Abstracts

Abstract

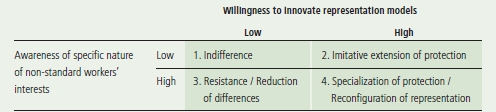

This paper aims to contribute to our understanding of how the representation gap in micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in nine countries can be closed through a mapping exercise (both horizontal and vertical). The study draws on peripheral workers in MSEs predominantly from countries on the periphery of the global economy. The assumption underlying the research is that the failure of traditional industrial relations actors, especially trade unions, to respond to the representation gap has created the space and the need for new actors to fill the gap. We identify a number of dimensions in trade union responses to non-standard employment relations and focus on their awareness of the specific nature of non-standard workers’ interests and their willingness to innovate with representation models.

The paper identifies four main responses by trade unions to non-standard employees. The first response is where trade unions are indifferent to workers in MSEs as they are seen as marginal and unorganizable. Secondly, there are trade unions that are very much aware of the need to revise and revitalize their representation strategies, but they respond by attempting to extend existing forms of representation. Thirdly there are those who believe that non-standard employment should be resisted. The fourth, and most interesting response, is where unions create specific kinds of representation and protection for the new forms of employment.

While there were positive outcomes both individually and organizationally from this mapping exercise, as an organizational tool designed to recruit members into the union, mapping is limited. In five of the nine case studies peripheral workers were recruited into a union or worker association. The paper confirms the existence of new actors in employment relations in developing countries. In particular the emergence of NGOs and community based worker associations and co-operatives have been identified as crucial intermediaries in developing new forms of workplace organization.

Keywords:

- trade unions,

- representation gap,

- mapping,

- micro and small enterprises,

- non-standard employment

Résumé

Cet article identifie quatre réponses principales fournies par les syndicats eu égard aux emplois atypiques. La première est l’indifférence des syndicats face aux travailleurs des MPE, les percevant comme marginaux et non susceptibles d’être organisés. La deuxième est la reconnaissance par les syndicats du besoin de réviser et de revitaliser leurs stratégies de représentation, tout en poursuivant les formes existantes de représentation. La troisième est la croyance qu’il faille résister à l’emploi atypique. Finalement, la réponse la plus intéressante est la création de formes spécifiques de représentation et de protection pour ces nouveaux types d’emploi.

Bien qu’il existe des résultats positifs, tant au plan individuel qu’organisationnel, à l’exercice de cartographie comme outil organisationnel destiné à recruter de nouveaux membres dans les syndicats, tel outil a des limites. Alors que dans cinq des neuf pays étudiés, des travailleurs périphériques ont été recrutés par un syndicat ou une association de travailleurs, le résultat de ces recrutements dépend de plusieurs variables. Cet article confirme cependant l’existence de nouveaux acteurs dans les relations d’emploi dans les pays en développement, notamment des ONG, des associations communautaires de travailleurs et des coopératives qui agissent comme intermédiaires importants dans le développement de nouvelles formes d’organisation du travail.

Mots-clés :

- syndicats,

- écart de représentation,

- cartographie,

- MPE,

- emploi atypique

Resumen

Este documento intenta contribuir a la comprensión de cómo se puede cerrar la brecha de representación en las micro y pequeñas empresas (MPEs) de nueve países y esto, mediante un ejercicio de mapeo (horizontal y vertical). Este estudio se basa en los trabajadores periféricos de las MPEs predominantemente de países de la periferia de la economía global. La hipótesis subyacente de esta investigación es que la incapacidad de los actores tradicionales de las relaciones laborales, especialmente de los sindicatos, para reaccionar ante la brecha de representación, ha creado el espacio y la necesidad para que nuevos actores cubran dicho vacío. Se identifican ciertas dimensiones en las respuestas sindicales frente a las relaciones de empleo atípicas y se pone énfasis en su percepción de la naturaleza específica de los intereses de los trabajadores atípicos y su voluntad para innovar los modelos de representación.

El documento identifica cuatro principales respuestas sindicales frente a los empleados atípicos. La primera respuesta es aquella donde los sindicatos son indiferentes a los trabajadores de las MPEs puesto que ellos son vistos como marginales y no organizables. En segundo lugar, se encuentran los sindicatos que son más conscientes de la necesidad de revisar y revitalizar sus estrategias de representación pero cuya respuesta es intentar de ampliar las formas existentes de representación. En tercer lugar están los sindicatos que creen que el empleo atípico debe ser contrarrestado. En cuarto lugar, y es la respuesta más interesante, es cuando los sindicatos crean tipos de representación y de protección específicos a las nuevas formas de empleo.

A pesar que con este ejercicio de mapeo, utilizado como un instrumento organizacional para reclutar miembros para el sindicato, se obtuvo resultados positives a nivel individual y organizacional, se observan también los límites del mapeo. En cinco de los nueve casos estudiados, trabajadores periféricos fueron reclutados en el sindicato o en la asociación laboral. El estudio confirma la existencia de nuevos actores en las relaciones laborales en los países en desarrollo. En particular, la emergencia de ONGs y de asociaciones laborales de base comunitaria y de cooperativas fue identificada como intermediarios cruciales en el desarrollo de nuevas formas de organización en el lugar de trabajo.

