Abstracts

Abstract

Wherever the reader may sit on the spectrum of international relations theories, it should hold that whether a state complies with international human rights norms or not translates some other reality beyond the simple act of (non-)conformity. Focusing on such social meanings, constructivism allows to demonstrate how compliance is constitutive of normativity. We combine this constructivist approach with a jaded outlook in order to find out the role contestation, compliance’s cynical ugly twin, plays in normativity. This paper exploits empirical observations concerning contestation in order to address its normative implications, arguing that, up to a certain point contestation nourishes normativity as the norm is taken seriously enough to contest, but that beyond the contestation threshold it becomes damaging. Taking the norms at three stages of implementation, we evaluate their contestation, and therefore, normativity levels. Firstly, we compare UN resolutions on LGBTI+ rights and the right to development as social norms by inspecting voting records. Secondly, we study non-ratifications and reservations made to UN human rights treaties as normativity indicators for emergent legal norms, acknowledging the latter’s unique challenges. Lastly, we take a look at violations of these same treaties as contestation of an established legal norm while questioning the viability of treaty body decisions as a normativity indicator. We conclude that, providing the right indicator is chosen, the contestation threshold is a particularly useful tool when it comes to comparing two or more norms at the same stage of implementation, and only for comparison purposes until the threshold is better quantified.

Résumé

Peu importe où se situe le lecteur dans l’éventail des théories des relations internationales, il est reconnu que le fait qu’un État se conforme ou non aux normes internationales en matière de droits humains traduit une réalité au-delà du simple acte de (non-)conformité. En se concentrant sur de telles significations sociales, le constructivisme permet de démontrer comment la conformité est constitutive de normativité. Nous combinons cette approche constructiviste avec un regard blasé afin de découvrir le rôle que joue la contestation, la jumelle maléfique et cynique de la conformité, dans la normativité. Cet article exploite les observations empiriques concernant la contestation afin d’aborder ses implications normatives, en faisant valoir que jusqu’à un certain point, la contestation nourrit la normativité puisque la norme est prise suffisamment au sérieux pour être contestée, mais qu’au-delà du seuil de contestation, elle devient dommageable. En prenant les normes à trois stades de leur mise en oeuvre, nous évaluons leur niveau de contestation, et donc de normativité. Tout d’abord, nous comparons les résolutions de l’ONU sur les droits des LGBTI+ et le droit au développement en tant que normes sociales, en examinant leurs résultats de vote. Ensuite, nous étudions les non-ratifications et les réserves faites aux traités de droits humains de l’ONU comme indicateurs de normativité pour les normes juridiques émergentes, en reconnaissant les défis spécifiques aux réserves. Enfin, nous examinons les violations de ces mêmes traités en tant que contestation d’une norme juridique établie tout en remettant en cause la viabilité des décisions des organes de traités en tant qu’indicateur de normativité. Nous concluons qu’à condition de choisir le bon indicateur, le seuil de contestation est un outil particulièrement utile lorsqu’il s’agit de comparer deux ou plusieurs normes à un même stade de leur mise en oeuvre, et uniquement à des fins de comparaison jusqu’à ce que le seuil soit mieux quantifié.

Resumen

Independientemente del lugar que ocupe el lector en el espectro de la teoría de las relaciones internacionales, se reconoce que el hecho de que un Estado cumpla o no con las normas internacionales de derechos humanos refleja una realidad que va más allá del mero acto de (in-)cumplimiento. Al centrarse en tales significados sociales, el constructivismo nos permite demostrar cómo el cumplimiento es constitutivo de la normatividad. Combinamos este enfoque constructivista con una mirada displicente para descubrir el papel que la contestación, el gemelo malvado y cínico del conformismo, desempeña en la normatividad. Este artículo aprovecha las observaciones empíricas sobre la contestación para abordar sus implicaciones normativas, argumentando que, hasta cierto punto, la contestación alimenta la norma, ya que ésta se toma lo suficientemente en serio para ser contestada, pero más allá del umbral de la contestación, se vuelve perjudicial. Al tomar las normas en tres etapas de su aplicación, evaluamos su nivel de impugnación y, por tanto, de normatividad. En primer lugar, comparamos las resoluciones de la ONU sobre los derechos LGBTI+ y el derecho al desarrollo como normas sociales, examinando los resultados de sus votaciones. En segundo lugar, examinamos las no ratificaciones y las reservas a los tratados de derechos humanos de la ONU como indicadores de normatividad para las normas jurídicas emergentes, reconociendo los desafíos específicos de las reservas. Por último, examinamos las violaciones de estos mismos tratados como un desafío a una norma jurídica establecida, al tiempo que cuestionamos la viabilidad de las decisiones de los órganos de tratados como indicador de normatividad. Concluimos que, siempre que se elija el indicador adecuado, el umbral de contestación es una herramienta especialmente útil cuando se comparan dos o más normas en la misma fase de su aplicación, y sólo con fines comparativos hasta que se cuantifique con mayor precisión el umbral.

Article body

I. Introduction

Life is difficult for cynics[1]; always doubting everyone’s intentions, asking the questions nobody wants to. International relations are no exception to this jaded outlook. Rather, it is very fertile soil. One could even take the radical route and argue that international relations make close to no sense; we take states as if they were unified and logical entities that conduct themselves in a certain fashion in order to achieve a certain goal, bestowing upon them human characteristics, we talk about “behaviour” and “motive” and “ethics”.[2]

Once this preliminary obstacle surpassed, international relations theory can be an amusement park for cynics; there is something for almost everyone. Be it the so-called realism that sees anarchy everywhere or a more critical theory, like the Marxist or the feminist approaches challenging the very foundations of the discipline, you will find a ride that suits you.

This somewhat anthropomorphic approach allows us to look behind the veil and see that there are human minds behind what we call a “state”, and lets us study how states conduct themselves in order to explain the hidden reasons and motivations. It is almost the study of state psychology—with a behavioural approach to that.[3] So how does a cynic come to be a constructivist in international relations theory when the realist alternative seems to glorify chaos[4], seemingly more suitable?

It is indeed a shame that the realist school coined the name, and therefore the assumption of realism. Besides being reductive, realism is something of an Idealtypus as Max Weber would put it. Just like the all-rational homo economicus that the 18th and 19th century economists conceived, real states do not behave the radical way realists expect and want them to. Realists were just at the right place at the right time, the fall of idealism with the Second World War was the perfect terrain for power politics to flourish.

