Abstracts

Abstract

The study surveys the existing literature on strategies in simultaneous interpreting (understood here as transformations indicative of interpreting procedures that manifest in the product of interpreting). On the basis of the survey, a summary of eight strategies which are present in various research strands is compiled. I use a parallel bidirectional corpus of Ru-En simultaneous interpreting to extract a random sample of 360 fragments and investigate the presence of the eight strategies in the sample. The type of strategy is then correlated with three variables: direction of interpreting, position of the source fragment in the original text, and phraseological richness of the source fragment. The findings indicate that all the strategies, including an additional transformation category (incorrect interpretations), are present in the sample, although some of them are considerably less common than earlier literature purports. All three variables have significant association with the type of strategy, although in cases of directionality this holds only for saucissonnage and omission. A close analysis of three coding categories—omission, explicitation, and incorrect interpretations—suggests that interpreters in this corpus orient more towards a performative than informative function of their SI.

Keywords:

- simultaneous interpreting,

- strategies,

- corpus studies,

- Russian-English,

- product-oriented research

Résumé

Cette étude présente un panorama de la littérature sur les stratégies en interprétation simultanée (soit les transformations indicatives de procédés d’interprétation se manifestant dans le produit interprété). Sur la base de ce sommaire, une liste de huit stratégies est proposée, stratégies présentes dans diverses avenues de recherche. Un corpus bidirectionnel russe-anglais a servi à en extraire un échantillon aléatoire de 360 fragments. La présence des huit stratégies dans cet échantillon a ensuite été examinée. Le type de stratégie est ensuite corrélé avec trois variables : la direction de l’interprétation, la position du fragment dans le texte original et la complexité phraséologique du fragment. Les résultats suggèrent que toutes les stratégies ainsi qu’une catégorie supplémentaire, celle des interprétations incorrectes, sont présentes dans l’échantillon, mais que certaines sont considérablement moins fréquentes que la littérature ne le laisse supposer. Les trois variables ont une association significative avec le type de stratégie, mais dans le cas de la direction uniquement pour le saucissonnage et l’omission. Une analyse des trois catégories de codage – omission, explicitation et interprétations incorrectes – suggère que les interprètes de ce corpus potent le plus souvent pour une fonction performative plutôt qu’informative de leur interprétation simultanée.

Mots-clés :

- interprétation simultanée,

- stratégies,

- études de corpus,

- russe-anglais,

- recherche orientée vers le produit

Resumen

El estudio examina la literatura existente sobre estrategias en interpretación simultánea (entendidas aquí como transformaciones indicativas de los procedimientos de interpretación que se manifiestan en el producto de la interpretación). Sobre la base de la encuesta, se compila un resumen de ocho estrategias que están presentes en varias líneas de investigación. Utilizo un corpus bidireccional paralelo de interpretación simultánea de ruso-inglés para extraer una muestra aleatoria de 360 fragmentos e investigar la presencia de las ocho estrategias en la muestra. El tipo de estrategia se correlaciona con tres variables: la dirección de interpretación, la posición del fragmento fuente en el texto original y la complejidad fraseológica del fragmento fuente. Los hallazgos indican que todas las ocho estrategias más una categoría adicional, “interpretaciones incorrectas”, están presentes en la muestra, aunque algunas de ellas son considerablemente menos comunes de lo que afirma la literatura anterior. Las tres variables tienen una asociación significativa con el tipo de estrategia, aunque en el caso de la direccionalidad, esto es válido solo para la segmentación y la omisión. Un análisis detallado de las tres categorías de codificación (omisión, explicitación e interpretaciones incorrectas) sugiere que los intérpretes en este corpus se orientan más hacia la función performativa que informativa de su IS.

Palabras clave:

- interpretación simultánea,

- estrategias,

- estudios de corpus,

- ruso-inglés,

- investigación orientada al producto

Article body

1. Introduction: translation strategies as a theme in translation studies

The following example from a speech delivered in a meeting of the UN Human Rights Council, and its simultaneous interpretation, lay clear a surface mismatch in the two texts even to someone who does not read Russian:

What we see here is compression, which is often showcased as a key strategy of Russian-English interpreting (resulting in a considerably shorter English text). This and similar mismatches explain the fascination with the translational shifts between source and target texts (ST and TT)[1] and with the many attempts to inventory them. Setton (1999: 50) states that “it has become commonplace in the training community to define SI skills […] in terms of a number of acquired ‘strategies’.” Indeed, the discipline of translation studies has been engaging with the notion of translation strategies for a long time. The staple of every translation course, Vinay and Darbelnet (1958/2004) “condense” different methods or procedures of translation into seven categories: borrowing, calque, literal translation, transposition, modulation, equivalence, and adaptation. Vinay and Darbelnet’s list has become a springboard for the developers of further taxonomies of translation strategies, some of which I will discuss below. It is the aim of this article to compile a summary of the existing taxonomies of, specifically, strategies for simultaneous interpreting (SI) that have so far been proposed, and to test whether these strategies in fact appear in natural SI data or whether they are a product of top-down theorizing and introspection that do not necessarily appear in context.

Any attempt to formulate strategies for translators rests on the assumption that there is a certain desirable result to be attained; in other words, they revolve around the notion of equivalence (for summaries of extensive scholarly work on equivalence in translation and interpreting, see Munday 2010; Pöchhacker 2004). As defined by Toury (1995/2012: 112), equivalence is “a functional-relational concept, namely, that set of relationships which are found to distinguish appropriate from inappropriate modes of translation for the culture in question.” In the spirit of this functional-relational duality, translation strategies may refer either to a set of recommendations to achieve equivalence, or, in a descriptive translation approach, to the identified relationship of difference (or “content departure”; Vančura 2017: 5) between the unit of translation in the source and target text.

Turning from translation studies to its younger sister, interpreting studies, the intellectual yield of the equivalence debate has only been adopted relatively recently. Interpreting studies scholars instead used the notions of accuracy, fidelity, and completeness to judge the result of interpreting, as if the existence of a single ideal, a one-to-one correspondence between the source and the target, were a given fact (Pöchhacker 2004: 141). Accordingly, the discussion of strategies uses those notions as reference points (Abuín González 2007; Riccardi 1998; Sunnari 1995). This is even more true for the study of simultaneous interpreting, which, as recently as a decade ago, remained “an arcane field of study” among other translation modes (Setton 2005: 70). In SI, interpretation strategies have often been viewed from an applied pedagogical perspective as recommendations for interpreters in training (see Gran 1998; Riccardi 2005; Visson 1991). Indeed, this illustrates two distinct stances towards strategies in the translation studies literature: one views them as systematic shifts that occur when rendering content from one language to another (Vinay and Darbelnet-style); the other, as more or less prescriptive guidelines to be followed for equivalence. Although one may hope that the latter are grounded in the empirical research on the former, and overlap, this is not always the case. On the one hand, the reason is partly that some shifts are undesirable and occur as a result of some kind of translation breakdown. On the other hand, it is partly so because instructors often draw on their intuition and experience rather than reproducible corpus research to come up with the directions. It is the second shortcoming that the present study aims to address.

