Abstracts

Abstract

This essay sets out to solve the strange case of the “disappearance” of the Poet Laureate, Robert Southey, in his own 1829 book of “imaginary conversations” or Colloquies with the ghost of Sir Thomas More. There is no “Southey” in the dialogue, only a figure named “Montesinos.” But since the pessimistic ghost of More evidently speaks for Southey—as readers from the Westminster Review in summer 1829 onwards have noticed—then the dialogue is strangely one-sided. If More is Southey, then “who,” as Mark Storey’s biography asks, “is Montesinos?” This essay seeks to answer Storey’s biographical question, and to put it into the wider context of Southey’s ideas about national and writerly identity, and his Romantic poetics of history. The first part explores “Montesinos” as a byword for Southey’s literary utopianism. The second part then attempts the resurrection of “Montesinos,” tracing this figure in the detail of Southey’s “Hispanist” reading and in the workings of his historical imagination. I conclude with reflections on the implications of Southey’s ‘hieroglyphic’ mode of life-writing for historicist approaches to Romantic studies today, including the ‘new counterfactualism’ and the ‘speculative revivals’ of ‘Romantic biography’.

Article body

Robert Southey’s ghost-dialogue, Sir Thomas More: or, Colloquies on Society (1829), presents itself as an English literary history—in a richly compound sense. In one of the central colloquies, the “spiritual visitor” Thomas More asks what it is to be “English at heart,” and evinces his own feeling for the “old house” of the constitution (STM 192, 258). A presiding “national” character also appears on the face of the book, seen in the Old English type used for the main title, in the frontispiece engraving, after Hans Holbein’s 1527 portrait of More as a privy councillor (see figure 1), and in the laureate poem manqué, the “Dedication.” “Robert Southey, Esq. LL.D. Poet Laureate” features on the title page with the full list of his honours: including honorary membership of such bodies as the Metropolitan and Philomathic Institutions.

Figure 1

“Portrait of Sir Thomas More.” Painted by Hans Holbein, engraved by Edward Finden.

The scene is laid—in terms that recall Southey’s A Vision of Judgement (1821)—in the laureate’s famous “Cottonian” library at Greta Hall, and among “these lakes and mountains” (STM 2). The “northern parts” of the English Lakes, with “little or nothing” to show “of historical or romantic interest” (STM 245), are nevertheless presented in the text as the classic ground of the “matter of Britain”; of “English eerie” and “ghost soil.”[1] An excursion to Castlerigg—the circle of megaliths on the “soil … not broken” of the “high hill” by the Penrith road—summons a sublime “feeling” of deep time, and a “spirit” from the silent stones. “[M]using upon the days of the Bards and Druids … wishing that th[e] stones could speak,” or bore “some record … though it were as unintelligible as the hieroglyphics,” “I saw a person approaching, and started a little at perceiving that it was my new acquaintance from the world of spirits.” “I am come,” says Sir Thomas More, “to join company with you in your walk: you may as well converse with a Ghost, as stand dreaming of the dead” (STM 24).

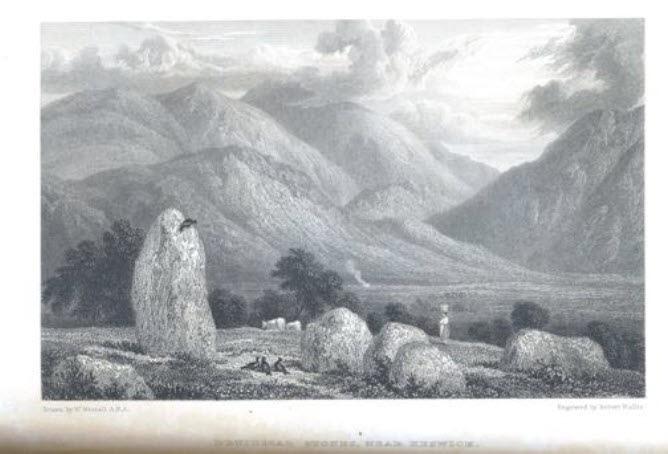

Figure 2

“Druidical Stones, near Keswick.”

The language of the first colloquy, “The Introduction,” maintains a continual background allusion to the English literary origin-myth of Hamlet, which snaps into focus at the arrival of More, the English Catholic time-ghost:

I was awakened … by the entrance of an elderly personage …[H]e accosted me in a voice of uncommon sweetness, saying, Montesinos, a stranger from a distant country may intrude upon you without those credentials which in other cases you have a right to require. From America? I replied, rising to salute him. …You judge of me, he made answer, by my speech. I am, however, English by birth, and come now from a more distant country than America, wherein I have long been naturalized.

STM 2

After a conversation of some minutes, the visitor confirms the suspicion about his identity, again in the language of Hamlet:

I told you truly that I was English by birth, but that I came from a more distant country than America, and had long been naturalized there. The country whence I come is not the New World, but the other one: and I now declare myself in sober earnest to be a Ghost.

STM 7

The earliest readers were jolted out of this deepening field of “national” feeling, however, by the “foreign” brush-hair in the canvas: “Montesinos.” The un-English name was echoed back to Southey by the editors of Blackwood’s Magazine—his professed allies in “anti-Catholic[ism]” and “friends[hip]” to the “Church of England”—as “Misopseudos” (Noctes Ambrosianae, no. 47, see STM 748-774, 759, 774). Southey’s friend, the Parliamentary official and census-taker John Rickman, meanwhile, referred to the “outlandish Spanish name”—which was also likely to be “understood by few” (John Rickman to Robert Southey, January 14, 1831, RLL 272). For Rickman, interested in watchwords for “incognito” publication, and in defending government based on “influence,” an incomprehensible name might be none the worse for that (Selections IV 367-369; RLL 259-260, 271-272). But Southey as a professional author could not afford to be quite so sanguine. It was “always desirable to have a peculiar title,” he told Caroline Bowles in January 1826, with his own sequel-generating Book of the Church (1824) in mind, since the “name” quickly came to stand in for the thing itself (CRSCB 95-6). But the reviewer of an advance copy of Colloquies for the Literary Gazette had, he complained to Caroline in April 1829, been so blinded by the peculiarity of “Montesinos” as not only to miss any more refined levels of reference, but to garble the overall allusion to Hamlet: “giving as a specimen an extract altogether unlike any other part of the book, and explaining Montesinos to mean a stranger from a distant country! And these are the critics upon whose good or ill report the sale of a book among book societies mainly depends!” (CRSCB 156).

To those in the know, “Montesinos” might suggest a re-doubling of the transparently English “Spaniard” of Southey’s Letters from England, by Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella (1807). Writing from the point of view of Espriella, an “able” but “bigoted” Spaniard whose historiography features “bloody Elizabeth” and the “sunshine of Philip and Mary’s reign” (LFE 196, 200), Southey correlated two national “times” or “states” and subverted two national myths at once. Espriella “discovers” in England “such symptoms of a declining power as may soothe the national inferiority, which he cannot but feel” (Selections I 282). Southey’s friend and fellow Anglican polemicist, Blanco White (born José María Blanco y Crespo), had sought his advice and taken his Espriella’s Letters as a model when developing his own Spanish-English figure in Letters from Spain, by Don Leucadio Doblado (1822; see CLRS 1978). Explaining the name in this title to mean “whiteness doubled,” Blanco’s preface to the second edition of 1825 put a further spin on the “Hispanist” play of pseudonymy that Southey—“leading the way in a mania for Spanish subjects” since 1797 (LFE 19)—had begun. As Carol Bolton notes, building on the work of Diego Saglia and Tim Fulford, Spain figured in late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century British writing as a sort of movable South, by which to set the sliders of Englishness: alternately the “rapacious imperialist” “other” of the “mild, commercial British,” and the site of “kindred … national loyalties, once Spain had been drawn into the war against France” (LFE 17). Situating himself within this tradition, Blanco insisted that the false name, understood rightly, was actually a token of “complete authenticity.” The adoptive Englishman lived “perfectly at variance” from his “countrymen,” Blanco suggested, having been “forced” himself by the linguistic insularity of the English to live under a tautologous name (White iv).

