Abstracts

Abstract

This article explores the links between urban restructuring, homelessness, and collective action in Toronto in the 1980s and 1990s. In Toronto, as elsewhere, urban restructuring at this time comprised a series of interconnected political-economic and spatial shifts, including economic and occupation change, gentrification, neo-liberal welfare state reform, and urban entrepreneurialism. Jointly, these political-economic shifts were implicated in the production and consolidation of new forms of socio-spatial polarization and segregation that dramatically changed the landscape of urban poverty. One of the most visible manifestations of the uneven effects of restructuring was the emergence and consolidation of mass homelessness. This changing landscape of poverty, in turn, produced a new landscape of political activism. It is this contested landscape that I explore in this article through a focus on homelessness as a primary mobilizing issue in opposition to restructuring during this key period in Toronto’s transition into a second-tier world city. I argue that urban restructuring, homelessness, and the dynamics of collective action were linked in two important ways. First, collective advocates and activists defined the crisis of homelessness as a direct effect of urban restructuring; in this way collective action mobilized to defend the interests of homeless people was simultaneously a collective struggle to contest urban restructuring. Second, the politics of restructuring directly informed the dynamics of collective action over time, influencing their organizational, strategic, and tactical dimensions.

Résumé

Cet article explore les liens entre la restructuration urbaine, l’itinérance et l’action sociale à Toronto durant les années 1980 et 1990. À Toronto, comme ailleurs à cette époque, la restructuration urbaine allait de pair avec une série de changements politico- économiques et spatiaux inter-reliés, incluant des changements économiques et professionnels, la gentrification, des réformes liées à la gestion néolibérale et des changements dans la mentalité urbaine d’entreprenariat. L’ensemble de ces transformations ont joué un rôle dans la production et la consolidation de nouvelles formes de polarisation socio-spatiale et de ségrégation qui ont fortement marqué le portait de la pauvreté urbaine. L’une des manifestations les plus évidentes des effets d’inégalité de la restructuration a été l’émergence et la consolidation de l’itinérance à un niveau important. Cette transformation de la pauvreté a par la suite entraîné des changements dans les tendances de l’activisme politique. Ce sont ces transformations de l’activisme politique que cet article explore, en se concentrant sur l’itinérance en tant que moteur fondamental de la mobilisation et de la résistance à la restructuration urbaine durant cette période importante pendant laquelle Toronto devenait une ville de deuxième rang international. On avance donc que la restructuration urbaine, l’itinérance et les tendances de l’action sociale sont inter-reliées de deux principales façons. Premièrement, les représentants et les militants de l’action sociale ont défini la crise de l’itinérance comme un effet direct de la restructuration urbaine ; ainsi l’action collective, en se mobilisation pour la défense des itinérants, consistait également en un mouvement de contestation de la restructuration urbaine. Deuxièmement, avec le temps, les politiques de restructuration ont déterminé les tendances de l’action sociale, en influençant leur organisation, leurs stratégies et les aspects tactiques de leur action.

Article body

Introduction

It was 9 September 1999, the opening night gala of the Toronto International Film Festival, a cornerstone of Toronto’s growing global entertainment and tourist economy. The red carpet was laid, the celebrities were arriving, and the media were present; so too were the protesters. Chanting, “The films may be nice but the homeless pay the price,” the Ontario Coalition against Poverty (OCAP) created a small spectacle panhandling amused guests and stargazers and forcing Hollywood stars to enter through the back door. A poster promoting the action warned, “If the Municipal Government continues ignoring and worsening homelessness it will have to reckon with what it fears most, large numbers of angry and loud homeless people getting in the way of Toronto’s tourist and entertainment industry. Come out and join us . . . to send a clear message to the easily frightened rich and famous at the Film Festival’s exclusive gala: Toronto’s homeless will not be driven out of the downtown, they will FIGHT until the city meets their demands.”[1]

The action at the film festival was the second demonstration in OCAP’s fall Campaign of Economic Disruption that targeted “posh downtown hotels, movie shoots, trendy restaurants, high-priced stage theatres, large conventions & banquets and other establishments known to make more of a buck when homelessness is made invisible.”[2] The campaign aimed to call attention to the homeless crisis that was escalating amidst the city’s wealth and to highlight the uneven effects of urban restructuring that were changing the landscape of poverty in the city: economic and occupational change, gentrification, neo-liberal welfare state reform, and urban entrepreneurialism.

OCAP’s way of framing the critique was perhaps more radical, and their tactics more confrontational, than other anti-homeless advocates and activists at this time, but OCAP was not alone in making the connections between homelessness and urban restructuring in their demands for change. For a brief moment in the late 1990s the issue of homelessness brought together an unlikely amalgam of advocates and activists and successfully mobilized unprecedented numbers of Torontonians for collective action. The protest at the film festival was an example of how collective action mobilized against homelessness and defended the interests of homeless people was simultaneously a collective struggle to contest urban restructuring.

In order to understand where this moment came from, we need to locate it within a historical context of over twenty years of anti-poverty activism amidst urban restructuring. The foundation for collective action in the late 1990s was laid a decade earlier, when a first wave of collective advocacy and activism was mobilized in response to the emergence of a novel homeless crisis, prompted by the escalation of street homelessness—rough sleeping—on a global scale. The struggle against homelessness and urban restructuring, I argue, was a dual struggle that had been waged by anti-poverty activists in Toronto, intermittently, for over twenty years. This article explores the twists and turns of advocacy and activism in one global homeless hotspot during this defining period in Toronto’s transition into a global city.

In the next section I provide a brief sketch of contemporary urban restructuring and the emergence of homelessness as a global social problem, and outline the central argument of the article. There follows a detailed examination of the relationships between urban restructuring, homelessness, and collective action in Toronto in the 1980s and 1990s. For each decade under examination I first chart the related dynamics of urban restructuring and homelessness, and then turn to an analysis of advocacy and activism.

Urban Restructuring and the Production of Homelessness

In the 1980s, the definition of homelessness underwent a conceptual—and practical—transformation in the advanced capitalist countries of the world. Although always a source of contestation, between the 1950s and 1970s “the homeless” were routinely identified in the scholarly and political spheres as individuals, typically male, who displayed certain behavioural and social characteristics—disaffiliation, transience, and poverty—and who resided in specific geographic spaces of the city known as skid row; it was these characteristics, and not a literal lack of housing, that defined who was homeless.[3] Only when a growing number of individuals began to lose their housing in the 1980s, giving rise to an escalation of street homelessness, did “the homeless” become conventionally and narrowly redefined in terms of their housing status—as the un-housed.[4] The escalation of homelessness—houselessness—in the 1980s was a global social problem that induced widespread popular, academic, and political concern, prompting the United Nations to extend its International Year of Shelter for the Homeless to focus not just on homelessness in “developing” countries, as initially envisaged in 1981, but on homelessness in the “developed” nations of the world as well.[5]

The reasons for the emergence and consolidation of a novel homeless problem in the 1980s and 1990s were varied and in some places hotly debated.[6] Some analysts, politicians, and advocates pointed to individual circumstances as the primary cause of homelessness, such as mental illness, substance addiction, spousal abuse, and familial breakdown. However, these individual factors alone were not responsible for homelessness, even if they did make some individuals more vulnerable than others to becoming de-housed. Interacting with and over- determining each of these individual factors were structural factors that Hulchanski has referred to as homeless-making processes—“human-made” processes that caused many individuals previously at risk of becoming homeless to actually lose their housing.[7] Several of the homeless-making processes he identifies are key elements of what I refer to as urban restructuring.