But one doesn’t have to be a complete pessimist to be a cynic. Institutionalism provides a first step by tempering realism as while they concede that the anarchic structure proposed to explain international relations is true, they also nuance it by admitting that cooperation is possible.[5] We believe constructivism, even if not a theory per se, could be the next step, as it shifts the focus from objective facts about the world onto their social meanings.[6]

Constructivists’ main claim is that the anarchy that realists adore so much is constructed, instead of being inherent to the system, which gives value to norms. This is one of the inevitable consequences of living and socialising in a group. There is something beyond the mere rule that makes us accept it. This is especially easy to observe when new states come into the international arena, and follow the rules established before them by those who had to coexist in a society. So a constructivist point of view, in which compliance can play a central role[7], makes sense for a cynic.

A. Why Contestation?

Compliance is defined as “the degree to which states adjust their behaviour to the provisions contained in the international agreements they have entered into”.[8] Whilst trying to make sense of the world through this “psychology for states” subject, scholars generated theories that explained why states act one way or another and thus compliance became an important indicator, a language of sorts of international relations. If a state complied or not became telling, translating some other reality beyond the simple act of conformity. As Lutmar and Corneiro note,

[p]olitical scientists and international law scholars have enhanced our understanding of the conditions under which states’ compliance with international commitments is most likely to occur. Given the anarchic nature of the international system, and the lack of centralized enforcement, scholars have questioned the rationale for state compliance with international agreements they entered into. Keohane (1984, p. 99) mentions “the puzzle of compliance is why governments, seeking to promote their own interests, ever comply with rules that are not in their immediate self-interest.” This puzzle raises related questions such as: When do states comply? Why do they comply in some cases but not in others?[9]

The answer might be strategy or reputation-related but these existential questions are not the subject of this study. We make “the distinction between the existence of international law and its effectiveness, and [conclude], maybe not surprisingly, that states comply out of self-interest. Hence compliance tells us very little, if anything, about the usefulness of the law”.[10] But there is no denying that state practice, may it be in a positive or negative way, contributes to shaping the norm. What interests us is how compliance, or lack thereof as will be discussed below, affects the norm itself, participating to its normativity. It is therefore not the reason, but the effect of state practice that we will study, as “norms entail a dual quality (i.e. they are both structuring and constructed)”.[11]

As “norms of appropriateness have a significant impact on political behaviour; […] real power flows from the ability to define such norms”.[12] The ability to create new norms or to define the existing ones brings in what Pierre Bourdieu would call capital symbolique, which in turn translates soft power.[13]

This paper tells the untold story of the other side of the coin, compliance’s cynical ugly twin: contestation. It seeks to add to how contestation—through its shared symbolic capital with compliance—is constitutive of normativity and therefore reinforces constructivist theory, by exploiting Antje Wiener’s work. “A bifocal—normative and empirical—approach to norms […] aims to move beyond empirical observations about how norms work (i.e. how given norms influence behaviour), and thereby address the more substantial normative question about whose norms count (i.e. who has access to contestation)”.[14] Understanding what is contested seems, if not more, almost as revealing as what is complied with. It therefore makes perfect sense to combine these cynical and constructivist approaches, through contestation.

B. Defining Contestation

It is quite difficult to give a concise definition of contestation, but Antje Wiener’s theory submits that “in international relations contestation by and large involves the range of social practices, which discursively express disapproval of norms”.[15] Wiener also distinguishes four modes of contestation:

Accordingly four modes of contestation can be distinguished with reference to the literatures in law, political science, political theory and political sociology, respectively. They include first, arbitration as the legal mode of contestation involves addressing and weighing the pros and cons of court related processes according to formal legal codes; second, deliberation as the political mode of contestation involves addressing rules and regulations with regard to transnational regimes according to semi-formal soft institutional codes; third, justification as a moral mode of contestation according to moral codes involves questioning principles of justice, and, fourth contention as the societal practice of contestation critically questions societal rules, regulations or procedures by engaging multiple codes in non-formal environments.[16]

Thus, all action or position taken against the norm somewhat contributes to its normativity. Wiener furthermore distinguishes between those who simply don’t comply with the norm, and those who don’t comply but who also contest verbally, so it is done “either explicitly (by contention, objection, questioning or deliberation) or implicitly (through neglect, negation or disregard)”.[17] Besides these two classifications on method, Wiener observes a temporal third one, between proactive contestation, before the formal establishment of the norm, and reactive contestation afterwards.[18]

She confronts the three stages of norm implementation (constituting, negotiating, implementing) to the three scales of global order (macro, meso, micro) to constitute a cycle-grid model[19] and holds that wider-ranging norms provoke less reactive contestation, whereas narrower norms provoke more. For example, human rights are rarely contested as a concept[20], but in application, a specific right will be more prone to contestations.[21] Wiener develops her theory focusing on the legitimacy gap that affects the norms that are neither fundamental principles, nor specific regulations, but simply middle-of-the-road organising principles.

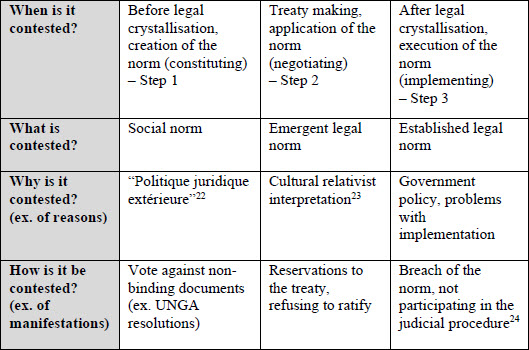

Instead of continuing with Wiener’s theory, we will here take contestation at the three stages of norm implementation and look at it through an international lawyer’s eyes with a touch of international relations theory—granting that norms have value even before their formal recognition without the necessity to resort to abstract concepts such as soft law (Table 1).

There are multiple questions left to be answered, depending on the stage of implementation. What are the justifications, legal, paralegal or extra-legal, of this contestation? And what legal means do states have to contest? These are not the subject here.

Table 1

C. The Working Hypothesis

Inspired by Wiener’s bifocal approach, we will exploit empirical observations[25] in order to address the normative interrogations. Building on this theory, our hypothesis is that there is a threshold of contestation: up to a certain point contestation nourishes normativity as the norm is taken seriously enough to contest, but beyond that limit contestation becomes damaging.[26] The idea that contestation can be nourishing or damaging is not new[27], but the vocabulary of a threshold has been rarely used.[28] We argue that this threshold is a function of two variables; the intensity of the contestation (including whether it’s explicit or implicit), and the number of contesters (Table 2). Quantification of such abstract issues is always difficult, but it is helpful in terms of comparison. This proposed threshold does not have to be an empirical value, it can merely be a practical guide.

