Abstracts

Abstract

The European Commission recently reformed the statutory audit market in order to improve its competitiveness. We employ resource dependence theory to understand the position of audit firms with regard to the policy options considered. By using content analysis to examine consultation responses, we show that, despite the existing market segmentation, all sizes of firm adopt similar positions, except on the topic of audit consortia. The differences in firms’ access to resources, particularly with respect to human capital, help to explain these positions, which perpetuate supply concentration in the market.

Keywords:

- European reform,

- market structure,

- audit firms,

- resource dependence theory

Résumé

La Commission européenne a récemment mené une réforme de l’audit légal afin d’améliorer la compétitivité du marché. Nous mobilisons la théorie de la dépendance vis-à-vis des ressources afin de comprendre la position des cabinets d’audit au regard des options politiques envisagées. A partir d’une analyse de contenu des réponses à une consultation, les résultats montrent qu’en dépit d’une segmentation de marché existante, toutes les tailles de cabinet adoptent des positions similaires, excepté sur les consortiums d’audit. Les différences d’accès aux ressources entre types de cabinet, notamment en capital humain, permettent de comprendre ces positions qui pérennisent la concentration de l’offre.

Mots-clés :

- réforme européenne,

- structure de marché,

- cabinets d’audit,

- théorie de la dépendance vis-à-vis des ressources

Resumen

La Comisión Europea ha realizado recientemente una reforma en materia de auditoría legal con el fin de mejorar la competencia de ese mercado. Movilizamos la teoría de dependencia de recursos con el fin de entender la posición de las firmas de auditoría en relación con las opciones políticas consideradas. A partir de un análisis de contenido de respuestas a una consulta, los resultados muestran que, a pesar de una segmentación de mercado existente, los distintos tamaños de firmas adoptan posiciones similares, con excepción de la auditoría de consorcio. Las diferencias de acceso a los recursos entre las diferentes firmas, sobre todo en capital humano, permiten entender esas posiciones que sostienen la concentración de la oferta.

Palabras clave:

- Reforma europea,

- estructura de mercado,

- firmas de auditoría,

- teoría de la dependencia de recursos

Article body

In 2010, in response to the financial crisis, the European Commission (EC) embarked on a reform of European statutory audit policy.[1] In order to identify the changes required to be made in this area, it launched a public consultation in October 2010 in the form of a Green Paper entitled “Audit Policy: Lessons from the Crisis” (European Commission, 2010). The EC primarily underlined its concerns regarding both the extreme concentration of the audit market, which it noted had arisen through “the consolidation of large firms into even larger firms” over the past two decades (European Commission, 2010, p. 4), and the systemic risk presented by the dominant position of each of the Big Four.[2] The specificities of the audit market determine the structure of the offer, which is often presented as segmented and concentrated (Moizer, 1992; Cabán-García and Cammack, 2009). In this context, regulation is a means of homogenising competition and of reducing the market distortion induced by the dominance of the Big Four (Hogan and Martin, 2009; Cassell et al., 2013; Bills and Stephens, 2016). To this end, the Green Paper set out several policy options with the objective of dynamising market structures in the European Union (EU). These policies were designed to reduce barriers to entry and to significantly change the distribution of audit assignments between firms, thereby affecting market share. Due to the potential changes in practice engendered, audit firms were the stakeholder most directly affected by the proposed reform and, as such, they were the dominant type of respondent in the consultation studied (45% of the responses received by the EC). The purpose of this article is to analyse the position[3] of these audit firms with respect to the policy options proposed by the EC.

To achieve this aim, we collected audit firms’ responses to the Green Paper consultation. This type of data is often used in the literature to study the participation of stakeholders in accounting standard-setting processes (Georgiou, 2004; Königsgruber, 2010; Orens et al., 2011). Such analyses have mainly been performed in national, and mostly Anglo-Saxon, contexts (Ang et al., 2000; Standish, 2003; Georgiou, 2004; Jorissen et al., 2012; Hoffmann and Zülch, 2014). Other authors have analysed this participation with respect to the international accounting standards developed by the IASB (International Accounting Standards Board) (Giner and Arce, 2012; Jorissen et al., 2012; Le Manh, 2012). These studies mainly relate to private-sector accounting regulators (Orens et al., 2011), although some articles examine national public systems (McLeay et al., 2000; Hoffmann and Zülch, 2014). In addition, they focus on the stakeholders that are the most active during consultations, namely the preparers of the financial statements (Ang et al., 2000; Georgiou, 2004; Orens et al., 2011) and the accounting profession (audit firms in particular), generally considering the profession to be a homogeneous group (Deegan et al., 1990; McKee et al., 1991; Meier et al., 1993), despite it comprising actors with varied, or even opposing, interests (Colasse and Standish, 1998). To the best of our knowledge, this is therefore the first time that a study in this field has focused on a regulatory process initiated by an international public body such as the EC, while simultaneously considering audit firms as three types of actors with individual interests: the Big Four, mid-tier audit firms with an international network (MAFs) and small audit firms (SAFs).[4]

In order to understand how these three types of firm have participated in the European regulatory process for statutory audit, we analyse six themes from the Green Paper relating to the EC’s desire to dynamise the market: the appointment of auditors, the audit firm rotation, pure audit firms, the financial weight of individual clients, supervisory mechanisms and audit consortia. We use detailed content analysis (Ang et al., 2000) of consultation responses to examine the positions (favourable/neutral/unfavourable) and arguments of these three types of firm in relation to the policy options set out in the Green Paper for the six themes selected. Despite the existing market segmentation, our results show that the three types of firm take similar positions on these policy options, with the exception of the issue of audit consortia, where the Big Four are the only firms unfavourable to the policy option formulated by the EC. With respect to the arguments put forward by the respondents, resource dependence theory is used both to analyse the positions of the three types of firm (Pennings et al., 1998; Bröcheler et al., 2004) and to understand the dynamics of audit market structure (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 2001).

The first section of our article presents the theoretical framework used to examine the structure of the audit market. The second section describes the context and the methodology employed. The third section presents our results on the position of the three types of audit firm in relation to the policy options in the Green Paper. Finally, the fourth section highlights the contributions of our research.

Structure of the Audit Market

The main objective of the reform studied was to improve the functioning of the audit market. Longitudinal studies on the evolution of audit market structure reveal the concentration and segmentation of supply; in particular, the Big N are found to dominate the listed companies segment, which weakens free market competition (Cabán-García and Cammack, 2009; Steponavičiūtė and Zvirblis, 2011). This situation threatens audit quality and/or generates increased costs for the companies audited. From an empirical point of view, an increasing number of voices (regulators, professional bodies, clients) have criticized the level of audit market concentration and its potential consequences on economic performance and the public interest (Eshleman and Lawson, 2017). In Europe, the concentration ratios for listed companies varied between 83% and 100% for the year 2004[5] (London Economics and Ewert, 2006, p. 71). Local analyses of audit market structures also show that the market is generally segmented (Niemi, 2004; Ghosh and Lustgarten, 2006). In addition, Carson et al. (2014) show that the Big N maintained their undivided market share for the largest listed companies over the period 2000-2011, although their market share for small and medium-sized enterprises fell. SAFs maintained their market share for small enterprises over the period, while mid-tier audit firms and the largest non-Big N audit firms were the only ones to increase their market share, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises.

From a theoretical point of view, the industrial economy can be used to analyse the influence of market concentration. Ivaldi et al. (2003), for example, highlight the main theoretical factors facilitating the collusion that leads to oligopoly. First, a reduced number of supply-side actors facilitates coordination and makes the relative share of the potential return more attractive. In addition, high barriers to entry, whether technical, educational or regulatory, tend by their very nature to facilitate an oligopoly. Finally, a market with low demand elasticity and little innovation (mature market) facilitates collusion and the creation of an oligopoly. In summary, concentration helps sustain oligopolies, either directly by increasing individual firms’ profits and mitigating coordination problems, or indirectly as a reflection of existing barriers to entry (Levenstein and Suslow, 2006).

