Abstracts

Summary

The global COVID-19 pandemic acted as an exogenous shock that forced organizations to adopt homeworking as a common form of work for many occupations. By that time researchers had been stressing the gap between technical feasibility of homeworking – reaching on average one third of employment in both the US and EU28 (Dingel and Neiman 2020, Sostero et al. 2020) – and its practical adoption in organisations. The massive shift to homeworking during the pandemic – especially in countries such as France and Italy, which both experienced a widespread lockdown during the first wave – has been an opportunity to study homeworking across a large and heterogeneous cross-section of occupations and sectors. To that end, the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission (in Seville) funded real-time cross-occupational qualitative research on which this paper is based.

First, drawing on studies that attribute the delayed spread of homeworking to the dialectic between workers' self-latitude and managerial control, we examined how compulsory homeworking affected workers’ self-latitude to define and perform their tasks. We identified two different phases and temporary arrangements of the worker self-latitude/managerial control dialectic during the time under study. Second, we analyzed how different forms of control developed under the new organization of work. Specifically, we studied how the outcomes varied by occupation and along the vertical division of labour. Our results suggest an ongoing hybridization of personal, technical and bureaucratic forms of control. Accordingly, we agree with labour process theorists who argue that personal, bureaucratic and technical forms of control complement each other, rather than being stages of a linear and functionalist succession.

Abstract

The global COVID-19 pandemic acted as an exogenous shock that forced organizations to adopt homeworking as a common form of work for many occupations. Drawing on a real-time cross-occupational qualitative survey, we first examined how compulsory homeworking affected workers’ freedom to define and perform their tasks. Second, we analyzed how different forms of control developed under the new organization of work. Specifically, we studied how the outcomes varied by occupation and along the vertical division of labour. Our findings agree with those of labour process theorists who argue that personal, bureaucratic and technical forms of control complement each other, rather than being stages of a linear succession.

JEL classification: L23, M54, 033, J81.

Keywords:

- homeworking,

- work organization,

- labour process,

- autonomy,

- control

Résumé

La pandémie mondiale de COVID-19 a agi comme un choc exogène qui a forcé les organisations à adopter le télétravail comme une forme de travail courante pour de nombreuses professions. À cette date, des chercheurs avaient souligné l'écart entre la faisabilité technique du télétravail – atteignant en moyenne un tiers des emplois aux États-Unis et dans l'UE28 (Dingel et Neiman 2020, Sostero et al. 2020) – et son adoption pratique dans les organisations. Le passage massif au télétravail pendant la pandémie – en particulier dans des pays comme la France et l'Italie, qui ont tous deux connu un confinement généralisé pendant la première vague – a été l'occasion d'étudier le télétravail dans un éventail large et hétérogène de professions et de secteurs. À cette fin, le Joint Research Centre de la Commission européenne (basé à Séville) a financé une recherche qualitative inter-professionnelle en temps réel sur laquelle se base cet article.

Tout d'abord, en nous appuyant sur des études qui attribuent la diffusion tardive du télétravail à la dialectique entre la latitude personnelle des travailleurs et le contrôle managérial, nous examinons comment le télétravail mandaté a affecté la latitude personnelle des travailleurs à définir et à exécuter leurs tâches. Nous identifions deux phases et arrangements temporaires différents de la dialectique entre la latitude personnelle des travailleurs et le contrôle managérial au cours de la période étudiée. Deuxièmement, nous analysons comment différentes formes de contrôle se sont développées dans le cadre de la nouvelle organisation du travail. Plus précisément, nous étudions comment ces développements varient en fonction de la profession et de la division verticale du travail. Nos résultats suggèrent une hybridation continue des formes de contrôle personnelles, techniques et bureaucratiques. Par conséquent, nous rejoignons les théoriciens du processus de travail qui soutiennent que les formes de contrôle personnel, bureaucratique et technique se complémentent mutuellement, plutôt que d'être des stades d'une succession linéaire et fonctionnaliste.

Article body

1. Introduction

Debate about the future of work in relation to teleworking dates back to the 1970s and the first efforts to introduce ICTs into organizations. ICTs made it possible to organize new forms of work outside the workplace. With the expansion of occupations that involved creating, transforming and disseminating information rather than physical materials, telework became feasible across a broad spectrum of occupations (see Illegems et al., 2001; Taskim and Edwards, 2007; Bloom et al., 2015). The COVID-19 global pandemic and the (forced) massive shift toward homeworking have led to a renewed need for research on how this type of work arrangement is distributed by occupation. To stress the exceptionality of this massive shift, we prefer to use the term ‘homeworking’ in this article, instead of ‘teleworking.’ To be consistent with the literature, the term ‘telework’ will be used in Sections 2 and 3 (literature review and methodology). For the same reason, we will use the concept of ‘teleworkability’ (see Section 3 for its definition). Dingel and Neiman (2020), using O*NET data on work content and ICT requirement and use, find that, from a purely technical point of view, 37% of American occupations are teleworkable. According to Sostero et al. (2020), one in three employees in the EU28 could perform their tasks outside their firm’s workplace. This proportion is confirmed by Cetrulo et al. (2020a) for Italy and increases to 56% for Germany (Alipour and Falck, 2020). However technical feasibility is not enough. Sostero et al. (2020) show that in 2019 only 11% of employees in the EU28 were working from home at least some of the time.

We need to look beyond technical feasibility to examine institutional factors. At the macro level, countries vary in the technical feasibility of telework because of differences in employment structure, sectoral specialization and actual ICT infrastructure (Messenger, 2019). Nevertheless, such factors cannot entirely explain the discrepancy between the theory of remote work and its actual implementation.

