Abstracts

Abstract

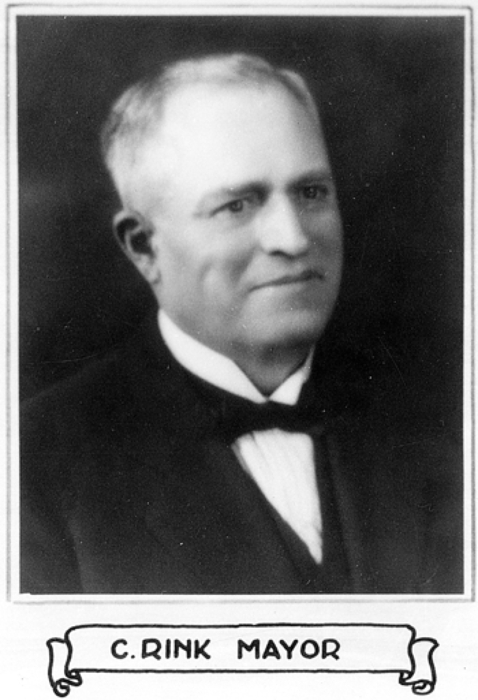

Little has been written about Depression-era municipal politics in Canada. This article considers Regina’s experience by examining the turbulent career of its most successful populist politician, Cornelius Rink. He was twice elected mayor (in 1933 and 1934) on the strength of his appeal among Regina’s immigrant and working-class voters. Then in 1935, in the aftermath of the On-to-Ottawa Trekkers’ sojourn in the city and a riot there on 1 July, social democrats and trade unionists with an attractive platform and a more effective organization managed to unseat Rink with the votes of many of those same immigrant and working-class Reginans. Cornelius Rink was Regina’s first populist mayor, but as it turned out he would be its only one.

Résumé

On a peu écrit sur la politique municipale à l’ère de la Grande Dépression au Canada. Cet article jette un regard sur l’expérience de Regina en examinant la carrière mouvementée de son politicien populiste le plus célèbre, Cornelius Rink. Il a été élu deux fois maire (en 1933 et 1934) par la seule force de son attrait auprès des électeurs immigrants et des classes populaires de Regina. Puis en 1935, à la suite du passage à Regina des manifestants de la Marche vers Ottawa (On to Ottawa Trek) et l’émeute du 1er juillet, les socio-démocrates et les syndicalistes, armés d’une plate-forme attrayante et d’une organisation plus efficace, parviennent à déloger Rink grâce aux voix de bon nombre de ces mêmes Réginois immigrants et populaires. Cornelius Rink fut le premier maire populiste de Regina. Or, il s’avérera en être le seul.

Article body

Histories of the Depression decade of the 1930s invariably emphasize the extent of voters’ growing disenchantment with Canada’s traditional political leadership, political parties, and economic orthodoxy. The 1930s are portrayed as a period of great political experimentation and innovation, which gave rise to new political parties such as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and Social Credit.[1] These new parties are sometimes regarded as expressions of “populism” or are deemed to be “populist” in terms of their ideology. David Laycock has provided the most wide-ranging analysis of the populist phenomenon in western Canada. He argues that the CCF was an expression of “social democratic populism.” Social Credit he characterizes as “plebiscitarian populism.”

Laycock did not examine the municipal political arena in the 1930s, but others have, and in some instances have argued that the same or a similar “populist” phenomenon appeared in local politics.[2]

Daniel Francis, for example, has described Louis D. Taylor (mayor of Vancouver in the early 1930s) as “a classic outsider who was disdained by the elites . . . a bit pushy, dangerously radical in his politics and unconnected by family or business to the city’s dominant social circles . . . But he had neither the personal charisma nor the bombastic rhetoric of the true demagogue. It is more accurate to call him a populist . . . He appealed to voters because he supported causes of immediate practical importance to them.”[3]

David Ricardo Williams has characterized Gerald Gratton McGeer (who succeeded Taylor as mayor of Vancouver in 1935) as a “flamboyant demagogue” who “saw himself as one chosen, or who ought to be chosen, to be like [Abraham] Lincoln for great causes—to champion the rights of the oppressed, to free the impoverished . . . the tribune of the people, called to banish wrong and injustice.”[4]

Of those who have written about municipal politics in Canada during the Great Depression, only John Taylor has attempted any sort of comparative analysis. In a 1974 survey of the four western provinces he argued that “there emerged in most, but not all of the major centres . . . successful or nearly successful bids for municipal power by left-wing parties usually, by 1935, connected with the CCF. Again, there also emerged in most, but not all of these centres, charismatic populists as mayors. And there variously existed, emerged or disappeared a variety of non-partisan, centre-right umbrella groups in almost all the major centres.”[5]

Taylor drew attention to similar contests between socialists and charismatic populists in other Canadian cities in a more comprehensive survey published in 1981. What was remarkable about the 1930s, and especially the first half of the decade, he argues in “Mayors à La Mancha,” was the extent of voters’ disenchantment with the status quo (non-partisan politics loosely identified with Liberal and Conservative urban elites) and their turning to “charismatics” to lead their cities in a time of great crisis.[6]

There has been little in the way of critical writing about Depression-era municipal politics in Regina.[7] This article will seek to provide a fuller account of Regina’s experience by analyzing the turbulent career of its most successful “populist” politician, Cornelius Rink.

Born in Holland, Rink arrived in Regina by way of the Transvaal, New York, Chicago, and Winnipeg in 1907, at the age of thirty-five. While Regina was considerably smaller than even Winnipeg, its prospects must have seemed encouraging for a newcomer of modest means, as Rink most likely was. Settlers were arriving in record numbers to take up land in the new province of Saskatchewan. Retail and wholesale trade was booming in Saskatchewan’s capital city, and so was building construction and real estate. Regina’s population had nearly tripled since the turn of the century, from 2,249 in 1901 to 6,169 in 1906, and would reach 30,213 by 1911.

Regina’s population was also becoming more ethnically diverse. Those of “British” ethnic origin (principally Canadians who had come to the city from other provinces or immigrants from Great Britain) were of course the largest group—69.4 per cent by 1911. Germans were the next largest, comprising 9.1 per cent of the city’s population by 1911. The German community in Regina was becoming large enough to support a variety of ethnic and religious institutions, including a newspaper, the Saskatchewan Courier, which commenced publication the year Cornelius Rink arrived in the city. Ukrainians and other Central and Eastern Europeans accounted for another 12 per cent by 1911.[8]

Class distinctions were becoming more sharply drawn too. There was a growing sense of working-class consciousness: trade unions were beginning to appear, and in 1907 they founded the Regina Trades and Labour Council (RTLC).[9]

The city’s social morphology reflected these ethnic and class divisions. For the most part, immigrant and working-class Reginans lived east and north of the downtown core, which was itself located south of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) main line. Its more well-to-do (and overwhelmingly Anglo-Celtic) citizens showed a strong preference for the residential neighbourhoods west and south of downtown.[10]

This latter group was the city’s dominant force: they shaped Regina’s economic growth and set its social standards. They also played the leading role in municipal politics, thanks in no small part to the fact that from 1883 on (when Regina was incorporated as a town) there had been a property qualification for voting in municipal elections and for seeking public office as an alderman or mayor. Businessmen held most of the seats on successive town and city councils, and monopolized the mayoralty. Three of the first five men who served as mayor of the city of Regina—J. W. Smith, R. H. Williams, and Robert Martin—were prominent retail merchants. H. W. Laird had made his money in wholesale trade, Peter McAra in fire insurance and real estate.[11]

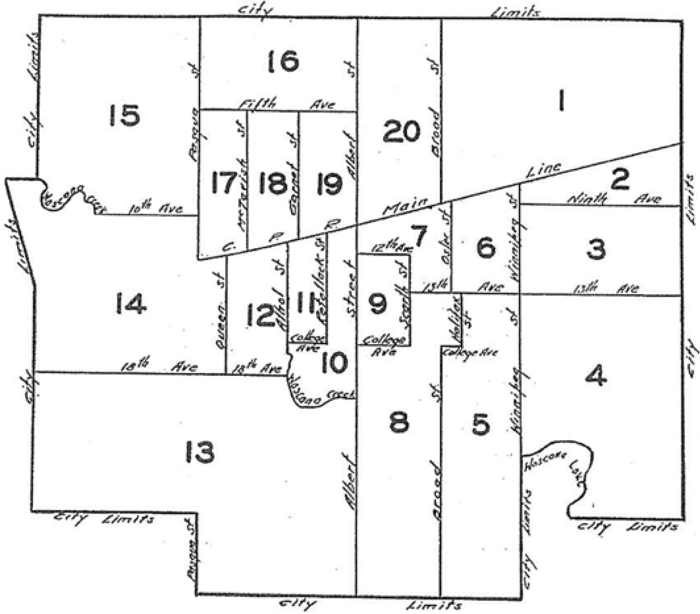

Rink settled in the East End (so named because it was located immediately east of downtown) and went into the real estate and insurance business. He was soon attracted to municipal politics, and in 1911 won election to city council in Ward 1 (see figure 1). Elected again in 1913, thanks to a strong (albeit informal) organization and his fluency in German, Rink proved to be an aggressive champion of the interests of his ward and a vocal critic of Regina’s business elite.