One could also argue that the quality of contesters (the question of who is contesting) should also be taken into account. This is admittedly true, but this parameter is even more difficult to quantify. Surely one cannot equate a sstate’s contestation to an NGO’s, neither a huge military force’s to a microstate’s, but there is no viable way to translate this into objective quantifiable data in the scope of this paper.

Table 2

The contestation threshold

II. Comparing the Normativity of Human Rights Norms through Contestation

For the purposes of the demonstration here, emphasis will be put on arbitration and deliberation, as these are the most commonly used types of contestation in legal realms, especially in international human rights law. Although justification, as the moral mode of contestation might come into play in law especially in non-positivistic approaches,despite the regular questioning of the legitimacy of its institutions and of certain liberties themselves it is safe to say that human rights, as a fundamental principle in the macro scale of global order in Wiener’s terms, are living a golden era, as statistical studies in latent indicators from 1949 to 2013 show improving global trends.[29] As mentioned above, since human rights are rarely contested as a concept, justification is not one of the principal modes of contestation regarding the subject at hand.

The best demonstration of different levels of normativity will be a thematic comparison through case studies. To this end, the examples chosen will all be United Nations (UN) documents, as in terms of assembly and mandate it is the largest international organisation, with 193 members and objectives as broad as maintaining international peace and security, developing friendly relations among nations, and achieving international co-operation in solving international problems.[30] The three sections, corresponding to the three steps of contestation will study UN General Assembly (UNGA) documents, and some of the core human rights treaties.

A. Social Norms (Step 1)

In this first section, we will confront two different sets of social norms in order to show their varying degrees of normativity.

First will be addressed LGBTI+ rights. According to quantitative research on United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) resolutions, one could argue that only the European Union (EU) shows support to rights on sexual orientation and gender identity, with a participation rate (a metric based on the number of states sponsoring the resolution per total number of states in the group) of 0.91, the closest second being the group of Latin American and Caribbean states (GRULAC) with 0.24, where the same reference point is 0.00 for the group of Arab states, 0.01 for the African group, 0.02 for the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and 0.05 for the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).[31]

Secondly, and according to the same study, development as a third-generation right has the highest support, with participation rates as high as 1.00 (group of Arab states and the NAM), or 0.98 (the African group), followed by 0.93 (OIC) and 0.83 (GRULAC), with oddly enough the EU falling behind with a participation rate of 0.01.[32] This further proves the point that the question of the quality of the contester may become irrelevant in face of such huge disparities.

Taking these numbers into account, we will widen the span and look primarily at resolutions from UNGA, as it is the “chief deliberative, policymaking and representative organ of the United Nations”[33] where all the Member states are represented.

Setting some unofficial statements by member states[34] aside, LGBTI+ rights appear twice in UNGA resolutions, both on the subject of extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions. The first one is from 2003 and reads that the General Assembly “reaffirms the obligation of Governments to ensure the protection of the right to life of all persons under their jurisdiction, and calls upon Governments concerned to investigate promptly and thoroughly […] all killings committed for any discriminatory reason, including sexual orientation.”[35] This resolution is reiterated in 2014 with almost the exact wording, as the UNGA “urges all states […] (b) to ensure the effective protection of the right to life of all persons, to conduct, when required by obligations under international law, prompt, exhaustive and impartial investigations into all killings, including those targeted at specific groups of persons, […] because of their sexual orientation or gender identity”.[36] The 2003 resolution was voted with 130 in favour and 49 abstentions (27% contestation rate, counting abstentions as contestation), whereas the 2014 one with 122 in favour and 66 abstentions (35% contestation rate). However, as these resolutions are not specifically on the issue of LGBTI+ rights, one cannot deduce much in terms of normativity, which is why we have to turn our gaze to the work of the HRC.

There are two resolutions of the HRC on “human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity”. The first one is from 2011, requesting the finalisation of the report on discriminatory laws and practices and acts of violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, and is passed with 23 votes in favour and 19 against with 3 abstentions.[37] The second one from 2014 takes note of the aforementioned report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and of the panel discussions that followed[38] and is passed with 25 votes in favour and 14 against with 7 abstentions.[39] The voting record shows that there is much left to be desired, as the contestation rates are respectively 48 and 45%. Besides, even though it is an undeniably important organ, one cannot argue that the HRC has the representativity and therefore the legitimacy of the UNGA, which takes away from the normativity.

The two other HRC resolutions on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity do not offer much relief. The 2016 resolution creating the position of the Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity was passed with 23 votes in favour to 18 against with 6 abstentions (51% contestation rate)[40]. The mandate was extended in 2019, with only 27 votes in favour, but 12 against and 7 abstentions (41% contestation rate).[41]

Although not a UN document, one cannot mention LGBTI+ rights and not refer to the Yogyakarta Principles. The fruit of a meeting of the International Commission of Jurists and signed by many scholars, practitioners and experts such as Mary Robinson, Manfred Nowak and Philip Alston to name a few, the reference to this document by Special Rapporteur on the right to education was met with much criticism. The 2010 report cites the principles twice: “23. […] A very important contribution to thinking in this area was made by the 2006 Yogyakarta Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity.” and “67. […] The aforementioned Yogyakarta Principles are a fundamental tool for inclusion of the diversity perspective in the public policies that have to be taken into account in education”.[42] During the discussion of the report, many states refused the inclusion of sexual education, arguing that the Special Rapporteur had exceeded the limits of his mandate, but some criticised precisely the reference to the Yogyakarta Principles. Specifically, the Russian representative said:

As justification for his conclusions, he had cited numerous documents which had not been agreed to at the intergovernmental level, and which therefore could not be considered as authoritative expressions of the opinion of the international community. In particular, he referred to the Yogyakarta Principles and also to the International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education.[43]

The representative of Malawi, speaking on behalf of African states underlined that:

the report also […] propagated controversial and unrecognized principles, including the so-called Yogyakarta Principles, to justify his personal opinion. Such an approach only served to undermine the credibility of the whole special procedures system and should not be tolerated.[44]

While unquantifiable, the hostile language used, especially by the Malawian representative, is testament to the reception of LGBTI+ rights at the UN. Thus, with this level of high intensity contestation, LGBTI+ rights are quite low on the normativity scale.

Next in order is the right to development. While there are reports and resolutions at the HRC level similar to LGBTI+ rights[45], there are also many other instruments adopted by the UNGA. These are still mere declarations, but as it is the first step of contestation one shouldn’t expect to be dealing with hard law.

