Résumés

Abstract

This essay explores the television productions of Ernie Kovacs and Charles and Ray Eames, analyzing their pioneering audio-visual experiments in the American network broadcast system of the mid-century period. It examines how their work with TV graphics, montage, collage, sound, video tricks and special effects relates to Jean Christophe Averty’s work in French TV in the same period. It explores the “experimental spirit” across the Atlantic before the rise of video art per se, demonstrating how all of these early TV artists challenged dominant conceptions of what TV should be in their respective national and industrial contexts. Finally, it calls for more historical research on and theoretical inquiry into the complex relationships between art, design and commercial TV at mid-century.

Résumé

Cet article analyse les productions télévisuelles d’Ernie Kovacs et du couple Eames (Charles et Ray) au sein du réseau de télédiffusion américain des années 1950, en examinant comment leur façon d’utiliser le graphisme, le montage, le collage, le son, les trucages et autres effets spéciaux se rapproche de ce que faisait Jean-Christophe Averty à la télévision française à la même époque. L’auteure y explore « l’esprit d’expérimentation » qui a prévalu des deux côtés de l’Atlantique avant la naissance de l’art vidéo en tant que tel, et montre de quelle manière ces artistes pionniers de la télévision ont remis en question les conceptions dominantes de ce que devait être le nouveau média dans leurs contextes nationaux et industriels respectifs. Elle conclut sur la nécessité d’étudier dans une perspective historique et théorique les relations complexes qu’entretenaient les arts, le design et la télévision commerciale au milieu du siècle dernier.

Corps de l’article

When the editors of this special issue asked me to situate Jean-Christophe Averty in the context of his U.S. contemporaries, I began to see a striking set of similarities between his early French programs and the work of artists and designers employed by U.S. broadcast networks in the 1950s and 60s. These broad similarities—the use of graphic design, typography, montage, collage, rapid editing, animation, superimpositions and other video effects—along with a catholic mix of high and low (for example, a combination of popular TV comedy with strains of Surrealism, Dada and the absurd) opens up intriguing questions about broadcast television as an international art practice before the proliferation of video art per se.

This essay focuses on mid-century U.S. TV artists, offering a context in which to see Averty’s television productions alongside artistic experiments across the Atlantic. Although I have no evidence that Averty worked or corresponded with the artists I discuss, he did have first-hand knowledge of the American film and television industries. In 1961 he spent six months at the Disney Studios and at the ABC television network.[1] He was also acquainted with American jazz and blues artists, whom he featured in jazz programs for French television, which he began to direct in the 1950s.

Known for his graphic artistry (he was awarded the “Prix des Graphistes”; see Blanchard 1969, p. 59), Averty experimented with various combinations of TV graphics, collage, montage, special effects, colour, animation and live action (Duguet 1996, p. 98). His distinctive approach was first fully realized in his 1963-64 series Les raisins verts, for which he received international recognition (for example, the U.S. Academy of Television Arts and Sciences honoured the series with an Emmy Award).[2] Throughout the 1960s he made innovative use of early video technologies, becoming famous for treating the video screen as a “page” for graphic design. He shot actors against blue screen backdrops overlaid with graphics so that, for example, it appeared as if characters were popping out of graphic designs. He joined this graphic approach with a proto-Dada sensibility drawn from Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu roi, which Averty adapted for television in 1965 (see Duguet 1996).

Here, I explore artists who experimented with U.S. television in its formative period (roughly 1948 through the emergence of video art in the mid-1960s). The rise of television coincided with the rise of new forms of mid-century modernism. As I detail in TV by Design (2009), television quickly became a vibrant work world for artists, especially for graphic designers, architects and animators working in the modern style.[3] The television networks hired some of the most visionary talents in mid-century modern graphic design to direct network graphics for print publicity and on-screen art (including CBS’s William Golden, Georg Olden and Lou Dorfsman, and NBC’s John Graham). Network art departments also commissioned independent artists who created on-screen title art and promotional graphics (including Ben Shahn, Saul Bass, Richard Avedon, David Stone Martin, Carol Blanchard, Paul Rand, Norman McLaren, and even a young Andy Warhol). Set designers, art directors, video effects engineers and animation companies such as United Productions of America (UPA) also contributed to these new forms of everyday modernism that flickered on TV screens. Much of this cutting-edge television art appeared as interstitials in the television flow (as commercials or title art), but some people working in television did find ways to experiment on a grander scale.

In the following pages, I look at artists whose work in American broadcasting resonates with Averty’s early television programs. First, I consider broadcast pioneer Ernie Kovacs.[4] During his lifetime critics hailed Kovacs as a television “genius,” and in the 1980s (two decades after his death) artists and critics embraced him as the “father” of video art. Second, I explore Charles and Ray Eames, the premier mid-century American design team, whose television work has been almost entirely forgotten. While Kovacs shared Averty’s interests in visual tricks, montage, Surrealism, Dada and the absurd, the Eameses’ productions were more in tune with Averty’s approach to television as a medium for graphic design, animation, collage, fast-paced editing and montage, as well as his proto-computer sensibility in which television was treated as a graphical interface and image archive. Although Averty and his U.S. contemporaries worked in different national television systems and spoke to distinct audience tastes and cultural traditions, all of their work resonated with previous historical avant-gardes while at the same time developing specifically mid-century modern tactics for media art. While their work is in no way the same, I examine corresponding techniques and influences, and mostly a spirit of experimentation through which these artists imagined television outside of its mainstream forms of realism, liveness and fidelity to physical laws of time and space.