Starting from the hypothesis that the dialectic between worker control and managerial control is crucial for the spread of telework (Clear and Dickson, 2005; Felstead et al., 2003; Olson, 1988), the aim of our article is twofold. First, we want to illustrate how compulsory homeworking has affected workers’ freedom to define and undertake their tasks and how this outcome varies with occupational structure. Second, looking at the different outcomes, we wish to analyze how different forms of control (personal, bureaucratic and technical) have developed under this new organization of work. In doing so, we will draw on cross-occupational qualitative interviews[3] from France and Italy during the first nation-wide lockdown between March and May 2020.[4]

The rest of our article will be structured as follows. Section 2 will summarize the relevant literature on telework and the forms of control applied to telework. Section 3 will present the methodology. Section 4 will have three subsections: the transition to homeworking and its immediate impact on the organization of work (4.1); the emergence of remote personal control (4.2); and its hybridization with bureaucratic control (4.3). Finally, Section 5 will provide a discussion of the evidence and a conclusion.

2. Literature Review and Motivation

One of the main contributions of labour process theory has been to focus analysis on the issue of control over labour processes (Thompson and Smith, 2010; Vidal 2022). According to Braverman (1974), managerial control was asserted during the 20th century through the implementation of scientific management, particularly the use of technology to automate and mechanize and the principles of Taylorism, especially the division of labour and the separation of conception and execution. Later, that view was partly corrected by writers who showed that the managerial strategies for control of the workforce partially diverged from the Taylorist principles of direct supervision and minimization of workers' responsibility (such as the strategy of ‘responsible autonomy’ outlined by Friedman, 1977). Other writers described the role of employees' resistance in the historical evolution of various forms of control, calling the latter a “contested terrain” (Edwards, 1979). Most recently, some writers have analyzed how the rhetoric of empowerment has helped workers adhere to corporate culture (Willmott, 1993) and encouraged the emergence of forms of peer scrutiny (Sewell and Wilkinson, 1992). Others argue that the ICT revolution has the potential to create a “perfect supervisory power” (Fernie and Metcalf, 1997). Some, on the contrary, have questioned the qualitative nature of these transformations, stressing the coexistence of “old” Tayloristic forms of control (direct supervision, standardization of procedures and technical monitoring) with normative or cultural forms of control (Callaghan and Thompson, 2001; Cooke, 2006).

The telework debate raises similar issues. In recent decades, two main views have emerged about the effects of telework on control and authority mechanisms. According to one view, telework brings more democratic control procedures, mostly based on reciprocal trust and self-control (Zuboff, 1988; for a survey of this stream of literature see Vallas, 1999). Conversely, and more in line with the neo-Taylorist argument, the transition to telework goes hand in hand with an increase in digital-mediated forms of managerial control, such as phone calls, virtual meetings and frequent activity reports (Olson, 1988). Advances in digital-enabled mechanisms of control appear to increase the possibilities for systematic control in telework and in other organizational configurations, such as digital platforms, call centres, and the health care sector (Moore, Upchurch and Wittaker, 2018).

Although the spread of telework has been aided by technological advances, it has been hindered by other factors, particularly the need for direct supervision (Clear and Dickson, 2005; Dimitrova, 2003; Felstead et al., 2003; Olson, 1988). Felstead et al. (2003) document a consensus among managers that workers are disciplined by physical proximity and the resulting surveillance by others (not only supervisors but also co-workers). In France, the spread of telework has been largely hindered by a concurrent resistance to giving employees more autonomy, according to Aguilera et al. (2016). Employees themselves may have mixed feelings because they can no longer show their presence and productivity. They may thus adopt a signalling strategy, such as sending more messages to colleagues and supervisors to make themselves more visible (Taskin and Edwards, 2007; Sewell and Taskin, 2015). For example, according to Mazmanian et al. (2014), knowledge workers end up limiting their autonomy outside the workplace by increasing their use of mobile email devices and by connecting “everywhere/all the time” to show their commitment and productivity. Similar findings are reported by Felstead and Henseke (2017) who, using Labour Force Survey data, show that remote workers “pay” for the right to telework by putting in extra effort and doing unpaid work. This finding is in line with the “social exchange theory” of Kelliher and Anderson (2010).

Feldstead et al. (2003) investigated the extent to which new technological devices have been introduced to replicate visibility and personal control, this being the case mostly with more technologically sophisticated organizations, such as telecommunication companies. More traditional communication devices, such as the telephone, seem inadequate because they result in time-consuming activities or are not sufficiently suited to tracking of worker productivity (Kurkland and Bailey, 1999). For this reason, they are not always appreciated by managers. According to Taskin and Edwards (2007), telework facilitates supervision and managerial control over workers by superimposing new practices onto older, more traditional ones. Managerial control is reinforced by performance management techniques that foster performance-based work and individualization. Telework often brings new forms of control, since daily organizational practices have to be changed so that managers can maintain personal control over teleworkers (Kurkland and Bailey, 1999). Interestingly, once such forms of control have been introduced for remote working, they may be applied even to the firm’s workplace.

Sewell and Taskin (2015) show how the perception of worker control—that is, autonomy and discretion (Maggi, 2016)—deteriorates when managers introduce formalized meetings to check up on what has been done and by whom. On this point, Sewell and Taskin also show that new forms of control add to, or replace, existing ones, thus strengthening and expanding hierarchical supervision. In particular, changes in types of managerial control differently affect clerks and professionals, with the former being subject to more stringent supervision and even to intensification of work (Olson and Primps, 1984). In line with the findings of Dimitrova (2003), control practices are similar for both traditional and remote work by professionals and high-level clerks but are intensified for telework by sales workers. As expected, the more intense forms are characterized more often by interpersonal interactions and formally encoded procedures.