Figure 1

Wards, 1911–1913, polling subdivisions, 1914–1918

In 1914 Cornelius Rink offered himself as a candidate for mayor. He claimed to be the people’s champion and insinuated that his opponent (James Balfour, a prominent and well-connected lawyer) had been put up by a “small, influential, but notorious clique.”[12] At one meeting he told Reginans to “vote for Rink if they wanted a mayor who knew the city’s business and was prepared to carry out their wishes, and if they did not want a representative whose main qualifications were his ability to play golf and attend social functions.”[13]

Rink also boasted that he was “a true friend of the labor men.”[14] He sought their support by pointing to his success in persuading the city to lay water mains by day labour, rather than give the work to large contractors (and their trenching machines). With Regina having fallen on hard times by 1914, this had provided jobs for men who would otherwise not have had work. If elected mayor, Rink promised to undertake all city construction work by day labour.[15] But Rink’s foreign birth, his participation in the South African War (on the Boer side), and the fact that he again addressed campaign meetings in the East End in German all counted against him in 1914.

Earlier in the year, voters had decided to do away with the ward system, but the five polling subdivisions created for the 1914 election followed the same boundaries the wards had. James Balfour was victorious in Polling Subdivisions 2, 3, 4 and 5; Rink won only Polling Subdivision 1 (see figure 1).

Cornelius Rink’s political star continued to fade. Six times he sought re-election as an alderman between 1915 and 1928, but Rink won only once (in 1924). From all appearances, Rink’s municipal political career was over. Perhaps recognizing this, he turned his attention to provincial politics in the late 1920s. In 1925 he helped to found a Conservative club in the East End. Rink and some other local Conservatives also established a weekly newspaper in Regina. Though it proved to have a short life (less than a year), the New Standard was credited with helping to elect a Conservative MLA in the city for the first time in 1925. Rink assumed a more visible role in the 1929 provincial election, speaking at a number of Conservative meetings in the city. This time the Conservatives won, defeating a Liberal regime that had been in office since 1905, and J. T. M. Anderson’s Co-operative government took power. Those who had contributed to the victory in large ways and small were rewarded for their political loyalty: Rink was granted the franchise to collect empty beer bottles in Regina and return them to the breweries. (Beer Bottle Dealers Limited was duly incorporated in September 1930 and commenced business.)[16]

During the war years and the 1920s the strongest challenge to Regina’s business elite came from a succession of Labour aldermen elected with the votes of those same immigrant and working-class Reginans to whom Rink had appealed. The first was Harry Perry, a bookbinder by trade and vice-president of the RTLC, who won a seat on city council in 1915. His best showing was in Polling Subdivisions 1 and 5 (where he finished fourth and third respectively)[17] (see figure 1). Perry became something of a fixture at City Hall, winning re-election five more times, and between 1922 and 1925 there were two Labour aldermen. The organizational support of the RTLC and the creation of a succession of formal political parties after 1915 doubtless contributed to Labour’s electoral success. So did the widening of the municipal franchise.[18]

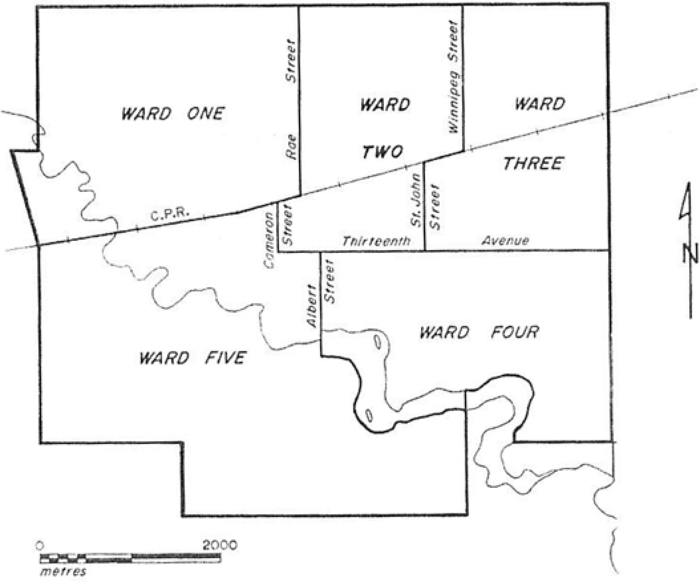

Another newcomer to city council during these years was M. J. Coldwell, a Regina school principal first elected as an independent candidate in 1921 (and re-elected in 1923, 1926, and 1928). Although Coldwell did not at first officially align himself with Labour’s political organization, he shared many of their concerns, notably a desire to reform the administration of relief in the city. Then in 1929 Coldwell and other social democrats (among them fellow schoolteacher Clarence Fines) joined with the RTLC in founding the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Coldwell ran as an ILP candidate in the 1930 civic election and won a fifth term on city council.[19] He carried every polling subdivision in the city in 1930, save for Polls 9, 10, 11, and 13 (see figure 2).

Figure 2

Polling subdivisions, 1927–1934

By this time Regina (now a city of 53,209) was beginning to feel the full impact of slumping farm commodity prices and the drought that was devastating much of southern Saskatchewan. Unemployment reached unprecedented levels in 1930 and 1931, as retail and wholesale firms dependent on the farm trade began to let men go. So did the big General Motors plant (the city’s largest private employer since it had opened in 1928). When General Motors shut down its assembly line in August 1930, it laid off its entire staff. Building construction also came to an almost complete standstill. In 1929 the city had issued a record $10 million worth of building permits; two years later the total was only a tenth of that, and skilled and unskilled construction workers alike faced bleak prospects. By June 1931 fully 23 per cent of all adult male wage earners (3,872 men) in Regina were out of work.[20]

And so more and more Reginans found themselves dependent on the city for relief. What they received was hardly generous. Grocery relief, provided in the form of a voucher, was based on an allowance of $18 a month for a family of four. There were other vouchers covering rent and fuel, and relief recipients were required to promise to repay the amount of their debt. The city initially distributed relief itself but in September 1931 turned the work over to a private body, the Civic Relief Board.[21]

The distribution of relief did not long escape criticism, from the Labour aldermen on city council and from local Communists. Active in Regina since the early 1920s, the Communist Party of Canada (CPC) remained largely unnoticed there—except by the RCMP—until 1930, when a local branch of the National Unemployed Workers’ Association (NUWA) was established. The NUWA soon became the noisiest and most persistent critic of the city’s relief policies. In November 1930 it attempted to have the relief officer, William Redhead, dismissed on account of his “discourteous and autocratic manner,” but a civic enquiry exonerated him.[22] The NUWA also sponsored Regina’s first May Day rally, in 1931. It drew 8,000 people to the city’s Market Square and ended in violence when some onlookers took objection to the presence of the Communists’ red flag.[23]

These stirrings on the far left provoked a response from some of the city’s businessmen, who proceeded to establish the Regina Taxpayers’ Association (RTA) in September 1931. There was talk initially of sponsoring candidates in the fall municipal election. “We don’t want Communists running this city, but they will be here before you know it,” warned W. H. A. Hill, a prominent Regina businessman and one of the founders of the RTA. “What we want to see is taxpayers running for office who will keep the taxes down.”[24] In the end, the RTA did not put any candidates in the field, but it did press city council to practise “rigid economy” and reduce taxes. Council did not need much convincing, for all but the two Labour aldermen (M. J. Coldwell and Garnet Menzies) were wedded to fiscal orthodoxy. With relief accounting for an increasing proportion of the municipal budget, other expenditures would have to be pared to the bone. Council’s most dramatic gesture came in October 1931, when it cut civic salaries by 10 per cent. This, its proponents claimed, would save the city $40,000 and taxpayers one mill on their property taxes. Regina’s school boards, the public library, and the city-run General Hospital promptly followed suit.[25]

As the Depression deepened, Regina voters became more willing to vote for candidates who challenged economic and political orthodoxy. This desire for change would propel Cornelius Rink back into City Hall in 1931 and eventually into the mayor’s chair.

