Résumés

Abstract

Topical structure in news translation has received relatively little attention despite its stated significance in discourse content and in producing functionally adequate translations. Journalists write news stories with a given structure, order, viewpoint and values, which are “transferred” in translation and affect the way topics are organized. This study explores how shifts in topical development in translation influence rhetorical structure and ultimately news content. Using Lautamatti’s Topical Structure Analysis and Bell’s Event Structure Model, the paper describes the translation strategies applied in (re)producing the source text’s topical and event structures in the target language in a corpus of Hungarian–English news texts (the summary sections of analytical news articles). Results show that while translators generally preserve the sources’ structure in translation, in some cases (e.g. sequential topic progression) significant changes occur, altering the status of some information as well as the event structure, thus producing modified news contents. The paper also examines whether the claim that news translation is influenced by norms similar to those regulating news production more generally applies to this news genre, too. Findings suggest that due to the stereotypical features of this genre, the data only partially support this claim.

Keywords:

- news discourse,

- topical structure,

- event structure,

- text genre,

- shifts of translation

Résumé

La structure topique a été relativement peu abordée dans le cadre de la traduction des nouvelles, malgré l’importance qu’on lui connaît en termes de contenu du discours et d’adéquation de la traduction sur le plan fonctionnel. Les journalistes rédigent selon une structure, un ordre, un point de vue et un système de valeurs déterminés, autant d’éléments qui sont transférés dans la traduction et qui ont une influence sur l’organisation des topiques. Le présent article porte sur la façon dont le développement des topiques dans la traduction influence la structure rhétorique et, finalement, le contenu des nouvelles. Se fondant sur l’analyse de la structure topique modélisée par Lautamatti ainsi que sur le modèle de la structure événementielle de Bell, le présent article décrit les stratégies de traduction utilisées pour (re)produire la structure informationnelle et événementielle du texte source dans la langue cible. L’étude fait appel à un corpus bilingue hongrois-anglais constitué par des résumés d’articles analytiques. Les résultats montrent que, malgré le fait que les traducteurs conservent généralement la structure du texte source dans leur traduction, il arrive parfois que des changements majeurs surviennent (par exemple, dans la progression des informations). Ces modifications transforment le statut de certaines informations et la structure événementielle et donc, par conséquent, le contenu des nouvelles. Nous soulevons également la question de savoir si l’assertion selon laquelle la traduction des nouvelles est influencée par des normes semblables à celles qui régulent leur production s’applique à ce genre textuel. Selon nos données, cette assertion est partiellement appuyée, probablement en raison de ses caractéristiques particulières.

Mots-clés :

- discours des nouvelles (actualités),

- structure topique,

- structure évenementielle,

- genre textuel,

- déplacement traductionnel

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Our globalized world and the requirements of the information society place the media and within that news translation in the limelight and put special constraints on the work of the translator. The critical examination of news as discourse has been in the focus of attention over the last 30 years (for an overview, see Holland 2006: 230), and a similar increase of interest may be observed in the study of translating news discourse. Research shows differences in the degree to which the translations of news stories depend on their sources: some translations completely alter the information contents of their sources, producing “significantly different local versions” (Bielsa and Bassnett 2009: 72), while others depend strongly on their originals (Valdeón 2005: 215), producing almost identical target language versions. While considerable amount of research is available on identifying and describing stereotypical translation strategies that accompany news translation, the actual reasons that motivate these (such as certain generic norms, text building strategies) have received scant attention.

This paper deals with the (re)creation of topical structure in the translation of news discourse.[1] Four problems motivate the investigation:

the limitations of research on translating information structure[2] and, within that, topical structure;

conflicting opinions in the literature regarding the translation of topical structure;

the complex nature of news translation;

the special norms regulating news translation.

As for the first problem, an extensive body of research has been produced on various aspects of translating thematic and information structure. However, albeit a few exceptions (e.g. Gerzymisch-Arbogast, Kunold et al. 2006; Hatim and Mason 1990; Taylor 1993; Valdeón 2009; Ventola 1995), the bulk of this work focuses on the level of the clause or the sentence and does not go beyond sentence boundaries to account for any textual motivation of thematic and information patterning. In a functional approach to translation (Nord 1997; Reiss and Vermeer 1984), a discourse-oriented view is essential so that links may be established between particular aspects of structure and genre conventions.

The second problem is that conflicting opinions appear in the literature on the translation of information/thematic structure, more precisely, on the effects of retaining or transforming the source structure in translation. The adjectives used to describe the outcomes of translations either altering or retaining the source structure are equally negative and suggest that a bad text is created both ways. Fawcett, for example, claims that if the source text (ST) information structure is retained in the target text (TT), “antiquated structures” (Fawcett 1997/2003: 86) and “clumsy translations” (Fawcett 1997/2003: 90) are produced. If the opposite happens, that is, if the ST structure is altered, Ventola, for instance, finds that in the TT “cumbersome” texts are created (Ventola 1995: 91).

There is also little agreement regarding whether to retain or to transform the information/thematic structure of the ST in translation. For example, Fawcett’s (1997/2003: 86) initial reasoning suggests that the information structure should be kept constant in translation, even if it mars the quality of the translation:

[i]f we wanted to get the same information flow in English, and discussions of the subject in translation theory tend to assert that we do, then we might have to use a variety of what are actually quite difficult and unusual structures such as the passive (John is loved by Ann.) or so-called clefted structures involving splitting devices such as It is X who … or What X did was to … . [This often produces] bad translations using a rather antiquated structure.

Fawcett 1997/2003: 86

Later in his paper he weakens this claim to propose that “rather than seeing sentence structure simply in terms of Theme–Rheme, Given–New or Topic–Comment, translators need to be aware of a hierarchy of semantic weighting of information in and between sentences and the function it serves” (Fawcett 1997/2003: 87). He concludes that information structure should not at all be kept at all costs.

Rogers (2006) also studied what happens in translation where the information structure of the ST is not/cannot be carried over from source to target language on a sentence-by-sentence basis. Her conclusions are in line with Fawcett’s reasoning, as she found that “changes in perspective in translation does not necessarily disrupt the communicative build-up in the target-text sentence” (Rogers 2006: 29).

The outcomes of Limon’s (2004: 62) analyses of Slovene–English translation show that the translator’s work is not sufficiently informed by an awareness of the different ways in which information structure is handled, which often results in an unsystematic approach: sometimes the original word order is retained, with the result that the reader is presented with a marked but communicatively unmotivated New–Given pattern; in other cases the original word order is altered, even though retaining it would have made the processing of the text much easier. In a similar vein, Zhu, based on a systematic analysis of intra-sentential thematic structure and inter-sentential coherence in textual organization, argues that “what text linguistics alerts the translator to should be the necessity and possibility of more purposive and rigorous thematic management in a sentence as a textual unit” (Zhu 2005: 326).

The third motivation for analyzing the behavior of information structure in news translation is the complex nature of this translation type. News translation is a composite of various levels of mediation[3] and as such is produced under multiple constraints. In news translation, mediation occurs at two distinct levels:

between source(s) of information and target readership, producing the (source language) news text, accompanied by several editorial techniques and strategies (Bell 1991; Fairclough 1995; Valdeón 2005);

between languages/cultures, producing the TT, accompanied by a number of translational techniques and strategies (Chesterman 1995; Hatim and Mason 1990; Toury 1995; Valdeón 2005).

