Abstracts

Abstract

After the fall of communism in 1989, Romania, as others countries from Central and Eastern Europe, had to deal with its recent past marked by two dictatorships, one on the extreme right, the other on the extreme left. However, it seems that the post-communist society is rather preoccupied by the consequences of the communist regime than the fascist one. As the anti-communist narrative has become mainstream since the beginning of the 2000s, the victims of communist prisons received more and more attention. Several voices asked for the canonization of those prisoners that distinguished themselves for their belief. The Aiud “prison saints” are part of this current. Their stories are not simple and neither is the history: some of those who died in communist prisons were affiliated to the extreme right in the 1930s and the 1940s. While the Orthodox Church avoids to discuss their canonization, the new “saints” became the object of a popular devotion, which gathers together not only believers, but also representatives of the Church and the civil society. This article explores what the devotion for “prison saints” represents in the lived religion. Following the pilgrims to Aiud monastery and narratives concerning the “prison saints,” it appears that their veneration is not “natural,” but rather the result of a construction. As it turns out, lived religion is a vehicle for values diverging from the official democratic discourse.

Article body

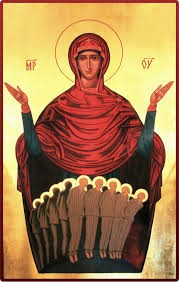

Since the early 2000s in Romania, a discourse about the “prison saints” has allowed for the open articulation of an anti-communist rhetoric. The expression refers to the former political prisoners who died during the most violent period of the communist regime, namely between 1948 and 1964. I heard for the first time about the “prison saints” from Aiud—a little town in Transylvania—during an interview carried out in May 2012 in Bucharest. My discussion partner, who I will here call Carmen, was a practicing believer in her fifties. While she was explaining to me how to use holy oil, Carmen mentioned in passing the existence of the Aiud “saints” (interview, 15 May 2012). She had gone on a pilgrimage to the little monastery in Aiud where she had obtained some holy oil from a vigil lamp that burns continuously there to lighten the relics. She believed that the oil could heal her illness and vaguely knew that the relics had been discovered in Aiud and belonged to persecuted persons. Finally, she took a little icon out of her purse, which showed the Mother of God with a group of people in prison uniforms who had luminous halos around their heads. She read aloud the inscription that accompanied the image: “The prison saints.” I then understood she was talking about the former political prisoners who died in the communist jail of Aiud; yet, the woman who was looking at the little icon did not know that the “saints” were political prisoners who died during the communist regime.

interview, a practicing believer, 15 May 2012C: I have a little icon from there, from Aiud. How do we say there…Aiud…I don’t know, I forgot…where they died…I forgot. (…) Look at the icon from there, the “Mother of God, the guardian of persecuted people,” the monastery the “Ascension of the Holy Cross” at Aiud. Look at it [the icon] I received it there with … [the holy oil].

MG: Do you mean the political prisoners?

C: Yes, exactly, this is what I wanted to say, but I forgot”

The woman’s lapse of memory first astonished me, probably because my initial training as a historian. On the spur of the moment, I thought that Carmen was probably somebody who was not interested in history. However, my curiosity was piqued again when I arrived, with some forty pilgrims, in Aiud in September 2012.[1] I discovered there a strange devotion: the pilgrims were invited to venerate as “relics” (moaste) the human remains of formers political prisoners found in a cemetery that had belonged to the Aiud political jail. As I was soon to find out, the devotion to Aiud “prison saints” tied together, in a complex way, history, memory, and religion.

Photo 1

The icon the “Mother of God, the guardian of persecuted people”. I received a similar icon at the Aiud monastery on September 29th, 2012. Carmen showed me the same icon during the interview.