It is important to remark that the notion of equivalence itself is increasingly problematised in contemporary research, namely as a consequence of growing tensions between different models of interpreting. The choice of model often determines the understanding of strategy, or strategic transformation, that is applied in a particular study. This complexity is further increased by the development of language-specific interpreting models. Section 2 below is devoted to the discussion of translation strategy as a term in this study.

In this paper, I will work with two research questions. I intend (1) to find out if all the main interpreting strategies as posited in the literature occur in a bidirectional corpus of Ru-En simultaneous interpreting, and (2) to find out if the type of strategy is associated with any of the three variables: directionality, position in the speech event, phraseological richness.

Since strategies ultimately involve shifts between two different language systems, the specific systems in question are important for the study. For that reason, I will draw on the SI strategies proposed specifically for Ru-En interpreting along with the better-known models by Western scholars.

2. Strategies and transformations in translation and interpreting

The concept of strategy is surrounded by great terminological variability. Vitrenko (2008: 3-4) surveys the applications of the term across the literature, noting that it can be taken to mean many different things, sometimes by the same author. Among them are a principled approach to solving specific problems within the framework of a global translation aim, translation tactics, the correct ways of translating, a translator’s action plan, the process of developing communicative strategies, etc. For instance, Minyar-Beloruchev (1980: 155) defines a translation/interpreting strategy as a system of interrelated translation/interpreting practices, accounting for translation modes and translation resources. Hurtado (1999: 246, cited and translated by Arumí Ribas 2012: 814), defines translation strategies as “the individual procedures, both conscious and unconscious, verbal and non-verbal, used by the translator to solve the problems encountered in the course of the translation process, depending on the specific requirements involved.”

Englund Dimitrova (2005: 26) draws a distinction between the definitions of strategy that are based on purely textual data and those based on other kinds of data, like think-aloud protocols. An example of the former is the taxonomy of strategies by Chesterman (1997: 94-112), which are seen as shifts, or translational transformations, in the TT, as compared to its ST. This presents a further conflation between the thought process of the translator or interpreter, and the resulting change in the TT.

The aim of the present paper is to provide the widest possible interpretation of the term strategy. As a result, I take strategy to refer both to the transformations in the TT, as compared to its ST, and, on the cognitive level, to the reasoning triggering these transformations. In the didactic literature (see Section 3 below), these would often be formulated in the shape of “if X, do Y.” For example, the label compression strategy can refer to the fact that the communicative unit in the source text (for instance, the request in Example 1 above) contains noticeably more semantic items than the target, but also, in a more abstract sense, to the relationship that exists between these two units.

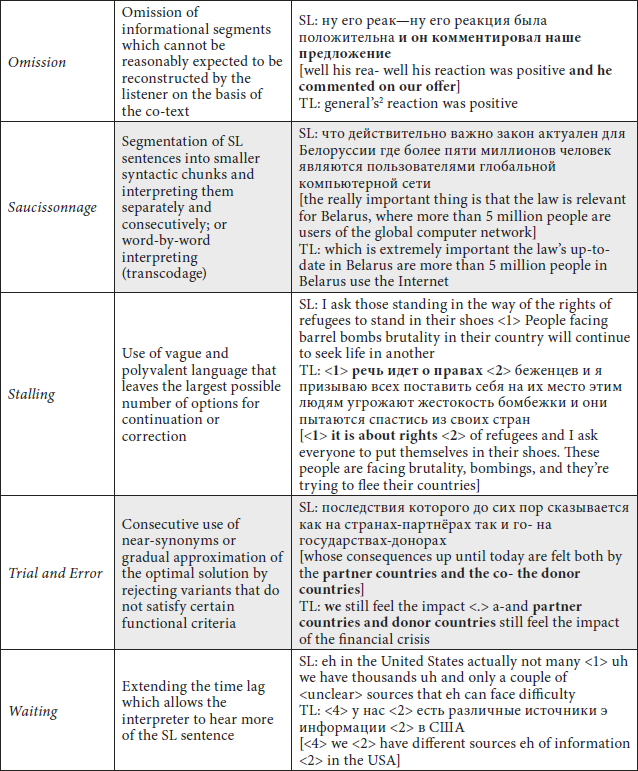

This conflation of meaning, although problematic for process-oriented research, serves the purposes of the present corpus-based study. Dam (2001: 29) makes explicit this approximation from the product to the process, labelling her object of research “the assumed product-manifestation of […] interpreting procedures.” Therefore, in the taxonomy developed in Section 3, I will include the product-manifestations of interpreting strategies in the most general sense (see Table 1). This approach undoubtedly has drawbacks. However, I believe that it reflects the state of terminological variability in the existing literature, so rather than establishing the best practice of an unambiguous definition, I aim to be most inclusive of existing understandings of strategy.

The variability is exacerbated in Russian where the term перевод refers to translation as well as interpreting. This means that in the theoretical literature it is at times not possible to know if the author considers their taxonomy specific to one mode, or if they intend for it to apply to both. The findings of translation research form an important basis for the investigation of interpreting, although they cannot be directly equated across the two modes since the cognitive processes involved are quite distinct. However, the corpus linguistic approach, which works with the product of SI in the form of a transcription, can, in some aspects, usefully borrow from the text-based findings of translation studies.

The existing taxonomies of interpreting strategies are extremely diverse: they differ on the level of granularity, in regard to the guiding principle to distinguish strategies (level of language, form/function, type of sense transformation), and even depend on whether purely linguistic or other interpreting behaviours are included. The authors who look specifically at Russian-English interpreting (usually from a didactic perspective) have tended to focus on the strategies that enable the interpreter to cope with the grammatical asymmetries of language systems, for example, the fact that there are fewer tenses in Russian compared to English. Gorokhova (2003), looking at three hours of professional SI from English into Russian of conference speeches about education policies, created an exceedingly detailed taxonomy of lexicosemantic, lexicosyntactic, and syntactic transformations. To illustrate the level of granularity, some of the strategies she proposes include prepositional phrase > dependent clause, abbreviation of an institution, but also more abstract processes such as concretisation or generalisation. An even more granular approach is taken by Poluyan (2011) who details the processes of lexical and syntactic compression involving, for instance, repeating auxiliaries without the main verb.

The close attention that contrastive linguists pay to the level of syntax is not surprising. It is here that the on-line nature of SI can be a source of greatest difficulty for the interpreter. We only need to remember the oft-cited description of simultaneous interpreting by Glémet (1958: 120-121):

As you start a sentence you are taking a leap in the dark, you are mortgaging your grammatical future: the original sentence may suddenly be turned in such a way that your translation of its end cannot easily be reconciled with your translation of its start. Great nimbleness is called for to guide the mind through this syntactical maze.

Additional problems are caused by the fact that Russian and English grammatical systems demonstrate a large degree of asymmetry. Visson (1991: 118) describes the syntax of a Russian sentence as “a minefield, which the interpreter must hope to cross unscathed.” Some authors pick up on this obstacle as the very reason to learn and apply SI strategies: for example, Shiryaev (1979) suggests sentence segmentation or, on the contrary, the merging of clauses into a single sentence to deal with syntactic mismatch.