Finally, the fourth motivation for studying the link between topical organization and text type/genre lies in the assumption voiced extensively in recent research, namely that news translation is different from any other type of translation as it is influenced by norms similar to those regulating news production (journalism) more generally (Bielsa 2010; 2007). There is considerable evidence (e.g. Bielsa and Bassnett 2009; van Doorslaer 2010; Gottlieb 2010; Valdeón 2010) to suggest that the translation of certain news genres involves various kinds of transformations, modifications in the (informative) contents of news stories (e.g. change of title and lead, elimination of unnecessary information, addition of background information; Bielsa and Bassnett 2009: 64), thus requiring special skills on the part of the translator. The news genre under scrutiny here (the analytical news article) differs in important ways (Section 3.2) from the news stories analyzed in research so far, therefore it provides an adequate basis for the further testing of the above assumption.

This paper reports on the results of a thorough textual analysis involving quantitative and qualitative investigations of various aspects of the topical and generic structures of source texts and translations to:

reveal how topics shift and relate to discourse topic in source and target texts;

identify any systematic connections between the way the event structure and the topical structure of news stories unfold and relate to each other in translation;

formulate tentative suggestions regarding the problems of research discussed above.

The study combines two lines of research within Translation Studies. On the one hand, it builds upon genre-oriented translation research (as conceived by Bhatia 1997) and intends to gain a deeper understanding of the translation of news discourse. On the other hand, by selecting the case of Hungarian–English translation (two very different language systems), and by focusing on topical structure, the paper also informs text-oriented translation research (as conceived in Hatim and Mason 1990). Continuing the work represented, among others, by Gallangher (1993: 152) and Fawcett (1997/2003: 89-90), it attempts to contribute to settling the debate in the literature regarding what it is that really matters in translating the topical structure of news stories: the question of (a) keeping or changing the source structure, or (b) considering the role of other (e.g. genre-related) factors before deciding about the right strategy to pursue.

2. Theoretical background

The forthcoming sections review the most important findings of research on the stereotypical characteristics of translating news, as a special type of translation, and the relevant outcomes of the study of information, thematic and topical structure to account for the relevance of a systematic analysis of topical structure in news translation that is not constrained merely to the clause or the sentence, but extends to text level.[4]

2.1. Translating news

2.1.1. The generic characteristics of news stories

Bell’s (1991; 1998) work on the discourse structure of the news story has been influential in the identification of the generic characteristics of the genre. News stories have been shown to mainly consist of three key components:

attribution (news agency, journalist’s by-line);

abstract (headline and lead);

story (episodes and events).

Within the story, events contain several moves: attribution, actors, action, setting, follow-up (action after main event), commentary (the journalist’s or news actor’s observations and evaluative comments on, or expectations of the events, which may provide context to help readers understand the news story), and background (consisting of verbal reaction by other parties, or non-verbal consequences; covers any action after the main action of the event).

Besides discourse structure, Bell also describes the chronological structure of the news event and provides a comparison of the two. He asserts that temporal sequence is usually not followed in news reports; instead they tend to be organized according to perceived news value, such as recency or immediacy, negativity, proximity, etc. Thus in news, discourse organization can be of two types:

discourse structural, organized in terms of perceived news value (characterizing news stories);

chronological/temporal, organized in terms of time sequence (characterizing the news event[s][5]).

Renkema (2004) pursues a somewhat different approach to the study of media discourse and proposes a more complex framework of analysis. He considers media discourse analysis an “extended stylistic analysis” that involves “the study of content (which topics are selected or excluded), the structure (what is put in the lead of a story and what kind of information is located at important places […]), and the wording: the structuring of the information and lexical choices” (Renkema 2004: 267; the emphases are mine).

The current investigation combines the two approaches by simultaneously exploring news content (through event structure) and aspects of discourse (through topical structure) to argue for a textual (generic) motivation of translation method. Such a combined approach is necessitated by the very nature of the corpus under scrutiny here: the analytical news article. Using Reiss’s (2000) typology, this genre falls into the category of content-focused texts, where the descriptive function is dominant. Such texts require “invariance in transfer of their content” (Reiss 2000: 30) and the translation method is selected accordingly. She claims that in selecting the translation method “[t]he target language must dominate, because in this type of text the informational content is most important, and the reader of the translation needs to have it preserved in a familiar […] linguistic form” (Reiss 2000: 31). The present analysis reveals the extent to which such target-language orientation can be realized in the case of this kind of news genre.

2.1.2. Translating news as a special form of translation

The stereotypical characteristics of translating news have been studied from several angles, focusing on:

language-pair-specific considerations;

the special role(s) of the news translator and the translation strategies resulting from these roles;

particular components of the discourse structure of news stories (e.g. titles, headlines, leads);

various, suprasentential aspects of complete news texts (e.g. logical structure, thematic structure, ideology).

In language-pair-specific research, considerable amount of work involves the English language, for instance analyses focusing on English–Spanish (Valdeón 2005), English–Greek (Sidiropoulou 1995a; 1995b; 1998), Korean–English (Lee 2006), Indonesian–English (Holland 2006), or on comparing translations in English, German, French and Spanish (Nord 1995). Hungarian-related research, on the other hand, is scarce and limited in scope. French–Hungarian translation has received some attention: studies deal with the translation of conceptual metaphors in political news articles (Harsányi 2008; 2010) and with authorial presence through the study of metadiscourse (Paksy 2005; 2008). Pásztor Kicsi’s (2007) work studies news articles translated from Serbian into Hungarian and offers a comparative, quantitative analysis of source and target language sentence structures. In view of the Hungarian–English language pair, little is known about the stereotypical characteristics of news translation. Although Károly’s (2010) study deals with news discourse translated from Hungarian into English, her main concern is the analysis of the discoursal role of lexical repletion (i.e. how shifts in repetition in translation trigger shifts in text meaning) and not the special conditions that regulate news translation.

The outcomes of research on the characteristics and strategies of the news translator suggest that the news translator has a complex role. Vidal (2005: 386, cited in Bielsa 2007: 137) argues that “[t]he news translator is, maybe because of the nature of the medium in which she writes, a recreator, a writer, limited by the idea she has to recreate and by the journalistic genre in which her translation has to be done.” From this it follows that the special nature of this form of translation requires skills that raise the status of news translation from simple text reproduction to creative production and thus transforms the translator into a target language author.

In order to enhance the relevance of the news story and to produce a target language text that harmonizes with the background knowledge of the target reader, the ST is often modified in translation both in content and form. The most frequent types of textual intervention include change of title and lead, elimination of unnecessary information, addition of background information, change in the order of paragraphs, and summarizing information (Bielsa 2007: 142-143).

Due to the wide range of possible interventions, research is frequently narrowed down to the analysis of particular components of the discourse structure of news stories rather than focusing on the whole of the text. The majority of this work concentrates on titles and headlines as these elements carry an important discourse function (indicating discourse theme and main message). Sidiropoulou (1995b), for instance, analyzes headlining in translation, comparing 100 translated article headlines in the Greek press to their originals in the English press. She shows that the cognitive, cultural and social constraints on headline formation produce a higher degree of directness in the Greek versions of the corpus and differences with respect to thematic preferences. In Greek, the quantity and quality of information to be included in the headline differs: she claims that “the quantity of information relates to the genre the article belongs to and the difference in quality is a result of a different ‘macro-rule’ application” (Sidiropoulou 1995a: 285).

Nord (1995) looks at titles and headlines as “text types” in their own right that serve six different functions: distinctive, metatextual, phatic, referential, expressive, and appellative function. In a corpus of German, French, English and Spanish titles and headings, she explores their communicative functions, the culture-specific and genre-specific ways in which these functions are verbalized, and the culture-specific structural conventions determining the textual design of titles in general and of the six title-genres in particular (Nord 1995: 262). Based on the results of her analyses, she proposes a functional hierarchy in titles and headings, divided into two main groups, namely the essential functions (including the distinctive, metatextual, and phatic function) and the optional functions (containing the referential, expressive, and appellative function).

