Abstracts

Abstract

During the Romantic period, it became possible to transform authorship into celebrity through a process of what might be termed ‘spectacularisation’. Verbal and visual representations of certain writers as private individuals, which often appeared in the periodical press, helped to mark them out within a massively competitive literary marketplace and provided their readers with a sense of intimate connection. This article considers this process in relationship to the women writers depicted in William Maginn’s “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters” (Fraser’s Magazine, 1830-36). In particular, I argue that the 1836 article ‘Regina’s Maids of Honour’ is crucial for understanding not only how the “Gallery’s” mixed rhetoric of chivalry and prurience operates both to restrict and expose its female subjects, but also Maginn’s intense self-consciousness about this process. Throughout, he conflates references to his subjects’ works with descriptions of their looks, thereby ensuring that their public lives as writers cannot be separated from the inspection of their bodies by a masculine observer. Although “Regina’s Maids of Honour” places women writers in a genteel domestic setting, Maginn offers male readers a frisson of scandalous excitement with sexualized portrayals of those – Caroline Norton, Letitia Landon, and Marguerite Blessington – whose lifestyles challenged the strict boundaries of domestic propriety.

Article body

Romantic periodicals used theoretical accounts of genius – and descriptions of individual geniuses – in order to articulate their own ideological positions and to try to assert their critical and commercial superiority to their competitors. However, these representations were riven by tension and contradiction: genius, after all, was imagined to be superior to the supposedly debased literary culture in which periodicals were produced and read, and to despise contemporary celebrity in favour of posthumous fame. This article will consider the relationship between genius, celebrity, and gender in the late Romantic period by examining William Maginn’s “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters”, an extensive and powerful set of literary portraits that helped to establish Fraser’s Magazine as the major literary journal of the 1830s. Although in a number of articles from this period, Fraser’s celebrated literary genius as a divine force, using the sort of idealising rhetoric we might call “High Romantic,” the “Gallery” took a different approach to authorship: gossipy, iconoclastic, and more concerned with social appearance than artistic essence.[2] In that respect, it typified a burgeoning culture of literary celebrity in which the boundaries between the “public” and “private” personae of authors were ambiguous and porous. Maginn, I will argue, was highly self-conscious about the tensions inherent in turning genius into a spectacle for Fraser’s’ readers.[3] This was particularly apparent when the “Gallery” depicted women writers.[4] As Valerie Sanders has suggested, the 1830s “literary marketplace [was] dominated essentially by a clubhouse of male satirists who were far from lenient on their own sex, and radically unsure how to treat the other” (43). Given that women were supposedly predominantly private beings, it was unclear how those that entered the public sphere as authors were to be represented in reviews and articles that often moved fluidly between the textual and the personal. Furthermore, the extent and nature of female genius was a problematic issue, with male critics often applying the term grudgingly or with irony, if at all.[5]

Maginn had gained his reputation in the 1820s as a brilliant but scurrilous journalist through his contributions to a number of periodicals, most notably and most successfully Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. Founded in 1830, with Maginn as editor, Fraser’s was the best and most vibrant literary magazine of the 1830s, with similar sales to the two most powerful Reviews, the Edinburgh and the Quarterly.[6] It carried the baton of Blackwood’s (by now relatively respectable) into a new decade, offering an energetic and inventive mixture of literary criticism, miscellaneous articles, satire, and personal attacks, all of which generally adhered to a strongly Tory ethos. Maginn’s character – a mixture of childish vindictiveness, deep erudition, emotional volatility and brilliant creativity – pervades its pages. In its early years, Fraser’s positioned itself against its competitors by accusing them (with some justification) of being dominated by commercial interests, especially in their reviewing. Its other major literary target was the fashionable novel and in particular the work of Edward Lytton Bulwer (later Bulwer-Lytton), writer of “silver fork” and “Newgate” fiction, editor of the New Monthly Magazine during the early 1830s, dandified man about town, and Radical politician.[7]

The Fraser’s attacks on the shallowness of contemporary literature existed alongside a strong interest in the subject of literary genius. This was a topic of particular concern in the late Romantic period because Britain seemed to be so lacking in great writers. For most contemporary critics, the collapse of the market for poetry proved that they were living in a literary “Age of Bronze”, and the chorus of lamentation grew louder during the early 1830s, when, it was often claimed, the Reform Bill agitation resulted in “Literature” being ignored by the public.[8] It was also argued by some writers that the increasingly powerful discourse of Benthamite utilitarianism threatened literature and the fine arts by representing them as no more than amusing luxuries (De Groot; Hemingway). At the same time, the continuing expansion of the periodical press saw the emergence of a new class of professional journalists; this problematised earlier models of authorship because they were perceived neither as “men of genius” nor as booksellers’ hacks (Cross 90-91). Patrick Leary has written that in its early years, Fraser’s “stands astride a fault line of conceptions of what constitutes the literary life”, between “the Romantic ideal of the literary man as heroic genius” and “the mid-Victorian author-businessman as a respectable literary professional” (106). Both “conceptions” appear in the journal at various times, as does a third: the author as hard-living Bohemian.