Although the audit market displays real concentration in the listed companies segment, it is nonetheless difficult to qualify the specific characteristics of this concentration. Numerous studies (Moizer, 1992) point out that the dominance of the Big N is based primarily on the fact that large listed companies need to be able to rely on audit firms with considerable resources and a higher level of perceived quality. Moizer (1992) therefore notes that to be able to analyse this market we first of all need to understand the audit profession. In particular, he highlights the difficulty of assessing audit quality, the fragility of the auditor’s independence given that the auditor is appointed and remunerated by the audited entity, and finally the fact that the profession has many characteristics that effectively act as barriers to entry. Mandatory professional qualifications, restrictions on advertising and a culture of confidentiality are all barriers that create a monopoly situation in the profession as a whole, but they can also lead to monopolies within the profession by isolating practitioners from one another and making client companies less price-sensitive than they otherwise would be. Byington et al. (1990) reinforce this idea by specifying that the decision to choose a service in this market, normally motivated by perceptions of the utility of the service at the market price, is altered. In general, a professional monopoly reduces clients’ ability to differentiate the levels of service quality provided by members of the profession. This lack of information, and the resulting inability to assess service quality, then creates a brand substitution effect based on reputation, in the specific case of the Big N, which contributes to a strengthening of market segmentation.

Due to the simultaneous regulation of supply and demand, the audit market is unlikely to conform to all the archetypes of the industrial economy (Huber, 2015). This is explained on the supply side by the various barrier-to-entry issues and on the demand side by the fact that demand stems entirely from regulatory constraints. These two phenomena create a combined inelasticity of supply and demand that is contrary to the presuppositions of the industrial economy, revealing structural dynamics specific to this market. It is possible to imagine non-segmented competition (Bills and Stephens, 2016) created by both specific strategies and regulation. Simons and Zein (2016), for example, show that the flexibility required for the audit of large international groups in fact allows non-Big N to gain market share. In a Chinese context, Wang et al. (2011) highlight that the industry specialisation of non-Big N may enable some of these firms to attract large companies and obtain fees equivalent to those of the Big N. Other studies show the importance of the regulatory framework. In the United States, in the period following the fall of Arthur Andersen, the implementation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the creation of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), the client portfolios of second-tier audit firms increased considerably (Hogan and Martin, 2009). Regulators have encouraged companies to use this type of firm, thereby helping to increase the perceived quality of such firms (Cassell et al., 2013).

Similarly, one of the main challenges of the audit reform initiated by the EC in 2010 was to dynamise the market and harmonise competition. It is therefore interesting to observe how audit firms positioned themselves in relation to the policy options set out in the Green Paper (European Commission, 2010). In the light of the theoretical elements presented above, and given the pre-existing market structure, it is important to question whether the three types of firm (Big Four, MAFs and SAFs) took convergent or divergent positions on the EC proposals designed to dynamise competition in the audit market.

Methodology

European Context[6]

The work of the EC is performed by a College of 28 Commissioners (one per Member State) responsible for various Directorates-General, such as the Directorate-General for Internal Market. Through its Commissioners, it has a monopoly on initiating reforms at an EU level. These reforms must always be based on defending the European general interest. However, this interest may not always be in line with the interests of the Member States or the industries concerned by the reforms. The legislative proposals initiated by the EC are therefore discussed in “trilogue” meetings (EC and the two co-legislators: the Council of the EU[7] and the European Parliament[8]) and can be rejected or adopted jointly by the Council of the EU and the European Parliament on a strictly equal footing. The EC’s main mission in areas related to the European market is to strengthen its efficiency by facilitating the free movement of goods and services between Member States. To this end, it applies the principle of subsidiarity, which involves ensuring that actions are undertaken at an EU level if they have more positive consequences and greater chances of success than action at a national level.

When the EC is considering reform, it firstly needs to identify the European general interest. To this end, it must consult stakeholders and take their views into account. Virtually all[9] reforms therefore start with a public consultation to which all stakeholders are invited to respond. In order to avoid misdiagnosis, these consultations firstly question stakeholders on whether the problem at the origin of the potential EC reform actually exists. The EC then asks them to express their views on the potential policy options that could be used to remedy the problem identified. All of the consultation responses are read in full and summarised before being analysed using computerised data analysis tools. These consultations help the EC to develop measures acceptable to the majority of stakeholders, thus providing it with the necessary arguments to defend its reform proposal before the two co-legislators. These consultations also provide elements that enable the EC to maintain its initial opinion when stakeholders’ positions are fragmented. The consultations may, additionally, help the EC to identify alternative policy options. Finally, the EC completes its legislative proposals with an impact assessment in which it justifies its position on the basis of the arguments put forward by certain stakeholders. It is therefore essential for the EC that the consultation responses are substantiated.

The Green Paper on audit reform published in October 2010 is an example of the public consultations performed by the EC. Its aim was to examine relevant policy options in order “to explore the possibilities to reduce existing barriers to entry into the audit market” (European Commission, 2010, p. 4). All stakeholders were invited to send their responses to the EC by email between 13 October and 8 December 2010.

Identification of Policy Options Proposed by the EC

The public consultation was based on the 38 questions set out in the Green Paper. Some of them question the very existence of a problem related to audit practice rather than the policy options being considered to address it (for example, Q27: Could the current configuration of the audit market present a systemic risk?). Other questions, although related to the objectives identified, do not refer to a specific policy action envisaged by the EC, and are formulated in an open manner (for example, Q23: Should alternative structures be explored to allow audit firms to raise capital from external sources?). As the objective of our study is to analyse the position of audit firms on specific policy options proposed by the EC, we did not retain this type of question. In addition, some of the questions referring to a specific policy option do not relate to audit market structure (for example, Q11: Should there be more regular communication by the auditor to stakeholders? Also, should the time gap between the year end and the date of the audit opinion be reduced?). In light of our research question, we also eliminated these questions. We ultimately selected eight questions, each relating to a specific policy option proposed by the EC to dynamise the audit market. Our analysis of audit firms’ positions and arguments is based on their responses to these eight questions, which we have grouped under the following six themes:

Appointment of auditors: the Green Paper emphasises the essential role of the auditor appointment process in improving market structure. The fact that the auditors are “appointed and paid by the (…) audited company creates a distortion within the system” that needs to be reduced (European Commission, 2010, p. 11). The EC therefore questioned whether this appointment could be made by a third party, such as a regulator. This solution could be particularly relevant for opening the market of exclusively Big Four audited companies to other types of audit firm (MAFs and in some cases SAFs).

Audit firm rotation: a study performed by London Economics and Ewert (2006, p. 43) at the request of the EC revealed that 33% of respondents[10] had retained the same auditor for more than ten years. This percentage reached 45% for respondents whose turnover exceeded 10 billion euros. In response to these findings, the Green Paper proposed the mandatory rotation of audit firms after a given period of time, which could “operate as a catalyst to introduce more dynamism and capacity into the audit market” (European Commission, 2010, p. 16). We note that the 8th European Directive of 2006 already requires the rotation of key audit partners from the same firm (Official Journal of the European Union, 2006).

Pure audit firms (prohibiting the combination of audit and non-audit services): Cox (2006) notes that since the 2000s, the fees received from non-audit services have been approximately twice as high as those from audit services. In terms of the Big N, Cox (2006) explains that “Their great competitive advantage over non-auditing consulting firms was that the accounting firms could bundle their audit function with their consulting services.” Less profitable audit assignments thus help firms to “sell” more lucrative consulting assignments. As a result, in addition to dominating the audit market, the Big Four are now ranked among the ten largest consulting firms in the world. In this context, the Green Paper proposed “reinforcing the prohibition of non-audit services by audit firms” leading to the creation of pure audit firms (European Commission, 2010, p. 12). Existing firms would then be forced to position themselves on a single type of offer (audit or non-audit).

Financial weight of individual clients: in order to limit the financial dependence between the auditor and the audited entity, the EC proposed regulating “the proportion of fees an audit firm can receive from a single audit client compared to the total audit revenues of the firm”. On this point, the Green Paper refers to the International Federation of Accountants’ (IFAC) Code of Ethics (IFAC, 2009), which requires the auditor of a public interest entity (PIE) to disclose situations where the total fees received from a client in each of the last three financial years represent more than 15% of the total fees received by the firm in those years (European Commission, 2010, p. 12).