This article explores what the Aiud “prison saints” represent both in the lived religion of the pilgrims—mainly women—and in the lived religion of the “carriers of the official religion,” that is nuns, monks, and priests.[2] As representatives of the Church, they interpret the dogmas and the official practices. In this way, they give birth to another form of lived religion that has often, in the eyes of pilgrims, the authority of an official religion. My aim here is not to discuss the opposition between lived and official religion, but instead to observe the relation between two types of lived religion from the standing point of a small phenomenon of devotion that emerged in post-communist Romania. Given that the devotion to “prison saints” is tied to a larger discussion, which concerns the Romanian post-communist civil society, I include among the “carriers of the official religion” religious spokesmen, but also pilgrim guides, historians, writers, philosophers, and journalists. They all share one thing in common, a self-victimizing discourse developed since the early 1990s (Conovici 2013: 121-122).

When I write about lived religion, I am not interested in doctrines but in understanding how religion is practiced, experienced, and expressed (McGuire 2008; Ammerman 2007, 2013; Orsi 2005, 1997) by lay people in everyday life and the spokesmen of the Church. Because the Orthodox Church does not recognize the devotion to the “prison saints,” I consider it as lived religion.[3] The veneration of Aiud “saints” began in the post-communist period, and was constructed through a post-communist image of the communist regime. However, the founding myth of this devotion refers to a more distant period: it refers to a history complicated by two dictatorships, one on the extreme right, the other on the extreme left. During the pilgrimage to the monastery in Aiud, the guides and the pilgrims did not share the same interest in the past. While the guides focused on history and memory, the women ignored the history and concentrated on the veneration of “relics.”

This double interest in the human remains discovered in a cemetery situated at the “Slaves’ Gully” in Aiud lead the sociologist Irina Stahl (2014) to notice that the “prison saints”—as Romanian saints—are caught between popular devotion and politics. However, Stahl’s inquiry—based mainly on the popular literature concerning the subject—does not question how the devotion for these new “saints” developed. The pilgrimage to Aiud monastery let me see the veneration of the “prison saints” in a slightly different light: their cult was not developed from the bottom up as usually happens, but rather was encouraged by the carriers of the official religion. Thus, the study of the devotion to the human remains exposed as “relics” at the monastery in Aiud is not without importance for the understanding of the evolution of the post-communist society. Since 1989, the stories about prisons and the victims of the communist regime have circulated in the media and have been part of a series of efforts at reinterpreting the past.

Let me begin my reflection with an excerpt from my fieldwork notes made during the pilgrimage to the monastery, the place where the “relics of prison saints” are exposed before I explore the significance of this devotion. My aim is to understand two main points: how lived religion circulates between pilgrims and the carriers of the official religion; and how the past is interpreted by pilgrims and carriers of the official religion in order to give meaning to their present experience.

1 The Monastery “the Ascension of the Holy Cross” (Schitul “Inaltarea Sfintei Cruci”)[4]

In the afternoon of September 29th, 2012, our bus stopped in front of a little building considered both memorial and monastery. Erected between 1992 and 1999, the building is found in a cemetery located in a poor outskirt of the town of Aiud. The place is known as “The Slaves’ Gully.” Here, the political prisoners who died during their detention in the first twenty years of the communist regime were allegedly buried anonymously. The building—marked by several crosses—commemorates the suffering of the prisoners and of the Romanian people under the communist regime.

Photo 2

The Aiud monastery (schit). The building erected in 1990s was firstly a commemorative monument. The photography shows the entrance in the church.

Photo 3

The Aiud monastery (schit). The entrance in the ossuary.

The building has two levels: at the first floor there is a little church, and in the basement one finds an ossuary. First, we visited the ossuary. At the end of the room, there was a big icon of the “Mother of God, the guardian of persecuted people,” the miniature copy of which Carmen showed me during the interview mentioned before. On both sides of the icon there were two window displays with many shelves exhibiting human remains. The broken bones demonstrated the violence of the communist regime, the guide said, but also their holy character: the bones still had the marrow and hair was still on the skulls or jaws. The monastery guide and our guide referred to the human remains as “relics.”

Photo 4

The ossuary of Aiud monastery.

Photo 5

The human remains of the former political prisoners exhibited at the Aiud monastery.