In 1931 the municipal ballot contained an impressive array of choices, with four candidates for mayor. Two were members of Regina’s business elite: incumbent James Balfour and the man he had defeated the year before, long-time mayor James McAra. For the first time there was also a Communist in the field, Herbert Court. And then there was Walter Stowe, a Canadian National Railway locomotive engineer who had never before sought a seat on city council. He was running for mayor, he told voters, to “stimulate the people to rise in their might.” Stowe had little in the way of a formal platform, save for a pledge that he would reduce the tax burden on small property owners by firing overpaid city officials. But this was enough for many of those who lived in the immigrant and working-class neighbourhoods east and north of downtown. Stowe polled the largest number of votes in Polling Subdivisions 1, 3, 4, 6, and 14–19 and came second in Polling Subdivisions 2 and 20 (figure 2). Overall, Stowe finished second, ahead of James Balfour but behind James McAra, who was elected to his fifth term as mayor.[26]

Cornelius Rink was one of twenty-one candidates seeking an aldermanic seat, and his campaign was also full of populist rhetoric. He was “running as an independent candidate for the poor people,” Rink told voters at a North Side meeting as he took dead aim at the Civic Relief Board. It was composed of “lawyers and professional men, who knew nothing of the needs of the poor.” In appealing to the readers of Der Courier und derHerold, Rink made much of his accomplishments as an alderman prior to 1914 and promised to find work for Reginans who were on relief. Rink garnered the largest vote of any candidate in Polling Subdivisions 2, 3, 4, and 6 (and the second largest of any of the winning candidates in Polling Subdivisions 1 and 14–20) and won an aldermanic seat with a handsome majority (figure 2). Only incumbent Labour alderman Garnet Menzies garnered more votes in 1931.[27]

It should not have been surprising that Alderman Rink took a keen interest in the provision of relief to the city’s unemployed. But he invariably found himself in the minority, along with the Labour aldermen. (There were two initially, and then three after Alban C. Ellison was successful in a by-election in April 1932.) Thus when the Civic Relief Board decided at the beginning of the year to reduce the grocery allowance from $18 to $16 a month as an economy measure, Rink, M. J. Coldwell, and Garnet Menzies all objected, claiming that the new allowance would be insufficient to feed a family. Their efforts to persuade the board to reconsider the cut proved fruitless: when Coldwell proposed a resolution to this effect in March, it obtained only three affirmative votes. A second attempt to restore the original allowance in May, after Ellison had taken his seat on city council, was not successful either.[28]

Rink also waged a one-man campaign against waste and mismanagement. He singled out the Civic Relief Board, the General Hospital, and the Regina Exhibition Association (which operated the city’s annual summer fair) for special condemnation, but in none of these cases did he provide much in the way of evidence. Although his “charges” made good copy for the newspapers, none of his colleagues showed any enthusiasm for conducting a more thorough investigation.[29]

Voters were treated to more of the same during the 1932 election campaign when Rink ran for mayor. “My platform will be cutting down of expenditures, relief for those who deserve it and no relief for those who do not,” he declared in announcing his candidacy.[30] Rink boldly claimed he could save the city $150,000 in 1933 by reducing staff at the General Hospital, eliminating the annual grant to the Board of Trade, and cutting the salaries of the senior management of the Regina Exhibition Association. He also promised to protect Regina’s small taxpayers who were in arrears and in danger of losing their homes.[31]

In 1932 Rink was again very much the outsider, as he had been in 1914 when he had first sought the mayoralty. He was a very small player in the real estate business; James McAra’s much larger real estate and insurance business (which he and his brother had founded in the boom years before the First World War) had made him a wealthy man. McAra was also a popular war veteran (he had served for a time on the national executive of the Great War Veterans’ Association). Seeking his sixth term as mayor, McAra ran a low-key campaign, conducted largely over the radio. McAra made much of his experience, claiming that he was the best choice to guide the city through troubled times. He also coyly expressed the hope that voters would re-elect him so that he could preside over the World’s Grain Exhibition and Conference, which was to be held in Regina in 1933.

The third candidate was Charles Dixon, a successful Regina dentist and an alderman with four years’ experience. Like Rink, Dixon promised “relief to the deserving” and emphasized the need for a further paring civic expenditures. But Dixon proposed to appoint a small commission of “expert men” to provide advice on where the cuts should be made.[32]

Herbert Court rounded out the field, having created something of a sensation in 1931, when he had first run as a Communist for mayor. But in 1932, Regina’s newspapers paid little attention to him.

On the other hand, the Leader-Post became quite concerned by the prospect of Cornelius Rink gaining the mayoralty. In a 23 November editorial the newspaper pulled no punches:

Those who know the . . . candidates and the nature of their appeal will recognize that Mr. Rink will make an appeal to a section of the people among whom Mr. McAra and Dr. Dixon will not poll a great number of votes. This means that Mr. McAra and Mr. Dixon will be appealing largely to the same people for support and if both remain in the field they will divide this vote.

With such a division existing it would appear probable that Mr. Rink has a good chance of election and of becoming mayor of Regina for 1933.

Whoever is mayor next year will have a busy time. There is the matter of civic administration, a heavy task in times like the present, and in addition there will be the World’s Grain Show, greetings to distinguished visitors from other lands, welcoming numerous international conventions held in connection with the Grain Show, and numerous other duties and responsibilities of an honorary nature.[33]

If this was a hint that either McAra or Dixon should withdraw from the field, neither showed any inclination to do so.[34]

Rink was also snubbed by the newly formed Civic Government Association (CGA). It was modelled on a similar organization in Calgary, though in some respects it was more an offshoot of the RTA. The CGA purported to be concerned only with encouraging greater citizen participation in local politics, but its real raison d’être was to prevent Regina’s socialists from capturing City Hall. To this end it endorsed a slate of aldermanic candidates, three of whom were elected.[35] While the CGA did not officially endorse a candidate for mayor, it did issue a statement declaring that “both the present mayor and Ald. Dixon are very good citizens. Members of the CGA and any elector in this city would make no mistake in voting for either of them as mayor for the year 1933.”[36]

As the campaign reached its climax, Rink concentrated his attention on Mayor McAra. He criticized the mayor for avoiding public meetings in favour of the radio, and claimed that McAra’s reluctance to meet the voters directly also extended to City Hall. “The mayor’s office door is so seldom open that its hinges are rusty,” Rink exclaimed at a campaign meeting on the North Side. If he was elected, Rink promised, “the mayor’s door would be open to all and sundry and the people would know what went on in the city hall.”[37]

As the ballots were being counted on election night, it seemed at one point that Rink had won. In the end he did not, but just barely. The first count gave the mayoralty to James McAra by a mere five votes. Rink demanded a recount, but it increased McAra’s margin of victory to nineteen votes.[38]

Rink did win the mayoralty the following year, aided by the fact that there were no fewer than four “business” candidates seeking the honour: McAra again, and three incumbent aldermen (F. G. England, A. C. Froom, and J. C. Malone). This time the CGA clumsily sought to narrow the field, but none would agree to withdraw.[39] The CGA also gave some thought to endorsing one of the candidates, but decided in the end not to do that either.[40]

The 1933 mayoralty election was again principally a contest between McAra and Rink. Again McAra relied largely on the radio, but in 1933 Regina’s six-term mayor had little new to offer voters. To be sure, earlier in the year he had proposed an ambitious $1.6 million scheme to provide employment to Reginans who were on relief. But “Regina’s Recovery Act” (as one of the newspapers somewhat grandiosely labelled it) could be implemented, the mayor himself admitted, only if the senior governments agreed to assume two-thirds of the cost. No such agreement was immediately forthcoming. While McAra drew attention to his relief work scheme during the campaign, Rink ridiculed it as a hollow promise. “I say ‘hooray for Jimmy [McAra],’ but where is he going to get the money?”[41]

Rink’s bombastic style was better suited to the boisterous all-candidates’ meetings that had long been a staple of civic election campaigns, and he drew large crowds wherever he spoke. In 1933 he took to calling himself “Honest Conny” and promised voters “A New Deal and a Square Deal to All.” There would be “work instead of relief or cash instead of [grocery] orders,” though in his speeches Rink provided no real indication of what form the work might take or where the city would find the money to pay for it (or for cash relief, for that matter). Rink also committed himself to reducing the interest payable on city debentures and, as in 1932, pledged to reduce the tax burden by cutting expenditures.[42]

The turnout on election day was the heaviest in the city’s history (65.3%), and the outcome was not long in doubt, with Rink swept into office by a margin of more than 2,300 votes over his closest rival, James McAra. Rink was again victorious in the Polling Subdivisions he had carried in 1932, and in addition he won Polling Subdivisions 5, 18, and 20 (figure 2).