Supervisory mechanisms: in its Green Paper, the EC opened a debate on strengthening the supervisory mechanisms for audit firms in Europe. It emphasised the role of such mechanisms in improving the functioning of the European audit market, “Any market configuration should be accompanied by an effective supervisory system which is fully independent from the audit profession. Structural changes within global networks should not be allowed to result in any gaps or exclusions from oversight.” (European Commission, 2010, p. 4) Two solutions were considered: transforming the current European Group of Auditors’ Oversight Bodies (EGAOB) into a so-called “Lamfalussy Level 3 Committee”,[11] or establishing a new European Supervisory Authority.

Audit consortia: according to the EC, the establishment of audit consortia (or joint audits) could be an effective way of reducing audit market concentration and thus of “mitigating disruption (…) if one of the large audit networks fails”. The Green Paper explains that “To encourage the emergence of other players and the growth of small and medium sized audit practices, the Commission could consider introducing the mandatory formation of an audit firm consortium with the inclusion of at least one non-systemic audit firm for the audits of large companies.” (European Commission, 2010, p. 16)

Table 1 presents the policy option formulated by the EC for each theme, as well as the relevant Green Paper question(s) selected for the analysis.

Table 1

Questions and policy options formulated by the EC on the six themes

Data Selection and Coding

We performed a content analysis (MacArthur, 1988; Ang et al., 2000; Giner and Arce, 2012) of the consultation responses to the Green Paper. We collected 688 responses written by all types of stakeholder, which amounted to more than 10,000 pages, a record response rate for EC consultations. Just over 45% (310 responses) were from audit firms, the most prominent respondents, far ahead of financial statement preparers, professional institutions, public authorities, academics, financial statement users, audit committees and individuals. As the purpose of the reform was to change audit practices, it is natural that audit firms were the most highly represented stakeholder in the consultation. However, this result is specific to the EU context; preparers dominate in other contexts (Giner and Arce, 2012; Jorissen et al., 2012; Le Manh, 2012).[12]

Not all of the 310 responses prepared by audit firms address every question in the Green Paper. We retained only those responses that refer to at least one of the eight questions selected for this study. We therefore analysed the contents of 268 responses.

The responses were coded using evaluation coding[13] (Saldaña, 2016) performed using NVivo qualitative data analysis software. In order to code the content of the responses, we imported them into the software and then identified the following attributes for each response:

“type of firm” indicates the type of audit firm (Big Four, MAF or SAF);

“country” indicates the respondent’s country of origin in the case of SAFs. Firms operating on an international scale (Big Four and MAFs) were classified as “international”.

We then coded the content of the responses to the eight questions in function of the respondent’s position on the policy option proposed by the EC (see Table 1 for the policy options proposed by the EC). Individual responses were coded as “favourable” if the respondent was predominantly in favour of the policy option proposed by the EC or as “unfavourable” if the respondent was predominantly against the policy option proposed by the EC (see Table 2a). We also note that some responses simultaneously proposed arguments in favour of and against the policy option proposed by the EC. Such responses were coded as “neutral” when the favourable and unfavourable elements were balanced (see Table 2b).

Finally, we coded the arguments developed by respondents to support their positions. We identified two types of argument in this coding: the motives justifying respondents’ positions and alternative proposals used to suggest different policy options (see Table 2a). We note that the responses we analysed were not always substantiated – some respondents merely indicated their position without justification, while others indicated their motives and/or proposals.

Out of the 268 responses analysed, 205 were prepared by German SAFs in a strictly identical format. Previous studies analysing consultation responses have systematically treated similar responses as a single response (Chatham et al., 2010; Hodder and Hopkins, 2014).[14] We adopted the same approach, and therefore coded 64 responses.

Table 2a

Example of coding of a Big Four response (Deloitte) on the theme of pure audit firms

Table 2b

Illustration of the “neutral” position for each of the six themes

Data Analysis

We firstly performed a descriptive analysis of the data based on the 268 audit firm responses. This analysis involved presenting respondents’ geographical origin and the proportion of each of the three types of audit firm.

We then performed a content analysis of the 64 responses coded in NVivo (treating the 205 identical responses from German SAFs as a single response). This analysis was performed in two steps. We firstly prepared cross tabulations (Tables 4a to 4f) to show the number of responses according to the type of audit firm (Big Four, MAF, SAF) and the respondent’s position (favourable/neutral/unfavourable) for each of the six themes. We then extracted verbatim quotes from the coded responses to illustrate the “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions for each type of audit firm and to highlight the arguments employed by respondents.

Audit Firms’ Positions and Arguments on the Reform

Descriptive Analysis of Audit Firm Responses to the Consultation

The distribution of audit firm responses by geographical origin of the respondent and type of firm is presented in Table 3.

Analysis by Geographical Origin of Respondent

Of the 268 audit firm responses, 4.85% were formulated by stakeholders with international interests (Big Four and MAFs). All of the SAFs participating in the consultation were located in EU Member States and were from only eight different countries. We emphasize that the vast majority of SAF responses (86.57%) were prepared by German firms. The responses from SAFs originating in other Member States represent, by country, less than 3% of all audit firm responses.

Analysis by Type of Audit Firm

The Big Four firms all participated individually in the consultation, contributing a total of four responses (each prepared on behalf of the particular firm’s entire international network). MAFs sent a total of nine responses, while SAFs sent 255 responses (including the 205 identical responses from German SAFs). These two types of firm were especially interested in the debate as one of the fundamental objectives of the reform proposed by the EC was to open up the audit market, in particular the market for listed companies, the most concentrated segment. The potential market share to be gained is a major challenge for these firms, explaining their significant participation in the consultation process.

Table 3

Distribution of audit firm responses by geographical origin of respondent and by type of firm

Thematic Analysis of Audit Firm Responses to the Consultation

Appointment of Auditors

The EC proposed that auditors should be appointed by a third party. Tables 4a, 5a and 6a present the results for this theme.

The Big Four were unanimously opposed to this policy option. Instead, they proposed strengthening the role of the audit committee in the appointment of auditors. PwC, for example, explained that “the key issue is for the audit committee, made up of independent non-executives, to recommend the appointment to the board”. EY suggested methods for strengthening the role of the audit committee, “In order to better equip audit committees to perform an expanded role, guidelines should be prepared at the EU level that help them to evaluate the performance and independence of the auditor. Consideration also should be given to requiring audit committees to conduct periodic evaluations of audit quality in determining whether there is a need to re-tender the audit, and to explain why they have not re-tendered the audit after more than a set period of years.” In short, the Big Four wanted to leave the final choice to the shareholders, the owners of the company, as explained by Deloitte, “the final decision to appoint an auditor should remain with the general meeting of shareholders, as owners of the company and the first line of users of the audited financial statements”.

Although the EC considered this policy option to be a particularly relevant solution for opening the market to non-Big Four, the MAFs were also unanimously opposed to it. Like the Big Four, they suggested strengthening the role of the audit committee in the auditor appointment process. BDO referred to the fact that, as owners of the company, shareholders must retain their decision-making role, “we believe that the final decision to appoint an auditor should remain with the general meeting of shareholders, as owners of the company and as primary users of the audited financial statements”. RSM international noted that “The entity has a clearer understanding of the specialist knowledge and skills that the auditor needs to perform the audit effectively and may therefore make more suitable audit appointments than a third party.” Finally, it should be noted that only two MAFs referred to the impact of this reform on the audit market. HLB International noted a negative impact without arguing its position, “We are strongly opposed to shareholder panels for the appointment of auditors as we believe that this may lead to further market concentration.” Nexia International, on the other hand, anticipated that the market would become more open if the role of the audit committee were strengthened, “We believe that the Commission should investigate the possibility of establishing an independent body to work with audit committees in reviewing their audit appointment procedures, with an explicit agenda of ensuring (…) [a] reduction in market concentration.” Like HLB International, Nexia International did not justify its position.

