Abstracts

Abstract

The gradual introduction of Translation Memory in translation workplaces, starting in the late 1990s, has created a classic industrial conflict. Managers and clients of translation services want to increase productivity, but translators do not want to be told how to produce translations, and they do not want to see their incomes reduced. While the technical features of Memory programs certainly cause dissatisfaction, all technologies have defects, and a key question then is who decides how to deal with these defects—translators? or managers and clients? As a result, policies on the use of Memory in a workplace become crucial. There are objective policy questions: Are translators’ productivity requirements increased when Memory is introduced? Do translators receive less pay for matches found in the Memory database? Is the translator allowed to search the Memory database? Then there is the subjective aspect: how do translators feel about their own experience of whatever is objectively happening? Do they feel they are in control of the texts they are producing? Are technologies increasing or decreasing their satisfaction with their working lives? Do they have a sense of losing the ability to compose their own translations or are they equally happy to revise wordings proposed by Memory? Do they feel that use of these technologies is reducing or enhancing the status of translators in society? This article looks at some of these subjective matters, based on two surveys of Ontario translators conducted in 2011 and 2017.

Keywords:

- Translation Memory,

- policies,

- attitudes,

- survey,

- conflict,

- emotion

Résumé

L’introduction progressive des mémoires de traduction dans les milieux de travail à partir de la fin des années 1990 a donné lieu à un conflit industriel classique. Les responsables des agences de traduction de même que leurs clients veulent augmenter la productivité des traducteurs, mais les traducteurs ne veulent pas qu’on leur prescrive une façon de traduire et ils ne veulent pas voir leurs revenus réduits. Bien que les caractéristiques techniques des mémoires soient la cause d’une certaine insatisfaction parmi les traducteurs, il reste que toutes les technologies ont des défauts, et une question clé est alors de savoir qui décidera comment agir en face de ces défauts : les traducteurs ou leurs employeurs? En conséquence, les politiques relatives à l’utilisation de la mémoire deviennent une variable cruciale. Il y a des questions objectives concernant ces politiques : les exigences de productivité des traducteurs sont-elles augmentées lorsque la mémoire est introduite? Les traducteurs reçoivent-ils des paiements moindres pour les correspondances trouvées dans les mémoires? Les traducteurs ont-ils la possibilité d’interroger la base de données de la mémoire? À cela s’ajoute l’aspect subjectif : comment les traducteurs ressentent-ils ce qui se passe objectivement? Sentent-ils qu’ils gardent le contrôle des textes qu’ils produisent? Les technologies augmentent-elles ou diminuent-elles leur satisfaction vis-à-vis de leur vie professionnelle? Ont-ils le sentiment de perdre la capacité de composer leurs propres traductions? Pensent-ils que l’utilisation de ces technologies réduit ou améliore le statut social des traducteurs? Dans la présente étude, certains de ces aspects subjectifs sont examinés à la lumière de deux sondages menés auprès des traducteurs de l’Ontario en 2011 et en 2017.

Mots-clés :

- mémoire de traduction,

- politiques,

- attitudes,

- sondage,

- conflit,

- émotions

Article body

I believe that in my lifetime automated translation will replace translators and translation as we know them today. Translators’ incomes will drop dramatically as we become revisers, and translation work will be concentrated in the hands of a few large, primarily non-Canadian agencies that have the resources to invest in expensive technology and networks. I believe the Canadian industry will be bought out by multinational interests (i.e., TM software firms) unless it has legislative protection. Ironically, the big money is in automated translation equipment and software, not translation itself. I therefore view TMs as a major change that will constitute “progress” for many and the demise of the profession for some.

Comment on a 2011 survey of Ontario translators about Translation Memory

Conflict and Policy

Translation Memory (TM) is most commonly discussed (among translation managers and clients) in terms of productivity enhancement or else (among translators) in terms of user-friendliness. It is often seen as a Good Thing, at least in principle. But Good for whom? Who is benefiting from the way it is being used in a workplace? To assess the pluses and minuses of Memory, we should look not mainly at the user-friendliness of this or that system but rather at how an employer’s, agency’s or client’s technology policy is being implemented. Policy implementation is what determines whose interests are served—and whose are not. (Written policies themselves are not so important, since they may be ignored in practice.)

The gradual introduction of Memory, starting in the late 1990s, seems to have created a classic industrial conflict in many workplaces. Judging from my own experience[1], managers of translation services and their clients want to increase productivity. Translators for their part, while happy to have a way of dealing with repetitive text, do not want to be rushed or told how to use Memory to produce translations (for fear that quality will suffer), and they do not want to see their incomes reduced (as a result of non-payment for translations recycled from Memory). These often conflicting interests continue to create some degree of dissatisfaction among many translators.

Situations of conflict have both an objective and a subjective aspect. There are objective questions about how Memory is introduced: Are translators’ productivity requirements increased? Do they receive less pay for matches found in the Memory database? Are there penalties for failing to use 100% matches without revision? Then there is the subjective aspect: How do translators feel about their own experience of whatever is objectively happening? Do they feel that they are in control of the texts they are producing or that someone else is? Are technologies increasing or decreasing their satisfaction with their working lives? Do they have a sense of losing the ability to compose their own translations or are they equally happy to revise wordings proposed by Memory? Do they feel that use of such technologies is reducing or enhancing the social status of translators?

In this article, I look at some of these subjective matters, based on two surveys of Ontario translators I conducted in 2011 and 2017.

Previous Studies

The literature on Translation Memory and its near relative Machine Translation is mostly found in technology journals, and it is focused on software engineering matters and on machine output quality as understood by computational linguists and the localization industry. Still, there are now within Translation Studies a good number of articles about these technologies and more particularly about human/machine interaction. However the subjective aspect—the feeling of motivation, control or professional satisfaction—is often not discussed at all, mentioned only in passing (Bundgaard, 2017, briefly mentions translators saying they feel “trapped” by machine translation outputs), or considered in a very abstract way (Taravella and Villeneuve, 2013).