First, comes the Declaration on the Right to Development (hereafter, “Declaration”) adopted in 1986 with 146 votes in favour, 8 abstentions, and a single vote against, from the United States.[46] While little remains to be demonstrated after this extremely revealing voting record and 0,05% contestation rate, many other instruments touch on the right to development.

There is a series of declarations that refer to development or the right to development, including; the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development adopted at the Conference on Environment and Development in June 1992 (principles 1 and 3)[47], the 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (article 10)[48], the United Nations Millennium Declaration of 2000 (points 11 and 24)[49], the 2002 Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development (point 11)[50], or the 2005 World Summit Outcome (point 123).[51] These declarations, while adopted without vote, are the result of a non-negligible consensus.

Although not solely on the right to development, the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also makes many references to development and recognises the right to development at its article 23.[52] This resolution was adopted with 143 votes in favour, 11 abstentions and 4 votes against, coming from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, all of which are states representing important indigenous populations, but whose abstentions incur a mere 0,09% contestation rate.[53] This is once again an example supporting the irrelevance of the quality of the contester before the substantial number of non-contesters.

Last, and maybe least, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas of 2018 also makes multiple references to the right to development, unfortunately with only 121 votes in favour, 8 against and 54 abstentions; although in this case, the ratio does not significantly hurt the normativity of the right to development as it was not the declaration’s central issue.[54]

There are also two regional binding documents that might be relevant here, even if the norm isn't universally binding yet. While the Arab Charter on Human Rights simply mentions development[55], the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights states in its preamble that member states are “convinced that it is henceforth essential to pay a particular attention to the right to development”, only to affirm in article 22(2) that “states shall have the duty, individually or collectively, to ensure the exercise of the right to development”.[56]

***

This observation demonstrates well the hypothesis. The right to development, although soft law at best, has a much stronger foundation than LGBTI+ rights.

One could argue that this is an effect of the elusive nature of the right to development, that it is not well defined[57], that it only refers to other more tangible rights such as self-determination (art. 1 of the Declaration on the Right to Development), non-discrimination (art. 6 of the Declaration)[58] or disarmament (art. 7 of the Declaration).[59] It could be that as the right to development itself is quite vague, states are less reluctant to vote in favour of resolutions on the matter.

However, the counterargument that states would be more reluctant to vote in favour of a less specific instrument is also, if not more, just as probable. Furthermore, the chasm between the two examples is augmented because these elements of the right to development are binding in other instruments of international law[60], making it even more normative, while one cannot say the same for LGBTI+ rights. Therefore, the right to development would be placed below the contestation threshold in the higher normativity zone, whereas LGBTI+ rights would be placed above, in the lower normativity zone (Table 3).

Table 3

Step 1 case studies

B. Emergent Legal Norms (Step 2)

This second section is dedicated to comparing high and low normativity in human rights treaties. As mentioned above (Table 1), this will be through multiple examples around non-ratification and reservations.

1. Non-Ratifications as a Normativity Indicator

One might think that ratification always improves respect for the rights protected in a treaty. That is not exactly the case, but the assumption is not entirely false either. Neumayer has found “only few cases, in which treaty ratification has unconditional beneficial effects on human rights. […] Despite these difficulties [they have] demonstrated quantitatively and rigorously that ratification of human rights treaties often does improve respect for human rights”.[61] Following the cynical outlook of this paper, “in any event, this much is clear: we still do not satisfactorily know the full effects of human rights treaties. Absent such knowledge, the best assumption remains the conventional one: human rights treaties advance the cause they seek to promote, not the other way around”.[62] We will therefore concentrate on the status of non-ratification of two human rights treaties: the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (CMW)[63] and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)[64], adopted 13 months apart from each other. While these are not emergent norms today—at least the CRC, the ratification data will specifically look into this early period.

The CMW has been ratified by 55 states parties. Keeping in mind that the UN has 193 member states[65], that means 138 states that haven’t ratified the CMW, and a 71% non-ratification rate. What adds to these numbers is the 13 years that it took for its entry into force with the 20th ratification, and also the fact that its individual complaint system is still not operative, but will be once the tenth state party makes the necessary declaration under article 77. Compared to other more established human rights treaties, the CMW is almost stuck in the treaty-making phase.

Contrarily, the CRC is the most universally ratified human rights treaty, with 196 states parties—all but one member of the UN, the United States, but with the addition of the Cook Islands, the Holy See, Niue and Palestine, which are not member. Repeating the same calculation as above and taking into account only UN members for purposes of fairness, the CRC has a non-ratification rate of 0.005%, which is less than one in 14 thousand compared to the CMW. Unsurprisingly, it took merely 10 months to achieve the 20 ratifications necessary for the entry into force[66] and only six of the 196 states parties ratified the CRC after 1997.[67]

Against what most legal experts might have you believe, not all international treaties are created equal. While the extremely low contestation rate of the CRC makes it a very solid instrument whose normativity is not challenged at all, the CMW seems like a shadow of a treaty in comparison. These findings cannot but have an effect of how the treaties are applied, and also perceived, which is crucial in international law where “naming and shaming” is a type of law enforcement.[68] Thus, while the CRC is above the normativity threshold, the CMW isn’t.

3. Reservations as a Normativity Indicator

The second factor that will be taken into consideration in this section is the number of reservations to treaties. Still looking at the core UN human rights treaties, we observe that the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[69], the CRC and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)[70] have the most reservations.[71] In contrast, the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CPED)[72], the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)[73], and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)[74] have the least.[75] As reservations are taken as a form of contestation in this hypothesis, this would mean that the former treaties are less normative and the latter, more. Unfortunately, the issue with reservations turns out to be not as simple, as just like treaties, not all reservations are created equal.

The nature of the article of which the reservation modifies the effect is decisive. Is it an article on dispute resolution? Is it a substantive right? The distinction between dispositions can also be taken a step further by distinguishing provisions that constitute obligations and those that constitute demanding obligations.[76] The consequence of the reservation on the normativity of the treaty cannot be deemed the same in these different cases.

On this point, Neumayer explains more generally that “clearly, the results […] do not imply that those who are concerned that the widespread use of [reservations, understandings, and declarations (RUDs)] in international human rights treaties is detrimental to the regime, if perhaps only in the long run, are wrong. This may or may not be the case”.[77] Adding this to the different types of dispositions, the effect of reservations on human rights treaties seems hardly measurable. Therefore, normativity-wise reservations are not a reliable parameter, at least not for comparing treaties.