Just such a “perfect” national “variance” is visible in each of the apparently straightforwardly “English” features on the face of the Colloquies. The presiding presence of Thomas More, the English Catholic minister of state and European diplomat, executed for refusing the royal supremacy, gives a personal form to the urgent contemporary “question” of Catholic Emancipation, and the looming challenge to what Southey’s preface refers to as “the Protestant Constitution of these kingdoms” (STM lxxxv). But by continually invoking More’s Utopia (1516), and seeding various allusions in his text to More’s status as a forefather of European political union, signatory to the 1518 “Treaty of London,” or of “Universal Peace” (see STM 385-393, 668 n. 773), Southey suggests the European—on the way to the “global”—dimensions of Englishness.

“The Dedication,” meanwhile, meditates at length on Holbein’s image of More in his prime as a “prophetic counterfeit” of Southey’s uncle the Rev. Herbert Hill, who had spent a quarter of a century overseas in Portugal (1782–1807), and died shortly before Colloquies was published, in 1828. The king’s councillor of the 1520s “prefigure[s] thus,” says Southey, the “benevolen[t]” “mien” of the Anglican chaplain of the Lisbon factory in the 1790s (STM lxxix-lxxxiii; ll. 14, 31-34). The picture and the poem combine to articulate the central historiographical theme of the Colloquies—that curious matter and randomly “found” facts or personal experiences gradually form into meaningful historical shapes. But the poem concludes by imagining for Herbert Hill another kind of virtual second life, spanning the Atlantic and translated into the form of Southey’s library “labours” as (Luso-)Hispanist and historian. If he can yet “consummat[e]” his and Herbert’s thirty-year joint project to write the global history of Portugal—a land “nor yet / To be despair’d of, for not yet, methinks, / Degenerate wholly”—then, Southey hopes,

ll. 126-128, 137, 167-168, 169-179“Our names conjoin’d” may “long / Survive,”

Where old Lisboa from her hills o’erlooks

Expanded Tagus […]

Nor there alone; but in those rising realms

Where now the offsets of the Lusian tree

Push forth their vigorous shoots … from central plains,

Whence rivers flow divergent, to the gulph

Southward where wild Parana desembogues,

A sea-like stream; and northward in a world

Of forests, where huge Orellana clips

His thousand islands with his thousand arms.

Alluding to the Lusiad (1572), the Portuguese national epic of Luis Vaz de Camões, and to geographical descriptions (of the Planalto Central, the Plata, and the Amazon) in his own three-volume History of Brazil (1810-19; see STM 524-525 n. 34), Southey ultimately “dedicates” the Colloquies not to “the Protestant Constitution” (STM lxxxv), but to his longstanding and consistent view of Spain, Portugal, and South America as the lands of historical destiny. In his Letters Written During a Short Residence in Spain and Portugal (1797), Southey had suggested that neither nation had “attained to the aera of Taste” that should have followed their “short and rapid” “rise” to the “aera of Genius.” But though they had “languished” long under “the double tyranny of their Kings and Priests,” there was life in the embers of both nations (125-126). When Napoleon invaded Portugal in 1807, and the monarchy fled to the old colony of Brazil, Southey perceived the recrudescence of an historical opportunity (missed by England and the USA): to forge a lasting blend of old and new worlds, to “temper” monarchy “with a wholesome mixture of democracy” (HoB III 870). Being a place “where good laws, and good old customs, have only fallen into disuse,” as Southey put it in his History of Brazil (III 870), Luso-America seemed to offer the historian the opportunity, in turn, as Mark Storey puts it, to “shape the future” (Contexts, 91).

Colloquies develops this historical concept at length, connecting the South American past and future with the English past and present. The dialogues between More and Montesinos feature repeated imaginary “excursions” from Keswick to the “Chiquito [and] Paraguay Reductions” of the Jesuits—from the Greta to “the Guapore and the Uruguay” (STM 79). But the kind of “perfect variance” thus suggested between Southey and the “More” and “Montesinos” of the Colloquies was immediately ruled out of bounds by Thomas Macaulay. In his “classic” essay on Colloquies in the Edinburgh Review, Macaulay pronounced the name “Montesinos” “somewhat affected,” while the calling-in of Sir Thomas More “to say what any man might have said” was simply “grotesque” (STM 794, 843). “What a contrast,” he exclaimed, between this “monkish” and “absurd fiction” of a ghost-dialogue with a “great” Tudor “statesman and philosopher,” and the dialogue form as practiced by Plato and Cicero (STM 790-794). Southey’s two long volumes, Macaulay suggested, were merely “an amplification” of two “absurd paragraphs” in Colloquy X on the interfusion of the two (actually quite separate) issues of religion and education, cast into the equally “absurd” form of a conversation between what was in reality just “two Southeys” (STM 193-194, 802, 794).

Macaulay’s comments were themselves an “amplification” of Francis Jeffrey’s earlier attacks on Southey’s “outlandish” works and characters: Thalaba (1801), a “tissue of adventures,” strung together with a heroic cipher, and Espriella’s Letters (1807), a mere “deception,” “sp[u]n out” to cover a lack of “native ingenuity” (RSCH 84, 121-122). In the Wat Tyler affair of 1817, William Hazlitt joined in with the character assassination initiated by William Smith, MP in the House of Commons, reading the pirated text of the 1794 play by the young radical medievalist against the unsigned essay on reform that the laureate had just published in the conservative Quarterly Review. Pitting “the one” Southey against “the other,” Hazlitt produced a caricature of the Wordsworthian “theory of personal continuity”: the foolish “Ultra-royalist” “man” appearing as the superannuated “child” of the “Ultra-jacobin” and “effeminate” “son” (“Two Reviews”). Southey’s self-vindicating Letter to William Smith (1817) only proved the point. Arguing best “when he argues against himself,” Southey was a “painful hieroglyphic of humanity” (SWWH IV 193). And in TheSpirit of the Age (1825), Hazlitt finished his portrait of the laureate as a man almost entirely without inwardness, but profoundly “unsettled”—“born an age too late”—by “the distraction of the time” (SWWH VII 216-218). Superficially engine-turned, able to switch genres and subjects “by a stop-watch,” Southey nevertheless remained a radical at heart: “wild, singular, irregular, extreme.” “No man can entirely baulk his nature: it breaks out in spite of him.” And it was, paradoxically, Southey’s “unremitting” and “mechanical” attempt to route his radical “nature” entirely through an accumulation of surface texture that made him for Hazlitt a sort of “hieroglyphic” of the spirit of the age: his works the “trances” rather “than the waking dreams” of Romantic poetry.

Recalling these attacks on Southey’s ill-formed “plans” and distorted character and career, and perhaps anticipating Coleridge’s 1832 comments on having “no admiration for the practice of ventriloquizing through another man’s mouth,” Macaulay pictured the Colloquies as a “picturesque” and bizarrely nostalgic ramble through a hundred random subjects, patched together between two non-entities (STM 792-794, 797; TT I 308-309). Between, that is, a travesty of Thomas More—“the glorified spirit” reduced to “a bilious old Nabob”—on the one hand, and the nothing-man of “Montesinos, as Mr. Southey somewhat affectedly calls himself,” on the other (STM 794, and qtd. 843).

“Affected” the pseudonym might have been, but out of keeping with its genres of dialogue and utopia it was not. In utopian writing, as Gregory Claeys points out, names matter (Claeys 57). Claeys makes the point in relation to the title of one of the various pseudo-sequels to Southey’s book—the Owenite philanthropist John Minter Morgan’s Hampden in the Nineteenth Century: or,Colloquies on the Errors and Improvement of Society (1834). But Morgan’s book also includes a fictional episode that expands—even as it seems to solve—the mystery of “Montesinos.” Repeating the real-life visit of his mentor, Robert Owen, in summer 1816, Morgan’s narrator, Fitzosborne, comes to Keswick hoping to discuss the laureate’s ongoing work on social progress and on Sir Thomas More. He is disturbed to find, however, that no such individual is known there, and to be directed instead to “a gentleman” who walks “beside the lake with a volume in his hand,” called “Montesinos” (II 28). Visiting his house and library, and reading a manuscript containing “dialogues” between “Montesinos” and “Sir Thomas More,” Fitzosborne leaps to the conclusion that his unknown “host” must be the figure precisely absent in the text: “none other than Robert Southey himself.” Southey had clearly “assumed the name of Montesinos,” though “for what reason I could not divine” (II 28-31).