Ernie Kovacs: Sound, Reflexivity, Visual Tricks, Montage and the Absurd

In his 1988 essay “Video Art and Television,” John Wyver called attention to the unique bond between Jean-Christophe Averty and Ernie Kovacs, stating:

Two important figures working in television in the 1950s [are] hailed as pioneering visionaries who exploited the full creative range of electronic images. Yet neither Ernie Kovacs, a popular television comedian in the United States, nor the French writer and director Jean-Christophe Averty would have identified their practice as video art. They were both entertainers, interested in reaching a broad popular audience, but both were fascinated by the possibilities of breaking with the conventions and codes of broadcast television

p. 117

Indeed, as the outstanding broadcast innovator of his era, Ernie Kovacs was the most direct American counterpart to Averty. Although he collaborated with directors, musicians, sound artists and performers (such as his wife Edie Adams), Kovacs insisted on absolute oversight of almost all program elements—writing, acting, hosting, producing, art direction, sound, even title art—something no other primetime network performer imagined doing at the time. Like Averty, Kovacs thought about television as a medium rather than just a transmission device for other arts. And like Averty, he created popular TV shows that disrupted the aesthetics of liveness and verisimilitude on mainstream TV. Kovacs shared Averty’s interest in magic (he created the 1957 special Festival of Magic); he experimented with special effects and visual tricks; and he manipulated the television image and its frame. With their mutual love for comics and the absurd, both men had an avid interest in Mad magazine.[5] Despite these broad similarities, Kovacs’s main concerns were not with graphics and collage, but rather with sound-image relations.

An ardent fan of Buster Keaton, Kovacs evoked the physical mayhem of the silent clowns, yet he did so while experimenting with the aesthetic demands and peculiar constraints of television’s audio-visual form. As he told the New York Times in 1961, “Eighty percent of what I do is sight gags. I work on the incongruity of sight against sound.”[6] Whereas most television programs used music and sound effects to enhance realism, punctuate jokes and make action legible for audiences, Kovacs specialized in anti-realist montage symphonies and absurd song and dance routines that used music ranging from the classical compositions of Haydn and Strauss to twentieth-century composers such as Béla Bartók, and he also featured offbeat contemporaries such as Yma Sumac and Juan García Esquivel.

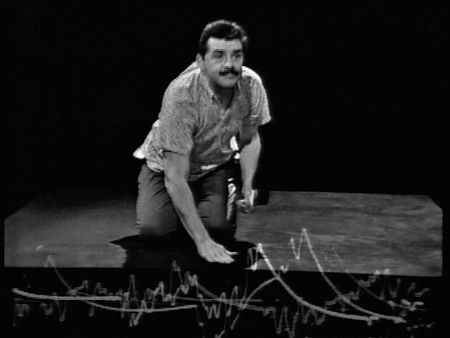

Fig. 1

Kovacs began his television career in 1950 as the host of morning shows on the local Philadelphia station WPTZ. In 1952 he moved to New York, where he hosted local and network programs such as CBS’s morning and daytime show Kovacs Unlimited (1952-53) and NBC’s Tonight Show (which he hosted in 1956). On programs such as these he developed his experimental tool kit, using superimpositions, reverse polarities and scans, black-outs, sight and sound gags (such as talking paintings) and camera tricks (for example, by mounting a juice can and a flashlight on a camera lens he created a kaleidoscope design that filled the screen with dazzling abstract effects). He “tortured” the TV image through camera spins, wipes, fast zooms and other visual distortions. He created mock commercials (an outlet for his antagonism towards sponsors). And he honed his reflexive style. He often broke the fourth wall by, for example, talking to audiences while sitting at the switchers in the studio where he played with the vertical and horizontal controls, demonstrating the techniques by which television technicians created illusions.

Kovacs’s programs were full of absurdist personae and performances, including his much beloved Nairobi Trio. Although it varied across programs, the routine generally featured three actors in gorilla suits and masks, all dressed up in coat-tails and derbies (one was usually Kovacs). Like wind-up toy monkeys that play instruments in perfect synchronization, the Trio plays Robert Maxwell’s “Solfeggio” (a catchy tune named after singing exercises). But, as the song progresses, the Trio’s syncopated movements get off track, and with increasing acrimony the gorillas strike each other with mallets, batons, bananas and the like. The ensuing chaos was not only funny, it also rendered absurd the logic of being “on time” that mechanization—and television performances—demand.