The majority of SAFs were also opposed to the auditor being appointed by a third party (68%). The justifications again relate to the fact that, as its owners, the company’s shareholders must be responsible for this appointment (Kingston Smith). Firms also referred to a potential increase in the role of audit committees in the appointment process (RSM). The firm BMA explained that this policy option “would bureaucratise the profession and make it even less attractive” and instead proposed mandatory calls for tenders. Compared to the other types of firm, SAFs represent the category with the highest number of favourable responses (16%). On the other hand, none of them justify their position. Finally, 14% of the SAFs (including the German SAFs that prepared a joint response) had a neutral opinion. In their joint response, the German SAFs highlighted the advantages and disadvantages of this policy option, with the majority explaining that “A regulating authority (…) could assume the task of terminating the oligopoly of the Big Four without unsettling the financial market. The regulating authority would, e.g., transfer selected orders from the previous Big Four company to other, legally and economically independent audit firms.” This regulatory authority would be limited in its transfer capacity due to the number of MAFs and SAFs actually capable of auditing PIEs. Thus, in the case of PIEs, further reflection would be required before any legislation could be passed. Conversely, for unlisted companies, it does not seem necessary for auditors to be appointed by a third party.

Table 4a

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of the appointment of auditors[15]

The dominant position is in bold. The position of the German SAFs that prepared a joint response is shown in italics.

Table 5a

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of the appointment of auditors

Table 6a

Arguments on the theme of the appointment of auditors

Audit Firm Rotation

Tables 4b, 5b and 6b present the results relating to the audit firm rotation, in response to the EC’s proposal of mandatory rotation after a given period.

The Big Four unanimously and strongly opposed the mandatory rotation of audit firms, as illustrated by PwC’s response, “No, we believe that proposals to limit the continuous engagement of audit firms are inadvisable because the potential benefits are not justified by the risks to the quality of audit.” The arguments of the Big Four converged strongly and referred specifically to the experience of rotation in Italy, “As a tool to address the issue of audit market concentration, experience in Italy clearly shows that mandatory audit firm rotation has little to no effect.” (EY) The Big Four explained that this rotation “ could then simply lead to a game of ‘musical chairs’ between the largest audit firms and may therefore not achieve the Commission’s objectives” (KPMG). In addition, they argued that this would lead to a reduction in audit quality (since auditors need a sufficient induction period to fully understand the company) and to additional costs. They therefore proposed maintaining the rotation of audit partners rather than of audit firms.

Table 4b

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of the audit firm rotation

The dominant position is in bold. The position of the German SAFs that prepared a joint response is shown in italics.

Table 5b

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of the audit firm rotation

Table 6b

Arguments on the theme of the audit firm rotation

Although the EC considered this policy option to be a way of opening the market to non-Big Four, almost all MAFs were against it (89%). HLB International, for example, explained that “We are not in favour of the mandatory rotation of audits (...) [the] rotation of partners is a sufficient safeguard”. Like the Big Four, they considered that this policy option would not open up the audit market and that rotation would only take place between the Big Four (the Italian context is mentioned). MAFs favoured the option of a tendering process rather than mandatory rotation (Grant Thornton, Kreston International).

Similarly, most SAFs opposed the mandatory rotation of audit firms (59%). Although many SAFs recognised a potentially positive impact on market concentration, the risk of undermining audit quality and increasing costs led them to oppose this policy option, “The decision making processes of those charged with governance, should be based solely on audit quality and should not be a tool for achieving a less concentrated audit market.” (Crowe Clark Whitehill) German firm PKF Fasselt Schlage, for example, indicated that “in terms of the rotation of audit firms, the disadvantages outweigh the advantages”. Compared to the other types of firm, SAFs were nevertheless the least opposed to this policy option, with almost half of them adopting a neutral (15%, including the German SAFs that prepared a joint response) or favourable position (26%). However, very few arguments were presented in the responses to justify these opinions.

Pure Audit Firms

The EC proposed creating pure audit firms. Tables 4c, 5c and 6c present the results for this theme.

Table 4c

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of pure audit firms

The dominant position is in bold. The position of the German SAFs that prepared a joint response is shown in italics.

Table 5c

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of pure audit firms

Table 6c

Arguments on the theme of pure audit firms

The Big Four were unanimously opposed to the creation of pure audit firms. EY stated that “No, audit firms should not be prohibited from providing permissible non-audit services either to their audit clients or to their non-audit clients.” They noted that the 8th European Directive of 2006 (2006/43/EC) satisfactorily limits the combination of audit and non-audit services (Official Journal of the European Union, 2006) and argued that there is therefore no need to create pure audit firms. They also referred to the IFAC Code of Ethics, which already limits certain combinations of services (IFAC, 2009). They considered that the safeguarding role in relation to the combination of audit and non-audit services should not be played by the EC through new regulation, but should be the responsibility of the audit committee. The Big Four unanimously stated that non-audit engagements improve technical competence, “Complex audits require the expertise and competencies of multi-disciplinary teams (including, for example, actuaries and information system specialists) who are up-to-date with market techniques. These teams can simply not be maintained through audit-only experience.” (Deloitte) Finally, the Big Four pointed out that such non-audit services made them more attractive from a recruitment perspective.

Although the EC suggested that the creation of pure audit firms could be a lever with which to open the market to non-Big Four firms, the majority of MAFs were also opposed to this proposal (89%). BDO accordingly noted that “We do not support any proposal to move towards a situation of ‘audit-only’ firms, which we believe would damage the sustainability of the profession.” For these firms, being able to provide non-audit services allows them to survive in a market dominated by the Big Four. In addition, like the Big Four, they consider that these engagements increase their understanding of the audited entity. Finally, many MAFs also referred to the IFAC Code of Ethics, which they consider sufficient to limit non-audit services.

The SAFs adopted a more nuanced position. A small majority (55%) opposed this policy option, including British firm PKF (UK) LLP, which stated that “We do not consider that the provisions of non-audit services by audit firms should be prohibited (…). Taking this a step further to create audit only firms could impact on the ability of the professions to recruit, retain and develop staff with the balance of necessary skills.” The SAFs frequently referred to the IFAC Code of Ethics, which they consider to be sufficiently binding. The remaining SAFs were split equally between favourable (24%) and neutral (21%) positions. Nevertheless, the favourable responses from SAFs contain no arguments to support their position.

Financial Weight of Individual Clients

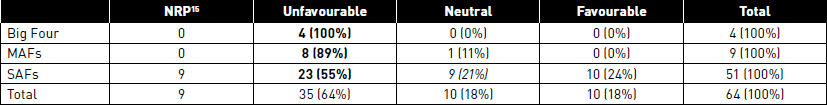

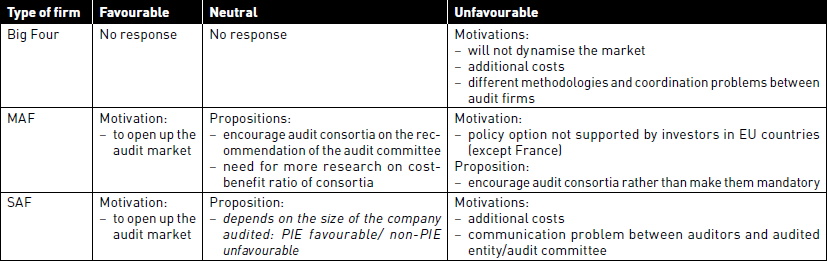

Tables 4d, 5d and 6d present the results related to limiting the financial weight of individual clients.

The Big Four and MAFs were unanimously in favour of the policy option formulated in the Green Paper, given that the threshold proposed by the EC did not exceed the threshold set out in the IFAC Code of Ethics (IFAC, 2009). These firms were already applying the limits recommended in the Code.

The SAFs were the least supportive of this policy option, with the firm Davreux et associés explaining that “The larger the audit firm, the smaller the relative weight of an individual client’s fees.” This policy option would therefore be more restrictive for small firms. Almost 40% of SAFs adopted a neutral (15%) or unfavourable (24%) position. Without proposing alternative solutions, these firms mentioned the problems posed by this policy option when setting up a new audit firm and explained that priority should be given to addressing the phenomenon of downward pressure on fees, “The problem is more related to the prevention of low-balling.” (Harald Keller) Most SAFs (61%) were nonetheless favourable to this policy option, referring to the threshold in the IFAC Code of Ethics or to existing national thresholds.

Supervisory Mechanisms

Tables 4e, 5e and 6e present the results on the EC’s proposed policy option to increase supervisory mechanisms.

