Abstracts

Abstract

Vancouver is known internationally as one of the world’s most livable and beautiful cities, and its “natural” attributes are seen as being integral to what makes it so special. Nestled on a small plateau between the alluring beaches and dramatic shoreline of the Pacific Ocean and the Coast Mountain Range, the city has trumpeted its aesthetically stunning environment for over one century. Central to this message has been the fact that Vancouver’s drinking water supply is so clean that it has historically required no chemical or other treatment—besides a basic filtering—before it is fit for human consumption.

Those who were initially responsible for administering the city’s water supply demonstrated most curious behaviour in carrying out their duties. To be sure, they exalted their water for its purity and broadcast this message to the world, believing as they did that such a precious resource could originate only in pristine wilderness that was as pleasing to the eye as it was free from human intrusions. As a result, they went to enormous lengths to guard the basins from which this water came from anthropogenic activity. Paradoxically, they were completely comfortable with undertaking a series of measures to re-engineer and manage the watersheds upon which they depended, an approach that included dumping tons of a deadly toxin on the local trees. All these steps were simply part of their efforts to enhance the bounty with which Providence had gifted them, and to them it remained pure and unsullied as a result. The early history of managing Vancouver’s drinking water thus represents an extraordinary instance in which civic boosters viewed their actions through a prism that blurred the line between the human and non-human worlds, and their story highlights how often our attempts to manage “nature” is prone to creating issues that are potentially more dangerous than the ones we are trying to solve.

Résumé

Vancouver est considérée internationalement comme une des villes les plus belles et des plus agréables à vivre, en raison particulièrement de l’intégration de son environnement naturel. Nichée sur un petit plateau entre de séduisantes plages, les côtes dramatiques du Pacifique et la chaîne Côtière, la ville clame hautement son environnement fortement esthétique depuis plus d’un siècle. La qualité de son eau a fait partie intégrante de ce message du fait que ses sources d’eau potable sont d’une qualité telle qu’à travers son histoire, la ville n’a jamais eu besoin de la traiter chimiquement ou d’autre façon, hors un simple filtrage.

Les responsables des débuts de l’administration de l’approvisionnement en eau potable de la ville ont fait preuve d’habitudes curieuses dans la conduite de leurs tâches. Ils ont en effet chanté la pureté de leur eau à travers le monde, croyant, pour avoir une eau de si grande qualité, qu’il fallait absolument la prélever dans un environnement sauvage aussi intact et beau qu’il était exempt d’intrusion humaine. Ils ont donc déployé tous les moyens pour préserver les bassins dans lesquels était prélevée cette eau potable. Ils étaient toutefois et paradoxalement entièrement confortables avec le fait de métamorphoser et gérer ces sources dont ils dépendaient, approche incluant l’administration d’énormes quantités de toxines sur les forêts environnantes. Ces processus étaient d’ailleurs considérés comme une accentuation des dons de la Providence dont ils jouissaient, et qui n’en affectaient nullement la pureté et l’intégrité. L’histoire des débuts de la gestion de l’eau potable de Vancouver représente donc un cas où la perception qu’avaient les promoteurs civiques de leur travail brouillait les limites entre mondes humain et non humain. Cette histoire met en lumière la fréquence avec laquelle nos tentatives de gérer la nature créent généralement des problèmes potentiellement dangereux et bien plus importants que ceux auxquels on tente de répondre.

Article body

Vancouver is known internationally as one of the world’s most desirable cities in which to live, and its “natural” attributes are seen as elemental to what makes it so special. It is situated within the triangular Fraser Lowland, which spans the border between Canada and the United States and is composed of gently rolling uplands separated by wide, flat-bottomed river valleys. The latter’s rich soils are an amalgam of glacial deposits, debris eroded from the nearby mountain valleys by ice, and sediment from the mighty Fraser and other smaller rivers. Vancouver is thus nestled between the alluring beaches and picturesque shoreline of the Pacific Ocean on the west, the rugged Coast Mountain Range to the north, and Cascade Mountains to the east and southeast.[1] For over a century Vancouver has trumpeted its breathtaking environment, and integral to this message has been the unparalleled quality of its drinking water. Drawn from several waterways that have carved steep valleys in the hilly terrain just outside the city’s northern edge, it is so pure that historically it required no chemical or other treatment—besides a basic filtering—to render it fit for human consumption.

Those who were initially charged with administering Vancouver’s water supply demonstrated most curious behaviour in carrying out their duties. On the one hand, they cherished and exalted their water for its purity and believed that such a transcendent substance could come from only practically pristine watersheds that were as aesthetically stunning as they were free from human intrusions.[2] In other words, it was imperative that these areas represented wilderness, and by their definition this meant that Homo sapiens was absent. In fact, volumes have been written over the last three to four decades about conceptions of wilderness and how it is a discursive construction and not simply a pre-existing “natural” condition. William Cronon provided what is arguably the most often cited treatment of the subject in the mid-1990s, a piece in which he expertly demonstrates the remarkably wide range of connotations that humans have attached to this concept.[3] As a result, the guardians of Vancouver’s water supply did all they could to protect the basins from whence it came from anthropogenic activity. This included fighting to keep these regions free from logging, restricting access to them, and requiring those humans who simply had to work in them to adhere to a long list of health regulations.

But there was another side to this same coin for managers of Vancouver’s water supply. These stewards were comfortable carrying out a remarkable range of activities in these watersheds in order to realize several goals. To ensure that Vancouverites would be guaranteed enough water far into the future, for example, they re-engineered nature by constructing massive dams and draining lakes. Moreover, preserving the purity of this water even involved applying toxins to kill a native insect that had begun ravaging the local trees, all while paying no heed to the potential danger that such a poisonous treatment posed to the very water supply they were aiming to protect. All these actions resonate with the stories that historians have told more recently about views of wilderness during the early to mid-1900s, whereby it could be seen as being pure and unsullied even though it was being reconfigured for human gain.[4]

In making its case, this article adds to the substantial and rapidly growing body of literature—including a special edition of Urban History Review—that bridges environmental and urban history. For example, studies have assessed how activist urban groups pushed civic officials during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to cleanse their municipalities as part of a social impulse to reform city life.[5] This often meant that they faced a dilemma. At the core of these issues was the inherent paradox that defines the public contestation over environmental nuisances in urban spaces. To quote Owen Temby, “They are both a result of and hindrance to local economic activity.” [6] The case of Vancouver and its drinking water demonstrates, however, that there can be significant exceptions to this paradox. The city’s boosters perceived of their urban centre as a veritable “growth machine,” but the nuisances that they sought to tackle in relation to their water supply were unique. Addressing them did not raise a concern about fettering the city’s industrial progress; rather, the opposite was true. Vancouver’s leaders felt that it was incumbent upon them to implement measures—some of which were expensive—to manipulate and protect the local water supply to sustain the upward trajectory of their metropolis. Moreover, much of the historiography in this field has highlighted how elite groups in urban settings fought to improve the health of their communities but did so in a way that unequally distributed the benefits of their actions in favour of the upper class.[7] Although this tale about Vancouver is hardly unusual in terms of the city’s political leaders having spearheaded its drinking water movement, it is exceptional that the benefits of their actions accrued equally across all segments of society. Moreover, there was unanimity among the civic officials, the citizens they served, and the local media on how the city handled the issues it faced.

This article also engages the literature in the field of urban infrastructure development by demonstrating how advocates for Vancouver’s water supply capitalized on changing political circumstances and implemented innovative governance solutions to win the day.[8] For example, the city’s water managers initially encountered stiff headwinds in the 1890s when they sought to push their agenda with the provincial government, because the city simply lacked the political weight to realize its aims. Within a few decades, however, Vancouver had grown to become British Columbia’s metropolis and locus of power, and its representatives and those from the adjacent municipalities occupied roughly one-quarter of the seats in BC’s legislative assembly.[9] As a result, what was good for Vancouver had very much become what was good for the provincial government. This created the political milieu within which the city’s champions could extend their temporal sphere of influence far beyond their civic boundaries in order to serve their purposes.