The methods with most potential to cast light on the subjective aspect are interviews with translators, surveys of translators that include open questions, analysis of comments at online translator forums, posts on social media and articles in professional publications such as ATA Chronicle and Circuit (see for example Bédard, 2014). Among the studies based on these sources, some are not concerned at all with the subjective matters of interest here, and very few are concerned mainly with these matters. Even when translators’ expressed attitudes are considered, authors may simply summarize what the translators said or wrote rather than providing first-person quotations, with the result that subjectivity cannot be discerned. While other studies do provide quotations, it should be noted that, leaving aside the work of poets, writing is limited in its ability to express subjectivity. With writing, it is much easier to report feelings than to express them, because (even with emojis!) there is no real counterpart to pitch and loudness variation, tone of voice, facial expressions, bodily stance and manual gestures. Thus quoted statements from interviews may or may not have been uttered in a voice charged with feeling. The distinction is an important one when considering situations of conflict: rational criticism that is not backed up by fairly strong feeling is unlikely to lead the critic to take any action.

Ignacio Garcia (2003) looks at translators’ posts about Memory at an online translators’ forum, but provides quotes only from discussions about which software maker’s system works best and about the cost of buying a system. (An underlying assumption behind many studies seems to be that the main or only problem with systems is that they are hard to use and expensive.) Garcia (2006) looks at posts at the same forum and quotes expressions of both positive and negative feelings. Some of the negative feelings are again about technical usability, notably the steep learning curve. More interestingly, there are positive feelings about increased productivity once the system has been mastered, especially though not only with repetitive texts, but these positive feelings are often short-lived because of “discounts”: freelance translators are often paid less for passages found in Memory—a policy matter.

Cheryl McBride (2009) similarly examines discussions of Memory at online translator forums, and provides quotations, but once again, most of the discussion concerns technical aspects of Memory programs, and the cost of purchasing them, rather than policies on how they are used. The issue of discounted prices for matches is considered, but only briefly.

Patrick Cadwell et al. (2016), in focus groups with European Commission translators, elicited reasons for using or not using Machine Translation but provides no quotations. Guerberof (2013), in an interview study about MT post-editing, does give multiple quotations reflecting translators’ negative and positive experiences.

Samuel Läubli and David Orrego-Carmona (2017) performed sentiment analysis on some 13,000 tweets by translators about Machine Translation. All the tweets were analysed by an automated method while 150 were also analysed by two independent judges. Overall, negative tweets outnumbered positive ones 3:1. However, the judges did not agree on a third of the cases, and the automated system similarly failed to reproduce human judgments a third of the time. Also, looking at the examples the authors give, one can see a methodological problem that will affect any study of attitudes: how to distinguish, within expressions of “sentiment,” between thoughts and feelings. For example, one tweet reads “six reasons why machine translation can never replace good human translation.” While this was quite justifiably judged to be negative both by judges and by the automated system, my first inclination was to see this tweet as largely an expression of analytical thought (“six reasons”), with perhaps a modicum of emotion involved (“can NEVer”), but someone else could easily arrive at a different judgment. If the words were spoken rather than written, it would be much easier to decide. With writing, it is not only more difficult for a writer to express feelings; it is also harder for a reader to discern whether feelings are in fact being expressed.

Elizabeth Marshman (2012, 2014) deals entirely with feelings of control over translation technology, but technology in general rather than Memory or Machine Translation in particular. Her studies are based on 200 responses to an online survey. The survey included open questions, but there are no quotations from the answers. Marshman found that, of those respondents who perceived the introduction of technologies as having an effect on control over their work, 77% felt more in control of the amount of work they were given (23% felt less in control); 74% more in control of quality; 67% more in control of the tasks they were given; 61% more in control of their methods; 53% more in control of their relations with clients and employers, and 46% more in control of their remuneration (2014, p. 391)—an overall positive but still very mixed picture. Among these various kinds of control, control over quality was rated most important by respondents. Regarding the role of policy, Marshman states that

the factors most linked to the loss of control among experienced freelance translators appear to be related not to the inevitable effects of technology use (the need to learn to use tools and to manage resources, to adapt working methods and workflows) or to the amount or quality of work done, but rather to human factors and policies in tools’ implementation. Although client relations can be strengthened by factors such as better communication, and tools help to increase productivity, the imposition of specific tools and discount schemes, along with the obligation to re-use solutions from resources, lead many respondents to feel they are less in control of their work. A number of respondents noted that they now choose or refuse clients in part based on such policies.”

2012, p. 10; my emphasis

This is similar to the view I set out in 2011 in my oral presentation of the results of my first survey[2], except that I did not mention what I now see as the key concept “policy.” During that presentation, I said that how Memory is used is not just a technical matter of how the program works. It also depends in part on the balance of power between translators and those who pay them. At one extreme, translators may own the Memory program and a database of their own translations. They then control the pace of work and method of production. At the other extreme, translators are required to use a Memory loaded with other people’s translations. They may be paid less or not at all for segments that are found in the Memory database.

Kaisa Koskinen and Minna Ruokonen (2017) asked their subjects (professional translators in Finland and at the European Commission in Brussels, as well as MA students in Finland and Ireland) to write love letters or break-up letters to some aspect of their working environment. Most respondents mentioned a technology, whether hardware (screen, mouse) or software (term base, Memory or a search tool) (“Dear Internet…”). Of the letters written by professional translators that mentioned technologies, 43 were love letters, 25 were break-up letters and 4 were ambivalent. However, among the 43 love letters, the largest group were addressed to search engines and databases (22 letters) as compared to just 10 love letters addressed to Memory. Among the EU translators, SDL Trados Studio, the Memory program they all use, was mentioned in 4 love letters and 6 break-up letters[3].

The same two authors (Ruokonen and Koskinen, 2017) analyse the wording of the letters in terms of the perceived relationship of human and machine: were they seen to be cooperating or pulling in different directions? did this relationship elicit positive or negative feelings? and did the translator feel that he/she was dominant or that the machine was dominant? The machine was felt to have some degree of agency in slightly over half the 106 technology-related letters. In the 20 positive letters where human and machine were felt to be cooperating, the human agent was seen as dominant in 12, human and machine equal in 6 and the machine dominant in 2. In the 32 negative letters where human and machine were felt to be working at cross purposes, the machine was seen as dominant in 24, machine and human equal in 6 and the human dominant in 2. No separate figures are given for Memory, and the question of policy does not arise (in either article) because the methodology focuses the letter writer’s attention on individual experience rather than on workplace factors.