Syntactic transformations are complemented by a wide variety of strategies on other language levels: semantic, lexical, discursive. Visson (1991) lists specific operations (such as omit modifiers or substitute military metaphors) along with general guidance (tone down the register in Ru > En, as English is less stylistically high-flown) and language-independent coping strategies (approximate numerals and factual information). Visson’s taxonomy is one of the most developed, numbering 19 strategies and transformations (nine “tricks of the trade” along with other common transformations) closely followed by Gorokhova (2003) with 18 transformation types, and Poluyan (2011) with 14 strategies of compression.

3. Taxonomy of interpreting strategies for analysis

In order to address the present study’s research question, I set out to distil a synthetic list of interpretation strategies at, so to say, the basic level of categorisation. On the one hand, the strategies need to be specific enough to be descriptively adequate and detectable in corpus data. For example, Hurtado’s (2001) linguistic strategy would be very difficult to operationalise in such a way as to conclusively demonstrate its presence (or rather absence) in any stretch of translation. On the other hand, the taxonomy needs to be general enough to be potentially expandable to different languages, and to constitute strategies for coping with a class of situations rather than listing specific interlingual mismatches.

To derive such a taxonomy from the broad available literature, I was guided by the overlap in the sources that take different methodological and thematic approaches to the study of SI strategies. If a strategy in some form has been reported in all, or most of the strands of research, then the strategy was included on the unified list. The research strands reviewed are as follows:

Didactic literature (Ilg 1978; Kader and Seubert 2015; Poluyan 2011; Shiryaev 1979; Visson 1991; Viaggio 1992);

Experimental literature (Arumí Ribas 2012; Dam 2001; De Feo 1993 in Gran 1998; Riccardi 1996; Seeber 2001);

Sources using corpora (understood as samples of naturally occurring SI) for bottom-up taxonomy construction (Chernov 2004; Gorokhova 2003; Kalina 1994; Kalina 1998);

Sources putting forward top-down taxonomies based on intuition, existing theory or earlier literature with examples (Pearl 1995; Riccardi 1998; Riccardi 2005; Sunnari 1995);

Introspective studies relying on think-aloud protocols and interviews (Bartlomiejczik 2006; Granhagen Jungner, Tiselius, et al. 2018; Ilukhin 2001; Ivanova 2000; Kalina 1998; Kohn and Kalina 1996);

Process-oriented psycholinguistic research (Chernov 2004; Gile 1995; Kirchhoff 1976; Lörscher 1991; Setton 1999; Zimnyaya and Chernov 1973).

In this manner, the unified list is the result of a triangulation process. I will go through the master list below, describing each group of similar strategies to give the reader an idea of the degree of consensus on each.

The first of these, compression, is present in different forms in all but corpus-based research strands. Compression refers to finding a briefer way of expression in the target language (TL) as compared to the source language (SL), and the result of such a change. It subsumes lexical compression (deliberate choice of shorter words, compact idioms, verbs of manner instead of descriptive phrases, compact referent, etc.) as well as syntactic compression (elliptical constructions, verbless sentences, etc.).

An important distinction needs to be made between compression and the second omnipresent strategy, omission. Compression describes a situation when the hearer can be reasonably expected to reconstruct the elided parts from the surrounding co-text. Omission, on the contrary, constitutes a content departure in which the original content is not re-constructible by the hearer on the basis of co-text. The omission, presumably, happens as a consequence of a high cognitive load (although this cannot be ascertained in product-oriented research design) and can be described as “ignoring” text segments containing information (Arumí Ribas 2012). It appears in various forms—as omission, deletion, or reduction of information—in all research strands with the exception of corpus research.

The third common strategy entails an expansion of the target text in comparison to the source text. It can include explicitation, when the interpreter verbalises the elements that were implicit in the source (Tang 2018), or addition and completion, when the interpreter verbalises the information that the addressee might be able to infer if it were not verbalized (Becher 2011) or even the information the addressee would not have been able to infer without the background knowledge that the interpreter has. Various flavours of explicitation (elaboration, expansion, adding wrong information—although of course this latter one is not strategic in the traditional sense) have been mentioned in all the taxonomy groups.

The first three strategies, which unify most of the reviewed literature, describe such changes in the volume and content of the text that are easy to observe in a parallel corpus. They, however, do not speculate about the underlying reasons for the change. The remaining strategies, although they too appear in product-oriented as well as process-oriented sources, are conceptually different. They simultaneously describe the product of interpreting and hypothesise the reasons for the transformation (usually to do with processing constraints).

The strategy of trial and error, for instance, mentioned in the didactic literature (as gradually approximating synonyms), in introspective studies (as approximation), in psycholinguistic research (as preliminary solutions to problems), and in corpus studies (as evidence of monitoring), refers to the “gradual approximation to the optimal solution by rejecting variants that do not satisfy certain functional criteria” (Shveitser 1988: 84). Even the label itself reflects the presumption that the surface evidence—namely, a subtype of self-correction, appearing as such in the taxonomies by Kirchhoff (1976) and Kalina (1994)—is present for a known reason. Visson (1991), in fact, recommends it as a strategy to be consciously applied in situations when the trainee interpreter struggles with immediately finding a precise equivalent to avoid having to resort to omission and at the same time to maintain content fidelity.

In the same vein, the strategy of waiting is documented in all the research strands with the exception of corpus and experimental studies—among others, as extending and narrowing the time lag or increasing decalage. When an interpreter is unable to commit to a definite solution, they can increase the time lag in order to hear more of the source text before speaking. Alternatively, they can resort to a similar strategy of stalling (or open gambit, padding, strategy of least commitment, neutral fillers, and open sentences that can be corrected). When stalling, interpreters maintain the minimal time lag for performative purposes while producing an “open gambit” structure, for example “In the following, I am going to talk about various issues, such as…”

Anticipation is an extremely interesting phenomenon of SI that features prominently in cognitive models. As an interpreting strategy, anticipation appears in all research groupings. Setton (2002: 188) defines it as a situation when predicates or other downstream elements appear to be guessed at by the interpreter. In their ground-breaking psycholinguistic research, Zimnaya and Chernov (1973) and Chernov (1978) concluded that strategic anticipation is a result of the message redundancy characteristic of all natural languages. Based on the early computational linguistic findings indicating that redundancy in Russian, French, and English makes up for 71-84% of all speech (Piotrowsky 1968: 58), the authors argued that it is redundancy that enables the interpreter to finish a propositional statement before it has been spoken by the speaker in full. These studies have been followed by a corpus-based account of anticipation (Lederer 1981) which indicated that it is extremely common, occurring up to once every 85 seconds (Van Besien 1999). Seeber (2001), however, warns that when examining parallel transcripts, we may suspect anticipation when there is none. Instead, what we see is approximation or an open gambit strategy.

Finally, the group of strategies that have to do with segmentation appear in the literature when dealing with a syntactically difficult source. One of these is saucissonnage, pre-emptive segmentation of input, described by Seleskovitch and Lederer (1989: 148 cited by Pöchhacker 2015: 368) as “working with sub-units of sense.” Another one is transcoding—word-for-word, verbal, direct or literal transposition of such segments—that concerns surface-level operations. This group of strategies came up in all research strands. Segmentation and transcoding allow the interpreter to unload their short-term memory, although arguably the need to formulate several complete grammatical sentences instead of just one may prove to be more difficult in terms of processing capacity (Gile 1995: 205).