In addition, this article contributes a new voice to the discourse on the history of managing both ends of municipal water systems—the provision of drinking water and the expulsion of waste—within Canada and throughout the world.[10] These accounts trace how urban centres aggressively adopted the latest technology and managerial methods in an effort to grapple with the challenges they faced. What makes the story of Vancouver’s water managers so noteworthy is the extent to which they did so selectively.[11] On the one hand, they fully embraced the notion that hiring a scientifically trained, technical expert and allowing him to adopt the modus operandi of modern water managers was highly desirable. In fact, his professional credentials legitimized their plans and the means needed to achieve them. On the other hand, however, they never even seriously considered adopting the prevailing contemporary approach—chlorination—to ensure that the city’s residents had a safe supply of water.

And herein lies the crux of the story. It was hardly surprising that Vancouver’s water advocates adopted a modernist approach to deal with their environmental problems. It was also to be expected that doing so resulted in a reconfiguration of nature in a way that left them blinded to the indelible impressions their intrusions into the non-human world left upon it. Authors such as Richard White and Daniel Schneider have masterfully analyzed these themes in their works about the “organic machines” such approaches created and the myriad contradictions that are to be found in the resultant “hybrid nature.” [12] But what distinguishes the story of Vancouver’s water supply was the degree to which it represents such an extreme example of these dynamics and the irony that pervades the tale. The city’s officials did not see their work to re-engineer their water supply as an attempt to denature it but rather enhance the bounty with which Providence had already granted them by retaining its pristine qualities. In this story, Vancouver’s water supply was so profoundly valued not because of its size or scope or volume, or strictly because of its sublime dimension, but primarily because it was unsullied by human activity. The civic boosters who sought to protect it conceived of their actions as feats that honoured and preserved the sanctity of their water supply by fine-tuning it. As a result, the early history of managing Vancouver’s drinking water provides an extraordinary instance in which civic boosters viewed their actions through a prism that blurred the line between the human and non-human worlds, and recounting their story underscores how often our attempts to manage the non-human world is prone to creating issues that are potentially more dangerous than the ones we are trying to resolve.

* * *

A large and growing body of literature has chronicled the rise of basic municipal services in Vancouver, and much of it has emphasized the unique advantages the city enjoyed in this regard. Because it matured around the turn of the twentieth century and thus arrived comparatively late to the party that was rapid urban growth in North America during this period, it was well positioned to avoid many of the difficulties that plagued other major municipalities that had come of age much earlier. By the time New York City’s population had breached one million in the 1870s, for example, and it was grappling with the attendant gamut of health and welfare problems as a result, Eric Nicol describes Vancouver as having been “a gaggle of shacks constituting little more than impertinence to the surrounding wilderness.” When it was incorporated as a city in the mid-1880s, Vancouver still had a population of fewer than 10,000.[13] Even so, it was able to be proactive in tackling the challenges that beset its municipal rivals instead of having to adopt measures once the need arose.[14] Addressing these matters was seen as particularly important for urban centres that entertained grand visions of their future; doing so was seen as the sine qua non of a civilized society, particularly in terms of securing a plentiful supply of clean drinking water.[15] To be sure, this issue and outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and typhoid resulting from improper sewage disposal forced Vancouver’s guiding lights to take action on this front, as did a fire that razed much of the city in the mid-1880s. Nevertheless, Vancouver was born amidst a remarkable circumstance. As a promotional article about the city proclaimed years later, “Many towns or cities exist for years without a domestic water supply—not so Vancouver. On the very day, April 6, 1886, that the city obtained its Charter the [British Columbia] Legislature also granted to the Vancouver Water Works Company a franchise to provide the new city with water.” [16] Within a half-dozen years, the local municipalities had bought out the few private water companies and placed them under public control.[17]

Although the terrain that formed the heart of the city was not suited to providing its residents with drinking water (an article in a local paper in 1887 actually warned Vancouverites that “people drinking [well water here] are drinking poison”), fortunately the Coast Mountains that formed a northern bookend on the city’s growth were ideal for this purpose.[18] Snaking through their canyons were several southerly flowing waterways that were fed by the frequent rains and the melting snow of the nearby steep crags. Two were particularly well located for tapping their flows. The Capilano River had been dammed in the late 1880s to create Vancouver’s first drinking water reservoir, while the city began drawing from the Seymour River just after the turn of the century.[19] To deliver this drinking water to the bulk of Vancouver’s population, which lived in the municipalities across the Burrard Inlet, a number of mains were laid on and under its bed. They were set down where the Inlet’s northern and southern shores nearly touched, roughly at the mouths of the Capilano and Seymour Rivers (figure 1).[20]

From the outset, Vancouver’s guiding lights knew that being blessed with these supplies of drinking water made their city nonpareil on the continent, if not around the globe. First and foremost, nearly all other major cities in North America—and the world, for that matter—had no choice but to tap contaminated sources of water and render it potable by treating it with chemicals such as chlorine; protecting the purity of their water supply was thus not a major concern. In sharp contrast, the water that came from the Capilano and Seymour watersheds was so clean that it did not require such treatment to make it safe for human consumption. All that was needed was simple filtering before it could be imbibed by Vancouver’s residents. Thus the city’s leaders became obsessed with doing all they could to keep it immaculate.[21] In addition, the supply available to them seemed virtually limitless, which was a crucial consideration that could fetter any urban centre’s growth. Furthermore, it was located practically in Vancouver’s backyard, whereas many large cities in North America had been forced to build extensive aqueducts that were as long as several hundred miles to provide their citizens with water.[22]

Figure 1

Capilano and Seymour Watersheds Relative to Municipalities in the Lower Mainland

The Capilano Watershed is on the left and the Seymour Watershed is the long, thinner one to its right. The Lynn Watershed (the small, enclosed area below the Capilano) would be managed as part of the Seymour system.

Together, these factors suggested to many in the Lower Mainland in the early part of the twentieth century that Providence had preordained Vancouver as a city that would soon rank among the continent’s greatest metropolises. The media repeatedly boasted, “Vancouver has many natural advantages as a city, and one of the most important of these is plenty of pure fresh mountain water and its proximity to its source.” [23] Likewise, the province’s largest daily declared triumphantly in the mid-1920s that an “adequate water supply of quality unquestioned is a prime factor in the prosperity of every community. The group of communities … described as Greater Vancouver have the good fortune to have such a supply … Crystal pure and sparkling, the water which answers the turn of the tap in more than 50,000 homes in the Vancouver [area] comes direct from the snows and glaciers in the high peaks which reach the skyline across Burrard Inlet.” [24]

An integral part of this “cult of pure water” that grew up around the Capilano and Seymour Rivers was the physical environment in which they were located. For starters, their appearance rendered them aesthetically appealing; they captured all the sublime features of wilderness that were so cherished at this point in Canada’s history.[25] They were covered by stands of red cedar and western and mountain hemlock and punctuated by canyons and rock faces, down which the Capilano and Seymour Rivers meandered and pooled at times, while at others rushed over thundering cascades (figure 2). For local boosters, these areas exemplified natural splendour. When in the mid-1920s the British Columbia Electric Company deeded a large property on the Capilano River to the Vancouver Board of Trade to be used for a public park, for example, the Vancouver Daily Province described its “scenic delights” and asserted that they comprised “the most magnificent scenery on the American continent.” At about the same time the newspaper noted in a front page story that a Hollywood film crew was setting up a shoot on the Seymour River because of its natural allure, even though the movie was about the Klondike gold rush and the local landscape did not truly resemble the famous river in the Yukon. The Province gushed that the choice of locales by the head of production reflected his view that the scenes along the Seymour “are infinitely more beautiful” and were some of the “most beautiful he had seen.” [26]

Furthermore, and more significantly, such immaculate water could have come only from a pristine setting, one that showed virtually no traces of human activity. In this regard, the Capilano and Seymour Rivers and their surrounding areas fit the bill almost perfectly (more on these imperfections later). The waters that flowed through these courses could hold such divine qualities only because they were being collected in watersheds that were essentially untouched by the contamination of modern day life. As the city’s chief engineer remarked in the late 1880s about the Capilano River, “No purer water can be obtained from any source” because it flowed “swiftly over a boulder bed, through deep rocky canyons, and along shores as yet uncontaminated by the impurities which follow in the wake of settlement.” [27]

Figure 2

Seymour Falls represented all that was sublime about the watersheds from which Vancouver drew its water.

