiple job holding. In a follow-up study, Krahn (1995) found that women remained more likely than men to have non-standard employment although as part-time and temporary employment grew, the proportion of men in these forms of employment also rose.

The employment situations comprising the broad definition of non-standard employment are not mutually exclusive making it difficult to determine whether the more precarious types of employment are those that are growing (Vosko, Zukewich and Cranford 2003). Part-time employment includes paid employees and the self-employed (both own-account and employers), and the work of part-time employees can be of temporary or permanent duration. Furthermore, multiple job holding is more of an arrangement than a form of employment since all employed people can hold multiple jobs. There is thus a pressing need to move away from grouping together situations that are united primarily by their deviation from the standard employment relationship if we are to understand the extent of precarious employment in the labour force.

Precarious Employment

European statisticians and scholars have addressed the decline of the standard employment relationship and related concerns over under-employment, income insecurity and social exclusion, by elevating the notion of precarious employment (Silver 1992). The influential volume, Precarious jobs in labour market regulation (Rodgers and Rodgers 1989), reveals the central problem of focusing solely on forms of employment as a means of exploring employment change. To remedy this problem, Rodgers (1989: 3–5) identifies four dimensions central to establishing whether a job is precarious, each of which focuses on the quality of jobs. The first dimension is the degree of certainty of continuing employment; here, time horizons and risk of job loss are emphasized. Second, Rodgers introduces the notion of control over the labour process, linking this dimension to the presence or absence of a trade union and, hence, control over working conditions and pace of work. Rodgers’ third dimension is the degree of regulatory protection through union representation or the law. Fourth, Rodgers suggests that income level is a critical element, noting that a given job may be secure in the sense that it is stable and long-term but precarious in that the wage may still be insufficient for the worker to maintain herself/himself as well as dependants.

The concept “precarious employment” takes us beyond the broad notion of non-standard employment. Nevertheless, much research on precarious employment overlooks gender. For example, the dimension of hours of employment must be included if we are to understand how precariousness is gendered (Vosko 2003).

The Feminization of Employment Norms

Recent feminist scholarship argues that changing employment relations are both shaped by and, in turn, shape enduring gender inequalities both inside and outside the labour market (Armstrong 1996; Bakker 1996; Fudge 1991; Spalter-Roth and Hartmann 1998; Jenson 1996; Vosko 2000). This process of continuity through change can be conceptualized as the feminization of employment norms, a concept that denotes the erosion of the standard employment relationship as a norm and the spread of non-standard forms of employment that exhibit qualities of precarious employment associated with women and other marginalized groups (Vosko 2003). Similar processes have been described as the creation of more “women’s work in the market” (Armstrong 1996: 30) and a new set of “gendered employment relationships” (Jenson 1996: 5).

In most OECD countries, the post World War II “gender order”—that is, the dominant set of gender relations operating in society (Connell 1987)—was shaped by the standard employment relationship (SER), yet empirically the SER and its associated gender order began to show signs of erosion in the early 1970s. The SER refers to a normative model of employment where a worker has one employer, works full-time, year-round on the employer’s premises under his or her supervision, enjoys extensive statutory benefits and entitlements and expects to be employed indefinitely (Muckenberger 1989; Schellenberg and Clark 1996; Vosko 1997). The SER is based on what some characterize as a “patriarchal model” (Eichler 1997) and others conceive as a male breadwinner/female caregiver or “family wage” model (Fraser 1997). That is, the SER was designed to provide a wage sufficient for a man to support a wife and children. In Canada, in the immediate post-World War II period, the SER became the statistical reality for most (primarily white) men, while most women, as well as immigrants, migrants and racialized groups, were relegated to part-time, seasonal and other precarious forms of employment (Fudge and Vosko 2001a; also Bakan and Stasiulus 1997; Arat-Koc 1997). In the 1970s, fundamental cracks in the post World War II gender order—related to macroeconomic instability in the global economy—began to appear and more employed people, including more men, lost their claim to the SER. At the same time, forms of employment falling outside this norm, such as contract, temporary and part-time employment have grown.

The forms of employment that fall outside of the standard employment relationship have been historically, and continue to be, associated with women (Fudge and Vosko 2001a, 2001b; Spatler-Roth and Hartmann 1998). It is assumed their perceived roles in the daily and generational maintenance of people (i.e. social reproduction) lead women to freely choose part-time and temporary forms of employment and these assumptions justify women’s concentration in less secure employment with lower wages and fewer benefits. A more complex interpretation of these patterns is that a set of gendered trade-offs contributes to the betterment of men’s labour market position and the entrenchment of precarious employment amongst women; recent research confirms that, among both employees and the self-employed, most men say they engage in part-time work in order to pursue their education but hardly any men trade-off part-time work for care giving, while many women say they engage in part-time work for reasons related to care giving (Vosko 2002; also Armstrong 1996; Duffy and Pupo 1992; Women in Canada 2001). In short, feminist scholars argue that the over-representation of women in more precarious forms of employment is shaped by continuous gender inequalities in households resulting in women’s greater responsibilities for unpaid domestic work compared to men.