Readings like Morgan’s suggest the inadequacy of Macaulay’s flat suggestion of two simply interchangeable “Southeys.” Indeed, the passage singled out by Macaulay, featuring More’s “absurd” words on the state “secure in proportion as the people are attached to its institutions” (STM 193-194), suggests something quite different again. For these words are exactly the words of Southey himself—repeated almost verbatim from a pamphlet and Quarterly Review essay of 1811-12 (Southey 1812 106–107; QR 6:11 [1811] 289). If “Sir Thomas More” is thus evidently, as Mark Storey puts it, “often Southey’s own mouthpiece,” articulating opinions that had been his own since the 1810s, then Storey’s follow-up question, “who is Montesinos?,” gains a real literary-biographical point (Storey 316). Or rather, since “Montesinos” is evidently—to combine Morgan, Hazlitt and Macaulay—the “other Southey,” the question now becomes: “… and who—by 1829—was that?”

I. Et in Utopia Ego

This essay seeks to answer Storey’s question. The second part attempts the detailed resurrection of “Montesinos,” seeking to trace this figure in the workings of Southey’s historical imagination. But before turning to this work, which might otherwise seem as abstruse as the name “Montesinos” itself, I want to indicate the larger context in which the academic or biographical question resonates. Southey’s belief in the importance of “peculiar titles” reflects an overarching and life-long preoccupation with emblems, catch phrases, and catachresis in general. The habit goes at least as far back as The Flagellant in 1792, the school magazine in which Southey wrote against corporal punishment as “Gualbertus”—a name adapted from John Gualbert (c. 995–1073), founder of the Vallombrosian order (see CLRS 28). It also went at least as far forward as Southey’s “incognito” Shandean novel or “disguised diary,” The Doctor (see Selections IV 367-369; and Chandler 616-617). In preparation for this project, Southey sat to his friend the artist Edward Nash (1778–1821) for a “back portrait” or “reariture”.

Figure 3

“Portrait of the Author.” Drawn by Edward Nash, engraved by J. T. Willmore.

The image was used, eventually, as frontispiece to the posthumous one-volume edition of 1848, with the disarming caption, “Portrait of the Author” (see CLRS 3607, 3637). Southey’s alter-egos were thus always as much self-revelation as disguise, with something of the “perfect variance” of “Leucadio Doblado”—or what Jacques Derrida, reading the Ghost scenes in Hamlet, refers to as the “visor effect” of “dissimulation” to an unknowable, though possibly total, extent (7-8). At the very start of the Colloquies project in late 1817, while “Montesinos” was still in the embryonic form of “meipsum,” Southey considered reviving the “assumed character” of “Espriella,” since it had allowed him to speak freely both “in” and “thro” the disguise, leaving his true view “to the readers sagacity to discover” (CLRS 3051).

The “assumed character” provided useful political cover. But recent criticism also suggests a possible reading of Southey’s various acts of cryptic self-reference, and what he referred to as their “strict etymological yet non-apparent relations” (Selections IV 205-206), in terms of the emergent “depthless” complexity (“either unimaginably deep or having no depth at all”) of what Seamus Perry calls the “exoskeletal,” and Andrew Warren the “arabesque” mode—of Southey’s own variety of Romanticism (see Morton 59; Perry 18-19; Warren 54-59). The locus classicus for this Southeyan mode of speaking truth “in” and “thro” a disguise is the exotic epic Thalaba (1801). Here, as both Tim Fulford and Andrew Warren suggest, Southey set himself the impossible task of contriving an English work of Islamic mythology with all the “purities of Poetry”—“pure truth, pure language, and pure manners” (Preface to Madoc [1805] EPW II 6)—even while, “[s]peaking no eastern language, knowing no Orientalist scholars,” he was constrained to “discern” his inward essence of Islam from in amongst a flood of fanciful translations, imitations, and forgeries (EPW III x; Warren 54). At the micro-level of local texture, meanwhile, the model is again Thalaba, and Okba’s rebuke to the Dom-Danielites, where the contortion of the sign-system both creates and subverts, with the hanging force of “he,” the idea of an inert and self-sufficient sign: “Ye frown as if my hasty fault, / My ill-directed blow / Had spared the enemy, / And not the Stars that would not give, / And not your feeble spells / That could not force, the sign / Which of the whole was he” (II 67-73; see also Warren 66). The Southeyan “forced sign” is a sort of depthless-ecological or “hieroglyphic” answer to the embodied interiority of Wordsworth’s “spots of time”; De Quincey’s “involute” not “carried far” but interrupted—a tattoo—at the level of the skin (see Wu ed. 850-851).

Southey is indeed the “exoskeletal” embodiment of Wordsworth’s distributed definition of the Poet as a global historian of feelings.[2] He described himself in 1804 as having “more in hand than Bonaparte or Marquis Wellesley. digesting Gothic law, gleaning moral history from monkish legends & conquering India, or rather Asia, with Alboquerque—filling up the chinks of the day by hunting in Jesuit-Chronicles, & compiling Collectanea Hispanica & Gothica” (CLRS 922). In January 1805, Southey announced to John Rickman his manifesto for a “triadic” or emblematic historical poetics:

my rule […]—nay—you shall have it in a Triad—the three excellencies of historical composition—language as intelligible as possible—as concise as possible, & as rememberable as possible. Nothing provokes me like a waste of words. Me judice I am a good poet—but a better historian, & the better for having been accustomed to feel & think as a poet.

CLRS 1024

This became Southey’s lasting self-image. In 1817, he had Longmans advertise the second volume of his History of Brazil (1810-19) with the would-be “mortifying” comment of a reviewer in the Monthly on the first: “we like him (Mr. Southey) much better as an Historian than as a Poet” (CLRS 2940). And the global-poet or “better historian” appears further transfigured in Colloquies (1829)—under the pressure of More’s critique of the “portentous bibliolatry of the age” (STM 19)—as the potentially all-seeing “man of letters.” “For whom is the purest honey hoarded that the bees of this world elaborate,” asks “Montesinos” the “gray-headed bookman” (STM 370) in Colloquy XIV, “The Library,” “if it be not for the man of letters?”

It was to delight his leisure and call forth his admiration that Homer sung, and Alexander conquered. It is to gratify his curiosity that adventurers have traversed deserts and savage countries, and navigators have explored the seas from pole to pole. The revolutions of the planet which he inhabits are but matters for his speculation; and the deluges and conflagrations which it has undergone, problems to exercise his philosophy … or fancy.

STM 349

The term eco-historicism, coined (albeit with a different inflection) by Gillen D’Arcy Wood in 2008, might thus be the right one to apply to this writer—who can often be seen in his letters pushing past his contemporary and historical sources to the next, “ecological” thought (see D’Arcy Wood 2008 1-7; and Morton 1-19). Tambora, which erupted in 1815, was a name as yet unknown. But Southey’s letters of November and December 1817 show him assembling fragments of information from newspapers and correspondents, and arriving almost simultaneously at an understanding of the dark heart of what D’Arcy Wood calls the “Years Without a Summer … 1816, 1817, and 1818,” in terms of “some great convulsion,” a “Volcano,” and also in terms of a ghost “returning” from a future-past.[3] “From America?” “Montesinos” will ask the stranger with the 1530s-accent, who “arrives” (along with the post and the newspaper) one day in the “melancholy November” after the death of the Princess Charlotte, and at another “grand climacteri[c] of the world” (STM 2, 10).

What is at stake in the identity of “Montesinos,” then, is the value of Romantic exoticism, “Orientalism” and “Hispanism”—as an effort of translation that forges forward, through inauthenticity, in hopes of coming to know a foreign culture from within. And at a time of writing when European—let alone “global”—composite identities are being daily de-composed by the so-called return of the nation, the issues involved are familiar and highly charged. In short: Is “Montesinos” a “somewhere” or an “anywhere”? Is he a model, alternatively, of “rooted cosmopolitanism”?