John Abraham Heraud (Maginn’s editorial assistant) wrote several Fraser’s articles that pushed to an extreme the connection between the creative artist and moral virtue to be found in foundational Romantic texts such as Shelley’s “Defence of Poetry” and Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria, by developing a strong link between genius and Christian spirituality in its highest form. But alongside this sort of rhetoric was the different approach to literary figures manifested in Maginn’s gallery. Part of Fraser’s success, as Leary argues, “lay in breaking through the traditional anonymity of the periodical press by ushering the reader into vicarious informal fellowship with some of the leading writers of the day” (112). Much more than was the case with other such series of literary portraits, Maginn’s subjects were interwoven into the fabric of the magazine’s identity. The anonymous articles, always a page in length, were based on Daniel Maclise’s accompanying drawings (published under the pseudonym “Albert Croquis”), which often depicted the subject in a state of private, domestic relaxation. They relied for their effect on giving the reader a sense of personal intimacy with the authors described. This publicisation of the private sphere tended to construct the “Gallery’s” subjects as celebrity figures who were interesting as much for what they were as for what they wrote. Maginn’s tone was generally irreverent, even when praising writers of whom Fraser’s approved, and enemies of the magazine (Whigs and Radicals) got a rough ride. The main point of the series was to place the recently-launched Fraser’s securely in the literary firmament by positioning it in relation to a number of friends and enemies. The sheer number of portraits, and their incisiveness, meant that this was achieved with greater success than in the case of any other magazine.

The January 1835 issue contained Maclise’s sketch of “The Fraserians” (image 1), which depicted twenty-six of the gallery’s subjects seated at a convivial dinner over which Maginn presided, and which was described in his accompanying article. Leary has pointed out that “Fraser’s self-consciously projected itself as the product of a distinct literary coterie”, and that this projection was partly mythical, for some of the figures in “The Fraserians” had published very little in the magazine, and six of them – Southey, Murphy, D’Orsay, Hook, Jerdan, and Coleridge (who had died three months earlier) – had contributed nothing at all (111). Particularly in the case of Coleridge, Maginn was representing himself and Fraser’s as being on familiar terms with literary genius in order to increase the journal’s prestige (Lapp). Thus in his early three-part article “The Election of Editor for Fraser’s Magazine”, in which Maginn ventriloquises through a host of contemporary literary characters, Coleridge, “the first genius of the age”, is elected editor (497). This sort of playful myth-making was made possible by a culture of anonymity that cloaked the identities of journal editors, as well as contributors.

Image 1

[Daniel Maclise]. “The Fraserians.” Fraser’s Magazine 11 (January 1835). Reproduced from William Bates (1891). The Maclise Portrait-Gallery. London: Chatto & Windus. Please note that the Fraser’s version of this sketch did not include the names of the authors depicted.

In contrast to some other literary galleries of the period, the “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters” included a number of women writers. Given Fraser’s Magazine’s conservatism, it is not surprising that its portraits were prescriptive about the fit topics for female genius. Maginn states in his self-consciously chivalrous portrait of Caroline Norton that “we think that a lady ought to be treated, even by Reviewers, with the utmost deference – except she writes politics, which is an enormity equal to wearing breeches” (222). And Francis Mahony imagines himself to be defending Letitia Landon from a grumpy critic, whom he characterised as “Squaretoes,” that is, foolishly old-fashioned and formal:

There is too much about love in them, some cross-grained critic will say. How, Squaretoes, can there be too much of love in a young lady’s writings? we reply in a question. Is she to write of politics, or political economy, or pugilism, or punch? Certainly not. We feel a determined dislike of women who wander into these unfeminine paths; they should immediately hoist a mustache - and, to do them justice, they in general do exhibit no inconsiderable specimen of the hair-lip. We think Miss L. E. L. has chosen much the better part. She shews every now and then that she is possessed of information, feeling, and genius, to enable her to shine in other departments of poetry; but she does right in thinking that Sappho knew what she was about when she chose the tender passion as the theme for women.

433

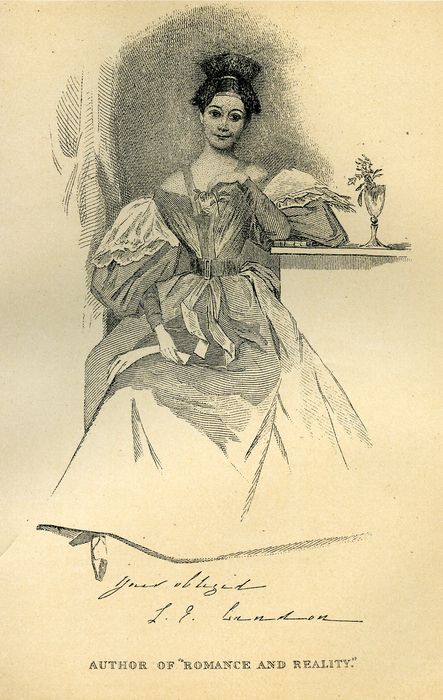

Emphasizing the limitations of female genius may have been particularly important to Fraser’s because its writers (with the odd exception) tended not to take the line that genius was intrinsically transgressive and anti-domestic, a topical argument in the early 1830s due to various biographies of Byron. If genius was compatible with virtue and domesticity, though, this opened up the worrying possibility that women could be geniuses in the same way as men. Mahony, therefore, relies on a fairly familiar argument that women should stick to love lyrics and not write on topics outside the private sphere, even if they are equipped to do so. The dreadful pun on “hair-lip” works to suggest several things: that women who stray into such areas will appear ridiculous and lose their femininity (Maginn makes the same point when he imagines women “wearing breeches”); that they will be in some way marked out, scarred, stigmatised, perhaps even deformed; and that they will be unable to express themselves properly. It is not even that Landon lacks genius, or is ignorant about things other than “the tender passion,” but that she rightly chooses to limit her writing to that one subject: she knows her place and does not challenge masculine ideas of the “poetess” as a woman preoccupied by erotic emotion.[9] Maclise’s portrait (image 2) also exemplifies this: Landon’s “large eyes, small mouth, hands, feet, and wasp waist liken her to an Annual beauty [and] the limp hand holding a flower suggests her sentimentality” (Fisher 120). By describing the boundary between public and private in aesthetic terms, the “Gallery” conflates female beauty and female genius: the woman writer’s face and body become a barometer of her respect for this boundary, and therefore of her literary merit.

