Résumés

Abstract

This article examines how the comic series The Katzenjammer Kids, created by Rudolph Dirks in 1897 and whose main characters are two wicked children, has been usually altered, modified, and reframed due to its publication in Spain and Italy. By using the concept of domestication and utilizing tools of the history and formal analysis of comics and the contextual studies used in iconography, we try to study the influence and the afterlife impact of the forms, narratives, and gags of The Katzenjammer Kids and, at the same time, to provide a theoretical-methodological framework for understanding the cultural scope of these phenomena that characterize a field of study such as comics reception, which has been relatively underdeveloped.

Keywords:

- Domestication,

- Katzenjammer Kids,

- Busch,

- Knerr,

- Dirks,

- Spain,

- Italy,

- comics studies,

- Corriere dei Piccoli

Résumé

Cet article examine comment la série de bande dessinée The Katzenjammer Kids, créée par Rudolph Dirks en 1897 et dont les protagonistes sont deux enfants espiègles, a été très souvent altérée, modifiée et adaptée en raison de sa publication en Espagne et en Italie. À partir du concept de domestication et en utilisant les outils de l’histoire et de l’analyse formelle de la bande dessinée ainsi que les études contextuelles utilisées en iconographie, nous tentons d’étudier l’influence et de la survivance des formes, des récits et des gags de The Katzenjammer Kids. Nous cherchons aussi à fournir un cadre théorique et méthodologique pour comprendre la portée culturelle de ces phénomènes qui caractérisent un champ d’étude tel que la réception de bandes dessinées, qui a été relativement sous-développé.

Mots-clés :

- Domestication,

- Katzenjammer Kids,

- Busch,

- Knerr,

- Dirks,

- Espagne,

- Italie,

- comics studies,

- Corriere dei Piccoli

Corps de l’article

The Katzenjammer Kids (1897) is a globally circulating comics series whose source is often contested. As one of the most copied American series in European children’s comics magazines, it is an ideal object for the study of domestication, which is an investigation that encompasses “an entire transnational cultural field . . . to see that what it does is not merely textual translation from one language to another or straightforward importation of objects from one country to another – but rather a complex, organized, collective process.”[1] In this article, we study the cultural phenomena of mutations, readjustments, and variations of The Katzenjammer Kids caused by its publication in Spain and Italy. At the same time, we try to provide a theoretical‑methodological framework for understanding the cultural scope of these phenomena, which characterize the field of comics reception, which is still underdeveloped in the context of comics studies.[2]

TheKatzenjammer Kids was commissioned by the American newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who wanted to own a series on a naughty rascal that could compete with the two‑year older Yellow Kid (1895) in Pulitzer’s New York World. But, while Richard Felton Outcault’s Yellow Kid was based on the drawings of street kids by the American Michael Angelo Woolf, Hearst asked Rudolph Dirks to produce “a comic strip in the style of Max und Moritz . . . [which] had appeared in Comic Cuts in 1896 under the title Tootle and Bootle.”[3] William Randolph Hearst’s role in the history of comics is, in many ways, that of a creative producer, as in cinema David O. Selznick or Robert Evans. Hearst could model Dirks and Outcault’s style, forcing them to heighten the concatenation between panels, creating more agile sequences, and using balloons.

Given that Hearst was a conspicuous collector of German illustrated books and comics and had enormous admiration for Wilhelm Busch and even for the Swiss Rodolphe Töpffer,[4] his request to Dirks involved transferring the Central European comic book’s emerging universe to the American press through the central characters of two wicked children. How did Dirks’ version of Busch’s Schrecklichkinder then travel ‘back’ to Europe?[5] What effects did the new publication context produce? How did it affect a comic conceived for the general press to be published in children’s magazines? What kind of modifications occurred in the form, meaning, or interpretation?

To understand the influence of Dirks and Busch in Spain and Italy, this paper will start by surveying the presence of their works (namely Max und Moritz, Tootle and Bootle, and The Katzenjammer Kids) in both countries. We will try to understand whether the Spanish or Italian reader would have understood that they were reading a German product. While the relationship between Max und Moritz and The Katzenjammer Kids was evident to German readers, French readers, for example, were unaware of the reworkings of Max und Moritz due to a late translation of Busch’s masterpiece.[6] Were Italian and Spanish readers aware of the German and American influence?

The paper also delves into publishing norms and explores the cultural adaptations made in transposing Hans and Fritz for Spanish and Italian audiences. This paper analyzes The Katzenjammer Kids’ linguistic transposition as the manifestation of domestication through specific practices such as translating, editing, and lettering.[7] This domestication helps us define the ideal reader of the series in Italy and Spain, respectively. Without aspiring to carry out a “diagnosis of the culture” of the time—of contexts such as that of fascism in Italy or the Civil War in Spain—the paper gives broad outlines that define the reader of each time and moment, following the premise of the documentary recontextualization typical of an iconographic methodology.[8] We do not perform an iconographic or iconological task, but lay the foundations for a contextual and comparative approach ‑ a comparative hermeneutics ‑ of the modes of domestication and edition that elucidates the cultural conditions of reception and circulation of this comic.

The paper is furthermore interested in what “bricolaging” and local iterations that set seemingly ‘typical’ German or American characters in Spain and Italy can teach us about the spread of a cultural form and its shifts.[9] Finally, taking up the sociological perspective that Casey Brienza uses (based on Bourdieu and Gereffi) to examine manga production in America, we study the collective labour involved in the transposition of The Katzenjammer Kids to map out three fundamental aspects beyond the study of publishing policies that are key to our comparative approach.

First, we will link the Spanish and Italian adaptations and their implied readership. We discuss how different publishing models constructed a horizon of expectations and demanded modes of consumption that differ from the ‘original’ Katzenjammer series. To do so, we also look at the circulation of Busch’s Max und Moritz in Spain and Italy.

Second, we focus on the transformation of the new American comics format, characterized by a dynamic written language, speech balloons, and based on visual gags —like slightly later strips such as Frederick Burr Opper’s Happy Hooligan (1897) and Winsor McCay’s Little Sammy Sneeze (1904). We investigate how the Italian and Spanish publications incorporated this format and explore whether adapting publishers embraced or rejected it. Did they have confidence in the interpretative capacities of their readers? Or did they, such as in the case of Corriere dei Piccoli, decline balloons and opt for rich, creativerhyming verse that accompanies the panels while reminiscing Busch’s texts?

Lastly, the paper examines the cultural singularities associated with the trope of the naughty twin both in the countries of original publication (Germany, the US) and in Italy and Spain, considering how this trope reflects the social construction of the child as the focal point of bourgeois civilization or colonialism.

The formal mutations, translations, and transliterations of TheKatzenjammer Kids in Spanish and Italian children’s comics magazines raise questions of plagiarism and the stability of the term “original.” Inspired by Wilhelm Busch’s Max und Moritz, TheKatzenjammer Kids was drawn “double” by Dirks for Hearst (1897‑1914) and then later for Joseph Pulitzer as Hans und Fritz and The Captain and the Kids (1918‑1979).[10] From 1903 to 1914, Harold Knerr drew The Fineheimer Twins, a series inspired simultaneously by Busch’s Max und Moritz and The Katzenjammer Kids. This made it obvious that Knerr was the ideal artist to replace Dirks on The Katzenjammer Kids in 1914, when Dirks left Hearst’s New York Morning Journal after a legal dispute. During World War I some newspapers retitled the strip The Shenanigan Kids, and the nationality of the characters was changed to Dutch instead of German because of wartime anti‑German feelings. The series changed back to its original name and contents in 1920, and Knerr continued to write and draw the strip until he died in 1949, when Charles H. Winner took it over.