Palabras clave:

- sindicatos,

- brecha de representación,

- micro y pequeña empresas,

- empleo atípico

Article body

Introduction

The process of increasing informalization of the labour market is creating a gap between trade unions and a growing number of workers who have no forms of collective representation at their places of work. This has been labelled the Representation Gap and this is “the percentage of workers who desire union representation but who currently do not have access, primarily because they are located in workplaces without trade union recognition” (Heery, 2009: 352). In part this gap is the result of a trend towards the decentralization of production and the accompanying outsourcing of workers to a third party (Standing, 2009: 73-77). In other cases, it has arisen from the trend towards casualization, part-time and temporary employment relationships (Webster, Bezuidenhout and Lambert, 2008: 36-50). It is sometimes the result of retrenchment of workers in the face of hyper international competition and the drive to cut labour costs (Moody, 1997). The result of these processes is a growing number of workers engaging in survival type activities in micro and small enterprises (Bhowmik, 2010). In particular, workers in these workplaces have no form of collective representation (Webster et al., 2008: 4).

Theoretical Framework

The assumption underlying our research is that the failure of traditional industrial relations actors to respond to the representation gap has created the space and the need for new actors to fill the gap. These actors, such as NGOs, global union federations and social movements, may not be new but they are playing a different role in shaping employment relations at the workplace level. In some contexts, these actors interact and permeate each other’s sites and spatial boundaries in acknowledgement of each other and to complement each other’s resource “capacity constraints” (Cooke, 2010). The emerging role of these new actors has been documented in a number of studies in the North (Heery and Frege, 2006). We chose to focus on the Global South, as it is here where the representation gap is greatest.

We took as our point of departure research undertaken in Europe on the challenge faced by trade unions by non-standard employment relations. In this research, Regalia (2006) identified two dimensions to union responses. The first dimension is determined by the degree of awareness of the specific nature of the interests of non-standard employees and the second is the willingness of trade unions to innovate with representation models (Regalia, 2006).

Using this two dimensional matrix, we identified a set of questions in which union responses to the representation of non-standard workers can be located. The first set of questions related to union awareness of the nature of working conditions, the profile of MSE workers and the problems they face in their work environment. The second set of questions related to the willingness of the union to represent these workers. This included their past record of attempts at organizing MSE workers and the forms of representation introduced for MSE workers. This is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Union Awareness and Representation of Non-Standard Workers

However, there are other important dimensions that influence whether a trade union will organize non-standard workers and which are ignored by Regalia (2006). We identify at least four additional dimensions. Firstly, whether there is a culture of unionization of MSEs, or not (Illessy et al., 2007). Secondly, whether there are labour laws that facilitate unionization of MSEs, and whether these laws are enforced, or not (Xhafa, 2007). Thirdly, whether the union, after undertaking a cost benefit calculation, sees a gain in members after the effort and expense of organizing non-standard workers. This is crucial as workers in MSEs are very small in numbers and scattered geographically (Bennett, 2002). Fourthly, the type of work and the sector in which MSEs operate is important. If workers are producing goods or services that involve them in global production chains, their bargaining leverage is potentially stronger (Silver, 2003). We incorporate these dimensions into our research findings detailed later in this paper.

Mapping as an Organizational Tool and Research Design

For Burchielli, Buttigieg and Delaney (2008) mapping had proved useful in overcoming the isolation and the lack of worker identity experienced by home-workers in their study. In 2000, Home Workers Worldwide (HWW) secured funding to coordinate a home-workers’ mapping programme over a three year period in fourteen developing and transitional countries. The HWW believed that a mapping programme could improve home-working conditions by developing and strengthening organizing at the grassroots level, as well as improving the HWWs capacity to advocate change in their working conditions at the international level.

The HWW mapping programme used a “mapping pack that provided a guide to the research mapping process” (Burchielli et al., 2008: 169). There are two ways of conducting mapping, namely horizontal (HM) and vertical (VM) mapping. HM refers to the method used to document and identify the characteristics of the worker, their location and industry sector, by contacting individuals in their homes or communities. HM focuses on gathering data on demographic characteristics of workers, their home situation, their work processes, their employment relationships, payment amounts, processes and the problems and issues that they face. In contrast, vertical mapping (VM) refers to a process that identifies the chain of production, linking home-workers, subcontractors, intermediaries, buyers and brand owners (Burchielli et al., 2008).

The successful mapping programme run by HWW persuaded us to adopt a similar method in attempting to identify strategies for closing the representation gap amongst MSEs in the nine countries under study detailed in Table 1 below. The nine countries were selected by trade unionists who are alumni of the Global Labour University’s (GLU) Masters programme on “Labour Policy and Globalization.” GLU is a network of universities, trade unions, research institutes, NGOs and foundations, designed to strengthen the intellectual and strategic capacity of unions to respond to the challenge of globalization. A workshop of trade unionists from the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), GLU students and alumni was held in Johannesburg in June 2008. Participants were asked to identify sectors where there are large numbers of MSEs and explore ways in which trade unionists could “map” these workers in order to organize them. It became clear that mapping would be a feasible way of locating MSE workers (Webster et al., 2008: 60). In a follow-up workshop in Berlin in September 2008 GLU alumni involved in this project selected the sectors where it was thought organization was possible.

We decided to test the mapping model as a tool for organizing purposes. We designed a seven step process in which the researchers would locate those MSE workers who are often invisible, working from home or in small micro enterprises. Through the mapping process, we would make them aware of their identity as workers and their collective interests. Through the interviews and workshops, MSE workers would begin to frame their sense of injustice in ways that could enable organizing. Known as mobilization theory, this approach provides an explanation for individual participation in collective action and organization. Worker mobilization identifies collective interests; it is achieved through the promotion of injustice frames – largely generated by leaders (Kelly, 1998). It is consistent with the organizing model approach that has been adopted in many unions in industrialized countries to increase and promote active membership (Frege and Kelly, 2004). This approach is particularly applicable to workers in MSEs where work is often informal and non-standard – these workers, we hypothesized, stand to benefit from the process of mapping.

