Abstracts

Abstract

It is generally accepted that employment regulation offers mechanisms to generate orderly economic growth as well as provide for the protection of workers. Both these efficiency and equity arguments particularly pertain to developing country contexts. The evolution and impact of employment law and industrial relations institutions in large developing countries is of growing interest to western scholars, but small developing countries have been ignored. This lack of research inhibits understanding of the political economy of employment regulation in developing country contexts.

This article explores developments in labour regulation in three small developing countries in the South Pacific—Nauru, Tonga, and Papua New Guinea—that have been impacted by globalization and international labour regulation in different ways. The comparative research adopts a stakeholder analysis approach based on programs of qualitative interviews and documentary analysis.

The paper identifies a number of structural and agency constraints on the development and effective implementation of employment regulatory systems that primarily reflect political factors. These include disorganized employment relations, under-developed civil society institutions, concentration of power networks, the under-resourcing and compartmentalization of state institutions and a broader context of political change and instability. These factors, which are related to country size as well as stage of development, subvert the introduction, implementation and review of employment regulation even where efficiency and equity arguments may be accepted by policymakers. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications and need for future research.

Keywords:

- employment regulation,

- less developed countries,

- Pacific Island Countries,

- Nauru,

- Tonga,

- Papua New Guinea

Résumé

Il est généralement admis que la réglementation de l’emploi offre des mécanismes permettant de générer une croissance économique ordonnée et d’assurer la protection des travailleurs. Ces arguments d’efficacité et d’équité concernent particulièrement les contextes des pays en voie de développement. L’évolution et l’impact des lois du travail et des institutions des relations industrielles dans les grands pays de ce type intéressent de plus en plus les universitaires occidentaux, mais les petits pays ont été peu étudiés jusqu’à ce jour. Ce manque de recherche empêche de comprendre l’économie politique de la réglementation de l’emploi dans l’ensemble des pays en voie de développement.

Cet article explore les évolutions de la réglementation du travail dans trois petits pays en voie de développement du Pacifique Sud — Nauru, Tonga et Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée —, pays qui ont été touché par la mondialisation et la réglementation internationale du travail de diverses manières. Cette recherche comparative adopte une méthodologie basée sur des entretiens qualitatifs et une analyse documentaire.

Notre étude identifie un certain nombre de contraintes structurelles et bureaucratiques affectant le développement et la mise en oeuvre effective de systèmes de réglementation de l’emploi, des contraintes causées principalement par des facteurs politiques. Il s’agit notamment de relations de travail désorganisées, d’institutions de la société civile sous-développées, de concentration des réseaux de pouvoir, d’un manque de ressources et d’une compartimentation des institutions publiques, ainsi que d’un contexte plus large de changements politiques et d’instabilité. Ces facteurs, qui sont liés à la taille des pays et à leur stade de développement, sapent l’introduction, la mise en oeuvre et la révision de la réglementation de l’emploi, même lorsque les arguments d’efficacité et d’équité sont acceptés par les décideurs. L’article se termine par une discussion des implications de notre étude et la nécessité de mener de futures recherches.

Mots-clés:

- réglementation de l’emploi,

- pays en développement,

- pays insulaires,

- Pacifique Sud,

- Nauru,

- Tonga,

- Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée

Article body

Introduction

Employment law takes various forms and serves different functions. It originally developed to provide safeguards, especially for vulnerable workers, in response to the often brutal conditions of early capitalism (Weiss, 2011). The industrial and political organization of labour subsequently led to the development of broader rights-based frameworks covering collective representation, freedom from discrimination and providing for certain quasi-property rights in the job relating to dismissal and redundancy. In the modern era, labour law usually combines with other institutions of industrial relations, notably trade unions and collective bargaining, to provide systems of employment regulation. By providing for worker protection and worker rights, these frameworks endorse the 1944 Philadelphia Declaration of the ILO, that “labour is not a commodity” (Hepple, 2011).

The fundamental basis of employment regulation is equity but there are efficiency arguments in favour too (Deakin and Wilkinson, 2005). Labour productivity and economic growth are served by institutional means for the extension and orderly operation of labour markets. Regulation can therefore act as a ‘beneficial constraint’ on employers (Streeck, 1997), introducing mechanisms for the avoidance and resolution of individual and collective disputes, promoting investment in human capital and encouraging the professionalization of management (Deakin and Sarkar, 2008; Budd, 2004).

These arguments have been synthesized by the application of Amartya Sen’s (1999) capabilities framework in which development is viewed not solely in economic terms but by how material growth serves to remove barriers to human freedom. Work becomes a means for individuals to develop their capabilities in pursuit of their own subjective ‘functionings’ or goals. As Fudge (2011: 125, 128) puts it, labour regulation serves “the construction and governance of labour markets” within “a normative framework, capabilities, which allows for a plurality of goals, of which efficiency is but one”. At the individual level, these goals concerns quality of life and “the dignity of human beings at work and through work” (ILO, 1997: 3). In other words, if industrial relations is about employment regulation, employment regulation in the contemporary global economy is, or more precisely should be, about ‘decent work’ (Fudge, 2018).

Hence, in principle, employment regulation can be a constitutive force for economic and individual development as well as a corrective to some of the deleterious effects of work. This arguably applies to developing country contexts in particular. As Deakin (2011: 167) argues, the fact that the core institutions associated with employment regulation emerged out of industrialization in the West, though not implying a necessary condition, “does, however, suggest that labour law institutions are capable of contributing to economic growth and social cohesion in emerging and transitional economies”. There is thus a case to be made for labour regulation in less developed countries (LDCs) on the bases of worker protection and human rights, labour market efficiency and economic growth, and the development of individual capabilities. Such regulatory systems are also even argued to support political pluralism in these contexts, acting as “a means of promoting democracy and an effective state” (Deakin, 2011: 168).

There are, however, a number of obstacles to the introduction and implementation of labour law in developing countries. A particular issue is the size of the informal economy, which almost by definition lies outside the regulatory space. A large informal economy suppresses the perceived relevance of labour law (Bacchetta et al., 2009) and, by reducing government resources, undermines systems of labour administration and inspection (Olivier, 2013). Relatedly, civil society organizations active in labour regulation, including trade unions, are often weak in LDCs. In contrast, employers, though also often weakly organized, are likely to have a more direct influence on state policy through personal networks (including corruption) and to lobby effectively against anything that might be perceived to increase costs and reduce flexibility (Graham and Woods, 2006). States might also be reluctant to regulate employment and labour markets under the pressures of globalization and international agencies such as the IMF, WTO and World Bank (Rudra, 2008). Finally, colonial legacies might also be relevant; countries influenced by British common law and ‘voluntarist’ traditions tend to demonstrate less appetite for state intervention to regulate employers, even where there is political pluralism and a relatively advanced civil society (Cooney et al., 2009).

We can hypothesize that many of these obstacles are intensified in smaller countries, though here literature is sparse. For example, smaller LDCs are less likely to have a diversified, industrialized economy, have an under-developed civil society and be influenced by powerful interest groups from within and outside the country. Arguably, however, they are in greater need of regulation, in order to protect vulnerable workers and promote formal employment and economic development.

In recent years the ILO has paid increasing attention to these smaller LDCs for these very reasons. The changing context for the ILO is the intensification of international competition, which has increased the difficulties in securing implementation of its standards (Marginson, 2016). On the one hand, this prompted a shift to ‘soft regulation’ (Baccaro and Mele, 2012), involving “a more targeted choice of subjects” for labour standards and “greater recourse to recommendations” (ILO, 1997: 37, 49). However, it also led to a broadening of the ILO core mission from employment rights to ‘decent work’. As indicated above, the decent work concept fuses social justice and economic progress through a focus on quality of life and the development of human capabilities that deliver “better prospects for personal development and social integration” (ILO, 2014b: 1). It was incorporated as the ILO core mission through the Declaration on Social Justice for a Fair Globalization in 2008 and it is both prescriptive and universalistic. All countries should take steps to ensure adequate labour regulation to protect workers and promote higher-quality work. As a result, the work of the ILO became more relevant to LDCs as it “moved closer to identifying core labour standards with issues relating to human dignity, development and human rights” (Sankaran, 2011: 229). This shift included policies and interventions around new areas such as informal work and child labour, and involved the extension of technical and other support to smaller LDCs.