It was also to Rink’s advantage in 1933 that he faced four opponents whose appeal was strongest in the better-off neighbourhoods south and west of the downtown core. This enabled Rink to win with only a plurality of the votes cast. The Leader-Post had predicted early in the campaign that Rink would be elected under such circumstances—a prospect it clearly disliked (though it did subsequently commend him on his victory, albeit grudgingly).[43] There is also little doubt that the CGA’s efforts to narrow the field were motivated by a desire to prevent Rink from capturing the mayoralty. The Daily Star quoted the president of the CGA as stating that with so many candidates in the field for mayor there was “a danger of a man whom you all have in mind . . . being elected” and that this would be “ruinous to the city.”[44]

The CGA could draw more comfort from the aldermanic results. Four of the candidates it endorsed were elected (one, Dr. Charles Dixon, headed the poll), while only two of Labour’s nominees were. With three other CGA aldermen serving the second of their two-year terms in 1934, this ensured that the CGA would enjoy a comfortable majority on the new city council. While the CGA adopted no formal platform, the aldermen whom it endorsed had a number of beliefs in common, notably a commitment to fiscal orthodoxy and an enthusiasm for retrenchment. Indeed in 1933 the CGA aldermen had initiated a wide-ranging review of the civic administration that resulted in further salary cuts (from 10% to 50% on a sliding scale, with the highest-paid staff absorbing the greatest blow). Some civic departments had also been merged, all in the interest of “economy.”[45] Regina’s business community would look to these CGA aldermen to protect the city treasury and preserve Regina’s credit in the year ahead.

Rink could take great pleasure in his victory. At the age of sixty-two, he was now mayor of Saskatchewan’s’ largest city, the first Reginan not of British ethnic origin to hold this position. A small (and not terribly successful) businessman himself, Rink had also ended the long tradition of entrusting the city’s highest elected office to men of greater wealth and social status.[46]

The day after the election some unemployed showed up at City Hall to see if “Mayor Rink” had any work for them. Of course Rink was not yet the mayor (he would not take office until January 1934), but in the interval he did nothing to discourage such expectations. He wanted the unemployed to work rather than receive direct relief, Rink told the annual meeting of the South East Ratepayers’ Association early in December. “Those who are too lazy to work will be out of luck,” the mayor-elect warned, “but those who are willing to work and cannot get it will have their relief needs provided for.”[47]

A city council subcommittee had barely begun to identify appropriate relief work projects in mid-February when the mayor decided on his own initiative to put seventy-five relief recipients to work clearing melting snow and ice from city streets and culverts. While the men were to earn forty cents an hour, they would receive no cash; their wages were to be credited against the relief they had already received from the city.[48]

Rink’s action provoked a furore among the unemployed. Both the Regina Union of Unemployed (RUU) and the more militant Workers’ Protective Association (WPA) were quick to condemn the mayor’s use of “conscript labor” to clear the streets. Both demanded that if men were to be employed in this way, they should be paid in cash. The RUU wanted one-third of the forty cents an hour wage to be paid in cash, with the balance credited against past relief advances; the WPA insisted that the entire forty cents be paid in cash and that the “trade union rate of wages be paid to all tradesmen.”[49] It was at a WPA-sponsored meeting to protest the mayor’s actions that local Communists bestowed on him the sobriquet “Rockpile Rink.”[50] The mayor also received this anonymous letter: You may take this lightly but this is a threat not a promise. We the unemployed dont [sic] feel we should work for the amount we get in food. There should be some cash given for the credit work we are doing. You are in danger of being roughly handled if you do not grant our wishes. Your [sic] worse than McAra. You cant [sic] keep your promises but we can keep ours. So get busy. You know what Lenhard city constable got. Well your [sic] liable to get the same.”[51]

To all of this the mayor responded that the men were being put to work in this way only temporarily, and that there was no reason why they “could not pay back a small proportion of relief advances which they had received.” A more extensive works program would be instituted “as soon as funds are available,” Rink promised. He saved his harshest words for the Communists in the WPA. They were “mischief makers,” he declared and he would not be dictated to by them.[52] Rink also insinuated that the letter threatening “rough handling” had come from the WPA, but it promptly denied this.[53]

How difficult it would be to provide more of Regina’s unemployed with work in place of the “dole” became painfully evident when the city council subcommittee presented its report on 6 March, bluntly stating that it would be “utterly impossible for the City to find work for all of its unemployed, numbering as they do 2,518 active cases on Relief, with another 2,000 . . . on the border line.” It did compile a modest list of suitable projects, including the gravelling of some city streets in the East End and on the North Side, a scheme that the mayor had long favoured. Before the city could proceed, however, it had to obtain permission from the province to use funds earmarked for direct relief for this purpose instead. By the end of May the provincial government had not yet responded.[54]

Then came a provincial election and a change of government (from J. T. M. Anderson’s Co-operative Government to J. G. Gardiner’s Liberals). Mayor Rink headed a city council delegation that met twice with the new premier shortly after the election. They left the second meeting with a commitment from the province to fund two-thirds of the cost of a work relief scheme in Regina. There were some conditions of course: the city would have to submit a proposed list of projects to the province for approval, and the provincial contribution to such a work relief scheme would be limited to the amount it would have paid if the city had continued on the “dole” system.[55]

A detailed list of possible projects was quickly drawn up, referred to the provincial government, and approved. For two months (September and October) relief recipients were paid forty cents an hour in cash, up to the limit of their grocery relief entitlement; vouchers continued to be issued to cover the cost of rent, heat, and water. The men employed in this way worked at a variety of jobs: grading roads, repairing sidewalks and plank crossings, and planting trees and shrubs in city parks. Taken together, these projects generated a meagre $50,612 in wages.[56]

The provision of clothing to those who were on relief also proved to be a controversial issue in 1934. Clothing was at this time available only through private charity. In 1929 the Leader-Post had established a Community Clothing Depot, which collected and distributed used clothing. When the Regina Welfare Bureau was established in 1931 to coordinate the efforts of the various charitable organizations then engaged in relief work, it took over the operation of the Clothing Depot too. Most of what it gave out was also second-hand, but beginning in 1933 the bureau launched a fund-raising campaign as well and used the money collected to purchase new garments. There were the inevitable complaints from those on relief: much of the clothing was of poor quality, it often did not fit properly (and could not easily be exchanged), and the whole system was demeaning.[57]

By 1934 Regina’s unemployed organizations and the Labour aldermen were demanding that the Community Clothing Depot be abolished and that the Civic Relief Board implement an “open voucher” system. (Such vouchers would be redeemable at any retail outlet in the city.)[58] Rink also favoured the change, and in October city council instructed the Civic Relief Board to begin issuing vouchers for clothing upon the recommendation of the Welfare Bureau’s investigators. The bureau refused to co-operate, however, and Rink was obliged to back down. There would be no vouchers; the Community Clothing Depot continued to function.[59]

Rink naturally sought a second term; indeed he took the unusual step of announcing his candidature in July, months before the election. Eventually three more joined the race: James McAra, veteran alderman E. B. McInnis, and Herbert Court. Through September and October the CGA again sought to narrow the field by convincing one of them to withdraw. When none did, the CGA endorsed McInnis as its standard-bearer on 1 November.[60]

All of this did not go unnoticed in Der Courier und der Herold. On 17 October it declared,

Our present mayor, Cornelius Rink, old war horse that he is, has waged many election battles and won a large majority in last fall’s election. He wishes to remain mayor for another year so he can utilize his practical experience for the good of the city. For years there has been an unwritten law in our city, perhaps better referred to as a tradition, according to which every mayor serves a second year in office without being challenged. With Rink this does not seem to be the case, for there are a sufficient number of candidates who intend to ignore this tradition and contest this right. Is it possible that this is happening for the simple reason that Rink is, after all, nothing more than a “foreigner”?

When the CGA officially endorsed McInnis, Der Courier und der Herold reminded its readers that Rink was “the most suitable representative of the poor man and the small taxpayer . . . He has already held the office of mayor for a year, and has thus gained valuable experience. In order to be able to use this experience to the fullest, he would have to hold the high office of mayor for at least another year.”[61]

Mayor Rink blamed his lack of real accomplishments on a hostile city council and urged Reginans to elect one more in sympathy with his own views. His instructions to the voters were in fact quite explicit. Only the three incumbent Labour aldermen and CGA representative Ralph Heseltine were “desirable,” he declared early in the campaign: “If I had more like these behind me, I could do something.”[62]

Rink was re-elected, though he won only a plurality of the votes cast. James McAra came a close second (and captured Polling Subdivisions 2, 14, and 17, which had gone to Rink in 1932 and 1933). E. B. McInnis finished in third place and failed to carry a single poll. Once again Rink had benefited from the presence of two “business” candidates in the field.

What impact Der Courier und der Herold’s comments had on the outcome of the mayoralty race is difficult to determine in the absence of detailed data on the ethnic makeup of individual Regina neighbourhoods (and polling subdivisions). Rink again garnered the largest number of votes in the East End (Polling Subdivision 6) but a smaller percentage of the total vote there (66.7%, as compared to 70.5% in 1933). However, voter turnout was lower than it had been in 1933, as it was citywide.