Yet, they would surely be suitable to determine the normativity of a particular clause. For example, among the 189 states parties to the CEDAW, 40 had made reservations to article 29 paragraph 1 on dispute resolution by 2010[78], which is a 21% of contestation rate. On the other hand, 29 had made a reservation to article 16, all paragraphs combined[79], on the elimination of discrimination against women “in all matters relating to marriage and family relations”.[80] Surely the effect of these reservations on the normativity of the treaty will not be the same. On the other hand, article 13 on the elimination of discrimination against women in all areas of economic and social life has only 2 reservations, which is a contestation rate of 1% compared to the 15% of article 16, allowing us to conclude that article 13 is more normative than article 16.

C. Established Legal Norms (Step 3)

The third and final section will be on contestation of established legal norms, in this case, some of the same UN human rights treaties as in the section above. Although there are many types of human rights monitoring, most are not based on verdicts but more on different structural and processual indicators[81]. In order to identify human rights violations, we will look at UN treaty body jurisprudence of individual communications, as these provide a more stable and precise point of data than the universal periodic review or the periodic reports of committees.

Beforehand, an issue needs to be addressed. In legal doctrine, the impact of these treaty body decisions is, at the very least, controversial. Still, it is not so obvious that the decisions of treaty bodies are not binding and that they would have only moral, political or diplomatic significance.[82] As such, even those who insist that they are not legally binding admit that states “have an obligation to take the treaty bodies’ findings seriously”[83], as these communications are “to a great extent comparable to judicial decisions”[84], as “the human rights treaty bodies serve the same functions as formal international courts and tribunals in interpreting and applying international law in complaints against states parties”.[85] Moreover, the International Court of Justice has stated on this issue that “it believes that it should ascribe great weight to the interpretation adopted by this independent body that was established specifically to supervise the application of that treaty”[86] and the Human Rights Committee has asserted in a general comment that:

While the function of the Human Rights Committee in considering individual communications is not, as such, that of a judicial body, the views issued by the Committee under the Optional Protocol exhibit some of the principal characteristics of a judicial decision. They are arrived at in a judicial spirit, including the impartiality and independence of Committee members, the considered interpretation of the language of the Covenant, and the determinative character of the decisions.[87]

The statistics around the individual complaint procedures are not very detailed. Only 5 of the 9 treaty bodies has statistical surveys on individual complaints with data on their outcome, with some of them dating as far back as 2014.[90] Noting that some of the statistical surveys, once confronted with the jurisprudence database, became unusable for the interests of this comparison[91], we will only take into account decisions adopted on the merits, and leaving aside discontinuance and inadmissibility decisions.

According to data from January 2020, the CEDAW Committee has a contestation rate of 86%, with 32 violation decisions out of 37.[92] Some other committees also have high contestation rates but a low number of total cases, the CRC Committee for example has a contestation rate of 100%, but it has only adopted 11 views. Likewise, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has a contestation rate of 85% but only 7 views in total.[93]

On the other hand, the CAT Committee has a contestation rate of only 39% according to the statistical survey from August 2015, with 107 violations to 165 non-violations out of a total of 272 cases.[94] They have adopted 84 decisions since then. While the specific definition and the demanding legal standard for torture might explain this, following the first two sections we can conclude that the CAT is below the contestation threshold, whereas the CRC, the CEDAW and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights[95] are beyond.

One could also look at treaty body contestation based on how many states refuse to accept their jurisdiction, or on implementation of treaty body decisions in order to conclude to the high or low normativity of their views. Unfortunately, neither would have a very positive outcome, as “acceptance is far from universal, as several major states, such as the United States of America, India, and China, and states in certain regions, such as the Middle East, have not accepted any individual complaints procedures”[96] and “only a minority of the findings are satisfactorily implemented”.[97]

III. Conclusion

The working hypothesis turned out to be useful, at least with regard to the first step of contestation. For the second step, while reservations were a challenge, adhesions to treaties were found to be a good marker. Lastly, the hypothesis served in comparing treaties but treaty body decisions turned out to be a questionable indicator.

States will be states. They will not comply, unless they have to, or sometimes even when they have to in legal terms. The cynic’s task is not to fret. The numbers, while discouraging, shed light on where more work is necessary. More research on the contestation threshold is necessary in order to quantify it. It might not be a straight line. It might not be the same for the three steps. All this research intended was to demonstrate that it exists and is a useful tool for international lawyers, maybe just not applicable equally to every step of the life of a norm. Reasons for contestation also need to be investigated. These can be extremely variable, as contestation is “a way to voice difference of experience, expectation and opinion”[98], and change in time.

It also might seem that contestation has less and less impact as the norm becomes more and more hard law. Here lies the division between soft law and hard law, between international relations and international law. Of course, contestation will be more effective before the legal crystallisation of the norm, it is always easier to stop something from happening than trying to undo it. This is also why normativity cannot be compared between different steps. The contestation threshold is a useful tool when it comes to comparing two or more norms of the same scale, and only for comparison until the threshold itself is better defined.

As Wiener puts it,

as a social activity that involves discursive and critical engagement with norms of governance, whether voiced or voiceless, contestation is constitutive for social change, for it always involves a critical redress of the rules of the game […]. As a normative critique it involves an interest in either maintaining or changing the status quo whether through civil society actors’ claims-making, the rejection of compliance criteria in international negotiations, the refusal to implement norms on the ground, spontaneous contestation or debating alternative interpretations of norms.[99]

Contestation goes hand in hand with compliance. Compliance data will not make much sense until contestation becomes an integral part of the international legal discourse. While the arguments and approach of this piece is not news for international relations scholars, they hopefully provide a new way for international lawyers to think about their subject.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

The Cambridge Dictionary defines cynic as “a person who believes that people are only interested in themselves and are not sincere”: Cambridge Dictionary, sub verbo “cynic”, online: Cambridge Dictionary, <https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/cynic>.

-

[2]

For more on this subject, see Alexander Wendt, “The State as Person in International Theory” (2004) 30:2 Rev Intl Studies 289; Peter Lomas, “Anthropomorphism, Personification and Ethics: A Reply to Alexander Wendt” (2005) 31:2 Rev of Intl Studies 349; Robert Oprisko and Kristopher Kaliher, “The State as a Person?: Anthropomorphic Personification vs. Concrete Durational Being” (2014) 6:1 J Intl & Global Studies 30; Harlan Grant Cohen & Timothy Meyer, eds, International Law as Behavior, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

-

[3]

It is true that in international relations, taking a behaviouralist approach isn’t obligatory as the analysis could be made from a (1) traditional perspective which solely focuses on state/government behaviour on issues such as power, national interest, etc., a (2) scientific perspective that bases the analysis on data collection/explanation, (3) a behavioural and post-behavioural perspective, or a (4) systems perspective, that focuses on the organisation of the systems at different levels. We believe, as constructivism attributes intrinsic value to norms, it is closest to this behavioural approach, as corroborated by its foundations which are in psychology, philosophy of education and epistemology.