The Big Four and the MAFs were unanimously in favour of enhanced cooperation between the competent national authorities. All of the Big Four referred to transforming supervision into a Lamfalussy Level 3 Committee, as shown in PwC’s response, “We are supportive of the transformation of the EGAOB into a Lamfalussy Level 3 Committee.” Although this committee is regularly mentioned in the MAF responses, some firms limited their responses to strongly encouraging improved communication between auditors of financial companies and the regulators, without specifying the modalities. BDO, for example, suggested “that the European Union consider establishing a well-resourced, pan-European body to promote harmonisation and cooperation among the national auditor oversight bodies in Member States”.

SAFs were the least supportive of the proposal to strengthen audit supervisory mechanisms, some considering the current mechanisms to be sufficient, others arguing for regional rather than European supervision. Nonetheless, more than half of SAFs (56%) responded favourably to this policy option. Of these firms, Crowe Clark Whitehill LLP was one of only two firms to advocate transforming the EGAOB into a Lamfalussy Level 3 Committee, in order “to provide a high level supervision of national regulators”.

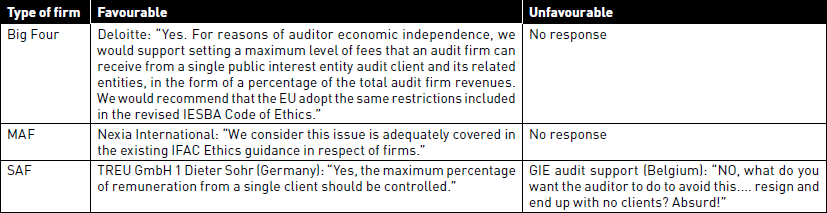

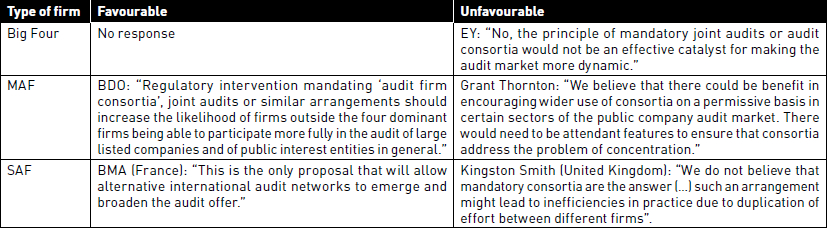

Audit Consortia

The EC proposed creating audit consortia. Tables 4f, 5f and 6f present the results for this theme.

The Big Four were the only type of firm to be broadly opposed to the establishment of audit firm consortia. Their opposition was unanimous, PwC, for example, explaining that “the mandatory formation of an audit firm consortium (...) will not dynamise the market”. To justify their opinion, the Big Four all referred to the additional cost of joint audit, as well as its negative impact on audit quality, “Risks from joint audits include the challenges of coordinating between two audit firms and the costs of duplication.” (EY)

Conversely, MAFs and SAFs were strongly in favour of this policy option (67% and 56%, respectively). Mid-tier HLB International, for example, stated that “Requiring at least one consortia not subject to systematic risk could be a good catalyst for opening up the market.” They supported this policy option, believing that it would mechanically open the PIE market to firms other than the Big Four.

Discussion

Audit Firms’ Positions and Market Structure

Previous studies on the audit market have shown that concentration and segmentation of supply is generally harmful for non-Big N firms (Cabán-García and Cammack, 2009; Steponavičiūtė and Zvirblis, 2011). In this context, regulation may be an effective method of homogenising supply and reducing the market distortion caused by the dominance of the Big N (Hogan and Martin, 2009; Cassell et al., 2013; Bills and Stephens, 2016).

The results of our study show that all audit firms, regardless of their size, took similar positions on the policy options proposed by the EC for five of the six themes selected. More specifically, all three types of audit firm supported policy options designed to regulate individual clients’ financial weight and strengthen supervisory mechanisms. However, it is not clear that this reflects genuine conviction regarding the effectiveness of the proposed measures. The threshold relating to a client’s financial weight mentioned by most respondents refers to the IFAC Code of Ethics, which is already applied quite broadly, in particular with regard to the audit of large companies. Similarly, the policy option on supervisory mechanisms would undoubtedly be the least restrictive measure for all audit firms. In addition, firms were also unanimously opposed to policy options on the appointment of auditors by a third party, the mandatory rotation of audit firms and the creation of pure audit firms. These results indicate that audit firms as a whole consider that these three measures would be unlikely to increase competition between the different sizes of firm and so would fail to genuinely enhance the competitiveness of the European audit market. Finally, the mandatory formation of audit consortia (with at least one non-Big Four) was the only theme where the positions of the three types of firm diverged. The Big Four were unanimously opposed to this proposal, while the two other types of firm were mostly in favour. From the perspective of MAFs and SAFs, this policy option represented the main lever with which to achieve the EC’s objective of dynamising the audit market and increasing access to the market for listed companies.

Table 4d

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of the financial weight of individual clients

The dominant position is in bold. The position of the German SAFs that prepared a joint response is shown in italics.

Table 5d

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of the financial weight of individual clients

Table 6d

Arguments on the theme of the financial weight of individual clients

Beyond the positions of the audit firms, this analysis highlights the limitations, both in terms of quantity and variety, of the arguments formulated by these firms. Few respondents developed genuine arguments, with most of them simply expressing their position without justification. Tables 6a to 6f show the overlap between the arguments on the six themes analysed. The arguments most frequently employed referred to additional costs and to the risk of a reduction in audit quality (because of a lack of skills or knowledge of the audited entity) or to the fact that audit-related decisions must be made by shareholders, the owners of the audited entity. Finally, few respondents provided alternative proposals to the policy options formulated in the Green Paper, despite the collection of alternative arguments and proposals from stakeholders being the main aim of the EC when it launches a public consultation. The alternative arguments and proposals presented do, nonetheless, allow us to identify the issue of the access to, and the development of, the resources necessary to perform an audit as the main explanatory factor behind firms’ positions in relation to the policy options formulated by the EC in its Green Paper.

Table 4e

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of supervisory mechanisms

The dominant position is in bold. The position of the German SAFs that prepared a joint response is shown in italics.

Table 5e

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of supervisory mechanisms

Table 6e

Arguments on the theme of supervisory mechanisms

Access to Resources and Market Structure

Although economic theory helps us to understand the EC’s observations on the structure of the European audit market, an additional interpretive framework is needed to understand the responses of individual audit firms to the Green Paper consultation. We therefore enhance our analysis by identifying the skills required for the audit process from the perspective of the scarce resources on which the various actors depend. The main element to bear in mind is that the market for these skills is not a “complete” market (Danos and Eichenseher, 1982). SAFs and MAFs are typically unable to acquire the skills necessary to undertake the audit of specific clients on an ad hoc basis. Similarly, the costs or the contractual impossibility of subcontracting engagements to other audit firms inevitably leads to scale effects. This factor alone suggests that the costs of developing relevant skills will be comparatively lower for the Big Four, for example. This condition of the indivisibility of audit firms effectively creates a critical mass threshold effect, where audit firms operating below the threshold have higher operational costs than the large audit firms. In this regulated sector, the ability to win market share depends on resources such as staff able to perform both general and specialised audits, or managers who are familiar with the sector and have high-quality marketing skills with which to sell the firm’s brand (Arnett and Danos, 1979). Human capital thus appears to be a decisive asset in audit firms’ development (Pennings et al., 1998; Bröcheler et al., 2004). It is therefore crucial to interpret the dynamics of the audit market from a resource dependence perspective, where resource position barriers exist, similar to barriers to entry (Wernerfelt, 1984).

Table 4f

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of audit consortia

The dominant position is in bold. The position of the German SAFs that prepared a joint response is shown in italics.