This article explores the pressures and obstacles to the development of employment regulation in three small LDCs, each of which have had technical support from the ILO in recent years. The objective is to analyze what factors might promote or impede the development of employment regulation and policy in these contexts. The research is exploratory and informed by a broad view of industrial relations as the institutional mechanisms for regulating employment in pursuit of often conflicting goals such as welfare and order (Hyman, 2009). The nature of these institutions varies substantially between countries and over time. Historically, the primary focus of academic industrial relations in the UK, and many Commonwealth countries, was collective bargaining, ever since the Webbs produced their seminal Industrial Democracy in 1897. This contrasted to continental Europe “where employment relations were subject to far more pervasive legal regulation, and collective bargaining attained far less significance” (Hyman, 2009: 33). However, as Hyman (1989) also argues, a legal and/or trade union focused view of industrial relations is likely to be partial or superficial without close attention to the fundamentals of political and economic context. This ‘political economy’ view of industrial relations, reinforced by the retreat of collective bargaining and political and economic upheaval in 1980s Britain, is echoed by the eminent Canadian labour lawyer Harry Arthurs (2011) in his analysis of the corollary challenges experienced in the discipline of labour law. As the traditional conception of labour—as a class, form of employment and organized movement—is disappearing in the west, so it becomes more obvious that “law lacks the capacity to fundamentally alter power relations. Those relations are ultimately determined not by law but by political economy” (Arthurs, 2015: 2). There are, for example, more formal labour rights in most advanced economies than ever before, yet workers are becoming more, not less, vulnerable.

All of which is to say that a focus on the economic and political factors shaping the regulation of employment, even in countries with little by way of employment law or trade unions, is a legitimate interest for industrial relations research with a ‘sociological imagination’ and a concern with what shapes work and employment in society (Elger, 2009). As Kaufman (2012: 84) reminds us, a core concern of institutional economics and “its close off-shoot” industrial relations has traditionally been with the potential for interventions such as labour law “to enhance social welfare” at a particular place and time.

This article is informed by a political economy paradigm of industrial relations research, and responds in particular to a lack of western academic interest in employment regulation in LDCs (Betcherman, 2015; Djankov and Ramalho, 2009), especially beyond “the usual suspects” of the largest developing economies in Latin America and Asia (Barry and Wilkinson, 2011: 11). Small LDCs are neglected due to their relatively limited impact on the global economy and more difficult access to data but, as Kaufman (2011: 28) notes, “also entering the picture is ethnocentrism”. Despite the arguably greater need for, and potential effect of, employment regulation in these contexts, and growing activity by agencies such as the ILO, smaller countries are ignored by employment relations scholars in part because “most writers come from a small number of advanced Western countries” (ibid.). This parochialism is unfortunate not just for the actors in such countries, but because it means we understand less about “the rising tide of globalization and its present and future impact on employment relations institutions and practices” (ibid.: 25).

The countries examined in this study are Nauru, Tonga and Papua New Guinea (PNG) which, as explained below, have qualitatively different economies and societies. Although these may be unfamiliar to many RI/IR readers, there are strong North American connections in all three cases. Until recently, Nauru’s economy depended on the export of phosphate, up to a quarter of which went to Canada (ADB, 2007). Today, hopes are pinned on the prospect of deep-sea mining for nickel, cobalt and manganese led by a Canadian company DeepGreen Metals (Davies and Doherty, 2018). The mining relationship is already profound in the case of PNG where Canadian companies such as Inmet, Placer Domer, and Barrick Gold have a large and controversial presence marked by allegations of “corruption, environmental damage and human rights violations” (Hanlon, 2014: 21). PNG is highly dependent on mining exports, which, until the recent exploitation of huge petroleum and natural gas reserves, accounted for nearly half of GDP (Imbun, 2006). In Tonga, dependency takes a different form; an estimated 39% of GDP comes from remittances by emigrants and overseas workers, more than half of which are sent from the USA (Taufatofua, 2011).

The two research questions driving the research are: 1- What is the state doing in these small LDC contexts to regulate employment, develop employment policy and/or promote an institutional framework for the conduct of industrial relations?; and 2- What are the principal barriers to this occurring?

Methods

Empirical research in small LDCs is best served by a qualitative approach given the under-researched and multi-level nature of the issues under consideration; obstacles to primary data gathering through quantitative techniques; and the need to develop deeper understandings that advance not just knowledge but also inform evidence-based policy making (Betcherman, 2014). Qualitative research is also appropriate in cross-national studies where the emphasis is on sense making and the identification of themes, issues and patterns (Cooke, Veen and Wood, 2017). Comparative research based on multiple cases is an established way to develop insights by comparison and contrast across different national contexts (Bamber, Lansbury and Wailes, 2004; Bean, 1985; Hantrais and Mange, 2007). According to Hyman (2004: 288), “a comparative perspective should be cultivated not as an optional extra but as a necessary basis for adequate understanding”. The word ‘understanding’ is telling here, as comparative analysis can be methodologically problematic (Mills et al., 2006). Difficulties concern case selection, the unit and level of analysis, construct equivalence and issues of causality, especially where populations that form an object of analytic interest are of small size. This circumscribes the generality and causality required by useful theory (Przeworski and Teune, 1970). A focus on developing understanding acknowledges these issues (Mjøset, 2006) and is fitting for exploratory research (Ragin, 1994).

The three countries under consideration in this research—Nauru, Tonga and Papua New Guinea (PNG)—are small developing countries in the South Pacific. Their selection is somewhat opportunistic, driven by a series of primary research projects commissioned of the researchers by the ILO between 2011 and 2015. These studies comprised situational analyses of employment and the labour market together with capacity assessments of the relevant ministries responsible for employment policy and regulation. However, it can be legitimate to base selection on pragmatic criteria, not simply in recognition of the practical difficulties of designing and conducting in-depth research across national boundaries (Livingstone, 2003) but also because “the particular conjuncture of labor market conditions in each place is unique... shaped by the local contexts in which they operate” (Peck, 1996: 265, 267). Every place is different, and in comparative research the concern is not with matching like with like.

In the event, the three countries share many features and challenges, yet also differ in important ways (Reilly, 2004). Typically, Polynesian countries (which include Tonga) tend to be ethnically homogeneous and demonstrate relative political and economic stability, in contrast to culturally diverse and often conflict-ridden Melanesian states (which include PNG). The latter tend to be larger, have closer proximity to markets and possess more natural resources than their Polynesian neighbours. Tonga is a small country integrated in the global economy through remittances and trade, whereas PNG is a relatively large country which is rapidly developing due to commodity exploitation. Nauru represents a third point of comparison, being a small country settled by peoples from Micronesia and Polynesia and which has known both wealth and economic crisis in recent years. Overall, the three countries resemble ‘diverse’ or ‘most different’ rather than ‘most similar’ cases (Seawright and Gerring, 2008). This form of comparative or multiple-case method is useful for generating insights and explanations, or ‘analytic generalization’, and developing an emerging research agenda from exploratory research (Yin, 2014).

The research utilized a stakeholder analysis approach which is widely employed as an exploratory research method in both management and development studies (Simmons and Lovegrove, 2005; Crosby, 1992). It is used to explore the positions of decision makers, and those likely to be affected by decisions, in the context of their interests, networks and power relations. In the policy area, these encompass representatives of international agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), ministry officials, public sector and relevant commercial organizations, and social partner and civil society groups. As is customary in stakeholder analysis, our research involved a broad program of semi-structured interviews and extensive use of documentary material.