The summary of the strategies and examples from the corpus can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

Eight generalized simultaneous interpreting strategies with examples[2]

4. The SIREN corpus and its application for the study of strategies

A great deal of the literature on strategies in SI relies on the authors’ introspection or analysis of a small sample. For example, among those data-based studies of SI that report the size of their sample, Zimnaya and Chernov (1973) analyse one 20-min speech and its interpretations by six different interpreters; Kalina (1998) transcribes one 70-min source speech and five student interpretations of this speech; Gorokhova (2003) works with 15-min speeches, for a total of three hours, and the corresponding length of the target speech; Riccardi (1996) uses 15 minutes of source speeches interpreted by 18 subjects. That is not to say that intuitions of an experienced teacher and practitioner should be discounted as incorrect or insufficient, or that a taxonomy gleaned from a close analysis of one speech will necessarily be flawed. However, this bottom-up approach must then be complemented with a top-down analysis of a large amount of data to test the validity of the taxonomy categories and to judge their frequency. Kalina (1998: 173, my translation), outlining further steps in strategy research, calls for “a small number of complex research questions asked of large amounts of authentic data.”[3] Only a study of a large and representative corpus can estimate how often each strategy is in fact used and how important it may turn out to be for a trainee interpreter. Finally, a sample of SI randomly selected from a large representative corpus can yield findings on the source stimuli likely to produce certain strategies.

To enable this next step, a corpus is necessary. A corpus-based study of interpreting suffers from a scarcity of corpus data given the practical challenges: dual track recording, copyright, access to events, time-consuming transcription, and lack of established transcription and annotation conventions (Bendazzoli and Sandrelli 2009; Sandrelli, Bendazzoli, et al. 2010; Straniero and Falbo 2012). Among the existing SI corpora, the one that stands out in terms of its size, diversity, enrichment with annotation, and, very importantly, free availability to researchers, is EPIC (Russo, Bendazzoli, et al. 2012). EPIC is a parallel multidirectional corpus of approximately 280,000 words that consists of speech events in English, Italian, and Spanish, and their interpretations in each of these languages. Other corpora are either not freely available or are much smaller in size, and comprise the data from official EU languages, for instance: CoSi, by Meyer (2010),[4] with a SI component of about 18,000 words; and FOOTIE, by Sandrelli (2012), with 22,000 words (for an overview, see Bernardini and Russo 2017).

To satisfy the need for a large database of SI in Russian and English, I have created the SIREN corpus, modelled in many aspects on EPIC. SIREN is a parallel bidirectional corpus of political speeches, briefings and interviews. At the moment it comprises approximately 230,000 words, 33 hours of dual track recordings, in four subcorpora: speeches spontaneously delivered in Russian, their simultaneous interpretations into English, speeches spontaneously delivered in English, and their simultaneous interpretations into Russian (Table 2). Following the example of EPIC, the corpus relies on simple orthographic transcription with additional features such as truncated words, pauses, and disfluencies.[5]

Table 2

SIREN size and composition

SIREN offers a comparatively large database of professional SI, both in free and “with text” modes, interpreters working into their A and B languages, and of speech events that range from prepared monologual speeches to spontaneous question-answer sessions. Different genres and settings mean that I reasonably expect all the main interpreting strategies to appear in the material: the key SI challenges, such as time pressure, information density, complex syntax, idiomatic language, and rapid topic change, are all likely to be present.

To study the occurrence of the eight generalized interpreting strategies (Table 1), I adopted the following procedure. A sample of 360 five-second transcription fragments, 180 for the SL Russian and 180 for the SL English, was extracted from the corpus. To ensure random sampling, the file number and the line number for each extracted excerpt were obtained from a random number generator. These SL excerpts were then matched with their counterparts in the TL and, if necessary for comprehension, expanded. I then manually annotated each SL-TL pair for the presence of the eight strategies. If no significant change to content or detectable surface mismatch occurred, the excerpt was coded as not exhibiting any transformations/strategies. Drastic content departures were coded “incorrect.” One excerpt could exhibit evidence of more than one strategy—in this case it was entered multiple times with separate codes; as a result, the final dataset has 397 entries.

To supplement the information on the direction of interpreting, each excerpt pair was also coded to include information on where in the speech event it occurs and how strongly the source excerpt relies on pre-patterned language. The relative position was calculated using the line number and the total number of lines per transcription of the event, and also converted to nominal variables to reflect whether it fell within the first 10% of the event (“beginning”), the last 10% (“end”), or in the main body of the transcription (“main”). This division is based on the observation that the beginning and end of the speech events in the corpus tend to be extremely formulaic and predictable, involving, for example, set formula for opening a UN General Assembly (“I declare open the 70th regular session of the General assembly…”). This can have implications for the cognitive load on the interpreter when interpreting these excerpts, and consequently, on the strategy use.

What happens to prefabricated chunks in translation has been the subject of study for many years (Kenny 2001; Malmkjaer 1993; Øverås 1998), and this interest has recently extended to simultaneous interpreting (Ferraresi and Miličević 2017; Dayter 2020). The reliance on chunks in this case is taken as a proxy to complexity of input, which has been shown to be a problem trigger for simultaneous interpreters (Gile 1995; Plevoets and Defrancq 2016, 2018). The degree of reliance on pre-patterned language, which I call phraseological richness,[6] was calculated as a relative frequency of phrases from PHRASE list (Martinez and Schmitt 2012) in each English SL excerpt, and the top 505 phrases from the list prepared by the Russian National Corpus[7] creators (Plungyan 2005) in each Russian SL excerpt. PHRASE is a list of the 505 most frequent non-transparent multiword expressions in English, developed with a special regard to receptive use. The list of Russian pre-patterned expressions is a frequency-based list compiled with reference to phraseological dictionaries. Both lists were expanded to include the wordforms for all relevant lemmas. The phrase frequency was also converted into nominal variables to reflect general levels of reliance on the phrases: “poor” when the excerpt has 0-1 phrases, “mid” for 2-3 phrases, and “rich” for 4+ phrases.

In the next section, I present the descriptive statistics and the results of Fisher’s exact tests and logistic regression to establish correlations between the presence of interpreting strategies and the features of the SL described above. All analysis was carried out using R.[8]

5. Interpreting strategies in the SIREN random sample

5.1 Quantitative analysis

I found all eight strategies to be present in the data. However, some strategies occur much more commonly than others (see Table 3). In one third of the annotated excerpts no detectable traces of strategic transformations were found (although, of course, we must be very cautious when interpreting corpus-based observations in the light of underlying cognitive processes; see Marco 2009). The association between the presence of an interpreting strategy and the direction of interpreting (coded as a two-level variable, strategy present/none) was not significant.

Among the detected strategies, the strategies that aim at minimising the volume of TL output are preferred—both omission and compression are very common. They are, however, closely followed by explicitation, so one cannot conclude that interpreters attempt to compress the output at all costs. Anticipation appears vanishingly seldom, in 1% of the SIREN sample. Such scarcity is at odds with the prominence given to anticipation in SI models.[9]

What could have caused such a low incidence? It might be due to the combined effects of the way I operationalised anticipation and of the transcription alignment. To be coded as anticipation, the TL transcription must contain a semantic fragment before it appeared in the SL transcription. In terms of the SIREN material, which is aligned at 5 second intervals, this means that the interpreter must anticipate the speaker by at least 5 seconds. Such a margin is likely too high to detect the majority of anticipations: Chernov, Gurevich, et al. (1974), for example, set the length of their unit of analysis at 2.16 seconds.