The text of Colloquies contains suggestions of an interestingly conflicted version of the latter. It is nostalgia for Cintra, Portugal, that Southey says attaches him to the Lakes, and, in particular, to the “Goldilocks” prospect (reached with “just” the right “degree” of “difficulty and enterprize”) over Walla Crag. The scene—reenacted at length in John Minter Morgan’s sub-sequel (Morgan II 35-45)—is summoned into presence as a “virtual topography,” in Tim Fulford’s phrase (2010, §29). A complex “involution” of time and space occurs in amongst Southey’s description of his viewing and reading habits, William Westall’s drawing of the scene that features Southey himself (see figure 4), and then the re-entrance of the ghost:

This was to be our resting-place […] My place was on a bough of the ash tree at a little distance, the water flowing at my feet, and the fall just below me. Among all the sights and sounds of Nature there are none which affect me more pleasurably than these. I could sit for hours to watch the motion of a brook: and when I call to mind the happy summer and autumn which I passed at Cintra, in the morning of life and hope, the perpetual gurgling of its tanks and fountains occurs among the vivid recollections of that earthly Paradise as one of its charms. When I had satisfied myself with the prospect, I took from my waistcoat pocket an Amsterdam edition of the Utopia […] I read till it was time to proceed; and then putting up the book, as I raised my eyes … behold the Author was before me.

Colloquy VI, STM 69-71

Figure 4

“Derwentwater, Bassenthwaite-Water & Skiddaw from Walla Crag.”

It is, in fact, as a citizen of Utopia or nowhere that Montesinos presents himself, when the ghost of More first suggests a dynamic historical parallel between their characters and their respective “ages” of England:

Sir Thomas More: I neither come to discover secret things nor hidden treasures; but to discourse with you concerning these portentous and monster-breeding times; for it is your lot, as it was mine, to live during one of the grand climacterics of the world. And I come to you, rather than to any other person, because you have been led to meditate upon the corresponding changes whereby your age and mine are distinguished; and because, notwithstanding many discrepancies and some dispathies between us, (speaking of myself as I was, and as you know me,) there are certain points of sympathy and resemblance which bring us into contact, and enable us at once to understand each other.

Montesinos: Et in Utopiâ ego. [translation: “Even in Utopia, there am I”]

Sir Thomas More: You apprehend me. We have both speculated in the joy and freedom of our youth upon the possible improvement of society; and both in like manner have lived to dread with reason the effects of that restless spirit […]

STM 10

“Et in Utopiâ ego. / You apprehend me.” What exactly is “apprehended” in these gnomic statements? The seven-word exchange, following More’s already terse evocation of a “dynamic” historical parallel, is an apt epitome of Southey’s views on style: “perspicuous,” “brief,” “rememberable” (CLRS 1670). The exchange of phrases mimes Southey’s effort to match More for “historical” compression. “Utopia,” as Southey notes in the scene of reading at Walla Crag, is the grand archetype of the “winged word”: “understood by thousands and tens of thousands who have never read the fiction from whence it is derived” (STM 71). Drawing attention to the way the book (in fact) survives the man, and the word (or concept) outgrows the work, Southey suggests the genuine historiographical gain in what appears to be only historical loss. And as Montesinos sets “Utopia” within a constellation of further allusions—to Spenser and to the memento mori paintings of Guercino and Poussin, via the classical tag “Et in Arcadia ego”—he suggests the historical burden that has come to attach to utopianism itself. It takes immense strength—Montesinos seems to imply—to wear so much learning so lightly. But More’s speech in the exchange also seems to predict T.S. Eliot’s response on behalf of the “dead writers”—who indeed knew less than us, because “they are that which we know” (Eliot 40): “Et in Utopiâ ego”—Yes, precisely—“You apprehend me.”

Identifying himself by way of an oblique compound allusion, rather than by a direct statement, “Montesinos” may seem to be entirely a “man of letters” in Byron’s—and Burke’s—more negative sense (see Byron’s journal entry, November 22, 1813, RSCH 157). So completely stuffed with print, he seems to have forgotten how—unlike Burke’s “unsophisticated … untaught” English—to “feel within” (Burke 70-77). But the “Et in utopia” phrase also has a specific history of its own that suggests the opposite. It is in fact recycled in Colloquies from the autobiographical context of the visits that Southey received in 1816 and 1817 from the philanthropic industrialist Robert Owen, and his own return visit to Owen and the model industrial settlement at New Lanark in 1819. With his “tin case full of plans,” Owen in Keswick in 1816 had seemed to the laureate like the risen spirit of a former self, the “odd personage” striking him as just “such a Pantisocrat as I was” (CLRS 2832). But as Southey recorded in his private journal, it was the sight of Owen’s practical “utopia” during his 1819 tour of Scotland that led to the more profound self-discovery:

Owen in reality deceives himself. … Et in Utopiâ ego. But I never … suppose[d], as Owen does, that men may be cast in a mould (like the other parts of his mill) and take the impression with perfect certainty. …He keeps out of sight from others, and perhaps from himself, that his system, instead of aiming at perfect freedom, can only be kept in play by absolute power. …The formation of character! Why the end of his institutions would be, as far as possible, the destruction of all character.

Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819 263-264

Pushing his analysis beyond the “scruples” of radicals such as William Cobbett about “parallelograms of paupers,” Southey arrives here at what Robert Davis and Frank O’Hagan call “a fundamental disclosure of the hidden … mainspring” of utopias in the need for “infinite jurisdiction” (see Davis and O’Hagan 174-175; and Political Register, 2 August 1817). The phrase “Et in Utopiâ ego” thus represents its own opposite: The perfect inward variance of the figure of “Montesinos” from the intersection of biographical and historical planes that combine to “name” the presence within the text of the undeceived author himself, and from the “formation” and “destruction” in the long years since pantisocracy of his own original character.

II. Montesinos: Poet, Rebel, Provincial, Spy

So, to put the question again: If Sir Thomas More (mutatis mutandis) is Southey, and Montesinos is “the other one,” then what, specifically, might Southey have meant by that? What, in short, were the meanings it was possible to read into or out of the name? A “Spanish name” for “mountaineer” or “man of the mountains,” “Montesinos” evidently reflects Southey’s Hispanist second life, giving a personal form to his wide-ranging interests in the medieval history and literature of Spain and Portugal, as well as his fascination with dreams and alter-egos (Speck, Contexts 203-217). Southey taking the name “Montesinos” might be twinning himself with (already self-twinned) Blanco White—in knowing Spain, Portugal, and Catholicism from the inside out. But the pairing of this anti-Catholic figure—“no more […] a pupil of the Jesuits” (STM 364)—with the near-sainted Sir Thomas More, suggests what Southey in one of his recurring “Catholic” dreams called a certain “staggering” of his “Protestantism” (qtd. Speck, Contexts 214). The apparently “English” perspective of the Colloquies is peppered with repeated references—usually in the voice of “Montesinos”—to the history and the constitution of the Society of Jesus, and to their “most imperfect of Utopias” in the Paraguay Reductions (STM 62, 79, 123, 147-148, 200, 208, 224, 318-319, 333, 344-345, 347). The only real textual crux in the Colloquies occurs—perhaps significantly—at the moment when Montesinos implicitly denies belonging to the Society (STM 364-365).[4] Southey’s contemporaries lacked the access to his dream-book—full of “living monuments” of saints, architectural visions of hell, and invocations of “Jesus and St. Ignatius Loyola!”—that might have made Colloquies legible not only as a Burkean lament for the loss of “old instinctive belief” (STM 2-3), but as a sort of Catholic lucid dream (see Speck, Contexts 213-216; STM 2-3; and reviews in the Westminster and Examiner in STM 708-726, 711, 725). But by the 1820s even friends such as Charles Lamb detected a “noteable inconsistency” in writings that both paraded and debunked the “imposing rites” of “our Popish brethren”: “You pick up pence by showing the hallowed bones, shrine, and crucifix; and you take money a second time by exposing the trick of them afterwards” (qtd. STM 533-536 n. 51).

Possibly reflecting all levels of this “inconsistency,” the apparently abstruse name of “Montesinos” certainly reflects the scholarly and cosmopolitan flavour of Southey’s interests as historian and poet. But it is also shorthand for Southey’s claim to full fellowship among the “Lake Poets,” to being as much a denizen of the visionary mountain republic as Wordsworth or Coleridge—but in his own particular way. These meanings are implicit in Southey’s comment to Rickman, in the midst of work on the unpublished “Second Series” of Colloquies on January 14, 1831, that “The man of the mountains will interpolate his speeches, largely & loquaciously enough when he gets among them” (Huntington MS RS567; my transcription).