These competing ‘American’ products flooded the European market. Both Dirks and Knerr’s pages were published in European children’s periodicals. From 1915 the Italian Corriere dei Piccoli, for example, drew from Pulitzer’s The New York World and Hearst’ The New York Journal.[11] The two tricksters’ names were Italianized to Bibì e Bibò e Capitan Cocò‑Ricò. Unfortunately, the mixture of German and English did not make it to the Italian translation.

In Spain, likewise, different periodicals introduced the naughty children, with the particularity that over the years pages from both Dirks and TheKatzenjammer Kids by Knerr were published.[12] In addition, the German characters inspired much‑beloved derivatives in Spain, the most important of whom were Josep Escobar’s Zipi y Zape (1948‑1994).

The Sources and the Original Publication of Busch and Dirks in Spain and Italy

Perhaps due to Italy’s closer proximity to Germany than Spain and thus there being a greater likelihood of finding Italian translators from German, Italian periodicals recuperated “Guglielmo Busch” quite early on compared to their Spanish counterparts. Giovanna Ginex shows that the Christmas special issue of the Milanese newspaper Corriere della Sera dedicated an entire front cover (see Figure 1, 1887) to a domesticated part of the story of Die fromme Helene [Pious Helen] by Wilhelm Busch (1872). The panels only represent the beginning of the story about Helene, ignoring the story’s ironic take on religiosity and piety. Thus, the story is reshaped as an instructional cover for children who might receive the special Christmas supplement for edification. The moral tale about the naughty Elenina depicts a girl staying with her uncle and aunt, with rhyming narrative; her naughtiness is punished, not physically but psychologically, as she is confronted with her misdeeds and ultimately sent away. Corriere della Sera keeps this first moralizing part of the pious Helene tale to urge child readers to obey their parents or guardians, while the rest of Die fromme Helene (including alcoholism, unlawful children, death, and hell) is completely censored from this Italian cover.

Figure 1

Corriere della Sera, Christmas Issue 1887, p. 1

While Corriere della Sera did not have a children’s supplement yet (it would only do so from 27 December 1908), other nineteenth‑century children’s periodicals would use Busch’s proto‑comics, both in Italy and Spain. As Fabio Gadducci has shown, on 8 December 1881 Giornale per i bambini, one of the earliest children’s Italian periodicals, published Wilhelm Busch’s work by featuring the story of Die Fliege [The Fly] on its cover (Figure 2).[13]

Figure 2

Giornale per i Bambini 23, December 8, 1881

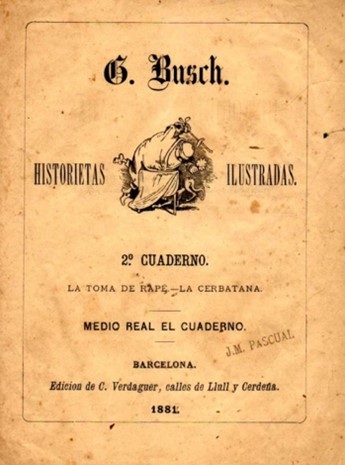

If we compare the Italian version to the German original, the latter has hardly been touched.[14] The adaptation involves only a translation of the rhyming couplets, which in Italian are numbered to ensure proper reading order. In the same year (1881), various proto‑comics by Busch appeared in Spanish publications—again not in general newspapers or Bilderbogen, but in a magazine specifically dedicated to children, Historietas ilustradas (1881), whose seven issues were entirely devoted to Busch. The pages of Max und Moritz collected in this publication show an aesthetic proximity with some works that Catalan and Spanish readers were used to, such as Apel·les Mestres’ Granissada (1880). That allowed a continuous monographic publication in 7 issues, evidences an artistic dialogue in this genre throughout Europe, and underlines the influences of the German artist on the dynamic conditions of visual gags.[15]

Figure 3

Historietas ilustradas. Guillermo Busch, Barcelona: C. Verdaguer, 1881

From Busch to Dirks

What is it that changes when the misdeed of pranksters in continental broadsheets are fitted to the Sunday comics supplements of American newspapers and from these to European children’s periodicals? According to Pascal Lefèvre, while the former punished the pranksters severely and unescapably, the mischief gag comics in illustrated magazines of American origin put the transgression front and centre.[16] Moreover, thanks to the centrality of the transgression, even when the culprits were eventually reprimanded, the mischief gag comics granted the reader vicarious enjoyment. At the same time, he or she was aware that these comics were not real since they were drawn;[17] David Kunzle has similarly asserted that such child rebels’ impunity allowed their readers to (safely and vicariously) enjoy power.[18]

While Dirks diminished the German original’s punishments to achieve a more significant comic impact, he also altered Busch’s sociolinguistic game.

The play on sociolinguistic parameters in Katzenjammer Kids certainly originates from the Buschian model, even if it no longer serves the same function in the American mainstream press. In Busch’s work, the sociolect variations in style and the play on the registers of standard German in the passages of direct speech indicate a critical distance from the adult characters. As for Dirks’ characters, whether children or adults, they all speak non‑standard Anglo‑American with a strong German accent.[19]

Dirks thus took advantage of the novel element of the speech balloon. Still, the intricate sociolinguistic separation between the characters was lost in favour of a generalized Anglo‑American.

European domesticators of the American series did not imitate the play on accents. In fact, the French translator Cavanna lamented the suppression of this essential element in the “distressingly platitudinous” French translations.[20] Thierry Smolderen remarks that Dirks’ Katzenjammer Kids did not offer the irony of the narrator’s voice that Busch included (even in his pantomime strips), but resorted to mechanical and visual burlesque for humorous effects.[21] Smolderen names the burlesque pantomime Fliegende Blätter by Emile Reinicke, Meggendorfer, and Schlieβmann as specialists of such burlesque mischief gags.[22] The fact that, as we will show, many Spanish and Italian children’s periodicals reprinted The Katzenjammer Kids with captions continued an element of Busch’s ironic distance, but not his sociolinguistic approach, as they invoked a child reader or an adult chaperoning that child.[23]

As Lefèvre states, the gatekeeping of publishers and their specific formats should not be underestimated.

Publishers—whether large or small—have played an ineluctable role in the development of the global culture of graphic narrative since the nineteenth century. These entrepreneurs were also responsible for launching conventional publication formats, such as the many types of serial publication (like comic strips or comic books in the USA, weekly or monthly manga magazine and tankōbon in Japan, weekly comics magazines and album series in Western Europe, etc.). The influence of such publication formats on the work itself cannot be underestimated.[24]

Italy and Spain were not the ethnic and cultural melting pot that the early‑twentieth‑century United States was, as Gino Frezza emphasizes.[25] While the German immigrants in the American series encourage illiterate immigrant readers from lower social classes to buy newspapers they would not usually acquire (as they could not understand them), TheKatzenjammer Kids in European children’s weekly magazines talk to children who are learning their mother tongue. The fact that the implied reader of Los Muchachos or Corriere dei Piccoli was a child training her or his literacy explains the elimination of the original’s sociolinguistic variation in favour of standard language.