In this study we explored two principal research questions. Firstly the extent to which mapping is an effective capacity building and organizational tool to close the representational gap and secondly, the extent to which the mapping exercise reveals the existence of new actors in employment relations.

The research of MSE workers was conducted over a large range of industries and types of work situations in nine countries as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1

Countries, Industries and Types of Work in MSEs

The study commenced in October 2008 and each researcher was tasked with a range of activities (see Table 2 for the tasks). The researchers had to act as coordinators for the research circles created. Simultaneously the researchers carried out a vertical mapping exercise where they had to research the supply chain of the targeted sector, drawing on the work of Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon (2005) in this regard. To facilitate this, the researchers made use of a questionnaire as a guide but also to access initial information.

Research Findings from the Mapping Process

We grouped the data regarding the trade union responses to the mapping process in the nine countries into four themes:

Indifference

In the first union response, moto-couriers in Istanbul, Turkey, were marginalized by the unions. Due to the nature of their work, unions believe that these workers either do not warrant trade union intervention or the nature of their work makes it virtually impossible for them to be successfully organized into a union. We have categorized this response in Turkey as one of indifference.[1]

The researchers convened a research circle amongst moto-couriers in Istanbul and a training workshop was held. However, no plan of action with the trade union was produced. Moto-couriers are under continuous pressure to meet tight deadlines and were constantly racing against time to complete their orders. The economic crisis has increased the competition between moto-couriers. It is a highly mobile sector and it was initially thought that this would make the research difficult to conduct as the moto-couriers may not have the time to answer the research questions. However, the economic crisis helped to alleviate this concern as many moto-couriers had to wait for orders due to the reduction in demand for their services. Interviews were conducted at meeting places under a bridge or motorway, fondly referred to as “call centres.”

The lack of interest by unions to organize moto-couriers can be attributed to two major factors. Firstly, the industry has no legal definition although unions in the transport sector are entitled to organize these workers. There are two authorized transport workers’ unions in Turkey, namely Tum-Tis affiliated to Turk-Is Confederation and Nakliyat-Is, affiliated to DISK Confederation.

Secondly, moto-couriering does not require much skill, but the couriers said they would welcome unions as they feel that this is the only way that they can improve their conditions. Although the moto-couriers are willing to be organized, the unions seem indifferent to their needs. One of the two established unions, Turk-Is/Tum-Tis has not initiated organizational programmes amongst moto-couriers and point to the difficulties of organizing in such a mobile sector. However this lack of interest can also be attributed to the union’s incapacity to assemble the number of activists needed to organize moto-couriers. Another union, DISK/Nakliyat-Is, had been more responsive in the past to these workers but has abandoned any attempt to organize moto-couriers. The president of the union concluded that their previous attempts at organization failed due to the mobile nature of the workers in the sector. The union feels that it has lost the contacts that they had established.

Imitative Extension of Protection

In the second union response – in South Africa, Ukraine and South Korea – trade unions were more aware of the need to revise and revitalize their representation strategies in response to non-standard employment, but they undervalued the specificity of these new forms of employment. As a result they responded by attempting to bring these atypical workers into the ambit of existing representation in order to secure for them similar protection to those in standard employment. These strategies led to flexible arrangements at enterprise and sectoral levels.

In South Africa,[2] the study focused on the Cut-Make-and-Trim (CMT) MSE clothing workers in the Fashion District in the Inner City of Johannesburg. Although contact and discussions took place between the researchers, the head office and local branch of the union, no union endorsed plan of action emerged.

A research circle of four MSE workers in the CMTs was formed with the assistance of the union for the sector, the Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers Union (SACTWU). This circle of researchers conducted the horizontal mapping exercise, interviewing their fellow MSE workers and using the questionnaire to gather the data on this group of workers.

Unionization in the clothing and textiles industries in South Africa has been fairly successful. The reason can be attributed to two major factors. First, the industry is an established one and SACTWU and its predecessor have organized workers since the 1930s (Bennett, 2002). In a report on SACTWU’s attempt to organize home-workers in Mitchells Plain in Cape Town in the late nineties, Bennett (2002) concluded that the union’s attempt to organize informal sector workers failed because the union relied on “conventional trade unionism forged in the formal workplace, creating shop steward structures, focusing on the workplace, and establishing a negotiated relationship with the direct employer, instead of assessing where the real power these workers possessed resided” (Bennett, 2002: 15). For Bennett (2002), the power lies in the formal sector originators of the clothing orders. The downsizing measures embarked on by some South African firms in the nineties have also resulted in the union developing bargaining that “seeks to balance improved wages and conditions with job protection” (Budlender, 2009: 40).

Secondly, the industry is labour intensive and usually requires less skilled workers who are predominantly women. These workers also have grievances in both their private and public spheres and so tend to look to unions to restore their power. This presents a good opportunity for SACTWU to close the representation gap in MSEs in the industry.

The results of the South African study revealed that six of the MSE workers interviewed actually belonged to a union. However, seven did not belong but they indicated that they would consider union representation if it meant better working conditions and protection from the employer (possibly meaning minimizing the threat of unfair dismissal). The participants were concerned specifically with receiving employment benefits such as medical cover, a safe working environment and better remuneration.

In Korea,[3] the mapping exercise was carried out with MSE workers in the chemical, metal and printing sectors, as well as amongst a group of self-employed workers. The Korean financial crisis in 1997 resulted in a decrease in the number of jobs in large enterprises whilst the numbers of jobs in MSEs has increased (Webster et al., 2008: 12). The growth in the number of MSEs has been accompanied by an increase in what Koreans call “irregular” work. In addition, a high proportion of workers in MSEs are excluded from national pensions, health insurance, unemployment insurance and a retirement allowance (Webster et al., 2008: 12-14).