The women I was accompanying were amazed, less by the violence imposed on prisoners, than by the marrow and the hair. My travel companion showed me every bone with hair on it. While I was trying to hide my disgust, she watched with attentive amazement. Making our way to the church, she said that she had only one regret: because the “relics” were locked, she could not kiss them and feel their odour of sanctity. In the church, several stairs go down towards the altar. The walls were covered with the names of political prisoners, but nobody looked at them. The women rushed to kiss the icons. Back on the bus and on the way to another monastery, we passed by the Aiud prison. The guide showed it to us, but the women around me did not even turn their head. As Carmen who could not remember who were the persecutors, my pilgrim companions expressed no interest in the communist past.

2 The Particular Devotion to “Relics” of “Prison Saints” from Aiud

My field notes show my irritation caused by the women I met during the pilgrimage. At that time I could not understand why they were attracted to these human remains while paying no attention to the lives of “saints.” Usually, during pilgrimages, the women venerate relics and also the saints: they kiss the relics, read the lives of saints and talk about their miracles. In Aiud, the tie between “relics” and “saints” is missing: the women’s devotion takes a strange form, which concerns the human remains but not, so much, the “saints.” In order to understand this development, two episodes seem important to me: the change in the labeling of bones in 2001 and the “revelation of the ‘sanctity’ of the bones” in 2009.

The first episode took place in 2001 when the human remains discovered during the construction of the commemorative building were called “relics” for the first time in public. This marks a change in the perception of the human remains from Aiud. The official website of the Aiud monastery attributes this change to Justin Parvu (1919-2013)[5], who was then the abbey and the confessor of Petru Voda monastery, located in Moldavia.[6] Parvu was also a former political prisoner of the Aiud jail. During the inter-war period, he had been a member of the Legionary movement, an extreme right Romanian party. As late as 2005, he affirmed his sympathies for the extreme right openly.[7] I met Justin Parvu in 2012, one year before his death. At that time, he was considered as a charismatic confessor who was sought out by many believers for advice. His authority had been widely recognized in the last years when he was named honorary citizen of several towns, including Aiud in 2014. Several documentaries, which are presented during pilgrimages, relate his experiences in communist prisons and popularize his opinions about the “prison saints” and their “relics.”

While visiting the commemorative monument in Aiud in 2001, Parvu publicly referred to the human remains as “relics” instead of remains. On the same occasion, he proposed the establishment of a monastery in the cemetery of Aiud, which was opened in 2004. Parvu’s words had no immediate echo among believers; in fact, testimonies about miracles that appear shortly after the discovery of “relics” and delight the believers were late to manifest.

The second moment toward the “revelation of the ‘sanctity’ of the bones” took place in 2009 and it concerns the first miracle performed before an audience by the Aiud “relics.” The theologian and writer Danion Vasile (1974)—who is also a follower of Justin Parvu—relates that the relics revealed their holiness publicly for the first time on 19 March 2009 during a conference about the persecutions of Christians in the European Union held at the “Vesper” theatre in Iasi. The conference was part of a campaign lead by the Areopag Group whose aim was to disseminate information about the “prison saints” through conferences, publications, websites and pilgrimages. The group was created in October 2008, at the initiative of Danion Vasile with the blessing of Justin Parvu.[11] During his conferences, Danion Vasile would bring several “prison saints relics” from Aiud that he had received from Justin Parvu. By encouraging the circulation of “relics” from Aiud, Parvu sought to promote devotion to the “Aiud saints.”

Photo 6

The little reliquary, which contains the “relics” that sprang forth fragrant oil since 2009.

Danion Vasile remembered the conference from 19 March in Iasi as follows: at the end of the conference the participants prayed to the “relics,” which were placed in a little reliquary. While his colleague, Hrisostom Manolescu—an ordained monk—was holding the little reliquary in his hands, fragrant oil sprang forth from the “relics.” The miracle was showed to participants who took photos and filmed it. Bloggers in the room informed the Orthodox community via Internet about the Iasi miracle.[12] Since then, the “relics” of the “prison saints” from Aiud are said to have proved their powers on several occasions (Voicila 2012: 79-80). The testimonies about their miracles have been gathered in order to be published and attached to the file concerning the canonization of the “saints” by the Orthodox Church. Pilgrimages began to be organized to Aiud monastery on a more frequent basis. The number of people working to disseminate of the cult of the “prison saints” increased.[13] All of them are animated by anti-communist feelings and put the “victims” at the center of society in order to create what can be called “the new narration of the national past” (Assmann and Shortt 2012: 8), a narration that has, at its heart, the idea of martyrdom, suffering, and religion. This type of narrative is not isolated. It has been taken up and popularized by the media as well.