Another component of news reports with an outstanding discourse function is the lead. Lee (2006) looked into the differences between broadcasting and newspaper news translation in their approaches to rendering the so called “summary lead” part (Lee 2006: 318) of the news report in Korean–English translation. The analysis focuses on the shifts in English translations of Korean newspaper reports, and compares the findings with the results of a previous study on broadcasting translation (Lee 2002). Results show that while lead reduction is characteristic of broadcasting translation (producing more concise and focused leads in English), “Korean news reports tend to include in their leads information that is not part of the essential facts of the story” (Lee 2002: 318). This kind of information (names, titles, numbers, etc.) is generally removed from the lead in the process of translation. Lee (2006) explains that as opposed to broadcasting, lead expansion figures more prominently in newspaper translation: “[…] in newspaper translation, adding information to the lead appears to be more a matter of personal whim than compelled by a need to solve any specific translation problems” (e.g. adding information to contextualize the news event for foreign readers; solving a linguistic problem resulting from syntactic modification, such as shifting from passive to active) (Lee 2006: 325). The paper sheds light on how different the role of the translator is in the two types of translation:

[…] the newspaper translator was exercising greater latitude than the broadcast translator in deciding how the lead should be formed. This leads us to observe that there may be some differences in the role played by the translator in the two modes of translation. While both translators appeared to be fulfilling their traditional roles as ‘cultural mediator’ and ‘decision maker’ (Leppihalme, 1997: 19), the newspaper translator also acted much more visibly as a ‘gatekeeper’ (Vourinen 1995; Fujii 1988) by taking advantage of greater freedom to determine what is to be included or excluded in the lead.

Lee 2006: 326

The results of research on the summary lead section of news reports bare special relevance to the current undertaking, as the summary section of the analytical news article analyzed here fulfills a similarly crucial discourse function and thus its translation may be assumed to be affected and constrained by similar factors.

The fourth type of approach to researching news translation focuses on various suprasentential aspects of complete news texts. Of the distinct means of creating continuity and thus coherence, Sidiropoulou (1995b) explores logical relations and, within those, causal shifts in news reporting. The examination of text structure modifications of causal connections in translated news report items is motivated by the fact that it may help reveal “cross-cultural differences in the addresser-addressee relationships and in the ideological message conveyed” (Sidiropoulou 1995b: 84). Sidiropoulou considers these differences significant for the translator in the transfer of information from one language to another so that communicative equivalence may be achieved. Based on her analyses, she claims that “Greeks can easily process information, provided it is causally presented” (Sidiropoulou 1995b: 85). Consequently, the translator interferes with the clausal structure of the text in three ways:

Sidiropoulou 1995b: 87

to explicate the causal connection;

to invent a cause (or result) by manipulating the semantic content of source text fragments;

both propositions x and y are a result of the translator’s inference-drawing mechanism.

Another source of continuity within text is its thematic structure. Based on a systematic investigation of narrative and Theme–Rheme progression – understood as a textual rather than sentential phenomenon – in material posted at the Euronews internet portal, Valdeón (2009) examined the success of this news venture at “projecting a European perspective of world affairs” to counterbalance the Anglophone bias of CNN and BBCWorld. He analyzed 85 news items in three thematic areas: economy, politics, and culture. Three factors related to Theme–Rheme progression were studied:

the Theme (or the news event itself and developed in Rhemes);

sub-Themes (secondary events related to the main news event, used as a coherence strategy to provide the reader with background knowledge and arouse interest);

the visual presentation of the item within the internet page.

Perspective is an important aspect of Valdeón’s (2005) study too, where he explores the extent to which the translated Spanish service of the BBC depends on English sources. His analytical framework accounts for linguistic elements and explains social, ideological, and political implications in 134 articles from BBC Mundo and BBC News. The extensive textual analysis covers the complete texts, including their headlines, the stories proper (textual organization, stylistic problems/register, grammatical deficiencies, lexical choices) and offers a contrastive investigation of source and target texts in terms of omissions, additions, and permutations (editorial and translational procedures). Interestingly, and contrary to the findings of research referred to earlier (e.g. Bielsa 2007), he found that only a few articles had been specifically written for a Spanish-speaking readership, but even in these cases a strong dependence on English sources could be observed (Valdeón 2005: 215).

2.2. Thematic, information and topical structure in translation

2.2.1. An overview

Impressive body of research is available on the study of thematic and information structure in translation involving different language pairs as well as distinct focuses of analysis. The language pairs (involving English) that have gained much attention include Arabic–English (Al-Jarf 2007; Baker 1992; Elimam 2009), Brazilian Portuguese–English (Johns 1991), Chinese–English (Lee 1993; Zhu 1996; 2005), German–English (Doherty 1997; 1999; 2003; Fetzer 2008; Rogers 2006; Ventola 1995), Norwegian–English (Johansson 2004), Slovene–English (Limon 2004) and Spanish–English (Polo 1995; Williams 2005). There is also work that involves Hungarian, focusing on Russian–Hungarian (Klaudy 1984; 1987), Serbian–Hungarian (Pásztor Kicsi 2007) and English–Hungarian (Klaudy 2004) translation.

With regard to the main focuses of analysis, the research activity portrays similar diversity. Some studies deal with thematic and information structure in more general terms (e.g. information structure/Given–New: Baker 1992; Limon 2004; Rogers 2006; information distribution: Doherty 1997; 2003; Zhu 1996; thematic structure/Theme–Rheme: Baker 1992; Johns 1991; Klaudy 1984; 1987; 2004; Valdeón 2009; Williams 2005; Zhu 2005), while others concentrate on restricted aspects of clauses/sentences that have important bearing on Theme and/or information structure, such as word order (Al-Jarf 2007; Baker 1992; Elimam 2009), sentence beginnings (Doherty 2003; Rogers 2006), cleft sentences (Doherty 1999), or subject selection (Johansson 2004; Lee 1993).

Despite their volume, research findings in the field are conflicting and tend to remain inconclusive regarding the effects of changing or reproducing source-language thematic/information structure in translation. The kind of approach that has been shown to be instrumental in solving this problem is one that is not constrained merely to the clause or the sentence, but extends the analysis to the paragraph or text level (e.g. Fawcett 1997/2003; Gerzymisch-Arbogast, Kunold et al. 2006; Ghadessy 1995; Hatim and Mason 1990; Limon 2004; Polo 1995; Valdeón 2009; Zhu 1996; 2005).

2.2.2. A discourse-oriented approach to information and thematic structure in translation

The discourse-oriented approach to the study of information and thematic structure in translation connects sentence/clause-level analysis with discourse and rhetorical structure. In the study of information structure, Limon (2004: 60) developed an analytical framework which compares the underlying rhetorical structure of the text with its surface ordering in order to determine the degree of fit between them. The framework allows for the systematic study of coherence, cohesion, information structure, and register features. Based on the analysis of his data (annual report to the European Commission in Brussels on accession criteria in English and Slovene), he concludes that

the translator’s work had not been sufficiently informed by an awareness of the different ways in which information structure is handled in the two languages. The approach taken in the translation is unsystematic: sometimes the original word order is retained, on occasion though the use of the passive, with the result that the reader is presented with a marked but communicatively unmotivated new–given pattern; in other instances the original word order is dispreferred, even though its use would have made the processing of the text much easier.

