Abstracts

Abstract

In 1912 Nova Scotia was the second province in Canada to adopt a town planning act. Just three years later, the province substantially revised its act under the guidance of Thomas Adams, town planning advisor for the Commission of Conservation. The article examines the context within which Nova Scotia adopted and then overhauled its early planning legislation. While Canadian planning history generally credits Adams with rewriting the legislation, the article documents the mechanisms through which key local actors drove provincial policy. Changes to provincial legislation in Nova Scotia in 1915 reflected the confluence of national interests, international town planning expertise, and local reform agendas.

Résumé

En 1912 la province de Nouvelle-Écosse fut la deuxième au Canada à adopter une loi de la planification municipale. Seulement trois ans plus tard, la province révisa substantiellement sa loi sous la direction de Thomas Adams, le conseiller de la planification municipale pour la Commission de la conservation. L’article examine le contexte dans lequel la Nouvelle-Écosse adopta et révisa sa première loi de la planification. Alors que l’histoire de la planification a Canada attribue à l’expert international Adams la réécriture de la loi, notre article suggère que des acteurs locaux efficaces facilitèrent le changement de politique dans la région. Les changements aux lois provinciales en Nouvelle-Écosse en 1915 reflètent une confluence de facteurs contextuels dont les intérêts nationaux, les experts internationaux de la planification urbaine, et les objectifs mis en avant par réformateurs locaux.

Article body

Town Planning: An Idea Is Born

Modern town planning was born in Canada during the Progressive Era (ca. 1890 to 1920). Concerns about the problems of cities had become the subject of discussions in men’s clubs and women’s groups across the country. The “long crusade to purify city life”[1] had commenced in earnest. Reformers described town planning as part of a progressive solution to urban problems related to poor housing, sanitation, and moral failures.

From 1896 to 1910, powerful forces pushed for beautification of civic centres as local leaders sought to make Canadian cities seem cosmopolitan.[2] Some cities established guilds or leagues committed to beautification and advocating projects of civic grandeur.[3] In 1905, for instance, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the Board of Trade formed a citizens’ committee (which by 1907 became the Civic Improvement League) to push for improvement.[4] Inspired by the City Beautiful movement in the United States, the idea of planning monumental and memorable civic centres suited the boosterism of the times.[5] Local entrepreneurial and professional elites pursued strategies and advertizing campaigns to ensure that cities grew quickly by attracting immigrants and industries.[6] Such activities fuelled speculation in land that burned across western Canada until 1913.[7]

Progressives began promoting town planning in Canada as early as 1905, when projects such as Letchworth Garden City took shape in Britain.[8] In 1909, the Canadian government created the Commission of Conservation, headed by Clifford Sifton, to lead Canada in efforts to ensure the conservation of resources.[9] The commission hired Charles Hodgetts as medical officer. Hodgetts promoted planning extensively in the period from 1910 to 1914, seeing it as essential to improving the health of urban centres.[10] Like other medical experts of his era, Hodgetts believed that planning offered useful tools for improving urban life and municipal management.

Following adoption of town planning legislation in Britain in 1909, British ideas proved increasingly popular in Canada. The commission and other organizations sponsored lecture tours by prominent British authorities and planners to disseminate scientific approaches to town planning.[11] Town planning promised to apply the principles of scientific management to reform urban conditions. Early in the 1910s, Canadian provinces began to pass legislation to enable town planning. New Brunswick moved first, passing an act in April 1912, followed in May 1912 by Nova Scotia and in 1913 by Alberta.[12] Only three years later, in April 1915, Nova Scotia adopted a new town planning act. This article explores the history of that abrupt transition, the characteristics of the legislation passed, the motivations of the actors involved, and the context within which the acts were adopted.

While planning history has generally credited the international town planning expert Thomas Adams, town planning advisor to the national Commission of Conservation, with almost single-handedly writing and rewriting legislation in Canada in the late 1910s, a review of events in Nova Scotia reveals the catalytic role played by local reformers eager to see town planning implemented as a means to improve the city of Halifax. Little has been written about the early history of town planning in Nova Scotia, with the 1912 act often overlooked in discussions of reform during the era.[13] Both the 1912 and the 1915 acts featured noteworthy innovations in town planning. Although the bills failed to produce the desired results—that is, town planning schemes did not result—they reflected the political, social, and professional concerns of the times.

In 1913 Sifton and Hodgetts at the commission began trying to hire an expert in town planning.[14] Adams arrived in Canada in fall of 1914—two years after Nova Scotia adopted its first planning act. Adams, a British planner who helped implement the 1909 British Town Planning Act through his work for the Local Government Board, was judged the best candidate.[15] Hodgetts and his colleagues described Adams as the “highest authority” on the topic of town planning.[16] Canadian reformers advocating town planning were delighted with Adams’s arrival because they saw expert knowledge as essential to urban transformation.[17]

What role did Adams play in revising Nova Scotia’s legislation? According to his biographer, Adams took the lead in revising Nova Scotia’s “unwieldy and irrelevant” 1912 legislation and substituting his own model planning act in its place.[18] The next sections of the article examine the role of international experts and local reformers in some detail to consider the local dynamics at play in legislative development and change in Nova Scotia. It briefly reviews the character of the legislation to identify the implications of the revisions. While Adams clearly lent weight to the process of revising the act and provided direction for the text, local reformers were pivotal creative agents who initiated and facilitated the effort to develop and adopt town planning legislation in ways not previously documented.