In Aiud, the Orthodox Church’s voice was absent. Officially, the Church does not recognize the human remains as “relics” because none of the “prison saints” have been canonized.[14] Given that many former prisoners had connections with the extreme right, one could imagine that their canonization could stain the image of the church. In practice the church takes part, discretely, in the development of the “martyr’s memoriae” (Brown 1981: 37).[15]

3 Devotion to the “Prisons Saints” and Lived Religion

The fascist past of several of the “prison saints” takes us to the problematic intersection of fascism, communism, and lived religion. My aim here is not to discuss the relation between fascism and communism (Tismaneanu 2013 [2012]; Furet and Nolte 2000 [1998]), but instead to try to understand how lived religion circulates between pilgrims and carriers of the official religion and how lived religion became a medium for the rehabilitation of a problematic past.

As I already remarked, both my observations and the literature concerning the “prison saints,” show that the chief architects of the elevation of the “prison saints” are the carriers of the official religion. They are helped towards their objective by the women pilgrims. For the first group, attached to the anti-communist discourse, the former political prisoners were “victims,” “martyrs,” and “saints.” The women value particularly, as I have shown, the “relics.” History, memory, and religion intermix in Aiud while an active group of actors (guides, priests, theologians, journalists, and writers) attempt to popularize the devotion to the “saints” in order to obtain their canonisation.

In order to understand the pilgrims’ behaviour, let me return to the miracle from the Iasi Theater in 2009 when the “relics” from Aiud revealed their “holiness.” Seen from the outside, this moment might seem strange. To understand it, it is important to follow the pilgrims’ logic: the women are particularly attracted to monasteries that have icons and relics reputed to perform miracles (Grigore, 2015). The stories about former political prisoners emphasised the suffering and the faith but lacked specific details. The suffering of the “saints” might impress the women, but it seemed less likely to awaken their devotion. Therefore, it is possible that the performance of a “public” miracle was necessary to convince them that the human remains were holy and had extraordinary powers. The fact that the miracle happened in front of a big audience, more than 500 people (Vasile 2012: 79), is not insignificant. It seems that it conferred credibility to the event and assured its rapid diffusion.

By insisting on miracles, the carriers of official religion stirred the interest of women for material religion and miracles. The women went in pilgrimages for spiritual benefits, but also to heal an illness or to insure a good future. “Relics,” which do not show a “sacred power,” do not figure into the women’s lived religion. This is maybe the reason why the guides and priests of Aiud monastery insisted on the special characteristics of the human bones—the marrow, the hair, or the blood marks. These particularities showed pilgrims the presence of the sacred in the human remains. Also, the decision that the carriers of official religion made to awaken the devotion of women for the Aiud “saints,” indicates that they had observed and understood the women’s lived religion so that they were able to take over their lived religion and give the pilgrims what they expected. The devotion for the “prison saints” was thus constructed backwards: there was no question to venerate first the “saints” and thereafter their “relics,” but an adoration of “relics” and not so much of the “saints.” What was important for women, during their pilgrimage, was the fact that the suffering in prisons created martyrs and “saints” and that their “relics” could help them overcome the problems of the present. In order to acquire access to the “relics,” the pilgrims listened to a story about the communist past that might one day find its place in the women’s lived religion.