This article will contribute to the literature on the relationships between homeworking, the degree of control over work enjoyed by homeworkers and the forms of control they experience. With respect to the degree of control over their work, we will subdivide the broad category of worker control (Fernandez-Macias and Bisello, 2022) by distinguishing between autonomy and discretion. Autonomy is the ability to produce one’s own rules and therefore modify one’s own actions. Discretion is the ability to choose among a predefined set of actions in a regulated process (Maggi, 2016).

With respect to the forms of control, we will describe personal (or direct) control in terms of “a dyadic relationship between supervisors and subordinates, having its usual expression in direct supervision where one individual assumes authority over the actions of others and closely monitors that action to ensure compliance with orders” (Orlikowsky, 1991, p. 11). This is in contrast to bureaucratic control (or standardization), which is indirect command over the workforce imposed by means of procedural standards or routines. We thus define bureaucratic control as the formalization of working activities in codified sets of procedures and goals (Edwards, 1979; 1984).

While these concepts have been widely used in labour process research to analyze different forms of work organization, including remote work, less has been said about how they interact with each other under remote work regimes. We aim to fill this gap by detailing each form of control in a specific socio-organizational context; that is, homeworking due to confinement during the first wave of COVID-19.

In particular, we will argue that both direct control and bureaucratic control, in a context of physical separation between the firm’s premises and the location where tasks are performed, as in the case of homeworking, must rely on technological means to be effectively implemented. Those technological means, as they become embedded in the technical infrastructure of the production process, impose limits and constraints on workers. In this sense, in our analytical framework, what the literature defines as “technical control,” rather than being an additional dimension, represents a transversal feature of the forms of control analyzed, since both—personal control and bureaucratic control—must be enforced through more or less advanced technological mechanisms (see Thompson 1983). In their 'remote' form, as we will show, both personal control and bureaucratic control can complement technical control to a high degree (Littler and Salaman 1982; Callaghan and Thompson 2001; Sturdy et al. 2010). Personal control, in particular, emerges as a crucial tenet of managerial power across a wide variety of organizational contexts. The sudden impracticability of this form of control forced management to replace it with a remote form that used technological devices with increasing standardization and bureaucratic control.

3. Methodology

The data come from 50 in-depth interviews conducted over April and May 2020—25 in France and 25 in Italy—with dependent employees who were working from home because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We selected them on the basis of a number of criteria provided by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, Seville, and sought to obtain a balanced population in terms of gender, family situation (balance between those interviewees who were in a household with children or dependent persons and those who were not), nature of the employer (no more than 30% of the interviewees in the public sector), occupational level (balance between interviewees with a high and medium/low occupational level), type of work (balance between those interviewees who were in direct contact with the public and those who were not), contractual arrangement (a proportion of around 30% of interviewees having a temporary employment contract) and previous teleworking experience (at least 20% of the interviewees having previous teleworking experience). We excluded employees from the sample if they had been in a permanent telework arrangement before the COVID-19 crisis.

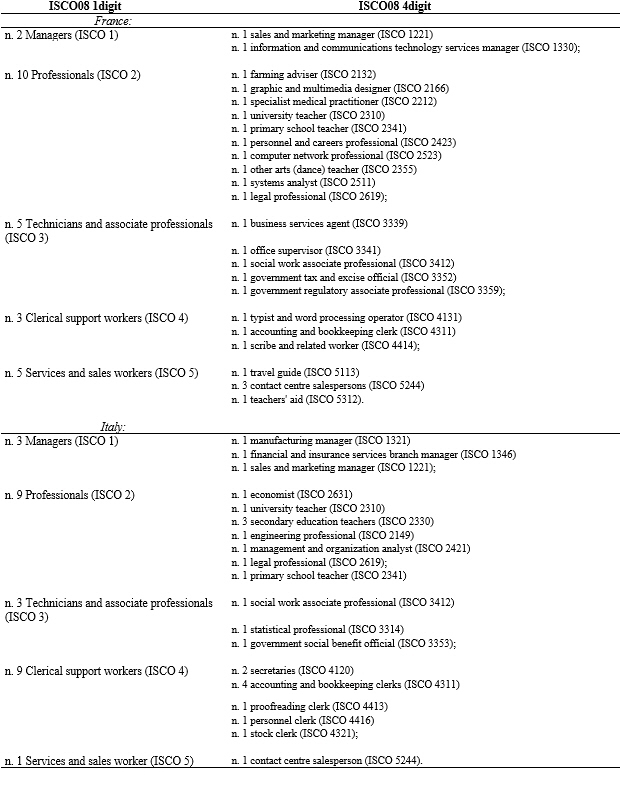

The final composition of the interviewee population reflected the selection criteria. In the case of France, we needed a margin of flexibility in terms of gender and type of work to be able to select an equivalent number of interviewees. Interviewee selection for occupational level required further consideration. Because the chances of implementing telework decrease as one descends the occupational structure (Sostero et al., 2020; Cetrulo et al., 2020a), we selected interviewees belonging only to the first five major groups of the ISCO classification (managers, professionals, technicians and associate professionals, clerical support workers and services and sales workers). The occupational composition of our sample in France and Italy according to the ISCO-08 classification is reported in Table 1, with a degree of detail that reaches the unit group labels (4-digit level).