Three studies by Matthieu LeBlanc (2013, 2014 and 2017) deal specifically with Memory. They are based on observation of 20 translators at work and interviews with 51 translators and revisers, at three Canadian workplaces. The first study focuses on the advantages and disadvantages of working with Memory, the second on the translator’s relationship to the text as mediated through Memory (the fact that texts are presented on-screen segment by segment), and the third on professional satisfaction in relation to productivity requirements and enforced recycling of translations found by the Memory. The second and third studies contain several fairly lengthy quotations from the interviews.

LeBlanc found a decline in satisfaction at two of the three workplaces he visited—the two that enforced recycling of 100% matches without revision. Like Marshman, he suggests that

what seems to have unsettled translators the most is not so much the tool’s inherent design (e.g., the fact that some TMs encourage text segmentation), but more so the shifts in administrative and business practices that have, in some cases, accompanied TM implementation

LeBlanc, 2017, p. 45

Finally, there are a few studies carried out within the framework of ergonomics, broadly understood as the study of human beings at work, and thus including not just the physical setup of the workstation but also the cognitive and organizational aspects of work. These studies do not contain quotations but do consider the question of translators’ loss of control. Daniel Toudic and Guillaume de Brébisson state that with the arrival of Memory in the workplace, “le traducteur passe progressivement du statut de prescripteur et d’acteur à celui d’opérateur travaillant dans un cadre et avec des outils et des méthodes qu’il n’a pas choisis” (2011, p. 4). Maureen Ehrensberger-Dow and Sharon O’Brien mention the “sense of personal control or agency over the situation and activity, which we argue might be reduced or even removed through the use of common translation tools in the highly technologized workplace” (2015, p. 102). They point to the “cognitive friction” that arises when workplaces do not follow good ergonomic practices, but they skirt around the question of conflicting interests that may prevent the reduction of such friction.

The Surveys

In 2011, and again in 2017, I sent a survey to translators certified under Ontario provincial legislation to translate from French to English[4]. Some questions were worded differently in 2017, but the questions considered here had the same wording both times. The 2017 survey (which included questions about Machine Translation) can be seen in the Appendix. As will be evident, the survey opens the way for responses covering a wide range of factors that may correlate with attitudes to Memory. In this article, however, the focus will be on how attitudes may be affected by the policies of employers and clients, and on wordings in responses that seem to express emotion (insofar as this can be determined through the written language).

In 2011, I received 40 surveys (32% of 126 surveys sent out); 24 of the respondents (60%) told me that they had never used Memory. In 2017, I received 39 surveys (23% of 168 sent out); 17 of the respondents (44%) had never used Memory and 29 (74%) had never used MT. Thus whereas in 2011, fewer than half the respondents (40%) had used Memory, by 2017, more than half (56%) had used it. If we leave aside the possibility that use versus non-use among respondents to the survey does not reflect use versus non-use among non-respondents, this change over time suggests that Memory is spreading, though uptake does seem to be rather slow, considering that this technology had been commercially available for 20 years at the time of the second survey.

Of the twenty respondents who reported the number of years they had been using Memory on the 2017 survey, both the average length and the median length was 10 years, with a range from 2 to 16 years. All but seven respondents had used Memory for 10 years or more.

While I will be giving a few numerical results from the surveys, I do want to emphasize that this is not a quantitative study. In view of the small number of respondents, and the limitation to the minority of translators who are certified in and work in one particular language pair and direction, the figures may well not be representative of the translation industry in Ontario or in Canada, not to mention the rest of the world. In addition, the wording and ordering of questions on surveys can have a significant effect on the answers (for example, different respondents may interpret a given wording differently); I have no expertise in such matters.

Finally, I should point out that the questions on the two surveys were addressed solely to translators who indicated in an initial question that they had actually used Memory or MT. Unlike Sandra Dillon and Janet Fraser (2006), I did not ask non-users about their “perceptions” of Memory (with a view to determining why they did not use this technology) or about matters such as being rejected for a job because they did not own the Memory program required by the agency or client.

Some Results from the Closed Questions

In 2011, I used a combination of closed and open questions. I may have thought at the time that responses to the former would help interpret responses to the latter, which were my principal concern. In 2017, I did not consider the relationship between the two types of questions because I had decided to achieve comparability by asking the same questions. Here I will look at only two of the closed questions, and then turn to the comments on some of the open questions.

Table 1 shows the results of a question about respondents’ general attitude toward Memory[5]. As can be seen, there is apparently no change from 2011 to 2017: half liked Memory, while the other half either hated it or had mixed feelings.[6] If this range of attitudes is common among users of Memory, then it seems that while things are not getting worse, they are not getting any better either.

Table 1

Answers to Survey Question 12

Now, there are a very large number of factors that could lie behind these results. The following list (which includes factors not mentioned in the survey questions or responses) is almost certainly not exhaustive.

Translator is required to use Memory vs not required to use it

Translator is salaried vs agency contractor vs independent (has direct clients)

Which Memory system/version is used (affects ease of use and cost)

On-screen environment: CAT environment specific to a Memory system vs MS Word with Memory as an add-on

Other aspects of the computer environment: access to IT support; size and number of screens on the translator’s desk

Memory program is on the translator’s computer vs accessed over the web

Source text is pre-processed through Memory vs handled interactively (with pre-processing, the translator sees one automatically selected translation from among the matches; with interactive processing, the translator may see several matches and can accept or reject each of them; this becomes a policy matter when clients and agency managers do not give the translator access to their Memories, but simply provide pre-selected translations of matches)

Whether the translator can search the Memory’s database (use it as a bilingual concordancer)

Whether and how easily the translator can see the context of the current segment with formatting

Reduced credit[7] for 100% and substantial fuzzy matches vs full credit for all words

Frequency of short deadlines (increases the need to use wordings found by Memory, whatever their quality)

Memory seems to slow down vs speed up production

Type of text translated (well written? how specialized? how much repetition of wordings?)

Language pair and direction in which the translator is working

Matches are found for only a small proportion of a typical text vs a large proportion

Quality of translations in the Memory’s database

Frequency of work with Memory (all day every day? a few hours once or twice a week?)

Years of experience with Memory (how present experience compares with past experience)

Years as a translator (do they remember working without Memory or even without computers?)