The concept restructuring became popular in the 1980s to describe several political-economic and spatial transformations that began to occur in the global urban system in the late 1960s, “part of a worldwide process of structural change in the organization of capital and labor.”[8] In this article I focus on four elements of urban restructuring that are most relevant for understanding the “homeless-making” effects of this transformation:

-

Economic and occupational change, notably the transition to a post-Fordist economy, characterized by a relative loss of employment in manufacturing and increases in lower- level service positions, unemployment, and (in more prosperous cities) professional occupations.[9]

-

Gentrification—“the movement of middle-class households into lower-income and sometimes deteriorating inner city neighbourhoods,” inducing a dramatic loss of low-income housing stock.[10]

-

Neo-liberal welfare state reform, involving the reassertion of market logics and market-based institutions in contemporary governing practices, including the reduction, elimination, and downloading of state-provided social services, with affordable housing and social assistance of particular relevance.[11]

-

Urban entrepreneurialism, as municipal governments adopted more fully “characteristics once distinctive to the private sector—risk-taking, inventiveness, promotion and profit motivation,” which came in conflict with, and took priority over, their function as managers of local services.[12]

Urban restructuring has taken different forms in different places,[13] yet the global dynamics of urban restructuring have been widely implicated in the production and consolidation of what Wacquant has described as a new regime of “urban marginality,” characterized by increasing income inequality, deepening poverty, and new forms of socio-spatial polarization and segregation that have dramatically changed the landscape of urban environments.[14] It is a transformation that is by no means complete. The emergence and consolidation of mass street homelessness in the 1980s was the most visible manifestation of these changes in cities of the Global North. This changing landscape, in turn, produced a new landscape of political activism, the proliferation of collective action against homelessness in and across American cities in the 1980s being one significant example.[15] It is this contested landscape of urban restructuring that I explore in this article through a focus on homelessness as a primary mobilizing issue in opposition to restructuring in Toronto, one global homeless hotspot. I demonstrate that urban restructuring, homelessness, and the dynamics of collective action in Toronto were linked in two specific and important ways.

First, from the outset of the crisis in Toronto in the early 1980s, anti-poverty advocates and activists very much defined and politicized homelessness in structural terms, as a direct effect of urban restructuring. In the 1980s activists focused on increased unemployment, weaknesses of social welfare programs, urban entrepreneurialism, and the loss of affordable housing that resulted from government cuts, gentrification, and the unwillingness of private developers to build affordable housing. In the 1990s advocates and activists remained focused on many of these same issues, but their critiques of neo-liberal welfare state reform and urban entrepreneurialism became more pointed and were extended to include the punitive treatment of homeless people. These frames clearly identified some of the critical changes occurring in the Canadian urban political economy that were inducing a rise in homelessness and creating a more hostile environment for homeless people. Throughout both decades the more radical elements of the movement extended the critique from a focus on the policies and practices associated with urban restructuring to the political and economic systems in which these policies and practices were embedded, voicing a vision of a different kind of city and a demand for fundamental systemic change. In these ways, collective action in response to homelessness in Toronto was simultaneously a collective critique of urban restructuring.

Second, the politics of urban restructuring directly informed the organization and mobilization of collective action strategies and tactics. The selective manner in which neo-liberal strategies were deployed by the state, and the impact of these political choices on the homeless problem, influenced the formation of alliances, movement demands and tactics, and the possibilities for programmatic gains. During the 1980s, incipient neo-liberalization in Canada was balanced against a continued commitment to state intervention, especially at the provincial and municipal levels of governance.[16] Many advocates and activists in Toronto took advantage of this still “sympathetic”[17] political context to mobilize collectively from within a growing number of religious- and community-based institutions and agencies and to lobby for long-term solutions to homelessness, principally and most successfully by demanding “housing not hostels.” By the late 1990s, by contrast, the political landscape for collective action in Toronto had radically changed. In a context of a dramatic rise in visible homelessness and a more hostile and polarized political and economic climate, advocates and activists were compelled to organize outside the system of social services, contentious tactics became more popular, the demand for housing not hostels was replaced by the more defensive and urgent demands for housing and hostels, and an end to the punitive treatment of visibly homeless people.

Homelessness and Urban Restructuring in the 1980s

In the 1980s a novel crisis of homelessness slowly emerged in Toronto as urban restructuring altered the landscape of urban poverty. For some service providers, such as the Fred Victor Mission, the emergence of a new homeless problem in the 1980s was indicated by the growing visibility of the skid row population.[18] It was more formally revealed by government statistics, which demonstrated a consistent rise in the number of individuals using homeless shelters in Toronto: from fewer than 2,000 in 1982 to around 20,000 in 1988, and then to over 26,000 in 1990.[19] The ranks of the homeless also came to include a growing population of youth, women, families, and people with disabilities—the “new homeless.”[20]

Already by the 1970s there were indications that a housing crisis was on the horizon: social assistance rates were not keeping pace with rents, the stock of privately owned affordable housing was declining, and the length of time individuals were staying in hostels was increasing.[21] This burgeoning housing and homeless crisis was a result of several factors associated with global urban restructuring. As in other advanced capitalist cities, from the 1960s Toronto began to experience an “evolutionary trend towards a post-industrial society,” characterized by the decentralization of manufacturing and an upsurge in the growth of professional employment in the downtown core—trends that continued in the 1980s, accompanied by more moderate increases in both unemployment and low-wage service employment.[22] So dramatic was this transformation that by the end of the 1970s Toronto had overtaken Montreal as the financial and business capital of the country.[23] The professionalization of the downtown core “introduced a new dimension [into] the inner city housing market,” principally in the form of gentrification, which resulted in the loss of 13,000 rental units in Toronto between 1972 and 1979. An additional 20,000 affordable units were lost in the 1980s, largely as a result of de-conversion, conversion, and demolition.[24] With a limited supply of rental units, vacancy rates remained under 1 per cent through the 1980s, well below the 2.5 per cent vacancy rate the City of Toronto now considers indicative of a “healthy” rental market.[25]

Making matters worse were several factors that mitigated against increased private investment in the affordable housing market from the 1970s: the increased cost of land in Metropolitan Toronto, more stringent by-laws governing the licensing of bachelorettes and rooming houses, and restrictive regulations governing land use—all of which made it unprofitable, if not impossible, to invest in upgrading existing and constructing new affordable rental units.[26] Moreover, during the global real estate boom of the 1980s, investment in commercial and residential real estate (condominiums) became a crucial aspect of local economic development in Toronto, championed by Mayor Art Eggleton, in office between 1982 and 1990; it was part of an incipient entrepreneurial strategy to spur post-Fordist economic growth that included plans to publicly subsidize new inner-city development projects, such as a new dome stadium, and the pursuit of mega-events, such as the Summer Olympics.[27]

In the absence of opportunities for profitable private investment in the affordable housing market, what was required instead, as suggested by a municipal report in 1974, was for the federal and provincial governments to increase their investment in non-market, subsidized housing.[28] Canadian governments might also have taken steps to better protect affordable housing stock and to maintain the purchasing power of those on low incomes. However, by the 1980s governments at all levels in Canada had embarked on incipient deficit and debt reduction and a programmatic shift in the direction of neoliberalization.

While the Progressive Conservative government in Ottawa was reticent to reduce its funding for social assistance, it commenced a sustained program of funding cuts to federal housing programs in 1984, in that year cutting $217.8 million from non-profit, rural, and native housing programs, residential rehabilitation assistance programs, and housing research programs. These were followed by further significant cuts in 1986 and 1990, notably to programs that provided financial assistance for the rehabilitation of affordable rental properties.[29] Even before that, in 1975, the Ontario Conservative government had “embarked on a coordinated policy of curbing social spending,” resulting in a real loss in purchasing power for those on social assistance.[30] Only in 1986 did social assistance rates again begin to approach the real levels of the 1970s, rates still not adequate to “meet the basic costs of food, shelter, and maintaining a household.”[31]

Nevertheless, in comparison to the United States and Britain, neo-liberalization in Canada was still in its infancy. The Ontario government was still increasing welfare rates, if inadequately, and both the federal and provincial governments remained involved in social housing. Indeed, responding to political pressure, the provincial Liberal government, in power between 1985 and 1990, funded important new affordable housing initiatives, extended eligibility for government subsidies to single individuals, and funded new outreach and support services for individuals with high support needs, including the construction and operation for the first time of supportive housing. With strong support from both the regional (Metropolitan) and municipal (City) authorities, there was a substantial growth of the non-profit housing sector between 1984 and 1993. These programmatic initiatives were complemented by measures aimed at saving existing—and encouraging the development of—new affordable housing in the private sector.[32]

None of these actions, however, stemmed the housing and homeless crisis. The provincial and Metro governments were compelled to act in an “emergency”[33] fashion, financing seventeen new homeless shelters over the decade, doubling the number of shelters in the city, many of them catering to specialized populations of new homeless groups. By 1988, the shelter system in Metro had grown to include 2,100 beds, almost at capacity every night, and continued to grow into the 1990s.[34] Even the expansion of the hostel system, however, was not sufficient for the City to gain a handle on its growing street homeless problem. The growing crisis prompted community members to take matters into their own hands: the first faith-based and volunteer-run Out of the Cold overnight winter shelter and drop-in program was created in 1988, followed by the city’s first Street Patrol by members of Toronto’s native community in 1989.