Due to these processes of continuity and change, contemporary labour market trends are best conceptualized as a feminization of employment norms, rather than as genderless processes of casualization or erosion. Feminization is typically associated with only women’s mass entry into the labour force or simply with the changing gender composition of jobs but the “feminization of employment norms” refers to four facets of racialized and gendered labour market trends: (1) high levels of formal labour force participation among women; (2) continuing industrial and occupational segregation; (3) income and occupational polarization both between and among women and men; (4) the gendering of jobs to resemble more precarious so called “women’s work”—that is, work associated with women and other marginalized groups.[3] Each of these facets of feminization increased in the 1990s in Canada (Vosko 2002).

This paper focuses in depth on the gendering of jobs and income polarization. Due to the shortcomings of existing surveys, we are unable to examine how intersections of “race” and gender contribute to the feminization of employment norms.[4] Also characterized as “harmonizing down” (Armstrong 1996), the gendering of jobs captures the fact that certain groups of men are experiencing downward pressure on wages and conditions of work much like those typically associated with “women’s work,” while many women continue to endure economic pressure (Vosko 2003). Similar processes have been conceptualized as the feminization of the labour process through the employment of undocumented immigrant women and men in restructuring industries (Cranford 1998). Indeed, empirical studies have shown that among men, it is primarily young men, racialized men and recent immigrant men who are experiencing this facet of the feminization of employment norms (Armstrong 1996; Cranford 1998; Vosko 2002). Income polarization is the result of occupational and income disparities between men and women, as well as among women and among men along the lines of “race,” ethnicity, age and other social locations (Vosko 2000). Previous research has found growing income and occupational polarization among women by “race,” ethnicity and immigrant status (Bakan and Stasiulus 1997; Das Gupta 1996; James, Grant and Cranford 2000; Vosko 2002).

Methodological Approach

There is a disjuncture between conceptual advances concerning changing employment relationships and methods suitable to measure these changes. Gendered processes and complex labour force trends are not easily detected with a single, quantitative method of analysis. At the same time, qualitative case studies are able to uncover complex processes but cannot depict broader patterns and trends. To remedy this gap, the ensuing analysis proceeds in two steps.

First, in order to determine if the more precarious forms of employment are growing for women and men, we break down total employment into a typology of mutually exclusive forms. The typology, summarized in Figure 1, first differentiates employees from the self-employed. This distinction relates to an important dimension of precariousness—degree of regulatory protection (Fudge, Tucker and Vosko 2003).[5] Self-employed people are further distinguished by whether they are self-employed employers or own account self-employed who have no employees. The own account self-employed persons are arguably in a more precarious position than the self-employed who profit from others’ labour. The analysis then addresses the degree of certainty of continuing work by categorizing employees by temporary or permanent status.[6] Temporary employees are less likely than permanent employees to have full access to collective bargaining and some aspects of employment standards legislation due to difficulties in establishing who is the employer for agency workers and due to short job tenure for other temporary workers (Vallée 1999; Vosko 2000). Finally, it is important to break down each employment form by part-time/full-time status[7] since this distinction is central to any analysis of the gender of precariousness. Eligibility for certain programs, such as Employment Insurance, is based on both hours and permanency (Vosko 2003). Together the white boxes represent what are conceptualized as the more precarious forms of employment.

Figure 1

Typologie of Mutually Exclusive Employment Forms, Canada 2001

1 Total Employment ages 15 and over.

The analysis consists of examining the growth in the mutually exclusive forms of employment, for women and men, using data from the General Social Survey (GSS) for the time periods 1989 and 1994 and the Labour Force Survey (LFS) for the time periods 1997 and 2001.[8] Unreliable estimates are suppressed.[9] We also calculate coefficients of variation in order to assess the degree of sampling variability.

In addition to those embedded in the form of employment itself, other dimensions of precariousness vary across forms of employment. Here we focus on the quality of four forms of wage work—full-time permanent, full-time temporary, part-time permanent and part-time temporary—by examining their relationship with three indicators of precariousness – firm size, union coverage and hourly wages. Firm size less than twenty[10] is a good indicator of the degree of regulatory protection among employees since labour law often does not apply in these firms and the pieces of legislation that do apply are ill-enforced or difficult to use (Fudge 1991). Union coverage[11] is a suitable indicator of precarious employment since unionized workers have a higher degree of control over the type of work they do and the pace and conditions under which they labour, have more job security and a higher degree of regulatory protection written into collective agreements, compared to non-union workers (Rodgers 1989; Duffy and Pupo 1992). Hourly wage[12] is also a suitable indicator of precarious employment since it makes up an important part of income and is thus central to the ability to maintain an adequate standard of living.

The second stage of analysis focuses on employees at one point in time, 2001, and uses data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS).[13] It examines the percent of employees in each form of wage work who are employed in firms with less than 20 employees and who have union coverage, as well as their mean hourly wages. The analysis then focuses on gender differences in precarious employment within the four forms of wage work. In order to determine whether the gender observed differences are real or due to sampling error, we calculate t-tests of the differences between women and men of the same age within a given form of wage work.[14] We also calculate wage ratios relative to full-time permanent men, the form of employment still held by most men, both unionized and non-unionized. A large body of research illustrates that gender inequalities in the labour force are not only produced through direct discrimination resulting in unequal outcomes among women and men in similar locations in the economy, but also indirectly, for example through polarized occupational and income structures (Armstrong 1996; James, Grant and Cranford 2001; Vosko 2002; Women in Canada 2001). These relative wage ratios allow for an examination of differences between men and between women across forms of employment.