Image 2

[Daniel Maclise]. “Author of ‘Romance and Reality’.” Fraser’s Magazine 8 (October 1833). Reproduced from William Bates (1891). The Maclise Portrait-Gallery. London: Chatto & Windus.

One imagines Mahony writing this essay with Maginn looking over his shoulder: its rhetoric is similar to that of other “Gallery” portraits of women writers, and, indeed, to utterances from earlier in Maginn’s career. Writing in Blackwood’s in 1824, he exclaims:

What stuff in Mrs Hemans, Miss Porden, &c. &c. to be writing plays and epics! There is no such thing as female genius. The only good things that women have written, are Sappho’s Ode upon Phaon, and Madame de Stael’s Corinne; and of these two good things the inspiration is simply and entirely that one glorious feeling, in which, and in which alone, woman is the equal of man. They are undoubtedly mistress-pieces.

[Maginn and Lockhart] 603

Maginn goes further than Mahony in provocatively denying the existence of “female genius,” but similarly emphasises the proper genres and theme for women writers, suggesting that they are not equipped to tackle the higher genres of drama and epic – the provinces of masculine genius – and can only achieve anything of literary merit by confining themselves to sentimental lyrics and novels. The reference to Corinne is significant given that de Staël’s novel strongly influenced Landon’s long poem “The Improvisatrice,” first published in 1824. Daniel Riess has argued that while the poem keeps the “bare bones” of Corinne’s plot, the novel’s “subversive” politics and “feminism” are removed. What remains is a story that emphasises the suffering of the female genius courted and then rejected by her lover (814-817). Maginn clearly sees the novel in similar terms. Given that “The Improvisatrice” contains a section called “Sappho’s Song,” it is likely that he had Landon’s poem in mind when writing this passage,[10] as Mahony may have done when he mentions Sappho in the 1833 portrait of Landon. Recent critics have noted that Sappho tended to be linked to Corinne by nineteenth-century women poets, and that the latter was an important figure in that she seemed to articulate both a “private” identity as a suffering, lovelorn woman, and a “public” identity as a national heroine-genius (Leighton 3-4; Francis 107-112). Maginn, however, emphasises the former and downplays the latter: Sappho’s and Landon’s poetry, and de Staël’s novel, are (it seems) to be valued for their portrayal of sexually-available women, who are left abandoned, desolate, and suicidal.

The extent and nature of “female genius” was a topic of debate throughout the Romantic period, and few critics would have concurred with Maginn’s deliberately provocative claim that there is “no such thing.” A liberal like Bulwer, for example, reviewing Landon’s novel Romance and Reality in 1831, describes her as “a lady of remarkable genius” (546), and suggests that “the soul of a woman is as fine an emanation from the Great Fountain of Spirit as that of a man” (545). There is even an anonymous Fraser’s article from 1833 on “The Female Character,” which argues strongly “that in the arts and sciences, in the noblest efforts of mortal genius, and in the highest aspirings of human intellect, the female mind has and can rival that of the other sex” (595). This reminds us that Fraser’s was well able to contain a variety of conflicting opinions. However, the “Gallery” was consistent in its attitude to women writers: whatever genius they had was, or should be, limited to sentimental works about love: “mistress-pieces,” as Maginn puts it. This pun on “masterpiece” is also punning on two meanings of “mistress”: “a woman who is proficient in an art, craft, or other branch of study” and “a woman other than his wife with whom a man has a long-lasting sexual relationship” (OED). The most successful female writers, he is implying, are those whose works express and/or elicit (perhaps scandalous) sexual desire.

Maginn emphasises the limitations of female genius again in his Fraser’s portrait of Mary Russell Mitford, although, as so often with Maginn, the tone is ironic and the meaning slippery. Over her career, Mitford had written long poems and tragic dramas, but she was best known for her stories of everyday rural life, collected in various volumes of Our Village (1824-1832). “Ungallant” male critics, Maginn states, suggest that women “can never be distinguished generals, scientific cooks, first-rate tragedians, high-class epics, or piquant epigrammists, and in spite of Joan of Arc, Mrs Rundell, Joanna Baillie, Miss Mitford, and Louisa Sheridan, we are pretty much of that opinion” (“Mary Russell Mitford”). (Maria Elizabeth Rundell was the author of the highly successful book Domestic Cookery; Louisa Sheridan was the editor of the annual Comic Offering; or Ladies’ Melange of Literary Mirth.) Maginn is self-conscious about his own “ungallant” position here and this statement is tricky to pin down: the casual juxtaposition of “Joan of Arc” with the names of the four writers creates bathos, and the qualifier “pretty much” sits uneasily with the certainty of “never.” It is also not clear whether Maginn means ‘despite the achievements of these five women,’ or ‘despite the pretensions of these five women.’ Therefore the sentence offers at least the possibility of self-contradiction: women can never be geniuses in the same fields as men, and yet occasionally they might be. Maginn is well aware that closing off the possibilities of female genius is problematic, even while he seeks to do so.