Nova Scotia in the 1910s

While most of the country crested the wave of immigration between 1896 and 1913, the Maritimes were “scarcely warmed by the boom.”[19] The population growth and inflation in land prices that hit the west bypassed Nova Scotia. The largest city in the region, Halifax, was increasing in population, but not as quickly as other cities in Canada: its size ranking was steadily dropping.[20] Halifax had a history of economic strength during wartime, as its harbour accommodated convoys and its shores hosted troops and those provisioning the war effort. During times of peace the city languished, as its economy relied on shipping, resources, and finance.[21] The region industrialized during the mid-nineteenth century as tariffs supported domestic industries in areas such as sugar, cotton, and steel production.[22] By late in the nineteenth century, however, the centre of economic gravity in Canada moved west to where land was opening and migrants were flowing. Industrial enterprises began leaving Nova Scotia, lured by access to markets and capital in central Canada. The end of protective tariffs and rail subsidies helped to undermine the early economic advantages eastern Canada enjoyed. By the 1910s, power brokers in the east were feeling increasingly marginalized and anxious to take steps to improve regional prospects.[23] Eastern cities, like those in other parts of Canada, were struggling to cope with problems of disease and poverty associated with urban living.

The reform movement got off to an early start in Halifax. Organized groups—from temperance societies, to the Anti-Tuberculosis League, to the Board of Trade, to the Local Council of Women—pushed local government to beautify, clean up, and otherwise reform the city.[24] In November 1905 the Board of Trade formed a committee on civic improvement.[25] By 1907 the committee had transformed into the Civic Improvement League (hereafter called the League): it would remain a vital force in the city until 1917.[26] The League included influential professionals, businessmen, and community leaders, largely from the wealthy south end of the city. [27] The opinion leaders of the League—Robert McConnell Hattie (journalist), Reginald V. Harris (lawyer), Frederick H. Sexton (principal of the Technical College), William Dennis (publisher of local newspapers), and George Everett Faulkner (insurance broker, president of the Board of Trade in 1908,[28] Liberal member of the Legislative Assembly from 1906 to 1920, speaker of the house in 1910–1911, and minister without portfolio from 1911 to 1920)[29]—set about publicizing the need for beautification and other improvements in the city. In March 1908, on returning from a trip to England, Sexton delivered a lecture on “The Picturesque Suburb,” wherein he emphasized the importance of planning, not simply beautification.[30] Beginning in July 1910 Harris wrote a regular column—under the nom de plume Wilfred Y. De Wake—on civic affairs, government reform, and tenement housing in the Halifax Herald and Evening Mail.[31] Extensive newspaper coverage of League activities promoted the message.

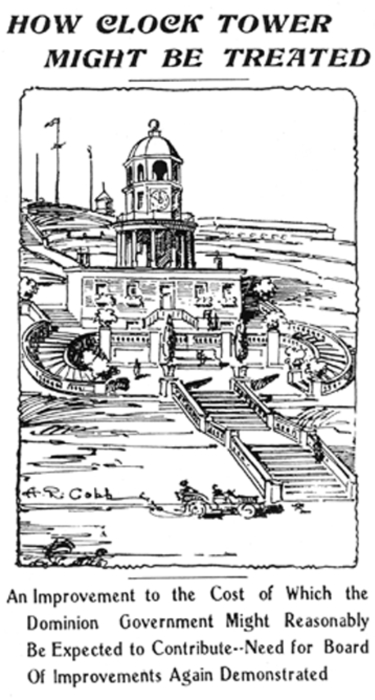

Along with national agents such as the Commission of Conservation and the governor general, the League helped bring American and British experts to Halifax in 1910 and 1911. John Nolen, an influential landscape architect from Massachusetts, visited in September 1910 to talk about planning and beautification.[32] In October 2010 Henry Vivian, a member of Parliament from Britain who was involved with the Local Government Board administering the 1909 town planning act there, delivered a blistering speech suggesting that the slums of Halifax were far worse than those found in Britain.[33] Vivian’s call for town planning and a code of bylaws for minimum standards of health invigorated the reform movement in its efforts to initiate action in Halifax. Shortly thereafter the League released illustrations by local architect Andrew Cobb for improvements to parts of the city centre, which members suggested could be “part of a comprehensive city plan.”[34] It approached city council in December 1910 to appoint a commission to investigate developing a comprehensive plan for Halifax.[35]

Lobbying continued through 1911. Hattie gave a speech in January 1911 arguing again for a comprehensive plan.[36] For a week in March 1911 the League presented a conference on civic awakening and uplift with speeches by John L. Sewall from Boston’s civic uplift campaign.[37] A motion passed at the concluding session called for a comprehensive city plan for Halifax.[38] In 1911 Reginald Harris successfully ran for council.[39] The fall of 1911 witnessed concerted efforts to lobby Halifax city council to prepare a plan. Two weeks of articles titled “City Planning” ran in the Daily Echo.[40]

On 14 November 1911 after Hattie read a paper on comprehensive planning at a League meeting at the Board of Trade, the session ended with a resolution to ask city council to create a Board of Improvements to begin a planning scheme.[41] To continue the momentum, the Daily Echo published Hattie’s paper over several days.[42]

As members of the League pulled out all the stops in trying to convince a recalcitrant Halifax city council to hire staff and begin planning, the Union of Canadian Municipalities adopted a resolution at its annual meeting in November 1911 which a local paper published: “That in view of the rapidly increasing growth of our cities, and the grave inconvenience resulting from haphazard division of real estate, the various Provincial Governments and urban municipalities be most earnestly urged to pass such legislation, and to make such arrangements, as will result in the immediate making, adoption and prosecution of a city plan for each growing community, governing the lines of expansion and developments.”[43]

British landscape architect and planner Thomas Mawson addressed city planning on 28 November 1911,[44] and local papers continued to run features related to town planning through the end of the year.[45] None of the myriad efforts seemed to inspire Halifax council to act. Refusing to give up on their ambitions, local reformers began developing other strategies to encourage town planning. Creating appropriate legislation to reform local government and enable town planning was high on their agenda.

The first town planning act in Nova Scotia passed the provincial legislature in May 1912,[46] the same month as a bill reforming Halifax council’s governance structure to a Board of Control system.[47] Hattie, Harris, Faulkner, Cobb, and others associated with the Civic Improvement League and the Board of Trade played key roles in bringing the legislation forward.[48] Local actors had already begun taking steps to initiate town planning in Nova Scotia two and a half years before the commission appointed a town planning expert to do the same. In the process of forging legislation appropriate to what they saw as local needs in Halifax, these local reformers pioneered new approaches for the fledgling discipline.