An overall rate of strategy occurrence might not be very telling on its own, as a variety of factors has been cited as affecting the choice of appropriate strategy or the need for such emergency strategies, such as waiting or transcoding. To hazard a guess at what these factors might be, and to enable further studies of these factors, it is useful to consider the distribution of strategies in the interpreted speech events (Figure 1 and Table 4).

As expected, the least amount of strategic transformations occurs in the very beginning and the very end of the speech events. There was a significant association (p < .0001, Fisher’s exact) between the position in the text (predictor variable coded in three levels: beginning, main body, end) and the type of strategy. As mentioned above, these sections are highly formulaic and repetitive across speeches, and place little cognitive strain on the interpreter.

The boxplot in Figure 1 places incorrect translations closer to the end of the ST—predictably, when the interpreter is tired and the attentional deficit leads to the deterioration of output. Interestingly, anticipations are also found towards the end of the main part of the speech, which might have to do with the growing familiarity with the topic and speaker style. Stalling and segmentation, on the contrary, cluster in the first half of the speech events.

These results indicate that a relationship between the two variables exists, namely that interpreters are more likely to resort to certain interpreting strategies depending on whether they have only just started their turn or have been interpreting for a while. Since speech events in the corpus are on average 30 minutes long, this means that the transformations indicative of interpreting strategies differ in the first 3 minutes of interpreting vs. the following 24 minutes vs. the last 3 minutes. However, as the position in a speech event can be tied both to a growing attentional deficit over time and to the predictability of the opening/closing formula vs. the spontaneity of the main body of speech, it is impossible to tease apart these two factors in this research design.

In order to investigate the effects of lexical complexity on interpreting strategy, the frequency of pre-patterned lexical chunks in every source language excerpt was calculated. On the basis of the frequency distribution illustrated in Figure 2, I distinguish three degrees of phraseological richness: “poor” when the SL excerpt has 0-1 phrase, “mid” for 2-3 phrases, and “rich” for 4+ phrases. There was a significant association between the degree of phraseological richness and the type of strategy (p < .0001, Fisher’s exact). Figure 3 and Table 5 illustrate the distribution of interpreting strategies across the excerpts with different degrees of phraseological richness.

As one can see in Figure 3, all the phraseologically rich (Nph>6) excerpts in the dataset are outliers, so drawing conclusions from such highly formulaic SL segments is not meaningful. It is interesting that the deviation toward lower phraseological richness (Mdn<1) is found for anticipation, explicitation, and stalling. In line with the hypothesis that phraseological richness is indicative of lexical complexity and therefore of increased cognitive load, such processes as anticipation and explicitation, which require cognitive effort, would indeed be expected in the easier passages. Stalling is a less obvious candidate. After a closer look at the data, the presence of stalling could be explained as an artefact of unusually long excerpts in the sample. Since stalling passages preceded the content interpretation, the excerpts extracted from the corpus had to be extended to include both the content and the open gambits. This resulted in the stalling excerpts being longer (M=31, SD=17) than an average excerpt in the sample (M=23, SD=9), and therefore likely to include more chunks.

Finally, the association between the direction of interpreting and the presence of each of the nine transformations was significant only for saucissonnage (lower in the En>Ru subcorpus, p<.01, Fisher’s exact) and omission (higher in the En>Ru subcorpus, p<.001, Fisher’s exact).

Table 3

Frequency distribution of strategies in the sample

Table 4

Strategies in the interpreted speech events

Table 5

Degree of phraseological richness per strategy used

Figure 1

Distribution of strategies in the interpreted speech events

Figure 2

Pre-patterned chunks in SI excerpts

Figure 3

Interpreting strategies vs. phraseological richness

5.2 Source-target analysis

In the following, I will take a closer look at the two strategic transformations that stand out in quantitative analysis and could help shed light on SI as a purpose-oriented activity: omissions and explicitations. Incorrect interpretations are also investigated as evidence of the breakdown of the interpreting process on the transformation level, although they do not constitute a strategic operation in the traditional sense.

Although there is no statistically significant correlation between interpreting incorrectly and either phraseological richness or position in the file (examined using multinomial logistic regression, both predictors measured as scale variables), the excerpts coded “incorrect” seem to occur in the second half of the speech events (see Figure 1). A test of statistical significance is not hugely helpful in situations when the investigated variable occurs so seldom: there are only seven incorrect translations. Instead, I looked at each individual excerpt containing incorrect renderings.

There does not appear to be a single identifiable cause for these breakdowns. In his study of “flagrant errors or omissions” in SI, Gile (1999: 161) concludes that the intrinsic difficulty of the source-speech segments is not the reason for incorrect interpretations. This is also the case for the incorrect interpretations in the SIREN sample, see the three examples below:

Example 2 involves a flagrant error, Example 3, a considerable omission, and Example 4, an error that is subtle but all the more disruptive because, as a result, the speaker’s attitude is changed from merely polite to personally involved. Examples 2-4 do not have specialty or language-specific difficulties in the source. Moreover, two speech events interpreted by two interpreters account for five of the errors, suggesting idiosyncrasy rather than text-internal explanations. All the cases, with one exception, occurred in the speeches that were interpreted freely (as opposed to “with text”). There was no significant difference in the number of incorrect interpretations in the En>Ru vs. the Ru>En subcorpus.

In contrast to Gile’s (1999) definition above, incorrect interpretations in SIREN included not only errors and omissions, but also additions that could not have been classified as explicitations (that is, they did not involve making explicit a meaning that was implicitly encoded in the SL). In Example 5, the interpreter both omits the specific descriptor of the type of website (“sex forum”) and adds a reference to “downloading wrong files” which is not encoded in the source:

The other strategy that is predicted by its position in the ST is omission (p<.001, multinomial logistic regression model fitted using the R package nnet[10]). The earlier in the ST a segment occurs, the more likely it is that the strategic transformation in its interpretation will be omission. One common type of omission involves omitting stance and politeness expressions, as in Example 6:

The omission of stance expressions in the product of interpreting is especially interesting as Friginal (2009), for instance, ties interlingual variation in stance to differing perceptions of courtesy and respect. Other stance and politeness expressions omitted in the SIREN sample include respectful address terms, modal verbs of volition, adverbs of certainty and likelihood, stance particles (“опять-таки”), and whole clauses (for instance, “as I hope you know”).

However, the bulk of omissions concern factual information that the interpreter either failed to understand or retain, or decided to leave out in order to maintain simultaneity. In Example 7, for instance, the interpreter omits the name of the previous questioner (probably judged irrelevant) and then, after a 2-second pause, a specific reference to the 70-year history of the UN:

Finally, the other strategy that can be viewed as indicative of the interpreter orienting towards their audience is explicitation. Pym (2005) in his model of explicitation proposes that its purpose is to manage the risk of non-communication. The target audience shares fewer background references with the speaker than the SL audience, and therefore the risk of non-communication is higher. Unlike the previous two transformations, explicitation is not a coping strategy or evidence of breakdown. Analysing retrospective interviews with conference interpreters, Gumul (2006) found that the type of explicitation corresponding to the one in the present paper[11] (that is, meaning specification) was mostly agentive and was employed with the purpose of reducing the processing effort for the target audience.