Limon 2004: 62

In a similar vein, Ventola’s (1995) work focuses on thematic structure, more precisely on thematic progression in the English translation of philosophy texts produced by a German author. He starts out from the assumption that the reader may notice that the focus of argumentation differs in the original text and in the translation. Readers tend to find texts awkward, because they display “some odd thematic structure not typical of the language of the translation” (Ventola 1995: 91); the translation distorts the argumentative and rhetorical patterns. Ventola’s study illustrates this in practice by taking the Theme–Rheme structures as examples and discussing the problems that can be found in the translations both at the clause level as well as above it. His analyses reveal that

[t]he translator seems to make unmotivated changes in the Theme–Rheme structure of the clauses. Consequently the translator only partially succeeds in displaying the unfolding of the global structure of the article in English; the German version appears clearer in its presentation of the unfolding. […] But the solution for the translator is not to translate literally either, always keeping strictly to the original patterns, because, […], these literal translations may make the text very cumbersome as well. […] When this relatively ‘literal’ translation practice is then combined with some changes in the thematic and informational structures, the resulting translation totally destroys the rhetorical effects that the author has carefully tried to construct in German […].

Ventola 1995: 98

Both studies point to the fact that translators pursue unsystematic strategies and need guidance with regard to the translation strategy. Continuing the line of research on thematic structure represented by Ventola (1995), in what follows it will be argued that Lautamatti’s (1987) Topical Structure Analysis (TSA), originally developed for the study of topical development in English discourse, and shown to account reliably for the relationship between certain textual features and discourse quality (Schneider and Connor 1990; Witte 1983) is capable of providing further insights into the relationship between thematic structure, rhetorical structure and translation quality.

2.2.3. Rationale for the analysis of topical structure in translation

The notions of topic and topical structure as used in TSA bring together various overlapping and competing, but – from the point of view of the aims of this study – relevant aspects of information structure and thematic structure. Topic is associated in TSA with Given information (as opposed to the notion of focus, which contains New information). The analytical framework, built upon the work of the Prague School linguists, most importantly Daneš (1974), employs the term Theme to refer to what the sentence is about (in contrast with Rheme, referring to what is said about the Theme[6]).

By locating the so called topical subjects of the sentences/clauses, TSA is capable of tracing topical development[7] in written discourse and establishing a link between individual clause/sentence Themes (topics), discourse topic and, ultimately, discourse quality/coherence.[8] In TSA the term topic is not used in the sense of a “topicalized” or “fronted element” (as in e.g. Halliday and Matthiessen 2004: 79; or Fawcett 1997/2003: 87[9]), but as “the idea discussed” (Lautamatti 1987: 89; the emphasis is mine) as expressed in “a mood subject relating to the discourse topic” (i.e. topical subject).

The idea is not completely new to translation research. A similar functional approach, connecting systemic-functional linguistics and speech act theory, has been developed by Zhu (1996; 2005). Taking a textual perspective on the thematic structure of sentences, Zhu aligns the information/thematic structure of the sentence and its textual potential and discusses “the relationship between a sentence’s thematic structure and its functional status in the text, and the necessity and possibility to align sentential speech acts with the textual speech act through appropriate syntactic management” (Zhu 2005: 312). Based on analyses of information presentation in translation using this combined framework, Zhu (1996) concludes that

[a]ny translation should be a linguistic operation in a textual sense, which entails a structural examination of the meaning of the text realized by units on level lower than the (full) text, such as the word and sentence, as well as those higher, such as genre and culture at large.

Zhu 1996: 323

In the field of news research, analyzing written sports commentaries from The Times, Ghadessy (1995) also stresses the importance of the study of thematic development and its relationship to registers and genres. Building on Halliday’s (1985) work, he concludes that the choice of Themes in clauses plays an essential role in discourse organization: it is considered instrumental in the “method of development” (Ghadessy 1995: 132) of the text.

2.2.4. Lautamatti’s (1987) model of TSA

In sum, TSA is a text-based approach to the study of the development of topic in discourse, with a pragmatic orientation, which has been found useful in identifying text-based features of coherence and discourse quality (Schneider and Connor 1990; Witte 1983). TSA is built upon the assumption that in English “the subject of an individual sentence is generally the element representing ‘what the sentence is about’ (see Chafe 1976), ‘announcing the topic rather than offering new information about the chosen subject-matter’ (Turner 1973: 315)” (Lautamatti 1987: 88). Thus, sentences in discourse are claimed to contribute to the development of discourse topic by means of sequences that “first develop one sub-topic, adding new information about it in the predicate of each sentence, and then proceed to develop another” (Lautamatti 1987: 88). Lautamatti identifies three types of topical progression:

parallel progression: “the sub-topic in a number of successive sentences is the same” (Lautamatti 1987: 88), i.e. “the topical subjects of successive sentences have the same referent” (Lautamatti 1987: 95);

sequential progression: “the predicate, or the rhematic part of the sentence provides the topic [topical subject] for the next” (Lautamatti 1987: 88);

extended parallel progression: “the primary sub-topic is re-assumed without being reintroduced by sequential progression” (Lautamatti 1987: 99-100).

Table 1 (based on Lautamatti 1987: 92-96) illustrates the three types of progression (topical subjects appear in italics):

Table 1

Types of progression

TSA only deals with subjects which are in the position of the subject and are referred to as mood subjects. Also, it distinguishes between mood subjects that are so called structural dummies (e.g. there in an existential clause) and lexical (or notional) subjects. Only if a lexical subject relates directly to the discourse topic, does Lautamatti consider it as the topical subject.[10]

3. Research design

3.1. Research questions and hypotheses

This research seeks answers to two main questions related to the translation of the summary section of the analytical news article:

How do topics shift and relate to discourse topic in source and target texts? More precisely, the study explores whether the topical structures of the English translations deviate from the Hungarian originals in terms of the frequency of parallel, extended parallel and sequential topic progressions in them;

What kind of connections can be identified between the way the topical structure and the event structure of the texts unfold and relate to each other in translation? This analysis focuses on those components of the event structure in which the topical subjects of the ST and those of the translation differ. The aim of the investigation is to reveal any systematic links between shifts in topical structure and news content.

The first question is studied using a quantitative research methodology. Based on the results of previous research (Sections 2.2.1–2.2.2) and taking into account the (considerable) structural differences between Hungarian and English, it is hypothesized that the topical structures of translations will significantly differ from those of their originals. The second question requires an exploratory, qualitative approach that provides sufficient data to be able to generate hypotheses regarding the relationship between the topical and the generic structure of the texts in the corpus.

3.2. The corpus

The corpus is composed of the “summary” sections of translated English analytical news articles and their corresponding Hungarian originals retrieved from the website of Budapest Analyses, one of Hungary’s internet based news magazines visited mainly by foreigners (including news agencies) within and beyond the country’s borders. Budapest Analyses, as its name also suggests, publishes analytical articles on political, economic, financial, social and cultural events taking place in or related to Hungary. The corpus contains 20 Hungarian summaries and their English translations, altogether 40 texts (6658 words). The summaries have been randomly selected from the period between 2006-2009 (sample texts: Appendices A, B).

The summary, a typically one (rarely two) paragraph long section, precedes the analysis section of the article and fulfills an important discourse function: it indicates the main message of the article and mentions the most important topics and supporting arguments to be discussed and elaborated on in detail. Therefore this section plays the same role as the lead, or the so called “summary lead” of news stories, which is “the first sentence(s) in a straight news story that serves to summarize the news event. By principle, a lead is to be written to include only the most important facts of the story” (Lee 2006: 318)[11].

The analytical news article differs in important ways from the news stories generally discussed in the literature. It contains five parts:

country (statement of the name of the country/countries the analysis focuses on);

subject (i.e. title; e.g. The bumpy road of the healthcare reforms, The deployment of the American missile defence system, Hungarian-South African relations);

summary (sometimes also referred to as “introduction”);

analyses (a typically 6-10 paragraph long, critical analysis of the subject); and

conclusions (generally in one paragraph).