Both stages of the analysis—estimating the growth of non-standard forms of employment among women and men and assessing the quality of those forms of employment for women and men today—are necessary to empirically demonstrate the feminization of employment norms.

The Gender of Precarious Employment in Canada

The Growth of Precarious Forms of Employment

Examining mutually exclusive forms of employment brings insight into the relationship between non-standard forms of employment, growing precariousness and gender. Full-time permanent wage work is becoming less common, dropping from sixty-seven percent of total employment in 1989 to sixty-three percent in 2001, although these employees still account for the majority of total employment (Table 1). The well-documented growth in self-employment in the 1990s (Hughes 1999) is largely due to growth in own-account self-employment, while self-employed employers declined during the same period. The number of people with temporary wage work rose steadily throughout the 1990s, fueled by the growth in full-time temporary wage work. The proportions of total employment with part-time temporary or part-time permanent wage work remained steady during this period (Table 1).

Examining these trends for women and men reveals both continuity and change in the social relations of gender. While the absolute decline in full-time permanent wage work was slightly greater for men as compared to women, men were still more likely to have this form of wage work in 2001. Sixty-six percent of male total employment was full-time and permanent compared to sixty percent of female total employment (Table 1). Similarly, increases in full-time temporary wage work were observed for both women and men, yet the percent of women’s total employment that was both part-time and temporary also increased significantly from 1989 to 2001. Furthermore, women were still twice as likely to be in part-time temporary employment in 2001 when compared to men. In contrast, the percent of women’s employment that was both part-time and permanent declined. The percent of men’s and women’s employment that was own-account increased over the period suggesting that both were engaging in more precarious types of self-employment (Table 1).

Continuity in gender inequality is further revealed when we examine the shares of women in the different forms of employment in the contemporary period (Figure 2). In 2001, the majority of those in forms of employment with inadequate regulatory protection were women. The widely documented concentration of women in part-time wage work (Duffy and Pupo 1992; Women in Canada, 2001) was still true of both employees and the self-employed by 2001. In 2001, women accounted for over six in ten of those with part-time temporary wage work and part-time self-employment (whether own-account or employers) and for nearly three-quarters of part-time permanent employees. In contrast, men accounted for the majority of those engaged in full-time employment, whether in temporary or permanent wage work or as own account or self-employed employers (Figure 2). The enduring concentration of women in all forms of part time work suggests that profound continuities in gender inequality remain alongside the movement of more men into forms of employment where women labour.

Table 1

Mutually Exclusive Employment Forms for Women and Men, Canada 1989 - 2001

1 Total Employment ages 15 and over. Numbers rounded to the nearest thousand. LFS estimates include unpaid family workers

– Indicates sample size too small to yield estimate; ^ indicates high sampling variablility (coefficient of variation between 16.6% and 33.3%). Estimates to be used with caution.

Figure 2

Women’s Share of Employment Forms, Canada 2001

1Total Employment ages 15 and over.

Young men are engaged in precarious employment alongside women of all ages. In 2001, sixty percent of part-time permanent male employees were aged 15 to 24, compared to twenty-nine percent of part-time permanent female employees. In contrast, only thirty-one percent of part-time permanent male employees were aged 25 to 54, compared to sixty-one percent of part-time permanent female employees. Similarly, sixty-eight percent of part-time temporary male employees were aged 15 to 24, compared to 50 percent of part-time temporary female employees; and only 23 percent of part-time temporary male employees were aged 25 to 54 compared to 43 percent of part-time temporary female employees.[15]

Similarly, increases in full-time temporary wage work were observed for both women and men, yet the percent of women’s total employment that was both part-time and temporary also increased significantly from 1989 to 2001. Furthermore, women were still twice as likely to be in part-time temporary employment in 2001 when compared to men. In contrast, the percent of women’s employment that was both part-time and permanent declined.

These findings illustrate the importance of conceptualizing labour market trends as a feminization of employment norms. The growth of more precarious forms of employment affects both women and men, but has a greater impact upon women. Both women and men increased their participation in two forms—full-time temporary wage work and own-account self-employment—that are driving the growth of “non-standard employment.” However, women also increased their participation in part-time temporary employment—a form of wage work that fits the least well with the standard employment relationship upon which labour and employment legislation are based. In addition, in 2001 precarious forms of employment were still more likely to employ women than men. By examining other dimensions of precarious employment, we can more fully understand how changing employment relationships contribute to insecurity in the Canadian labour force and how this process is gendered.