The pilgrims had different attitudes toward the “relics,” and their positions toward the past were equally ambiguous. The women whom I met on pilgrimages mostly condemned the communist regime because any association with the communist past was socially unacceptable. At the same time, they also demonstrated feelings of nostalgia, regretting employment security, the facility to obtain housing, or the protection offered by the state (fieldwork note, 2nd October 2012). The women even showed understanding of the persecutors’ actions: “they did their job,” my travel companion said (fieldwork note, 29 September 2012). However, the sentiments of the carriers of official religion toward communism are maybe too clear: any opposition to communism was a heroic act regardless of the motivations that determined it. As victims of the communist regime, the “prison saints” are tied to the evolution of the image of communism after 1989. In the first decade after 1989 the communist period was ignored rather than discussed (Cristea and Radu-Bucurenci 2008; Conovici 2013; Marin 2013; Stan 2006). The interest in political prisoners also remained marginal, apart from associations of former political prisoners survivors and intellectual circles. Things began to change after 2000 when two institutions were created to investigate the communist past. Anti-communist speech became mainstream when the communist regime was officially condemned in 2006 (Cristea and Radu-Bucurenci 2008). The violence of the communist prisons was integrated into this discourse. The death of political prisoners in communist jails represented the proof of the criminal character of the communist regime.

It was in this context that the carriers of the official religion designated the people who died in communist prisons as martyrs and saints instead as victims. In this way, the hazy social memory of political prisoners was transformed into what the “expert of memory” Aleida Assmann (2006) has referred to as “political memory.” Such a memory is based on selection and exclusion (Assmann 2006: 216). The carriers of the official religion emphasized the suffering of political prisoners and generally avoided public talk about the political prisoners sympathies for the extreme right. A closer look at the narratives of the carriers of official religion about this subject changed gradually. For example, the “Christian intellectuals” (Stahl 2014: 94), who supported openly the canonization of several former political prisoners, avoided to talk about the “saints” thorny past in the first years of the Areopag Group campaign launched in 2008. Their approach visibly changed after 2012, as the devotion gained in popularity. The same group of “Christian intellectuals” did not hide—in their interviews, writings or documentaries—the affiliation of several Aiud “saints” to the extreme right during the inter-war period.[16] However, rather than discuss this problematic past, they prefer to establish a distinction within the image of the inter-war extreme right: those who followed political aims were sinful, but those who were attracted by the religious message and practices of the party could be considered heroes. They insisted that the Romanian extreme right was more a spiritual movement than a criminal one. After all, they said, the suffering in communist jails washed away their sins. Therefore, the “saints” could be canonized (Vasile 2014; Lavric 2014; Tudor, Conovici, and Conovici 2014; Hossu-Longin 2012). In this “cultural process of communism” (Mark 2010: 62), the “historical memory”— a recollected memory of those who did not participate in the events (Halbwachs 1997[1950]: 99)—provides the narratives. History adds the “scientific” proof to memory (Stan 2013: 113) through archive documents and human remains that demonstrate the cruelty of the communist regime and the suffering of former political prisoners.[17] In this case, history is not what Pierre Nora (1984: xix) calls analysis and critical speech, but rather a history that reuses in a scientific form the narratives of memory and offers monochromatic answers, with “no questions, no dilemmas, not doubts” (Cristea and Radu-Bucurenci 2008: 35). In order to legitimize their speech, the carriers of official religion “take over” the victims’ experience, the suffering of victims became their own suffering.

4 Conclusion

The complexity at work in this small phenomenon of devotion is linked to its character: the veneration of the Aiud “saints” is not “natural,” but the result of a construction, whose ultimate motivation is the canonization of several former political prisoners. Following the pilgrims and the carriers of the official religion, I observed how lived religion circulates between two groups of actors. One value—anticommunism—seems to link the carriers of official religion to the “prison saints” of Aiud. The women join in, but they are not so vocal, and may lack conviction. In this devotion the women have a passive role: they do not contribute to its construction, but to its consolidation. The devotion for “relics” of “prison saints” introduces in the lived religion of the pilgrims “saints” who are carriers of anticommunist values, obscuring the violent and oppressive nature of fascism. Thus, the lived religion of the carriers of the official religion and the women becomes a medium through which values of the extreme right enter everyday life.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

The travel agency leaflet marked with capital letters the following message for the pilgrimage to Aiud: “Come to pray and to bring your gratitude to Romanian saints martyrs who sacrificed themselves for the sins of our nation when the red beast tried to suffocate our Christian Orthodox belief. Come to Aiud!”