The Fraser’s antipathy towards women writers who wandered into “unfeminine paths” is most strongly apparent in Maginn’s vitriolic and self-consciously iconoclastic portrait of Harriet Martineau (image 3), who made her reputation in the early 1830s through her Illustrations of Political Economy (1832-34), one of Mahony’s banned subjects for female writers. Martineau’s portrait appeared the month after Landon’s: one suspects that this was meant to emphasise the contrast between them. Maginn begins by snidely implying that she is unattractive to men, and that this explains her Malthusianism (that is, her support for controlling population growth). The Illustrations are didactic short stories, two of which, “Ella of Garveloch” and “Weal and Woe in Garveloch,” deal with “preventive check” in relation to population. The thought of “a young lady capable of writing on the effects of a fish diet on population” appalls Maginn:

Mother Wollstonecroft [sic], in some of her shameless books,- books which we seriously consider to be in their tendency […] more mischievous and degrading than the professedly obscene works which are smuggled into clandestine circulation, under the terms of outraged law,- boasts that she spoke of the anatomical secrets of nature among anatomists “as man speaks to man.” Disgusting this, no doubt; but far less disgusting when we find the more mystical topics of generation, its impulses and consequences – which the current consent of society, even the ordinary practice of language […], has veiled with the decent covering of silence, or left to be examined only with philosophical abstraction;-brought daily, weekly, monthly before the public eye, as the leading subjects, the very foundation-thoughts, of essays, articles, treatises, novels! tales! romances! to be disseminated into all hands, to lie on the breakfast-tables of the young and fair, and to afford them matter of meditation.

576

Words like “disgusting” and “degrading,” the hyperbolical suggestion that Wollstonecraft’s writings are more pernicious than pornography, and the breathless piling up of subordinate clauses, all suggest deep-seated anxiety about the challenge that someone like Martineau presents to a repressive, patriarchal literary culture and, indeed, to patriarchal society in general. Two related aspects of her writings particularly horrify Maginn. The first is that she challenges the conservative fetishisation of the boundaries between public and private by opening up the sexual practices of society to public display. The second is that she does so in the form of fiction. Essays and treatises are bad enough, but, as the apostrophes show, treating these “mystical topics” in genres likely to be read by pretty young women is even worse. Therefore Martineau’s literary career provokes “the regret of all who feel respect for the female sex and sorrow for perverted talent, or, at least, industry” (Maginn 476). She may have talent, but, unlike Landon (her antithesis), she certainly lacks genius. Maginn’s refusal to use the term is hardly surprising given his tendency to conflate female genius and female attractiveness; Martineau’s “ugliness” becomes a signifier of her artistic failure. No man would want her as his “mistress” and therefore she will never produce a “mistresspiece.”

Image 3

[Daniel Maclise]. “Author of ‘Illustrations of Political Economy’.” Fraser’s Magazine 8 (November 1833). Reproduced from William Bates (1891). The Maclise Portrait-Gallery. London: Chatto & Windus.

As Adele M. Ernstrom has shown in a stimulating discussion, Maclise’s portrait of Martineau (cat on her shoulder and tending a cooking pot) and Maginn’s description of “Mother” Wollstonecraft represents both women as witches: “a connection between Wollstonecraft and Martineau’s endorsement of population control is drawn obliquely by hinting at traditional beliefs that witches had the capability, and often the malice, to prevent conception” (Ernstrom 280).[11] Along with this long-standing male anxiety, the reference to Wollstonecraft also evokes the 1790s conservative fear that radical writings threatened to destroy British society. Furthermore, “veiled with the decent covering of silence” echoes Edmund Burke’s famous lament for “the age of chivalry” in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790): “all the decent drapery of life is to be rudely torn off” (447). For Maginn, as for Burke, the application of Reason to the “mystical” aspects of society – rank, gender, sexuality – can only ever be destructive and degrading. The self-consciously Burkean and “chivalric” attitude that the “Gallery” liked to take towards more tractable female authors than Martineau is apparent in Mahony’s piece on Landon the previous month. After alluding explicitly to Burke’s defence of Marie Antoinette, he suggests that “ten thousand pens should leap out of their inkbottles to pay homage to L.E.L. In Burke’s time, Jacobinism had banished chivalry — at least, out of France — and the swords remained unbared for their queen; we shall prove, that our pens shall be uninked for the poetess” (433). Starting with Burke’s famously phallic image of swords leaping from their scabbards in defence of Marie Antoinette, Mahony’s metaphor outrageously conflates writing and male sexuality. “Uninked” describes both phallic exposure (taking the pens out of the inkbottles) and ejaculation (disgorging the ink on to the page). The women writers who deserve to be defended from journalistic attack are those that male critics want to sleep with. Martineau is not one of those writers, and her treatment of sexual desire is anathema to Fraser’s: not merely because she is an unmarried young woman and a Utilitarian, but because it is earnest and rational, rather than sentimental (like Landon’s or Sappho’s), or ironically “chivalric” (like Mahony’s or Maginn’s).

Although several critics have addressed aspects of the representation of women in Fraser’s Magazine, I am not aware of any sustained analysis of “Regina’s Maids of Honour” (image 4), the female counterpart of “The Fraserians,” which comprised all the women writers who had appeared in Maginn’s “Gallery,” as well as Anna Maria Hall, who was included a few months later. Yet this article is crucial for understanding not only how the “Gallery’s” mixed rhetoric of chivalry and prurience operated both to restrict and expose its female subjects, but also Maginn’s intense self-consciousness about this process. Whereas “The Fraserians” shows the magazine’s male contributors enjoying a raucous, alcohol-soaked dinner, a large and spectacular assertion of the journal’s claims to genius, the “Maids of Honour” take part in a genteel drawing-room tea party. The participants, from left to right, are Hall, Landon, Mitford, Lady Morgan, Martineau, Jane Porter, Norton, and Countess Marguerite Blessington. In contrast to the openness of the picture of “The Fraserians”, which invites the viewer to participate in the fun, “Regina’s Maids of Honour” is given a frame and a relatively detailed backdrop, which serves to emphasize that it depicts the enclosed private space of the home, and turns the viewer into a voyeur, peeping through the keyhole.