When it came to choosing aldermen, Regina voters went only part way in meeting the mayor’s wishes. They elected two of Labour’s nominees (indeed Clarence Fines headed the poll in his first bid for a council seat), but three from the CGA’s slate. In the year to come, the CGA would still have a comfortable majority of six to four over Labour on city council. Rink nonetheless professed to be pleased with the outcome. “I sincerely hope we will have a council next year that will work with me for the good of the people,” he declared in an election night address to his jubilant supporters.[63]

In March 1935 city council did agree to replace grocery vouchers with cash, but the decision came only after considerable debate. City Commissioner R. J. Westgate argued against the change. Paying in cash would make relief “more attractive” and lead to an increase in the number of Reginans on the city’s relief rolls. It would also exacerbate the city’s financial problems, he warned. With the provincial government typically two to three months behind in paying its share of relief costs, Regina was already hard-pressed to pay for relief. Replacing grocery vouchers with cash would only add to the city’s financial burdens. Rink did not have a ready answer to Westgate’s concern about the city’s ability to finance the cost of cash relief, and neither did any of the others who spoke in favour of it. As finally approved, the motion authorizing payment of grocery relief in cash did contain the qualifying phrase “as soon as possible.” It carried by a single vote, with Rink, the four Labour aldermen, and G. B. Geddie of the CGA voting in favour.[64]

Deciding to make this change was one thing; implementing it proved to be another. The provincial government continued to be months behind in meeting its share of the cost of direct relief in Regina, and the city was obliged to borrow from the Bank of Montreal to cover the shortfall. Paying grocery relief in cash would have entailed more borrowing, and this was simply out of the question. At year’s end, grocery relief was still being provided in the form of vouchers.[65]

Of course Regina was not the only city that was reaching the breaking point. By 1935 there was a near-universal sentiment among Canadian cities that what they most needed was “relief from relief.” This sentiment found expression in two conferences of Canadian cities that year. The first, in Calgary in January, drew mayors and other civic representatives from the four western provinces. The second, the Dominion Conference of Mayors, was national in scope and took place in Montreal two months later. Rink represented Regina at both of them, and this afforded him an opportunity to make common cause with his fellow mayors and to draw national attention to his city’s plight. The printed proceedings of the two conferences suggest that Rink’s contribution was in each case a modest one, but he was able to add his voice to the principal demand that emanated from them: that the federal government, with its access to greater tax revenues, should assume the entire cost of relief of the unemployed.

Rink was also one of nine mayors chosen to participate in a nationwide radio broadcast at the end of the Montreal conference. In his allotted three minutes Rink succinctly summarized the impact that drought and record low wheat prices had had on the economy of Saskatchewan’s largest city and on its finances. “The cost of unemployment relief has become a burden greater than our municipality can bear,” he told Canadians. The nation’s mayors collectively tried to make the same point when they met with the federal Cabinet at the conclusion of the Dominion Conference of Mayors, but their argument fell on deaf ears.[66]

Mayor Rink found himself (and his city) in the national spotlight again in mid-June, when the On-to-Ottawa Trek reached Regina.

The story of the Trek is a familiar one. It was born out of discontent in the work camps that R. B. Bennett’s federal government had established for single unemployed men in 1932. Determined to publicize their plight, the Communist-dominated Relief Camp Workers’ Union (RCWU) had first organized a strike in Vancouver in April 1935. The actions of the relief camp strikers sometimes led to confrontations and violence. The men became fond of marching four abreast in “snake parades” through downtown streets and into department stores, including the Hudson’s Bay Company’s store. In this instance the Vancouver city police attempted to evict them and a brief scuffle ensued. When a large crowd of strikers and onlookers gathered outside, Mayor Gerald McGeer was obliged to read the Riot Act and order them to disperse. There was another confrontation three weeks later when McGeer refused to provide relief: the strikers briefly occupied the Vancouver City Museum until he relented.

These protests evoked no response from R. B. Bennett, so it was decided to confront the prime minister directly in Ottawa. A thousand men left Vancouver atop CPR freight trains in early June; their numbers grew to 1,400 by the time Bennett ordered the Trek halted in Regina on 14 June.[67]

Cornelius Rink was initially hostile to the Trekkers. They had barely left Vancouver when Rink issued a blunt warning: “They had better keep away from here if they figure the city is going to feed them and look after them while they are here . . . We are having enough difficulty looking after our own people without feeding a bunch from some other province.”[68] But once the Trekkers arrived in Regina, Rink had little more to say. On the one hand this may seem surprising. Having been twice elected mayor on promises to help the unemployed, one might presume that he would have had sympathy for the plight of these young men bound for Ottawa. But as for their leaders, that would have been another matter. Rink certainly had little regard for the leaders of the various unemployed organizations in his own city, particularly those who were avowed Communists.

Still, the Trekkers would have to be housed and fed while they were in Regina. As early as 10 June, Rink indicated that the men could sleep in one of the buildings on the Exhibition Grounds. That same day the mayor and City Commissioner R. J. Westgate met with provincial officials to work out the details. Other meetings followed with the province, with a delegation of concerned citizens (the nucleus, as it turned out, of the Citizens’ Emergency Committee) and with Arthur Evans, the Trek leader. By the time the Trek reached Regina it was agreed that the city would make Exhibition Stadium (an indoor hockey rink that was also used for livestock shows) available to the men. With a promise of reimbursement from the province, the city would also feed the Trekkers two meals a day for three days, it being anticipated at this juncture that they were determined to leave Regina in a few days, federal ban or no.[69]

Other Reginans showed a good deal more sympathy for the Trekkers. A Citizens’ Emergency Committee (CEC) was organized to see to their needs during their stay in the city. (This, it was assumed at the time, would be a weekend only, though as it turned out the Trekkers did not leave until 5 July.) As Bill Waiser has noted, the membership of the CEC was “a kind of who’s who of the city’s leading activists, including those of the radical left.” Two Labour aldermen, Alban Ellison and Clarence Fines (the latter also a key figure in the CCF by this time), took an active role in the work of the CEC, as did Peter Mikkelson, president of the RUU, and S. B. East, a United Church minister.[70]

The Trekkers were determined to continue on to Ottawa on Monday, 17 June, and looked to the CEC for help. The CEC committed itself to “do all in its power to amass public support . . . and assist the boys in boarding the train east bound,” but then one delegate raised the possibility that the CPR might not run any trains through Regina on the Monday evening. A small committee was therefore struck to ask the city and the province to co-operate in seeing that one was provided for the Trekkers. When the CEC representatives approached the mayor, they found that he was “determined to be absolutely neutral” and refused to help.[71]

Assistant Commissioner S. T. Wood—the second-highest-ranking officer in the RCMP and based in Regina—also discovered how determined Rink was to remain “absolutely neutral.” While the mayor made preparations to read the Riot Act if necessary (indeed did so, even before the RCMP formally suggested it), he refused Wood’s request to insert a civic proclamation in the newspapers on 17 June warning citizens to say away from the CPR yards if the Trekkers attempted to leave Regina. Rink’s unwillingness to do the RCMP’s bidding in this case suggests that Bill Waiser is not entirely accurate when he asserts that “the mounted police [found] a cooperative soul in Mayor Cornelius Rink.”[72]

As is well known, a confrontation was avoided, or at least postponed, by R. B. Bennett’s decision to send two Cabinet ministers to Regina to negotiate with the Trekkers.

Eight of the Trekkers subsequently travelled to Ottawa to present their grievances to the prime minister himself, but the meeting did not go well: Bennett rejected their demands outright. From this point on, the federal government began to take a harder line, pressing the Trekkers to disband and discouraging Reginans from providing further aid to them. By the end of the month the Trekkers’ funds were exhausted, and on 1 July they began negotiations with both the federal authorities and Premier Gardiner to disband the Trek. However, that evening a combined force of RCMP and Regina city police attempted to arrest the Trek leaders while they were addressing an outdoor public meeting. This precipitated what has come to be known as the Regina Riot. For nearly an hour Trekkers, Regina citizens, and the two police forces engaged in a pitched battle back and forth across the city’s Market Square. When the police finally gained the upper hand, many of the Trekkers and citizens retreated west along Eleventh Avenue into downtown Regina.[73]

As for Mayor Rink, he was a few blocks away, attending a banquet at the German-Canadian Hall. About 9:15 p.m. he walked over to the city police station and discussed with S. T. Wood and Martin Bruton (chief constable of the Regina force) whether he ought to read the copy of the Riot Act he had with him. What followed can best be described in the testimony the mayor would give before the Regina Riot Inquiry Commission six months later: “Mr. Wood thought it may be better that it be read, the Riot Act . . . The Chief [Constable] thought no, and then they discussed it. They discussed and thought maybe better not to do it, and so it was not done. We heard about, of course—even discussed about Vancouver. Vancouver—the same gentlemen, at least many of them, raised the dickens because it was read. Here they raised the dickens because it was not read. So I was damned if I did and damned if I didn’t—and so I took my proper advice.”[74]

Wood and Bruton apparently concluded that it was now too late to read the Riot Act, because the fighting had spread to several locations across downtown Regina and because there was some indication that the Trekkers were returning to the Exhibition Grounds in any event.[75]

The fighting in downtown Regina was every bit as intense as it had been on Market Square. The city police eventually had to use their firearms (twice, as a matter of fact) to disperse the rioters. By the time it was all over, a city police detective, Charles Miller, was dead and scores of policemen, Trekkers, and citizens had been injured.[76]

In the aftermath of the riot there was much criticism of the actions of the RCMP, but some Reginans thought the city police deserved more of the blame. Speakers at a CEC-sponsored rally on Market Square the following evening, and at another in Moose Jaw a few days later, directed most of their criticism at the city force.[77] The most wide-ranging critique of the behaviour of the city police came from a Regina lawyer, J. J. Stapleton. Claiming to represent “17 substantial business men of the city,” Stapleton wrote a letter to city council in which he declared,

Some thousands of eye-witnesses will be prepared to state that apparently by a pre-conceived arrangement the city police and the Mounted Police made a charge upon a meeting held under the auspices of the strikers on market square.