-

[2]

This article is based on fieldwork carried out in Romania in 2012. I use participant observation from pilgrimages, semi-structured interviews with believers in Bucharest, and literature about the Aiud “prison saints.”

-

[3]

For this reason, the terms of “prison saints,” “saints,” and “relics” will be always used in this article with quotation marks.

-

[4]

In Romanian, the word schit refers to a little monastic establishment, which is administrated by a bigger monastery. Because the pilgrims usually refer to the hermitage at Aiud as a monastery, I will designate the establishment at Aiud as monastery.

-

[5]

During his visit to the Aiud commemorative monument, Justin Parvu allegedly said: “I am afraid to tread on this ground, because it is filled with holy relics (Sfintele Moaste).” http://www.calvarulaiudului.ro/istoric.php, accessed on 20 February 2015.

-

[6]

http://manastirea.petru-voda.ro/?s=Justin+Parvu, accessed on 24 February 2015.

-

[7]

Justin Parvu was the founder of the Petru Voda monastery. He dedicated it to the “prison saints” whose affiliations to the extreme right is not hidden by the community of monks.

-

[8]

Since the 1960s, the Romanian extreme right has been studied by Romanian and foreign scholars (Iordachi 2003: 431). For more details about the Romanian extreme right, see Fischer-Galati 2007, 1971; Ornea 1995; Volovici 1991; Weber 1966; Shafir 1985; Iordachi 2013, 2010; Clark 2015.

-

[9]

The members of this party were known as “legionaries.”

-

[10]

Until September 1940, general Ion Antonescu occupied a marginal position on the political scene. Because he disagreed with King Carol II on important themes such as foreign politics and the measures against the Iron Guard, Antonescu had fallen into disfavour with Carol II.

-

[11]

The campaign was organized by Danion Vasile (director of Aeropag Publishing), Gigel Chiazna (web-master of the website sfintii-inchisorilor.ro), Laurentiu Dumitru and Razvan Codrescu (the representatives of Christiana Publishing and the magazine Puncte cardinale [“Cardinal Points”]), Romeo Petrasciuc (director of Agnos Publishing), Florin Buliga (web-master of the website ortodoxradio.ro), Claudiu Tarziu (director of the magazine Rost), Razvan Bucuroiu (director of the national TV channel TVR2 and director of the magazine Lumea Credintei [“The World of Belief”]), and Mircea Platon (historian). http://www.sfintii-inchisorilor.ro/argument/, accessed on 10 March 2015.

-

[12]

“Appologeticum,” “Saccsiv,” and some Orthodox forums such as “Crestinortodox.” Since 2014, the videos that show the Iasi “miracle” on 19 March 2009 were removed from these websites without any explanation. It is also the case for the links offered by Irina Stahl (2014: 95) in her article about Romanian saints. However, the capture of this moment can be still watched on youtube.com in August 2015 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJCRm4wC7e8, accessed on 1st August 2015).

-

[13]

After this moment, many other people worked toward the popularization of the “prison saints,” such as the priest of the Aiud monastery, Augustin Varvaruc, the priest and the community of nuns of the Diaconesti monastery (Moldavia), the actor Dan Puric, the historian Cristian Troncota, the doctor Pavel Chirila, and the philosopher Sorin Lavric.

-

[14]

In the Romanian Orthodox Church, the canonization means the official recognition of the holy character of a person and its inscription in the religious calendar. The new saint receives the right to be represented in an icon and to have a personal prayer (acatist). In Eastern Christianity, the canonization does not have an elaborated legal form as it is the case in the Catholic Church. The canonization is usually based on popular practices: stories about the life of the future saint, miracles performed in life or after death, incorruptible human remains (however, this rule is not mandatory, it is usually noted that the bones have the odor of sanctity), martyrdom in the name of Christian belief and, particularly, a distinct recourse to God’s grace (Radu 1986: 806-811).