Blessed with this nearby and plentiful supply of extraordinary drinking water, practically from the time Vancouver was incorporated in the mid-1880s its boosters could not help but boast to the world about their good fortune.[28] Considering that most urban dwellers in North America did not drink water prior to the 1930s, largely because of health concerns, Vancouverites had good reason to crow.[29] On the eve of the First World War, for instance, after the city had enjoyed over a decade of frenetic growth, the province’s promotional literature ramped up its florid vocabulary as it waxed poetic about the city’s water supply. In reference to both the Seymour and Capilano Rivers, British Columbia Magazine trumpeted that “their value is inestimable” and that they were “more vital to Vancouver than the service of beauty; they are battalioned in the army of utility.” The article continued by emphasizing that “these blue mountains do more than picture rugged scenery across the canvas of the imagination. The man with the utilitarian ideas might scoff at the word painter, but the tinctured draught he gulps down in the heat of the midsummer inspires him with the utmost of respect. It is out of the heart of these towering piles that the welcome water comes, fresh to his lips from glacial beds ages old.” [30] Ultimately, the magazine pointed out, Vancouver’s water was “as pure as any in the world.” [31]

Events during the first few decades of the twentieth century made it essential for Vancouver to take effective action to protect its water supply. The city grew rapidly during this period, spurred by the exploitation of British Columbia’s timber and minerals and Vancouver’s emergence as Canada’s western outlet for the shipment of these commodities, as well as wheat from the western part of the prairies. Trade in these goods also increased exponentially with the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. By the end of the next decade the port of Vancouver was shipping by far the largest volume of goods in Canada.[32] British Columbia’s southernmost reaches were also blessed with Canada’s most favourable climate, increasing their attraction as a place to live. The province’s population in general, and Vancouver’s in particular, exploded as a result. Whereas the city counted just over 25,000 residents in 1901, roughly thirty years later it was home to nearly a quarter of a million persons.[33] This prodigious population growth increased the demands on its water supply and, perhaps more importantly, the potential threats posed to it by industrial and residential development.

From the outset, Vancouver’s leaders faced a major hurdle in addressing these concerns. The areas upon which they relied for water were located beyond their municipal boundary and comprised Crown land, which was controlled by the provincial government. The fact that Vancouver’s officials exerted relatively meagre influence with it just before and after the turn of the twentieth century thus greatly diminished their chances of exercising their authority over these lands. Moreover, the BC government had been leasing tracts of them to interests that sought to harvest their timber. This activity generated significant income for the province, and it was reluctant to give up any of this revenue. As a result, when Vancouver’s municipal leaders began asking for the BC government to grant them control over the river valleys from which they drew their drinking water, provincial officials only partially acceded to the requests. Expectedly, the first area on which attention was focused was the Capilano River, which had been dammed only a few years earlier to create a reservoir. In 1892, the BC government agreed to Vancouver’s request to be given a reserve of land in this watershed, but it encompassed only the area immediately adjacent to this river and its tributaries. In making its case, the city’s officials had argued that these tracts must be placed under the city’s control “in order to maintain the purity of the water.” Just over a dozen years later when the provincial government reserved a much larger portion of the Capilano River valley for the city, again “for the purpose of keeping the said water immune from contamination,” the action did not preclude the local timber from being harvested. The next year the city’s guiding lights used the same procedure to establish a legal cordon sanitaire along the Seymour River, which they had recently begun tapping. In placing a reserve on the unalienated land along this waterway (again its timber could still be cut), the BC government explained that it was doing so “with a view to conserving, as far as possible, the water of said Creek, and keeping the same free from all impurities.” [34]

Having done what they could to prevent other interests from gaining control over the physical space encompassed by these watersheds, those who were concerned about such matters turned their attention to guarding against persons—such as loggers and hikers—who had a legal right to be in these areas. Near the end of the First World War provincial officials drew up a comprehensive set of “Sanitary Regulations Governing Watersheds” under BC’s Health Act, which applied to anyone travelling on or through areas “above or beyond a municipal intake, reservoir, or dam.” Such persons were required, for example, to produce a certificate from “a licensed medical practitioner that they are not affected by any disease which, in his opinion, would pollute the water.” Similarly, they were obliged to carry documentation that their inoculations were current and that their blood had been tested to ensure that they were not carriers of afflictions such as typhoid fever, diphtheria, and venereal disease. In addition, logging camps in these areas had to be operated according to the most stringent health regulations. These included providing modern laundry and bathing facilities, whose grey water had to be properly treated and sterilized rather than dumped, untreated, in the local waterways. For human waste, proper urinals were required, as was the “pail system.” Workers were to defecate into “galvanized iron pails with covers,” into which a small quantity of “sawdust, which was previously treated with oil,” had been “sprinkled after each evacuation.” Anyone not following these protocols would be “instantly discharged.” Although these regulations flew in the face of logging camps’ notoriously dirty and crowded modus operandi, they outlined further behavioural requirements that seemed practically ludicrous, considering the conditions under which these bushmen lived and worked. “Spitting or blowing noses onto the ground and all other filthy habits,” a clause in section 8 stipulated, were “absolutely forbidden.” In sum, the regulations declared that “cleanliness, of course, is necessary for the health of the men and it must be insisted upon. Persistently unclean persons will be debarred from the watershed.” To ensure that these edicts were enforced, each municipality was to appoint a watershed sanitary inspector.[35]

Despite these measures, a crisis developed in the wake of the First World War in the urban centres of BC’s Lower Mainland over the supply and quality of their drinking water. The area was experiencing significant development and population growth (most returning veterans opted to head to these urban centres in search of work instead of taking up the government’s offer to become farmers in the hinterland), and the provision of municipal services had naturally become a pressing concern. The conflict about water centred on inequitable “sharing” agreements into which many of the region’s municipalities had entered. These contracts had created an intolerable situation, whereby the City of Vancouver had ended up with control over practically all the water available to the communities in the Lower Mainland but had proven incapable of administering it effectively. This problem was rendered urgent because the neighbouring municipalities were growing more rapidly than Vancouver, yet the latter enjoyed a near monopoly on the local water rights.