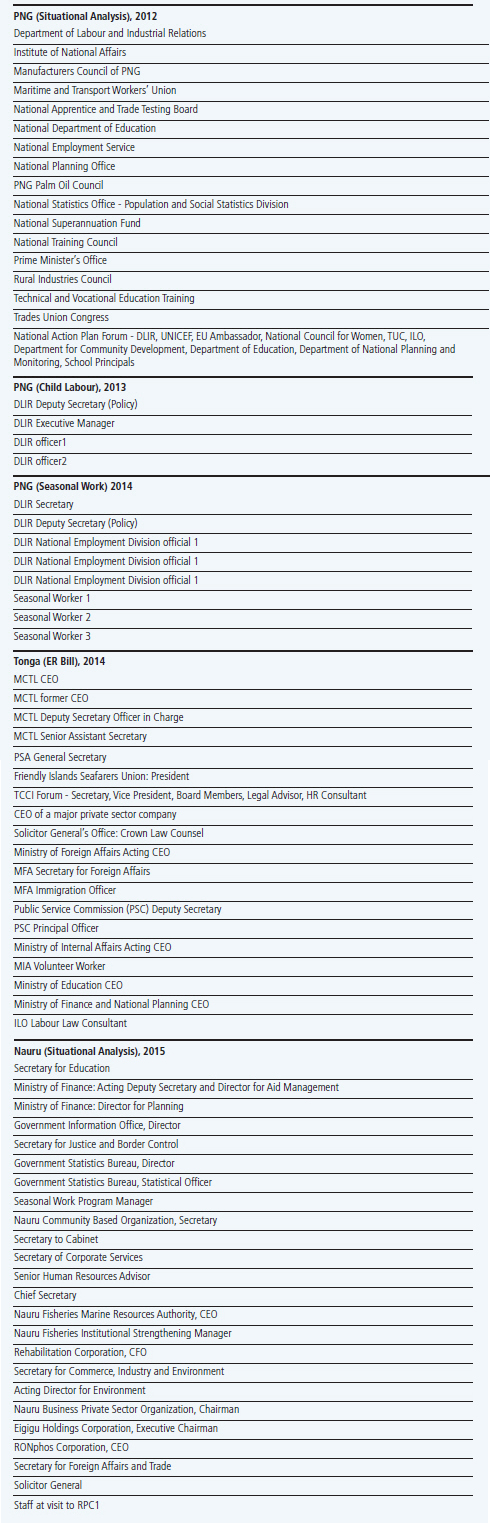

The fieldwork was conducted over a period of one week in Tonga in 2014, two week-long visits to Nauru in 2015 and a series of four visits of between three days and a week to PNG in 2012, 2013 and 2014. Prior to leaving for each research site, the researchers liaised with ILO regional and country-specific research managers, together with national Ministry of Labour representatives to develop a current and, given the exploratory nature of the research, thorough schedule of relevant informants. These included: ministerial directors, program managers and staff; senior representatives of employer organizations and trade unions; business CEOs and sector representatives; senior HR advisors; community representatives; and labour market researchers/statisticians. In some cases, ‘snowballing’ usefully occurred wherein additional interviewees were added following arrival in the country (Merriam, 2009). A total of 100 people were interviewed, comprising 30 from Nauru, 25 from Tonga and 45 from PNG, along with several ILO regional representatives (Table 1). This resulted in a comprehensive representation of employer, labour, governmental and civil society interests in Nauru and Tonga and a broad inclusion in PNG where interviews had to be restricted to the capital, Port Moresby, for practical reasons, including security.

English was the language used in each interview, being an official language of Tonga and PNG and a virtually universal second language in Nauru. Interview questions followed a semi-structured format focused on the project areas for which the researchers were commissioned by the ILO. These comprised a situational analysis of employment in PNG and Nauru; investigations into the regulation of child labour and seasonal work in PNG; and a capacity assessment of Tonga with respect to its Employment Relations Bill. Importantly, interviews were also concerned to elicit expert accounts of the broader national and local contexts for employment regulation in each case. Hence, the interview format followed a consistent approach but with additional specific questions tailored to the context under consideration. All of the interviews were conducted face-to-face at times and in locations within PNG, Tonga and Nauru that most suited the interviewees. Around 80 interviews involved the researcher and one informant; in some cases, however, a group or focus group format was used, especially to validate or extend earlier findings. Interview duration ranged from 45 minutes to two hours. Interviews were recorded where respondents were comfortable with this, otherwise contemporaneous notes were taken which were written up immediately afterwards.

Table 1

Research Participants

The documentary evidence gathered on employment and regulation in the three countries was intended to be exhaustive. It was generated from two sources: 1- desk research by the researchers prior to engaging in the interview activity, including material supplied directly from ILO and national contacts; and 2- from interviewees who supplied materials during and/or following the interviews. This literature helped to inform the focus of the interview schedules as well as contextualization and analysis of the primary data. Much of the documentary evidence consisted of original materials not in the public domain. Both the documentary and interview data were subjected to an iterative (thematic) analysis wherein: 1- extant scholarship and reports were used as an initial classification device; and 2- additional themes were surfaced from categorical aggregation of data ‘points’ in the materials themselves (Stake, 1995). In addition, drafts of the analytic output were sent to a number of informants for review to ensure accuracy and fair representation. The researchers also presented the findings to senior-level stakeholders in each country, which provided an opportunity for further feedback on the results and their interpretation.

The Three Research Contexts

Nauru is one of the world’s smallest nation states, comprising a 21 square kilometre island with a population of around 10,000. It gained independence from Australia in 1968 and benefitted from a phosphate mining boom until falling prices and exhaustion of reserves, together with mismanagement of the sovereign wealth fund, culminated in severe economic crisis at the turn of the century (Arrowsmith and Parker, 2015). Nauru provides “a striking example of the natural resource curse thesis” (Pollock, 2014: 118) by which temporary wealth retards sustainable development and then structures external dependency. The notion of a resource curse for developing countries was first proposed by Auty (1993) who observed that long-term problems often build whilst the benefits of resource exploitation are enjoyed. These include lack of development of alternative industries, under-investment in human capital and environmental degradation. The crisis in Nauru was partly mitigated by aid and the opening of an Australian-funded Regional Processing Centre (RPC) or camp for asylum seekers in 2001. The RPC closed in 2008, following a change of Australian policy, but re-opened on a larger scale in 2012.

All land in Nauru is owned by individuals and families who receive dwindling rental income from mining; a number also receive significant income from RPC rents. The decline of passive income and re-opening of the RPC means there is full employment in Nauru, dominated by the public service (1,875 employees), state-owned enterprises (SOEs; 1,107), and the RPC (800). The Nauru Private Business Sector Organization (NPBSO) reported 53 members in 2015. There are no trade unions (including in the public sector or RPC) and no employment law aside from the Public Service Act 1998, which sets out a loose framework for public service terms and conditions of employment. The Republic of Nauru is a unicameral Parliamentary democracy that joined the UN in 1999 but is one of seven member states that has not yet joined the ILO.

The Kingdom of Tonga also joined the UN in 1999 and was admitted to ILO membership in 2016. The country has a population of around 100,000 and 32,000 people in employment with around half in the formal economy, a third in informal work and nearly one in five (17%) engaged in subsistence agriculture (Ministry of Education and Training-MET, 2013). There are some 1,500 private businesses of which three quarters are sole traders (Ministry of Commerce, Tourism and Labour-MCTL, 2014). Employers typically have three or four workers, and only four per cent of firms employ more than 20 people. Three-quarters of the land is owned by the royal family and nobility, and the rest by the state, though ‘commoners’ have a right to lease land for cultivation. The landed class also own many of the major businesses.

As in Nauru, there is no employment law governing the private sector. The Trade Unions Act 1964 was never given effect so any union must register under the Incorporated Societies Act 1984 with a remit “to promote the welfare of workers and to create better understanding and cooperation between employers and employees” (Ministry of Labour, Commerce and Industries-MLCI, 2009: 18). The Public Service Association (PSA) was formed in 2005 following strikes linked to the democratization movement and there are associations for education and medical professionals. There is one ‘union’ in the private sector, for seafarers. Employers are organized through the Tonga Chamber of Commerce and Industry (TCCI). Tonga became a constitutional monarchy in 2010 in the aftermath of pro-democracy demonstrations and riots, and the government formed that year was the first in which a majority of parliamentary seats were popularly elected.