In this contradictory political and economic environment of incipient neo-liberalization, advocates and activists mobilized with, and on behalf of, homeless people to demand government action to address homelessness. They mobilized for the long-term demand of housing not hostels and in opposition to urban restructuring.

Advocacy and Activism in the 1980s

When homelessness began to increase noticeably in the early 1980s in Toronto, a small community of voluntary sector services providers was already assisting and advocating for homeless individuals. One of the best organized, and arguably the most visible and radical, homeless advocacy groups in Toronto at the beginning of the decade was the Single Displaced Persons Project (SDPP). First established unsuccessfully in 1970, the SDPP was revived on a more permanent basis in 1974 by Keith Whitney, the superintendent of the Fred Victor Mission, with the objective of responding “to the poverty, marginalization and personal problems of the men and women of the inner city who [were] at the bottom of our social and economic system.”[35] By 1982 the SDPP had grown to become a small network of directors, board members, and staff of downtown social service agencies, and clergy of downtown churches.[36]

Within the world of social service provision, the SDPP’s approach to homelessness was innovative for its time. Displacing conventional notions of individual frailty and charitable provision that dominated homeless discourse in the early 1980s, the SDPP sought to redefine homelessness as a result of economic circumstances beyond the control of individuals and to humanize the homeless industry, in part, by “enabling” and “empowering” homeless people through programmatic inclusion.[37] In this way, the SDPP had an affinity with many local anti-homeless groups in the United States, such as the Community for Creative Non-Violence and Coalition for the Homeless, both of which emphasized the economic and political dynamics at play in the production of homelessness.[38]

As the decade progressed, a rapidly growing network of advocates and activists joined the SDPP to establish a nascent anti-homelessness movement. Some of the individuals who would become central figures mobilizing poor and homeless people for collective action were already active in the unemployed workers movement and helped to create new services or found work in the growing network of drop-ins and outreach programs. These were typically housed within religious and community based institutions—such as Christian Resource Centre, All Saints Church, and Central Neighbourhood House—most of them located in the downtown eastside, Toronto’s primary skid row. Although the boards of some of these agencies were already wavering in their support—“activists consistently had to work keep agency boards on side,” suggested one former outreach worker and anti-poverty activist—these religious- and community-based institutions nevertheless operated as a space for the organization and mobilization of collective action during these years.[39] Housing and homelessness became a focal point of their anti-poverty activism, with overlapping memberships populating groups such as the Toronto Union of Unemployed Workers (TUUW), Ontario March against Poverty, BASIC Poverty Action Group, and Bread Not Circuses. Many of these people were the most outspoken critics of neo-liberalizing, and especially entrepreneurial, trends in the city. Alongside these activists also emerged a growing number of service providers and advocacy groups, established to cater to, and advocate for, the specific needs and demands of new homeless sub- populations such as young people (Covenant House Toronto), pregnant teenagers (Nellies), and psychiatric consumer survivors (Supportive Housing Coalition). This community of advocates and activists was not all of a piece; it was a diverse movement ideologically and strategically. But by the middle of the 1980s a strong voice coalesced, if loosely, around the need for housing not hostels.

Housing Not Hostels

The demand for housing not hostels was first voiced by participants in the SDPP and publicized widely in its treatise, The Case for Long-term Supportive Housing, in 1983. In a context of rapid expansion of emergency services, the SDPP quickly came to the conclusion that the starting point for solving homelessness was to make available secure, long-term, affordable housing. The prevailing strategy of expanding the emergency shelter system, the SDPP argued, was “based on the assumption that the problem consists of a short-term lack of shelter”; it was “like prescribing aspirin for cancer.” [40] Instead, blaming the economic system for the plight of homeless people, the SDPP promoted housing as a right and called for government subsidization of non-profit, supportive affordable housing.

Leading by example, as early as 1981, senior staff at the Fred Victor Mission made the decision to develop a housing strategy, as opposed to a shelter strategy. This resulted in the decision to build Fred Victor’s “Third House,” which, in turn, led to the establishment of the Homes First Society (HFS) in 1983, Toronto’s first “alternative” non-profit housing company, headed by SDPP member Bill Bosworth.[41] With financing from the Canadian Mortgage Housing Corporation, the HFS opened Canada’s first federally supported transitional housing project for single individuals the following year, paving the way for an expansion of federally funded and supported housing for single individuals.[42] More contentious perhaps was the decision by the Board of All Saints Church in 1984, at the urging its new director, Brad Lennon, to close its three-year-old Overnight Drop-In and replace it with social housing for single displaced persons. After failing to receive funding from the federal government, the project was finally granted approval from the provincial government in 1986.[43] It was the first time single individuals were made eligible for provincially funded subsidized housing.

If the SDPP’s actions generated some momentum in Toronto in support of the demand of housing not hostels, it was the “moral shock” associated with the death of Drina Joubert, a homeless woman found frozen to death in the back of a pickup truck in December 1985, that catalyzed a small movement.[44] The publicized deaths of two more individuals on Toronto streets within the next two months reinforced the urgent nature of homelessness and the failures of the hostel system amongst those working in the community.[45] After Joubert’s death was made public by Beric German, a housing outreach worker and anti-poverty activist, the Affordable Housing Not Hostels Coalition was quickly mobilized, bringing together people who lived in hostels with community workers, shelter staff, church groups, and politicians, including members of the SDPP. The objective of the coalition was to pressure the government to convene an inquest into Joubert’s death, and then to gain legal standing, publicize, and influence the outcome of the coroner’s inquiry.[46]

On the first day of the inquest, the Affordable Housing Not Hostels Coalition mobilized between 150 and 250 individuals to march to City Hall from All Saints Church.[47] The message of the coalition was clear: “10,000 people are homeless in Toronto and the government response has been inadequate! Hostels and temporary shelters compound the problem and are not viable solutions! Housing is a right, not a privilege! We need affordable housing not hostels!” [48] The coalition and other advocates repeated this message directly to the coroner’s jury in their testimony and at demonstrations each day outside the inquest.[49] Peggy Ann Walpole, executive director of Street Haven, perhaps captured the sentiments of advocates for housing not hostels most succinctly, when she stated, “In the absence of long-term housing improving or adding to the hostel system is futile and irresponsible.”[50] Walpole’s testimony was informed by the input of representatives from as many as twenty-seven agencies and programs that had women as one of their client groups.[51] Some of these advocates’ arguments were picked up by the coroner’s jury, which recommended that the shelter system be returned to its original function, to provide shelter during emergencies, in part by developing long-term housing options accessible to women in crisis. Significantly, while the jury did recommend improvements, it did not recommend a further expansion of the hostel system.[52]

In the wake of the Joubert inquest, loosely organized activists continued to pressure the government for housing not hostels. Leading the charge was the network of local activists working in and around the downtown drop-ins, hostels, and community centres associated with the TUUW, BASIC, and other groups, and which, between 1987 and 1988, organized rallies, picketed the housing minister’s office, lobbied the government for long-term housing solutions, and mobilized a small protest as often as every two weeks in the downtown eastside in opposition to gentrification and homelessness.[53] Michael Shapcott, an outreach worker at the Christian Resource Centre and a leading voice in the movement, responded to a proposed expansion of the shelter system in 1987 with a call for a freeze on hostel development. Shapcott admitted publicly that there was a need for more shelters but “at some point,” he argued, “you’ve got to bite the bullet.”[54] This is precisely what All Saints had done the previous year when it replaced its emergency shelter for single men with affordable housing; the Fred Victor Mission followed suit in 1988, replacing its short-term men’s hostel and seniors’ homes with 194 permanent, supportive and shared housing units for adults.[55]