-

[15]

The official journal of the Patriarchate, Lumina (The Light), publishes once in a while bibliographic records of Orthodox priests arrested during the communist period. Since 2015, Basilica Travel, the travel agency of the Patriarchate, introduced in its schedule of pilgrimages in Maramures and Transylvania a stop to the Aiud monastery. In September 2014, the Romanian Orthodox Church opened a new monastery and a study center of martyrology near the Aiud monastery.

-

[16]

In 2013, the documentary The Prisons Saints directed by Denisa Morariu and presented by an important private TV channel (Antena 3) at prime time discussed in a positive manner the affiliation to extreme right of several “prison saints,” whose actions were seen as patriotic gestures as they opposed to communist ideology.

-

[17]

Since July 2012, the Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of the Romanian Exile began an archeological investigation campaign at the cemetery at Aiud in order to investigate the remains of former political prisoners.

Bibliography

- Ammerman, N. T. (2007). “Introduction: Observing Modern Religious Lives.” In Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives, edited by N. T. Ammerman. Oxford; Toronto: Oxford University Press: 3-18.

- Ammerman, N. T. (2013). Sacred Stories, Spiritual Tribes: Finding Religion in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Assmann, A. (2006). “Memory, Individual and Collective.” In The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis, edited by R. E. Goodin and C. Tilly. Accessed February 4, 2015. http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199270439.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199270439-e-011

- Assmann, A., and L. Shortt (2012). “Memory and Political Change: Introduction.” In Memory and Political Change, edited by A. Assmann and L. Shortt. New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 1-16.

- Brown, P. (1981). The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Clark, R. (2015). Holy Legionary Youth: Fascist Activism in Interwar Romania. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Conovici, I. (2013). “Re-weaving Memory: Representations of the Interwar and Communism in the Romanian Orthodox Chruch After 1989,” Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 12 (35): 109-131.

- Cristea, G., and S. Radu-Bucurenci (2008). “Raising the Cross. Exorcising Romania’s Communist Past in Museums, Memorials and Monuments.” In Past for the Eyes. East European Representations of Communism in Cinema and Museums after 1989, edited by O. Sarkisova and P. Apor. Budapest: Central European University Press, p. 1-46. Accessed February 18, 2014. http://books.openedition.org/ceup/683

- Fischer-Galati, S. (1971). “Fascism in Romania.” In Native Fascism in the Successor States, 1918-1945, edited by P. F. Sugar. Santa-Barbara, California: Clio, p. 112-122.

- Fischer-Galati, S. (2007). “Codreanu, Romanian National Traditions and Charisma.” In Charisma and Fascism in Interwar Europe, edited by A. Costa Pinto, R. Eatwell and S. U. Larsen. New York: Routledge, p. 107-112.

- Furet, F. and E. Nolte (2000 [1998]). Fascisme et communisme. Paris: Hachette.

- Grigore, M. (2015). Les pèlerines, la religion vécue et la Roumanie postcommuniste. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Sociology, Université de Montréal.

- Halbwachs, M. (1997[1950]). La mémoire collective. Paris: Albin Michel.

- Hossu-Longin, L. (2012). Memorialul durerii. O istorie care nu se invata la scoala. Bucharest: Humanitas.

- Iordachi, C. (2003). “In Search of a Usable Past: The Question of National Identity in Romanian Studies, 1990-2000,” East European Politics and Societies 17(3): 415-453.

- Iordachi, C. (2010). “God’s Chosen Warriors: Romantic Palingenesis Militarism and Fascism in Modern Romania.” In Comparative Fascist Studies. New Perspectives, edited by C. Iordachi. New York: Routledge: 316-357.

- Iordachi, C. (2013). “Fascism in Southeastern Europe: A Comparison between Romania’s Legion of the Archangel Michael and Croatia’s Ustasa.” In Entangled Histories of the Balkans, edited by R. Daskalov and T. Marinov. Leiden: Brill: 355-468.

- Lavric, S. (2014). “Nevoia de martiri.” In Sfintii inchisorilor. Din rezistenta Romaniei crestine impotriva ateismului comunist, edited by R. Codrescu. Bucharest: Editura Lumea Credintei: 58-61.