Table 1

Distribution of Interviewees by Occupation at ISCO-08 One- and Four-Digit Level

With respect to these occupations, we decided to consider those belonging to the first two major groups as having a “high” occupational level and those belonging to the third, fourth and fifth major groups as having a “medium” or “low” occupational level. Beyond having a fairly wide range of occupations, the interviewees also worked in different economic sectors. However, we did not examine sectoral heterogeneity because the low number of our observations would have introduced too much noise.

Table 2 shows the final composition of the sample by country.

Table 2

Distribution of Interviewees by Selection Criteria

The interviewees were recruited through multiple channels (personal contacts, snowball method, social networks, and contacts from previous fieldwork). The interviews were conducted remotely through video conferencing tools, such as Skype, WhatsApp or Zoom or by phone if the Internet connection was insufficient or if requested by the interviewee. The interviews lasted from 48 minutes to 2 hours and 37 minutes, with an average of about 1 hour and 30 minutes.

A semi-structured set of questions was first prepared in English and then translated by the fieldwork researchers into the native languages of the interviewees. Then the interview grid was adapted to the specific situation of the interviewees, who were free to set their own priorities when speaking. The interviews covered the following topics, among others: timing and management of the transition to homeworking; how homeworking affected working routines; how tasks were readjusted after the transition; impact of homeworking on relations with supervisors, co-workers and customers/users; impacts of the transition to homeworking on workers’ autonomy; control mechanisms and teamwork coordination; and implementation of new procedural standards for homeworking.[5]

All the interviews were recorded and transcribed. The resulting textual corpus was dissected according to a 2-layer coding system, based on the interview grid. In line with a qualitative approach, the collected material was systematized through a recursive process of continuous “slippage” between fieldwork, analysis of the material, emerging interpretations and literature on the subject (Alvesson and Kärremann, 2011). Analysis revealed the importance of three dimensions: first, the degree of teleworkability of the tasks (i.e., the possibility of executing tasks remotely); second, the interviewees’ position in the organizational hierarchy and the degree of autonomy they enjoyed prior to the shift to homeworking, which was strongly correlated with their hierarchical level[6]; and third (and subsidiary to the first two), the size of their organization. In the following section, these dimensions will be used to understand how the transition to homeworking affected the dynamics of autonomy and control.

4. Results

4.1. Organizational Shock and Impacts on Control

From the interviews, there emerged two distinct phases of worker control. The first phase coincided with the early period of the transition. Disruption due to the massive switch to homeworking caused a large, wide-ranging increase in autonomy. In some cases, the unexpected increase in autonomy was accompanied by a feeling of being abandoned by management. The second phase started when new work practices were consolidated: managerial control was to some extent restored and, in general, worker autonomy was restrained or gave way to discretion.

Occupations with a low degree of teleworkability, i.e., relying on direct contact with customers and users, were those whose tasks were affected the most by the transition from direct to remote communication. Given their low degree of teleworkability, the sudden shift to homeworking disrupted the work routine, and new work protocols had to be put in place, though not immediately. The greater autonomy was caused mainly by the lack of precise guidelines from employers or managers and manifested itself in a greater possibility to choose or modify the methods of work and the technical tools to support it, as in the case of teachers or social workers.

In contrast, the shift to homework had only a slight impact on highly teleworkable occupations. In such occupations, whether in higher or lower positions in the organizational hierarchy, employees were already accustomed to remote work (in our sample, call centre operators or IT managers). Consequently, as reported by the interviewees, their work methods (and worker control) were not particularly affected:

“My work at this stage is roughly the same. [...] I feel autonomous in the same way, also because, luckily, we already did smart work before. I already felt autonomous before the confinement... just like now, nothing has changed.”

[Italy, data analyst in a bank (ISCO 3314)]

“I monitor the work of my team as I did before. It makes absolutely no difference to me. Out of 100 people, I only had one person who was at the headquarters, so they are supervised with monitoring tools. They have missions, and I will realize very quickly if the work is not done, so there is no risk.”

[France, ICT manager in a telemarketing multinational company (ISCO 1330)]

The degree of teleworkability was not the only factor that affected the impact of homeworking on worker control. The impact also varied according to the worker’s position in the organization. Even when the shift to homework did not formally upset work methods, the withering away of personal control indirectly altered the way tasks were performed, especially for workers in lower positions. For instance, a call centre employee reported that greater autonomy resulted from being able to withdraw from the social control exercised by her colleagues at the workplace, and she felt able to spend more time on the phone with customers while working from home:

“My colleagues criticize my way of working because I lose too much time on the phone with customers while they tend to hurry up and make as many contracts as possible. Me, on the other hand, I have a different way of working and in this context of telework if I want to stay a little more on the phone with a customer, explaining something or solving a problem, I can do it.”

[Italy, call centre operator in a telemarketing company (ISCO 5244)]

On the other hand, workers had to adapt their working procedures to the new situation, thus increasing the need for horizontal coordination. Especially in the case of low teleworkable occupations, at least during the initial phase, the emergency situation allowed some workers to gain decision-making power over the definition of priorities, sometimes to the point of temporarily appropriating the prerogatives usually assigned to management. In many cases, however, the increase in autonomy met an organizational need rather than the workers’ desire for autonomy because managers could not respond to the new situation in a timely manner. In some cases, the result was frustration among workers:

“I've had no communication from anyone; no one told me anything. After a couple of weeks, my supervisor sent us a group message to ask who was available to telework. But I had no instructions about anything. I had quite virulent discussions with management because they sent me to do things I didn't have any kind of information about.”