Image 4

[Daniel Maclise]. “Regina’s Maids of Honour.” Fraser’s Magazine 13 (January 1836). Reproduced from William Bates (1891). The Maclise Portrait-Gallery. London: Chatto & Windus.

The accompanying article, written in rhyming prose, is Maginn at his ingenious worst:

What are they doing? what they should; with volant tongue and chatty cheer, welcoming in, by prattle good, or witty phrase, or comment shrewd, the opening of the gay new year. Mrs. Hall, so fair and fine, bids her brilliant eyes to glow,- eyes the brightest of the nine would be but too proud to shew. Outlaw he, and Buccaneer, who’d refuse to worship here. And next, the mistress of the shell (not of lobster, but the lyre), see the lovely L. E. L. talks with tongue that will not tire. True, she turns away her face, out of pity to us men; but the swan-like neck we trace, and the figure full of grace, and the mignon hand whose pen wrote the Golden Violet, and the Lit’rary Gazette, and Francesca’s mournful story. (Isn’t she painted con amore?)

“Maids”

These women are not talking about “politics, or political economy, or pugilism”. There are “comments shrewd,” yes, but the emphasis is on light conversation: rapid and flighty (“volant”); relaxed and easy (“chatty”); inconsequential and perhaps rather childish (“prattle”). The women are conducting themselves exactly as they “should” do. Even more so than in other articles in the “Gallery,” Maginn is concerned with his subjects’ physical attractiveness (“fair and fine”, “brilliant eyes”). Throughout “Regina’s Maids of Honour” he conflates references to their works with descriptions of their looks, thereby ensuring that their public lives as writers cannot be separated from the inspection of their bodies by a masculine observer. Literary allusion becomes a means of mediating between public and private personae, and allows male writers and readers freedom to consider women writers as sexually desirable beings. Hence the suggestion that only criminals would refuse to “worship” Hall alludes to her novels, The Outlaw (1832) and The Buccaneer (1832). Similarly, Landon’s poem “A History of the Lyre” (1829) is mentioned with reference to her as a “mistress,” and several other works listed as products of her “mignon [prettily delicate] hand.”

Maginn’s description of “L.E.L.” bears out Anne K. Mellor’s observation that Landon was often represented in the period, and indeed “constructed herself and her poetry”, as an “icon of female beauty” (122).[12] But the ostensibly innocent final sentence of the passage has a dark subtext. Landon had first emerged as a writer in 1820, at the age of eighteen, when her poem “Rome” appeared in the Literary Gazette. Its editor, William Jerdan, became a strong supporter and during the 1820s she was employed as the periodical’s chief reviewer, a remarkable position for a young woman. Landon remained unmarried and throughout her career was dogged by rumours linking her to various men. In 1826, for example, an article in The Wasp suggested she had been absent from Landon because Jerdan had made her pregnant (Greer 17). In 1830 her friends apparently received anonymous letters accusing her of being the mistress of a married man. One possible candidate was Maginn, a close friend who had worked with her on the Literary Gazette; another was Bulwer, with whom she seems to have had a flirtatious friendship. In 1835, further rumours about her relationships with Bulwer, Maginn and Daniel Maclise, the illustrator of the “Gallery,” forced her to break off her engagement with the editor of the Examiner, John Forster.[13] So the question ‘Isn’t she painted con amore?’ is at best insensitive, and at worst seems meant to suggest that the rumours surrounding Landon and Maclise were based on fact. Furthermore, Maginn had made a similar insinuation three years earlier in his literary portrait of Bulwer, when he mentions that Landon had described the author in Romance and Reality (1831): “we shall not say con amore, lest that purely technical phrase should be construed literally” (“E. L. Bulwer” 112).

Maginn was a notorious scandalmonger and Michael Sadleir has argued that he probably wrote, or instructed his associate Charles Westmacott (editor of the scurrilous newspaper, The Age) to write, the letters that so damaged Landon’s reputation in order to revenge himself on her for having rejected his advances (Sadleir 422-6; see also Leighton 54). He also argues that Bulwer may have been involved in thwarting these advances and that this helps to explain the Fraser’s policy of targeting the novelist. This theory does seem to be supported by the first “con amore” remark, and, in that case, “Regina’s Maids of Honour” would be the final twist of the knife after the collapse of Landon’s engagement. However, Sadleir’s claims are highly speculative and are unlikely for several reasons.[14] It seems unnecessary to posit a private animus behind the attacks on Bulwer when his personality and politics made him a natural Fraser’s target. Furthermore, there is no evidence of a breach between Maginn and Landon at any time: Fraser’s generally treats her very positively. The only evidence that Maginn did make offensive advances to Landon is the utterly unreliable testimony many years later of Grantley Berkeley, who hated Maginn. (Following a crushing ad hominem review of his novel Berkeley Castle in the August 1836 number of Fraser’s, Berkeley, a Member of Parliament, horsewhipped the publisher, James Fraser, and fought a duel with Maginn.) There is also no evidence that any of Landon’s friends thought that the letters were by Maginn and, as Malcolm Elwin has suggested, it is even possible that the letters themselves never existed, although the existence of scurrilous rumours surrounding Landon is not in doubt (120).