Gender of the translator

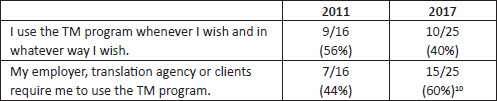

It is not the purpose of this article to investigate correlations between all the factors available from the surveys and attitudes toward Memory[8]. I will simply look at the correlation between Table 1 and Table 2, which shows the responses to a question about whether it was the policy of the translator’s employer, agency or clients to require the use of Memory—the first factor on the above list[9]. As can be seen, a much higher proportion were required to use Memory in 2017: 60% as compared to 44% in 2011. To put it the other way round, a much lower proportion were objectively in control of their use of Memory in 2017: just 40% as compared to 56% back in 2011.

Table 2

Answers to Survey Question 9[10]

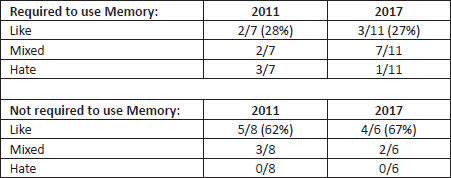

Table 3 shows the correlation between the requirement to use Memory and respondents’ feelings about it. Feelings do seem to be strongly correlated, in both surveys, with the presence versus absence of a requirement to use Memory. Less than 30% of those required to use it liked it, whereas over 60% of those not required to use it liked it. Among those not required to use Memory, no one hated it.

Table 3

Question 12 vs Question 9[11]

Since only 10 of the 2017 respondents had used Machine Translation, and there were hardly any open-question comments about it, I shall mention but not discuss the results. Just 2 out of 10 said they liked MT, and neither of them were required to use it; 5 had mixed feelings (4 of whom were required to use it), and 3 hated MT (2 required to use it). Christensen and Schjoldager (2016) report that while Memory is very widely used in Danish translation companies, MT is not—a situation which I suspect is still common.

Some Quotes from the Open Questions

Tables 4 and 5 (see pp. 324 and 325) show some[12] of the wordings expressing negative attitudes toward Translation Memory (TM on the tables), in 2011 and 2017 respectively. These attitudes are not correlated with the general attitudes reported on Table 1: even respondents who “on the whole” liked Memory nevertheless expressed some negativity. Since the emphasis in this article is on subjective matters, vocabulary that may be expressing emotion is bolded. Bear in mind, however, the previously mentioned limitation on the expression of emotion through writing.

The comments appear under three headings: technical disadvantages, economic disadvantages and professional/personal dissatisfaction. Unfortunately, the survey questions did not clearly elicit a distinction between negative feelings arising from technical and financial matters (steep learning curve; cost of Memory) and negative feelings arising from policy matters (discounts; forced recycling of matches). That is because the concept of “policy implementation” had not yet occurred to me when I prepared the surveys. Reactions to policy are seen mainly in the third column (professional/personal dissatisfaction). Some comments could be placed in more than one column. For example, the last item in the “technical problems” column on both tables (nicely expressed by one respondent as “compromises ‘textness’,” i.e., inability to see context) could also be considered an expression of professional dissatisfaction.

I have not counted the number of mentions of wordings expressing a particular source of satisfaction or dissatisfaction since I do not believe that mere frequency is informative. (I am also skeptical of the whole idea of quantifying expressions of feeling. Using precise numbers in this context would create a false sense of objectivity/ scientificity.) The importance of a given source of (dis)satisfaction can only be judged in the light of some theory. As mentioned at the outset, my theory is that translators’ sense of control over Memory, arising from the way technology policies are implemented, is the key to explaining (dis)satisfaction. If hardly anyone had mentioned matters related to control, and almost everyone had mentioned the shortcomings of the software, then the theory would be highly problematic, but that is not the case. All technologies have technical defects[13]; the question is who decides what to do about them (in this case: do translators or employers/clients decide?).

In this article, I clearly cannot confirm or disconfirm my theory about the sense of control as the main factor explaining attitudes toward Memory. That would require ruling out a long list of other possible factors as the main explanation, and my small surveys do not make that possible. In addition, while objective control is easily ascertained (see Table 2), the feeling of control cannot be fully revealed in written answers to survey questions. A fuller exploration would require interviews, or experiments, conducted with the assistance of a psychologist specialized in the study of emotion.

Table 4

Expressions of negative attitudes to Memory 2011

Table 5

Expressions of negative attitudes to Memory 2017

Tables 6 and 7 show wordings expressing positive attitudes toward Memory, in 2011 and 2017 respectively. While I have not made a lexical analysis, there seems to be less emotive vocabulary in these comments.

Both the positive and the negative comments are self-explanatory. What is of interest is the fact that the same factors leading to satisfaction or dissatisfaction were mentioned in both 2011 and 2017, and indeed have been mentioned in other writings over the past 15 years or so. This is hardly surprising, because despite a few improvements in the user interfaces of the various Translation Memory systems, the basic design concept is unchanged. The similarity of comments may also suggest that there has been no general shift in employers’ and clients’ policies over time.

Table 6

Expressions of positive attitudes to Memory 2011

Table 7

Expressions of positive attitudes to Memory 2017

“Good but…” Comments

Three of the comments on Table 7 end with a series of dots because the sentences continue in an interesting way, one that I found in a large number of comments in response to various survey questions. Here is a selection:

They’re an excellent source of terminology and client-approved phrases, assuming that the TM is maintained appropriately and not filled with junk.

Saves an enormous amount of time, as long as bitexts are aligned well.

It’s a tool that seems to be aimed at helping translators work faster on larger or group projects and to ensure consistency. Good, but it’s also become a tool to justify reducing the cost of a project. [a reference to less pay for fuzzy matches]

When there are a significant number of 100% matches TM is very good and a pleasure to work with, especially on team projects. [but] Below 90-95%, these tools are time-consuming and pointless. This can be very hard to explain to a non-translator, who sees a highlighted segment as nothing more than a “pass GO and collect $200” card.

It’s good for boiler plate translations, but where you need to be somewhat creative, it restricts you.

I embrace change and am willing to learn to adapt how I translate and revise to incorporate these tools. However, I only do so because I have seen now when/how it is useful. When it is not useful, I argue strongly against it.

I was happy to have TM…when I had a very large legal contract with a lot of repetition. In that case, it saved me hours of time. However, all memory input was mine, so I knew when and where it was reliable.

I found it helpful for consistency among a group of translators (when I worked on a major project as a salaried translator) but it was a real pain when working freelance.