A Gendered Continuum of Precarious Wage Work

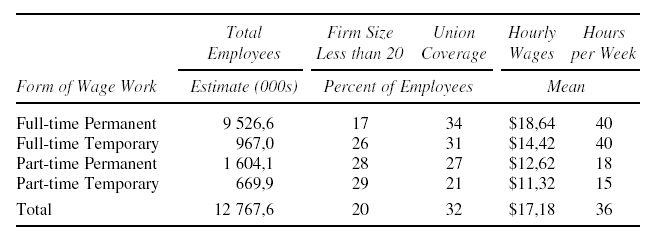

Layering forms of employment with the three additional indicators of precariousness, the typology gives way to a continuum of precarious wage work. Full-time permanent employees are the least precarious along multiple dimensions, but there are also important differences between the temporary and part-time employees. Precarious employment increases along the continuum in the following order: full-time permanent employees as the least precarious followed by full-time temporary, part-time permanent and part-time temporary employees as the most precarious (Table 2). Thus, full-time status defines precariousness more so than temporality. For example, only seventeen percent of full-time permanent employees labour in firms with less than twenty employees, compared with over one in four employees in any of the other three forms of wage work. At the same time, full-time temporary employees are more likely to work in large firms, compared to employees in the two part-time forms. Thirty-four percent of full-time permanent employees are covered by a union contract, compared to thirty-one percent of full-time temporary employees. At the same time, part-time temporary employees are less likely to be covered by a union contract than part-time permanent employees, twenty-one percent compared to twenty-seven percent. Finally, full-time permanent employees earn on average over four dollars an hour more than full-time temporary employees do. Nevertheless, full-time temporary employees earn on average nearly two dollars an hour more than part-time permanent employees who, in turn, earn over a dollar an hour more than part-time temporary employees (Table 2).

Table 2

A Continuum of Precarious Wage Work, Canada 2001

1 Employees ages 15 and over. Numbers rounded to the nearest thousand.

The continuum of precarious wage work is gendered in one way through the greater concentration of women in the most precarious forms of wage work. The analysis in the previous section illustrates that women are concentrated in part-time permanent and part-time temporary wage work and that their concentration in part-time temporary wage work grew in the 1990s. Combined with these findings, we can confirm that women are labouring in those forms of employment that are the most precarious on multiple dimensions. For example, part-time temporary employees were the most precarious in terms of firm size, union coverage and hourly wages and sixty-three percent of these employees were women in 2001. In contrast, women made up only forty-four percent of the least precarious employees—those with full-time permanent wage work (Figure 2).

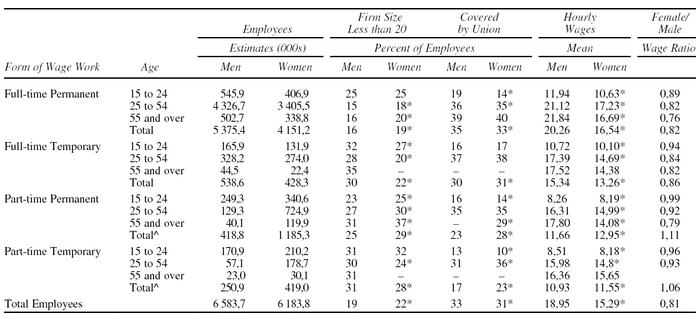

Examining differences between women and men within the forms of wage work points to a second way the continuum of precarious wage work is gendered, one that reflects both continuity and change in gender relations. Among full-time permanent employees we find continuing gender inequalities (Table 3). In 2001, women in full-time permanent wage work were more likely than their male counterparts to labour for small employers, with the exception of youth (Table 3). These same women were less likely than their male counterparts to be covered by a union contract, with the exception of those over age 55. Furthermore, women in full-time permanent wage work earned an average wage that is eighty-two percent of their male counterparts (Table 3). Their lower wage combined with fewer hours of work each week resulted in earnings of approximately $629 a week—$200 less than their male counterparts. Too often, commentators assume that full-time permanent jobs are “good jobs,” while all other non-standard jobs are “bad jobs” (Economic Council of Canada 1990). In contrast, this analysis reveals that, along multiple dimensions, full-time permanent wage work is not as good for women as it is for men.[16]

Table 3

Indicators of Precarious Wage Work for Women and Men, Canada 2001

1 Employees ages 15 and over. Numbers rounded to the nearest thousand.

* Women are statistically different from men of the same form and age group at the .05 level; wage ratios are reported only when significant difference.

^ Totals for part-time permanent and part-time temporary employees are misleading due to the different sex composition across the age groups. Most male part-time workers are 15–24, while large number of women part-time employees are 25–54. Since women aged 25–54 earn much more than men aged 15–24, the total wages of women are larger than the total wages of men despite the fact that men earn more in each age group.

– Indicates sample size too small to yield estimate.

Examining gender differences within the categories of temporary and part-time employees illustrates the gendering of jobs. Vosko (2003) theorizes the gendering of jobs as a process whereby certain groups of men are experiencing downward pressure on wages and conditions of work much like those typically associated with “women’s work”, while many women continue to endure economic pressure. These findings illustrate that this process is occurring among temporary and part-time employees primarily along the dimensions of regulatory protection and control (measured here as firm size and union coverage).

Among full-time temporary employees, men are more likely than their female counterparts to be employed by small firms suggesting that they have less regulatory protection (Table 3). There is no statistically significant difference in union coverage between women and men temporary full-time employees, once age is controlled. Nevertheless, these men still earn a higher hourly wage than women, except those aged 55 and over. Importantly, the female/male wage gap is more pronounced among those aged 25 to 54 than among the youth (Table 3).