Challenging Urban Restructuring

The demand for housing not hostels was voiced by advocates and activists on the basis that hostels were not a solution to homelessness, because the homeless problem was a direct result of changes occurring in the political economy of the city and weaknesses in the existing system of social welfare. In her brief to the Joubert inquest, for instance, Walpole concluded that women did not need more hostels. Instead, she argued, “The women I meet and get to know need three things most critically: a decent income, a decent place to live, and supports and services which are responsive to the issues in their lives.”[56] She identified several factors influencing the homeless problem, including increased unemployment, inadequate social assistance benefits, and the failure of the government to provide necessary funding for housing and for services and supports for people who had been deinstitutionalized. She also identified a desperate lack of low-income housing because, amongst other things, private developers were unwilling to build low-income housing, and conversions were displacing people on low incomes. Many of these same “pressures” and “obstacles” to providing affordable housing were identified by the Affordable Housing Action Group—a steering committee established in 1986 comprising representatives from tenants’ organizations, shelter and housing agencies, social policy organizations, and organized labour—as well as a number of service and housing providers surveyed in 1989.[57]

Some groups, such as the SDPP, the TUUW, and BASIC, at times more explicitly linked the homelessness crisis to growing wealth and inequality in the city, focusing their analyses more directly on the polarizing dynamics of contemporary urban restructuring. Defending his decision to close the Overnight Drop-In at All Saints Church, for example, Lennon explained that hostels did nothing to stop the loss of affordable housing resulting from gentrification. The same real estate boom that was displacing thousands from rooming houses was making it financially impossible to build new affordable housing.[58] In general, he suggested, the economic boom had created a mean city fuelled by personal greed.[59]

Three years earlier the SDPP had made similar claims in its treatise on housing and homelessness, attributing “the lack of appropriate, permanent, affordable housing” to “structural barriers,” including high unemployment, low welfare payments, and the dynamics of the local property market that result in housing that is “too expensive for people to rent.”[60] Referring to the dynamics of urban economics specifically, the report continued, “The disappearance of rooming houses highlights the economic factors underlying homelessness and shows how the same processes that provide housing for some deny housing to the poorest members of society. Indeed, the demands of our profit-based real estate and development industries often seem to take precedence over people’s needs for housing and meaningful community life.”[61] The SDPP’s political demands, however, did not match their radical rhetoric entirely. Instead of organizing to challenge the profit-based system they criticized, the SDPP focused their activism on promoting and developing new and innovative forms of supportive affordable housing. Thus while some members of the SDPP made the connections between “the loss of housing, the destitution of the poor, and the larger issues of capital accumulation and economic polarization,” this analysis was not fully reflected in their political demands and actions.[62]

BASIC, on the other hand, linked these developments more explicitly to political choices; in their words, they “set out to expose and challenge the corporate/political agenda that generates poverty.” They argued that poverty was a result of several factors, “including private corporations that refuse to build affordable housing, a criminally low minimum wage, a welfare system that legislated poverty, a weak government commitment to social housing, and a move by corporations to de-industrialize and shift to low-paying service-sector jobs.”[63] BASIC, and other like-minded individuals and groups, challenged the City’s plans to invest in mega-projects and host mega-events “at a time when there [were] urgent social needs crying for attention in Metro.”[64] In doing so, BASIC posed direct questions about the shift in Toronto towards entrepreneurial modes of governance and backed up their words with collective actions to counter gentrification, to highlight the uneven effects of global urban restructuring, and to contest Toronto’s global city agenda.

One example was BASIC’s “Real Toronto” campaign in 1988, highlighted by a tour of Toronto’s growing housing crisis, which was “designed to coincide with the G-7 Economic Summit, in order to counter the claim that Toronto is a ‘world class city.’”[65] By exposing poverty, hunger, homelessness, and under-housing, BASIC explained, the “tour will counter the slick and expensive government public relations campaign aimed at perpetuating the notion that the G-7 economic and political policies are producing great prosperity.”[66] Shapcott hit a similar note when he spoke on behalf of BASIC at an information picket opposing plans by the government to donate provincial land to developers to build an opera house. “No one has ever died from a lack of opera,” he said, “but there are people who have died from a lack of housing.”[67] And similar sentiments motivated members of BASIC and the Roomers’ Association to mobilize the Bread Not Circuses coalition in 1989 in opposition to Toronto’s bid to host the 1996 Summer Olympics, perhaps the most successful and enduring statement of community opposition to entrepreneurial forms of global city building.[68] In combination with the successful province-wide movement to increase welfare rates in the province between 1987 and 1989 and the unexpectedly popular mayoral campaign of anti-poverty activist Carolann Wright orchestrated by BASIC in 1988, this would be a high point of anti-poverty activism in Toronto and across Ontario.[69]

The province-wide movement for welfare reform between 1987 and 1989 led to the establishment in 1990 of the Ontario Coalition against Poverty (OCAP), a direct-action anti-poverty organization led by John Clarke, the former head of the London Union of Unemployed Workers.[70] Strategically informed by the philosophy espoused by the American scholar activists Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, OCAP’s politics have been premised on the belief that the only way that poor people can achieve concessions from the state is through disruption.[71] As the homeless crisis deepened and the political climate changed in the 1990s, OCAP would become one of the leading—if polarizing—voices in the movement against homelessness and a focal point of resistance against urban restructuring in Canada’s largest city.[72]

Homelessness and Urban Restructuring in the 1990s

The collapse of the real estate market in Toronto in 1989 marked the beginning of a deep recession that accelerated the uneven effects of post-Fordist urban development;[73] the same recession fostered the beginning of more aggressive neo-liberal reforms at both the federal and provincial levels of governance, a crucial turning point being the announcement by the federal government in 1993 that it would no longer finance any new affordable housing programs.[74] This was followed in 1995 by its decision to sharply reduce funding for social assistance, simultaneously removing many of the programmatic regulations governing the provinces’ use of these monies, and to devolve administrative responsibility for all social housing to the provinces beginning in 1996.[75] All of these initiatives, in turn, paved the way for more aggressive neo-liberalization at the provincial and municipal levels of governance, especially in the second half of the decade.

Provincially, the New Democratic Party, in power in Ontario between 1990 and 1995, initially continued to increase welfare rates and finance new non-profit housing initiatives, but by 1993–1994 it began its own program of cost-cutting reforms, freezing social assistance rates and sharply reducing social housing construction, decisions that, in combination with the federal withdrawal from social housing in 1993, were quickly followed by a noticeable spike in homelessness in Toronto.[76] It was the election of the provincial Conservative Party led by Mike Harris in May 1995, however, that marked a radical shift in governance in Ontario, predicated on a reassertion of market forces and a reduction of the role of the state in social welfare.[77] Many of the most significant changes affecting individuals and families on low incomes specifically were introduced in the Conservative government’s first year in office, including a 21.6 per cent cut to welfare rates and a freeze on all provincially financed affordable housing projects not already under construction. These changes were followed immediately by an escalation in homelessness, a trend punctuated by the freezing deaths of three homeless individuals in the span of one month in January and February 1996, giving cause for the convening of another coroner’s inquiry.[78] The City responded to the growing homeless crisis with emergency measures and created an Advisory Committee on Homeless and Socially Isolated Persons, comprising municipal and community advocates.[79] The federal and provincial governments, on the other hand, both of which had stopped funding new affordable housing initiatives entirely, ignored most of the recommendations arising from the coroner’s inquiry.[80]

Over the next several years the homeless problem deepened, even as the economy prospered and unemployment fell. The number of individuals staying in a homeless shelter rose annually from close to 26,000 in 1996 to a peak of just under 34,000 in 2001; eviction applications increased by 26 per cent between 1997 and 2000; and the number of families waiting for social housing almost doubled between 1998 and 2000 and continued to grow to a peak of 74,000 households in 2003.[81] There was also a visible proliferation of individuals sleeping rough in central areas of the city, and less visibly under bridges, in the Don Valley or, after 1998, at Tent City.[82] “Squeegee merchants”—individuals, mostly youth, who washed motorists’ windshields for money—also became a visible presence beginning in the summer of 1996.[83] And the number of known homeless people dying on the streets of Toronto increased quite dramatically after 1998, dwarfing the number of known fatalities in the late 1980s.[84]