Devising a solution to this vexing issue became a high priority for the BC government because the pendulum of political power in the province had swung decidedly in favour of the Lower Mainland. BC’s ruling Liberal government was sustained largely by the urban vote, and the Lower Mainland’s metropolitan area now towered over the province (it would soon represent roughly one-third of BC’s total population). Furthermore, Premier John Oliver’s administration demonstrated an abiding faith in the force of progressive policies to resolve the challenges it confronted. It was thus hardly surprising that the water problems facing Vancouver and its neighbouring communities quickly appeared on the provincial government’s radar, and that it took swift and deliberate action to address them once and for all. The effort was orchestrated largely by Ernest A. Cleveland, whom Thomas D. “Duff” Pattullo, BC’s minister of lands (1916–28), had appointed comptroller of provincial water rights in 1919.[36]

Cleveland personified the modern approach to managing nature to maximize the efficiency with which humans exploited it. Born in 1874 in New Brunswick and having first arrived in Vancouver in 1890, he had headed south of the border to gain his post-secondary education. Thereafter, he engaged in a general engineering practice; his firm of Cleveland & Cameron specialized in civil and hydraulic work. It carried out a number of consulting projects for the City of Vancouver’s Engineering Department before Cleveland headed to Victoria to take up his post as BC’s comptroller of provincial water rights just after the end of the First World War. Cleveland had immediately launched several major initiatives, one of which was an investigation of how best to supply water to Vancouver and its neighbouring municipalities.[37]

His report, published in 1922, was exhaustive and became the template for all water issues affecting these communities; in so many ways, it also poignantly captured the paradox that marked contemporary views of Vancouver’s water supply.[38] Cleveland’s landmark investigation was comprehensive, examining everything from the potential supply available to the municipalities on and near the Burrard Inlet to the challenges raised by water-sharing agreements. In addition, he highlighted how the City of Vancouver had glaringly failed to effectively protect the quality of the water it controlled. Cleveland convincingly demonstrated that the best means of guaranteeing all parties a sufficient supply of well-protected water both in the near and long terms was to effect a new arrangement immediately; he gloomily predicted that “the limit of the present system’s capacity will be reached before 1925.” He thus wholeheartedly recommended to the provincial government that it create a joint Metropolitan Water Board to oversee the cooperative development of the area’s waterways. He also dismissed outright the very idea of chlorinating the water to ensure it was safe to drink. It would be both costly and nonsensical, because these communities had access to “wholesome water furnished by nature undisturbed,” and a few simple measures—such as eliminating logging from the region—were all that was needed to safeguard its purity.[39]

In the same breath, however, he outlined how the Capilano and Seymour watersheds would have to be profoundly reconfigured in order to provide the volume of water that the municipalities required. Not only were their populations—and thus water needs—growing by leaps and bounds, but they had habitually been plagued by water shortages during the summer months, because much of the snow pack had melted by then and precipitation typically decreased at that time of year. So not only did Cleveland’s plan call for delivering more water to Vancouver, it also aimed to permanently terminate the natural ebb and flow of the local water courses. What he was proposing, then, was their transformation from “natural,” seasonal waterways into massive reservoirs that could be drained when it suited the ever-growing number of Vancouverites.

Cleveland’s plan was bold indeed. He stressed that the Seymour River was crucial to this strategy, because part of it could be converted into a massive new reservoir (a much smaller one already existed on the Capilano). Moreover, several small lakes in these watersheds—Loch Lomond, Burwell, and Palisade—could be dammed to dramatically improve their ability to conserve water. They could also be drawn by drilling tunnels underground so that their contents could be fed into the Capilano and Seymour reservoirs during the dry season. Furthermore, in tapping Palisade Lake at the head of an east branch of the Capilano River, Cleveland reasoned that it would be much more valuable to his scheme if it were diverted by a new conduit into the Seymour system instead. Cleveland’s policy paper, as the Vancouver Daily Province presciently described it, became almost immediately “the bible and text book of those who have been agitating for the creation of a Metropolitan Water Board.” [40]

Its genesis was delayed, however, by tumultuous bickering between the BC government and the City of Vancouver, and between the latter and its neighbouring municipalities. The provincial government enacted the legislation—An Act to Create the Greater Vancouver Water District—that gave birth to the Greater Vancouver Water Board (GVWB) in 1924. But then the City of Vancouver and Duff Pattullo, BC’s minister of lands, locked horns over how much control each would exercise over it. In the meantime, the neighbouring municipalities attacked Vancouver for its imperiousness, fearing that it would continue to hold them hostage in matters concerning their water supply. Cooler heads ultimately prevailed, whereby the approach to developing the local watersheds would be cooperative, a condition upon which Cleveland had been most insistent in his 1922 report.[41]

When the Water Board finally came into being, the terms under which it was established spoke volumes about the notion that the local water supply was as pure as freshly fallen snow and thus required ironclad protections to keep it chaste. The board’s structure initially included the City of Vancouver, and the respective Corporations of Point Grey and South Vancouver; practically all the neighbouring municipalities would join over the next half decade.[42] Each municipality had one member on the board, and they voted on whom to appoint as its chairman; it was practically a foregone conclusion that the board’s inaugural members would elect Cleveland to this post. In terms of its powers, the act declared that the GVWB would acquire, among other things, control over the watersheds, namely the Capilano and Seymour Rivers, which were already reserved for the purpose of providing Vancouver with water. In addition, the statute gave the board extraordinary powers, including the right to expropriate lands and timber “within or without the district, contiguous or adjacent to the source or sources of supply of water … used or intended to be used by the [board] for part of its waterworks and system or for the purpose of protecting or preserving such source or sources of water supply.” Moreover, for those who dared consider contaminating these fountainheads, there were grave consequences. No one was allowed, for instance,

to bathe the person, or wash or cleanse any cloth, wool, leather, skin of animals, or place any nuisance or offensive thing within or near the source of supply of such waterworks in any lake, river, pond, source or fountain, or reservoir from which the water of said waterworks is obtained, or shall convey or cast, cause or throw, or put filth, dirt, dead carcasses, or other offensive or objectionable, injurious or deleterious thing or things therein … or cause any other thing to be done whereby the water therein may in anywise be tainted or fouled or become contaminated.

Anyone found engaging in these outlawed activities was subject to a penalty of up to thirty days in prison “with or without hard labour,” or a fine of $50, or both.[43]

Even before the board had formally begun meeting in early 1926 (it took over Vancouver’s existing water works system and sources of supply on Dominion Day), Cleveland had begun aggressively implementing the blueprint he had laid out for it in his epic report for resolving Vancouver’s water issues. In particular, he drove forcefully and deliberately ahead on his strategy for vastly increasing the Lower Mainland’s water supply by radically manipulating nature. For instance, he quickly realized his goal of constructing a series of tunnels to tap small lakes that drained into the Capilano and Seymour Rivers. His most notable achievement in this realm was overseeing the excavation of a 650-foot tunnel to drain Lake Burwell into the Seymour River. The lake’s historical maximum depth had been 133 feet, but by September 1926 it had been drawn down to merely 25 feet in order to feed the Seymour system. Furthermore, he initiated reconstruction of the wooden dam on Lake Burwell to improve its ability to retain water.[44] To facilitate this and other similar projects, many miles of trails had to be cut through “the wilderness” to allow the workers and their equipment to reach these sites. More significantly, Cleveland carried out the construction of a huge new dam—430 feet wide by 30 feet high—on the Seymour River at its most famous falls, thereby obliterating them (figure 3). Not only would this house a new intake for the water that would go to Vancouver, but it would also allow for the creation of a massive new reservoir at this location.[45] Before filling it, the Water Board advertised for a contractor to raze the trees and brush from both the land that would be flooded and the right of ways for the new water mains that would connect to the dam; a local daily noted that this was “one of largest contracts for land clearing to be tendered by Vancouver.” [46] And to ensure that the re-making of this particular site was complete, Cleveland took steps to have it landscaped. When a group of local journalists visited it accompanied by the Water Board’s beaming members, the Vancouver Sun reported that “they found the grounds surrounding the buildings transformed into beautiful gladea and arrangements made for even greater beautification of the plant sites.” [47]

Within a few short years Cleveland’s whirlwind of activity had reconfigured the watersheds that fed the Lower Mainland its water supply. Under the headline “No Future Danger of Water Famine in This District,” the Vancouver Sun reported how, through Cleveland’s tireless efforts, “the almost inconceivable quantity of 7,800,000,000 gallons have been made available as a [collective] storage reservoir on the north shore.” [48] In addition, in 1929 Cleveland laid out for the Water Board his even grander plans for reconstruction of the local environment to ensure that Vancouver would have enough water in the near future to provide for 5,000,000 residents, even though the entire province’s population would not even reach 700,000 by the time the 1931 census was taken! [49]