Although Kovacs developed a fan base for his unique style, his early series were short lived. After 1956, his most innovative programs came in the form of network “specials”—a program type that was more conducive to his sensibility and especially his extravagant, time-consuming production routines.

Fig. 2

Rising to popularity in the mid-1950s, television specials broke with the routine flow of everyday TV by showcasing big-name stars, usually in variety shows and dramatic formats, or in adaptations of Broadway musicals. They often served as promotional vehicles for large corporations that poured increasing amounts of capital into them. They also provided a promotional platform for new technologies (such as colour, videotape and chromo-key special effects), and because of this many foregrounded visual experimentation executed by some of the most respected set designers, graphic designers, filmmakers and animators of the time.

Kovacs’s first major statement on sound-image relations came in the form of a thirty-minute special that was broadcast January 19, 1957 on NBC’s Saturday Night Color Carnival.[7] Although NBC aired the program in order to promote its parent company’s (RCA) colour system, Kovacs used the occasion to present a visual thesis on television’s ubiquitous “white noise.” Often referred to as the “Silent Show,” the special contained no dialogue apart from Kovacs’s opening monologue, which he delivered while smoking his signature cigar. The program showcases the Nairobi Trio and songstress Mary Mayo, who sings without words (the effect is a science-fiction-like cross between an operatic human voice and a Theremin). But its centrepiece innovation is its skit (which is really more a visual essay) that features Kovacs as Eugene, a bumbling working-class hero whose noisy antics (rendered paradoxically through pantomime) disrupt the quietude of a posh gentlemen’s club.

Upon entering the club, Eugene surveys items in the room, and Kovacs mines each for its comic potential as noise. When Eugene tries to read Camille, the novel coughs. When Eugene looks at a reproduction of the Mona Lisa, the painting laughs. And when Eugene dials a telephone, the soundtrack plays machine gun noises in lieu of dial tones. In ABC’s 1961 reprise of the same skit, Eugene’s body literally becomes a sound machine as he plugs a tiny record player playing “Mack the Knife” into his stomach, which has an electrical socket on it. By turning sight gags into sound gags, and mismatching sound and image, Kovacs punctures audience expectations for sound fidelity and video realism, exposing television’s audiovisual contrivances.

Fig. 3

The skit’s finale (which Kovacs referred to as the “tilted table bit”) takes this self-reflexive strategy even further. Sitting at a table, Eugene removes items from his lunchbox (olives, milk, etc.) that roll down a slanted table built on an 18-degree angle with the camera positioned on an angle to compensate for the slant. In effect, the table looks perfectly horizontal, but the objects inexplicably roll across it, seeming to disobey the laws of gravity. The soundtrack plays loud incongruous noises. For example, as they roll across the table the olives (accompanied by a drum roll) sound more like bowling balls than food. After considerable noise and frustration (both for him and for the gentlemen at the club), Eugene straightens out the tilted table. But rather than having Eugene physically move the table, Kovacs repositions the camera itself so that it literally reframes the scene, straightening out the table but also tilting the rest of the image. In this way, Kovacs punctures any sense of realism in the skit, revealing the fact that television cameras do not simply “record” real space and action, but rather create spatial illusions and optical tricks.

The “Silent Show” also contained an abstract video composition that Kovacs commissioned from special effects and title artist John Hoppe (who received credit for his Mobilux title effects).[8] The Hoppe piece was created live in camera and was composed of colourful abstract organic and spiralling shapes, which seem to swim across the screen to perky, but increasingly “trippy,” music. The colourful shapes no doubt pleased the NBC/RCA executives with their colour TV agenda, but the Hoppe segment also stands out as one of the first experiments with live in-camera colour abstraction in television, a precursor to the work of Frank Barsyk, who used abstract visuals to accompany live music in his experimental work at Boston’s WGBH in 1964. (Barsyk is often cited in histories of video art, but Hoppe is typically forgotten.)

The “Silent Show” was a huge success. Critics hailed it for reducing TV noise and letting the “TV medium speak for itself.”[9] Honouring its achievement, the U.S. government endorsed the “Silent Show” by choosing it as the only TV program to be screened at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair.

Kovacs further experimented with sound-image relations in videotaped specials he made for ABC between April 1961 and his untimely death in January of 1962.[10] The specials showcased some of Kovacs’s most extravagant innovations, and because they were taped in real time, they were extremely difficult to produce. By the third special, ABC Production Manager Scott Runge wrote a memo stating: “ABC is concerned with the health of their people…. Work hours are much longer than is agreeable to ABC and to state and federal regulations.”[11] But for Kovacs, the specials were a major success as critics elevated him to television’s quintessential modern artist.[12]

The specials featured video montages that juxtaposed images incongruously against one another and alongside equally counterintuitive musical tracks. The first special offered a rapid-fire montage orchestrated contrapuntally against Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture (which, perhaps not coincidentally, was itself composed of musical fragments of hymns, folk songs, bells and cannons, and passages of Tchaikovsky’s invention). The montage opens with an obese ballerina dancing (to the point of exhaustion) from the back of the stage and up towards the camera. It cuts to a quick succession of incongruous objects shot in extreme close-up—toy mechanical monkeys playing drums; celery stalks being broken by human hands; a cow head with cow bells turning side to side as Tchaikovsky’s bells peal; eggs breaking in a frying pan—all syncopated to the bombastic sounds of the Overture.