In addition to neo-liberal welfare state reform, many of the reasons for the continued crisis of homelessness were the same as in the 1980s, linked to the uneven effects of urban restructuring, including continued post-Fordist occupational change, the further spread of gentrification, and the construction by developers of condominiums instead of rental units.[85] Overall, between 1995 and 1997 an average of just over 1,000 new rental units a year were completed in Toronto, fewer than half the average of the previous decade, and between 1998 and 2001 fewer than 400 were completed, not a single one of which was publicly subsidized.[86] Moreover, after a temporary reversal during the early 1990s, the city again experienced a net loss of rental units beginning in 1996 and the vacancy rate remained below 1 per cent between 1997 and 2001, putting upward pressure on rents and causing affordability issues for many people on low incomes.[87]

Instead of taking action to balance the unequal and by now fatal effects of urban restructuring with programmatic intervention, provincial government policies implemented in 1998 arguably deepened the crisis, by deregulating rents in vacated apartments and downloading programmatic responsibilities to the newly amalgamated City of Toronto, including the operation and maintenance of the city’s entire stock of social housing.[88] Forced to adjust to new fiscal constraints and realities, the City further consolidated its entrepreneurial approach to urban governance, especially after Mel Lastman came to office as the first mayor of the amalgamated City of Toronto in 1998.[89] Under Lastman a central concern of municipal governance became to consolidate and enhance Toronto’s position as a global city: to “promote Toronto as an investment platform, pursue large development projects such as the Olympics, and reinforce the dominant global city industries: finance, producer services, media, information technology, tourism and entertainment.”[90] In this competitive context, the municipal response to homelessness was contradictory.

On the one hand, the City responded to homelessness at times with emergency measures, declared homelessness a “national disaster,” opened new homeless shelters, took action in support of many of the recommendations of the Mayor’s Task Force on Homelessness, and lambasted both the provincial and federal governments for placing the City in a precarious financial position and for failing to build affordable housing.[91] These actions were overshadowed, however, by municipal mismanagement of the crisis, notably the City’s consistent failure to respond rapidly to open and keep open homeless shelters and Lastman’s unwillingness to meet personally with homeless advocates. Police harassment of homeless individuals also noticeably increased, a trend that was being reported in cities across North America.[92] After failed attempts by municipal councillors to pass a by-law outlawing squeegeeing in Toronto, the provincial government passed the Safe Streets Act in 1999, making it a provincial offence to panhandle “aggressively.”[93] That same summer the City established the Community Action Policing (CAP) program to enhance policing in forty “criminal hotspots”—including inner city areas where homeless people congregated.[94]

It was in this context of urban restructuring, characterized by vigorous welfare state retrenchment and entrepreneurialism, that collective action was mobilized in response to a new surge in the crisis of homelessness in the 1990s. In this aggressively neo-liberalizing political environment, advocates and activists were less able than they had been in the 1980s to organize openly and collectively in opposition to government policies from inside the structure of social services. Instead, on the defensive politically, advocates and activists created new organizational vehicles, made urgent demands for housing and hostels, and used or supported confrontational and disruptive tactics, such as squatting, picketing, and mass panhandling.

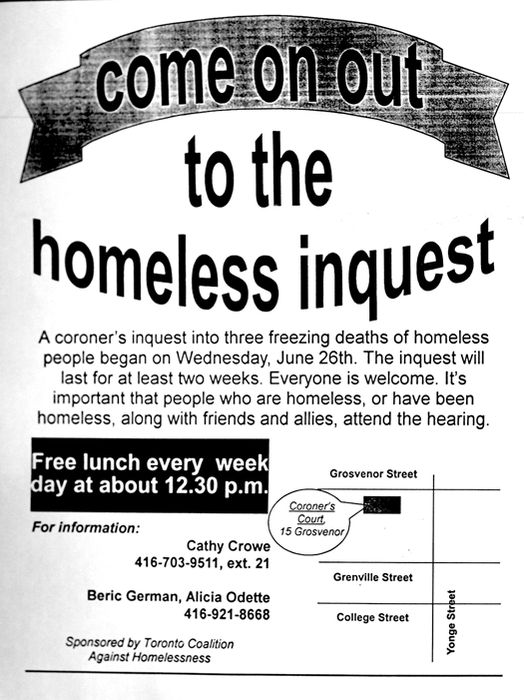

Figure 1

tcah flyer, 1996

Advocacy and Activism in the 1990s

Throughout the first half of the 1990s, anti-homeless advocacy and activism continued in Toronto, but it was muted in comparison to the second half of the 1980s, as homelessness waned as a public policy concern, especially once the total number of people seeking shelter declined, if only briefly, between 1992 and 1994.[95] This began to change in 1995 after the election of the Ontario Conservative Party, an important catalyst being the cross-community coalition movement that emerged to oppose Harris generally, and OCAP’s widely supported demonstrations against Conservative welfare policies more specifically.[96] But as in the 1980s, it was the “moral shock” induced by a cluster of homeless deaths early in 1996 that provided the immediate impetus for movement building on the homeless front.

The deaths sparked protest events by Toronto Action for Social Change (TASC), formed the previous year, and OCAP, which stormed Seaton House, the largest homeless shelter in the country, blaming the Conservative government for the deaths.[97] More enduring than these protests, though, was the decision by representatives from over two dozen frontline agencies and anti-homeless advocates and activists to form the Toronto Coalition against Homelessness (TCAH), after the government finally agreed, at the urging of homeless advocates, to convene a coroner’s inquest.[98] The model for the TCAH was the former Housing Not Hostels coalition, which had been formed in response to a similar crisis and was perceived to have achieved some important successes. This time, however, the political context had changed substantially. Not only did the TCAH have a difficult—but ultimately successful—time receiving standing at the inquest, it had little success in seeing the most important recommendations of the jury put into practice.[99] This had a marked impact on the viability of the coalition.

Unable to see the recommendations of the coroner’s jury implemented, and forced to respond to rapidly shifting and seemingly urgent issues on the homeless file, the TCAH was unable to formulate a coherent message and campaign, prompting one member to remark five months after the inquest, “What are TCAH’s priorities? Housing, police, hostels, panhandling, discharge planning . . . The TCAH is unfocused.”[100] The TCAH also suffered from internal divisions, pitting representatives from frontline agencies and non-profit housing providers against members who were less encumbered by organizational affiliations and who held a majority on the steering committee. Divisions arose over strategic and tactical issues, among them whether or not—or how closely—to align with OCAP, “whose direct-action methods some agencies might object to.”[101] Some individuals argued that an “advocacy chill” had set in amongst some social service organizations that, afraid of losing government funding, became less willing to be openly critical of the government and to support OCAP-style tactics, a political development that was in no way limited to those agencies working to support homeless people.[102] All of this led to a fracturing of the coalition. A year after the coroner’s inquest, the TCAH was in free fall, with decreasing attendance at meetings and the resignation of several agencies.[103]

The slow and acrimonious death of the TCAH was an indication that homeless advocates were without unified ideological and strategic direction, a result of several factors including the more hostile political climate in which they were trying to organize and the urgent, and constantly shifting, dynamics of the homeless crisis. But the shifting landscape of homelessness and of homeless politics also created new possibilities for mobilizing collective action outside agencies and institutions, as indicated by the surge in mobilizing support for OCAP and the establishment, in 1998, of the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC), a new political entity inspired by former TCAH member Cathy Crowe’s failed campaign to have the City declare homelessness a “disaster” earlier that year.[104] Having failed to gain institutional support for her “disaster” declaration, Crowe realized that she would “have to move outside the city structure, to organize separately, from the community.”[105] Spearheaded by Crowe, with Beric German, the TDRC took shape in the first half of 1998 and came to include on its steering committee, by invitation, individuals working in the mental health, academic, business, faith, AIDS, legal, and low-income communities.