Explicitations in the SIREN sample support Gumul’s (2006) findings. The explicitation could be done via specifying generic information with proper names, toponyms or dates (Example 8), filling out elliptical constructions (see example for explicitation in Table 1), unpacking acronyms (Example 9) or adding explanatory comments on general knowledge matters (Example 10). There was no significant difference in the number of explicitations in the En>Ru vs. the Ru>En subcorpus.

This kind of explicitation reflects audience design on the part of the interpreter. Explicitations are sometimes performed at the expense of simultaneity: see for instance Examples 9 and 10, where the interpreters sacrificed temporal advantage to add the explicitating information. This practice forms a counterpoise to the other common strategy, omission, which is sometimes employed to minimise the lag. On the whole, however (see Table 2), omission, compression, and segmentation are markedly more frequent than explicitation, waiting, and trial and error. Hypothetically, this distribution is a sign that the interpreter orients towards a performative goal rather than a content-oriented goal. In other words, it is more important to maintain a fluent and coherent delivery than to ensure the transfer of correct meaning. In the contexts of speech events in the SIREN corpus, which occur in high-stakes situations and where all involved will eventually receive carefully prepared written translations and transcripts, it is not surprising that SI may foreground form over substance. Although, of course, the interpreters deliver a high-quality product that is mostly true to source, some frequency evidence discussed above suggests that greater attention is paid to performance than what quality assessment criteria traditionally dictate to students.

6. Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, I set out to review the literature on translation and interpreting strategies, to create a master list of strategies appearing in different research strands, and to investigate their presence in a corpus of natural SI. To date, few systematic corpus-based quantifications have contributed to the strategy debate, and none of them on the bidirectional Russian-English material.

The conclusions are drawn on the basis of manual annotation of 360 excerpts randomly extracted from the SIREN corpus. Having reviewed the results, I established that all eight strategies from the master list are present. An extra category of “incorrect interpretations” had to be added for those cases of non-strategic transformations where flagrant errors, omissions or additions were observed in the TT.

I found a significant association between the type of strategy and their position in the source speech, as well as their phraseological richness. When the position in the source speech was coded as a three-level variable which makes a distinction between the beginning (the first 10%), the end (the last 10%), and the main body of the source speech, few strategic transformations were found in the beginning. Only two strategies, omission and saucissonnage (segmentation), had a significant tendency to occur closer to the beginning of the speech. Phraseological richness, measured as the number of pre-patterned phrases per SL excerpt, was overall quite low in the sample. An especially low median for phraseological richness was observed for anticipation and explicitation, two strategies that place further cognitive strain on the interpreter.

A combination of quantitative and qualitative findings leads me to make an observation concerning the frequencies of the relative strategies. The most frequent strategies are those that are aimed at delivering fluent and uninterrupted output, sometimes at the expense of complete and faithful content transfer. The strategies that are aimed at ensuring content transfer at the expense of smooth delivery are on the whole less common. Trial and error, waiting, and explicitation, that is, content-oriented strategies, account for 36% of the strategy inventory, while compression, omission, saucissonnage, and stalling account for 61%. I hypothesise that this indicates a preference for the performative function of SI over the informative one. Importantly, such a preference might be tied to the context of SIREN speeches. Kurz (1993: 16) showed that when compared to other audiences (medical doctors, engineers, and even interpreters), the delegates of the Council of Europe—a setting similar to that where SIREN was compiled—rated fluency of delivery, logical cohesion, native accent, and other performative aspects of SI as relatively more important compared to sense consistency.

However, the sample size is small and the observed frequencies low. Inferential statistical findings on some of the strategies are bound to be inconclusive. For example, I detected only three occurrences of anticipation in the sample of 360 excerpts—quite a surprising finding in itself given the weight it is ascribed in cognitive models of SI. All in all, although the corpus study confirmed that all the strategies do indeed appear in natural SI, it has also shown that they are used less often than the didactic or intuition-based literature leads us to believe. Whether this difference is representative of SI in general, or is down to other variables (for example, the current SI corpus of political discourse, both free and “with text,” might differ from the “with text” SI at scientific and medical conferences) can only be established by further corpus-based studies of respective corpora using random sampling and multiple coders.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Hereafter the speeches in the corpus of interpreting are referred to as oral texts or texts, to enable further use of traditional terminology such as target/source text.

-

[2]

Verbatim.

-

[3]

“Es wäre also zu fordern, zunächst größere Mengen authentischen Materials auf weniger komplexe Fragestellungen hin zu untersuchen” (Kalina 1998: 173).

-

[4]

Meyer, Bernd (2010): Consecutive and Simultaneous Interpreting (CoSi). Version 1.1. Hamburger Zentrum für Sprachkorpora. Consulted on 12 November 2020, <http://hdl.handle.net/11022/0000-0000-5225-A>.

-

[5]

See Dayter (2018) for the detailed description of the transcription and the corpus building process; see Dayter (2020) for information on individual texts comprising the corpus and on POS annotation.

-

[6]

Both the terms phraseological richness and phraseological complexity exist in linguistic research (see namely Paquot and Granger 2012; Brezina 2018), with phraseological richness somewhat preferred in the Russian context.

-

[7]

Национальный корпус русского языка [National corpus of the Russian language] (Last update: 20 December 2020): Institute of Russian language, Russian Academy of Sciences. Consulted on 19 November 2020, <http://ruscorpora.ru/obgrams.html>.

-

[8]

R Core Team (2016): R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Version 3.1. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

-

[9]

See Kohn and Kalina (1996: 123), who state that anticipation is a fundamental feature of strategic discourse processing, or Van Besien (1999), who cite it as appearing every 85 seconds.

-

[10]

Ripley, Brian and Venables, William (2 February 2016): R Package ‘nnet.’ Version 7.3-12. Consulted on 25 September 2019, <http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4/>.

-

[11]

She includes many other transformations under this label, some of them classified differently here (self-corrections, repetitions, adding qualifying remarks) and others not considered as substantial enough transformations for coding (adding conjunctions, replacing nominalizations with verb phrases).

Bibliography

- Abuín González, Marta (2007): El proceso de interpretación consecutiva. Un estudio del binomio problema/estrategia. Granada: Editorial Comares.

- Arumí Ribas, Marta (2012): Problems and Strategies in Consecutive Interpreting: A Pilot Study at Two Different Stages of Interpreter Training. Meta. 57(3):812-835.

- Bartlomiejczyk, Magdalena (2006): Strategies of simultaneous interpreting and directionality. Interpreting. 8(2):149-174.

- Becher, Viktor (2011): Explicitation and implicitation in translation. A corpus-based study of English-German and German-English translations of business texts. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Hamburg: University of Hamburg.

- Bendazzoli, Claudio and Sandrelli, Annalisa (2009): Corpus-based Interpreting Studies: Early Work and Future Prospects. Revista Tradumatica. 7:1-9.

- Bernardini, Silvia and Russo, Mariachiara (2017): Corpus linguistics, translation and interpreting. In: Kirsten Malmkjaer, ed. The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies and Linguistics. London/New York: Routledge, 342-356.