Even though the ungrammatical language is lost, what is maintained should not be taken lightly. As Frezza states, slapstick, the gestural comedy, creates complicity with the readers. To be entertained is to become a loyal fan of the comics, following them every week.[26] Moreover, Frezza continues, this and other series’ comicality have shaped the languages of comics and constructed a complete symbolic and social universe.

In another contrast to the Anglo‑American approach, another way of engaging the local reader of a global series was the use of local expressions. In the Spanish editions, exclamations such as “caracoles” or the appearance of card games such as tute and mus (very popular at the time) anchored the characters’ voices in the local context.[27] It is also noteworthy that, far from using jargon or ungrammatical forms, both adults and children in these versions tend to use correct and even cultured language. In one example, after causing mischief a character says: “Paréceme haber oído rumor de pequeñas discusiones familiares; Sí, y lo mejor sería obrar wprudentemente poniendo agua de por medio.” The literal translation would be “I seem to have heard rumors of little family arguments; Yes, and the best thing would be to act prudently putting water in between,” but the cadence, the pronoun incorporated at the end of the verb, and the vocabulary have an aulic, almost Shakespearean resonance. The contrast between this theatric language and the debased actions heightens the amusing effect.

It is worth pointing out here that the various Argentine editions, which coexisted over time and eventually arrived in Spain under the title “El capitán y sus dos sobrinos” in the newspaper El Sol, went further and put long sayings or local prayers for agricultural fertility in the mouths of the characters.

In the case of Corriere dei Piccoli, the Italian version not only failed to mention the American comics artist or the name of his serial figure in an attempt—a marketing strategy—to insist on the heroes and the artists being Italian, but the magazine domesticated characters’ names to avoid miscommunication. The Italian names Bibì and Bibò were substituted for the children’s German names, removing the immigrant association and thus (as Van Wiele has claimed elsewhere, following Christiane Nord), “setting the story in the receiver’s own cultural world so that there is room for identification, and as a consequence pedagogic messages to be better transferred.”[28]

Transposing the Format to Spanish and Italian Comics Magazines

According to certain comics historians such as Pierre Fresnault‑Deruelle, comics’ history starts with Dirks and TheKatzenjammer Kids (1897, New York Journal), not Outcault and Yellow Kid (1895, New York World), because Dirks’ series uses balloons systematically for the first time, without using captions. “The series’ format is constituted fully on the balloon and on the compartmentalization into framed panels.”[29] Most European publishers and artists fought against the use of the speech bubble until the 1960s.[30] The balloon was understood as an American invention or a critical attempt to blur the distinction between the visual and the verbal, and was transposed into captions for the European magazines aimed at child readers.[31] However, the use of captions under images, whether in verse or prose, reflects more than a rejection of the speech bubble as an American novelty, particularly when practiced in children’s comics.[32]

In Spanish and Italian magazines, speech bubbles in comics were atypical, while (versified) captions stemmed from a tradition of broadsheet and popular press genres such as the Spanish aleluyas or the format of the billboard held up by Spanish and Italian popular story singers (respectively ‘cartelones de ciego’ and cantastorie) at least until the 1930s.[33] The Spanish and Italian rhymed verses are a remediation of the rhythm and verse used as mnemonics by popular singers of sequential board tales on squares (the tradition of the cantastorie still exists today in Italy, although it has been lost in Spain). The octonaries were also extensively used in opera librettos in the cantabile moments of nineteenth‑century melodrama (such as Bellini’s Norma or Verdi’s Trovatore) and singing performances of the café chantant.[34] Most importantly, these formal choices show how the mirliton verse, one of the characteristics of Busch’s Bilderbogen, was maintained even if European children’s publishers acknowledged the economic potential of the comics medium, thus forestalling a full‑fledged formal innovation.

European domesticators of Katzenjammer Kids did not entirely ignore European tradition.We have already given the example of the (rhymed) captions that aimed at a different age group and stemmed from different traditions, but we should also discuss the format of the European magazines, which was considerably smaller than that of the European broadsheets or of the American Sunday pages. Adapting, reforming, and reshaping panels was required to fit stories to a less appropriate publication shape, given that European artists had more or less half the size of their American colleagues.

For example, Corriere dei Piccoli (CdP; also Corrierino), a weekly Italian children’s magazine, published some of The Katzenjammer Kids as one‑page comics and others as two‑page comics on its central pages. By doing either of these changes, largely neglecting the characteristics of the original format, Corrierino altered the page’s rhythm and spatiotemporal effect on the reader. Moreover, by eliminating panels, all balloons, and strictly gridding a pattern of 6 or 8 panels with poetic captions, the bourgeois magazine uncovered its technical shortcomings and ideological reasons, simultaneously induced by and shaping its child readers.[35]

To the best of our knowledge, the first Spanish magazine that published Dirks’ Katzenjammer Kids was, intriguingly, Los Sucesos—not a children’s magazine. According to Antonio Martín, it was a sensationalist weekly on the latest accidents or crimes. Mainly known now for republishing Outcault’s Buster Brown during its almost seven years of life as Juanito y su perro, it added later and with less regularity Dirks’s Katzenjammer Kids and Burr Opper’s And Her name was Maud!.[36] Unfortunately, we have not been able to retrieve any issues containing Los Sucesos Katzenjammer Kids’ adaptations. However, we have examples of their adaptations of Buster Brown, which preserved the balloons in an attempt to remain faithful to the original, even if sometimes panels are omitted.

Balloons were changed to rhymed verses in IlNovellino (1898 –1927) which published an adapted version of Yellow Kid (Bebè, 1901), and domesticated The Katzenjammer Kids and Foxy Grandpa with rhymed text.[37]Novellino’s emphasis on illustration and rhymed captions would inspire Corriere dei Piccoli.[38]

Figure 4

“Chi va per burlare, resta burlato” [Who Mocks, ends up being mocked], Novellino 7, February 11, 1904, cover

Los Muchachos (1912‑1927) was a Madrid‑based magazine addressing the juvenile public which featured comics while marketing itself as a “weekly handing out gifts.” In 1917 it domesticated TheKatzenjammer Kids, using rhymed captions and rhyming titles. An example of such a Katzenjammer copy, “Travesuras de chiquillos o la viuda de Pinillos”, can be found in figure 5. Curiously, the publication of the series in another weekly magazine for children of the 1920s, Pinocho, under the name La tormenta y el ciclón o Hazañas de Tin y Ton (Figure 5), did respect the logic of thespeech balloons and the dialogues. The evident reason for this difference is that while Los Muchachos traced an American original, neglecting the source artist or newspaper and causing big blanks in the first four panels where the balloons used to be, the example from Pinocho does acknowledge, although in admittedly rather minuscule font, the original newspaper in which the Kids were published (in the penultimate panel) and the American creator of TheKatzenjammer Kids (in the last panel). The rhyme is not entirely lost, as the comic features a rhyming couplet (La tormenta y el ciclón/o Hazañas de Tin y Tón [The Storm and the Cyclone or the Exploits of Tin and Ton].