[France, teacher’s aide in a public high school (ISCO 5312)]

Greater autonomy was not only enjoyed by workers individually but also, in some cases, manifested in the form of collective self-organization and horizontal cooperation in response to management's shortcomings:

“I had to basically set up the changeover to this teleworking regime, with contradictory orders that I've been used to since I worked in the hospital, which were to protect the caregivers from possible contamination. [...] We did this quite independently. We imagined it among ourselves. And then we had meetings of all the doctors in my department with my department head, who is in contact with the other department heads. So we did a bottom-up and top-down process.”

[France, psychiatrist and manager of a psychiatric service in a public hospital (ISCO 2212)]

4.2. From Personal to Remote Control

After an earlier phase of uncertainty, managers tried to restore forms of control and compensate for the absence of direct supervision. Restoration was carried out through two main channels (even if, in practice, it is not always possible to completely disentangle one from each other). The first channel was remote personal control (often exercised through software, communication platforms or other digital tools); the second channel was proceduralization of homeworking, discussed below. Restoration of control via direct supervision depended—in a way not entirely linear—on the worker’s previous degree of autonomy, which was associated with the worker’s position in the occupational hierarchy. The occupational hierarchy and prerogatives determined to a large extent the level of remote personal control that the supervisors exercised under the new regime. If the workers already enjoyed a high degree of autonomy (managers, professionals, teachers, researchers), they could more often protect themselves from remote control and exercise their autonomy and discretion (although, excluding managers, they faced some pressure from their supervisors):

“No one has posed a question of control over online educational activity. Anyway, there is normally no control over lecturers' pedagogical planning: everyone can carry out the program he/she wants. I also think there are those who, perhaps rightly so, have chosen not to do anything anymore, if they already had the students' grades, given the circumstances.”

[France, lecturer in a public university (ISCO 2310)]

“We already had a high degree of autonomy. We were already very autonomous, but with the lockdown, [managers] not [capable of] physically seeing [us], it was even more so.”

[France, illustrator for a children's literature publishing house (ISCO 2166)]

There were some exceptions. In fact, in some large organizations where homeworking had already been implemented, albeit on a smaller scale and as an individual ”benefit” for more professionalized workers, there was already a technological infrastructure in place that could be used to extend remote control to the entire workforce during the pandemic. As a consequence, some professionals in higher positions of the organization gained more personal control due to activation of the intrinsic technological properties of corporate virtual networks (such as VPNs). The networks were activated on a mass scale during the pandemic for homeworking and embedded in the technical infrastructure of the production process. By allowing remote connection, they could also be used for technical control. Because workers perceived them as opaque tools, the result was an increase in self-regulation: the sheer possibility of being controlled led to forms of worker self-control. At least for one interviewee, another result was a feeling of distrust between the employer and the worker:

“We understood that they can track us if they want, if they see that you are not online. For example, one person was told by HR that they would not pay him for the full day because he was only connected for 5 hours. In theory we have no control tools, but from what I understand, HR can see how many hours we have been connected to the PC, through the VPN. [...]”

[Italy, service designer in an automotive firm (ISCO 2421)]

In contrast, there was an increase—quite substantial in some cases—in personal control over workers in middle or low positions (clerical or service workers, such as accounting clerks or call centre operators), who were already under particularly intense forms of supervision. In large organizations, this process very often took the form of recording and listening to worker activity through software and platforms. The use of these tools for disciplinary purposes seems also to have contributed to greater integration between direct supervision and bureaucratic control exercised through rules and procedures (green light on Skype when an employee was working, and yellow light when he or she was on a break, etc.):

“Our managers were already following us remotely through the computer: if there were things to do, they could see it and if you hadn't done them, they could see it too. [...] When we log in, it's like punching in, but other than that there is no great control.”

[Italy, accounting clerk in a public administration (ISCO 4311)]

“We are monitored very often, at least twice a day... Normally we are listened to twice a month, that was different, and we had two verification emails per month…”

[France, call centre operator in a telemarketing company (ISCO 5244)]

If the workers were in middle or low hierarchical positions but employed in small organizations and used to working in close contact with their supervisors (such as secretaries or personal assistants), they reported an increase in personal control that was often exercised via personal communication tools (i.e., phone calls, WhatsApp messages):

“During the lockdown, with my manager we exchanged audio messages on WhatsApp or phone calls, in a large amount during the day. Usually we call each other at 9 a.m., then several times during the day and then at 6 p.m. when we have finished working to take stock of the situation.”

[Italy, assistant to a financial advisor (ISCO 4120)]

4.3. Standardization and Bureaucratic Control

In addition to remote personal control, organizations adopted and/or expanded forms of bureaucratic control to compensate for the lack of direct supervision. According to our findings, working activities during homeworking were less proceduralized (at least initially) among workers in occupations with a low degree of teleworkability, such as employees in direct contact with the public (teachers, medical professionals, social workers etc.), though with some heterogeneity among them. For instance, according to a job centre employee in Italy, at the beginning of homeworking, management introduced detailed guidelines on how to perform work and the communication tools to be used with the public. In other cases, such as teachers or psychiatrists, guidelines were tried out on the job, adapted by workers individually or collectively and, finally, formalized. The interviewees described the initial guidelines as very generic and devoid of any practical application:

“We saw immediately that parents could not do what was proposed to us by the hierarchy. From there I said to myself: "This is what I want my students to continue to do at home. This is what parents can spend their time doing: printing, opening a mailbox, setting up these activities. That's what parents have at home, and that's how my students are going to get it." So, I had a lot of parameters to take into account in order to develop a tool that would be the least bad, I would say, possible.”