Act 1: Town Planning Act, 1912

Thomas Adams’s biographer, Michael Simpson, detected a strong adherence to British precursors in early planning acts in Canada: “The all-conquering British influence led to three provincial planning acts—in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (1912) and Alberta (1913). Slavish copies of the British act of 1909, adopted hastily and without adequate means of implementation, they were failures.”[49]

Such analysis minimized textual differences between the acts and cast little light on why the early legislation had limited impact. This section briefly examines the provisions of the 1912 Nova Scotia act and contrasts elements with the British version.[50]

Table 1 provides a simplified overview of some differences between the town planning acts discussed here. The 1909 act adopted in Britain[51] permitted towns to prepare planning schemes for areas of new or pending development: that is, it focused on suburbs.[52] It facilitated a highly ordered and bureaucratic process whereby the central government’s Local Government Board (and its staff) would be involved at all stages of enabling, approving, regulating, and arbitrating town planning schemes.[53] An extensive document laying out many details of how town planning would work, the act specified that local authorities might reclaim a share of improved land values resulting from a town planning scheme, and provided mechanisms for compensation for those whose properties may be adversely affected by certain elements of a scheme.

Table 1

Comparing early legislation on some important features

Rather than a slavish imitation, the 1912 Nova Scotia act was a significantly stripped-down and inverted version of its British counterpart. Some clauses from the British act appeared with slight modifications, but most of the earlier text was omitted. Dispensing with the centralized authority of the British system, the act empowered any city, town, or municipality to prepare a town planning scheme for any land in the course of or likely to be used for development. The law thus permitted local government considerable autonomy in local planning, requiring recourse to the province in limited cases where schemes might cross political boundaries or where disputes about compensation could not be resolved. The act remained silent on many matters, including roles for planning experts or recapturing a share of increased property values. In setting out the purpose of planning, it added text about providing for traffic, which had not appeared in the British law.[54] In many ways it was a minimalist bill providing local governments with the legal mechanisms to begin modest efforts at planning urban extensions.

The year 1912 brought considerable change to Halifax municipal council as a Board of Control system—with controllers acting as municipal administrators—supplanted ward politics. Robert Hattie and William Dennis were elected as reform members of council,[55] where they joined Reginald Harris, who was on the new Board of Control.[56] Council minutes[57] and Hattie’s papers[58] indicate that Alderman Hattie tried repeatedly but unsuccessfully to convince the city to hire a professional planning expert. As chair of Council’s Civic Improvement Committee,[59] Hattie presented reports and motions to council in late 1912 and early 1913 to borrow funds to hire a city planning expert: although his motions won simple majorities, three times they suffered defeat under council’s requirement for a two-thirds majority on some monetary measures.[60] In opposing Hattie’s motion to borrow $4000 to hire a city planning expert, Alderman Whitman argued that a city planner would recommend many changes and incur expenditures at a time when the city’s finances were in a poor position and when western cities were struggling with the results of such extravagance.[61]

By early 1913 Halifax reformers realized that their political and legislative efforts to get the city to begin planning were not working. In January Hattie gave another address on the need for town planning.[62] On 18 February 1913 George Faulkner introduced amendments to the 1912 town planning act in the legislature.[63] As presented for first reading, the bill proposed additions to allow any city, town, or municipality by majority vote to create a committee or commission to prepare a plan and to provide funds for hiring experts and staff. These clauses sought to address the super-plurality requirement that Halifax council used to deny Hattie’s motions. Other proposed sections would have required areas in the fringe around incorporated towns or cities to submit a plan for survey and subdivision to the city or town. The bill would have prevented building lots from being sold or deeds registered without such approval. For unknown reasons the bill appears not to have progressed to third reading.[64] By spring of 1913 the reformers’ tactics were shifting to a new course of action.

In this period Raymond Unwin visited Halifax to present at the Union of Nova Scotia Municipalities conference and to share his advice on town planning with those interested.[65] By mid-1913, Hattie was corresponding regularly with Hodgetts at the Commission of Conservation. The commission was then trying to hire Thomas Adams and was developing a model town planning act for the provinces.[66] Hodgetts first presented the draft model act during the May 1914 National Town Planning Conference in Toronto. Adams offered comments on the draft, comparing it with the 1909 British act. Cautious about appearing overly critical, Adams noted differences in land use laws and political systems between the countries, and volunteered to work with the committee to rewrite the legislation.[67]

Following the national conference, Hodgetts toured several provinces to promote the model act. In a letter dated 2 June 1913, Hodgetts acknowledged the frustration that Hattie faced in trying to get Halifax to adopt a town planning scheme under the act, and confirmed the need for further action.[68] Halifax Board of Control submitted town planning regulations to council in early 1914, setting out procedures to be used in developing a town planning scheme.[69] Events may not have been transpiring quickly enough to satisfy local reformers, however, as they continued to consider revising the law. Hodgetts journeyed to Halifax in July 1914 to attend the Anti-Tuberculosis League Conference. On 14 July 1914 the Civic Improvement League of Halifax organized a meeting with him: its advertisement promised a “Conference with Dr. Hodgetts Re: Town Planning” to discuss remodelling the 1912 act.[70] At the end of the month Hodgetts met with the city planning committee to discuss the draft act and to suggest a review committee to revise the 1912 law.[71] By this point, local reformers had committed to overhauling their original legislation.

On behalf of the League, Hattie followed up on the issue over the next months, becoming the lead local agent pressing for a new act. Along with Faulkner, Hattie formed a board of prominent reformers and political leaders to revise the law. As Adams assumed the role of town planning advisor in late July 1914, Hattie’s correspondence with Hodgetts gave way to a regular exchange of letters and draft legislation with Adams. Hodgetts soon left Canada to join the war effort, giving Adams the opportunity to revise the commission’s model town planning act.[72] The new version became the basis of later discussions between Adams, Hattie, and the local group working towards a draft law.