Figure 5

“Travesura de chiquillos o la viuda de Pinillos,” Los Muchachos, May 6, 1917, 3

Figure 6

La tormenta y el ciclón o Hazañas de Tin y Tón, Pinocho, 1930s

Copyright acknowledgements such as the ones above or in some of CdP’s publications reflect an investment of a big budget in publishing comics relying on the vanguard printing technique. For example, Corriere della Sera (the Milanese newspaper publishing the children’s periodical CdP) bought Hoe rotational machines to print in colours on the covers, centre pages, and back covers from the first issue of CdP without limitations to copies.[39] Peruch and Santin further inform that the Milanese newspaper spent 93,000 lire on the first issue of the supplement, dated December 1908, of which 15,119 lire were reserved for the drawings and images. But not all adaptations of Buster Brown, The Newlyweds, The Katzenjammer Kids, and others, acknowledged their American sources or the original artists.

In 1915, TheKatzenjammer Kids ran 23 times out of CdP’s 52 issues but did not mention Dirks, Knerr, or any of the American papers from which they originated. At that time, in its seventh year of publication, CdP had a print run of 174,681 copies (in comparison to 152,836 in 1914). Due to paper shortage, the publicity wrappings were eliminated, and the number of pages diminished from 16 to 14 (and, in 1916, to 12). The war took up a considerable part of the content of 1915.[40] Especially the Italian‑made, domestic comics series were dealing with the ongoing battle. Schizzo, a patriotic series that started in 1914 and was drawn until 1917, is an Italian ‘sequel’ to Little Nemo, by Attilio Mussino. While Nemo dreams of Slumberland, the Italian boy dreams about the war, fighting alongside General Cadorna, or joining Guglielmo Marconi in his invention process, or else making fun of the German general Hindenburg and the emperor Franz Joseph and being honoured by King Vittorio Emanuele III.[41] While bricolaging (borrowing Ian Gordon’s definition) Little Nemo into a propagandistic alter ego meant adapting it to pedagogical ideas and moralistic intentions behind the bourgeois magazine, to Italian style, and to the preferences of its ideal readership, TheKatzenjammer Kids happily continued their mischief in exotic or generic spaces, seemingly unaffected by the local context.[42]

TheKatzenjammer Kids performed their tricks and caused havoc from 21 February of issue 8 of CdP, without any relation to Italian reality or the ongoing conflicts. Even though the series by Italian artist Antonio Rubino were also staged in unrealistic settings or presented in a surreal style, the American series stood further from reality. The episodes were mostly printed on one of the centre pages (p. 6, most commonly), while the Italian series opened and closed the children’s magazine. TheKatzenjammerKids was not the only American series in 1915; the American series The Newlyweds also brought some diversity to the periodical. Where George McManus’s series was about the difficulty of childrearing and the dynamics of a young couple who rarely left their house or the streets surrounding their home, TheKatzenjammer Kids introduced Italian children to a series of racialized stereotypes and exotic surroundings. The first episodes of 1915 (21 February and 28 March, for example) stage the kids with their uncle in a landscape of snow; by June/July/August 1915, they shift to an American setting with stereotypical cowboys and Indians, and then by November 1915 a racial caricature of Asian ethnicity as well.

The force of the American serial figures and the way in which they contemporaneously and seemingly contradictorily stood apart from domestic products while interacting with them is evident from the next strip. On 18 April 1915, Corriere dei Piccoli published a comic with a very remarkable cast (Figure 7). On the one hand there is the local character Schizzo, Little Nemo’s bricolaged Italian twin brother, holding a newspaper and reading “about the great airships that cause such severe damage in combat” (panel 1). On the other hand, there are American characters such as Frederick Burr Opper’s recalcitrant mule Maud and Dirks/Knerr’s The Katzenjammer Kids (Bibì and Bibò) and their captain Cocoricò. In the second panel, captain Cocoricò, wearing a Prussian helmet, is on a great balloon, accompanied by Bibì and Bibò. In panel 3, the domestic character Schizzo appears, and the captions state that he is “very pleased to be holding the rudder/From that helmet intimidated, he steers the boat carefully.” The fourth panel directs the reader’s gaze to one side of the ship, where there is a provision of bombs. The captain commands to throw some bombs out. The fifth panel then prepares the pun; the pile is draped and seems to be hiding Checca (the mule Maud). Captain Cocoricò decides: “It’s a trick by Bibò!, and he raises his hand on the child with the proudest ‘Ohibò!’” (panel 6). The mule Checca points at all three of them and hurls them suddenly overboard (panel 7). The penultimate panel leaves room for the domestic character again, the heroic boy Schizzo, who also throws himself out of the ship to save them. The last scene restores the local character back to his bedroom, which is not the bourgeois room of Little Nemo, but an Italian middle‑class bedroom in an age of war.

The strip plays out a combination of gags from all these series by connecting American gags such as the kicking mule (panel 6), the mischievous Katzenjammers and their retribution from the captain (panel 6), and Little Nemo’s dream (first and last panel) with the Italian context of an informed, heroic boy who reads the newspaper (panel 1), is upset by the Prussian helm (panel 3), and heroically jumps out of the boat to save the three victims. It is worth noting that this was only a month before Italy’s declaration of war (25 May 1915), and the Italian character Schizzo still sympathizes with the character Cocoricò (hence the Prussian helmet and Reichsadler). Corriere dei Piccoli was bringing child readers right into the complexities of warmongering and changing alliances.

Figure 7

Attilio Mussino, Schizzo, Corriere dei Piccoli 16, April 18, 1915, p. 1

This comic exemplifies the effect of domestication on the comics pages. The mash‑up of local and global characters, and the twists to the stereotypical scenarios of these characters by the hand of a local artist, evince the collective process that Brienza points at.[43]TheKatzenjammer Kids, which was already a transcultural construction from its beginnings (Dirks and Knerr borrowing from Busch), evolved through the agency of the Spanish and Italian receiving artists and publishers, thus becoming a multi‑national and ‑directional construct.

Domestication Procedures and Long‑Standing Reception

Verifying what happened 43 years later, when the series had already conquered several generations of readers, is enlightening concerning the preservation and continuity of domestication models. In the pre‑iconographic sense indicated at the beginning of the article, this allows us to verify the cultural survivals (Nachleben) within the series and its modes of reception when the series was a long‑standing tradition in Corrierino’s pages. Unlike the first years, in which the series appeared as a regular feature on the central pages, beginning in 1958 the series ran in nearly every magazine issue on the back cover as a nod to a certain slapstick past. The dialogues are still rewritten, phylacteries are eliminated, and they are transformed into rhyming descriptions or captions as if connecting with the history of the supplement and the traditional fable. In contrast, the supplement contains comics which are much more modern in form, such as Hayawatha by Carlo Porciani e Rinaldo d’Ami or Davide Piffarerio’s Apolo e Apele. When comparing the adaptations in Corrierino with the American publishing cadence of The Katzenjammeer Kids, it appears that there has been a selection of the most gag‑based pages of greater simplicity, as shown by examples such as the Inspector’s trips in CdP 1958‑11 and CdP 1958‑11 or a micro‑story about counterfeiting bills during the characters’ stay in the exotic enclave of Bongo (CdP 1958‑22).