The researcher in Korea organized a workshop where the research circle members were trained in the technique of interviewing. However no plan of action, endorsed by a union, emerged. Interviews were carried out amongst MSE workers who were threatened with retrenchment and found themselves in a precarious situation vis-à-vis their wages, which had not been paid.

MSEs pose a number of organizational challenges for unions in Korea. Firstly the micro enterprises, that is those who employ four or less employees, are exempt from the key provisions of the Labour Standards Act (Webster et al., 2008: 24). There is also a lack of enforcement of the law that requires employers to pay extra for night work, for example. Secondly, the employers have anti-union attitudes, “If they join the trade union, there are the possibilities of dismissal by the owner,” as one worker said in an interview. Thirdly, the self employed are the most vulnerable but they cannot join a union.

The study in the Ukraine[4] focused on the retail sector in the leading trading centre, Donetsk. The sector employs large numbers of low paid employees, working frequently in informal employment relationships and under harsh conditions. No plan of action was developed with the union. A research team of six researchers was formed drawn from MSE workers in the retail sector. A workshop was held at the offices of the Independent Trade Union of Miners of Ukraine in December 2008. At the workshop the research team was informed of the aims of the project, a target group of workers was identified and the researchers were trained in interview techniques.

Although an informal economy existed in the former Soviet Union, it expanded rapidly post-1991. Thiessen (2001) claims that there is a total of over 7 million workers working in MSEs in the Ukraine and registered micro enterprises (that is those employing one to five employees) constitute only over a third (37.6%) of this total. Almost two-thirds (62.3%) of workers are employed informally. Recently the unions have begun to address the situation of these informal and unprotected MSE workers (Glovackas, 2005). Labour legislation covers enterprises irrespective of their size, although some provisions exclude informal economy workers. The labour legislation and the Labour Codes were inherited from the pro-worker socialist traditions (dating back to 1971) and guarantee a broad scope of rights to workers and to their unions. The strategy of the unions is to extend protection to informal workers. However, there is weak enforcement, insignificant sanctions for violations, and low legal awareness amongst workers. Labour inspectorates are understaffed and under-resourced and have only recently been given the right to call on enterprises without prior notice.

Resistance/Reduction of Differences

In the third dimension, trade unions see flexible work arrangements as a potential threat to the employment conditions of their members as they produce workers with interests that may be different from those in standard employment relationships. From this perspective, non-standard employment should be combated and resisted. Call centre workers in Brazil fit into this category.

A horizontal mapping exercise was undertaken amongst workers employed in banking sector call centres in MSEs in Brazil.[5] The target population was MSE workers in the Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo area where the majority of call centres in Brazil are concentrated. A core group of six researchers was established followed by a training workshop. The research circle administered the questionnaire to eighteen MSE workers.

Unionization in Brazilian call centres is infrequent. The explanation for this lies not only in the high turnover of call centre workers, but also in union hostility towards them and a lack of a tradition of unionization amongst call centre workers. Female workers are dominant in this particular sector and are prone to a variety of gender related grievances in the workplace. In Brazil, enterprises below a certain threshold size are exempted from the general labour laws and have to comply with a separate or parallel labour law regime, the Laws of Micro Enterprises and Small Companies of 1999. However most MSE employers do not follow these laws and this has become more frequent following the outsourcing of work in the nineties (Webster et al., 2008: 22). In established banking services, outsourced employees do not join the Banking Workers’ Union.

The mapping exercise allowed researchers to obtain demographic data on the call centre workers and present the results to the unions. This softened the unions’ resistance and opened up space for organization. A plan of action was developed by the Rio de Janeiro Banking Workers’ Trade Union (SEEB Rio) and Telephone Operators’ Union (Sinttel RJ).

Reconfiguration of Representation

The final, and most significant union response, is that depicted in the fourth quadrant (see Figure 1), where unions not only show a high degree of willingness to change their representation and organizational strategies, but also show awareness of the distinctive nature of these new forms of employment. They realize that they cannot simply ignore or oppose these new forms of employment. Nor can they simply resort to incorporating these workers into the current system of representation. What is required from this perspective is the creation of specific kinds of representation and protection for the new forms of employment, particularly those more marginal to enterprises, such as home workers or those in self employment. Four examples of the reconfiguration of representation emerged in our research and these were in India, Japan, Nigeria and the Philippines.

In India,[6] the study focused on home workers and MSEs involved in garment production in the Dharavi area of Mumbai (known as Asia’s largest slum). Historically Mumbai was the centre of the large scale factory production of textiles with an estimated 150,000 workers in the seventies (Sawant, 2010). In 1981 a nine month long strike took place in the mills. The union was defeated and production was decentralized and relocated to “backward areas” (Sawant, 2010).

A research circle was established and each member interviewed ten to fifteen MSE workers. Three of the five research assistants are members of a union known as “LEARN Mahila Kamgaar Sanghatana” [LEARN Women Workers’ Union]. The union was initiated by an NGO working amongst these informal garment workers called “Labour Education and Research Network” (LEARN). The mapping process enabled the researchers concerned to gather socio-economic information on MSE workers working from home in Dharavi, their grievances and the issues around which unionization of these workers would be possible.

Most of the respondents felt that unionization would be a positive step in addressing their grievances. One woman spoke of how the union had been able to increase her income from two rupees to five rupees per garment. Some of the key issues which were raised were the need for a fair wage, decent working conditions and regulated time for working. The women also raised the issue of verbal sexual abuse.