Putting the issue of the letters to one side, it is certainly possible that Maginn and Landon had some sort of intimate relationship: Landon’s literary executor, Laman Blanchard, wrote to Edward Vaughn Kenealy that he avoided mentioning Maginn in his biography of Landon, “from the knowledge I have of everything relating to him and to her on several grave points of their experience,” although he also emphasized Maginn’s “devotion to her welfare” (quoted in Stephenson 49). Greer notes that in Landon’s fifth Drawing-Room Scrapbook (1836) appears a poem over Maginn’s initials that contains the lines: “O that I could make without hurt to thy fame, / Thy couch to be my couch; and my name thy name” (quoted in Greer 19). So Maginn may well have desired Landon, although Elwin states that “all [his] acquaintances, though commenting on his irresponsibility and fatal failing for the bottle, unanimously testify to his devotion to his wife and children” (117). It seems to me that the “con amore” references should be read as sly, cruel insinuations about the rumours surrounding Landon’s relationships with Bulwer, Maclise, and Maginn himself, rather than as evidence of actual affairs. They do, however, typify the way in which Landon was abused and mistreated by the male literati, even a supposed friend like Maginn.

In 1838, Landon married George Maclean, Governor of Cape Coast Castle in West Africa, but died a few months later of an overdose of prussic acid, which may or may not have been accidental. Mellor argues that

by writing her self as female beauty, Landon effectively wrote herself out of existence: she became a fluid sign in the discourse that constructed her, a discourse that denied her authenticity and overwrote whatever individual voice she might have possessed. For a modern reader, both her life and her poetry finally demonstrate the literally fatal consequences for a woman in the Romantic period who wholly inscribed herself within Burke’s aesthetic category of the beautiful.

123

This seems a little too fluent in its conflation of life and literature. The scandal greatly damaged Landon’s reputation and literary cachet, but there is no way of showing that the contrast between her public and private personae had “literally fatal consequences”. However, as Mellor implies, this contrast was a powerful one. Although Fraser’s represented Landon as an exemplary female genius due to her writing and her looks, in reality she was simply unable to conform to the sentimental stereotype of female authorship put forward in the “Gallery.” Her association with scandalous aristocrats like Lady Caroline Lamb and Countess Blessington; her social spontaneity; and her close friendships with men like Jerdan, Maginn, and Bulwer would have made her a more suitable participant in the boozy dinner depicted in “The Fraserians”, rather than the genteel tea party of “Regina’s Maids of Honour.” But it was impossible for a woman to play the role of the eccentric Bohemian writer during the Romantic period. Even though Landon was generally represented as a female genius – and although a number of men may have treated her as an equal in friendship, if not in print – ultimately she lacked the social privileges that were often allowed to less successful male authors.

Maginn’s construction of female genius as a sexual spectacle is also strongly apparent in his descriptions of Caroline Norton and Marguerite Blessington. And, like Landon, these women were unconventional figures. Norton had been separated from her abusive husband for several years and in June 1836 was to be tried on the charge of “criminal conversation” with Lord Melbourne, then Prime Minister (she was acquitted). Blessington’s husband had died in 1829, but long before then she had formed a scandalous relationship with the Comte D’Orsay. So although “Regina’s Maids of Honour” places women writers in a genteel domestic setting, Maginn also offers his readers a frisson of scandalous excitement with sexualized portrayals of those – Norton, Landon, and Blessington – whose lifestyles challenged the strict boundaries of domestic propriety. I hope that Fraser’s’ double standard is obvious here: women writers have to stay within the private sphere and are to be severely chastised if they write about public subjects. But male writers and readers are at liberty to treat the private lives of women writers as public spectacle, to peek through the keyhole and “unink” their pens. Maginn’s scandalous discourse and his hysterical response to Martineau are two sides of the same coin. His innuendo depends on a culture where public discussion of sexuality is prohibited: the “con amore” reference, for example, simultaneously violates and upholds the boundary between public and private, Burke’s “decent drapery of life.” Martineau’s openness about sexuality and procreation threatens to dissolve this boundary and therefore not only threatens scandalous discourse but also the masculine right to control and produce representations of sexuality and desire. The interesting thing about “Regina’s Maids of Honour” is that it is so self-aware, perhaps even self-mocking, with regard to this. Thus Martineau is represented as refusing to join the trivial chatter of the other characters and to work within the journal’s boundaries for female genius, insisting rather on “meditating, grimly” the bad habit that “people have in this sad earth of putting things into confusion, by giving certain matters birth, in spite of theories Malthusian” (576).

Maginn’s self-consciousness about the way in which this article “peeps” into the private realm and seeks to titillate its readers is also apparent in the account of Blessington:

O, gorgeous Countess! gayer notes for all that’s charming, sweet, and smiling, for her whose pleasant tales our throats are ever of fresh laughs beguiling. Say, shall we call thee bright and fair, enchanting, winning […] Go, try to read, although his quill is too mean and dull what she inspired even in so great a sumph as Willis; and if that Yankee boy admired, who can a Christian person blame, if he, all Countess-smit, pretends that, if she lets him near the flame of her warm glance he’d think it shame that, like her book, she and he should look as nothing nearer than Two friends.