Moreover, a comparison of specific pages shows a clear re‑editing, such as in the case of originals published in 1958 compared to their adaptations in the 1958‑12 CdP, which shows different distributions and the occupation of the entire verticality of the format of the edition. Likewise, the reassembly is evident: vignettes are sometimes missing, and they have been retouched to allow the publishing of another strip at the bottom—such as Yomino: Orazio Coclite e Yomino Salvano Roma (CdP 1958‑4), Yomino e i Lunatici, also rhymed (CdP 1958‑15), Yomino e i quattro prigionieri (CdP 1958‑7), Yomino e i minatori (CdP 1958‑11), Le avventure del Piccolo Lanerossi (CdP 1958‑2, 1958‑13) or even comic‑advertising for the Geloso tape recorders (CdP 1958‑52).

Figure 8

La tormenta y el ciclón o Hazañas de Tin y Tón, Pinocho, 1930’s

Figure 9

Sometimes the text alters the original meaning, gives it another bias, or stresses specific meanings. The clearest instance is the Inspector acquiring a book on children’s educational models (CdP 1948‑13), which seems to fit perfectly with the model and the editorial premises of CdP. In addition to mixing different publication periods, the less complex and mostly gag‑centred pages are often chosen, and the “malice” that the Spanish edition transcribes in Pinocho magazine (Figure 8) seems absent from the Italian edition (CdP 1958‑52).[44]

The contrast is striking in certain cases where during the layout process the editors have decided to leave some labelled posters (CdP 1958‑1, CdP 1958‑49), balloons with onomatopoeia, and even text, despite opting otherwise for the general suppression of balloons for dialogue. In the corpus taken from the year 1958, this happens in number 6, in which the plate of the Katzenjammer Kids occupies the cover (CdP 1958‑06; Figure 9); in number 23, where the children shout against all the disciplines they are forced to study in the first vignette (CdP 1958‑23); in 26 and 29, with the shouts “Aiuto,” “Forza,” and “Eccomi qua” that a character supplicates from a cave (CdP 1958‑26, CdP 1958‑29); and in two onomatopoeias in issues 33 and 34 (CdP 1958‑33, CdP 1958‑34)

The Cultural Significance of the Naughty Twins in Spain, Italy, and the States

The figure of the mischievous child is closely linked to the rise of the bourgeoisie. Before the Modern Age, in the Old Regime, the child was often a burden, an incomplete adult who was made to work or who was given adult responsibilities as soon as possible. (As Pierre de Bérulle expressed it: “Childhoot is the life of a beast”[45] to which Jacques‑Bénigne Bossuet added “The status of childhood is the vilest and abject of human nature after death”[46]. The advent of the bourgeoisie in the eighteenth century coincided with the conception of the infant as an investment and the work of the philosophers Diderot and Rousseau to change everything. If, in Old Regime’s thinking, it is crucial to shape the untamed nature of the child in a slow natural way so as to adapt it to civilized society, Rousseau, by contrast, conceives that nature is intimately good and it is the society that perverts it (as he argues in l’Emile [1762]).

Although popular language, sayings, and songs are lavish in their representation of the figure of the unruly child, the moralizing domestication of traditional tales that authors such as the Grimm brothers produced in the nineteenth century excludes or punishes the figure of the mischievous child who, around the same time, seems to jump into the nascent medium of comics. Max und Moritz is motivated by the same educational purpose that shaped Central European children’s literature and projects such as CdP, whose promoter Paula Lombroso connected with a Rousseauian pedagogy. Perhaps because a very different tradition survived in Spain, that of the picaresque novel, with its urchins trying to survive The Katzenjammer Kids managed to take hold without their phylacteries with rhymed captions, were rebuilt, and were even responsible for inspiring a vast legacy.

In the post‑war devastation of the Spanish Civil War, the comics of the Bruguera publishing house became one of the only spaces to exercise criticism against Franco’s dictatorship and elude censorship. Compared to the indoctrinated children of publications such as Flechas y Pelayos (1938‑1949), or with the heroic Cuto (1935‑1975) drawn by Jesús Blasco—inspired by Alex Raymond, Milton Caniff and Floyd Gottfredson’s work—who embodies the figure of the potential adult and capitalizes on the Francoist regime’s idea of struggle, an anarchic response to order appears in characters such Juan Garía Iranzo’s Perico and Frascales (1951) or, above all, Josep Escobar’s Zipi and Zape (1948). Zipi and Zape were two blonde and dark‑haired brothers inspired in Max und Moritz and TheKatzenjammer Kids. The typical slapstick gag in TheKatzenjammer Kids or in Outcault’s Buster Brown (1902‑1921) and Winsor McCay’s Little Sammy Sneeze (1904‑1906) coexists with an exercise in deprogramming the expectations of law and order of Zipi and Zape’s parents, Mr. Pantuflo and Mrs. Jaimita.

Under the occasional express will to “do good deeds” that pushes Zipi and Zape to boycott the typical day‑to‑day of the house and fight obedient children like Peloto, the series connected, like so many others from the Bruguera publishing house, with the spoken heritage of the society. Sayings, set phrases, traditional expressions, and verbal games inspired by the literary tradition bequeathed by the Spanish Golden Age, from the anonymous El Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) to Guzmán de Alfarache (1599) by Mateo Alemán or even Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605), gave life to the visual plasticity of Bruguera’s series. Curiously, the editions in which Martz Schmidt took Katzenjammer Kids characters like The Inspector as a starting point, like El doctor cataplasma (1953‑1978) and El profesor tragacanto (1959‑1987), placed less emphasis on verbal games and more on slapstick work. But the burlesque tradition that in the German case (and concerning Max and Moritz) would have a more complex assembly with characters like the medieval peasant Till Eulenspiegel, was strongly crystallized in the Spanish case and allowed both an easy fit of The Katzenjammer Kids and the development of series like Zipi and Zape inspired by it.

It is an excellent example of eloquent gaps in cultural domestication that in Italy there was no direct legacy of Max und Moritz and TheKatzenjammer Kids. The great children’s publications such as Corriere dei Piccoli and Corriere dei Ragazzi were first followed by the arrival of Franco‑Belgian comics, where the figure of the mischievous child did exist although with different characteristics—such as Jean Roba’s Boule et Bill (1959)—and, little by little, by the rise of adult and genre publications, such as the Bonelli publishing house’s young and adult‑oriented Western, fantasy, and science‑fiction characters. However, the legacy of the naughty kids might not have been bricolaged into an Italian character, but translated to games and toys of serial figures.

Considering the set of phenomena of variation, domestication, glocalization, and the cultural and historical implications that they embody, it is also possible to argue that the circulation of TheKatzenjammer Kids was particularly rich in phenomena of cultural re‑appropriation. From an iconographic point of view, it generated subtle variations, collages, and even foreshadowed contemporary musical and cinema mash‑ups and the potentiality of cross‑overs in the specific field of superhero comics. TheKatzenjammer Kids were not merely transposed for children’s entertainment. Many children’s weeklies understood that recurring characters, through their carefully timed appearance in the magazine, could create a relation between the child, the periodical, and consumption. One could think of this connection as a parasocial relationship, as the “‘contract’ that Martin Barker has written about was solidified.”[47] The comics characters ensured the comics magazines would be bought. Many covers thus bring together a multitude of characters to announce which characters/series to expect and search for within the ephemeral’s pages. Thus, for example, Popeye was staged with The Katzenjammer Kids in Pim Pam Pum in the 1950s.