As reformers in Halifax worked on considering revisions, Adams reported on planning in Canada to his colleagues in Britain. Writing about Nova Scotia’s 1912 legislation, Adams said, “Up to the present no action has been taken in Nova Scotia, but the powers given under the provincial Act and the Halifax City Charter, together form the most advanced legislation in the Dominion.”[73] Despite his praise for the original legislation, he added that he planned to spend a week in Nova Scotia in February 1915 to discuss amendments to the act.

Generating local momentum for change, in late 1914 and early 1915 Hattie corresponded with municipal and provincial politicians in Nova Scotia on the need for amendments to the 1912 act.[74] Following up on the motion at the city planning board the previous July, Hattie requested permission from Halifax council to form an inter-governmental committee comprising provincial politicians, provincial officials, municipal politicians from Halifax and Dartmouth, and local community groups to address the need for an amended act. Although many of Hattie’s early efforts with Halifax council had failed to gain traction, this request was approved. Once the inter-governmental committee formed in 1915, Hattie invited prominent political leaders from the neighbouring town of Dartmouth to join. In February 1915 the League’s newsletter reported that the League had requested Adams to visit Halifax to advise them on the new legislation.[75] The committee worked closely with Adams and Hattie to draft what would become the 1915 Town Planning Act.

Influencing the form and language of the new Nova Scotia law was a high priority for Adams. He had mentioned his intention to travel to the province during his first speech in Canada.[76] Because not all drafts circulated between Adams and Hattie survived, the initial proposals from the local committee are not known. While the local group had originally anticipated amending the 1912 legislation, Adams favoured replacement with a new version adopting the principles he intended to embed in the model act.[77] Rather than sending Hattie amendments to the old act, Adams dispatched an entirely new draft. This may have caught Hattie and his committee off-guard, as on 15 February 1915 Adams apologized for having sent the new draft without first discussing why the 1912 act should be completely scrapped. He wrote to Hattie, “I think the best thing to do would be to drop the Act of 1912 and to consider the new Act on the lines of the revised Act prepared by the Commission of Conservation. One important reason for this is to secure uniform legislation throughout the Dominion and to point to Nova Scotia as the example which other provinces should follow.”[78]

Adams’s letter and notes to Hattie included a lengthy critique of the 1912 legislation. Adams discussed some minor word-choice issues, but his major concern dealt with the power that the earlier act granted to a municipality. He specifically criticized section 3: “Any city, town or municipality within the meaning of this Act may prepare such a town planning scheme with reference to any land within or in the vicinity of their area.”[79] Adams wrote that giving the municipality the power “to prepare a town planning scheme instead of getting permission to prepare it from a higher authority must be a serious weakness in carrying out a scheme,” especially for areas outside a city’s political boundaries. His roots in the British system of highly centralized control were clear. Adams reminded Hattie that under the British legislation, municipalities must ask permission to adopt plans from the higher level of government. Adams recommended changing section 9, which gave the municipality the power to set procedural regulations, as “procedure should either be determined by parliament or it should be provided in the Act that it will be determined by an impartial authority outside the municipality.”[80] The degree of local autonomy permitted municipalities in the original Nova Scotia legislation troubled Adams who hoped to create a coherent planning system across Canada through ensuring that provinces had the tools necessary to impose appropriate standards, procedures, and expertise.

Adams wanted to ensure this was the best possible law. He explained to Hattie, “I am very anxious to get Nova Scotia to adopt legislation which can be referred to as an example to the other provinces.”[81] On 12 March 1915, he wrote, “If Nova Scotia adopts that Act which I recommended I propose to recommend the Commission of Conservation use it as their model.”[82] While Adams agreed to make some adjustments in the drafts to suit Nova Scotia concerns and conditions,[83] he was pleased with the legislation crafted and used it to inform the model town planning act released soon after. Adams remained involved as the bill made its way through various readings, corresponding with Hattie to craft amendments and recommend changes to sections he found wanting. Most but not all of Adams’s suggestions were accepted. In setting out the language of the legislation, Adams took full advantage of the opportunity Nova Scotia offered to advance his aim of supplanting incongruent legislation with something that better approached his ideals for comprehensive and compulsory planning implemented by experts.

Adams visited Halifax in late February through early March 1915 to finalize the wording of the act and promote the legislation in the community. With considerable haste the group finished the bill for the provincial legislature and arranged first reading of the legislation on 23 March 1915. Hattie assured the Nova Scotia legislators that the act “will put Nova Scotia in advance of any other province or country in the matter of Town Planning Legislation.”[84] By 23 April 1915 the new Town Planning Act passed third reading and shortly became law. Adams issued a press release on 27 April 1915 to proclaim the significance of the event: “A Town Planning Act has been passed into law in Nova Scotia which will revolutionize the methods of developing real estate and controlling building operations in that province. The Act is to a large extent compulsory and is in advance of anything of the kind in the world.”[85]

Nova Scotia represented an early and important victory for Adams and the Commission of Conservation in transforming the planning system in Canada. The model town planning act Adams subsequently promoted in 1916 reflected the Nova Scotia experience. Adams retained a strong connection to Halifax, returning in 1918 to assist with replanning parts of the city extensively damaged by the 1917 explosion of a munitions ship in Halifax harbour.[86]

Act 2: Town Planning Act, 1915

Nova Scotia’s 1915 act repealed the earlier legislation and reproduced many sections from the 1909 British law. Much longer than the 1912 version and replete with detail and minutiae, the 1915 legislation yielded several critical innovations. First, it made planning compulsory in Nova Scotia, giving cities and towns three years to produce town planning schemes. It required local governments to appoint town planning boards, employ town planning experts, and develop town planning bylaws. It also set up mechanisms for financing local planning. Second, it made planning comprehensive by enabling planning schemes to cover any land, not simply areas for new suburbs. Once approved, plans would be binding on future development. Third, it replicated the British system of centralized and expert-led control to create potential for standardization. A provincial commissioner (working with a town planning controller) would establish procedures and regulations, review bylaws to decide whether to approve them, and manage any disputes. In providing language to deal with the use of buildings and land, the law reflected growing concerns about protecting residential uses that would in the next decade lead to widespread zoning bylaws.[87]