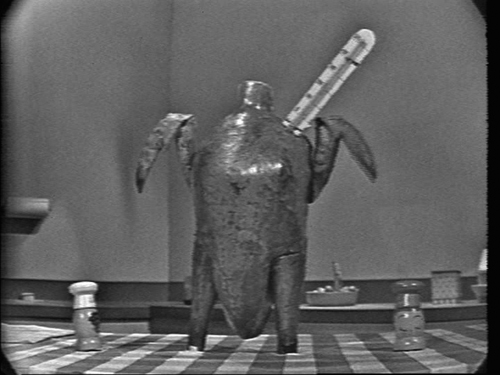

In other ABC specials Kovacs prepared musical montages such as the “Kitchen Symphony” and “Jalousie” (also called “Musical Office”) that juxtaposed images of everyday objects against musical tracks that work rhythmically but also contrapuntally to create absurd mechanical ballets.[13] The former features, for example, a jumping coffee pot, sardines rolling out of a can, a peeling banana, toast popping up, an exploding salad and a dancing chicken. The surreal sensibility of Kovacs’s performing quotidian objects can easily be compared to Averty’s 1963 Les raisins verts, which features a kitchen grinder “chewing” up a baby doll. But in Kovacs’s case, the sound-image relation is the principal obsession, one that harks backs to avant-garde conceptions of sound cinema in the 1920s.

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

In particular, Kovacs’s montages recall Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov’s “A Statement on the Sound-Film” (1928), in which they asserted the value of montage and the use of sound not as canned theatre (as in Hollywood “talkies”) but as “contrapuntal” within and against montage sequences to create “orchestral counterpoint of visual and aural images.” Kovacs’s use of silence, music and montage also echoes Dada, Surrealist and Futurist performances in the 1920s (some of which used radio), as well as experiments with “musique concrète” that used a cut-up aesthetic by, for example, re-editing and splicing together audio and film soundtracks to produce absurd, anti-realist effects. So, too, his fascination with silence occurred parallel to contemporary American experimental composers, most obviously John Cage, whose performance piece 4’33” (created in 1952) featured musicians playing nothing.[14] And finally, Kovacs borrowed directly from Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera (1928), using Kurt Weills’s “Mack the Knife” in many of his programs.

Over the course of his TV career, Kovacs established a loyal following of anti-television viewers, people who believed that their love of Ernie demonstrated that they had better taste than average television viewers who did not “get” him. In publicity and interviews Kovacs cultivated his offbeat status, fanning the flames of his TV fans by directing them to appreciate the medium’s affordances for artistic experimentation and its ability to provide a popular theatre of the absurd.

Charles and Ray Eames: Collage, Montage and Graphic Design

Charles and Ray Eames are best remembered today for their work in a range of venues (world exhibitions, museums, corporations, Hollywood) and for their accomplishments in multiple media including architecture, graphic design, painting, furniture (especially their famous chairs) and films (both sponsored films for corporations and experimental films such as Powers of Ten [1968/1977]). But historians, critics and biographers have almost entirely erased their considerable interest in television. Although to different degrees and with different overall aesthetic results, they shared Averty’s interests in graphic design, collage, montage, comics, literary adaptation, animation and jazz. In addition, like Averty, their working method was archival, based on the collection of a huge image bank. Just as Anne-Marie Duguet (1996, p. 53) observes that Averty chose from his archive to condense the maximum amount of “information” into the shortest measure of television time and space, the Eameses thought about their archive as information that could be condensed through collage and montage at rapid speeds.[15] Nevertheless, unlike Averty (and Kovacs), who approached television as a medium in its own right, the Eameses worked with 35 and 16mm film, ultimately seeing TV as a transmission medium for cinematic montage and animation.

The Eameses’ television productions were part of their more general interest in communication theory and education. Impressed with Claude Shannon’s theory of communication (especially his ideas about feedback and “noise” in communications flows), and equally inspired by the burgeoning discussion of the visual language of design (especially the work of György Kepes), the Eameses considered how they might design media in ways that retrained vision and created new forms of comprehension. Although they worked for large corporations (most consistently IBM) and the United States Information Agency (USIA), the Eameses seemed to have little problem at once manipulating media (for marketing and Cold War persuasion) while at the same time using media for art and education.