Figure 10

“Los dos pilluelos,” Popeye 1, 1948, cover

In some magazines, the abundant casts on these covers would become linked to festivities. Publishers would encourage consumerism by staging these serial figures. The sheer abundance of heroes in Christmas or Easter instalments celebrate the lavishness of festivities. The reader is invited to share in that abundance. National boundaries no longer count when, for example, on 4 April 1915, the Newlyweds’ baby Snookums, TheKatzenjammer Kids, and the kids from Happy Hooligan appear with their Italianized names alongside Pinocchio (Figure 11).

Children reading the magazine would have recognized these characters. Panels such as these loyalize and seduce the reader of Corriere dei Piccoli, and are also turned to advertising, as when promoting a typical ‘health commodity’ of the time through a narrative featuring a group of CdP stars. The characters must leave their small domestic home (not coincidentally “Corriere dei Piccoli”) because, thanks to drinking Eutrofina, they grow so much that they have to build a larger home. This sequence reminisces the fairy tale of TheThree Little Pigs. It shows the benefits of Eutrofina, appeasing even the most incorrigible boys while also literally imagining the place CdP’s characters took in children’s imagination.

Figure 11

Nasica, Corriere dei Piccoli 14, April 4, 1915, p. 12

In the same year of this Eutrofina advertisement, in the last episode of the Katzenjammers (26 December 1915), the Katzenjammer Kids put up their socks for Santa Claus.

Figure 12

The Katzenjammer Kids, Corriere dei Piccoli 52, December 26, 1915, p. 6

This comic visualizes an important change in Christmas imagery. While in the first few years of CdP’s publication the periodical still used the common image of the holy child bringing gifts, by 1915, not only the American comics characters but also those of powerful, commodifying figures such as Santa Claus had established themselves internationally.[48]

In contrast to Corriere dei Piccoli, TBO neither used a lot of fixed or international characters, nor did it carry any advertising for other products.[49] The following example exposes a failure to use serial figures for serial marketing. The in‑house advertisement cartoon anonymizes the two Katzenjammer Kids and decontextualizes them to promote TBO’s annual.[50] All three characters say the same thing: one needs to hurry if one wants to read the 1923 annual because the copies have almost sold out. The Katzenjammer Kids have little to do with their original universe. Moreover, they were de‑serialized in TBO and completely unknown as serial figures to TBO’s reader. They are “synthetic forms that can be declined on all media” but are anonymized instead of named to promote TBO’s in‑house publications.[51]

Figure 13

The invention of new consumption logics, the direct appeal to the visual memory of the reader, and the adherence to the series as an enhancer of unique formulas of exploitation and loyalty devices outline The Katzenjammer Kids as one of the determining series in the history of the modes of reading and reception in the history of comics. Even when they perpetuated eternal gags—Happy Hooligan and the Katzenjammer Kids performed numerous viral gags that today would doubtless become memes on social networks[52]—these characters progressively spread outside the newspaper from which they originated. The success of the serial figure in children’s products only highlights the “copyrightability” of the Katzenjammers and the medium’s reliance on repetition mechanisms and consumerism.[53]

This article is an outcome of the COMICS project funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 758502)

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Eva Van de Wiele is a postdoctoral researcher on the ERC project COMICS at Ghent University. She investigates the ways in which children’s comics magazines script their readers’ behaviour. Her corpus consists of French-language comics from the 1930s to the 1960s contained in the Alain Van Passen Collection. She is Member of the Editorial Board of Open Access Journal Comicalités. She is Management Committee Member of the COST iCOnMiCs Action. She is also a member of the 20cc research group, the network of A Girl’s Eye View, ACME and of an early-career research group on Italian comics, SnIF. She reviews and writes about comics for 9ekunst.nl and Pulpdeluxe.be. She teaches as a guest lecturer at LUCA School of Arts Brussels.

Ivan Pintor Iranzo: PhD in Communication Studies from Universidad Pompeu Fabra (UPF). Senior lecturer at UPF and member of the CINEMA Research Group. He currently teaches History of Comic Book and Contemporary Cinema in the Bachelor’s program in Audiovisual Communication at UPF, and Cinema, TV and Comic-Book History in the UPF Master’s in Contemporary Film program. He is the Principal Investigator of the research project Mutations of Visual Motifs in the Public Sphere:Pandemic, Climate Change, Gender Identities (MUMOVEP), and has been the Project Manager in Spain of the Erasmus + Project Teseo – Arianna’s Strands in the Digital Age. In recent years, he has published books like Figure del fumetto (2020), articles in journals and chapters in more than 60 books, including Penser les forms filmiques contemporaines (2022), L’Immaginario di Stranger Things (2022), Les Motifs au cinema (2019), and I riflessi di Black Mirror (2018). He writes at the newspaper La Vanguardia and has curated exhibitions for different museums. His areas of research are film studies, comic studies, iconology, comparative media studies, and transmedia.

Notes

-

[1]

Casey Brienza, Manga in America: Transnational Book Publishing and the Domestication of Japanese Comics (London; Oxford; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 38.

-

[2]

Welcome exceptions are: Mel Gibson’s Remembered Reading (2015), and Carol Tilley’s research on comics and reader response such as “Children and the Comics: Young Readers Take on the Critics” (in Protest on the Page: Essays on Print and the Culture of Dissent since 1865, ed. James L. Baughman et al. [University of Wisconsin Press, 2015], 161–182.

-

[3]

Benoît Glaude, La bande dialoguée: une histoire des dialogues de bande-dessinée (1830-1960) (Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2019), 201.

-

[4]

Wheeler, Doug, Robert Beerbohm, and Leonardo de Sá, “Töpffer in America”, St. Louis: Comic Art, 2003, n. 3.

-

[5]

Bill Blackbeard and Martin Williams, eds, The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977), 19. Ian Gordon has shown that the Katzenjammer Kids travelled to Australia, where they incarnated in the weekly magazine The Comic Australian (1911-1913) as outlaws in the Australian bush in a one-off comic strip, Jim and Jam, Bushrangers Bold (Kid Comic Strips: A Genre Across Four Countries [New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016], 5)

-

[6]

Glaude, La bande dialoguée, 205.

-

[7]

Brienza, Manga in America, 38.

-

[8]

Aby Warburg, The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity (Los Angeles: Getty Institute, 1999); Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939).

-

[9]

We use the term “bricolaging” to refer to the high level of adaptation by local markets, as used by Ian Gordon in his talk “Chiquinho: Brazilian Buster Brown or Bricolage” during the Transnational Insights into Comics Day held at Ghent University on 30 September 2022. Gordon borrows the term from Casey Brienza and Paddy Johnston’s volume Cultures of Comics Work (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

-

[10]

Dirks had an assistant helping him draw the Kids (Oscar Hitt), and from 1924 other artists would draw the Katzenjammers for Hearst such as Frederick Burr Opper, Gus Mager and Harold Knerr, Hi Eisman (1949). Dirks’ son John introduced big changes in 1968.

-

[11]

See http://web.tiscali.it/epierre/storia/stocorr2.html for an interesting summary of all domesticated characters in CdP.

-

[12]

Spanish periodicals which published The Katzenjammer Kids in one form or another included Los Sucesos, Muchachos, 1920s Pinocho, 1940s Centurias, 1950s Jaimito, Pim Pam Pum, 1970s Carlitos y los Cebollitas, and finally 1980s TBO’s Ediciones B.

-

[13]

Fabio Gadducci, Notes on the Early Decades of Italian Comic Art (San Giuliano Terme: Felici Editore, 2006), 14.