The large number of these “good but…” comments—ones that combine a reason for liking immediately followed by a reason for disliking—suggests that there may be more mixed feelings than is apparent from the answers to the question about general attitudes (Table 1). Indeed, the first two comments in the above list were made by respondents who stated that on the whole they liked Memory. I did not receive any comments that had the opposite form: “bad but…” It is interesting that the thought of some positive aspect so often immediately elicited a contrasting negative, but the thought of a negative aspect did not elicit a contrasting positive.

Changes from 2011 to 2017

While the sources of (dis)satisfaction remained the same between 2011 and 2017, there were nevertheless a few interesting answers to a question on the 2017 survey about changes over the years. The question was addressed to those respondents who had worked with Memory both before and after 2011. I have bolded significant wordings.

I don’t like the “tunnel vision” effect of sentence-by-sentence translation. However, I’ve learned to live with it by using 2 screens to be able to refer to the entire source text if need be.

I hated it (the previous software at former company and SDLX at my current employer) for years and found it difficult to work with and useless. However, after years of using it and switching to Studio 2015 (GroupShare and MultiTerm as well), I am able to sort out which projects are great for using TMs and which are best done outside of machine translation software and can negotiate that. I’ve also been able to adapt how I translate to continue to deliver idiomatic texts despite the initial file being segmented, which to me is the hardest part.

The newer versions of the software are considerably more user friendly and less cumbersome. They interfere much less with the translation process and actually help with consistency and speed.

In the beginning I liked the novelty and the promise of TM. I was also part of a team working on repetitive material and it was very useful for ensuring consistency. However, it could also multiply errors to the point of being useless if not downright unproductive. Often the suggested translation is meaningless in the context. I find I do the same amount of work but I’m paid less because someone somewhere has decided a 50% match should take me less time to fix than simply translating what’s in front of me.

Of particular note are the first two comments: these translators “adapted” to Memory or “learned to live with it” over time. I would interpret these comments as “making the best of a bad situation”: a not-great technology has been imposed on me, so let me see if I can accommodate myself to it. By the way, these two comments are not examples of “bad but…” sequences because they concern changes over time.

Future Studies

While the proportion of overall likes and dislikes was unchanged from 2011 to 2017, what about changes related to each of the different aspects of Memory: the technical, the economic and personal/professional satisfaction? There do seem to be fewer technical complaints, but is this because of improvements in the user interface or because people had gotten used to the drawbacks, figured out ways to adapt or simply resigned themselves? My surveys do not reveal the answer. Nor do they reveal changes over time with respect to the economics of Memory: are more or fewer people complaining about reduced pay for 100% matches? Finally, what about changes over time in personal/professional (dis)satisfaction: are more or fewer people saying that Memory reduces drudgery? And how does the proportion of (dis)satisfaction with the technical and economic aspects compare to the proportion of personal/professional (dis)satisfaction? These are questions that cannot be answered by a small-scale study. Of particular interest in relation to this article would be changes over time related to policy matters, i.e., policy on “discounts” for matches, on requirements to use Memory with all texts, and on requirements to use matches (with or without changes).

Attempts should be made to pinpoint the combination of factors that correlates most strongly with liking/disliking Memory. Possible factors might include a selection from the lengthy list given under Table 1. Or one could seek to determine which class of factors is most important (using either my classification into technical, economic and personal/professional satisfaction or some other classification).

Methodologically speaking, in order to discern expressions of feeling, interview studies should be preferred over analyses of written comments. This would also be more revealing than asking people to reply “yes” or “no” to a series of written statements such as “I have more income than in the past due to more frequent useable matches” or “The technical difficulties of using Memory are annoying me more than in the past.”

Here are some hypotheses that might be tested in future studies:

Translators are adapting to Memory despite its drawbacks.

Translators are reacting to the negative features of Memory by resignation rather than anger.

Attitudes toward Memory depend mainly on whether the interface is becoming more user-friendly.

Attitudes depend mainly on rising or falling net incomes: Are the extra costs associated with Memory (price of the program for self-employed translators plus any “discounts” for matches) eventually offset by increased productivity, i.e., once the system has a big enough database to ensure a good number of matches?

Attitudes depend mainly on feelings of control.

Attitudes depend to a great extent on the age of the translator.

Attitudes depend mainly on the concept of acceptable quality held by managers and implemented in policy.

Concluding Thoughts

Many studies of Memory do point to its relatively high degree of acceptance. However, unlike electronic term bases, word-processing programs and web browsers, which were immediately welcomed by almost all translators, Memory technology is still a cause of fairly widespread dissatisfaction 20 years after it became commercially available. One has to wonder whether changes are possible that would alleviate this ongoing problem. Would a better interface design help? I doubt that today’s dissatisfied translators can be enticed, through some engineering solution, to think positively about a situation in which someone else dictates how technology will be used. I also doubt that translation managers will help, because their principal duty is to increase productivity, despite rhetoric about the importance of happy workers[14].

Translators’ concerns about quality will, I think, be answered by simply redefining acceptable quality to reflect what is possible when Memory or MT is used. The widespread notion that these technologies speed up translation and improve quality[15] may thus prove to be a self-fulfilling prophecy: obviously production can speed up if quality standards are changed to accommodate technological limitations. A translator may think that a sequence of matches from Memory makes for rather poor writing (bad inter-sentence connections, too many short sentences in a row) but that will be deemed irrelevant because improving the writing quality would take too long. As Mogensen put it when Memory was relatively new: “language is now being changed to fit the tools, instead of the other way round” (2000, p. 29). This state of affairs will simply become the new normal.

The only way to create a more positive attitude toward Memory and MT, I suspect, is to recruit a different type of person to translation, an “editor” rather than a “writer”—someone who takes satisfaction in editing machine outputs and, provided the user interface is fairly friendly, does not care much about feeling in control of technology, and does not expect a fairly high income. In this scenario, the profession of translation as it has existed since the 1950s simply vanishes.

Appendices

Appendix

The 2017 Survey Questions

Attitudes to Translation Memory and Machine Translation

If you do not have time to answer all the questions, please answer questions 1, 12, 14, 15 or 16, 18, 20, 21, and 22 or 23.

Feel free to add any comments to clarify your answers, right after any question.

Preliminary question. Please place an X beside the answer that applies to you.

___ My answers to the following questions about Translation Memory and Machine Translation pertain entirely or almost entirely to French-to-English translation.