In 1953 the Eameses made their first foray into television, creating an episode of the cultural affairs show Discovery, which was produced by the San Francisco Museum of Art and broadcast on the local CBS affiliate station, KPIX. Discovery was primarily a live in-studio interview format, but the Eameses tried to avoid what Charles called the live “studio panic” by creating film segments.[16] The opening film (much of which Ray initially plotted out on paper) is a montage of their home’s exterior with slow pans and artfully composed shots of nature, objects and architectural details. (It looks like an early draft of their 1955 film House: After Five Years of Living.) Another film told the history of automobile design via limited animation in the modern graphic style. The longest (roughly ten minutes) film, “Story of a Chair,” is the most elaborately designed. The Eameses arranged tools and construction parts to create visual patterns, and combined reverse negatives, X-rays, sketches, moving images and Ray’s graphic ads for the Eames chairs.

The live in-studio sections of the program featured host Lloyd Luckmann interviewing Charles and Ray (although Charles did most of the talking). Detailing his design philosophy, Charles said: “I think that anytime one or more things are consciously put together in a way that they can accomplish something better than they could have accomplished individually, this is an act of design. Combining rye bread and Swiss cheese was a great act of design. The value of the result, the sandwich, is not the value of rye bread plus cheese, but it is rye bread plus cheese raised to the nth power.”[17] A layperson’s explanation of montage, Charles’s theory of design served as a guiding principle for the visual rhetoric the Eameses created in the filmed segments. Rather than just visual aids for talk, the Eameses conceptualized their made-for-TV films as a means of creating poetic images irreducible to verbal explanations. Even as the studio interview and Luckmann’s narration anchor their films to the time and space of live TV, the montages present viewers with a pattern of images which when “put together” (if we follow the “rye and Swiss” metaphor) will produce a third term—TV to the nth power.

Throughout the decade the Eameses continued to engage with television. In 1956 they appeared on NBC’s daytime show Home, where they screened their Eames Lounge Chair film; in that same year they drafted a script for an unaired episode of the CBS cultural affairs program Omnibus (which they conceived as a lesson in design and communication theory).[18] They loaned their abstract montage film Blacktop (1952) for use on the March 24, 1958 episode of the KABC/ABC program Stars of Jazz, and for the April 14, 1958 episode they created new black-and-white footage (which eventually became their colour film Tops [1969]). By far, however, the Eameses’ greatest television effort came with the CBS special The Fabulous Fifties, a ninety-minute program sponsored by General Electric appliances and television sets and broadcast on January 22, 1960.

Produced by Leland Hayward (most famous then for his Broadway productions of Gypsy and The Sound of Music), the special was a nostalgic—if also satiric—journey through 1950s America. But despite its nostalgic premise, The Fabulous Fifties was an advertisement for the future of television as a distinctly modern medium and cultural form. GE’s slogan, “Progress is our most important product,” was featured in commercials. Like many Cold War era specials, this one was also an advertisement for America as co-hosts Henry Fonda and Eric Sevareid (a CBS newscaster) pontificated on America’s future as the saviour of the free world.

Giving both technological and national progress a progressive look, the special utilized the talents of a variety of design “stars.” Photographer/designer Richard Avedon directed a lushly lit film segment starring fashion model Suzy Parker. Set designer Willard Levitas created backdrops with modern graphic cartoon-style illustrations against which Fonda and Sevareid introduced various acts. A young Dick Van Dyke performed an elaborate dance sequence in which he popped out of a wallpaper-like backdrop covered in swirling black-and-white modern shapes, and his shirt matched the wall to create a trick visual effect. (Although created purely with set decoration and costume, the overall result was similar to the videographic “pages” for which Averty would become famous.) More than any other artists, however, Charles and Ray Eames were the primary architects of The Fabulous Fifties’ modern visual style.

At the time Hayward first conceived the program, the Eameses were creating Glimpses of the USA, a seven-screen film composed of more than 2,200 still and moving images, which was shown at the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow. Impressed with their visual innovations, Hayward hoped to transfer their multi-screen film technique to the single monitor of the small living room screen. When promoting the program, Hayward especially exploited what he called the Eameses’ “unique photomontage technique,” which delivered “a rapid succession [of] photos of new events . . . advertisements, headlines, ideas, events, magazine pages, popular songs” and more.[19] The final result was six segments, approximately twenty-six minutes of visuals, dispersed throughout the program.

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Jean Bouise, as Père Ubu, “pops” out of a videographic “page” in Ubu Roi (Jean-Christophe Averty, 1965).

Placed in the opening act, the Eameses’ Music Montage was a roughly eight-and-a-half-minute tribute to 1950s entertainment history. Shot on film, the montage is composed of songs and images featuring celebrities, photographs and ephemera from Hollywood films and Broadway shows, graphic designs and animation, album covers, postcards, news footage, assorted props, recording equipment, and the like. Not only was the editing rapid by the standards of the time, the Eameses often panned over or zoomed into photographs (which were cropped to different scales), mixed still and moving images, and punctuated segments with a kaleidoscopic special effect which appears to come from their 1959 film Kaleidoscope Shop (and which looks very much like Kovacs’s earlier live in-camera juice-can kaleidoscopes). The images were set to music from the era including, for example, Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog,” the space-age classic “Volare” (with filmed footage of seagulls soaring), Harry Belafonte’s “Matilda,” Peggy Lee’s “Fever” (with fire burning over a picture of Lee), and Broadway hits (capped off with Ethel Merman in Leland Hayward’s Gypsy). Yet, despite its “top of the pops” premise, the segment is at times unnerving, creating dissonance through unlikely juxtapositions, superimpositions, image manipulations (such as reverse negatives) and audio distortions. Towards the end, the montage repeats some of the earlier images and tunes (such as “Hound Dog” and “Matilda”), but now these are overlaid with menacing and warbled sound mix.