[France, primary school teacher in a public school (ISCO 2341)]

Homeworking progressively stabilized, and new rules and protocols were introduced. In some schools, for instance, managers introduced precise guidelines, which detailed the way in which online teaching activities were to be carried out and communication tools to be used, thus helping align and standardize homeworking across the organization. During the restoration of standard routines, autonomy gave way to discretion because teachers no longer had the choice of what tools to use and how to organize their online teaching activities (e.g., how long online lessons should last) but were obliged to follow more precise directives that restrained and regulated their freedom of choice. At the same time, they still had a degree of discretion among a limited number of alternatives:

“Our video lessons, according to the principal's guidelines, must not exceed 20 minutes, because the students struggle to follow a video lesson and the teacher must necessarily prepare his lessons to carry them out on audio and video platforms. We have therefore adapted to the guidelines of the principal [...]. Even the methods of distance learning regarding the use of the electronic register were specified in the guidelines.”

[Italy, high school teacher in a public school (ISCO 2330)]

Forms of bureaucratic control, as we noted above, may replace direct supervision by managers or employers. Within a very broad spectrum of occupations, supervisors have tried to make up for the absence of direct supervision through new bureaucratic procedures that workers would have to follow to self-certify their work (written reports detailing the activity carried out or the hours worked). Such actions, however, seem to have been taken solely to monitor worker activity in a specific context:

“The supervisor has asked us to make a report of our weekly activities: how many registrations, how many calls, etc.…”

[Italy, job centre official (ISCO 3353)]

“The first two weeks they asked us to send a report via email in which we reported what we had done during the week. After the first week of March they no longer asked for anything.”

[Italy, editor in a publishing house (ISCO 4413)]

In other cases, however, the transition to homeworking provided the organizational context for the virtualization of some control procedures aimed essentially at preventing episodes of worker misbehaviour. In particular, in the case of private-sector employees, the short-term gain in autonomy after the introduction of telework was subsequently lost during the stabilization period, when managers restored their decision-making power (and production targets). This reversal brought a dynamic of standardization: creation of new, specific procedures adapted to telework and likely to become permanent (though not always), precisely because their virtualization seems to guarantee greater effectiveness:

“In early April, a weekly planning mechanism was set up. Previously we had no mechanism for weekly activity planning. On Monday the supervisor is now forced to give the HR department a weekly plan, so we started having a meeting every Monday with my team, where there is a discussion on the priorities of the week. [...] Now, there is a schedule with all the projects, the people assigned to the projects for that week, and therefore much more organized planning, because it must be presented to the HR.”

[Italy, service designer in an automotive firm (ISCO 2421)]

“There are processes that require hierarchical authorizations, and many times it becomes confusing because people outside [sales representatives] either do not know or pretend not to know that there are hierarchical levels and try to override for personal benefits... [...] So we have prevented this situation and we have started to provide authorizations through virtual devices before proceeding to issue the documentation... So the processes have remained the same but are now virtual.”

[Italy, sales and marketing manager in an electromedical manufacturing company (ISCO 1221)]

Finally, for many clerical workers and professionals in lower or middle positions in the organization of work, and whose work had already been highly standardized in terms of codified and pre-established procedures to be monitored by means of ICTs, the degree of standardization of their activities did not seem to have changed during the transition to homeworking:

“I follow the same protocol that I followed before. [...] The procedures are standardized: when I have to prepare documents, make electronic filings, etc. The tasks that are assigned to us by the lawyers by e-mail are already standardized too.”

[Italy, secretary in a law firm (ISCO 4120)]

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Our article is a contribution to the debate on telework, specifically how homeworking has affected forms of control over work and workers. In sum, our findings suggest that the impact of homeworking is not unequivocal and strongly depends on the worker’s position within the organization and on the degree of teleworkability of the worker’s job.

In terms of the dialectic between worker control and managerial control, two distinct phases emerged in the transition to homeworking. During the first phase, i.e., the early part of the transition, there emerged a large, wide-ranging increase in autonomy. That increase is partly explained by a context of disruption, which in some cases produced a feeling of being abandoned by the upper hierarchy and management. The second phase started when new work practices were consolidated and managerial control to some extent restored. In general, worker autonomy was restrained or gave way to discretion.

Direct personal control (i.e., monitoring by supervisors, colleagues or customers) underwent both qualitative and quantitative changes. Some workers, who worked mainly in small organizations and who were often in contact with their managers, reported an increase in remote supervision via communication devices (phone calls, WhatsApp). Even though these forms of control have questionable effectiveness (see Kurkland and Bailey, 1999), their implementation by management shows their practical usefulness as a substitute for direct control and their managerial necessity (Felstead et al., 2003; on the role of peer scrutiny, our evidence is consistent with Sewell and Wilkinson, 1992). Workers in lower positions in larger organizations also reported a substantial increase in remote control, which very often took the form of recording and listening to their activity. Interestingly, contrary to evidence in the existing literature (e.g. Olson and Primps 1984; Steine 1988; Kraut 1989; Huwes et al., 1990; Korte and Wynne 1996), an increase in remote control was reported also by some workers in higher positions, for whom the use of technical devices for remote connection to corporate networks (such as VPNs) was perceived as a means to strengthen surveillance.

With regard to bureaucratic control, across a very broad spectrum of occupations, supervisors tried, more or less successfully, to make up for the absence of direct supervision by establishing new procedures or expanding existing ones, and imposing them unilaterally on the workers. They also introduced forms of standardization of remote work practices as a way to regulate and restrain the short-term gains in autonomy by some workers after the massive shift to homeworking. All in all, the period of stabilization saw an increase in control, especially through the imposition of bureaucratic forms of control.