___ My answers pertain in part to French-to-English translation and in part to the following language pairs/directions: ______________________________

___ My answers pertain entirely or almost entirely to the following language pairs / directions other than French-to-English: _____________________________

Note: The first five questions contain the expression “work with Translation Memory.” This covers three situations: the Memory program is installed on your computer; you access Memory over a network; you are given texts (by your employer, agency or client) that have already been processed through Memory ( target-language material has already been inserted in the texts you receive for translation)

1. Choose one:

___ I have never or almost never worked with Translation Memory (TM).

___ I have worked with Translation Memory sometimes or frequently for ___ years.

If you have never worked with TM, skip to question 18.

If you stopped working with TM before 2010 and have never started using it again since 2010, skip to question 18.

If you stopped working with TM some time between 2010 and the present, interpret the remaining questions as referring to the time after 2010 when you did work with it.

2. During the time when I have worked with TM, I was:

__ a salaried translator

__ an independent translator working directly for clients

__ an independent translator working for an agency

(Place an X beside all that apply.)

3. I have worked with the following TM programs:

_____________________________________________________

4. I have worked with TM when translating in the following principal fields (e.g. financial, medical, legal):

_____________________________________________________

5. Place an X beside all that apply:

-

__ I work in a TM screen environment or a combined TM/Machine Translation environment (e.g. Trados screen).

__ almost every working day

__ frequently

__ occasionally

-

__ I work in a Word (or other word processing) environment, accessing TM/Machine Translation separately when I need it.

__ almost every working day

__ frequently

__ occasionally

-

__ I work in a Word (or other word processing) environment that has TM/Machine Translation as an add-on.

__ almost every working day

__ frequently

__ occasionally

If your answer to question 5 represents a significant change from an earlier period, how have things changed? For example: I used to work in a TM environment occasionally; now I work in one every day. I used to work in a Word environment; now I work in a TM environment.

6. Place an X beside all that apply:

__ I have a TM program (or a combined TM/Machine Translation program) installed on my computer.

__ I access a TM program over a network.

__ I receive texts (from my employer, agency or clients) which have already been processed through TM before they come to me for translation.

7. If you receive texts from employers or clients in which source-language material has already been replaced by target-language material automatically generated by a TM program, place an X beside all the statements which describe what you do then:

-

__ I check the target-language material against the source text, and make changes if I judge this material unsatisfactory.

__ sometimes

__ often

__ always

-

__ I check the target-language material for language problems (grammar, punctuation, spelling, idiom, style, good fit with those parts of the translation which I have done myself) but I do not check this material against the source text.

__sometimes

__often

__always

-

__ I skip over the target-language material, not checking it at all.

__sometimes

__often

__always

8. If you have TM installed on your computer or access it over a network, place an X beside all the statements which describe how you use it:

__ I use TM as a bilingual database. That is, I enter a source-text expression in a search box and then I examine the hit list I receive in order to see whether there is any useful target-language material in the Memory.

__ I use TM to move through a text and display possible translations one unit (phrase, sentence) at a time. If I like the suggestion, I insert it into my translation as is or with changes.

__ I use TM to automatically replace source-language with target-language wordings for every (full or fuzzy) match it finds. I may then make changes in these wordings or leave them unchanged.

9. If you have TM installed on your computer or access it over a network, place an X beside the statement that most accurately describes your situation:

__ I use the TM program whenever I wish and in whatever way I wish.

__ My employer, or one or more of the translation agencies I work for, requires me to use the TM program.

__ One or more of my clients require me to use a TM program.

10. If you are required to use TM, place an X beside any of the following statements which apply to you:

-

__I am required to use 100% matches without making any changes.

__sometimes

__often

__always

-

__I receive no credit for 100% matches.

__sometimes

__often

__always

-

__I receive reduced credit for 100% or fuzzy matches.

__sometimes

__often

__always

“Credit” means payments made to you (if you are independent) or recognition by your employer that you have translated a certain number of words (if you are salaried).

10a. If you revise other people’s translations, in a situation where they are required to use TM, do you check to see whether they have in fact used it?

___ I’m not required to make such a check while I revise, and I don’t.

___ I’m not required to make such a check while I revise, but I do check (always or sometimes)

11. When you use TM to search for matches, or when texts have been pre-processed through TM before you receive them, how often does the program find useful matches for a very large proportion of any given text? (“useful” means useable with few or no changes)

__Rarely or Never

__Occasionally

__Frequently

When you use TM to search for matches, or when texts have been pre-processed through TM before you receive them, how often does the program find useful matches for a moderate proportion of any given text?

__Rarely or Never

__Occasionally

__Frequently

When you use TM to search for matches, or when texts have been pre-processed through TM before you receive them, how often does the program find useful matches for only a small proportion or no portion of any given text?

__Rarely or Never

__Occasionally

__Frequently

12. Your current general attitude toward TM:

__ On the whole, I like it.

__ I have mixed feelings about it.

__ Basically, I hate it.

13. Your feeling about the specific way(s) you use TM:

-

As a bilingual database:

___ Like it

___ Mixed feelings

___ Hate it

___ Don’t use TM this way

-

Moving through the text a unit at a time and accepting or rejecting proposed matches:

___ Like it

___ Mixed feelings

___ Hate it

___ Don’t use TM this way

-

Having the TM automatically insert any (full or fuzzy) matches:

___ Like it

___ Mixed feelings

___ Hate it

___ Don’t use TM this way

-

Receiving texts for translation which already have TM-generated target-language material inserted:

___ Like it

___ Mixed feelings

___ Hate it

___ Don’t use TM this way

14. If you worked with TM both before and after 2010:

____ my use of TM (how often and the way I use it) has not changed much since 2010

____ my use of TM (how often and the way I use it) has changed considerably since 2010

____ my attitude toward TM (like it, hate it, mixed feelings) has not changed much since 2010

____ my attitude toward TM (like it, hate it, mixed feelings) has changed considerably since 2010

If your use has changed considerably, how?

If your attitude has changed considerably, how?

15. If you have mixed feelings about TM or hate it, why?

__ I feel I’m not in control of the translation process.

__ It’s time-wasting moving through a text a unit at a time, because the TM does not find useable matches often enough.

__ I want to compose my own sentences, not revise old translations.

__ It’s hard to learn the program.

__Technical problems keep coming up when I use it.

__ In the environment in which I work, it’s difficult or impossible to inspect sections of the source text or translation on which I am not currently working.