-

[4]

Even though we know that it does not; Julian Fernandez, Relations Internationales, (Paris: Dalloz, 2019) at 36.

-

[5]

Anne-Marie Slaughter, “International Relations, Principal Theories”, in Rüdiger Wolfrum, ed, The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013) at para 8.

-

[6]

Ibid at para 20.

-

[7]

See e.g. Elizabeth Stubbins Bates, “Sophisticated Constructivism in Human Rights Compliance Theory” (2014) 25:4 Eur J of Intl L 1169; Malte Brosig, “No Space for Constructivism? A Critical Appraisal of European Compliance Research” (2012) 13:4 Perspectives on European Politics and Society 390.

-

[8]

Carmela Lutmar & Cristiane L. Carneiro, “Compliance in International Relations”, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, (25 June 2018).

-

[9]

Ibid.

-

[10]

Ibid.

-

[11]

Antje Wiener, A Theory of Contestation (Heidelberg: Springer, 2014) at 4 [Wiener, A Theory of Contestation].

-

[12]

Marc Lynch, “IR: Constructivism v Rationalism” (25 July 2005), online (blog): Abu Aardvark <https://abuaardvark.typepad.com/abuaardvark/2005/07/ir_constructivi.html%20>.

-

[13]

Pierre Bourdieu, Practical Reason: On The Theory of Action (California: Stanford University Press, 1998) at 47: “Symbolic capital is any property (any form of capital whether physical, economic, cultural or social) when it is perceived by social agents endowed with categories of perception which cause them to know it and to recognize it, to give it value. […] More precisely, symbolic capital is the form taken by any species of capital whenever it is perceived through categories of perception that are the product of the embodiment of divisions or of oppositions inscribed in the structure of the distribution of this species of capital (strong/weak, large/small, rich/poor, cultured/uncultured).”

-

[14]

Wiener, A Theory of Contestation, supra note 11 at 4.

-

[15]

Ibid at 1: “Contestation is a social activity. While mostly expressed through language not all modes of contestation involve discourse expressis verbis. […] However, all modes of contestation exclude violent acts, which play a more central role in acts of dissidence. In turn, as a social practice contestation entails objection to specific issues that matter to people. In international relations contestation by and large involves the range of social practices, which discursively express disapproval of norms.).” (emphasis added).

-

[16]

Ibid at 1-2.

-

[17]

Ibid at 2.

-

[18]

Antje Wiener, Contestation and Constitution of Norms in Global International Relations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018) at 43 [Wiener, Contestation and Constitution of Norms].

-

[19]

Ibid at 44.

-

[20]

While populism has normalised human rights contestation, the emphasis is usually on a certain category of rights (rights of refugees and migrants, or LGBTI+ people), or it is not the nature of the right that is contested but the alleged origin, a suspected foreign intervention etc. Ultimately, even Viktor Orban, the Hungarian Prime Minister and maybe the pinnacle of European populists, speaks favourably about human rights: “Accordingly, the 2010 elections, and especially in the light of the 2014 election victory, can safely be interpreted as meaning that in the great global race that is underway to create the most competitive state, Hungary’s citizens are expecting Hungary’s leaders to find, formulate and forge a new method of Hungarian state organisation that, following the liberal state and the era of liberal democracy and while of course respecting the values of Christianity, freedom and human rights, can again make the Hungarian community competitive and which adheres to and completes the unfinished tasks and unperformed duties that I have just listed.” (emphasis added); website of the Hungarian Government, “Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Speech at the 25th Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp” (26 July 2014), online:<https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/en/the-prime-minister/the-prime-minister-s-speeches/prime-minister-viktor-orban-s-speech-at-the-25th-balvanyos-summer-free-university-and-student-camp>.

-

[21]

Wiener, A Theory of Contestation, supra note 11 at 36; Wiener, Contestation and Constitution of Norms, supra note 18 at 62.

-

[22]

Guy de Lacharrière, La politique juridique extérieure (Paris: Economica, 1983). Through this notion of ‘external legal policy’, which is the link between a state’s conduct and its interests, de Lacharrière explains his views on international law, which can be classified as realist in international relations terminology.

-

[23]

Asher Alkoby, “Theories of Compliance with International Law and the Challenge of Cultural Difference” (2008) 4:1 J Intl L & Intl Relations 151.

-

[24]

This last illustration is quite different from the others, as it is rather difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, an example is Venezuela’s refusal to appear before the ICJ in the dispute over the Essequibo region: Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, “Communiqué” (18 June 2018), online: <http://mppre.gob.ve/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CancilleriaVE-20180618-EN-ComuniqueLaHaya.pdf>; Alexander Wentker, “Venezuela’s Non-Participation Before the ICJ in the Dispute over the Essequibo Region” (2018) EJIL: Talk!, online: <https://www.ejiltalk.org/venezuelas-non-participation-before-the-icj-in-the-dispute-over-the-essequibo-region/>.

-

[25]

Anna-Luise Chané and Arjun Sharma, “Universal Human Rights? Exploring Contestation and Consensus in the Un Human Rights Council” (2016) 10:2 Human Rights & International Legal Discourse 219 [Chané & Arjun].

-

[26]

Legal scholars might see a resemblance with opinio juris here.

-

[27]

For examples, see: Cristina G. Badescu & Thomas G. Weiss, “Misrepresenting R2P and Advancing Norms: An Alternative Spiral?” (2010) 11:4 International Studies Perspectives 354-374; Mona Lena Krook, Jacqui True, “Rethinking the Life Cycles of International Norms: The United Nations and the Global Promotion of Gender Equality” (2012) 18:1 European Journal of International Relations 103-127; Antje Wiener, The Invisible Constitution of Politics: Contested Norms and International Encounters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

-

[28]

Nicole Deitelhoff & Lisbeth Zimmermann, “Things we lost in the fire: how different types of contestation affect the validity of international norms” (2013) 18 Peace Research Institute Frankfurt Working Papers < https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-455201>. Deitelhoff and Zimmermann have since published this working paper but the language of ‘threshold’ no longer appears in the article: Nicole Deitelhoff, Lisbeth Zimmermann, “Things We Lost in the Fire: How Different Types of Contestation Affect the Robustness of International Norms” (2020) 22:1 International Studies Review 51–76.