When examining gender differences among part-time employees (permanent and temporary) it is especially important to examine differences by age group. As discussed above, most women in part-time jobs were aged 25–54, while most men in part-time jobs were aged 15–24. Women aged 25–54 make much more than men aged 15–24, thus the age composition brings up the average wages of total women. The gender composition across age groups explains why the total wages for women were higher than they are for men although men earned higher wages in each age group.

Among part-time permanent employees, women were more likely to work in small firms across all age groups. They were more likely, as a group, to be covered by a union contract, but there was no statistically significant difference between women and men among those aged 25 to 54 (Table 3). This reflects, in part, the concentration of this cohort of women in the public sector where unionization rates are high (Armstrong 1996; Duffy and Pupo 1992). Nevertheless, women part-time permanent employees aged 25 to 54 earned an average wage just under fifteen dollars an hour, compared to over sixteen dollars an hour for their male counterparts. Young women and young men in this form of wage work earned significantly lower wages—slightly over eight dollars an hour.

The gendering of jobs is most evident when we examine gender differences among part-time temporary employees. Men in part-time temporary wage work were more likely than their female counterparts to be employed in small firms, except the young who, notably, made up most male employment in this form. In turn, middle-aged women were more likely to be covered by a union contract than men in this form of wage work were, while the opposite was true among the youth. At first glance women, appear to be doing better than men in terms of wages. However, this advantage is explained by the age distribution. Within the oldest age group there is no statistically significant difference between women and men’s wages and there is little substantive gender difference between the young. However, among the 25 to 54 age group women earned ninety-three percent of men (Table 3). These trends indicate a need to examine wages more closely.

Given that full-time permanent male employees are the least precarious, and most men are employed in this form of wage work, it is useful to compare women to this group of men in order to gain a more complete picture of the gender of precariousness in the labour force. Doing so reveals a second key facet of the feminization of employment norms—income polarization. These findings illustrate polarization in wages between full-time permanent male employees and both women and men in the other three forms of wage work. Most women in full-time temporary, part-time permanent and part-time temporary wage work are aged 25 to 54. On average, these women earn roughly seventy percent of the average wage received by full-time permanent men of the same age, reflecting gender polarization in wages across forms of wage work (Table 4). Unionization decreases this wage gap considerably but does not eliminate it. Most men in the more precarious forms of wage work are young. Among those aged 15 to 24, men in part-time permanent and part-time temporary wage work earn sixty-nine percent and seventy-one percent, respectively, of full-time permanent men of the same age and this does not change significantly with unionization. Together these patterns illustrate wage polarization among men by form of employment alongside continuing gender inequality both within and between forms of wage work.

Alongside the gendering of jobs and wage polarization, it is also important to remember that only fifteen percent of total male employment is full-time temporary, part-time permanent and part-time temporary wage work combined, compared to twenty-nine percent of female employment (Table 1). This analysis of the quality of the four forms of wage work, together with the analysis of the spread of non-standard forms of employment, illustrate key aspects of the feminization of employment norms. The standard employment relationship is eroding as a norm and non-standard forms of employment that exhibit qualities of precarious employment associated with women and other marginalized groups are growing (Vosko 2003).

Table 4

Wage Precariousness Relative to Full-time Permanent Men, Canada 2001

1 Employees ages 15 and over. Numbers rounded to the nearest thousand.

– Indicates sample size too small to yield estimate.

Conclusion

The gender order characterizing the post-World II War era is crumbling as the standard employment relationship (SER) is eroding as a norm. The contemporary period is characterized by complex trends because no new normative employment relationship and no new dominant gender order have yet emerged (Cossman and Fudge 2002; Vosko 2003). As a result, confining scholarly work to investigating the rise of non-standard employment not only masks enduring gender inequalities but also mystifies labour force trends.

The foregoing findings illustrate both a decline in the SER as a norm and enduring gender inequalities in line with the notion of the feminization of employment norms. The feminization of employment norms denotes the erosion of the standard employment relationship as a norm and the spread of non-standard forms of employment that exhibit qualities of precarious employment associated with women and other marginalized groups (Vosko 2003). The empirical analysis demonstrates the growth of more precarious non-standard forms of employment and its gendered character. Both women and men have increased their participation in full-time temporary wage work and own account self-employment, as these forms have grown, signaling growing precariousness among both women and men. Yet, women have also increased their participation in part-time temporary wage work, which is the most precarious form of wage work. Still, it is misleading to focus entirely on rates of change without also examining enduring continuities in women’s concentration in precarious employment. Women are more likely than men to engage in part-time employment, whether in temporary or permanent wage work or in self-employment as either own account workers or self-employed employers; and men still hold a greater share of full-time permanent wage work.

An understanding of the gender of precariousness is furthered by layering permanency and hours with additional dimensions of precarious employment among employees. Full-time permanent employees are the least likely to labour in small, non-union firms, suggesting higher levels of regulatory protection and control, and these employees earn higher wages than the other forms of wage work. However, there are also differences between temporary and part-time employees resulting in a continuum of precarious wage work. Precariousness increases in the following order: full-time permanent employees as the least precarious followed by full-time temporary, part-time permanent and part-time temporary employees as the most precarious.