“Maids”

The build up of similar participial adjectives (“charming,” “smiling,” “beguiling,” “enchanting,” “winning”) not only emphasises that Blessington is a flirtatious woman who makes herself delightful to men, but encourages male readers to be delighted by her. Maginn is alluding to, and to some extent parodying, the effusive account of Blessington given by the American journalist Nathaniel Willis in a newspaper article written in 1834, which was incorporated in his book Pencillings By the Way (1835). Willis was a controversial figure because he had breached the bounds of hospitality by publishing details of his encounters as a guest in private houses such as Blessington’s, especially as he was not always diplomatic in his remarks.[15] As Maginn suggests, Willis does indeed dwell on his hostess’s charms, emphasising her “admirable shape”, her “unusually fair skin,” her “head with which it would be difficult to find fault,” the “ripe fulness” of her mouth, her “musical” voice, her elegant manners, and her dress “cut low and folded across her bosom, in a way to show to advantage the round and sculpture-like curve and whiteness of a pair of exquisite shoulders” (Willis 408). Willis is a “sumph” (defined by the OED as a “soft stupid fellow”) not because he desires Blessington, but because his literary expression of that desire is gauche, emasculating, and improper (“Countess-smit”), in contrast to the more controlled, self-conscious and ironic desire exhibited by “Regina’s Maids of Honour.” Whereas Willis is foolish enough to fall for the real Blessington and then to publicize his folly, Maginn finds allure in the authorial persona depicted by Maclise, a figure that lies somewhere between the real and the textual. Hence, as in the descriptions of Landon and Hall, Blessington’s work – her novel The Two Friends (1835) – is only mentioned in relation to her attractiveness to men. Similarly, when Maginn turns to Caroline Norton, the character of the Wandering Jew from her poem The Undying One (1830) is imagined falling in love with her “sunny eyes, her locks of jet” (222).

“Regina’s Maids of Honour” turns female genius into a spectacle for desiring masculine readers, and is highly self-conscious about doing so. It identifies no less than four different ways of writing about erotic desire: Martineau’s “grim,” unfeminine political economy, which fails to recognise the realities of human sexuality, Willis’s “mean and dull” gossip, the sentimental poetry and fiction of Hall, Landon, Norton, and Blessington, and Maginn’s mixture of chivalry and voyeurism. The latter two approaches are acceptable to Fraser’s because they maintain the gendered boundary between public and private. Although Maginn’s conflation of representation and reality, and his scandalous discourse – both encapsulated in the phrase “isn’t she painted con amore?” – might appear to blur this boundary, they actually serve to emphasise it by suggesting that it can only be crossed by male critics and readers in a controlled and ironic fashion, through the use of allusion and innuendo. “Regina’s Maids of Honour” endorses a masculine fantasy of sentimental female authorship, safely enclosed in the private sphere, while hinting that it is indeed a fantasy: the messy reality, as Maginn and his subjects knew only too well, was very different.

The “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters” exemplifies the way in which, during the Romantic period, it became possible to transform authorship into celebrity through a process of what might be termed ‘spectacularisation.’ Verbal and visual representations of certain writers (most notably Byron) as private individuals, which often appeared in the periodical press, helped to mark them out within a massively competitive literary marketplace and linked them to their readers by encouraging what Tom Mole has described as ‘a hermeneutic of intimacy.’[16] This process was always a troubled one, in part because the categories of ‘genius’ and ‘celebrity’ were not easy to reconcile. These representations were beyond any individual’s control, and therefore threatened the authority of authorship even as they celebrated it. Furthermore, they challenged the construction of a clear boundary between public and private spheres. Cultural history tends to represent this boundary as becoming increasingly ossified during the 1830s and 1840s, and perhaps it was this that opened up the increased opportunities for scandal and satire that journalists like Maginn exploited so cleverly. As we have seen, women writers – especially those whose work was intimate and confessional – were especially vulnerable to such exploitation, for their involvement with the literary world in itself threatened their respectability, and yet they could not aspire to the artistic and social freedom that critics often granted to masculine genius.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

This article is a revised and greatly expanded version of a section of my book, Romantic Genius and the Literary Magazine: Biography, Celebrity, Politics. I am grateful to Routledge for permission to reproduce material. I am also grateful to Kiera Chapman for her very helpful comments on an earlier draft.

-

[2]

For an interesting discussion of the “Gallery’s” “iconoclasm” in relationship to Thomas Carlyle’s doctrine of hero-worship, see Salmon 6-9.

-

[3]

Maginn wrote all but five of the eighty-one anonymous portraits. John Gibson Lockhart provided the one of Maginn himself (entitled “The Doctor”) in January 1831. Thomas Carlyle depicted Goethe in March 1832. And Francis Mahony did three: “Miss Landon,” October 1833; “Pierre-Jean de Béranger,” March 1835; “Henry O’Brien,” August 1835.

-

[4]

For an excellent critical overview of the “Gallery” that also discusses the relationship between gender and celebrity, although in rather different terms than I do, see Fisher.

-

[5]

For gender and genius in the period, see Battersby, Elfenbein, Hofkosh, and Ross.

-

[6]

For general accounts of Fraser’s, see Thrall and Van Dann.

-

[7]

Newman gives an acute analysis of the Fraser’s attitude to the novel as a genre, and to Bulwer’s work in particular.

-

[8]

There is still relatively little scholarly work on the literary culture of the 1830s, but see Chittick and Cronin.

-

[9]

For an interesting discussion of Landon’s relationship to the category of the “poetess,” see Stephenson.

-

[10]

The allusions to Hemans and Porden in the Blackwood’s article further support this point. In the John Bull Magazine, also in 1824, Maginn contrasts Landon’s “brilliant” love poetry with their unpalatable works: “For what can a woman well write on but love?” (“The Rhyming Review” 77).

-

[11]

For another discussion of this article, and an acute comparison of the Fraser’s representation of Martineau and Landon, see Sanders.

-

[12]

See Francis for a critique of the limitations of this approach, and an interesting discussion of Landon’s self-consciousness about the “specularisation” of female authors.

-

[13]

For Landon’s life history, see Stephenson, chapter 2.

-

[14]

I am very grateful to David Latané, who is writing a book on Maginn, for pointing out to me some of the flaws in Sadleir’s theory.