The horizontal mapping process enabled the research assistants to reach a large number of workers involved in the garment sector MSEs and to enroll them into membership of their women-only worker union (altogether seventy questionnaires were completed). Not only was the mapping exercise successful in recruiting new members but the mapping exercise also drew men into a women’s union. This resulted in the formation of a union called “LEARN Garment and Allied Workers Union” in which men and women are members. They have an office in the heart of Dharavi where they meet regularly.

In Japan,[7] the Federation of Workers’ Union of the Burmese Citizens (FWUBC) was selected for study. The FWUBC is an individual-based union, not an enterprise union. The number of individual unions based in the community has been increasing in Japan. They are called “community unions” and target young workers, women workers and workers employed by agency or labour brokers. However, the members of the FWUBC are Burmese and the aim is to organize Burmese workers in Japan and expose human rights abuses in Burma. It is supported by the Japanese Trade Union Confederation and is affiliated to the National Centre of Free Trade Unions of Burma. The majority of the members of FWUBC work in restaurants in Tokyo and in the surrounding areas. It is estimated that there are about 10,000 establishments in the restaurant sector in Tokyo. Almost all (96%) of these establishments employ less than twenty nine workers and over three-quarters (76%) employ less than nine workers. Thus, the restaurant sector in Tokyo is dominated by MSEs.

At the first workshop researchers were trained in the use of interviewing through role playing. At the second workshop the results of the research were reported on, the data analyzed and an action plan developed with the union. The data gathered from the horizontal mapping exercise revealed that MSE workers identified the precarious nature of their work, their long hours (they work an average of nine and a half hours per day for five to six days a week) and their below the minimum wage rate wages as their main grievances. In addition, over two thirds (68%) were part-time workers, and almost a fifth (16%) were temporary agency workers and twelve percent (12%) trainees. They were, in general, positive about joining a union. Examples emerged in the course of the interviews where workers had made demands, such as legal assistance over dismissals, employment contracts and work permits, which were successfully resolved through the intervention of the union.

In 2001 it was estimated that there were 6.49 million non-agricultural micro enterprises employing 8.97 million workers in Nigeria (Webster et al., 2008: 15). The typical micro enterprise is operated by a sole proprietor or manager assisted mainly by unpaid family members and occasional paid employees, or “apprentices.” For their case study, the researchers[8] in Nigeria focused on the Automobile Repair and Part Selling Sector in Abuja, Nigeria (Apo Automobile and Technical Site), as three co-researchers involved in the project are executive members of an association called the National Automobile and Technical Association or NATA. This informal economy association has a national structure and an executive body. Subsequently a research circle of five persons was established and a training workshop held with three persons identified in the sector as co-researchers and the other two as lead researchers. At the meeting, a research circle was agreed upon as well as the modalities to engage in the project and the respondents were identified. The target population was twenty-five MSEs’ workers working within the Apo Automobile and Technical Site in Abuja. The exercise started as scheduled but was delayed due to the slow response rate as the MSE workers’ time was constrained due to the fact that in December, customers preparing to travel during the festive season needed to have their cars repaired. However, the Automobile Sector of the Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC) have now identified members of NATA who they have found suitable for unionization and have adopted what is termed “Stand Alone Unionization.” This entails that, instead of merging with the existing transport union the informal association (NATA) which already has a presence amongst the MSEs in the automobile sector, is registered independently as a trade union. The Congress and its affiliates have agreed to assist NATA with the training of organizers, the production of a union constitution, formal registration as well as raising the consciousness of workers about unionism. At the policy level, the NLC proposed that the NATA as a union be affiliated to the NLC and accorded the same rights and privileges as an industrial union.

Micro and small enterprises are widespread in the Philippines[9] and economically account for the vast majority (99.2%) of all establishments and employ almost two-thirds (62%) of employees (Webster et al., 2008: 16). The Philippines has a weak record of labour standards compliance with only 183 inspectors covering over 815,000 enterprises. The most commonly violated labour standards are non-compliance to minimum wages, absence of safety committees, non-registration of establishments, non-submission of accident reports and non-payment or underpayment of holiday pay. The three person Philippine-research team chose to do a case study of MSEs in the garment sector in Dasmarinas, Cavite, a province adjacent to Manila where a large export processing zone is located. A plan of action was drawn up with the union.

A research circle was drawn from seven currently employed and unemployed MSE workers. They attended a workshop at one of the homes of a former sewer-turned micro garment business contractor. The business was not yet in operation at the time of the research but the garage-turned-workshop served as a hub for ten workers living around the area who were ready for dispatch when work began. The workshop was very informal. The researchers explained the purpose of the research to the MSE workers and then role-played the questions on the questionnaire with the MSE workers so that they would be familiar with the interviews that they would be conducting.

The horizontal mapping survey results for the sample of twenty-five micro and small enterprise garment workers indicated that there is a willingness to join a union, especially amongst the female respondents. However, the temporary nature of employment for a substantial number of them begs the question of whether a union for the purpose of collective bargaining is sustainable, let alone possible, under the present laws.

The Filipino study raised the question of whether an association of MSE workers would be preferable to that of a union. In the Philippines, unions may only be formed in establishments with ten or more workers. This means that micro enterprises, as they are currently defined, fail to meet the criteria. Secondly, most MSE employees only work for irregular periods, or when there is an order. This is usually a fixed term stint of five months, or when there is a spike in production orders. Under these conditions and with the existing legislation, collective bargaining is untenable as only regular workers can bargain with the employer.

To overcome the representation gap in MSEs, the researchers in the Philippines concluded that it may be more useful for unions to form workers into associations in areas where many garment factories are located. Furthermore, it was suggested that these groups could be community-based and part of their services could be employment facilitation and a support group for employees experiencing problems at work. They could also serve as information centres for training opportunities and livelihood programs. A union may take these workers under its wing, not for the purpose of bargaining for increased wages or benefits, but to facilitate training, which will increase their chances of getting better pay, and provide social welfare assistance in cases of illness or accident. Considering that many garment workers are female, day-care service may also be useful.