Papua New Guinea was historically a German and British colony and latterly administered by Australia until independence in 1975. The country has a population approaching seven million and subsistence agriculture is the main source of living for 85% of its inhabitants. The formal economy is dominated by large companies involved in the export of commodities such as nickel, copper, gold, palm oil, coffee, timber and a new US$19 billion liquefied natural gas project operated by ExxonMobil. Nonetheless, PNG remains one of the poorest countries in the region and receives a large volume of foreign aid, with Australia providing around 80% of support (OECD, 2011).

A legacy of the country’s links with Australia is that it has a framework of labour law informed by western practice and the ILO, which it joined in 1976. There are 73 registered trade unions and about half of wage-earners in the formal economy are members, with high density in the public sector and major industries. There is also a formal tripartite arrangement governing labour market policy. However, there are concerns that awareness, observance and enforcement of much of the regulatory framework is poor (Imbun, 2006). A process of regulatory review was renewed in 2010 with a view to updating and integrating the nine major pieces of employment legislation, but this had not happened at the time of the research.

Results: Regulatory pressures and constraints in three settings

Nauru

As indicated above, the three countries represent different degrees of regulatory articulation. Of the three, Nauru has the most under-developed employment law and labour representation, though regulation is an emerging issue due to the growth of the waged workforce and controversies around employment in the RPC:

There is nothing nationally that protects employees, and employers, in the SOEs and private businesses. Private businesses do what they like ... The courts are time consuming. That means that private-sector employees are at the mercy of the employer. We now need to develop our own employment law for the private sector to ensure fairness and consistency. But this is not a priority because the private sector is small and everyone is busy with other things. The big issue was the Centre, but that has been resolved through the negotiations process.

Senior Official, Justice

The latter comment refers to grievances raised by RPC employees. Local workers employed by the operator Transfield Services Australia (TSA) had no written contracts and complained of long hours, low pay, lack of benefits and poor training. These were taken to Members of Parliament and a petition was presented to government. As a result, a government delegation consisting of the Chief Secretary, Secretary of Justice and Senior Human Resources Advisor met with executives of TSA in Melbourne in 2014. The circumstances were opportune as the RPC contract was due for re-tendering in 2015 and the company’s reputation had already been damaged by controversies around the treatment of refugees in its care. Although this first labour protest in Nauru seemed resolved, the episode drew attention to the lack of workers’ rights and appropriate mechanisms to raise and address their concerns.

There remain, however, fundamental constraints on labour regulation relating to: 1- existing capacity; 2- political and corporate governance arrangements; and 3- a paucity of civil society institutions and labour market research. First, there is no Labour Ministry in Nauru. Responsibility falls by default to the Justice ministry, which provides legal advice to Cabinet and other ministries as well as directly delivering quarantine, immigration, corrections, business licensing and legal drafting services. These multiple responsibilities lead to capacity constraints and insufficient prioritization. Two prime examples are the protracted revisions to the National Sustainable Development Strategy (NSDS) and the Public Service Act (PSA). The NSDS was introduced in 2005 as a condition of the Pacific Regional Assistance to Nauru (PRAN) economic aid program and was required to be regularly reviewed and renewed. The first revision was in 2009 (the final year of PRAN) and stressed the need for a “conducive legislative framework” for employment (Ministry of Finance-MoF, 2013). The second revision was budgeted each year since 2012 but always deferred due to insufficient technical capacity (and urgency) following the withdrawal of specialist international assistance. The PSA has also been under review since 2013 as it is recognized as vague and outdated, omitting important areas concerning health and safety, and employment relations. As with the NSDS, reform pressures resulted from international concerns, including the appointment in 2012 of a Senior Human Resources Advisor funded through AusAID to improve the efficiency and professionalism of the public administration. Specific initiatives around job evaluation and employee development have followed, but the PSA remains in a state of suspended review.

Part of the problem in introducing more fundamental labour reform, or even good practice in HRM, was said to be the centralized nature of the Nauruan state, in which power—and patronage—is concentrated:

Nauru is a very small country with lots of networks through blood and marriage, and politics. A new government will bring in their own people, people who have campaigned for them. And ministers want their friends and relatives to have work, at all different levels. The small size of the country makes the networks even more strong than in other Pacific countries… Appointment through political or family connections impacts on performance and leadership and discipline, and donors are concerned by all of this.

Senior Official 1

One of the key problems with Heads of Department is [the Cabinet] appoint them. So they may be political appointments, and they can be there for a long time.

Senior Official 2

Similar concerns were voiced in the SOEs: « We are cautious to employ because there is a political risk. We could be sent a ‘parachutist’—a politically inspired appointment. We could be sent someone not skilled or suitable once a vacancy is identified. » (SOE Manager 1)

The SOEs are nominally corporatized but have Boards reporting directly to the relevant Minister. This reinforces political control and inhibits HRM planning and policy development:

The Act says we are an Authority but we act like a government department … Fisheries now bring in 20 million a year but we are returned one million, mainly to cover salaries (so) there is no flexibility for us to arrange our own pay scales, incentive schemes, training and development.

SOE Manager 1

We are an ‘SOE’ but we are not commercial or autonomous. We are run by the government. To the extent we might get a call from a government official—“come and do this road”— and it takes the equipment away from revenue... We need to try to change things but we are limited in our range of interventions. We can’t do creative things like gain-sharing on productivity or efficiency because we have to go to Cabinet for funding, etc. Our hands are tied.

SOE Manager 2

The development of employment policy and regulation is also hindered by political uncertainty. A triennial election cycle and absence of political parties contributes to “myriad episodes of political instability” in which “changes in government and senior officials are frequent” (Asian Development Bank-ADB, 2013: 3). With almost twenty governments over the past decade, hesitancy and inconsistency in the development and implementation of policy is systemic in the civil service as well as in the political leadership. As one Senior Official put: “We don’t have a policy framework for employment, except for the NSDS which is a long-term plan ... there is no constructive policy at present; there is a lot going on but it is ad hoc”.

Political turbulence increased after the re-opening of the RPC due to controversies over alleged human rights abuses and financial advantage (Walsh, 2016). Five MPs (from a parliament of 19 members) were suspended in 2014 for criticizing government decisions in the overseas media, and three were arrested in June 2015. There is no independent media and the under-development of civil society means there is little domestic representation, voice or lobbying to initiate reform or to hold government to account. There are no trade unions, including in the public service, and the Nauru Community Based Organization (NCBO), which was formed for consultation over environmental projects, and private-sector body NPBSO are small and under-resourced.

A final consideration is the lack of labour market research and data as this reduces the ability to identify problems and inform and progress policy development. Certainly, the Nauru Bureau of Statistics (NBS) has compiled census and Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) data to international standards, but its focus is macroeconomic statistics linked to Nauru’s applications to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group. A series of labour force and business surveys was scheduled to commence in 2017 but this was seen by the NBS as unlikely as, like other departments, it is stretched with a staffing complement of only five. The Unit also sees little stakeholder appetite for such work (NBS, 2009: 5):

The reports NBS publishes do not yet have apparent effect on national economic policy and planning, which appear to remain ad hoc and crisis driven. Effective demand and expectations for improved economic policy, planning statistics remain weak in government and in the general public.

Tonga

In Tonga pressures for regulation were more palpable in the wake of the strikes and demonstrations that accompanied democratization. An Employment Relations Bill (ERB) was drafted in 2013 modelled on regional ‘best practice’ and covering a range of issues to do with pay, working time, safety, industrial relations, equal opportunity, redundancy and dismissal. It also made provision for a tripartite Employment Relations Advisory Committee (ERAC) and a labour inspection regime. The Bill thus represented a prospective leap from a situation of zero private-sector regulation to a complete system of labour law.