__ Other reasons:

16. If on the whole you like TM, why?

17. Anything else you would like to say about TM:

(7 similar questions about machine translation here)

25. Your comments on this survey.

Biographical note

Brian Mossop was a Canadian Government translator, reviser and trainer from 1974 to 2014. He is also a part-time instructor at the York University School of Translation (1980 to the present). He is the author of the widely used textbook Revising and Editing for Translators (4th ed., Routledge, 2019) and has published some 60 articles on various aspects of translation. In retirement, he continues to lead revision workshops for professional translators in Canada and abroad, and does occasional freelance and volunteer translation work.

Notes

-

[1]

I was a full-time Canadian Government translator from 1974 to 2014. During the final eight years, I used Translation Memory every day.

-

[2]

The results were reported at a panel on “translation and interpreting as socially situated activities” during the annual conference of the American Association for Applied Linguistics in March 2011.

-

[3]

As a former translator, I would write a love letter to the Google web browser, the advent of which in 1998 completely transformed term and concept research for the better. However, as a daily user of Memory, my letter would express mixed feelings (see Mossop, 2014, pp. 584 and 588). On the plus side: I had access to the entire huge Translation Memory database, which I could use as a concordance; the Memory system (MultiTrans) was an add-on to Word, so that I could see a full page of text with formatting rather than just isolated segments; I was not required to use any of the matches; and I had two screens operating in tandem, so that I could view anything I wished (on the second screen) without having to switch windows or reduce window size. On the minus side, less credit was given for 100% matches and fuzzy matches over 75%, and correspondingly less time was allowed to complete the translation, though with 30 years’ experience behind me, I was translating fast enough that I could ignore such matches if I wanted to compose my own wording, and still get sufficient credit and complete my translations on time. The main negative feature was that matches were pre-inserted in the file I was given for my translation, and their very presence on my screen led me to waste time reading them and deciding whether to use them, revise them or ignore them. I became a translator in order to translate (compose suitable wordings in the target language), not to fix someone else’s recycled wordings.

-

[4]

All respondents were members of the Association of Translators and Interpreters of Ontario. I am a member, but I did not complete either survey. The survey was addressed to “Fellow ATIO members” and I explained that I would report the results at a meeting of the American Association for Applied Linguistics in March 2011 and at a meeting of the Canadian Association for Translation Studies in May 2017, and I would make the results available to all respondents. The 2011 survey was limited to an easily reachable subset of translators in Ontario in order to make analysis of the results manageable: I did not know how many of the 126 recipients would respond and I had limited time for analysis before the scheduled presentations. For the 2017 survey, I used the same target group in order to achieve comparability (though only 4 individuals answered both surveys). The restriction to French-to-English translators enabled me to avoid considering language pair and direction as an attitude-determining factor. Some of the results of the 2017 survey were also presented at a conference of translators who work for the Toronto translation company Multi-Languages in October 2017 (Mossop, 2017).

-

[5]

A follow-up question (Question 13 in the Appendix), which I will not discuss here, asked respondents to break down their attitude: did they like, hate or have mixed feelings about four different ways of using Memory. Many respondents had different feelings about different uses.

-

[6]

Semantically, “like” is not the opposite of “hate.” In retrospect, it would have been better to use “love or like” and “dislike or hate.” It’s possible that some respondents chose “mixed feelings” even though they disliked Memory, simply to avoid reporting that they “hated” it, while for other respondents, “mixed” perhaps meant a balance of positive and negative feelings. Be that as it may, the quantitative results on the closed questions are not the focus of this article.

-

[7]

“Credit” means either payment (to freelance translators) or word count (for salaried translators who are expected to translate a given number of words per average day).

-

[8]

I did correlate the like/hate responses for 2017 with the respondents’ gender. The proportions of men and women respondents reflected the total population of French-English Certified Translators in Ontario: 30% of respondents were men, while 28% of the Certified Translators were men. However, of the 12 male respondents, only 4 (33%) had used Memory, while of the 27 women who replied, 18 (66%) had used it. With so few male users, the figures are probably not very informative about gender-based differences in liking/disliking: of the 4 men, 3 liked Memory and 1 had mixed feelings; of the 18 women, 8 liked Memory, 8 had mixed feelings and 2 hated it. Perhaps the large proportion of male respondents who do not use Memory is indicative of some gender-related difference, but this could be determined only by questioning both male and female non-user respondents.

-

[9]

I neglected to ask respondents about the nature of the “requirement” to use Memory. It can mean different things: a requirement to work in a Memory environment with all texts and at least consider any matches; pressure to use matches rather than produce one’s own translation because of the imposition of “discounts”; compulsory use of 100% matches without revision.

-

[10]

Question 9 allowed respondents to distinguish employers/agencies from clients, but here the results are combined. There are 25 replies in 2017 even though only 22 people had used Memory, because 1 person did not answer and 4 people gave both answers (they had worked in more than one situation).

-

[11]

Of the 4 individuals who responded to both surveys, the 2 who were not required to use Memory liked it both times, while the 2 who were required to use it went from “like” in 2011 to “mixed feelings” in 2017.

-

[12]

Since this is not a quantitative study, the number of items under each heading has no particular significance. It does not reflect the frequency of mentions in the survey responses.

-

[13]

Translation Memory was designed by engineers to help the software localization industry produce, in many languages, a high volume of frequently updated texts featuring many repetitions of the same wording (Garcia 2007, p. 58). When the technology was applied to non-repetitive texts, problems arose (Garcia, 2006). Also, because there was little input on design from translators, the engineers failed to grasp that translators work on texts, not on isolated segments. Screen displays in widely used Memory environments often do not show the text surrounding the passage on which one is currently working. Even when more than one sentence is visible, each one appears unformatted in a separate box. Dividing or merging sentences (in order to improve the writing quality) is typically a tiresome chore. Since the translator cannot see each sentence in the context of a formatted Word-like page (except sometimes by switching to a window (usually a read-only window) where the current state of the translation can be viewed as it will appear in Word), he/she is not constantly visually reminded that the current passage is part of something larger. Such a reminder is vital because the context of the source-language segment being translated may differ greatly from the context in which that same segment or a similar segment appeared in texts stored in Memory. As a result, the old translation may not work.