Examining gender differences within and across forms of employment illustrates two key facets of the feminization of employment norms—the gendering of jobs and polarization in wages. Women in the least precarious form of employment continue to be more precarious than men. Full-time permanent male employees are more likely than their female counterparts to work in large, unionized firms and a significant female-to-male wage gap persists. This suggests that even those women in full-time permanent wage work have less regulatory protection, control and ability to support themselves and their dependents, compared to men. There is, therefore, a pressing need to break down the dominant concept “standard employment” and its association with a “good” job and to begin to ask: good for whom?

Alongside this pervasive gender inequality among employees with full-time permanent wage work, a convergence in precariousness at the bottom of the labour market is also underway. The gendering of jobs denotes the downgrading of employment to reflect the more precarious wages and working conditions historically reserved for women so that certain groups of men are experiencing downward pressure on wages and conditions of work, while many women are enduring continued economic pressure (Vosko 2003). This study finds that, in the present period, the “gendering of jobs,” is occurring along the dimensions of regulatory protection and control (measured here as firm size and union coverage), more so than in terms of income from wages. While men in temporary wage work (both full-time and part-time) are more likely than women to be employed in small firms, the opposite is true. in the permanent forms of wage work. Furthermore, among middle aged full-time temporary and part-time permanent employees, women and men are equally likely to be covered by a union contract. Despite this convergence in precariousness along these two indicators, women still earn significantly lower hourly wages compared to men within all forms of wage work.

When the wages of women and men in temporary and part-time forms of wage work are examined relative to the least precarious group (i.e., full-time permanent male employees), a picture of gendered polarization emerges. Both women and men in full-time temporary, part-time permanent and part-time temporary forms of wage work are doing more poorly than men in full-time permanent wage work. This indicates wage polarization among men by form of employment. However, gender inequality in wages is evident both between and within the forms of wage work.

Taken together, these findings on the gendering of jobs, wage polarization and the spread of precarious forms of employment illustrate the feminization of employment norms. The analysis reveals more gender parity within part-time permanent and part-time temporary wage work than within full-time permanent wage work; yet the former forms of employment fail to provide regulatory protection, control over work or an adequate wage for anyone. The growing, albeit still small, number of men in part-time and temporary wage work reflects growing inequality among men by form of employment. Nevertheless, sixty-six percent of men are employed in the least precarious form of employment—full-time permanent wage work. Furthermore, among men, it is primarily young men who are employed in temporary and part-time wage work, while women of all ages continue to be concentrated in these forms of employment. More women than men are located in segments of the labour force where multiple dimensions of precarious employment converge.

The continuing concentration of women in the most precarious forms of employment points to the need to examine more fully the relationship between precarious employment and activities related to social reproduction (i.e., the daily and generational maintenance of people). Qualitative research could also assist our understanding of how jobs are gendered by probing the meanings assigned by employers and workers to the work that women do. In order to explore fully the feminization of employment norms, future research must consider how precarious employment varies by other social locations, such as “race” and ethnicity, and key social contexts, such as occupation and industry.

Appendices

Remerciements

Authors are listed alphabetically to reflect equal contribution. We would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Grant # 833–2000–1028) for funding the research on which this article iss based. We also thank John Anderson, Pat Armstrong, Judy Fudge, Martha MacDonald, Robert Wilton, the participants in the Community University Research Alliance on Contingent Work and the anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments on earlier versions of this paper. The article reflects the views of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Statistics Canada or those of the Alliance on Contingent Employment.

Notes

-

[1]

This analysis is limited to precarious employment in the labour force and does not address issues of unemployment or entry into the labour force.

-

[2]

We use the term “wage work” to define employees who earn salaries as well as hourly wages. Statisticians use the term “paid work” for what we are here calling “wage work.” We use the term wage work instead because, in feminist scholarship, paid work is more commonly contrasted to unpaid work and because the own account self-employed are also paid (by their clients) but they are not paid wages.

-

[3]

For example, it is often asserted that migrant workers and other marginalized groups have access to forms of subsistence beyond the wage and this assertion is often used to justify paying them lower wages.

-

[4]

The LFS and the GSS collect excellent data on forms of employment that fall outside the SER but they do not collect adequate data on “race” or ethnicity. The LFS does not ask about visible minority or immigrant status. The GSS does ask about ethnic background. However, samples sizes for temporary workers in a given ethnic group are small. The census has larger sample sizes but does not ask questions about temporary work. The Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) 2000 file will be available soon for public use, allowing researchers to examine temporary work among immigrants and racialized groups in the late 1990s.

-

[5]

For the most part, the self-employed are treated as entrepreneurs who do not require statutory protection; however, there is wide variation in coverage. See Fudge, Tucker and Vosko (2003) for an analysis of the coverage of independent contractors under common and civil law of employment, collective bargaining, employment standards, human rights, workers’ compensation and social wage legislation across four Canadian jurisdictions. Due to this complexity and the scope of this article, here we only point to a few specific pieces of legislation.