Its contents and rhetorical development is characterized by an analytical, critical, argumentative approach, therefore it belongs to the category of “argumentative news genres” (Gottlieb 2010: 199). In his discussion of news genres and their types of translation, Gottlieb (2010: 198-199) identifies two main groups. One group contains the “informative news genres,” whose translation is claimed to be typically characterized by washing away the foreign traces. Consequently, the translator remains invisible to local audiences, who believe that what they read is an article originating in their own language. In the case of the other group, the “argumentative news genres,” both the original author and the translator are credited. When translating such texts, translators are expected to stay loyal to the content and form of the original. Although the articles published in Budapest Analysis do not indicate the name of the author or the translator (they do not feature attribution), the description of the aims and scope of the magazine published at the website defines its authorship (consisting of policy analysts, economists and social scientists with high professional reputation). Therefore the translations of these articles are expected to be characterized by loyalty to the source text both in content and form.

3.3. Procedures of analyzing corpus data

TSA was carried out manually, based on Lautamatti’s (1987) work. To ensure the reliability of the analysis, double coding was conducted: besides the author of this study, another trained analyst also coded the corpus independently. The results obtained from the two coders were compared and inter-coder reliabilities were computed using Pearson product-moment correlations: parallel progression (reliability coefficient: 0.98), extended parallel progression (0.99), sequential progression (0.96), topical depth (0.96). The coefficients are above the 0.90 level for all variables, indicating a high degree of correspondence between the two coders, therefore the reliability of the coding procedure is reinforced. In order to test the significance of the difference between source texts and translations, paired-samples t-tests were conducted on all variables using SPSS 11. To explore how deviations in topical structure may affect event structure and news content, a qualitative investigation complemented the quantitative (statistical) analysis of the corpus. The qualitative analysis was conducted manually, following Bell’s (1991) methodology.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Quantitative analysis of topical structure

The TSA of the corpus shows that the summary sections of the analytical news articles are characterized by the dominance of sequential progressions (with a mean value of 4.14 in the Hungarian STs and 4.50 in the English TTs, as opposed to 1.20 and 1.00 for parallel progressions and 0.87 and 0.70 for extended parallel progressions). This may be explained by the nature and the discourse function of this text type. As mentioned in the description of the corpus (Section 3.2), it aims to summarize the main message of the article and enumerate the topics/arguments related to the discourse topic, which are then discussed and elaborated on in the analysis section. These topics/arguments materialize in newly introduced, related sentence topics (topical subjects) in the summary sections, producing a high number of sequential progressions, rather than parallel or extended parallel progressions. The latter would indicate repetitions of (i.e. staying on), or returning to previously mentioned topics – a feature that might be expected in the analysis sections of these articles, where the topics mentioned in the summary are developed one by one.

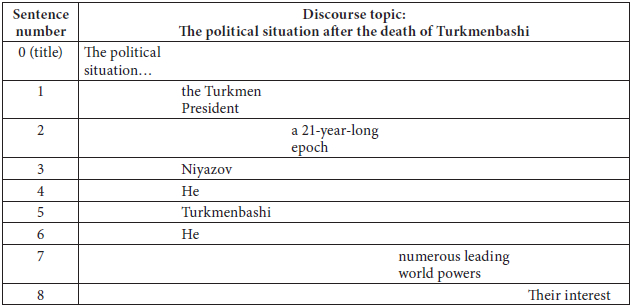

Table 2 illustrates this phenomenon (for the sake of convenience with the English translation of Text 15; for the full text see Appendix A), where sequential topic progressions (4 instances, between Sentences 0–1, 1–2, 2–3, 4–5) outnumber other progression types (parallel progression: one case, between Sentences 3–4; extended parallel progression: 0). Parallel and extended parallel progression are indicated in the figure by placing the topics that have the same referent below each other (in the same column); sequential progression is signaled by putting the new topic in the next column to the right.

Table 2

Topical progression in the English translation of Text 15

The vast majority of the texts in the corpus (18 out of the 20 STs as well as their translations) are characterized by such a “flat” structure, only two (Texts 12, 20) portray a different, more “vertical” structure as a result of the larger number of parallel progressions. The latter kind of structure is illustrated in Table 3 (Text 12E; full text: Appendix B): parallel progression appears between Sentences 3–4, 4–5, 5–6, and extended parallel progression between Sentences 1–3.

Table 3

Topical progression in the English translation of Text 12

The results of the TSA was submitted to statistical analysis too, to compare the two sub-corpora (originals and translations) in terms of the various types of topical progression (parallel, sequential, extended parallel progression) and the resulting topical depth (i.e. the number of newly introduced sub-topics) that characterize them (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4

Descriptive statistics for topical progression measures

Table 5

Paired samples t-test for all topical progression measures (two-tailed significance: *p<.05)

As argued above, the TSA demonstrated the dominance of sequential progressions over other progression types in both source texts and translations. The statistical comparison of the two sub-corpora, interestingly, also brought out this variable as the one that portrays a significant difference between sources and translations (Table 5; significance is marked by an asterisk). Table 4 shows that the mean frequency of sequential progressions is 4.15 in source texts and 4.50 in the translations. The example charted in Table 3 demonstrates this kind of shift (growth) in the number of sequential progressions. The English translation of Text 15 contains four sequential progressions (in addition to one parallel progression and no extended parallel progressions), whereas the Hungarian original (Table 6) has only three sequential progressions: between Sentences 0 and 1, Sentences 2 and 3 and Sentences 4 and 5 (along with two extended parallel progressions, between Sentences 0 and 2 and Sentences 2 and 4, and no parallel progressions). Thus the topical structure of the translation deviates considerably from that of the source (note the difference between the structures in Tables 2 and 6).

Table 6

Topical progression in the Hungarian original of Text 15

Due to the larger number of newly introduced topics, the topical depth of the translations also becomes significantly higher than that of the sources (with a mean value of 5.50 for topical depth in the former, and 5.15 in the latter; Tables 4 and 5). On the other hand, the t-tests do not indicate a significant difference between the two sub-corpora with regard to the mean frequency of parallel (1.20 vs. 1.00) and extended parallel topic progressions (0.85 vs. 0.70).

Taking all three types of progression into account, out of the 20 parallel texts, 14 translations preserved the topical progression of the original, and a considerable number of translations (six altogether: Texts 08, 12, 13, 14, 15, 20) deviated in some way from the source’s topical structure. In addition, if one examines the topical subjects of the two sub-corpora, an even more striking difference can be seen: of the 20 parallel texts, 11 contain sentences whose topical subjects are not the same. Table 7 lists where topical subjects or topical progression are not identical in the two sub-corpora (in the case of different subjects, the sentences whose subjects differ appear in brackets).

Table 7

Source and target texts with different topical subjects and/or different topical progression

Abbreviations: HST–ETT: Hungarian source text and its translation (English target text) S: sentence; 0: title

It is important to note that changing the topical subject in the translation does not always lead to modification in the type of progression and thus in the topical structure. For example, in Text 16, the topical subject of Sentence 2 differs in the Hungarian and the English version (HST: igen éles válaszok [very sharp reactions] vs. ETT: Moscow). Although different from each other, both topical subjects constitute a new topic compared to the topical subject of the preceding sentence (HST: …híre / ETT: The news) and thus both realize sequential progression.