The obvious literary source is the “Cave of Montesinos” episode (in chapters 22-23) in Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote (1605). Southey owned three editions of the Quixote, two of which date from the early seventeenth century and are rare or (translated) first editions.[5] In 1807, Southey had discussions with Longmans about re-editing the “old edition” with Thomas Shelton’s translation (CLRS 1354 and 1356). This project came to nothing, but Southey would have been aware of other contemporary editions, including John Gibson Lockhart’s 1822 edition using Motteux’s “spirited” rather than Shelton’s “obsolete” translation—which Lockhart took over from Walter Scott, as Southey had done with his 1817 edition of the Morte D’Arthur (see Lang 307-308).

In Don Quixote, old man Montesinos appears to the hero in his dream in the cave, and leads him into a crystal palace, where he confirms the ballad legend that he cut out the heart of his dying friend, Durandarte, and delivered it to his friend’s mistress, Belerma. Montesinos further relates that he and his companions are “kept here enchanted by Merlin that British magician, who, they say, was the son of the Devil … how and for what cause no man can tell” (Lockhart ed. IV 71-74). Various companions, meanwhile, have undergone metamorphoses: “Ruydera (the lady’s woman) with her seven daughters, her two nieces … were turned into so many lakes … [Durandarte’s] squire Guadiana … was in like manner metamorphosed into a river.” In a passage rich with resonances for Southey, Montesinos expands on the fate of Gaudiana: “Those lakes mixing their waters in his bosom, he swells, and glides along in sullen state to Portugal, often expressing his deep melancholy by the muddy and turbid colour of his streams” (Lockhart ed. IV 75-76).

But this literary source for Southey’s alter ego was already a composite point of reference. The entry for “Montesinos” in William Wheeler’s Dictionary of the Noted Names of Fiction (1866)—which draws on John Gibson Lockhart’s annotations—defines the name thus:

Montesinos. Sp., from montesino, bred or found in a forest or mountain, from monte, mountain, forest. A legendary hero whose history and adventures are described in the ballads and romances of chivalry. Having received some cause of offence at the French court, he is said to have retired into Spain, where, from his fondness for wild and mountainous scenery, he acquired the name by which he became so celebrated, and which has been given to a cavern in the heart of La Mancha, supposed to have been inhabited by him. This cavern has been immortalized by Cervantes in his account of the visit of Don Quixote to the Cave of Montesinos.

248; see also Lockhart ed.,IV 298-302

Southey would have been well aware of the complex literary legend behind the Montesinos episode in Don Quixote, having immersed himself in old Spanish ballads and romances for Hispanist works including Amadis of Gaul (1803), Palmerin of England (1807), the Chronicle of the Cid (1808), and Roderick, the Last of the Goths (1814). The name Montesinos thus links the Colloquies into a Cervantic and larger “Romantic” literary tradition. But it is also from the beginning—in Lockhart’s telling, at least—less a name denoting true identity than a Spanish mask adopted in retreat, a name applied to a “legendary hero” who haunts “wild and mountainous scenery” after “retiring” from the public affairs of France. The legend resonates with Southey’s own career: The birth of his public conservative persona coincided with the inception of the Quarterly Review, in reaction to the notorious claim of the Edinburgh that the 1808 Iberian uprising against Napoleon—and British sympathy with it—was the risen (and righteous) ghost of 1789 (see ER 13 [1808] 222-223; CLRS 1596).

Montesinos the Carolingian knight is a significant figure in the Romancero General, and he was well represented in English translations of Spanish ballad literature. Montesinos is the focus of three ballads in Thomas Rodd’s Ancient Ballads from the Civil Wars of Granada, and the Twelve Peers of France (1801), of eight ballads included in Rodd’s subsequent History of Charles the Great and Orlando, and Other Spanish Ballads (1812), and of his 1821 Ancient Spanish Ballads, Relating to the Twelve Peers of France, Mentioned in Don Quixote, with English Metrical Versions. Southey thanked John Murray for a copy of Rodd’s 1812 collection in February 1812, noting that “[i]t will furnish a very amusing article” for the Quarterly (CLRS 2039). Among the eight ballads featuring Montesinos in the Rodd collections are “Count Grimwald and Montesinos,” “Montesinos and Oliveros,” and the four-part “Ancient Ballad of Montesinos &c.,” featuring Durandarte and Belerma. Montesinos is also the focus of “Durandarte and Belerma,” translated by Matthew “Monk” Lewis, and included in his popular and controversial Gothic novel The Monk (1796) as Matilda’s seduction song (Lewis 59-61). Tasked by his dying friend Durandarte to cut out his heart and deliver it to his “scornful” mistress Belerma, Montesinos ends the poem lamenting his own fate to live with his soul in the ground:

Sad was Montesinos’ heart, He

Felt distress his bosom rend.—

“Oh! my Cousin Durandarte,

Woe is me to view thy end!

“Sweet in manners, fair in favour,

Mild in temper, fierce in fight,

Warrior, nobler, gentler, braver,

Never shall behold the light!

“Cousin, Lo! my tears bedew thee!

How shall I thy loss survive!

Durandarte, He who slew thee,

Wherefore left He me alive?”

The name Montesinos thus represents a compound literary allusion, to Cervantes and the ballad tradition behind him—analogous to Thomas Percy’s presentation of Shakespeare as the heir of ancient English “song-enditers”—and to the traditionary element within the modern literary phenomenon of the Gothic novel.

But the name was also a watchword, revealing—to the initiated—further layers of historical knowledge and imaginative identification. Rickman’s remark on a “Spanish name (title)” being none the “worse for being understood by few” came in the context of his and Southey’s (ultimately abortive) plans for a second series of Colloquies in 1830-1. The importance that both men gave to names is reflected in the fact that eight of the thirteen letters on the “New Colloquies” between January and mid-February 1831 contain discussions and reports of research on the subject. Candidates for Rickman’s name include: Manrique, Instantius, Vigilantius, Camarero, Cameraries, Severitus, Camaristo, Contador, Pesador, Cotejador, and—Rickman’s eventual choice, an allusion to his motto, “moderation is best”—Metretes (Huntington MSS RS561-574; RLL 281). Southey’s letter to Rickman of February 3, 1831 reveals the amount of attention given to something he affected to treat as incidental: “I speak of you first as my host Manrique & address you afterwards by the name of Camaristo—which may just as well be a surname in Spanish as Chamberlain is in English. It means a little too much, & Camarero means something too little, this however is of no importance” (Huntington MS RS571; my transcription). Southey seems to have felt that this just gradation of meaning was already fully achieved in “Montesinos”: not once in this discussion did he consider a new name for himself.

The name Montesinos, then, evokes a number of other historical figures, all of whom Southey—as poet and “better historian”—knew from his work on Spanish and Portuguese history and culture, South-American colonies, and the Jesuits. The name “Montesino” or “Montesinos” is common to:

Fray Antonio Montesino (c.1475-c.1540), a Dominican friar and associate of Bartolomé de las Casas, who in 1511 preached against tyrannical Spanish laws and practices in the Americas;

Fray Francisco Montesinos (dates unknown), the Dominican Provincial of Maracapana who in 1561 raised the alarm about the “mutiny” and crimes of the great mad, bad man, Lope de Aguirre (1510-1561) in Isla Margarita;

Fray Ambrosio Montesino (1444-1514, aka de Montesinos), a leading figure in the Franciscan renewal in Spain, whose Spanish translation of the Carthusian Ludolphus of Saxony’s fourteenth-century Vita Christi Cartuxano, a feudalized version of the Gospel story, launched the printing press at Alcala de Henares in 1502-3, and later inspired Ignatius de Loyola;

Antonio de Montesinos (or Montezinos, a.k.a. Aharon Levi, dates unknown), a seventeenth-century Portuguese traveller who claimed, as Menasseh Ben Israel (1604-1657) noted in The Hope of Israel (trans. 1650), to have found the “lost Ten Tribes of Israel” living behind the Andean cordillera.[6]