These witnesses will state that the police simply rushed in and started with their clubs upon the unfortunate strikers who had no means of defence. The police drove them from the square.

I personally saw the mounted police chasing running boys, presumably strikers. Then, because these unfortunate young men, after having their heads cracked and being driven through the streets like cattle, secured bricks and stones and turned at bay, your worthy police force pulled their revolvers and shot them down.

The meeting was perfectly quiet and there was no occasion for the police to interfere except that apparently they wished to cow the strikers.

It is my opinion that it is a disgrace to the city of Regina that the city police, after creating this disturbance and causing the strikers to turn upon them, should then use their firearms.

I am instructed to request and do so on my own behalf that a thorough investigation be made into this matter in order that the blame may be properly placed. I am also instructed to request that your chief of police be suspended pending this investigation.[78]

Stapleton does not appear to have had any previous connection with the Trekkers or with the CEC, and his motives (and those of the businessmen he said he represented) remain unclear.[79]

City council did consider Stapleton’s letter and his request for an investigation at a subsequent meeting. There was no question that the city police had fired at citizens and Trekkers on the night of the riot, but Bruton had insisted the next day that his men had done so only in self-defence.[80] This must have been enough for the mayor and his colleagues (even the Labour aldermen), for they discussed the matter only very briefly before deciding to take no action.[81] Stapleton does not appear to have taken his accusations to the Board of Police Commissioners, which was directly responsible for the city force, but the board did in due course hear from the chief constable. In October Bruton submitted a report detailing (and presumably justifying) the actions of his men on 1 July. While the meetings of the board were held in camera, it is possible to get a good sense of Rink’s views from the resolution he seconded, “that this Board places on record its satisfaction with the faithfulness and efficiency of the Regina City Police in the discharge of their duty under most difficult and unprecedented circumstances, as well as its regret that the price paid in injuries and hurts was so great.”[82]

Not surprisingly, the Regina Riot (and its aftermath) became an issue in the 1935 civic election campaign. When questioned at one campaign meeting why the Riot Act had not been read at Market Square, Rink replied that the “riot matter was subjudice [sic] just now with an investigation pending” and that he would have nothing to say on the matter. At another meeting someone in the audience asked, “Where were you on the night of the riot?” “I was with the chief of police [and] Colonel Wood,” Rink admitted, but beyond this he said nothing.[83]

Cornelius Rink did not win a third term. In a major political upset, Labour candidate Alban C. Ellison easily defeated Rink and four others in the mayoralty contest, and the Civic Labour League (CLL) won a majority of the aldermanic seats as well.

In accounting for Rink’s defeat in 1935, the conclusions that John Taylor draws about the fate of populist mayors across the nation in the 1930s are a useful starting point. These mayors “lacked the sort of power base to make good on their promises . . . The cities were statutory creatures of the provincial and federal governments. As mayors, they shared power with a council that was often antagonistic and full of rivals. And the Charismatic mayors could rarely win the whole of their cities. There were always the stubborn hold-outs of Convention and Socialism awaiting the opportunity to counter-attack.”[84]

Before the First World War, and again in the early 1930s, Rink had posed as the champion of Regina’s “outsiders”—those who lived in the working-class and immigrant neighbourhoods east and north of the downtown core. In 1933, when he had first won the mayoralty, Rink seemed a fresh alternative to the more orthodox members of Regina’s business elite who had for so long monopolized the city’s highest elected office. Two years later, “Rockpile Rink” was the incumbent with a record to defend, and an unpopular one at that. He had promised to substitute cash for relief vouchers and to provide work for Regina’s unemployed, but had not been able to do so. Rink had only partly fulfilled his pledge to cut taxes: the mayor and his CGA and Labour colleagues did manage to reduce the city’s share of the mill rate from 26.4 in 1933 to 25.4 in 1934, but in 1935 they were obliged to raise it to 27.4— the highest the mill rate had ever been in the city’s history.[85] As for Rink’s promise to reduce the interest payable on the city’s debentures, such a drastic step would never have gained the support of his CGA colleagues on city council, so he never brought it up.

For its part, Labour chose a candidate with a strong following in the city when it decided to contest the mayoralty for the first time in 1935. An English-born lawyer and war veteran (and a founding member of the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve unit in Regina), Ellison had already served on city council for three years.[86]

Ellison and the CLL also presented voters with a comprehensive platform, pledging to completely reform the relief system, restore the cuts in civic salaries that had been imposed earlier in the Depression, and inaugurate a “work and wages” program and a housing rehabilitation scheme. Rink appealed to voters to preserve the status quo. “Don’t throw away your old shoes,” he appealed to one audience late in the campaign. “Hang onto them and you’ll be comfortable.”[87] Reginans ignored Rink and voted for change.

The extent of voters’ disenchantment with Rink, and their desire for change, can be seen most readily by examining the results on a ward-by-ward basis. (Reginans had voted in 1934 to divide the city into wards again for subsequent municipal elections.) The ward boundaries adopted for the 1935 election again roughly conformed to the existing class and ethnic divisions within the city. Ellison won Wards 1, 3, and 4 handily; in the two previous elections Cornelius Rink had polled the most votes there. Rink was victorious in Ward 2 (where he had also done well in 1933 and 1934), but only by a narrow margin. Charles Dixon, the stronger of the two traditional “business” candidates in the field, carried Ward 5 (see figure 3).

Voter dissatisfaction and a desire for change also help to explain the outcome of the aldermanic contest: three incumbents were defeated and Labour captured a majority of the seats on city council. Other factors also contributed to Labour’s success, however. Thanks to the configuration of the ward boundaries, the CLL was able to concentrate its efforts in those neighbourhoods where Labour had traditionally done well. The CLL made a clean sweep in Wards 1 and 3 and elected one alderman in each of Wards 2 and 4. Conversely the ward system forced three incumbents opposed to Labour into the same ward—Ward 5.

Labour was also better organized than either Rink or the CGA. On the eve of the election the CLL created five new ward-based political organizations to get out the vote and a Central Labour Council to draft a platform and conduct Labour’s overall campaign. Rink’s campaign organization was more informal, and the CGA inexplicably decided to disband with the advent of the ward system.[88]

Regina voters’ decisive rejection of Cornelius Rink did not mark the end of his political career. He was soon campaigning again, this time to fill one of the aldermanic seats made vacant by the unseating of two of the CLL alderman elected in 1935. Rink chose to run in Ward 3 (figure 3) but lost decisively to Rev. S. B. East, who had come to prominence during the Trekkers’ stay in Regina the previous summer.[89]

Figure 3

Wards, 1935–1936

Then in the fall of 1936 Rink ran again for mayor. Initially he entered the field as an independent but then was endorsed by the Regina Homeowners’ and Taxpayers’ Association (which had been founded earlier in the year). Why Rink would accept the endorsement of many of the same businessmen whose policies he had opposed throughout his long political career is difficult to comprehend. No less so was RHOTA’s willingness to endorse someone whom local businessmen had on two occasions regarded as such an unsuitable mayoralty candidate that they sought to narrow the field to prevent his election. Rink had nothing to say publicly about this strange turn of events, but one of the founders of the RHOTA (prominent local lawyer D. J. Thom) declared that Rink was “a better man now than he was a number of years ago” and would make a good mayor for the city. The voters did not agree: they gave Mayor Alban Ellison a second term; Rink finished a close third (in a field of three) but did not carry a single ward.[90] When Rink ran for an aldermanic seat in 1937 (as an independent), voters rejected him much more decisively.[91]

Then there was another foray into provincial politics, this time with Social Credit. When it was that Rink first took an interest in Social Credit is as difficult to determine as when he ceased to be a Conservative. Rink was still active in the Conservative Party as late as 1933. (He attended its provincial convention in Saskatoon that year.) By 1938 he was being considered as a possible Social Credit candidate to contest the Regina seat in the upcoming provincial election. Rink was not nominated, as it turned out, but he was active behind the scenes during the campaign. And immediately after the election he approached William Aberhart about becoming an organizer for the party.[92] It is not clear if anything came of this, but Rink was nominated as the Social Credit candidate in a by-election in Regina at year’s end. The “pepper pot of many a Regina civic election” as the Leader-Post labelled him, finished dead last in a field of five.[93] Cornelius Rink would never seek public office again.