- Brezina, Vaclav (2018): Collocation graphs and networks. In: Pascual Cantos-Gómez and Moisés Almela-Sánchez, eds. Lexical Collocation Analysis. Berlin: Springer, 59-83.

- Chernov, Ghelly (1978): Teoriya i praktika sinkhronnogo perevoda [Theory and practice of simultaneous interpreting]. Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye Otnoshenija.

- Chernov, Ghelly (2004): Inference and anticipation in simultaneous interpreting: a probability-prediction model. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Chernov, Ghelly, Gurevich, A. E., et al. (1974): Metodika temporal’nogo analiza sinhronnogo perevoda po special’noj laboratornoj ustanovke [Methods of studying timing of simultaneous interpreting in a laboratory]. In: Nikolai S. Chemodanov, ed. Inostrannye Yazyki v Vysshej Shkole 9 [Foreign Languages in Tertiary Education]. Moscow: Vysshaja Shkola, 77-84.

- Chesterman, Andrew (1997): Memes of Translation: The Spread of Ideas in Translation Theory. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Dam, Helle (2001): On the option between form-based and meaning-based interpreting: the effect of source text difficulty on lexical target text form in simultaneous interpreting. The Interpreters’ Newsletter. 11:27-55.

- Dayter, Daria (2018): Describing lexical patterns in simultaneously interpreted discourse in a parallel aligned corpus of Russian-English interpreting (SIREN). FORUM. 16(2):241-264.

- Dayter, Daria (2020): Collocations in non-interpreted and simultaneously interpreted English: a corpus study. In: Lore Vandevoorde, Joke Daems, and Bart Defrancq, eds. New Empirical Perspectives on Translation and Interpreting. London/New York: Routledge, 67-91.

- De Feo, Nicoletta (1993): Strategie di riformulazione sintetica nell’interpretazione simultanea dall’inglese in italiano: un contributo sperimentale [Synthetic reformulation strategies in simultaneous interpretating from English into Italian: an experimental contribution]. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Trieste: University of Trieste.

- Englund Dimitrova, Birgitta (2005): Expertise and Explicitation in the Translation Process. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Ferraresi, Adriano and Miličević, Maja (2017): Phraseological patterns in interpreting and translation. Similar or different? In: Gert De Sutter, Marie-Aude Lefer, and Isabelle Delaere, eds. Empirical Translation Studies. New Methodological and Theoretical Traditions. Berlin: De Gruyter, 157-182.

- Friginal, Eric (2009): The Language of Outsourced Call Centers: A Corpus-based Study of Cross-cultural Interaction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Gile, Daniel (1995): Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Gile, Daniel (1999): Testing the Effort Models’ tightrope hypothesis in simultaneous interpreting—A contribution. HERMES. 12(23):153-172.

- Glémet, Roger (1958): Conference Interpreting. In: Andrew D. Booth, ed. Aspects of Translation. London: Secker and Warburg, 105-122.

- Gorokhova, Anna (2003): Sopostavitelnoe issledovanie sposobov dostizhenija ekvivalentnosti v sinkhronnom i pismennom perevodakh [Contrastive investigation of the means of achieving equivalence in simultaneous interpreting and translation]. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Moscow: Moscow State Linguistic University.

- Gran, Laura (1998): In-training development of interpreting strategies and creativity. In: Ann Beylard-Ozeroff, Jana Králová, and Barbara Moser-Mercer, eds. Translators’ Strategies and Creativity. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 145-162.

- Granhagen Jungner, Johanna, Tiselius, Elisabet, Blomgren, Klas, et al. (2018): The interpreter’s voice: Carrying the bilingual conversation in interpreter-mediated consultations in pediatric oncology care. Patient Education and Counseling. 102(4):656-662.

- Gumul, Ewa (2006): Explicitation in Simultaneous Interpreting: A Strategy or a By-product of Language Mediation? Across Languages and Cultures. 7(2):171-190.

- Hurtado, Amparo (1999): Enseñar a traducir. Madrid: Edelsa.

- Ilg, Gérard (1978): De l’allemand vers le français: l’apprentissage de l’interprétation simultanée. Parallèles. 1:69-99.

- Ilukhin, Vladimir M. (2001): Strategii v sinkhronnom perevode [Strategies in simultaneous interpreting]. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Moscow: Moskovskij Lingvisticheskij Universitet Druzhby Narodov.

- Ivanova, Adelina (2000): The use of retrospection in research on simultaneous interpreting. In: Sonja Tirkkonen-Condit and Riitta Jääskeläinen, eds. Tapping and Mapping the Processes of Translation and Interpreting. Outlooks on Empirical Research. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 27-50.

- Kader, Stephanie and Seubert, Sabine (2015): Anticipation, segmentation… stalling? How to teach interpreting strategies. In: Dörte Andres and Martina Behr, eds. To Know How to Suggest …: Approaches to Teaching Conference Interpreting. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 125-144.

- Kalina, Sylvia (1994): Analyzing interpreters’ performance: methods and problems. In: Cay Dollerup and Annette Lindegaard, eds. Teaching Translation and Interpreting 2: Insights, aims and visions. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 225-233.

- Kalina, Sylvia (1998): Strategische Prozesse beim Dolmetschen: theoretische Grundlagen, empirische Fallstudien, didaktische Konsequenzen [Strategic processes in interpreting: theoretical bases, empirical case studies, didactic implications]. Tübingen: Günter Narr.

- Kenny, Dorothy (2001): Lexis and Creativity in Translation: A Corpus-based Study. London/New York: Routledge.

- Kirchhoff, Helene (1976): Das Simultandolmetschen: Interdependenz der Variablen im Dolmetschprozess, Dolmetschmodelle und Dolmetschstrategien [Simultaneous interpreting: connection between the variables in the interpreting process, models of interpreting, and interpreting strategies]. In: Horst W. Drescher and Signe Scheffzek, eds. Theorie und Praxis des Übersetzens und Dolmetschens [Theory and practice of translation and interpreting]. Bern: Peter Lang, 59-71.

- Kohn, Kurt and Kalina, Sylvia (1996): The Strategic Dimension of Interpreting. Meta. 41(1):118-138.

- Kurz, Ingrid (1993): Conference interpretation: Expectations of different user groups. The Interpreter’s Newsletter. 5:13-21.

- Lederer, Marianne (1981): La traduction simultanée. Expérience et théorie. Paris: Lettres modernes Minard.

- Lörscher, Wolfgang (1991): Translation performance, translation process, and translation strategies. Tübingen: Narr.

- Malmkjaer, Kirsten (1993): Who can make Nice a better word than Pretty? In: Mona Baker, Gill Francis, and Elena Tognini-Bonelli, eds. Text and Technology. In honour of John Sinclair. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 213-232.

- Marco, Josep (2009): Normalisation and the Translation of Phraseology in the COVALT Corpus. Meta. 54(4):842-856.

- Martinez, Ron and Schmitt, Norbert (2012): A phrasal expressions list. Applied Linguistics. 33(3):299-320.

- Minyar-Beloruchev, Ryurik (1980): Obshaya teoriya perevoda i ustnyj perevod [General translation theory and oral interpreting]. Moscow: Voenizdat.

- Munday, Jeremy (2010): Introducing Translation Studies. Theories and Applications. London/New York: Routledge.