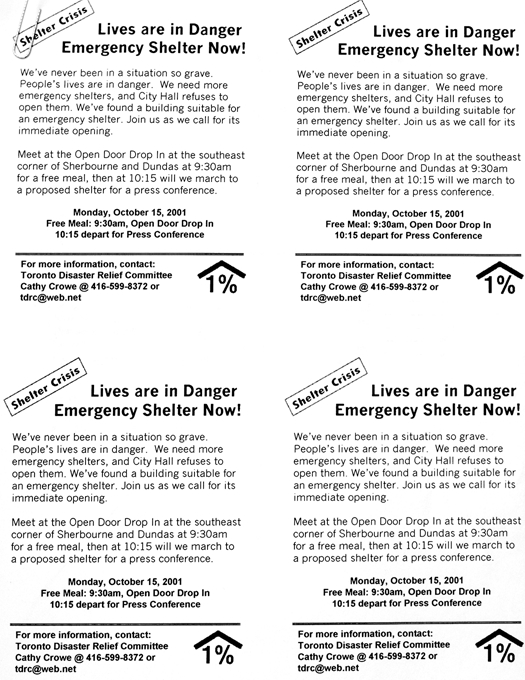

The TDRC’s signature document, Homelessness in Toronto: State of Emergency Declaration, clearly delineated the “scale of the disaster”: increasing rents, decreasing supply, no new social housing, declining social assistance rates, declining incomes of tenants, and increasing shelter use. In sharp contrast to advocates in the 1980s, however, the TDRC did not make the case for housing not hostels; instead their declaration identified a long-term need for affordable housing and an immediate need for more and better shelters.[106] The campaign to have homelessness declared a “national disaster” commenced on 8 October 1998. Three weeks later, Toronto City Council obliged, declaring homelessness a national disaster and passing a motion to pressure other governments to follow suit. Over the course of the following year as many as 400 organizations across the country would make similar declarations. The federal and provincial governments, by contrast, remained silent. The crisis continued and so did the demands for housing and hostels.

Housing and Hostels

The centrepiece of the TDRC’s long-term strategy to solve homelessness was its demand for a national housing strategy. Highlighting the fact that both federal and provincial governments had completely stopped funding new affordable housing initiatives (in 1993 and 1995 respectively), the TDRC’s goal was for governments to increase their spending on housing by 1 per cent of their combined budgets, doubling the money being spent on housing nationally—a proposal branded the “1% Solution.”[107] During the campaign for the 1% Solution—the first phase of which was rolled out nationally between 1999 and 2001—the TDRC sought to raise awareness of the scale of the homeless problem and to influence the federal government through several forms of lobbying, including a guided tour of Toronto’s homeless “disaster,” a tactic undoubtedly influenced by BASIC’s “real Toronto” tour in the 1980s.[108]

The campaign for the 1% Solution specifically, and long-term solutions for homelessness more generally, continued well into the next decade, and with some limited but important successes, including establishment by the federal government of the Homeless Partnership Initiative in December 1999.[109] But on a day-to-day basis in Toronto, more frequent, visible, and contentious were the demands to open and to keep open emergency shelters; in the current political and economic climate, and in the face of a deepening, even fatal, crisis of rough sleeping, campaigns to solve homelessness were overshadowed by the more urgent demand to manage homelessness. This was the point made by the head of the Children’s Aid Society in one of a number of letters sent to Mayor Lastman, urging him to open (and then to keep open) emergency shelters in 1999: “I appreciate . . . your vision that we need ‘homes’ not hostels. . . . However . . . we have an existing problem with homelessness and need for shelter immediately.”[110] The following month the TDRC made a similar statement to the City’s Community and Neighbourhood Services Committee (CNSC) when it requested the City make available more shelter beds: “Ultimately, our goal is a national housing policy and other long-term solutions to homelessness. However, there is an immediate need out there, created by the emergency state that the homeless exist in right now and that we can no longer ignore.”[111]

Figure 2

tdrc postcard, n.d.

The urgency of the demand for more shelter beds was reaffirmed time and again by the City’s own status reports demonstrating that capacity in shelters was well above 90 per cent, the occupancy threshold the CNSC agreed would be its target in March 1999 (when occupancy was at 95 per cent).[112] Two months after the CNSC set this target, OCAP sent a letter to the chair of the CNSC seeking clarification on the proposed closure of a shelter at the Fort York Armoury. OCAP’s own data, collected over the previous week, “clearly indicate[d] a shelter system operating above 90% occupancy and effectively packed to the rafters”; the proposed closure, in these circumstances, made it appear “that the City had no real intention of adhering to the guidelines it has set for itself.”[113] The next month OCAP would bring a proposal to the CNSC requesting approval to set up a Safe Park in Allan Gardens—guaranteeing homeless people the right to sleep safely in this park in the downtown eastside—in part because the shelters were full. Speaking to the committee in support of OCAP’s motion, and on behalf of the TDRC, Kira Heineck remarked, “We support it, but we wish we didn’t have to . . . As one member of our community so eloquently put it, ‘We used to demand housing for the homeless. They refused to build housing. Then we demanded hostels for the homeless. Now we are simply demanding a park. What next? That we demand heating grates on city streets?’”[114]

Figure 3

tdrc leaflet, 2001

Every year between 1998 and 2004 the TDRC urged its supporters to lobby the City either to stop shelters from closing or to open more shelters.[115] “Toronto is in desperate need of more shelter space immediately,” wrote one frontline volunteer in December 2001, two months after homeless advocates and supporters from the faith and labour communities campaigned for a new 200-bed shelter. “Above all, we need an increase in affordable housing, rather than just more fancy condos. But in the meantime, we need more shelter space as there are people dying on the streets.”[116] That same month, Councillor Jack Layton, on behalf of the Advisory Committee on Homeless and Socially Isolated Persons, requested the City’s Community Services Committee (CSC) open an emergency shelter at City or Metro Hall. “Front-line workers consistently report that people cannot come in out of the cold at night because our shelters are full,” reported Layton.[117] The request was rejected, despite the recognition that shelter occupancy had been over 90 per cent since May 2001.[118]

For several more years advocates were compelled to make the same urgent demands, at times prompting supporters to suggest more contentious tactics and generating increasing frustration at Lastman. The City’s failure to heed a request for an additional shelter from sixty agencies compelled one supporter to write to Cathy Crowe, “I feel that there must be a harder hitting campaign. . . . I can’t believe that the mayor has been able to refuse to meet with TDRC for years. Let’s make him meet the TDRC and initiate something for the homeless before he leaves office.”[119] Indeed, by February 2002 the TDRC had made twenty formal requests for a meeting with Mayor Lastman, all of them rejected.[120] Just over a week later, a supporter suggested the organization prepare to occupy City Hall in the case of another death.[121] “I agree, something must be done,” replied another supporter. “City Hall is unresponsive, people are at risk. Let’s get on with it!”[122]

Challenging Urban Restructuring

The conflict over shelters, according to some activists, was not just a difference of opinion about the need for more beds; it was a conflict over whose needs took precedence in Toronto—the poor and homeless versus local businesses and gentrifying residents. It was a conflict that was informed by the polarizing socio-spatial and political dynamics associated with urban restructuring. OCAP activists in particular framed the issues in these terms. Defending OCAP’s takeover of the Doctors Hospital in 1998, for example, Clarke explained to the media that OCAP and the City were embroiled in a “tactical disagreement’” over “whether the issue is to try and placate yuppie residents or stand up to them” and create a shelter.[123] The following spring, when the City forced the Salvation Army to shut down its emergency winter hostel, one OCAP activist linked the decision directly to the City’s plans to “revitalize” the area and to “drive the homeless and their services out.”[124]

Indeed, the need to “drive the homeless and their services out” was not just affecting the City’s shelter strategy, it was prompting the City to support punitive action to remove homeless people from public space as part of what OCAP called a broader “war on the poor.”[125] It was a “war” that intensified in the summer of 1999 with the creation of the Community Action Policing program, prompting advocates in the city to create the Committee to Stop Targeted Policing with the express purpose of documenting and opposing police harassment of poor people. Explaining the urgent need for people to support its Safe Park action in August 1999, OCAP stated,