Cleveland was concomitantly engaged in an arguably far more important task, protecting the water’s purity by preventing human intrusions into the area at best and minimizing their impact at worst. For example, the Capilano and Seymour watersheds contained significant volumes of merchantable timber, tracts of which had already been sold to local lumber companies, and the areas that had been reserved for the Water Board’s use could still be logged. Considering that these spaces contained some fine stands of western red cedar (for saw logs) and hemlock (for pulpwood), which were very close to the Lower Mainland’s mills, they were highly coveted. When the subject of harvesting these trees arose in the mid-1920s, the BC Forest Service charged Herbert Christie, the head of the University of British Columbia’s fledgling forestry school and one of Canada’s leading foresters, with investigating it.[50] In his report, Christie recognized that the City of Vancouver was “vitally interested in [disposal of the timber] because it is generally acknowledged that forest cover is beneficial and should be maintained on watersheds from which water supplies are drawn, because it prevents soil erosion, tends to regulate streams and keeps the water pure.” By the same token, Christie presented the case that these woodlands could still be logged selectively and in small patches, dead and diseased trees could be removed, and cutovers immediately replanted; taking these steps would minimize erosion and significantly improve the forest’s overall health. Not only would these measures protect these revered areas from which Vancouver drew its cherished water supply, but, as Christie stressed, they would guarantee the local timber firms a large annual harvest of wood in perpetuity. The former district forester, Major L.R. Andrews, resoundingly endorsed Christie’s plan, primarily because it would actually improve the tree cover on the watersheds over the long term. “A policy could be laid down,” Andrews argued, “consistent with the destinies and requirements of our city and its great future, so that our children, and those who come here, will be amply taken care of with pure, healthy water. This is a fundamental requirement if the wonderful future which we confidently predict and expect for Vancouver is going to materialize.” [51]

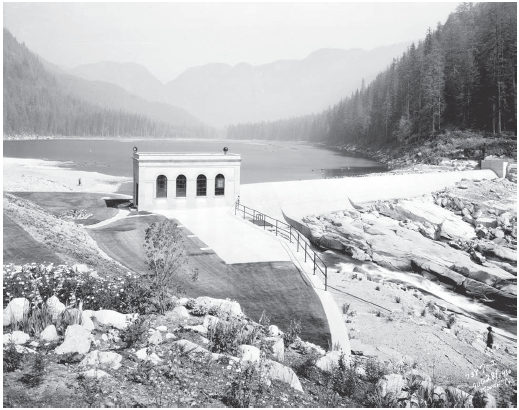

Figure 3

The dam at Seymour Falls was completed in 1926 and was crucial to transforming the river from being a natural waterbody with seasonal highs and lows into a reservoir tank that could be controlled to supply Vancouver with water. The building contained the screen house, through which the water passed before it was sent through a 60-inch, wooden conduit roughly four miles down the mountain to the city’s distribution mains. The local grounds were also landscaped to improve their aesthetic appeal.

Despite assurances that progressive forest management and pure water could coexist, advocates for Vancouver’s water supply would have none of it. In their eyes, these concepts were simply irreconcilable, and it was the view of municipal officials that no silvicultural expertise was even required to render this judgment. In response to the case Christie and Andrews presented, Charles Brakenridge, Vancouver’s engineer, stated that “selective logging is a principle in European countries but they are not dealing with steep slopes,” seeming to suggest that there was no commercial forestry in mountainous areas of the Old World. For Brakenridge, not even the application of the most avant-garde forestry practices could be trusted in this setting.[52]

As a result, one of Vancouver’s leading businessmen and its most outspoken advocate within the provincial government pressed his fellow politicians to transfer legal control of the Capilano and Seymour River valleys to the Water Board (most of these areas had already been reserved for its use), and his campaign benefited from both circumstance and the city’s willingness to help its own cause. Charles Woodward was owner and founder of the highly profitable Woodward Department Stores Ltd. A millionaire by the mid-1920s, he won provincial office in 1924 and was determined to increase Vancouver’s voice in provincial politics. In this regard, he was aided by the Lower Mainland’s increasing proportional representation in the provincial legislature and his success in publicizing his views to the press about the need for the Water Board to exercise exclusive control over the Capilano and Seymour watersheds. He also exploited his influence as a political insider to push the same agenda with John Oliver and “Duff” Pattullo, respectively BC’s premier and minister of lands.[53] Moreover, Woodward’s cause was aided by the fact that Cleveland, the Water Board’s chairman and the architect of the grand plan for it to control these watersheds, had enjoyed a successful career in the provincial civil service under Pattullo before landing his new post in Vancouver. He thus knew how to negotiate the labyrinth that led to the inner sanctum of decision-making power in the provincial government. Furthermore, the board had also demonstrated its willingness to act unilaterally to achieve its aims in this instance. On its own, it had asked for and received the blessing of local ratepayers in its campaign to purchase small private landholdings in these watersheds periodically when they became available.[54]

These forces coalesced to bear fruit in the late summer of 1927. At that time, the BC government leased the Capilano and Seymour watersheds to the board; at least one report recommended doing so because it would be best to leave them “untouched.” Not only did the agreement convey control over the timber in these areas to the board and charge it an annual rental of merely one dollar, but the contract was also set to run for an unprecedented term of 999 years. If ever there was an occasion to justify transgressing the common law doctrine known as “the rule against perpetuities,” clearly protecting Vancouver’s water supply was it. The sole fly in the ointment from the board’s perspective was the continued presence of the Capilano Timber Company, which retained its lease to over 160 acres of timber on the river.[55]

The firm’s workers were but a few of the humans who would inevitably be present in the Capilano and Seymour basins, so the GVWB zealously enforced the Health Department’s Sanitary Regulations Governing Watersheds, and then some. For example, the BC Forest Branch (BCFB) had rangers stationed in the district to protect the local trees against fire and monitor any harvesting activities. In addition, these officials, in cooperation with advocates for the north shore’s watersheds, had taken measures to control tenting in the areas. Aware that the Capilano watershed had become a popular recreational retreat, they had cleared a number of small sites on it—significantly below the intake—to prevent hikers from camping “promiscuously.” There were no such plots, and none would be created, on the Seymour because it had not yet been accessed by campers.[56] In addition, the Water Board was assiduous in verifying that workers engaged on any of the board’s projects that took place on these watersheds had their health credentials in order.[57] Even the well-heeled board members themselves were required to demonstrate, on their visits to these river basins, that all their inoculations were current and their blood was free from the blacklisted diseases.[58] And in an effort to prevent anyone from slipping into the area unnoticed, Vancouver’s water authorities asked if the BCFB’s local rangers could, in addition to their regular duties, enforce the Sanitary Regulations on these two watersheds. Although the local district forester recognized the peculiar nature of this request, he supported it.[59] Similarly, the GVWB initiated a policy that required a special permit to access the water intakes, and it could be obtained from its secretary only after requisite bloodwork had been completed. Finally, for the several hundred lumberjacks employed by the Capilano Timber Company, the board numbered their health forms in order to subject their paperwork to particularly careful scrutiny.[60]

Cleveland’s remarkable work as chairman of the GVWB during its earliest years of operations attracted widespread attention, and in addressing the many inquiries he received about the quality of the board’s water supply he conveyed his mantra: what made it so pure was the virtual elimination of a human presence from these watersheds.[61] In responding to a letter from the president of the water supply and sewage board in Brisbane, Australia, for example, Cleveland explained, “Our water is obtained from mountain streams in almost completely unoccupied territory and no filtration or other treatment is required.” [62] Likewise, when the City of Ottawa’s water authorities asked Cleveland about this same subject, he replied, “No filtration, sterilization or other treatment of the water is required since the watersheds, with one exception, are practically immune from habitation.” [63] In responding to a similar inquiry from the mayor of Seattle, Cleveland explained his rationale for prohibiting human access to the Capilano and Seymour watersheds as much as possible. This decision, he outlined, “rests generally … on the belief that regardless of the extraordinary advances made in recent years in the treatment of water by filtration and sterilization no water supply is quite so good nor quite so safe as that which, due to freedom from occupation on the watershed, requires no treatment.” [64]