-

[14]

Gadducci notes that the translation of Busch’s The Fly was repeated by Perino in Il Giornale Illustrato per I Ragazzi (no. 22, April 22, 1886); for an example of the German original see Wilhelm Busch, DieFliege, Münchener Bilderbogen 425, or visit http://dardel.info/Textes/Die_Fliege.html.

-

[15]

In this sense, it is revealing to verify that the first cinematographic fiction in history, L'Arroseur arrosé (1895), by the Lumière brothers, is already an adaptation of a 1889 Christophe’s (George Colomb) strip, a gag that in turn comes from Wilhelm Busch and recurs in the Katzenjammer Kids (Rudolph Dirks, January 21, 1900, American Humorist, New York Journal Sunday Supplement), and in many others comics and films. See Ivan Pintor, Figuras del cómic. Forma, tiempo y narración secuencial (Valencia-Barcelona: Aldea Global, 2017), 127.

-

[16]

Pascal Lefèvre “Of Savages and Wild Children: Contrasting Representations of Foreign Cultures and Disobedient White Children During the Belle Epoque,” in The Child Savage, 1890-2010: From Comics to Games, ed. Elisabeth Wesseling (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2016), 60.

-

[17]

Lefèvre, “Of Savages and Wild Children,” 63.

-

[18]

David Kunzle, The History of the Comic Strip: The Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 249.

-

[19]

“Le jeu sur les paramètres sociolinguistiques des Katzenjammer Kids provient certainement du modèle buschien, même s’il ne remplit plus la même fonction dans la grande presse américaine. Chez Busch, les variations de style sociolectales et le jeu sur les registres de l’allemand standard, dans les passages en discours direct, dénotent une prise de distance critique à l’égard des personnages adultes. Quant à ceux de Dirks, enfants ou adultes, ils parlent tous un anglo-américain non standard, mâtiné d’un fort accent allemand.” Authors’ translation. Glaude, La bande dialoguée, 203.

-

[20]

“Supprimé dans les traductions françaises, par ailleurs d’une platitude navrante.” François Cavanna, “Quelques mots,” in Wilhelm Busch, Max und Moritz avec Claque-du-bec & Cie, trans. François Cavanna (Paris: L’École des Loisirs, 2012), 9.

-

[21]

Thierry Smolderen, Naissances de la bande dessinée (Bruxelles: Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2009), 97.

-

[22]

Smolderen, Naissances, 97.

-

[23]

We are referring to Joe Sutliff Sanders’ concept of chaperoning which states that texts for younger readers, such as picture books, actually offer a chaperoned reading experience which is “guarded” by an adult or an older sibling who each make selections or put accents while reading aloud to the younger child. Comics, on the contrary, offer children more easily the enjoyment of solitary reading, even when written, drawn and published by adults, as they mark(ed) a venue in which children as emerging readers and subjects operate with more meaning-making autonomy. Comics with captions should be seen as a middle-way between these two formats: reducing the child’s reading autonomy, while nevertheless offering chances for solo-reading.

-

[24]

Lefèvre, “Of Savages and Wild Children,” 205-206.

-

[25]

Gino Frezza, “Subversión y reinvención,” Tebeosfera, 11 June 2017, https://www.tebeosfera.com/documentos/subversion_y_reinvencion.html.

-

[26]

Frezza, “Subversión y reinvención.”

-

[27]

While “caracoles,” which literally means “snails,” is not an expression in use today, it was common in the first half of the 20th century, as has been attested by comics, zarzuela or operetta, and popular newsstand novels.

-

[28]

Eva Van de Wiele, “Domesticating and Glocalising the Dreamy: McCay’s Little Nemo and Its Sequels in Early Italian Corriere Dei Piccoli (1909-1914),” Interfaces 46 (2021): .

-

[29]

Glaude, La bande dialoguée, 201.

-

[30]

Pascal Lefèvre, “The Battle over the Balloon. The Conflictual Institutionalization of the Speech Balloon in Various European Cultures,” Image & Narrative 14 (2006), http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/painting/pascal_levevre.htm.

-

[31]

Pascal Lefèvre and Charles Dierick, ed., Forging a New Medium. The Comic Strip in the Nineteenth Century (Bruxelles: VUB University Press, 1998), 20.

-

[32]

Eva Van de Wiele, “L’impact des légendes versifiées sur l’histoire de la bande dessinée espagnole (1900-1970): Parcours à travers les histoires en images des magazines espagnols pour enfants,” Textimage 15 (2022).

-

[33]

For more information on the comics’ heritage in Spain see Mercedes Chivelet, ¡Menudos lectores! Los Periódicos que leímos de niños (Barcelone, Espagne, 2001), 18; José Altabella, Las Publicaciones infantiles en su desarrollo histórico (Madrid: Editora Nacional, Ministerio de Información y Turismo, 1964), 6-8; Paco Baena, Tebeos de Cine. La Influencia Cinematográfica En El Tebeo Clásico Español, 1900-1970 (Barcelona: Trilita Ediciones, 2017), 24. For a detailed overview of early children’s comics in France, see Annie Renonciat, “Les Imagiers européens de l’enfance,” in Maîtres de la bande dessinée européenne, ed. Thierry Groensteen (Paris: Seuil, 2000), 45.

-

[34]

We know this thanks to Lorenzo Di Paola, who traced the history of rhymes in his lecture on CdP on 31 March 2022 at Ghent University.

-

[35]

Giovanna Ginex, Corriere dei Piccoli: storie, fumetto e illustrazione per ragazzi (Milano: Skira, 2009), 44.

-

[36]

Antonio Martín, “La historieta española de 1900 a 1951,” Arbor 187 (2011): 64.

-

[37]

Gadducci, Notes, 16.

-

[38]

Pino Boero and Carmine De Luca, eds. La letteratura per l’infanzia (Roma: Laterza, 2009), 79.

-

[39]

Camilla Peruch and Sonia Santin, eds. Il Corriere dei Piccoli va alla guerra (Vittorio Veneto: Kellermann, 2015), 16.

-

[40]

Peruch and Santin, Il Corriere dei Piccoli, 17.

-

[41]

Peruch and Santin, Il Corriere dei Piccoli, 27.

-

[42]

The approach of making the war speak to children by opting for heroic child protagonists was repeated in other series as well. Though in a more surreal style, Antonio Rubino’s series Luca Takko is a fictionalised account of the Austrian-Serbian war, in which the two fictive countries Ucraina and Selvonia confront a crisis that separates Luca Takko from his best friend Gianni (Peruch and Santin, Il Corriere Dei Piccoli, 33). Rubino’s other series in 1915, Italino, is a nationalist propaganda series featuring an Italian boy living in the so-called “territori irredenti,” the confined region of Italy that belonged to Austria (Peruch and Santin, Il Corriere Dei Piccoli, 42–43). The titular character Italino invented pranks and acted mischievously against the Austro-Hungarian forces, personified by the fat Austrian Archduke Otto Kartoffel and his daughter Kate, out of “irredentism.” Finally, Toffoletto Panciavuota (the protagonist’s surname is “the empty bellied”) was a series by Gustavino (Gustavo Rosso) that ran only in 1915, and featured an elderly man representing charity and generosity.

-

[43]

Quoted at the beginning of this article: “what it does is not merely textual translation from one language to another or straightforward importation of objects from one country to another – but rather a complex, organized, collective process” (Brienza, Manga in America, 38).