Toronto is a battleground in the War on the Poor. The Government of Ontario has cut welfare rates deeply and removed tenants’ legal rights to the point where thousands have lost their homes. At the same time, Toronto City Council has failed to provide enough hostel space for those on the streets while their cops are engaged in an all out drive to force panhandlers and squeegeers off the streets and the homeless out of the parks. Just like New York City, they are trying to turn the central part of Toronto into a wealthy showcase that only yuppies can afford to live in and that only those with cash in their pockets are welcome to visit.[126]

Figure 4

Flyer, 2000

The drive to remove homeless people, wrote OCAP, was “being undertaken to serve and protect business interests and yuppie residents’ associations and at the urging of local politicians, like Kyle Rae, who hate and fear the homeless.”[127] Writing to Lastman in support of Safe Park, one woman concurred, arguing the shelter crisis was “exacerbated by a massive police drive to force homeless people out of parks and the central area of the city to make way for commercial and upscale housing development.”[128] For this reason the “targeting of businesses [became] a frequent tactic of OCAP’s,” exemplified by the protest at the film festival that opened this article.[129]

In a context of continued police harassment and violence, the City’s failure to grant OCAP’s request for a Safe Park was one more indication to some advocates that Toronto was turning into a “mean city.” “What kind of society have we become?” asked one supporter. “We cannot provide housing and we cannot provide shelter. Now we do not let homeless people sleep safely in our parks.”[130] For this reason OCAP’s Safe Park was to be “a place of safety and solidarity for the homeless where people can live without violence and harassment.”[131] With support from local health agencies, the TDRC, progressive trade unions, and the Mohawks of Tyendinaga, on 7 August, OCAP, homeless people, and their supporters cordoned off a portion of the park with rope and bedded down for three nights until police, in a dawn raid, broke it up; thirty people were arrested.[132]

In the aftermath of the Safe Park action, OCAP was criticized in the media for its confrontational tactics, for failing to have mobilized a stronger coalition, and for using the homeless as pawns.[133] Others, however, spoke out against the use of police repression, and the action generated new mobilizing support from some unexpected sources. “It is too easy to push frail, homeless and poor people out of parks and off the streets,” argued a representative from the Toronto and York Region Labour Council. “The time, energy and money being spent on this quick fix should be spent on addressing the real problems of growing inequality and marginalization facing Toronto.” An ally from the Metro Network for Social Justice concurred, blaming the visibility of poverty on “ten years of cuts to social programs, massive layoffs and falling wages.”[134] “Shocked and appalled” by the arrests at Safe Park and the harassment of homeless people by the City, an unlikely alliance of student activists mobilized spontaneous solidary action, vowing to sleep in Allan Gardens every Friday night “until such time as concrete action is taken by all levels of government to address the problem of homelessness.”[135] The students maintained their protest for over two years, despite the arrest, early on, of one of the group’s leaders.

The Safe Park has been described here in some detail because it exemplifies how the urgent demands for shelters, housing, and the end of punitive treatment of homeless people were framed within a forceful critique of urban restructuring by anti-homeless advocates and activists in the 1990s. The Safe Park was mobilized in the middle of a year of growing and unprecedented popularity for OCAP, book-ended by two demonstrations on Parliament Hill. The mobilizing success of these actions gave OCAP the confidence and momentum to organize its largest demonstration the following year, on 15 June 2000, an event that was subsequently dubbed the “Queen’s Park Riot.” On that day between 1,000 and 1,500 people demonstrated at the provincial legislature, Queen’s Park, to support the right of a delegation of homeless people to present three demands to the legislature directly: repeal of the 21.6 per cent cut to welfare, the Tenant Protection Act, and the Safe Streets Act.[136] Two years later, OCAP was again able to mobilize unprecedented support for its “Pope Squat”—the takeover of an empty building in the gentrifying neighbourhood of Parkdale, timed to coincide with the visit of the pope to Toronto. Like so many of OCAP’s demonstrations, both actions were framed as a direct challenge to urban restructuring in Toronto, specifically those economic and political processes that were responsible for displacing poor people from their homes and removing homeless people from public space.

Conclusion

While both homelessness and urban restructuring have been the object of growing academic interest and concern in recent decades, we know much less about the movements that developed to oppose them. In this social movement history I have been especially concerned to explore the linkages between the movement to fight homelessness and urban restructuring during a crucial period of global urban change, a period in which Toronto was transformed “from the core city of the Canadian political economy into a secondary global city.”[137] I have argued that anti-homeless activism and restructuring were linked in two specific ways. First, advocates and activists understood mass homelessness to be associated with, and even a direct result of, urban restructuring; throughout this period, collective action was predicated on critiques of occupational and economic change, gentrification, welfare state retrenchment, and entrepreneurial modes of urban governance. Second, the changing nature of the political context influenced the organizational and strategic dimensions of the movement over time, with different demands and tactics defining the movement across the two cycles of collective action that were explored in this article and with different outcomes.

Mobilized at a time when Canadian governments had not yet entirely adopted neo-liberal modes of governance, collective advocacy and activism in the 1980s achieved some significant concessions, including a notable expansion of government-subsidized affordable housing and the extension of the rights to publicly subsidized housing to previously excluded groups. Ultimately, however, these interventions proved too limited to halt the effects of economic restructuring that were transforming the landscape of urban poverty. In the context of urban restructuring, the minimum required from the government to stem the tide of homelessness in Toronto was a radical intervention in housing and welfare. Given that Canadian governments have never been prepared to take sufficient action to meet all Canadians’ critical housing needs, preferring instead to rely on market forces, it was unlikely that such radical intervention would have been forthcoming in this period of incipient neo-liberalization and urban entrepreneurialism.[138] When a second, more pronounced crisis of homelessness became evident in the 1990s, anti-poverty advocates and activists successfully mobilized once again, this time in a much more politically hostile environment. If substantial government intervention was unlikely in the 1980s, it was patently out of the question in the second half of the 1990s, especially since government cutbacks to housing and welfare were so instrumental in escalating the homeless crisis. Thus, notwithstanding the brief popularity of anti-homeless politics in Toronto at this time, the movement achieved few substantial gains in these years, even if it did pave the way for renewed, albeit inadequate, government intervention in housing in the years ahead.

Although sporadic action against homelessness would continue for several more years, after 2003 homelessness began to recede as a priority amongst anti-poverty activists and advocates in the city and was replaced by other concerns: “raising the rates,” reforming social assistance, and influencing the provincial government’s planned poverty reduction strategy.[139] In 2003, new provincial and municipal governments were elected in Ontario and Toronto respectively, both of which promised to chart new, more socially progressive, programmatic paths that raised the prospect of enhanced state support for poor and homeless people. The most significant change in this regard would be the implementation by the City of Toronto of an ambitious program to solve homelessness, Streets to Homes, in 2005, a programmatic intervention that has dramatically changed the political landscape of homelessness in the city. According to municipal data, by 2008 the Streets to Homes program had successfully housed over 1,500 street homeless people, giving cause for the mayor at that time, David Miller, to claim that Streets to Homes was helping the City “to end street homelessness”; Streets to Homes, he stated, was making Toronto “a more inclusive city.”[140] During the next four years, over 1,500 more rough sleepers were housed through the program, and the numbers have since continued to grow.[141]

Notwithstanding the success of Streets to Homes at placing street homeless people into housing, the total number of homeless individuals in Toronto has not declined, even if the number of rough sleepers has been substantially reduced; indeed, according to data from the City’s most recent Street Needs Assessment—a snapshot count of homelessness in Toronto—the total number of homeless people has consistently increased since 2006, as the number of homelessness individuals counted in shelters and correctional facilities has grown.[142] These data suggest that while street homelessness in Toronto is being better managed, primarily through Streets to Homes, homelessness has not been solved and the analysis presented in this article suggests an important reason why. This history of twenty years of anti-homeless advocacy and activism suggests that homelessness will continue as long as its root causes are not addressed—as long as the uneven dynamics of urban restructuring continue to shape the landscape of urban poverty in Toronto.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for the extremely useful suggestions they made to improve the paper. I also want to offer a special note of gratitude to Abigail Sone for the careful reading and detailed suggestions she made on countless drafts of this article.