While his biographer described Adams’s Canadian planning acts as timid and disappointing,[88] the Nova Scotia legislation took radical steps for its time. In 1910, at the National Garden Cities and Town Planning Association conference in London, Adams had defended the 1909 British law against criticisms that it was not compulsory, by arguing that local governments would soon realize the benefits of town planning and not need to be forced to plan.[89] By 1915 he had decided that local government had to be required to plan. As the first legislative effort to compel planning, the Nova Scotia act caught considerable international attention. Even the 1919 revisions to British town planning law followed Nova Scotia’s lead in making planning compulsory and allowing plans to cover any land.[90]

The interest of the province in enabling such radical legislative change remains murky. Hattie, Faulkner, and others in the League took the opportunity to promote a local agenda: that is, they sought to employ provincial powers to force the City of Halifax to adopt a town planning scheme. Having tried but failed to achieve their aims through creating a simple system empowering local government and getting League members elected to municipal office, they were persuaded to apply more robust mechanisms. Reformers needed the province because it had the power to adopt the rules and regulations to enable or require local planning. The records discovered portrayed the province as a compliant if somewhat silent partner in the process. The planning legislation seemed to have stirred little interest and no opposition from other members of the legislature. The records of proceedings in the legislature offer few clues as to political reactions.[91]

Passage of the 1915 act represented the zenith of early efforts to establish town planning in Nova Scotia. Although legislators appreciated Adams’s and Hattie’s assurances that Nova Scotia was leading the country in adopting the most modern and powerful town planning legislation in the dominion, if not the world, political commitment to planning proved less clear and sustained. Cities and towns did not rush to comply with the law, and the province did little to implement it. Halifax appointed Hattie to its new Town Planning Board in 1916,[92] but the board appears to have had relatively little impact. Hattie corresponded with Adams about a housing survey in 1916,[93] but it is not clear whether it was conducted. With Canada at war until late 1918, the priorities of political leaders and local reformers were increasingly focused on supporting the war effort. By 1917 the Civic Improvement League dissolved amidst shattered aspirations.[94]

Based at least in part on advice from Adams,[95] the 1915 act was amended in 1919 to extend deadlines to give municipalities six years to prepare planning bylaws or schemes and to expand bylaw powers to enable classification of land uses (zoning): “In 1921 the Union of Nova Scotia Municipalities appointed a committee to consider and review the regulations contained in the Act, as the City of Halifax had charged that the regulations were difficult to comply with and burdensome. Nothing more was heard of the committee and for more than a decade, nothing was said of town planning at any of the annual conferences of the Union.”[96]

The Commission of Conservation was dissolved in 1921, leaving Adams without work and the national town planning mission suspended.[97] As happened in other parts of the country, many Nova Scotia municipalities adopted zoning bylaws to regulate land use during the 1920s but they did not prepare comprehensive plans.[98] Despite a decade of concerted efforts by local reformers to create the conditions to get Halifax to plan, no comprehensive plan resulted.[99] The province repealed the legislation and amendments in 1939, ending the early experiment in compulsory planning.

Critical Reviews: Lessons Learned

Governments develop legislation within the context of a particular place and a time. Investigation of the early town planning legislation in Nova Scotia provides some insights into the factors that account for the timing, content, and fate of the 1912 and 1915 bills. Understanding the setting within which the laws were developed, the actors involved in producing them, and the concerns addressed by the legislation helps to fill in pieces of the puzzle that is the history of early town planning in Canada. The analysis suggests that previous assessments of early town planning legislation in Canada made inaccurate generalizations about the nature and significance of the Nova Scotia laws. The 1912 law paid modest homage to earlier British legislation but set a new course for locally based town planning activities with limited requirements for bureaucratic oversight. The later 1915 bill reprised some elements of the British law but charted new directions as well. It represented the epitome of planning aspirations for the time and became a model for others to emulate.

Moreover, while many discussions of early town planning lionized recognized experts such as Thomas Adams, Raymond Unwin, and Charles Hodgetts, close inspection of the history of early legislation in Nova Scotia exposes the critical role played by local actors in creating a supportive setting to generate legislation, in crafting laws to address local concerns, and in working through the political system to get laws adopted. Local reformers and international experts needed each other. Without people such as Robert Hattie, Reginald Harris, William Dennis, and George Faulkner, Thomas Adams could not have moved his professional agenda forward. Hattie and his colleagues in the Civic Improvement League were critical catalysts in igniting and sustaining political and business interest in planning. Learning from these successes in Halifax, Adams took the Civic Improvement League national in 1916.[100] The Halifax experience had a significant influence on Adams’s ideas of how to promote and practise planning in Canada.

Local reformers greased the wheels, permitting Adams to attach his new act to the legislative cart in Nova Scotia. Without Thomas Adams, Hattie and Faulkner might have attempted a less radical revision to the 1912 law. The international credibility Adams brought helped to sell the idea of compulsory and comprehensive town planning but also turned Nova Scotia away from a system that offered local government considerable autonomy to shape the future.

In the end, neither bill achieved its aims. The province lacked the inclination and resources to implement most provisions of the 1915 act.[101] Nova Scotia’s bold experiment with town planning legislation ultimately failed and largely faded from memory. It would be many decades before Halifax City Council developed the political will to hire planning experts; it finally adopted a comprehensive plan in 1945 under revised legislation. Those advocating town planning, however, learned lessons that they would contemplate for decades to come: that bold ambitions and planning legislation are necessary but not sufficient conditions to engender town planning.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Alan Ruffman, Leah Perrin, and staff at the various archives and libraries consulted for this research. Howard Epstein, Brant Wishart, and reviewers of a previous version of the paper provided extremely valuable feedback.