-

[6]

Neither the LFS nor the GSS distinguish between temporary employees who work through an agency and other employees with a predetermined end date. These surveys do not ask questions about job permanency of self-employed workers.

-

[7]

Since 1997, the LFS has defined part-time workers as consisting of people (wage and salary workers and the self-employed) who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job. The 1989 and 1994 GSS estimates in this analysis have been revised to match the new definitions of part-time work in the LFS.

-

[8]

The LFS dates back to 1976 but the survey did not ask whether one was employed in a temporary job until 1997. The GSS collected this information as far back as 1989. However, the GSS was last conducted in 1994. The use of these two surveys does not significantly affect the results on change in various forms of employment over time because the variables that make up the form of employment derived variable are measured in a similar way in the two surveys.

-

[9]

We followed Statistics Canada guidelines regarding either minimum estimate or minimum sample size cut-offs for each survey. The LFS recommends suppressing estimates smaller than 1,500. The GSS recommends suppressing sample sizes that are less than 15, which corresponds to an estimate of roughly 30,000 when weighted.

-

[10]

The firmsize variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable: firmsize less than 20/firmsize 20 and over.

-

[11]

The union variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable that combined union members and those non-members who are covered by a union contract (collective agreement), compared to all those not covered by a union contract. We use union coverage, rather than union membership, because workers covered by a union contract generally have a more similar level of control and job security to union members than they do to non-union members.

-

[12]

In some cases, the standard deviations are high indicating difference within a category. Standard deviations and median wages are available from the authors.

-

[13]

Most surveys do not collect data on indicators of precariousness for the self-employed, in part due the conception that all self-employed are entrepreneurs. An exception is the Survey of Self Employed (see Fudge, Tucker and Vosko 2003).

-

[14]

T-tests were run using a standardized weight. This does not account entirely for the sampling design of the LFS but the use of standardized weights is an accepted approximation. Without corrections for stratified samples, estimates of sampling error will be too great; thus, our estimates of statistically significant difference are conservative ones.

-

[15]

These figures are based on analysis of the 2001 LFS.

-

[16]

Human capital characteristics as well as gender-related wage biases also play a role in the persistent inequality between women and men in full-time permanent jobs.

References

- Acker, J. 1992. “From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions.” Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 21, No. 5, 565.

- Advisory Group on Working Time and the Distribution of Work. 1994. Report of the Advisory Group on Working Time and the Distribution of Work. Ottawa: Human Resources Development Canada.

- Arat-Koc, S. 1997. “From ‘Mothers of the Nation’ to Migrant Workers.” Not One of the Family. A. Bakan and D. Stasilus, eds. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 53.

- Armstrong, P. 1996. “The Feminization of the Labour Force: Harmonizing Down in a Global Economy.” Rethinking Restructuring: Gender and Change in Canada. I. Bakker, ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 29.

- Bakan, A., and D. Stasiulus. 1997. “Making the Match: Domestic Placement Agencies and the Racialization of Women’s Household Work.” Signs, Vol. 20, No. 2, 303.

- Bakker, I. 1996. “Introduction: The Gendered Foundations of Restructuring in Canada.” Rethinking Restructuring: Gender and Change in Canada. I. Bakker, ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 3.

- Bourhis, A., and T. Wils. 2001. “L’éclatement de l’emploi traditionnel: les défis posés par la diversité des emplois typiques et atypiques.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 56, No. 1, 66.

- Carre, F., M. Ferber, G. Lonnie and S. Herzenberg. 2000. Non-Standard Work Arrangements. Madison, Wisc.: Industrial Relations Research Association.

- Connell, R. W. 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Cossman, B., and J. Fudge, eds. 2002. Feminization, Privatization and the Law: The Challenge of Feminism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Cranford, C. 1998. “Gender and Citizenship in the Restructuring of Janitorial Work in Los Angeles.” Gender Issues, Vol. 16, No. 4, 25.

- DasGupta, T. 1996. Racism and Paid Work. Toronto: Garamond Press.

- Duffy, A., and N. Pupo. 1992. Part-time Paradox. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- Economic Council of Canada. 1990. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: Employment in the Service Economy. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services.

- Eichler, M. 1997. Family Shifts, Policies and Gender Equality. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press.

- Fraser, N. 1997. Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition. London: Routledge.

- Fudge, J. 1991. Labour Law’s Little Sister: The Employment Standards Act and the Feminization of Labour. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- Fudge, J., and L. F. Vosko. 2001a. “Gender, Segmentation and the Standard Employment Relationship in Canadian Labour Law and Policy.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, Vol. 22, No. 2, 271.

- Fudge, J., and L. F. Vosko. 2001b. “By Whose Standards? Re-Regulating the Canadian Labour Market.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, Vol. 22, No. 3, 327.

- Fudge, J., E. Tucker and L. F. Vosko. 2003. “Employee or Independent Contractor? Charting the Legal Significance of the Distinction in Canada.” Canadian Labour and Employment Law Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2, 193–230.

- Hughes, K. 1999. “Gender and Self-employment in Canada: Assessing Trends and Policy Implications.” CPRN Study No. W/04. Changing Employment Relationships Series. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks.