In sum, the data provide further justification to the claim that translation is generally accompanied by shifts in the topical structure of the source text (Fawcett 1997/2003; Rogers 2006; Ventola 1995). However, this data set indicates that not all topical structure variables demonstrate significant differences (shifts). As topical structure and the quality of topical progression have been shown to play an important role in presenting (foregrounding or backgrounding) information in discourse (Lautamatti 1987; Schneider and Connor 1990; Ventola 1995), any change in the topical structure of translations (or in the information appearing as topical subject) compared to that of their originals may be indicative of potential problems in translation (e.g. change of emphasis/focus and, consequently, modified discourse content). Still, as argued in Section 2.2.1, little is known about the exact outcomes of such deviations. To gain further insights into the kind of changes that are triggered by different topical subjects and topical progressions, the corpus was also submitted to a content-focused, genre-based analysis.

4.2. Qualitative analysis of topical structure vs. event structure

In what follows, an in-depth analysis is offered of event structure components in which the topical subjects of the ST and those of the translation differ to reveal potential modifications in news contents. The summaries were reanalyzed to see what event structure components can be found in the corpus. Based on Bell’s (1991) work and taking into account the special nature of this genre, the following event structure components were identified as relevant in the analysis: abstract, actor, action, setting (time, place), follow-up (consequences, reaction), commentary (context, evaluation, expectations), and background (previous episodes, history).

As in most of the cases the topical subject represents the actor(s), i.e. the key “player(s)” of the story, the quality of the topical subject was examined in each sentence to see if it changes in the translation from actor status expressing, for instance, persons or institutions (e.g. a splinter group, the Romanian government, the President of the Republic, Vladimir Putin, etc.) to non-actor status, expressing other type of information (e.g. abstract notions or objects, such as the controversy,a shift,the inter-state alliance, etc.), or vice versa. The outcomes of the analysis are surprising: out of the 20 parallel texts, in the case of eight (Texts 01, 04, 06, 07, 12, 13, 14, 16), modification of status can be observed. Such modifications are worthy of attention as they shift the focus of the sentence and thus influence (sometimes even alter) its meaning. The following examples illustrate some of these changes in both directions: actor ⇒ non-actor, non-actor ⇒ actor:

If we take a closer look at the first example and analyze the complete sentence in which the given topical subjects appear, we can see (in the literal translation) that the translator could have produced a completely grammatical English version without changing either the topical subject, or the status of the topical subject. Still, the translator altered both, thus modifying considerably the focus/emphasis of the sentence:

The second step of the qualitative analysis focused on sentences whose topical subjects differ in the two sub-corpora to reveal which component of the event structure of the given news story these sentences represent. This investigation is necessary to better understand how shifts in topical structure affect news content, that is, to see exactly which elements of the event structure may be affected/marred. This analysis therefore concentrates only on text pairs (HST–ETT) in which there are differing topical subjects (i.e. texts marked with a + sign in the last column of Table 7). The results of the comparative analysis are shown in Table 8.

Table 8

Results of the Event Structure Analysis of sentences with differring topical subjects

Abbreviations: Cont: context, Eval: evaluation, Exp: expectation, Prev: previous episodes, His: history; S: sentence

Sentences with different topical subjects in the Hungarian original and the English translation realize the following event structure components: abstract (title), action, commentary (context, evaluation, expectation), background (previous episodes, history). Examples 5 to 8 illustrate each of these:

For instance, in example (8), that describes the background, we can see that in the English translation this increase (i.e., a different topical subject) appears in topic position instead of reforms (which is the topical subject in the Hungarian source text, because active-passive has a reverse structure in Hungarian compared with English). An alternative translation (8b) would have kept the same topical subject (az ellátás reformja/Healthcare reforms) in the target text, and a similarly grammatically well formed sentence would have been created:

Interestingly, however, the translator did not opt for this solution.

As Table 8 shows, it is in the background component of the event structure that topical subjects most frequently deviate in the two sub-corpora (containing altogether 7 such sentences: 4 relating previous episodes and 3 relating history). This is a striking outcome, as this component of the event structure is responsible for providing background information necessary to be able to interpret the contents and the message of the text. The function of this element becomes even more crucial in translation, where the target audience (from a different linguistic, cultural, social, historical, etc. background) may not possess the required source culture and language related background knowledge to be able to make sense of the text. Any changes in this component may therefore make processing more difficult and endanger the adequate interpretation of the translation.

Based on the outcomes of the qualitative investigations, it may be assumed that there are systematic connections between the way the generic (event) structure and the topical structure of the summaries unfold and relate to each other and that changes of topical structure (shifts of topical progression and/or topical subjects) may trigger changes of news content.

5. Conclusions

The main aim of this paper was to explore whether the current data provides further empirical evidence for the claim that news translation is influenced by norms similar to those regulating journalism and thus involves considerable modifications in the contents of news stories as reflected in their topical structures. Although the corpus does demonstrate some topical shifts of translation, overall a strong dependence may be observed in it on the Hungarian source text structure. This happens despite the fact that the magazine is published for a foreign (non-Hungarian L1) readership living in or outside of Hungary; a condition that typically entails localization in translation and thus significant transformations compared to the original (Gottlieb 2010: 199). This controversy may be explained by the nature of this genre and translation type. Being an argumentative news genre, it is characterized by strong loyalty to the original both in content and form. These results are not completely unprecedented in translation research, as Valdeón (2005: 215) – in his analysis of the Spanish service of the BBC – also found a few articles that have been written for a Spanish-speaking readership, but were characterized by a strong dependence on their English sources.

The other controversy of research directly motivating this investigation was related to the question of whether to retain or transform topical structure in translation. Due to the size of the corpus, only tentative suggestions are possible here, which need to be contrasted with more data. Still, based on the analyses, it may be assumed that this question cannot be answered safely for any language pair, without considering the characteristics of the particular genre. Therefore the findings confirm the line of research (represented among others by Bhatia 1997; Fawcett 1997/2003; Gallangher 1993) which asserts that besides the linguistic structure of the given languages, the stereotypical generic features of the text type/genre also need to be taken into account and contrasted with linguistic structure so that the generic motivation behind topical patterning can be identified and reliable recommendations may be formulated regarding the treatment of topical structure in translation. A contextual approach to the study of news discourse that combines genre- and text-oriented translation research may yield valuable data and findings that can later on be fed into translator training. Only by sensitizing translators to the special characteristics of genres will they be able to bring conscious decisions about the translation method to be pursued.

Parties annexes

Appendices

Appendix A. Text 15E

(0) The bumpy road of the healthcare reforms

(1) During the first four years of the MSZP-SZDSZ coalition that came to power in 2002, the Hungarian healthcare budgetary expenditure grew from 4.3% to 5.1% in proportion to the GDP, which amounts to a sizeable 74% increase. (2) However, this increase has not been accompanied by reforms. (3) By the summer of 2006 – due to the political blunders of the coalition – the introduction of wide scale austerity measures to every sphere of the fiscal budget became imminent. (4) Hence, the process of reforming the health service is simultaneously taking place with the drastic tightening of resources in several spheres, which contravenes the 2006 election promises on the one hand, and is being communicated in an obscure manner by the government, on the other. (5) All these issues have shaken the foundations of public confidence needed for the implementation of reforms, as well as encumber the sick and medical practitioners alike.