Biographical notes

Jill L. Grant is a professor in the School of Planning, Dalhousie University.

Leifka Vissers is a city planner and graduate of the Dalhousie Master of Planning program. She works as a public servant in Vancouver for the Government of Canada.

James Haney is an urban and rural planner in Alberta and graduate of the Dalhousie Master of Planning program.

Notes

-

[1]

Paul Rutherford, “Tomorrow’s Metropolis: The Urban Reform Movement in Canada, 1880-1920,” in The Canadian City: Essays in Urban and Social History, ed. G. A. Stelter and A. F. J. Artibise (Ottawa: Carleton Library Series, 1984), 437.

-

[2]

Michael Simpson, Thomas Adams and the Modern Planning Movement: Britain, Canada and the United States, 1900–1940 (London: Mansell, 1985), 73–74.

-

[3]

Walter Van Nus, “The Fate of City Beautiful Thought in Canada, 1893–1930,” in Stelter and Artibise, Canadian City: 167–186.

-

[4]

Andrew Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City’: The Halifax Civic Improvement League 1905–1949” (MA thesis, Saint Mary’s University, 2000), 23.

-

[5]

Van Nus, “Fate of City Beautiful.”

-

[6]

Alan F. J. Artibise, “In Pursuit of Growth: Municipal Boosterism and Urban Development in the Canadian Prairie West, 1871–1913,” in Shaping the Urban Landscape: Aspects of the Canadian City-building Process, ed. G. A. Stelter and A. F. J. Artibise, 116–147 (Ottawa: Carleton Library Series, Macmillan, 1982).

-

[7]

Alan F. J. Artibise, “The Urban West: The Evolution of Prairie Towns and Cities to 1930,” in Stelter and Artibise, Canadian City, 138–164.

-

[8]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 73.

-

[9]

David Lewis Stein, “The Commission of Conservation,” special seventy-fifth anniversary issue, Plan Canada (July 1994): 55.

-

[10]

Jeanne Wolfe, “Our Common Past: An Interpretation of Canadian Planning History,” special seventy-fifth anniversary issue, Plan Canada (July 1994): 12–34.

-

[11]

C. Schmitz, “The Movement in Canada,” Town Planning Review 3, no. 3 (1912): 218–219; Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City,’” chaps. 1–2.

-

[12]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 75.

-

[13]

Neither Nicholson (“Dreaming ‘the Perfect City’”) nor Roper, who both wrote at length about the reform movement in Halifax in this period, acknowledged the existence of the 1912 town planning act. Henry Roper, “The Halifax Board of Control: The Failure of Municipal Reform,” Acadiensis 14, no. 2 (1985), 46–65.

-

[14]

Alan H. Armstrong, “Thomas Adams and the Commission of Conservation,” in Planning the Canadian Environment, ed. L. O. Gertler, 10–20 (Montreal: Harvest House, 1968); J. David Hulchanski, “Thomas Adams: A Biographical and Bibliographical Guide,” in Papers on Planning and Design (Toronto: Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Toronto, 1978); David Lewis Stein, “Thomas Adams: The Father of Canadian Planning,” special seventy-fifth anniversary issue, Plan Canada (July 1994): 14–15.

-

[15]

Charles Hodgetts to Robert M. Hattie (2 June 1913), file 46, vol. 2898, MG1, Robert McConnell Hattie Papers (hereafter Hattie Papers), Public Archives of Nova Scotia (hereafter PANS), Halifax, Nova Scotia. Fortunately for those interested in planning history in the region, Hattie donated an extensive collection of correspondence and other materials from this period to the Public Archives of Nova Scotia: few other materials shed as much light on planning history in the province in this era. See also, Commission of Conservation, “Town Planning Adviser to the Commission of Conservation,” Conservation of Life 1, no. 2 (1914): 27–28.

-

[16]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 77.

-

[17]

Rutherford, “Tomorrow’s Metropolis,” 445.

-

[18]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 85.

-

[19]

Ibid. 71.

-

[20]

Larry D. McCann, “Staples and the New Industrialism in the Growth of Post-Confederation Halifax,” in Stelter and Artibise, Shaping the Urban Landscape, 116–147.

-

[21]

Judith Fingard, Janet Guildford, and David Sutherland, Halifax: The First 250 Years (Halifax: Formac Publishing, 1999).

-

[22]

Ibid., 92–98.

-

[23]

Ibid., 117–137.

-

[24]

Judith Fingard, The Dark Side of Life in Victorian Halifax (Potters Lake, NS: Pottersfield, 1989); Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City.’”

-

[25]

“Citizens Ready to Beautify Halifax”, Evening Mail, 9 November 1905, 5.

-

[26]

Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City.’”

-

[27]

Ibid., 29–30.

-

[28]

The front page of the Daily Echo on 8 March 1908 referred to George Faulkner as the president of the Board of Trade.

-

[29]

S. B. Elliott, “George Everett Faulkner,” The Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia, 1758–1983: A Biographical Directory (Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia, 1984), 68.

-

[30]

“The Picturesque Suburb,” Evening Mail, 4 March 1908, 6.

-

[31]

Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City,’” 36, reported that Harris contributed over 170 columns on civic issues. Examples included columns titled “Halifax Uplift” in the Evening Mail, 15 September 1911, 20 September 1911, 26 October 1911.

-

[32]

“Landscape Artist Sees City in Rain,” Evening Mail, 20 September 1910.

-

[33]

“Let’s Look Ahead and Avoid Costly Blunders” and “What Shall Halifax Do To Be Saved?” Evening Mail, 28 October 1910.

-

[34]

“How It Might Be,” Evening Mail, 26 November 1910.

-

[35]

“Civic Improvement League Talked Over Matters Which Will Go to the City Council,” Evening Mail, 6 December 1910.