Another possibility considered by the researchers was to establish a garment cooperative under the workers’ association. Like other MSEs, it could serve as a subcontractor for bigger garment manufacturers. Co-operators will be the workers themselves. Start-up funding could be sourced from the Department of Labour and Employment’s grant for any registered group of distressed workers venturing into small business. This was realized when, in the course of the research, the researchers were able to help facilitate the registration of the interviewers’ group into a workers association so that they could take advantage of these opportunities.

The most useful finding in the Filipino case study is that the employment of MSE workers shifts along a formal-informal continuum. Sometimes these workers may find work in small registered garment companies that have been operating for a long time (some may have been bigger outfits in the past, but later became small firms), but at other times they are hired in informal home-based family businesses. This constant shuffling along the continuum presents certain complications for traditional unions but not so for loosely structured worker associations.

Evaluation of Trade Union Responses to Non-Standard Forms of Employment

While there will obviously be a range of contingent factors shaping local dynamics, the data gathered in these nine case studies seem to support research done in Europe on the challenge to unions of representing non-standard workers (see Regalia, 2006). From our case studies, it seems as if trade unions in Turkey have little awareness of the interests of moto-couriers. As a result unions remain indifferent to the need of MSE workers for representation (which is Quadrant 1 in Figure 2). Why trade unions seem indifferent to these workers is not clear from the case study, although the difficulties in organizing moto-couriers were identified as a key factor.

While a similar low awareness of the interests of retail workers exists in the Ukraine, and amongst workers in Korea, the response of unions to the representation gap in these two case studies has led to the extension of current forms of protection to MSEs (which is Quadrant 2). This response differs from Quadrant 1 as it views MSEs, not as marginal or unimportant, but as highly destabilizing because they produce workers with interests different from those of established enterprises. Indeed, some trade unionists in this category of response would see workers in these enterprises as unfair competition (which is Quadrant 3).

The South African response is more complex. The union, SACTWU, has a high degree of awareness of the interests of non-standard workers and MSEs and has attempted to organize home-workers, as demonstrated earlier. The current strategy of SACTWU is to extend the existing forms of representation to MSEs. We have included our case study on the clothing sector in South Africa in Quadrant 2, as the union seeks principally to bring MSEs within the existing form of representation – the bargaining council – and, as far as they can, secure for them the protection enjoyed by other workers in the industry. Yet the labour federation, COSATU’s response to the informal economy would place it in Quadrant 3, as very few of their affiliates, of which SACTWU is one, represent non-standard workers. The regulation of non-standard employees is consequently left implicitly or explicitly to the initiative of others, such as the now defunct “Self Employed Women’s Union” (SEWU) that organized street traders and home-workers in Durban, Kwa-Zulu/Natal. As a result, the dominant response in COSATU has been to rely on the state to restrict the development of new forms of employment by, inter alia, calling for the abolition of labour brokers (temporary employment agencies).

However, in the Brazilian case (which concerned banking sector call centre workers in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro), as very few workers have been recruited into the unions, the unions showed a high awareness of these non-standard workers’ interests but a low willingness to innovate representation models. We have, therefore, placed it in Quadrant 3.

In four of the case studies – the Burmese immigrant workers in Japan, the garment workers in India, the auto repair workers in Nigeria and the garment workers in the Philippines – the researchers were able to develop a plan of action with a trade union. This response is depicted in Quadrant 4 where unions come to recognize that the needs of workers in these new forms of employment cannot be ignored nor dealt with simply by resorting to an imitation of existing models of representation. Thus, in all four cases, new forms of representation have emerged outside of the established trade union movement. In Japan, Burmese immigrants set up an individual based union. In Nigeria, the auto repair workers had an informal association, NATA, already in the MSE sector. In the Philippines, a community based worker association and a co-operative was established. In India, an NGO existed amongst garment workers that led to the formation of a union.

Union awareness and representation of non-standard workers in the nine country case studies are captured in the four quadrants illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Union Awareness and Representation of Non-Standard Workers

Evaluation of the Mapping Method as an Organizational Tool: Benefits and Limitations

In all nine countries the researchers successfully conducted workshops where a research circle was formed from amongst MSE workers in the chosen sector. The members of the research circle then became the researchers and were trained in how to conduct a horizontal mapping process. In all nine cases the horizontal mapping process was completed, although it was necessary to adapt the questions to the local and sector context.

The interviewing process took longer than anticipated. It was partly due to the fact that the fieldwork period coincided with the end of the year work pressures and festivities. However from the reports received from the researchers in the nine countries it would be fair to conclude that the various activities that the workers were involved in had positive outcomes for them as individuals. The workshops, the training and the participation in the mapping process enabled them to develop new skills, increased their personal confidence and raised their consciousness as workers. We summarize the results of the mapping process in Table 2.