Biographical note

Jonathan Greene is an associate professor in the Departments of Political Studies and Canadian Studies at Trent University, where he teaches courses on Canadian political economy, urban studies, poverty, and collective action. His research examining homelessness and the dynamics of collective action in Toronto, and London, England, has been published in Studies in Political Economy and Policy and Politics. His current research explores contemporary state strategies to manage homelessness.

Notes

-

[1]

OCAP Poster, 1999.

-

[2]

Stefan Pilipa (OCAP), to mayor and City Council, 18 August 1999 (personal archive).

-

[3]

As late as 1977 it was reported in Toronto that the most common forms of accommodation used by “the homeless” were hostels, flophouses, and rooming houses. Dennis A. Barker (commissioner of planning), Report on Skid Row (Toronto: City of Toronto Planning Board, Research and Overall Planning Division, November, 1977), 9. Classic statements of this earlier view appear in Theodore Caplow, Howard M. Bahr, and David Sternberg, “Homelessness,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, ed. David L. Sills, 6: 494–9 (New York: Free Press, 1968); Howard M. Bahr, ed., Disaffiliated Man: Essays and Bibliography on Skid Row, Vagrancy and Outsiders (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970); and Howard M. Bahr, Skid Row: An Introduction to Disaffiliation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973). In Toronto, in addition to Barker, see John L. Spencer, Report of the Committee on Homeless and Transient Men (Toronto: Social Planning Council of Metropolitan Toronto, 1960).

-

[4]

Kim Hopper and Jim Baumohl, “Redefining the Cursed Word,” in Homelessness in America, ed. J. Baumohl, 3–14 (Phoenix: Oryx, 1996); and J. David Hulchanski, Philippa Campsie, Shirley B. Y. Chau, Stephen W. Hwang, and Emily Paradis, “Homelessness: What’s in a Word?,” in Finding Home: Policy Options for Addressing Homelessness in Canada (e-book), ed. J. David Hulchanski, Philippa Campsie, Shirley B.Y. Chau, Stephen W. Hwang, and Emily Paradis (Toronto: Cities Centre, University of Toronto, 2009).

-

[5]

Hulchanski et al., “Homelessness.”

-

[6]

For summaries of these debates, see Lois Takahashi, “A Decade of Understanding Homelessness in the USA: From Characterization to Representation,” Progress in Human Geography 20, no. 3 (1996): 291–310; and Paul Koegel, M. Audrey Burnam, and Jim Baumohl, “The Causes of Homelessness” and Rob Rosenthal, “Dilemmas of Anti-Homeless Advocates and Activists,” in Baumohl, Homelessness in America, 24–33 and 201–12 respectively.

-

[7]

David Hulchanski, “Did the Weather Cause Canada’s Mass Homelessness? Homeless Making Processes and Canada’s Homeless Makers,” Toronto Disaster Relief Committee Discussion Paper, March 2000, City of Toronto Archives (hereafter CTA), fonds 335, series 1779, box 543928, folio 30, file 166.

-

[8]

Edward J. Soja, Rebecca Morales, and Goetz Wolff, “Urban Restructuring: An Analysis of Social and Spatial Change in Los Angeles,” Economic Geography 59, no. 2 (1989): 195; and Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore, “Neoliberalism and the Urban Condition,” City 9, no. 1 (2005): 101–2. Also see, for example, Michael Peter Smith and Joe R. Feagin, eds., The Capitalist City: Global Restructuring and Community Politics (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1987); John R. Logan and Todd Swanstrom, eds., Beyond the City Limits: Urban Policy and Economic Restructuring in Comparative Perspective (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990); and Neil Brenner, New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Re-scaling of Statehood (Oxford University Press, 2004). On restructuring in Toronto, see R. Alan Walks, “The Social Ecology of the Post-Fordist / Global City? Economic Restructuring and Socio-Spatial Polarisation in the Toronto Urban Region,” Urban Studies 38, no. 3 (2001): 407–47; and William J. Coffey and Richard G. Shearmur, “Employment in Canadian Cities,” in Canadian Cities in Transition: Local through Global Perspectives, eds. Trudi Bunting and Pierre Filion, 249–71 (Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2006).

-

[9]

Ibid. Also see Jennifer R. Wolch and Michael J. Dear, Malign Neglect: Homelessness in an American City (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1993).

-

[10]

David Ley, Gentrification in Canadian Inner Cities: Patterns, Analysis, Impacts and Policy (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1985). A good overview of the extensive literature on gentrification is provided in Loretta Lees, Tom Slater, and Elvin Wylie, Gentrification (New York: Routledge, 2007).

-

[11]

Wolch and Dear, Malign Neglect; Gerald Daly, Homeless: Policies, Strategies and Lives on the Street (London: Routledge, 1996); Anne Golden, William H. Curry, Elizabeth Greaves, and E. John Latimer, Taking Responsibility for Homelessness: An Action Plan for Toronto (Toronto: City of Toronto, 1999), 17–18; and Stephen Gaetz, “The Struggle to End Homelessness in Canada: How We Created the Crisis and How We Can End It,” Open Health Services and Policy Journal 3 (2010): 21–6. The literature on neo-liberalism and neo-liberalization is extensive. See, for example, Neil Brenner and Nike Theodore, eds., Spaces of Neoliberalism and Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003); David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); and Jason Hackworth, The Neoliberal City (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006). On neo-liberalization in Toronto specifically, see Julie-Ann Boudreau, Roger Keil, and Douglas Young, Changing Toronto: Governing Urban Neoliberalism (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009).

-

[12]

Tim Hall and Phil Hubbard, “The Entrepreneurial City: New Urban Politics, New Urban Geographies?,” Progress in Human Geography 20, no. 2 (1996): 153. The classic essay on urban entrepreneurialism is David Harvey, “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation of Urban Governance in Late Capitalism,” Geografiska Annaler B 71, no. 1 (1989): 3–17.

-

[13]

See note 8.

-

[14]

Loic Wacquant, “Urban Marginality in the Coming Millennium,” Urban Studies 36, no. 10 (1999): 1639–47.

-

[15]

See, for example, Victoria Rader, Signal through the Flames: Mitch Snyder and America’s Homeless (Kansas City: Sheed and Ward, 1986); David Wagner, Checkerboard Square: Culture and Resistance in a Homeless Community (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1993); Rob Rosenthal, Homeless in Paradise: A Map of the Terrain (Philadelpia: Temple University Press, 1994); and Talmadge Wright, Out of Place: Homelessness, Subcities, and Contested Landscapes (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1997). For an overview of anti-homeless advocacy and activism, see Rosenthal, “Dilemmas”; Douglas R. Imig, Poverty and Power: The Political Representation of Poor Americans (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996); Kim Hopper, Reckoning with Homelessness (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003), chap. 7; and David Wagner, with Jennifer Gilman, Confronting Homelessness: Poverty, Politics, and the Failure of Social Policy (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2012).

-

[16]

Pierre Filion, “The Urban Policy-making and Development Dimension of Fordism and Post-Fordism: A Toronto Case Study,” Space & Polity 5, no. 2 (2001): 85–111.

-

[17]

Jack Layton, Homelessness: The Making and Unmaking of a Crisis (Toronto: Penguin, 2000), 4.

-

[18]

“Responding to the Squeeze: ‘The Third House,’” Fred Victor Mission Newsletter (Fall 1982), CTA, fonds 7, series 55, box 79843, folio 4, file 525.

-

[19]

Metropolitan Toronto, No Place to Go: A Study of Homelessness in Metropolitan Toronto: Characteristics, Trends and Potential Solutions. Prepared for the Metropolitan Toronto Assisted Housing Study (Toronto: Metropolitan Toronto, 1983), 7–8; Ontario Task Force on Roomers, Boarders and Lodgers, A Place to Call Home: Housing Solutions for Low-Income Singles in Ontario (Toronto: Task Force, 1986); Ontario, Minister’s Advisory Committee on the International Year of the Shelter for the Homeless, More Than Just a Roof (Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Housing, 1988), 10; City of Toronto, Report Card on Housing and Homelessness 2003 (Toronto: City of Toronto, 2003), 14.

-

[20]