There is not space in this essay to provide the full detail of Southey’s knowledge of and interest in each of these “Montesinos” figures. The detail may be found in Appendix B of the new Routledge edition of Colloquies (see STM 843-858). But it would be only a slight oversimplification to say that each of these “Montesinos” figures was the subject of a thumbnail biography by Southey—albeit of a progressively more oblique or “ghostly” character. Southey almost certainly provided the sources (if not the text) of the section on Antonio Montesino in his brother Thomas Southey’s Chronological History of the West Indies (1827)—having probably been drawn to this figure by his similarity of his story to that of the Jesuit missionary in Brazil, Antonio Vieira (1608-1697), as recounted in the History of Brazil, volume two (see STM 847-851). Southey also wrote the story of Fray Francisco—“the Provincial”—in his 1821 publication (building on material a decade old from the Edinburgh Annual Register), The Expedition of Orsua: And the Crimes of Aguirre, where it occupies some ten or so pages of the text. For a significant portion of the narrative, this Montesinos is Aguirre’s only credible antagonist (see STM 851-852). In 1807, Southey had provided brief biographical entries for John Aikin’s General Biography on two figures closely associated in literary history with the Franciscan Fray Ambrosio de Montesinos: the precursor, Íñigo López de Mendoza (1398-1458), and the contemporary, D. Jorge Manrique (c.1440-1479). Southey subsequently suggested “Manrique” as a name for Rickman in the “New Colloquies” specifically because it would be in “Spanish”—and “litera[ry]”—“keeping” with “Montesinos” (see STM 852-855). The ultra-utopian spirit of Antonio de Montezinos, meanwhile, is implicated in Southey’s comments in the History of Brazil, volume three, about The Hope ofIsrael being “one of the most groundless treatises that ever was composed in the spirit of credulity” (STM 855-856; and see HoB III 722-723).

So, Montesinos: religious poet, humanitarian lawmaker, “Provincial” opponent of colonial state-terrorism, and quasi-mythical utopian-cum-forger. This (un)familiar compound ghost, both intimate and unidentifiable, resonates with Southey’s own multi-layered historical identity, as Pantisocrat-turned-Poet-Laureate, “semi-Socinian” bulwark of the Anglican Establishment, and anti-Catholic Royal Spanish Academician historian of the Jesuits. Montesinos is Southey the modern English “entire man of letters” translated back onto a medieval Spanish palimpsest. The various identities of “Montesinos” may be taken together as a sort of “suspended reading,” in Stephen Greenblatt’s phrase (5), of Southey and his career. All four men named Montesinos are also John the Baptist figures, precursors eclipsed by more illustrious or notorious men: Antonio Montesino by Las Casas, Francisco Montesinos by Aguirre, Ambrosio Montesino by Ignatius Loyola, and Aharon Levi Montesinos by Ben Israel—and also by the earlier figure of Thomas More.

This compound meaning of “Montesinos” as harbinger of the master is clearly suggestive for Southey’s sense of his own role in the literary triumvirate of the Lake Poets, or men of the mountains. As Tim Fulford has shown in the context of the Colloquies, Southey in the later phase of his career effectively reinvented himself as a public spokesperson for Wordsworth and a “Lake Poet” ethos (Fulford 2013 29-68). The literal meaning of “Montesinos” as “man of the mountains” opens up further levels of possible allusion, however, and a potentially more subversive and conflicted sense of what such ideological projection might actually entail.

The name Montesinos—“which is,” the Monthly Review noted, “being interpreted, ‘Old Man of the Mountains’”—further encodes Southey’s reputation (discussed already at §9) as an extremist. “Methinks I want nothing but craziness to set up for a prophet,” Southey told Rickman on February 9, 1829 (Selections IV 128-129). In France in 1792-4, the “Montagnards,” seated in the highest benches of the National Assembly, were Robespierre’s party of regicide and terror. The name “Old Man of the Mountain” is also associated with the late-twelfth century Syrian figure Rashid Al-Din Sinan, and crusades-era myths of his “hashishim” or assassins carrying out political murders in return for paradise. Southey drew upon and dramatized this myth in Book VII of Thalaba (1801), in which the Islamic hero destroys the false paradise of the sorcerer Aloadin. In Thalaba, Southey supplies a lengthy note on this “old man named. Aloadin,” drawing on sources including Samuel Purchas, Purchashis Pilgrimage (1614), and the “undaunted liar Sir John Maundevile,” whose Voiage and Travaile (London, 1727) describes the “Paradys” by a “Castelle […] in a mountayne” in “the Lond of Prestre John” (EPW III 108-111, 259-261). The episode in Thalaba is closely associated with Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” (pub. 1816), which closes on an inward transformation occurring somewhere between England, Abyssinia, and the Orient, on “Mount Abora,” “holy dread,” and “Paradise.” In The Book of the Church (1824), Southey describes the fanatical and disciplined Jesuits as a tool in the hands of “[t]he Popes, at that time,” with young men of the right “temper” “ordered” to martyrdom in Japan, or doing the bidding of “their Old Man of the Mountain” by going to England to attempt the assassination of Elizabeth I, Queen of what “they called the European Japan” (II 276).

At the level of the work as a whole, these undercurrents in the name “Montesinos” may serve the dramatic purpose of subtly subverting his view, usually “upon the hopeful side” (STM 390); much as the recurrent echoes of Hamlet work on the other side to call in question the “goodness” of Thomas More’s pessimistic Ghost. Southey’s allusive self-identification with Aloadin certainly reflects the preoccupation of Colloquies as a whole with superstition, millenarianism, and with a “prospective” view of what Montesinos in Colloquy X calls the “renewed” social “danger”—linking the Reformation and the French Revolution—from “political insanity” and “religious fanaticism” (STM 190-191). “[T]he triumph of democratical fanaticism” in the French Revolution was, says Montesinos, the “counterpart of the Munster Tragedy, Marat and Hebert and Robespierre being the Johns of Leyden and the Knipperdollins of democracy” (STM 191). Britain is in imminent danger from this “plague,” Montesinos thinks—but the USA is next:

The government not thinking it necessary to provide religious instruction for the people in any of the new states, the prevalence of superstition, and that, perhaps, in some wild and terrible shape, may be looked for as one likely consequence of this great and portentous omission. An Old Man of the Mountain might find dupes and followers as readily as the All-friend Jemima; and the next Aaron Burr who seeks to carve a kingdom for himself out of the overgrown territories of the Union, may discover that fanaticism is the most effective weapon with which ambition can arm itself …

STM 191

The allusions are to Jemima Wilkinson (1752-1819), the charismatic American evangelist and preacher of total sexual abstinence, and to Aaron Burr Jr. (1756-1836), the third Vice President of the USA, who became involved in a conspiracy to found a dynasty in Mexico after the duel that ended his career—and the life of Alexander Hamilton (1755/7-1804). These comments were later seen, in the words of pencil notes on a family copy of the Colloquies, as not only properly historic—“+ Horace Walpole has a similar predication uttered in 1792”—but as strangely “prophetic”: “This has come to pass already”; “Mormonites” (STM 623-244 n. 427, n. 428; see also item BL6B3 in the Boult collection at Bristol Reference Library). The words of Montesinos were indeed reprinted in 1843 as the epigraph to a book by Henry Caswall on The Prophet of the Nineteenth Century; or, the Rise, Progress, and Present State of the Mormons, or Latter-day Saints. Echoing Southey’s “peculiar titles”—including his 1817 Quarterly essay on “The Rise and Progress of Popular Disaffection,” with its “devious” or “Coleridgean” implied reversal of “progressivist historical assumptions” (see Gilmartin, 238)—Caswall suggests a genuine power of prophecy in Southey’s book. Caswall’s preface “solicits” “[t]he reader’s attention” to:

a remarkable extract from Southey (inserted opposite the title page), which did not meet the Author’s eye until the greater part of this work was in print. The prediction was published in March, 1829, fourteen months previously to the publication [during the “pretended translation”] of the Book of Mormon ...

Caswall xiii–xiv

In 1838, the Mormon “apostate” Thomas Marsh invoked the same “somewhat singular” passage in Colloquies against its supposed prophetic subject, the Mormon founder Joseph Smith: “A prediction as early fulfilled as this was would have made Joseph a great Prophet” (Jeter §5). It was perhaps appropriate, however, that Marsh also misattributed the prophecy. It came from “Robert Southey, the Poet Laureate of England,” Marsh noted, and out of “the mouth of Sir Thomas More.” And thus once more Montesinos slips from self-identity, as reoriginating man of the mountains—and is gone.