-

[29]

Christopher J Fariss, “Respect for Human Rights Has Improved Over Time: Modeling the Changing Standard of Accountability” (2014) 108:2 American Political Science Rev 297; Christopher J Fariss, “Are Things Really Getting Better? How To Validate Latent Variable Models of Human Rights” (2018) 48:1 British J Political Science 275. These findings are challenged, but simply for a question of method in David Cingranelli and Mikhail Filippov, “Are Human Rights Practices Improving?” (2018) 112:4 American Political Science Rev 1083. While Fariss’ method might not be optimal; the author deems that Cingranelli and Filippov’s has more fundamental flaws regarding methodology which are yet to be answered.

-

[30]

Charter of the United Nations, 26 June 1945, Can TS 1945 No 7, art 1.

-

[31]

Chané & Arjun, supra note 25 at 240.

-

[32]

Ibid at 238.

-

[33]

UN Website, “Functions and powers of the General Assembly”, online : <https://www.un.org/en/ga/about/background.shtml>.

-

[34]

Neil MacFarquhar, “In a First, Gay Rights Are Pressed at the U.N.”, The New York Times (18 December 2008), online: <https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/19/world/19nations.html>; UNGAOR, 63rd Sess, 70 th Mtg, UN Doc A/63/PV.70 (2008) at 30.

-

[35]

UNGAOR, 57th Sess, Extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, GA Res 57/214, UN Doc A/RES/57/214 (2003), para 6 (emphasis added).

-

[36]

UNGAOR, 69th Sess, Extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, GA Res 69/182, UN Doc A/RES/69/182 (2014), para 6 (emphasis added).

-

[37]

UNGAOR, 17th Sess, Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity, HRC Res 17/19, UN Doc A/HRC/RES/17/19 (2011).

-

[38]

UNGAOR, 19th Sess, Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights entitled “Discriminatory laws and practices and acts of violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity”, UN Doc A/HRC/19/41 (2011).

-

[39]

UNGAOR, 27th Sess, Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity, HRC Res 27/32, UN Doc A/HRC/RES/27/32 (2014).

-

[40]

UNGAOR, 32nd Sess, Protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, HRC Res 32/2, UN Doc A/HRC/RES/32/2 (2016).

-

[41]

UNGAOR, 41st Sess, Mandate of the Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, HRC Res 41/18, UN Doc A/HRC/RES/41/18 (2019).

-

[42]

UNGAOR, 65th Sess, Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to education, UN Doc A/65/162 (2010) at para 23, 67.

-

[43]

UNGAOR, 65th Sess, Summary record of the 29th meeting, UN Doc A/C.3/65/SR.29 (2010), at para 23 (emphasis added).

-

[44]

Ibid at para 9 (emphasis added).

-

[45]

Inter alia: The right to development, HRC Res 19/34, UNGAOR, 19th Sess, UN Doc A/HCR/RES/19/34 (2012); The right to development, Report of the Secretary-General and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNGAOR, 19th Sess, UN Doc A/HRC/19/45 (2011).

-

[46]

Declaration on the Right to Development, GA Res 41/128, UNGAOR, 41st Sess, UN Doc A/RES/41/128 (1986) [Declaration].

-

[47]

Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, UNGAOR, Conference on Environment and Development, UN DOC A/CONF.151/26 (1992).

-

[48]

Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, UNGAOR, World Conference on Human Rights, UN Doc A/CONF.157/23 (1993), art 10.

-

[49]

United Nations Millennium Declaration, GA Res 55/2, UNGAOR, 55th Sess, UN DOC A/RES/55/2 (2000) at para 11, 24..

-

[50]

Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development, UNGAOR, International Conference on Financing for Development, UN Doc A/CONF.198/11 (2002) at para 11.

-

[51]

2005 World Summit Outcome, GA Res 60/1, UNGAOR, 60th Sess, UN Doc A/RES/60/1 (2005) at para 123.

-

[52]

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, GA Res 61/295, UNGAOR, 61st Sess, UN Doc A/RES/61/295 (2007), art 23.

-

[53]

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Indigenous Peoples, United Nations Declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, online: <un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html#:~:text=The%20United%20Nations%20Declaration%20on,%2C%20Bangladesh%2C%20Bhutan%2C%20Burundi%2>.

-

[54]

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, GA Res 73/165, UNGAOR, 73rd Sess, UN Doc A/RES/73/165 (2018); United Nations, Digital Library, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas: resolution / adopted by the General Assembly, online: <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1656160?ln=en>

-

[55]

Arab Charter on Human Rights, League of Arab States, 22 May 2004 (entered into force 15 March 2008).

-

[56]

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Organization of African Unity, 27 June 1981, 1520 UNTS 217 (entered into force 21 October 1986) preamble, art 22(2).

-

[57]

Declaration on the Right to Development, supra note 46, art 1: “1. The right to development is an inalienable human right by virtue of which every human person and all peoples are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realized. 2. The human right to development also implies the full realization of the right of peoples to self-determination, which includes, subject to the relevant provisions of both International Covenants on Human Rights, the exercise of their inalienable right to full sovereignty over all their natural wealth and resources.”

-

[58]

Ibid, art 6.

-

[59]

Ibid, art 7.

-

[60]

For example, the right to self-determination (art. 1 of the Declaration on the Right to Development) is observable in the common article 1 of the two International Covenants on Human Rights; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 16 December 1966, 993 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 January 1976). Non-discrimination (art. 6 of the Declaration) is also in the both Covenants, respectively articles 26-27 and 2, and at article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Res 217A (III), UNGAOR, 3rd Sess, Supp No 13, UN Doc A/810 (1948) 71. Regarding disarmament (art. 7 of the Declaration), there are multiple treaties dedicated to the subject. For a more complete list of the principles contained in the Declaration that can be found in binding instruments: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Frequently Asked Questions on the Right to Development, Fact Sheet no. 37 (New York and Geneva: United Nations, 2016) at 5-7.

-

[61]

Eric Neumayer, “Do International Human Rights Treaties Improve Respect for Human Rights?” (2005) 49:6 J Confl Resolution 925 at 950-951. See also Oona A. Hathaway, “Do Human Rights Treaties Make a Difference?” (2002) 111:8 Yale LJ 1935.

-

[62]

Ryan Goodman & Derek Jinks, “Measuring the Effects of Human Rights Treaties” (2003) 14:1 Eur J Intl L 171 at 183.