What conclusions can be drawn about Cornelius Rink’s long and colourful career in municipal politics? To what extent can he be labelled a populist? Populist is a slippery term, and determining whether the label fits depends on how one defines it. Rink was a “populist” in the sense that he was (like Vancouver Mayor Louis Taylor) “a classic outsider who was disdained by the elites.” Prior to the First World War, and again in the early years of the Depression, Rink’s appeal was strongest among Regina’s immigrant and working-class voters who were themselves largely outsiders when it came to the governance of their city (at least until 1933). Rink’s victories in the 1933 and 1934 mayoralty elections were the high point in his political career, but he was not able to command the support of a majority of his city council colleagues. And in his second term what he did (or did not) do on 1 July antagonized at least some of those who had voted for him in the past.

The 1935 election demonstrated that Rink did not have a monopoly on the votes of immigrant and working-class Reginans. Social democrats and trade unionists with an attractive platform and a superior organization could win the mayoralty and a majority of the seats on city council with those same votes and more in 1935. It was also to Labour’s advantage that it did not run a candidate for mayor until later in the Depression, after the Regina’s traditional political leaders (drawn from the business community) and the “populist” Rink had failed to ameliorate the worst effects of the Depression. Cornelius Rink might have become Regina’s first populist mayor, but as it turned out he would be its only one.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my appreciation to the anonymous reviewers of the UrbanHistory Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine whose comments and suggestions have made this a stronger article. I am also grateful to my University of Regina colleagues Thomas Bredohl, Klaus Burmeister, and Bruce Plouffe, and Julia Hartman (at the time a student in the Department of International Languages) for their assistance in identifying and translating relevant articles in the Saskatchewan Courier and its successor, Der Courier und der Herold, so that I could better understand how Regina’s substantial German community viewed Cornelius Rink and the nature of his appeal to them at election time.

Biographical note

J. William Brennan teaches western Canadian history and prairie urban history at the University of Regina. His publications include Regina: An Illustrated History (1989) and articles on provincial and Regina city politics, and on the beautification of the grounds surrounding the Legislative Building in Saskatchewan’s capital city.

Notes

-

[1]

See, for example, J. H. Thompson and A. Seager, Canada, 1922–1939: Decades of Discord (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985), in most respects still the best scholarly account of the nation’s history during the Great Depression.

-

[2]

The literature on the Great Depression’s impact on municipal politics in Canada is thin. There are few biographies of Depression-era mayors. The most useful for comparative purposes are D. Francis, L. D.: Mayor Louis Taylor and the Rise of Vancouver (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004); A. B. McKillop, “The Socialist as Citizen: John Queen and the Mayoralty of Winnipeg, 1935,” Transactions of the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba 3, no. 30 (1973–1974): 61–80; and D. R. Williams, Mayor Gerry: The Remarkable Gerald Grattan McGeer (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 1986). Other articles of note include J. E. Rea, “The Politics of Class: Winnipeg City Council, 1919–1945,” in The West and the Nation: Essays in Honour of W. L. Morton, ed. C. Berger and R. Cook, 232–249 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1976); A. B. Smith, “The CCF, NPA, and Civic Change: Provincial Forces behind Vancouver Politics, 1930–1940,” BC Studies 53 (Spring 1982): 45–65; J. H. Taylor, “Mayors à La Mancha: An Aspect of Depression Leadership in Canadian Cities,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine (hereafter UHR) 9, no. 3 (1981), 3–14: J. H. Taylor, “Urban Social Organization and Urban Discontent: The 1930s,” in Western Perspectives 1, ed. D. J. Bercuson, 33–44 (Toronto: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1974); and P. Tennant, “Vancouver City Politics, 1929–1980,” BC Studies 46 (Summer 1980): 3–27.

-

[3]

Francis, L.D., 197–198.

-

[4]

Williams, Mayor Gerry, 15, 137.

-

[5]

Taylor, “Urban Social Organization,” 33.

-

[6]

Ibid.; “Mayors à La Mancha,” 8–9.

-

[7]

There is a brief survey of municipal politics in Regina during the Great Depression in J. W. Brennan, Regina: An Illustrated History (Toronto: James Lorimer and the Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1989), 135–145.

-

[8]

Ibid., 63–66, tables V, VIII.

-

[9]

On the early history of the labour movement in Regina, see W. J. C. Cherwinski, “Organized Labour in Saskatchewan: The TLC Years, 1905–1945” (PhD diss., University of Alberta, 1971), chap. 1; and J. Warren and K. Carlisle, On the Side of the People: A History of Labour in Saskatchewan (Regina: Coteau Books, 2005), chap. 3.

-

[10]

Brennan, Regina, 71–83, 126. Any description of the ethnic and class characteristics of Regina’s various neighbourhoods must admittedly be impressionistic. Detailed census data are not available for Regina of the sort that J. H. Taylor was able to use (Housing Atlases based on the 1941 Census of Canada) in his analysis of the social morphology of Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Vancouver in “Urban Social Organization and Urban Discontent: the 1930s.” Jean Barman used similar census data in “Neighbourhood and Community in Interwar Vancouver: Residential Differentiation and Civic Voting Behaviour,” BC Studies 69–70 (Spring–Summer 1986): 97–141. Her study examines voting patterns in Vancouver school board elections, not the contests for the mayoralty and aldermanic seats.

-

[11]

Only men (and unmarried women and widows) who owned property assessed at a value of at least $200 on the town’s last revised assessment roll were eligible to vote; candidates for alderman or mayor had to own property worth at least $500. These same provisions were included in the territorial ordinance incorporating Regina as a city in 1903, in Regina’s special charter enacted by the Saskatchewan Legislature in 1906, and in the province’s omnibus City Act, which replaced it in 1908. A 1912 amendment to the City Act reduced the property qualification for candidates to the same level as it was for voters ($200) (Brennan, Regina, 39–41, 84).

-

[12]

Regina Daily Province (hereafter Daily Province),12. December 1914, 11.

-

[13]

Regina Morning Leader (hereafter Morning Leader), 8 December 1914, 5.

-

[14]

Morning Leader, 9 December 1914, 12.

-

[15]

Saskatchewan Courier, 9 December 1914; J. W. Brennan, “A Populist in Municipal Politics: Cornelius Rink, 1909–1914, Prairie Forum, 20, no. 1 (1995): 63–86.

-

[16]

J. T. M. Anderson to S. F. Tolmie, 27 January 1925, 77137–77138; C. Rink to A. Meighen, 20 April 1925, 68970–68971, Arthur Meighen Papers, Library and Archives Canada (hereafter LAC); F. W. Turnbull to R. B. Bennett, 24 October 1927, 44051–44054, R. B. Bennett Papers, LAC; Regina Daily Star (hereafter Daily Star), 1 June 1929, 15; 4 June 1929, 5; file 5996, Department of the Provincial Secretary Defunct Company Files, Saskatchewan Archives Board (hereafter SAB). On the revival of the Conservative Party in the late 1920s, its victory in 1929, and the creation of the Co-operative Government see P. Kyba, “J. T. M. Anderson,” in Saskatchewan Premiers of the Twentieth Century, ed. G. L. Barnhart, 110–122 (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 2004).

-

[17]

Morning Leader, 14 December 1915, 1.

-

[18]

Warren and Carlisle, On the Side of the People, 63. In 1915 the vote was extended to all men and women who either met the minimum property qualification (still fixed at $200) or paid at least $100 annually in rent. The qualifications would be further relaxed in 1917; henceforth any resident who paid at least $10 in licence fees could vote. In 1920 the $200 minimum for property owners would be dropped altogether (Brennan, Regina, 206).

-

[19]

W. D. Young, “M. J. Coldwell: The Making of a Social Democrat,” Journal of Canadian Studies 9, no. 3 (1974), 51–60; Cherwinski, “Organized Labour,” 258–259; C. M. Fines, “The Impossible Dream: An Account of People and Events Leading to the First CCF Government, Saskatchewan, 1944” (unpublished memoirs, 1982), 48–53. In 1931 the Independent Labour Party was succeeded by the Co-operative Labour Party, which in 1934 gave way to the Civic Labour League.

-

[20]

Brennan, Regina, table XI; Seventh Census of Canada, 1931, VI, 1268.

-

[21]

City Council Minutes, 25 September 1931, 6 October 1931, City of Regina Archives (hereafter CORA); J. M. Pitsula, “The Mixed Social Economy of Unemployment Relief in Regina during the 1930s,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 15 (2004): 100–108.