The government stated that the ERB would improve efficiency and fairness in the labour market by seeking “to provide the fundamental principles of a fair labour market, rights at work and due process and protection for employment relations” as well as ensure “the improved delivery and productivity of employees to businesses” (Ministry of Information and Communications, 2013). Officials based in the Labour Division of the MCTL championed the Bill:

The private sector enjoy their hire and fire but they need to balance rights. It will help stability in employment if we create a more level playing field, and the Bill could increase efficiency in the employment relationship. Having a process to recognize employee rights means better governance of employment, and Tonga tomorrow is more civilized than Tonga yesterday.

Senior Official 1

A specific business case was that the lack of a regulatory framework contributed to endemic absenteeism, dismissals and disputes because mutual obligations were not set out and records of hours and wages not maintained. Employment law was needed to ‘modernize’ a relationship in which contracts were verbally agreed, if at all. Employers’ representatives agreed that the existing situation incurred significant costs to all parties due to a ready recourse to law and difficulty in adjudicating disputes:

Tonga is a highly litigious society, which reflects its culture and hierarchy... There is a cultural preference for a judge to hand down a decision. We try to resolve things on the part of our mainly employer clients but employees persist to the courts. The family rallies round to raise the finance to pursue a case even if it is not a strong one. The courts are usually slow, and the employee usually loses.

TCCI Official

However, the TCCI strongly opposed the Bill, arguing that it would “cripple businesses” by increasing costs when the economy had slumped since the global financial crisis and employers were adjusting to the introduction of compulsory superannuation in 2012. Employers at the very most favoured a minimal and gradual introduction of employment rights and it was reported by one CEO that these arguments were vociferously presented directly to government:

Don’t forget the powerful objectors don’t have a public face. We spend a lot of time (on) our Corporate Social Responsibility and we like to promote our business as contemporary and well-organized. But we have no illusions the darker side of business in Tonga have their hands on the wheel and they have no appetite for change.

Employment Bills were placed before the Tongan parliament four times between 1982 and 2005 but each failed due to opposition from politically well-represented business interests (Fisi’iahi, 2008). After the general election of 2014, in which the ruling party lost three of its twelve seats, the ERB disappeared from public view.

Officials in the MCTL continued to advocate for the Bill, linked to a momentum for ILO membership across the pacific island countries and which culminated in Tonga’s accession in 2016. Also highly relevant to their concern was internal political considerations relating to the resourcing and credibility of the MCTL and especially the Labour Division itself. The public service was restructured in 2012 under a World Bank program and respondents pointed out that the MLCI became the MCTL, with Labour placed from first to last with discussion of removing it from the new title completely. This symbolic change was accompanied by a diminution of resourcing, with the Labour Division reduced to four employees (with one on long-term study leave at the time of the study visit) of a total of 65 staff. Important functions such as visa processing and the employment service were transferred to other ministries. The Bill was thus seen as a way to demonstrate strategic relevance and secure resources.

The advocates of the ERB found support from trade unions, who viewed it as a vital safety net for vulnerable workers that would also present strong possibilities for union cooperation and growth. According to the general secretary of the PSA, “the Bill has been positive already in bringing the unions together and promoting unions to workplaces”. The six associations collaborated in advance of the proposed ERAC to form a joint committee and planned to register a joint body as the National Employees’ Association. The PSA also aimed to utilize any new representation rights to expand into the SOEs, and the seafarers union equally believed that a new law would facilitate its growth across the transport sector generally. The unions argued that this potential for labour organization explained a large part of employer opposition. However, a very limited union presence in the private sector meant there was little countervailing voice to the mobilization of employers. The political influence of the public sector unions was also diluted because the Bill was highly unlikely to apply to the public sector. The MCTL favoured a unified legal framework in which the ERB covered both the public and private sectors but this was opposed by the Public Service Commission and Solicitor General’s Office, even though benefits in the public sector generally well exceeded the Bill’s provisions. It was argued that current arrangements were settled and working well and that maintaining separate arrangements would relieve the MCTL of an unnecessary administrative burden and avoid confusing departmental demarcations. There was also a view that “the Bill would politicize the administration of the civil service by giving the PSA a greater role” (Senior Legal Official).

A lack of resources for the Labour Division inhibited communications and collaboration with other important players which could have potentially mobilized wider support in other departments. Instead, there were institutional differences with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) over visa authority, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) over its management of the employment service and seasonal work programs, and the Ministry of Education over child labour. A common message from all parties was that cross-functional relationship building and policy coordination was limited, stymied by high workloads relative to resources, which reinforced ‘ministerial silos’. Hence, the small Labour Division, with few powerful allies and well-organized employer opposition, faced serious obstacles in having its employment regulation agenda adopted.

PNG

The cases of Nauru and Tonga evidence the political complexities in originating labour law to do with power resources and constraints on ministerial initiatives and coordination. This was also demonstrated in PNG where relatively well-developed frameworks and activities were subverted by inadequate mechanisms for implementation and review. Policy development was hindered by an overly complex bureaucracy with overlapping and competing responsibilities. Two important examples are the protracted if not stalled efforts to introduce an over-arching Employment Policy (a condition of ILO membership) and the modernization of labour legislation through a new Industrial Relations Act. According to the Department of Labour and Industrial Relations (DLIR), inter-ministerial differences were a major problem:

The Employment Policy is complicated because it is a National Development Policy so the Department of National Planning has the mandate and authority to develop it... but our letters are ignored and we receive no written acknowledgement even when we hand deliver them!

DLIR Senior Official 1

The IR Bill went to the Central Agency Consultative Committee but it has been stuck there. This is because the proposals take some functions from other bodies.

DLIR Senior Official 2

Important institutions often also failed to convene. One example was the National Tripartite Consultative Committee (NTCC), which comprised 22 representative bodies from the private sector and state departments. Meetings were often inquorate and became increasingly irregular as a result:

The NTCC is overdue for meetings, but last year we only held one meeting, and you have the Labour [Ministry] people turn up and none of the others so you don’t have quorum. So the private sector sits on these boards to make an active contribution but in the absence of quorum from the government side, they don’t get to meet.

Private Sector CEO 1

Employers also complained that much of government policy resembled ‘tick-box’ exercises intended to impress international bodies but without due attention to implementation, monitoring and evaluation:

In terms of a policy, they have wonderful pieces of paper that say “we’re going to increase, under the MDTP [Medium-Term Development Plan], manufacturing and value-added industries to 30% of GDP by 2020” … with no plans, no policies, no direction, no employment strategies and the like ... instead of all this airy fairy sort of motherhood statements and things like that, what you need is tangible plans.

Private Sector CEO 1

This country is fantastic at planning, fantastic at planning, we’ll spend millions on planning and the donors will come and we’ll do plans and we’ll have all these policies and strategies we’re absolutely useless at implementing. So these policies, as far as I’m concerned, from my industry perspective, are pointless because they will not be translated into any kind of implemented management.

Private Sector CEO 2

Employers also noted that the implementation of labour legislation was insufficient in practice because inspection and enforcement was focused on a relatively small number of larger firms in order to reduce DLIR costs:

Those businesses that stick to the rule of law, stick to international conventions are handicapped essentially because of the lack of regulatory processes. They are on paper again, but not implemented. The policies and regulations and the law, the legislation is there but not implemented.

Private Sector CEO 2

The DLIR explained that it operated with increasingly strained resources due to its shift from a response to an inspection regime together with a substantial widening of its responsibilities to cover child labour, the informal economy[1] and operation of the overseas seasonal work program. These difficulties were compounded by fluctuating political support:

A perennial problem is changing leadership, which means things have to start all over again. The DLIR, like other ministries, has continually changing ministers, which delays progress and implementation. It is vital the department has managerial and funding stability, and is not simply politically dependent.

DLIR Senior Official 2

There are 22 Provinces [but only] 100 officers in the field. So there are issues around staffing and resources which can be a problem. Also, at lower levels, increased responsibilities mean there are added demands for resource - training and manpower. We have a logistical issue and general problems of resources in accessing remote areas. A key issue too is that employers are not sufficiently punished; there are very limited penalties.