- Human Resources and Development Canada (HRDC). 1994. Improving Social Security in Canada: A Discussion Paper. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services.

- James, A., D. Grant and C. Cranford. 2000. “Moving Up but How Far? African American Women and Economic Restructuring in Los Angeles.” Sociological Perspectives, Vol. 43, No. 3, 399.

- Jenson, J. 1996. “Part-time Employment and Women: A Range of Strategies.” Rethinking Restructuring: Gender and Change in Canada. I. Bakker, ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 92.

- Krahn, H. 1991. “Non-standard Work Arrangements.” Perspectives on Labour and Income, Winter, 35.

- Krahn, H. 1995. “Non-standard Work on the Rise.” Perspectives on Labour and Income, Winter, 35.

- Lerner, G. 1997. History Matters: Life and Thought. New York: Oxford.

- Lowe, G., G. Schellenberg and K. Davidman. 1999. “Rethinking Employment Relationships.” CPRN Discussion Paper No. W/05. Changing Employment Relationships Series. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks.

- Luxton, M., and J. Corman. 2001. Getting By in Hard Times: Gendered Labour at Home and on the Job. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Mayer, F. 1996. “Temps Partiel et Précarité.” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 51, No. 3, 524.

- Muckenberger, U. 1989. “Non-standard Forms of Employment in the Federal Republic of Germany: The Role and Effectiveness of the State.” Precarious Employment in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. G. Rodgers and S. Rodgers, eds. Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies, 227.

- Rodgers, G., and J. Rodgers, eds. 1989. Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies.

- Rodgers, G. 1989. “Precarious Employment in Western Europe: The State of the Debate.” Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. G. Rodgers and J. Rodgers, eds. Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies.

- Schellenberg, G., and C. Clark. 1996. Temporary Employment in Canada: Profiles, Patterns and Policy Considerations. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development.

- Scott, J. 1986. “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” American Historical Review, Vol. 93, 1053–1073.

- Silver, H. 1992. “Social Exclusion and Social Solidarity: Three Paradigms.” International Labour Review, Vol. 133, No. 5/6, 531.

- Spalter-Roth, R., and H. Hartmann. 1998. “Gauging the Consequences for Gender Relations, Pay Equity and the Public Purse.” Contingent Work: Employment Relations in Transition. K. Barker and K. Christensen, eds. Ithaca, N.Y. : Cornell University Press, 69.

- Vallée, G. 1999. “Pluralité des Statuts de Travail et Protection des Droits de la Personne: Quel Rôle pour le Droit du Travail?” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 54, No. 2, 277.

- Vosko, L. F. 1997. “Legitimizing the Triangular Employment Relationship: Emerging International Labour Standards from a Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, Vol. 19, Fall, 43.

- Vosko, L. F. 2000. Temporary Work: The Gendered Rise of a Precarious Employment Relationship. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Vosko, L. F. 2002. Rethinking Feminization: Gendered Precariousness in the Canadian Labour Market and the Crisis in Social Reproduction. 18th Annual Robarts Lecture, York University, Toronto: Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies, York University, April 11.

- Vosko, L. F. 2003. “Gender Differentiation and the Standard/Non-Standard Employment Distinction in Canada, 1945 to the Present.” Social Differentiation in Canada. J. Danielle, ed. Toronto and Montreal: University of Toronto Press/University of Montreal Press, 25.

- Vosko, L. F., N. Zukewich and C. Cranford. 2003. “Beyond Non-standard Work: A New Typology of Employment.” Perspectives on Labour and Income. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Fall.

- Women in Canada. 2001. Work Chapter Updates. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- Zeytinoglu, I. U., and J. K. Muteshi. 1999. “Gender, Race and Class Dimensions of Nonstandard Work.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 55, No. 1, 133.

List of figures

Figure 1

Typologie of Mutually Exclusive Employment Forms, Canada 2001

Figure 2

Women’s Share of Employment Forms, Canada 2001

List of tables

Table 1

Mutually Exclusive Employment Forms for Women and Men, Canada 1989 - 2001

1 Total Employment ages 15 and over. Numbers rounded to the nearest thousand. LFS estimates include unpaid family workers

– Indicates sample size too small to yield estimate; ^ indicates high sampling variablility (coefficient of variation between 16.6% and 33.3%). Estimates to be used with caution.

Table 2

A Continuum of Precarious Wage Work, Canada 2001

Table 3

Indicators of Precarious Wage Work for Women and Men, Canada 2001

1 Employees ages 15 and over. Numbers rounded to the nearest thousand.

* Women are statistically different from men of the same form and age group at the .05 level; wage ratios are reported only when significant difference.

^ Totals for part-time permanent and part-time temporary employees are misleading due to the different sex composition across the age groups. Most male part-time workers are 15–24, while large number of women part-time employees are 25–54. Since women aged 25–54 earn much more than men aged 15–24, the total wages of women are larger than the total wages of men despite the fact that men earn more in each age group.

– Indicates sample size too small to yield estimate.

Table 4

Wage Precariousness Relative to Full-time Permanent Men, Canada 2001

10.7202/051115ar

10.7202/051115ar