Table 5f

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of audit consortia

Table 6f

Arguments on the theme of audit consortia

Unlike neoclassical economic theory, which assumes that the supply of resources and capabilities (the factors of production) is elastic, resource dependence theory can be used to better understand the structure of the audit market by acknowledging the relative inelasticity of these resources (Barney, 2001). This inelasticity may arise from the fact that some resources or capabilities can only be acquired in the long term (the human capital required for the audit of an international group, for example), or from the fact that it is difficult to know how to initiate their acquisition or development in the short or medium term. The inelasticity of human capital and skills resources in the audit market thus leads to a situation in which the firms with the most resources, such as the Big Four, generate above-average profits (overall and per auditor). In addition, in this mature and regulated market (Maijoor and van Witteloostuijn, 1996), these profits do not necessarily increase the supply of resources, but instead generate returns that become a real competitive advantage (Peteraf, 1993), through higher salaries or by developing awareness of the firm’s brand (Ferguson and Stokes, 2002).

The assumption that some audit firms are unable to adapt immediately, and that they try to find an optimal positioning in function of the resources to which they have access, allows us to understand the natural segmentation of this market and the reactions of the different actors to the policy options proposed by the EC. This segmentation relates both to the dominance of the Big Four in the large listed companies segment, and to the smaller audit firms able to avoid competing with the Big Four by exploiting client sizes that are too small to be profitable for the Big Four or by specialising in particular service sectors (Carroll et al., 2002). Each segment thus coexists with the others, with its own ecosystem of available resources, as shown by the example of the development of small Dutch audit firms in the studies of Boone and van Witteloostuijn (1995) and Maijoor and van Witteloostuijn (1996). In light of our results, it is therefore understandable that most audit firms (of all types) were opposed to policy options relating to the appointment of auditors by a third party, the mandatory rotation of audit firms and the creation of pure audit firms. These regulatory obligations could negatively affect the resource/market share balances of audit firms within their business segment without providing them with alternative compensation. In addition, with regard to the appointment of auditors, the overriding argument put forward by the three types of firm on the role of shareholders at their general meeting can be understood as the desire to maintain an intuitu personae auditor-auditee relationship, the management team often being determined by the majority shareholder(s). In addition, the three types of audit firm were broadly in favour of policy options to regulate the financial weight of individual clients and to strengthen supervisory mechanisms, as these options referred to pre-existing national or international mechanisms (such as the IFAC Code of Ethics) and therefore would not fundamentally change the equilibrium in terms of the access to resources within each market segment. These exogenous shocks would therefore be marginal for all three types of firm. Finally, the divergence between the Big Four, on the one hand, and the SAFs and MAFs, on the other, in relation to the policy option of mandatory audit firm consortia also makes sense. With equal resources, this would be a unique opportunity for SAFs and MAFs to gain access to the large listed companies segment at a lower cost and thus increase their market share. Although the Big Four would not really lose market share, this could represent a real cost in terms of the free transfer of skills to SAFs and MAFs. Consortia structures could thus contribute to the creation of potential future rivalries among international MAFs.

Conclusion and New Regulations

This study contributes to the literature on the participation of stakeholders in accounting regulatory processes by examining the case of an international public regulatory body, in this case, the EC. It thus extends and enriches studies on this topic, as most of the existing literature deals with national, and mainly Anglo-Saxon, private accounting standard-setting bodies (Jorissen et al., 2012). In addition, although consultation responses are often used in the literature to analyse stakeholder participation (Georgiou, 2004; Königsgruber, 2010; Orens et al., 2011), the consultation responses prepared for the Green Paper published by the EC in 2010 have, to our knowledge, never been used in an academic study. Finally, the type of stakeholder analysed in this research complements the results of previous studies. Studies on the participation of the profession or of audit firms in regulatory processes only distinguish between Big Four and non-Big Four (Puro, 1984; MacArthur, 1988; Deegan et al., 1990; McKee et al., 1991; Meier et al., 1993). We provide an additional level of analysis by distinguishing between three types of firm (Big Four, MAFs and SAFs).

This research also provides an original view of the dynamics of audit market structure. A resource dependence perspective helps us to understand players’ positions in relation to their business segment and to better understand the underlying drivers of the European audit market.

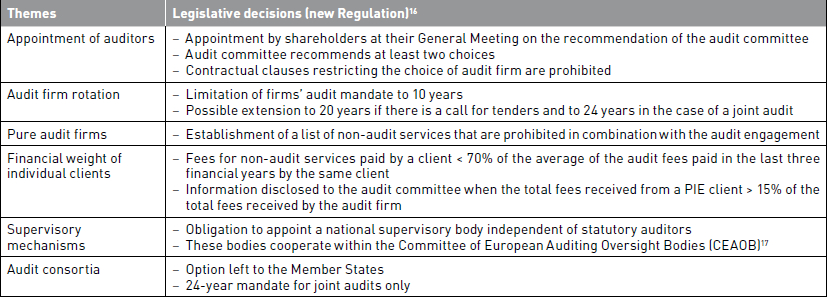

In November 2011, following its Green Paper consultation, and the subsequent conference and study of the audit market (Le Vourc’h and Morand, 2011), the EC published an amended proposal for a Directive and a proposal for a new Regulation, which were discussed in “trilogue” meetings until agreement was reached at the end of 2013. They were adopted by the European Parliament in April 2014. The amended Directive 2014/56/EU (Official Journal of the European Union, 2014a) and the new Regulation 537/2014 (Official Journal of the European Union, 2014b) were published in the Official Journal of the EU on 27 May 2014. Appendix 1 presents the main provisions of these texts in relation to the six themes selected in this study. The reform has been applicable since June 2016. It would be useful to extend this work by analysing the real ex post impacts of this reform on market competitiveness.

Appendices

Appendix

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the reviewers and the editor for the quality of their comments, which helped to improve the article considerably. They are also grateful to Becky Rawlings for her excellent translation work.

Biographical notes

Marie-Claire Loison is an associate professor at emlyon business school and a member of the OCE (Organisations, Careers and New Elites) research centre. Her teaching specialties are financial accounting, management accounting, management control and CSR reporting. She obtained a PhD degree in Management from the Paris Dauphine University after studying at Ecole Normale Supérieure (ENS Cachan). Her main research focuses on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainable development practices. She is also interested in socio-institutional aspects and evolutions of accounting, auditing and management control systems.

Loïc Belize is associate professor of finance at emlyon business school. His main research themes are focused on corporate governance, the fair value of complex assets/liabilities, and also on regulation and lobbying processes within the finance and audit European markets. Loïc teaches corporate finance and the financial engineering of financing instruments.

Géraldine Hottegindre is associate professor at emlyon business school. Her principal research is focused on the role of the statutory auditing profession and lobbying on audit regulators. Géraldine also has an interest in the sociological aspects of the accounting, in gender issues in audit firms. Géraldine teach financial accounting, managerial accounting, and audit.

Notes

-

[1]

In the remainder of the article, we use the term “audit” to refer to statutory audit.

-

[2]

The term “Big Four” refers to the four largest international audit firm networks: Deloitte, EY (formerly Ernst & Young), KPMG and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC).

-

[3]

The term “position” here refers to respondents’ agreement or disagreement with the policy options formulated by the regulator in its public consultation.

-

[4]

The SAFs include independent practitioners.

-

[5]

In Europe, only France and Denmark have lower ratios, with 73% and 78%, respectively, of listed companies being audited by a Big N firm. This is mainly due to the legal requirement for joint audits in those countries.

-

[6]

This section is based on the content of a semi-structured interview, lasting approximately one hour, recorded and transcribed, with an EC policy officer. His role is to lead reforms at EU level - within the EC’s Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union

-

[7]

The Council of the EU brings together all the ministers of the 28 Member States. It represents the general interest of the governments of the Member States. It participates directly in drafting European regulations and directives (in collaboration with the EC and the European Parliament).

-

[8]

The European Parliament is composed of 751 Members from the 28 Member States. It participates directly in developing European regulations and directives (in collaboration with the EC and the Council of the EU). No text can be adopted without the prior consultation of the European Parliament.

-

[9]

If the EC does not consult stakeholders, it runs a significant risk of not being supported by the co-legislators, who will assume that the EC does not know stakeholders’ views or whether they will support the reform.

-

[10]

These respondents correspond to 146 listed companies from different European countries.

-

[11]

Level 3 of the “Lamfalussy process” is a Community mechanism for dealing with market abuse. It helps to harmonise the adoption of regulations and directives at a European level thanks to greater cooperation between regulators in the different Member States. In particular, at level 3, the EC verifies that Member States are in compliance with EU legislation and can take action against any Member State that does not comply with Community law.