Table 2

Summary of the Mapping Process in the Nine Countries

As illustrated in Table 2, only researchers in the Philippines successfully conducted a vertical mapping process. Through a useful analysis of the garment supply chain, the research team showed how local suppliers, especially MSEs, are held hostage to the job orders of powerful lead firms and their largely invisible intermediaries. Orders are infrequent and there are times when months go by without work. For example, the small enterprise Saint Martin, which has forty workers (see Figure 3), was closed for three months in 2008, as there were no job orders. MSEs are part of a “captive value chain,” where suppliers are captive to much larger buyers such as Gap and Wal-Mart, who have control over price and sourcing locations (Gereffi et al., 2005). Intermediaries or traders, who have no production capability, are largely responsible for geographically spreading production around the world. They take orders from large manufacturers who sub-contract orders to factories, who then subcontract further down the line to other enterprises that are most often MSEs and to some extent home-workers. Most often, MSE workers do not know what part of the garment they are producing is meant for, where it will be heading to, and what label it is. The vertical mapping activity revealed the following supply chain for Saint Martin, a small enterprise in the Philippines and as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Supply Chain: From Brands to Small Enterprises, Philippines

One of the researchers conducting the horizontal mapping exercise worked for a microenterprise in this supply chain. This MSE was being organized into an association by a member of the research team. The Filipino researchers have reported that the workers’ association will be registered with the Department of Labour and Employment.

Although the vertical chain is difficult to research, the globalization of production has opened up opportunities for new forms of bargaining leverage. “The complicated and fragile nature of the global production system,” it is argued, “gives certain types of workers power to seriously disrupt the system, and in some instances even shut it down” (Webster, Bezuidenhout and Lambert, 2008: 12). Vertical mapping is the tool that can make visible the location of workers in the supply chain and their power to disrupt the global production chain. There are numerous examples of how this new source of power is used to disrupt production, most recently in the wave of strikes in the auto industry in South Africa. Here workers in the supply chain brought production to a standstill in the assembly plant by taking advantage of the pressures that come about from the “just-in-time” system (Mashilo, 2009).

A major limitation of our study is that not all research teams succeeded in gaining union ownership of their plan of action. How do we explain these different responses by trade unions to the challenge of representing the interests of marginal and vulnerable MSE workers? Our study qualifies the optimistic findings of the HWW study; mapping is a useful but limited way of organizing workers into trade unions. MSE workers were recruited into existing unions or associations through the mapping process in five cases in our study, namely Nigeria, Philippines, Brazil, India and Japan. Successful recruitment depends on a range of variables including whether the union, after taking a cost benefit calculation, sees a gain in members after the effort and expense of organizing non-standard workers. For example, in the case of SACTWU, the union decided that because workers in MSEs are very small in numbers and scattered geographically, it would not be cost effective to put union resources into attempting to recruit workers in MSEs. It is better, they decided, to focus on the buyers in their commodity chain.

Conclusion

It is possible for us to conclude that, while there were positive outcomes both individually and organizationally from this mapping exercise, as an organizational tool designed to recruit workers into the union, mapping is limited. Although MSE workers were recruited into the union or worker associations in five of the nine case studies, success is dependent on a range of variables. A crucial variable is the type of work undertaken and whether the MSEs are linked into a broader commodity chain. Although Japan, Brazil and Nigeria developed a plan of action and reconfigured representation, it was only in the Philippines and India that MSE workers had some potential bargaining leverage through their logistical power in the commodity chain. The result of their location in the commodity chain is that they have been able to facilitate a closing of the representation gap. What were the conditions for their success?

Two crucial conditions can be identified. Firstly, the mapping process works best where MSE workers are already organized into some form of pre-existing association, either a labour supporting NGO or a worker association that has a firm presence amongst MSE workers. Without this form of embedded solidarity, the research team struggles to find a point of entry and an informal network to engage in the mapping process. In India, for example, a labour supporting NGO, LEARN, and a union for female home-workers already existed. Indeed, it has been argued that “it is an illusion to believe that unions can either integrate or effectively organize the workers in the informal economy. Each segment of the population must find its own means of organizing that takes its point of departure from the contradictions that specifically apply to them” (Andrae and Beckman, 2010: 87). Secondly, both case studies benefitted by links with university based intellectuals developed by the Global Labour University (GLU). In the case of the Philippines, the union organizer worked with two GLU alumni from the School of Labour and Industrial Relations at the University of the Philippines. This enabled the team to undertake the only successful vertical mapping exercise in the project. In the case of India, the researchers had a link with the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai. A vertical mapping exercise has begun but, at the time of writing, it had not yet been completed.

MSE workers have minimal structural power, whether in the workplace or in the market (Silver, 2003). Horizontal mapping is a tool to recruit and establish a presence amongst MSE workers, but to become sustainable, these embryonic organizations will need to build associational power in the community through taking struggles into the public domain. Jennifer Chun calls this symbolic power, “symbolic leverage attempts to rebuild the basis of associational power for workers with weak levels of structural power and blocked access to exercising basic associational rights by winning recognition and legitimacy for their struggles” (Chun, 2009: 17). This involves redefining what it means to be a “worker” and an “employer” in the eyes of the public, rather than the law (Chun, 2009: 18). It is also aims “at restoring the dignity of and justice for socially devalued and economically marginalized workers” (Chun, 2009: 17).

While Chun uses the concept of symbolic power as a source of leverage for marginalized workers in the service sector, we would argue for the recognition of an equally powerful new source of power, logistical power. This form of power is potentially available to marginalized workers at the bottom of the supply chain in manufacturing sectors such as clothing through their leverage in these new global production chains.

This study confirms the existence of new actors in employment relations in developing countries. In particular, the emergence of NGOs and community-based worker associations and co-operatives have been identified as crucial intermediaries in developing new forms of workplace organization. Globalization has also opened up opportunities for new forms of transnational networks at various levels, including worker to worker, union to union, and between labour scholars in the newly formed Global Labour University. There is a need for more systematic investigation into the role that these new actors are beginning to play in closing the representation gap.

Appendices

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers who made excellent comments on our submission. We would also like to thank Frank Hoffer, senior researcher at ACTRAV in the ILO for initiating this project and for the GLU alumni who are acknowledged in the text.