And pity the fool who challenged the quality of Vancouver’s water supply, such as E.W. Bacharach, a salesman for a filtration equipment-maker in the Deep South. Bacharach was presumably making a cold call when he wrote Cleveland in early 1928 to explain that he had seen a story in the local Mississippi papers about Vancouver’s decision to begin purifying its water. Cleveland roared that nothing could be further from the truth. The city was most definitely not “contemplating any steps toward filtration,” Cleveland declared indignantly, and added that “its water supply is taken from mountain streams and is of such a character that at present neither filtration nor sterilization is required nor so far as we can see is likely so to be.” [65]

Acutely aware that Vancouver’s pure water supply had become arguably its most important identifying feature, local boosters and media outlets alike imbued the mission of protecting it with such import that they characterized the Water Board as the hallowed guardian of this natural bounty and Cleveland as its mighty leader. From the outset, these groups entered into a remarkable alliance with the board and its chairman, making certain that everyone understood that it was no run-of-the-mill municipal body charged with mundane administrative tasks. Rather these officials were responding to a noble calling with a higher purpose. “The members of the Water Board are the trustees of the people of Greater Vancouver in the matter of water supply,” the Daily Province declared in February 1926. Its work was considered so important that the province’s leading papers offered their readers practically daily coverage of the board’s every move, and the reports were unquestioningly sympathetic.[66]

It was hardly surprising, then, that Cleveland played the lead role when a new menace appeared to challenge the purity of Vancouver’s cherished water supply. Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) was a dominant tree species in the forests that covered the Capilano and Seymour River valleys. Frequently attaining heights of well over 100 feet and diameters of three to four feet, and supporting branches of shiny, dark green needles, its aesthetically pleasing appearance was a major reason these watersheds were considered so splendid. Western hemlock is vulnerable to enemies, however, including the hemlock looper (Ellopia somniaria Hulst). The insect lays its eggs most often on the underside of hemlock needles in the late summer or early fall, and when the caterpillars hatch late the following spring, they begin feasting on the foliage. By late summer they are ready to pupate, and emerge as moths a few weeks later. The looper is always present in the forest, but occasionally its numbers spike and infestations result; these conditions leave the trees with a “yellowish-red and scorched appearance.” Generally, the only trees that die are those that are repeatedly attacked, while the survivors experience seasons of minimal growth.[67]

In 1929, the looper had been detected in several areas of concern for British Columbians, and unprecedented measures had been taken to deal with it. An outbreak along the Indian River on the north shore of Burrard Inlet (at Indian Arm) had been identified in the spring of that year. It threatened the vitality of the hemlock near a prominent summer lodge and had thus set off alarm bells for its owners. In an effort to stop the epidemic in its tracks, the inn’s proprietors cooperated with the BC Forest Branch and Canada’s local forest entomologists to conduct the province’s first experimental use of aircraft to dump chemicals on forest insects; at this time Canada was a world leader in this technology.[68] Then, in October 1929, George R. Hopping, the dominion’s forest entomologist on the file, reported that he had discovered an equally serious looper outbreak in the Seymour River valley. His intention was to review the situation with Cleveland in order to develop a strategy for tackling it.[69]

Meetings were held over several months to discuss ways of dealing with all the Lower Mainland’s bug problems, and during these sessions Hopping revealed some interesting information. He reported that, for a number of reasons, the Indian River site was best suited to conducting another experiment in aerial “dusting” (the chemicals were dusts and not in liquid form at the time) in 1930. In addition, the cost of any other operation of this kind would have to be borne by the government that had jurisdiction over the land that was infested. If the Water Board hoped to bomb its looper epidemic with poisons, it would have to foot the bill. At the same time, Hopping emphasized that the looper outbreak might subside on its own because of the increasing presence of parasites that were feasting on the pupae. “While they may control the outbreak in the course of another year or two,” he pointed out, “this cannot be depended upon.” [70]

The Water Board was adamant that it could not simply sit around hoping that Mother Nature would alter the balance between prey and predator in this instance, and for a surprising reason. Predictably, the Water Board’s primary concern was, as always, protecting the purity of the water supply. If the looper’s depredations caused major death among the hemlock, it would dramatically increase local erosion and water turbidity and also create a fire hazard, which could exacerbate these problems. The Water Board also had an equally pressing concern: it was imperative to safeguard the very idea that the water remained pure. Its members feared that the city’s residents would be most disturbed if they saw hemlock trees dying around their majestic water reservoir without any action being taken to counter it. “Should the Looper show up on lower levels down the [Seymour] creek,” the board’s representative asserted, “public opinion will possibly subject the Board to criticism unless some advance is made against the inroads of the insect.” [71]

The board typically deferred to Cleveland to make decisions and then simply rubber-stamped them, and in this instance he embraced the latest tool for managing insect infestations; it was also the most toxic solution possible to this problem. In early May 1930, Hopping issued an update on the situation. He described how the threat posed by the looper on the Seymour had grown because it had reached the dam and all indications pointed to it moving swiftly down the canyon that season. Although this area was below the intake on the Seymour watershed (i.e., erosion would not be an issue), Hopping stressed that the hemlock in this area were in danger of dying. If they did, it would create a fire hazard for the 60-inch wooden conduit that ran from the dam’s intake to the distribution mains lower down the mountain. Hopping added that the area, despite its steep slopes, could be dusted by plane and he practically guaranteed that doing so would “save the timber.” [72] Cleveland thanked Hopping for framing the issue in these terms—depicting human intervention as all that was needed to preserve the hemlock in the Seymour valley. Doing so provided Cleveland with just the fodder he needed. He relayed Hopping’s views to the board at a meeting in mid-May, during which the board authorized him to deal with this looper infestation “in the way that to him seems best under all the circumstances.” [73] Within a few weeks, Cleveland had negotiated a contract with a private airplane firm and purchased enough dust to carry out the mission. The board agreed to cover its $6,000 cost.[74]

Figure 4

Although few photographs of the aerial dusting of the Seymour River survive, this rare image captures one of the aircraft as its drops its payload of toxic calcium arsenate over the looper-infested hemlock (Courtesy of Natural Resources Canada).

The board also tacitly accepted the project’s most astounding aspect. Three aircraft worked in concert on 19 June to deposit 16,000 pounds of calcium arsenate on a swath of the infestation in the Seymour Canyon that measured roughly 2.5 miles long and about 0.5 miles wide (figure 4). Although most of the operation occurred on the portion of the watershed that was downstream from the reservoir, the planes also dumped the toxin on the very area that the Water Board had long prided itself on protecting most effectively—the crucial zone around the dam and the intake located in it. This was the area from which Cleveland had most aggressively aimed to eliminate any human presence, and yet now he was blithely championing coating it in a poison that was known to be toxic to humans.[75] Moreover, Cleveland later admitted that the only reason the looper-infested trees north of the dam, which covered the watershed that drained directly into the reservoir, were not dusted that season was the “crookedness and narrowness of the valley,” conditions that left “little room for an aeroplane to work.” [76]

And herein lay the extraordinary irony of the situation. During all discussions on the looper outbreak in Seymour Canyon, Cleveland, whose life’s work had become preserving the purity of Vancouver’s water supply, had uttered not one word of caution about the potential hazards posed by dumping tons of toxic chemicals in this watershed in general and around the intake on the Seymour in particular. Moreover, the only official to raise such a concern was George Hopping, the dominion entomologist and strongest local supporter of bombing the looper with lethal dust at this time. In November 1929 he had asked the head of forest entomology in Canada, James Malcolm Swaine, about “the possibility of poisoning [the] water supply by dusting.” Swaine admitted that this was “an important question upon which we have at the moment no information,” but he promised to review the German literature on the subject and consult Frank T. Shutt, the dominion chemist, for advice.[77] Shutt openly admitted that, without “particulars as to the topography and character of the watershed and types of trees,” he had no idea whether aerial dusting the Seymour Canyon would poison it. His hunch, however, was that it would be fine. Swaine concurred and quickly dismissed any concerns in this regard.[78] With that, the matter was dropped and never mentioned again.