Building on these findings, our study contributes to evidence that personal control is crucial for employers and managers. Personal control remains a decisive part of managerial power. When it cannot be exercised, management is forced to replace it with alternative forms of remote control, which in the long run can be equally, if not more, pervasive. In contrast to accounts that tend to consider personal control as a primitive form of supervision (Edwards 1979, 1984), which is later superseded by more sophisticated techniques, our study aligns with other evidence that Edwards’ three forms of control complement each other and are not stages in a linear succession (Littler and Salaman 1982; Thompson 1983; Callaghan and Thompson 2001; Sturdy et al., 2010). With personal control relying on either new technologies of real-time control (e.g. VPN, chats and other communication software) or forms of standardization (e.g., recording or reporting), the boundaries become blurred between forms of control. In some cases this hybridization could lead to an extension of control to categories of workers who had been previously more or less unaffected, especially the higher ranks of the organizational hierarchy (see Moore, Upchurch and Wittaker, 2018). Such extension of monitoring, however, does not undermine occupational hierarchies, which still mediate concrete application of the forms of control.

Finally, we should mention four more considerations. First, our findings refer to the initial phase of the pandemic and cannot be generalized, given the exceptional circumstances of that specific period. We have confirmed, however, many of the arguments and hypotheses already advanced in the relevant literature: the social relations prevailing in the workplace influence how work is reorganized at remote locations. Second, with existing forms of control being expanded for homeworking, and new ones introduced, management seeks to avoid losing power (and discipline) to the workforce. Third, the trend toward bureaucratization affects not only the workers in lower positions but also, in some cases, those in middle or top positions. Indeed, as we have seen, although workers gained autonomy during the first phase, they soon lost those gains. Fourth, we have shown that an external shock—the pandemic—caused the adoption of homeworking by organizations and occupations that had previously not been expected to adopt it to any significant degree. Our study is limited to the initial phase, but further longitudinal research could reveal the long-term impacts of this organizational shock.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Views and opinions expressed in this paper do not in any way reflect those of the European Commission and the Joint Research Centre.

-

[2]

The author acknowledge financial support by ARTES 4.0. Views and opinions expressed in this paper do not in any way reflect those of ARTES 4.0.

-

[3]

The study was originally carried out for and funded by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, Seville.

-

[4]

Our selection of country cases is justified by the widespread lockdown in France and Italy during the first wave of the pandemic. Because we chose to include the largest panel of occupations in our survey and used in-depth qualitative interviews, it was no longer possible to make a cross-national comparison. We thus gave up on the France-Italy comparison and focused on making a cross-occupational comparison.

-

[5]

Beyond work organization and labour relations, the interviews also covered two other topics of interest: (a) job-quality impacts of the transition to telework; and (b) work-life balance. Though important, those topics are beyond the scope of this paper and are addressed elsewhere.

-

[6]

By hierarchical position we mean the worker’s place within the organization of work and the unevenly distributed resources of power and knowledge that correspond to that place. Hierarchical position and autonomy are two interlinked dimensions. A commanding position in the hierarchy corresponds to the “ability of some agent (the ‘ruler’, the authority) to determine the set of actions available to the other agents (the ‘ruled’) [or even] the ability or the authority to influence or command the choice within the ‘allowed’ choice set” (Dosi and Marengo, 2015: 538; see also Cetrulo et al., 2020b).

Bibliography

- Aguilera, A., Lethiais, V., Rallet, A., & Proulhac, L. (2016). Home-based telework in France: Characteristics, barriers and perspectives. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 92, 1–11.

- Alipour, J. V, & Falck, O. (2020). Germany’s Capacities to Work from Home, CESifo Working Paper No. 8227.

- Alvesson, Mats and Dan Karreman (2011). Qualitative Research and Theory Development: Mystery as Method. Sage.

- Bisello, M., Fana M., Fernández-Macías, E., M., Torrejon-Perez, S. (2021). A comprehensive European database of tasks indices for socio-economic research, No. 2021-04, JRC Working Papers on Labour, Education and Technology, Joint Research Centre (Seville site).

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218.

- Braverman, H. (1974). Labor and Monopoly Capital. Monthly Review Press.

- Callaghan, G., Thompson, P. (2001). Edwards Revisited: Technical Control and Call Centres. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 22(1), 13-37.

- Cetrulo, A., Guarascio, D., & Virgillito, M. E. (2020a). The Privilege of Working from Home at the Time of Social Distancing. Intereconomics, 55(3), 142–147.

- Cetrulo, A., Guarascio, D., & Virgillito, M. E. (2020b). Anatomy of the Italian occupational structure: concentrated power and distributed knowledge. Industrial and Corporate Change, 29(6), 1345–1379.

- Clear, F. and Dickson, K. (2005). Teleworking practice in small and medium-sized firms: management style and worker autonomy. New Technology, Work and Employment20(3), 218-233.

- Corbin, Juliet M. and Anselm Strauss (1990). Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3-21.

- Dimitrova, D. (2003). Controlling teleworkers: Supervision and flexibility revisited. New Technology, Work and Employment, 18(3), 181–195.

- Dingel, J., & Neiman, B. (2020). How Many Jobs Can be Done at Home?. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104235

- Dosi, G. and Marengo, L. (2015). The dynamics of organizational structures and performances under diverging distributions of knowledge and different power structures, Journal of Institutional Economics, 11(3), pp. 535–559.