-

[63]

International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, 18 December 1990, 2220 UNTS 3 (entered into force 1 July 2003) [CMW].

-

[64]

Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989, 1577 UNTS 3 (entered into force 2 September 1990) [CRC].

-

[65]

As of June 2020.

-

[66]

One is tempted to compare with another very widely ratified human rights treaty, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights for example; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976). The latter has reached the 35 ratifications necessary for its entry into force in 10 years, but it is not a just comparison as time periods and subjects and political contexts are very different.

-

[67]

The six states parties mentioned are the following: Montenegro (succession in 2006), Serbia (succession in 2001), Somalia (ratification in 2015), South Sudan (accession in 2015), Palestine (accession in 2014), and Timor-Leste (accession in 2003). All became independent rather recently.

-

[68]

Emilie M. Hafner-Burton, “Sticks and Stones: Naming and Shaming the Human Rights Enforcement Problem” (2008) 62:4 Intl Organization 689; Jacob Ausderan, “How naming and shaming affects human rights perceptions in the shamed country” (2014) 51:1 J Peace Research 81; James C. Franklin, “Human Rights Naming and Shaming: International and Domestic Processes” in H. Richard Friman, ed, The Politics of Leverage in International Relations: Name, Shame, and Sanction (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) 43.

-

[69]

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976) [ICCPR].

-

[70]

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 18 December 1979, 1249 UNTS 13 (entered into force 3 September 1981) [CEDAW].

-

[71]

Eric Neumayer, “Qualified Ratification: Explaining Reservations to International Human Rights Treaties” (2007) 36:2 The Journal of Legal Studies 397 at 421; Kelebogile Zvobgo, Wayne Sandholtz, & Suzie Mulesky, “Reserving Rights: Explaining Human Rights Treaty Reservations” (2020) 40:1 Intl Studies Quarterly 1. The number of state parties should ideally be taken into account while considering the number of reservations.

-

[72]

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, 20 December 2006, 2716 UNTS 3 (entered into force 23 December 2010).

-

[73]

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 10 December 1984, 1465 UNTS 85 (entered into force 26 June 1987) [CAT].

-

[74]

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 13 December 2006, 2515 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 May 2008).

-

[75]

Neumayer, supra note 71 at 421; Zvobgo, supra note 71.

-

[76]

Zvobgo, supra note 71.

-

[77]

Neumayer, supra note 71 at 421.

-

[78]

CEDAW, 2010, 16th Mtg, « Declarations, reservations, objections and notifications of withdrawal of reservations relating to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women », UN Doc CEDAW/SP/2010/2 at 50-52.

-

[79]

Ibid.

-

[80]

CEDAW, art 16.

-

[81]

Report on Indicators for Promoting and Monitoring the Implementation of Human Rights, 20th Mtg of chairpersons of the human rights treaty bodies, 7th inter-committee meeting of the human rights treaty bodies, UN Doc HRI/MC/2008/3 (2008); United Nations Statistics Division, in collaboration with the Friends of the Chair group on broader measures of progress, “Compendium of statistical notes for the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals”, March 2014, online: <https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/3647Compendium%20of%20statistical%20notes.pdf>.

-

[82]

“Il n’est pas si évident que cela que les décisions du Comité des DH, et dans une certaine mesure celles des autres organes de traité, ne sont pas obligatoires et qu’elles n’auraient qu’une portée morale, politique ou diplomatique”, Olivier Delas, Manon Thouvenot & Valérie Bergeron-Boutin, “Quelques considérations entourant la portée des décisions du Comité des droits de l’homme” (2017) 30:2 RQDI 1 at 49.

-

[83]

Geir Ulfstein, “The Human Rights Treaty Bodies and Legitimacy Challenges” in Nienke Grossman et al, eds, Legitimacy and International Courts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018) 284 at 293 [Ulfstein, 2018].

-

[84]

Geir Ulfstein, “Individual Complaints” in Helen Keller and Geir Ulfstein, eds, UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies: Law and Legitimacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012) 73 at 92 [Ulfstein, 2012].

-

[85]

Ulfstein, 2018, supra note 83 at 302.

-

[86]

Ahmadou Sadio Diallo (Republic of Guinea v. Democratic Republic of the Congo), [2010] ICJ Rep 2010 639 at 664.

-

[87]

General Comment No. 33 Obligations of States parties under the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, CCPR General Comment, UNGAOR, 94th Sess, UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/33 (2009) para 11.

-

[88]

Lutz Oette, “The UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies: Impact and Future”, in Gerd Oberleitner, ed, International Human Rights Institutions, Tribunals, and Courts (Singapore: Springer, 2018) 1 at 11.

-

[89]

Ulfstein, 2012, supra note 84 at 93.

-

[90]

Out of the remaining 4, the committee on CMW is not yet in force and the committee on CED had only received one individual complaint, whose outcome was a violation.

-

[91]

The numbers are mostly inconsistant. According to the statistical survey from March 2016, there were 1155 views adopted by the Human Rights Committee at the time(contestation rate of 84%), and according to the jurisprudence database there are 1177 in total, but there are 157 views that are dated after March 2016 in the database: Human Rights Committee Website, “Statistical Survey on Individual Complaints”, online: <https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CCPR/StatisticalSurvey.xls>. The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination had a 50% contestation rate with 30 adopted views according to the statistical survey from May 2014. There are 44 cases total in the jurisprudence database but only 4 are after May (3 violations and one non-violation): Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, “Statistical Survey on Individual Complaints”, online: <https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CERD/StatisticalSurvey.xls>. Finally, and to a lesser extent, the CRPD Committee had 5 views adopted by May 2014 according to the statistical survey (100% contestation rate) but there are 21 cases total in the jurisprudence database with only 15 after May 2014: Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Website, “Statistical Survey on Individual Complaints”, online: <https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CRPD/StatisticalSurvey.xls>.

-

[92]

Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Website, “Statistical Survey on Individual Complaints”, online: <https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CEDAW/StatisticalSurvey.xls>.

-

[93]

All numbers available on 2 June 2020.

-

[94]

Committee against Torture Website, “Statistical Survey on Individual Complaints”, online: <https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/cat/pages/catindex.aspx >.

-

[95]

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 16 December 1966, 993 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 January 1976).

-

[96]

Oette, supra note 8886 at 11.

-

[97]

Ulfstein, 2012, supra note 84 at 75.

-

[98]

Wiener, A Theory of Contestation, supra note 11 at 11.

-

[99]

Ibid at 2.

List of tables

Table 1

Table 2

The contestation threshold

Table 3

Step 1 case studies