As evidenced in their working drafts, the Eameses used what now looks like a digital sensibility before the advent of digital media—“photoshopping the analogue way” (Spigel 2016, p. 42). Following their strategy for Glimpses, they amassed an archive of found images from magazines, graphics, photographs, comics, publicity stills and other ephemeral sources. Drawing on this archive (much of which was supplied by Hayward and CBS), they matched images to the musical sequence assembled by Hayward’s staff, creating score sheets with colour pencils and charting out inches (as if with a ruler) to measure the precise timing of each match.[20] They used numerous forms of montage and collage, creating striking juxtapositions, cutting on rhythm and, increasingly, using editing to produce a disturbing tone, with the goal of creating what the Eameses called “connections,” which they hoped audiences would make between the materials.

Given the Eameses’ techniques, it is interesting to note that the only book on film which Charles admitted reading was Sergei Eisenstein’s Film Sense, which lays out Eisenstein’s theory of montage.[21] Yet, even as the Eameses’ films use elements of tonal, metric and rhythmic montage and often proceed from a dialectical theory of film akin to Eisenstein’s, the montages nevertheless often use images in more realist storytelling ways, as visual illustrations of musical themes and lyrics. In his discussion of Glimpses, Eric Schuldenfrei (2015, p. 72) argues that while the Eameses used montage techniques similar to those outlined in Film Sense, they relied as much on Hollywood continuity editing and linear narrative as they did on Soviet montage theory, a point that applies equally to the Eameses’ work for The Fabulous Fifties.

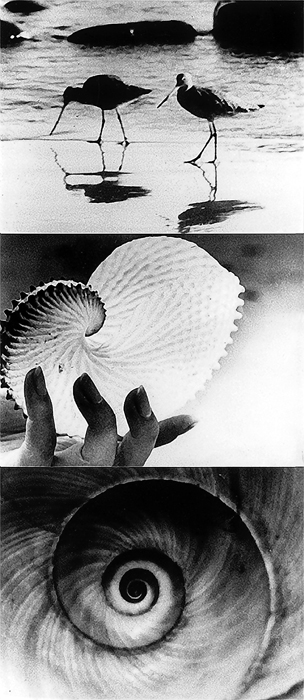

In addition to the opening montage, the Eameses created three shorter montage sequences: Vital Statistics (a brief account of births and a photomontage entitled “Dead” mourning celebrated persons who died in the 1950s); Funny Papers (reflecting Charles’s interest in comics); and de Gaulle (a photojournalistic montage of the French general and president with images of the Algerian uprisings). They also adapted two popular books of the era. For Robert Paul Smith’s Where Did You Go? Out. What Did You Do? Nothing (a 1957 children’s book with adult appeal), the Eameses collaborated with animator Delores Cannata, who worked at UPA and created the animation for the Eameses’ film The Information Machine (1957), commissioned by IBM. For Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s Gift from the Sea (1955) they created a photomontage of seashells, shorelines, waves, birds, rocks, plant life and the like, all set to a score by Elmer Bernstein and explored through pans, rhythmic motion and extreme close-ups that render nature into abstract designs. With Gift the Eameses returned to the sombre tone at the end of the music montage, here by creating a maudlin reflection on the emotional turmoil of women’s lives (a subject of Morrow Lindbergh’s book).

The Fabulous Fifties received mixed reactions. Hayward and the Eameses won Emmys, but many television critics were lukewarm at best. The audience mail saved in Hayward’s files (about eighty letters and postcards) was about 60% unfavourable. By far, the Eameses received the most vehement attacks. Viewers referred to the Eames segments as a “mass of jumbled confusion,” “mish-mash” and “a discontinuance of patterns that only offended the seeing sense.”[22] As the letters suggest, modern design on television did not always appeal to audience tastes.

The Eameses worked in a more limited way with Hayward on the 1962 CBS special, The Good Years. But apart from minor projects (such as interviews or film loans), they parted ways with TV.[23] In the early to mid-1960s, they returned to their work for exhibitions, including their monumental 22-screen presentation in the IBM pavilion at the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair. In this regard, like Averty, they anticipated logics of digital collage and montage before the widespread use of computers, and TV was for them a link to that digital logic.

Fig. 8

A sample of frames from Where Did You Go? Out. What Did You Do? Nothing. Charles and Ray Eames and Delores Cannata for The Fabulous Fifties (CBS, 1960).

Fig. 9

A sample of frames from Gift from the Sea. Charles and Ray Eames for The Fabulous Fifties (CBS, 1960).