- Paquot, Magalie and Granger, Sylviane (2012): Formulaic Language in Learner corpora. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 32:130-149.

- Pearl, Stephen (1995): Lacuna, Myth and Shibboleth in the Teaching of Simultaneous Interpreting. Perspectives. 3(2):161-190.

- Piotrowsky, Rajmund (1968): Informacionnye izmereniya yazika [The informational dimension of language]. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Plevoets, Koen and Defrancq, Bart (2016): The effect of informational load on disfluencies in interpreting. Translation and Interpreting Studies. 11(2):202-224.

- Plevoets, Koen and Defrancq, Bart (2018): The cognitive load of interpreters in the European Parliament. Interpreting. 20(1):1-28.

- Plungyan, Vladimir (2005): Zachem nam nuzhen nacional’nyj korpus russkogo yazyka? [Why do we need a national corpus of Russian?]. In: Vladimir Plungyan,, ed. Nacional’nyj korpus russkogo yazyka 2003-2005 [Russian national corpus]. Moscow: Indrik, 6-20.

- Pöchhacker, Franz (2004): Introducing Interpreting Studies. London/New York: Routledge.

- Pöchhacker, Franz (2015): Segmentation. In: Franz Pöchhacker, ed. Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies. London/New York: Routledge, 367-368.

- Poluyan, Igor (2011): Kompressiya v sinkhronnom perevode [Compression in simultaneous interpreting]. Moscow: Valent.

- Pym, Anthony (2005): Explaining explicitation. In: Krisztina Károly and Àgota Fóris, eds. New Trends in Translation Studies: In Honour of Kinga Klaudy. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 29-43.

- Riccardi, Alessandra (1996): Language-specific strategies in simultaneous interpreting. In: Cay Dollerup and Vibeke Appel, eds. Teaching Translation and Interpreting 3. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 213-222.

- Riccardi, Alessandra (1998): Interpreting strategies and creativity. In: Ann Beylard-Ozeroff, Jana Králová, and Barbara Moser-Mercer, eds. Translators’ Strategies and Creativity. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 171-180.

- Riccardi, Alessandra (2005): On the evolution of interpreting strategies in simultaneous interpreting. Meta. 50(2):753-767.

- Russo, Mariachiara, Bendazzoli, Claudio, Sandrelli, Annalisa, et al. (2012): The European Parliament Interpreting Corpus (EPIC): implementation and developments. In: Francesco Straniero Sergio and Caterina Falbo, eds. Breaking Ground in Corpus-based Interpreting Studies. Bern: Peter Lang, 53-90.

- Sandrelli, Annalisa (2012): Interpreting Football Press Conferences: The FOOTIE Corpus. In: Cynthia J. KellettBidoli, ed., Interpreting across Genres: Multiple Research Perspectives. Trieste: EUT Edizioni Università di Trieste, 78-101.

- Sandrelli, Annalisa, Bendazzoli, Claudio, and Russo, Mariachiara (2010): European Parliament Interpreting Corpus (EPIC): Methodological Issues and Preliminary Results on Lexical Patterns in Simultaneous Interpreting. International Journal of Translation Studies. 22(1-2):167-206.

- Seeber, Kilian G. (2001): Intonation and anticipation in simultaneous interpreting. Cahiers de linguistique francaise. 23:61-97.

- Seleskovitch, Danica and Lederer, Marianne (1989): Pédagogie raisonnée de l’ interprétation. Paris: Didier Éru-dition.

- Setton, Robin (1999): Simultaneous Interpretation: A cognitive-pragmatic analysis. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Setton, Robin (2002): Meaning assembly in simultaneous interpretation. In: Franz Pöchhacker and Miriam Shlesinger, eds. The Interpreting Studies Reader. London/New York: Routledge, 178-202.

- Setton, Robin (2005): So what is so interesting about simultaneous interpreting? Journal of Translation and Interpretation. 1(1):70-85.

- Shiryaev, Anatolij (1979): Sinkhronnyj perevod. Dejatel’nost’ sinkhronnogo perevodchika i metodika prepodavanija sinkhronnogo perevoda [Simultaneous interpreting. Interpreter practices and didactics of simultaneous interpreting]. Moscow: Voennoe izdatelstvo Ministerstva Oborony SSSR.

- Shveitser, Aleksandr (1988): Teoriya perevoda [Translation theory]. Moscow: Nauka.

- Straniero Sergio, Francesco and Falbo, Caterina (2012): Studying interpreting through corpora. An introduction. In: Francesco Straniero Sergio and Caterina Falbo, eds. Breaking Ground in Corpus-based Interpreting Studies. Bern: Peter Lang, 9-52.

- Sunnari, Marianna (1995): Processing strategies in simultaneous interpreting: “saying it all” vs. synthesis. In: Jorma Tommola, ed. Topics in Interpreting Research. Turku: University of Turku, Centre for Translation and Interpreting, 109-119.

- Tang, Fang (2018): Explicitation in Consecutive Interpreting. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Toury, Gideon (1995/2012): Descriptive translation studies—and beyond. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Van Besien, Fred (1999): Anticipation in Simultaneous Interpretation. Meta. 44(2):250-259.

- Vančura, Alma (2017): Speech characteristics as progress indicators in simultaneous interpreting by trainee interpreters. Govor. 34(1):3-32.

- Venables, William and Ripley, Brian (2002): Modern Applied Statistics with S. New York: Springer.

- Viaggio, Sergio (1992): Translators and interpreters: Professionals or shoemakers. In: Cay Dollerup and Anne Loddegaard, eds. Teaching Translation and Interpreting. Training, Talent and Experience. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 307-312.

- Vinay, Jean-Paul and Darbelnet, Jean (1958/2004): A methodology for translation. (Translated from French by Juan C. Sager and Marie-Josée Hamel) In: Lawrence Venuti, ed. The Translation Studies Reader. 2nd ed. London/New York: Routledge, 128-137.

- Visson, Lynn (1991): From Russian into English. An introduction to simultaneous interpretation. Ann Arbor: Ardis Publishers.

- Vitrenko, Anatolij G. (2008): O strategii perevoda [On the translation strategies]. Vestnik MGLU. 536:3-17.

- Zimnyaya, Irina and Chernov, Ghelly (1973): Verojatnostnoe prognozirovanie v processe sinkhronnogo perevoda [Probabilistic anticipation in the process of interpreting]. In: A. A. Leontiev, N. I. Zhinkin, A. M. Shahnarovich, eds. Predvaritel’nye materialy eksperimental’nykh issledovanij po psiholingvistike [Drafts of experimental studies in psycholinguistics]. Moscow: Akademija Nauk, 110-116.

- Øverås, Linn (1998): In Search of the Third Code: An Investigation of Norms in Literary Translation. Meta. 43(4):557-570.

List of figures

Figure 1

Distribution of strategies in the interpreted speech events

Figure 2

Pre-patterned chunks in SI excerpts

Figure 3

Interpreting strategies vs. phraseological richness

List of tables

Table 1

Eight generalized simultaneous interpreting strategies with examples[2]

Table 2

SIREN size and composition

Table 3

Frequency distribution of strategies in the sample

Table 4

Strategies in the interpreted speech events

Table 5

Degree of phraseological richness per strategy used

10.7202/1017092ar

10.7202/1017092ar