Although some might argue that faith in dilution factors and dose-response models would have likely elided concern over the spraying, the evidence does not support this view. In addition to the information presented in the text, the simple fact is that the Canadian entomologists were warned by those who had been experimenting with this type of work to protect those who handled the poisons—advice the dominion’s officials repeatedly ignored. Not surprisingly, the pilots who flew the missions were coated in the arsenical dusts and got sick as a result. Moreover, Canadian officials noticed immediately after they began conducting their own projects that, time and time again, animals that were exposed to the poison died soon thereafter. The deadly effects of the dust on local fauna were observed even though officials showed no interest in gauging the collateral damage their projects were causing. Incidentally, BC’s Health Act required Vancouver’s water supply to be analyzed each year to demonstrate it was safe for drinking. Although the test checked for a wide range of potential contaminants, it did not do so for arsenic.[79]

Instead of expressing unease about the very notion of dumping deadly toxins anywhere near Vancouver’s supply of drinking water, the attention of all concerned was firmly fixed on celebrating what was seen as the dusting project’s smashing success in preserving the purity of the contents in the Seymour reservoir. Hopping surveyed the scene in mid-summer and excitedly reported to Cleveland that the operation had been “an unqualified success. I think that now we can definitely say that the stand which was dusted is definitely out of danger.” [80] Cleveland ran with this news to the Water Board, reporting on the “successful results of the airplane dusting of Seymour Watershed.” [81]

What he failed to mention was another consideration that Hopping had conveyed: all indications suggested that the insect epidemic would have died out on its own. “If the infestation had been allowed to run its course,” Hopping contended shortly after the operation’s conclusion that “the parasitism … should have reached 50% next year.” [82] In other words, the dusting operation on the Seymour had probably been completely unnecessary, a fact that Cleveland later openly admitted.[83] Such considerations were immaterial, however. What mattered most in this instance was that the public had seen Cleveland and the Water Board as having taken decisive action to sustain the aesthetically pleasing appearance of the hemlock in the Seymour River basin.

* * *

The dust had barely settled on the aerial campaign against the hemlock looper in the Seymour Canyon when another ode to the Water Board appeared in the local press. Tellingly entitled “Guarding Vancouver’s Pure Water Supply,” the piece emphatically argued that the sole means of realizing this goal was to eliminate humans from the watersheds that fed the city’s mains; their very presence was considered a plague. “Greater Vancouver today stands unique in regard to its water supply,” the article proudly declared. “Unlike the bulk of eastern cities, the water here is distilled in Nature’s resort. No chlorine or disinfectant makes it distasteful. Pure at the source and uncontaminated through its flow, it runs pure in the tap of the consumer,” it continued. “To attain it Vancouver had to start with the great advantage of mountains. No river sources this in which cities farther up are emptying their sewage. Up among the clouds the icy and turbulent mountain streams, and clear, calm lakes are far above human contamination.” [84] The images that accompanied the piece and displayed the lakes and treed slopes that cupped them demonstrated that “nature clothes Greater Vancouver’s water resources in a garment of beauty.” Despite protests, the article stressed that the Water Board was completely justified in declaring that “the public must be kept out of this vast area for its own good.” To deal with the handful of humans who would unavoidably enter these regions, the board had drawn up stringent regulations that required them to obtain a string of certificates attesting to their health. “No trespassers!,” the article declared in publishing the warning that greeted visitors. “No one is allowed within the Seymour and Capilano watersheds except after having undergone a rigid physical examination—and then only by special permit. Hunting, fishing and hiking,” the story added, “are strictly prohibited within these areas.” In summing up the situation, the Sun reminded its readers about the immaculate state of the terrain in the watersheds that had been transferred to the Water Board’s authority. Although it was “only a short distance from one of Canada’s greatest cities, the [watershed] reserve is a wilderness. An Eden that is practically uninhabited by humans.”

Curiously, at the same time the article ignored the dangers posed by the local non-human denizens, choosing instead to describe how the abundant fauna that inhabited these wilderness areas would live carefree lives because they were secure in the knowledge that humans were nowhere to be found. “Here the odd salmon leaps unharmed,” the piece explained, and “the occasional bear wanders at will and the deer is safe from man’s murderous impulses. Birds trill unafraid.” The article was silent about the maladies that these fish and animals harboured in their bloodstreams and wastes they discharged into and near the water that Vancouverites consumed, untreated no less. Clearly, creatures in the natural environment could not possibly require health certificates or blood tests to verify their purity. They were presumably untainted as long as no human fingerprints were on them.

The first few decades of Vancouver’s management of its drinking water is thus a tale that draws equally from the wells of urban and environmental history, and sheds new light upon each. The city’s drive to provide what was arguably North America’s purest water was led by its elites and fully supported by the local media, who saw achieving this aim as an essential element in allowing Vancouver to take its rightful place as one of the continent’s premier metropolises. This endeavour entailed manipulating nature, and doing so came at virtually no cost to local economic development. Although the leaders of this movement initially made only limited progress because their city lacked relative political weight, by the 1920s it exercised significant power in the province and, facing virtually no opposition to its agenda, made enormous headway. In the historiography of municipal water works and supplies, Vancouver stands as unique in its selective adaptation of technology, some of which it eagerly adopted while others it rejected outright.

All the while, the city declared with increasing vigour that its water supply remained pure and unsullied because it originated in “wilderness,” despite all the evidence of human activity in the area. Although Vancouver’s boosters were hardly the only ones to hold this paradoxical view of nature in the period under examination, the capstone chapter in this story—the dumping of tons of deadly chemicals in the Seymour canyon—provides a potentially jarring reminder of the dangers inherent in having done so.[85]

Appendices

Acknowledgements

Although I take full responsibility for any errors or omissions in this article, I would like to thank those groups and persons who contributed to it. I am grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, which granted me a Standard Research Grant back in 2010 for my larger project, entitled “Eradicating Bugs for Business and Beauty: Canada’s Pioneering Efforts to Combat Forest Insects with Chemicals, 1910–1930.” Many devoted and helpful archivists and librarians across the country have assisted me in conducting the research for the larger project in general and the BC portion of it in particular. These include all the folks at Library and Archives Canada, Natural Resources Canada in BC (especially Linda Brown and Jeannette Lum), the City of Vancouver Library, the BC Provincial Archives, and BC’s Ministry of Forests (especially Terri Clark). In addition, Erikka Luebbe and Jennifer Kitching at the British Columbia Legislative Library were most helpful in responding to my requests for assistance. The same is true of the librarians at the Iowa State University of Science and Technology. Back at Laurentian University in Sudbury, a string of gifted research assistants has assisted me in this undertaking. They include Nicholas McMullen, Michael Commito, Rick Duthie, Jackson Pind, and Sandra Siren. In addition, Scott Miller has recently proven invaluable in providing me with help.

Biographical note

Mark Kuhlberg is a full professor of history at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario, and is director of its MA History/maitrise en histoire programs. His expertise is the history of Ontario’s forests in particular and Canada’s in general. He has published many articles and two books. His first, One Hundred Rings and Counting (UofT Press 2009), chronicles the remarkable history of Canada’s inaugural forestry school during its first century. His second book, In the Power of the Government (UofT Press 2015), traces the birth and early development of Ontario’s pulp and paper industry. Mark spent twenty seasons in the silviculture industry in northern Ontario and Alberta and continues to be actively involved in contemporary forestry issues. He is still waiting for his call up to the Toronto Maple Leafs, and in the meantime is biding his time coaching his kids’ hockey teams and flooding the local outdoor rink.

Notes

-

[1]

J.E. Armstrong, Vancouver Geology, (Vancouver: Geological Association of Canada—Cordilleran Section, 1990), 15–18.