-

[12]

In similar research on public consultations launched by the IASB, Giner and Arce (2012) obtain participation rates of 66.9% for preparers and 8.2% for the profession; Jorissen et al. (2012) observe 43% for preparers and 25.2% for the profession; and finally Le Manh (2012) has 42.4% for preparers, 8% for audit firms and 19.2% for professional accounting associations.

-

[13]

Evaluation coding is the analysis of data to assess the merit, worth or significance of programmes or policies (Saldaña, 2016, p. 140).

-

[14]

In their study of banks’ participation in a public consultation organised by the Financial and Accounting Standards Board (FASB) on the fair value measurement of loans, Hodder and Hopkins (2014) exclude 828 observations from their sample, corresponding to banks that each sent several identical responses. Accordingly, only one response per bank is included in the final sample. Similarly, Chatham et al. (2010) treat identical responses from the same respondent as a single response in their work on stakeholder participation in an IASB-initiated consultation on IAS 39, relating to fair value accounting for all financial instruments.

-

[15]

No response provided.

-

[16]

The decisions described in this table refer to the new Regulation insofar as the measures relating to the six themes selected for our analysis are only included in the Regulation. The Directive covers other aspects of the reform.

-

[17]

This committee was created through a transformation of the EGAOB.

Bibliography

- Ang, Nicole; Sidhu, Baljit K; Gallery, Natalie (2000). “The Incentives of Australian Public Companies Lobbying Against Proposed Superannuation Accounting Standards”, Abacus, Vol. 36, N° 1, p. 40-70.

- Arnett, Harold E.; Danos, Paul. (1979). CPA firm viability: A study of major environmental factors affecting firms of various sizes and characteristics, Ann Arbor: Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, University of Michigan.

- Barney, Jay B. (2001). “Resource-Based Theories of competitive Advantage: A Ten-year Retrospective on the Resource-based View”, Journal of Management, Vol. 27, N° 6, p. 643.

- Bills, Kenneth L.; Stephens, Nathaniel M. (2016). “Spatial Competition at the Intersection of the Large and Small Audit Firm Markets”, Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, Vol. 35, N° 1, p. 23-45.

- Boone, Christophe; van Witteloostuijn, Arjen (1995). “Industrial Organization and Organizational Ecology: The Potentials for Cross-fertilization”, Organization Studies (Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG.), Vol. 16, N° 2, p. 265.

- Bröcheler, Vera; Maijoor, Steven; van Witteloostuijn, Arjen (2004). “Auditor Human Capital and Audit Firm Survival: The Dutch Audit Industry in 1930-1992”, Accounting, Organizations & Society, Vol. 29, N° 7, p. 627-646.

- Byington, J. Ralph; Sutton, Steve; Munter, Paul (1990). “A Professional Monopoly’s Response: Internal and External Threats to Self-Regulation”, Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance (Wiley), Vol. 1, N° 4, p. 307-316.

- Cabán-García, María T.; Cammack, Susan E. (2009). “Audit Firm Concentration and Competition: Effect of Consolidation Since 1997”, Journal of Theoretical Accounting Research, Vol. 5, N° 1, p. 1-24.

- Carroll, Glenn R.; Dobrev, Stanislav D.; Swaminathan, Anand (2002). “Organizational Processes of Resource Partitioning”, Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 24, p. 1-40.

- Carson, Elizabeth; Redmayne, Nives Botica; Liao, Lin (2014). “Audit Market Structure and Competition in Australia”, Australian Accounting Review, Vol. 24, N° 4, p. 298-312.

- Cassell, Cory A.; Giroux, Gary; Myers, Linda A.; Omer, Thomas C. (2013). “The Emergence of Second-Tier Auditors in the US: Evidence from Investor Perceptions of Financial Reporting Credibility”, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, Vol. 40, N° 3/4, p. 350-372.

- Chatham, Michael D.; Larson, Robert K.; Vietze, Axel (2010). “Issues Affecting the Development of an International Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments”, Advances in Accounting, Vol. 26, N° 1, p. 97-107.

- Colasse, Bernard; Standish, Peter (1998). “State versus Market: Contending Interests in the Struggle to Control French Accounting Standardisation”, Journal of Management & Governance, Vol. 2, N° 2, p. 107-147.

- Cox, James D. (2006). “The Oligopolistic Gatekeeper: The US Accounting Profession”, In J. Armour and J. A. McCahery (Eds), After Enron: Improving Corporate Law and Modernizing Securities Regulation in Europe and the US, Oxford, Oxford University Press, p. 269-316.

- Danos, Paul; Eichenseher, John W. (1982). “Audit Industry Dynamics: Factors Affecting Changes in Client-Industry Market Shares”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 20, N° 2, p. 604-616.

- Deegan, Craig; Morris, Richard; Stokes, Donald (1990). “Audit Firm Lobbying on Proposed Disclosure Requirements”, Australian Journal of Management (University of New South Wales), Vol. 15, N° 2, p. 261.

- Eshleman, John Daniel; Lawson, Bradley P. (2017). “Audit Market Structure and Audit Pricing”, Accounting Horizons, Vol. 31, N° 1, p. 57-81.

- European Commission. (2010). Green Paper. Audit Policy: Lessons from the Crisis.

- Ferguson, Andrew; Stokes, Donald (2002). “Brand Name Audit Pricing, Industry Specialization, and Leadership Premiums Post-Big 8 and Big 6 Mergers”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 19, N° 1, p. 77-110.

- Georgiou, George (2004). “Corporate Lobbying on Accounting Standards: Methods, Timing and Perceived Effectiveness”, Abacus, Vol. 40, N° 2, p. 219-237.

- Ghosh, Aloke; Lustgarten, Steven (2006). “Pricing of Initial Audit Engagements by Large and Small Audit Firms”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 23, N° 2, p. 333-368.

- Giner, Begoña; Arce, Miguel (2012). “Lobbying on Accounting Standards: Evidence from IFRS 2 on Share-Based Payments”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 21, N° 4, p. 655-691.

- Hodder, Leslie D.; Hopkins, Patrick E. (2014). “Agency Problems, Accounting Slack, and Banks’ Response to Proposed Reporting of Loan Fair Values”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 39, N° 2, p. 117-133.

- Hoffmann, Sebastian; Zülch, Henning (2014). “Lobbying on Accounting Standard Setting in the Parliamentary Environment of Germany”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 25, N° 8, p. 709-723.

- Hogan, Chris E.; Martin, Roger D. (2009). “Risk Shifts in the Market for Audits: An Examination of Changes in Risk for “Second Tier” Audit Firms”, Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, Vol. 28, N° 2, p. 93-118.

- Huber, Dennis (2015). “The Structure of the Public Accounting Industry. Why Existing Market Models Fail”, Journal of Theoretical Accounting Research, Vol. 10, N° 2, p. 43-67.

- IFAC. (2009). Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, IFAC.

- Ivaldi, Marc; Jullien, Bruno; Rey, Patrick; Seabright, Paul; Tirole, Jean. (2003). The Economics of Tacit Collusion. Final Report for DG Competition, European Commission.

- Jorissen, A.; Lybaert, N.; Orens, R.; Van Der Tas, L. (2012). “Formal Participation in the IASB’s Due Process of Standard Setting: A Multi-Issue/Multi-Period Analysis”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 21, N° 4, p. 693-729.

- Königsgruber, Roland (2010). “A Political Economy of Accounting Standard Setting”, Journal of management and governance, Vol. 14, N° 4, p. 277-295.

- Le Manh, Anne (2012). “Une analyse du due process dans le cadre de la normalisation comptable: le cas du projet de comprehensive income par l’IASB/International Accounting Standardization Analyzed in Terms of a Political Process: The Specific Case of Petroleum Resources”, Comptabilité Contrôle Audit, Vol. 18, N° 1, p. 93-120.

- Le Vourc’h, J.; Morand, P. (2011). Study on the Effects of the Implementation of the “Acquis” on Statutory Audits of Annual and Consolidates Accounts Including the Consequences on the Audit Market, ESCP Europe.

- Levenstein, Margaret C.; Suslow, Valerie Y. (2006). “What Determines Cartel Success?”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 44, N° 1, p. 43-95.