1930. The relief policies of successive city councils in Regina were not markedly different from those adopted by other Saskatchewan and prairie cities during the 1930s, as can be seen from a perusal of the relevant published and unpublished literature. This literature includes M. R. Goeres, “Disorder, Dependency, and Fiscal Responsibility: Unemployment Relief in Winnipeg, 1907–1942” (MA thesis, University of Manitoba, 1981); T. Healy, “Engendering Resistance: Women Respond to Relief in Saskatoon, 1930–1932,” in “Other” Voices: Historical Essays on Saskatchewan Women, ed. D. De Brou and Aileen Moffatt, 94–115 (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 1995); D. Kerr and S. Hanson, Saskatoon: The First Half-Century (Edmonton: NeWest Press, 1982); A. Lawton, “Relief Administration in Saskatoon during the Depression,” Saskatchewan History 22, no. 2 (1969): 41–59; and E. J. Strikwerda, “From Short-Term Emergency to Long-Term Crisis: Public Works Projects in Saskatoon, 1929–1932,” Prairie Forum 26, no. 2 (2001): 169–186. Comparative studies are still rare, as are scholarly works that examine these policies from the perspective of those who were receiving relief. For these reasons, L. Campbell, Respectable Citizens: Gender, Family and Unemployment in Ontario’s Great Depression (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), is a path-breaking study. Campbell undertakes a detailed examination of the material difficulties and survival strategies faced by families struggling with poverty and unemployment, and analyzes how individual protest and grassroots organization helped to redefine the meaning of welfare.

-

[22]

Toronto Worker, 7 June 1930, 2; Regina Leader-Post (hereafter Leader-Post), 5 June 1930, 10;22. November 1930, 18; 27 November 1930, 5; City Council Minutes, 2 December 1930, CORA.

-

[23]

Daily Star, 2 May 1931, 1, 7; Worker, 9 May 1931, 3–4.

-

[24]

Daily Star, 4 September 1931, 1; 7 November 1931, 2.

-

[25]

Daily Star, 2 October 1931, 1, 5; 21 October 1931, 1, 5; City Council Minutes, 27 October 1931, 1, December 1931, CORA.

-

[25]

Daily Star, 10 November 1931, 1, 2; 14 November 1931, 9; Leader-Post, 23 November 1931, 3.

-

[27]

Daily Star, 5 November 1931, 9; 24 November 1931, 5; Der Courier und der Herold (hereafter Der Courier), 18 November 1931, 7–8; Leader-Post, 5 November 1931, 3.

-

[28]

D. J. Thom to mayor and aldermen, 26 January 1932, file 4002(a), City Clerk’s Records, CORA ; City Council Minutes, 15 March 1932, 19 May 1932, CORA; Daily Star, 12 February 1932, 9; 11 March 1932, 3.

-

[29]

Daily Star, 12 February 1932, 9; 4 March 1932, 5; 5 October 1932, 2.

-

[30]

Leader-Post, 14 November 1932, 10.

-

[31]

Daily Star, 16 November 1932, 9; 24 November 1932, 7; Leader-Post, 23 November 1932, 8.

-

[32]

Daily Star, 23 November 1932, 3; 26 November 1932, 7; Leader-Post, 23 November 1932,14.

-

[33]

Leader-Post, 23 November 1932, 4.

-

[34]

Daily Star, 24 November 1932, 7; Leader-Post, 25 November 1932, 3. This was not the first time that a Regina newspaper had taken dead aim at Cornelius Rink’s candidacy. After the First World War, Rink left Regina for a time to engage in real estate in New Westminster, British Columbia. While there, he twice found himself before the courts. In January 1923 he was convicted of assault (and fined $20); two months later he was convicted of “creating a disturbance” and sentenced to a month in jail. When Rink returned to Regina and ran for a city council seat that fall, the Daily Post published the details of his second conviction and his one-month jail term, and declared him unfit to be an alderman. Rink finished fourth in a field of seven that year but was elected to city council in 1924 (New Westminster Police Court Record Books, pp. 395, 404, vol. 8, British Columbia Archives; New Westminster British Columbian, 30 January 1923, 1; 3 March 1923, 1; Vancouver Daily Province, 3 March 1923, 22; Regina Daily Post, 4 December 1923, 4; 5 December 1923, 4).

-

[35]

Daily Star, 31 October 1932, 9; 1 November 1932, 16; 5 November 1932, 2; 19 November 1932, 9.

-

[36]

Daily Star, 23 November 1932, 9.

-

[37]

Daily Star, 26 November 1932, 11, 17; Leader-Post, 24 November 1932, 3.

-

[38]

Daily Star, 29 November 1932, 1–2; 30 November 1932, 9; Leader-Post, 12 December 1932, 1. Rink actually carried more polling subdivisions than either McAra or Dixon. To the four he had won in 1931 (Polling Subdivisions 2, 3, 4, and 6), Rink added six more in 1932, all of them east, north, and west of the downtown core (Polling Subdivisions 1, 14–17, and 19). McAra carried nine, all but two of which were south of the Canadian Pacific Railway main line; Dixon carried Polling Subdivision 5 (figure 2).

-

[39]

Daily Star, 24 October 1933, 1, 7; 27 October 1933, 9; Leader-Post, 26 October 1933, 1–2; 4 November 1933, 2.

-

[40]

Leader-Post, 18 November 1933, 3.

-

[41]

Mayor James McAra to City Council, 31 August 1933, file 4106(d), City Clerk’s Records, CORA; Leader-Post, 1 September 1933, 1–2; 23 November 1933, 11.

-

[42]

Daily Star, 25 November 1933, 6; Leader-Post, 25 November 1933, 9.

-

[43]

Leader-Post, 28 October 1933, 4; 25 November 1933 4; 28 November 1933, 4.

-

[44]

Daily Star, 5 October 1933, 1.

-

[45]

City Council Minutes, 17 January 1933, 23 February 1933, 27 February 1933, 2 March 1933, CORA.

-

[46]

To categorize Rink as a small businessman is not to disparage him, but only to state the obvious. His successive real estate ventures were modest and short-lived, and so was Beer Bottle Dealers Limited. Cornelius Rink’s role as a collector of beer bottles ended in 1934, when the breweries took over responsibility for this work. Beer Bottle Dealers Limited would be wound up in 1935. (Daily Star, 17 October 1934, 1; Leader-Post, 18 October 1934, 3; Registrar of Joint Stock Companies to Beer Bottle Dealers Ltd, 26 March 1935, file 5996, Department of the Provincial Secretary Defunct Company Files, SAB.)

-

[47]

Daily Star, 2 December 1933, 9; Leader-Post, 28 November 1933, 1.

-

[48]

Minutes of subcommittee, 13 February 1934, file 4210(a), City Clerk’s Records, CORA; Daily Star, 15 February 1934, 1.

-

[49]

Regina Union of Unemployed to city clerk, 1 March 1934; Workers’ Protective Association to mayor and city councillors, 6 March 1934, file 4210(b), City Clerk’s Records, CORA.

-

[50]

Daily Star, 17 February 1934, 1, 3. Presumably the sobriquet “Rockpile Rink” referred to the fact that the mayor had ordered relief recipients to clear city streets. The scheme lasted only a few days, as it turned out (ibid., 2 March 1934, 1, 13.)

-

[51]

“We the Unemployed” to Mayor Rink, n.d., file 4231(a), City Clerk’s Records, CORA. George Lenhard was a city police constable who was murdered while patrolling his beat in Regina’s Warehouse District in 1933 (Leader-Post, 7 August 1933, 3).

-

[52]

Daily Star, 16 February 1934, 1; Leader-Post, 19 February 1934, 3.

-

[53]

Daily Star, 27 February 1934, 1, 3, 9; Leader-Post, 28 February 1934, 3, 5.

-

[54]

City Council Minutes, 6 March 1934, CORA; Daily Star, 31 May 1934, 3.

-

[55]

City Council Minutes, 24 July 1934; memorandum re interview with Premier Gardiner; 27 July 1934, file 4210(c), City Clerk’s Records; R. J. M. Parker to Cornelius Rink, 27 August 1934; Thomas M. Molloy to R. J. Westgate, 30 August 1934, file 4210(d), City Clerk’s Records, CORA.

-

[56]

City Council Minutes, 4 September 1934, 18 September 1934; city commissioners to Special Committee of the Whole Council, 6, 12, 25 September 1934, file 4263(c), City Clerk’s Records, CORA; P. H. Brennan, “‘Thousands of our men are getting practically nothing at all to do’: Public Works Relief Programs in Regina and Saskatoon, 1929–1940,” UHR 21, no. 1 (1992): 40.

-

[57]

City of Regina Relief Regulations, 1934, file 4210(b), City Clerk’s Records; Regina Union of Unemployed to City Council, 16 January 1934, file 4210(a), City Clerk’s Records; City Council Minutes, 16 January 1934, CORA; Pitsula, “Mixed Social Economy,” 110–117.

-

[58]

City Council Minutes, 15 February 1934, 3 July 1934, CORA.

-

[59]