- Livezeanu, I. (1995). Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building, and Ethnic Struggle, 1918-1930. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Marin, M. (2013). “Between Memory and Nostalgia: The Image of Communism in Romanian Popular Culture. A Case Study of Libertatea Newspaper,” PALIMPSEST czasopismo socjologiczne, 5: 4-16.

- Mark, J. (2010). The Unfinished Revolution. Making Sense of the Communist Past in Central-Eastern Europe. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

- McGuire, M. (2008). Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Every Day Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nolte, E. (1966). Three Faces of Fascism: Action Française, Italian Fascism, National Socialism. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Nora, P. (1984). “Entre mémoire et histoire: la problématique des Lieux.” In Les lieux de mémoire: La République, edited by P. Nora. Paris: Éditions Gallimard: xvii-xlii.

- Ornea, Z. (1995). Anii treizeci. Extrema dreapta romaneasca. Bucharest: Editura Fundatiei Culturale Romane.

- Orsi, R. A. (1997). “Everyday Miracles: The Study of Lived Religion.” In Lived Religion in America. Toward a History of Practice, edited by D. D. Hall: Princeton University Press.

- Orsi, R. A. (2005). Between Heaven and Earth. The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars Who Study Them. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Radu, D. (1986). Indrumari misionare. Bucharest: Editura Institutului biblic si de misiune al Bisericii Ortodoxe Romane.

- Shafir, M. (1985). Romania: Politics, Economics and Society. Political Stagnation and Simulated Change. London: Pinter.

- Stahl, I. (2014). “The Romanian Saints: Between Popular Devotion and Politics.” In Politics, Feasts, Festivals. Yearbook of the Sief Working Group on the Ritual year, edited by G. Barna and I. Povedak. Szeged: Innovariant Nyomdaipari Kft: 86-110.

- Stan, L. (2006). “The Vanishing Truth? Politics and Memeory in Post-Communist Europe,” East European Quarterly XL (4): 383-408.

- Stan, L. (2013). Transitional Justice in Post-Communist Romania. The Politics of Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tismaneanu, V. (2013 [2012]). Diavolul in istorie. Comunism, fascism si cateva lectii ale secolului XX. Bucharest: Humanitas.

- Teodorova, M. (2009). Bones of Contention: The Living Archive of Vasil Levski and the Making of Bulgaria’s National Hero. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Tudor, A., M. Conovici, and I. Conovici (2014) (eds.). Am inteles rostul meu... Parintele Arsenie Papacioc in dosarele Securitatii. Bucharest: Humanitas.

- Vasile, D. (2012). “Minunea de la Iasi.” In Marturisitorii din inchisorile comuniste. Minuni. Marturii. Repere, edited by C. Voicila. Bucharest: Editura Areopag: 79-81.

- Vasile, D. (2014). “Parintele Justin a fost omul care ne-a invatat sa avem curajul unei atitudini.” In Avva Justin Parvu. Marturii. Amintiri. Minuni, edited by V. Herman and D. Vasile. Bucharest: Editura Areopag: 180-185.

- Voicila, C. (2012) (ed.). Marturisitorii din inchisorile comuniste. Minuni. Marturii. Repere. Bucharest: Editura Areopag.

- Volovici, L. (1991). Nationalism Ideology and Antisemitism. The Case of Romanian Intellectuals in the 1930s. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Weber, E. (1966). “Romania.” In The European Right. A Historical Profile, edited by H. Rogger and E. Weber. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press: 501-574.

List of figures

Photo 1

The icon the “Mother of God, the guardian of persecuted people”. I received a similar icon at the Aiud monastery on September 29th, 2012. Carmen showed me the same icon during the interview.

Photo 2

Photo 3

The Aiud monastery (schit). The entrance in the ossuary.

Photo 4

The ossuary of Aiud monastery.

Photo 5

The human remains of the former political prisoners exhibited at the Aiud monastery.

Photo 6

The little reliquary, which contains the “relics” that sprang forth fragrant oil since 2009.