III. Coda. The “new literary biography”: emblem and alchemy

In his account of the “new” “Romantic biography,” Nicholas Roe describes the biographer’s “hard task of speculative revival” (206-207). The background allusion is to Wordsworth’s school of soul-reading in ThePrelude (1805):

II 232-237Hard task to analyse a soul, in which,

Not only general habits and desires,

But each most obvious and particular thought,

Not in a mystical and idle sense,

But in the words of reason deeply weighed,

Hath no beginning.

The “Romantic biographer” works with “archives, notebooks, letters,” but “similar” to the “new historicist” critic in most imaginative mood, s/he is attempting rightly to read textual absence: to feel at once the “human limits” of contexts, the circulating “energies of language,” and the invisible “shapes of imagination transmuting into poetry” (206-207). For Jerome McGann, to “maintai[n] the poem … in the artificially restricted geography of the individual person,” as traditional “biographical criticism” has tended to do, is to remain arrested at the level of “antiquarian humour” rather than history; “pleased,” in the words of the Wanderer in what Tom Clucas calls Wordsworth’s book of “parallel lives,” The Excursion (1814), “To skim along the surfaces of things.” To read this way, for McGann, is to stumble upon “literary” truths of ever-increasing size, even as criticism “falters” and dwindles in the historical analysis (48-49). Roe, on the other hand—content to recognize that there is a viewer and a frame, and daring to hope that “articulate redress” may accrue to the artist framed within it—envisages the literary-biographical “stumble” as at least a faltering forward. If the re-creative “inwardness” of such literary biography is “disquieting,” in Roe’s phrase, this may be because it is not really “deep” or “inward” at all. Returned from the bourne beyond “the artificially restricted geography of the individual,” such biography has instead become “ecological.” Or, to use the term that both Roe and Ann Wroe use to frame their new biographies of Shelley and Keats, it has become “elemental”: “This is biography as alchemy” (Roe 206-207).

Roe has in mind primarily the way that figures such as Keats and Hunt respond to the techniques of “Romantic Biography.” But he intimates that “[e]ven the Keswick renegado, Robert Southey,” now “returned to print” (203), may also look different in this perspective. The self-multiplying author of Sir Thomas More might, indeed, begin to seem a precursor of the “Romantic biographer.” Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch’s Robert Southey (1977) opens with a re-statement of the critical consensus about the laureate’s shortcomings as an autobiographical Romantic poet. Although he lived “in an age of great autobiography—and, indeed, seems to have coined the word,”

he left no distinct specimen of the genre. The fact is symptomatic: Southey was incapable of introspection. He could either recall reality in its surface minutiae or reduce it to poetic schemata of myth and allegory; but he could not alchemize personal fact into autonomous image and symbol.

13

The criticism remains just. Southey was, as contemporaries charged, and this essay has further suggested, a writer of “minutiae” and “schemata” at once. But the complaint of a failure to “alchemize personal fact” misses what I have tried to suggest, and what Roe’s comments might help to imagine, is precisely the historical disclosure—the “biography as alchemy”—involved. The compression of meaning into a single word or name was, as I have argued, a key part of Southey’s “exoskeletal” or emblematic approach to complexity. The name “Montesinos” operates as a “hieroglyphic” sign or shape for the historical “question” of “character”—of what “corresponds” and what “distinguishes” in and between persons, cultures, and countries across time. And the way that this question is precisely confused in the critical moment of the ghost’s entrance—saying “Montesinos, a stranger from a distant country”—is perhaps the whole point.

The “Introduction” featuring this moment was substantially complete by early 1820 (see CLRS 3429). By the time the book was published and reviewed at the end of the decade, Southey seems to have lost sight of the ambiguity of his own language on the “stranger from a distant country,” and the uncertainty of the association between “Montesinos” and himself. He complained, as noted previously (see §3), about critics missing the allusion to Hamlet and taking the phrase as an explanation of the foreign name, “Montesinos.” Nor was the misreading by the Literary Gazette just a simple mistake. It represented a challenge to the boundaries between reading audiences, bypassing the watchword function of the “name … understood by few.” The Gazette may indeed have revealed a lack of knowledge and of critical acumen as it reached to resolve the ambiguity too soon, imagining a second comma after “country,” and forcing upon the text the bizarre idea that the stranger who calls speaks first—and with his own name. But air-drawn signs and wrong first-speakers are, after all, also features straight from Shakespeare. And what is true of “Utopia” and the widening meaning “understood by thousands” is no less true of Hamlet or Macbeth. The common “English” critic fitting “Montesinos” directly into the Shakespearean ambiance of “The Introduction” may thus have been reading better—or with a more “depthless” acuity—than Southey himself now knew or could wish. The “mistake” might be understood alternatively as a moment of historical parapraxis: a re-linking of the densely intertextual “sign” of “Montesinos”, with all its accumulated “counterfactual” heft—its power of “[g]hosting the ‘factual’” (Davies 11)—back to Southey’s own “eco-historical” vision of England in 1817.’ “Montesinos” signifies utopian possibilities abroad. And at home, it whispers of absence and of what may yet rise—transplanted back “From America,” or from Portugal and Spain—within a “national” tradition accomplished, yet sparsely living; a susurration of the ghost soil.

Et in Utopia ego.

Appendices

Biographical note

Tom Duggett is Associate Professor in Romantic and Victorian Literature at Xi’an Jiaotong—Liverpool University (XJTLU, the University of Liverpool in China). He is the author of a study of Wordsworth’s poetry and politics, Gothic Romanticism: Architecture, Politics, and Literary Form (Palgrave 2010). His work as a scholarly editor includes a 2018 Pickering Masters edition of Robert Southey’s Sir Thomas More: or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society (1829), and a forthcoming edition of Southey’s 1824 Book of the Church (also for Routledge, 2020). Duggett is contributing to a number of edited books forthcoming in 2018/19, including the Oxford Handbook of Victorian Medievalism, Gothic and the Arts, and the Cambridge History of the Gothic. He is currently writing a book on Romantic poets as historians.

Notes

-

[1]

See also Fulford 2016 156-173; and see Gravil 2003 25-45. On the “rise” of “English eerie,” see Macfarlane, “The eeriness of the English countryside” (2015). “English eerie” combines “hauntology, geological sentience and political activism” to “explore the English landscape in terms of its anomalies rather than its continuities,” unearthing the terrifying “something” “seething” beneath the pastoral prospect. “Ghost soil” is a coinage of the William Morris disciple and #Hookland creator David Southwell, suggesting the repressed historical guilt as well as the re-enchantment and resistance that lurk in the countryside (Fortean Times, 1 June 2017).

-

[2]

The Poet binds together “the vast empire of human society, as it is spread over the whole earth, and over all time,” and embodies “passion and knowledge” in poetry that “is the history or science of feelings.” See Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1800) in Prose Works I 167; and the “Note to The Thorn,” in The Major Works 594.

-

[3]

See D’Arcy Wood 2017 3-6. For the coalescing “ecological thought” in Southey’s letters, see in particular: from November 1817 on the idea of Boethian “threnodial” dialogue, CLRS 3040 and 3042 (and from early 1820 on “climacterics,” CLRS 3429 and 3432); and from December 1817 on “unnatural weather” and “A Volcano,” CLRS 3044, 3052, 3055, 3056, and 3059.

-

[4]

The crux is the Burkean/Carlylean question of whether “Montesinos” has “habits” [1831] or “no habits” [1829] that he “cannot lay aside as easily as [his] clothes” (see STM 365).

-

[5]

These editions include: volume one of a rare Milan edition of 1610-15; a two-volume first edition of Thomas Shelton’s English translation (1612-20); and a nine-volume edition published at Madrid in 1798 (item no. 3191). See items 3190, 641, 3191 in the sale catalogue of Southey’s library (see STM 859-87).

-

[6]

My list is selective and specific to Southey. For other figures with the name, see Schorsch 2009, 394-397.

Bibliography

- Aikin, John, editor. General Biography, or, Lives, critical and historical of the most eminent persons of all ages, countries, conditions, and professions. 10 vols., London: J. Johnson, 1799-1815.

- Bernhardt-Kabisch, Ernest. Robert Southey. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1977.