DLIR Senior Official 3

The examples of child labour regulation and international seasonal work, which were recently added to DLIR responsibilities, also illustrate the complexities of inter-departmental relations. Children provide nearly a fifth of the labour force in PNG (ILO, 2011) and a number of regulatory initiatives followed ratification of the relevant ILO Child Labour Conventions (138 and 182) in 2000, notably the Lukautim Pikinini Act 2009. The Department of Community Development (DCD) has oversight of measures under the Act since the legislation concerns child welfare, but the DLIR has competency in the employment field. The research identified a number of gaps in policy and practice resulting from this institutional duality and funding, including inconsistent understandings and definitions of child labour across Departments; limited publicity and advocacy initiatives; and inadequate enforcement and evaluation. A lack of coordination and resourcing led to severe problems in implementing what was, on paper, good policy: “A key problem with policy is implementation—implementing existing provisions is more important than developing new policies. Related to this is awareness, for example most people don’t even know about the Pikinini Act.” (NGO).

The regulation of seasonal work schemes is also a new and increasingly important responsibility for the DLIR, with over 2,000 people registering their availability to work in Australia or New Zealand between 2011 and 2013. Again, departmental lobbying and sensitivities resulted in a compromise of multi-ministerial governance, as the National Executive Council (NEC) decided to divide responsibilities between the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), the DLIR and DCD. Oversight of the scheme was originally granted to DFAT because the program involved circular migration. In the event, most of the relevant staffing and expertise was provided by DLIR, but DFAT was reluctant to transfer the necessary funding. Many of the NEC decisions were therefore not implemented, including establishing a Trust Account to transfer resources from DFAT to DLIR or creating an Inter-Agency Working Group to assist returning workers. As with the NTCC referred to above, the seasonal work taskforce also comprised too many representatives (28) and was rarely quorate. The result was a lack of institutional buy-in and coordination: “We need to coordinate with other ministries but this didn’t work as each have their own priorities. Bureaucracy and politics come into play and it’s a nightmare trying to coordinate with other ministries.” (DLIR Senior Official 1)

Resourcing was again a major issue. The DLIR had to assume strategic as well as operational responsibilities, but its seasonal work unit comprised just three permanent officers and five contract staff. These constraints (linked to difficulties in accessing the Trust fund) led to operational problems across the management of the program, including data management, staff training, stakeholder liaison, monitoring working conditions overseas, and implementing post-return services.

The seasonal work program is thus another example of the difficulties of labour regulation in a complex bureaucratic environment with competing territories and constrained Labour Ministry funding. Such institutional problems are compounded by a lack of research support for policy development and evaluation. The collection of labour market data in PNG is weak, with no harmonized labour market indicators or regular business or labour force surveys, so that it is not clear how far policy commitments are implemented or evaluated in terms of impact. As one NGO Official put it, in PNG “the biggest issues are a lack of policy coordination, and limited research.”

Discussion

A comparison of the three countries suggests that pressures for employment regulation were different in each case, though there were shared political and resource difficulties in terms of policy development and implementation that were also linked to country size. Simply put, the smaller the country, the more acute were resource and capacity constraints; the more disorganized its employment relations; and the more concentrated and combined its networks of political and economic power, which served to limit the development of employment regulation. The drivers and constraints of employment regulation across the three cases are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Political pressures and barriers in labour regulation

In Nauru, a regulatory gap was increasingly evident with the growth of paid employment and the first expression of protest in the RPC. Donors were also looking for greater professionalism of management and employment practices, especially in the public sector. In Tonga, pressures for legislation arose in the context of democratization and the imbalance between the rights and protections afforded to public service employees and those elsewhere. Trade unions supported an Employment Relations Bill championed by Ministry officials who were looking ahead to prospective ILO membership and were also concerned to protect and promote their own institutional interests. In PNG, there was a body of employment law in place which in many ways appeared increasingly moribund but was at least subject to periodic review. The rapid development of the country also fed into a strategy cycle which linked employment, education and other social indicators to international development goals and standards.

In terms of constraints, in Nauru there was no organized voice demanding change either within or without government circles. Employment law was not a priority for politicians or their under-resourced ministries. In Tonga, organized pressure for change faced resistance from employers who seemed to exert unobtrusive influence on policy. In PNG, efforts by the Labour Ministry to modernize and integrate the labour law framework, establish an overall Employment Policy and improve the regulation of specific areas such as child labour and seasonal work (all supported by the ILO) were constrained by limited resources, a narrow evidence base and ongoing political change. This compounded the problems of institutional complexity introduced by the over-representation of otherwise siloed departments in policy development, and overlapping responsibilities in implementation and review.

One implication, as suggested at the outset, is that size matters in terms of employment regulation. In smaller countries, the formal private sector tends to be relatively less significant and less well organized, though in the case of Nauru it was dominated by the RPC to which political authorities were keen to defer. Whether private sector employment is relatively marginal or monopolized, this can reduce the priority attached to regulation by the state and, in the absence of effective trade unions and other civil society actors, means that employers can readily mobilize to oppose or defuse any proposals. Size is also relevant politically. Smaller countries have closer and more personalized networks of political and economic governance. They are also less likely to have dedicated or adequately resourced labour ministries. In PNG, for example, which has a formal private economy dominated by multi-national companies and better resourcing for policy development, there is greater capacity for, and less hostility to, labour law proposals. However, the problem in this case is policy conclusion and implementation. This is a function of bureaucratic complexity, institutional rivalries and insufficient monitoring and enforcement. In each country, problems of policy development and implementation are also linked to a profound lack of labour market data with which to inform and support the regulatory process.

Overall, then, a comparison of the three case results shows that each have experienced internal and/or external pressures for employment regulation and reform but there are political and resource difficulties impeding this. These problems (e.g. concentration of power, lack of Labour Ministry resources, limited trade union voice) are more intense in the two smaller countries but are also present in the larger case where there are additional problems around bureaucracy. The research also suggests that the progress of employment regulation within smaller LDCs is subject to a configuration of structure and agency, internal and external factors, as tentatively offered as a guide for future research in Table 3. Structure refers to the size of the economy, particularly the formal private sector, the stage and diversification of economic development, and the stability of political institutions. Agency factors include the role, resourcing and status of labour ministries and other relevant non-state actors (NSAs) such as unions, employer organizations and NGOs. International factors are also relevant. These include the level of dependence on overseas aid, obligations under international treaties, priorities of influential aid partners such as AusAid and the EU, and the degree of technical and other support provided by international agencies (IAs) such as the ILO and World Bank.

Table 3

Dynamics of employment regulation

Conclusions

In the opening sentence of their analysis of labour regulation, Botero et al. (2004: 1339) assert that, “Every country in the world has established a complex system of laws and institutions intended to protect the interests of workers and to guarantee a minimum standard of living to its population.” Unfortunately, this is not the case. The development, implementation and enforcement of labour law and other forms of regulation is difficult and patchy, if not entirely absent, in many small developing countries. This paper has explored why this might be the case, highlighting political factors to do with the fluidity and opacity of governance, the under-resourcing of labour authorities and the relative power and influence wielded by employers compared to labour representatives and other civil society actors. It is suggested that the extent and effectiveness of employment regulation is linked to country size, with smaller states less willing and/or able to legislatively intervene in labour markets. Interestingly, in these three cases at least, the size of the informal economy, which is commonly seen as a retarding factor in employment regulation in LDCs (Boeri et al., 2008), was not of itself a decisive factor. Nauru, in which almost all working age adults are in paid employment, has no employment law, whereas PNG, where the labour force is overwhelmingly engaged in subsistence and informal work, has the most systematic arrangements. This underscores the importance of political and historical and not just economic dynamics in understanding how employment regulation might connect to stages of development.