TV Art before Video Art

In the 1960s, the experimental spirit of people such as Averty, Kovacs and the Eameses went in two seemingly different directions. On the one hand, television commercials increasingly experimented with montage, collage, graphics, sound and colour. Television advertisers thought that new experimental techniques would appeal to second-generation, “TV literate” viewers who had grown weary of commercials with slow product demonstrations, corny narratives and long-winded testimonials. In the context of Madison Avenue’s “creative revolution,” advertising artists became interested in art cinema and underground film, and they went to such venues as Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16. (In fact, for The Fabulous Fifties Hayward told his production team to go to the Cinema 16 Festival for ideas for the show.[24]) The advertising trade journal Art Direction reviewed art cinema (everything from Antonioni to Fellini to Godard) and mined it for advertising techniques—montage, jump cuts, collage, etc.[25]

On the other hand, the experimental spirit exhibited by Averty, Kovacs and the Eameses took the path of video art. Montage, collage, graphics and special effects, as well as sound and colour experimentation, were important to video art. But video artists were often interested in different aesthetic issues from those that occupied earlier television artists (issues such as duration and boredom), and they developed some of the earlier creators’ concerns (such as the Eameses’ fascination with noise and feedback) to different ends. Moreover, artists such as Nam June Paik, Joan Jonas, Dan Graham and Richard Serra often saw video in relation to 1960s and 70s art movements (such as performance art), the counterculture, and/or as direct attacks on mainstream TV.

In this respect, the legacy of the early television work by Averty, Kovacs and the Eameses is complex. Insofar as their television programs were aimed at popular audiences, these early TV artists do not in any simple way match up with the more radical goals of video artists, many of whom denounced popular television altogether. Instead, their legacy is found in their eclectic crossing of borders between art, commerce and popular entertainment. All three pursued a counter-televisual practice that was not against TV, but rather for it.

Exploring these counter-television practices helps to reframe ingrained and essentialist thinking about television as a form of “low” culture and video art as its “high” art corrective. Increasingly, historians and curators are beginning to unpack some of these complex border crossings between television and art in a variety of national contexts.[26] But there is still much more to do. For example, historians should further examine TV’s relation to developments in the graphic arts, architecture, animation, painting, comics, sound, music (especially jazz), set design, experimental cinema, museum initiatives and/or communication theory through which people such as Averty, Kovacs and the Eameses developed their approach.

Early television was never simply art’s opposite. Before video art, there was TV art—a counter-aesthetic to mainstream TV, but also a popular form of everyday art framed as broadcast entertainment.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Margaret H. McAleer, Mark Quigley, David Herstgaard, Allon Schoener, Rosemary Hanes and Anne Pavis.

Notes

-

[1]

Averty discusses his work for Disney and ABC (where he claims to have worked on baseball games) in Jost and Chambat-Houillon 2011 (p. 145). In 1977, Averty directed an NBC TV special, How the Beatles Changed the World.

-

[2]

See “Baby im Fleischwolf,” Der Spiegel (February 17, 1965), p. 108. For the telecast of the award ceremony see http://www.ina.fr/video/CPF86633324/paris-a-l-heure-de-new-york-emission-du-28-mai-1964-video.html.

-

[3]

Maurice Berger’s recent exhibition Revolution of the Eye (Jewish Museum, New York, 2015), for which I served as a principal consultant, and his exhibition book of the same title also cover this material.

-

[4]

For more on Kovacs see Spigel 2009 (pp. 178-212).

-

[5]

Averty recalls his love of Mad in Jost and Chambat-Houillon 2011 (p. 147). Kovacs wrote for and/or gave interviews to Mad and similar satire magazines.

-

[6]

Kovacs, quoted in Murray Schumach, “Kovacs Explains Wordless Shows,” New York Times (December 21, 1961), p. 31.

-

[7]

This was an hour-long program. Jerry Lewis hosted the other half hour.

-

[8]

Hoppe supplied these to several other TV shows at the time, and Mobilux was used in experimental performances; see Chapman 2015.

-

[9]

Dwight Newton, n.t., San Francisco Examiner (January 22, 1957).

-

[10]

It’s interesting to speculate whether Averty (who was in California in 1961 and worked at ABC) would have seen the Kovacs specials. The specials aired from April 20, 1961 through January 23, 1962.

-

[11]

Scott S. Runge to Milt Hoffman, inter-department correspondence, “Subject: Ernie Kovacs Special # 3” (May 15, 1961), Kovacs Papers.

-

[12]

See Spigel 2009 (p. 196).

-

[13]

The “Kitchen Symphony” appeared in Special #4 (broadcast September 21, 1961). “Jalousie” appeared in Special # 3 (broadcast May 15, 1961).

-

[14]

Cage performed Water Walk on the CBS TV game show I’ve Got a Secret in 1960.

-

[15]

See Schuldenfrei 2015 (pp. 19-36).

-

[16]

Charles Eames, letter to Allon Schoner (September 14, 1953), Projects File, Folder San Francisco Museum of Art, Discovery Television Program, 1953, Eames Papers. Note that the Library of Congress permitted me to research this collection before it was fully catalogued, and my citation method reflects this.