-

[14]

When I was a unionized Canadian Government translator, technological change was not a bargainable matter under labour relations legislation. However, union and management did sign letters of agreement to consult on the matter, which may have influenced the positive conditions described in note 3 above.

-

[15]

In a review of research on Memory, Christensen and Schjoldager (2010, p. 98) state that “Most practitioners seem to take for granted that TM technology speeds up production time and improves translation quality, but there are no studies that actually document this.” Evidence may be available in unpublished studies conducted by translation providers, but it is also possible that managers either believe without evidence that quality or speed or both are improved, or they have simply adjusted their concept of quality to accommodate Memory and MT outputs.

Bibliography

- Bédard, Claude (2014). “Le traducteur de demain… et son chien.” Circuit, 122. [https://www.circuitmagazine.org/dossier-122/le-traducteur-de-demain-et-son-chien].

- Bundgaard, Kristina (2017). “Translator Attitudes towards Translator-computer Interaction—Findings from a Workplace Study.” Hermes, 56, pp. 125-144.

- Cadwell, Patrick, Sheila Castilho, Sharon O’Brien and Linda Mitchell (2016). “Human Factors in MT and Post-editing among Institutional Translators.” Translation Spaces, 5, 2, pp. 222-243.

- Christensen, Tina Paulsen and Anne Schjoldager (2010). “TM Research: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?” Hermes, 44, pp. 89-101.

- Christensen, Tina Paulsen and Anne Schjoldager (2016). “Computer-aided Tools: The Uptake and Use by Translation Service Providers.” JosTRans, 25, pp. 89-105.

- Dillon, Sandra and Janet Fraser (2006). “Translators and TM: An Investigation of Translators’ Perceptions of Translation Memory Adoption.” Machine Translation, 20, pp. 67-79.

- Ehrensberger-Dow, Maureen and Sharon O’Brien (2015). “Ergonomics of the Translation Workplace: Potential for Cognitive Friction.” Translation Spaces, 4, 1, pp. 98-118.

- Garcia, Ignacio (2003). “Standard Bearers: TM Brand Profiles at Lantra-L.” Translation Journal, 7, 4. [http://www.translationjournal.net/journal/26tm.htm].

- Garcia, Ignacio (2006). “Translators on Translation Memories: A Blessing or a Curse?” In A. Pym, A. Perekrestenko and B. Starink, eds. Translation Technology and its Teaching, Intercultural Studies Group, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 97-105.

- Garcia, Ignacio (2007). “Power Shifts in Web-based Translation Memory.” Machine Translation, 21, pp. 55-68.

- Guerberof, Ana (2013). “What Do Professional Translators Think about Post-editing?” JoSTrans, 19, pp. 75-95.

- Koskinen, Kaisa and Minna Ruokonen (2017). “Love Letters or Hate Mail? Translators’ Technology Acceptance in the Light of their Emotional Narratives.” In D. Kenny, ed. Human Issues in Translation Technology. London and New York, Routledge, pp. 8-24.

- Läubli, Samuel and David Orrego-Carmona (2017). “When Google Translate is Better than some Human Colleagues, those People are no Longer Colleagues.” Proceedings of the 39th Conference Translating and the Computer, London, UK, pp. 59-69.

- LeBlanc, Matthieu (2013). “Translators on TM: Results of an Ethnographic Study in Three Translation Services and Agencies.” International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research, 5, 2, pp. 1-13.

- LeBlanc, Matthieu (2014). “Les mémoires de traduction et le rapport au texte: ce qu’en disent les traducteurs professionnels.” TTR, 27, 2, pp. 123-148.

- LeBlanc, Matthieu (2017) .“I Can’t Get No Satisfaction! Should We Blame Translation Technologies or Shifting Business Practices?” In D. Kenny, ed. Human Issues in Translation Technology. London and New York, Routledge, pp. 45-62.

- Marshman, Elizabeth (2012). “In the Driver’s Seat: Perceptions of Control as Indicators of Language Professionals’ Satisfaction with Technologies in the Workplace.” Translating and the Computer 34. [http://www.mt-archive.info/Aslib-2012-Marshman.pdf].

- Marshman, Elizabeth (2014). “Taking Control: Language Professionals and Their Perception of Control When Using Language Technologies.” Meta, 59, 2, pp. 380–405.

- McBride, Cheryl (2009). TM Systems: An Analysis of Translators’ Attitudes and Opinions. M.A. Thesis. School of Translation and Interpretation, University of Ottawa. [https://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/28404/1/MR61311.pdf].

- Mogensen, Else (2000). “Orwellian Linguistics.” Language International, October, pp. 28-31. [http://www.mt-archive.info/jnl/LangInt-2000-Mogensen.pdf].

- Mossop, Brian (2014). “Motivation and De-motivation in a Government Translation Service: A Diary-based Approach.” Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 22, 4, pp. 581-591.

- Mossop, Brian (2017). “Conflict over Technology in the Translation Workplace.” Multi-Languages Annual Conference 2017 [video presentation]. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aAPQ_4_LRwM&list=PLIreXuKKKiFe9MP2ntmFJn2Fm_l2bVkIx&index=7&t=0s].

- Ruokonen, Minna and Kaisa Koskinen (2017). “Dancing with Technology: Translators’ Narratives on the Dance of Human and Machinic Agency in Translation Work.” The Translator, 23, 3, pp. 310-323.

- Taravella, AnneMarie and Alain O. Villeneuve (2013). “Acknowledging the Needs of Computer-assisted Translation Tools Users: The Human Perspective in Human-Machine Translation.” JoSTrans, 19. [https://www.jostrans.org/issue19/art_taravella.php].

- Toudic, Daniel and Guillaume de Brébisson (2011). “Poste du travail du traducteur et responsabilité: une question de perspective.” Revue ILCEA, 14. [https://ilcea.revues.org/1043].

List of tables

Table 1

Answers to Survey Question 12

Table 2

Answers to Survey Question 9[10]

Table 3

Question 12 vs Question 9[11]

Table 4

Expressions of negative attitudes to Memory 2011

Table 5

Expressions of negative attitudes to Memory 2017

Table 6

Expressions of positive attitudes to Memory 2011

Table 7

Expressions of positive attitudes to Memory 2017

10.7202/1037748ar

10.7202/1037748ar