The research was based on a comprehensive set of interviews in each of the three countries but has a number of significant limitations. This includes the country sample, which was small and could be said to be idiosyncratic. The focus was on institutional considerations and did not directly investigate cultural factors. In addition, the data were provided mainly by ministry officials and representatives of employer associations, trade unions and NGOs and no politicians (who ultimately decide on employment regulation) were interviewed. It almost goes without saying that further academic work is required given how little is known about the dynamics of labour regulation in smaller LDCs.

Recognizing the limitations of this study, future research, which we argue strongly benefits from comparative qualitative methods, would best be served by a political economy or systems approach, sensitive to historical, political and cultural contexts, not least because the two main established western traditions in the analysis of employment regulation are insufficient for understanding developments in LDCs. Industrial Relations scholarship approaches regulation as a system of institutions and rules designed to mediate employment by recalibrating power relationships (Colling and Terry, 2010). However, this perspective assumes that the state is both well-resourced and ‘autonomous’, that is, relatively independent of dominant interests (Martinez Lucio and Stuart, 2011). Neither readily applies in LDCs where labour ministries usually face severe capacity constraints and governments are more prone to influence by powerful élites (UN, 2009). The second tradition is Labour Economics, which tends to focus on the impact of wage and employment protection on productivity and employment. The dominant theoretical paradigm utilizes models resting on abstract assumptions and the application of econometric techniques that fail to acknowledge the often messy realities of labour markets in LDCs (Boeri et al., 2008). This literature retains a narrow focus on the hypothesized effects of labour law (at least in large LDCs) and understanding of the institutional processes of regulation remains limited, especially in smaller countries.

In these contexts, research needs to adopt a ‘systemic view’ of labour markets and labour law which differs from the neoclassical and institutionalist paradigms by being especially sensitive to “particular economic and political contexts” (Deakin, 2011: 162). Research such as our own provides partial insights, but a holistic research strategy would need to be grounded in more complete understandings of local culture, political systems and mechanisms of social reproduction as well as labour market governance (Peck, 1996; Poole, 1986). This suggests a political economy or, as Teklè (2010: 11) refers to it, a “law in context” approach to analyzing labour regulatory regimes, inclusive of labour market, cultural and socio-political structures.

The implications for policy and practice of this research are more concrete. Miles (2015) argues that the limited formation and (unbalanced) articulation of interests and interactions between state and non-state actors serves as a brake on employment regulation but also offers a productive space for the ILO to mediate an ‘integrative approach’ (Kolben, 2011). These findings emphasize the importance of capacity building in local regulatory agencies, together with stakeholder outreach and engagement activities, in order to ensure better policy coordination, regulatory awareness and compliance. The technical as well as financial assistance provided by international bodies such as the ILO and aid partners is likely to remain crucial in this regard, in the Pacific Islands and smaller LDCs generally.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the International Labour Organization (ILO) under a series of competitive grant awards. The authors very much appreciate the support of ILO officials but note that the views expressed here, and any errors and omissions, are those of the authors alone. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the many individuals who took part in the fieldwork.

Note

-

[1]

The Informal Sector Development and Control Act 2004 was introduced to promote the development of informal businesses by providing access to finance and public goods and services whilst bringing them under public health and safety regulations. The National Policy elaborates an active role for the DLIR in “advocating, training and building awareness on human rights issues in the world of work, including in the informal economy” (DCD, 2011: 34).

References

- Arrowsmith, James and Jane Parker (2015) Situational Analysis of Employment in Nauru. Suva: ILO. Retrieved from https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/Situational%20Analysis%20of%20Employment%20in%20Nauru.pdf, (December 21st 2019).

- Arthurs, Harry (2011) “Labour Law After Labour.” In Guy Davidov and Brian Langille (eds.), The Idea of Labour Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 13-29.

- Arthurs, Harry (2015) Labour Law and Transnational Law: The Fate of Legal Fields/The Trajectory of Legal Scholarship. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3228120, (December 21st 2019).

- Asian Development Bank (2007) ADB Country Economic Report: Nauru. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/33611/files/cer-nau-2007.pdf, (December 21st 2019).

- Asian Development Bank (2013) ADB Nauru Factsheet. Retrieved from https://think-asia.org/bitstream/handle/11540/363/NAU.pdf?sequence=1, (December 21st 2019).

- Ayres, Ian and John Braithwaite (1992) Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baccaro, Lucio and Valentina Mele (2012) “Pathology or Path Dependency? The ILO and the Challenge of New Governance.” ILR Review, 65 (2), 195-224.

- Bacchetta, Marc, Ekkehard Ernst and Juana Bustamante (2009) Globalization and Informal Jobs in Developing Countries. Geneva: ILO/WTO.

- Bamber, Greg, Russell Lansbury and Nick Wailes (2004) “Introduction.” In Greg Bamber, Russell Lansbury and Nick Wailes (eds.), International and Comparative Employment Relations. London: SAGE, p. 1-35.

- Barry, Michael and Adrian Wilkinson (2011) “Re-examining Comparative Employment Relations.” In Michael Barry and Adrian Wilkinson (eds.), Research Handbook of Comparative Employment Relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, p. 3-24.

- Bean, Ron (1985) Comparative Industrial Relations. London: Croom Helm.

- Betcherman, Gordon (2014) “Designing Labor Market Regulations in Developing Countries.” IZA World of Labor, 57, 1-10.

- Betcherman, Gordon (2015) “Labor Market Regulations: What Do We Know about their Impacts in Developing Countries?” World Bank Research Observer, 30 (1), 124-153.

- Boeri, Tito, Brooke Helppie and Mario Macis (2008) “Labor Regulations in Developing Countries: A Review of the Evidence and Directions for Future Research.” SP Discussion Paper No. 0833. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- Botero, Juan, Simeon Djankov, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer (2004) “The Regulation of Labor.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, November, 1, 339 (1), 382.

- Braithwaite, John (2006) “Responsive Regulation and Developing Countries.” World Development, 34 (5), 884-898.

- Budd, John (2004) Employment with a Human Face: Balancing Efficiency, Equity, and Voice. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

- Colling, Trevor and Michael Terry (2010) “Work, the Employment Relationship and the Field of Industrial Relations.” In Trevor Colling and Michael Terry (eds.), Industrial Relations: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Wiley, p. 3-25.

- Cooke, Fang Lee, Alex Veen and Geoffrey Wood (2017) “What Do We Know About Cross-Country Comparative Studies in HR? A Critical Review of the Literature in the Period of 2000-2014.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28 (1), 196-233.

- Cooney, Sean, Peter Gahan and Richard Mitchell (2011) “Legal Origins, Labour Law and the Regulation of Employment Relations.” In Michael Barry and Adrian Wilkinson (eds.), Research Handbook of Comparative Employment Relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, p. 3-24.

- Crosby, Benjamin (1992) Stakeholder Analysis: A Vital Tool for Strategic Managers. Washington: USAID.

- Davies, Anne and Ben Doherty (2018) “Corruption, Incompetence and a Musical: Nauru’s Cursed History.” The Guardian, 3 Sept.

- Deakin, Simon (2011) “The Contribution of Labour Law to Economic and Human Development.” In Guy Davidov and Brian Langille (eds.), The Idea of Labour Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 156-176.

- Deakin, Simon and Prabirjit Sarkar (2008) “Assessing the Long-Run Economic Impact of Labour Law Systems: A Theoretical Reappraisal and Analysis of New Time Series Data“. Industrial Relations Journal, 39 (6), 453-487.

- Deakin, Simon and Frank Wilkinson (2005) The Law of the Labour Market: Industrialization, Employment and Legal Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Department for Community Development-DCD (2011) National Informal Economy Policy (2011-2015). Port Moresby: DCD/Institute of National Affairs.

- Djankov, Simeon and Rita Ramalho (2009) “Employment Laws in Developing Countries.” Journal of Comparative Economics, 37 (1), 3-13.

- Elger, Tony (2009) “Industrial Relations and the ‘Sociological Imagination’.” In Ralph Darlington (ed.), What’s the Point of Industrial Relations? In Defence of Critical Social Science. Manchester: BUIRA, p. 96-104.