Notes biographiques

Edward Webster is Professor Emeritus of Sociology, Society, Work and Development Institute (SWOP), University of the Witwatersrand (WITS), Johannesburg, South Africa

Christine Bishoff is Research and Projects Manager, Society, Work and Development Institute (SWOP), University of the Witwatersrand (WITS), Johannesburg, South Africa

Notes

-

[1]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Gaye Yilmaz, Tolga Toren and Nevra Akdemir.

-

[2]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Edward Webster, Christine Bischoff and Janet Munakamwe.

-

[3]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Sunghee Park.

-

[4]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Lyudmyla Volynets.

-

[5]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Juçara Portilho Lins.

-

[6]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Sharit Bhowmik and Nitin More.

-

[7]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Naoko Otani.

-

[8]

This is a summary of a report submitted by Joel Odigie and Eustace Imoyera James.

-

[9]

This is a summary of the report submitted by Melisa R. Serrano, Ramon A. Certeza and Mary Leian C. Marasigan.

References

- Andrae, Gunilla and Bjorn Beckman. 2010. “Alliances across the Formal-Informal Divide: South African Debates and Nigerian Experiences.” Africa’s Informal Workers: Collective Agency, Alliances and Transnational Organizing in Urban Africa. I. Lindell, ed. London: Zed Books, 1-16.

- Bennett, Mark. 2002. “Organizing Workers in Small Enterprises: The Experience of the Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union.” SEED Working Paper No. 33. http://www.ilo.org/empent/Whatwedo/Publications/lang--en/docName--WCMS_117699/ index.html (accessed 2 December 2010).

- Bhowmik, Sharit, ed. 2010. Street Vendors in the Global Economy. New Delhi: Routledge.

- Budlender, Debbie. 2009. “Comparative Study on Industrial Relations and Collective Bargaining: South Africa Report.” Paper presented at the Negotiating Decent Work Conference. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

- Burchielli, Rosario, Donna Buttigieg and Annie Delaney. 2008. “Organising Home-Workers: The Use of Mapping as an Organizing Tool.” Work, Employment and Society, 22 (1), 167-180.

- Cooke, Fang Lee. 2010. “The Enactment of Three New Labour Laws in China: Unintended Consequences and Emergence of New Actors in Employment Relations.” Regulating for Decent Work: Innovative Regulation as a Response to Globalization, Conference of the Regulating for Decent Work Network, 8-10 July. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Chun, Jennifer. 2009. Organizing at the Margins: The Symbolic Politics of Labor in South Korea and the United States. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press

- Frege, Carola and John Kelly, eds. 2004. Varieties of Unionism: Comparative Studies for Union Renewal. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gereffi, Gary, John Humphrey and Timothy Sturgeon. 2005. “The Governance of Global Value Chain.” Review of International Political Economy, 12 (1), 78-104.

- Glovackas, Sergejus. 2005. “The Informal Economy in Central and Eastern Europe.” Paper prepared for ITUC 10.

- Heery, Ed. 2009. “Representation Gap and the Future of Worker Representation.” Industrial Relations Journal, 40 (4), 324-336.

- Heery, Ed and Carola Frege. 2006. “New Actors in Industrial Relations.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 44 (4), 601-604.

- Illessy, Miklós, Vassil Kirov, Csaba Makó and Svetla Stoeva. 2007. “Labour Relations, Collective Bargaining and Employee Voice in SMEs in Central and Eastern Europe.” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 13 (1), 95-113.

- Kelly, John. 1998. Re-thinking Industrial Relations: Mobilization, Collectivism and Long Waves. London and New York: Routledge.

- Mashilo, Alex. 2010. Changes in Work and Production Organization in the Automotive Industry Value Chain: An Evaluation of the Responses by Labor in South Africa. Masters research report, University of the Witwatersrand: Johannesburg.

- Moody, Kim. 1997. Workers in a Lean World: Unions in the International Economy. London: Verso.

- Regalia, Ida, ed. 2006. Regulating New Forms of Employment: Local Experiments and Social Innovation in Europe. New York: Routledge.

- Sawant, S. T. 2010. Interview, January, Ambedkar Institute for Labour Studies: Mumbai.

- Silver, Beverly. 2003. Forces of Labor: Worker’s Movements and Globalization since 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Standing, Guy. 2009. Work after Globalization: Building Occupational Citizenship. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Thiessen, Ulrich. 2001. “Presumptive Taxation for Small Enterprises in Ukraine.” Mimeo.

- Webster, Edward, Andries Bezuidenhout and Robert Lambert. 2008. Grounding Globalization: Labour in the Age of Insecurity. Blackwell: Oxford.

- Webster, Edward, Christine Bischoff, Edlira Xhafa, Jo Portilho, Doreen Deane, Dan Hawkins, D. Sharit Bhowmik, Nitin More, Naoko Otani, Sunghee Park, Eustace Imoyera James, Melisa Serrano, Mary Viajar, Ramon Certeza, Gaye Yilmaz, G. Bulend Karadag, Tolga Toren, Eva Sinirlioglu and Lyudmyla Volynets. 2008. “Closing the Representation Gap in Micro and Small Enterprises.” Global Labour University. Working Paper Number 3, GLU: Germany.

- Xhafa, Edlira. 2007. Obstacles and Positive Experiences in Achieving Better Protection and Representation for Workers in Micro and Small Enterprises: A Review of Literature. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

List of figures

Figure 1

Union Awareness and Representation of Non-Standard Workers

Figure 2

Union Awareness and Representation of Non-Standard Workers

Figure 3

Supply Chain: From Brands to Small Enterprises, Philippines

List of tables

Table 1

Countries, Industries and Types of Work in MSEs

Table 2

Summary of the Mapping Process in the Nine Countries