-

[2]

Various authors have demonstrated that water is an abstract concept whose meaning has changed throughout the ages. For example, J. Linton, What Is Water? The History of a Modern Abstraction (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010), 3, pithily explains that “water is what we make of it.” Similarly C. Hamlin, A Science of Impurity: Water Analysis in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), demonstrates that water purity was never an objective concept and its meaning was also relative to time, place, and perspective. When Vancouver’s boosters spoke of pure water, they were expressing a view that reflected their contemporary circumstances and values, whereby water that originated in the non-human world exemplified purity.

-

[3]

W. Cronon, “The Trouble with Wilderness, or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, ed., 69–90 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996). This subject is also addressed in note 8.

-

[4]

For one example of many, see A. MacEachern, Natural Selections: National Parks in Atlantic Canada, 1935–1970 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001).

-

[5]

Urban History Review 44, nos. 1–2 (Fall/Dpring 2015/2016); C. Otter, “Cleansing and Clarifying: Technology and Perceptions in Nineteenth-Century London,” Journal of British Studies 43, no. 1 (2004): 48–64; M.V. Melosi, The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 107; H. Platt, Shock Cities: The Environmental Transformation and Reform of Manchester and Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); M.C. Boyer, Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983); D.E. Burnstein, “Progressivism and Urban Crisis: The New York City Garbage Workers’ Strike of 1907,” Journal of Urban History 16, no. 4 (1990), 386–423. In addressing this subject, some authors have highlighted the role women played in urban environmental movements: for example, see M. Flanagan, “The City Profitable, the City Livable: Environmental Policy, Gender, and Power in Chicago in the 1910s,” Journal of Urban History 22 (1996): 163–190.

-

[6]

O. Temby, “Environmental Nuisances and Political Contestation in Canadian Cities: Research on the Regulation of Urban Growth’s Unwanted Outcomes,” in Urban History Review 44, nos. 1–2 (Fall/Spring 2015/2016): 5.

-

[7]

J. Tarr, “The Metabolism of the Industrial City: The Case of Pittsburgh,” Journal of Urban History 28 (2002): 511–545; A. Hurley, Environmental Inequalities: Class, Race, and Institutional Pollution in Gary, Indiana, 1945–1980 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); V. Been and F. Gupta, “Coming to the Nuisance or Going to the Barrios? A Longitudinal Analysis of Environmental Justice Claims,” Ecological Law Quarterly 24 (1997): 1–56; L.W. Cole and S.R. Foster, From the Ground Up (New York: New York University Press, 2001); T. Lambert and C. Boerner, “Environmental Inequity: Economic Causes, Economic Solutions,” Yale Journal of Regulation 14 (1997): 195; K. Cruikshank and N.B. Bouchier, “Blighted Areas and Obnoxious Industries: Constructing Environmental Inequality on an Industrial Waterfront, Hamilton, Ontario, 1890–1960,” Environmental History 9, no. 3 (2004): 466.

-

[8]

For example, see Melosi, Sanitary City.

-

[9]

Electoral History of British Columbia, 1871–1986 (Victoria: Elections BC, 1988).

-

[10]

D. Worster, Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West (New York: Pantheon, 1985), is the nascent and epic work on the impact water management on shaping the pattern of population growth in North America. More recent accounts that address this subject in strictly urban settings include J.A. Tarr, The Search for the Ultimate Sink: Urban Pollution in Historical Perspective (Akron, OH: University of Akron Press, 1996); Tarr, “The Metabolism of the Industrial City”; K. Foss-Mollan, Hard Water: Politics and Water Supply in Milwaukee, 1870–1995 (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2001), 2, who argues that “the ways in which an urban water supply is regarded by those in control of its purification and distribution can reveal much about local attitudes towards a city’s individuals, companies and manufacturers”; A. Keeling, “‘Sink or swim’: Water Pollution and Environmental Politics in Vancouver, 1889–1975,” BC Studies 142/143 (Summer/Autumn 2004): 69–101; M. Dagenais and C. Durand, “Cleaning, Draining, and Sanitizing the City: Conceptions and Uses of Water in the Montreal Region,” Canadian Historical Review 87, no. 4 (December 2006): 621–651; Cruikshank and Bouchier, “Blighted Areas and Obnoxious Industries.”

-

[11]

Numerous studies have analyzed how those who sought to cleanse urban environments during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries zealously adopted the latest technology in an effort to realize their aims. For example, Otter, “Cleansing and Clarifying,” examines this phenomenon in London during the nineteenth century.

-

[12]

R. White, The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995); D. Schneider, Hybrid Nature: Sewage Treatment and the Contradictions of the Industrial Ecosystem (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011); L. Nash, “The Changing Experience of Nature: Historical Encounters with a Northwest River,” Journal of American History (March 2000): 1600–1629; M. Gandy, Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002); S. Kheraj, Inventing Stanley Park: An Environmental History (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2013); D. Macfarlane, “‘A completely man-made and artificial cataract’: The Transnational Manipulation of Niagara Falls,” Environmental History 18, no. 4 (October 2013): 759–784; Cruikshank and Bouchier, “Blighted Areas and Obnoxious Industries.”

-

[13]

E. Nicol, Vancouver (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1978), xii; M.W. Andrews, “The Best Advertisement a City Can Have: Public Health Services in Vancouver, 1886–1888,” Urban History Review/Revue d’histoire urbaine 12, no. 3 (1984): 19–27; Andrews, “Sanitary Conveniences and the Retreat to the Frontier: Vancouver, 1886–1926,” BC Studies 87 (1990): 3–22; Jamie Benedickson, The Culture of Flushing: A Social and Legal History of Sewage (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2007), foreword, and chaps. 3, 7, and 9. An overview of the development of public health services across the nation can be found in C. Rutty and S.C. Sullivan, This Is Public Health: A Canadian History (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 2010).

-

[14]

M.W. Andrews, “The Emergency of Bureaucracy: The Vancouver Health Department, 1886–1914,” Journal of Urban History 12, no. 2 (February 1986): 131–155; Andrews, “Best Advertisement,” 19–20.

-

[15]

The standard work in this field is M. Valverde, The Age of Light, Soap and Water: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885–1925 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991).

-

[16]

City of Vancouver Archives (hereafter CVA), MSS54, 504-D-1, file 230, Greater Vancouver Water District, 1923–1925, “Vancouver Water Supply and Sewerage Disposal,” in Vancouver, British Columbia: Canada’s Pacific Gateway (Vancouver: Civic Federation of Vancouver, 1938).

-

[17]

L.P. Cain, “Water and Sanitation Services in Vancouver: An Historical Perspective,” BC Studies 30 (Summer 1976): 27–43; Andrews, “Best Advertisement,” 20–23; R.A.J. McDonald, Making Vancouver: Class, Status, and Social Boundaries, 1863–1913 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1996), 78.

-

[18]

Vancouver Advertiser, 5 January 1887, cited in Andrews, “Best Advertisement,” 19.

-

[19]

Cain, “Water and Sanitation Services,” 27–33. Both the Capilano and Seymour Rivers are often referred to in the contemporary maps and literature as creeks, but for consistency they will be called rivers in this article. In addition, Lake Coquitlam was tapped to provide its eponymous municipality and New Westminster with water, but it did not have the same “purity profile” as the Capilano and Seymour Rivers.

-

[20]

G. Wynn and T. Oke, eds., Vancouver and Its Regions (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1992), 17–37 and 117–118; Cain, “Water and Sanitation Services,”; Andrews, “Best Advertisement,” 20–24.

-

[21]

Benedickson, Culture of Flushing, chap. 9.

-

[22]

Cain, “Water and Sanitation Services,” 32–3; “Expert Favors Water Tunnel,” Vancouver Daily Province (hereafter VDP), 6 July 1927.

-

[23]

“Greater Vancouver Board Plans Water Supply for 3,000,000 People,” VDP, 26 June 1927.

-

[24]