Anonymous 05 March 2007; see note 19

Appendix B. Text 12E

(0) The political situation after the death of Turkmenbashi

(1) As a result of a cardiac arrest, the Turkmen President Saparmurat Atayevich Niyazov, “The Father of All Turkmen” (Turkmenbashi), died on December 21st. (2) With the death of the leader, otherwise known as the “Great Leader” (Abar Sedar), a 21-year-long epoch has come to an end. (3) Niyazov came to power in 1985 in Turkmenistan, which was a Soviet republic at the time. (4) At the beginning he ruled the country from the position of first secretary of the Communist Party and later as elected president and from 2005 as president-for-life of the independent Turkmenistan. (5) During his rule, Turkmenbashi established a personality cult perplexing and unimaginable to Western democracies. (6) As the leader of his country, he simultaneously occupied the presidential and prime ministerial positions. (7) At his funeral on December 24, numerous leading world powers were represented, ranging from the Russian prime minister to the Assistant US Secretary of State, demonstrating their interests in the future development of the leaderless country. (8) Their interest is understandable: in view of its known resources, Turkmenistan is the 3rd-4th largest in the world in terms of natural gas reserves and thus its political system to a large degree affects the neighbouring countries, as well as the energy security of the whole world.

Anonymous 09 January 2007; see note 21

Notes

-

[1]

The research was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA, project number: K83243) and the Bolyai Research Grant. Parts of this article have been previously published in Hungarian: Károly, Krisztina (2011): Sajtószöveg és fordítás. A topikszerkezet és a hírtartalom viszonya újságcikkek fordításában. Magyar Nyelvőr. 135(4):459-480.

-

[2]

The notions of information, thematic and topical structure are used here to cover different notions as suggested by Fawcett (1997/2003), Halliday and Matthiessen (2004), and Lautamatti (1987); a more detailed description follows in Section 2.2.3.

-

[3]

For an overview of the different uses of this concept in Critical Discourse Analysis and Translation Studies, see Valdeón (2005: 197-199).

-

[4]

Due to the focus of the paper (news discourse and translation), the review does not offer a critical analysis of the Hallidayan (systemic functional) or the Prague School approaches to Theme, which have extensively been dealt with elsewhere (Bell 1991: 149-150; Fries 1995; from a translational point of view: Baker 1992; Fawcett 1997/2003).

-

[5]

In Translation Studies, Holland’s (2006: 247-249) work on Indonesian–English translation represents text as an “event.”

-

[6]

A systematic comparison of the notions of thematic and information structure, Theme–Rheme and Given–New is available in Fries (1995) and Baker (1992: 121), and of thematization and information in Bell (1991: 149-150).

-

[7]

The term topical development refers to the “way the written sentences in discourse relate to the discourse topic and its sub-topics” (Lautamatti 1987. 87).

-

[8]

Coherence refers to the “quality that makes a text conform to a consistent world picture and is therefore summarizable and interpretable” (Enkvist 1990: 14).

-

[9]

Theme: “what we are talking about,” “whatever comes in first position”; Rheme: “what we say about the Theme (Fawcett 1997/2003: 85); Theme–Rheme are not identical with Topic–Comment, as Topic refers to one kind of Theme, “topical Theme,” alongside the other two types of Theme, textual and interpersonal (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004: 64-79).

-

[10]

Subjects not directly related to the discourse topic are referred as “non-topical subjects” in TSA. This does not mean that non-topical linguistic material is not important in discourse. It only implies that it has distinct functions: organizing the subject-matter, making explicit the illocutionary force of the statement, indicating truth value, making explicit the author’s attitude to subject matter, providing author’s commentary (Lautamatti 1987: 91).

-

[11]

The summaries constituting the current corpus, however, are considerably longer (approximately 100-300 words) and more informative than summary leads, as “[t]he length of typical summary leads is no more than 35 words, and it recounts the most important of the six basic elements of an event, the 5W’s and H” (Itule and Anderson 1994: 58-60, cited in Lee 2006: 318).

-

[12]

Text 04H: anonymous (29 March 2004): A határon túli magyarok és a magyarországi Szabad Demokraták Szövetségének (SZDSZ) viszonya. Budapest Analyses No. 62.

-

[13]

Text 04E: anonymous (29 March 2004): The relationship between Hungarians beyond the borders and the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ). Budapest Analyses No. 62.

-

[14]

Text 06H: anonymous (30 September 2005): Oroszország mozgásterének beszűkülése a „közel-külföldön” és az európai érdek. Budapest Analyses No. 72.

-

[15]

Text 06E: anonymous (30 September 2005): The constrictions of Russia’s space for manoeuvre in the “near abroad” and the interests of Europe. Budapest Analyses No. 72.

-

[16]

Text 14H: anonymous (19 February 2007): A romániai magyarság lehetséges képviselete az Európai Parlamentben. Budapest Analyses No. 141.

-

[17]

Text 14E: anonymous (19 February 2007): The prospects of representing the Romanian Hungarian minority in the European Parliament. Budapest Analyses No. 141.

-

[18]

Text 12H: anonymous (09 January 2007): A Türkmenbasi halála utáni politikai helyzet. Budapest Analyses No. 131.

-

[19]

Text 12E: anonymous (09 January 2007): The political situation after the death of Turkmenbashi. Budapest Analyses No. 131.

-

[20]

Text 20H: anonymous (16 May 2008): A magyar katonai szerepvállalás. Budapest Analyses No. 194.

-

[21]

Text 20E: anonymous (16 May 2008): The Hungarian military role. Budapest Analyses No. 194.

-

[22]

Text 13H: anonymous (15 January 2007): A Déli Áramlat gázvezeték terve. Budapest Analyses No. 180.

-

[23]

Text 13E: anonymous (15 January 2007): The planned South Stream gas pipeline and Hungary. Budapest Analyses No. 180.

-

[24]

Text 15H: anonymous (05 March 2007): Az egészségügy reformjának rögös útja. Budapest Analyses No. 144.

-

[25]

Text 15E: anonymous (05 March 2007): The bumpy road of the healthcare reforms. Budapest Analyses No. 144.

Bibliography

- Al-jarf, Reima Sado (2007): SVO word order errors in English-Arabic translation. Meta. 52(2):299-308.

- Baker, Mona (1992): In Other Words. London: Routledge.

- Bell, Allan (1991): The Language of News Media. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bell, Allan (1998): The discourse structure of news stories. In: Allan Bell and Peter Garrett, eds. Approaches to Media Discourse. Oxford: Blackwell, 64-104.

- Bhatia, Vijay K. (1997): Translating legal genres. In: Anna Trosborg, ed. Text Typology and Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 203-214.

- Bielsa, Esperança (2007): Translation in global news agencies. Target. 19(1):135-155.

- Bielsa, Esperança (2010): Cosmopolitanism, translation and the experience of the foreign. Across Languages and Cultures. 11(2):161-174.

- Bielsa, Esperança and Bassnett, Susan (2009): Translation in Global News. London: Routledge.

- Chesterman, Andrew (1995): Ethics of translation. In: Mary Snell-Hornby, Zuzana Jettmarová and Klaus Kaindl, eds. Translation as Intercultural Communication. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 123-133.

- Daneš, Frantisek (1974): Functional sentence perspective and the organization of the text. In: Frantisek Daneš, ed. Papers on Functional Sentence Perspective. The Hague: Mouton, 106-128.

- Doherty, Monika (1997): Acceptability’ and language-specific preference in the distribution of information. Target. 9(1):1-24.

- Doherty, Monika (1999): Clefts in translation between English and German. Target. 11(2):289-315.

- Doherty, Monika (2003): Parametrized beginnings of sentences in English and German. Across Languages and Cultures. 4(1):19-51.

- Elimam, Ahmed Saleh (2009): Marked word order in the Qur’ān: functions and translation. Across Languages and Cultures. 10(1):109-129.

- Enkvist, Nils Erik (1990): Seven problems in the study of coherence and interpretability. In: Ulla Connor and Ann M. Johns, eds. Coherence in Writing: Research and Pedagogical Perspectives. Washington: TESOL, 9-28.