- Edwards, R. (1979). Contested Terrain: The Transformation of the Workplace in the Twentieth Century. Basic Books.

- Edwards, R. (1984). Forms of Control in the Labor Process: An Historical Analysis. In: F. Fischer F. and Sirianni C. (eds), Organization and Bureaucracy. Temple University Press, pp. 109-42.

- European Framework Agreement on Telework, EUR-Lex (2002). https://resourcecentre.etuc.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/Telework%202002_Framework%20Agreement%20-%20EN.pdf

- Eurostat (2021). Employed persons working from home as a percentage of the total employment. Eurostat Database.

- Fana, M., Torrejón, S., & Fernández-Macías, E. (2020). Employment impact of Covid-19 crisis: from short term effects to long terms prospects. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics 47, 391–410.

- Felstead, A. & Henseke, G. (2017). Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, well-being and work–life balance. New Technology, Work and Employment 32(3), 195-212.

- Felstead, A., Jewson, N., & Walters, S. (2003). Managerial Control of Employees Working at Home. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 41(2), 241–264.

- Fernández-Macías, E. and Bisello, M. (2022). A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Tasks for Assessing the Impact of New Technologies on Work. Social Indicators Research 159, 821–841

- Galasso, V., & Foucault, M. (2020). Working after covid-19: cross-country evidence from real-time survey data. Sciences Po publications 9, Sciences Po.

- Hensvik, L., & Le Barbanchon, T. (2020). Which Jobs Are Done from Home? Evidence from the American Time Use Survey, CEPR Discussion Paper, No. DP14611.

- Huws, U., Korte, W. B., & Robinson, S. (1990). Telework: Towards the Elusive Office. Wiley.

- Illegems, V., Verbeke, A., & S’Jegers, R. (2001). The organizational context of teleworking implementation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 68(3), 275–291.

- Korte, W. B., & Wynne, R. (1996). Telework: Penetration, Potential, and Practice in Europe. IOS Press.

- Kraut, R.E. (1989). Telecommuting: The Trade-offs of Home Work. Journal of Communication, 39(3): 19-47.

- Kurkland, N. B., & Bailey, D. E. (1999). The advantages and challenges of working here, there anywhere, and anytime. Organizational Dynamics, 28(2), 53–68.

- Littler, C. R., Salaman, G. (1982). Bravermania and Beyond: Recent Theories of the Labour Process. Sociology, 16(2), 251–69.

- Maggi, B. (2016). De l’agir organisationnel. Un point de vue sur le travail, le bien-être, l’apprentissage. TAO Digital Library.

- Mazmanian, M., Orlikowski, W., & Yates, J. (2013). The autonomy paradox: The implications of mobile email devices for knowledge professionals. Organization Science, 24, 1337–1357.

- Messenger, J. (2019). Telework in the 21st Century: An Evolutionary Perspective. Edward Elgar.

- Neirotti, P., Paolucci, E., & Raguseo, E. (2013). Mapping the antecedents of telework diffusion: Firm-level evidence from Italy. New Technology, Work and Employment, 28(1), 16–36.

- Nilles, J. M. (1975). Telecommunications and Organizational Decentralization. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 23(10), 1142–1147.

- Olson, M. H. (1988). Organizational barriers to telework. In: W. Korte, S. Robinson and W. Steinle (eds), Telework: Present Situation and Future Development of a New Form of Work Organization. Elsevier Sciences, 77–100.

- Olson, Margrethe H., & Primps, S. B. (1984). Working at Home with Computers: Work and Nonwork Issues. Journal of Social Issues, 40(3), 97–112.

- Pouliakas, K., & Branka, J. (2020). EU Jobs at Highest Risk of COVID-19 Social Distancing: Will the Pandemic Exacerbate Labour Market Divide? IZA Discussion Paper, 13281.

- Pyöriä, P. (2011). Managing telework: Risks, fears and rules. Management Research Review,34(4), 386–399.

- Sewell, G., & Taskin, L. (2015). Out of Sight, Out of Mind in a New World of Work? Autonomy, Control, and Spatiotemporal Scaling in Telework. Organization Studies, 36(11), 1507–1529.

- Sostero, M., Milasi, S., Hurley, J., Fernandez-Macías, E., & Bisello, M. (2020). Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide? LET Working Paper Series 5/2020.

- Steinle W. (1988). Telework: Opening Remarks on an Open Debate. In: W. Korte, S. Robinson and W. Steinle (eds), Telework: Present Situation and Future Development of a new Form of Work Organization. Elsevier Sciences, pp. 7-23.

- Sturdy, A., Fleming, P. & Delbridge, R. (2010). Normative Control and Beyond in Contemporary Capitalism. In: Thompson, P. & Smith, C. Working Life: Renewing Labour Process Analysis, Palgrave-MacMillan, 113-135.

- Taskin, L., & Edwards, P. (2007). The possibilities and limits of telework in a bureaucratic environment: Lessons from the public sector. New Technology, Work and Employment, 22(3), 195–207.

- Thompson, P. (1983). The Nature of Work. MacMillan.

- Toffler, A. (1980). The Third Wave. Bantam.

- Vallas, S. P. (1999). Rethinking Post-Fordism: The Meaning of Workplace Flexibility. Sociological Theory, 17(1), 68–101.

- Vidal, M. (2022). Management Divided. Contradictions of Labor Management. Oxford University Press.

- Zuboff, S. (1988). In the Age of the Smart Machine. Basic Books.

List of tables

Table 1

Distribution of Interviewees by Occupation at ISCO-08 One- and Four-Digit Level

Table 2

Distribution of Interviewees by Selection Criteria