- Fisi’iahi, Fotukaehiko (2008) “The Impact of Prolonged Absence of Labour Legislation in Promoting Decent Work in Tonga.” Unpublished Paper atthe 22nd Conference of AIRAANZ, Melbourne, February 6-8.

- Fudge, Judy (2011) “Labour as a ‘Fictive Commodity’: Radically Reconceptualizing Labour Law.” In Guy Davidov and Brian Langille (eds.), The Idea of Labour Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 120-135.

- Fudge, Judy (2018) ‘‘Regulating for Decent Work in a Global Economy.’’ New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 43 (2), 10-23.

- Graham David and Ngaire Woods (2006) “Making Corporate Self-Regulation Effective in Developing Countries.” World Development, 34 (5), 868-883.

- Hanlon, Robert (2014) Corporate Social Responsibility and Human Rights in Asia. London: Routledge.

- Hantrais, Linda and Steen Mangen (2007) Cross-National Research: Methodology and Practice. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Hepple, Bob (2011) “Factors Influencing the Making and Transformation of Labour Law in Europe.” In Guy Davidov and Brian Langille (eds.), The Idea of Labour Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 30-42.

- Hyman, Richard (1989) The Political Economy of Industrial Relations: Theory and Practice in a Cold Climate. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hyman, Richard (2004) “Is Industrial Relations Theory Always Ethnocentric?” In Bruce Kaufman (ed.), Theoretical Perspectives on Work and the Employment Relationship. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, p. 265-292.

- Hyman, Richard (2009). “Why Industrial Relations?” In R. Darlington (ed.), What’s the Point of Industrial Relations? In Defence of Critical Social Science. Manchester: BUIRA, p. 31-43.

- Imbun, Benedict (2006) Review of Labour Laws in PNG. Working Paper, School of Economics, Employment and Labour Market Studies, University of the South Pacific, no. 2006/20 (ELMS-7), July.

- Imbun, Benedict (2006) “Multinationales minières et les travailleurs indigènes en Papouasi-Nouvelle-Guinée: Tensions et défis dans les relations industrielles.” Travail, Capital et Societé, 39 (1), 112-148.

- International Labour Organization (1997) The ILO, Standard Setting and Globalisation. Report of the Director General, International Labour Conference, 85th Session, Geneva.

- International Labour Organization (2011) Individual Observation Concerning Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182) Papua New Guinea (ratification: 2000), Committee of Experts, September.

- International Labour Organization (2014a) Decent Work and Social Justice in Small Island Developing States. Suva: ILO Office for Pacific Island Countries.

- International Labour Organization (2014b) Decent Work. Retrieved from: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang--en/index.htm (December 21st 2019).

- Kaufman, Bruce (2011) “Comparative Employment Relations: Institutional and Neo-Institutional Theories.” In Michael Barry and Adrian Wilkinson (eds.), Research Handbook of Comparative Employment Relations, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, p. 25-55.

- Kaufman, Bruce (2012) “Economic Analysis of Labor Markets and Labor Law: An Institutional/Industrial Relations Perspective.” In Cynthia Estlund and Michael Wachter (eds.), Research Handbook on the Economics of Labor and Employment Law. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, p. 84-121.

- Kolben, Kevin (2011) “Transnational Labour Regulation and the Limits of Governance.” Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 12 (2), 403-437.

- Livingstone, Sonia (2003) “On the Challenges of Cross-National Comparative Media Research.” European Journal of Communication, 18 (4), 477-500.

- Marginson, Paul (2016) “Governing Work and Employment Relations in an Internationalized Economy: The Institutional Challenge.” ILR Review, 69 (5), 1,033-1,055.

- Martinez Lucio, Miguel and Mark Stuart (2011) “The State, Public Policy and the Renewal of HRM.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22 (18), 3,661-3,671.

- Merriam, Sharan (2009) Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, Lilian (2015) “The ‘Integrative Approach’ and Labour Regulation and Indonesia: Prospects and Challenges.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, 36 (1), 5-22.

- Mills, Melinda, Gerhard van de Bunt and Jeanne de Bruijn (2006) “Comparative Research: Persistent Problems and Promising Solutions.” International Sociology, 21 (5), 619-631.

- Ministry of Commerce, Tourism and Labour (2014) Business Survey Report, July, Nuku’Alofa: MCTL.

- Ministry of Education and Training (2013) The Tonga and Regional Labour Market Review 2012. Nuku’Alofa: MET TVET Support Program.

- Ministry of Finance (2013) Republic of Nauru 2013-14 Budget, Budget Paper 2. RON: MoF.

- Ministry of Information and Communications (2013) “Government to Introduce Employment Relations Bill 2013.” Retrieved from: http://www.mic.gov.to/government/latest-decisions-and-bills/4382-government-determined-to-introduce-the-employment-relations-bill-2013, (December 21st 2019).

- Ministry of Labour, Commerce and Industries (2009) National Investment Policy Statement. Nuku’Alofa: MLCI.

- Mjøset, Lars (2006) “A Case Study of a Case Study: Strategies of Generalization and Specification in the Study of Israel as a Single Case.” International Sociology, 21 (5), 735-766.

- Nauru Bureau of Statistics (2009) Nauru Bureau of Statistics Strategic Direction and Forward Work Plan 2010-2015. RON: NBS.

- OECD (2011) Aid Effectiveness 2005-10: Progress in Implementing the Paris Declaration: Appendix A - Country Data – OECD. Paris: OECD.

- Olivier, Marius (2013) “International Labour and Social Security Standards: A Developing Country Critique.” International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 29 (1), 21-38.

- Peck, Jamie (1996) Work Place: The Social Regulation of Labor Markets. New York, London: Guildford Press.

- Poole. Michael (1986) Industrial Relations: Origins and Patterns of National Diversity. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Przeworski, Adam and Henry Teune (1970) The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: Wiley.

- Ragin, Charles (1994) Constructing Social Research: The Unity and Diversity of Method. Northwestern University, Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

- Reilly, Benjamin (2004) “State Functioning and State Failure in the South Pacific.” Australian Journal of International Affairs, 58 (4), 479-493.

- Rogowski, Ralf (2013) Reflexive Labour Law in the World Society. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Rudra, Nita (2008) Globalization and the Race to the Bottom in Developing Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sankaran, Kamala (2011) “Informal Employment and the Challenges for Labour Law.” In Michael Barry and Adrian Wilkinson (eds.), Research Handbook of Comparative Employment Relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, p. 223-233.

- Sen, Amartya (1999) Development as Freedom. N.Y.: Oxford University Press.

- Simmons, John and Ian Lovegrove (2005) “Bridging the Conceptual Divide: Lessons from Stakeholder Analysis.” Journal of Organizational Change Management, 18 (5), 495-513.

- Stake, Robert (2009) The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Streeck, Wolfgang (1997) “Beneficial Constraints: On the Economic Limits of Rational Voluntarism.” In Joseph Hollingsworth and Robert Boyer (eds.), Contemporary Capitalism: The Embeddedness of Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 197-218.

- Taufatofua, Pita (2011) Migration, Remittance and Development in Tonga. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-an477e.pdf, (December 21st, 2019).

- Teklè, Tzehainesh (2010) “Labour Law and Worker Protection in the South: An Evolving Tension between Models and Reality.” In Tzehainesh Teklè (ed.), Labour Law and Worker Protection in Developing Countries. Geneva: ILO, p. 3-47.

- Teubner, Gunther (1983) “Substantive and Reflexive Elements in Modern Law.” Law and Society Review, 17 (1), 239-285.

- United Nations (2009) The Least Developed Countries Report 2009: The State and Development Governance. UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Geneva: UN.

- Walsh, Michael (2016) “Powerful Nauru Families Benefiting from Australian-Funded Refugee Processing Centre.”, ABC News. Retrieved from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-03-29/nauru-families-directly-benefiting-from-australian-funded-centre/7278120, (December 21st, 2019).

- Weiss, Manfred (2011) “Re-Inventing Labour Law?” In Guy Davidov and Brian Langille (eds.), The Idea of Labour Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 43-68.