- Burke, Edmund. Reflections on the Revolution in France. Edited by J.G.A. Pocock, Cambridge and Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987.

- Carnall, Geoffrey. Robert Southey. London: Longman Group, 1971.

- Caswall, Henry. The Prophet of the Nineteenth Century; or, the Rise, Progress, and Present State of the Mormons, or Latter-day Saints. London: Rivington, 1843.

- Cervantes, Miguel de. The History of the Ingenious Gentleman, Don Quixote of La Mancha. Translated by Peter Motteux, edited by John Gibson Lockhart, 5 vols., Edinburgh: A. Constable and Co., 1822.

- Chandler, David. “‘As Long-Winded as Possible’: Southey, Coleridge, and The Doctor &c.” The Review of English Studies, vol. 60, no. 246, 2009, pp. 605–619.

- Claeys, Gregory. Citizens and Saints: Politics and Anti-Politics in Early British Socialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- Clucas, Tom. “Plutarch’s Parallel Lives in The Excursion.” The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 45, no. 2, Spring 2014, pp. 126-130.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Table Talk. Edited by Carl Woodring, 2 vols., Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. (TT).

- D’Arcy Wood, Gillen. “Eco-historicism.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, vol. 8, no.2, Fall/Winter 2008, pp. 1-7.

- D’Arcy Wood, Gillen. “Frankenstein, the Baroness, and the Climate Refugees of 1816.” The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 48, no. 1, Winter 2017, pp. 3-6.

- Davies, Damian Walford. ‘Introduction: Reflections on an Orthodoxy’. Romanticism, History, Historicism: Essays on an Orthodoxy, edited by Damian Walford Davies, New York and London: Routledge, 2009, pp. 1-13.

- Davis, Robert, and Frank O’Hagan. Robert Owen. London: Bloomsbury, 2010.

- Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx. New York and London: Routledge, 1994.

- Eliot, T. S. Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot. Edited by Frank Kermode, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

- Fulford, Tim. “Virtual Topography: Poets, Painters, Publishers and the Reproduction of the Landscape in the Early Nineteenth Century.” Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, no. 57-58, February–May 2010, , https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ravon/2010-n57-58-ravon1824552/1006512ar/.

- Fulford, Tim. The Late Poetry of the Lake Poets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Fulford, Tim. “Strange Meetings: the Romantic Poets and the Stone Circles of the Lake District.” The Harp and the Constitution: Myths of Celtic and Gothic Origin, edited by Joanne Parker, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2016, pp. 156–173.

- Gilmartin, Kevin. Writing Against Revolution: Literary Conservatism in Britain, 1790-1832. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Goodhart, David. The Road to Somewhere. London: Hurst, 2017.

- Gravil, Richard. Wordsworth’s Bardic Vocation, 1787-1842. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. Hamlet in Purgatory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Hazlitt, William. The Selected Writings of William Hazlitt. Edited by Duncan Wu, 9 vols., London: Pickering and Chatto, 1998. (SWWH).

- Hazlitt, William, and William Hone. “Two Reviews of Robert Southey’s Wat Tyler.” Edited by Matt Hill, Romantic Circles, 2004, https://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/wattyler/contexts/reviews.html. (“Two Reviews”).

- Jeter, Edje. “The Mormon Old Man of the Mountain.” The Juvenile Instructor, 19 December 2014, http://juvenileinstructor.org/the-mormon-old-man-of-the-mountain/-_edn4.

- Lang, Andrew. The Life and Letters of John Gibson Lockhart. 2 vols., London: John C. Nimmo, 1897.

- Lewis, Matthew. The Monk. Edited by Nick Groom, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Macfarlane, Robert. “The eeriness of the English countryside.” The Guardian, 10 April 2015, www.theguardian.com/books/2015/apr/10/eeriness-english-countryside-robert-macfarlane.

- Madden, Lionel, editor. Robert Southey, The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge, 1972. (RSCH).

- Marginalia in Southey family copy of Sir Thomas More: or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society. 2nd ed, London: John Murray, 1831; Boult Collection at Bristol Reference Library, item no. BL6B3.

- McGann, Jerome J. The Beauty of Inflections: Literary Investigations in Historical Method and Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- Méchoulan, Henry, and Gérard Nahon, editors. Menasseh Ben Israel, The Hope of Israel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Memorias de Litteratura Portugueza, pela Academia Real das Sciencas de Lisboa. 8 vols., Lisbon: Royal Academy of Sciences of Lisbon, 1792-6.

- Morgan, John Minter. Hampden in the Nineteenth Century: or,Colloquies on the Errors and Improvement of Society. London: Moxon, 1834.

- Morton, Timothy. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- MSS correspondence of Robert Southey and John Rickman in the Rickman-Southey Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino; Box 7, Jan 1828-March 1831. (Huntington MS).

- Neher, André. Jewish Thought and the Scientific Revolution of the Sixteenth Century. Translated by David Maisel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986 [1st ed. 1974].

- Perry, Seamus. “Self Management.” London Review of Books, vol. 28, no. 2, 26 January 2006, pp. 18-21.

- Pratt, Lynda, editor. Robert Southey and the Contexts of English Romanticism. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. (Contexts).

- Roe, Nicholas. “Leigh Hunt and Romantic Biography.” Romanticism, History, Historicism: Essays on an Orthodoxy, edited by Damian Walford Davies, New York and London: Routledge, 2009, pp. 203-220.

- Schorsch, Jonathan. Swimming the Christian Atlantic. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2009.

- Southey, Robert. Robert Southey: Poetical Works 1793–1810. General editors Lynda Pratt, Tim Fulford, and Daniel Sanjiv Roberts, 5 vols., London: Pickering & Chatto, 2004. (EPW).

- Southey, Robert. Letters Written During a Short Residence in Spain and Portugal. Bristol: Joseph Cottle, 1797.

- Southey, Robert. Letters from England by Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella. Edited by Carol Bolton, London and New York: Routledge, 2016. (LFE).

- Southey, Robert. History of Brazil. 3 vols., London: Longman, 1810–19. (HoB).

- Southey, Robert. Journal of a Tour in Scotland in 1819. Edited by Charles Harold Herford, London: John Murray, 1929.

- Southey, Robert. The Expedition of Orsua: And the Crimes of Aguirre. London: John Murray, 1821.

- Southey, Robert. The Book of the Church. 2 vols., London: John Murray, 1824.

- Southey, Robert. Selections from the Letters of Robert Southey. Edited by John Wood Warter, 4 vols., London: Longmans, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1856. (Selections).

- Southey, Robert. Sir Thomas More: or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society. Edited by Tom Duggett, 2 vols., London and New York: Routledge, 2018. (STM).

- Southey, Robert. The Collected Letters of Robert Southey, A Romantic Circles Electronic Edition. General editors Lynda Pratt, Tim Fulford, and Ian Packer, University of Maryland: Romantic Circles Electronic Editions, 2009-, http://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/southey_letters. (CLRS).

- Southey, Robert and Caroline Bowles. The Correspondence of Robert Southey with Caroline Bowles. Edited by Edward Dowden. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1881. (CRSCB).

- Southey, Thomas. Chronological History of the West Indies. 3 vols., London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1827.

- Storey, Mark. Robert Southey: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Warren, Andrew. The Orient and the Young Romantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Wheeler, William. Dictionary of the Noted Names of Fiction. London: Bell and Daldy, 1866.

- White, Joseph Blanco. Letters from Spain, by Don Leucadio Doblado. 2nd ed., London: Henry Colburn, 1825.

- Williams, Orlo. Lamb’s Friend the Census-Taker; Life and Letters of John Rickman. London: Constable, 1911. (RLL).

- Wordsworth, William. The Prelude: The Four Texts (1798, 1799, 1805, 1850). Edited by Jonathan Wordsworth, London: Penguin, 1995.

- Wordsworth, William. The Prose Works of William Wordsworth. Edited by W. J. B. Owen and Jane Worthington Smyser, 3 vols., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974. (WPW).

- Wordsworth, William. William Wordsworth: The Major Works. Edited by Stephen Gill, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Wu, Duncan. Romanticism, An Anthology. 4th edition, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Edinburgh Review (ER)

Quarterly Review (QR)

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

10.7202/1006512ar

10.7202/1006512ar