-

[15]

For a detailed account of Willis and Blessington, see Sadleir, chapter 2.

-

[16]

An incisive overview of this process can be found in the first chapter of Mole’s Byron’s Romantic Celebrity.

Works Cited

- Battersby, Christine. Gender and Genius. London: The Women’s Press, 1989.

- [Bulwer, Edward Lytton]. “Romance and Reality. By L. E. L.” New Monthly Magazine 32 (December 1831): 545-551.

- Burke, Edmund. The Portable Edmund Burke. Ed. Isaac Kramnick. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1999.

- Chittick, Kathryn. Dickens and the 1830s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Cronin, Richard. Romantic Victorians: English Literature, 1824-1840. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002.

- Cross, Nigel. The Common Writer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- De Groot, H. B. “The Status of the Poet in an Age of Brass: Isaac D’Israeli, Peacock, W. J. Fox and Others.” Victorian Periodicals Newsletter 10 (1977): 106-29.

- Elfenbein, Andrew. Romantic Genius: The Prehistory of a Homosexual Role. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- Elwin, Malcolm. Victorian Wallflowers. London: Jonathan Cape, 1934.

- Ernstrom, Adele M. “The Afterlife of Mary Wollstonecraft and Anna Jameson’s Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada.” Women’s Writing 4.2 (1997): 277-97.

- “The Female Character.” Fraser’s Magazine 7 (May 1833): 591-601.

- Fisher, Judith L. “‘In the Present Famine of Anything Substantial’: Fraser’s Portraits and the Construction of Literary Celebrity; or, ‘Personality, Personality is the Appetite of the Age’.” Victorian Periodicals Review 39.2 (2006): 97-135.

- Francis, Emma. “Letitia Landon: Public Fantasy and the Private Sphere.” Essays and Studies 51 (1998): 93-115.

- Greer, Germaine. “The Tulsa Center for the Study of Women’s Literature: What We Are Doing and Why We Are Doing It.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 1.1 (1982): 5-26.

- Hemingway, Andrew. “Genius Gender and Progress: Benthamism and the Arts in the 1820s.” Art History 16.4 (1992): 619-46.

- [Heraud, John Abraham]. “On Poetic Genius, Considered as a Creative Power”. Fraser’s Magazine 1 (February 1830): 56-63.

- Hofkosh, Sonia. Sexual Politics and the Romantic Author. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Lapp, Robert. “Romanticism Repackaged: The New Faces of ‘Old Man’ Coleridge in Fraser’s Magazine, 1830-35.” European Romantic Review 11 (2000): 235-47.

- Leary, Patrick. “Fraser’s Magazine and the Literary Life, 1830-1847.” Victorian Periodicals Review 27 (Summer 1994): 105-26.

- Leighton, Angela. Victorian Women Poets: Writing Against the Heart. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992.

- [Maginn, William]. “The Rhyming Review.” John Bull Magazine 1 (August 1824): 76-77.

- ———. “The Election of Editor for Fraser’s Magazine.” Fraser’s Magazine 1 (May 1830): 496-508; 2 (July 1830): 738-57; 2 (September 1830): 238-50.

- ———. “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters. No. X. Caroline Norton.” Fraser’s Magazine 3 (March 1831): 222.

- ———. “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters. No. XII. Mary Russell Mitford.” Fraser’s Magazine 3 (May 1831): 410.

- ———. “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters. No. XXVII. E. L. Bulwer.” Fraser’s Magazine 6 (August 1832): 112.

- ———. “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters. No. XLII. Miss Harriet Martineau.” Fraser’s Magazine 8 (November 1833): 576.

- ———. “Regina’s Maids of Honour.” Fraser’s Magazine 13 (January 1836): 80.

- [Maginn, William, and Lockhart, John Gibson]. “ODoherty’s Maxims. Part One”. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 15 (May 1824): 599-605.

- [Mahony, Francis]. “Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters. No. XLI. Miss Landon.” Fraser’s Magazine 8 (October 1833): 433.

- Mellor, Anne K. Romanticism and Gender. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Mole, Tom. Byron’s Romantic Celebrity. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007.

- Newman, Rebecca Edwards. “‘Prosecuting the Onus Criminus’: Early Criticism of the Novel in Fraser’s Magazine.” Victorian Periodicals Review 35.4 (2002): 401-419.

- Riess, Daniel. “Laetitia [sic] Landon and the Dawn of English Post-Romanticism.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 36.4 (1996): 807-827.

- Ross, Marlon B. The Contours of Masculine Desire: Romanticism and the Rise of Women’s Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Sadleir, Michael. Bulwer and His Wife: A Panorama. London: Constable, 1931.

- ———. Blessington-D’Orsay: A Masquerade. London: Constable, 1933.

- Salmon, Richard. “Thomas Carlyle and the Idolatry of the Man of Letters.” Journal of Victorian Culture 7.1 (2002): 1-22.

- Sanders, Valerie. “‘Meteor Wreaths’: Harriet Martineau, ‘L.E.L.’, Fame and Fraser’s Magazine.” Critical Survey 13.2 (2001): 42-60.

- Stephenson, Glennis. Letitia Landon: The Woman Behind L.E.L.. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995.

- Thrall, Miriam J. Rebellious Fraser’s. New York: Columbia University Press, 1934.

- Van Dann, J. “Fraser’s Magazine.” British Literary Magazines: The Romantic Age, 1789-1836. Ed. Alvin Sullivan. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1983. 171-175.

- Willis, Nathaniel. Pencillings by the Way, London: T. Werner Laurie, 1942.

List of figures

Image 1

Image 2

Image 3

Image 4