- Fairclough, Norman (1995): Media Discourse. London: Arnold.

- Fawcett, Peter (1997/2003): Translation and Language. Linguistic Theories Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Fetzer, Anita (2008): Theme zones in contrast: An analysis of their linguistic realization in the communicative act of a non-acceptance. In: Maria Gómez-Gonzalez, Lachlan Mackenzie and Elsa Gonzáles Alvarez, eds. Languages and Cultures in Contrast: New Directions in Contrastive Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 181-231.

- Fries, Peter H. (1995): A personal view of Theme. In: Mohsen Ghadessy, ed. Thematic Development in English Texts. London: Pinter, 1-19.

- Gallangher, John D. (1993): The quest for equivalence. Lebenden Sprachen. 38(4):150-161.

- Gerzymisch-Arbogast, Heidrun, Kunold, Jan and Rothfuβ-Bastian, Dorothee (2006): Coherence, theme, rheme, isothopy: Complementary concepts in text and translation. In: Carmen Heine, Klaus Schubert and Heidrun Gerzymisch-Arbogast, eds. Text Translation: Theory and Methodology of Translation. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, 349-370.

- Ghadessy, Mohsen (1995): Thematic development and its relationship to registers and genres. In: Mohsen Ghadessy, ed. Thematic Development in English Texts. London: Pinter, 129-146.

- Gottlieb, Henrik (2010): Multilingual translation vs. English-fits-all in South African media. Across languages and cultures. 11(2):189-216.

- Halliday, Michael A. K. (1985): Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, Michael A. K. and Matthiessen, Christian M.I.M. (2004): An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Arnold.

- Harsányi, Ildikó (2008): Metaforarendszerek fordítása – sajtószövegek elemzése kognitív megközelítésből. Fordítástudomány. 10(1):42-60.

- Harsányi, Ildikó (2010): A metafora mint az alternative konceptualizáció eszköze a fordításban. Fordítástudomány. 12(2):5-23.

- Hatim, Basil and Mason, Ian (1990): Discourse and the Translator. Harlow: Longman.

- Holland, Robert (2006): Language(s) in the global news: Translation, audience design and discourse (mis)interpretation. Target. 18(2):229-259.

- Johansson, Stig (2004): Why change the subject? On changes in subject selection in translation from English into Norwegian. Target. 16(1):29-52.

- Johns, Tim (1991): It is presented initially: linear dislocation and interlanguage strategies in Brazilian academic abstracts in English and Portuguese. Mimeograph. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

- Károly, Krisztina (2010): Shifts in repetition vs. shifts in text meaning: A study of the textual role of lexical repetition in non-literary translation. Target. 22(1):40-70.

- Klaudy, Kinga (1984): Hogyan alkalmazható az aktuális tagolás elmélete a fordítás oktatásában? Magyar Nyelvőr. 3:325-332.

- Klaudy, Kinga (1987): Fordítás és aktuális tagolás. Nyelvtudományi Értekezések. 123. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Klaudy, Kinga (2004): A kommunikatív szakaszhatárok eltűnése a magyarra fordított európai uniós szövegekben. Magyar Nyelvőr. 128(4):389-407.

- Lautamatti, Liisa (1987): Observations on the development of the topic in simplified discourse. In: Ulla Connor and Robert B. Kaplan, eds. Writing across Languages: Analysis of L2 text. Reading: Addison-Wesley, 87-114.

- Lee, Chang-soo (2002): Strategies for translating Korean broadcast news reports into English. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Translation and Interpretation Studies, Seoul, Korea, Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation, HUFS, 93-111.

- Lee, Chang-soo (2006): Differences in news translation between broadcasting and newspapers: A case study of Korean-English translation. Meta. 51(2):317-327.

- Lee, Cher-leng (1993): Translating zero anaphoric subjects into English. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 1993(1):47-56.

- Limon, David (2004): Translating new genres between Slovene and English: An analytical framework. Across Languages and Cultures. 5(1):43-65.

- Nord, Christiane (1995): Text-functions in translation: Titles and headings as a case in point. Target. 7(2):261-284.

- Nord, Christiane (1997): Translating as a Purposeful Activity – Functionalist Approaches Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Paksy, Eszter (2005): Szerző és olvasó viszonya a fordított szövegben. Fordítástudomány. 7(1):60-69.

- Paksy, Eszter (2008): Metaszöveg és ethosz a fordításban. Fordítástudomány. 10(2):47-60.

- Pásztor Kicsi, Mária (2007): Vajdasági magyar médiaszövegek mondatszerkesztésének összehasonlító kvantitatív elemzése. Hungarológiai Közlemények. 2:71-85.

- Polo, Javier Fernandez (1995): Some discoursal aspects in the translation of popular science texts from English into Spanish. In: Brita Wårwik, Sanna-Kaisa Tanskanen and Rirto Hiltunen, eds. Organization in discourse. Proceedings from the Turku conference. Anglicana turkuensia. 14:257-264.

- Reiss, Katharina (2000): Translation Criticism – The Potentials and Limitations. Categories and Criteria for Translation Quality Assessment. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Reiss, Katharina and Vermeer, Hans J. (1984): Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Renkema, Jan (2004): Introduction to Discourse Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Rogers, Margaret (2006): Structuring information in English: A specialist translation perspective on sentence beginnings. The Translator. 12(1):29-64.

- Schneider, Melanie and Connor, Ulla (1990): Analyzing topical structure in ESL essay: Not all topics are equal. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 12:411-427.

- Sidiropoulou, Maria (1995a): Headlining in translation: English vs. Greek press. Target. 7(2):285-304.

- Sidiropoulou, Maria (1995b): Causal shifts in news reporting: English vs. Greek press. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 3(1):83-92.

- Sidiropoulou, Maria (1998): Quantities in translation: English vs. Greek press. Target. 10(2):319-333.

- Taylor, Christopher (1993): Systemic linguistics and translation. Occasional Papers in Systemic Linguistics. 7:87-103.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2005): The “translated” Spanish service of the BBC. Across Languages and Cultures. 6(2):195-220.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2009): Euronews in translation: Constructing a European perspective of/for the world. Forum. 7(1):123-153.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2010): Translation in the informational society. Across Languages and Cultures. 11(2):149-160.

- van Doorslaer, Luc (2010): The double extension of translation in the journalistic field. Across Language and Cultures. 11(2):175-188.

- Ventola, Eija (1995): Thematic development and translation. In: Mohsen Ghadessy, ed. Thematic Development in English Texts. London: Pinter, 85-104.

- Williams, Ian A. (2005): Thematic items referring to research and researchers in the discussion section of Spanish biomedical articles and English-Spanish translations. Babel. 51(2):124-160.

- Witte, Stephen (1983): Topical structure and writing quality: Some possible text-based explanations of readers’ judgements of students’ writing. Visible Language. 17:177-205.

- Zhu, Chunshen (1996): Translation of modifications: About information, intention and effect. Target. 8(2):301-324.

- Zhu, Chunshen (2005): Accountability in translation within and beyond the sentence as the key functional UT: Three case studies. Meta. 50(1):312-335.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Types of progression

Table 2

Topical progression in the English translation of Text 15

Table 3

Topical progression in the English translation of Text 12

Table 4

Descriptive statistics for topical progression measures

Table 5

Paired samples t-test for all topical progression measures (two-tailed significance: *p<.05)

Table 6

Topical progression in the Hungarian original of Text 15

Table 7

Source and target texts with different topical subjects and/or different topical progression

Table 8

Results of the Event Structure Analysis of sentences with differring topical subjects

10.7202/016072ar

10.7202/016072ar