-

[36]

Evening Mail, 18 January 1911. Cited in Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City,’” 40.

-

[37]

“The Civic Uplift Opens Tomorrow with Addresses by John. L. Sewall, of Boston,” Evening Mail, 4 March 1911. See also Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City,’” chap. 2.

-

[38]

“The Aim of Halifax to Make It a Splendid ‘City Beautiful’ Discussed at Civic Revival Meeting,” Evening Mail, 11 March 1911.

-

[39]

Roper, “Halifax Board of Control,” 55.

-

[40]

“City Planning,” Daily Echo, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 13, and 14 November 1911.

-

[41]

“Civic Improvement League Meeting,” Daily Echo, 15 November 1911.

-

[42]

“Planning for the Future,” Daily Echo, 20, 21, 2, 23, and 25 November 1911.

-

[43]

“City Planning: Some Projects in the Air That Lend Significance to This Movement for Halifax,” Daily Echo, 14 November 1911.

-

[44]

“All Must Join in Beautifying the City,” Daily Echo, 29 November 1911.

-

[45]

The Daily Echo published some of Cobb’s illustrations of possible improvements: see “How the Extension of Morris St. Could Be Made Great Feature,” 25 November 1911; “North End in Need of Park,” 30 November 1911; “What About the Ferry Landing?,” 7 December 1911; “How Clock Tower Might Be Treated,” 11 December 1911; “Suggested Bridge across Arm,” 13 December 1911.

The Daily Echo also ran editorials arguing the benefits of planning: for instance, see “Hundred Thousand Dollar Mistakes Show Necessity for Comprehensive City Plan,” 2 December 1911; “City Planning and the Children,” 14 December 1911.

-

[46]

Nova Scotia, Statutes, An Act Respecting Town Planning, 2 Geo. V, Chapter 6, passed 3 May 1912.

-

[47]

Roper, “Halifax Board of Control.”

-

[48]

Although few documents from this period have been located, in 1944 Hattie wrote that the league had played the principal role in getting the law introduced. Robert M. Hattie, “Planning Submission,” 1944, file 11, vol. 2899, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[49]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 75.

-

[50]

Detailed analysis of the New Brunswick and Alberta acts would be required to determine whether Simpson’s critique is relevant for them. That is not possible here.

-

[51]

Great Britain, Acts of Parliament, 9 Edw. 7, Chapter 44, 1909. Reproduced as Appendix A in E. G. Bentley and S. Pointon Taylor, A Practical Guide in the Preparation of Town Planning Schemes (London: George Philip & Son, 1911).

-

[52]

Sutcliffe suggested that the bill implemented the garden suburb idea as inspired by developments at Bournville and Hampstead Garden Suburb. Anthony Sutcliffe, “Britain’s First Town Planning Act: A Review of the 1909 Achievement,” Town Planning Review 59, no. 3 (1988): 289–303.

-

[53]

Nicholas Herbert-Young, “Central Government and Statutory Planning under the Town Planning Act 1909,” Planning Perspectives 13 (1998): 341–355.

-

[54]

Nova Scotia, Town Planning Act 1912, sec. 2.

-

[55]

“Standing Committees of City Council,” City Council, 1912–1913, file 27, vol. 2898, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[56]

Roper, “Halifax Board of Control.”

-

[57]

Halifax City Council, Council Meeting Minutes, 8, 23, and 28 January 1913, Halifax Municipal Archives (hereafter HMA).

-

[58]

Halifax City Council, “Order of the Day, ” 9, 23, 28 January, 6 February 1913, file 27, vol. 2898, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[59]

“Report of Civic Improvement Board,” 6 November, and “Report of Civic Improvement Committee,” 27 November 1912, file 32, vol. 2897, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[60]

City Council Minutes, 5, 19 December 1912, 9, 23 January 1913, HMA.

-

[61]

“Third Time of Asking for a City Planner,” newspaper clipping, 29 January 1913 (no source identified), file 29, vol. 2897, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[62]

Robert M. Hattie, “A Comprehensive Plan: The First Step in Civic Improvement” (paper read at public meeting under the auspices of the Civic Improvement League, Assembly Hall, Nova Scotia Technical College, 7 January 1913), file 35, vol. 2899, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[63]

Nova Scotia, Bill No. 3, “An Act to Amend Chapter 6, Acts of 1912, ‘The Town Planning Act, 1912,’” file 25, vol. 2899, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS. First reading 18 February 1913, second reading 20 February 1913 and sent to committee.

-

[64]

In personal communications (27 September 2011) legislative librarians at the Nova Scotia House of Assembly indicated that they were unable to locate further action on the bill after the law amendments committee reported back on 7 March 1913. The assembly was prorogued on 18 May without the bill receiving third reading. The librarians noted that records from the war years are incomplete but it does not appear that the amendments progressed further.

-

[65]

Mervyn Miller, author of Hampstead Garden Suburb (Stroud, Glouchestershire: Chalford Publishing, 1995), advised in a personal communication (27 July 2010) that The Record (Hampstead Garden Suburb) III, 6 January 1915, discussed Unwin’s trip of the previous year, which might suggest he visited in 1914. However, a summary produced by provincial staff indicate that the trip occurred in 1913. “History of Nova Scotia Planning Acts Prior to 1969,” n.d., Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations (hereafter SNSMR), http://www.gov.ns.ca/snsmr/muns/plan/pdf/historynsplanningactsprior1969.pdf.

-

[66]

Armstrong (“Thomas Adams,” 21) noted that the original model act, drafted by Jeffrey Burland, was influenced by American planning ideas.

-

[67]

Commission of Conservation, Report of Sixth Annual Meeting, 1915 (Ottawa: Commission of Conservation, 1915).