-

[17]

Although the actual TV program contains similar language, I am quoting from a script Charles wrote: “Eames Television Script, Final Version” (December 12, 1953), Projects File, Folder San Francisco Museum of Art, Discovery Television Program, p. 3, Eames Papers.

-

[18]

The Omnibus scripts are in Projects File, Folder Omnibus, Eames Papers.

-

[19]

“Script Outline—Dialogue Topics Closed Circuit Fabulous Fifties”(January 14, 1960), Box 110, Folder 6; and “Leland Hayward Presents the Fabulous Fifties” (July 1959), Box 110, Folder 14, p. 1, Hayward Papers.

-

[20]

“Telephone Conversation Between Mr. Hayward and Ray Eames” (January 8, 1960), Box 110, Folder 4, Hayward Papers; and Projects File, Folder The Fabulous Fifties Films, Segments “Music of the 50s” (1 and 2), 1959-1960, Eames Papers.

-

[21]

Eric Schuldenfrei (2015, p. 76) discusses Charles’s relation to Eisenstein’s book.

-

[22]

Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Fazekas and neighbours, letter to NBC (February 1, 1960), Box 110, Folder 1; Helen Johnstone, letter to CBS (January 30, 1960), Box 110, Folder 1; Skagden, letter to CBS (February 1, 1960), Box 110, Folder 1, Hayward Papers.

-

[23]

Charles was interested in early cable.

-

[24]

Leland Hayward, memo to Marshall Jamison, “Subject: Fabulous Fifties” (September 21, 1959), Box 110, Folder 3, Hayward Papers.

-

[25]

See Spigel 2009, chapter 6. Note that advertisers also copied Kovacs’s innovations with silent commercials, which he made for Dutch Masters Cigars.

-

[26]

In addition to books by Anne-Marie Duguet, Maurice Berger and myself, see for example John Alan Farmer (2001), Laura Mulvey and Jamie Sexton (2007), David Joselit (2007) and Maude Connelly (2014).

Bibliography

- Berger 2015: Maurice Berger, Revolution of the Eye (exhibition catalogue), New Haven, Yale University Press, 2015.

- Blanchard 1969: Gérard Blanchard, “J.C. Averty : l’héritage de la page imprimée,” Communication et langages 2 (1969), pp. 59-65.

- Chapman 2015: John Chapman, Psychedelia and Other Colours, New York, Faber & Faber, 2015.

- Connelly 2014: Maude Connelly, TV Museum, Bristol, Intellect, 2014.

- Duguet 1996: Anne-Marie Duguet, Jean-Christophe Averty, Paris, Dis Voir, 1996.

- Eisenstein 1942: Sergei Eisenstein, Film Sense, translated by Jay Leyda, New York, Harcourt, 1942.

- Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Alexandrov 1928: Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Grigori Alexandrov, “A Statement on the Sound-Film” [1928], in Sergei Eisenstein, Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, translated by Jay Leyda, New York, Harvest, 1969 [1949], pp. 257-60.

- Farmer 2001: John Alan Farmer (ed.), The New Frontier: Art and Television, 1960-65 (exhibition catalogue), Austin, Austin Museum of Art, 2001.

- Joselit 2007: David Joselit, Feedback: Television Against Democracy, Cambridge, MIT, 2007.

- Jost and Chambat-Houillon 2011: François Jost and Marie-France Chambat-Houillon, “Entretien avec Jean-Christophe Averty,” Télévision 2 (2011), pp. 136-69.

- Mulvey and Sexton 2007: Laura Mulvey and Jamie Sexton (eds.), Experimental British Television, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2007.

- Schuldenfrei 2015: Eric Schuldenfrei, The Films of Charles and Ray Eames: A Universal Sense of Expectation, New York, Routledge, 2015.

- Spigel 2009: Lynn Spigel, TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Spigel 2016: Lynn Spigel, “Back to the Drawing Board: Graphic Design and the Visual Environment of Television at Midcentury,” Cinema Journal 55:4 (Summer 2016), pp. 28-54.

- Wyver 1988: John Wyver, “Video Art and Television,” Sight and Sound (Spring 1988), pp. 116-22.

Archival Collections Consulted

- Archives écrites Jean-Christophe Averty, Institut national de l’audiovisuel, Paris, France.

- The Charles Eames and Ray Eames Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

- Ernie Kovacs Papers, 1940-1962, Charles E. Young Research Library, Department of Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

- Leland Hayward Papers, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, New York, NY.

- Moving Image Research Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

- The Paley Center for Media, New York, NY.

- UCLA Film and Television Archives, Los Angeles, CA.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Lynn Spigel est professeure en études médiatiques à la Northwestern University. Elle a publié de nombreux articles et plusieurs ouvrages, dont Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (1992) et TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television (2009). Elle est également l’auteure d’un livre à paraître, intitulé TV Snapshots: An Archive of Everyday Life.

Liste des figures

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9