-

[44]

See material available online at oldsundaycomics.com, which indicates that in 1958 CdP published pages from different years of the forties and fifties original edition.

-

[45]

Pierre de Bérulle, “Fragment sur la brièveté de la vie (Oeuvres complètes. Paris: Lachat, 1863, t. IX), 374.

-

[46]

Jacques Bénigne Bossuet, Oeuvres completes (Paris: éd. Migne, col. 1007); Apud. H. Bremond, Histoire littéraire du sentiment religieux en France, t. III, IIIe partie, ch. 1, § 2 (Paris: Colin, 1967), 206.

-

[47]

Roger Sabin, “Ally Sloper : The First Comics Superstar?” Image & Narrative 7 (2003).

-

[48]

Two examples are Mussino’s comic of 28 December 1908 with the holy child (no. 1, p. 8) and the Bianchi advertisement on 14 December 1913 in which the holy child brings bicycles to the children of Italy (no. 50, p. 1).

-

[49]

TBO used cinema personalities for some comics series, and created two mascots for the male and female supplement, the boy TBO and the girl BB.

-

[50]

Billboards such as these, especially on the miscellaneous page, were the fixed location where the magazine consistently marketed TBO products. The adverts on the cartoon page (De todo un poco) promoted either annuals (almanaques) or the female supplement BB – i.e., other publications from the same publisher.

-

[51]

Matthieu Letourneux, Fictions à la chaîne: Littératures sérielles et culture médiatique (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2017), 407.

-

[52]

Gordon, Kid Comic Strips, 7.

-

[53]

See Shawna Kidman, Comic Books Incorporated : How the Business of Comics Became the Business of Hollywood (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2019), 21; Benoit Crucifix, “Plagiat,” in Le bouquin de la bande dessinée: Dictionnaire esthétique et thématique, ed. Thierry Groensteen and Lewis Trondheim (Bouquins. Paris: Robert Laffont, 2020), 580; Gordon.

Bibliography

- Altabella, José. Las publicaciones infantiles en su desarrollo histórico. Madrid: Editora Nacional, 1964.

- Baena, Paco. Tebeos de cine: La influencia cinematográfica en el tebeo clásico español,1900-1970, Barcelona: Trilita Ediciones, 2017.

- Blackbeard, Bill, and Martin Williams, eds. The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977.

- Boero, Pino, and Carmine De Luca, eds. La letteratura per l’infanzia. Roma: Laterza, 2009.

- Brienza, Casey. Manga in America: Transnational Book Publishing and the Domestication of Japanese Comics. London; Oxford; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

- Brienza, Casey, and Paddy Johnston, eds. Cultures of Comics Work. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Busch, Wilhelm. Max und Moritzavec Claque-du-bec & Cie. Translated by François Cavanna. Paris: L’École des Loisirs, 2012.

- Chivelet, Mercedes. Menudos lectores! los periódicos que leímos de niños. Madrid: Espasa, 2001.

- Crucifix, Benoît. “‘Plagiat’.” In Le bouquin de la bande dessinée: Dictionnaire esthétique et thématique, edited by Thierry Groensteen and Lewis Trondheim, 579–83. Bouquins. Paris: Robert Laffont, 2020.

- Frezza, Gino. “Subversión y reinvención,” Tebeosfera, June 11, 2017. https://www.tebeosfera.com/documentos/subversion_y_reinvencion.html.

- Gadducci, Fabio. Notes on the Early Decades of Italian Comic Art. San Giuliano Terme: Felici Editore, 2006.

- Ginex, Giovanna. Corriere dei Piccoli: storie, fumetto e illustrazione per ragazzi. Milano: Skira, 2009.

- Glaude, Benoît. La bande dialoguée: une histoire des dialogues de bande dessinée (1830-1960). Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2019.

- Gordon, Ian. Kid Comic Strips: A Genre Across Four Countries. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Kidman, Shawna. Comic Books Incorporated: How the Business of Comics Became the Business of Hollywood. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2019.

- Kunzle, David. The History of the Comic Strip: The Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Lefèvre, Pascal. “Of Savages and Wild Children: Contrasting Representations of Foreign Cultures and Disobedient White Children During the Belle Epoque.” In The Child Savage, 1890-2010: From Comics to Games, edited by Elisabeth Wesseling, 55–70. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2016.

- Lefèvre, Pascal. “The Battle over the Balloon. The Conflictual Institutionalization of the Speech Balloon in Various European Cultures.” Image & Narrative 14 (2006). http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/painting/pascal_levevre.htm.

- Lefèvre, Pascal, and Charles Dierick, eds. Forging a New Medium: The Comic Strip in the Nineteenth Century. Bruxelles: VUB University Press, 1998.

- Letourneux, Matthieu. Fictions à la chaîne: Littératures sérielles et culture médiatique. Poétique. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2017.

- Martín, Antonio. “La Historieta Española de 1900 a 1951.” Arbor 187 (2011): 63–128.

- Nord, Christiane. “Proper Names in Translations for Children: Alice in Wonderland as a Case in Point.” Meta 48, nos. 1–2 (Sept. 2003): 182–96.

- Peruch, Camilla, and Sonia Santin, eds. Il Corriere Dei Piccoli va Alla Guerra. Iteranda 16. Vittorio Veneto: Kellermann, 2015.

- Pintor, Ivan, Figuras del cómic. Forma, tiempo y narración secuencial. Valencia-Barcelona: Aldea Global, 2017.

- Panofsky, Erwin, Studies in Iconology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Renonciat, Annie. “Les Imagiers Européens de l’Enfance.” In Les maîtres de la bande dessinée européenne, edited by Thierry Groensteen, Paris: Seuil, 2000, 36–47.

- Sabin, Roger. “Ally Sloper : The First Comics Superstar?” Image & Narrative 7, 2003.

- Sanders, Joe Sutliff. A Literature of Questions: Nonfiction for the Critical Child. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

- Smolderen, Thierry. Naissances de la bande dessinée. Bruxelles: Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2009.

- Tournier, Michel. The Mirror of Ideas. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

- Van de Wiele, Eva. “Domesticating and Glocalising the Dreamy: McCay’s Little Nemo and Its Sequels in Early Italian Corriere dei Piccoli (1909-1914).” Interfaces 46 (2021).

- Van de Wiele, Eva. “L’impact des légendes versifiées sur l’histoire de la bande dessinée espagnole (1900-1970): parcours à travers les histoires en images des magazines espagnols pour enfants.” Textimage 15 (2022).

- Wheeler, Doug, Robert Beerbohm, and Leonardo de Sá, “Töpffer in America”, St. Louis: Comic Art, 2003, n. 3.

- Warburg, Aby. The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity. Los Angeles: Getty Institute, 1999.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Historietas ilustradas. Guillermo Busch, Barcelona: C. Verdaguer, 1881

Figure 4

Figure 5

“Travesura de chiquillos o la viuda de Pinillos,” Los Muchachos, May 6, 1917, 3

Figure 6

La tormenta y el ciclón o Hazañas de Tin y Tón, Pinocho, 1930s

Figure 7

Figure 8

La tormenta y el ciclón o Hazañas de Tin y Tón, Pinocho, 1930’s

Figure 9

Figure 10

“Los dos pilluelos,” Popeye 1, 1948, cover

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

10.7202/006966ar

10.7202/006966ar