-

[68]

Charles Hodgetts to Hattie, 2 June 1913, file 46, vol. 2898, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[69]

“Town Planning Regulations,” City Hall (Halifax), 30 January 1914, file 15, vol. 2897, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[70]

Civic Improvement League, advertisement, “Conference with Dr. Hodgetts Re Town Planning Act,” 14 July 1914, file 35, vol. 2897, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[71]

“Report of City Planning Committee,” 30 July 1914, file 29, vol. 2897, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[72]

Commission of Conservation, Report on Fifth Annual Meeting, 1914 (Ottawa: Commission of Conservation, 1914).

-

[73]

Thomas Adams, “Housing and Town Planning in Canada,” Town Planning Review 6, no. 1 (1915): 20–26.

-

[74]

Robert Hattie draft letters to local political leaders, 15 February 1915, with attached draft act, file 25, vol. 2897, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[75]

“Nova Scotia Town Planning Act,” Civic Improvement League Newsletter, 15 February 1915, 1, file 15, vol. 2898, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[76]

Commission of Conservation, Conservation of Life 1, no. 3 (1914): 66–68.

-

[77]

Thomas Adams to Robert Hattie, 9 February 1915, file 35, vol. 2897, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[78]

Thomas Adams, letter and notes to Hattie regarding a visit to Nova Scotia and draft act, 15 February 1915 (hereafter Adams’s comments on draft act, 15 February 1915), file 36, vol. 2899, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[79]

Nova Scotia, Statutes, An Act Respecting Town Planning, 2 George V., Chap. 6, pages 112–117, (3 May 1912), Assembly of Nova Scotia, Halifax.

-

[80]

Adams’s comments on draft act, 15 February 1915.

-

[81]

Ibid.

-

[82]

Thomas Adams to Robert Hattie, 12 March 1915, file 36, vol. 2899, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[83]

Letter exchanges between Adams and Hattie between January and March 1915 show that Adams drafted language changes as Hattie alerted him to various issues of concern in Nova Scotia. For instance, Schedule A item 5 reflected local concerns about land use: “Prescribing certain areas which are likely to be used for building purposes for use for separate dwelling houses, apartment houses, factories, warehouses, shops, stores, etc.” Such language presaged the importance of zoning, which would come in the 1920s.

-

[84]

Robert Hattie, letter of transmittal regarding the 1915 draft act, 4 March 1915, file 36, vol. 2899, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[85]

Thomas Adams, “Nova Scotia Takes the Lead in Town Planning Law,” news release, 27 April 1915, file 36, vol. 2899, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS. The text was repeated in an article in Conservation of Life 1, no. 4 (July 1915): 95.

-

[86]

John Weaver, “Reconstruction of the Richmond District in Halifax: A Canadian Episode in Public Housing and Town Planning, 1918–1921,” Plan Canada 16 (March 1976): 36–47.

-

[87]

In the era discussed, the judicial approach was to restrict municipal powers (Howard Epstein, personal communication, 29 September 2011). By enabling town planning regulations and indicating that uses could be controlled the legislation gave local governments the ability to move towards zoning.

Armstrong, “Thomas Adams and the Commission,” 26, reported that Adams worked up a zoning by-law and draft official plan for Halifax in the months after the 1915 act passed, but these have not been located. Weaver, “Reconstruction,” noted that Adams helped craft the town planning scheme and by-laws for the reconstructed Richmond District in Halifax 1918, and this plan remained in effect until 1948.

After New York City pioneered the first US zoning by-law in 1916, many cities across the continent began to follow suit. Peter Moore, “Zoning and Planning: The Toronto Experience, 1904–1970,” in The Usable Urban Past: Planning and Politics in the Modern Canadian City, ed. A. F. J. Artibise and G. A. Stelter, 316–341 (Toronto: Macmillan, 1979).

-

[88]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 84.

-

[89]

Ewart Culpin, ed., The Practical Application of Town Planning Powers: A Report (Westminster: PS King and Son, 1910), 18.

-

[90]

S. D. Adshead, Town Planning and Town Development (London: Methuen, 1923), 165, 175.

-

[91]

Assembly of Nova Scotia, The Journals of the Debates and Proceedings of the Assembly of Nova Scotia, 1915–16 (23, 31 March, 8, 12 April 1915), 9–250, microfilm 3501, PANS.

-

[92]

City Council Minutes, 10 February 1916, 415, HMA.

-

[93]

Thomas Adams to Robert Hattie, 23 February 1916; Thomas Adams, “Memorandum regarding Proposed Housing Survey at Halifax,” 23 July 1916, file 45, vol. 2898, MG1, Hattie Papers, PANS.

-

[94]

Nicholson, “Dreaming ‘the Perfect City,’” 5.

-

[95]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 85.

-

[96]

SNSMR, “History of Nova Scotia Planning Acts.”

-

[97]

Simpson, Thomas Adams, 105.

-

[98]

See Moore, “Zoning and Planning; Walter Van Nus, “Towards the City Efficient: The Theory and Practice of Zoning, 1919–1939,” in Artibise and Stelter, Usable Urban Past, 226–246.

-

[99]

Plans for the Richmond District in 1918 were crafted under special legislation, not under the 1915 Act. Weaver, “Reconstruction.”

-

[100]

Adams’s biographer noted that Adams founded a national Civic Improvement League in 1916 but does not acknowledge any inspiration from the pivotal role of the league in Halifax in the period 1907 to 1915. Simpson, Thomas Adams, 81–82.

-

[101]

By 1919 the British had determined that many provisions of the 1909 act (on which much of the text of the 1915 Nova Scotia act was modelled) were unwieldy and had to be modified. Adshead, Town Planning, 163.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Jill L. Grant est professeure en planification urbaine à la School of Planning de Dalhousie University.

Leifka Vissers est une planificatrice urbaine diplômée du programme maîtrise en planification urbaine à Dalhousie University. Elle travaille présentement à Vancouver au sein de la fonction publique fédérale.

James Haney est un planificateur urbain et rural en Alberta, diplômé du programme maîtrise en planification urbaine à Dalhousie University.

List of figures

List of tables

Table 1

Comparing early legislation on some important features