- London Economics; Ewert, Ralf. (2006). Study on the Economic Impact of Auditors’ Liability Regimes (MARKT/2005/24/F). Final Report to EC-DG Internal Market and Services, European Commission.

- MacArthur, John B. (1988). “Some Implications of Auditor and Client Lobbying Activities: A Comparative Analysis”, Accounting & Business Research (Wolters Kluwer UK), Vol. 19, N° 73, p. 56-64.

- Maijoor, Steven; van Witteloostuijn, Arjen (1996). “An Empirical Test of the Resources-Based Theory: Strategic Regulation in the Dutch Audit Industry”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, N° 7, p. 549-569.

- McKee, A. James; Williams, Paul F.; Frazier, Katherine Beal (1991). “A Case Study of Accounting Firm Lobbying: Advice or Consent”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 2, N° 3, p. 273-294.

- McLeay, Stuart; Ordelheide, Dieter; Young, Steven (2000). “Constituent Lobbying and its Impact on the Development of Financial Reporting Regulations: Evidence From Germany”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 25, N° 1, p. 79-98.

- Meier, Heidi Hylton; Alam, Pervaiz; Pearson, Michael A. (1993). “Auditor Lobbying for Accounting Standards: The Case of Banks and Savings and Loan Associations”, Accounting & Business Research (Wolters Kluwer UK), Vol. 23, N° 92, p. 477-487.

- Moizer, Peter (1992). “State of the Art in Audit Market Research”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 1, N° 2, p. 333-348.

- Niemi, Lasse (2004). “Auditor Size and Audit Pricing: Evidence from Small Audit Firms”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 13, N° 3, p. 541-560.

- Official Journal of the European Union. (2006). Directive 2006/43/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2006 on statutory audits of annual accounts and consolidated accounts, amending Council Directives 78/660/EEC and 83/349/EEC and repealing Council Directive 84/253/EEC.

- Official Journal of the European Union. (2014a). Directive 2014/56/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 amending Directive 2006/43/EC on statutory audits of annual accounts and consolidated accounts.

- Official Journal of the European Union. (2014b). Regulation (EU) No 537/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on specific requirements regarding statutory audit of public-interest entities and repealing Commission Decision 2005/909/EC.

- Orens, Raf; Jorissen, Ann; Lybaert, Nadine; Van Der Tas, Leo (2011). “Corporate Lobbying in Private Accounting Standard Setting: Does the IASB Have to Reckon with National Differences?”, Accounting in Europe, Vol. 8, N° 2, p. 211-234.

- Pennings, Johannes M.; Lee, Kyungmook; Van Witteloostuijn, Arjen (1998). “Human Capital, Social Capital, and Firm Dissolution”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41, N° 4, p. 425-440.

- Peteraf, Margaret A. (1993). “The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 14, N° 3, p. 179-191.

- Puro, Marsha (1984). “Audit Firm Lobbying Before the Financial Accounting Standards Board: An Empirical Study”, Journal of Accounting Research, p. 624-646.

- Saldaña, Johnny. (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Simons, Dirk; Zein, Nicole (2016). “Audit Market Segmentation – The Impact of Mid-tier Firms on Competition”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 25, N° 1, p. 131-154.

- Standish, Peter (2003). “Evaluating National Capacity for Direct Participation in International Accounting Harmonization: France as a Test Case”, Abacus, Vol. 39, N° 2, p. 186-210.

- Steponavičiūtė, Jūratė; Zvirblis, Algis (2011). “Main Principles of the Complex Assessment of Audit Market Concentration and Audit Services Quality Levels”, Issues of Business & Law, Vol. 3, p. 20-33.

- Wang, Kun; O, Sewon; Iqbal, Zahid; Smith, L. Murphy (2011). “Auditor Market Share and Industry Specialization of Non-Big 4 Firms”, Journal of Accounting & Finance (2158-3625), Vol. 11, N° 2, p. 107-127.

- Wernerfelt, Birger (1984). “A Resource-Based View of the Firm”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 5, N° 2, p. 171-180.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Marie-Claire Loison est professeur associé à emlyon business school et membre du centre de recherche OCE (Organisation, Carrières et Nouvelles Élites). Agrégée d’économie-gestion et ancienne élève de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure (ENS Cachan), elle est titulaire d’un doctorat en sciences de gestion de l’Université Paris Dauphine. Elle enseigne la comptabilité financière, la comptabilité de gestion, le contrôle de gestion ainsi que le reporting RSE. Ses recherches portent principalement sur les pratiques de responsabilité sociétale de l’entreprise (RSE) et de développement durable. Elle s’intéresse également aux aspects socio-institutionnels et aux évolutions des systèmes comptables, d’audit et de contrôle.

Loïc Belze est professeur associé de Finance à emlyon business school. Ses principaux thèmes de recherche portent sur la gouvernance d’entreprise, sur l’évaluation des actifs/passifs complexes en fair value, ainsi que sur les aspects de régulation et de lobbying du marché de la finance et de l’audit dans le cadre européen. Loïc enseigne la finance d’entreprise et l’ingénierie financière des instruments de financement.

Géraldine Hottegindre est professeur associé à emlyon business school. Ses principales recherches portent sur le rôle de la profession de commissaire aux comptes et sur les actions de lobbying exercées par diverses parties prenantes sur le régulateur comptable. Elle s’intéresse aussi aux aspects sociologiques de l’audit et aux problématiques de genre dans les cabinets d’audit. Géraldine enseigne la comptabilité financière, la comptabilité managériale, l’audit et la finance d’entreprise.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Marie-Claire Loison es profesora asociada en emlyon business school y miembro del centro de investigación OCE (Organización, Carreras y Nuevas Élites). Antigua alumna de la Escuela Normal Superior (ENS Cachan), es titular de un doctorado en Ciencias Administrativas y Gestión en la Universidad de París Dauphine. Enseña la contabilidad financiera, la contabilidad de gestión, el control de gestión como también el reporting de la responsabilidad social corporativa (RSC). Sus investigaciones se refieren principalmente a la práctica de la RSC y al desarrollo sostenible. Igualmente, se interesa a los aspectos socio-institucionales y a las evoluciones de sistema contables, de auditoría y de control.

Loïc Belze es profesor asociado de finanzas en emlyon business school. Sus principales temas de investigación se refieren al gobierno corporativo, al valor de mercado de activos / pasivos complejos, y también a los procesos de presión políticas dentro de los mercados de finanzas y de auditoría. Loïc enseña la finanza corporativa, y la ingeniería financiera de instrumentos financieros.

Géraldine Hottegindre es profesora asociada en emlyon business school. Sus principales investigaciones se refieren al rol de la profesión de auditor y sobre las acciones de presión ejercidas por diversos grupos para influir sobre reguladores contables. Se interna también a los aspectos sociológicos de la auditoría y a los problemas de género en las firmas de auditoría. Enseña la contabilidad financiera, la contabilidad de gestión and auditoría.

List of tables

Table 1

Questions and policy options formulated by the EC on the six themes

Table 2a

Example of coding of a Big Four response (Deloitte) on the theme of pure audit firms

Table 2b

Illustration of the “neutral” position for each of the six themes

Table 3

Distribution of audit firm responses by geographical origin of respondent and by type of firm

Table 4a

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of the appointment of auditors[15]

Table 5a

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of the appointment of auditors

Table 6a

Arguments on the theme of the appointment of auditors

Table 4b

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of the audit firm rotation

Table 5b

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of the audit firm rotation

Table 6b

Arguments on the theme of the audit firm rotation

Table 4c

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of pure audit firms

Table 5c

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of pure audit firms

Table 6c

Arguments on the theme of pure audit firms

Table 4d

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of the financial weight of individual clients

Table 5d

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of the financial weight of individual clients

Table 6d

Arguments on the theme of the financial weight of individual clients

Table 4e

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of supervisory mechanisms

Table 5e

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of supervisory mechanisms

Table 6e

Arguments on the theme of supervisory mechanisms

Table 4f

Number of responses and valid percentage on the theme of audit consortia

Table 5f

Illustration of “favourable” and “unfavourable” positions on the theme of audit consortia

Table 6f

Arguments on the theme of audit consortia